Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Surface State Hamiltonian in SB formalism and the Z2 invariant

A. Surface State Hamiltonian

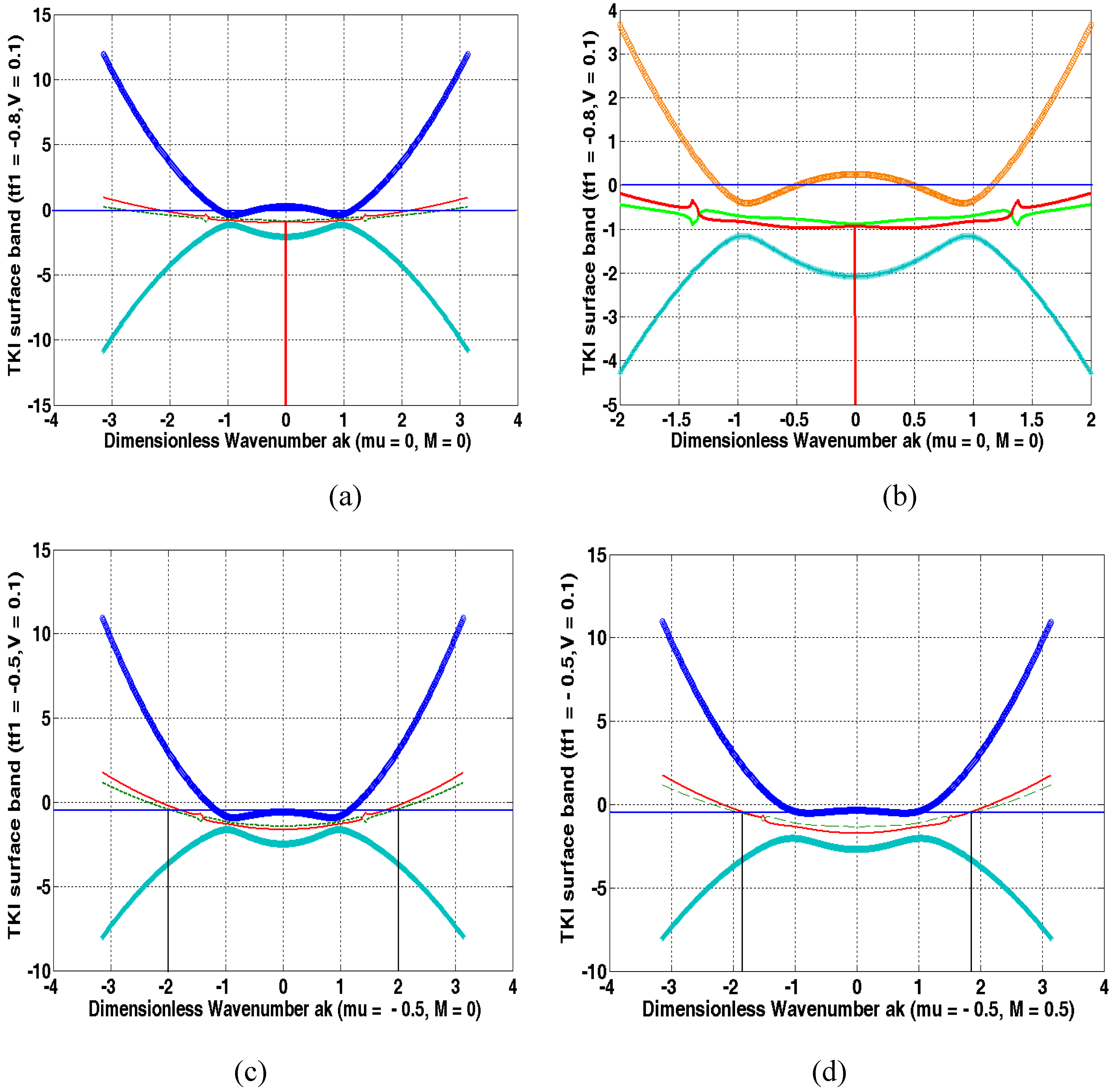

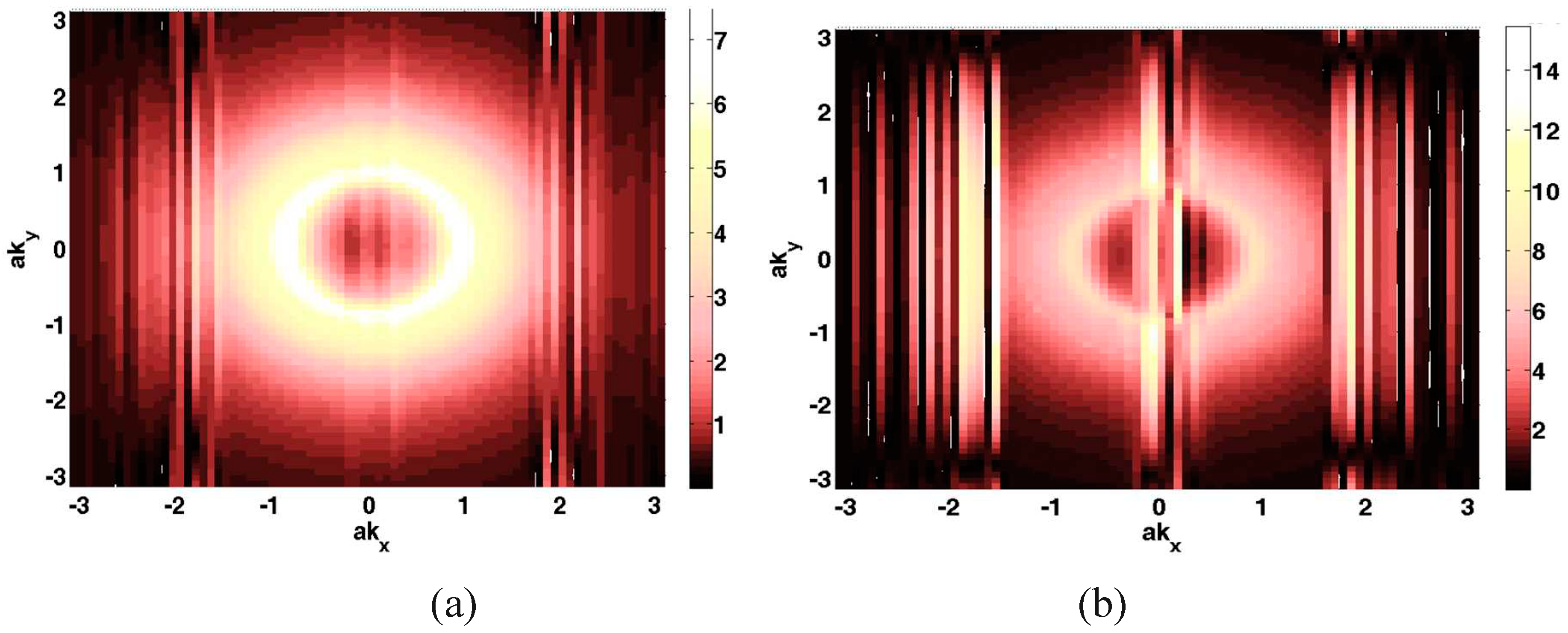

B. Surface state spectrum

C. Z2 invariant

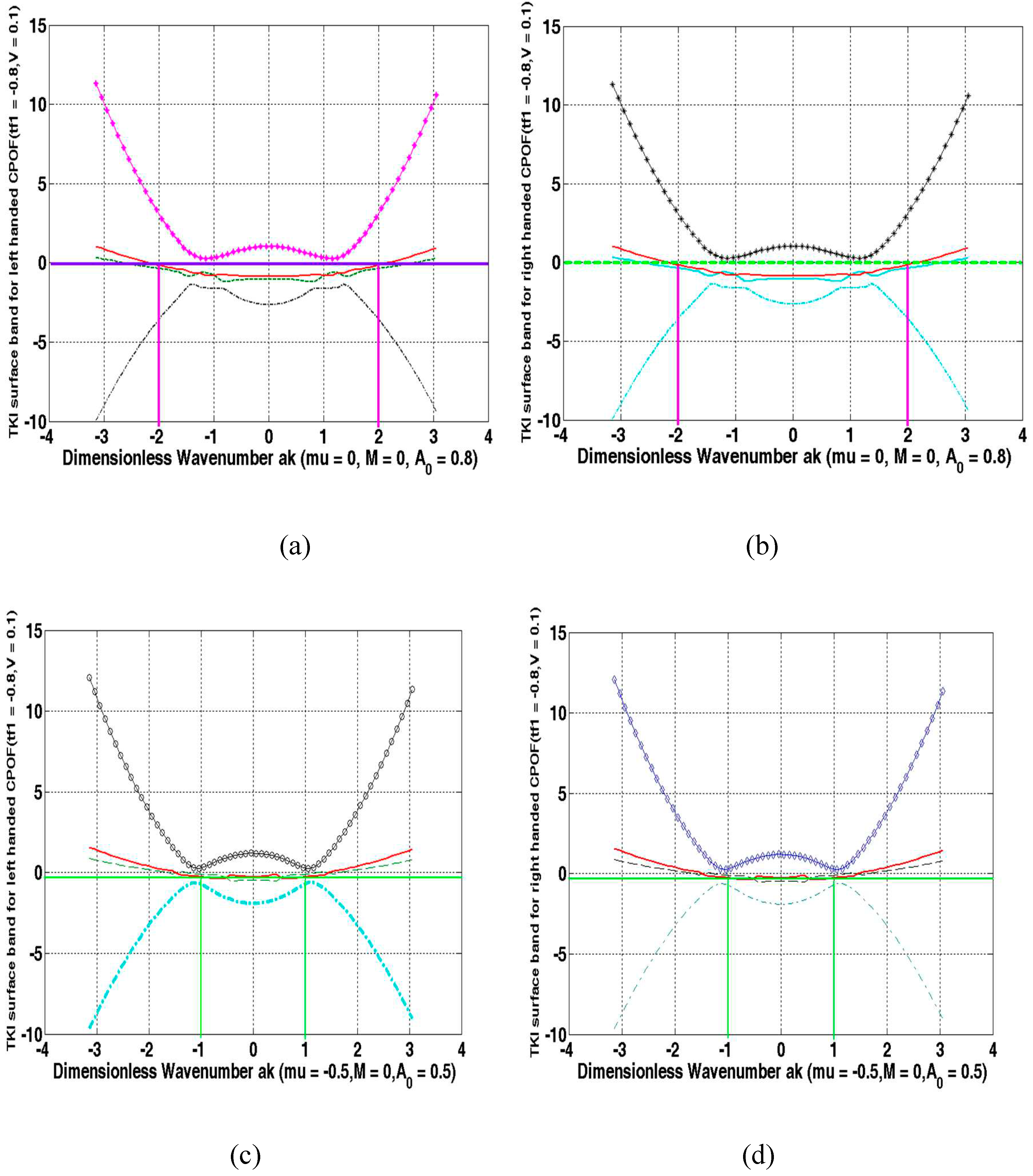

3. Floquet Theory

4. Discussion and concluding remarks

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Amorese, O. Stockert, K. Kummer, N. B. Brookes, Dae-Jeong Kim, Z. Fisk, M. W. Haverkort, P. Thalmeier, L. Hao Tjeng, and A. Severing, Phys. Rev. B 100, 241107(R) (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. R. Panday and M. Dzero, Interacting fermions in narrow-gap semiconductors with band inversion, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 33 275601(2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Stern, M. Dzero, V.M. Galitski, Z. Fisk and J. Xia, Surface-dominated conduction up to 240 K in the Kondo insulator SmB6 under strain, Nat. Mater. 16 708 (2017). [CrossRef]

- P. P. Baruselli and M. Vojta, Kondo holes in topological Kondo insulators: Spectral properties and surface quasiparticle interference, Phys. Rev. B 89, 205105 (2014). [CrossRef]

- L. Miao, C.-H. Min, Y. Xu, Z. Huang, E. C. Kotta, R. Basak, M. S. Song, B. Y. Kang, B. K. Cho, K. Kißner, F. Reinert, T. Yilmaz, E. Vescovo, Yi-D. Chuang, W. Wu, J. D. Denlinger, and L. A. Wray, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 136401 (2021).

- M. Dzero, K Sun, V. Galitski, P. Coleman, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 106408(2010); ibid Rev. B 2012, 85, 045130 ( 2012).

- D. J. Kim, S.Thomas.; T. Grant, J. Botimer, Z. Fisk, J.Xia, Sci. Rep., 3, 3150(2013).

- S. Wolgast, C. Kurdak, K. Sun, J. W. Allen, D.-J. Kim, and Z. Fisk, Phys. Rev. B 88, 180405 (2013).

- X. Zhang, N. P. Butch, P. Syers, S. Ziemak, R. L. Greene, and J. Paglione, Phys. Rev. X 3, 011011 (2013).

- D. J. Kim, J. Xia, and Z. Fisk, Nat. Mater. 13, 466 (2014).

- P. K. Biswas, M. Legner, G. Balakrishnan, M. C. Hatnean, M. R. Lees, D. M. Paul, E. Pomjakushina, T. Prokscha, A. Suter, T. Neupert, et al., Phys. Rev. B 95, 020410 (2017).

- A. P. Sakhya and K.B. Maiti , Scientific Reports volume 10, Article number: 1262 (2020).

- N. Wakeham, P. F. S. Rosa, Y. Q. Wang, M. Kang, Z. Fisk, F. Ronning, and J. D. Thompson, Phys. Rev. B 94, 035127 (2016).

- Udai Prakash Tyagi, Kakoli Bera and Partha Goswami, On Strong f-Electron Localization Effect in a Topological Kondo Insulator, Symmetry,13(12), 2245 (2021); https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13122245. [CrossRef]

- M. Legner, Topological Kondo insulators: materials at the interface of topology and strong correlations(Doctoral Thesis),ETH Zurich Research Collection(2016).Link:https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/ handle/20.500. 11850/155932/eth-49918-02.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=2.

- F.Lou, J.-Z. Zhao, H.Weng, and X. Dai, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 096401(2013).

- B. A. Bernevig, T. L. Hughes, and S.-C. Zhang: Science 314, 1757 (2006).

- L. Fu, C.L. Kane.: Time reversal polarization and a Z2 adiabatic spin pump. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195312 (2006); L. Fu, C. L. Kane, and E.J. Mele: Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106803 (2007); C. L. Kane, and E.J. Mele: Z2 Topological Order and the Quantum Spin Hall Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146802 (2005).

- S. S. Dabiri, H. Cheraghchi, and A. Sadeghi, Light-induced topological phases in thin films of magnetically doped topological insulators Physical Review B 103, 205130 (2021); H. Xu, J. Zhou, and J. Li, Light-induced quantum anomalous Hall effect on the 2D surfaces of 3D topological insulators, Advanced Science, 2101508 (2021).

- W. Zhu, M. Umer, and J. Gong, Floquet higher-order Weyl and nexus semimetals, Phys. Rev. Research 3, L032026 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. Zhou, C. Chen, and J. Gong, Floquet semimetal with Floquet-band holonomy, Phys. Rev. B 94, 075443 (2016). [CrossRef]

- H. Hubener, M. A. Sentef, U. D. Giovannini, A. F. Kemper, and A. Rubio, Creating stable Floquet–Weyl semimetals by laser-driving of 3D Dirac materials, Nat. Commun. 8, 13940 (2017). [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, H. Wang, J. Ruan, G. Yao, and H. Zhang, Engineering topological phases in the Luttinger semimetal α-Sn, Phys. Rev. B 97, 195139 (2018). [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, J.-T. Sun, and S. Meng, Engineering Dirac states in graphene: Coexisting type-I and type-II Floquet-Dirac fermions, Phys. Rev. B 99, 075121 (2019). [CrossRef]

- L. Li, C. H. Lee, and J. Gong, Realistic Floquet semimetal with exotic topological linkages between arbitrarily many nodal loops, Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 036401 (2018). [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, P. Tang, H. H¨ubener, U. De Giovannini, W. Duan, and A. Rubio, arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.06977 (2021). 22. F. Qin, R. Chen, and H.-Z. Lu, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 225001 (2022).

- H. Sambe, Steady states and quasi-energies of a quantum mechanical system in an oscillating field, Phys. Rev. A 7, 2203 (1973).

- A. A. Pervishko, D. Yudin, and I. A. Shelykh, Impact of high-frequency pumping on anomalous finite-size effects in three-dimensional topological insulators, Phys. Rev. B 97, 075420 (2018). [CrossRef]

- R. Chen, B. Zhou, and D.-H. Xu, Floquet Weyl semimetals in light-irradiated type-II and hybrid line node semimetals, Phys. Rev. B 97, 155152 (2018).; R. Chen, D.-H. Xu, and B. Zhou, Floquet topological insulator phase in a Weyl semimetal thin film with disorder, Phys. Rev. B 98, 235159 (2018). [CrossRef]

- N. Goldman and J. Dalibard, Periodically Driven Quantum Systems: Effective Hamiltonians and Engineered Gauge Fields, Phys. Rev. X 4, 031027 (2014); A. Eckardt and E. Anisimovas, High-frequency approximation for periodically driven quantum systems from a Floquet-space perspective, New J. Phys. 17, 093039 (2015). [CrossRef]

- N. Tsuji, T. Oka, and H. Aoki, Correlated electron systems periodically driven out of equilibrium: Floquet+DMFT formalism, Phys. Rev. B 78, 235124 (2008). [CrossRef]

- B. H. Wu and J. C. Cao, Noise of Kondo dot with ac gate: Floquet–Green’s function and noncrossing approximation approach,Phys. Rev. B 81, 085327 (2010). [CrossRef]

- S. Kohler, J. Lehmann, and P. H¨anggi, Driven quantum transport on the nanoscale ,Phys. Rep. 406, 379 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, Z. Xu , L. Sheng , B. Wang, D. Y. Xing , and D. N. Sheng, Time-reversal-symmetry-broken quantum spin Hall effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 066602(2011). [CrossRef]

- X.-L. Qi, Y.-S. Wu, and S.-C. Zhang, Topological quantization of the spin hall effect in two-dimensional paramagnetic semiconductors, Phys. Rev. B 74, 085308 (2006). [CrossRef]

- 36.W. Ruan, C. Ye, M. Guo, F. Chen, X.Chen, G.-Ming Zhang, and Y. Wang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 136401( 2014).

- S. Rößler, T.-Hwan Jang, D.-Jeong Kim, , and S. Wirth , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 111 (13) 4798 (2014).

- M. Neupane, N. Alidoust, S. Y. Xu, et al., Surface electronic structure of the topological Kondo-insulator candidate correlated electron system SmB6. Nat Commun 4, 2991 (2013). [CrossRef]

- J. Jiang, S. Li, T. Zhang, et al., Observation of possible topological in-gap surface states in the Kondo insulator SmB6 by photoemission. Nat Commun 4, 3010 (2013). [CrossRef]

- N. Xu, P. Biswas, J. Dil, et al., Direct observation of the spin texture in SmB6 as evidence of the topological Kondo insulator. Nat Commun 5, 4566 (2014). [CrossRef]

- F. Qin, R. Chen, and H.-Z. Lu, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 225001 (2022).

- J. W. McIver, B. Schulte, F.-U. Stein, T. Matsuyama, G. Jotzu, G. Meier, and A. Cavalleri, Light-induced anomalous hall effect in graphene, Nature Physics 16, 38 (2019). [CrossRef]

- 43.B. K. Wintersperger, C. Braun, F. N. Unal, A. Eckardt, ¨ M. D. Liberto, N. Goldman, I. Bloch, and M. Aidelsburger, Realization of an anomalous floquet topological system with ultracold atoms, Nature Physics 16, 1058 (2020). [CrossRef]

- C. S. Afzal, T. J. Zimmerling, Y. Ren, D. Perron, and V. Van, Realization of anomalous Floquet insulators in strongly coupled nanophotonic lattices, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 253601 (2020). [CrossRef]

- N. Xu, P.K. Biswas, J.H. Dil, R.S. Dhaka, G. Landolt, S. Muff, C.E. Matt, X. Shi, N.C. Plumb, M. Radović, E. Pomjakushina, K. Conder, A. Amato, S.V. Borisenko, R. Yu, H.-M. Weng, Z. Fang, X. Dai, J. Mesot, H. Ding, M. Shi, Nat. Commun. 5, 4566 (2014).

- S. Suga et al., J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 83, 014705 (2014).

- Hlawenka, P., Siemensmeyer, K., Weschke, E. et al. Samarium hexaboride is a trivial surface conductor. Nat Commun 9, 517 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02908-7. [CrossRef]

- A. Manchon, H. C. Koo, J. Nitta, S. M. Frolov, and R. A. Duine, New perspectives for rashba spin–orbit coupling, Nat. Mater. 871(2015). [CrossRef]

- Paul, C. P´epin, and M. Norman, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 026402 (2007).

- V. Alexandrov, P. Coleman, O. Erten, Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 177202 (2015).

- Y. Sato et al., Nat. Phys. 15, 954 (2019).

- Fuhrman, W.T., Chamorro, J.R., Alekseev, P. et al. Screened moments and extrinsic in-gap states in samarium hexaboride. Nat Commun 9, 1539 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04007-z. [CrossRef]

- In fact, we have the literature where it is reported that the material may show a linear T-term in the specific heat which has a coefficient that varies between 2 and 25 mJ/mole/K2 , depending upon the sample preparation [7, 16, 17]. Doping with 5% of magnetic impurities can lead to an order of magnitude increase in the heat capacity [18].

- M. E. Boulanger et al., Phys. Rev. B. 97, 245141 (2018).

- Y. Xu et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 246403 (2016).

- M. Orendáč, et al. Isosbestic points in doped SmB6 as features of universality and property tuning. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115101 (2017).

- S. Sen et al., Physical Review Research 2, 033370 (2020).

- Chowdhury, D., Sodemann, I. & Sentil, T., Nat. Commn. 9, 1766 (2018).

- G. Li et al., Science, 346, 1208–1212(2014). This study is the first report of the quantum oscillations in magnetization in Kondo insulators.

- G. Baskaran, arXiv: 1507.03477 v1 (2015).

- Knolle, J. & Cooper, N. R., Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 096604 (2017).

- Erten, O., Chang, P.-Y., Coleman, P. & Tsvelik, A. M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 057603 (2017).

- Chowdhury, D., Sodemann, I. & Sentil, T., Nat. Commn. 9, 1766 (2018).

- Shen, H. and Fu, L., Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026403 (2018).

- W. T. Fuhrman and P. Nikoli´c, Magnetic impurities in Kondo insulators: An application to samarium hexaboride, Phys. Rev. B 101, 245118 (2020).

- Z. Xiang, Y. Kasahara, T. Asaba, B. Lawson, C. Insman, Lu Chen, K. Sugimoto, S. Kawaguchi, Y. Sato, G. Li, S. Yao, Y.L. Chen, F. Iga, J. Singleton, Y. Matsuda, and L. Li, Quantum oscillations of electrical resistivity in an insulator, Science 69, 65 (2018). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).