Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Type and treatment of lung cancer

1.2. Tumor microenvironment and content: their contribution to NSCLC metastasis

2. Basic properties of cytokines

| Cytokine | Primary Cell Source | Primary Target Cell | Biological Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1 | Monocytes Macrophages Fibroblasts Epithelial cells Endothelial cells Astrocytes |

T cells B cells Endothelial cells Hypothalamus Liver |

Co-stimulation Cell activation Inflammation Fever Acute phase reactant |

| IL-2 | T cells NK cells |

T cells NK cells B cells Monocytes |

Cell growth Cell activation |

| IL-3 | T cells | Bone marrow progenitor cells | Cell growth and cell differentiation |

| IL-4 | T cells | T cells B cells |

Th2 differentiation Cell growth Cell activation IgE isotype switching |

| IL-5 | T cells | B cells Eosinophils |

Cell growth Cell activation |

| IL-6 | T cells Macrophages Fibroblasts |

T cells B cells Liver |

Co-stimulation Cell growth Cell activation Acute phase reactant |

| IL-7 | Fibroblasts Bone marrow stromal cells |

Immature lymphoid progenitors | T cell survival, proliferation, homeostasis B cell development |

| IL-8 | Macrophages Epithelial cells Platelets |

Neutrophils | Activation Chemotaxis |

| IL-10 | Th2 T cells | Macrophages T cells |

Inhibits antigen-presenting cells Inhibits cytokine production |

| IL-12 | Macrophages NK cells |

T cells | Th1 differentiation |

| IL-15 | Monocytes | T cells NK cells |

Cell growth Cell activation NK cell development Blocks apoptosis |

| IL-18 | Macrophages | T cells NK cells B cells |

Cell growth Cell activation Inflammation |

| IL-21 | CD4+ T cells NKT cells |

NK cells T cells B cells |

Cell growth/ activation Control of allergic responses and viral infections |

| IL-23 | Antigen-presenting cells | T cells NK cells DC |

Chronic inflammation Promotes Th17 cells |

| GM-CSF | Fibroblasts Mast cells T cells Macrophages Endothelial cells |

DC Macrophages NKT cells Bone marrow progenitor cells |

T cell homeostasis Promotes antigen presentation Hematopoietic cell growth factor |

| IFN-α | Plasmacytoid DC NK cells T cells B cells Macrophages Fibroblasts Endothelial cells Osteoblasts |

Macrophages NK cells |

Anti-viral Enhances MHC expression |

| IFN-γ | T cells NK cells NKT cells |

Monocytes Macrophages Endothelial Cells Tissue cells |

Cell growth/ activation Enhances MHC expression |

| TGF-β | T cells Macrophages |

T cells | Inhibits cell growth/activation |

| TNF- α | Macrophages T cells |

T cells B cells Endothelial cells Hypothalamus Liver |

Co-stimulation Cell activation Inflammation Fever Acute phase reactant |

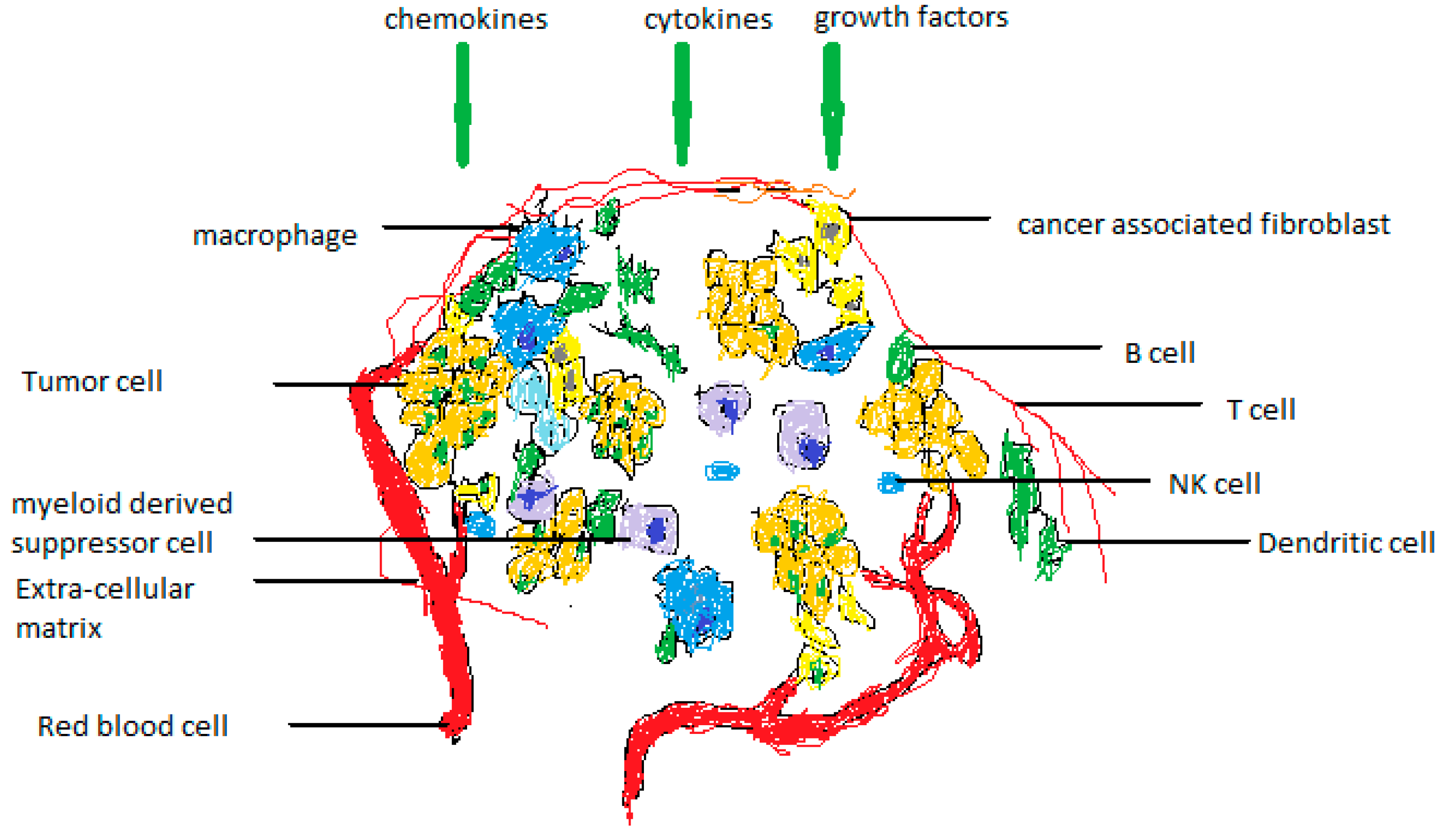

| Cell type | Function in TME |

|---|---|

| Tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) | TAMs exhibit the M2 macrophage phenotype, which includes protumorigenic characteristics, anti-inflammatory properties, and Th2 cytokine secretion. Help cancer cells invade secondary areas and promote angiogenesis. |

| Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) | Stromal cell populations that are active support the desmoplastic tumor microenvironment. By releasing cytokines, one can encourage angiogenesis and control tumor-promoting inflammation. |

| CD4+ Th cells | Th1 and Th2 lineages have been divided. Th1 secretes cytokines that are both proinflammatory and antitumorigenic, whereas Th2 secretes cytokines that are both proinflammatory and tumorigenic. |

| CD8+ Tc cells | Adaptive immune system effector cells that recognize and kill tumor cells by perforin-granzyme-mediated apoptosis. |

| Mast cells (MCs) | innate and adaptive immune responses to be produced and maintained. Release substances that encourage endothelial cell development to aid tumor cell angiogenesis. |

| B-cells | Modulators of humoral immunity and secrete cytokines. Alter Th1:Th2 ratio. |

| Natural killer (NK) cells | Without antigen presentation, cytotoxic lymphocytes obliterate stressed cells. Through "missing self" activation and "stress-induced" activation, detect and destroy tumor cells. |

| Dendritic cells (DCs) | Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that control the immune system's adaptive response. They increase vascularization in the TME to encourage angiogenesis. |

| Neutrophils | N1-type cells are pro-inflammatory, anti-tumorigenic, and release Th1 cytokines. |

2.1. Classification of cytokines and their receptors

| Receptor Family | Ligands | Structure and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Type I Cytokine Receptors | IL-2 IL-3 Il-4 IL-5 IL-6 IL-7 IL-9 IL-11 IL-12 IL-13 IL-15 IL-21 IL-23 IL-27 Erythropoietin GM-CSF G-CSF Growth hormone Prolactin Oncostatin M Leukemia inhibitory factor |

Composed of multimeric chains. Signals through JAK-STAT pathway using common signaling chain. Contains cytokine binding chains. |

| Type II Cytokine Receptors | IFN-α/β IFN-γ IL-10 IL-20 IL-22 IL-28 |

Immunoglobulin-like domains. Uses heterodimer and multimeric chains. Signals through JAK-STAT. |

| Immunoglobulin Superfamily Receptors | IL-1 CSF1 c-kit IL-18 |

Shares homology with immunoglobulin structures. |

| IL-17 Receptor | IL-17 IL-17B IL-17C IL-17D IL-17E IL-17F |

|

| G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCR) | IL-8 CC chemokines CXC chemokine |

Functions to mediate cell activation and migration. |

| TGF-β receptors 1/2 | TGF-β | |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors (TNFR) | CD27 CD30 CD40 CD120 Lymphotoxin-β |

Functions as co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors. |

2.1.1. Type I cytokine receptors

2.1.2. Type II cytokine receptors

2.1.3. Immunoglobulin superfamily receptors

3. The role of cytokines in immunotherapy and cancer

4. Conclusions and future directions

Author’s contribution

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pascal Bezel, Alan Valaperti, Urs Steiner, Dieter Scholtze, Stephan Wieser, Maya Vonow-Eisenring, Andrea Widmer, Benedikt Kowalski, Malcolm Kohler & Daniel P. Franzen. Evaluation of cytokines in the tumor microenvironment of lung cancer using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 1867–1876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tianxia Lan, Li Chen,and Xiawei Wei. Inflammatory Cytokines in Cancer: Comprehensive Understanding and Clinical Progress in Gene Therapy. Cells 2021, 10, 100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliana B. Schilsky, Ai Ni, Linda Ahn, Sutirtha Datta, William D. Travis,c,d Mark G Kris, Jamie E Chaft, Natasha Rekhtman, and Matthew D. Hellmann. Prognostic impact of TTF-1 expression in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas. Lung Cancer 2017, 108, 205–211. [CrossRef]

- N H C Au, A M Gown, M Cheang, D Huntsman, E Yorida, W M Elliott, J Flint, J English, C B Gilks, H L Grimes. P63 expression in lung carcinoma: A tissue microarray study of 408 cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2004, 12, 240–247. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F. Pasini, M.A. Bassetto, R. Sabbioni, G.L. Cetto, F. Scognammiglio, G. Pizzolo. 1187 Soluble CD30 (SCD30) serum levels in patients with embrional carcinoma (EC) or mixed germ cell tumors (GCT) with embrional component. Eur. J. Cancer 1995, 31 (Supplement 6), S248. [CrossRef]

- Purdue, M.P.; Lan, Q.; Langseth, H.; Grimsrud, T.K.; Hildesheim, A.; Rothman, N. Prediagnostic serum sCD27 and sCD30 in serial samples and risks of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 146, 3312–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn I. Levin, Elizabeth C. Breen, Brenda M. Birmann, Julie L. Batista, Larry I. Magpantay, Yuanzhang Li, Richard F. Ambinder, Nancy E. Mueller, Otoniel Martinez-Maza. Elevated Serum Levels of sCD30 and IL6 and Detectable IL10 Precede Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma Diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2017, 26, 1114–1123. [CrossRef]

- John Wiley and Sons. Soluble B-cell activation marker of sCD27 and sCD30 and future risk of B-cell lymphomas: A nested case-control study and meta-analyses. 2016, 138, 2357–2367. [CrossRef]

- Lococo, F.; Paci, M.; Rapicetta, C.; Rossi, T.; Sancisi, V.; Braglia, L.; Cavuto, S.; Bisagni, A.; Bongarzone, I.; Noonan, D.M.; et al. Preliminary Evidence on the Diagnostic and Molecular Role of Circulating Soluble EGFR in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 19612–19630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano Provencio, Manuel Cobo, Delvys Rodriguez-Abreu, Virginia Calvo, Enric Carcereny, Alexandra Cantero, Reyes Bernabé, Gretel Benitez, Rafael López Castro, Bartomeu Massutí, Edel del Barco, Rosario García Campelo, Maria Guirado, Carlos Camps, Ana Laura Ortega, Jose Luis González Larriba, Alfredo Sánchez, Joaquín Casal, M. Angeles Sala, Oscar Juan-Vidal, Joaquim Bosch-Barrera, Juana Oramas, Manuel Dómine, Jose Manuel Trigo, …Maria Torrente. Determination of essential biomarkers in lung cancer: A real-world data study in Spain with demographic, clinical, epidemiological and pathological characteristics. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 732. [Google Scholar]

- T. Yamashita, H. Kamada, S. Kanasaki, Y. Maeda, K. Nagano, Y. Abe, M. Inoue1, Y. Yoshioka, Y. Tsutsumi, S. Katayama, M. Inoue, S. Tsunoda. Epidermal growth factor receptor localized to exosome membranes as a possible biomarker for lung cancer diagnosis. April 26, 2013. Shin-ichi Tsunoda, Ph.D, Laboratory of Biopharmaceutical Research, National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, 7-6-8 Saito-Asagi, Ibaraki, Osaka 567-0085, Japan. 26 April.

- Thomas Jostock, JuÈ rgen MuÈ llberg, Suat OÈ zbek, Raja Atreya, Guido Blinn, Nicole Voltz, Martina Fischer, Markus F. Neurath and Stefan Rose-John. Soluble gp130 is the natural inhibitor of soluble interleukin-6 receptor transsignaling responses. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, E.; Kuehn, J. Measurements of IL-6, soluble IL-6 receptor and soluble gp130 in sera of B-cell lymphoma patients. Does Viscum album treatment affect these parameters? BioMedicine 2002, 56, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Wang, H.; Shen, G.; Lin, D.; Lin, Y.; Ye, N.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Deng, C.; Meng, C. Recombinant soluble gp130 protein reduces DEN-induced primary hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachel Bolanos, Otoniel Martinez-Maza, Zuo-Feng Zhang, Shehnaz Hussain, Mary Sehl, Janet S. Sinsheimer, Gypsyarn D’Souza, Frank Jenkins, Steven Wolinsky, and Roger Detels. Decreased levels of the serum inflammatory biomarkers, sGP130, IL-6, sCRP and BAFF, are associated with increased likelihood of AIDS related Kaposi’s sarcoma in men who have sex with men. Cancer Res Front. 2018, 4, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Z.; Grote, D.M.; Ziesmer, S.C.; Manske, M.K.; Witzig, T.E.; Novak, A.J.; Ansell, S.M. Soluble IL-2Rα facilitates IL-2–mediated immune responses and predicts reduced survival in follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2011, 118, 2809–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, K.; Horita, S.; Maejima, Y.; Takenoshita, S.; Shimomura, K. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor as a predictive and prognostic marker for patients with familial breast cancer. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, E.; Balcerska, A. Serum soluble interleukin 2 receptor α in human cancer of adults and children: A review. Biomarkers 2008, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang-Shun Wang; Kuan-Chih Chow; Wing-Yin Li; Chia-Chuan Liu; Yu-Chung Wu; Min-Hsiung Huang. Clinical Significance of Serum Soluble Interleukin 2 Receptor-α in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2000, 6, 1445–1451.

- Chalaris, A.; Garbers, C.; Rabe, B.; Rose-John, S.; Scheller, J. The soluble Interleukin 6 receptor: Generation and role in inflammation and cancer. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 90, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, Y.; Miki, C.; Toiyama, Y.; Yasuda, H.; Yokoe, T.; Saigusa, S.; Hiro, J.; Tanaka, K.; Inoue, Y.; Kusunoki, M. Loss of tumoral expression of soluble IL-6 receptor is associated with disease progression in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, A.; Sawada, K.; Kinose, Y.; Ohyagi-Hara, C.; Nakatsuka, E.; Makino, H.; Ogura, T.; Mizuno, T.; Suzuki, N.; Morii, E.; et al. Interleukin 6 Receptor Is an Independent Prognostic Factor and a Potential Therapeutic Target of Ovarian Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petra Tesarová 1, Marta Kalousová, Marie Jáchymová, Oto Mestek, Lubos Petruzelka, Tomás Zima. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)--soluble form (sRAGE) and gene polymorphisms in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2007, 25, 720–725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvani, V.; Hartman, K.P.; Rupreht, R.R.; Novaković, S.; Štabuc, B.; Ocvirk, J.; Menart, V.; Porekar, V.G.; Štalc, A.; Rožman, P.; et al. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I (sTNFRI) as a prognostic factor in melanoma patients in Slovene population. 2000, 440 (5 Suppl), R061–R063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selinsky, C.L.; Howell, M.D. Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Type I Enhances Tumor Development and Persistence in Vivo. Cell. Immunol. 2000, 200, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loa, C.C.; Yan, W.; Zhou, J.; Wheeler, S.; Zhang, H.; Zondlo, S.; Chen, L. Abstract 4588: GLP validiation for quantitative determination of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and II (sTNFRI and sTNFRII) in human serum utilizing a highly sensitive ELISA. Cancer Res 2010, 70 (8_Supplement), 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .

- Fuqian Yang Zhonghua Zhao Nana Zhao. Clinical implications of tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 in breast cancer. 2017, 2393–2398.

- Shiels, M.S.; Katki, H.A.; Hildesheim, A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Engels, E.A.; Williams, M.; Kemp, T.J.; Caporaso, N.E.; Pinto, L.A.; Chaturvedi, A.K. Circulating Inflammation Markers, Risk of Lung Cancer, and Utility for Risk Stratification. 2015, djv199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastard, J.-P.; Fellahi, S.; Audureau, É.; Layese, R.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Cagnot, C.; Mahuas-Bourcier, V.; Sutton, A.; Ziol, M.; Capeau, J.; et al. Elevated adiponectin and sTNFRII serum levels can predict progression to hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with compensated HCV1 cirrhosis. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2018, 29, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.T.H.; Stefanini, M.O.; Mac Gabhann, F.; Kontos, C.D.; Annex, B.H.; Popel, A.S. A systems biology perspective on sVEGFR1: Its biological function, pathogenic role and therapeutic use. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 528–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masakazu Toi, Hiroko Bando, Taeko Ogawa, Mariko Muta, Carsten Hornig, Herbert A Weich. Significance of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/soluble VEGF receptor-1 relationship in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002, 98, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaztepe, A.; Ulukaya, E.; Zik, B.; Yagci, A.; Sevimli, A.; Yilmaz, M.; Erdogan, B.B.; Koc, M.; Akgoz, S.; Karadag, M.; et al. Soluble Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1) is Decreased in Lung Cancer Patients Showing Progression: A Pilot Study. 2009, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamszus, K.; Ulbricht, U.; Matschke, J.; A Brockmann, M.; Fillbrandt, R.; Westphal, M. Levels of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 1 in astrocytic tumors and its relation to malignancy, vascularity, and VEGF-A. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harris, H.; Wolk, A.; Larsson, A.; Vasson, M.-P.; Basu, S. Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 2 (sVEGFR-2) and 3 (sVEGFR-3) and breast cancer risk in the Swedish Mammography Cohort. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 2016, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebos, J.M.; Lee, C.R.; Bogdanovic, E.; Alami, J.; Van Slyke, P.; Francia, G.; Xu, P.; Mutsaers, A.J.; Dumont, D.J.; Kerbel, R.S. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor–Mediated Decrease in Plasma Soluble Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 Levels as a Surrogate Biomarker for Tumor Growth. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanefendt, F.; Lindauer, A.; Mross, K.; Fuhr, U.; Jaehde, U. Determination of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (sVEGFR-3) in plasma as pharmacodynamic biomarker. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 70, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Shibata, E.; Tanaka, Y.; Shiraoka, C.; Kondo, Y. Soluble Vegfr3 gene therapy suppresses multi-organ metastasis in a mouse mammary cancer model. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2837–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Tiem, M.; Watkins, R.; Cho, Y.K.; Wang, Y.; Olsen, T.; Uehara, H.; Mamalis, C.; Luo, L.; Oakey, Z.; et al. Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 is essential for corneal alymphaticity. Blood 2013, 121, 4242–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, J.; Baselga, J. The EGF receptor family as targets for cancer therapy. Oncogene 2000, 19, 6550–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed R Akl, Poonam Nagpal, Nehad M Ayoub, Betty Tai, Sathyen A Prabhu, Catherine M Capac, Matthew Gliksman, Andre Goy, K Stephen Suh.

- Mohamed R Akl, Poonam Nagpal, Nehad M Ayoub, Betty Tai, Sathyen A Prabhu, Catherine M Capac, Matthew Gliksman, Andre Goy, K Stephen Suh. Molecular and clinical significance of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2 /bFGF) in malignancies of solid and hematological cancers for personalized therapies. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 44735–44762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, H.; Li, L. Function of fibroblast growth factor 2 in gastric cancer occurrence and prognosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 21, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick Wågsäter, Sture Löfgren, Anders Hugander, Olaf Dienus & Jan Dimberg. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter and protein expression of the chemokine Eotaxin-1 in colorectal cancer patients. 84 (2007).

- Rusch, V.; Klimstra, D.; Venkatraman, E.; Pisters, P.W.; Langenfeld, J.; Dmitrovsky, E. Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligand transforming growth factor alpha is frequent in resectable non-small cell lung cancer but does not predict tumor progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 1997, 3, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Ciardiello, N. Kim, M. L. McGeady, D. S. Liscia, T. Saeki, C. Bianco & D. S. Salomon. Expression of transforming growth factor alpha (TGFa) in breast cancer. Anals of Oncology 1991, 2, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, X. The role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in breast cancer development: A review. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 2019–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouchemore, K.A.; Anderson, R.L. Immunomodulatory effects of G-CSF in cancer: Therapeutic implications. Semin. Immunol. 2021, 54, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.T.; Khan, H.; Ahmad, A.; Weston, L.L.; Nofchissey, R.A.; Pinchuk, I.V.; Beswick, E.J. G-CSF and G-CSFR are highly expressed in human gastric and colon cancers and promote carcinoma cell proliferation and migration. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohri, N.; Halmos, B.; Garg, M.; Levsky, J.M.; Cheng, H.; Gucalp, R.A.; Bodner, W.R.; Kabarriti, R.; Berkowitz, A.; Yellin, M.J.; et al. FLT3 ligand (CDX-301) and stereotactic radiotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38 (15_suppl), 9618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drings, P.; Fischer, J.R. Biology and clinical use of GM-CSF in lung cancer. Lung 1990, 168, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.-S. Stimulatory versus suppressive effects of GM-CSF on tumor progression in multiple cancer types. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Q.-X.; Wang, F.; Guo, Z.-X.; Hu, Y.; An, S.-N.; Luo, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S.-C.; Huang, H.-Q.; Fu, L.-W. GM-CSF mediates immune evasion via upregulation of PD-L1 expression in extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Simińska, D.; Kojder, K.; Grochans, S.; Gutowska, I.; Chlubek, D.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. Fractalkine/CX3CL1 in Neoplastic Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, I.; Erreni, M.; van Brakel, M.; Debets, R.; Allavena, P. Enhanced recruitment of genetically modified CX3CR1-positive human T cells into Fractalkine/CX3CL1 expressing tumors: Importance of the chemokine gradient. J. Immunother. Cancer 2016, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liang, Y.; Chan, Q.; Jiang, L.; Dong, J. CX3CL1 promotes lung cancer cell migration and invasion via the Src/focal adhesion kinase signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Wang, H.; Huang, D.; Wu, Y.; Ding, W.; Zhou, Q.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, N.; Na, R.; Xu, K. The Clinical Implications and Molecular Mechanism of CX3CL1 Expression in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 752860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erreni, M.; Siddiqui, I.; Marelli, G.; Grizzi, F.; Bianchi, P.; Morone, D.; Marchesi, F.; Celesti, G.; Pesce, S.; Doni, A.; et al. The Fractalkine-Receptor Axis Improves Human Colorectal Cancer Prognosis by Limiting Tumor Metastatic Dissemination. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.K.; Ko, D.W.; Park, J.; Kim, I.S.; Doo, S.H.; Yoon, C.Y.; Park, H.; Lee, W.K.; Kim, D.S.; Jeong, S.J.; et al. Alteration of Antithrombin III and D-dimer Levels in Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Korean J. Urol. 2010, 51, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polansky, M.; Varon, J.; Hoots, W. Use of antithrombin III in cancer patients with sepsis complicated with disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Crit. Care 1998, 2, P024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.; Pellegrini, S.; Uzé, G. IFNA2: The prototypic human alpha interferon. Gene 2015, 567, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fimmel, S.; Devermann, L.; Herrmann, A.; Zouboulis, C. GRO-alpha: A Potential Marker for Cancer and Aging Silenced by RNA Interference. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1119, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaxia Man, Xiaolin Yang, Zhentong Wei, Yuying Tan, Wanying Li, Hongjuan Jin & Baogang Wang. High expression level of CXCL1/GROα is linked to advanced stage and worse survival in uterine cervical cancer and facilitates tumor cell malignant processes. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 712. [Google Scholar]

- Deok-Soo Son, Angelika K. Parl, Valerie Montgomery Rice & Dineo Khabele. Keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC)/human growthregulated oncogene (GRO) chemokines and proinflammatory chemokine networks in mouse and human ovarian epithelial cancer cells. Deok-Soo Son, Angelika K. Parl, Valerie Montgomery Rice & Dineo Khabele (2007) Keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC)/human growth-regulated oncogene (GRO) chemokines and pro-inflammatory chemokine networks in mouse and human ovarian epithelial cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 1308–1318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Jablonska, J Jablonski, L Piotrowski, Z Grabowska. IL-1beta, IL-1Ra and sIL-1RII in the culture supernatants of PMN and PBMC and the serum levels in patients with inflammation and patients with cancer disease of the same location. Immunobiology 2001, 204, 508–516. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.K.; Bae, M.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, D.J.; Chung, K.Y. Preoperative serum CYFRA 21-1 level as a prognostic factor in surgically treated adenocarcinoma of lung. Lung Cancer 2013, 79, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, M.; Huang, H.; Jiang, X.; Gong, K.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, X.; Yang, X. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen elevation in benign lung diseases. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, H.M.; Tourky, G.F.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Khattab, A.M.; Elmasry, S.A.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Hakami, Z.H.; Alsulimani, A.; Sabatier, J.-M.; et al. The Potential Role of MUC16 (CA125) Biomarker in Lung Cancer: A Magic Biomarker but with Adversity. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Verma, A.K.; Dev, K.; Goyal, Y.; Bhatt, D.; Alsahli, M.A.; Rahmani, A.H.; Almatroudi, A.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Alrumaihi, F.; et al. Role of Cytokines and Chemokines in NSCLC Immune Navigation and Proliferation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5563746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couraud, S.; Zalcman, G.; Milleron, B.; Morin, F.; Souquet, P.-J. Lung cancer in never smokers – A review. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunnissen, E.; Noguchi, M.; Aisner, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Brambilla, E.; Chirieac, L.R.; Chung, J.-H.; Dacic, S.; Geisinger, K.R.; Hirsch, F.R.; et al. Reproducibility of Histopathological Diagnosis in Poorly Differentiated NSCLC: An International Multiobserver Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014, 9, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenfield, S.A.; Wei, E.K.; Rosner, B.A.; Glynn, R.J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A. Burden of smoking on cause-specific mortality: Application to the Nurses' Health Study. Tob. Control. 2010, 19, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Yang, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Han, B. Screening for early stage lung cancer and its correlation with lung nodule detection. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S846–S859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Hua, S. A promising role of interferon regulatory factor 5 as an early warning biomarker for the development of human non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2019, 135, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belderbos, J.; Sonke, J.J. State-of-the-art lung cancer radiation therapy. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2009, 9, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunil, S.G.; Raviraj, R.; Nagarajan, D.; Zhao, W. Radiation-induced lung injury: Impact on macrophage dysregulation and lipid alteration–a review. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology 2019, 41, 370–379. [Google Scholar]

- Tartour, E.; Zitvogel, L. Lung cancer: Potential targets for immunotherapy. Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-S.; Liu, W.; Ly, D.; Xu, H.; Qu, L.; Zhang, L. Tumor-infiltrating B cells: Their role and application in anti-tumor immunity in lung cancer. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 16, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Verma, A.K.; Dev, K.; Goyal, Y.; Bhatt, D.; Alsahli, M.A.; Rahmani, A.H.; Almatroudi, A.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Alrumaihi, F.; et al. Role of Cytokines and Chemokines in NSCLC Immune Navigation and Proliferation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5563746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, H.M.; Radtke, S.; Haan, C.; de Leur, H.S.-V.; Tavernier, J.; Heinrich, P.C.; Behrmann, I. Contributions of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor and Oncostatin M Receptor to Signal Transduction in Heterodimeric Complexes with Glycoprotein 130. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 6651–6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamaki, K.; Miyajima, I.; Kitamura, T.; Miyajima, A. Critical cytoplasmic domains of the common beta subunit of the human GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 receptors for growth signal transduction and tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 3541–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotenko, S.V.; Pestka, S. Jak-Stat signal transduction pathway through the eyes of cytokine class II receptor complexes. Oncogene 2000, 19, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, V.M.; Massara, M.; Capucetti, A.; Bonecchi, R. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: New Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, V.M.; Massara, M.; Capucetti, A.; Bonecchi, R. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: New Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, N. Chemokines and cancer: New immune checkpoints for cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 51, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Livergood, R.S.; Peng, G. The Role and Regulation of Human Th17 Cells in Tumor Immunity. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 182, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, D.J.; Wilson, C. The Interleukin-8 Pathway in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6735–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oft, M. IL-10: Master Switch from Tumor-Promoting Inflammation to Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.C.; Moon, C.; Kemp, B.L.; et al. Lack of interleukin-10 expression could predict poor outcome in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003, 9, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, S.-I.; Shimizu, K.; Shimizu, T.; Lotze, M.T. Interleukin-10 promotes the maintenance of antitumor CD8+ T-cell effector function in situ. Blood 2001, 98, 2143–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziblat, A.; Domaica, C.I.; Spallanzani, R.G.; Iraolagoitia, X.L.R.; Rossi, L.E.; Avila, D.E.; Torres, N.I.; Fuertes, M.B.; Zwirner, N.W. IL-27 stimulates human NK-cell effector functions and primes NK cells for IL-18 responsiveness. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015, 45, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchereau, J.; Pascual, V.; O'Garra, A. From IL-2 to IL-37: The expanding spectrum of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, V.M.; Massara, M.; Capucetti, A.; Bonecchi, R. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: New Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.-Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lei, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.-T. JAK/STAT3 signaling is required for TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.F.; Lee, Y.C.; Lo, S.; et al. A positive feedback loop of IL-17B-IL-17RB activates ERK/β-catenin to promote lung cancer metastasis. Cancer Letters. 2018, 422, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).