1. Introduction

Skeletal muscle is the largest tissue and representing approximately 40% of total body mass, and it is a multifunction tissue that plays a fundamental role in regular daily activities including not only motor function, respiration but also energy storage in the form of proteins within the body[

1,

2]. Moreover, skeletal muscle is the primary source of animal proteins in economical animals for human consumption. The growth and development of skeletal muscle directly affect meat production[

3]. Various feed additives, such as beta-agonists and anabolic steroids, are used in livestock to directly promote muscle growth[

4]. Beta-agonists increases skeletal muscle mass and decreases fat mass in animals by stimulating muscle protein synthesis[

5]. In addition, recombinant bovine somatotropin enhances growth rates, feed conversion, and lean meat in beef cattle[

6]. However, it is crucial to consider the disadvantage and food safety of these feed additives. Beta-agonist residues in animal meats and organs raise food safety concerns[

7], and some beta-agonists also generate risks of tachycardia, hypertension, and cardiac hypertrophy potentially leading to heart failure in animals and humans[

8]. On the other hand, anabolic steroids cause endocrine disruptions, and are reported to be associated with carcinogenic, immunotoxic, mutagenic, and teratogenic effects, leading to irreversible consequences[

9,

10]. Hence, in search of feed additives that not only are safe but also directly promote muscle growth is of utmost importance.

Phytogenic additives are derived from various plant parts, such as leaves, roots, seeds, flowers, buds, or bark, and their extracts. Some phytochemical compounds have a long history of use in human medicine and are known for their pharmacological effects[

11,

12,

13]. Owing to their natural and safe properties, phytogenic feed additives become more popular as natural alternatives than conventional additives, such as antibiotics and growth-promoting hormones[

13,

14,

15]. The majority of phytogenic feed additives are recognized for their diverse biological activities in antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, gut health and digestive-enhancing properties to promote growth performances indirectly[

16,

17,

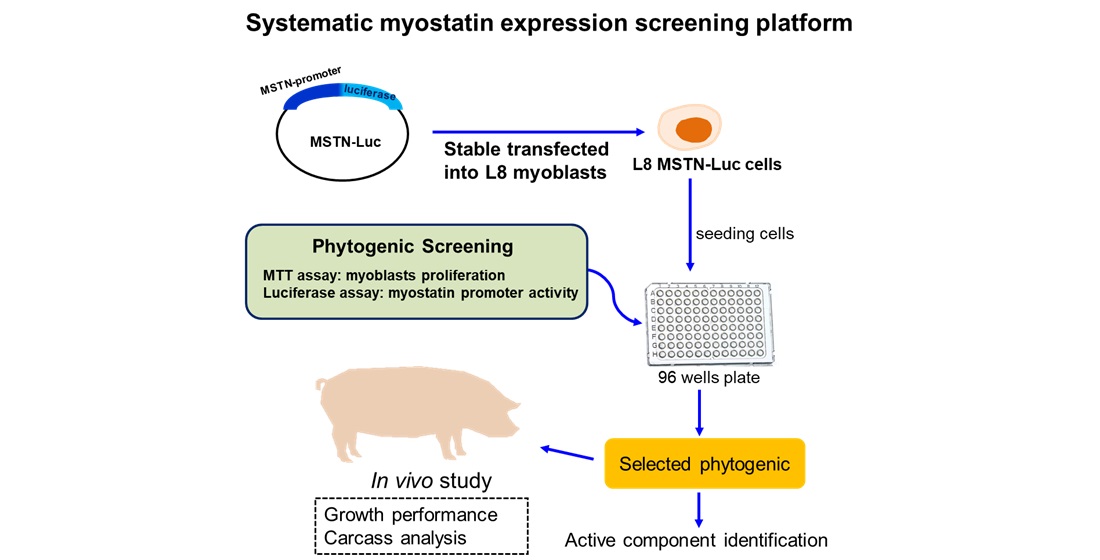

18]. However, only a limited number of phytogenic feed additives are addressed to promote skeletal muscle growth. To improve the growth performance of animals or livestock, a systematic rodent myoblast screening platform by targeting myostatin (MSTN) promoter activity was established to identify several protentional phytogenics involving myogenesis enhancement.

MSTN is a secreted protein that functions as a negative regulator of skeletal muscle development[

19,

20]. It is highly conserved among mammals, and loss-of-function mutations in this gene have been observed in various species, including cattle, sheep, pigs, rabbits, and humans. These mutations lead to increased skeletal muscle weight and the appearance of a "double-muscle" phenotype[

21,

22,

23]. Therefore, inhibition of

MSTN gene expression should potentially enhance skeletal muscle development in both muscle cells and animals.

To rationalize the potential myogenesis-related phytogenics, a systematic screening platform for active phytogenics is necessary to provide rigorous scientific evidence for their efficacy and potency. Based on monitoring MSTN activity in L8 cells, we identified the potential phytogenic, G. uralensis extract (GUE), by bioactivity-guided fractionation and investigated the effect of GUE as a feed additive to increase carcass weight and lean meat in growth-finishing pigs. The major component of GUE was further identified for quality control of phytogenic feed additive. The results in this study suggest that the evaluation of MSTN ability in myoblasts can be use as the screening basis to identify potential myogenesis-related phytogenics as feed additives for economic animals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh whole plants of Andrographis paniculate, Centella asiatica, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Gynostemma pentaphyllum, Platycodon grandiflorus, Polygonum chinense, Portulaca oleracea, Saururus chinensis, Smilax china and Taraxacum campylodes were purchased from a reputable Chinese medicinal herb store in Taiwan (July 2020). Taq DNA polymerase was obtained from Kapa Biosystems (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). pMetLuc2 plasmid DNA and Ready-To-Glow™ Secreted Luciferase Reporter System were from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), T4 DNA ligase, and restriction enzymes (BglII and BamHI) were purchased from Promega (Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Methylthiazoletetrazolium (MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and Geneticin™ selective antibiotic (G418 sulfate) were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA). Ethanol was from J. T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). All other chemicals and solvents used in this study were of reagent or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade.

2.2. Plant extract preparation and cells transfection

Air-dried plants were grinded and extracted in 95% ethanol solution for 24 hr. The crude herbal extracts were used for

in vitro test or fractionated to different fractions later. L8 rat myoblast cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The 5’-flanking region (2.46-kb) upstream of the translation start site of MSTN gene (GenBank accession no. AY204900) was amplified from mouse genomic DNA[

24] by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a pair of specific primers containing

BglII and

BamHI sites (

Figure S1), respectively. The pMetLuc2-MSTN (

Figure S1) reporter plasmid was constructed by inserting this 2.46-kb MSTN promoter into pMetLuc2 plasmid. The pMetLuc2-MSTN L8 cells (L8 MSTN-Luc cells) used in this study were derived by stable transfection of pMetLuc2-MSTN and selected with G418.

2.3. MTT assay

For MTT assay, 2 x 10

4 cells of stable transfected L8 MSTN-Luc cells were seeded onto 96-well plates in DMEM containing 5% FBS. The experiment was performed when the cells reached 80% confluence. Various concentrations of herbal extracts were used to treat the cells for 24 hr at 37

oC, then the cell proliferation was determined by MTT colorimetric assay[

25]. Briefly, MTT reagent (2 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 hr at 37

oC. After adding dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to each well, the OD

595 of each well was measured by BioTek Powerwave XS microplate reader (New England, VT, USA).

2.4. Luciferase assays

For luciferase activity, 2 x 104 cells of stable L8 MSTN-Luc cells were seeded onto 96-well plates with DMEM containing 5% FBS. Secreted Metridia luciferase activity was measured using the Ready-To-Glow™ Secreted Luciferase Reporter Systems. After 24-hr treatment of various herbal extracts. The culture medium was removed to mix with luciferase substrate and VICTOR3 multilabel counter (PerkinElmer, Turku, Finland) was used to measure luciferase activity. The luciferase activity was normalized with cell proliferation prior to statistical analysis.

2.5. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from L8 cells using the Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, then reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using Revert Aid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and oligo(dT) as primer. The PCR was performed by Taq DNA polymerase using primers specific for MSTN (5'-CCAGGCACTGGTATTTGGCA-3' and 5'-AAGTCTCTCCGGGACCTCTT-3'). Amplification was performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 94oC for 5 min, 35 cycles at 94oC for 30 s, 55oC for 30 s, and 72oC for 30 s, and the cycling was ended with a final elongation step for 5 min at 72oC. The β-actin was used as the internal control. Amplicons after 2% agarose gel electrophoresis were visualized by a Doc Print System (Vilber Lourmat, Marne-la-Vallée, France) and the relative band intensities were quantified by ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. GUE preparation

The grinded G. uralensis (1 kg) was extracted by 95% ethanol solution for 24 hr prior to evaporation. After evaporation, the extract was applied to a process-scale liquid column chromatography system (Isolera Flash Puri, Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden). The separation was performed using a C18 column (KP-C18-HS column, Biotage) and the solvent gradient was 95% EtOH in H2O, and the extract was separated into 10 fractions under UV 245 nm (Figure 3).

2.7. Animal study

To investigate the beneficial effect of the GUE as a feed additive, the growth-finishing pigs were fed standard diet or the diet containing GUE in the experimental ranch at Tunghai University (Taichung, Taiwan). Twenty barrows and twenty gilts ([Landrace × Yorkshire] × Duroc) with initial average body weight (BW) of 12.24 ± 1.42 kg were randomly allocated to four treatment groups (control, low, medium and high concentrations with 10 pigs each group). All animals were monitored according to the previous standard procedure[

26] and were acclimatized with standard diet (Fwusow Industry Co. ltd., Taichung, Taiwan) and water

ad libitum for one week prior to the experiment. Mortality, body weight, feed and water intake were recorded weekly. At the end of experiment, hot carcass weights were recorded and used to calculate the carcass percentage. The length of each carcass spanning from the posterior edge of the symphysis pubis to the anterior edge of the first rib was measured, and the skin, bone, legs, shoulders, loins, bellies, tenderloins, backfat and neck fat were collected using the simplified EC-reference method[

27]. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in Tunghai University (Protocol no. 107-38).

2.8. Pyrosequencing and data analysis

The gut bacterial DNA extracted from pig feces in each treatment group at the end of experiment were used as templates for PCR amplification with 16S rRNA primers. The 16S rRNA amplicons for the illumine MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA). In order to prepare library, the primer pair sequences for the V3 and V4 region that create a single amplicon of approximately 460 bp. Amplify the V3 and V4 region and using a limited cycle PCR, add illumina sequencing adapters and dual-index barcodes to the amplicon target. Using the full complement of Nextera XT indices, up to 96 libraries can be pooled together for sequencing. Sequence on MiSeq - Using paired 300-bp reads, and MiSeq v3 reagents, the ends of each read are overlapped to generate high-quality, full-length reads of the V3 and V4 region in a single 65-hour run. The results of 16S rRNA gene amplicons sequencing will be analyzed by MiSeq Reporter (Illumina), BaseSpace (Illumina) and Greengenes database (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA) to do taxonomy and classification of microbiota GUE-treated or non-treated in different stages of pigs.

2.9. Statistics

The data are presented as mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) and examined for equal variance and normal distribution prior to statistical analysis using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A significance level of 0.05 was adopted. Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) test was used for group comparisons.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

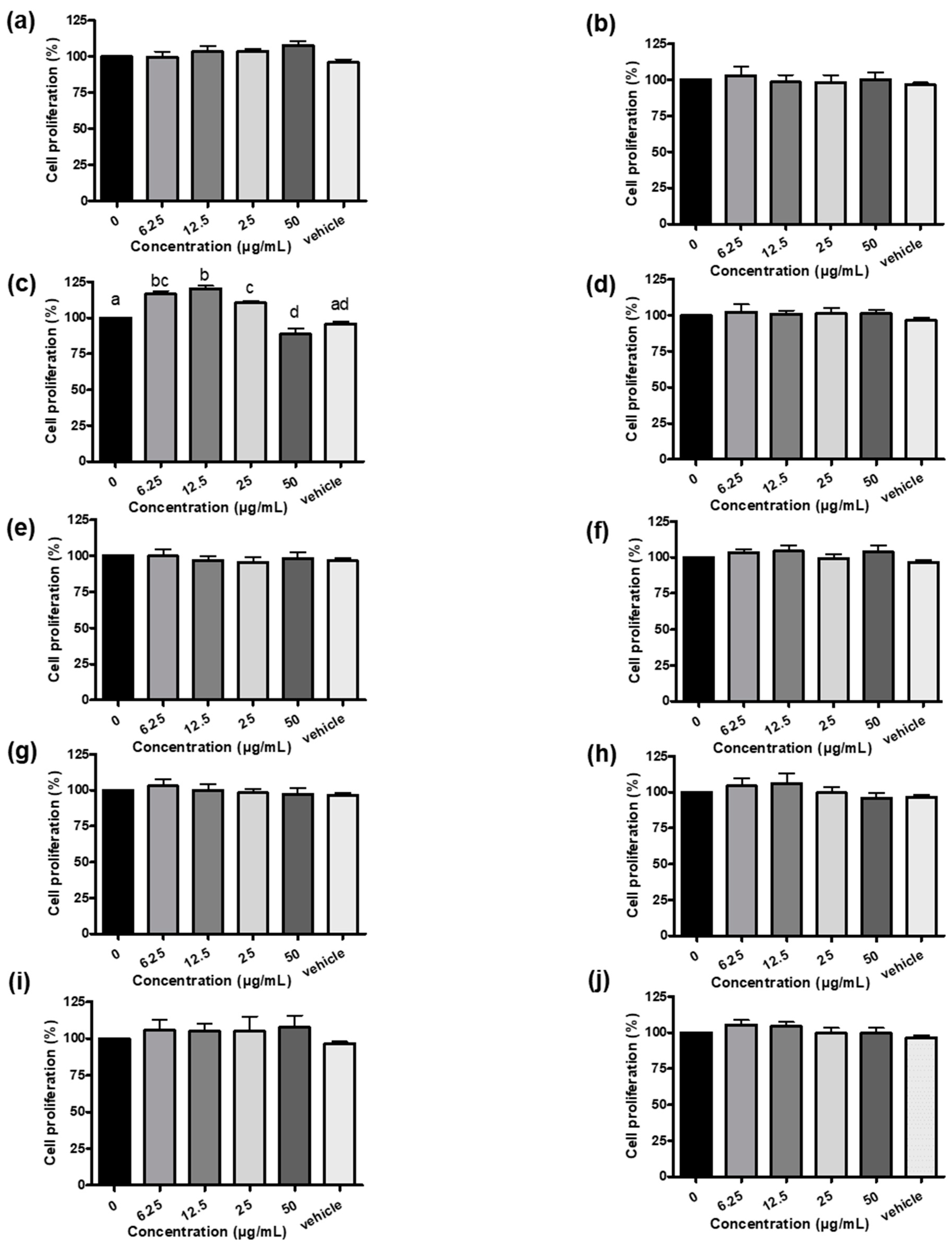

3.1. Establishment of systematic rodent myoblast screen platform and phytogenic screening

In this study, myostatin-luciferase (MSTN-Luc) reporter gene was transfected into L8 cells successfully and the stable clone (L8 MSTN-Luc cells) showed induced MSTN-Luc expression by dexamethasone at the effective concentrations reported previously[

28,

29] (

Figure S2). Thus, the MSTN-Luc activity in L8 MSTN-Luc cells can be used as a cell-based assay for MSTN expression in myoblast to detect the bioactivity of phytogenics, plant extracts, fractions or phytochemicals. The common herbal plants related to skeletal muscle diseases or regulation,

A.

paniculate,

C.

asiatica[

30],

G.

uralensis[

31],

G.

pentaphyllum[

32],

P.

grandiflorus[

33],

P.

chinense.[

34],

P.

oleracea[

35],

S.

chinensis[

36],

S.

china.[

37] and

T.

campylodes[

38], were selected to be screened in this study. Most herbal extracts did not increase L8 MSTN-Luc cell proliferation except for GUE (

Figure 1c). The low-concentration GUE was found to have large significant effects (

p < .05) on L8 MSTN-Luc cell proliferation, about 15% to 20% increase (

Figure 1c). The similar patterns were observed from the luciferase activity results of L8 MSTN-Luc cells treated with various herbal extracts (

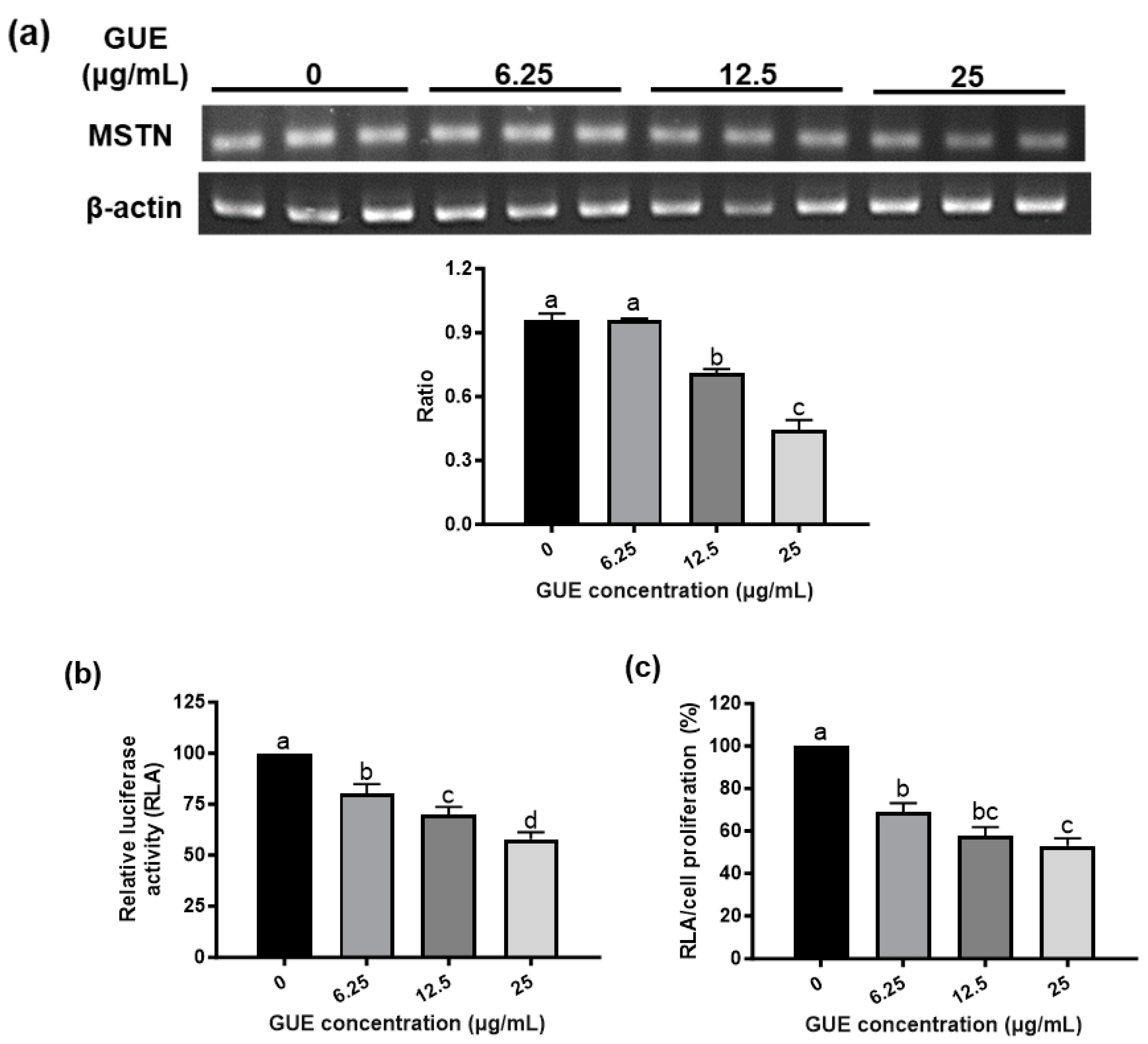

Figure S2). The MSTN mRNA level in L8 MSTN-Luc cells treated with GUE were analyzed by RT-PCR. The decreased mRNA level of MSTN in the GUE-treated groups was concentration-dependent. The higher concentration of GUE led to greater inhibition (

p < .05) of MSTN mRNA level in L8 MSTN-Luc cells (

Figure 2a). Therefore, GUE with increased cell proliferation and luciferase inhibition (

Figure 2b, 2c) was used for further

in vitro studies.

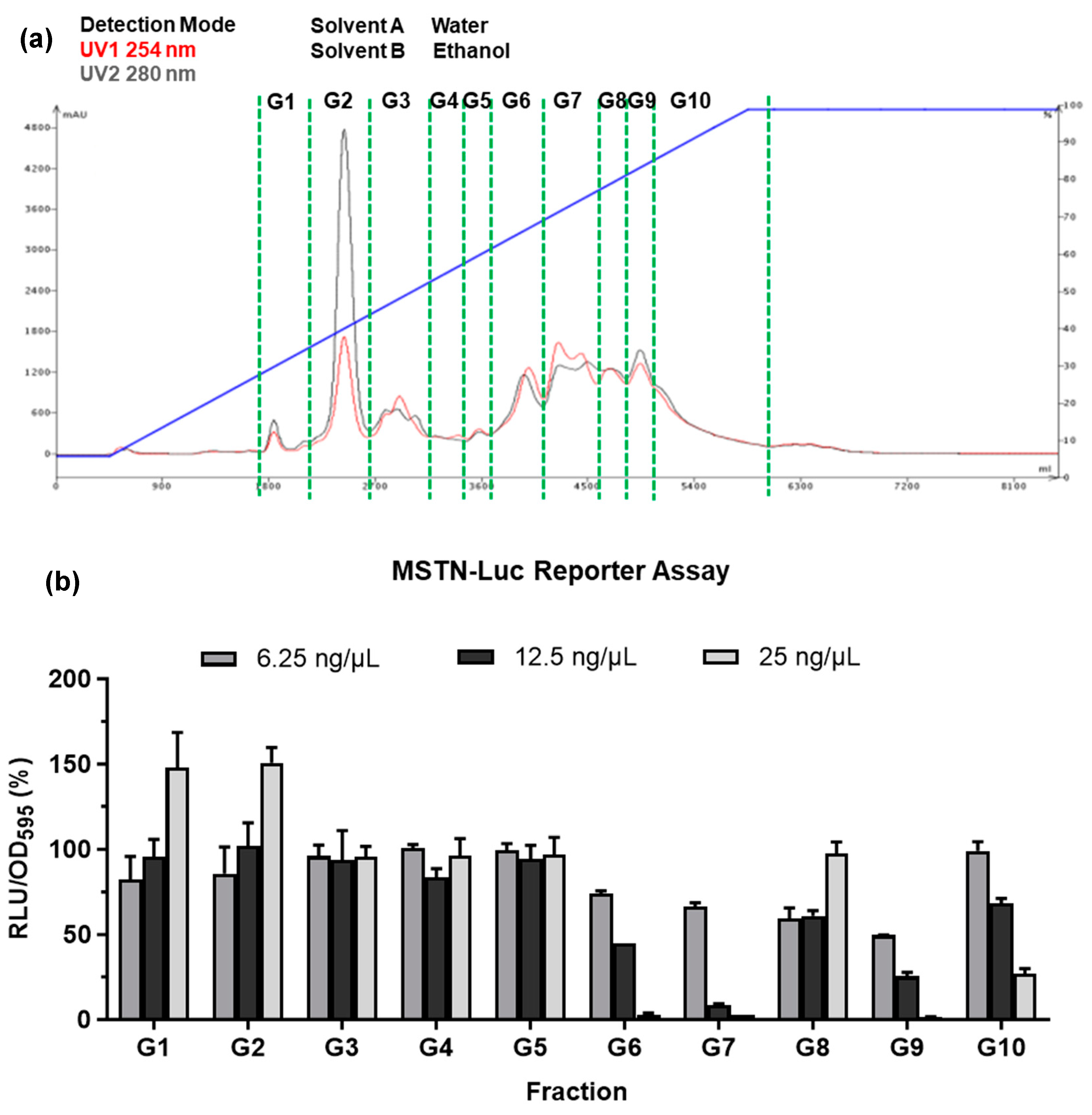

3.2. Characterization and identification of active fractions in GUE

The complex chemical composition of phytogenic makes it challenging to identify active compounds and mention batch-to-batch consistency. In this study, the process-scale liquid column chromatography was used to enrich biological activity of the GUE. The full-spectrum GUE was separated into ten fractions (G1 - G10) in a gradient elution mode (

Figure 3a), and the activity of each fraction was examined by MSTN-reporter assay in L8 MSTN-Luc cells (

Figure 3b). The G9 fraction was used for further purification and identification among the active fractions.

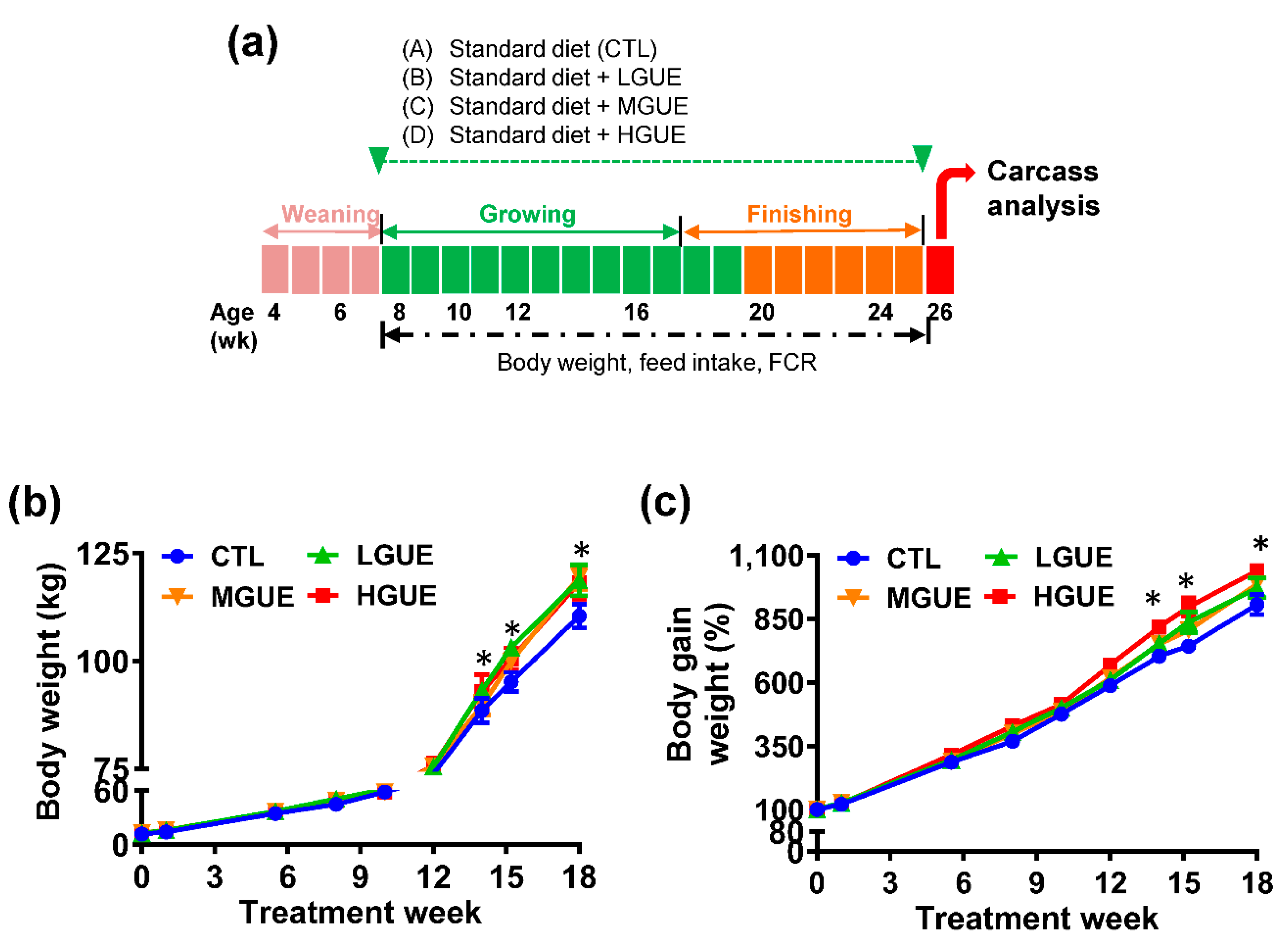

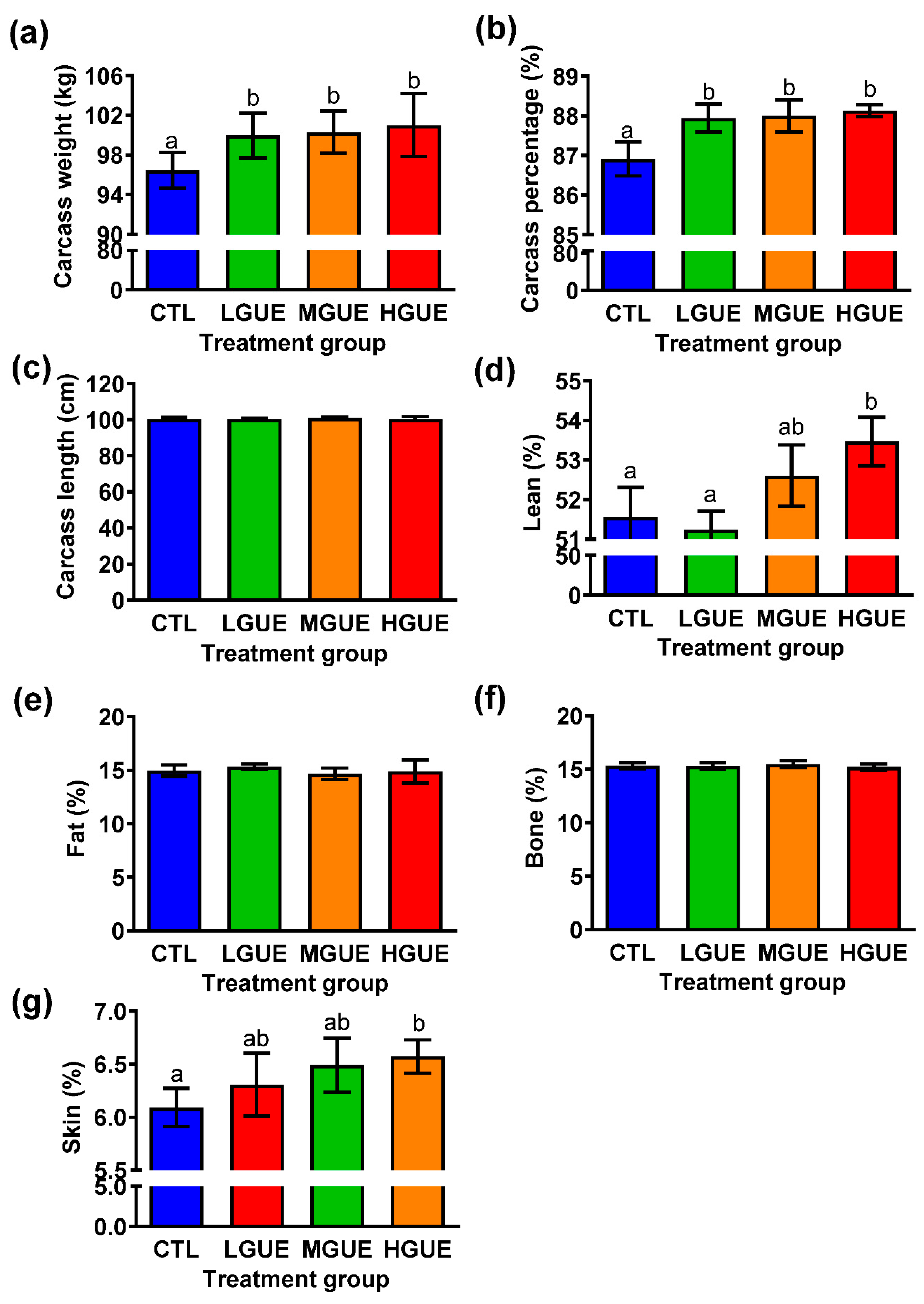

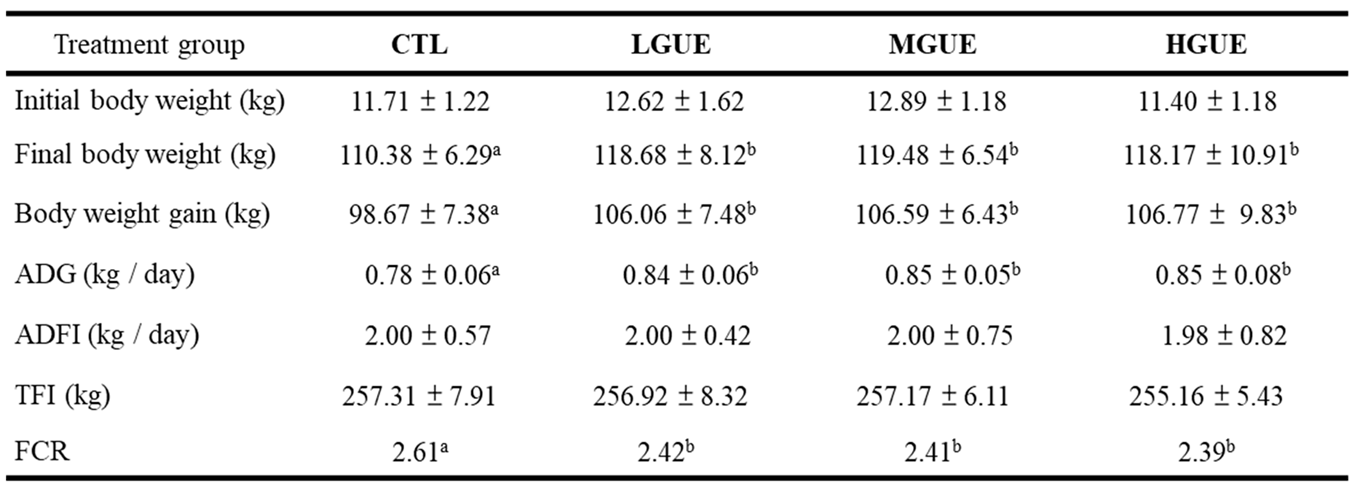

3.3. Effect of GUE as a feed additive on growth performance in growth-finishing pigs

The effect of GUE as feed additives in growth-finishing pigs was investigated (

Figure 4a). The final body weight (BW) showed a significant increase (

p < .05) in GUE-treated group. In addition, the BW gains in GUE-treat groups were significantly higher (

p < .05) than that in the control group (

Figure 4b, 4d). There was significant increase (

p < .05) in average daily gain (ADG) and decrease in feed conversion rate (FCR) in GUE-treated groups (

Table 1). The carcass weight and carcass percentage in GUE-treated groups were significantly higher (

p < .05) than that in the control group (

Figure 5a, 5b), while there was no significant difference (

p > .05) in carcass length among groups (

Figure 5c). The lean and skin percentages of carcass were significant higher (

p < .05) in GUE-treated groups than the control group (

Figure 4d and 4g), while there was no significant difference (

p > .05) in fat and bone percentages of carcass among groups (

Figure 4e, 4f).

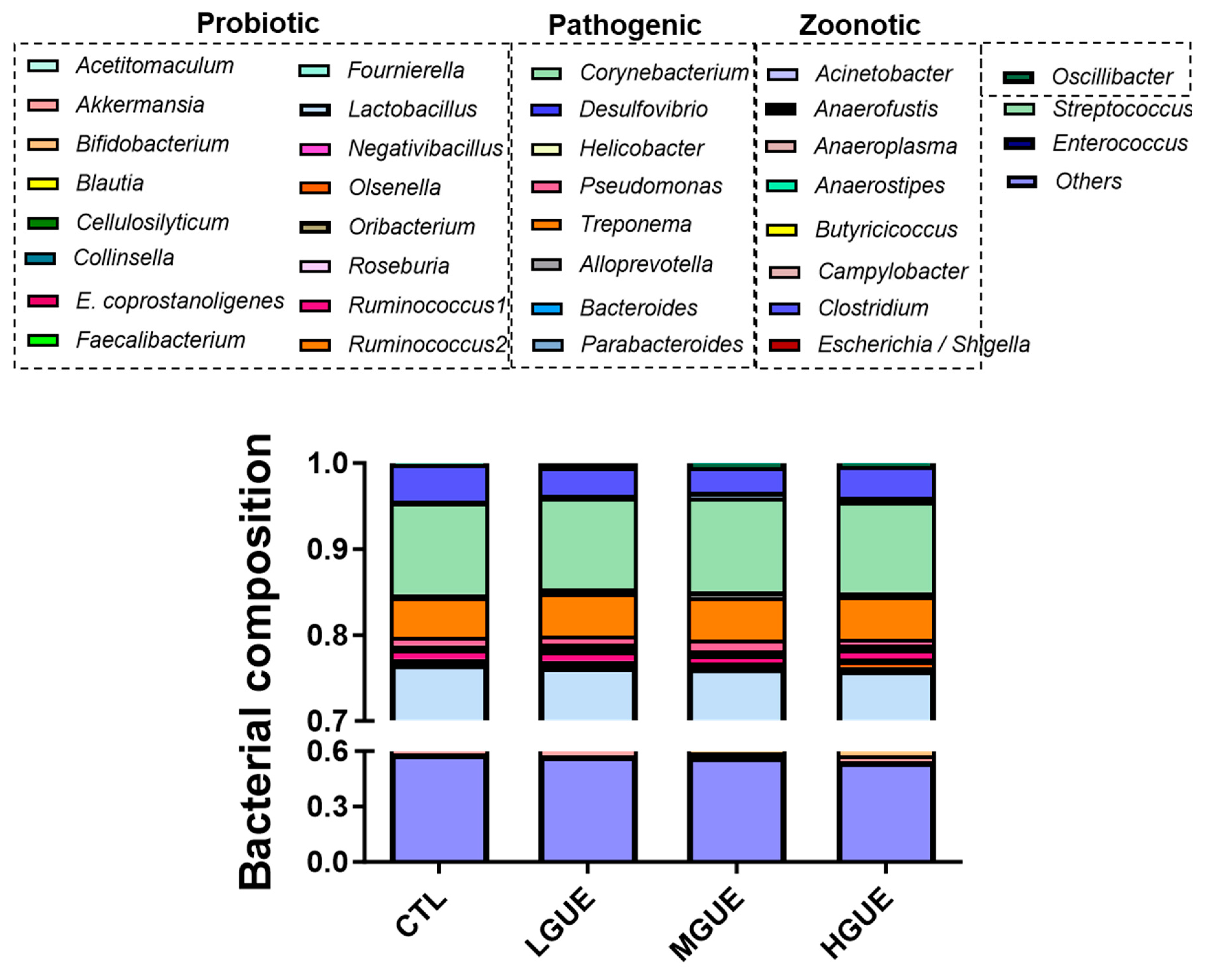

3.4. Effect of GUE as a feed additive on gut microbiota in growth-finishing pigs

Gut microbiota had been reported to correlate with growth performance in pigs[

39], therefore, the correlation between microbiota and growth performance in pigs fed with GUE was investigated. The results from bacterial composition in pig gut (

Figure 6) showed the pathogenic and zoonotic bacteria genera did not differ significantly (

p > .05) in the guts of pigs fed standard diet with or without GUE. Thus, GUE may not increase growth performance through gut microbiota regulation.

Four groups of weaned pigs were fed standard control diet (CTL), or standard diet containing low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) for 18 week. ADG: average daily gain, ADFI: average daily feed intake, TFI: total feed intake and FCR: feed conversion rate. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. Different letters (a-b) denote statistical significance (p < .05) among groups.

4. Discussion

The results from several studies indicated that the plant-based or phytogenic feed additives enhance animal health and growth performances[

13,

18]. These plant-based or phytogenic feed additives were proposed to exhibit antioxidant and antimicrobial properties[

16], and also support gut microbiota and functions to improve animal growth performance[

18,

40]. However, little is known about whether this action was modulated through myogenesis directly during animal growth. In this study, a systematic MSTN expression screening platform was established to screen myogenesis-related phytogenic using L8 cells. MSTN is a member of the TGF-β superfamily, and it is a secreted protein that functions as a negative regulator during skeletal muscle development[

19,

20]. MSTN is highly conserved among mammals including cattle, sheep, pigs, rabbits, and humans, and loss-of-function mutations would lead to the increased skeletal muscle mass [

21,

22,

23]. Hence, myostatin plays a pivotal role in regulating myogenesis. Inhibition of MSTN expression may have the potential to improve skeletal muscle growth in animals. Presently, a MSTN inhibitor, the monoclonal antibody known as bimagrumab binds to and restrains the MSTN activity to result in increased muscle mass and strength[

41,

42]. Clinical trials demonstrated that bimagrumab effectively enhanced muscle mass and function in humans suffering from muscle-wasting conditions, such as sarcopenia and inclusion body myositis[

43]. Additionally, MSTN inhibitors could generate potential side effects, including the increased risk of tumor development, thus further research is necessary to evaluate the safety issue[

44].

In livestock industry, there is a growing demand for feed additives that are safe, convenience, and efficiency to improve animal growth and performance. Therefore, the plant-based or phytogenic feed additive is a better strategy than the monoclonal antibody administration to improve animal growth. To rationalize the use of phytogenics, this established systematic MSTN expression screening platform was used to screen various herbal plant extracts which were not only related to skeletal muscle diseases or its regulation, but also were traditionally used as food ingredients and botanical medicine for humans and animals. The results in this study showed that GUE was the only tested plant extract that could increase cell proliferation (

Figure 1c) and inhibit MSTN expression in L8 cells (

Figure 2a). We also observed the luciferase activity decrease (

Figure 2b), and the ratio of luciferase activity to cell proliferation was used to evaluate effect of GUE on MSTN expression in L8 cells (

Figure 2c). Based on previous reports, MSTN inhibited myogenesis through inhibition of myoblast proliferation[

45,

46]. This study showed that GUE suppressed MSTN expression, and directly promoted L8 myoblast proliferation. These results suggested that GUE has the potential as a feed additive and contain active comportments to promote myogenesis. The process-scale liquid column chromatography was then used to enrich the biological activity of the GUE and identify possible activity components.

To investigate the potential of GUE as a feed additive. The growth-finishing pigs were fed diets containing different GUE concentration. The body weight and weight gain percentage were significantly increased in GUE-treated groups (

Figure 4b, 4c). As GUE showed myogenesis effect in growth-finishing pigs (

Figure 4), the increased body weight gain in pig fed GUE may partially be due to the increase of lean percentage (

Figure 5d). The concentration-dependent increase in lean percentage was observed in the GUE-treated groups, thus, higher concentration of GUE led to greater improvements in lean percentage. There was no significant different in ADFI and TFI with or without GUE treatment (

Table 1). There were significant differences in ADG and FCR between control and GUE treatment groups. By modulating MSTN expression in skeletal muscles, GUE may prompt animal growth by increasing body weight and lean content. Consequently, this observation suggests that GUE potentially serve as a favorable feed additive for boosting animal growth under current animal production system.

Akin to most clinical medicine, medical herbs, phytogenic and phytocompounds have been used in animals through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of cell development, metabolism of nutrients and bacterial composition of gut microbiota, etc. Other researches also reported that

Glycyrrhiza uralensis-related products as feed additives inhibit the relative amount of

Enterobacter,

Enterococcus,

Clostridium and

Bacteroides[

47,

48] and increased the relative abundance of

Lactobacillus[

49] at genus levels in weaned piglets. In this study, we analyzed gut microbiota to evaluate the relative amount of probiotic as well as pathogenic and zoonotic bacteria genera in growth-finishing pigs, indicated that GUE did not alter the bacterial composition gut microbiota in growth-finishing pigs (

Figure 6). Pigs at the growth-finishing stage display heightened maturity in contrast to their counterparts at the weaned stage. Consequently, the gut microbiota of growth-finishing pigs may exhibit greater stability than that of weaned piglets. Conversely, due to the brief 4 to 5-week span during the weaned piglet stage, the impact of feed additives on gut microbiota during this stage could be relatively effective. In our research, animals fed GUE as a feed additive for a longer period 18 weeks, should not be a strong influence of GUE on the gut microbiota of growth-finishing pigs. In this study, the observed GUE-enhanced growth performance may not be due to gut microbiota regulation.

These data suggest a novel application for

G. uralensis as a feed additive in growth performance enhancement through modulation of MSTN expression. In summary, the edible plant,

G. uralensis, is recognized as safe for ethnomedicinal or culinary use worldwide[

50,

51], and the findings from this study along with the published literature confirm the beneficial function of GUE on animal growth.

5. Conclusions

The results from the established systematic rodent myoblast screening platform demonstrated the effectiveness in identifying phytogenic compounds by evaluating myostatin promoter activity. Using this screening platform, the GUE was identified and found to significantly increase body weight, carcass weight, and lean content in pigs. In conclusion, this rodent myoblast screening platform successfully identified a myogenesis-promoting phytogenic, GUE, and subsequent experiment showed that the active fraction in GUE inhibited MSTN expression. These findings suggest a novel role for GUE in enhancing growth performance in economic animals by modulating MSTN expression. Furthermore, the established screening platform in this study exhibits the great potential for evaluating a wide variety of phytogenics related to myogenesis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Myostatin promoter-reporter plasmid.; Figure S2: The luciferase activity assay on dexamethasone and various herb extracts treated L8 MSTN-Luc cells.

Author Contributions

B.-R.O., J.-Y.Y. and Y.-C.L. conceptualized and supervised this project, and contributed to the manuscript. M.-H.H., L.-Y. H., C.-J. L, L.-L.K., Y.-T.T., Y.-C.C., W.-Y. L., T.-C.H. and Y.-C.W. assisted in the experiments, analyzed data, interpreted results with suggestions from C.-J.L. and Y.-C.C. All authors had read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 106-3114-B-005-001), and Academia Sinica (AS-KPQ-110-ITAR-09) in Taiwan.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript are included in this manuscript and Supplementary Information.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Animal Core Facility and Metabolomic Core Facility of Agricultural Biotechnology Research Center, Academia Sinica for the excellent technical assistance. We thank Ms Miranda Loney for editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

D All herbal materials used in this study were purchased from a local reputable Chinese medicinal herb store with no conflict of interest related to other manufacturers. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Giordani, L.; He, G.J.; Negroni, E.; Sakai, H.; Law, J.Y.C.; Siu, M.M.; Wan, R.; Corneau, A.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Cheung, T.H.; Le Grand, F. High-dimensional single-cell cartography reveals novel skeletal muscle-resident cell populations. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieland, M.; Trouwborst, I.; Clark, B.C. Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarneh, S.K.; Silva, S.L.; Gerrard, D.E. New insights in muscle biology that alter meat quality. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niranjan, D.; Sridhar, N.; Chandra, U.; Manjunatha, S.; Borthakur, A.; Vinuta, M.; Mohan, B. Recent perspectives of growth promoters in livestock: an overview. J. Livest. Sci. 2023, 14, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.T.; Crooks, S.R.; McEvoy, J.G.; McCaughey, W.J.; Hewitt, S.A.; Patterson, D.; Kilpatrick, D. Observations on the effects of long-term withdrawal on carcass composition and residue concentrations in clenbuterol-medicated cattle. Vet Res Commun 1993, 17, 459–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, W.M.; Paulissen, J.B.; Goodwin, M.C.; Alaniz, G.R.; Claflin, W.H. Recombinant bovine somatotropin improves growth performance in finishing beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Navarro, J.F. Food poisoning related to consumption of illicit β-agonist in liver. Lancet 1990, 336, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Thomas, A.; Schiwy-Bochat, K.-H.; Geyer, H.; Thevis, M.; Glenewinkel, F.; Rothschild, M.A.; Andresen-Streichert, H.; Juebner, M. Death after misuse of anabolic substances (clenbuterol, stanozolol and metandienone). Forensic Sci.Int. 2019, 303, 109925–109931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoupá, K.; Šťastný, K.; Sládek, Z. Anabolic steroids in fattening food-producing animals & mdash - a review. Animals 2022, 12, 2115–2130. [Google Scholar]

- Hirpessa, B.B.; Ulusoy, B.H.; Hecer, C. Hormones and hormonal anabolics: residues in animal source food, potential public health impacts, and methods of analysis. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Martel, J.; Ojcius, D.M.; Ko, Y.-F.; Young, J.D. Phytochemicals as prebiotics and biological stress inducers. Trends Biochem.Sci. 2020, 45, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; Tiwari, R.; Rana, R.; Khurana, S.K.; Sana, U.; Khan, R.U.; Alagawany, M.; Farag, M.R.; Dadar, M.; Joshi, S.K. Medicinal and therapeutic potential of herbs and plant metabolites / extracts countering viral pathogens - current knowledge and future prospects. Curr Drug Metab 2018, 19, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelli, N.; Solà-Oriol, D.; Pérez, J.F. Phytogenic feed additives in poultry: achievements, prospective and challenges. Animals 2021, 11, 3471–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhaya, S.D.; Kim, I.H. Efficacy of phytogenic feed additive on performance, production and health status of monogastric animals - a review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2017, 17, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windisch, W.; Schedle, K.; Plitzner, C.; Kroismayr, A. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry. Journal of Animal Science 2008, 86, E140–E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnisi, C.M.; Mlambo, V.; Gila, A.; Matabane, A.N.; Mthiyane, D.M.N.; Kumanda, C.; Manyeula, F.; Gajana, C.S. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of selected phytogenics for sustainable poultry production. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiouni, S.; Tellez-Isaias, G.; Latorre, J.D.; Graham, B.D.; Petrone-Garcia, V.M.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Yalçın, S.; El-Wahab, A.A.; Visscher, C.; May-Simera, H.L.; Huber, C.; Eisenreich, W.; Shehata, A.A. Anti-Inflammatory and antioxidative phytogenic substances against secret killers in poultry: current status and prospects. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H.; Grześkowiak, Ł.; Martinez-Vallespin, B.; Dietz, H.; Zentek, J. Porcine and chicken intestinal epithelial cell models for screening phytogenic feed additives & mdash; chances and limitations in use as alternatives to feeding trials. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 629–649. [Google Scholar]

- McPherron, A. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 20, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M.; Smith, T.P.; Bass, J.J. Mutations in myostatin (GDF8) in double-muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese cattle. Genome Res. 1997, 7, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisolia, A.; D'Angelo, G.; Porto Neto, L.; Siqueira, F.; Garcia, J.F. Myostatin (GDF8) single nucleotide polymorphisms in Nellore cattle. Genet. Mol. Res. 2009, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilger, A.C.; Gabriel, S.; Kutzler, L.; McKeith, F.; Killefer, J. The myostatin null mutation and clenbuterol administration elicit additive effects in mice. Animal 2010, 4, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salerno, M.S.; Thomas, M.; Forbes, D.; Watson, T.; Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M. Molecular analysis of fiber type-specific expression of murine myostatin promoter. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C1031–C1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.Y.; Cheng, L.C.; Ou, B.R.; Whanger, D.P.; Chang, L.W. Differential influences of various arsenic compounds on glutathione redox status and antioxidative enzymes in porcine endothelial cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1972–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.Y.; Chen, W.C.; Ou, B.R.; Yeh, J.Y.; Cheng, Y.H.; Tsng, P.H.; Hsu, M.H.; Tsai, M.S.; Liang, Y.C. Simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens by multiplex PCR coupled with DNA biochip hybridization. Lab Anim. 2018, 52, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscheid, W.; Dobrowolski, A.; Sack, E. Simplification of the EC reference method for the full dissection of pig carcasses. Fleischwirtschaft 1990, 70, 565–567. [Google Scholar]

- Salehian, B.; Mahabadi, V.; Bilas, J.; Taylor, W.E.; Ma, K. The effect of glutamine on prevention of glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with myostatin suppression. Metabolism 2006, 55, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Du, R.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Guan, H.; Hou, J.; An, X.-R. Dexamethasone-induced skeletal muscle atrophy was associated with upregulation of myostatin promoter activity. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 94, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, V.; SalinRaj, P.; Athira, R.; Soumya, R.S.; Raghu, K.G. Cerium nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous extract of Centella asiatica: characterization, determination of free radical scavenging activity and evaluation of efficacy against cardiomyoblast hypertrophy. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 21074–21083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Y.; Yamashita, Y.; Kishida, H.; Nakagawa, K.; Ashida, H. Licorice flavonoid oil enhances muscle mass in KK-Ay mice. Life Sci. 2018, 205, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, A.; Tang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, K. Chemical composition of three polysaccharides from Gynostemma pentaphyllum and their antioxidant activity in skeletal muscle of exercised mice. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2012, 22, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.J.; Bang, M.-H.; Kim, H.; Imm, J.-Y. Improvement of palmitate-induced insulin resistance in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells using Platycodon grandiflorum seed extracts. Food Biosci. 2018, 25, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Lv, X.; Cui, L.; Yao, W.; Liu, Y. Preventive effects of Polygonum multiflorum on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 2445–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, O.; Okwuasaba, F.; Ejike, C. Skeletal muscle relaxant action of an aqueous extract of Portulaca oleracea in the rat. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1987, 19, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.-H.; Song, M.-C.; Bae, K.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.H.; Sung, S.H.; Ye, S.K.; Lee, K.H.; Yun, Y.-P.; Kim, T.-J. Sauchinone attenuates oxidative stress-induced skeletal muscle myoblast damage through the down-regulation of ceramide. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, C.A.B.; González-Cortazar, M.; Herrera-Ruiz, M.; Román-Ramos, R.; Aguilar-Santamaría, L.; Tortoriello, J.; Jiménez-Ferrer, E. Hypoglycemic and hypotensive activity of a root extract of smilax aristolochiifolia, standardized on N-trans-Feruloyl-Tyramine. Molecules 2014, 19, 11366–11384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.; Gao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, X.-X.; Pan, S.-N. Effects of dandelion extract on the proliferation of rat skeletal muscle cells and the inhibition of a lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory reaction. Chin. Med. J. 2018, 131, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, N.; Park, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Jeong, J.Y. Protective effects of biological feed additives on gut microbiota and the health of pigs exposed to deoxynivalenol: a review. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022, 64, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, A.A.; Yalçın, S.; Latorre, J.D.; Basiouni, S.; Attia, Y.A.; Abd El-Wahab, A.; Visscher, C.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Huber, C.; Hafez, H.M.; Eisenreich, W.; Tellez-Isaias, G. Probiotics, prebiotics, and phytogenic substances for optimizing gut health in poultry. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 395–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Lee, Y.-S. Myostatin inhibitors: panacea or predicament for musculoskeletal disorders? J. Bone. Metab. 2020, 27, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molfino, A.; Amabile, M.I.; Rossi Fanelli, F.; Muscaritoli, M. Novel therapeutic options for cachexia and sarcopenia. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2016, 16, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-J. Targeting the myostatin signaling pathway to treat muscle loss and metabolic dysfunction. J. Clin. Invest. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, D.H. Next Generation Antiobesity Medications: Setmelanotide, Semaglutide, Tirzepatide and Bimagrumab: What do They Mean for Clinical Practice? J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 30, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joulia, D.; Bernardi, H.; Garandel, V.; Rabenoelina, F.; Vernus, B.; Cabello, G. Mechanisms involved in the inhibition of myoblast proliferation and differentiation by myostatin. Exp. Cell Res. 2003, 286, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Langley, B.; Berry, C.; Sharma, M.; Kirk, S.; Bass, J.; Kambadur, R. Myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle growth, functions by inhibiting myoblast proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40235–40243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shou, J.-W.; Li, X.-Y.; Zhao, Z.-X.; Fu, J.; He, C.-Y.; Feng, R.; Ma, C.; Wen, B.-Y.; Guo, F. Berberine-induced bioactive metabolites of the gut microbiota improve energy metabolism. Metabolism 2017, 70, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhang, J. Prevention and treatment of chronic heart failure through traditional Chinese medicine: role of the gut microbiota. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104552–104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Zhao, P.; Shao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Bai, D.; Liao, C.; He, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, X. Effects of dietary Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide supplementation on growth performance, intestinal antioxidants, immunity and microbiota in weaned piglets. Anim. Biotechnol. 2022, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Zuo, G.; Lee, S.K.; Lim, S.S. Acute and subchronic toxicity study of nonpolar extract of licorice roots in mice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2242–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Shan, L.; Fan, G.; Gao, X. Liquorice, a unique “guide drug” of traditional Chinese medicine: a review of its role in drug interactions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Effect of various herb extracts (a-j) on L8 MSTN-Luc cells proliferation. L8 MSTN-Luc cells were treated with various herbal extracts, Andrographis paniculate (a), Centella asiatica (b) , Glycyrrhiza uralensis (c), Gynostemma pentaphyllum (d), Platycodon grandifloras (e), Polygonum chinense (f), Portulaca oleracea (g), Saururus chinensis (h), Smilax china (i) and Taraxacum campylodes (j), in different concentrations or with 1% ethanol as vehicle control. L8 MSTN-Luc cell proliferation was measured using MTT assay. Different letters (a-d) denote significant differences (p < .05) among treatments. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Figure 1.

Effect of various herb extracts (a-j) on L8 MSTN-Luc cells proliferation. L8 MSTN-Luc cells were treated with various herbal extracts, Andrographis paniculate (a), Centella asiatica (b) , Glycyrrhiza uralensis (c), Gynostemma pentaphyllum (d), Platycodon grandifloras (e), Polygonum chinense (f), Portulaca oleracea (g), Saururus chinensis (h), Smilax china (i) and Taraxacum campylodes (j), in different concentrations or with 1% ethanol as vehicle control. L8 MSTN-Luc cell proliferation was measured using MTT assay. Different letters (a-d) denote significant differences (p < .05) among treatments. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of G. uralensis extract (GUE) on MSTN mRNA level and MSTN promoter activity in L8 MSTN-Luc cells. The effect of GUE on MSTN mRNA level were determined by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The relative ratio of MSTN mRNA level to internal control was calculated (a). The effect of GUE on cell proliferation was investigated by MTT assay (

Figure 1c). MSTN promoter activity was measured by luciferase activity assay (b). The ratio of luciferase activity to cell proliferation (c) was used to evaluate GUE inhibitory effect. Different letters (a-d) denote significant differences (p < .05) among treatments. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of G. uralensis extract (GUE) on MSTN mRNA level and MSTN promoter activity in L8 MSTN-Luc cells. The effect of GUE on MSTN mRNA level were determined by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The relative ratio of MSTN mRNA level to internal control was calculated (a). The effect of GUE on cell proliferation was investigated by MTT assay (

Figure 1c). MSTN promoter activity was measured by luciferase activity assay (b). The ratio of luciferase activity to cell proliferation (c) was used to evaluate GUE inhibitory effect. Different letters (a-d) denote significant differences (p < .05) among treatments. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Systematic analysis of major active fractions of G. uralensis extract. The ethanolic extract of G. uralensis was purified by Process-Scale Liquid Column Chromatography and separated into ten fractions (a). The bioactive fraction was identified by MSTN gene reporter assay in L8 MSTN-Luc cells treated with various GUE concentrations (b). The results are indicated as the ratio of luciferase activity to cell proliferation.

Figure 3.

Systematic analysis of major active fractions of G. uralensis extract. The ethanolic extract of G. uralensis was purified by Process-Scale Liquid Column Chromatography and separated into ten fractions (a). The bioactive fraction was identified by MSTN gene reporter assay in L8 MSTN-Luc cells treated with various GUE concentrations (b). The results are indicated as the ratio of luciferase activity to cell proliferation.

Figure 4.

Effect of GUE as a feed additive on body weight in growth-finishing pigs. Flow chart show the timeline for evaluating of GUE effect as a feed additive on growth-finishing pigs (a). After weaning, pigs were randomized into four groups. Standard control diet (CTL), low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) treatment of 10 animals each group. GUE as feed additive was fed for 18 weeks. Body weight (b) and body gain weight (c) in each treatment group was monitored before and after 18-week treatment. Asterisks indicate the significant difference (p < .05) in body gain weight between HGUE and CTL groups in the same treatment week. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM.

Figure 4.

Effect of GUE as a feed additive on body weight in growth-finishing pigs. Flow chart show the timeline for evaluating of GUE effect as a feed additive on growth-finishing pigs (a). After weaning, pigs were randomized into four groups. Standard control diet (CTL), low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) treatment of 10 animals each group. GUE as feed additive was fed for 18 weeks. Body weight (b) and body gain weight (c) in each treatment group was monitored before and after 18-week treatment. Asterisks indicate the significant difference (p < .05) in body gain weight between HGUE and CTL groups in the same treatment week. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM.

Figure 5.

The effect of GUE as a feed additive on carcass characteristics of pigs. Four groups of weaned pigs were fed standard control diet (CTL), or standard diet containing low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) for 18 weeks. Carcass weight (a), carcass percentage (b), carcass length (c), as well as the percentage of lean (d), fat (e), bone (f) and skin (g) of six representative pigs from each groups, were measured and calculated at the end of 18 weeks. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. Different letters denote statistical significance (p < .05) among groups.

Figure 5.

The effect of GUE as a feed additive on carcass characteristics of pigs. Four groups of weaned pigs were fed standard control diet (CTL), or standard diet containing low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) for 18 weeks. Carcass weight (a), carcass percentage (b), carcass length (c), as well as the percentage of lean (d), fat (e), bone (f) and skin (g) of six representative pigs from each groups, were measured and calculated at the end of 18 weeks. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. Different letters denote statistical significance (p < .05) among groups.

Figure 6.

The effect of GUE as a feed additive on gut microbiota in pigs. The bacterial composition at the genus level in the guts of pigs fed control diet (CTL), or diet containing low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) for 18 weeks was shown from three representative pigs in each groups were pyrosequenced and the data were analyzed at the end of 18 weeks.

Figure 6.

The effect of GUE as a feed additive on gut microbiota in pigs. The bacterial composition at the genus level in the guts of pigs fed control diet (CTL), or diet containing low GUE concentration (LGUE), medium GUE concentration (MGUE) and high GUE concentration (HGUE) for 18 weeks was shown from three representative pigs in each groups were pyrosequenced and the data were analyzed at the end of 18 weeks.

Table 1.

Effect of GUE as a feed additive on the parameter of growth performance in pigs.

Table 1.

Effect of GUE as a feed additive on the parameter of growth performance in pigs.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).