Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Determination of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies Level

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

| After 2nd dose | After 3rd dose | After 4th dose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | 142 | 76 | 25 |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 67 (56.75-75) | 66.5 (57-74.75) | 72 (67.5-79) |

| Male, (%) | 78 (54.9) | 43 (56.6) | 15 (60) |

| Time from last BNT162b2 dose, median days (IQR) | 35 (24.5-46.25) | 147 (130.5-160.8) | 18 (12-25) |

| Type of Cancer, n (%) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 49 (34.5) | 42 (55.3) | 10 (40) |

| Breast | 30 (21.1) | 12 (15.8) | 3 (12) |

| Lung | 28 (19.7) | 10 (22.7) | 6 (24) |

| Urinary | 13 (9.2) | 3 (3.9) | 2 (8) |

| Melanoma | 7 (4.9) | 4 (5.3) | 3 (12) |

| Gynecological | 9 (6.3) | 2 (2.6) | 0 |

| Other types | 6 (4.2) | 3 (3.94) | 1 (4) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 73 (51.4) | 56 (73.7) | 13 (52) |

| Non Chemotherapy | 69 (48.6) | 20 (26.3) | 12 (48) |

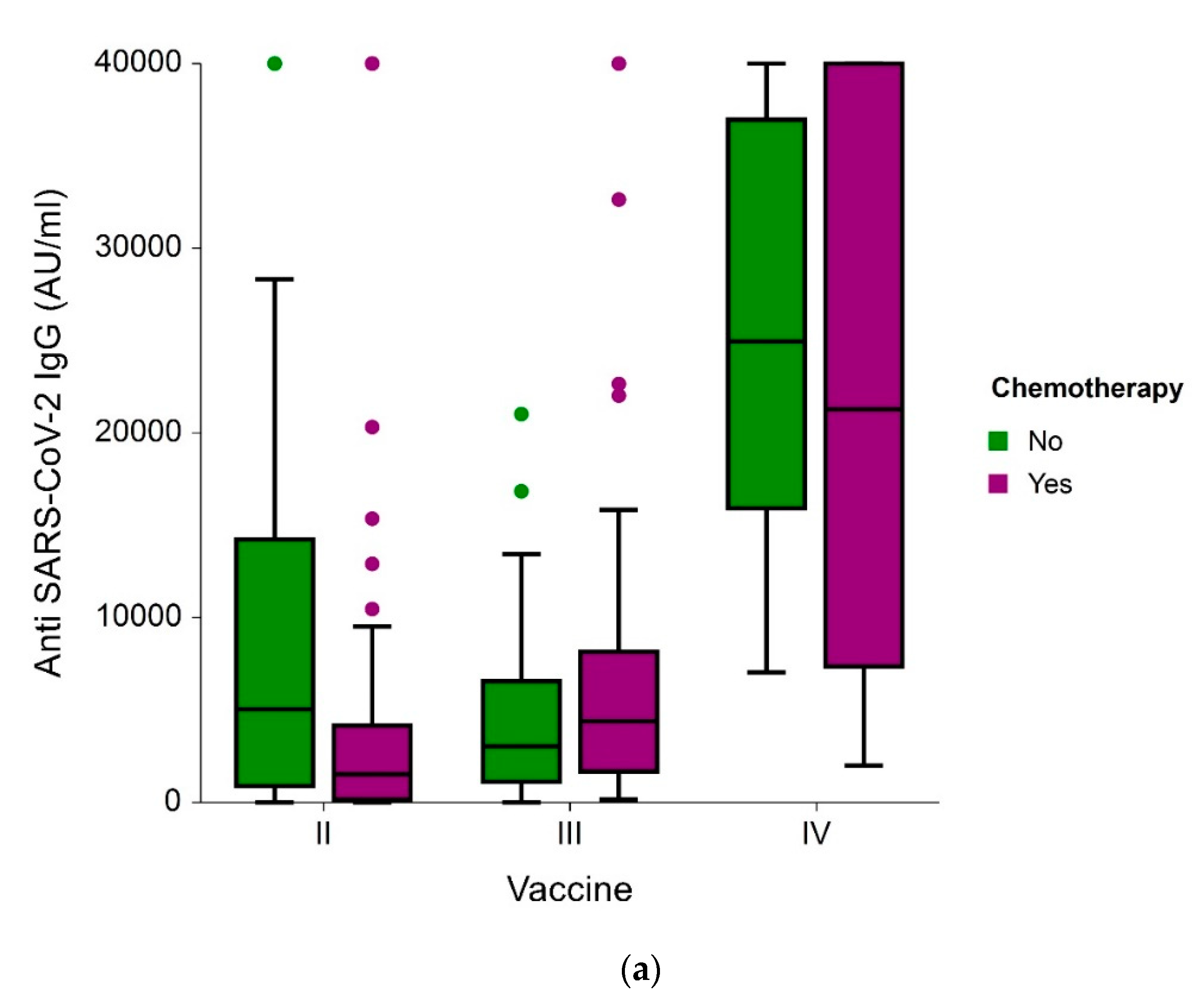

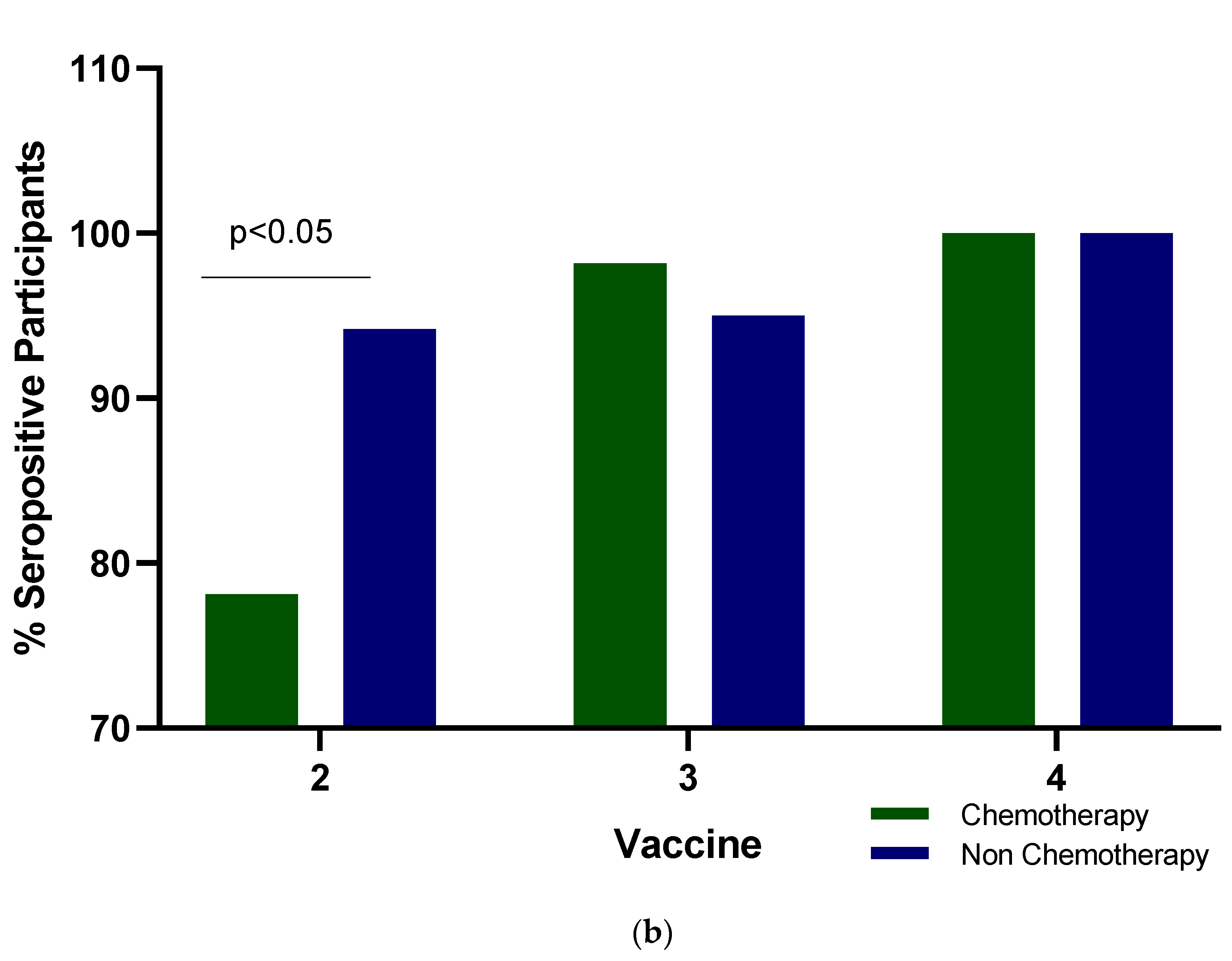

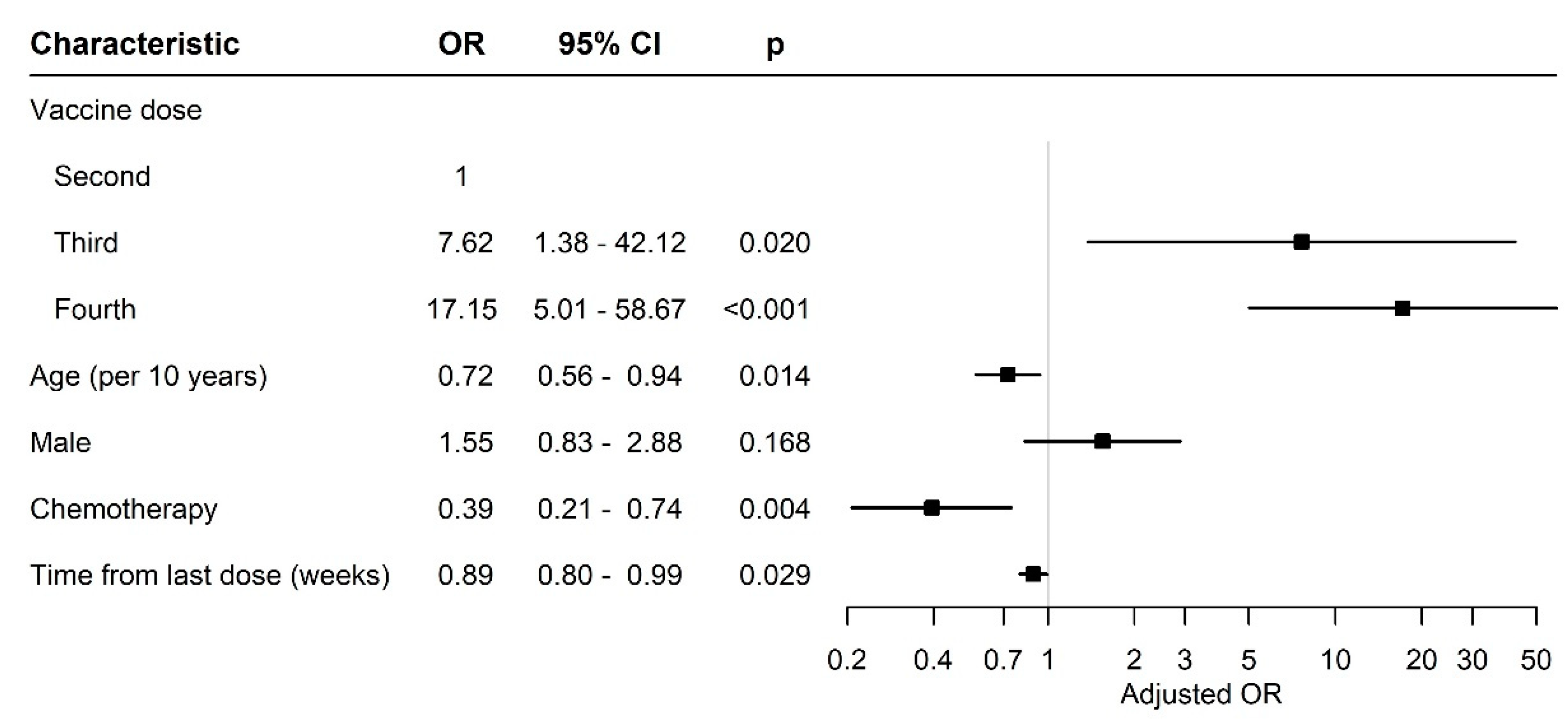

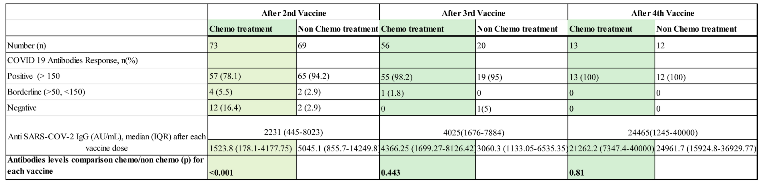

3.2. Antibody Levels and Seropositivity Response to BNT162b2 Vaccine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Ciotti, M.; Ciccozz,i M.;Terrinoni, A.; Jiang, W.C.; Wang, C.B.; Bernardini, S. The COVID-19 pandemic. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2020, 57(6), 365-388. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.; Krammer, F.; Iwasaki, A. The first 12 months of COVID-19: a timeline of immunological insights. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 245–256. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00522-1.

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Medica Briefing COVID-19. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-themedia-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020 (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Dai, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, M.; Zhou, F.; Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; You, H.; Wu, M.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: A multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 783–791.

- Stainer, A.; Amati, F.; Suigo, G.; Simonetta, E.; Gramegna, A.; Voza, A.; Aliberti S. COVID-19 in Immunocompromised Patients: A Systematic Review. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 42(6), 839-858. [CrossRef]

- Sengar, M.; Chinnaswamy, G.; Ranganathan, P.; et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 and risk factors in patients with cancer. Nat. Cancer. 2022, 3, 547–551. [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.; Moss, C.L.; Shah, V.; et al. Risk of COVID-19 death in cancer patients: an analysis from Guy’s Cancer Centre and King’s College Hospital in London. Br. J. Cancer. 2021, 125, 939–947.

- Seth, G.; Sethi, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Saini, G.; Bhushan-Singh, C.; Aneja, R. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Cancer Patients: Effects on Disease Outcomes and Patient Prognosis. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12(11), 3266. [CrossRef]

- Hiam-Galvez, K.J.; Allen, B.M.; Spitzer MH. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021, 21(6), 345-359. [CrossRef]

- Norris, J. Tumors Disrupt the Immune System Throughout the Body. University of California San Francisco 2020, Tumors Disrupt the Immune System Throughout the Body | UC San Francisco (ucsf.edu) (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Teo S.P. Review of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines: BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273. J. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 35(6), 947-951. [CrossRef]

- The Food and Drug Administration. Available online: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Additional Vaccine Dose for Certain Immunocompromised Individuals | FDA (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Rahav, G.; Lustig, Y.; Lavee, J.; Benjamini, O.; Magen H.; Hod, T.; Shem-Tov, N.; Shacham Shmueli, E.; Merkel, D.; Ben-Ari, Z.; et al. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in immunocompromised patients: A prospective cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101158. https://doi.org/.

- Massarweh, A.; Eliakim-Raz, N.; Stemmer, A.; Levy-Barda, A.; Yust-Katz, S.; Zer, A.; Benouaich-Amiel A., Ben-Zvi H.; Moskovits, N.; Brenner, B.; et al. Evaluation of Seropositivity Following BNT162b2 Messenger RNA Vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients Undergoing Treatment for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7(8), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Uaprasert, N.; Pitakkitnukun, P.; Tangcheewinsirikul, N.; Chiasakul, T.; Rojnuckarin, P. Immunogenicity and risks associated with impaired immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and booster in hematologic malignancy patients: an updated meta-analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2022, 12, 173. [CrossRef]

- Oosting, S.F.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; Fehrmann, R.S.N.; van Binnendijk, R.S.; Dingemans, A.C.; Smit, E.F.; Hiltermann, T.J.N.; den Hartog, G.; Jalving, M.; Westphal, T.T.; Bhattacharya, A.; van der Heiden, M.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; Kvistborg, P.; Blank, C.U.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Huckriede, A.L.W.; van Els, C.A.C.M.; Rots, N.Y.; van Baarle, D.; Haanen, J.B.A.G.; de Vries, E.G.E. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or chemoimmunotherapy for solid tumours: a prospective, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22(12), 1681-1691. [CrossRef]

- Stampfer, S.D., Goldwater, MS., Jew, S.; et al. Response to mRNA vaccination for COVID-19 among patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2021, 35, 3534–3541. [CrossRef]

- Dagan, N.; Barda, N.; Epten, E.; Miron, O.; Perchik, S.; Katz, M.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Reis, B.; Balicer, R.D. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Mass Vaccination Setting. N. Eng. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1412–1423. [CrossRef]

- Leshem, E.; Wilder-Smith, A. COVID-19 vaccine impact in Israel and a way out of the pandemic. Lancet 2021, 397(10287), 1783-1785. [CrossRef]

- Jeffay, N. COVID vaccine effective for 90% of cancer patients, Israeli study finds. The Times of Israel. 2021. Available on line COVID vaccine effective for 90% of cancer patients, Israeli study finds | The Times of Israel (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Agbarya, A.; Sarel, I.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Agranat, S.; Schwartz, O.; Shai, A.; Nordheimer, S.; Fenig, S.; Shechtman, Y.; Kozlener, E.; Taha, T.; Nasrallah, H.; Parikh, R.; Elkoshi, N.; Levy, C.; Khoury, R.; Brenner, R. Efficacy of the mRNA-Based BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine in Patients with Solid Malignancies Treated with Anti-Neoplastic Drugs. Cancers, 2021, 13(16), 4191. [CrossRef]

- Isasi, F.; Naylor, M.D., Skorton, D.; Grabowski, D.C.; Hernández, S.; Montomery Rice, V. Patients, Families, and Communities COVID-19 Impact Assessment: Lessons Learned and Compelling Needs. NAM Perspect. 2021, 2021: 1.31478/202111c. [CrossRef]

- Koc, H.C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, G. Long COVID and its management. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18(12), 4768-4780. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Chapter 2. Current context: the COVID-19 pandemic and continuing challenges to global health. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/funding/invest-in-who/investment-case-2.0/challenges: (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Fekadu, G.; Bekele, F.; Tolossa, T.; Fetensa, G.; Turi, E.; Getachew, M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on chronic diseases care follow-up and current perspectives in low resource settings: a narrative review. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 13(3), 86-93.

- Kang S.J.; Jung, S.I. Age related Morbidity and mortalities among Patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020, 52(2), 154-164. [CrossRef]

- Tassone, D.; Thompson, A.; Connell, W.; Lee, T.; Ungaro, R.; An, P.; Ding, Y.; Ding, N.S. Immunosuppression as a risk factor for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Intern. Med. J. 2021 51(2), 199-205. [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.K.; Liu C.; Dadwal, S.S. Infectious Disease Complications in Cancer Patients. Crit Care Clin. 2021, 37(1), 69-84. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.H.J.; Sparks, J.A. Immunosuppression and SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections. Lancet Rheumatology. 2022, COMMENT 4 (6), E379-E380. https://doi.org/.

- Trapani, D.; Curlgliano, G. COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22(6), 738-739. https://doi.org/.

- Monin, L.; Laing, A.G.; Munoz-Ruiz, M.; McKenzie, D.R.; del Molino del Barrio, I.; Alaguthurai, T.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22(6), 765-778. https://doi.org/.

- Guven, D.C.; Sahin, T.K.; Klickap, S.; Uckun, F.M. Antibody Responses to COVID-19 Vaccination in Cancer: A Systematic Review. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fendler, A.; de Vries, E.G.E; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; Haanen, J.B.; Wörmann, B.; Turajlic, S.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, M. COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer: immunogenicity, efficacy and safety. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 385–401. [CrossRef]

- Kamar, N.; Abravenel, F.; Narion, O.; Couat, C.; Izopet, J.; Del Bello, A. Three Doses of an mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385(7),661-662. [CrossRef]

- Benotmane, I.; Gautier, G.; Perrin, P.; et al. Antibody Response After a Third dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients With Minimal Serologic Response to 2 Doses. JAMA 2021, 326(11), 1063-1065. [CrossRef]

- Rüthrich, M.M.; Giesen, N.; Mellinghoff, S.C.; Rieger, C.T.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, N.Cellular Immune Response after Vaccination in Patients with Cancer-Review on Past and Present Experiences. Vaccines 2022, 10(2), 182. [CrossRef]

- Negahdaripour, M.; Shafiekhani, M.; Iman Moezzi, S.M.; Amiri, S.; Rasekh, S.; Bagheri, A.; Mosaddeghi, M.; Vazin, A. Administration of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 10802. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.; Campisi-Pfinto, S.; Rozenberg, O.; Colodner, R.; Bar-Sela, G. The Humoral Response of Patients With Cancer to Breakthrough COVID-19 Infection or the Fourth BNT162b2 Vaccine dose. Oncologist 2023, 28(4), e225-e227. [CrossRef]

- Magen, O.; Waxman, J.G.; Makov-Assif, M.; Vered, R.; Dicker, D.; Hernán M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Reis, B.Y.; Balicer, R.D.; Dagan, N. Fourth Dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386(17), 1603-1614. [CrossRef]

- Curlin M.E.; Bates, T.A.; Guzman, G.; Schoen, D.; McBride, S.K.; Carpenter, S.D.; Tafesse F.G. Omicron neutralizing antibody response following booster vaccination compared with breakthrough infection. medRxiv. 2022, 2022.04.11.22273694. [CrossRef]

- Lasagna A, Bergami F, Lilleri D, Percivalle E, Quaccini M, Alessio N, Comolli G, Sarasini A, Sammartino JC, Ferrari A, Arena F, Secondino S, Cicognini D, Schiavo R, Lo Cascio G, Cavanna L, Baldanti F, Pedrazzoli P, Cassaniti I. Immunogenicity and safety after the third dose of BNT162b2 anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients with solid tumors on active treatment: a prospective cohort study. ESMO Open 2022, 7(2),100458. [CrossRef]

- Di Noia, V.; Pimpinelli, F.; Renna, D.; Campo, F.; Cosimati, A.; Torchia, A.; Marcozzi, B.; Massacci, A.; Pallocca, M.; Pellini, R.; Morrone, A.; Cognetti, F. Duration of humoral response to the third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with solid cancer: Is fourth dose urgently needed? Eur. J. Cancer. 2022, 176, 164–167. [CrossRef]

- Shroff, R.T.; Chalasani, P.; Wei, R.; Pennington, D.; Quirk, G.; Schoenle, M.V.; et al. Immune responses to two and three doses of the BNT162b mRNA vaccine in adults with solid tumors. Nat. Med. 2021, 27(11):2002-2011. [CrossRef]

- Shacham Shmueli, E.; Lawrence, Y.R.; Rahav, G.; Itay, A.; Lustig, Y.; Halpern, N.; Boursi, B.; Margalit, O. Serological response to a third booster dose of BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine among seronegative cancer patients. Cancer Rep. (Hoboken) 2022, 5(8), e1645. [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.G.; Lustig, Y.; Cohen, C.; Fluss, R.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Doolman, R.; Asraf, K.; Mendelson, E.; Ziv, A.; Rubin, C.; Freedman, L.; et al. Waning Immune Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine over 6 Months. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e84. [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Karalis, V.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Gavariatopoulou, M.; Gumeni, S.; Malandrakis, P.; et al. Robust Neutralizing Antibody Responses 6 Months post Vaccination with BNT162b2: A Prospective study in 308 Health Individuals. Life 2021, 11(10), 1077. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Y.; Mandel, M.; Bar-on, Y.M.; Bodenheimer, O.; Freedman, L.; Haas, E.J.; Milo, R.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Ash, N.; Huppert, A. Waning Immunity after the BNT162b2 Vaccine in Israel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e85. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.Y.B.; Wong, S.Y.; Chai, L.Y.A.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, M.X.; Muthiah, M.D.; Tay, S.H.; Teo, C.B.; Tan, B.K.J.; Chan, Y.H.; Sundar, R.; Soon, Y.Y. Efficacy of covid-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022, 376:e068632. [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.R.F., Almeida, N.B.F., Filgueiras, P.S. et al. Booster dose of BNT162b2 after two doses of CoronaVac improves neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 76. [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Goldberg, Y.; Mandel, M.; Bodenheimer, O.; Freedman, L.; Kalkstein, N.; Mizrahi, B.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Ash, N.; Milo, R.; Huppert, A. Protection of BNT162b2 Vaccine Booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, NEJMoa2114255. [CrossRef]

- Falsey, A.R.; Frenck, R.W.; Walsh, E.E.; Kitchin, N.; Abslon, J.; Gurtman, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization with BNT162b2 Vaccine Dose 3. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, NEHMc2113468. [CrossRef]

- Ligumsky, H.; Dor, H.; Etan, T.; Golomb, I.; Nikolaevski-Berlin, A.; Greenberg, I.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine booster in actively treated patients with cancer. The Lancet Oncology 2021, 23(2), 193-195. https://doi.org/.

- Vietri, M.T.; Albanese, L.; Passariello, L.; D'Elia, G.; Caliendo, G.; Molinari, A.M.; Angelillo, I.F. Evaluation of neutralizing antibodies after vaccine BNT162b2: Preliminary data. J. Clin. Virol. 2022, 146,105057. [CrossRef]

- Vietri, M.T.; DeElia, G.; Caliendo, G.; Passariello, L.; Albanese, L.; Molinari, A.M.; Angelillo I.F. Antibody levels after BNT162b2 vaccine booster and SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection. Vaccine 2022, 40(39), 5726-5731. [CrossRef]

- Gray-Gaillard, S.L.; Solis, S.; Monteiro, C.; Chen, H.M.; Ciabattoni, G.; Samanovic, M.I.; Cornelius, A.R.; Williams, T.; Geesey, E.; Rodriguez, M.; Ortigoza, M.B.; Ivanova, E.N.; Koralov, S.B.; Mulligan, M.J.; Herati, R.S. Molecularly distinct memory CD4+ T cells are induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection and mRNA vaccination. bioRxiv. 2022, 2022.11.15.516351. [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, F.; Ciabattini, A.; Sicuranza, A.; Pastore, G.; Santoni, A.; Simoncelli, M.; Polvere, J.; Galimberti, S.; Baratè, C.; Sammartano, V.; Montagnani, F.; Bocchia, M.; Medaglini, D. The third dose of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines enhances the spike-specific antibody and memory B cell response in myelofibrosis patients. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1017863. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, A.; Vizcarra, P.; Martin-Hondarza, A.; Gómez-Maldonado, S.; Haemmerle, J.; Velasco, H.; Casado. J.L. Impact of SARS-CoV-2-specific memory B cells on the immune response after mRNA-based Comirnaty vaccine in seronegative health care workers. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1002748. [CrossRef]

- Ciabattini, A.; Pastore, G.; Fiorino, F.; Polvere, J.; Lucchesi, S.; Pettini, E.; et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-Specific Memory B Cells Six months after vaccination With the BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Henig, I.; Isenberg, J.; Yehudai-Ofir, D.; Leiba, R.; Ringelstein-Harlev, S.; Ram, R.; Avni, B.; Amit, O.; Grisariu, S.; Azoulay,T.; Slouzkey, I.; Zuckerman, T. Third BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Dose Significantly Enhances Immunogenicity in Recipients of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Vaccines (Basel). 2023, 11(4), 775. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Yakushijin, K.; Funakoshi, Y.; Ohji,G.; Ichikawa, H.; Sakai, H.; et al.. A Third Dose COVID-19 Vaccination in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10(11),1830. [CrossRef]

- Steensels, D.; Pierlet N.; Penders, J.; et al. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Response Following Vaccination With BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273. JAMA 2021, 326(15); 1533-1535. [CrossRef]

- Dickerman, B.A.; Gerlovin, H.; Madenci, A.L.; Kurgansky K.E.; Ferolito B.R.; Figueroa Muñiz M.J.; et al. Comparative Effective ness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 Vaccines in U.S. Veterans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 105–115. [CrossRef]

- Moderna’s COVID-19 Vaccine May Be More Effective for Cancer Patients - Cancer Therapy Advisor (Accessed 9 June 2023).

- Becker, M.; Cossmann, A.; Lürken, K.; Junker, D.; Gruber, J.; Juengling, J.; et al.. Longitudinal cellular and humoral immune responses after triple BNT162b2 and fourth full-dose mRNA-1273 vaccination in haemodialysis patients. Front Immunol. 2022, 13,1004045. [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, H.; Trougakos,I.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E. Clinical usefulness of testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibodies. Eur. J. Intern Med. 2023, 107, 7–16. [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Liontos, M.; Fiste, O.; Zagouri, F.; Briasoulis, A.; Sklirou, A.D.; Markellos, C.; Skafida, E.; Papatheodoridi, A.; Andrikopoulou, A.; Koutsoukos, K.; Kaparelou, M.; Iconomidou, V.A.; Trougakos, I.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies Kinetics Postvaccination in Cancer Patients under Treatment with Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(11), 2796. [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, C.; Pagoni, M.; Rosati, M.; Angel, M.; Tzannou, I.; Vlachou, M.; Darmani, I.; Ullah, A.; Bear, J.; Devasundaram, S.; Burns, R.; Baltadakis, I.; Gigantes, S.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Pavlakis, G.N.; Terpos, E.; Felber, BK. Reduced Antibodies and Innate Cytokine Changes in SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccinated Transplant Patients With Hematological Malignancies. Front. Immunol. 2022,13,899972. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, M.; Terpos, E.; Bear, J.; Burns, R.; Devasundaram, S.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Kastritis, E.; Dimopoulos, M.-A.; Pavlakis, G.N.; et al. Low Spike Antibody Levels and Impaired BA.4/5 Neutralization in Patients with Multiple Myeloma or Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia after BNT162b2 Booster Vaccination. Cancers 2022, 14, 5816. [CrossRef]

- Liatsou, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Lykos, S.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, A.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Terpos, E. Adult Patients with Cancer Have Impaired Humoral Responses to Complete and Booster COVID-19 Vaccination, Especially Those with Hematologic Cancer on Active Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15(8), 2266. [CrossRef]

- Zagouri, F.; Papatheodoridi, A.; Liontos, M.; Briasoulis, A.; Sklirou, A.D.; Skafida, E.; Fiste, O.; Markellos, C.; Andrikopoulou, A.; Koutsoukos, K.; Kaparelou, M.; Gkogkou, E.; Trougakos, I.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E. Assessment of Postvaccination Neutralizing Antibodies Response against SARS-CoV-2 in Cancer Patients under Treatment with Targeted Agents. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(9):1474. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).