1. Introduction

The prevalence of prostate cancer (PCa) in men is increasing worldwide owing to the aging population and the widespread screening for prostate-specific antigen (PSA); these factors have resulted in PCa having the highest recorded morbidity rate among all male-related malignancies. (1) In 2015, PCa was the leading type of male-related cancer, followed by stomach and lung cancers. (2) This trend has also been observed in Japan.

Surgical intervention, external beam radiotherapy, proton therapy, heavy iron radiotherapy, low dose rate (LDR) brachytherapy, high dose rate brachytherapy, and active surveillance are generally used to treat localized PCa (

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer, https://

www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/clinically-localized-prostate-cancer-aua/astro-guideline-2022). (3) Among these treatment options, LDR brachytherapy is preferred for patients with PCa who are old or have poor tolerance to treatment. Barringer invented and reported this method for the first time in 1917. (Barringer BS. Radiation for the treatment of bladder and prostate carcinomas JAMA 1917; 68:1227-1230) Since then, the procedure for LDR brachytherapy has been improved, and sophisticated methodologies have been introduced over the years, leading to the procedure being widely used worldwide, exhibiting good clinical outcomes. (4) (5) Barringer predicted that surgery for PCa could become extinct in the future. This claim has not been in the spotlight for many decades; however, with the advent of tri-modality therapy comprising hormone therapy, brachytherapy, and external beam radiotherapy for high-risk PCa and its favorable clinical outcomes, it may be a viable goal.

In the first part of the present study, we showed the clinical outcomes of LDR brachytherapy in multiple institutes in Japan. In the second part, we described the clinical outcomes of patients with localized low-to-intermediate PCa. In the third part, we discussed clinical trials investigating multi-modal brachytherapy for localized intermediate-to-high-risk PCa in Japan. Next, we summarized implantation methods and seed type of brachytherapy in detail. Finally, we described the open new challenging procedures of LDR brachytherapy, including tri-modality therapy, salvage brachytherapy, focal therapy, and future automatic brachytherapy equipment development.

Regarding the invariable indications for LDR brachytherapy, most urologists consider that patients with low or intermediate PCa should undergo LDR brachytherapy alone or LDR brachytherapy combined with external beam radiation therapy, which can be observed in recent clinical case conferences of nearly every urology department. Even with the recent technological advancements, not many high-risk PCa cases are treated with tri-modality therapy. Furthermore, radiation oncologists and urologists who are not performing LDR brachytherapy tend to dwell on the misalignment of LDR seeds unnecessarily. This leads to suspicion among the other radiation oncologists and urologists regarding the precision of the brachytherapy performed. In addition, the reputation of brachytherapy as a monotonous procedure performed by a single urologist in every institute may hinder the widespread applicability of the procedure. We hope that the present study will aid in resolving these concerns as it summarizes not only the invariable factors that lead to good clinical outcomes but also the importance of openness to new challenging procedures of LDR brachytherapy for PCa.

2. Clinical outcomes of localized low-to-intermediate Pca treatment

Brachytherapy is considered an effective treatment option for patients with localized PCa. (

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/clinically-localized-prostate-cancer-aua/astro-guideline-2022) American Brachytherapy Society has stated that brachytherapy is a convenient, effective, and well-acceptable treatment for localized PCa. (6) However, despite its advantages, brachytherapy cannot be performed in all clinical institutes, leading to the impression of this treatment as a “minor” option. One large review from Japan showed a median follow-up duration of 75 months and 7-year biochemical recurrence-free survival rates of 98%, 93%, and 81% in patients with low-, intermediate-, and high-risk PCa, respectively. (5) (7) The indications for combination therapy in the study were as follows: low-, intermediate-, and high-risk PCa should be treated with brachytherapy alone, brachytherapy combined with irradiation therapy, and brachytherapy combined with neoadjuvant androgen deprivation and external radiation therapy, respectively. (5) (7) Clinical outcomes of localized low-to-intermediate Pca treatment in our institutes were consistent with the general outcomes of brachytherapy for low-to-intermediate PCa (data not shown), as reported in these reviews. (5) (7) Therefore, the high biochemical recurrence-free survival rate indicated that low-to-intermediate-risk PCa could be controlled using LDR alone or LDR combined with external radiation therapy under appropriate treatment selection. In addition, most Japanese institutes employ radiation oncologists to decide the seed implant position before initiating needle puncture. The seeds were repositioned during the puncture and implantation procedures. This dynamic dose calculation method might produce sufficient dose distribution and good clinical outcomes (8) compared with other procedures in which urologists puncture the prostate before planning seed placement, which is mainly led by radiation oncologists. (9) As mentioned above, despite some unpopularity and limited institutional procedure, strong evidence of the unchangeability and stability of brachytherapy for low-to-intermediate-risk PCa was demonstrated.

3. Clinical trial of multi-modality brachytherapy for localized intermediate-to-high-risk PCa in Japan

In this section, we introduce two clinical trials conducted in Japan to evaluate the efficacy of brachytherapy in patients with intermediate- or high-risk PCa, both with or without prolonged hormonal therapy. The high-risk group was supplemented with external-beam irradiation as a part of tri-modality therapy. The studies also assessed how the combination of these therapies should be implemented in each risk group, a topic that remains unclear. One study, “Seed and hormone for intermediate-risk prostate cancer (SHIP) 0804,” was designed to examine this issue. SHIP 0804 is a phase III, multicenter, randomized, controlled study conducted in Japan and will compare brachytherapy with short- versus longer-term hormonal treatment in patients with intermediate-risk PCa. Both groups were treated with neoadjuvant hormonal therapy first for 3 months. Patients in one group received no further therapy, whereas their counterparts underwent 9-month adjuvant hormonal therapy. The results of SHIP 0804 could identify the rationale of hormonal therapy in patients with contemporary intermediate-risk PCa undergoing brachytherapy. (10) The planned 10-year follow-up in SHIP0804 after brachytherapy has just been fulfilled, and data are being analyzed accordingly. Another trial entitled “Tri-Modality therapy with I-125 brachytherapy, external beam radiation therapy, and short-or long-term hormone therapy for high-risk localized prostate cancer (TRIP)” has also matured. This phase III, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial also evaluated the efficacy of brachytherapy combined with external-beam irradiation with shorter- versus longer-term hormonal therapy in patients with high-risk PCa. The manuscript has been submitted to a journal and is now under peer review. (11)

4. Summary of implantation methods and seed type in brachytherapy

Brachytherapy requires at least 25 cases to achieve a standard level of implantation proficiency, including those regarding needling and dosimetry skills. (12) There are many tips detailing the position of lithotripsy, ingenuity of puncturing through pubis obstacles, adjustment of needle direction using a diddler, fewer number of punctures to reach the point that the radiation oncologists require, and accurate placement of seeds. In our institutes, approximately 30 cases are considered to achieve appropriate experience regarding the standard variations in brachytherapy processes. Notably, communication with radiation oncologists highly skilled in brachytherapy during the procedures can be the key to accomplishing satisfactory completion. As mentioned previously, the number of urologists performing brachytherapy tends to be lower, even in major institutes. Future studies should focus on ways to address this limitation regarding the number of trained urologists. This will lead to the advantage of reducing the average workload for brachytherapy and passing down specific skills related to the procedure.

There are questions regarding the seed type of brachytherapy, including which seeds lead to better brachytherapy: single- or linked strand-type seeds? Linked strand-type seeds have been reported to require 42 min per case of brachytherapy. (13) It also enables more stable and accurate implantation. Furthermore, linked strand-type seeds can be placed outside the prostate capsule, resulting in sufficient radiation dose distribution outside the prostate gland, such as the cT3a or seminal gland, in patients with PCa grade T3b. (14) (15) In contrast, single-type seed implants may lead to seed migration, especially when urologists try to implant a single seed on the far distal (apex of the prostate) side. The bloodstream from the needle hole and negative pressure may cause this phenomenon; urologists and radiation oncologists may experience stress when it occurs, resulting in inaccurate implantation and dosimetry distributions. Considering this information, linked strand-type seeds may be the gold standard for implantation.

5. Advances in tri-modality therapy, salvage brachytherapy, focal therapy, and future robotic brachytherapy development: openness to new challenging procedures of LDR brachytherapy

5.1. Tri-modality therapy for locally advanced PCa and adverse events after tri-modality therapy

The efficacy of tri-modality therapy for patients with intermediate- and high-risk PCa has been sufficiently demonstrated. The ASCENDE-RT study reported that tri-modality therapy was superior to high-dose external beam radiation therapy combined with hormonal therapy for intermediate-to-high-risk PCa. In the study, the 5-, 7-, and 9-year biochemical failure ratios were respectively 89%, 86%, and 83% in the tri-modality group versus 84%, 75%, and 62% in the hormonal therapy group. Median follow-up was 6.5 years. No significant difference in overall survival was observed between the two treatment modalities. (16) Mari et al. reported the outcomes and unfavorable prognostic factors in patients with PCa stage T3a treated with trimodal therapy. During a median follow-up of 71 months, the biochemical failure-free survival (BFFS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), and overall survival rates were 44%, 82%, and 76%, respectively. (17) Another study with a long-term follow-up of 7 years after tri-modality therapy for patients with PCa stage T3 showed an approximately 70% biochemical recurrence-free survival ratio. (14) Zhang et al. demonstrated the efficacy of tri-modality therapy in patients with intermediate- and high-risk PCa. The study showed BFFS, CSS, and overall survival rates of 76.6%, 89.1%, and 87.5%, respectively, during the median follow-up of 60 months. (18) Another study reported that patients with high-risk PCa and a Gleason score of 9-10 showed better clinical outcomes, including pCa-specific mortality and longer time to distant metastasis, than the radical prostatectomy group. (19) These results indicate that tri-modality therapy can reach effective radiation doses required to suppress PSA elevation in patients with intermediate-to-high-risk PCa. The American Brachytherapy Society also recommends androgen deprivation therapy for patients with intermediate-to-high-risk PCa. (6)

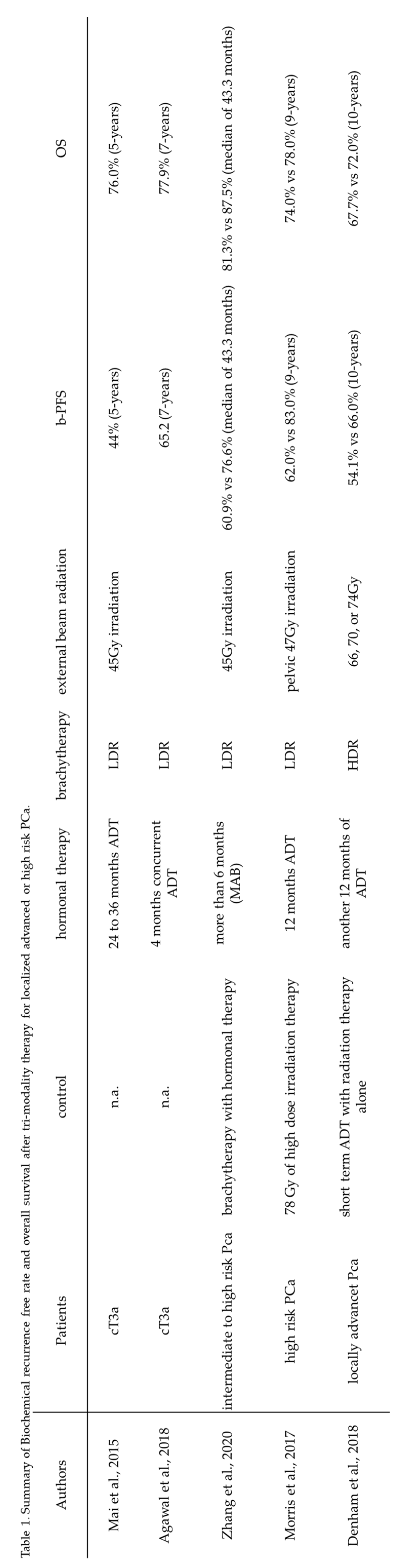

Table 1 summarizes findings from the studies on tri-modality therapy for locally advanced PCa. Subsequent treatment after the biochemical failure of external beam radiation therapy combined with hormonal therapy may be associated with the equivalent overall survival ratio in the two modality groups. Regarding hormonal therapy, previous reports showed that high-dose external beam radiation therapy combined with hormonal therapy decreased PSA biochemical recurrence and improved the overall survival of patients with locally advanced or recurrent PCa. (20) (21) Therefore, hormonal therapy is essential to achieve good clinical outcomes in patients with advanced PCa.

Table 1.

Summary of biochemical recurrence-free and overall survival rates after tri-modality therapy for localized advanced or high-risk PCa. b-PFS: biochemical progression-free survival, OS: Overall survival, ADT: Androgen deprivation therapy, MAB: Maximal androgen blockade.

Table 1.

Summary of biochemical recurrence-free and overall survival rates after tri-modality therapy for localized advanced or high-risk PCa. b-PFS: biochemical progression-free survival, OS: Overall survival, ADT: Androgen deprivation therapy, MAB: Maximal androgen blockade.

Physicians, including urologists, should realize that patients with PCa and PSA biochemical recurrence exhibit different degrees of disease progression. A previous study reported a group of patients that showed early disease progression with PSA elevation and suppression paralleled disease control. (22) This group of patients may benefit from PSA suppression therapy. Another patient group showed late disease progression with gradual elevation in PSA levels. PSA suppression therapy had a lower effect on overall survival in this group. Another report by Martin et al. showed that brachytherapy alone may be effective in a specific subgroup of patients with intermediate PCa. (23) Brachytherapy alone potentially delivers a lower radiation dose to the urethra and rectum than brachytherapy combined with external beam radiation therapy. (24) In clinical practice, patients with PCa who demonstrated a large prostate volume, showed PSA levels of >10, and were classified as the intermediate-risk group demonstrated good responses to brachytherapy alone. Therefore, the incidence of external beam radiation-induced dysuria and proctitis was lower in studies in which more patients with intermediate PCa could be treated with brachytherapy alone.

Furthermore, some studies have elucidated the shadow points associated with brachytherapy. Dysuria can occur after brachytherapy combined with external beam radiation therapy. (25) These urinary symptoms generally resolve within 1 year after implantation. (6) Proctitis has been reported to occur after brachytherapy in 2.9–5.7% of patients with PCa. (26) (27) Herein, proctitis after brachytherapy for pelvic cancer, including PCa, was associated with older age and higher radiation dose. (28) Therefore, the injection of a temporary hydrogel in the plane between the prostate and rectum, known as a hydrogel spacer, has been widely used for brachytherapy alone and brachytherapy combined with external beam radiation therapy. The hydrogel spacer is a bioabsorbable gel used to protect the rectum and surrounding tissues during radiation therapy of the prostate. Moroiados et al. reported that patients who received external beam radiation therapy using the hydrogel spacer showed a lower rectal radiation dose and fewer adverse events. (29) Placement of the hydrogel spacer may increase post-void urine volume in the bladder; however, it does not affect the urinary symptom score. (30) The other side effect of brachytherapy is the potential occurrence of erectile dysfunction (ED) after treatment; ED may be associated with the total dose of external beam radiation and the patient’s age. (31) In a real-world scenario, outpatients who underwent brachytherapy stated that they could achieve an erection but experienced less erectile hardness and could achieve orgasm but ejaculated less semen after treatment than before treatment. (32)

5.2. Salvage brachytherapy for PCa

Another useful strategy of LDR brachytherapy for PCa is salvage LDR brachytherapy after external beam radiation. Juanita et al. reported the efficacy of salvage LDR brachytherapy in a phase II clinical trial. (33) In the study, patients received external beam radiation therapy with 74 Gy for 30 months before registration. Patients with favorable- or intermediate-risk PCa with PSA <20 ng/ml, Gleason score <7, and clinical T stage T2c or less were included. The last follow-up duration was 5 years, and the disease-free, biochemical recurrence-free, and overall survival rates were 19%, 46%, and 70%, respectively. Yamada et al. reported the efficacy of salvage brachytherapy. (34) In the study, target lesions were detected using 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and prostate biopsy with template methods fused to MRI images. Ultrafocal, hemi-salvage, or whole-salvage brachytherapy was performed according to suspected positive PCa lesions. Biochemical PSA failure was observed in 0/3, 1/5, and 3/5 cases at 48 months of follow-up. The biochemical progression-free survival rate was 75% over 4 years. Therefore, salvage focal brachytherapy may be less invasive for small focal procedures.

5.3. Focal brachytherapy for PCa

Focal LDR brachytherapy for localized PCa has recently been reported. (35) (36) Minh-Hanh et al. demonstrated satisfactory 5-year biochemical relapse-free, disease-free, and overall survival rates of 96.8%, 79.5%, and 100%, respectively. However, one limitation of the study is that only patients with low-to-intermediate risk PCa were included. (36) Langrey et al. and Laing et al. reported that hemi-prostate gland brachytherapy showed good clinical outcomes similar to those of whole-gland prostate brachytherapy in terms of PSA control and overall survival. (37) (38) Elliot et al. demonstrated the efficacy of focal LDR brachytherapy. In the study, 26 patients with low-to-intermediate risk PCa were treated with focal brachytherapy, and the data on adverse events and oncological outcomes were retrospectively analyzed. One case of urinary retention and infection was observed among all cases. Nine (37.5%) grade 1 and seven (29.2%) grade 2 urinary dysfunction cases were observed. Eight patients with grade 2 or lower ED were also observed. A total of 21 cases were evaluated for PCa recurrence using re-biopsy and MRI detection; no patients had PCa relapse. Only one patient showed PSA recurrence, for which radical prostatectomy was performed. (39) The other report showed less genitourinary toxicity in the focal brachytherapy group than in the whole prostate LDR brachytherapy group. (35) Considering these observations, focal brachytherapy is feasible, with good clinical outcomes and less toxicity. Regarding the new generation PCa imaging methods, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) scans using positron emitters such as gallium-68 (Ga), copper-64 (Cu), and fluorine-18 (F) measured with positron emission tomography (PET) could detect PCa lesions more precisely. (40) It may be possible to obtain more accurate images of primary PCa lesions using a combination of MRI and PSMA-PET; this will help urologists select treatment options more effectively. (41) (42) PSMA-PET shows a small mass of PCa cells in the bone and soft tissue. (43) Body-ablative radiation therapy for these oligometastatic lesions can potentially suppress advanced PCa in some patients. (43) These new imaging techniques may make it possible to perform focal therapy as described. The two methods mentioned above can be combined to improve the current focal therapy procedure for PCa. (44) (45) The utility of deformable registrations of PET/computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound to target PCa was demonstrated in this report. This methodology enables physicians to implant seeds more accurately and recognize diseased lesions, prostate boundaries, and internal gland shapes, which are sometimes difficult to observe. In the future, a new imaging method comprising PSMA-PET, MRI, and more precise ultrasound may be applied for focal LDR therapy.

5.4. Current image-guided instruments for LDR’s needle puncture and future aspects

Notably, many image-guided instruments and engineered structures for needle puncture as high-precision needle insertion strategy have been invented for brachytherapy since the early 2000s. Dai et al. reported that these image-guided instruments were classified as ultrasound-, MRI-, CT-, or fused-image-guided systems. (46) Among these, ultrasound-guided systems have versatility and are the most developing approach due to the accustomed image procedure for most urologists. (47) However, although MRI-guided systems were superior in image accuracy of the prostate, they should be applied with special devices usable in the magnetic field. MRI-guided systems have a limitation of expensive power sources of piezoelectric actuation. (46) CT-guided system also has a limitation of radiation exposure for both patients and urologists who deliver seeds manually. (48) Currently, these mechanical instruments assist urologists in performing punctures without a conventional puncture template board, according to the intraoperative plan of radiation oncologists. The priority of these systems is to provide more precise puncture. Other merits of these systems were safety control of puncture with confirmation of needle position. With these systems, urologists and radiation oncologists can take checks for subsequent procedures. (48) (49) (47)

Using these robots, LDR-induced complications and unfavorable events could be avoided, including the puncture line of the needle deviating from the site where the radiation source should be placed, patient fatigue caused by longer operation time, increased operator exposure due to extended surgical time, and differences in clinical outcomes between operators. According to the following reports, image-guided instruments for brachytherapy improved clinical outcomes. Podder et al. reported that brachytherapy with image-guided assist instruments achieved more accurate seed placement. Sufficient dosimetric coverage of the prostate was obtained as in the manual method; however, the number of needles used was reportedly reduced by 30.5%. (50) Furthermore, the same group reported that the number of implanted seeds decreased by 11.8%, and the urethral and rectal radiation doses were reduced, making it possible to perform safer brachytherapy. (51) However, these image-guided instruments for brachytherapy still have limitations. In the case of a narrow public arch, it is difficult to place the seeds in the prostate marginal area; therefore, a technical system is required to advance the needle bending itself. In addition, future technical tasks include developing an automatic needle-loading system and a robotic system that places the seeds.

One group from China is examining the future directions of brachytherapy regarding prostate needling. (52) This group invented a mechanical frame to perform brachytherapy needling automatically. These implant systems can help surgeons avoid exposure to radioactive seeds during brachytherapy. The brachytherapy operation time can also be shortened with quick loading and setting steps. Furthermore, human errors during seed counting can also be decreased. Recent progress in artificial intelligence (AI) can also aid implant planning, which is currently being performed by radiation oncologists. In the future, brachytherapy in clinics may be performed automatically by robotic systems guided by AI.

6. Conclusions

LDR brachytherapy alone has shown satisfactory clinical outcomes in patients with localized low-to-intermediate PCa. In addition, combination therapy comprising LDR brachytherapy and external beam radiation and hormone therapies have achieved beneficial outcomes in patients with localized high-risk PCa. Therefore, physicians should consider utilizing the full potential of LDR brachytherapy in treating PCa. These observed promising results stem from the combined efforts of urologists and radiation oncologists setting precise seeds in the prostate. Currently, LDR brachytherapy is performed by urologists in operating rooms. In the future, novel implantation systems, such as robot-assisted systems, may be used for LDR implantation. However, the ability of urologists to implant precise seeds to treat patients with PCa should be lauded.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K.; software, S.H.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, G.K.; investigation, S.T.; resources, M.K.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, T.K.; project administration, T.I.; funding acquisition, T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Aichi Cancer Center donation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ihe study was not applicable for institutional review board statement.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is inapplicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The English language was corrected by the English editing company “editage.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gandaglia G, Leni R, Bray F, Fleshner N, Freedland SJ, Kibel A, et al. Epidemiology and Prevention of Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2021, 4, 877–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakehi Y, Sugimoto M, Taoka R, committee for establishment of the evidenced-based clinical practice guideline for prostate cancer of the Japanese Urological A. Evidenced-based clinical practice guideline for prostate cancer (summary: Japanese Urological Association, 2016 edition). Int J Urol. 2017, 24, 648–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilt TJ, Ullman KE, Linskens EJ, MacDonald R, Brasure M, Ester E, et al. Therapies for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: A Comparative Effectiveness Review. J Urol. 2021, 205, 967–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelefsky MJ, Chou JF, Pei X, Yamada Y, Kollmeier M, Cox B, et al. Predicting biochemical tumor control after brachytherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Brachytherapy. 2012, 11, 245–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka N, Asakawa I, Hasegawa M, Fujimoto K. Low-dose-rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer: A 15-year experience in Japan. Int J Urol. 2020, 27, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King MT, Keyes M, Frank SJ, Crook JM, Butler WM, Rossi PJ, et al. Low dose rate brachytherapy for primary treatment of localized prostate cancer: A systemic review and executive summary of an evidence-based consensus statement. Brachytherapy. 2021, 20, 1114–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka N, Asakawa I, Nakai Y, Miyake M, Anai S, Fujii T, et al. Comparison of PSA value at last follow-up of patients who underwent low-dose rate brachytherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017, 17, 573. [Google Scholar]

- Prada PJ, Juan G, Fernandez J, Gonzalez-Suarez H, Martinez A, Gonzalez J, et al. Conformal prostate brachytherapy guided by realtime dynamic dose calculations using permanent 125iodine implants: technical description and preliminary experience. Arch Esp Urol. 2006, 59, 933–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo N, Dehghan E, Deguet A, Mian OY, Le Y, Burdette EC, et al. An image-guidance system for dynamic dose calculation in prostate brachytherapy using ultrasound and fluoroscopy. Med Phys. 2014, 41, 091712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki K, Kiba T, Sasaki H, Kido M, Aoki M, Takahashi H, et al. Transperineal prostate brachytherapy, using I-125 seed with or without adjuvant androgen deprivation, in patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: study protocol for a phase III, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2010, 10, 572. [Google Scholar]

- Konaka H, Egawa S, Saito S, Yorozu A, Takahashi H, Miyakoda K, et al. Tri-Modality therapy with I-125 brachytherapy, external beam radiation therapy, and short- or long-term hormone therapy for high-risk localized prostate cancer (TRIP): study protocol for a phase III, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2012, 12, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Bockholt NA, DeRoo EM, Nepple KG, Modrick JM, Smith MC, Fallon B, et al. First 100 cases at a low volume prostate brachytherapy institution: learning curve and the importance of continuous quality improvement. Can J Urol. 2013, 20, 6907–12. [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp H, Nuver TT, Moerland MA, Minken AW. An automated, fast and accurate registration method to link stranded seeds in permanent prostate implants. Phys Med Biol. 2015, 60, N391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal M, Chhabra AM, Amin N, Braccioforte MH, Molitoris JK, Moran BJ. Long-term outcomes analysis of low-dose-rate brachytherapy in clinically T3 high-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018, 17, 882–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, M. Editorial Comment to Coverage of the external prostatic region by the hybrid method compared with the conventional method of prostate low-dose-rate brachytherapy: A randomized controlled study. Int J Urol. 2020, 27, 1017–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris WJ, Tyldesley S, Rodda S, Halperin R, Pai H, McKenzie M, et al. Androgen Suppression Combined with Elective Nodal and Dose Escalated Radiation Therapy (the ASCENDE-RT Trial): An Analysis of Survival Endpoints for a Randomized Trial Comparing a Low-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy Boost to a Dose-Escalated External Beam Boost for High- and Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017, 98, 275–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mai ZP, Yan WG, Li HZ, Zhou Y, Zhou ZE. Outcomes of T3a Prostate Cancer with Unfavorable Prognostic Factors Treated with Brachytherapy Combined with External Radiotherapy and Hormone Therapy. Chin Med Sci J. 2015, 30, 143–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Zhou H, Qin M, Zhang X, Zhang J, Chai S, et al. Efficacy of brachytherapy combined with endocrine therapy and external beam radiotherapy in the treatment of intermediate and high-risk localized prostate cancer. J BUON. 2020, 25, 2405–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kishan AU, Cook RR, Ciezki JP, Ross AE, Pomerantz MM, Nguyen PL, et al. Radical Prostatectomy, External Beam Radiotherapy, or External Beam Radiotherapy With Brachytherapy Boost and Disease Progression and Mortality in Patients With Gleason Score 9-10 Prostate Cancer. JAMA. 2018, 319, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham JW, Joseph D, Lamb DS, Spry NA, Duchesne G, Matthews J, et al. Short-term androgen suppression and radiotherapy versus intermediate-term androgen suppression and radiotherapy, with or without zoledronic acid, in men with locally advanced prostate cancer (TROG 03.04 RADAR): 10-year results from a randomised, phase 3, factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 267–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley WU, Seiferheld W, Lukka HR, Major PP, Heney NM, Grignon DJ, et al. Radiation with or without Antiandrogen Therapy in Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 417–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, Loeb S, Johnson DC, Reiter RE, et al. Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King MT, Chen MH, Moran BJ, Braccioforte MH, Buzurovic I, Muralidhar V, et al. Brachytherapy monotherapy may be sufficient for a subset of patients with unfavorable intermediate risk prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018, 36, 157–e15. [Google Scholar]

- Wallner K, Roy J, Harrison L. Dosimetry guidelines to minimize urethral and rectal morbidity following transperineal I-125 prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995, 32, 465–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodda S, Tyldesley S, Morris WJ, Keyes M, Halperin R, Pai H, et al. ASCENDE-RT: An Analysis of Treatment-Related Morbidity for a Randomized Trial Comparing a Low-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy Boost with a Dose-Escalated External Beam Boost for High- and Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017, 98, 286–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi T, Yorozu A, Toya K, Saito S, Momma T, Nagata H, et al. Rectal morbidity following I-125 prostate brachytherapy in relation to dosimetry. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007, 37, 121–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka T, Yorozu A, Sutani S, Yagi Y, Nishiyama T, Shiraishi Y, et al. Predictive factors of long-term rectal toxicity following permanent iodine-125 prostate brachytherapy with or without supplemental external beam radiation therapy in 2216 patients. Brachytherapy. 2018, 17, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidinezhad F, Willems Y, Berbee M, Limbergen EV, Verhaegen F, Dekker A, et al. Prediction models for brachytherapy-induced rectal toxicity in patients with locally advanced pelvic cancers: a systematic review. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2022, 14, 411–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariados N, Sylvester J, Shah D, Karsh L, Hudes R, Beyer D, et al. Hydrogel Spacer Prospective Multicenter Randomized Controlled Pivotal Trial: Dosimetric and Clinical Effects of Perirectal Spacer Application in Men Undergoing Prostate Image Guided Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015, 92, 971–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi T, Iinuma K, Nakano M, Kawase M, Takeuchi S, Kato D, et al. Chronological changes of lower urinary tract symptoms after low-dose-rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer using SpaceOAR(R) system. Prostate Int. 2022, 10, 207–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, Galbreath RW, Anderson RL, Kurko BS, et al. Erectile function after prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005, 62, 437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie X, Zhang Y, Ge C, Liang P. Effect of Brachytherapy vs. External Beam Radiotherapy on Sexual Function in Patients With Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 792597. [Google Scholar]

- Crook J, Rodgers JP, Pisansky TM, Trabulsi EJ, Amin MB, Bice W, et al. Salvage Low-Dose-Rate Prostate Brachytherapy: Clinical Outcomes of a Phase 2 Trial for Local Recurrence after External Beam Radiation Therapy (NRG Oncology/RTOG 0526). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022, 112, 1115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada Y, Okihara K, Masui K, Ueno A, Shiraishi T, Nakamura Y, et al. Focal salvage low-dose-rate brachytherapy for recurrent prostate cancer based on magnetic resonance imaging/transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsy technique. Int J Urol. 2020, 27, 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim TH, Kim JN, Yu YD, Lee SR, Hong YK, Shin HS, et al. Feasibility and early toxicity of focal or partial brachytherapy in prostate cancer patients. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2020, 12, 420–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta MH, Nunes-Silva I, Barret E, Renard-Penna R, Rozet F, Mombet A, et al. Focal Brachytherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: Midterm Outcomes. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021, 11, e477–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley S, Uribe J, Uribe-Lewis S, Mehta S, Mikropoulos C, Perna C, et al. Is hemi-gland focal LDR brachytherapy as effective as whole-gland treatment for unilateral prostate cancer? Brachytherapy. 2022, 21, 870–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing R, Franklin A, Uribe J, Horton A, Uribe-Lewis S, Langley S. Hemi-gland focal low dose rate prostate brachytherapy: An analysis of dosimetric outcomes. Radiother Oncol. 2016, 121, 310–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson E, Smyth LML, O'Sullivan R, Ryan A, Lawrentschuk N, Grummet J, et al. Focal low dose-rate brachytherapy for low to intermediate risk prostate cancer: preliminary experience at an Australian institution. Transl Androl Urol. 2021, 10, 3591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai BP, Baum RP, Patel A, Hughes R, Alonzi R, Lane T, et al. The Role of Positron Emission Tomography With (68)Gallium (Ga)-Labeled Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) in the Management of Patients With Organ-confined and Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer Prior to Radical Treatment and After Radical Prostatectomy. Urology. 2016, 95, 11–5. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista L, Zattoni F, Cassarino G, Artioli P, Cecchin D, Dal Moro F, et al. PET/MRI in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021, 48, 859–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi C, Fernandez-Pascual E, Arcaniolo D, Emberton M, Sanchez-Salas R, Artigas Guix C, et al. The Role of Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Primary and Recurrent Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Eur Urol Focus. 2022, 8, 942–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong WL, Koh TL, Lim Joon D, Chao M, Farrugia B, Lau E, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PSMA-PET/CT)-guided stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer: a single-institution experience and review of the published literature. BJU Int. 2019;124 Suppl 1:19-30.

- Sultana S, Song DY, Lee J. Deformable registration of PET/CT and ultrasound for disease-targeted focal prostate brachytherapy. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2019, 6, 035003. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana S, Song DY, Lee J. A deformable multimodal image registration using PET/CT and TRUS for intraoperative focal prostate brachytherapy. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2019;10951.

- Dai X, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Li B. Image-guided robots for low dose rate prostate brachytherapy: Perspectives on safety in design and use. Int J Med Robot. 2021, 17, e2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtinger G, Fiene JP, Kennedy CW, Kronreif G, Iordachita I, Song DY, et al. Robotic assistance for ultrasound-guided prostate brachytherapy. Med Image Anal. 2008, 12, 535–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtinger G, DeWeese TL, Patriciu A, Tanacs A, Mazilu D, Anderson JH, et al. System for robotically assisted prostate biopsy and therapy with intraoperative CT guidance. Acad Radiol. 2002, 9, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer GS, Iordachita I, Csoma C, Tokuda J, Dimaio SP, Tempany CM, et al. MRI-Compatible Pneumatic Robot for Transperineal Prostate Needle Placement. IEEE ASME Trans Mechatron. 2008, 13, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder TK, Dicker AP, Hutapea P, Darvish K, Yu Y. A novel curvilinear approach for prostate seed implantation. Med Phys. 2012, 39, 1887–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder TK, Beaulieu L, Caldwell B, Cormack RA, Crass JB, Dicker AP, et al. AAPM and GEC-ESTRO guidelines for image-guided robotic brachytherapy: report of Task Group 192. Med Phys. 2014, 41, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhang Y, Zuo S, Xu Y. A review of the research progress of interventional medical equipment and methods for prostate cancer. Int J Med Robot. 2021, 17, e2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).