Submitted:

16 August 2023

Posted:

17 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

History of the relationship between heart and thyroid

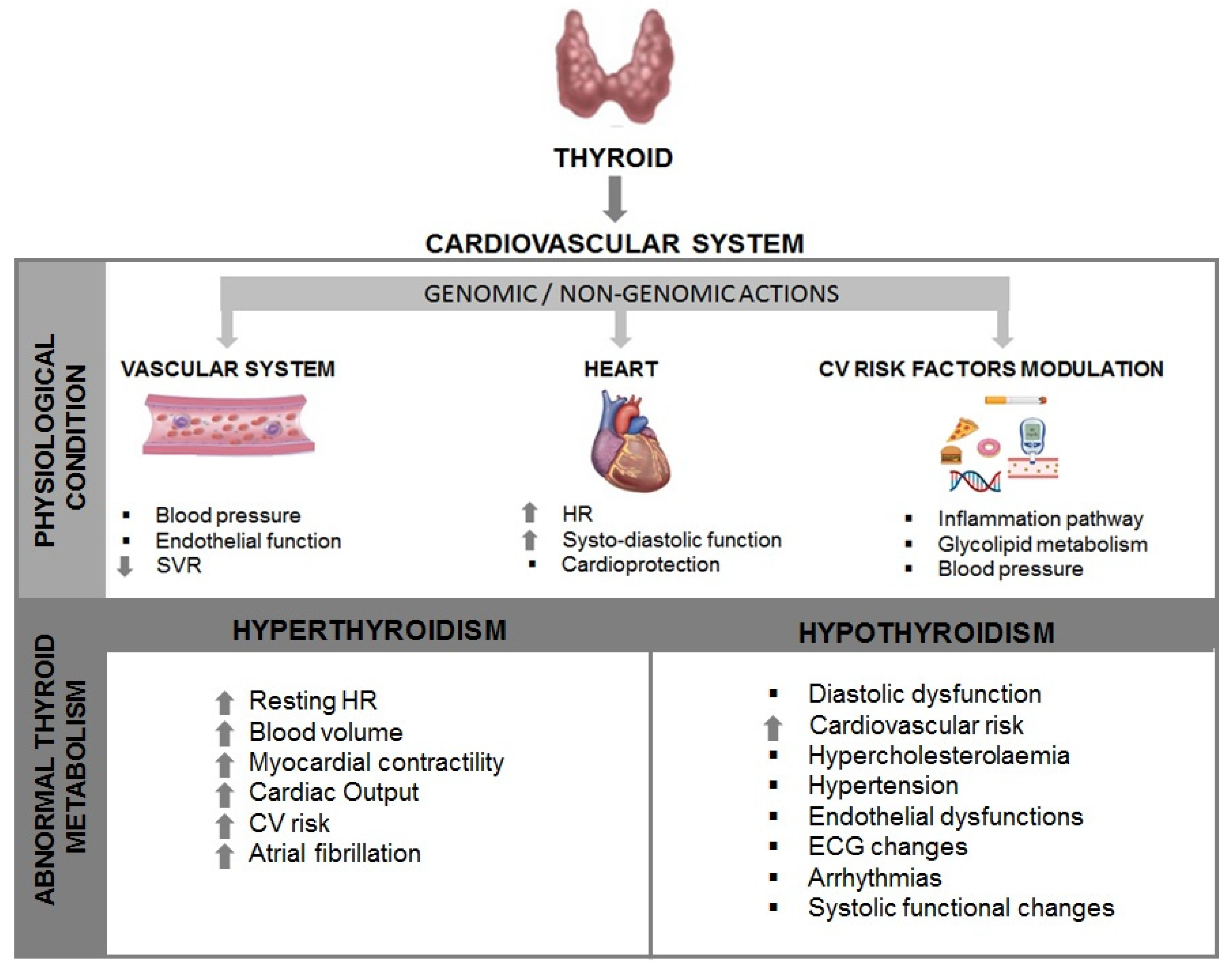

Thyroid and heart: a tight physiological relation

Hyperthyroidism, Hyporthyroidism and Subclinical conditions

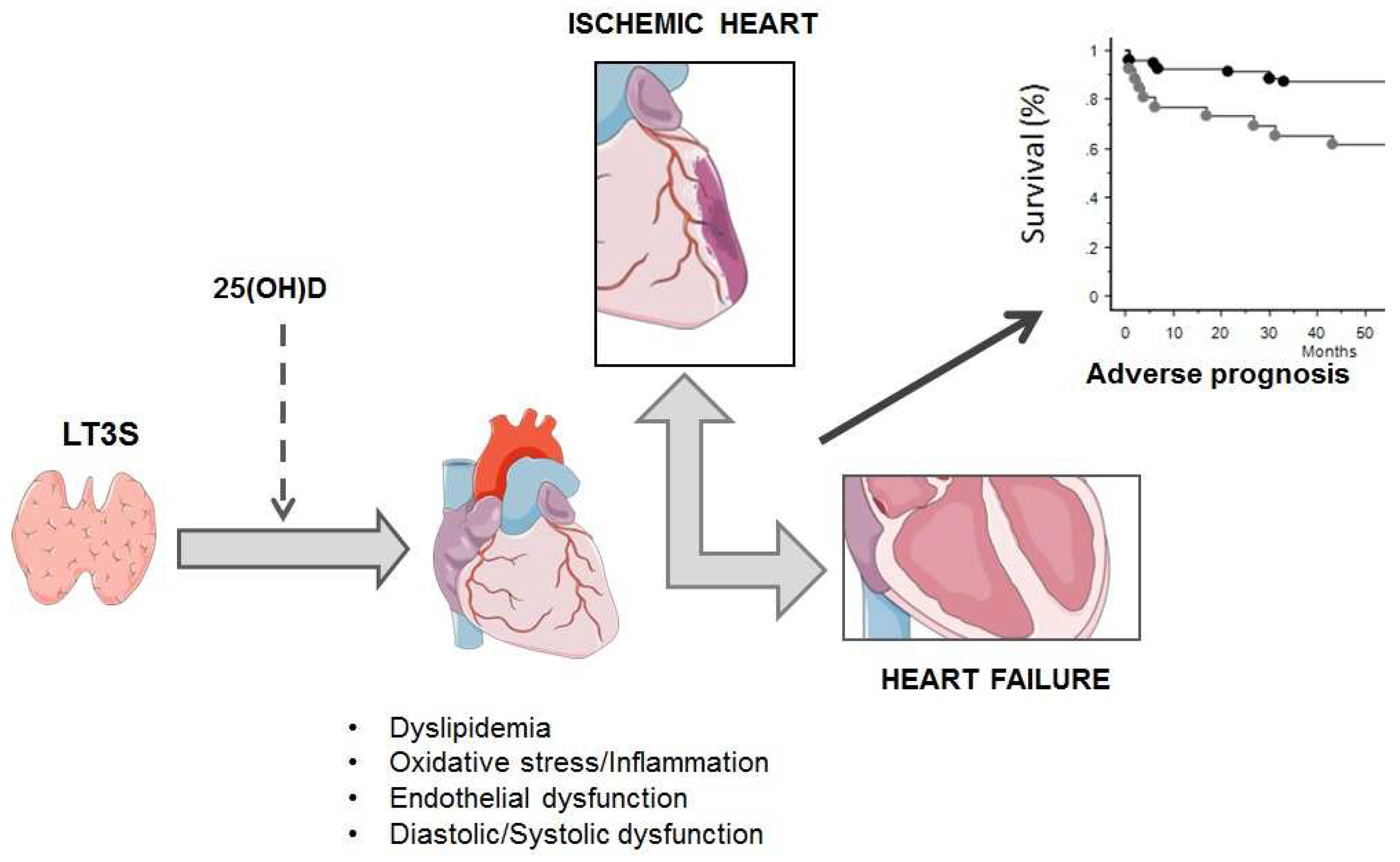

Thyroid and cardioprotection

The prognostic impact of TH abnormalities in heart failure and acute myocardial infarction

TH replacement therapy in heart failure and acute myocardial infarction

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wicomb W, Cooper DK, Hassoulas J, Rose AG, Barnard CN. Orthotopic transplantation of the baboon heart after 20 to 24 hours’ preservation by continuous hypothermic perfusion with an oxygen- ated hyperosmolar solution. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982, 83, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper DK, Wicomb WN, Rose AG, Barnard CN. Orthotopic allotransplantation and autotrans- plantation of the baboon heart following twenty-four hours’ storage by a portable hypothermic perfusion system. Cryobiology. 1983, 20, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novitzky D, Cooper DKC, Barnard CN. The surgi- cal technique of heterotopic heart transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983, 36, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper DK, Wicomb WN, Barnard CN. Storage of the donor heart by a portable hypothermic perfu- sion system: experimental development and clinical experience. J Heart Transplant. 1983, 2, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wicomb WN, Cooper DK, Novitzky D, Barnard CN. Cardiac transplantation following storage of the donor heart by a portable hypothermic perfusion sys- tem. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984, 373, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wicomb WN, Cooper DKC, Lanza RP, Novitzky D, Isaacs S. The effects of brain death and 24 hours’ storage by hypothermic perfusion on donor heart function in the pig. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986, 91, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitzky D, Wicomb WN, Cooper DKC, Rose AG, Fraser RC, Barnard CN. Electrocardiographic, hae- modynamic and endocrine changes occurring during experimental brain death in the Chacma baboon. J Heart Transplant. 1984, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, H. Some experimental and clinical observa- tions concerning states of increased intracranial ten- sion. Am J Med Sci. 1902, 124, 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, A. Ueber morbus Basedowi. Mitt Grenzgeb Med Chir. 1901, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DKC, Novitzky D, Wicomb WN. The patho- physiological effects of brain death on potential donor organs, with particular reference to the heart. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989, 71, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Novitzky D, Rose AG, Cooper DKC, Reichart B. Interpretation of endomyocardial biopsy after heart transplantation. Potentially confusing factors. S Afr Med J. 1986, 70, 789–792. [Google Scholar]

- Novitzky D, Wicomb WN, Cooper DKC, Rose AG, Reichart B. Prevention of myocardial injury during brain death by total cardiac sympathectomy in the Chacma baboon. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986, 41, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitzky D, Cooper DKC, Rose AG, Reichart B. Prevention of myocardial injury by pretreatment with verapamil hydrochloride prior to experimental brain death: efficacy in a baboon model. Am J Emerg Med. 1987, 5, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novitzky D, Cooper DKC, Morrell D, Isaacs S. Change from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism after brain death, and reversal following triiodothyronine (T3) therapy. Transplantation. 1988, 45, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, BE. Clinical notes on hearts in hyperthy- roidism. Boston Med Surg J. 1922, 186, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr WJ, Hensel GC. Observations of the cardiovas- cular system in thyroid disease. Arch Intern Med. 1923, 31, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratschke J, Wilhelm MJ, Kusaka M, et al. Brain death and its influence on donor organ quality and outcome after transplantation. Transplantation. 1999, 67, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolies A, Wood ERS. The heart in thyroid disease. I. The effect of thyroidectomy on the orthodiagram. J Clin Invest. 1935, 14, 483–496. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan DR, Berlin DD, Volk MC, Stern B, Blumgart HL. Therapeutic effect of total ablation of normal thyroid on congestive heart failure and angina pecto- ris. IX. Postoperative parathyroid function. Clinical observations and serum calcium and phosphorus studies. J Clin Invest. 1934, 13, 789–806. [Google Scholar]

- Goetsch, E. Newer methods in the diagnosis of thyroid disorders: pathological and clinical: B. Adrenaline hypersensitiveness in clinical states of hyperthyroid- ism. NY State J Med. 1918, 18, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CH, Shepeard WL, Green MF, DeGroat AF. Response of the hyperthyroid heart to epineph- rine. Am J Phys. 1935, 112, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney TE, Braunwald E, Kahler RL. Effects of gua- nethidine on triiodothyronine-induced hyperthyroid- ism in man. New Eng J Med. 1961, 265, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, GS. The adrenergic nervous system in hyper- thyroidism: therapeutic role of beta adrenergic block- ing drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 1976, 1, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- No authors listed. The coronary drug project. Findings leading to further modifi cations of its protocol with respect to dextrothyroxine. The coronary drug project research group. JAMA. 1972, 220, 996–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Pilo A, Iervasi G, Vitek F, Ferdeghini M, Cazzuola F, Bianchi R. Thyroidal and peripheral production of 3,5,3 ’ - triiodothyronine in humans by multicompartmental analysis. Am J Physiol. 1990, 258, E715–26. [Google Scholar]

- Young WF Jr, Gorman CA, Jiang NS, Machacek D, Hay ID. L-thyroxine contamination of pharmaceutical D-thyroxine: probable cause of therapeutic effect. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984, 36, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, H. The thyroid and the heart. Br Med J. 1959, 1, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers VK, Surtees SJ. Thyrotoxicosis and heart disease. Acta Med Scand. 1961, 169, 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Yater, WM. The tachycardia, time factor, sur- vival period and seat of action of thyroxine in the perfused hearts of thyroxinized rabbits. Am J Phys. 1931, 98, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, C. The heart in thyroid dysfunction. Postgrad Med J. 1945, 21, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata JR, Ernster L, Lindberg O, Arrhenius E, Pedersen S, Hedman R. The action of thyroid hormones at the cell level. Biochem J. 1963, 86, 408–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillmann, WH. Hormonal influences on cardiac myo- sin ATPase activity and myosin isoenzyme distribu- tion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1984, 34, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheimer JH, Koerner D, Schwartz HL, Surks MI. Specific nuclear triiodothyronine bind- ing sites in rat liver and kidney. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1972, 35, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lompré AM, Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. Expression of the cardiac ventricular alpha- and beta-myosin heavy chain genes is developmentally and hormonally regulated. J Biol Chem. 1984, 259, 6437–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the car- diovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razvi S, Jabbar A, Pingitore A, Danzi S, Biondi B, Klein I, Peeters R, Zaman A, Iervasi G. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular function and diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018, 24, 1781–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Kahaly GJ, Dillmann WH. Thyroid hormone action in the heart. Endocr Rev. 2005, 26, 704–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar A, Pingitore A, Pearce SH, Zaman A, Iervasi G, Razvi S (2017) Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 14(1):39–55.

- Hartong R, Wang N, Kurokawa R, Lazar MA, Glass CK, Apriletti, Dillmann WH. Delineation of three different thyroid hormone-response elements in promoter of rat sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2_-ATPase gene. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269, 13021–13029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I. Endocrine disorders and cardiovascular disease. In: Mann, ed.(Chapter81). Braunwald’s Heart Disease.

- Mastorci F, Sabatino L, Vassalle C, Pingitore A. Cardioprotection and Thyroid Hormones in the Clinical Setting of Heart Failure. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020, 10, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun Z, Ojamaa K, Coetzee WA, Artman M, Klein I. Effects of thyroid hormone on action potential and repolarization currents in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 278, E302–E307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachucki J, Burmeister LA, Larsen PR. Thyroid hormone regulates hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel (HCN2) mRNA in the rat heart. Circ Res. 1999, 85, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danzi S, Klein I. Thyroid hormone and blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003, 5, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein I, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone and the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, Fazio S. Effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac function: the relative importance of heart rate, loading conditions, and myocardial contractility in the regulation of cardiac performance in human hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, R. Immunoregulation in autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid. 1994, 4, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. S. , and Biondi, B. ( 2012). Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet 379, 1142–1154. [CrossRef]

- Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, Fazio S. Effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac function: the relative importance of heart rate, loading conditions, and myocardial contractility in the regulation of cardiac performance in human hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G. J. , and Dillmann, W. H. ( 2005). Thyroid hormone action in the heart.Endocr. Rev. 26, 704–728. [CrossRef]

- Mohr-Kahaly, S. , Kahaly, G., and Meyer, J. (1996). [Cardiovascular effects of thyroid hormones]. Z. Kardiol. 85(Suppl. 6), 219–231.

- Weltman NY, Wang D, Redetzke RA, Gerdes AM. Longstanding hyperthyroidism is associated with normal or enhanced intrinsic cardiomyocyte function despite decline in global cardiac function. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e46655. [CrossRef]

- Klein I. Endocrine disorders and cardiovascular disease. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow R, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa. W.B. Saunders; 2005:2051–2065.

- Fredlund BO, Olsson SB. Long QT interval and ventricular tachycardia of “torsade de pointe” type in hypothyroidism. Acta Med Scand. 1983, 213, 231–235.

- Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Baker E, Bacharach P, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med. 1994, 331, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 56. Parle JV, Maisonneuve P, Sheppard MC, Boyle P, Franklyn JA. Prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly people from one low serum thyrotropin result: a 10-year cohort study. Lancet. 2001, 358, 861–865. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iervasi, G., Molinaro, S., Landi, P., Taddei, M. C., Galli, E., Mariani, F., et al. (2007). Association between increased mortality and mild thyroid dysfunction in cardiac patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 167, 1526–1532. [CrossRef]

- Cappola, A. R., Fried, L. P., Arnold, A. M., Danese, M. D., Kuller, L. H., Burke, G. L., et al. (2006). Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA 295, 1033–1041. [CrossRef]

- Rodondi, N., Bauer, D. C., Cappola, A. R., Cornuz, J., Robbins, J., Fried, L. P., et al. (2008). Subclinical thyroid dysfunction, cardiac function, and the risk of heart failure. The Cardiovascular Health study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1152–1159. [CrossRef]

- Rodondi N, Aujesky D, Vittinghoff E, Cornuz J, Bauer DC. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006, 119, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, F. , Di Bello, V., Caraccio, N., Bertini, A., Giorgi, D., Giusti, C., et al. (2001). Effect of levothyroxine on cardiac function and structure in subclinical hypothyroidism: a double blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 1110–1115. [CrossRef]

- Ripoli, A. , Pingitore, A., Favilli, B., Bottoni, A., Turchi, S., Osman, N. F., et al. (2005). Does subclinical hypothyroidism affect cardiac pump performance? Evidence from a magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 439–445. [CrossRef]

- Hak AE, Pols HA, Visser TJ, Drexhage HA, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women: the Rotterdam Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000, 132, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler W, Haass M. Cardioprotection: definition, classification, and fundamental principles. Heart. 1996, 75, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore A, Nicolini G, Kusmic C, Iervasi G, Grigolini P, Forini F. Cardioprotection and thyroid hormones. Heart Fail Rev. 2016, 21, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 66. Forini F, Pitto L, Nicolini G. Thyroid Hormone, Mitochondrial Function and Cardioprotection (chapter 9). In: Iervasi et al. (eds.), Thyroid and Heart. Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 G.

- Goldenthal MJ, Ananthakrishnan R, Marín-García J. Nuclear-mitochondrial cross-talk in cardiomyocyte T3 signaling: a time-course analysis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005, 39, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli E, Pingitore A, Iervasi G. The role of thyroid hormone in the pathophysiology of heart failure: clinical evidence. Heart Fail Rev. 2010, 15, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, Hennessey JV, Klein I, Mechanick JI, et al.. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. (2012) 22:1200–35.

- Pan, Y. , Wang Y., Shi W., Liu Y., Cao S., Yu T. Mitochondrial proteomics alterations in rat hearts following ischemia/reperfusion and diazoxide post conditioning. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale P, Nicolini G, Pitto L, Kusmic C, Rizzo M, Balzan S, Iervasi G, Forini F. Role of miR-133/Dio3 Axis in the T3-Dependent Modulation of Cardiac mitoK-ATP Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 6549.

- Sabatino, L. Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Defense and Thyroid Hormone Signaling: A Focus on Cardioprotective Effects. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Nera G, Sabatino L, Gaggini M, Gorini F, Vassalle C. Vitamin D Determinants, Status, and Antioxidant/Anti-inflammatory-Related Effects in Cardiovascular Risk and Disease: Not the Last Word in the Controversy. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oanzi ZH, Alenazy FO, Alhassan HH, Alruwaili Y, Alessa AI, Alfarm NB, Alanazi MO, Alghofaili SI. The Role of Vitamin D in Reducing the Risk of Metabolic Disturbances That Cause Cardiovascular Diseases. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023, 10, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Alrefaie Z, Awad H. Effect of vitamin D3 on thyroid function and deiodinase 2 expression in diabetic rats. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2015;121(5):206-9.

- Miura M, Tanaka K, Komatsu Y, Suda M, Yasoda A, Sakuma Y, Ozasa A, Nakao K 2002 A novel interaction between thyroid hormones and 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) in osteoclast formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 291: 987–994.

- Gouveia CH, Christoffolete MA, Zaitune CR, Dora JM, Harney JW, Maia AL, Bianco AC. Type 2 iodothyronine selenodeiodinase is expressed throughout the mouse skeleton and in the MC3T3-E1 mouse osteoblastic cell line during differentiation. Endocrinology. 2005, 146, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg JP, Liane KM, Bjørhovde SB, Bjøro T, Torjesen PA, Haug E. Vitamin D receptor binding and biological effects of cholecalciferol analogues in rat thyroid cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994, 50, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Emden MC, Wark JD. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances thyrotropin releasing hormone induced thyrotropin secretion in normal pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1987, 121, 1192–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Liu Q, Dong H, Feng Y, Raguthu C, Liang X, Liu C, Zhang Z, Yao X. The protective effect of iodide intake adjustment and 1,25(OH)2D3 supplementation in rat offspring following excess iodide intake. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020, 11, 2042018820958295. [Google Scholar]

- Vassalle C, Parlanti A, Pingitore A, Berti S, Iervasi G, Sabatino L. Vitamin D, Thyroid Hormones and Cardiovascular Risk: Exploring the Components of This Novel Disease Triangle. Front Physiol. 2021, 12, 722912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić Leko M, Jureško I, Rozić I, Pleić N, Gunjača I, Zemunik T. Vitamin D and the Thyroid: A Critical Review of the Current Evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore A, Mastorci F, Berti S, Sabatino L, Palmieri C, Iervasi G, Vassalle C. Hypovitaminosis D and Low T3 Syndrome: A Link for Therapeutic Challenges in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirhosseini N, Brunel L, Muscogiuri G, Kimball S. Physiological serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with improved thyroid function-observations from a community-based program. Endocrine. 2017, 58, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iervasi G, Pingitore A, Landi P, Raciti M, Ripoli A, Scarlattini M, L’Abbate A, Donato L. Low-T3 syndrome: a strong prognostic predictor of death in patients with heart disease. Circulation. 2003, 107, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingitore A, Iervasi G, Barison A, Prontera C, Pratali L, Emdin M, Giannessi D, Neglia D. Early activation of an altered thyroid hormone profile in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic idiopathic left ventricular dysfunction. J Card Fail 2006, 12, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro S, Iervasi G, Lorenzoni V, Coceani M, Landi P, Srebot V, Mariani F, L'Abbate A, Pingitore A. Persistence of mortality risk in patients with acute cardiac diseases and mild thyroid dysfunction. Am J Med Sci. 2012, 343, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis G, Covino M, Burzo ML, Della Polla DA, Petti A, Bruno C, Franceschi F, Mancini A, Gambassi G Prognostic role of hypothyroidism and low free-triiodothyronine levels in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Intern Emerg Med. 2021, 16, 1477–1486. [CrossRef]

- Zhou P, Huang LY, Zhai M, Huang Y, Zhuang XF, Liu HH, Zhang YH, Zhang J. [The prognostic value of free triiodothyronine/free thyroxine ratio in patients hospitalized with heart failure]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023, 103, 1679–1684 Chinese. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Han S, Li Y, Tong F, Li Z, Sun Z. Value of FT3/FT4 Ratio in Prognosis of Patients With Heart Failure: A Propensity-Matched Study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 859608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel NA, Cuthbert JJ, Brown OI, Kazmi S, Cleland JGF, Rigby AS, Clark AL. Relation Between Thyroid Function and Mortality in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol. 2021, 139, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 92. Iacoviello M, Parisi G, Gioia MI, Grande D, Rizzo C, Guida P, Lisi F, Giagulli VA, Licchelli B, Di Serio F, Guastamacchia E, Triggiani V. Thyroid Disorders and Prognosis in Chronic Heart Failure: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2020, 20, 437–445. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Yao Y, Chen Z, Fan S, Hua W, Zhang S, Fan X. Thyroid-stimulating hormone within the normal range and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Clin Cardiol. 2019, 42, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato Y, Yoshihisa A, Kimishima Y, Kiko T, Kanno Y, Yokokawa T, Abe S, Misaka T, Sato T, Oikawa M, Kobayashi A, Yamaki T, Kunii H, Nakazato K, Takeishi Y. Low T3 Syndrome Is Associated With High Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2019, 25, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan L, Shaw PA, Morley MP, Brandimarto J, Fang JC, Sweitzer NK, Cappola TP, Cappola AR. Thyroid dysfunction in heart failure and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e005266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato Y, Yoshihisa A, Kimishima Y, Kiko T, Watanabe S, Kanno Y, Abe S, Miyata M, Sato T, Suzuki S, Oikawa M, Kobayashi A, Yamaki T, Kunii H, Nakazato K, Ishida T, Takeishi Y. Subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with adverse prognosis in heart failure patients. Can J Cardiol. 2018, 34, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen YY, Shu XR, Su ZZ, Lin RJ, Zhang HF, Yuan WL, Wang JF, Xie SL. A low-normal free triiodothyronine level is associated with adverse prognosis in euthyroid patients with heart failure receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. Int Heart J. 2017, 58, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi T, Hasegawa T, Kanzaki H, Funada A, Amaki M, Takahama H, Ohara T, Sugano Y, Yasuda S, Ogawa H, Anzai T. Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2016, 3, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Guan H, Fang W, Zhang K, Gerdes AM, Iervasi G, et al. Free triiodothyronine level correlates with myocardial injury and prognosis in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: evidence from cardiac MRI and SPECT/PET imaging. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 39811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayama D, Minami Y, Kataoka S, Shiga T, Hagiwara N. Thyroid function on admission and outcome in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure. J Cardiol. 2015, 66, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Guan H, Gerdes M, Iervasi G, Yang Y, Tang Y. Thyroid status, cardiac function and mortality in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015, 100, 3210–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Shauer A, Zwas DR, Lotan C, Keren A, Gotsman I. The effect of thyroid function on clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2014, 16, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang CP, Jong YS, Wu CY, Lo HM. Impact of triiodothyronine and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide on the long term survival of critically ill patients with acute heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2014, 113, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Yang X, Wang Y, Ding L, Wang J, Hua W. The prevalence and prognostic effects of subclinical thyroid dysfunction in dilated cardiomyopathy patients: a single-center cohort study. J Card Fail. 2014, 20, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez AC1, Jhund PS1, Stott DJ2, Gullestad L3, Cleland JG4, van Veldhuisen DJ5, Wikstrand J6, Kjekshus J3, McMurray JJ7. Thyroid-stimulating hormone and clinical outcomes: the CORONA trial (controlled rosuvastatin multinational study in heart failure). JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey A, Kroiss M, Berliner D, Seifert M, Allolio B, Güder G, Ertl G, Angermann CE, Störk S, Fassnacht M. Prognostic impact of subclinical thyroid dysfunction in heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013, 168, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell JE, Hellkamp AS, Mark DB, Anderson J, Johnson GW, Poole JE, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Thyroid function in heart failure and impact on mortality. JACC Heart Fail. 2013, 1, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passino C, Pingitore A, Landi P, Fontana M, Zyw L, Clerico A, Emdin M, Iervasi G. Prognostic value of combined measurement of brain natriuretic peptide and triiodothyronine in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009, 15, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello M, Guida P, Guastamacchia E, Triggiani V, Forleo C, Catanzaro R, Cicala M, Basile M, Sorrentino S, Favale S. Prognostic role of sub-clinical hypothyroidism in chronic heart failure outpatients. Curr Pharm Des. 2008, 14, 2686–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozdag G, Ural D, Vural A, Agacdiken A, Kahraman G, Sahin T, Ural E, Komsuoglu B. Relation between free triiodothyronine/free thyroxine ratio, echocardiographic parameters and mortality in dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005, 7, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore A1, Landi P, Taddei MC, Ripoli A, L'Abbate A, Iervasi G. Triiodothyronine levels for risk stratification of patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2005, 118, 132136. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton MA, Stevenson LW, Luu M, Walden JA. Altered thyroid hormone metabolism in advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990, 16, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrano V, Pingitore A, Carpi A, Iervasi G. Relationship between triiodothyronine and proinflammatory cytokines in chronic heart failure. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010, 64, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen Y, Chen G, Su S, Zhao C, Ma H, Xiang M. Independent Association of Thyroid Dysfunction and Inflammation Predicts Adverse Events in Patients with Heart Failure via Promoting Cell Death. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cittadini A, Salzano A, Iacoviello M, Triggiani V, Rengo G, Cacciatore F, Maiello C, Limongelli G, Masarone D, Perticone F, Cimellaro A, Perrone Filardi P, Paolillo S, Mancini A, Volterrani M, Vriz O, Castello R, Passantino A, Campo M, Modesti PA, De Giorgi A, Monte IP, Puzzo A, Ballotta A, D'Assante R, Arcopinto M, Gargiulo P, Sciacqua A, Bruzzese D, Colao A, Napoli R, Suzuki T, Eagle KA, Ventura HO, Marra AM, Bossone E; T. O.S.CA. Investigators. Multiple hormonal and metabolic deficiency syndrome predicts outcome in heart failure: the T. O.S.CA. Registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahal S, Datta S, Ravat V, Patel P, Saroha B, Patel RS. Does subclinical hypothyroidism affect hospitalization outcomes and mortality in congestive cardiac failure patients? Cureus. 2018, 10, e2766. [CrossRef]

- 117. Fontes R, Coeli CR, Aguiar F, Vaisman M. Reference interval of thyroid stimulating hormone and free thyroxine in a reference population over 60 years old and in very old subjects (over 80 years): comparison to young subjects. Thyroid Research 2013, 6, 13. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Tinoco R, Castillo-Martı´nez L, Orea-Tejeda A, et al. Developing thyroid disorders is associated with poor prognosis factors in patient with stable chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2011, 147, e24–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merla R, Martinez JD, Martinez MA, et al. Hypothyroidism and renal function in patients with systolic heart failure. Tex Heart Inst J 2010, 37, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler C, Schneider A, Gutjahr-Lengsfeld L, et al. Thyroid function, cardiovascular events, and mortality in diabetic hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2014, 63, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg L, Werner S, Eggertsen G, Ahnve S. Rapid down-regulation of thyroid hormones in acute myocardial infarction: is it cardioprotective in patients with angina?Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162, 1388–1394. [CrossRef]

- Wang WY, Tang YD, Yang M, Cui C, Mu M, Qian J, Yang YJ. Free triiodothyronine level indicates the degree of myocardial injury in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013, 126, 3926–3929. [Google Scholar]

- Ceremuzyński L, Górecki A, Czerwosz L, Chamiec T, Bartoszewicz Z, Herbaczyńska-Cedro Low serum triiodothyronine in acute myocardial infarction indicates major heart injury. K.Kardiol Pol. 2004, 60, 468–480.

- Lymvaios I, Mourouzis I, Cokkinos DV, Dimopoulos MA, Toumanidis ST, Pantos C Thyroid hormone and recovery of cardiac function in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a strong association? .Eur J Endocrinol. 2011, 165, 107–114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reindl M, Feistritzer HJ, Reinstadler SJ, Mueller L, Tiller C, Brenner C, Mayr A, Henninger B, Mair J, Klug G, Metzler B. Thyroid-stimulating hormone and adverse left ventricular remodeling following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019, 8, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han C, Xu K, Wang L, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Wei A, Dong L, Hu Y, Xu J, Li W, Li T, Liu C, Qi W, Jin D, Zhang J, Cong H. Impact of persistent subclinical hypothyroidism on clinical outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2022, 96, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brozaitiene J, Mickuviene N, Podlipskyte A, Burkauskas J, Bunevicius R. Relationship and prognostic importance of thyroid hormone and N-terminal pro-B-Type natriuretic peptide for patients after acute coronary syndromes: a longitudinal observational study. Cardiovasc Disord. 2016, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu T, Tian C, Song J, He D, Wu J, Wen Z, Sun Z, Sun Z. Value of the fT3/fT4 ratio and its combination with the GRACE risk score in predicting the prognosis in euthyroid patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018, 18, 181, PMID: 30200880; PMCID: PMC6131820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Ma W, Huang S, Lin X, Yu M. Impact of low triiodothyronine syndrome on long-term outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries. Ann Med. 2021, 53, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore A, Chen Y, Gerdes AM, Iervasi G. Acute myocardial infarction and thyroid function: new pathophysiological and therapeutic perspectives. Annals of Medicine. Ann Med. 2012, 44, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin A, Chitsazan M, Taghavi S, Ardeshiri M. Effects of triiodothyronine replacement therapy in patietns with chronic stable heart failure and low-triidotrhyronine syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. ESC Heart Failure 2015, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmager P, Schmidt U, Mark P, Andersen U, Dominguez H, Raymond I, Zerahn B, Nygaard B1, Kistorp C, Faber J. Long-term L-Triiodothyronine (T3) treatment in stable systolic heart failure patients: a randomised, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled intervention study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015, 83, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curotto Grasiosi J, Peresotti B, Machado RA, et al. Improvement in functional capacity after levothyroxine treatment in patients with chronic heart failure and sublinical hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Nutr 2013, 60, 427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S, McCarren M, Morkin E, et al. DITPA (3,5-Diiodothyropropionic Acid), a thyroid hormone analog to treat heart failure: phase II trial Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. Circulation 2009, 119, 3093–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingitore A, Galli E, Barison A, et al. Acute effects of triiodothyronine (T3) replacement therapy in patients with chronic heart failure and low-T3 syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iervasi G, Emdin M, Colzani RMP, et al. Beneficial effects of long-term triiodothyronine (T3) infusion in patients with advanced heart failure and low T3 syndrome. In: Kimchi A, editor. Second International Congress on Heart Disease - new trends in research, diagnosis and treatment. Medimond Medical Publications;Englewood, NJ, USA: 2001. p. 549-53.

- Malik FS, Mehra MR, Uber PA, et al. Intravenous thyroid hormone supplementation in heart failure with cardiogenic shock. J Card Fail 1999, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton MA, Stevenson LW, Fonarow GC, et al. Safety and hemodynamic effects of intravenous triiodothyronine in advanced congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1998, 81, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moruzzi P, Doria E, Agostoni PG. Medium-term effectiveness of L-thyroxine treatment in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Med 1996, 101, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi C, Bao Y, Chen X, Tian L. The Effectiveness of Thyroid Hormone Replacement Therapy on Heart Failure and Low-Triiodothyronine Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Endocr Pract. 2022, 28, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Bao Y, Shi C, Tian L. Effectiveness and Safety of Thyroid Hormone Therapy in Patients with Dilated Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of RCTs. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2022, 22, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore A, Mastorci F, Piaggi P, Aquaro GD, Molinaro S, Ravani M, De Caterina A, Trianni G, Ndreu R, Berti S, Vassalle C, Iervasi G. Usefulness of Triiodothyronine Replacement Therapy in Patients With ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Borderline/Reduced Triiodothyronine Levels (from the THIRST Study). Am J Cardiol 2018, 00, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pantos C et al Effects of Acute Triiodothyronine Treatment in Patients with Anterior Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Angioplasty: Evidence from a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial (ThyRepair Study). Thyroid. 2022, 32, 714–724. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbar A et al Effect of Levothyroxine on Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Patients With Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020, 324, 249–258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharmapoopathy M, Thavarajah A; Kenny RPW, Pingitore A, Iervasi G, Dark J, Bano A, Razvi S. Efficacy and Safety of Triiodothyronine Treatment in Cardiac Surgery or Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Thyroid. 2022, 32, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes AM, Portman MA, Iervasi G, Pingitore A, Cooper DKC, Novitzky D. Ignoring a basic pathophysiological mechanism of heart failure progression will not make it go away. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021, 320, H1919–H1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TH Dysfunction | Events (n) | N° PTS (W,%) | Age (yy) | LVEF (%) | NYHA class III-IV | Prognostic weight | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fT3/fT4 ratio <2.15 | Cardiac Death, Transplantation, LV device implantation | 3257 (18) | 57 | ND | ND | HR values of FT3/FT4 ratio predicting the risk of composite endpoint in pts with LVEF <40%, 40-49%, and≥50% were 0.91, 0.83, and 0.65, respectively | [89] |

| fT3/fT4 cutoff 0.233 | CV death (29%) , Overall Death (25%) | 8887 (46) | 69 | 50 | 85% | HR of all-cause mortality and for CV death for pts with a high FT3/FT4 ratio was 0.841 and 0.844 times less than that in pts with a low FT3/FT4 ratio | [90] |

| TSH >4.70 mIU/l, TSH <0.35 mIU/l. | Overall death | 4992 (45) | 74 | ND | 34% | Hypothyroidism (HR 1.259) and hyperthyroidism (HR 1.21) had a greater risk of death compared to euthyroidism. | [91] |

| LT3, Hypothyroidism | Overall death | 762 | ND | ND | ND | Independent association with death significant in pts with TSH >10 mIU/L. LT3 was independently associated with HF hospitalization and death | [92] |

| SCH: (TSH 4-10 microUI/mL), HYPO: (TSH >10 microUI/mL), LT3: (fT3 < 1.8 pg/ml) | in-hospital death | 1018 (55) | 81 | ND | 80% | Mortality rate was 27% among HYPO pts , 17% in SCH pts, and 11% among euthyroid pts. HYPO (HR 2.1) and fT3 levels (HR 3.4) were associated with an increased likelihood of in-hospital death. | [88] |

| TSH quartiles (≤ 1.3; 1.4-2.2; 2.3-3.5; ≥3.6 mlU/L) | Cardiac Death (28), non-Cardiac Death (30) HF impairment (40), Cardiac transplantation (11), Ventricular Arrhythmias (24) | 180 (21) | 37 | 28 | 35% | Serum TSH levels (> 2.67 nIU/L) may provide help for the stratification of the risk of ventricular arrhythmias | [93] |

| LT3:fT3≤2.03 pg/ml | CV Death (88), non-CV death (105) | 911 (41) | 68 | 60 | 3% | LT3 at discharge is associated with higher cardiac and all cause-mortalitY, accompanied by high central venous pressure, lower nutritional status and impaired exercise capacity | [94] |

| SCH:TSH >4.51 mlU/L ; LT3: total T3 < 80 ng/dl | cardiac transplantation (104), VAD replacement (31), Overall death (327) | 1,365 (35) | 57 | 34 | No data | SCH (HR 1.82) and LT3 (HR 2.12) were associated with increased risk of composite end-point | [95] |

| SCH:TSH >4 µlU/mL | Worsening HF (232), CV death (108), non-CV death (128) | 1043 (41) | 67 | 42 | 3% | SCH is an independent predictor of cardiac event (HR 1.42) and all-cause mortality (1.421) after adjustment with other confounders | [96] |

| fT3< 3.00 pmol/L | CV Death (30), non-CV death (6), Hospitalization (45) | 113 (3.5) | 61 | 31 | 64% | Patients with fT3 < 3.00 pmol/L had higher overall mortality and HF hospitalization | [97] |

| SCH: TSH of 4.5 to 19.9mIU/L; SHY: TSH <0.45 mIU/L | CV Death (27), Rehospitalization (80) | 274 (70) | 70 | 39 | 100% | Higher TSH is independently associated with composite CV events. SCH is an independent predictor (HR: 2.31) of composite CV events | [98] |

| fT3 <2.77 pg/mL | CV death (19), non-CV death (4) | 71 (34) | 54 | 26 | No data | FT3 < 2.77 pg/mL was identified as predictor of events (HR: 8.623) | [99] |

| LT3:fT3 ≤2.05 pg/ml | CV death (16), non-CV death (10) | 270 (31) | 68 | 67 | 100% | LT3 on admission is associated with higher in-hospital all-cause, cardiac, and non-cardiac death rates, and with increased 1-year death | [100] |

| LT3:fT3 <1.79 pg/mL; SCH:TSH >4.78 mlU/L normal fT3 and or fT4; SHY: TSH <0.55 mlU/L and normal fT3 and or fT4; HYPO: TSH >4.78 mlU/L and < fT3 and or Ft4 | non-CV death (ND) | 458 (29) | 51 | 32 | ND | HYPO was the strongest predictor of death (HR 4.189), followed by LT3 (HR 3.147) and SHYPO (HR 2.869) | [101] |

| TSH quartiles (≤ 1.3; 1.4-2.2; 2.3-3.5; ≥3.6 mlU/L) | CV death (ND) CV hospitalization (ND) | 5599 (51) | 75 | <50 | ND | Increased risk of death in the highest TSH group (HR 1.54).TSH as an independent predictor of the combined endpoint | [102] |

| Total T3 ≤ 52.3 ng/dl | CV Death (38), non-CV death (16) | 144 (49) | 71 | 42 | 100% | T3 as independent predictors for both all-cause and cardiac mortalities among critical ill patients with HF, and high NT-proBNP and low T3 levels predict a worse long-term outcome | [103] |

| SHY: TSH <0.35 µIU/mLSCH: TSH >5.5 µIU/mL | Overall death | 963 (26) | 52 | 32 | 72% | SHY, SCH have higher all-cause mortality rate. However, only SHY (HR 1.793), not SCH , is an independent predictor for increased risk of overall death | [104] |

| SHY: TSH <0.3 µIU/mLSCH: TSH >5.0 µIU/mL | CV Death (1104), Hospitalization (1210), non-CV death (1402) | 4750 (22) | 73 | 31 | 63% | SCH associated with an increased risk of the composite outcome of CV death or HF hospitalization (HR: 1.29), as well as all-cause death (HR: 1.36). When NT-proBNP was added to the predictive models, the association between SCH and all outcomes was eliminated | [105] |

| LT3: fT3 <2.7 pmol/l SHY: TSH <0.3 mIU/l SCH: TSH >4.0 mIU/l HYPER: TSH <0.1 mIU/l HYPO: TSH >4.0 mIU/l | CV death (153), non-CV death (111) | 758 (29) | 68 | 30 | ND | SCH, SHY; HYPO, HYPER are not relevant prognostic factors. LT3 is a significant indicator of poor prognosis | [106] |

| HYPO (>5.0 μU/ml), HYPER (<0.3 μU/ml) | non-CV death (ND) | 2,225 (48) | 59 | 24 | ND | HYPO and HYPER were associated with 58% and 85% increases in the risk for death (HR: 1.58; HR: 1.85) | [107] |

| LT3: fT3 <2.1 ng/L | CV Death (64), non-CV death (46) | 442 (25) | 65 | 33 | 37% | Pts with LT3 and higher BNP showed the highest risk of all-cause and cardiac death | [108] |

| SCH: TSH >5.5 mlU/L | Hospitalization (55), non-CV death (18), transplantation (6) | 338 (33) | 64 | 32 | ND | TSH levels even slightly above normal range are independently associated with a greater likelihood of HF progression | [109] |

| fT3/fT4 ratio ≤1.7 | CV Death (15), VF (1) | 111 (31) | 62 | 29 | ND | fT3/fT4 ratio ≤ 1.7 was associated with an increased risk of mortality, independent of other prognostic markers. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictivity of fT3/fT4 ratio ≤ 1.7 for cardiac mortality were 100%, 71%, 36% and 100% | [110] |

| free T3, 3.2 to 6.5 pmol/L (2 to 4.2 pg/mL); | CV Death (47), non-CV death (17) | 281 (17) | 68 | 28 | ND | Low T3 levels are an independent predictor of mortality adding prognostic information to conventional clinical (age) and functional cardiac parameters (LVEF) | [111] |

| fT3/reverseT3 ratio ≤4 | Cardiac Death (17), Transplantation (6) | 84 (16) | 50 | 18 | 100% | A low fT3/reverse T3 ratio was a predictor of cardiac events with a survival rate of 37%. The lowest ratio was associated with the poorest prognosis | [112] |

| Patients (N) | Study design | LVEF (%) | TH dose treatment | Main findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 ischemic and non-ischemic HF and LT3 | Randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo controlled | 31± 6 | T3 0.025 mg/day, OS | Improvement in NYHA class, ↑ LVEF, ↓ LVESV, ↓ NT-proBNP, ↓ hs-C-reactive protein, ↑ 6-MWD | [131] |

| 13 ischemic and non-ischemic HF and LT3 | Randomized, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled | 43 (37-52) | Oral T3 twice daily for 3 months (tablet dose 20 µg) | No clinical or functional benefit observerd | [132] |

| 163 ischemic, non-ischemic HF, SCH | Uncontrolled | N/A | T4 dose necessary to normalize TSH | ↑ Physical performance at 6 minute walking test | [133] |

| 86 ischemic and non-ischemic HF | Randomized (2:1) placebo controlled | 28 ± 6 | DTPA twice daily 90 mg increments (every 2 wks to maximum 360 mg) | ↑ CI ↓ SVR, lipoproteins and cholesterol | [134] |

| 20 ischemic and non-ischemic HF and LT3 | Randomized, placebo controlled | 25 (18-32) | T3 3 days continuously infused (initial dose 20 g/m2) | ↑ LVSV, LVEDV, ↓ NT-proBNP, Aldosterone, NA | [135] |

| 6 ischemic and non-ischemic HF | Uncontrolled | 24 ± 3 | T3 initial dose 20 mg/m2bs/d Continuous infusion (4 d) | ↓SVR ↑ CO and UO | [136] |

| 10 cardiogenic shock | Uncontrolled | N/A | T4 20 mg/h bolus + continuous infusion (36h) | ↑ CI, PCWP and MAP | [137] |

| 23 ischemic and non-ischemic HF | Uncontrolled | 22 ± 1 | T3 cumulative dose 0.15 -2.7 mg/kg bolus + continuous infusion (6-12 h) | ↓SVR ↑ CO | [138] |

| 10 non-ischemic HF | Randomized (1:1) placebo controlled | 29 ± 6 | T4 100 mg/d OS for 3 months | Improvement in cardiovascular performance at rest, exercise and dobutamine stress test | [139] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).