1. Introduction

The classification of pituitary tumours has advanced in parallel to the techniques used in pathology laboratories. The availability of antibodies against adenohypophyseal hormones and of pituitary transcription factors has greatly improved the identification of the pituitary subtype tumours and has undergirded the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2004, 2017, and 2022 Classification of Pituitary Tumours (1–3). Despite recognizing high-risk adenoma subtypes with a poorer prognosis during follow-up and the relevance of determining proliferative indexes, the WHO classifications still lack radiological and clinical criteria.

The use of Ki-67 labelling index (LI), p53, and the mitotic index to define proliferation remains controversial (4–12), while features assessed by MRI, such as sinus invasion, high signal intensity in T2-weighted imaging, and restricted diffusion in diffusion-weighted imaging, have been associated with recurrence (13–17). Therefore, a clinicopathological classification is necessary to improve management of pituitary tumours.

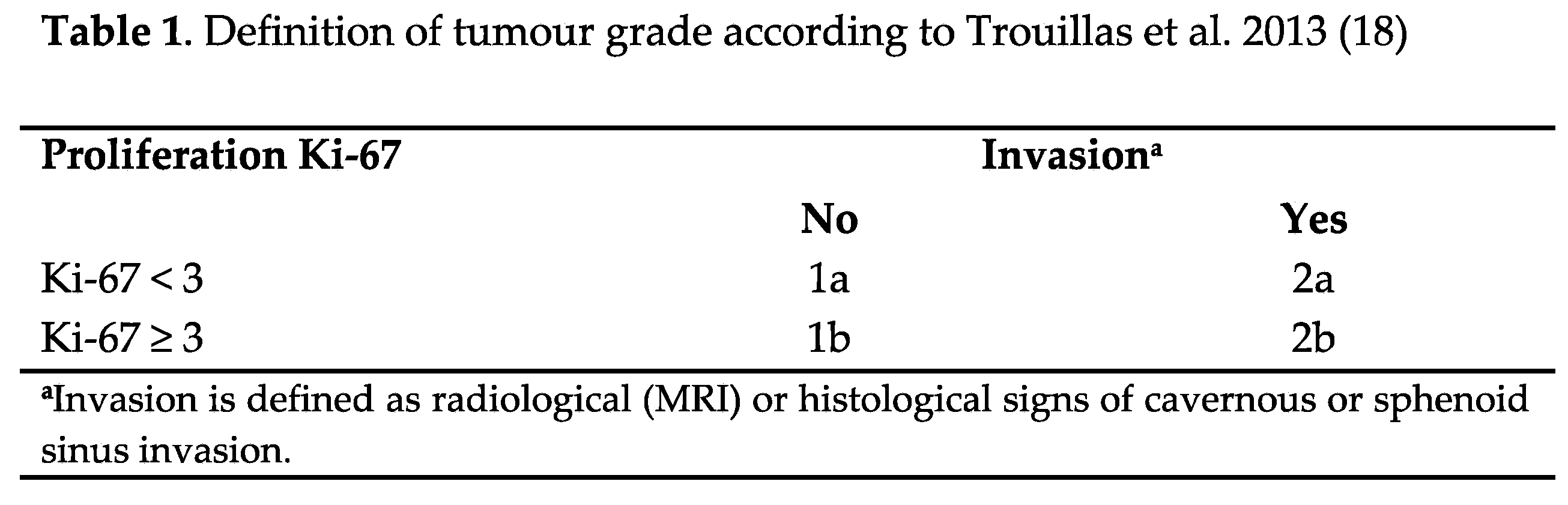

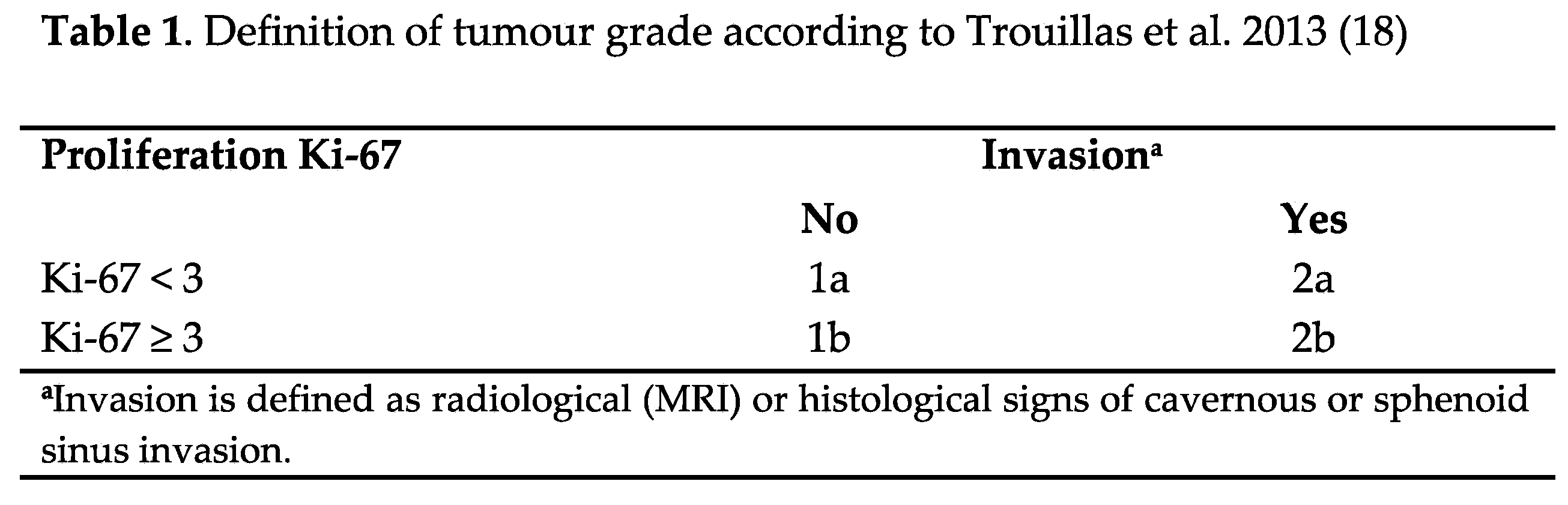

In 2013, Trouillas et al. (18) introduced a clinicopathological classification that integrated pituitary tumour subtypes with radiological and proliferation characteristics (Table 1). Subsequently, multiple series from different countries have confirmed the utility of this classification in real-world clinical practice, validating its effectiveness for better understanding and managing pituitary tumours (18–24) (

Table 6).

Adenohypophyseal tumours, recently renamed pituitary neuroendocrine tumours (PitNETs) (3), are neuroendocrine tumours that originate from adenohypophyseal cells and constitute, together with other tumours of the sellar region, 15% to 25% of intracranial neoplasms. Incidence stands at about 3.9 to 7.4 cases per 100,000 population per year, and prevalence at 76 to 116 cases per 100,000 population (25). With the proliferation and heightened sensitivity of brain imaging technology, the detected prevalence of pituitary tumours has significantly increased in recent years. This surge has increased the workload in endocrine services, particularly in pituitary tumour centres of excellence (26).

Since 2017, our group has intensively worked on the typification of pituitary tumours through the study of the pituitary adenohypophyseal hormones gene expression (27) and the pituitary transcription factors gene and protein expression (28). The clinical practice of immunostaining transcription factors has allowed us a drastic reduction in tumours classified as null cell (29) and a better classification of PitNETs (30), but it has not shed light on the behaviour of these tumours. To the best of our knowledge, no Spanish group has reported the use of a clinicopathological classification. Therefore, this study aims to classify a series of PitNETs, identified according to WHO 2017 (2) recommendations, using the clinicopathological classification proposed by Trouillas et al. 2013 (18).

2. Materials and Methods

Patients

We conducted an observational retrospective study at Dr. Balmis Alicante University Hospital, a pituitary tumour centre of excellence and reference hospital for nearly 2 million inhabitants. Of the 210 patients followed from 2013 to 2023 who were evaluated and underwent nasal endoscopic surgery and were managed by the same medical, surgical, radiological, and pathological team, 166 patients with immunohistochemistry (IHC) for pituitary transcription factors and adequate MRI follow-up were included. We defined growth total resection as the complete removal of the tumour and subtotal resection as the incomplete removal.

Demographic characteristics, histopathology reports, pre/postoperative radiological findings, and recurrence of tumours were assessed retrospectively. Follow-up data of patients whose medical records were available for at least 24 months was evaluated to determine disease status. All patients had an MRI evaluation 3-6 months after surgery, and at least two MRIs were performed over follow-up. According to hormonal and clinical features, tumours were classified as functioning or silent pituitary tumours.

Radiological variables

An expert neuroradiologist assessed MRI features of the pituitary tumour during the follow-up, including size (micro < 10 mm, macro ≥ 10 mm, and giant ≥ 40 mm), tumour volume (anteroposterior, transversal, and craniocaudal diameters), sinus invasion, and signal intensity ratio (SIR) (calculated by the quotient between the tumour intensity and corpus callosum intensity on T2-weighted images).

Sphenoidal invasion was evaluated on sagittal T1 images and defined when the hyperintense cortical lining of the sphenoidal sinus inferior wall was lost. A presurgical CT scan was also evaluated when sphenoidal invasion was doubtful. Cavernous sinus invasion was considered through T1-postcontrast and T2 coronal images, establishing invasion when the tumour exceeded the internal carotid lateral border, considered as grades 3–4 according to Knosp’s classification (17).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed for all cases by sampling two 1 mm paraffin cylinders from each tumour and building a block using a matrix tissue device (Beecher instruments). Each block included 20 cases plus 2 controls. The TMAs were exposed to a panel of antibodies against the following pituitary cell lineage transcription factors: Pit1 (ThermoFisher PA5-59662), SF1 (abcam ab217317), and Tpit (abcam ab243028). The quantification of the immunostaining was performed by three observers using a Multivision microscope. Results were expressed as a percentage of immunostained cells (29).

Evaluation of Ki-67 LI (monoclonal 30-9, Ventana) proliferative activity was performed in complete sections on two hot spots, quantifying at each spot at least 500 cells and considering any intensity of nuclear staining to be positive. Results are expressed as a percentage, considering Ki-67 proliferation of 3% or more to be high. For the study of cytokeratins (monoclonal rabbit antihuman cytokeratin 8/ 18, clone EP17/EP30; Dako-Agilent), we examined the stain pattern (dot-like or perinuclear), defining tumours as positive when at least 5% of the cells were stained. We performed IHC assays, except for pituitary transcription factors, following a routine staining method using a streptavidin-biotin system (LSABþ, ChemMate Detection Kit 5301 Stevens Creek Blvd. Santa Clara, CA, 95051, United States) by using a Dako-OMNIS automated staining platform (Dako-Agilent) (29).

Classification of tumours

All tumours were classified based on a combination of criteria: MRI features (tumour size and invasion), pituitary tumour subtypes according to the 2017 WHO classification based on protein (IHC) expression of pituitary transcription factors and adenohypophyseal hormones, and Ki-67 LI. The immunostaining of transcription factors enabled us to reduce the percentage of null cell tumours to 6% of our series. We counted mitotic changes and determined the expression of p53 only in patients with Ki-67 of 3% or more. We considered a tumour to be proliferative when its Ki-67 LI was over that cutoff. It was not possible to assess the invasion of the dura matter in all patients, so this criterion was not considered.

PitNETs were classified on the first surgery as grade 1a (non-invasive), grade 1b (non-invasive and proliferative), grade 2a (invasive), grade 2b (invasive and proliferative), and grade 3 (pituitary carcinoma), according to Trouillas et al.’s proposal (18) (Table 1).

Criteria for recurrence/progression

This study aimed to analyse the predictors of recurrence associated with PitNETs. We defined complete remission as the total absence of pituitary disease at the clinical, hormonal, and radiological levels. Recurrence/progression was defined as a newly identified disease after total resection or enlargement of remnant tumour of at least 20% (progression) or proven hormonal relapse in functioning tumours during the follow-up. To simplify the analysis, we pooled recurrence and progression into one term.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were compared using the chi-squared and Fisher exact tests. Data with a normal distribution were compared using the student T test or analysis of variance, and nonparametric data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test. Values were expressed as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Spearman’s and Pearson’s correlation tests were used for continuous variables with or without normal distribution, respectively. Progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The PFS curves obtained for grades were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate PFS analysis was performed using a Cox regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 20.0 (IBM Corp, NY, USA).

3. Results

Clinical, pathological, and radiological characteristics

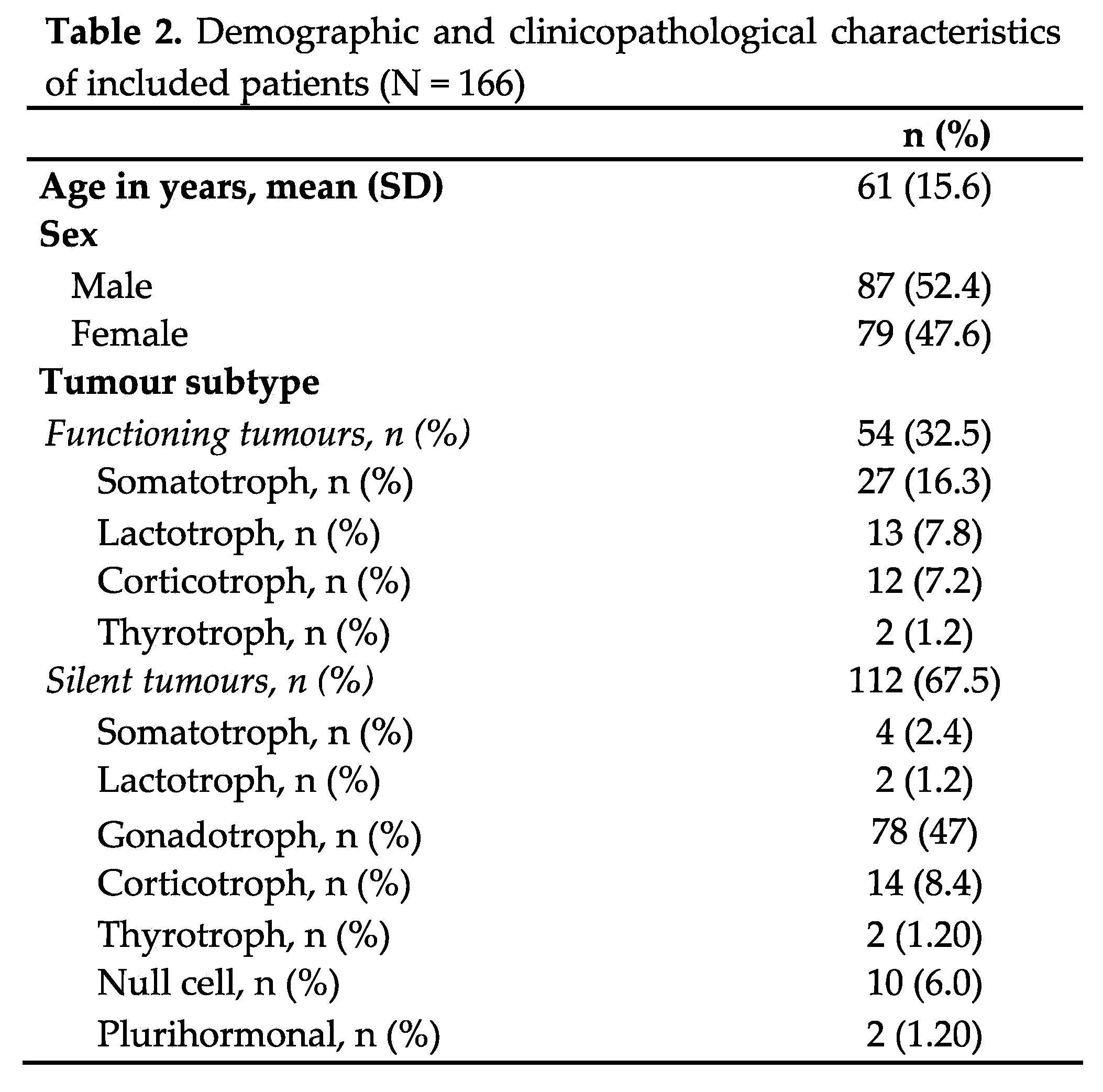

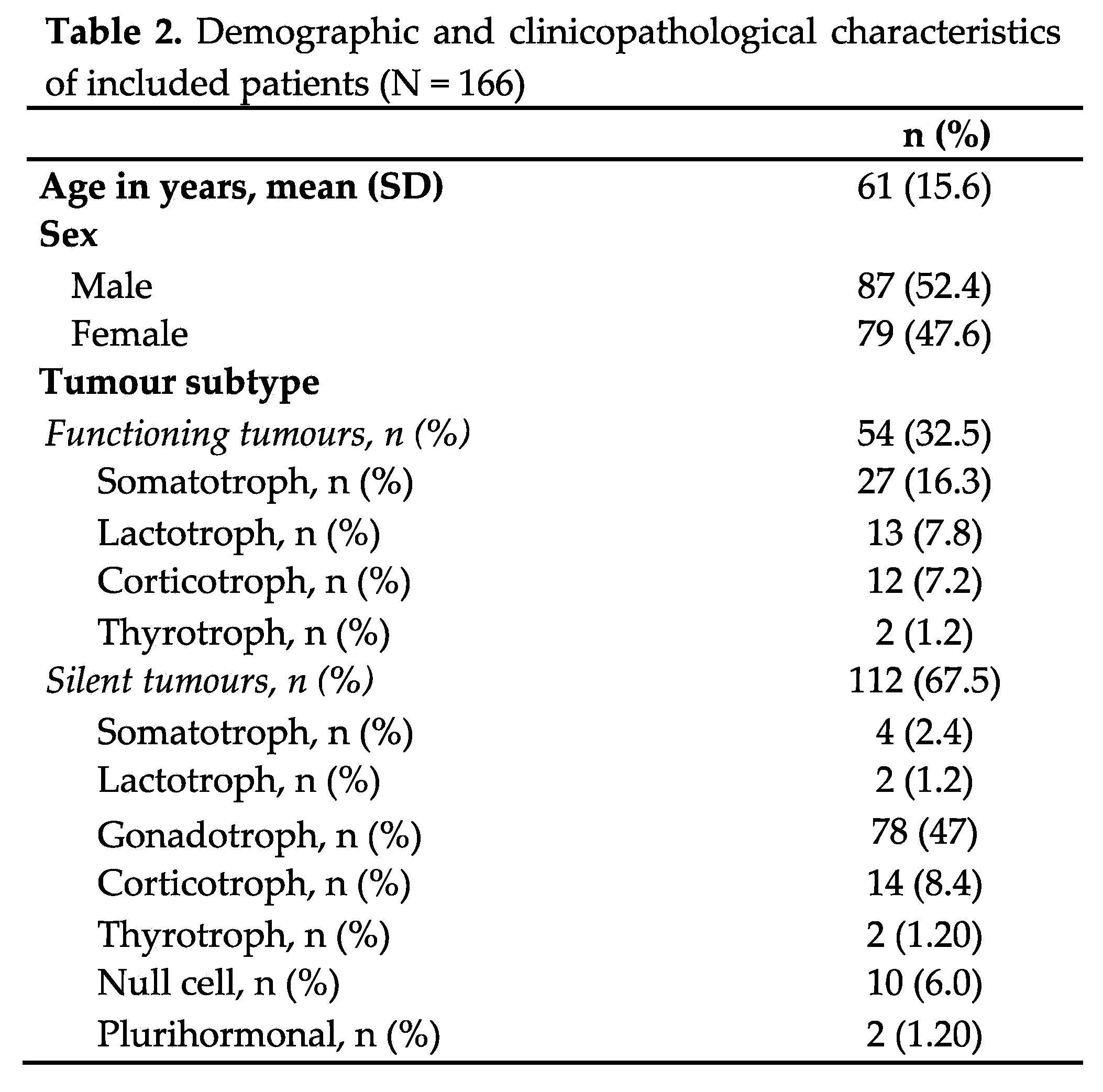

Table 2 summarises the demographic, clinical characteristics, and tumour pituitary subtypes of the included patients. Patients’ mean age at the time of data collection was 61 years (SD 15.6), and they were followed for a mean of 57.8 months (SD 30). The histopathological study of transcription factors enabled the identification of all tumours, with only 6% classified as null cell and 1% as plurihormonal tumours (Table 2). All tumours with a positive IHC for adenohypophyseal hormones and transcription factors that did not express a clinical or biochemical recognisable endocrine syndrome were typified as silent counterparts of functioning tumours. All functioning corticotroph and lactotroph tumours were treated neoadjuvantly with ketoconazole or cabergoline, respectively. Following surgery, seven functioning somatotroph tumours, nine functioning lactotroph tumours, two functioning thyrotroph tumours, and two functioning corticotroph tumours continued receiving treatment due to persistent hormone hypersecretion. Additionally, two of the functioning corticotroph tumours received radiation therapy. Bottom of Form

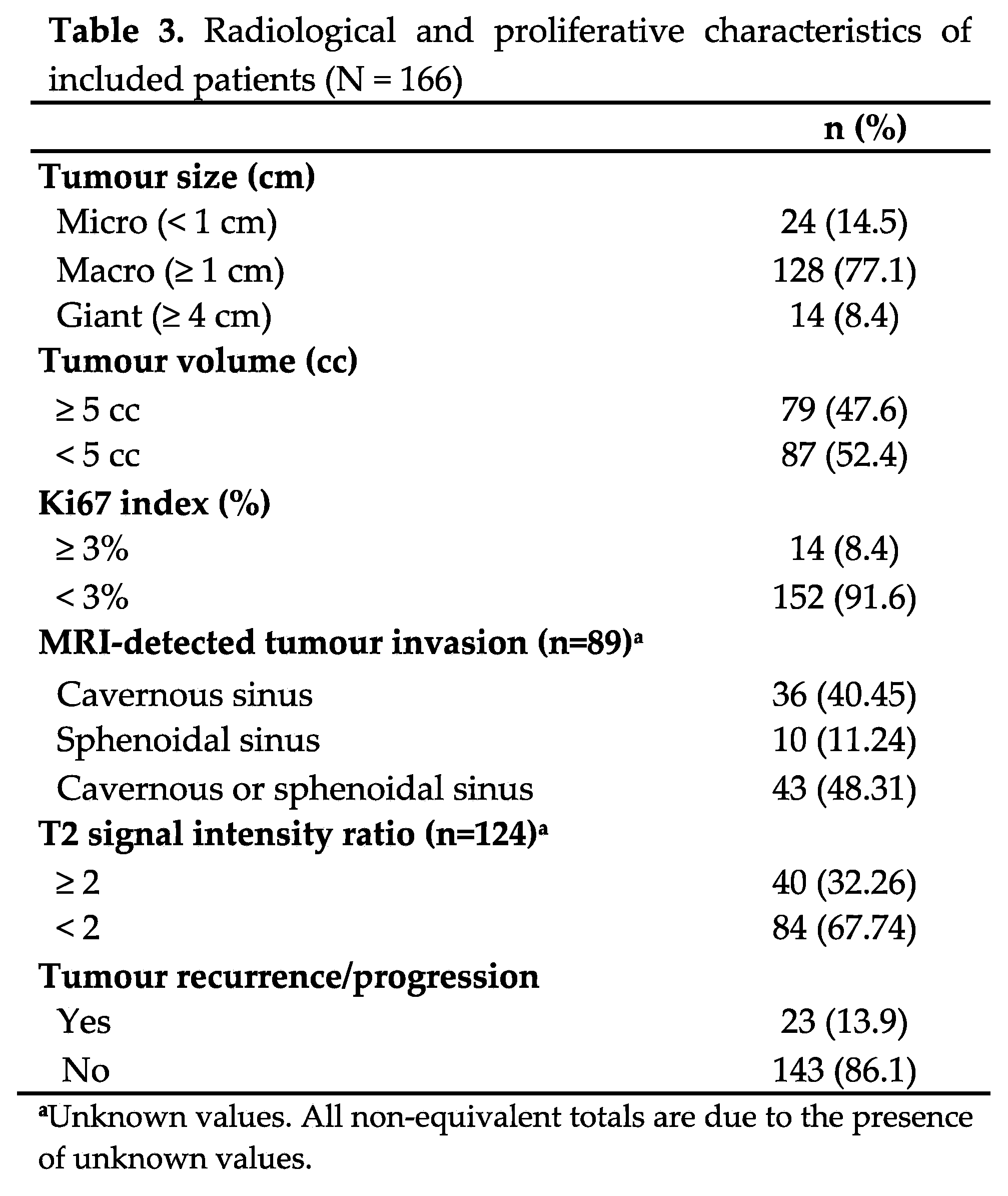

Table 3 shows the radiological and proliferative characteristics and recurrence of the PitNETs. Most tumours were non-proliferative, nearly half were invasive, and almost a third had a T2 SIR of 2 or more. Only 23 patients had a recurrence over follow-up. A single pituitary carcinoma (somatotroph origin) was diagnosed several years after diagnosis because of cerebral metastasis.

Clinicopathological classification of the PitNETs

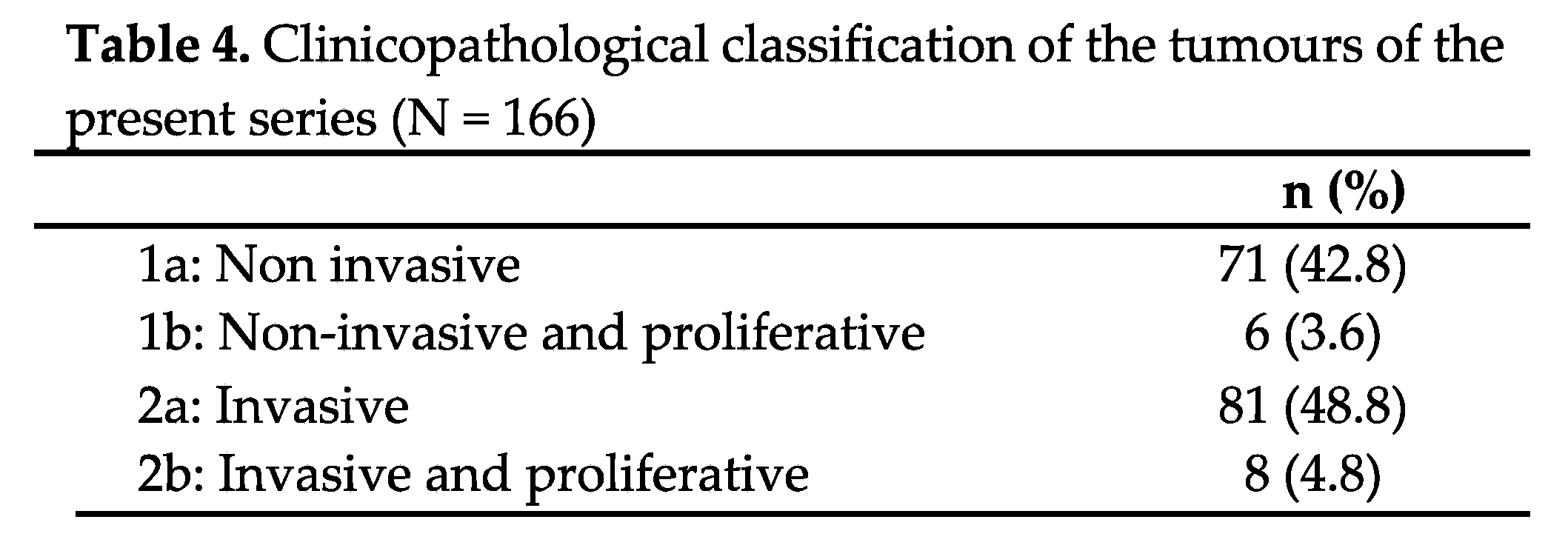

According to the clinicopathological classification, 48.8% of the tumours were invasive and non-proliferative (grade 2a), and 42.8% were non-invasive and non-proliferative (grade 1a) (Table 4).

Recurrence

At the last follow-up visit, 23 (13.9%) pituitary tumours showed recurrence (22 silent pituitary tumours and 1 functioning tumour). Of these, 3 (13.04%) underwent gross total resection during the first surgery, while the 20 (87%) underwent subtotal resection. No patient underwent debulking. None of the functioning tumours cured by surgery showed recurrence. Among those that were not cured by surgery and needed medical or radiotherapy for the control of the disease, only one progressed over follow-up, a pituitary carcinoma that progressed to a fatal cerebral metastasis five years after diagnosis.

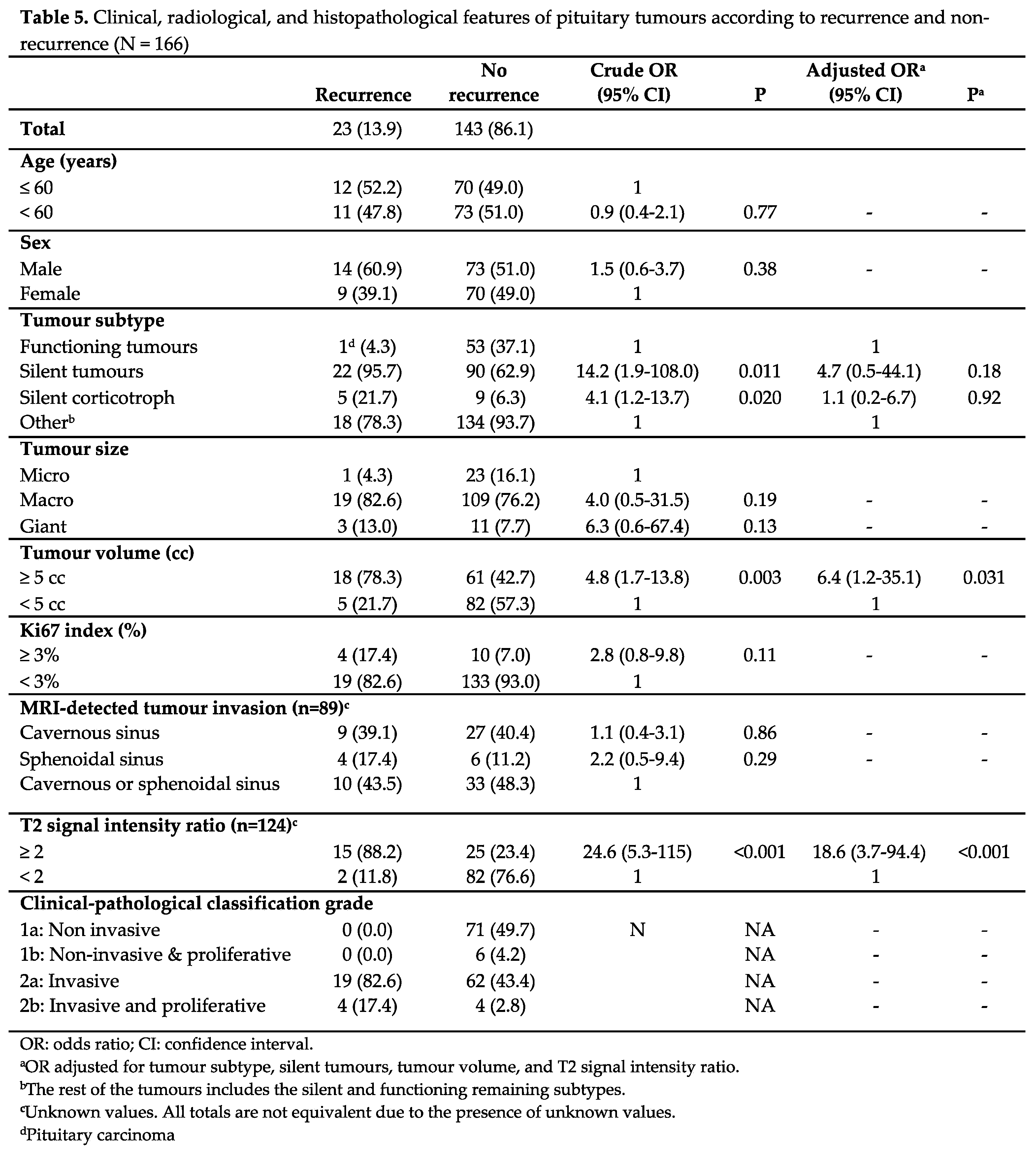

Univariate and multivariate analysis

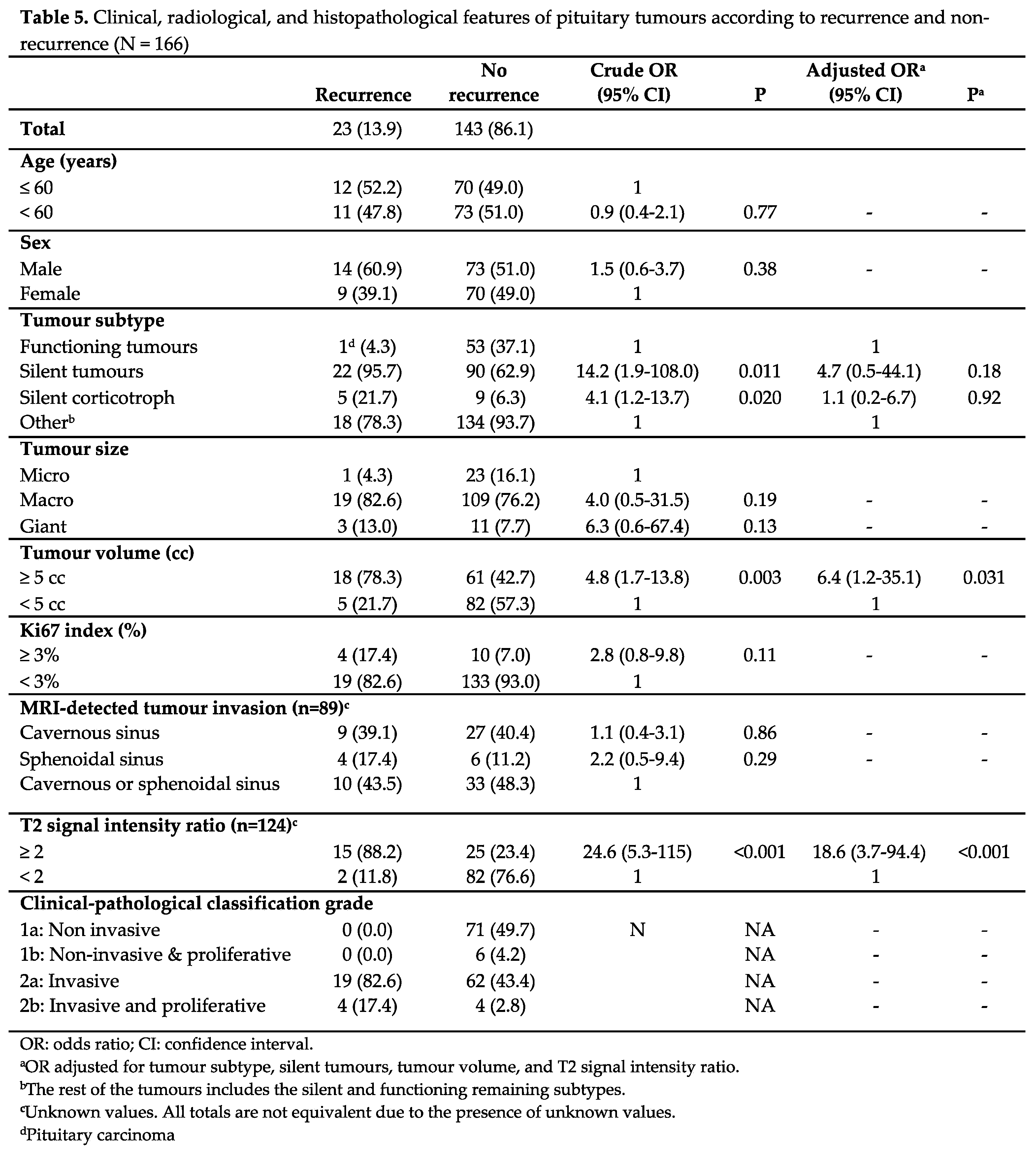

The results of the analysis of the factors associated with recurrence are shown in Table 5. In the crude analysis, tumour subtype, silent corticotroph adenoma subtype (SCAs), tumour volume, and T2 SIR were significantly associated with recurrence (p < 0.05). In the multivariate analysis, significance held only for T2 SIR of 2 or more (p < 0.001) and tumour volume of 5 cc or more (p = 0.031) (Table 5, Figure 1).

Progression-free survival

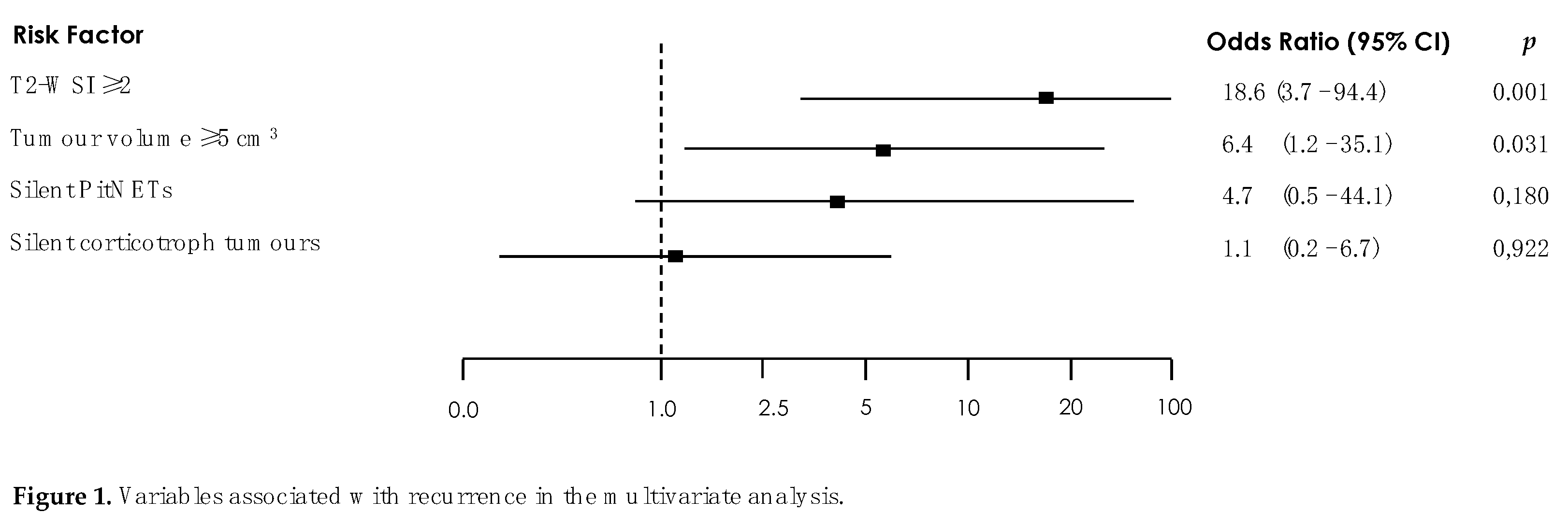

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 depicts the Kaplan-Meier PFS curves for different tumour characteristics. Only the silent corticotroph tumour (

Figure 2a) and those with T2 SIR of 2 or more (

Figure 2b) exhibited a significant reduction in PFS (p < 0.05). Following Trouillas et al.’s clinicopathological classification (18) (

Figure 3), invasive (2a) and invasive/proliferative (2b) tumours clearly exhibited lower PFS compared to non-invasive/non-proliferative (1a) and proliferative/non-invasive tumours (1b). Unfortunately, we were unable to perform a statistical analysis as none of the non-invasive (1a) or non-invasive/proliferative (1b) tumours recurred. None of the rest analysed variables were related with recurrence.

Table 6.

Published studies assessing clinicopathological classification using Trouillas’ grading in patients with pituitary tumours.

Table 6.

Published studies assessing clinicopathological classification using Trouillas’ grading in patients with pituitary tumours.

| |

|---|

| |

Present study

(N = 166) |

Trouillas et al. 2013(18) (N = 410) |

Raverot et al. 2017(19) (N = 374) |

Sahakian et al. 2022(24) (N = 607) |

Liang et al. 2018(20)

(N = 270) |

Asioli et al. 2019(23)

(N = 566) |

Lelotte et al. 2018(21) (N = 120) |

Guaraldi et al. 2020(22) (N = 1066) |

| Centre |

Single centre |

Multicentre |

Single centre |

Single centre |

Single centre |

Single centre |

Single centre |

Single centre |

| Follow-up |

2013-2023 |

1987-2004 |

2007-2012 |

2008-2018 |

2008-2016 |

1998-2012 |

2004-2014 |

1998-2018 |

| Median follow-up |

57.8 months |

11.14 years |

3.5 years |

38 months |

44 months |

5.8 years |

48 months |

59.3 months |

| NFPAs |

114 |

ND |

ND |

320 |

212 |

253 |

120 |

ND |

| N patients classified according to Trouillas' grade |

|

| 1a |

71 |

194 |

109 |

303 |

126 |

378 |

39 |

685 |

| 1b |

6 |

41 |

18 |

53 |

25 |

59 |

13 |

151 |

| 2a |

81 |

113 |

82 |

202 |

95 |

87 |

50 |

172 |

| 2b |

8 |

62 |

26 |

49 |

24 |

42 |

18 |

58 |

| N recurrence/progression |

23 |

215 |

89 |

127 |

77 |

60 |

38 |

116 |

| Crude association with recurrence/progression (univariate analysis) |

Tumour volume, T2 SIR, functioning subtype, silent corticotroph tumour |

ND |

ND |

Age, tumour size (macro), MRI invasion, tumour subtype, grade |

Diameter, volume, invasiveness, high-risk subtype, proliferation, GTR |

PitNETs subtype (ACTH/PRL/FSH-LH); 1b, 2b and diameter > 1 cm) |

Grade |

Histological type, sinus invasion, ki-67, mitoses, p53, grade |

| Independent association with recurrence/ progression (multivariate analysis) |

T2 SIR, tumour volume |

Age, tumour diameter, grade, tumour subtype |

Grade, tumour subtype, age |

Age, MRI invasion, tumour subtype, grade |

Diameter, volume, proliferation potential, GTR |

Tumour subtype and grade |

Young age, proliferative character, residual tumour, duration of follow-up |

Histological tumour subtype, and grade |

| Factors impacting progression-free survival |

Tumour subtype, T2 SIR*, grade 2a, 2b |

Grade 2a, 2b* |

Grade 2a, 2b* |

Grade 2b* |

Grade 1b, 2a, 2b* |

Grade 1b, 2b*, tumour subtype |

Grade 2b |

Grade (1b,2a,2b)*, and tumour subtype |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

11.6 (2.6-52.1)* |

12-fold* |

3.72 (1.9-7.26)* |

4.8 (1.85-11.29)* |

20.1 (7.12-56.67)* |

5.0 (3.03-8.26)* |

8.6 (2.39-31.3) |

10.45* |

| * The hazard ratio value corresponding to the analyzed data within the same study group

|

4. Discussion

This study presents the first Spanish series of pituitary tumours investigated using the clinicopathological classification proposed by Trouillas et al. in 2013 (18). Over a 10-year follow-up of 166 patients in a centre of excellence, we confirmed that patients classified as type 2a (invasive tumours), and especially type 2b (invasive/proliferative tumours) exhibited lower progression-free survival (PFS) compared to those with non-invasive/non-proliferative (1a) or proliferative/non-invasive tumours (1b). Moreover, patients with silent corticotroph tumours and those with a T2 signal intensity ratio of 2 or more on MRI exhibited a significant reduction in PFS.

The paper has some strengths: all cases came from a single centre and were managed by the same team of endocrinologists, radiologists, neurosurgeons, and pathologists. In addition, all the tumours were classified according to the expression of pituitary transcription factors, which significantly reduced the percentages of null cell and plurihormonal subtypes (28,29). This aspect gives our series an important advantage over most other series published to date. These validated the clinical pathological classification without clarifying which tumours were truly null cell and plurihormonal Pit-1-positive, as pituitary transcription factors were not routinely analysed when they reported their results. Moreover, our mean follow-up was 57.8 (SD 30) months, greater than some other studies.

The study also has limitations. We did not regularly determine the gene or protein expression of p53 or the mitotic index. We evaluated these parameters only in cases with Ki-67 LI of 3% or more. Although the 2004 WHO classification considered the expression of p53 and a high mitotic index as an effective prognostic marker of PitNETs (1), we consider that these tumours are scarcely proliferative, and the expression of p53 and mitotic index adds little information to the Ki-67 determination. Moreover, the prognostic value of immunopositivity for p53 is also debatable because there is no reliable method of quantification (4). Indeed, no study has shown a relationship between p53 expression alone and recurrence or progression (5,6,9).

The use of the Ki-67 LI to define proliferation is also controversial. The prevalence of proliferative tumours according to Ki-67 LI oscillates widely, from 3% in Miermesiter et al.’s series (7) to 13% in Tortosa et al.’s (10). These discrepancies are likely explained by the different cutoffs used, ranging from 1% to 5 (31,32) and by technical differences in the immunohistochemical detection of proliferation marker positivity. In our study, Ki-67 expression was assessed by the same pathologist and checked by its gene expression (qPCR), and we adopted the standards proposed by Trouillas, Ki-67 LI ≥ 3% (18).

Another point of discussion is the definition of the term “invasiveness”. A systematic literature review on pituitary adenomas and invasiveness (33) concluded that it was necessary to distinguish truly invasive PitNETs from those that present with extension in the parasellar area through natural pathways. The authors recommend basing the diagnosis of invasiveness on radiological, intraoperative, and histological findings. However, most published series, including ours, have applied a strictly radiological definition of invasiveness, and that may explain the heterogeneity of results.

Finally, while it is easy to look for the natural evolution of silent tumours if irradiated tumours are excluded, it is more difficult to analyse the biological behaviour of functioning tumours. It is rare that a functioning pituitary tumour relapses/recurs after successful surgery, and all functioning pituitary tumours not cured with surgery are under medical treatment, which alters their functionality and growth. Therefore, these tumours need to be analysed one by one. Indeed, in our series, only one functioning tumour – a malignant somatotroph tumour – was not controlled under medical treatment.

Historically, PitNETs have been classified according to the recommendations of the successive editions of the WHO Classification of Pituitary Tumours. The 2004 WHO classification considered high mitotic index, Ki-67 LI ≥ 3 % and the expression of p53 as effective prognostic markers of PitNETs. The two most recent editions, from 2017 and 2022, have introduced some changes: the term ‘atypical tumour’ has disappeared, and the entity previously known as adenoma is now considered a pituitary neuroendocrine tumour. However, neither of these classifications considered the tumours’ clinical aspects as anticipating their potentially aggressive behaviour.

In 2013, Jaqueline Trouillas et al. proposed a clinicopathological classification to overcome these drawbacks (18). By studying 410 PitNETs from several centres in France over a 10-year follow-up and considering radiological invasion and proliferative indexes, the authors were able to identify tumours with a high risk of aggressiveness (recurrence/relapse). Since then, several clinical series have been published validating these results, including the present work (

Table 6).

The methodology of all the studies has been very similar, differing only in the number of the tumours included and the length of follow-up. All series except Lelotte et al.’s (21) included both functioning and silent tumours, and PitNET subtypes were consistently identified according to the immunostaining of adenohypophyseal hormones. Only Guaraldi et al. (22) analysed the transcription factors but in only 65 tumours that were immune-negative for pituitary hormones. Most series defined invasion on MRI according to Knosp’s criteria (17), and all defined proliferation according to a Ki-67 LI of 3% or more, although some series also take into account the other proliferation indexes. In our series, all tumours were identified according to transcription factors expression, and proliferation was defined using radiological criteria of invasiveness and Ki-67% LI.

As seen in

Table 6, all the published series demonstrated that grade 2a, and especially 2b tumours, carry a significantly higher risk or recurrence/progression compared to grade 1a tumours. However, while all authors agree that invasion is the main predictor of recurrence or progression, questions remain regarding the relevance of proliferation without invasion (grade 1b). Only Lelotte and Liang et at. (20,21), found that the proliferative capability of PitNETs was an independent risk factor for disease progression. Both studies defined proliferation according to Ki-67 LI, mitotic index and p53 expression. In our series all the recurrent tumours were 2a (recurrence rate 23%) and 2b (recurrence rate 50%) (Table 5,

Figure 3). These results support the role of invasion as the most important predictor of recurrence. Indeed, we found that the only two independent risk factors of recurrence in the multivariate analysis were a tumour volume, clearly related to invasion (odds ratio [OR] 6.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2-35.1, p=0.031) and a T2 SIR of 2 or more (OR 18.6, 95% CI 3.7-94.4, p < 0.001).

Another a risk factor for recurrence in PitNETs had to do with IHC. The successive WHO classifications consider that some subtypes of PitNETs have a higher risk of recurrence, including the silent corticotroph subtype. In fact, data from 11 case-control studies suggest higher recurrences in SCAs compared to non-functioning pituitary adenomas (NFAs), supporting the view that SCAs present a more aggressive clinical course (34–42).

However, there are discrepancies about the different behaviour of pituitary tumour subtypes. In their original paper (18), Trouillas et al. found that patient status at eight years of follow-up was associated with tumour grade in both the whole series and in the different PitNET subtypes. The effect of invasion was much higher for lactotroph and corticotroph tumours than for gonadotroph and somatotroph tumours. In contrast, in the series they published four years later (43), lactotroph and somatotroph tumour subtypes behaved worse than gonadotroph and corticotroph tumours in the PFS curves. Conversely, Asioli et al. (23) found that the risk of recurrence/progression was significantly higher in tumours secreting adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) compared to those secreting growth hormone (GH). These results were later confirmed by the same group (22), establishing the corticotroph subtype as an independent risk factor for recurrence/progression, and by Shakalian et al. (24), who found a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.1 for ACTH tumours and of 0.57 for somatotroph tumours.

Similarly, we observed that silent corticotroph tumours had a 4-fold, (95% CI 1.2-13.7, p=0.020) (Table 5) risk of recurrence. Moreover, PFS was significantly lower than for other subtypes (HR 3.8, 95% CI 1.3-10.5, p=0.012) (

Figure 2a). Therefore, in line with the WHO classification of PitNETs, the IHC subtype should be taken into consideration along with the proliferative indexes and the radiological characteristics when estimating the risk of recurrence.

Furthermore, MRI is not only important to evaluate the existence of invasion. Recent technological advances also allow to evaluate the biological characteristics of PitNETs. Their intensity on T2-weighted images has been related to the fibrous or microcystic content as well as tumour cellularity (13,14). These characteristics are determinants of the outcome of the first surgery and the recurrence/progression of tumours. However, to date few studies have investigated the relationship between the information obtained from T2-weighted images on MRI and tumour recurrence.

In 2020, Conficoni et al. (14) studied a small series of 17 PitNETs, finding a statistically significant difference between the enhancement ratio and Ki-67 expression. In the same year, Liu et al. (16) conducted a retrospective analysis of T1- and T2-weighted MRI scans of 47 PitNETs, reporting a significant correlation between T2 tumour signal intensity /white matter signal and invasion and recurrence. Later, in 2023 Calandrelli et al. (13) observed that T2 SIR values showed significant differences among Trouillas’ tumour grades. Specifically, T2 maximum intensity values were significantly higher in higher-grade tumours.

In the previous studies, the T2 ratio was calculated by dividing the signal intensity of the tumour by that of the white matter in the temporal lobe (13,15). However, this approach may have some associated limitations, particularly with regard to intensity variations in the supratentorial white matter substance. A myriad of factors, including inflammatory, infectious, metabolic, or neurodegenerative diseases, may influence these variations (44), so T2 intensity ratios should be interpreted with caution, and further research to validate their reliability in specific clinical scenarios is warranted.

In our series, we measured T2 signal intensity by comparing the tumour's signal with that of the corpus callosum. We found that T2 signal intensity values of 2 or more were associated with a significantly higher risk of recurrence (OR 18.6, 95% CI 3.7-94.4). While it is true that some diseases may also influence the intensity of the corpus callosum on T2 SIR MRI sequences, these conditions are less common than those affecting the lobar white substance, which is mainly related to uncommon demyelination syndromes (45).

5. Conclusions

Our results add more evidence to the post-surgery prognostic value of the five-grade classification of pituitary tumours. The silent corticotroph subtype emerges as a risk group, supporting higher clinical surveillance of these patients. Finally, our MRI findings highlight the increasing value of radiological evaluation in the management of PitNETs.

Funding

This research did receive funding from the Institute of Health and Biomedical Research (ISABIAL), Alicante, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and other applicable laws and received the approval of the local ethics committee (CEIm reference number: PI2018/127, date: 08 October 2018, Alicante General University Hospital). This retrospective monocentric observational design did not require a written consent by the patients according to the Spanish legislation.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Shraim M, Asa SL. The 2004 World Health Organization classification of pituitary tumors: What is new? Acta Neuropathol. 2006 Jan 23;111(1):1–7.

- Mete O, Lopes MB. Overview of the 2017 WHO Classification of Pituitary Tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2017 Sep 1;28(3):228–43.

- Asa SL, Mete O, Perry A, Osamura RY. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Pituitary Tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2022 Mar 15;33(1):6–26.

- Di Ieva A, Rotondo F, Syro L V., Cusimano MD, Kovacs K. Aggressive pituitary adenomas—diagnosis and emerging treatments. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 Jul 13;10(7):423–35.

- Hentschel SJ, McCutcheon IE, Moore W, Durity FA. p53 and MIB-1 Immunohistochemistry as Predictors of the Clinical Behavior of Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 2003 Aug 2;30(3):215–9.

- Gejman R, Swearingen B, Hedley-Whyte ET. Role of Ki-67 proliferation index and p53 expression in predicting progression of pituitary adenomas. Hum Pathol. 2008 May;39(5):758–66.

- Miermeister CP, Petersenn S, Buchfelder M, Fahlbusch R, Lüdecke DK, Hölsken A, et al. Histological criteria for atypical pituitary adenomas – data from the German pituitary adenoma registry suggests modifications. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015 Dec 19;3(1):50.

- Jaffrain-Rea ML, Di Stefano D, Minniti G, Esposito V, Bultrini A, Ferretti E, et al. A critical reappraisal of MIB-1 labelling index significance in a large series of pituitary tumours: secreting versus non-secreting adenomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2002 Jun;103–13.

- Zada G, Woodmansee WW, Ramkissoon S, Amadio J, Nose V, Laws ER. Atypical pituitary adenomas: incidence, clinical characteristics, and implications. J Neurosurg. 2011 Feb;114(2):336–44.

- Tortosa F, Webb SM. Atypical pituitary adenomas: 10 years of experience in a reference centre in Portugal. Neurología (English Edition). 2016 Mar;31(2):97–105.

- Saeger W, Lüdecke DK, Buchfelder M, Fahlbusch R, Quabbe HJ, Petersenn S. Pathohistological classification of pituitary tumors: 10 years of experience with the German Pituitary Tumor Registry. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007 Feb;156(2):203–16.

- Heaney AP. Pituitary Carcinoma: Difficult Diagnosis and Treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Dec 1;96(12):3649–60.

- Calandrelli R, Pilato F, D’Apolito G, Schiavetto S, Gessi M, D’Alessandris QG, et al. MRI and Trouillas’ grading system of pituitary tumors: the usefulness of T2 signal intensity volumetric values. Neuroradiology. 2023 May 26;

- Conficoni A, Feraco P, Mazzatenta D, Zoli M, Asioli S, Zenesini C, et al. Biomarkers of pituitary macroadenomas aggressive behaviour: a conventional MRI and DWI 3T study. Br J Radiol. 2020 Sep 1;93(1113):20200321.

- Ko CC, Chang CH, Chen TY, Lim SW, Wu TC, Chen JH, et al. Solid tumor size for prediction of recurrence in large and giant non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2022 Apr 4;45(2):1401–11.

- Liu H, Zhang Q, Hang W, Liu G. [Analysis of correlation between magnetic resonance imaging features and prognosis of invasive pituitary adenoma]. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020 Oct 7;55(10):926–33.

- Knosp E, Steiner E, Kitz K, Matula C. Pituitary Adenomas with Invasion of the Cavernous Sinus Space. Neurosurgery. 1993 Oct;33(4):610–8.

- Trouillas J, Roy P, Sturm N, Dantony E, Cortet-Rudelli C, Viennet G, et al. A new prognostic clinicopathological classification of pituitary adenomas: a multicentric case–control study of 410 patients with 8 years post-operative follow-up. Acta Neuropathol. 2013 Jul 12;126(1):123–35.

- Raverot G, Dantony E, Beauvy J, Vasiljevic A, Mikolasek S, Borson-Chazot F, et al. Risk of Recurrence in Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Prospective Study Using a Five-Tiered Classification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Sep 1;102(9):3368–74.

- Lv L, Yin S, Zhou P, Hu Y, Chen C, Ma W, et al. Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics Predicted the Postoperative Recurrence and Progression of Pituitary Adenoma: A Retrospective Study with 10 Years Follow-Up. World Neurosurg. 2018 Oct 1;118:e428–35.

- Lelotte J, Mourin A, Fomekong E, Michotte A, Raftopoulos C, Maiter D. Both invasiveness and proliferation criteria predict recurrence of non-functioning pituitary macroadenomas after surgery: a retrospective analysis of a monocentric cohort of 120 patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;178(3):237–46.

- Guaraldi F, Zoli M, Righi A, Gibertoni D, Marino Picciola V, Faustini-Fustini M, et al. A practical algorithm to predict postsurgical recurrence and progression of pituitary neuroendocrine tumours ( PitNET )s. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020 Jul 5;93(1):36–43.

- Asioli S, Righi A, Iommi M, Baldovini C, Ambrosi F, Guaraldi F, et al. Validation of a clinicopathological score for the prediction of post-surgical evolution of pituitary adenoma: retrospective analysis on 566 patients from a tertiary care centre. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019 Feb;180(2):127–34.

- Sahakian N, Appay R, Resseguier N, Graillon T, Piazzola C, Laure C, et al. Real-life clinical impact of a five-tiered classification of pituitary tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022 Dec 1;187(6):893–904.

- Daly AF, Beckers A. The Epidemiology of Pituitary Adenomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2020 Sep;49(3):347–55.

- Frara S, Rodriguez-Carnero G, Formenti AM, Martinez-Olmos MA, Giustina A, Casanueva FF. Pituitary Tumors Centers of Excellence. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2020 Sep;49(3):553–64.

- García-Martínez A, Sottile J, Fajardo C, Riesgo P, Cámara R, Simal JA, et al. Is it time to consider the expression of specific-pituitary hormone genes when typifying pituitary tumours? PLoS One. 2018 Jul 6;13(7):e0198877.

- Torregrosa-Quesada ME, García-Martínez A, Silva-Ortega S, Martínez-López S, Cámara R, Fajardo C, et al. How Valuable Is the RT-qPCR of Pituitary-Specific Transcription Factors for Identifying Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumor Subtypes According to the New WHO 2017 Criteria? Cancers (Basel). 2019 Dec 11;11(12):1990.

- Silva-Ortega S, García-Martinez A, Niveiro de Jaime M, Torregrosa ME, Abarca J, Monjas I, et al. Proposal of a clinically relevant working classification of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors based on pituitary transcription factors. Hum Pathol. 2021 Apr;110:20–30.

- Torregrosa-Quesada ME, García-Martínez A, Sánchez-Barbie A, Silva-Ortega S, Cámara R, Fajardo C, et al. The silent variants of pituitary tumors: demographic, radiological and molecular characteristics. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021 Aug 21;44(8):1637–48.

- Mastronardi L, Guiducci A, Spera C, Puzzilli F, Liberati F, Maira G. Ki-67 labelling index and invasiveness among anterior pituitary adenomas: analysis of 103 cases using the MIB-1 monoclonal antibody. J Clin Pathol. 1999 Feb 1;52(2):107–11.

- Glebauskiene B, Liutkeviciene R, Vilkeviciute A, Gudinaviciene I, Rocyte A, Simonaviciute D, et al. Association of Ki-67 Labelling Index and IL-17A with Pituitary Adenoma. Biomed Res Int. 2018 May 31;2018:1–7.

- Serioli S, Doglietto F, Fiorindi A, Biroli A, Mattavelli D, Buffoli B, et al. Pituitary Adenomas and Invasiveness from Anatomo-Surgical, Radiological, and Histological Perspectives: A Systematic Literature Review. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Dec 4;11(12):1936.

- Bradley KJ, Wass JAH, Turner HE. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas with positive immunoreactivity for ACTH behave more aggressively than ACTH immunonegative tumours but do not recur more frequently. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003 Jan;58(1):59–64.

- Ioachimescu AG, Eiland L, Chhabra VS, Mastrogianakis GM, Schniederjan MJ, Brat D, et al. Silent Corticotroph Adenomas. Neurosurgery. 2012 Aug;71(2):296–304.

- Cooper O, Ben-Shlomo A, Bonert V, Bannykh S, Mirocha J, Melmed S. Silent Corticogonadotroph Adenomas: Clinical and Cellular Characteristics and Long-Term Outcomes. Horm Cancer. 2010 Apr 28;1(2):80–92.

- Langlois F, Lim DST, Yedinak CG, Cetas I, McCartney S, Cetas J, et al. Predictors of silent corticotroph adenoma recurrence; a large retrospective single center study and systematic literature review. Pituitary. 2018 Feb 14;21(1):32–40.

- Cho HY, Cho SW, Kim SW, Shin CS, Park KS, Kim SY. Silent corticotroph adenomas have unique recurrence characteristics compared with other nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010 May;72(5):648–53.

- Jahangiri A, Wagner JR, Pekmezci M, Hiniker A, Chang EF, Kunwar S, et al. A Comprehensive Long-term Retrospective Analysis of Silent Corticotrophic Adenomas vs Hormone-Negative Adenomas. Neurosurgery. 2013 Jul;73(1):8–18.

- Pawlikowski M, Kunert-Radek J, Radek M. “Silent”corticotropinoma. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2008 Jun;29(3):347–50.

- Alahmadi H, Lee D, Wilson JR, Hayhurst C, Mete O, Gentili F, et al. Clinical features of silent corticotroph adenomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2012 Aug 24;154(8):1493–8.

- Cohen-Inbar O, Xu Z, Lee C chia, Wu CC, Chytka T, Silva D, et al. Prognostic significance of corticotroph staining in radiosurgery for non-functioning pituitary adenomas: a multicenter study. J Neurooncol. 2017 Oct 14;135(1):67–74.

- Raverot G, Vasiljevic A, Jouanneau E, Trouillas J. A Prognostic Clinicopathologic Classification of Pituitary Endocrine Tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015 Mar;44(1):11–8.

- Sureka J, Jakkani RK. Clinico-radiological spectrum of bilateral temporal lobe hyperintensity: a retrospective review. Br J Radiol. 2012 Sep;85(1017):e782–92.

- Kazi AZ, Joshi PC, Kelkar AB, Mahajan MS, Ghawate AS. MRI evaluation of pathologies affecting the corpus callosum: A pictorial essay. Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging. 2013 Oct 30;23(04):321–32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).