Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

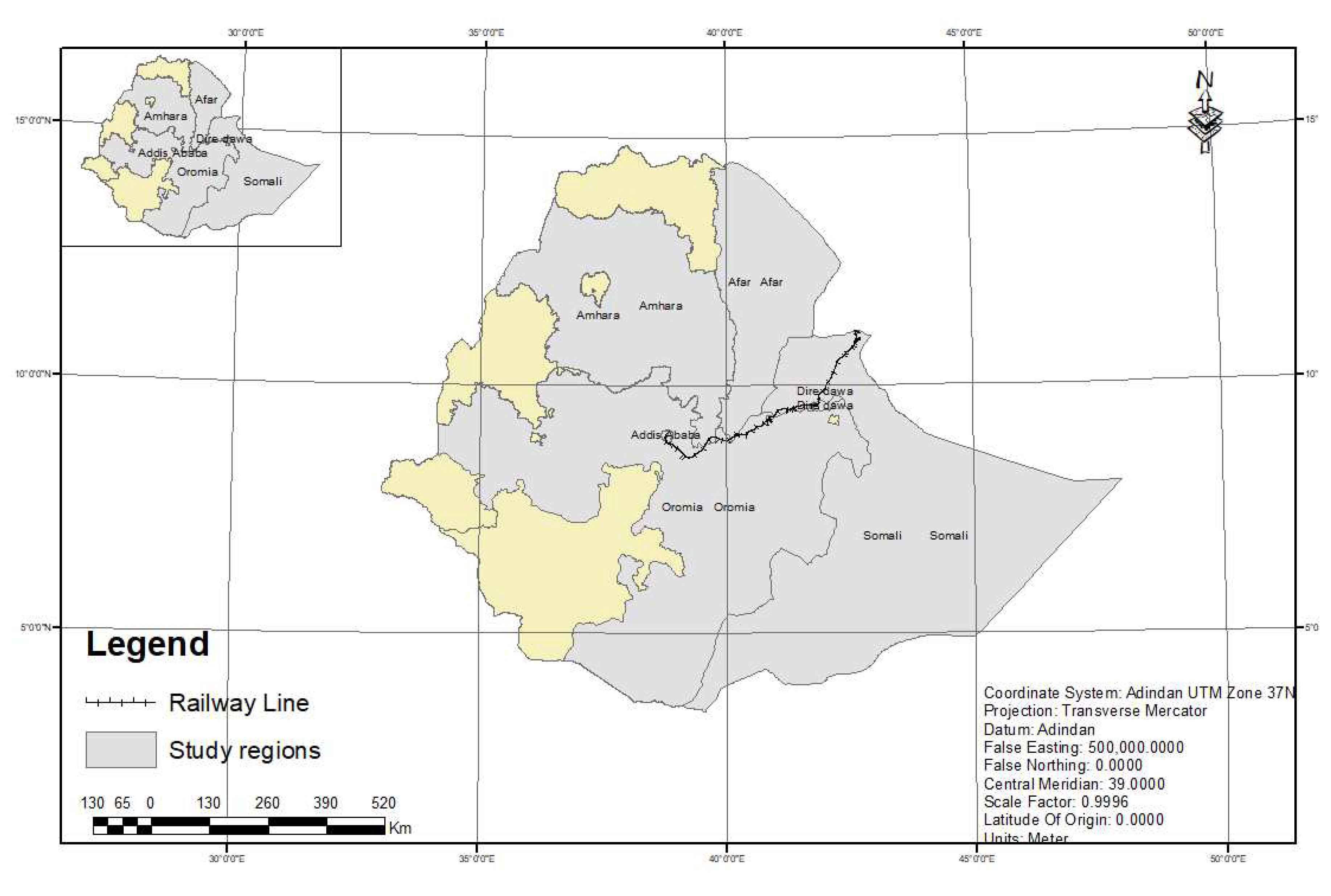

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Case Study

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. The Notion and Nature of Urban Center

3.2. Intermediate City

3.3. Railway Corridor Development

3.3.1. An Overview

3.3.2. Historical Incites on Railway Corridor Development in Ethiopia

| Station section | Distance in Km | Distance Between Major Fright Stations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | From | To | KM | |

| Sebeta | Lebu | 13.322 | Sebeta | Indode | 31.631 |

| Lebu | Indode | 18.309 | |||

| Indode | Bishoftu | 37.61 | Indode | Mojo | 58.263 |

| Bishoftu | Mdjo | 20.653 | |||

| Modjo | Adama | 23.361 | Mojo | Adama | 23.361 |

| Adama | Feto | 41.171 | Adama | Awash | 157.15 |

| Feto | Methara | 63.122 | |||

| Methara | Awash Sebat Killo | 29.496 | |||

| Awash Sebat Killo | Sirba Kunkur | 43.4 | Awash | Dire Dawa | 191.8 |

| Sirba Kunkur | Mieso | 48.28 | |||

| Mieso | Bike | 35.56 | |||

| Bike | Dire Dawa | 64.56 | |||

| Dire Dawa | Arawa | 53.068 | |||

| Arawa | Adigala | 61.778 | |||

| Adigala | Aysha | 50.95 | |||

| Aysha | Dawele | 40.8 | |||

| Dawele | Alishabeh | 20 | |||

| Alishabeh | Holhol | 46 | |||

| Holhol | Negad | 32 | |||

| Total | 743.44 | ||||

3.4. The Impact of the Railway Corridor in Ethiopia

3.4.1. Urban Formation and Urbanization

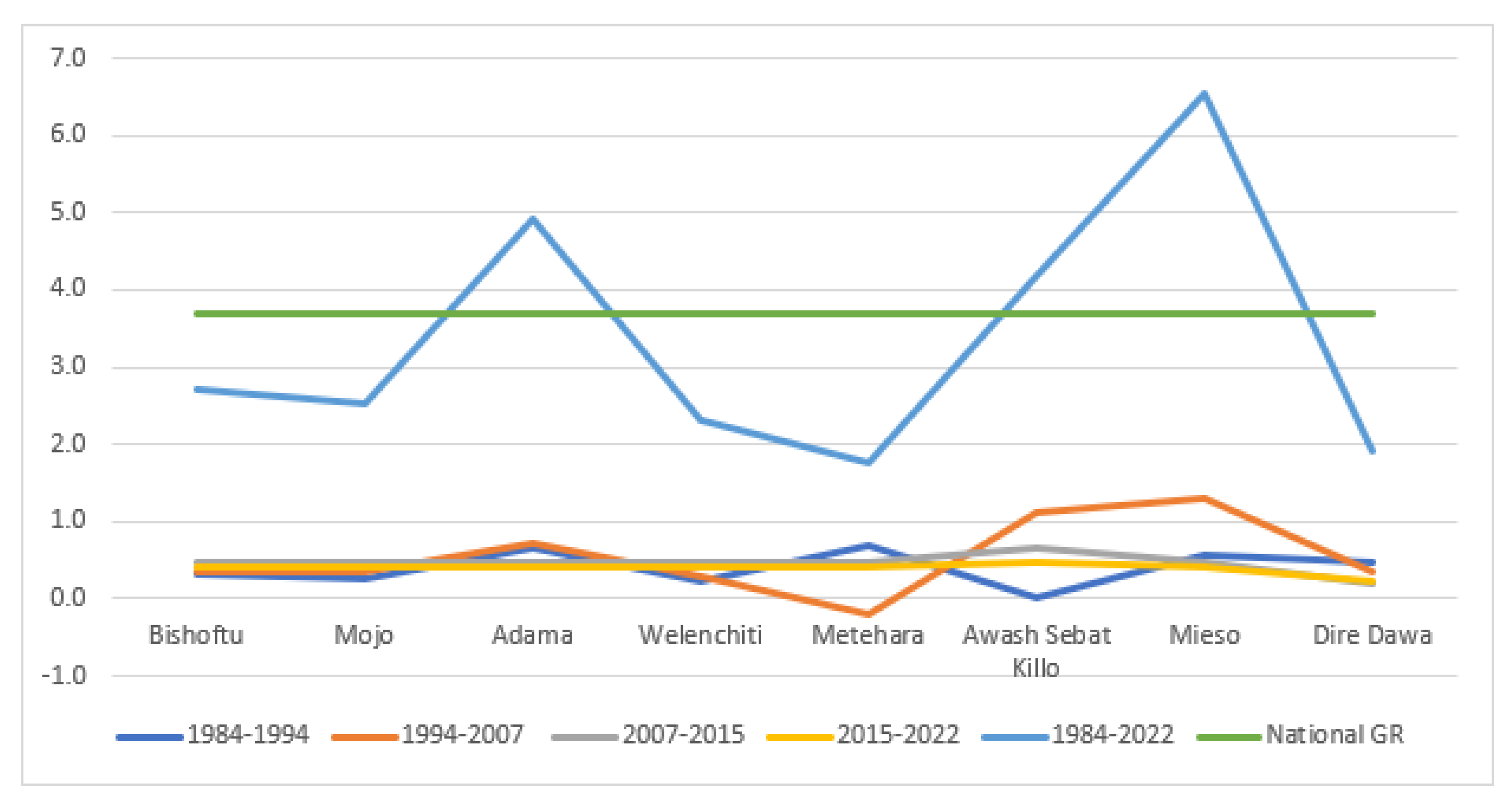

3.4.1.1. Population Dynamics

- A.

- Population Size

- B. Population Growth

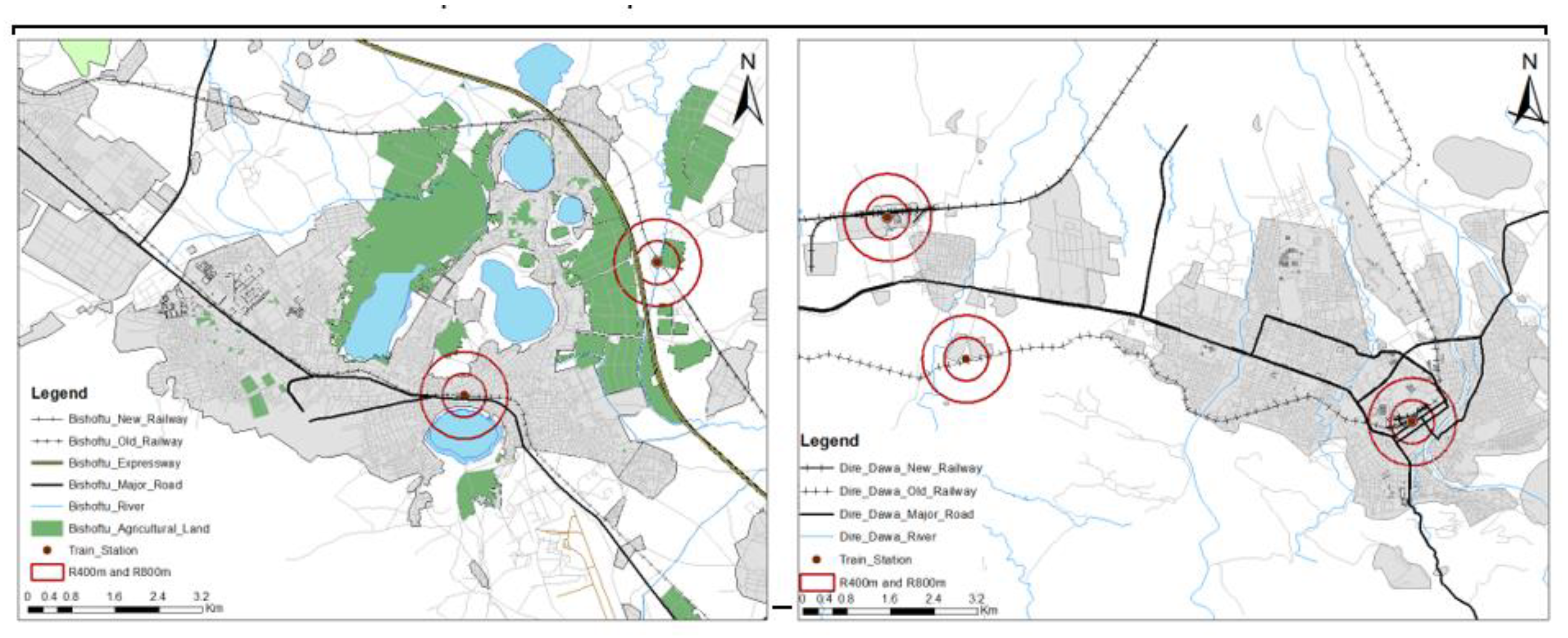

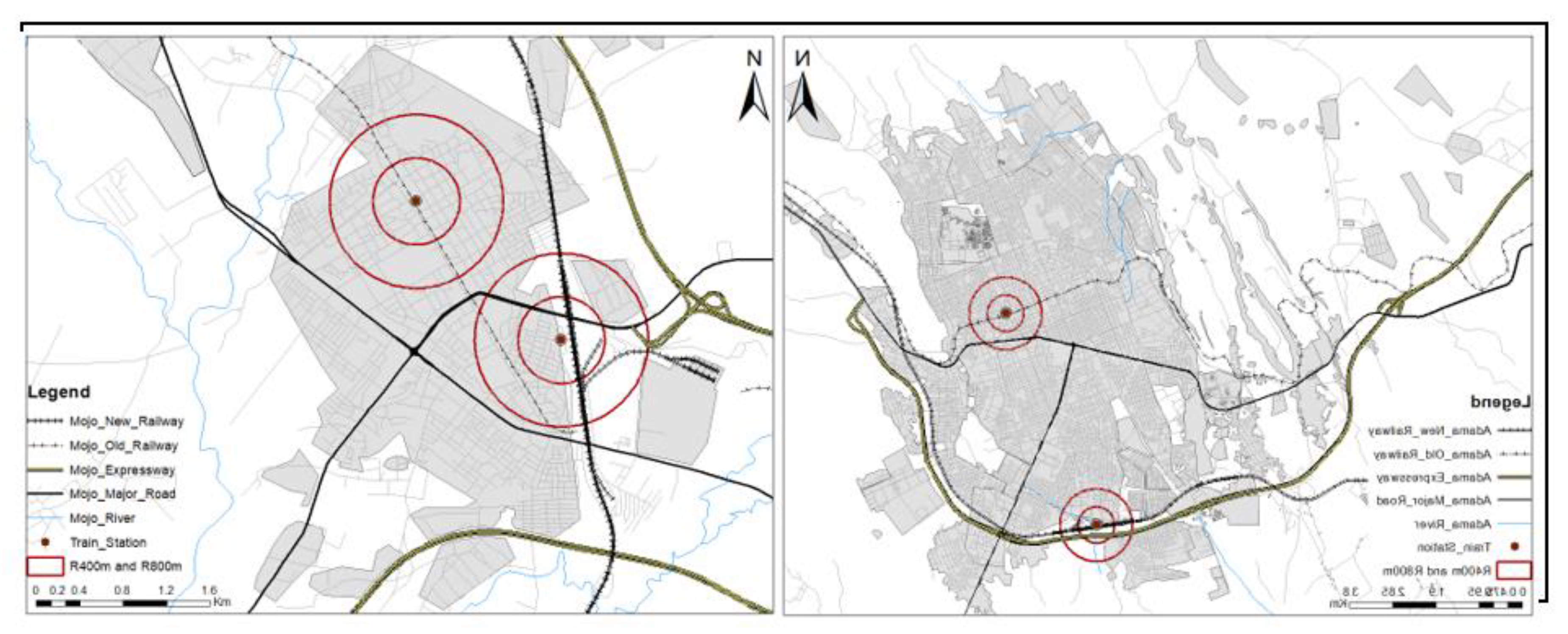

3.4.1.2. Morphological traits of Station in the Intermediate Cities

- i.

- Affordability: the distance between station and localities should be affordable for users;

- ii.

- Connectivity: the station should be linked with the nearby areas with proper road;

- iii.

- Safety: the existence of fairly level ground

- iv.

- Availability: there should be sufficient land for future expansion and development

- C. Station Location

- From Railway Engineering Perspective

- i.

- Way-side station: is located on running lines. This allows faster train to overtake a slower train. For this loop line and siding are provided.

- ii.

- Junction station: railway lines from three or more directions meet the junction has minimum of one main line and other branch line.

- iii.

- Terminal station: refers to the dead end of incoming track or the station at which railway line ends or terminate.

- 2.

- From the Nature of Locomotives

- 3.

- From the City Perspective

| Name of Urban Center | From/To | Distance in KM |

|---|---|---|

| Bishoftu | Bishoftu old railway station to new station | 3.74 |

| Mojo | Mojo old railway station to new station | 2.3 |

| Adama/Nazret | Adama old railway station to new station | 5.78 |

| Welenchiti | Old railway station to new station | 1.03 |

| Metehara | Metehara old railway station to new station | 1.71 |

| Awash Sebat Kilo | Awash Sebat Kilo old railway station to new station | 2.86 |

| Mieso | Mieso old railway station to new station | 5.13 |

| Dire Dawa | Dire Dawa old railway station to new station | 11.77 |

- D. Station Yards

3.4.2. Industrialization

| No. | Name of IP | Acquired Land (in ha) | Urban center | Specialization | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bole Lemi IP – I | 172 | Addis Ababa | Textile & Garment | Operational |

| 2 | Bole Lemi IP – II | 181 | Addis Ababa | Textile & Garment | Operational |

| 3 | Adama | 2000 | Adama | Assembling, food processing & Garment | Operational |

| 4 | Dire Dawa IP | 4186 | Dire Dawa | Assembling, food processing & Garment | Operational |

| 5 | Kilinto IP | 279 | Addis Ababa | Pharmaceutical, Medical equipment | Operational |

| 6 | Aysha IP | 1000 | Somali | Live stock | Planning stage |

| 7 | Bishoftu IP | 189 | Oromia | Planning stage | |

| 8 | ICT IP | 200 | AA | ICT | Operational |

| 9 | Addis Industry Village | 9 | AA | Garment | Operational |

| 10 | Mojo Leather Industry | 290 | Oromia | Leather | Planning stage |

| Sub-Total | 8,334 | ||||

| 1 | Eastern Industrial Zone | 500 | Oromia | Various | Operational |

| 2 | Huajian Light Industry City | 138 | AA | Shoes & Garment | Operational |

| 3 | Mojo George Shoe Industrial Park | 50 | Oromia | Leather | Operational |

| 4 | CCECC | 380 | Dire Dawa | Various | Under Construction |

| Sub-Total | 1,068 |

3.4.3. Regional Integration

- (A)

- Rural-Urban Continuum

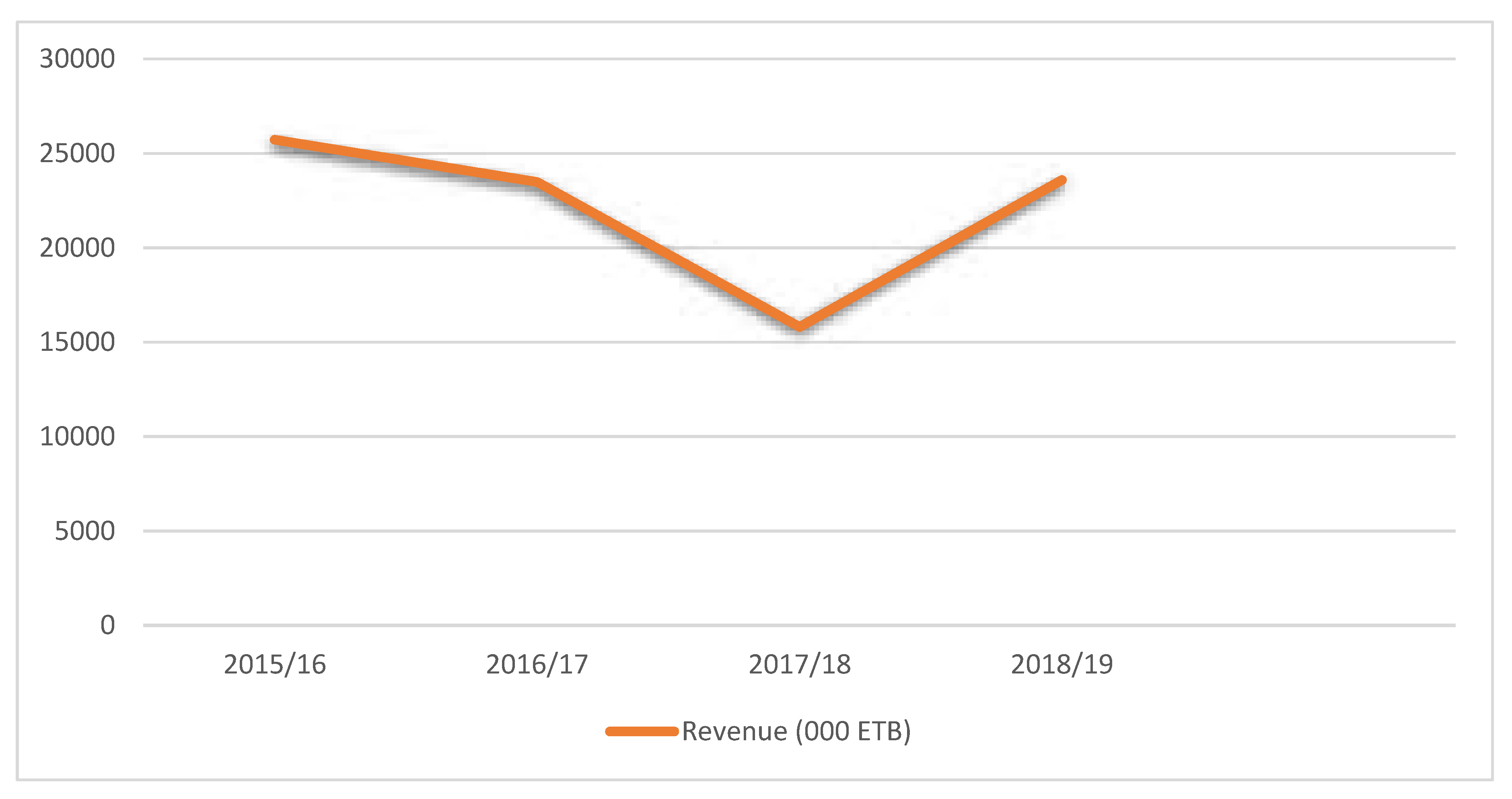

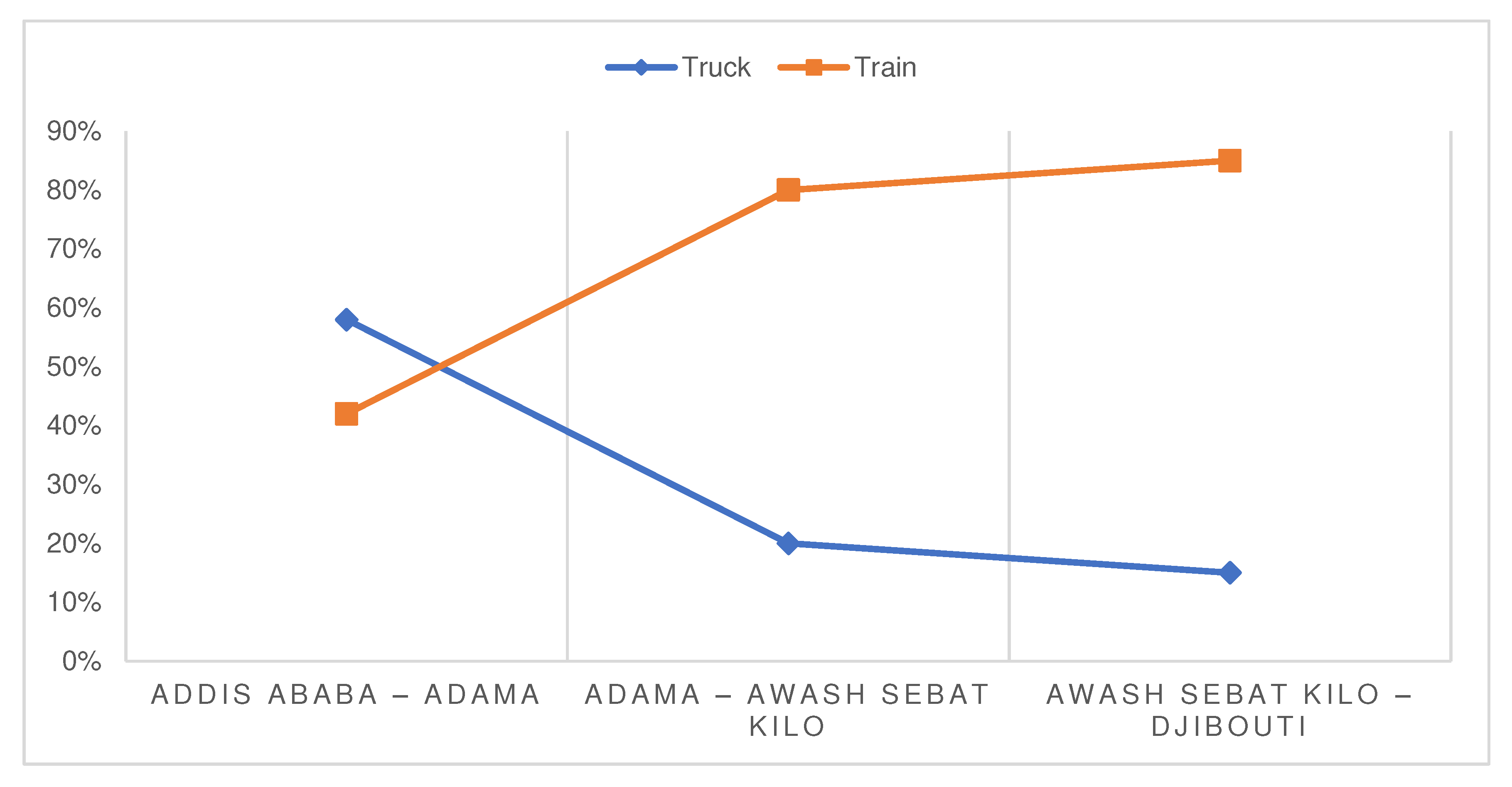

- (B) Economic/Trade Integration

| Revenue and Transport Service | Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | ||

| Revenue ('000) | Passenger | 13,010 | 18,400 | 5,218 | 6,000 | 2,450 | 2,300 | NA | 5,500 |

| Frights | 50,250 | 37,800 | 37,042 | 27,400 | 7,050 | 5,700 | NA | NA | |

| Total | 63,260 | 56,200 | 42,260 | 33,400 | 9,500 | 8,000 | |||

| Transportation Service | Passengers Travel in Km (Million) | 145 | 254 | 40 | 24 | 26 | 5 | 15 | |

| Freight carried ('000 Tons) | 285.3 | 95 | 204.3 | 123 | 76 | 2 | |||

- (C) Regional Integration

4. Measures to Optimize the Positives Impacts of Railway Corridor

- (a)

- Inadequate normative farmwork which makes institutional linkage to create sound interaction among federal, regional and city administrations; because of this limitation, almost all of the station towns do not have functional and territorial integration with the railway station.

- (b)

- Both the old and new stations had/have limited functions most of them were/are providing limited commuter related services like sealing tickets.

- (c)

- The old railway stations were constructed in the vicinity of water body without taking into account its potential to become future urban centers.

- (a)

- Hybrid regional development policy that obtains both functional and territorial integration on the corridor;

- (b)

- Sould station development approach preferably Transit Oriented Development (TOD), this will help planners to incorporate the station and its courtyards into urban strategies; they reinforce its role as a mobility hub and public place for people to meet and work.

- (c)

- The government should develop regulatory framework that promotes cooperation and collaboration in economic, social and environmental growth dynamics between ERC and station based urban center authorities.

- (d)

- Work with the private sector using PPP approach. This will help to preserve old railway station buildings as a historical building and serve as a gallery for the railway historical events as well as an economically vibrant retail area; and station courtyard with 800m radius will also serve as a mixed-use real estate area.

Conclusions

References

- A. Woodlief, "The path-dependent city," Urban affairs review, vol. 3, no. 33, pp. 405-437, 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. J. &. F. T. (. Salm, African urban spaces in historical perspective, University Rochester Press, 2005.

- Z. Beharu, A History of Modern Ethiopia: 1855 - 1991, Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press, 2002.

- R. Pankurust, "Menelik and the Utilization of foreign skills in Ethiopia," Journal of Ethiopian Studies Vol. V, No. 1 , January 1967.

- M. S. Bharti, "The sustainable development and economic impact of China’s belt and road initiative in Ethiopia," East Asia, no. 40(2), pp. 175-194, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Kozicki, "The history of railway in Ethiopia and its role in the economic and social development of this country," Studies in African Languages and Cultures, no. 49, pp. 143-170, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Laying the tracks: The political economy of railway development in Ethiopia's railway sector and implications for technology transfer, 2021.

- UN, "United Nation Department of Economic and Social Affers Population Devesion," 19 June 2023. [Online]. Available: https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- GIH, "Global Infrastructure Hub," Connectivity Across Borders: Global Practice for Cross-Border Infrastructure Project: Case Study Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, 30 November 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.gihub.org/connectivity-across-borders/case-studies/addis-ababa-djibouti-railway/. [Accessed 06 June 2023].

- D. E. Gray, Doing Research in the Real World, London : SAGE Publications, 2004.

- C. Kothari, Research Methodology: methodes and techniques, New Delhi: New Age International Publishers , 2004.

- J. Breuste, P. S., D. Haase and M. Sauerwein, Urban Ecosystems: Function, Management and Development, Berlin: Springer , 2021.

- FDRE-HOPR, Urban Landholding Registration Proclamation No. 818/2014, Addis Ababa : FDRE Birhanina Selam , 2014.

- FDRE-HOPR, Urban Planning Proclamation No. 574/2008, Addis Ababa : Federal Negarit Gazeta, Birhan Ena Selam , 2008.

- J. M. L. Torne and S. H. de Duque, Intermediary Cities: Planning and Management of Sustainable Urban Development, United Cities and Local Governments, 2016.

- Cities Alliance , The Dynamics of Systems of Secondary Cities in Africa: Urbanization, Migration and Development, Brussels : Cities Alliances and African Development Bank , 2022.

- MoUDH, Urban Plan Preparation and Implementation Strategy, Addis Ababa : Ministry of Urban Development and Housing , 2016.

- Merriam-Webster , "Corridor," Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 22 March 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/corridor. [Accessed 31 March 2023].

- D. &. F. B. Furundzic, "Infrastructure Corridor as Linear City," in International Conference on Architecture and Urban Design, 2013, June.

- C. F. Whebell, "Corridors: A theory of urban systems," Annals of the association of American geographers, no. 59 (1), pp. 1-26, 1969.

- H. &. Z. W. Priemus, "What are corridors and what are the issues? Introduction to special issue: the governance of corridors," Journal of transport geography, no. 11 (3), pp. 167-177, 2003. [CrossRef]

- G. Chen and e. S. J. d. Abreu, The Regional Impacts of High Speed Rail: A Review of Methods and Models, Lisbon : Association For European Transport and Contributors , 2011. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bahru, A History of Modern Ethiopia: 1855 - 1991, Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press, 2002.

- FDRE-COM, Ethiopian Railway Corporation Establishment Councel of Ministers Regulation No. 141/2007, Addis Ababa : Federal Negarit Gazeta, Birhan Ena Selam , 2007.

- ERC, "New Standard Gauge Railway Ethiopia/Sebeta-Djibouti/Nagad Railway Feasibility Study Part I: General Specification," Ethiopian Railways Corporation , Addis Ababa , September 2012.

- WFP Logistics Cluster , "Export Preview | Digital Logistics Capacity Assessments," Ethiopia Railway Network , 2022. [Online]. Available: https://dlca.logcluster.org/print-preview/2138. [Accessed 29 June 2023].

- ERC, "Railway Station," Ethiopian Railway Corporation , [Online]. Available: https://www.erc.gov.et/project/the-ethiopian-djibouti-railway/. [Accessed 29 June 2023].

- A. Aggarwal, "Economic Coridor," MPRA, 2020 April 6. [Online]. Available: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/110706/. [Accessed 2023 March 1].

- P. Hall and M. Tewdwr-Jones, Urban and Regional Planning (6th edt), New York : Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

- G. Collins, "Linear Planning," Forum xx, pp. 1-26, 5 March 1968.

- H. Sap, "Corridors and/or linear cities; a historic contribution to the contemporary discussion on corridor development," Faculty of Building and Architecture: Urban Design Group, Netherlands: Eindhoven University of Technology, pp. 1-15, 2007.

- H. Sap, Corridors and/or Linear Cities: a Historic Contribution to the Contemporary Discussion on Corridor Development, Eindhoven: Eindhoven University of Technology, PhD Thesis 2005, 2005.

- MoUDC, Urban Development and Construction Sector Ten Years Prespective Plan (2021-2030), Addis Ababa : Ministry of Urban Development and Consttruction, June 2020.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia , "industrialization," Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.britannica.com/science/sustainability. [Accessed 20 June 2023].

- Fundan SIRPA, "Fundan SIRPA, "Development and Industrialization in Ethiopia: Reflections from China's Experience," Fundan University School of International Relations and Public Affairs , November, 2017and Industrialization in Ethiopia: Reflections from China's Experience," Fundan University School of International Relations and Public Affairs, November, 2017.

- UCLG, Co-creating the Urban Future: The Agenda of Metropopises, Cities and Territories, Barcelona: United Cities and Local Governments, 2016.

- D. T. Mengistu, E. Gebremariam, X. Wang and S. & Zhao, "Pandemic-Resilient Urban Centers: A New Way of Thinking for Industrial-Oriented Urbanization in Ethiopia," Urban Science, no. 6 (2), pp. 1-26, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Söderbaum, "Comparative regional integration and regionalism," The Sage handbook of comparative politics, pp. 477-496, 2006. [CrossRef]

- AU; ADBG; UNECA, "Africa Regional Integration Index (ARII)," AU, 2019.

- R. (. Brears, The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures, New Zealand : Springer , 2022.

- T. G. Egziabher, "Regional development planning in Ethiopia: past experience, current initiatives and future prospects," Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, no. 16(1), 2000.

- FDRE-HoPR, The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopian Constitution Proclamation No. 1, Addis Ababa : Birhan Ena Selam-Federal Negarit Gazeta , 1995.

- CSA, "Population Projections for Ethiopia 2007 - 2037," Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa , 2013.

- J. P. Rodrigue, "Freight, Gateways And Mega-Urban Regions: The Logistical Integration Of The Bostwash Corridor 1," Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, no. 95(2), pp. 147-161, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. B. T. M. M. &. X. Y. Roberts, Transport corridors and their wider economic benefits: A critical review of the literature, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2018.

- M. &. V. E. Emerson, Optimisation of Central Asian and Eurasian trans-continental land transport corridors, 2009.

- S. H. K. S. &. B. H. P. Rahman, Regional integration and economic development in South Asia, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2012.

- H. &. Z. W. (. Priemus, "What are corridors and what are the issues? Introduction to special issue: the governance of corridors," Journal of transport geography, no. 11 (3), pp. 167-177, 2003.

- L. Mumford, " The city in history: Its origins, its transformations, and its prospects," Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, vol. 67, 1961.

- K. Lynch, "The form of cities," Scientific American, no. 190 (4), pp. 54-63, 1954.

- L. Mumford, "What Is a City?(1938)," Historic Cities: Issues in Urban Conservation, no. 8, 49, 2019.

- V. Olivera, Urban Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of Physical Form of Cities, AG Switzerland: Springer International Publishing , 2016.

- K. Kumar, "modernization," Encyclopedia Britannica, 15 June 2023 . [Online]. Available: https://www.britannica.com/topic/modernization. [Accessed 20 June 2023].

- MoUDC, Urban Centers Category and Administration Hierarchy Directive, Addis Ababa : Ministry of Urban Development and Construction , 2013.

- UCLG, "UCLG Frame Document for Intermediary Cities: Planning and management of sustainabe urban development," United Cities and Local Governments.

- MoUCH, Urban Planning and Implementation Manual, n.b.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).