Submitted:

27 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

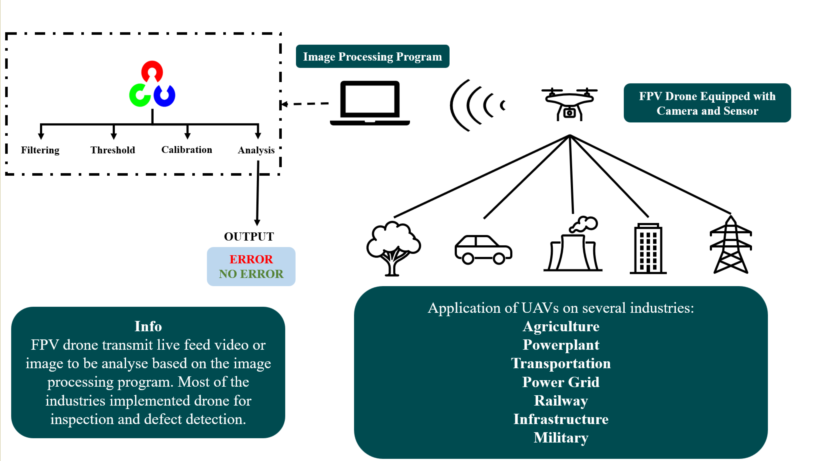

1.1. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

2. Implementation of UAV

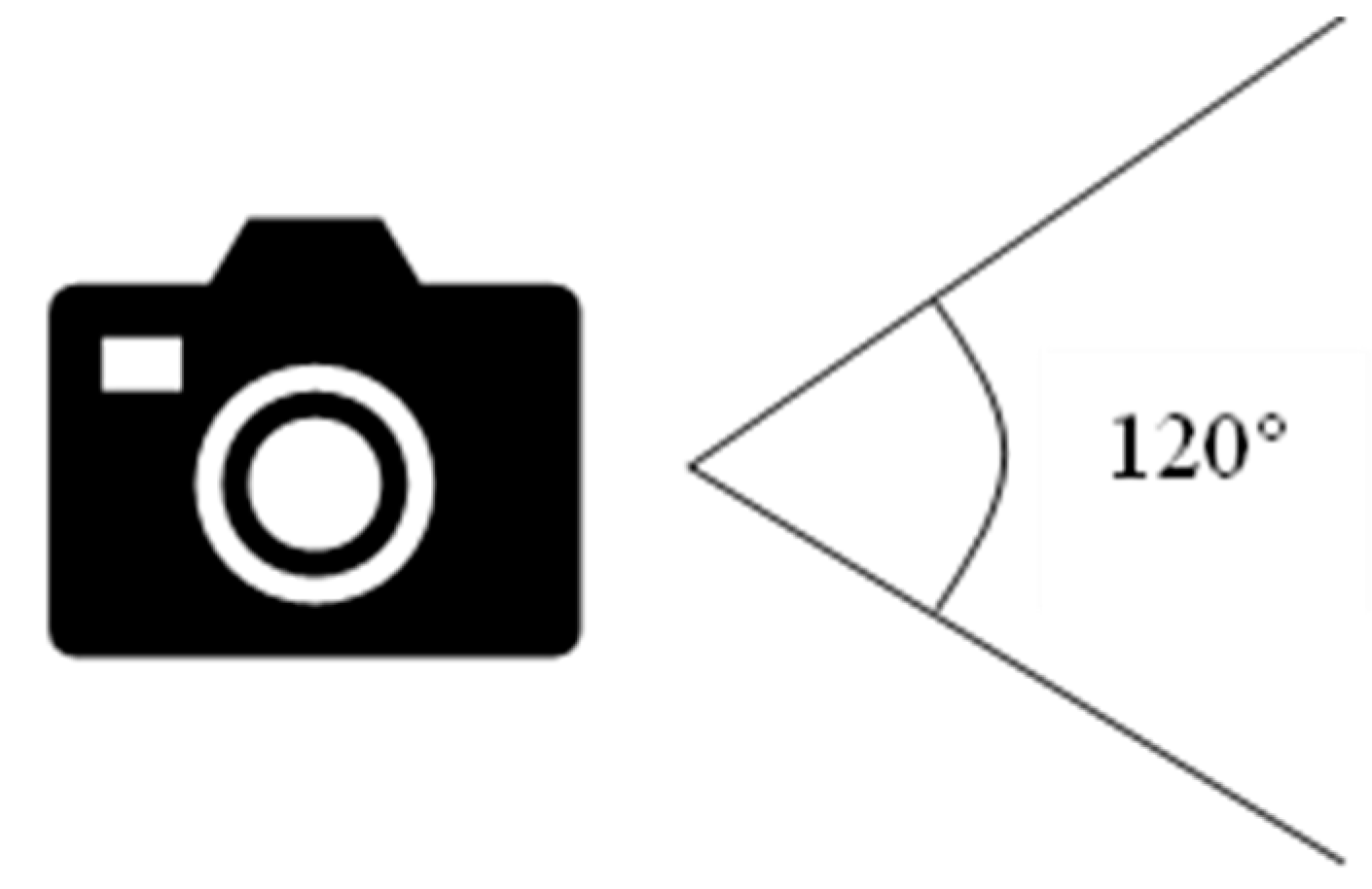

3. FPV Camera

- (a)

- Advantages of CCD Imaging Sensor

- (b)

- Advantages of CMOS Imaging Sensor

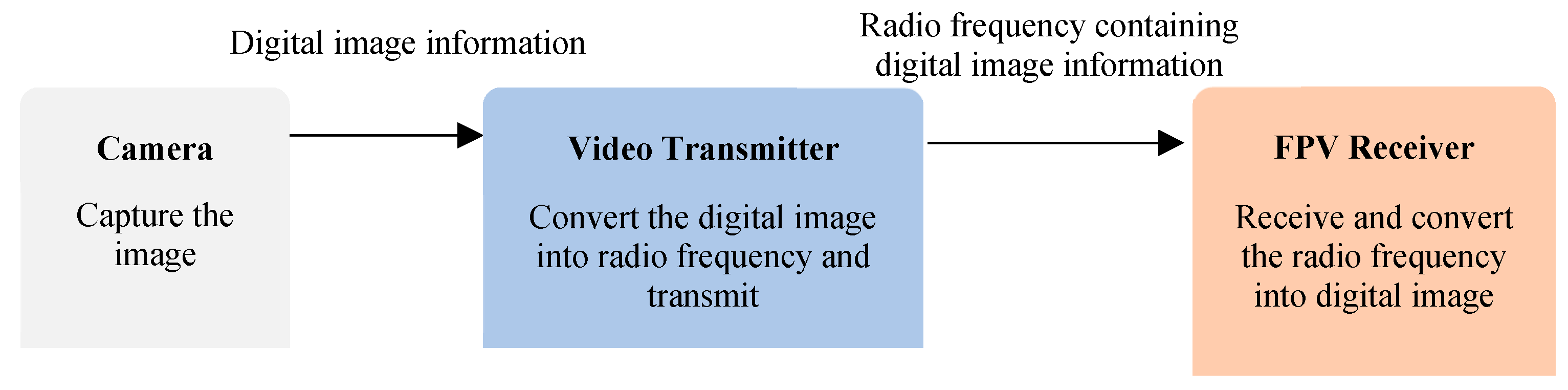

3.1. Video Transmitter

3.2. FPV Receiver

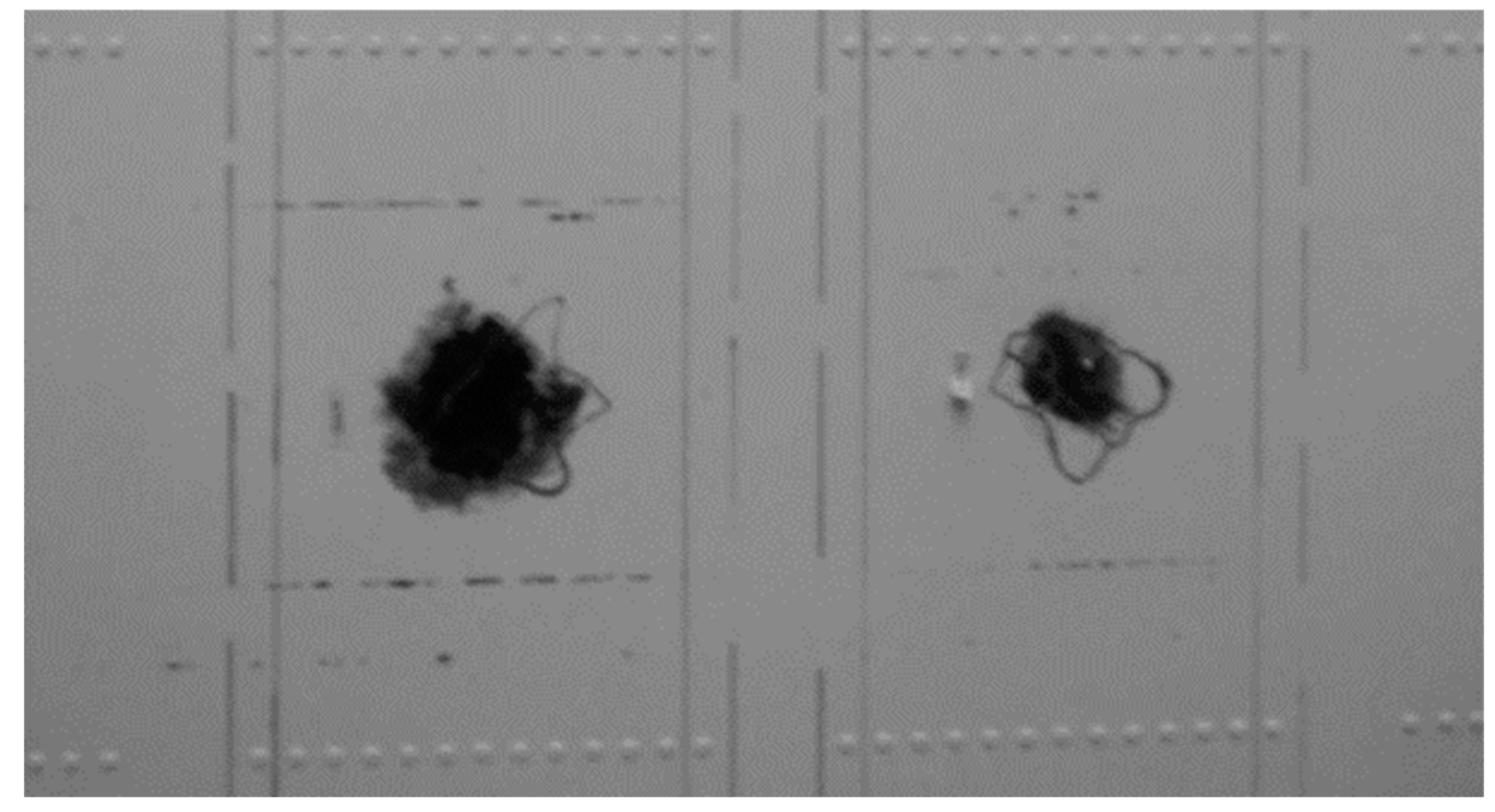

4. Image Filtering

| Library | Function |

| cv2 | Display the visual from the camera. Read the image input from the camera. Transform the image into grayscale, blur, and threshold. |

| NumPy | Arithmetic operations Handling a complex number |

| Scipy, spatial | Draw an object on the image Measure the size of an object |

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S.; Johnson, C.; Green, B. Image Segmentation Methods for Computer Vision. J. Image Anal. 2019, 18, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Brown, R. Image Registration Techniques for Medical Imaging. Med. Imaging Tech. 2020, 8, 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, L.; Woods, R. Object Recognition in Computer Vision. J. Object Anal. 2018, 5, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Oščádal, P.; Spurný, T.; Kot, T.; Grushko, S.; Suder, J.; Heczko, D.; Novák, P.; Bobovský, Z. Distributed Camera Subsystem for Obstacle Detection. Sensors 2022, 22, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, M.; Kurylo, J. Usability of Perception Sensors to Determine the Obstacles of Unmanned Ground Vehicles Operating in Off-Road Environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jánoš Rudolf; Srikanth Murali. Design of ball collecting robot. Technical Sciences and Technologies 2021, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, K.; & Nowakowski, M. (2021). The use of unmanned vehicles for military logistic purposes. Economics and Organization of Logistics 5, 43–57. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Williams, J.; Jones, D. Machine Learning in Image Processing. Machine Learn. Image Tech. 2019, 22, 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G. Image Classification Using Deep Learning. Deep Learn. Image Process. 2012, 45, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Object Detection with Convolutional Neural Networks. Convolutional Neural Netw. 2018, 35, 421–430. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M. Generative Adversarial Networks for Image Generation. GANs Image Gen. 2014, 28, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R. Medical Image Analysis in Disease Diagnosis. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 17, 230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, M.; Pentland, A. Facial Recognition Technology for Security Applications. Facial Recog. Security 1991, 32, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, G. Satellite Image Processing in Environmental Monitoring. Remote Sensing Environ. 2019, 45, 540–548. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Kim, J. UAVs for agricultural monitoring and precision farming. Int. J. Remote Sens. Agric. 2019, 36, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Williams, R.; Brown, M. Challenges of UAV battery technology for enhanced flight endurance. J. Unmanned Aerial Syst. 2018, 42, 750–764. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, L.; Johnson, C.; Green, B. UAVs in disaster response and humanitarian aid. Disaster Manag. UAVs 2021, 25, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, G.S. et al. (2022). Sensor Architecture Model for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Dedicated to Electrical Tower Inspections. In: Pereira, A.I.; Košir, A.; Fernandes, F.P.; Pacheco, M.F.; Teixeira, J.P.; Lopes, R.P. (eds) Optimization, Learning Algorithms and Applications. OL2A 2022. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1754. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gajjar P.; Virensinh D.; Siddharth M.; Pooja S.; Vijay U.; Madhu S.. Path Planning and Static Obstacle Avoidance for Unmanned Aerial Systems. In International Conference on Advancements in Smart Computing and Information Security, Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022, pp. 262–270.

- Jones, C.; White, S. Impact of drone delivery services on logistics and last-mile delivery. J. UAV Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 38, 230–242. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Smith, J.; Williams, M. Integration of UAVs with artificial intelligence for autonomous navigation. J. Intell. Robot. Autom. 2020, 48, 801–813. [Google Scholar]

- Šančić, T.; Brčić, M.; Kotarski, D.; Łukaszewicz, A. Experimental Characterization of Composite-Printed Materials for the Production of Multirotor UAV Airframe Parts. Materials 2023, 16, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba G.; Crupi V.; Epasto G.;Additively manufactured lightweight monitoring drones: Design and experimental investigation,Polymer,Volume 241,2022,ISSN 0032-3861. [CrossRef]

- Lukaszewicz A.; Szafran K.; Jozwik J. CAx techniques used in UAV design process, 7th IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, MetroAeroSpace 2020, art. no. 9160091, pp. 95 – 98,5. [CrossRef]

- Grodzki, W.; Łukaszewicz, A. Design and manufacture of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) wing structure using composite materials. Mater. Werkst. 2015, 46, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Adnan & Bani Younes, Ahmad & Islam, Shafiqul & Dias, Jorge & Seneviratne, Lakmal & Cai, Guowei. (2015). A Review on the Platform Design, Dynamic Modeling and Control of Hybrid UAVs. 2015 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems, ICUAS 2015. [CrossRef]

- Szafran K.; Łukaszewicz A. Flight safety - some aspects of the impact of the human factor in the process of landing on the basis of a subjective analysis, 7th IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, MetroAeroSpace 2020, art. no. 9160209, pp. 99–102. [CrossRef]

- Chodnicki, M.; Pietruszewski, P.; Wesołowski, M.; Stępień, S. Finite-time SDRE control of F16 aircraft dynamics. Archives of Control Sciences 2022, 32, 557–576. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabi, M.S.; Beigi, P.; Aghakhani, S. Drone Delivery Systems and Energy Management: A Review and Future Trends. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2206.10765. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; Song, Y. UAV Automation Control System Based on an Intelligent Sensor Network. Journal of Sensors 2022, 2022, 7143194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gupta, P. UAVs in film-making and aerial cinematography. J. Aerial Cinematogr. Media Prod. 2021, 25, 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Johnson, C. Legal and ethical considerations of UAV operations. J. UAV Policy Ethics 2019, 35, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Johnson, R.; Green, P. Emerging trends and future prospects of UAV technology. UAV Technol. Innovations 2022, 85, 146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, N.K.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Shahar, F.S.; Holovatyy, A.; Giernacki, W. Review on Type of Sensors and Detection Method of Anti-Collision System of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Sensors 2023, 23, 6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Garcia, A.; White, B. UAV swarm intelligence and its applications. Swarm Rob. UAVs 2018, 15, 321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Garcia, M.; Williams, R. Integration of UAVs with artificial intelligence for obstacle detection. Int. J. Unmanned Syst. Eng. 2020, 39, 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. An Efficient Predictive Maintenance Approach for Aerospace Industry. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 6th International Conference on Logistics, Informatics, and Service Science (LISS), 2018; pp 257-262.

- Wang, W.; Wang, Q. Big Data-Driven Optimization of Aerospace MRO Inventory Management. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM); 2020; pp. 2336–2340. [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez, A.; Husain, M.A.; Singh, S.P.; Chauhan, A.; Khan, M.T.; Kumar, N.; Chauhan, A.; Soni, S.K. Implementation of drone technology for farm monitoring & pesticide spraying: A review. Information Processing in Agriculture 2023, 10, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, C.R.; Vijayakumar, P.; Kiruba, P.; Kanna, S.A.; Hariprasath, E.R.; Priya, C.A. First Person View Camera Based Quadcopter with Raspberry Pi. International Journal of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering 2018, 12, 909–913. [Google Scholar]

- Holovatyy, A.; Teslyuk, V.; Kryvinska, N.; Kazarian, A. Development of Microcontroller-Based System for Background Radiation Monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 1–14 Special issue: Electronics for Sensors, 7322; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holovatyy, A.; Teslyuk, V.; Lobur, M.; Sokolovskyy, Y.; Pobereyko, S. Development of Background Radiation Monitoring System Based on Arduino Platform. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 13th International Scientific and Technical Conference on Computer Science and Information Technologies (CSIT); 2018; pp. 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holovatyy, A.; Teslyuk, V.; Lobur, M.; Pobereyko, S.; Sokolovskyy, Y. Development of Arduino-based Embedded System for Detection of Toxic Gases in Air. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 13th International Scientific and Technical Conference on Computer Science and Information Technologies (CSIT), 2018;. – pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efaz, E.T.; Mowlee, M.M.; Jabin, J.; Khan, I.; Islam, M.R. Modeling of a high-speed and cost-effective FPV quadcopter for surveillance. ICCIT 2020 - 23rd International Conference on Computer and Information Technology, Proceedings, 2020, 19– 21. [CrossRef]

- Dorafshan, S.; Thomas, R.J.; Maguire, M. Fatigue Crack Detection Using Unmanned Aerial Systems in Fracture Critical Inspection of Steel Bridges. Journal of Bridge Engineering 2018, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Sun, X.; Su, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, C.; Guo, Q. UAV-Lidar aids automatic intelligent powerline inspection. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2021, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, E.; Zhang, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, H.I.; Jobaer, S. Autonomous vision-based primary distribution systems porcelain insulators inspection using UAVs. Sensors (Switzerland) 2021, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Luthra, A.; Pahwa, E.; Tiwari, K.; Rathore, H.; Pandey, H.M.; Corcoran, P. DroneAttention: Sparse weighted temporal attention for drone-camera based activity recognition. Neural Networks, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Shin, S.Y.; Ko, B.C.; Chang, C. Early sinkhole detection using a drone-based thermal camera and image processing. Infrared Physics and Technology 2016, 78, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Li, G.; Cai, R.; Ma, J.; Wang, M. Mapping and modelling defect data from UAV captured images to BIM for building external wall inspection. Automation in Construction 2022, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Seo, J.; Wacker, P.E.J. UAV-aided bridge inspection protocol through machine learning with improved visibility images. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Meng, F.; Qin, Y.; Qian, Y.; Xu, F.; Jia, L. UAV imagery based potential safety hazard evaluation for high-speed railroad using Real-time instance segmentation. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, S.; de Oliveira, W.J.; de Souza Filho, C.R. UAV-based remote sensing for the petroleum industry and environmental monitoring: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2022, 208, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasingam, N.; Ashan Salgadoe, A.S.; Powell, K.; Gonzalez, L.F.; Natarajan, S. A review of UAV platforms, sensors, and applications for monitoring of sugarcane crops. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2022, 26, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanová, P.; Jurda, M.; Vojtíšek, T.; Krajsa, J. Using drone-mounted cameras for on-site body documentation: 3D mapping and active survey. Forensic Science International 2017, 281, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekidis, A.; Anastasiadis, A.G.; Vokas, G.A. A. Electricity infrastructure inspection using AI and Edge Platform-based UAVs. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 1394–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Xu, Y.; Gong, X.; Gao, S.; Sang, X.; Zhu, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. An obstacle detection and distance measurement method for sloped roads based on Vidar. Journal of Robotics 2022, 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J.; Panopoulos, N. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) manipulation assisted by Augmented Reality (AR): The case of a drone. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, A.; Wahyono, R.H.; Irawan, D. The Development of a Drone’s First Person View (FPV) Camera and Video Transmitter using 2.4GHz WiFi and 5.8GHz Video Transmitter. In 2018 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT); IEEE, 2018; pp 1-6.

- Hwang, I.; Kang, J. A Low Latency First-Person View (FPV) Streaming System for Racing Drones. Sensors 2020, 20, 785. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, F.; Melodia, T.; Baiocchi, A. Wi-Fi FPV: Experimental Evaluation of UAV Video Streaming Performance. In 2019 IEEE 15th International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS); IEEE, 2019; pp 1-8.

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, M. A Novel FPV Image Transmission System for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Journal of Imaging 2021, 7, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Holovatyy, A.; Teslyuk, V. Verilog-AMS model of mechanical component of integrated angular velocity microsensor for schematic design level. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computational Problems of Electrical Engineering (CPEE); 2015; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, C.R.; Vijayakumar, P.; Kiruba, P.; Kanna, S.A.; Hariprasath, E.R.; Priya, C.A. First Person View Camera Based Quadcopter. 12, 909–913.

- Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y. A Novel Low-Latency Video Streaming Framework for FPV Drone Racing. Sensors 2022, 22, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Ajay, A.V.; Yadav, A.R.; Mehta, D.; Belani, J.; Raj Chauhan, R. A guide to novice for proper selection of the components of drone for specific applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 65, 3617–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerram, P.; Stefanov, K. CMOS and CCD image sensors for space applications. In High-Performance Silicon Imaging: Fundamentals and Applications of CMOS and CCD Sensors; Elsevier, 2019; pp 255–287. [CrossRef]

- Gunn, T. Vibrations and jello effect causes and cures. Flite Test. https://www.flitetest.com/articles/vibrations-and-jello-effect-causes-and-cures.

- Sabo, C.; Chisholm, R.; Petterson, A.; Cope, A. A lightweight, inexpensive robotic system for insect vision. Arthropod Structure and Development 2017, 46, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azil, K.; Altuncu, A.; Ferria, K.; Bouzid, S.; Sadık, Ş.A.; Durak, F.E. A faster and accurate optical water turbidity measurement system using a CCD line sensor. Optik 2021, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelot, O.; Marcelot, C.; Corbière, F.; Martin-Gonthier, P.; Estribeau, M.; Houdellier, F.; Rolando, S.; Pertel, C.; Goiffon, V. A new TCAD simulation method for direct CMOS electron detectors optimization. Ultramicroscopy 2023, 243, 113628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, T.; Su, R.; Chen, Y.; Fu, S. Detection method of manufacturing defects on aircraft surface based on fringe projection. Optik 2020, 208, 164332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.H.; Asemani, D. Surface defect detection in tiling Industries using digital image processing methods: Analysis and evaluation. ISA Transactions 2014, 53, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Séguin-Charbonneau, L.; Walter, J.; Théroux, L.D.; Scheed, L.; Beausoleil, A.; Masson, B. Automated defect detection for ultrasonic inspection of CFRP aircraft components. NDT and E International 2021, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsmots, I.; Teslyuk, V.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Lukashchuk, Yu. , Kazymyra I.; Holovatyy A.; Opotyak Yu. An Approach to the Implementation of a Neural Network for Cryptographic Protection of Data Transmission at UAV. Drones 2023, 7, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.M.; Starnes, S.; Strickland, N.; Kenny, P.; Williams, C. The detection, inspection, and failure analysis of a composite wing skin defect on a tactical aircraft. Composite Structures 2016, 145, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Nowakowski and A. Idzkowski, “Ultra-wideband signal transmission according to European regulations and typical pulses,” 2020 International Conference Mechatronic Systems and Materials (MSM), Bialystok, Poland, 2020, pp. 1–4. /. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Mukherjee, T.; Chatterjee, M.; Pasiliao, E. Adaptive streaming of HD and 360° videos over software-defined radios. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 2020, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva Kumar, K.; Sasi Kumar, S.; Mohan Kumar, N. Efficient video compression and improving quality of video in communication for computer encoding applications. Computer Communications 2020, 153, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanand, S.; Kadam, S.; Bhoir, P.; Manza, R.R. FPV Camera and Receiver for Quadcopter using IoT and Smart Devices. In 2017 International Conference on Circuit, Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT); IEEE, 2017; pp 1-5.

- Song, H.; Lee, J.; Yoo, J. Performance Evaluation of 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz FPV Systems for Drone Racing. Journal of Communications and Networks 2019, 21, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.; Kim, J.; Shim, D. A Novel Multi-Channel Access Scheme for FPV Racing Drones. Sensors 2019, 20, 4205. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Lin, L.; Yang, M.; Shen, X. A Diversity Reception Scheme for FPV Video Transmission. In 2018 17th International Symposium on Antenna Technology and Applied Electromagnetics (ANTEM) & Canadian Radio Science Meeting; IEEE, 2018; pp 1-2.

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, L.; Su, S. Multi-Rate FEC Mechanism for High-Throughput FPV Video Transmission in Drone Racing. Sensors 2021, 21, 4205. [Google Scholar]

- Nayagam, A.; Sundaresan, N.; Srinivasan, V. Different Methods of Defect Detection - A Survey. International Journal of Advance Research in Computer Science and Management 2022, 4, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- K. N.; S.; D.; G. Fast and Efficient Detection of Crack Like Defects in Digital Images. ICTACT Journal on Image and Video Processing 2011, 01, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú Cabrera, D.; Utzmann, J.; Förstner, R. The adaptive Gaussian mixtures unscented Kalman filter for attitude determination using light curves. Advances in Space Research 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cabello, F.; Leon, J.; Iano, Y.; Arthur, R. Implementation of a fixed-point 2D Gaussian Filter for Image Processing based on FPGA. Signal Processing - Algorithms, Architectures, Arrangements, and Applications Conference Proceedings, SPA, 2015-Decem 2015, 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Sugano, H.; Miyamoto, R. Highly optimized implementation of OpenCV for the Cell Broadband Engine. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2010, 114, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culjak, I.; Abram, D.; Pribanic, T.; Dzapo, H.; Cifrek, M. A brief introduction to OpenCV. MIPRO 2012 - 35th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics - Proceedings 2012, 1725– 1730.

- Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Wang, P.; Sun, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X. Uncovering the optimal structural characteristics of flocs for microalgae flotation using Python-OpenCV. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Johnson, C.D.; Lee, R.W. W. Applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Disaster Response and Relief Efforts. Journal of Disaster Management 2019, 15, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

| Sectors | Previous Study | Reference |

| Bridge inspection | This research aims to compare plenty of different cameras that are suitably used for the inspection process. Moreover, this study encourages safety during the inspection process without involving humans physically inspecting the bridge. |

[44] |

| Overhead power line inspection |

The Lidar-aided inspection approach creates collision-free paths that decrease the risk of any accident. This research has concluded that Lidar has provided precise information on their surrounding topography and vegetation and supports a good navigation basis for UAV-based powerline inspections. | [45] |

| Porcelain insulators Inspection |

The performance of YOLOv4 in object detection is outstanding because it has a high object detection accuracy. The idea of a flight path strategy for UAVs to inspect proved to save time and energy. | [46] |

| Human activity recognition (HAR) | This paper implemented several types of CNN, such as 3D and 2D CNNs. The computational barriers inhibiting the use of deep learning-based HAR systems on drones may be removed by this research. | [47] |

| Early sinkhole detection | This research applies a thermal infrared camera attached to a drone to detect a potential sinkhole. The combination of machine learning CNN and thermal infrared has shown a tremendous positive impact in detecting a high possibility of sinkhole occurrence’s location. |

[48] |

| Building external wall inspection | A deep learning module was implemented to scan any flaws obtained on the wall surface. UAV starts the process by capturing the wall image to transform the defect locations into coordinates. Next, the deep learning process will determine the presence of defects. | [49] |

| Bridge inspection | Machine learning (CNN) was used to detect the flaws on columns and beams. The image captured by the UAV is adjusted to increase the quality of the image. | [50] |

| High-speed railroad inspection | Real-time defect detection is developed to scan potential safety hazards (PSH) in the surrounding high-speed railroad. Mask R-CNN segment is applied to the image processing program to detect any flaws in the surrounding. | [51] |

| Petroleum | In a simulated oil spill setting in arctic conditions, the capacities of several active/passive sensors, including a visible-near infrared (VNIR) hyperspectral camera (Rikola), thermal IR camera (Optris and Work swell Wiris), and laser fluorosensor (BlueHawk) onboard an X8 Video drone were evaluated. | [52] |

| Plantation (sugarcane crops) | Yano et al. (2016) used RGB images and the Random Forest (RF) classifier to identify weeds in a sugarcane field. Machine learning algorithms such as RF, SVM, ANN, and Deep Learning (DL) have been utilized with remotely sensed data for sugarcane monitoring with good accuracy (Wang et al., 2019) | [53] |

| Mapping | Agisoft PhotoScan1 1.2.6 (Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia) was used to further process the set after a thorough inspection to create 3D textured digital models. In order to build 3D meshes, specific procedures were followed, including “arbitrary” mesh triangulation, “high” quality and “mild” depth filtering, and “ultra-high” photo alignment Urbanová et al. (2015). | [54] |

| Electricity infrastructure | R-CNN generates region proposals for extracting smaller chunks of the original image that consist of the items under examination. In order to accomplish this, a selective search method is used, which employs segmentation to guide the image sampling process and exhaustive search for potential item positions. Due to the selection algorithm, only the necessary number of regions are selected. The image data from each region is then wrapped into squares and sent to a CNN in the following step. | [55] |

| Sloped road inspection | An obstacle identification and distance measuring approach for sloped roads based on Vision IMU based detection and range method (VIDAR) is proposed. First, the road photos are collected and processed. The VIDAR collects the road distance and slope information the digital map provides to detect and eliminate false obstacles (those for which no height can be determined). Tracking the obstacle’s lowest point determines its moving condition. Finally, experimental analysis is carried out using simulation and real-world tests. | [56] |

| Research Gap: UAVs show excellent performance in solving problems faced by several industries. However, difficulties in handling UAVs also were identified, such as photographic quality diminishes in dark environments and UAVs cannot clear debris or other obstructions. | ||

| Lens Focal Length (mm) | Approximate FOV (degree) |

| 1.6 | 170+ |

| 1.8 | 160 – 170 |

| 2.1 | 150 – 160 |

| 2.3 | 140 – 150 |

| 2.5 | 130 – 140 |

| Method | Previous Study | Reference |

| Fringe projection | A method used in this paper is rivet and seam extraction to allow a precise and accurate 3D figure of the structure. The technology of surface structured light measurement was applied to the 3D figure. | [71] |

| Wavelet transform | Surface defect detection in tiling industries scans cracks, pinholes, scratches, and blobs on the ceramic surface. Wavelet transform is applied to filter for soft texture images such as ceramic and textile. | [72] |

| Ultrasonic | Background echo filter (BWEF) filters the ultrasonic C-scan to determine the location with a different depth than the neighboring ones. | [73] |

| Ultrasonic | The lower and upper wing skins were subjected to non-destructive testing (NDT) using an ultrasonic C-scan Mobile Automated Ultrasonic Scanner (MAUS) with a 5 MHz transducer. | [74] |

| Research Gap: Current technologies were observed and studied in detecting the defects. The defect has criteria that require high-technology tools to scan it accurately. | ||

| Band | Channels | ||||||||

| CH1 | CH2 | CH3 | CH4 | CH5 | CH6 | CH7 | CH8 | ||

| Band 1 | F – FS/IRC | 5740 | 5760 | 5780 | 5800 | 5820 | 5840 | 5860 | 5880 |

| Band 2 | E – Lumenier/DJI | 5705 | 5685 | 5665 | 5752 | 5885 | 5905 | 5925 | 5866 |

| Band 3 | A – Boscam A | 5865 | 5845 | 5825 | 5805 | 5785 | 5765 | 5745 | 5725 |

| Band 4 | R - RaceBand | 5658 | 5695 | 5732 | 5769 | 5806 | 5843 | 5880 | 5917 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).