1. Introduction

Corrosion is one of the most prevalent hazardous problems faced by all types of industries, with economic losses due to corrosion amounting to

$2.5 trillion annually [

1]. Corrosion of materials can be effectively reduced through appropriate corrosion control techniques. Currently, one of the most effective corrosion control techniques is to spray anti-corrosion coatings on metal surfaces [

2].

The most widely used anti-corrosion coatings are organic coatings [

3,

4], but corrosive substances often reach the substrate through the pores present in organic polymers, causing localised corrosion [

5]. In the last decade or so, nanomaterials such as graphene [

6], silicon dioxide (SiO

2)[

7], titanium (Ti)[

8] and TiO

2[

9] have often been filled into organic polymers to improve their corrosion resistance. Nanomaterials, with their lamellar structure and large specific surface area, are excellent fillers for improving the protective effect of coatings by forming a “labyrinth effect” in the coating, increasing the filling rate of pores, and lengthening the path for corrosive substances to reach the substrate [

10,

11].

The latest research progress and application of nano-titanium modified polymers in recent years, analysing the relationship between coating formulations, organisational structure and properties such as corrosion resistance and weathering resistance, exploring the development direction of nano-titanium coatings, and providing ideas for the research and development of high-performance nano-titanium titanium coatings. ChenYuxiu et al.[

12]. The interlayer spacing of montmorillonite (OMMT) was altered by using a titanium enamel phenol polymer (UTP), which enhanced the compatibility of UTPOMMT with epoxy resin (EP). Meanwhile, UTPOMMT possessed a zigzagging and complex pathway, which resulted in a coating with excellent densification and corrosion resistance.

Phenolic resin (PF) is the first synthetic polymer material, which is formed by the polycondensation of phenols and aldehydes in the presence of a catalyst [

13,

14]. Due to its excellent corrosion resistance and mechanical properties, it is widely used in the field of anti-corrosion coatings [

15]. Phenolic resin has become an important polymer material in the fields of aviation, shipping, power generation and construction. With the demand of science and technology and social development, high anti-corrosion performance phenolic resin has become a new development direction.

In recent years, researchers have grafted various metals or metal oxides into phenolic resins, such as magnesium, zinc and aluminium oxide, to improve their corrosion resistance [

16,

17]. Because titanium and oxygen extreme affinity, in the air is easy to form a layer of dense titanium dioxide film, so it has good corrosion resistance [

18]. Modifying phenolic resin with titanium can greatly improve its corrosion resistance. Zhang Yan prepared a new type of nano-titanium-modified phenolic resin [

19], but the extremely harsh dissolution conditions limit the further development of nano-titanium-modified phenolic resin. The research on the synthesis and anticorrosive application of nano-titanium modified phenolic resins has not yet been carried out in depth.

In summary, in order to improve the application field of phenolic resin waterborne coatings, this paper adopts physicochemical methods to prepare nano-titanium-modified phenolic resin with silane coupling agent KH550 and phenolic resin as the reactive polymer; nanohybrid modification of one-component phenolic resin is performed by high-speed milling, and nano-titanium-modified phenolic resin coatings are prepared, to study the corrosion-resistant properties and to explore the principle of nano-titanium modification and this study will investigate the principle of titanium modification and the mechanism of corrosion prevention, and provide more experimental data and technical support for the research and development of new waterborne coatings.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The titanium nanopowder (1000 mesh) used in the test was purchased from Wuxi Dinglong Mining Co., Ltd.; the phenolic resin, NL curing agent and silane coupling agent KH550 were provided by Henan Huanshan Industry Co., Ltd.; the anhydrous ethanol solution and acetone solution were purchased from Taicang Xintian Alcohol Co. Except for anhydrous ethanol and acetone solution, which are analytically pure, the rest of the above materials are of industrial grade. Deionized water was used during the test.

2.2. Preparation of nanotitanium modified phenolic resin

Nano-titanium modified phenolic resins with 3%, 4% and 5% (percentage of content with phenolic resin) of titanium nanopowder were prepared according to the following steps, respectively.

The nano-titanium modified phenolic resin was prepared by magnetic stirring method using a cylindrical flask at room temperature. Firstly, deionised water was added to the phenolic resin and stirred under the action of magnetic stirring at 500-600 r/min for 5 min, and then silane coupling agent KH550 and a certain amount of titanium powder were added and stirred at 300 r/min for 10 min to obtain a dark green slurry-like modified product. In the above preparation process, under the action of the rotor, the material and the material, the material and the rotor collide with each other, the molecular chain of the phenolic resin breaks and opens the ring, and the titanium powder and the phenolic resin complete the grafting by using the principle of mechanochemistry. As shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Preparation of coatings

Dissolve a certain amount of phenolic resin with deionised water, add add additives and then magnetically stir with nano titanium modified phenolic resin at 500r/min (the same as later), dispersed homogeneously and then add a certain amount of curing agent one by one, and dispersed homogeneously with a magnetic stirrer, which is to obtain the nano titanium modified phenolic resin anticorrosive coatings. The reference formula is shown in

Table 2.

The substrate for this experiment is Q235 steel, its size is 30mm×20mm×0.2mm, and the surface of the substrate needs to be treated before the experiment. The treatment process is to sand it with 200# sandpaper first, and then clean it with acetone solution and ethanol solution to remove the rust or dirt on the surface, and then put it into the vacuum drying oven for drying. The coating was uniformly applied to the substrate with a special brush for water-based coatings and kept at room temperature (25±2°C) for 168 h to complete the coating production.

2.4. Structural characterisation and performance testing

Observation of the morphology of nanotitanium-modified phenolic resin coating surface. SEM was used to analyze the morphology of the nanotitanium-modified phenolic resin coating, and the 1 cm × 1 cm coating surface after gold spraying was scanned.

To determine whether the nanotitanium powder and phenolic resin were grafted or not. FTIR was used to characterize the synthesized sample coatings by taking a point in the coating with absorption peaks ranging from 4000 to 500 cm−1 with a resolution of 4.0 cm−1.

To determine the UV absorption capacity of nanotitanium phenolic resin coating before and after modification. A UV-visible spectrophotometer was used to determine the UV absorption of the coating.

Referring to GB/T 10125-2021 “Artificial At mosphere Corrosion Test Salt Spray Test”, the JL-YWX-150P salt spray box from Nanjing Jinling Instrument and Equipment Co. was used to investigate and analyze the corrosion resistance of the coating.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. SEM analysis

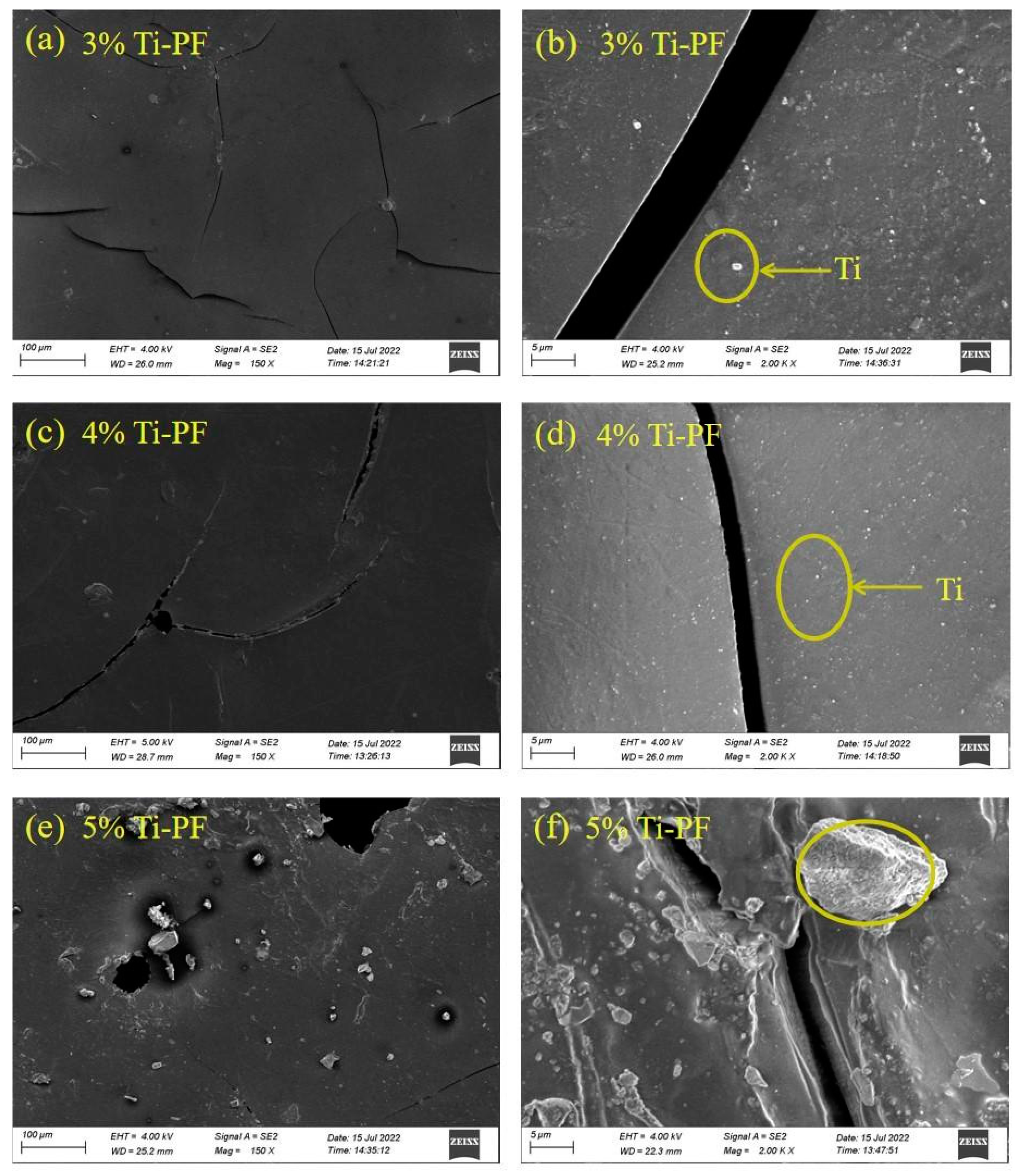

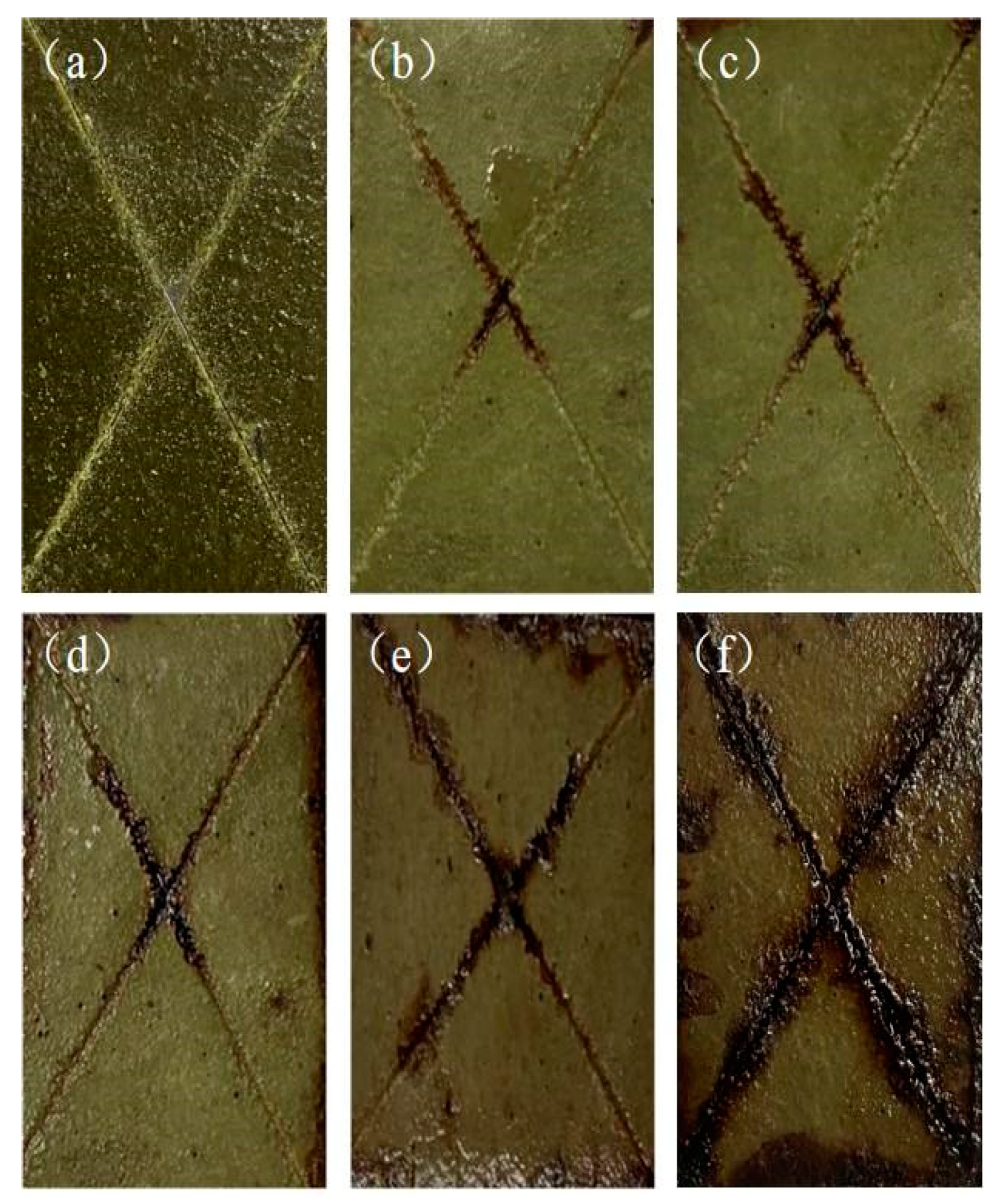

SEM images of phenolic resin coatings with different mass fractions of nanotitanium are shown in

Figure 1. From

Figure 1, it can be seen that the number and width of cracks in the coating is minimum and the number of holes is also minimum when the nanotitanium is 3%. The bright colored dots in

Figure 1 are titanium nanopowders and it can be seen that the nanotitanium nanopowders that have not agglomerated are in the form of spheres. As shown in

Figure 1b, when the titanium nanopowder is 3%, some of the titanium nanopowder is not dispersed uniformly and agglomerates are formed, which attenuates the small size effect of the nanomaterials. As shown in

Figure 1d, when the nanotitanium powder is 4%, the addition of nanotitanium powder increases the roughness of the coating, and there is no obvious agglomeration although the distribution of nanotitanium powder is more scattered. As shown in

Figure 1f, when the nano-titanium powder was 5%, the nano-titanium powder agglomeration was the most serious, probably because the nano-titanium powder mass fraction relative to the phenolic resin was too high, which greatly increased the porosity of the coating. According to the above surface morphology distribution of nano-titanium modified phenolic resin coating when phenolic resin and nano-titanium powder are compounded at different ratios, it can be inferred that when the content of nano-titanium powder is 4%, the nano-titanium powder and phenolic resin will be dispersed to the maximum extent, and the two are compatible, which makes the nano-particles give full play to their functions and greatly reduces the porosity of the coating.

3.2. FTIR and Raman spectral characterization

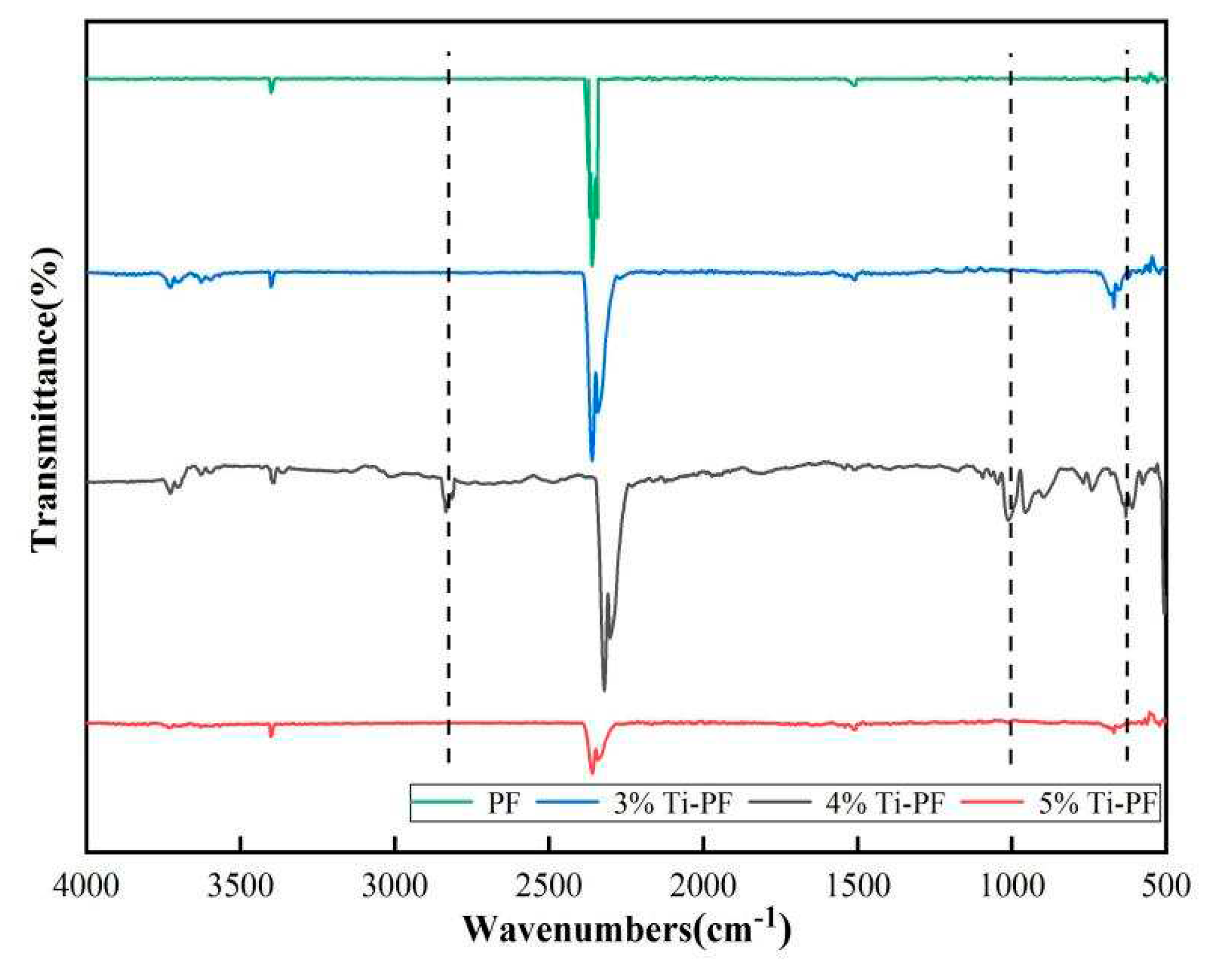

The FTIR spectra of the modified phenolic resin coatings with different nanotitanium contents are shown in

Figure 2. The characteristic peaks of the modified phenolic resin coating with the addition of 4% titanium nanoparticles were significantly increased compared to the pure PF coating. It contains different peaks at 642, 1050, 2831 and 2951 cm

−1. Among them, the antisymmetric vibration peak of C-O-C at 1, 050 cm

−1 indicates the presence of silane coupling agent in the phenolic resin; the characteristic absorption peak of Si-O-Ti at 642 cm

−1 and at 2831 and 2951 cm

−1 there are -CH

2 and -CH

3 telescopic vibration absorption peaks, indicating that the silane coupling agent KH550 has been grafted together with the titanium nanopowder [

20], and the nanotitanium-modified phenolic resin was prepared. The addition of 3% and 5% nano-titanium modified phenolic resin coatings showed characteristic peaks different from those of the pure PF coatings, but they were not obvious. It can be inferred that maximum grafting of nanotitanium with phenolic resin occurred when 4% nanotitanium was added.

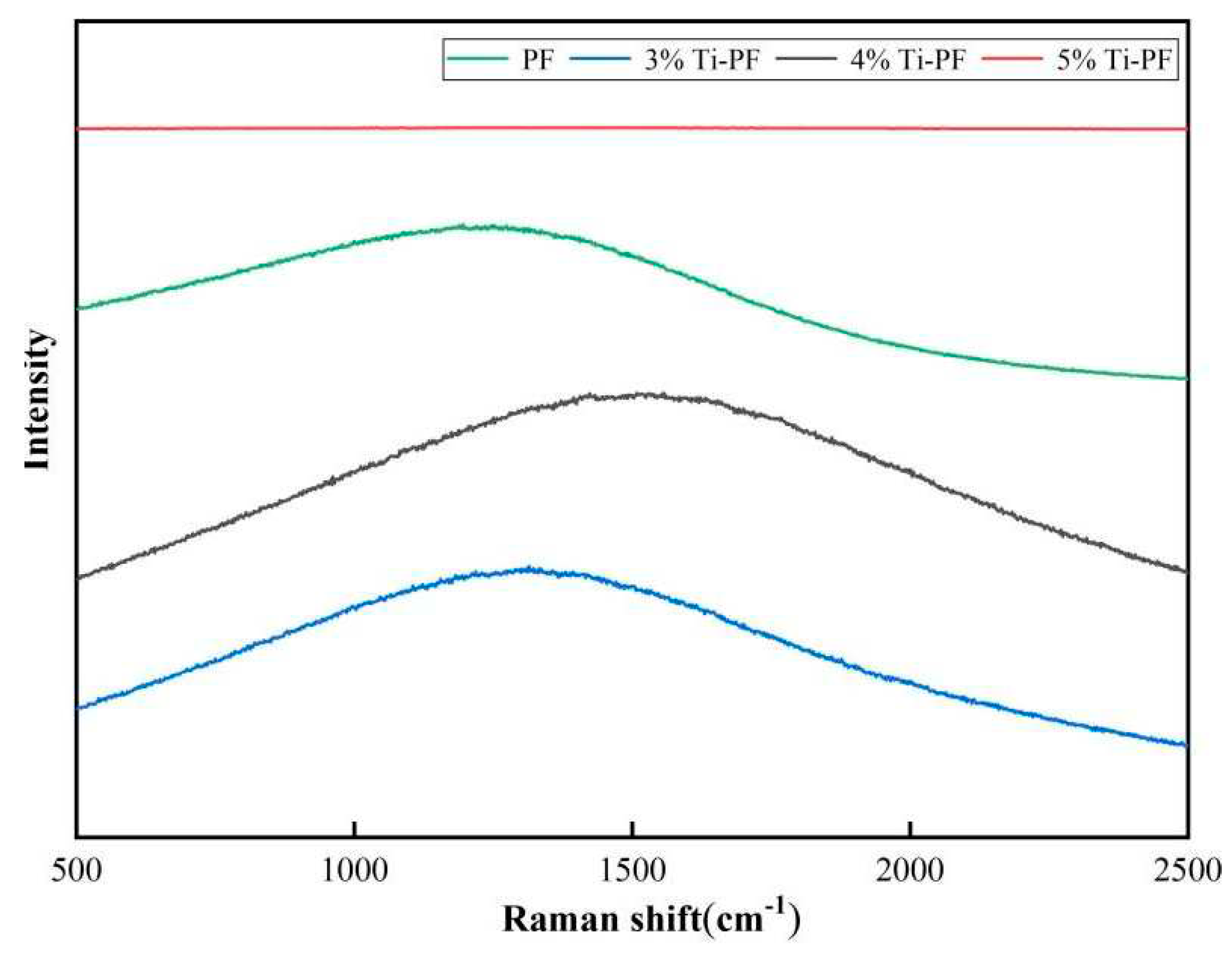

The Raman spectra of the modified phenolic resin coatings with different titanium nanoparticles content are shown in

Figure 3. Compared with the pure PF coatings, 3%, 4% and 5% nano-titanium modified phenolic resin coatings showed a wave peak, which was due to the completion of grafting of nano-titanium with phenolic resin, but there was no obvious characteristic peak, which may be due to the agglomeration of nano-titanium, and only a smaller amount of nano-titanium completed the grafting with phenolic resin. The peak of the wave was the highest when the content of nanotitanium was 4%. It was also confirmed that the maximum grafting of nanotitanium with phenolic resin occurred when 4% nanotitanium was added.

3.3. UV analysis

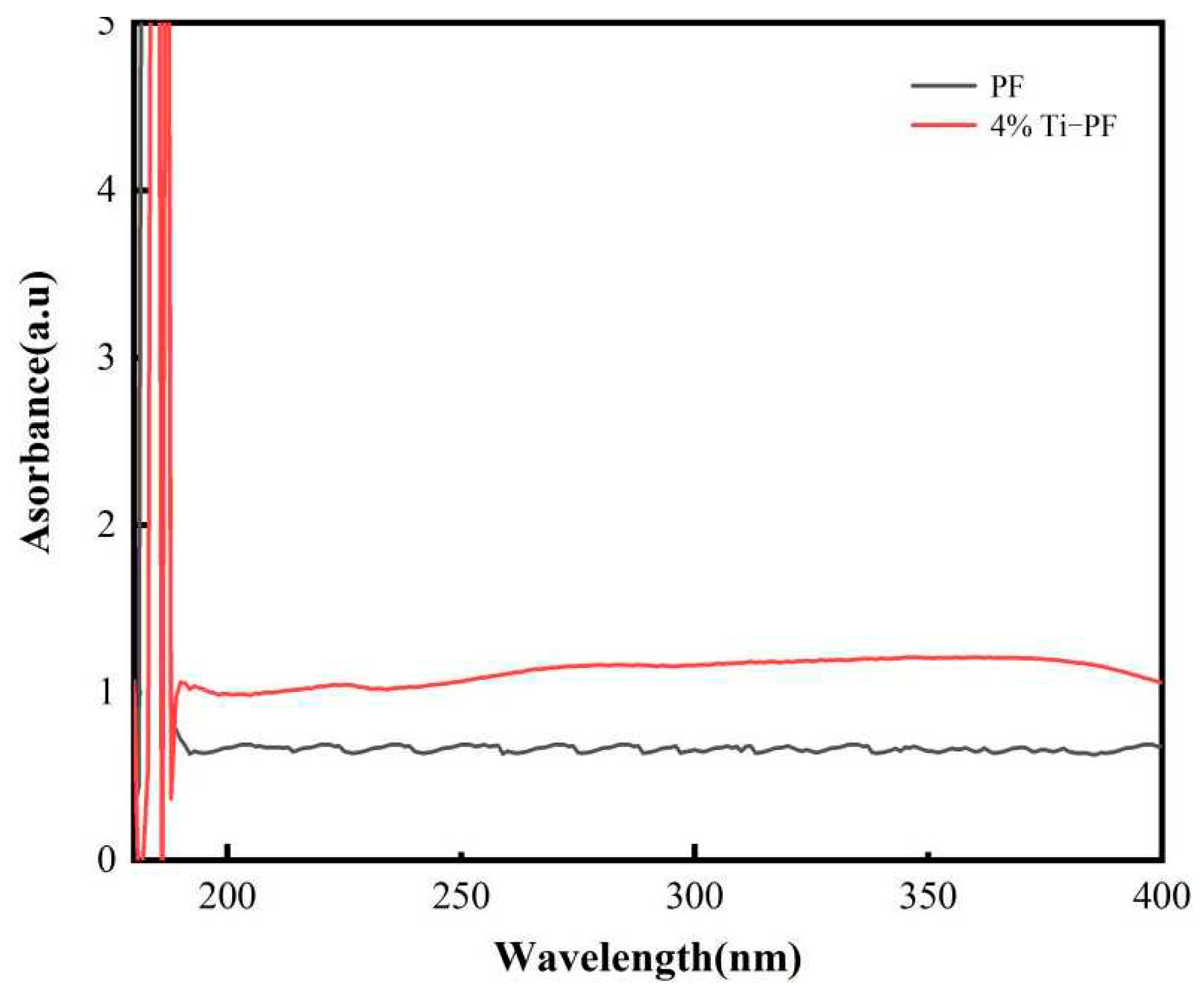

According to the results of infrared spectrogram and Raman spectroscopy, 4% titanium nanopowder and PF were grafted best in the presence of silane coupling agent. UV analysis of 4% nano titanium modified phenolic resin coatings was performed. The UV-Vis absorption profiles of pure PF coating and 4% nanotitanium modified phenolic resin coating are shown in

Figure 4. From

Figure 4, it can be seen that the PF coatings before and after modification have similar absorption in the range of ≤185 nm, which is due to the fact that the phenolic resin has an aromatic ring, which contains unbonded electrons of oxygen as well as C=O to form π-bonds, and so the coatings have a strong absorption at 185 nm. In the UV region of 185-400 nm, the nanotitanium-modified coating showed a greater degree of absorption than the pure PF coating. This indicates that the addition of modified titanium nanoparticles is favorable for the improvement of the UV resistance of the coating.

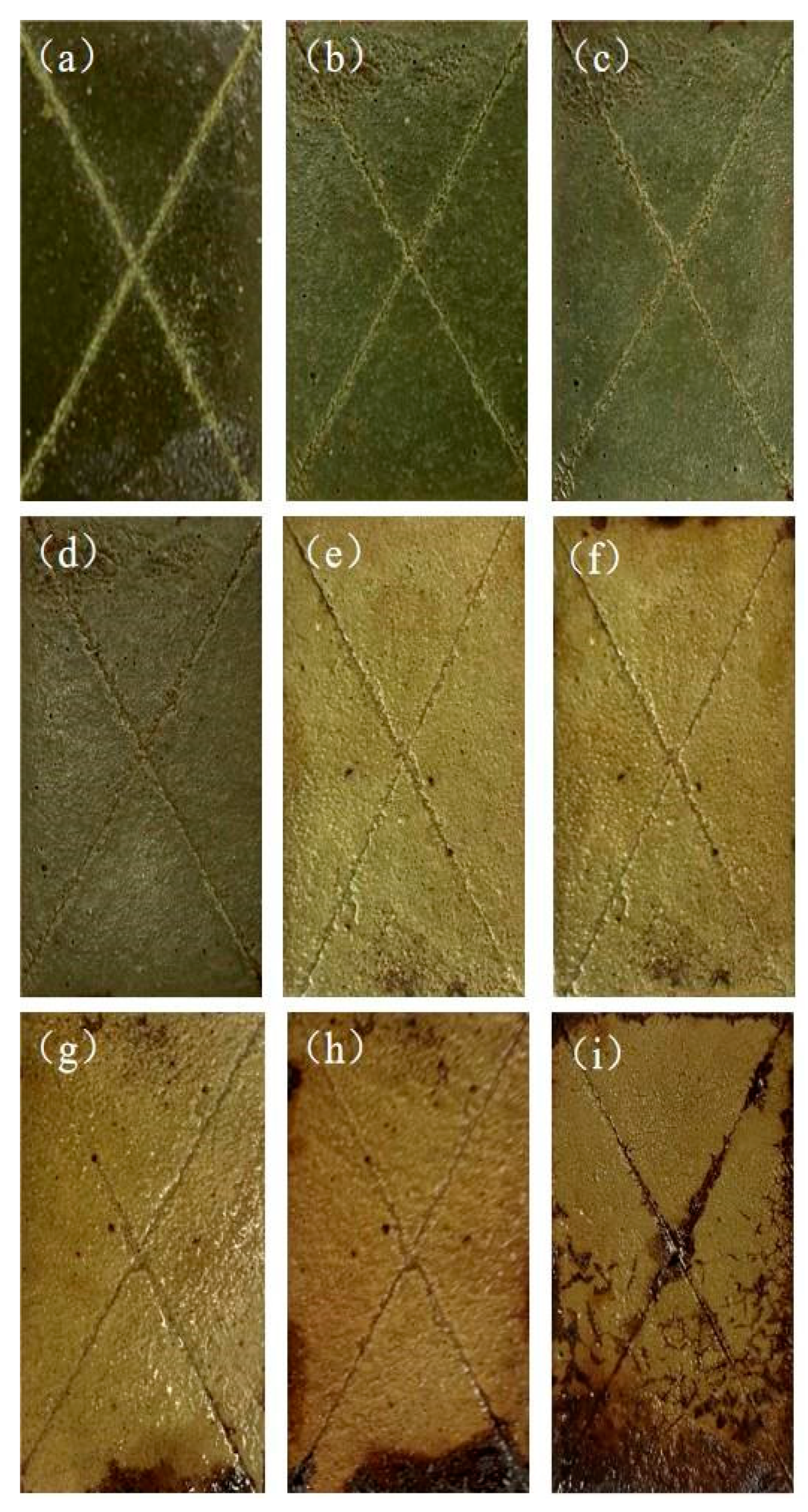

3.4. Salt spray resistance test

Based on the analysis of the above tests, the 4% nanotitanium-modified phenolic resin coating has a good structure, and in order to further study its corrosion resistance, thethis paper conducts salt spray resistance test for 768 h on pure PF coatings and nano-titanium-modified phenolic resin coatings with a content of 4%, and the specific experimental process parameters are shown in

Table 3. The test results are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. It can be seen that the pure PF coating corroded seriously around the scratch and its surface layer after 480 h of continuous spraying, and a large number of bubbles and rust appeared near the scratch, with a corrosion width of about 2~3mm, while the 4% titanium nano-modified phenolic resin coating showed crack-like corrosion only after 768 h of continuous spraying. This indicates that the corrosion resistance of phenolic resin coating can be significantly improved by adding nanotitanium. The nano-titanium modified phenolic resin coating firstly started to corrode from the periphery because the coating sample was not closed completely around the sample and the sample substrate was exposed to the salt spray environment. Loss of solvents or volatile substances within the coating and degradation and aging of the molecular chains in the coating caused a change in the surface state of the coating, resulting in a decrease in the gloss of the coating.

3.4. Anti-corrosion mechanism of composite coating

There are a large number of nanoscale pores in conventional coatings, and the addition of nanomaterials just fills these pores, basically blocking the penetration of external corrosive substances into the coating. Nano titanium will form a dense oxide film at room temperature, with excellent corrosion resistance, so the introduction of nano titanium into the anti-corrosion coating can enhance the corrosion resistance of the coating.

Nano titanium modified polymer was prepared by physicochemical method, after magnetic stirring, nano titanium powder and phenolic resin were combined through chemical bonding force to form a spatial mesh structure, the adhesion and hydrophobicity of the coating film was enhanced to improve the adhesion of the coating, which made it difficult for corrosive substances to be adsorbed on the surface of the coating, thus enhancing the barrier ability of the coating to the corrosive substances [

21].

Nano-Titanium modified phenolic resin can disperse nano-Titanium uniformly in the system, forming a mesh structure, effectively filling the defects in the coating, slowing down the infiltration of corrosive substances, increasing the “labyrinth effect”, thus improving anti-corrosion effect [

22].

4. Conclusions

The following conclusions were obtained from the above studies:

(1) The nano-titanium modified phenolic resin was prepared by reacting phenolic resin with nano-titanium powder and silane coupling agent sequentially using physicochemical methods.

(2) When the nano-titanium is 4%, the nano-titanium modified phenolic resin coating will show a good structure, and the nano-titanium powder and phenolic resin are maximally combined. However, some of the nanotitanium powder will be agglomerated and the coating will be cracked, which is a key issue for future research on the subject.

(3) After adding modified titanium nanopowder, the coating’s ability to absorb UV in the UV region of 185~400 nm is greatly improved, and the UV resistance of the coating is enhanced.

(4) The coating showed corrosion on the surface of the coating in a large area after 768 h. The coating was not corroded. The addition of titanium nanoparticles effectively improves the corrosion resistance of the coating and provides a new direction for the development of new water-based anticorrosion coatings.

Author Contributions

Prof Xingdong Yuan conceived the idea and supervised this project. Chengwu Zheng, Fadong Cui and Xiaojing Li performed experiments. Chengwu Zheng, Xiaoliang Wang and Xuegang Wang analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Graduate Program Construction Project of Shandong University of Architecture (YZKG201603, ALK201602, ALK201710, ALK201808), Shandong Province Higher Education Institutions Science and Technology Program (J17KA017), Doctoral Fund of Shandong University of Architecture (XNBS1625), Shandong Province Social Science Planning Research Program (19CHYJ12), Research on corrosion-resistant support technology for high salt water in Jinqiao coal mine (H23180Z0101).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the full financial support for this work provisioned by the Shandong Province Higher Education Institutions Science and Technology Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- The High Cost of Corrosion. Focus on Powder Coatings, 2019, 2019(5):1.

- Gnedenkov, A.S.; Sinebryukhov, S.L.; Filonina, V.S.; et al. Smart composite antibacterial coatings with active corrosion protection of magnesium alloys. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys 2022, 10, 3589–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.G.C.; Pellanda, A.C.; Jorge, A. R, D.C.; et al. Preparation and evaluation of corrosion resistance of a self-healing alkyd coating based on microcapsules containing Tung oil. Progress in Organic Coatings 2020, 147, 105874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L. , et al. Tribological and anticorrosion properties of polyvinyl butyral (PVB) coating reinforced with phenol formaldehyde resin (PF). Progress in Organic Coatings 2021, 158, 106382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarvar, N.M.; Zhang, Y.; Mahmoodi, A.; et al. Nanocomposite organic coatings for corrosion protection of metals: A review of recent advances. Progress in Organic Coatings: An International Review Journal 2022, 162, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.S.; Poornima, V.P.; Paduvilan, J.K.; et al. Advances and future outlook in epoxy/graphene composites for anticorrosive applications. Progress in Organic Coatings 2022, 162, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sh, Ammar, et al. Studies on SiO2-hybrid polymeric nanocomposite coatings with superior corrosion protection and hydrophobicity. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 324, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.R.; Yan, Z.S.; Tang, G.W.; et al. A self-curing, thermosetting resin based on epoxy and organic titanium chelate as an anticorrosive coating matrix for heat exchangers: Preparation and properties. Progress in Organic Coatings: An International Review Journal 2017, 102, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.X.; Huan, Y.; Zhu, M.; et al. Epoxy coating with excellent anticorrosion and pH-responsive performances based on DEAEMA modified mesoporous silica nanomaterials. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 634, 127951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.R.; Li, L.J.; Li, W.S.; et al. Application of nanomaterials in waterborne coatings: a review. Resources Chemicals and Materials 2022, 1, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.R.; Ding, J.H.; Liu, P.L.; et al. Boron nitride-epoxy inverse “nacre-like” nanocomposite coatings with superior anticorrosion performance. Corrosion Science 2021, 183, 109333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; Bai, W.B.; Chen, J.P.; et al. In-situ intercalation of montmorillonite/urushiol titanium polymer nanocomposite for anti-corrosion and anti-aging of epoxy coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings 2022, 165, 106738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.D.; Li, X.Q.; Chen, J.K. Synthesis and characterization of molybdenum/phenolic resin composites binding with aluminum nitride particles for diamond cutters. Applied Surface Science 2013, 284, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.; Zhang, A.L.; Ge, T.J.; et al. Research progress on modification of phenolic resin. Materials Today Communications 2020, 26, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; LIJ, J.; Zhang, S.H.; et al. In situ synthesis of graphene-phenol formaldehyde composites and their highly-efficient radical scavenging effects under the γ irradiation. Corrosion Science 2019, 159, 108139. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, S.; Chen, M.Y.; et al. The anticorrosion mechanism of phenolic conversion coating applied on magnesium implants. Applied Surface Science 2018, 463, 953–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhana, A.M.; Mohana, K.N.S.; Hegde, M.B.; et al. Development of Al2O3.ZnO/GO-phenolic formaldehyde amine derivative nanocomposite: A new hybrid anticorrosion coating material for mild steel. Colloids and Surfaces A Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 601, 125036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, S.; Chavvakula, M.M.; Pravin, K.S.; et al. Titanium-based materials: synthesis, properties, and applications. Materialstoday proceedings 2022, 56, 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Liu, Y. The effect of titanium incorporation on the thermal stability of phenol-formaldehyde resin and its carbonisation microstructure. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2013, 98, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, L.L.; Ren, J.; Lu, J.H.; et al. Preparation of double linked waterborne epoxy resin coating using Titanium curing agent and aminopropyltriethoxysilane and its anticorrosive properties. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2021, 16, 210768. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.Y.; Zhan, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.W.; et al. Fabrication of hydrophobic and enhanced anticorrosion performance of epoxy coating through the synergy of functionalized graphene oxide and nano-silica binary fillers. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 664, 131086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.S.; Zhao, M.Y.; Pei, X.Y.; et al. Improving corrosion resistance of epoxy coating by optimizing the stress distribution and dispersion of SiO2 filler. Progress in Organic Coatings 2023, 179, 107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).