1. Introduction

The construction of city water supply systems is a very ancient activity; there is manifested culture level and engineering knowledge of early civilizations. A large part of these systems still perfectly functioning continuing to deserve all our admiration. This very intriguing activity offers uncounted examples, but could be mention only the water supply of ancient Rome. It consists of 11 aqueducts carrying more than 13 m3/s of karst spring water to the city of old Rome from a distance of 16 to 91 km (Lombardi and Corrazza 2008). Generally, many cities continue to be supplied by karst springs today in the world and with diverse examples from south-astern Europe, including Albania, as well (Stevanović and Eftimi 2010).

The Illyrians, the ancient people living in the territory of Albania, constructed the first cities during the period IV-III centuries BC and different contemporary technics for that time have been used for water supply (Baçe et al. 1980). The archeological data testify the high level of the ancient intake structures and water supply system of Apolonia, (Ceka 1982), of Durrahy (Durres), Buthrot (Butrinti) and Tepelena (Baçe et al. 1980) some shown in

Figure 1.

Albania's modern cities have no long history; they began to be built in the second half of the 19th century. Their water supply was initially based on the use of water resources inside the settlement’s territories, like natural springs, or groundwater of the intergranular aquifers, captured by big diameters dug wells. There have been special cases, where the population of the cities collected the rain water in “steras” (cisterns), built in house cellars. This experience is characteristic for the city of Gjirokaster in South Albania, located on limestone massif of Gjërë Mountain, where the precipitation disappeared rapidly without creating permanent springs. The first modern water supply systems of Albania’s cities began to be built after 1920. The end of World War II found Albania with seven water supply systems, five recharged by springs and two diverted river waters, with total capacity of 150 l/s. The performed analyses show that, the estimated population served by the water supply in 2010, was 2.65 million people, which represents 80.3% of the total population in the jurisdictional areas of all water utilities in Albania (3.31 million people). Based on the reported data, water supply service coverage was 90.7% in urban areas and 57.0% in rural areas (DoCM No. 643, 2011). The reported water production, on average, is about 300 l/capita/d (290 million m3 per year) and water sales, on average, to be 110 l/capita/d (108 million m3/d). The above figures report that non-revenue water (water not billed together with “illegal”, unregistered connections) represents about 60%-65% of total capacity of the water production.

The topic of water supply of cities consists of two aspects: the first is the capacity and water quality of water supply source, and the second is the managerial level of such systems. In this article we will address only the first aspect. In the analyses, the term “potable” means all water distributed to the consumers through the water works, without distinction between the water for drinking or for other communal and industrial needs.

2. Study Area

Albania's cities are distributed throughout the country, but most of them, and in particular the largest ones, including capital Tirana, are located in the lower western part of the country (

Figure 2).

For the purpose of this article, a high number of the hydrogeological water supply studies performed by Albanian Hydrogeological Service (AHS) is evaluated. Since 1959 the AHS began detailed groundwater investigations of Albania, which focused on the city’s water supply. Such studies were particularly intensified after 1963 when the hydrogeological survey (mapping) of all the country was combined with water supply of the population and of the new industries (Eftimi et al. 2022b). The results of these investigations, performed up to 1990, served for construction of many water systems supplying the settlements. After 1990, but more intensively after 2000, numerous water supply projects for reconstruction of the existing systems have been performed by private companies.

2.1. Hydrogeological Characteristics of Albania

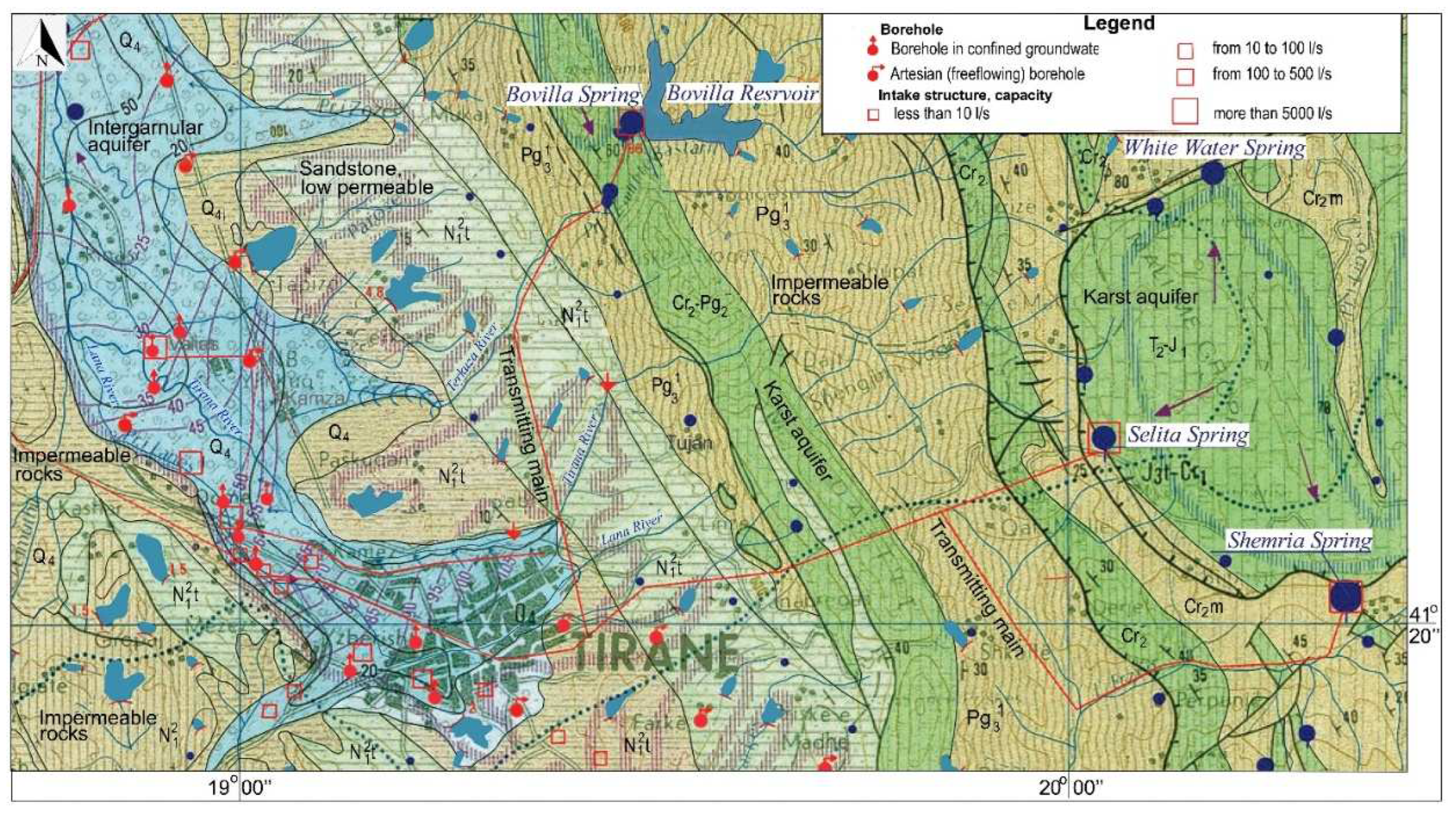

Although geographically a small country, Albania has a great geological variety. Regarding the age, rocks in Albania vary from Ordovician to Quaternary, while, according to their origin they are sedimentary, magmatic and metamorphic (Meço and Aliaj 2000; Xhomo et al. 2002). Due to uneven areal distribution of different rocks over the country’s territory, the hydrogeological characteristics of Albania are highly variable, also (Eftimi 1982, 2010, Eftimi at al. 1985). As shown in

Figure 2, from the hydrogeological point of view, the rocks of Albania are classified into five classes. In general, two classes of rocks differ as abundant aquifers: (a) The porous, intergranular mainly fluvial gravelly aquifers (blue color) exploitable mainly by drilling wells, and (b) the karstic aquifers (dark green color) consisting usually of high elevation carbonate structures recharging strong karst springs. The other fissured-porous aquifers, like sandstone-conglomerate aquifers, and fissured magmatic rocks, are generally considered as moderately to low productive aquifers. The group of rocks, shown on the map with dark brown color (

Figure 2), occupy about 40% of Albania’s territory, represents low productive to very low sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. This fact undoubtedly represents an aggravating factor for the water supply of the settlements, but, in general, of the whole country, also.

Table 1. shows the estimated total natural (renewable) and exploitable groundwater resources

of Albania.

Hydrographic basin of Albania is 43,305 km2, while the country surface is 28,748 km2. Albania is rich in waters as long as the surface flow from the territory of the country of 1245 m3/s is equivalent to 8,600 m3/year per capita (DoCM No 643). The natural groundwater resources of Albania consist of 288 m3/s, while exploitable groundwater resources consist of about 140 m3/s, which in most of the aquifers corresponds to 50% of the total calculated natural groundwater resources. Exception to this rule consists the groundwater resources of the intergranular aquifers, which exploitable resources could be larger than the natural ones as a result of induced infiltration when pumping at the recharge areas. According to an approximate estimation, in Albania, centralized urban and industrial water supply from the groundwater currently accounts for about 14 m3/s, while rural water supply uses to about 2.0 m3/s, amounting to a total of about 14 m3/s. Only Tirana has an additional water supply source of about 1.5-2 m3/s from the surface water of an artificial lake.

2.2. Hydrogeological Characteristics around the Cities s of Albania

According to their type, the water supply sources of the Albanian cities could be summarized into five groups:

Drilling wells in intergranular aquifers;

Karst springs;

Drilling wells in karst aquifers;

Drilling wells and springs in fissured rocks;

Two or more different water supply sources, including surface water.

3. Water Supply from Intergranular Aquifers

The groundwater intake structures in intergranular aquifers consist mainly of pumped water wells, which, according to their total capacity, are classified in three groups; a) less than 100 l/s, b) from 100 to 500 l/s and c) more than 500 l/s (

Figure 2). Only in three cities, namely Shkoder, Durres and Elbasan, the actual pumped capacity is more than 500 l/s, in nine cities the pumped water supply capacity varies from 100 to 500 l/s, and in remaining five cities the pumping capacity is less than 100 l/s. The intergranular gravelly-sandy aquifers of Albania are situated mainly in the western Near-Adriatic plain area of the country, along river valleys, and in few inner intermountain basins (Eftimi at al. 1985). They generally consist of Quaternary fluvial deposits, with maximal thickness about 150-200 m, representing multi-layered gravelly aquifer system.

The techniques of groundwater resource evaluation require an understanding of the concept of groundwater yield. The primary objective of most groundwater studies is the determination of the maximum possible pumping rates that are compatible with the hydrogeological environment from which the water will be taken. The determination of the most suitable place for water supply wells in intergranular aquifers is based on detailed investigations of the aquifer characteristics, which enable to respect some principles, two of which are most important (Nonner 2003): (a) The water supply wells preferably are located as close as possible to the recharge areas (e.g. the riverbed), thus ensuring the sustainability of the groundwater flow, and the possibility to increase the pumping capacity of wells through induced infiltration (Rorabaugh 1956; Walton 1960, Kruseman & De Ridder 1970, Eftimi 1982), and (b) the water wells preferably are placed in areas with the highest aquifer transmissibility, ensuring higher pumping rates of the wells, and consequently, a reduction of their number. This need the yields to be viewed in terms of a balance between the benefits of groundwater pumping and the undesirable changes that will be potentially induced (Freeze & Chery 1979, Bochever 1979).

The successful application of the mentioned principles asks for a thorough hydrogeological knowledge, that is not missing for the intergranular aquifers of Albania. Usually, the aquifer transmissibility varies from about 1000, to over 10,000 m2/day and, accordingly, the specific capacity of the pumped wells varies within 10 to more than 100 l/s/m, while the maximal total capacities of the wells exceed 200 l/s (Lako 1973; Eftimi, 1982, Eftimi and Sara 1922a). For the calculation of the aquifer filtration parameters the Theim-Dupuit’s method is used for steady flow, and different formulas representing the solution of Theis for non-steady flow. In aquifers limited by one or more straight recharge boundaries, different solutions are widely used for the determination of the aquifer hydraulic parameters. (Ferris et al. 1962, Walton 1970, Kruseman & De Ridder 2000)

For a better understanding of the hydrogeology of intergranular aquifer related to the city’s water supply, four problematic examples of groundwaters exploitation in intergranular aquifers of Albania will be discussed below: Mat River Plain, Krasta Vogel Plain, Shkodra Plain and Korça intermountain basin.

Mat River Plain. This Plain is situated south of the homonymous river and the hydrogeological map of this area is shown in

Figure 3. This plain is one of most abundant and heavy pumped intergranular aquifers of Albania. The pumped groundwater is used for the water supply of the cities Durres, Lezhë, Milot, and Laç, and for dozens of villages as well, with a total population of about 350,000 people (

Figure 2). The total surface of the Fushe Kuqe Plain is about 100 km

2 and is filled up by fluvial deposits of the Mat River, which maximum thickness is about 200 m. The transmissivity of gravelly aquifer, in the central area exceeds 4000 m

2/day, and accordingly, the specific capacity of the wells often exceeds 40 l/s/m (Eftimi 1982, 2012).

The recharge of the intergranular aquifer from the Mat River is facilitated both by the very good hydraulic connection of the riverbed deposits with the gravelly aquifer. The most important wellfields in the area are those of Fushe Kuqe, with capacity 720 l/s functioning since 1972, and Fushë Milot, with capacity 625 l/s functioning since 2021 (

Figure 3). Fushe Kuqe wellfield is located at similar distances from the Mat River (recharge area) and the Adriatic Sea (discharge area). Before starting intensive pumping of the groundwater (around 1972), the piezometric level in the area of the wellfield was stabilized about 4-5 above the ground surface, corresponding to an absolute elevation of about 6-7 m. At present, the groundwater level is decreased and in the center of the wellfield is stabilized at absolute elevation around 0.0 m (

Figure 3). This created a threat about the possibility of sea water intrusion into the gravelly aquifer compromising the groundwater quality.

As shown by environmental hydrochemical and isotope investigations, the occurrence of brackish water in the periphery areas are related to the exchange processes between the ion Ca2+ of the groundwater with the Na+ of clay intercalating layers, remnants since the Holocene Sea transgression (Eftimi 1966; 2012, Kumanova et al. 2014). The hydrochemical observations performed by the Albanian Geological Service do not show a current risk of seawater intrusion in the studied aquifer, since the wells close to the shore are still artesian (free-flowing) and the increase of Cl- in groundwater is not significative (Noner 2003). After more than 40 years of groundwater pumping in the Fush Kuqe Wellfield, the Cl and Na contents have not any significant increase; marine water intrusion is thus not yet considered as a concrete problem. create

However, in order not to generate sea water intrusion, the second big wellfield in Fushe Kuqe Plain, that of Fushe Milot, was located near the Mat River recharging the aquifer (Figure.3). It is believed that the short distance to the Mat River, and at the same time the very high values of aquifer hydraulic parameters, will ensure the sustainability of the groundwater flow through induced infiltration. However, near the recharge area there is a constant threat for groundwater contamination by the infiltration into aquifer of polluted waters from the river (Freeze & Cherry 1979, Chiesa G 1994, Nonner 2003).

Among the main pollution sources of the rivers of Albania, untreated urbane sewage waters have to be considered as most problematic (Kumanova etj. 2015). This is testified by the result of non-systematic bacteriological analyses at the Mat River recharge area of the alluvial aquifers. Another serious concern is the intensified quarrying at the river-bed recharge areas (Gelaj etj. 2014, Eftimi 2012).

Beside the decreasing of the aquifer thickness of the gravelly aquifers at the recharge areas, the decrease of aquifer hydraulic pressure, in turn facilitate the of seawater intrusion in the coastal areas. Beside this, quarrying activities are a source of groundwater contamination (Gunn 1993, 2004; Parise 2016) by oil leakage from machineries. The described negative phenomena are very problematic for most important intergranular aquifers of Albania.

Krasta Vogel Plain. Rapid urbanization has a profound effect on groundwater recharge, and a marked impact on groundwater quality (Foster at al. 1999; Suresh 1999). Near the eastern suburbs of the city of Elbasan, in Central Albania (

Figure 2), along the Shkumbin River valley the small Krasta Vogel Plain is filled with high permeability gravel deposits, hydraulically connected with the Shkumbin River (

Figure 4). For the water supply of city of Elbasan three pumped wells, with total capacity 245 l/s, have been drilled near the riverbanks. As a result of uncontrolled urban expansion of Krasta Vogel village, started about 20 years ago, the groundwater pumped by the wells nr. 2 and 3 was contaminated, and new wells have been drilled upstream for the water supply of the city.

Dobraç wellfield. A similar example, at a larger scale, is the Dobraç wellfield, near Shkodra Lake, in North Albania (

Figure 5), initially developed in a peripherical, undeveloped area. Shkodra Plain is filled by an 60-70 m thick intergranular aquifer, covered by a thin grained soil, with thickness of 5-10 m. The groundwater is recharged by the infiltration of the rainfall Shkodra Plain, and moves westward to the discharge area of Shkodra Lake. The aquifer transmissivity in wide areas is higher than 8000 m

2/day, and the capacity of wells is about 100-120 l/s. In Dobraç wellfield, are pumped about 800 l/s for the water supply of Shkodra City, but the groundwater is threatened by infiltration of the untreated sewage water of the new urban area developed in the immediate vicinity to the pumped wells. Actually, two exploitable wells, the closest to the new urban area, each with capacity 100 l/s, are polluted and abandoned (

Figure 5), and seems the same will happen with the other pumping wells.

Korça intermountain basin. This basin, located in south-eastern Albania (

Figure 2) is the largest intermountain artesian basin of the country (

Figure 6). It is filled with Pliocene-Holocene deposits (max thickness about 250 m) consisting of intercalation of the gravelly intergranular aquifer, with clayey layers (Eftimi and Sara, 2022). The main recharge of the basin comes from the small rivers flowing from the mountain gorges around the Korça plain. The intensive groundwater exploitation in Korça basin started by the end of 1960s. Generally, the pumping intensification from the aquifers is always associated with the formation of a regional groundwater depression. Actually, in Korça basin in total are pumped about 400 l/s, from the Turan wellfield, used for the water supply of Korça City. As a consequence, a groundwater regional depression of about 14-16 m, is created in the center of the Turan wellfield, after some tenths of years of constant pumping.

For the improvement of the hydraulic parameters of Turan wellfield, new big diameter cable tool wells have been drilled and a new positive hydrodynamic scheme of pumping is established (Eftimi 2006, Eftimi and Sara, 2022).

The main problem regarding intensification of the groundwater use in Korça basin is the sustainability which must be established between the quantity of pumped groundwater and eventual negative environmental impacts. Safe yield is traditionally defined as the attainment and maintenance of long-term balance between the amount of groundwater withdrawn annually and the annual amount of recharge (Sophocleous 1997). However, the aquifer development, based upon the concept of safe yield, is not safe and sustainable (Sophocleous 1997, 2000, 2002, Bredehoeft 1997, Sakiyan & Yazicigil 2004). If the groundwater pumping should be limited within the natural groundwater flow for respecting the so-called “self-yield”, it might be difficult, if not impossible, to face the constantly increase of groundwater demands. Maybe more appropriate will be to respect the “basin yield” concept that can be sustained by hydrogeological system of groundwater basin without causing unacceptable changes of any environmental component of the basin.

The respect of the “basin yield” concept means a sustainable groundwater management of Korça basin, that must be necessarily accompanied by observations and control of the aquifer, water conservation measures, water quality monitoring and observation of possible negative impacts like drying up of the rivers, pronounced changes in wetlands including their habitats etc. (Eftimi & Sara 2022).

4. Water Supply from Karst Springs

Karst rocks occupy an area of 6750 km

2, or 24% of Albania's territory, and form 25 karst regions, 23 in carbonate formations and 2 in evaporitic formations (gypsum). Karst of Albania is intensively developed in wide horizontal or gently sloping carbonate rocks, mainly of massive and thick bedded Upper Triassic, Cretaceous and Upper Eocene formations. In Albania more than 1500 karst springs have been identified (Eftimi et al. 1985, 2022, 2023), and 110 of them have average discharge exceeding 100 l/s. Among them, 17 outflow discharges more than 1000 l/s, and Blue Eye Spring (

Figure 2), the biggest spring of the country, reaches 18.4 m

3/s (Eftimi and Malik 2019; Eftimi et al., 2023). Total renewable karst groundwater resources of Albania are estimated at about 227 m

3/s, and account for about 80% of all groundwater resources in the country (Eftimi 2010, Eftimi at al. 2019).

The main recharge of the karst springs is the rainfall infiltration into karst rock masses. Based on climatic data and using the empirical methods (Turc 1954, Kessler 1967) the yearly efficient infiltration is calculated. It ranges is in wide limits, from 1500 to 2000 mm in the Albanian Alps, north of the country, to 1100 to 1750 in the central and southern part, and to about 450 in south-eastern Albania (Eftimi at al. 2019).

Karst groundwater represents the main source of potable water supply in many countries and particularly in coastal areas (Bakalowicz 2005; Stevanović 2019), where urbanization is growing fast. In Albania about 2.2 million inhabitants, or nearly 80% of the population is supplied by karst groundwater (Qiriazi 2001), including a large part of Tirana. The experience of utilization of karst water resources encountered two main problems: (a) spring discharge regime, and (b) water quality deterioration.

Since the regime of recharging karst springs rainfall is highly variable, so is the discharge regimen, also. This is the reason many cities face water shortages, especially during the summer-autumn months, when karst springs significantly reduce their flows (Stevanovic at al. 2007, Stevanovic & Eftimi 2010; Parise et al. 2015b). Karst water often show significant variations in their physic-chemical and bacteriological characteristics, and experience shows that the variations in water quality are more pronounced when there are also variations in output of the karst springs (Zötl 1986, Eftimi and Malik 2019). Very important are the quality problems of karst waters related to their pollution, especially in areas with large demographic growth and industrial development (Drew and Hötzl 1999; De Waele and Follesa 2004; Stevanovic 2015). The human impact on karst aquifers is exacerbated for both their physical characteristics and the scarce awareness about their relevance by the local communities (Gunai and Ekmekci 1997, Drew and Hötzl 1999; Parise and Pascali 2003; Parise and Gunn 2007).

In the following, experiences about the exploitation of three big karst springs of Albania (Uji Ftohte, Bogova and Tushemisht) are presented.

Uji Ftohtë springs. This spring, the largest in the southern coastal, 147 km-long, areas of Albania (

Figure 2), issues from the Tragjas karst massif, consisting of Triassic dolomite and Jurassic to Eocene limestone and thin bedded cherts. In the area of the Uji Ftohtë springs a transgressive contact of carbonate rocks with Neogene clayey formations is present (Meço and Aliaj 2000, Xhomo et al. 2002). The clay Neogene formations work as a barrier that prevents the intrusion of seawater into the karst aquifer (

Figure 7). Uji Ftohtë Spring is used for the water supply of city of Vlora, which population is about 170.000 inhabitants (

Figure 7). This spring consists of 32 springs emerging at sea level, along a 1.7 km-long stretch. Three horizontal galleries parallel to the coastline, excavated at a distance of 60-70 m from the coast, at elevation of 0.2-0.5 m asl, collect inside the rocks most of the discharges into the sea karst water (Tafilaj 1964). The mean annual discharge of the three draining tunnels is about 2.0 m

3/s, while the mean water supply discharge for Vlora city varies about 0.8 m

3/s. Many chemical analyses confirmed the good quality of the Uji Ftohte¨ Springs. Based on non-systematic water quality analyses the concentrations of some chemical components are: Cl 20–150 mg/l, Na 20–90 mg/l, HCO

3 50–60 mg/l, NO

2 missing, and water hydro-chemical type is HCO

3–Ca–Mg.

However, the situation in the catchment areas of Uji Ftohte¨ Springs is undergoing rapid changes; instead of fruit trees, brushwood and meadows on outcropping rocks, an uncontrolled urban area is under development in the immediate vicinity of the springs, at elevation from 20 to 250 m (

Figure 7). The urban area does not have a properly planned waste water system and the houses have septic tanks, mostly constructed without any special isolation.

Bacteriological analyses, performed at least since 2009, confirm that Uji Ftohte¨ Springs result heavily polluted. The values of some measured bacteriological indexes confirm the groundwater pollution: total coliform 10–20, fecal coli forms (Escherichia coli) 10–17, and fecal streptococcus 2–4, which indicate possible presence of various pathogens (Goldscheider 2010). With respect to micro-biological quality, the European Guidelines and standards specify a complete absence of indicator organisms such E. coli, enterococci or other thermo-tolerant coliform bacteria (Council Directive 98/83EC 1998). With regard to numerous possible hazards emanating from the urban area, the only mitigating element seems to be the thick, impervious, cover sequences (Hötzel 1999). The new urban area near the Uji Ftoht springs is covered by red clays (“terra rossa”) with variable thickness, but this is often removed during the excavation of the foundation. As Carré et al. (2011) stated, in case of small thickness of the unsaturated zone, like at Uji Ftohtë, the purification process is also limited by the short time the water stays in the aquifer.

To protect the water quality of Uji i Ftohte¨ Springs the following measures are recommended: (a) to stop the development of the upstream urban area, (b) to ensure that water impermeable septic tanks are constructed, (c) to construct the wastewater drainage system respecting the peculiar conditions in the considered area, and (d) to monitor the water quality and establish protective areas of the groundwater catchment. For the moment the only adopted solution is an increasing in the dosage of chlorination.

Bogova spring (

Figure 2) is an example of the negative impact of limestone extraction through quarrying activity in a karst aquifer (Gunn 1993, 2004; Parise 2016). The mentioned spring is one of three big karst springs issuing from Tomor karst massif, in Central Albania, and is located in its western part, at 344 m asl. The water quality is excellent, the conductivity is about 224 µS/cm, the total hardness is 2.54 meq/l and the water type is HCO

3-Ca-Mg (Eftimi 1991). The average discharge of the spring is about 1350 l/s, and by gravity it is used for the water supply of the cities Berat, Poliçan and Kuçove in central Albania, with a total population of about 120.000 habitants.

The spring recharge area is a clean mountainous limestone area. This situation completely changed after 1995, when the quarrying activity accelerated, due to construction industry. Quarrying is still particularly intensive upspring, at elevations about 600–1000 m a.s.l. at distances of about 1.0–3.0 km north-east of Bogova. Its first result is pollution at Bogova Spring, where from time to time the water becomes turbid. This turbidity originates from the soil, and is favored by removal of the red clay in the subcutaneous zone (Williams 1983, 2008). Favored by the well-developed conduit network in the karst aquifer, the turbidity rapidly spreads over large distances after every significant precipitation event, and impacts the springs. Brief contamination episodes are interrupted by more or less long periods of clean spring water. In some events the measured turbidity in the water distribution system of Berat varies from 2 to 4 NTU (nephelometric turbidity units), whilst the European guidelines indicate for turbidity values that must not exceed 1.0 NTU (Council Directive 98/83EC 1998). The recommendation to stop quarrying within the spring immediate protection area, with a 1 km-buffer in upstream direction, has not been respected. For the moment the only adopted ‘‘solution’’ is using small charged explosive in quarrying yards, but also this measure is not under control.

Tushemisht spring. This spring consists the southern part of St Naum-Tushemisht spring’s area, in the Ohrid Lake coastal line, at the boundary between Albania and North Macedonia (

Figure 2). The high mountain chain Mali Thatë-Galičica consisting of karst rocks separates the two lakes, Prespa Lake elevation 849 m a.s.l., from the Ohrid Lake elevation 693 m a.s.l. (

Figure 8a). This massive is a transboundary karst aquifer among Albania, North Macedonia and Greece. Water of Prespa Lake disappears in Zaver Swallow hole, to reappear at lower elevation as large karst springs along the Ohrid lake coast (Cvijić 1906). The shorter transit water distance is about 17 km. The most important springs issuing in the Ohrid Lake coastal line are the St Naum Spring, average discharge rate of 7.50 m

3/s issuing in North Macedonia, and Tushemisht spring average discharge 2.5 m

3/s, issuing in Albanian territory.

As determined by the application of the environmental isotope methods, the total discharge of this spring group is recharged at nearly 50% by the karst water of Mali Thatë-Galičica and at about 50% by the Prespa Lake (Eftimi and Zoto 1997, Anovski et al. 1991).

The city of Pogradec, located in the southern part of Ohrid Lake (

Figure 2), is an important fast developing tourist center of Albania. Since about 1980 Pogradec is supplied with water by a gallery about 35 m-long, excavated near the Tushemisht spring (

Figure 8a). About 70 to 120 l/s water was pumped in a small collecting room. After detailed hydrogeological investigations in 2002, it was decided to enlarge the tapping structure, aimed at increasing the spring discharge to about 250 l/s. However, serious concerns arise about the possible pollution of the pumped karst water from the seepage of the eventually polluted Ohrid Lake water.

The practice of exploitation of karst springs offers many examples for the solution of similar problems, often consisting in the construction of special hydrotechnical structures, such underground diaphragms (Cotecchia et al. 1982; Milanović 2000, Stevanovic 2015

). Similarly, to avoid the infiltration of lake water to Tushemisht Spring, a pumping shaft isolated by an impermeable diaphragm surrounding the waterworks was constructed (

Figure 8b). The diaphragm consists of 74 alternated cemented and reinforced boring piles diameter 600 mm and depth 5 to 10.5 m, tightly fixed on karstified limestone basement. As proved by trace experiments, the concrete curtain resulted water tight and even the groundwater level in the collecting room during the pumping of about 200 l/s was stabilized about 30 cm above the lake level.

Another important issue is the possibility of the pollution of Tushemisht spring by the polluted Prespa lake water recharging the spring. This is facilitated by large karst conduits separating the lakes (Amataj et al. 2007), enabling high flow velocities shortening the transit and reducing the necessary time for micro-organisms to day (Drew 1999). The main reason for the pollution of Prespa Lake seems to be the rapid increase of population and tourism. This appear to be the result of intensified agriculture, village waste disposal sites scattered along the coastal line of Lake Prespa, and discharging into the lake of the untreated waste water of the villages (Eftimi and Zojer 2015). The situation become more problematic due to the catastrophic decrease in level of Lake Prespa of about 10.5 m during the last 40-50 years as result of the climate changes (Eftimi et al. 2021), corresponding to about 25-30% of the total lake volume (Popovska and Bonacci 2007). The dramatic drop in lake level is accompanied by increased eutrophication (Matzinger 2006). Nevertheless, till now it has not been reported any significant pollution of the Tushemisht spring.

5. Water Supply from Drilling Wells in Karst Aquifers

One of the main problems in water supply, related to karst springs, is the water shortage during the recession period (Zötl JG 1986, Eftimi & Malik 2019; Liso and Parise 2020). The intake structures usually tap the natural discharge of the springs, despite the fact that dynamic water resources in karst often surpass undoubtedly the used karst water resources (Castany 1968). Based on groundwater monitoring, the ratio between maximum and minimum discharge for karst springs of Albania vary from 3 to more than 6, but there are also karst springs with maximum discharges higher than tenths of m3/s, that dry up totally (Eftimi 2010, 2020, Eftimi and Malik 2019).

The hydrogeological experience shows that, for facing water shortage of the springs, the most appropriate type of water intake is through pumping dynamic karst water reserves by application of large diameter wells (Stevanović et al 2007; 2015; Parise et al. 2015b). The hydrogeological conditions must allow the drilling wells, sited in karst aquifers, to pump the static reserves during a short time, which should be replenished during the next wet season (Bakalowicz 2005; Stevanović 2019). Usually, the drilling wells are located up valley in the karst catchment. The karst conduit system may be very heterogenous and the boreholes at small distances may have very different productivity. Same typical examples of application of drilling wells for pumping during the shortage periods of karst springs are described by Stevanović et al. (2009).

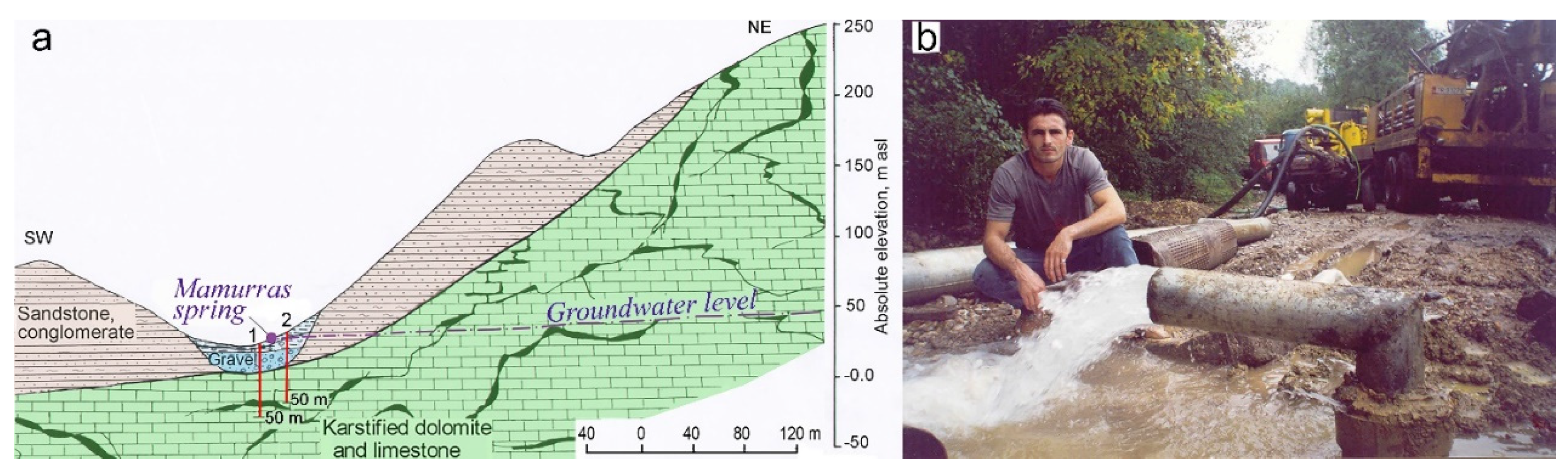

In the following, two examples of successful water supply by drilling wells near shortage springs are shortly described. The small

Mamurras City, located in Central Albania, was initially supplied by a karst spring discharging about 20 l/s, quite insufficient for the normal water supply of increasing population of the city. The spring issues from Makaresh karst massif, consisting of Upper Cretaceous dolomite and limestone, with calculated water resources at about 400 l/s. During 2002 two wells, 50 m-deep, have been drilled near to the spring (

Figure 9a). The pumping tests confirmed that both wells are abundant; the free flow of well 1 was nearly 50 l/s (

Figure 9b), while the pumping capacity of well 2 is 60 l/s. Pumping one well and leaving the second as spare well, since 2002 the Mamurras city is normally supplied with about 50 l/s by one single well.

A similar example is the small

Bilisht City in south-eastern Albania (

Figure 2). The city was supplied by an ascending karst spring issuing from the Upper Eocene conglomerate limestone and discharging about 12 l/s. For improving the water supply of Bilisht during 2008 upspring have been drilled two wells, 150 m-deep. The pumping capacity of the new wells, individually, is about 35 l/s.

This experience of using drilling wells for the capture and pumping of the renewable karst static water resources could be applied also in other places of Albania like around the cities of Koplik in North Albania and Permet and Gjirokastra, in South Albania. There are cases of ascending Vaucluse springs when the pumps are installed into the siphon channels of very big temporary springs like in Viroi and Goranxi, in South Albania, and of the perennial spring Syri Sheganit in the North of the country. In each case the pumping capacity has been about 2 to 3 m3/s, and the pumped water is used for irrigation.

6. Water Supply Wells in Fissured Rocks

There are two main fissured aquifers in Albania, related to

magmatic and to sandstone-conglomerate rocks (Figure 2a).

The magmatic rocks crop out in inner Albania and occupy about 4,200 km

2. They are mainly ultrabasic rocks, like serpentine and less basic rocks as gabbro. Generally, their water resources are related to fissures and fault zones (Tafilaj 1977). Both types of zones are distinguishable in the magmatic rocks. The first develops close to the surface (down to about 30-40 m) and is represented by weathering joints, and secondarily by faults. The groundwater of the first zone recharges small springs, usually discharging less than 1 l/s. The second zone, associated with faults, typically extends to a considerable depth of hundred meters, even more, containing usually contain pressurized (artesian) water. The drilling wells indicate a great diversity in output, reflecting the importance of the distribution of fracture systems and their frequency (Eftimi 2010). The free-flowing wells, tapping deep fault zones in intrusive rocks and placed at the low elevation valley bottoms, vary from 1 to about 8 l/s. As for the ascending springs, related to well-developed fault zones, the maximum discharges vary from about 10 to 30 l/s.

Among the Albanian cities, only two small ones, Puka and Fushe-Arrza, are supplied with water from springs of magmatic rocks, their discharges varying about 15-20 l/s. Since relatively larger springs issuing from the magmatic rocks are missing, the increase of their water supply capacity of Puke and Fushë-Arrza still represents an unresolved problem. The encouraging results of the water wells drilled in magmatic rocks of Albania (Tafilaj 1964, Eftimi 2010), must serve as support for intensifying the drilling of water supply wells for the small cities located at such rocks

The second aquifer fissured aquifer is that of the

sandstone-conglomerate (molasses) rocks, outcropping at about 4000 km

2. The older molasses rocks of Aquitanian to Upper Tortonian age, consisting of intercalation of sandstone and clayey rocks, has low permeability or are practically without water (

Figure 2). The average values of transmissivity and specific capacity of water wells are respectively about 3 to 15 m

2/day and about 0.03 to 0.2 l/s/m. The small groundwater resources are used only for family water supply. The Pliocene molasses deposits, represented by sandstone-conglomerate deposits known with the local name of Rrogozhina Formation, cover an area of 2300 km

2 and are located in the Near-Adriatic plain. The average values of transmissivity and specific capacity have, respectively, values of about 80 m

2/day and about 0.4 l/s/m, while the maximum capacities of the wells are about 10 l/s (Eftimi 2002, 2003). The small cities of Kavaja and Roskovec, in central Albania, are supplied from the Rrogozhina Formation aquifer with quantities of about 20 to 40 l/s. As the groundwater of this aquifer is mean hard to hard, and the concentration of the iron often excides the drinking water limit of 0.3 mg/l, the use of this aquifer is constantly reducing.

7. Water Supply from Two or More Different Water Supply Sources, Including Surface Waters

In Albania only two cities, Tirana, the capital and Gjirokaster, in southern Albania, have mixed water supplies systems, consisting of two or more different water sources.

Tirana city. The water supply system of Tirana City consists of: a) three karst springs; b) four wellfields in intergranular aquifers, and c) surface water (

Figure 10).

The increase of water supply capacity for Tirana is related to the development of the city itself. The first centralized water supply system of Tirana (capacity of 30 l/s) was constructed in 1940 and used water from the Tirana River. In 1951 the Selita karst spring water supply system was constructed, that provided by gravity, from a distance of about 17 km, in average 440 l/s for the city, so that the existing river water supply system was abandoned. To face the increased need for water of the city, in 1961 the second water supply system of Shën Mëria karst spring was constructed, which provides in average about 500 l/s, and, in 1974 the third karst spring, that of Bovilla, with average capacity of 381 ls/s, was included in the system (

Figure 10). The amount of karst water springs, used for Tirana's water supply, depends not only on the discharge fluctuation of the springs (

Table 2), but also on the capacity of transmitting pipes (

Table 3). While the average total annual flow of the springs Selita, Shën Mëria and Bovilla is 1782 l/s, their average annual used capacity is 1320 l/s. To balance the reduction of the springs discharges during summer-autumn season, as well as to face the necessity for additional water quantities during 1975-1990, some pumping wells, located in Tiran plain are included in Tirana water supply system (

Figure 10). The overall discharge of the pumped wells is about 300 l/s, a quantity that cannot satisfy the water needs of the city.

The political changes of 1990 in Albania were accompanied by very intensive demographic movements and the population of Tirana, from about 250.000 inhabitants in 1980, increased very fast numbering today about 900.000 inhabitants. To normalize the city water supply situation, a large water supply system fed by the Bovilla reservoir was constructed. Before the distribution, the water of the reservoir is treated physically and bacteriologically in a treatment plant, initially constructed for the capacity 600-700 l/s, and at present increased to about 2000-2500 l/s.

Table 3 shows that the total water supply capacity of Tirana is equal to 4265 l/s. Unfortunately, performance of the water supply systems is despairing; the difference between System Input Volume and Billed Authorized Consumption, representing the water losses, is about 65%. In practice, the billed water quantity of Tirana results only 1493 l/s. Similarly, to that of Tirana, the “water losses” in other urban water supply systems of Albania present about the same percentages.

Although different, as regards the chemical composition, the quality of Tirana water sources respects the drinking water standard limit (DCM No 145; Eftimi at al. 2000). Concerning the bacteriological composition, there are constant problems, mostly with the groundwater pumped in the intergranular gravel aquifer of Tirana plain. Generally, in these well-fields the recommended groundwater protection measures are not respected; many buildings are constructed, even within the strong sanitary protection zone of the shallow pumped wells. Further, the water of Bovilla Lake is under constant threat to be polluted by untreated sewerage of the rural centers (villages), situated in the lake watershed. Generally speaking, the rivers Lana and Tirana, representing the main recharge sources for the intergranular aquifer of Tirana, collect all the untreated sewages of the city, and are heavily polluted (Eftimi at al. 2000).

Gjirokastra city. Gjirokastra is the second city in Albania with a combined water supply system. Traditionally, the city was supplied with water from the “steras” (cisterns), situated in the cellars of the houses, where the rain water was collected, similarly to other countries in the Mediterranean Basin (Laureano 2001; Mays et al. 2007; Parise and Sammarco 2015; Valipour et al. 2020). The first centralized water supply system of the city was constructed in 1939; the karst spring water was diverted by gravity for the water supply of Gjirokaster. The used capacity of this spring varies about 15-40 l/s, but soon was completely insufficient for the normal water supply of the city, particularly during the summer season. To compensate the summer water demands of the city, during 1970 the water supply system of Hosi karst spring was built, with used capacity about 40-60 l/s. However, the water quantity become soon problematic again, particularly during the summer. To compensate the needed water quantity demand, during 1985-90, two big diameter wells were drilled in Drinos River valley, where 100 l/s are pumped from the intergranular aquifer filling the valley. As the hydraulic connection of the gravel aquifer with the Drinos River is very intensive and the distance of recharging river to pumped wells is only about 120 m, the contamination of the groundwater by the eventually polluted river water is a constant problem.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

Albania is a country rich in groundwater. The calculated renewable resources consist of about 288 m3/s, while the total exploitable resources are about 140 m3/s (Eftimi 2010). Actually, the groundwater resources used for the water supply are estimated at about 14 m3/s, consisting only of 10% of exploitable groundwater resources of Albania. Groundwater in general is more desirable than the surface water as a water supply source, for the main following reasons: (1) it is commonly free of pathogenic organisms; (2) temperature, color and chemical composition are nearly constant; (3) groundwater supplies are not seriously affected by short droughts; (4) the radiochemical and biological contamination of most groundwater is difficult (Davis and De Wiest 1970). In Albania, a mountainous country, the high elevation springs are particularly more desirable as water supply source, because of the possibility of transporting the water by gravity to the settlements. This work demonstrates that the problems of groundwater use for water supply of the cities, or of the settlements in general, depend mainly on the type of the aquifer. Thera are two more important aquifers widely used for the water supply of Albania's settlements; the intergranular gravel-sandy aquifers, and the limestone-dolomite karst aquifers.

In Albania, about 85% of groundwater resources used for water supply is pumped from the intergranular gravel-sandy aquifers. The main problem for the intergranular aquifers is the location of pumping wells. Locating them near the recharge areas ensures the sustainability of the groundwater flow, and the possibility to increase the pumping capacity of wells through induced infiltration (Rorabaugh 1956; Walton 1960, Bentall 1963 Kruseman and De Ridder 2000, Eftimi 1982). On the other hand, increases in the hydraulic gradient of the groundwater flow, as well as the groundwater flow velocity, consequently shorten the transit time of the groundwater flow from recharge area (e.g. the rivers) to the pumped wells. A similar situation is undesirable in terms of quality of the pumped water, because the most resistant microbes and viruses completely disappear when remaining underground not less than 50 days. For this reason, some legislations, like in Germany, use the 50-day of water travel time, assuming that most of pathogens will be filtered or inactivated (Goldscheider 2010). Therefore, to avoid pollution, this principle should be applied when dimensioning the groundwater protection zones in Albania, too. The common main pollutants of groundwater are the untreated domestic waste water of urban centers, industrial waste water and uncontrolled use of pesticides in agriculture (Chiesa 1994; Drew and Hötzll 1999), which is also the case for Albania.

Gravel abstraction from the riverbeds for construction purposes is another important pollution source from the hydrocarbons or fuels used. Beside this, the negative impact of the riverbed quarrying is also the groundwater level lowering as a result of the thickness reduction of the gravel deposits in the recharge area. This is transmitted also in the decrease of the hydraulic pressure of freshwater flow in seaside areas facilitating the seawater intrusion (Bear and Verruijt 1994).

About 2 million of inhabitants, or 70% of Albanian population, are supplied with water from karst aquifers, including a large part of Tirana. Although often problematic, karst groundwaters represents the main source of potable water supply in many countries (Bakalowicz 2005; Stevanović 2019). There are two important problems when karst aquifers are used as a water supply source: (a) the significant decrease of spring flow during the recession period, often resolved including new karst springs in the water supply system, or other water sources; (b) easy contamination of karst aquifers by urbanized areas, agricultural activity and quarrying (Gunn 2004; Parise et al. 2015b; Stevanovic 2015; Pisano et al. 2022). The examples above, dealing with the use of karst aquifers as water supply sources in Albania support this conclusion. In addition, fragility of the karst environment, and diffuse problems and degradation deriving from anthropogenic activities in the Albanian karst, has to be taken into account, too (Parise et al. 2004, 2008).

One of the most important aspects of groundwater protection, in general, is the determination of the three groundwater protection zones, as foreseen in Water Law of Albania, in accordance with the UE Directives 2000/60/EC and 2006/118/EC. Regarding the actual situation in Albania it can be said that: (a) most of water supply sources are determined without performing the necessary special hydrogeological investigations; (b) the recommended measures for different protection zones are not respected in many cases; (c) dimensioning of the groundwater protection zones does not take into consideration the fifty days transit time (Goldscheider 2010).

It must be stressed that for sustainable water resources management in Albania, a reasonable equilibrium between groundwater intensive exploitation and their protection from depletion and pollution should be realized. This could be achieved mandatorily by intensive monitoring and control of aquifer and water conservation measures. The existing monitoring network in Albania (Gelaj et al. 2014) is quite incomplete as concerns the number of observation points and of the observed parameter.

To face the situation of municipality water supply in Albania, it appears necessary to urgently undertake the following measures: intensification of basin-wide hydrogeological investigations; establishing of a wide groundwater monitoring network including hydrodynamic, hydro-chemical and environmental isotopes; construction of detailed GIS hydrogeological maps at scale 1:25.000-1:50.000, and related mathematical models of the aquifers; compilation of the aquifer vulnerability maps and establishing the groundwater protection zones for each water supply source, based on special hydrogeological investigation. Particularly, aimed at facing the problems dealing with transboundary aquifers, as a first step there is the creation of active joint consultative bodies between transboundary countries, for collecting, harmonizing and interchanging all available monitoring and geological-hydrogeological data. The sustainable water supply of settlements is linked with efficient governmental laws, with public education encouraging the maintenance of water supply systems and with a serious increase of the public interest for these problems, to build up an environmental awareness, even in the rural areas.

Acknowledgments The authors are grateful to Zoran Stevanović and Mario Parise for their very helpful comments and advises that greatly improved this paper.

Author Contributions Romeo Eftimi: conceptualization, methodology, data analyses and writing-original draft. Kastriot Shehu: collecting and analyzing the data, methodology, supervision. Franko Sara: collection and analyzing the data, methodology, writing review, and supervision.

Founding: This research received no external funding.

Availability of data and materials Readers can contact authors for the availability of data and materials.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Declarations Conflicts of Interest: No conflict of interests is declared for this article.

Consent to participate All the authors gave explicit consent to participate in this study

Consent to publish All the authors gave explicit consent to publish this paper

References

- Amataj S, Anovski T, Eftimi R, Benishke R, Gourcy L. Kola L, Leontiadis I, Micevski E, Stamos A, Zoto A (2007) tracer methods used to verify the hypothesis of Cvijić about the groundwater connection between Prespa and Ohrid lakes. Environ Geol 51:749-755.

- Anovski T, Andonovski B, Minceva B (1991) Study of the hydrologic relationship between Ohrid and Prespa lakes, Procedings of an IAEA International Symposium, IAEA-SM-319/62p, Vienna, 11-15 March 1991.

- Angelakis A, Voudouris KS and Tchobanoglous G (2020) Evolution of water supplies in the Hellenic world focusing on water treatment and modern parallels. IWA Publishing 2020 Water Supply 20.3 2020.

- Baçe A, Meksi A, Riza E, Karaiskaj Gj, Thomo P (1980) The history of Albanian architecture, (in Albanian). Tirana.

- Bakalowicz M (2005) Karst groundwater: a challenge for new resources. Hydrogeol J 13, pp 148-160.

- Bakalowicz M (2018) Coastal Karst groundwater in the Mediterranean: a resource to be preferably exploited onshore, not from karst submarine springs. Geosciences 8:258.

- Bear, J. & Verruijt A (1994) Modelling groundwater flow and pollution. Theory and applications of transport in porous d’media - Riedel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Bochever FM (1979) Vodozabori podzemnih vod, Moskva, Stroizdat. Pp 285.

- Bonaci O (2015) Karst hydrogeology of Dinaric chain and isles. Environ Earth Sci. [CrossRef]

- Biondić B, Biondić R (2003) State of seawater intrusion of the Croatian coast. In: Lopez-Geta JA, De Dios Gomez J, De La Orden J (eds) Coastal aquifers intrusion technology: Mediterranean countries. Geological Survey of Spain (IGME, Geological Survey), Madrid, pp 225-238.

- Bredehoeft 1997. Safe yield and the water budget myth. Groundwater Water 35(6):929.

- Carré J, Oller G, Mudry J (2011) How to protect groundwater catchments used for human consumption in karst areas? 9th Conference on Limestone Hydrogeology. 2011, Besancon, France, 87-89.

- Castany G (1968) Prospection et exploitation des eaux souterraines, DUNOD, Paris.

- Ceka N (1982) Apolonia e Ilirise, Shtepia Botuese “8 Nentori’’, pp 244.

- Cotecchia V, Micheletti A, Monterisi L, Salvemini (1982) Caratteristiche tecniche delle opere per l’incremento di portata delle sorgente dell’Aggia (Alta Val d’Agri). Geol Applicata e Idrogeol V XVII, 1982, pp 365-384.

- Chiesa G (1994) Inquinamento delle acque sotterranee, Hoepli-Milano ISBN 88-203-2120-3.

- Cvijić J (1906) Fundamental of geography and geology of Macedonia and Serbia (in Serbian), Serbian Royal Academy, Spec. Ed. Books 1,2, VIII+688, Belgrade.

- Council Directive (98/83EC) (1998) On the quality of water intended for human consumption.

- Davis SN, De Wiest RJM (1970) Hydrogeology, New York/London/Sydney: John Wiley and Sons.

- DoCM 145, (26.02.1998) “National standards, based on the potable water sanitation rules, designing, establishment and supervision of water supply systems.

- DoCM No 643, (14.09.2011) National Strategy of Water Supply and Sewerage Services ISBN: 978-9928-08-086-8.

- Drew D, Hötzl H Eds (1999) Karts hydrogeology and human activities, Balkema.

- De Waele and Follesa (2004) Human impact on karst: the example of Lusaka (Zambia). Int J Speleol 32(1/4), pp 71–83.

- Eftimi R (1966) Hydrogeological overview of the Mat River alluvial plain (in Albanian). Permb. Stud. Nr 4, pp 53-66.

- Eftimi R (1982) Hydraulic parameters of the intergranular gravelly-sandy aquifers of the Western lowland of Albania, (in Albanian), Dissertation, University of Tirana, Geological Faculty, 1982.

- Eftimi R (2006) Hydraulic characteristics of the big capacity water supply wells of Korça City, in Albania. In: Proceeding of XVIIIth Carpathian-Balkan Geological Association, Eds: Sudar M, Ercegovacm M, Grubić A. Belgrade, pp. 118-122.

- Eftimi R (2010) Hydrogeological characteristics of Albania, AQUAmundi - Am01012: pp 079-092. p.

- Eftimi R (2012) Intensification of Groundwater Pumping in Fushe Kuqe Alluvial Basin for the Water Supply of Durres City in Albania, and the Possible implication of Seawater Intrusion. Archive of ITA Consult.

- Eftimi R (2020) Karst and karst water resources of Albania and their management. Carbonates and Evaporites 35: 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Eftimi R and Zoto J (1997) Isotope study of the connection of Ohrid and Prespa lakes. International Symposium “Towards Integrated Conservation and Sustainable Development of Transboundary Macro and Micro Prespa Lakes”, Korça-Albania.

- Eftimi R, Bisha G, Tafilaj I, Sheganaku Xh (1985) Hydrogeological map of Albania, scale 1:200.000. Nd. Hamid Shijaku, Tirana. [CrossRef]

- Eftimi R, Shehu K, Leno L (2000) Water quality of Tirana water supply systems (in Albanian). ECAT Tirana.

- Eftimi R, Bisha G, Tafilaj I, Habilaj L (2009) International Hydrogeological Map of Europe sc. 1:1.500.000, Sheet D6 Athina, (Albanian share). Bundesanstalt für Hanover Geowissenschaften und Rohstolfe/UNESCO,.

- Eftimi R, Zojer H (2015) Human impacts on karst aquifers of Albania. Environ Earth Sci 74:57-70. [CrossRef]

- Eftimi R, Malik P (2019) Assessment of regional flow type and groundwater sensitivity to pollution using hydrograph analyses and hydrochemical data of the Selita and Blue Eye karst springs, Albania. Hydrogeology Journal. [CrossRef]

- Eftimi E, Stevanović Z, Stojev V (2021) Hydrogeology of Mali Thate-Galičica karst massif related to the catastrophic decrease of the level of Lake Prespa. Environmental Earth Science (2021) 80:708. [CrossRef]

- Eftimi R, Sara F (2022a) Quantity and quality of groundwater of intermountain basin of Korça in Albania and implication for sustainable management. Geolagìčnij žurnal, 4 (381): 00-00. https://doi.org, pp 45-64.

- Eftimi R, Bisha G, Tafilaj I, Sheganaku Xh (2022b) Hydrogeological map of Albania at a scale of 1:200,000, principles of compilation and content – a document of Albanian pioneering hydrogeological research since the 1960s. Mineralia Slovaca, Web ISSN 1338-3523, ISSN 0369-2086.

- Eftimi R, Parise M, Liso IS (2022) Karst brackish springs of Albania. Hydrology, 9, 127. [CrossRef]

- Eftimi R, Liso IS, Parise M (2023) Classification and hydro-geochemistry of karst springs along the southern coast of Albania, Carbonates and Evaporites, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13146-023-00856-y, pp 18.

- Ferris JG, Knowles DB, Brown RH, and Stallman RW (1962) Theory of Aquifer Tests. Ground-water hydraulics. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1536-E. pp 174.

- Foster S, Morris B, Lawrence A, Chilton (1999) Groundwater impact and issues in developing cities – An introductory review (in John Chilton (ed) Groundwater in the urban Environment, Balkema), pp 3-16.

- Freeze RA, Cherry JA (1979) Groundwater, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Clifs, N.J. pp 605, ISBN 0-13-365312-9.

- Gelaj A, Marku S, Puca N (2014) Evaluation and monitoring of groundwater of Albania Bul. Shk. Gjeol. 2/2014- Proceedings of XX CBGA Congress, pp 117-120.

- Goldscheider N (2010) Delineation of spring protection zones. In: Kresić N, Stevanović Z (eds) Groundwater Hydrology of Springs, ELSEVIER, pp 305-338.

- Günai G, Ekmekci M (1997) Importance of public awareness in groundwater pollution. In: Günai G, Johnson K (eds) Proc. 5th Int Symposium and field seminars on Karst Water & Environmental, Antalya-Turkey, Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 3–10.

- Gunn J (1993) The geomorphological impacts of limestone quarrying. Catena 25: 187-198.

- Gunn J (2004) Quarrying of limestones. In Gunn J (Ed.) Encyclopedia of cave and karst science. Routledge, London: 608-611.

- IGRAC (2012) Ed. Kukuric N, Transboundary aquifers of the World, sc. 1:50.000.000.

- Kessler H (1967) Water balance investigations in the karst regions of Hungary. Act Coll Dubrovnik. AIHS-UNESCO, Paris, pp 91-105.

- Koutsoyiannis D, Mamassis N (2015) The water supply of Athens through the centuries. Conference paper, DOI: 1, 0.13140/RG.2.2.24516.12400/1. Presentation available online: www.itia.ntura.gr/1543/.

- Kresic N, Stevanovic Z (eds) (2010) Hydrology of Springs: engineering, theory, management and sustainability. Elsevier Inc. BH, Burlington-Oxford.

- Kruseman GP & De Ridder NA (2000) Analyses and evaluation of pumping test data, In Intern. Inst. Land Reclamatio and Improvement Bull. 11, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- Kumanova, X. Kumanova, X., Marku S. Fröjdö, S., Jacks, G. (2015) Recharge and sustainability of a coastal aquifer in northern Albania. Hydrogeology Journal. [CrossRef]

- Lako, A., 1973: Hydrogeological conditions of Shkumbin River valley of the area Labinot-Fushe Cerrik (in Albanian). Përmb. Stud., 3, pp 105–133.

- Laureano P (2001) Water atlas. Traditional knowledge to combat desertification. Bollati Boringhieri, Torino.

- Lombardi L, Corrazza A (2008) L’acqua e la cittá in epoca antica. In: La Geologia di Roma, dal centro storico all periferia, Part I, Memorie Serv Geol d’Italia. Vpl lXXX, S.E.L.C.A, Firence, pp 189-319.

- Liso IS, Parise M (2020) Apulian karst springs: a review. J Environ Science and Engng Technol 8: pp 63-83.

- Mays LW, Koutsoyiannis D, Angelakis AN (2007) A brief history of urban water supply in the Antiquity. Water Science & Technology Water Supply, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Matzinger A (2006) Is the anthropogenic input jeopardizing unique Lake Ohrid? – Mass flux analyses and management consequences. Doct. Sciences Thesis. P 130.

- Meço N, Aliaj Sh (2000) Geology of Albania. Gebrüder Bornatraeger Berlin, Stuttgart.

- Milanović PT (2010) Geological engineering in karst. Belgrade, Zebra.

- Noner JC (2003) Introduction to hydrogeology, Balkema, ISBN 90 2 65 1930 3.

- Parise M (2016) Modern resource use and its impact in karst areas – mining and quarrying. Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie 60, suppl. X: 199-216.

- Parise M, Pascali V (2003) Surface and subsurface environmental degradation in the karst of Apulia (southern Italy). Environmental Geology 44: 247-256.

- Parise M, Gunn J (Eds.) (2007) Natural and anthropogenic hazards in karst areas: Recognition, Analysis and Mitigation. Geological Society, London, Special Publication 279, 202 pp.

- Parise M, Qiriazi P, Sala S (2004) Natural and anthropogenic hazards in karst areas of Albania. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 4: 569-581.

- Parise M, Qiriazi P, Sala S (2008) Evaporite karst of Albania: main features and cases of environmental degradation. Environmental Geology 53 (5): 967-974.

- Parise M, Closson D, Gutierrez F, Stevanovic Z (2015a) Anticipating and managing engineering problems in the complex karst environment. Environmental Earth Sciences 74: 7823-7835, DOI :10.1007/s12665-015-4647-5.

- Parise M, Sammarco M (2015b) The historical use of water resources in karst. Environmental Earth Sciences 74: 143-152. . [CrossRef]

- Parise M, Ravbar N, Živanovic V, Mikszewski A, Kresic N, Mádl-Szo ̋nyi J, Kukuric N (2015b) Hazards in Karst and Managing Water Resources Quality. Chapter 17 in: Z. Stevanovic (ed.), Karst Aquifers – Characterization and Engineering. Professional Practice in Earth Sciences, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-12850-4_17, Springer, pp. 601-687.

- Pisano L, Zumpano V, Pepe M, Liso IS, Parise M (2022) Assessing Karst Landscape Degradation: a case study in Southern Italy. Land 11: 1842. .

- Rorabaugh MI (1956) Groundwater in North-eastern Louisville, Kentucky, with reference to induced infiltration. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1360-B.

- Sakiyan J, Yazicigil H (2004) Sustainable development and management of an aquifer system in western Turkey, Hydrogeology Journal 12: 66-80.

- Sophocleus M (1977) Managing water resources systems: Why safe yield is not sustainable. Ground Water 35(4):561.

- Sophocleus M (2000) From safe yield to sustainable development of water resources: the Kansas experience. Journal of Hydrogeology, 235: p. 27-43.

- Sophocleus M (2002) Interaction between groundwater and surface water: the state of the science. Hydrogeological Journal 10:52-64. DOI 10.1007/s10040-0170-8.

- Stevanović Z (2015) Karst aquifers – characterization and Engineering. Springer. 1007. [CrossRef]

- Stevanović Z (2019) Karst water in potable water supply: a global scale overview. Environmental Earth Science 78:662. [CrossRef]

- Stevanović Z, Jemcov I, Milanović S (2007) Management of karst aquifers in Serbia for water supply. Environ Geol 51: 743-748. [CrossRef]

- Stevanović Z, Eftimi R (2010) Karstic sources of water supply for large consumers in South-Eastern Europe – sustainability, disputes and advantages. Conference of Karst, Plitvice Lakes, Croatia – 2009, 181-185.

- Stevanović Z, Stevanović AM, Pekaš Ž, Eftimi R, Marinović (2022) Environmental flows and demands for sustainable water use in protected karst areas of the Western Balkans. Carbonates and Evaporites. [CrossRef]

- Suresh TS (1999) Impact of urbanization on groundwater regime: A case study of Bangalore City, Kamataka, India. An introductory review. In John Chilton (ed) Groundwater in the urban Environment, Balkema, pp 251-258.

- Tafilaj I (1964) Hydrogeological conditions of Uji Ftohte Springs, near Vlora. Albanian Hydrogeological Service, Tirana, Albania.

- Tafilaj I (1977) Hydrogeological classification of mines of Albania (In Albanian): Permb. Stud. No 3, Tirana, pp 1-13.

- Tartari M (2010) Hydrogeologic map of Fushe Kuqe intergranular aquifer. Albanian Hydrogeological Service, Tirana, Albania.

- Theis CV (1935) The relation between the lowering of the piezometric surface and the rate and duration of discharge of a well using ground-water storage: Am. Geophys. Union Trans, pt. 2, p. 519-524; dupl. as U.S. Geol. Survey ground Water Note 5, 1952.

- Turc L (!954) The soil balance: relations between rainfall, evaporation and flow (in French). Geogr Rev 38:36-44.

- Valipour M, Abdelkader TA, Antoniou GP, Sala R, Parise M, Salgot M, Sanaan Bensi N, Angelakis AN (2020) Sustainability of underground hydro-technologies: from ancient to modern times and toward the future. Sustainability 12: 8983. [CrossRef]

- Xhomo A, Kora A, Xhafa Z, Shallo M (2002) Geology of Albania (Notes of the Geological Map of Albania, sc. 1:200;000). Albanian Geological Service.

- Walton WC (1970) Ground water resources evaluation: Mc Graw-Hill Book Company, 1970 Williams PW (1983) The role of subcutaneous zone in karst hydrology. International Journal of Hydrology 61: 45−67.

- Williams PW (2008) The role of the epikarst in karst and cave hydrogeology: a review. International Journal of Speleology 37: 1−10.

- Zötl JG (1986) An important factor for the drinking water supply in Austria. Environ Geol Water Sci Vol. 7, No. 4, pp 237-239.

Figure 1.

a The Monumental Fontana of Apolonia, IV century BC (after Caka 1982); b Aqueduct of Girokaster (gravure of XIX century); c Aqueduct of the city of Tepelen (b and c, after Baçe et al. 1980).

Figure 1.

a The Monumental Fontana of Apolonia, IV century BC (after Caka 1982); b Aqueduct of Girokaster (gravure of XIX century); c Aqueduct of the city of Tepelen (b and c, after Baçe et al. 1980).

Figure 2.

a Map of groundwater occurrences of Albania (after Eftimi at al. 2009), b Map of water supply sources of the cities of Albania.

Figure 2.

a Map of groundwater occurrences of Albania (after Eftimi at al. 2009), b Map of water supply sources of the cities of Albania.

Figure 3.

Hydrogeological map of intergranular alluvial aquifer of Mat River Plain, sc. 1:50.000.

Figure 3.

Hydrogeological map of intergranular alluvial aquifer of Mat River Plain, sc. 1:50.000.

Figure 4.

Scheme of the groundwater of the gravel aquifer in the Krasta Vogel well field, riverbank of Shkumbin River. Nowadays the Krasta Vogel plain is totally occupied by new houses.

Figure 4.

Scheme of the groundwater of the gravel aquifer in the Krasta Vogel well field, riverbank of Shkumbin River. Nowadays the Krasta Vogel plain is totally occupied by new houses.

Figure 5.

The new developed urban area is mincing the wellfield of Dobrac, with capacity of about 1000 l/s, used for Shkodra City water supply.

Figure 5.

The new developed urban area is mincing the wellfield of Dobrac, with capacity of about 1000 l/s, used for Shkodra City water supply.

Figure 6.

Hydrogeological map of Korça inter-mountain basin (after Eftimi and Sara 2022a).

Figure 6.

Hydrogeological map of Korça inter-mountain basin (after Eftimi and Sara 2022a).

Figure 7.

Pumping station of karst spring Uji i Ftohtë – Vlore: a New urban area is developing upstream above the water collecting tunnels; b Hydrogeological cross-section of Uji Ftohtë Spring and of intake structure (after Eftimi and Zojer 2015).

Figure 7.

Pumping station of karst spring Uji i Ftohtë – Vlore: a New urban area is developing upstream above the water collecting tunnels; b Hydrogeological cross-section of Uji Ftohtë Spring and of intake structure (after Eftimi and Zojer 2015).

Figure 8.

Tushemisht spring: a Hydrogeological scheme of the transboundary karst aquifer Mali Thatë-Galičica, b sketch of isolation diaphragm, c pumping shaft during the construction.

Figure 8.

Tushemisht spring: a Hydrogeological scheme of the transboundary karst aquifer Mali Thatë-Galičica, b sketch of isolation diaphragm, c pumping shaft during the construction.

Figure 9.

a Hydrogeological cross-section through two drilling wells used for Mamurras water supply; b drilling well no. 1 free flowing about 50 l/s. Both wells are located near a small karst spring.

Figure 9.

a Hydrogeological cross-section through two drilling wells used for Mamurras water supply; b drilling well no. 1 free flowing about 50 l/s. Both wells are located near a small karst spring.

Figure 10.

Hydrogeological Map of Tirana area sc. 1:200.000 (after Eftimi et al. 1985): Areal colors: dark

blue - gravelly aquifer; dark green karstic aquifer. Other signs: red quadrangle – water supply spring

or pumping station; red line – water supply main.

Figure 10.

Hydrogeological Map of Tirana area sc. 1:200.000 (after Eftimi et al. 1985): Areal colors: dark

blue - gravelly aquifer; dark green karstic aquifer. Other signs: red quadrangle – water supply spring

or pumping station; red line – water supply main.

Table 1.

Total natural and exploitable groundwater resources of Albania (Eftimi 2010).

Table 1.

Total natural and exploitable groundwater resources of Albania (Eftimi 2010).

| Aquifers Related to: |

Natural Resources |

Exploitable Resources |

| m3/year |

m3/s |

m3/year |

m3/s |

| Intergranular aquifers |

0.47*109

|

15 |

0.945*109

|

30 |

| Carbonate karst aquifer |

7.15*109

|

227 |

2.84*109

|

90 |

| Molasse rocks aquifers |

0.45*109

|

14 |

0.22*109

|

7 |

| Magmatic intrusive rocks aquifers |

1.00*109

|

32 |

0.41*109

|

13 |

| Total groundwater resources |

9.07*109

|

288 |

4.4*109

|

140 |

Table 2.

Minimum, mean and the maximum discharges of karst springs Selita, Shën Meria and Bovilla.

Table 2.

Minimum, mean and the maximum discharges of karst springs Selita, Shën Meria and Bovilla.

| Spring |

Qmin – l/s |

Qmax – l/s |

Qmean – l/s |

Qmax/Qmin |

| Selita |

230 |

1200 |

507 |

5.2 |

| Shën Meria |

613 |

>3000 |

894 |

>5.0 |

| Bovilla |

140 |

640 |

381 |

4.6 |

| Total |

983 |

>4840 |

1782 |

|

Table 3.

Average annual water quantity used for Tirana water supply.

Table 3.

Average annual water quantity used for Tirana water supply.

| Type of water resource |

Water supply system |

Average capacity of the water supply system, l/s |

| Karst springs |

Selita and Shen Meria

Bovilla spring |

939

381 |

| Water wells in the gravelly aquifer |

Laknas, Berxull, Tirana |

445 |

| Surface |

Bovilla reservoir |

2000-2500 |

| Total |

|

3765-4265 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).