Submitted:

26 August 2023

Posted:

28 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

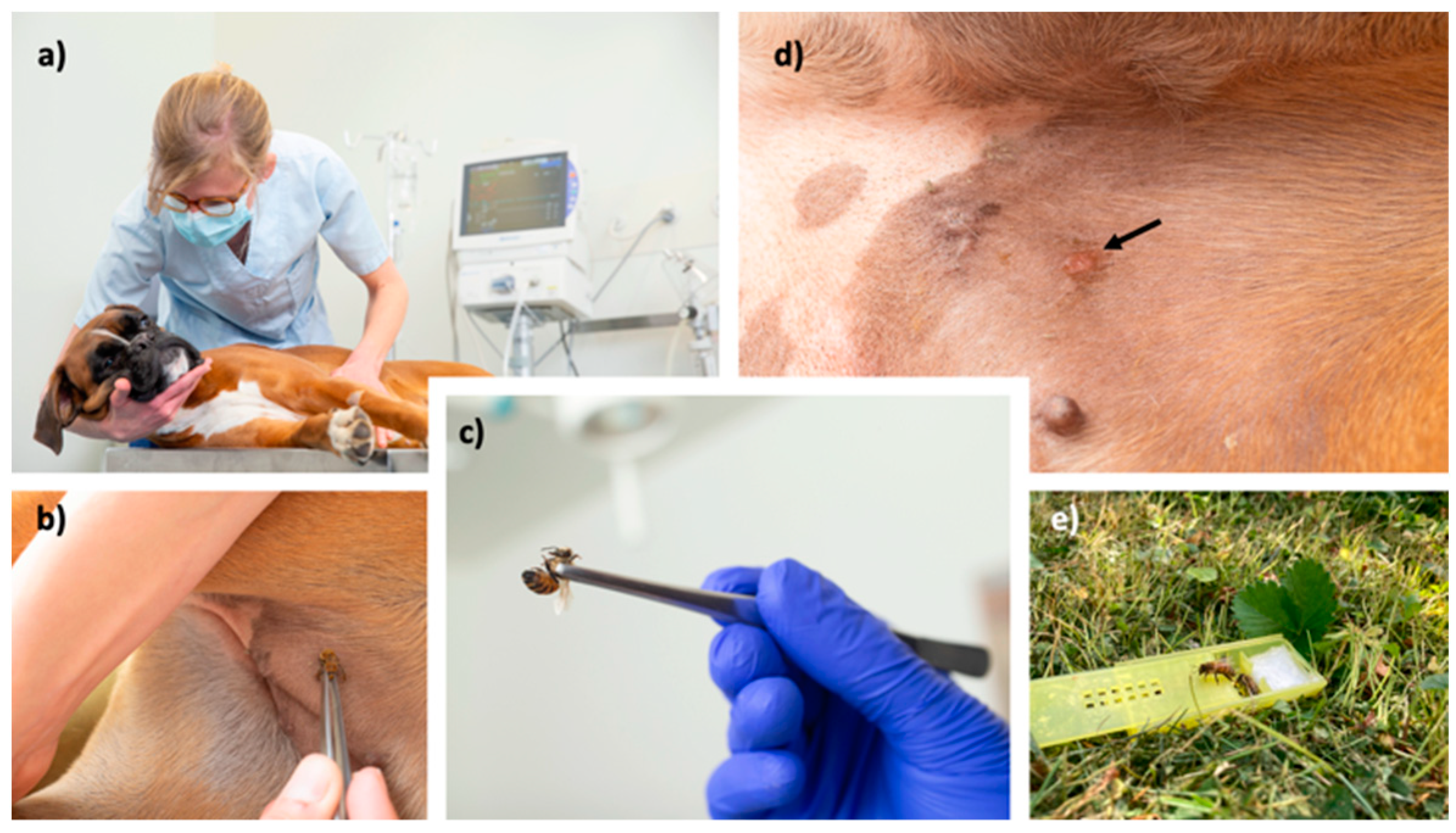

2.1. Study population

- Moderate or severe anaphylactic reaction, following an observed or suspected bee and/or wasp sting (grading system is shown in Table 1)

- A positive bee- and/or wasp-specific IgE serology or skin test

2.2. Anaphylaxis grading scale

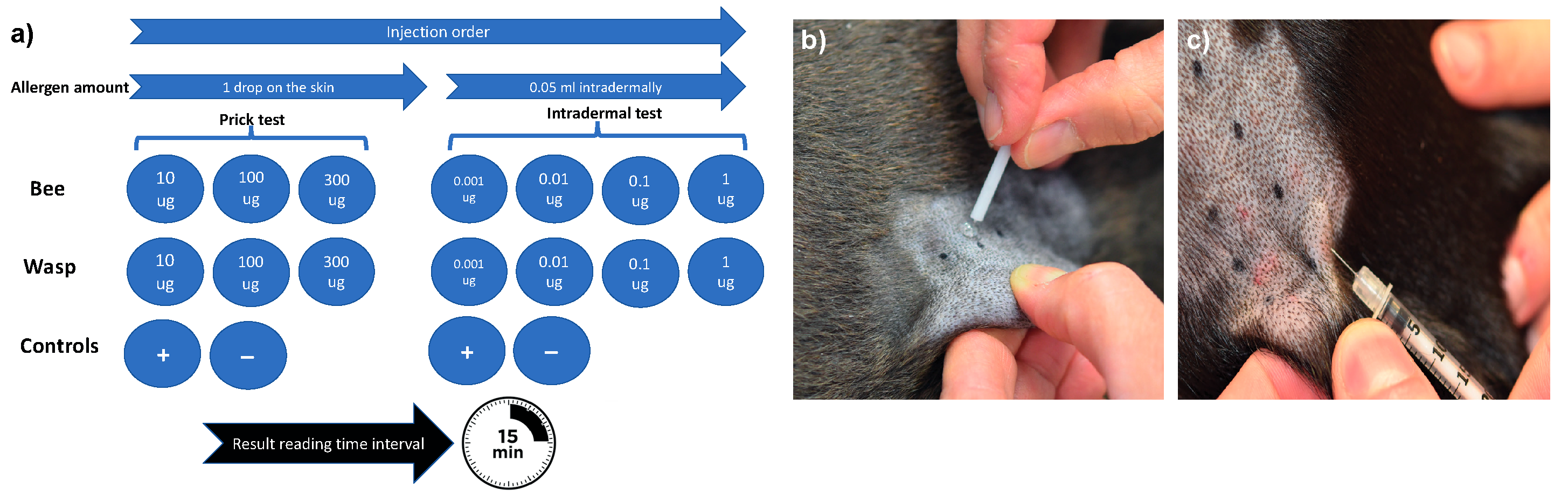

2.3. Allergy testing

2.4. Allergen selection for VIT

2.5. Protocol(s) for VIT

2.6. Safety and efficacy evaluation

2.7. Endpoints and statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical data

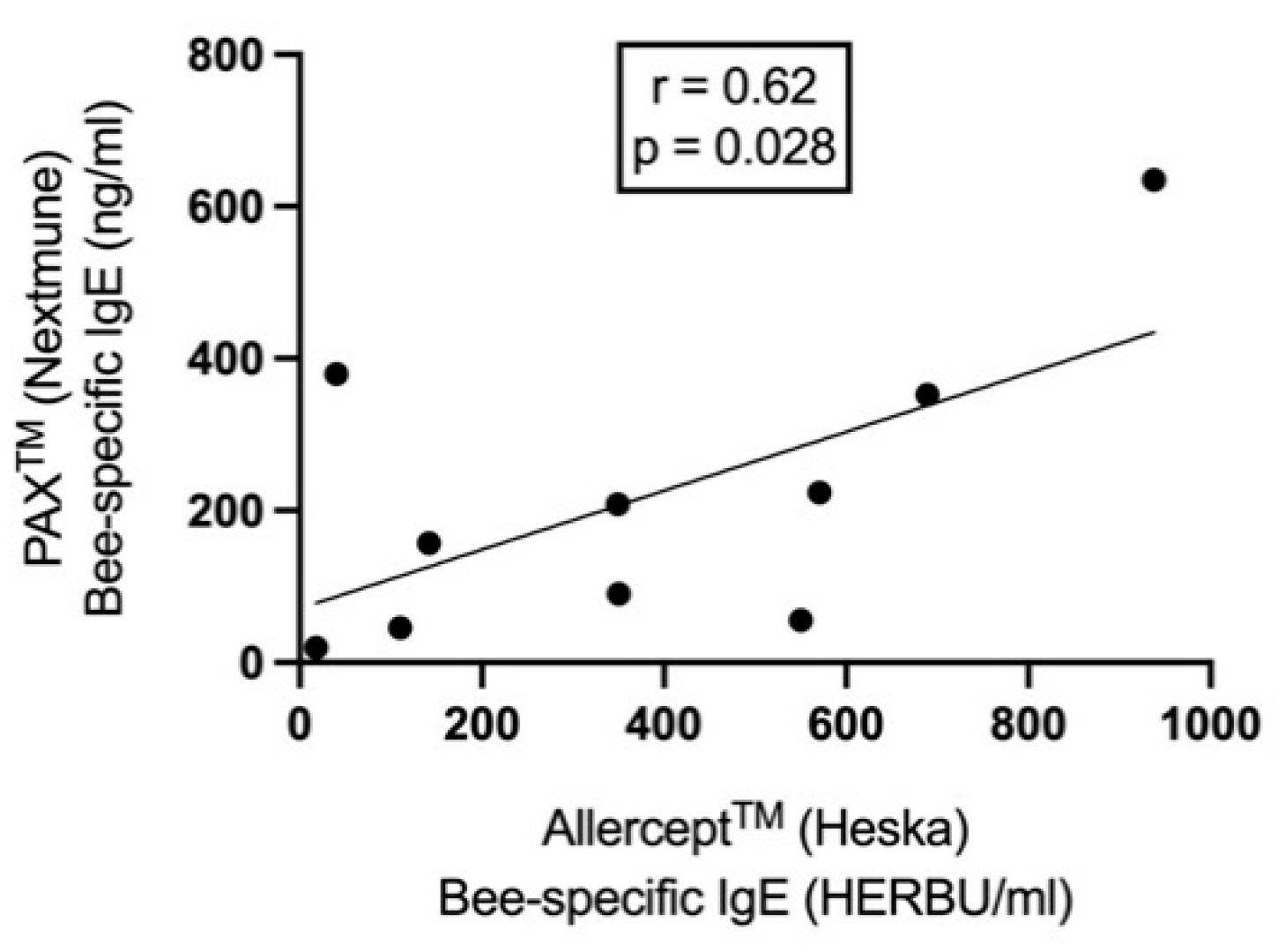

3.2. Data from in vitro and in vivo allergic testing

3.3. Data on venom immunotherapy outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilo BM, Bonifazi F. Epidemiology of insect-venom anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;8:330-337.

- Jennings A, Duggan E, Perry IJ, et al. Epidemiology of allergic reactions to hymenoptera stings in Irish school children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010;21:1166-1170. [CrossRef]

- Rostaher A. Bienen- und Wespenallergien bei Hunden - Von Akutbehandlung bis zur Desensibilisierung. Kleintier Konkret 2018:13-19.

- Rostaher A, Hofer-Inteeworn N, Kummerle-Fraune C, et al. Triggers, risk factors and clinico-pathological features of urticaria in dogs - a prospective observational study of 24 cases. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:38-e39. [CrossRef]

- Antonicelli L, Bilo MB, Bonifazi F. Epidemiology of Hymenoptera allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;2:341-346.

- Boyle RJ, Elremeli M, Hockenhull J, et al. Venom immunotherapy for preventing allergic reactions to insect stings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD008838. [CrossRef]

- Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1144-1150. [CrossRef]

- Adams KE, Tracy JM, Golden DBK. Anaphylaxis to Stinging Insect Venom. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2022;42:161-173.

- Golden DBK, Kagey-Sobotka A, Norman PS, et al. Outcomes of allergy to insect stings in children, with and without venom immunotherapy. New Engl J Med 2004;351:668-674. [CrossRef]

- Hunt KJ, Valentine MD, Sobotka AK, et al. A controlled trial of immunotherapy in insect hypersensitivity. N Engl J Med 1978;299:157-161. [CrossRef]

- Sturm GJ, Varga EM, Roberts G, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy 2018;73:744-764. [CrossRef]

- Bilo BM, Rueff F, Mosbech H, et al. Diagnosis of Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy 2005;60:1339-1349. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman DR, Jacobson RS. Allergens in Hymenoptera Venom .12. How Much Protein Is in a Sting. Ann Allergy 1984;52:276-278.

- Goldberg A, Confino-Cohen R. Bee venom immunotherapy - how early is it effective? Allergy 2010;65:391-395.

- Lerch E, Muller UR. Long-term protection after stopping venom immunotherapy: results of re-stings in 200 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;101:606-612. [CrossRef]

- Rueff F, Vos B, Oude Elberink J, et al. Predictors of clinical effectiveness of Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy. Clin Exp Allergy 2014;44:736-746. [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos N, Mayer U. Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy without human serum albumin as a stabilizer in a canine patient. Vet Rec Case Rep 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Boord M. Chapter 29 - Venomous Insect Hypersensitivity In: Noli C, Foster AP, Rosenkrantz W., ed. Veterinary Allergy Somerset, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2014 (first edition);191-194.

- Bryden S. Venom allergy in dogs: A multicentre retrospective study. Proceedings Australia College of Veterinary Science Dermatology Chapter Science Week 2009.

- Ewing TS, Dong C, Boord MJ, et al. Adverse events associated with venomous insect immunotherapy and clinical outcomes in 82 dogs (2002-2020). Vet Dermatol 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rostaher A, Mueller R, Meile L, et al. Venom Immunotherapy for Hymenoptera Allergy in a Dog. Veterinary Dermatology 2020:In press. [CrossRef]

- Moore A, Burrows AK, Rosenkrantz WS, et al. Modified rush venom immunotherapy in dogs with Hymenoptera hypersensitivity. Vet Dermatol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stedman K, Lee K, Hunter S, et al. Measurement of canine IgE using the alpha chain of the human high affinity IgE receptor. Vet Immunol Immunop 2001;78:349-355. [CrossRef]

- Rostaher A, Mueller RS, Meile L, et al. Venom immunotherapy for Hymenoptera allergy in a dog. Vet Dermatol 2021;32:206-e252. [CrossRef]

- Hensel P, Santoro D, Favrot C, et al. Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Vet Res 2015;11:196. [CrossRef]

- Ewing TS, Dong C, Boord MJ, et al. Adverse events associated with venomous insect immunotherapy and clinical outcomes in 82 dogs (2002-2020). Vet Dermatol 2022;33:40-e14. [CrossRef]

- Gouel-Cheron A, Harpan A, Mertes PM, et al. Management of anaphylactic shock in the operating room. Presse Med 2016;45:774-783. [CrossRef]

- Rueff F, Przybilla B. Stichprovokation. Indikation und Durchführung. Hautarzt 2014:796-801.

- Goldberg A, Confino-Cohen R. Bee venom immunotherapy - how early is it effective? Allergy 2010;65:391-395.

- Novak N, Mete N, Bussmann C, et al. Early suppression of basophil activation during allergen-specific immunotherapy by histamine receptor 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:1153-1158 e1152. [CrossRef]

- Confino-Cohen R, Melamed S, Goldberg A. Debilitating beliefs, emotional distress and quality of life in patients given immunotherapy for insect sting allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 1999;29:1626-1631. [CrossRef]

- Elberink JNGO, de Monchy JGR, van der Heide S, et al. Venom immunotherapy improves health-related quality of life in patients allergic to yellow jacket venom. J Allergy Clin Immun 2002;110:174-182.

- Eitel T, Zeiner KN, Assmus K, et al. Impact of specific immunotherapy and sting challenge on the quality of life in patients with hymenoptera venom allergy. World Allergy Organ J 2021;14:100536. [CrossRef]

- Fischer J, Teufel M, Feidt A, et al. Tolerated wasp sting challenge improves health-related quality of life in patients allergic to wasp venom. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:489-490. [CrossRef]

- Elberink JNGO, van der Heide S, Guyatt GH, et al. Analysis of the burden of treatment in patients receiving an EpiPen for yellow jacket anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immun 2006;118:699-704.

- Findeis S, Craig T. The relationship between insect sting allergy treatment and patient anxiety and depression. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014;35:260-264. [CrossRef]

- Demsar Luzar A, Korosec P, Kosnik M, et al. Hymenoptera Venom Immunotherapy: Immune Mechanisms of Induced Protection and Tolerance. Cells 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Navas A, Ruiz-Leon B, Serrano P, et al. Natural and Induced Tolerance to Hymenoptera Venom: A Single Mechanism? Toxins (Basel) 2022;14.

- Assmus K, Meissner M, Kaufmann R, et al. Benefits and limitations of sting challenge in hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergol Select 2021;5:45-50. [CrossRef]

- Rueff F, Przybilla B. [Sting challenge: indications and execution]. Hautarzt 2014;65:796-801.

- Muller U, Hari Y, Berchtold E. Premedication with antihistamines may enhance efficacy of specific-allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:81-86. [CrossRef]

- Wang KY, Friedman DF, DaVeiga SP. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to human serum albumin in a child undergoing plasmapheresis. Transfusion 2019;59:1921-1923. [CrossRef]

- Stoevesandt J, Hofmann B, Hain J, et al. Single venom-based immunotherapy effectively protects patients with double positive tests to honey bee and Vespula venom. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:33. [CrossRef]

- Blank S, Bilo MB, Grosch J, et al. Marker allergens in Hymenoptera venom allergy — Characteristics and potential use in precision medicine. Allergo J Int 2021;30:26-38.

- Sturm GJ, Kranzelbinder B, Schuster C, et al. Sensitization to Hymenoptera venoms is common, but systemic sting reactions are rare. J Allergy Clin Immun 2014;133:1635-+. [CrossRef]

- Hollstein MM, Matzke SS, Lorbeer L, et al. Intracutaneous Skin Tests and Serum IgE Levels Cannot Predict the Grade of Anaphylaxis in Patients with Insect Venom Allergies. J Asthma Allergy 2022;15:907-918. [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier B, Aberer W, Bokanovic D, et al. Simultaneous intradermal testing with hymenoptera venoms is safe and more efficient than sequential testing. Allergy 2013;68:542-544. [CrossRef]

- Adams KE, Tracy JM, Golden DBK. Anaphylaxis to Stinging Insect Venom. Immunol Allergy Clin 2022;42:161-173. [CrossRef]

- Feindor M, Heath MD, Hewings SJ, et al. Venom Immunotherapy: From Proteins to Product to Patient Protection. Toxins (Basel) 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini AE, Berra D, Rizzini FL, et al. Flexible approaches in the design of subcutaneous immunotherapy protocols for Hymenoptera venom allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;97:92-97. [CrossRef]

- Pospischil I, Kagerer M, Cozzio A, et al. Comparison of the safety profiles of three different Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy protocols - a retrospective two-center study of 143 patients. Exp Dermatol 2021;30:E3-E3.

- Golden DB, Valentine MD, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Regimens of Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:620-624. [CrossRef]

- Confino-Cohen R, Rosman Y, Goldberg A. Rush Venom Immunotherapy in Children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:799-803.

- Rueff F, Przybilla B, Bilo MB, et al. Predictors of side effects during the buildup phase of venom immunotherapy for Hymenoptera venom allergy: the importance of baseline serum tryptase. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:105-111 e105. [CrossRef]

- Roumana A, Pitsios C, Vartholomaios S, et al. The safety of initiating Hymenoptera immunotherapy at 1 mu g of venom extract. J Allergy Clin Immun 2009;124:379-381.

- Simioni L, Vianello A, Bonadonna P, et al. Efficacy of venom immunotherapy given every 3 or 4 months: a prospective comparison with the conventional regimen. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2013;110:51-54. [CrossRef]

- Rueff F, Wenderoth A, Przybilla B. Patients still reacting to a sting challenge while receiving conventional Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy are protected by increased venom doses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:1027-1032. [CrossRef]

- Golden DB, Kwiterovich KA, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Discontinuing venom immunotherapy: outcome after five years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;97:579-587. [CrossRef]

- Keating MU, Kagey-Sobotka A, Hamilton RG, et al. Clinical and immunologic follow-up of patients who stop venom immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1991;88:339-348. [CrossRef]

- Golden DB, Kwiterovich KA, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Discontinuing venom immunotherapy: extended observations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;101:298-305. [CrossRef]

| Grade | Organ system involved | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – mild | Skin | Generalized erythema, urticaria and/or angioedema |

| 2 - moderate | Gastrointestinal, respiratory, cardiovascular | Dyspnea, stridor, wheeze, nausea, vomiting, and/or abdominal pain |

| 3 - severe | Respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological | Cyanosis, pallor, SpO2 <92%, hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg), collapse, loss of consciousness and/or incontinence |

| Injection No | Allergen amount (μg) | Concentration (μg/ml) | Injection volume (ml) |

Observation time (minutes) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 20 |

| 2 | 1 | 10 | 0.1 | 20 | |

| 3 | 10 | 100 | 0.1 | 20 | |

| 4 | 20 | 100 | 0.2 | 20 | |

| 5 | 30 | 100 | 0.3 | 20 | |

| 6 | 40 | 100 | 0.4 | 20 | |

| Day 7 | 7 | 50 | 100 | 0.5 | 20 |

| 8 | 50 | 100 | 0.5 | 20 |

| Signalment at VIT initiation | Clinical data related to the sting event | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog No | Breed | Age (years) |

Sex | Castration status | Weight (kg) |

No of sting episodes | No of anaphylaxis episodes | Age 1st sting (years) | Age 1st anaphylaxis episode (years) | Reaction severity (1st sting) | Reaction severity (last sting) |

| 1 | Boxer | 3.0 | female | intact | 28.6 | 2 | 2 | 0.75 | 2.8 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | Toy poodle | 2.0 | male | intact | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 3 | N/A |

| 3 | Dachshund | 4.0 | female | spayed | 5.8 | 2 | 2 | 3.9 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | Dachshund | 1.0 | female | spayed | 5.2 | 2 | 2 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | Entlebucher Sennenhund | 1.0 | female | spayed | 18.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | N/A |

| 6 | Yorkshire Terrier | 2.2 | female | spayed | 4.1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | Cross breed | 7.4 | male | castrated | 10.5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 3 | N/A |

| 8 | Malinois | 3.1 | female | spayed | 25.1 | 3 | 2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | Dobermann | 0.8 | male | intact | 31.2 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3 | N/A |

| 10 | Beagle | 8.0 | female | spayed | 13.9 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Dog No | Bee allergens | Wasp allergens | Insect identification by owner | Time interval sting to testing | ||||||

| Prick | IDT | Serology | Prick | IDT | Serology | |||||

| Positive at following concentrations (mg /ml) | Allercept (HERBU/ml) | PAX (ng/ml) | Positive at following concentrations (mg /ml) | Allercept (HERBU/ml) | PAX (ng/ml) | |||||

| 1 | Neg. | 1 | 142 | 156.67 | Neg. | Neg. | 116 | 28.02 | Bee | 4 weeks |

| 2 | 100-300 | 1 | 350 | 90.54 | Neg. | Neg. | 84 | 27.2 | Bee | 3 weeks |

| 3 | Neg. | Neg. | 938 | 634.7 | Neg. | Neg. | 45 | 23.62 | Bee | 10 days |

| 4 | Neg. | 0.01-1 | 349 | 208.14 | Neg. | 0.01-1 | 16 | 32.22 | Bee | 5 weeks |

| 5 | Neg. | 0.01-1 | 110 | 45.77 | Neg. | 0.01-1 | 16 | 27.82 | Bee | 6 weeks |

| 6 | 10-300 | 1 | 40 | 379.62 | Neg. | Neg. | 2 | 25.26 | Bee | 1 year |

| 7 | 300 | 0.1- 1 | 550 | 55.95 | Neg. | 0.1-1 | 36 | 27.33* | Bee | 4 months |

| 8 | Neg. | 0.01-1 | 689 | 352 | Neg. | Neg. | 23 | 27 | Bee | 2 months |

| 9 | Neg. | Neg. | 18 | 19.81 | Neg. | 1 | 18 | 25.45 | Wasp | 4 weeks |

| 10 | Neg. | 0.01- 1 | 571 | 223.44 | Neg. | 1 | 427 | 66.02 | Bee & wasp | 1 year |

| Dog No | PAX results in bee allergic dogs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bee extract | Bee allergen components | |||||

| Api m | nApi m 1 | rApi m 2 | rApi m 3 | rApi m 5 | rApi m 10 | |

| 1 | 156.67 | 227.91 | 82.79 | 31.33 | 20.66 | 577.49 |

| 2 | 90.54 | 132.83 | 633.33 | 110.07 | 19.11 | 633.33 |

| 3 | 634.7 | 722.22 | 111.15 | 804.65 | 18.3 | 1478.85 |

| 4 | 208.14 | 592.32 | 853.02 | 987.17 | 21.57 | 1061.81 |

| 5 | 45.77 | 42.55 | 33.8 | 24.04 | 19.35 | 167.46 |

| 6 | 379.62 | 958.41 | 20.35 | 82.96 | 19.52 | 23.18 |

| 7 | 55.95 | 55.95 | 57.91 | 128.53 | 18.81 | 133.62 |

| 8 | 352 | 386 | 344 | 60 | 22 | 1657 |

| 10 | 223.44 | 356 | 234.32 | 467.19 | 19.23 | 1018.54 |

| Dog No | VIT allergen source | Premedication with cetirizine | Side effects VIT | Re-stings | VIT follow-up (days) | |||

| Induction phase | Maintenance phase | Re-sting No | Clinical signs | VIT duration at first re-sting (days) | ||||

| 1 | Bee* | Yes | No | No | 1 | No | 360 | 620 |

| 2 | Bee | Yes | No | No | 1 | No | 269 | 614 |

| 3 | Bee | Yes | No | No | 1 | Local angioedema | 176 | 375 |

| 4 | Bee | Yes | No | No | 0 | Not stung | N/A | 312 |

| 5 | Bee | Yes | No | No | 0 | Not stung | N/A | 312 |

| 6 | Bee | Yes | No | No | 1 | No | 182 | 409 |

| 7 | Bee | Yes | No | No | 0 | Not stung | N/A | 202 |

| 8 | Bee | No | Mild pruritus | No | 1 | No | 12 | 90 |

| 9 | Wasp | No | Mild pruritus | No | 1 | No | 30 | 291 |

| 10 | Bee* & wasp | No | No | No | 1 | No | 307 | 702 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).