Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Manufacturer/LOT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Printer | P30+ (digital light processing) | Straumann, Basel, Switzerland |

|

| Orientation | 0° | ||

| 45° | |||

| 90° | |||

| Cleaning | AUTO | P Wash (isopropanol): pre-cleaning 3:10 min, cleaning 2:20 min, drying 1:30 min |

Straumann, Basel, Switzerland |

| MAN | Pre-/Main-Clean (isopropanol): pre-cleaning 3:00 min, ultrasonic: 2:00 min, air-drying: 1:00 min |

VOCO, Cuxhaven, Germany |

|

| Post polymerization | LED | P Cure: LED, 10 min, vacuum, UV–A: 400 - 315 nm; UV-B 315 - 280 nm, heating |

Straumann, Basel, Switzerland |

| XEN | Otoflash G171: 2 x 2000 Xenon flashes, 280-700 nm, maximum between 400 - 500 nm |

NK-OPTIK, Baierbrunn, Germany | |

|

Materials |

M1 | Luxaprint OrthoPlus: > 90% bisphenol A dimethacrylate, 385/405 nm, flexural strength ≥ 70 MPa, flexural modulus ≥ 1 GPa, Shore D ≥ 60 |

DMG, Hamburg, Germany/LOT 218479 |

| M2 | V-Print Splint: acrylate, Bis-EMA, TEGDMA, hydroxypropyl methacrylate, butylated hydroxytoluene, diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide, 385 nm, flexural strength 75 MPa, flexural modulus ≥ 2.1 GPa, water uptake 27.7 μg/mm3, solubility < 0.1 μg/mm3 |

VOCO, Cuxhaven, Germany/LOT 2023138 |

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Santiago, V.; Winocur, E.; Laat, A. de; Leeuw, R. de; et al. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: Report of a work in progress. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, A.-M.; Hampe, R.; Roos, M.; Lümkemann, N.; Eichberger, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Fracture resistance and 2-body wear of 3-dimensional-printed occlusal devices. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berli, C.; Thieringer, F.M.; Sharma, N.; Müller, J.A.; Dedem, P.; Fischer, J.; Rohr, N. Comparing the mechanical properties of pressed, milled, and 3D-printed resins for occlusal devices. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedem, P.; Türp, J.C. Digital Michigan splint - from intraoral scanning to plasterless manufacturing. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2016, 19, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R.; Wismeijer, D. Effects of build direction on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed complete coverage interim dental restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Reymus, M.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.-H. Three-body wear of 3D printed temporary materials. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedekind, L.; Güth, J.-F.; Schweiger, J.; Kollmuss, M.; Reichl, F.-X.; Edelhoff, D.; Högg, C. Elution behavior of a 3D-printed, milled and conventional resin-based occlusal splint material. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Bowman, J.; White, A.R.; George, R.; Fidan, I. Characterization of the Double Bond Conversion of Acrylic Resins for 3D Printing of Dental Prostheses. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2019, 40, e7–e11. [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Lowery, L.; Gibreel, M.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. Evaluation of the mechanical properties and degree of conversion of 3D printed splint material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 115, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, N.; Wesemann, C.; Spies, B.C.; Beuer, F.; Bumann, A. Dimensional accuracy of extrusion- and photopolymerization-based 3D printers: In vitro study comparing printed casts. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-S.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y.; Seo, D.-G. Effects of Printing Parameters on the Fit of Implant-Supported 3D Printing Resin Prosthetics. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymus, M.; Fabritius, R.; Keßler, A.; Hickel, R.; Edelhoff, D.; Stawarczyk, B. Fracture load of 3D-printed fixed dental prostheses compared with milled and conventionally fabricated ones: the impact of resin material, build direction, post-curing, and artificial aging-an in vitro study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-M.; Park, J.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y. Flexural Strength of 3D-Printing Resin Materials for Provisional Fixed Dental Prostheses. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nold, J.; Wesemann, C.; Rieg, L.; Binder, L.; Witkowski, S.; Spies, B.C.; Kohal, R.J. Does Printing Orientation Matter? In-Vitro Fracture Strength of Temporary Fixed Dental Prostheses after a 1-Year Simulation in the Artificial Mouth. Materials (Basel) 2021, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hada, T.; Kanazawa, M.; Iwaki, M.; Arakida, T.; Soeda, Y.; Katheng, A.; Otake, R.; Minakuchi, S. Effect of Printing Direction on the Accuracy of 3D-Printed Dentures Using Stereolithography Technology. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, R.; Reinhard, H.; Andreas, K. Accuracy of CAD/CAM-fabricated bite splints: milling vs 3D printing. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 4607–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grymak, A.; Aarts, J.M.; Ma, S.; Waddell, J.N.; Choi, J.J.E. Comparison of hardness and polishability of various occlusal splint materials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 115, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puebla, K.; Arcaute, K.; Quintana, R.; Wicker, R.B. Effects of environmental conditions, aging, and build orientations on the mechanical properties of ASTM type I specimens manufactured via stereolithography. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2012, 18, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, P.d.S.; Kogawa, E.M.; Lauris, J.R.P.; Conti, P.C.R. The influence of gender and bruxism on the human maximum bite force. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2006, 14, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishigawa, K.; Bando, E.; Nakano, M. Quantitative study of bite force during sleep associated bruxism. J. Oral Rehabil. 2001, 28, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickl, V.; Strasser, T.; Schmid, A.; Rosentritt, M. Pull-off behavior of hand-cast, thermoformed, milled and 3D printed splints. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosentritt, M.; Behr, M.; Strasser, T.; Schmid, A. Pilot in-vitro study on insertion/removal performance of hand-cast, milled and 3D printed splints. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 121, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DIN EN ISO 20795-1:2013-06, Zahnheilkunde_- Kunststoffe_- Teil_1: Prothesenkunststoffe (ISO_20795-1:2013); Deutsche Fassung EN_ISO_20795-1:2013; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin.

- Lee, H.; Wang, J.; Park, S.-M.; Hong, S.; Kim, N. Analysis of excessive deformation behavior of a PMMA-touch screen panel laminated material in a high temperature condition. Korea-Aust. Rheol. J. 2011, 23, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H.; Chen, Q.; Advincula, R.C. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed polymers. Additive Manufacturing 2018, 20, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohdi, N.; Yang, R.C. Material Anisotropy in Additively Manufactured Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, M.; Ortega, Z.; Hernández, A.; Paz, R.; Ortega, F. Anisotropy of Photopolymer Parts Made by Digital Light Processing. Materials (Basel) 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Yang, Z.; Mongrain, R.; Leask, R.L.; Lachapelle, K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2018, 4, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xepapadeas, A.B.; Koos, B.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J.; Li, P.; Spintzyk, S. Effect of post-rinsing time on the mechanical strength and cytotoxicity of a 3D printed orthodontic splint material. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e314–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, J.; Schweikl, H.; Rosentritt, M. Cytotoxicity of printed resin-based splint materials. J. Dent. 2022, 120, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbauer, U.; Rahiotis, C.; Krämer, N.; Petschelt, A.; Eliades, G. The effect of different light-curing units on fatigue behavior and degree of conversion of a resin composite. Dent. Mater. 2005, 21, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barszczewska-Rybarek, I.M. A Guide through the Dental Dimethacrylate Polymer Network Structural Characterization and Interpretation of Physico-Mechanical Properties. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff, J.; Schmid, A.; Huber, C.; Rosentritt, M. Dynamic fatigue of 3D-printed splint materials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 124, 104885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shim, J.-S.; Lee, D.; Shin, S.-H.; Nam, N.-E.; Park, K.-H.; Shim, J.-S.; Kim, J.-E. Effects of Post-Curing Time on the Mechanical and Color Properties of Three-Dimensional Printed Crown and Bridge Materials. Polymers 2020, 12, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentritt, M.; Krifka, S.; Preis, V.; Strasser, T. Dynamic fatigue of composite CAD/CAM materials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 98, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Ren, L.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, M.; Luo, W.; Zhan, D.; Sano, H.; Fu, J. Evaluation of the Color Stability, Water Sorption, and Solubility of Current Resin Composites. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohbauer, U.; Belli, R.; Ferracane, J.L. Factors involved in mechanical fatigue degradation of dental resin composites. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

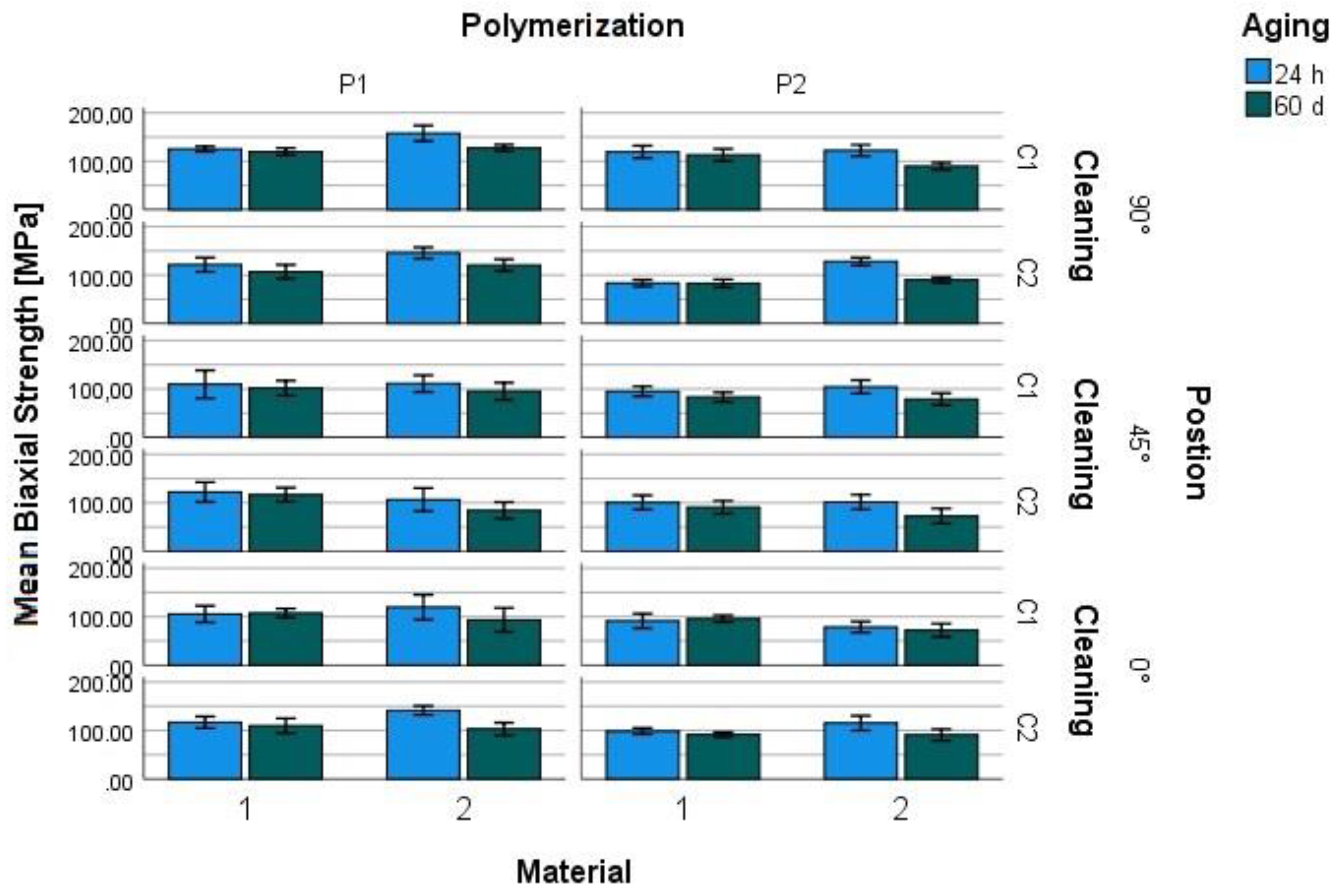

| Orientation to building platform | Material | Cleaning | Post-polymerization | storage time (water 37°C) | BAF | |

| mean | SD | |||||

| 90° | M1 | C1 | P1 | 24 h | 125.2 | 5.3 |

| 60 d | 119.7 | 7.5 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 119.3 | 12.8 | |||

| 60 d | 112.8 | 12.6 | ||||

| C2 | P1 | 24 h | 121.3 | 14.9 | ||

| 60 d | 106.9 | 14.2 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 83.3 | 6.9 | |||

| 60 d | 82.8 | 8.3 | ||||

| M2 | C1 | P1 | 24 h | 157.5 | 16.2 | |

| 60 d | 127.1 | 6.9 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 122.1 | 11.6 | |||

| 60 d | 89.5 | 7.5 | ||||

| C2 | P1 | 24 h | 145.8 | 11.5 | ||

| 60 d | 120.3 | 11.9 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 127.9 | 8.0 | |||

| 60 d | 89.8 | 5.8 | ||||

| 45° | M1 | C1 | P1 | 24 h | 109.6 | 28.8 |

| 60 d | 101.7 | 15.3 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 95.1 | 10.1 | |||

| 60 d | 83.0 | 9.6 | ||||

| C2 | P1 | 24 h | 122.2 | 20.4 | ||

| 60 d | 116.5 | 14.6 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 100.6 | 14.8 | |||

| 60 d | 90.7 | 13.3 | ||||

| M2 | C1 | P1 | 24 h | 111.1 | 17.3 | |

| 60 d | 95.3 | 17.8 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 104.2 | 13.8 | |||

| 60 d | 78.6 | 12.5 | ||||

| C2 | P1 | 24 h | 106.5 | 23.9 | ||

| 60 d | 84.4 | 17.0 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 101.4 | 15.2 | |||

| 60 d | 72.7 | 15.4 | ||||

| 0° | M1 | C1 | P1 | 24 h | 105.4 | 16.9 |

| 60 d | 107.4 | 9.1 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 91.1 | 15.0 | |||

| 60 d | 95.5 | 6.9 | ||||

| C2 | P1 | 24 h | 116.7 | 12.1 | ||

| 60 d | 109.6 | 15.4 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 98.5 | 6.4 | |||

| 60 d | 91.3 | 5.1 | ||||

| M2 | C1 | P1 | 24 h | 119.4 | 25.9 | |

| 60 d | 93.2 | 24.8 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 78.6 | 11.1 | |||

| 60 d | 71.9 | 13.5 | ||||

| C2 | P1 | 24 h | 141.3 | 9.3 | ||

| 60 d | 102.9 | 13.0 | ||||

| P2 | 24 h | 115.2 | 14.9 | |||

| 60 d | 90.9 | 11.7 | ||||

| F | p-Value | |

| material | 2.668 | .103 |

| orientation | 100,342 | <.001 |

| cleaning | .984 | .321 |

| polymerization | 356.934 | <.001 |

| aging | 228.539 | <.001 |

| material * position | 36.020 | <.001 |

| material * cleaning | 8.985 | 0.003 |

| material * polymerization | 2.966 | 0.085 |

| material * aging | 92.072 | <.001 |

| position * cleaning | 46.331 | <.001 |

| position * polymerization | 6.678 | .001 |

| position * aging | 2.904 | .056 |

| cleaning * polymerization | .542 | .462 |

| cleaning * aging | 5.412 | .020 |

| polymerization * aging | .124 | .724 |

| material * position * cleaning | 28.301 | <.001 |

| material * position * polymerization | 10.567 | <.001 |

| material * position * aging | 2.274 | .104 |

| material * cleaning * polymerization | 25.823 | <.001 |

| material * cleaning * aging | .650 | .420 |

| material * polymerization * aging | .026 | .872 |

| position * cleaning * polymerization | 1.688 | .186 |

| position * cleaning * aging | 3.345 | .036 |

| position * polymerization * aging | 4.367 | .013 |

| cleaning * polymerization * aging | .000 | .988 |

| material * position * cleaning * polymerization | 3.557 | .029 |

| material * position * cleaning * aging | .318 | .727 |

| material * position * polymerization * aging | 4.161 | .016 |

| material * cleaning * polymerization * aging | .945 | .331 |

| position * cleaning * polymerization * aging | .222 | .801 |

| material * position * cleaning * polymerization * aging | 1.055 | .349 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).