1. Introduction

There are two ways for lipophilic cations to cross a phospholipid bilayer. Single molecules of the cations with small charged moieties (e.gbenzalkonium) do not penetrate the bilayer because, in the aqueous phase, the moiety is attached to a number of water molecules via hydrogen bonds. Thus, such an aggregate does not penetrate between the phospholipid molecules for sterical reasons. Additionally, the electrostatic Born's energy of an ion in a dielectric medium (membrane) scales as the inverse ion radius [

1]; for this reason, smaller ions have higher electrostatic energy inside the membrane as compared to larger ones. Still, such lipophilic molecules can cross the membrane via transient pores. If the effective cross-section of polar parts of the ions is larger than the cross-section of their hydrophobic tail (which is usually the case), they locally induce a convex patch in the membrane monolayer, i.e., induce a positive spontaneous curvature [

2]. Such curvature generally favors formation of pores, and such cations can act as a detergent. If the cation surface concentration increases, the curvature of the monolayer changes leading to the formation of the pore [

3]. Next, the molecules diffuse to the opposite monolayer, and the pore closes spontaneously. Similar effect was observed for amphipathic peptide PGLa [

4]. Upon incorporation into an outer monolayer of the membrane of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUV), this peptide makes the membrane locally convex. An increase in the peptide concentration leads to the formation of small transient pores, via which the peptide passes to the inner monolayer of GUVmembrane [

4].

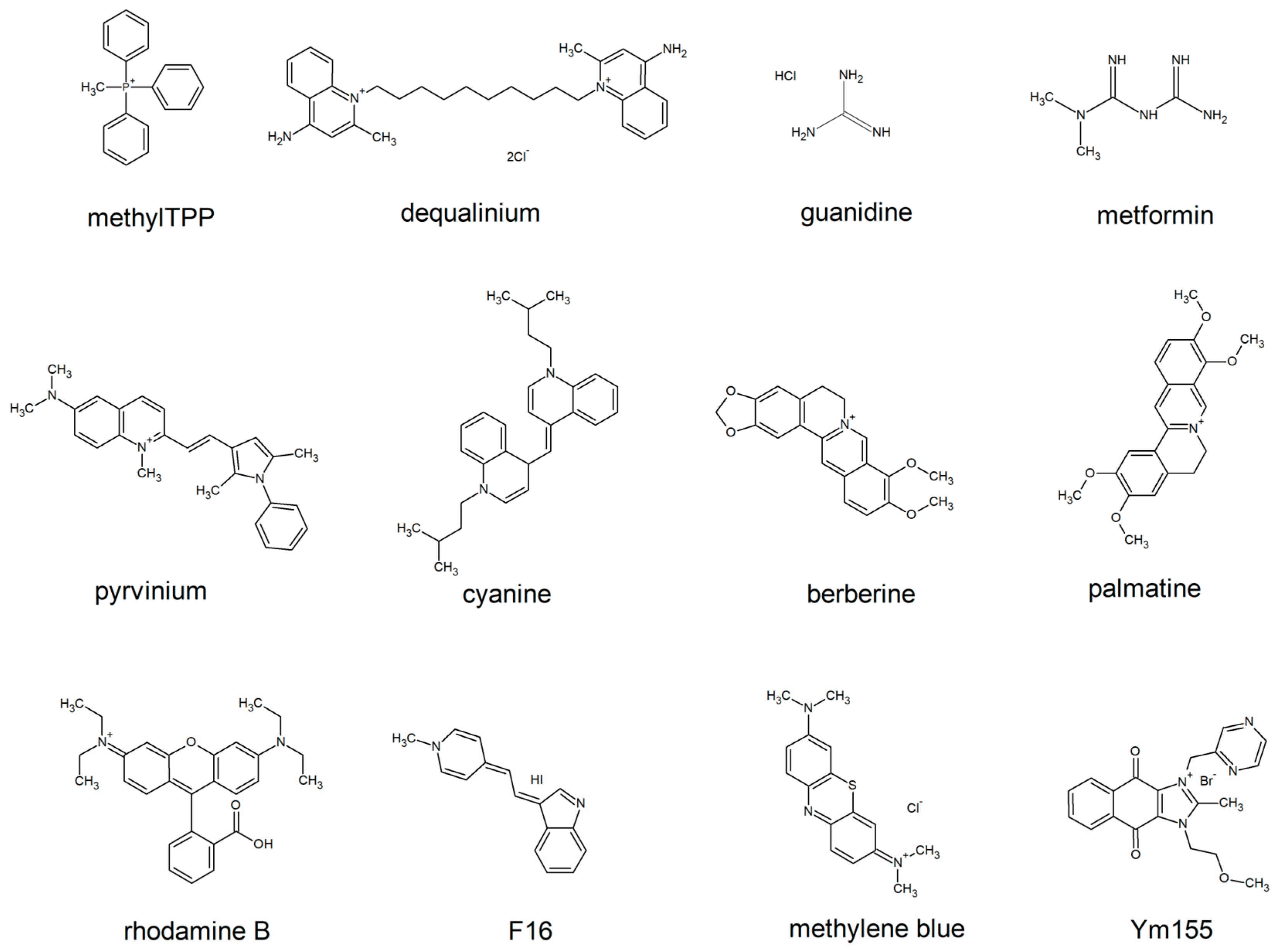

An alternative way is to cross without the disruption of integrity of the lipid bilayer. The lipocations which lack the voluminous layer of hydrogen bond-attached water molecules are capable of this. To avoid the formation of the halo of water molecules, the charge has to be either masked by hydrophobic groups, or delocalized, or both (e.g triphenylphosphonium (TPP) and rhodamine, respectively,

Figure 1). The latter group of lipocations is likely to be less harmful for the biological membranes than the former one. Indeed, such lipocations do not make pores in the membrane, which depolarize cell plasma membrane and enable the release of the cytosolic constituents. Chemical formulas of the most known penetrating cations of this group are shown by

Figure 1. These lipocations, or their derivatives (e.g alkylated forms, dimers, etc.) are being widely used to deliver antioxidants and other types of chemical moieties to the mitochondria of human cells to improve their physiology.

Nevertheless, even the molecules of this type of lipocations could be toxic for cells. In our review we focus on the side effects of this type of electrophilic carriers.

Triphenylphosphonium

Tetraphenylphosphonium and the alkylated derivatives of triphenylphosphonium are probably the most well studied artificial penetrating cations. Their toxic effects were studied in a variety of experimental systems. When alkylated derivatives of TPP are added to mitochondria, they stimulate respiration. This effect is due to temporary depolarization of mitochondria due to the passage of a charged molecule through the phospholipid bilayer. Moreover, alkyl-TPP can stimulate protonophore activity of free fatty acids [

5]. At the same time, high concentrations inhibit respiration. That could be due to the direct inhibition of respiratory enzymes or mediated by their detergent action on mitochondrial inner membrane (see for review [

6]).

At the level of whole cells, we have shown that one of TPP derivatives, C

12TPP, simultaneously induces the expression of multidrug resistance pump (MDR) proteins and also inhibits their activity. The inhibition is not toxic for yeast cells, but the inhibition might be used to enhance the effect of antimycotic drugs-MDR substrates [

7,

8]. C

12TPP has been shown to cause hepatotoxicity, but the cellular mechanisms are still not clear. Probably, the liver damage is due to apoptotic cell death because TPP causes apoptosis in the cultured hepatocyte AML12 cell line [

9].

Additionally, one can hypothesise that the apoptosis of liver cells induced by TPP and similar large-headed lipocations is due to the disturbance of cell signaling. It has been shown that several gangliosides having large polar heads and regular lipid tails can induce apoptosis in T-lymphocytes [

10,

11]. Gangliosides are also known for their ability to alter substantially the ensemble properties of small ordered lipid-protein domains of plasma membranes [

12]; such the domains are also called rafts [

13]. Similar effects have recently been observed for lysolipids, also having relatively large polar heads and small lipid tails [

14]. This result points out that the modification of the raft ensemble properties is not specific to the chemical structure of the particular lipid, e. g, gangliosides, lysolipids. Therefore, TPP might act in a similar manner. Besides, various cell receptors, and especially death receptors, are raft-associated proteins [

15]. Thus, by modifying raft properties, large-headed lipids are able to induce apoptosis even in the absence of specific ligands of death receptors. Thus, the induction of apoptosis and, more generally, the influence on the raft ensemble leading to disturbance of normal cell signaling is, possibly, one more side-effect of penetrating cations.

Not surprisingly, when the excess of C

12TPP is administered to mice, the reason for its toxic effect is also due to liver damage. It has been shown that it triggers massive cell death in liver zone three. In fact, this is also not surprising, because such damage is typically induced by phospho-organic compounds [

16]. The latter points out that, most likely, the toxicity is induced by the degradation products of C

12TPP.

It has also been shown that decyl-triphenylphosphonium can be used to kill multiple myeloma cancer cells. Treatment with C

10TPP increased intracellular steady-state pro-oxidant levels in stem-like and mature multiple myeloma cells. Furthermore, C

10TPP mediated increases in mitochondrial oxidant production were suppressed by ectopic expression of manganese superoxide dismutase [

17], which also points at the prooxidant activity of C

10TPP.

Possibly, the anticancer effect of TPP moiety contributes to the anticancer effect of TPP-linked compounds. Indeed, it is well known that TPP is used to deliver a number of drugs to the mitochondria of tumor cells in order to kill them or to inhibit their proliferation. Interestingly, TPP-based mitochondria-targeted anticancer drugs mainly target tumor cells with high membrane potential. Possibly, the latter is due to an increased accumulation of the positively charged compounds in hyper-polarized mitochondria [

18].

Dequalinium chloride (DQ).

Dequalinium is a quaternary ammonium compound with a well documented antibacterial activity. It is being used to treat several types of infections. While being a penetrating cation, it is also capable of lysing bacterial outer membranes [

19]. Its targets within the bacteria cells include inhibition of glycolysis, inhibition of l F1-ATPase, and protein biosynthesis via interfering with ribosomal activity [

19,

20]. Similar to the alkylated forms of triphenylphosphonium, DQ does display selective toxicity for cancer cells. The anticancer effects of DQ combine a mitochondrial action, a selective inhibition of kinases PKC-α/β and Cdc7/Dbf), and a modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels. DQ selectively targets the mitochondrial membrane of epithelial carcinoma cells, to inhibit cellular energy production. At the mitochondrial level, DQ induces a concentration-dependent oxidative stress by decreasing glutathione (GSH) and increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in a cell type specific manner [

21]. The mitochondrial action is coupled with an interference of the drug with different signaling pathways, such as a downregulation of the Raf/MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt pathways in NB4 leukemia cells [

22,

23,

24]. The mitochondrial action of the drug is considered an early event of its mechanism of action, leading to cell respiratory damages [

22]. The drug-induced damages include a selective depletion of mitochondrial DNA [

25], together with a decrease of the mitochondrial membrane potential, coupled with an increase in free radical production and ATP depletion [

26].

Pyrvinium and cyanine

Pyrvinium, a penetrating cation related to the cyanine dye, has been used for many decades as an anthelmintic. Similar to other clinically used penetrating cations, its mitochondrial localization and targeting are well documented [

33]. In particular, it has been shown that pyrvinium inhibits mitochondrial respiration in a parasitic worm [

34]. Its mitochondrial accumulation is also responsible for its activity against pathogenic fungi such as

Candida auris[

35] and

Aspergillus fumigatus[

36].

Over the past two decades, increasing evidence has emerged showing pyrvinium to be a strong anti-cancer molecule in various human cancers in vitro and in vivo [

33]. Similar to its anti-parasitic activity, the anti-cancer action of pyrvinium relies on the inhibition of mitochondrial function. There is strong evidence that the inhibition of respiratory complex I is largely responsible for the anticancer activity. Indeed, it was shown that the inhibitory concentrations are in the sub-micromolar range [

37,

38]. At the same time, it has been noticed that cancer cell lines with depleted mitochondrial DNA are resistant to pyrvinium[

37,

39].

Complex I is not the only mitochondrial target of pyrvinium. Fumarate reductase [

40] and mitochondrial DNA [

41] were reported as the other ones. The latter is due to the binding of pyrvinium to G-quadruplex structures, which are more frequent in the mitochondrial DNA than in the nuclear one [

42,

43].

Mitochondria are not the exclusive target of pyrvinium. In cytosol, it binds and activates Casein kinase 1α, leading to the degradation of beta-catenin, the key effector of WNT signaling pathway. This also contributes to the anticancer activity of pyrvinium[

44,

45,

46]. It also binds and inhibits a number of other non-mitochondrial proteins, including

ELAVL1/HuR, a post-transcriptional regulator of a set of genes driving the survival of cancer cells [

47,

48,

49] and androgen receptor. The latter property has been explored to treat prostate cancer [

50,

51,

52]

Rhodamine

Rhodamine is a fluorescent dye commonly used in a laboratory practice to visualize mitochondria. Despite its affinity to mitochondria, its toxicity is attributed to the inhibition of cytosolic antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and guaiacol peroxidase (GPOD). It is believed that the inhibition is caused by the degradation products of rhodamine, with degradation being caused by cytochrome P450 [

53,

54]. Similar to the aforementioned penetrating lipocations, Rhodamine is toxic for carcinoma cancer cells [

55]. It has been suggested that the reason for the selective toxicity is due to the fact that these cancer cells have higher electric potential at their plasma membranes than the normal ones, leading to an increased accumulation of the compound within the cells [

56]. At the same time, it should be mentioned that not all cancer types have an increase in plasma membrane (PM) transmembrane potential. Nevertheless, rhodamine was accumulating inside the mitochondria of the carcinoma cells, and its re-localization to cytosol was observed shortly before the cell death [

55]. This observation suggests that mitochondrial damage is the primary reason for the toxicity of rhodamine.

Berberine,palmatine and sanguinarine

Berberine, palmatine and sanguinarine are chemically related compounds produced by plants as a defense against various parasites. Not surprisingly, they have several intracellular targets and affect cellular physiology by a number of independent means. First, berberine and sanguinarine bind DNA and inhibit DNA synthesis [

57]. Palmatine was also shown to induce DNA strand breakage in cultured cancer cells [

58]. It has been shown thatisoquinoline alkaloids interact with DNA as intercalators, or they are arranged in a small groove; their external binding with phosphate groups is also possible [

59]. That might explains why berberine, palmatine and sanguinarine target DNA. Also, the binding of berberine with histone–DNA complexes can cause interferences in vital cellular processes, such as cell division and cause the death of cancer cells by activating the apoptosis in living cells [

60,

61].

Apart from binding DNA, these compounds interact and inhibit several extra- and intracellular proteins. Acetylcholine esterase, butyrylcholinesterase, choline acetyltransferase are inhibited by them, as well as the receptors: alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenergic, nicotinergic, muscarinergic and serotonin

2 ones [

57].

Sanguinarine [13-methyl (1,3) benzodioxolo(5,6-c)-1,3-dioxolo (4,5) phenanthridinium] is more toxic than berberine or palmatine.Additional toxicity of sanguinarine is mostly due to its inhibition of the Na+-K+-ATPase transmembrane protein [

59]. Sanguinarine has also been shown to cause cell membrane damage by lipid peroxidation by free radicals including ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). It also possesses DNA polymerase activity inhibition and causes accumulation of pyruvate due to increased glycogenolysis[

62].

F16

A novel penetrating cation, F16 has been recently shown to possess uncoupling activity. It was also reported that it selectively accumulates in mitochondria of carcinoma cells and inhibits their growth. It has been concluded that mitochondrial toxicity by the means of uncoupling mediates the anticancer activity of F16 [

63].

Methylene blue

Methylene blue induces non-toxic hydrogen peroxide production and in this way protects mitochondria, in particular, from rotenone toxicity. For this reason methylene blue displays a broad range of neuroprotective activity. Its therapeutic effect is also due to the activation of mitochondrial biogenesis, the latter being mediated by Nrf2/ARE signaling cascade. It is believed that the cascade is triggered by H2O2 generation induced by methylene blue [

64].Interestingly, similar to the other penetrating cations, methylene blue does display anticancer activity. It was shown that lung cancer cells treated with methylene blue show reduced activity of Hsp70, the protein which is essential for their survival [

65]. It is not clear whether this is a direct inhibition or a consequence of mitochondrial damage or H2O2 production.

Ym155

In preclinical studies, the imidazolium-based compound Ym155 displayed the suppression of growth of many types of cancer cell lines. The reason for that has started to become clear only recently. It has been shown that, being a penetrating cation, it accumulates in mitochondria, binds to mitochondrial DNA causing energy depletion of the cells [

66].

2. Conclusions

Although it is apparent that small lipophilic cations are mitochondrial toxins, the exact basis for their toxicity is difficult to pinpoint. It has been noticed that the relatively hydrophobic compounds (Rh123) affect electron transport and ATP synthesis while the relatively hydrophilic ones perturb the matrix proteins and functions [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71]

. One can speculate that the membranophilic nature of the cations will also affect the phospholipids of the mitochondrial inner membrane. It is well known that typical lipids of biological membranes have conical (small polar head and large hydrophobic tails) or cylindrical (approximately equal cross-sections of polar head and hydrophobic tails) molecular shapes. At the same time, they have negative or zero spontaneous curvature [

72]. It has been reported that such molecular shapes prevent the spontaneous formation of pores in the planar membranes [

73]. On the contrary, the membranes containing molecules having an inverse conical shape (large polar head, small hydrophobic tail) are prone to forming pores [

74]. Polar groups of lipophilic cations shown in

Figure 1 are likely to have an affinity to the polar heads of lipid bilayer. Indeed, hydrophobic parts of the cations tend to avoid contact with water mooecules, they accumulate inside the hydrophobic membrane core with their aromatic groups being mostly distributed to the polar/hydrophobic interface of a lipid monolayer. Each of the cations shown in

Figure 1 have relatively small hydrophobic parts and large polar or/and aromatic parts. Upon incorporation into the membrane, they, obviously, disturb the ordering of the phospholipids molecules, and this disturbance might cause an increase in the permeability of various small molecules through the membrane either via packing defects or by pore formation. In fact, non-penetrating cations, such as benzalkonium, disturb the lipid packing in a cholesterol-sensitive manner [

75], and inflict the same type of damage to the lipid bilayers as the penetrating cations. This property makes them powerful antibacterial agents. Indeed, while the outer membrane of eukaryotic cells is protected by high content of sterols, bacterial membranes typically lack sterols and thus are vulnerable to the disruption of the ordering of the phospholipid molecules. For example, imidazolium-based ionic liquids can be used as antibacterial agents. Our preliminary data indicate that they do not penetrate through the bilayer, and thus their antibacterial effect is mostly due to the membrane-disrupting action.

Another common feature of the discussed penetrating cations is their anticancer activity, especially against the carcinoma cells. This was noticed a couple decades ago [

21], and further studies confirmed this observation (see above). The reason for that might be due to the fact that typically for energy supply cancer cells rely on glycolysis (Warburg effect). This type of metabolism is typically accompanied by the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. As a certain level of the potential is required for cell survival, such cells use mitochondrial ATP synthase in a reverse fashion for the potential generation. As this type of the potential generation is much less powerful than respiration, even a relatively minor increase in proton conductivity of the mitochondrial inner membrane might be lethal for the cell. Such an increase might be induced by the accumulation of the lipophilic cations in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Indeed, yeast cells which lack functional mitochondrial DNA and rely solely on glycolysis are much more sensitive to the conventional protonophores than the ones with intact mito-DNA [

76]. The same is true for cancer cells: at least certain cancer cell lines are more sensitive to uncouplers than the normal cells [

77]. As all of the penetrating cations in one way or another decrease the membrane potential, this may explain their anti-cancer activity.

An alternative explanation of the anti-cancer activity of the penetrating cations is that many types of cancer cells display an elevated level of the membrane potential. Mitochondria of such cells possess fully functional respiratory chains and, at the same time, non-functional ATP synthase. The inhibition is due to the expression of a special inhibitory protein, IF1. Apparently, the increased charge of mitochondria presumes an increased level of penetrating cations accumulation. As some of them inhibit specific mitochondrial enzymes or bind mitochondrial DNA, such accumulation might render this type of cancer cells more sensitive to the cations than the normal ones.

Another possible reason for the sensitivity of cancer cells to the penetrating cations is that many types of cancer cells show elevated activity of multidrug resistance pumps (MDRs). The reason is that these pumps extrude various chemicals used for chemotherapy. We have recently shown that a set of penetrating cations, alkylrhodamines, are inhibitors of MDRs. In case of yeast, they display strong synergy with antimycotic drugs [

78]. Possibly, in the case of cancer cells the penetrating cations act in the same way.

Author Contributions

A.Z. prepared the illustration; All authors wrote the manuscript and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation grant N 22-24-00533.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Born, M. Volumen Und Hydratationswärme Der Ionen. Zeitschriftfürphysik 1920, 1, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, N.; Rand, R.P. The Influence of Lysolipids on the Spontaneous Curvature and Bending Elasticity of Phospholipid Membranes. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.W. Molecular Mechanism of Antimicrobial Peptides: The Origin of Cooperativity. Biochim.Biophys.Acta 2006, 1758, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, F.; Alam, J.M.; Dohra, H.; Yamazaki, M. Elementary Processes of Antimicrobial Peptide PGLa-Induced Pore Formation in Lipid Bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. ActaBiomembr. 2018, 1860, 2262–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severin, F.F.; Severina, I.I.; Antonenko, Y.N.; Rokitskaya, T.I.; Cherepanov, D.A.; Mokhova, E.N.; Vyssokikh, M.Y.; Pustovidko, A.V.; Markova, O.V.; Yaguzhinsky, L.S.; et al. Penetrating Cation/fatty Acid Anion Pair as a Mitochondria-Targeted Protonophore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielonka, J.; Joseph, J.; Sikora, A.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Cheng, G.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitochondria-Targeted Triphenylphosphonium-Based Compounds: Syntheses, Mechanisms of Action, and Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10043–10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorre, D.A.; Markova, O.V.; Smirnova, E.A.; Karavaeva, I.E.; Sokolov, S.S.; Severin, F.F. Dodecyltriphenylphosphonium Inhibits Multiple Drug Resistance in the Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Biochem.Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 1481–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, K.V.; Besedina, E.G.; Zinovkin, R.A.; Severin, F.F.; Knorre, D.A. Penetrating Cations Induce Pleiotropic Drug Resistance in Yeast. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, G.; Yuan, L.-X.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Wang, J. Triphenyl Phosphate (TPP) Promotes Hepatocyte Toxicity via Induction of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Inhibition of Autophagy Flux. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 840, 156461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotkovskaya, I.M.; Kholodenko, R.V.; Zelenova, N.A.; Sapozhnikov, A.M.; Mikhalev, I.I.; Molotkovsky, J.G. Gangliosides Induce Cell Apoptosis in the Cytotoxic Line CTLL-2, but Not in the Promyelocyte Leukemia Cell Line HL-60. Membr. Cell Biol. 2000, 13, 811–822. [Google Scholar]

- Doronin, I.I.; Vishnyakova, P.A.; Kholodenko, I.V.; Ponomarev, E.D.; Ryazantsev, D.Y.; Molotkovskaya, I.M.; Kholodenko, R.V. Ganglioside GD2 in Reception and Transduction of Cell Death Signal in Tumor Cells. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galimzyanov, T.R.; Lyushnyak, A.S.; Aleksandrova, V.V.; Shilova, L.A.; Mikhalyov, I.I.; Molotkovskaya, I.M.; Akimov, S.A.; Batishchev, O.V. Line Activity of Ganglioside GM1 Regulates the Raft Size Distribution in a Cholesterol-Dependent Manner. Langmuir 2017, 33, 3517–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, L.J. Rafts Defined: A Report on the Keystone Symposium on Lipid Rafts and Cell Function. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 1597–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasnobaev, V.D.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Akimov, S.A.; Batishchev, O.V. Lysolipids Regulate Raft Size Distribution. Front MolBiosci 2022, 9, 1021321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Toomre, D. Lipid Rafts and Signal Transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. CellBiol. 2000, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Манских, В.Н. Патoмoрфoлoгия лабoратoрнoй мыши рукoвoдствo в трех тoмах; ВАКО, 2018.

- Schibler, J.; Tomanek-Chalkley, A.M.; Reedy, J.L.; Zhan, F.; Spitz, D.R.; Schultz, M.K.; Goel, A. Mitochondrial-Targeted Decyl-Triphenylphosphonium Enhances 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose Mediated Oxidative Stress and Clonogenic Killing of Multiple Myeloma Cells. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Feng, D.; Lv, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. Application Prospects of Triphenylphosphine-Based Mitochondria-Targeted Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C. Medicinal Applications and Molecular Targets of Dequalinium Chloride. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 186, 114467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendling, W.; Weissenbacher, E.R.; Gerber, S.; Prasauskas, V.; Grob, P. Use of Locally Delivered Dequalinium Chloride in the Treatment of Vaginal Infections: A Review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica-Napolitano, J.S.; Aprille, J.R. Delocalized Lipophilic Cations Selectively Target the Mitochondria of Carcinoma Cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 49, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, P.; Galeano, E.; Estañ, M.C.; Gañán-Gómez, I.; Boyano-Adánez, M.D.C.; García-Pérez, A.I. Raf/MEK/ERK Signaling Inhibition Enhances the Ability of Dequalinium to Induce Apoptosis in the Human Leukemic Cell Line K562. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012, 237, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pérez, A.I.; Galeano, E.; Nieto, E.; Estañ, M.C.; Sancho, P. Dequalinium Induces Cytotoxicity in Human Leukemia NB4 Cells by Downregulation of Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathways and Potentiation of Specific Inhibitors of These Pathways. Leuk.Res. 2014, 38, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gañán-Gómez, I.; Estañ-Omaña, M.C.; Sancho, P.; Aller, P.; Boyano-Adánez, M.C. Mechanisms of Resistance to Apoptosis in the Human Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Cell Line NB4. Ann. Hematol. 2015, 94, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider Berlin, K.R.; Ammini, C.V.; Rowe, T.C. Dequalinium Induces a Selective Depletion of Mitochondrial DNA from HeLa Human Cervical Carcinoma Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 245, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.F.; Lin-Shiau, S.Y. Suramin Prevents Cerebellar Granule Cell-Death Induced by Dequalinium. Neurochem.Int. 2001, 38, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Ares, I.; Lopez-Torres, B.; Martínez, M.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.-R.; Wang, X.; Anadón, A.; Martínez, M.-A. Mitochondria as an Important Target of Metformin: The Mechanism of Action, Toxic and Side Effects, and New Therapeutic Applications. Pharmacol.Res. 2022, 177, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Luo, J.; Yu, T.; Zhou, L.; Lv, H.; Shang, P. Anticancer Mechanisms of Metformin: A Review of the Current Evidence. Life Sci. 2020, 254, 117717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Brown, J.; Morel, L. Redox Homeostasis Involvement in the Pharmacological Effects of Metformin in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Antioxid.Redox Signal. 2022, 36, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-S.; Li, M.; Ma, T.; Zong, Y.; Cui, J.; Feng, J.-W.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Lin, S.-Y.; Lin, S.-C. Metformin Activates AMPK through the Lysosomal Pathway. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Singh, N.; Kumar, L. Evaluation of Effects of Metformin in Primary Ovarian Cancer Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 6973–6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, F.; Kong, Q.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Jiang, N.; Yu, C.; Yun, L. Metformin Induces S-Adenosylmethionine Restriction to Extend the Caenorhabditis ElegansHealthspan through H3K4me3 Modifiers. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, C.W.; Nevler, A. PyrviniumPamoate: Past, Present, and Future as an Anti-Cancer Drug. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaam, K.K.; Inaoka, D.K.; Hatta, T.; Tsubokawa, D.; Tsuji, N.; Wada, M.; Saimoto, H.; Kita, K.; Hamano, S. Mitochondria as a Potential Target for the Development of Prophylactic and Therapeutic Drugs against Schistosoma Mansoni Infection. Antimicrob.Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0041821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simm, C.; Weerasinghe, H.; Thomas, D.R.; Harrison, P.F.; Newton, H.J.; Beilharz, T.H.; Traven, A. Disruption of Iron Homeostasis and Mitochondrial Metabolism Are Promising Targets to Inhibit Candida Auris. MicrobiolSpectr 2022, 10, e0010022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zeng, T. Synergistic Effect of PyrviniumPamoate and Azoles Against Aspergillus Fumigatus in Vitro and in Vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 579362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, Y.; Ishii, I.; Hatake, K.; Kasahara, T. PyrviniumPamoate Inhibits Proliferation of Myeloma/erythroleukemia Cells by Suppressing Mitochondrial Respiratory Complex I and STAT3. Cancer Lett. 2012, 319, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Rajoria, P.; Wang, C. Pyrvinium Selectively Induces Apoptosis of Lymphoma Cells through Impairing Mitochondrial Functions and JAK2/STAT5. Biochem.Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Cheong, J.K.; Ang, S.H.; Teo, B.; Xu, P.; Asari, K.; Sun, W.T.; Than, H.; Bunte, R.M.; Virshup, D.M.; et al. Pyrvinium Selectively Targets Blast Phase-Chronic Myeloid Leukemia through Inhibition of Mitochondrial Respiration. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 33769–33780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomitsuka, E.; Kita, K.; Esumi, H. An Anticancer Agent, PyrviniumPamoate Inhibits the NADH-Fumarate Reductase System--a Unique Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism in Tumour Microenvironments. J. Biochem. 2012, 152, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.W.; McCarthy, G.A.; Nerwal, T.; Nevler, A.; DuHadaway, J.B.; McCoy, M.D.; Jiang, W.; Brown, S.Z.; Goetz, A.; Jain, A.; et al. The FDA-Approved Anthelmintic PyrviniumPamoate Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Cells in Nutrient-Depleted Conditions by Targeting the Mitochondria. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 2166–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falabella, M.; Fernandez, R.J.; Johnson, F.B.; Kaufman, B.A. Potential Roles for G-Quadruplexes in Mitochondria. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 2918–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falabella, M.; Kolesar, J.E.; Wallace, C.; de Jesus, D.; Sun, L.; Taguchi, Y.V.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Xiang, I.M.; Alder, J.K.; et al. G-Quadruplex Dynamics Contribute to Regulation of Mitochondrial Gene Expression. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J. Pyrvinium Sensitizes Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Response to Chemotherapy Via Casein Kinase 1α-Dependent Inhibition of Wnt/β-Catenin. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 355, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, B.; Astudillo, L.; Deutscher, M.P.; Cobb, M.H.; Capobianco, A.J.; Lee, E.; Robbins, D.J. The CK1α Activator Pyrvinium Enhances the Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km) of CK1α. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 5102–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, P.; Ke, S.; Yang, L.; Shen, Y. Casein Kinase 1α-Dependent Inhibition of Wnt/β-Catenin Selectively Targets Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma and Increases Chemosensitivity. Anticancer Drugs 2019, 30, e0747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Burkhart, R.A.; Beeharry, N.; Bhattacharjee, V.; Londin, E.R.; Cozzitorto, J.A.; Romeo, C.; Jimbo, M.; Norris, Z.A.; Yeo, C.J.; et al. HuRPosttranscriptionally Regulates WEE1: Implications for the DNA Damage Response in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, F.F.; Jimbo, M.; Wulfkuhle, J.; Gallagher, I.; Deng, J.; Enyenihi, L.; Meisner-Kober, N.; Londin, E.; Rigoutsos, I.; Sawicki, J.A.; et al. The mRNA-Binding Protein HuR Promotes Hypoxia-Induced Chemoresistance through Posttranscriptional Regulation of the Proto-Oncogene PIM1 in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2529–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosu, T.; Ohga, N.; Hida, Y.; Maishi, N.; Akiyama, K.; Kakuguchi, W.; Kuroshima, T.; Kondo, M.; Akino, T.; Totsuka, Y.; et al. HuR Keeps an Angiogenic Switch on by Stabilising mRNA of VEGF and COX-2 in Tumour Endothelium. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.O.; Bolton, E.C.; Huang, Y.; Feau, C.; Guy, R.K.; Yamamoto, K.R.; Hann, B.; Diamond, M.I. Non-Competitive Androgen Receptor Inhibition in Vitro and in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 7233–7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Tew, B.Y.; Lim, M.; Stankavich, B.; He, M.; Pufall, M.; Hu, W.; Chen, Y.; Jones, J.O. Mechanistic Investigation of the Androgen Receptor DNA-Binding Domain Inhibitor Pyrvinium. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Otto-Duessel, M.; He, M.; Su, L.; Nguyen, D.; Chin, E.; Alliston, T.; Jones, J.O. Ligand-Independent and Tissue-Selective Androgen Receptor Inhibition by Pyrvinium. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulistina, D.R.; Martini, S. The Effect of Rhodamine B on the Cerebellum and Brainstem Tissue of RattusNorvegicus. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.; Sharma, S.; Bhatt, U.; Soni, V. Toxic Effects of Rhodamine B on Antioxidant System and Photosynthesis of HydrillaVerticillata. Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters 2022, 3, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampidis, T.J.; Bernal, S.D.; Summerhayes, I.C.; Chen, L.B. Selective Toxicity of Rhodamine 123 in Carcinoma Cells in Vitro. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 716–720. [Google Scholar]

- Lampidis, T.J.; Hasin, Y.; Weiss, M.J.; Chen, L.B. Selective Killing of Carcinoma Cells “in Vitro” by Lipophilic-Cationic Compounds: A Cellular Basis. Biomed.Pharmacother. 1985, 39, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeller, T.; Latz-Brüning, B.; Wink, M. Biochemical Activities of Berberine, Palmatine and Sanguinarine Mediating Chemical Defence against Microorganisms and Herbivores. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Song, J.; Zhong, L.; Liao, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, X. Palmatine: A Review of Its Pharmacology, Toxicity and Pharmacokinetics. Biochimie 2019, 162, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sharma, B. Toxicological Effects of Berberine and Sanguinarine. Front MolBiosci 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, H.; Guo, H.; Xiong, C.; Xie, K.; Zhang, X.; Su, S. Protective Effect of Berberine on Doxorubicin-induced Acute Hepatorenal Toxicity in Rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 3953–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanein, P.; Ghafari-Vahed, M.; Khodadadi, I. Effects of Isoquinoline Alkaloid Berberine on Lipid Peroxidation, Antioxidant Defense System, and Liver Damage Induced by Lead Acetate in Rats. Redox Rep. 2017, 22, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Dev, G.; Tyagi, A.K.; Goomber, S.; Jain, G.V. Argemone Mexicana Poisoning: Autopsy Findings of Two Cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 2001, 115, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, H.; Xiang, C.; Fan, X.-Y.; Yang, L.-Y.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, F.-L.; Liu, Y. Uncoupling Effect of F16 Is Responsible for Its Mitochondrial Toxicity and Anticancer Activity. Toxicol.Sci. 2018, 161, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gureev, A.P.; Shaforostova, E.A.; Laver, D.A.; Khorolskaya, V.G.; Syromyatnikov, M.Y.; Popov, V.N. Methylene Blue Elicits Non-Genotoxic H2O2 Production and Protects Brain Mitochondria from Rotenone Toxicity. J. Appl. Biomed. 2019, 17, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchala, D.; Bhatt, L.K.; Pethe, P.; Shelat, R.; Kulkarni, Y.A. Anticancer Activity of Methylene Blue via Inhibition of Heat Shock Protein 70. Biomed.Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, A.; Jia, D.; Bhatt, V.; Akel, M.; Roberge, J.; Guo, J.Y.; Langenfeld, J. Ym155 Localizes to the Mitochondria Leading to Mitochondria Dysfunction and Activation of AMPK That Inhibits BMP Signaling in Lung Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.B. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Living Cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1988, 4, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wong, J.R.; Song, K.; Hu, J.; Garlid, K.D.; Chen, L.B. AA1, a Newly Synthesized Monovalent Lipophilic Cation, Expresses Potent in Vivo Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Modica-Napolitano, J.S.; Koya, K.; Weisberg, E.; Brunelli, B.T.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.B. Selective Damage to Carcinoma Mitochondria by the Rhodacyanine MKT-077. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 544–550. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M.J.; Wong, J.R.; Ha, C.S.; Bleday, R.; Salem, R.R.; Steele, G.D., Jr.; Chen, L.B. Dequalinium, a Topical Antimicrobial Agent, Displays Anticarcinoma Activity Based on Selective Mitochondrial Accumulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987, 84, 5444–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantin, V.R.; Berardi, M.J.; Scorrano, L.; Korsmeyer, S.J.; Leder, P. A Novel Mitochondriotoxic Small Molecule That Selectively Inhibits Tumor Cell Growth. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmitzer, B.; Heftberger, P.; Rappolt, M.; Pabst, G. Monolayer Spontaneous Curvature of Raft-Forming Membrane Lipids. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 10877–10884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhelev, D.V.; Needham, D. Tension-Stabilized Pores in Giant Vesicles: Determination of Pore Size and Pore Line Tension. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1993, 1147, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.; Zimmerberg, J.; Pastor, R.W. Initiation and Evolution of Pores Formed by Influenza Fusion Peptides Probed by Lysolipid Inclusion. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 1018–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Munguía, I.; Volynsky, P.E.; Batishchev, O.V.; Akimov, S.A.; Korshunova, G.A.; Smirnova, E.A.; Knorre, D.A.; Sokolov, S.S.; Severin, F.F. Effects of Sterols on the Interaction of SDS, Benzalkonium Chloride, and A Novel Compound, Kor105, with Membranes. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, C.-H.; Mazat, J.P.; Guerin, B. The Role of Adenine Nucleotide Translocation in the Energization of the Inner Membrane of Mitochondria Isolated from ϱ+ and ϱo Strains of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Biochem.Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985, 132, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, R.; Johnson, E.; Byrne, F.L. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Mitochondrial Uncouplers in Cancer. MolMetab 2021, 51, 101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorre, D.A.; Besedina, E.; Karavaeva, I.E.; Smirnova, E.A.; Markova, O.V.; Severin, F.F. Alkylrhodamines Enhance the Toxicity of Clotrimazole and Benzalkonium Chloride by Interfering with Yeast Pleiotropic ABC-Transporters. FEMS YeastRes. 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).