1. Introduction

Infectious bursal disease (IBD) was first recognised in Gumboro, Delaware, USA in 1962 [

1], hence its alternative name, Gumboro disease. IBD causes considerable economic losses in the poultry industry throughout the world by inducing severe clinical signs, immunosuppression and a high mortality rate (may range from 1% to more than 50%) in infected chickens [

2]. Before 1987, IBD was satisfactorily controlled by vaccination. Since 1987, however, vaccination failures have been described in different parts of the world, due to the emergence of variant and, later on, very virulent strains of IBDV. In the USA, the new strains are characterised by an antigenic variation that shows only a slight increase in virulence and are therefore called “variant” strains [

3]. In Europe, IBDV strains still belong to classical serotype 1 strains but are characterised by a marked increase in virulence and are therefore called “hypervirulent” or “very virulent” IBDV (vvIBDV) strains [

4].

Recombinant Fowlpox viruses have been used to express genes from a number of poultry pathogens, such as Newcastle disease virus [

5,

6], Avian influenza virus [

7], Turkey rhinotracheitis virus [

8], Marek’s disease virus [

9] and IBDV [

10].

IBDV is a Birnavirus, characterised by having a bisegmented double stranded RNA genome [

2]. IBDV encodes 5 proteins in which VP2 is a capsid protein. VP2 has been identified as the host-protective antigen [

11]; hence it has been the focus of attempts to produce new vaccines by recombinant DNA technology. VP2 was expressed in the FP9 strain of Fowlpox virus [

12] to generate a recombinant vaccine, fpIBD1 [

10]. Significant levels of protection were provided by vaccination with this recombinant. fpIBD1 afforded protection against mortality, but not against damage to the bursa of Fabricius [

10]. In addition, the protective effect of the fpIBD1 vaccine was dependent on the titre of challenge virus and the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-haplotype of the vaccinated chicken [

13]. The current live attenuated vaccines in commercial use provide complete protection.

IL-18, also known as interferon-gamma-inducing factor (IGIF), is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays an important role in the development of T-helper type 1 (Th1) cells, which drive cell-mediated immune responses. As IL-18 is an inducer for Th1 response, it therefore seemed logical to investigate the efficacy of IL-18 as a vaccine adjuvant. Chicken IL-18 (chIL-18), originally identified in an EST database, was cloned and expressed [

14].

It was claimed that the ORF FPV073 (in the Fowlpox virus genome) was a homologue of human IL-18bp and an orthologue of IL-18bps from Molluscum contagiosum virus, Swinepox virus and Vaccinia virus [

15]. It was later shown that ORF FPV214 is more likely to be the correct assignment [

12]. Thus FPV214, but not FPV073, aligns with a conserved motif (97YWxxxxxFIEHL108 in humans) in the other IL-18bps. In contrast, FPV073 contains a GxGxxG nucleotide-binding motif and shows highest similarity to a tyrosine protein kinase. It seemed logical to delete IL-18bp from vector containing chIL-18 as an adjuvant. Therefore, both Fowlpox virus ORFs 073 and 214 were knocked-out, separately, from fpIBD1. ChIL-18 was then inserted into the non-essential [

16] PC-1 gene (ORF FPV030) of fpIBD1. Then the protection provided by these new vaccines was compared to the original fpIBD1, in terms of clinical signs, bursal damage and viral loads in the bursa of Fabricius following challenge with virulent IBDV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chickens

Rhode Island Red (RIR) chicks were obtained from an unvaccinated flock maintained in isolation accommodation at the Institute for Animal Health, Compton, UK. The parents were confirmed to be free of antibodies to IBDV, chicken infectious anaemia virus, Marek's disease virus, reovirus and a number of other pathogens, so the chicks used in these experiments were deemed to be free of maternal antibodies against IBDV. The experiments met with local ethical guidelines as well as those of the UK Home Office.

2.2. Viruses

Fowlpox virus FP9 derivative fpIBD1 [

10], expressing most of the IBDV F52/70 VP2 protein as a β-galactosidase fusion protein under the control of the Vaccinia virus p7.5 early/late promoter, from the BglII insertion site in ORF FPV002, was from laboratory stocks. fpIBD1 was grown on chicken embryo fibroblast (CEF) cells in the presence of 1X 199 medium (Sigma).

The vIBDV strain F52/70 [

17] was used. The titre of virus stock was kindly determined by Dr Adriaan van Loon (Intervet BV, The Netherlands) [

18]. Based on earlier studies, the dose of virus selected was 102.3 EID50 vIBDV strain F52/70, which can overcome the protection provided by fpIBD1 and cause bursal damage, measured as the bursal lesion score in 2-3 week-old RIR chicks (Davison TF, personal communication).

2.3. Generation of novel fpIBD1 recombinants

fpIBD1 mutants carrying only deleted forms of the putative IL-18bp genes were isolated by trans-dominant selection [

19] using selection for the Escherichia coli guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (gpt) gene and checked by PCR, essentially as described previously [

16]. Deleted recombination constructs, containing 50 bp from either end of Fowlpox virus ORFs 073 and 214 as well as 500 bp flanking sequences, were, however, assembled by two-stage overlapping PCR before insertion into the BamHI and HindIII restriction sites of vector pGNR [

16]. The constructs were then transfected, using Lipofectin (Invitrogen), into CEF infected with fpIBD1. After overnight incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the culture medium was discarded and replaced with 1X 199 medium + 2% new born bovine serum (NBBS) containing mycophenolic acid, xanthine and hypoxanthine (MXH) solution and reincubated for 2-4 days until a cytopathic effect was apparent. The virus was released by freeze/thawing the culture three times then plaqued out under MXH selection.

Gpt+ recombinant clones were plaque-purified three times in MXH selective medium then further purified without selection until they became gpt- (as determined by failure to plaque under MXH selective medium), that was confirmed by PCR.

For production of recombinants expressing chIL-18, a recombination vector was constructed. Briefly, pGEM-T::chIL-18 was digested with NotI, chIL-18 was then inserted into pEFgpt12S (containing S promoter). Sp+chIL-18 was then inserted into the PC-1 plasmid (pFPV-PC-1) to result in pFPV-PC-1::Sp+chIL-18, which was the target clone in which the chIL-18 gene, under the control of a synthetic early-late promoter, was inserted into the non-essential PC-1 gene (ORF FPV030) in a plasmid carrying the gpt gene under the control of the Vaccinia virus p7.5 promoter. CEF infected with parental fpIBD1, fpIBD1Δ073 and fpIBD1Δ214 viruses were then transfected with the pFPV-PC-1::S-promoter/chIL-18 plasmid. Gpt+ recombinants were selected and plaque purified three times. Insertion of the expression and selection cassette into the PC-1 gene was confirmed by PCR.

The six different recombinant viruses were titrated. Viruses carrying the gpt reporter gene (i.e. those that contain chIL-18) always had lower titres (

Table 1).

2.4. Experimental design

Chicks received an initial vaccination at 1 week of age with 107 pfu fpIBD1 or manipulated fpIBD1 in a 50 μl volume. The inoculum was placed on the wing-web and the skin punctured 30 times over an area of 2 mm2 with a 21-gauge hypodermic needle. The same procedure was repeated two weeks later to provide a booster vaccination. Chickens were challenged 10 days after final vaccination with 102.3 EID50 IBDV strain F52/70 in a total volume of 100 μl by the intranasal route (50 μl in each nostril). For RNA preparation, blood samples (50 μl) were taken from a wing vein immediately into 350 μl RTL buffer every day after challenge (from the infected unvaccinated group). Five days after challenge, all birds were killed and the bursae removed for RNA, immunohestochemistry and H&E staining.

2.5. Sample processing

2.5.1. RNA extraction

Bursal tissue (~30 mg) was homogenised using a Bead mill (Retsch MM300). Briefly, the bursal tissue was placed in a 2 ml Safe-lock Eppendorf tube with 600 μl lysis buffer RLT. A 5mm stainless steel bead was added per tube. The tubes were placed in adaptors for the bead mill and run for 4 min at 20 Hz. Total RNA was then prepared from the homogenised tissues and the blood using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Purified RNA was eluted in 50 μl RNase-free water and stored at -70°C.

2.5.2. Frozen sections for immunohistochemical staining

Each bursal sample was put on a 2.5 cm2 cork tile and covered with Tissue-Tek® O.C.TTM Compound. The samples were then snap-frozen in a dry-ice/iso-pentane bath and transferred to liquid nitrogen. Frozen blocks were then removed from the liquid nitrogen, wrapped in aluminium foil and stored at -70oC. Sections (6-8 μm) were then cut from these blocks for immunohistochemistry staining using a cryostat, picked up onto glass slides, then fixed in acetone for 10 min and air-dried. Staining was then carried out using a Vectastain® ABC αmouse IgG HPR staining kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), following the manufacture’s instructions. The monoclonal antibodies used were R63 [

3] for IBDV and AV20 [

20] for B cells.

2.5.3. H&E staining

Each bursal section from every bird was put into 40 ml formalin and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to look for bursal damage.

2.6. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was carried out for IBDV and 28S [

21]. IBDV-specific oligonucleotides were identified from genomic segment A [

22]. The fluorescently labelled probes were labelled with the reporter dye 5-carboxyfluoroscein (FAM) at the 5′ end and the quencher N,N,N’,N’–tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine (TAMRA) at the 3′ end. Specific primers were designed to closely flank the probe. Primers and probes sequences are given in

Table 2.

RT-PCR was carried out using reagents from the TaqMan® EZ RT-PCR kit (PE Applied Biosystems). Amplification and detection of specific products were undertaken using the ABI PRISM™ 7700 Sequence Detection System with the following cycle profile: 1 cycle of 50°C for 2 min, 1 cycle of 96°C for 5 min, 1 cycle of 60°C for 30 min, 1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min and 40 cycles of 94°C for 20 sec and 59°C for 1 min. Quantification was based on the increased fluorescence detected by the ABI PRISM™ 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems) due to hydrolysis of the target-specific probes by the 5′ nuclease activity of the rTth DNA polymerase during PCR amplification. A passive reference dye ROX (present in the EZ reaction buffer), which is not involved in amplification, was used to correct for fluorescent fluctuations resulting from changes in the reaction conditions for normalisation of the reporter signal. Results are expressed in terms of the threshold cycle value (Ct), the cycle at which the change in the reporter dye (ΔRn) passes a significance threshold.

2.7. Construction of standard curves for quantitative PCR and RT-PCR assays

To generate standard curves for the 28S rRNA-specific reaction, total RNA, extracted from stimulated splenocytes, was serially diluted in sterile RNase-free water and dilutions made from 10-1 to 10-5. To generate standard curves for the IBDV, total RNA was extracted from 50 μl IBDV stock and serially diluted similarly. Regression analysis of the mean values of 6 replicate RT-PCRs for the log10 diluted RNA was used to generate standard curves.

3. Results

3.1. Protection from IBDV challenge by the recombinant vaccine fpIBD1 and the new viral constructs

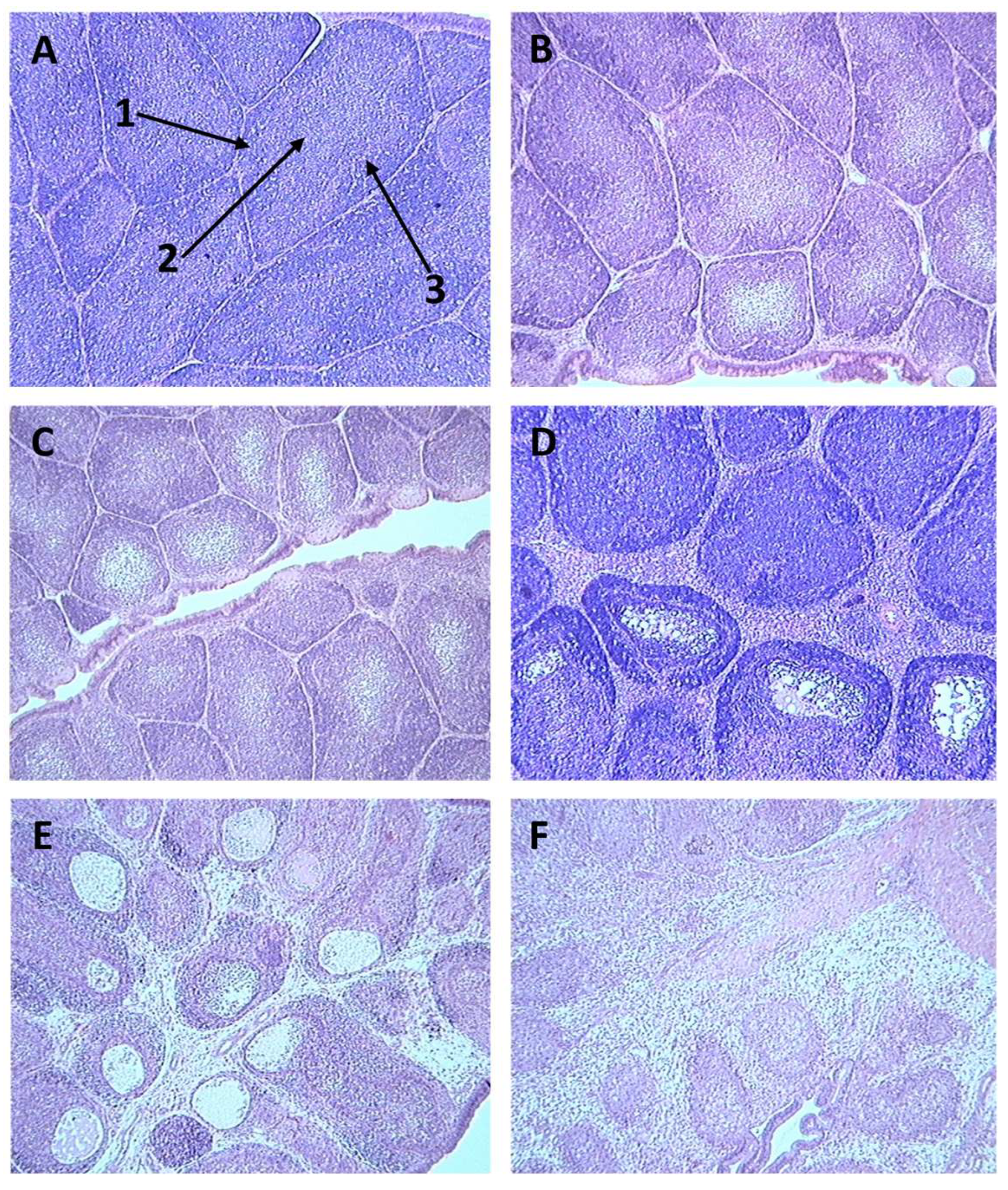

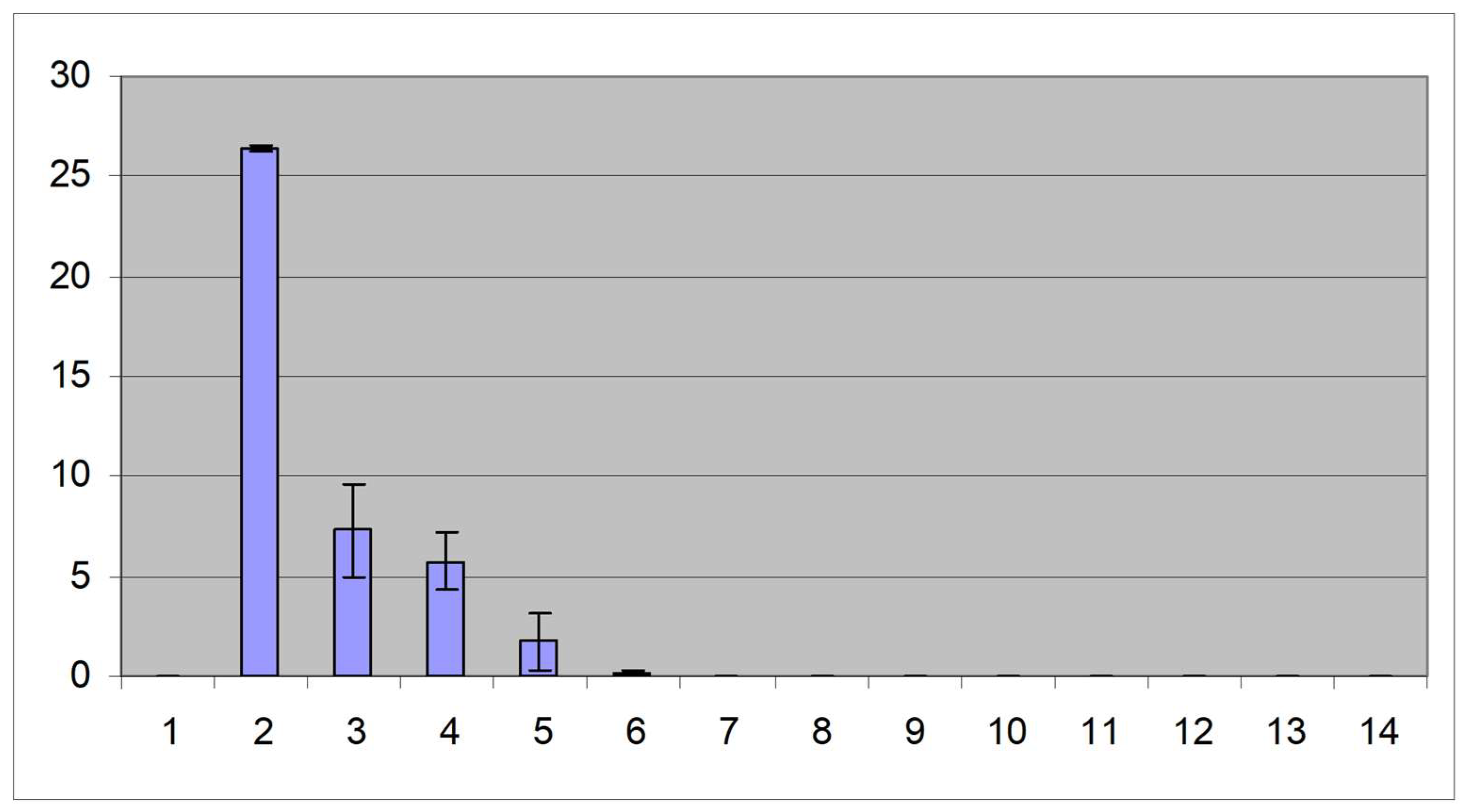

Within 2 days, birds vaccinated with parental fpIBD1 or manipulated fpIBD1 developed pocks, at the site of inoculation, which disappeared by 10 days. Protection from virulent IBDV challenge by the parental recombinant vaccine fpIBD1 and the altered fpIBD1 was measured by the appearance of IBD clinical signs, using the bursal damage scoring index of Muskett et al. [

23] (

Table 3 &

Figure 1), and viral loads (IBDV) in the bursa, using immunohistochemical staining and real-time quantitative RT-PCR, at 5 days post-infection (dpi).

Severe bursal damage was observed for all infected, unvaccinated birds (

Table 3). Four out of five (80%) fpIBD1-vaccinated birds were not protected. Three birds out of five (60%) vaccinated with fpIBD1Δ073 were not protected. Only one bird out of five (20%) vaccinated with fpIBD1Δ214 was not protected. Interestingly, no bursal damage was seen for all birds vaccinated with viral constructs containing IL-18.

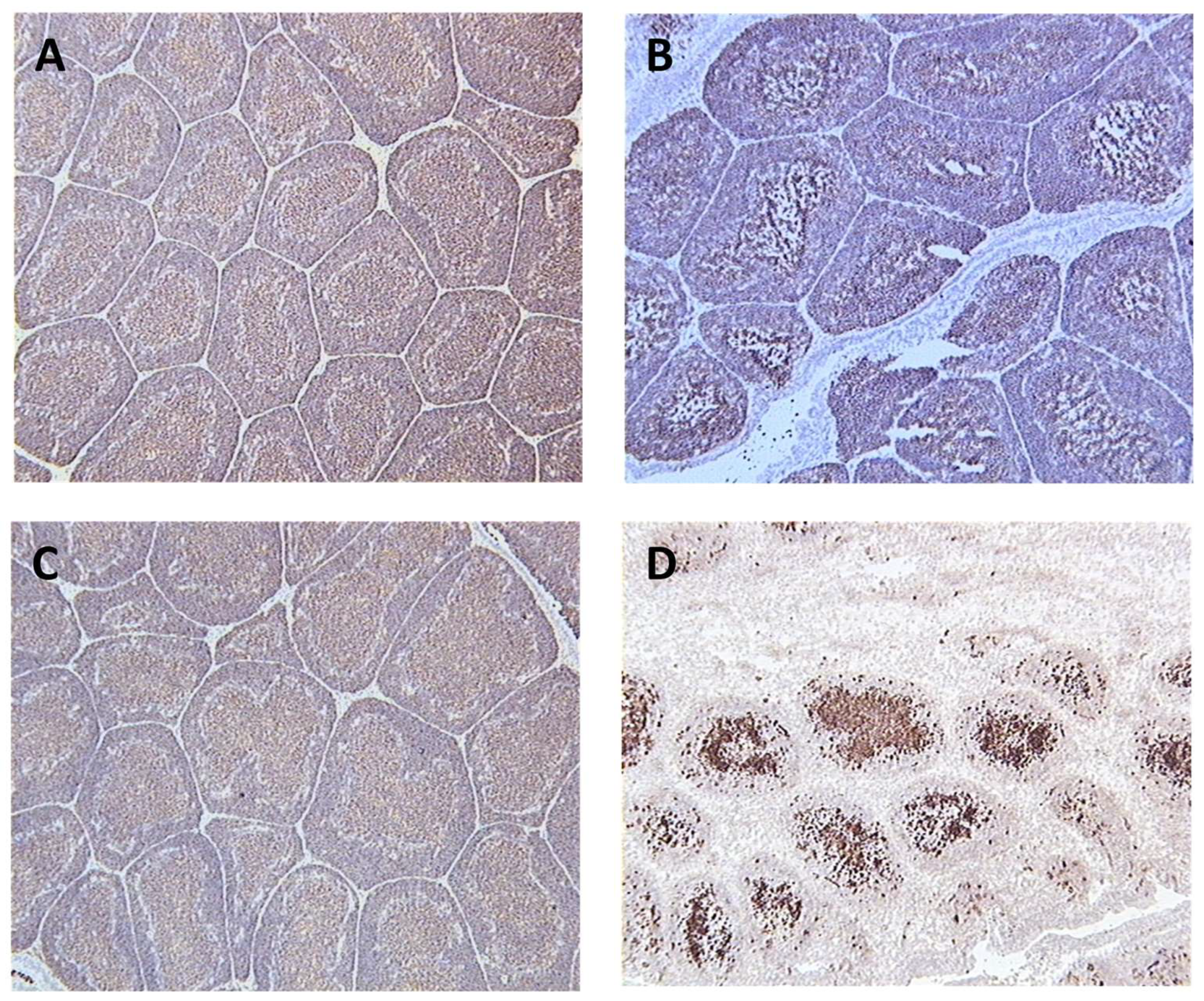

Massive depletion of B cells was observed in the bursae of infected, unvaccinated birds. Some B cell depletion was seen in the bursae of birds vaccinated with fpIBD1. Very little B cell depletion was seen in the bursae of birds that were vaccinated with the knockout viruses 073 and 214 and no B cell depletion was observed in the bursae of birds that were vaccinated with the viruses that contained chIL-18 (

Figure 2).

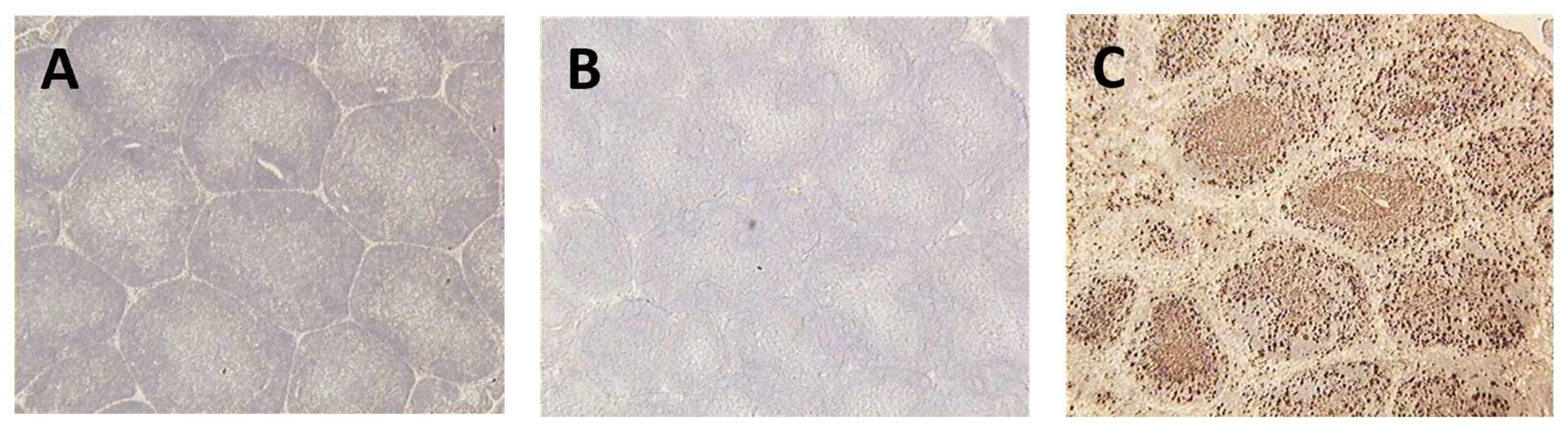

3.2. Detection of IBDV using immunohistochemistry

The bursae of unvaccinated and challenged chickens were swamped with the virus. Massive destruction of the bursae had taken place. In contrast, no virus was detected in the bursae of vaccinated chickens (

Figure 3).

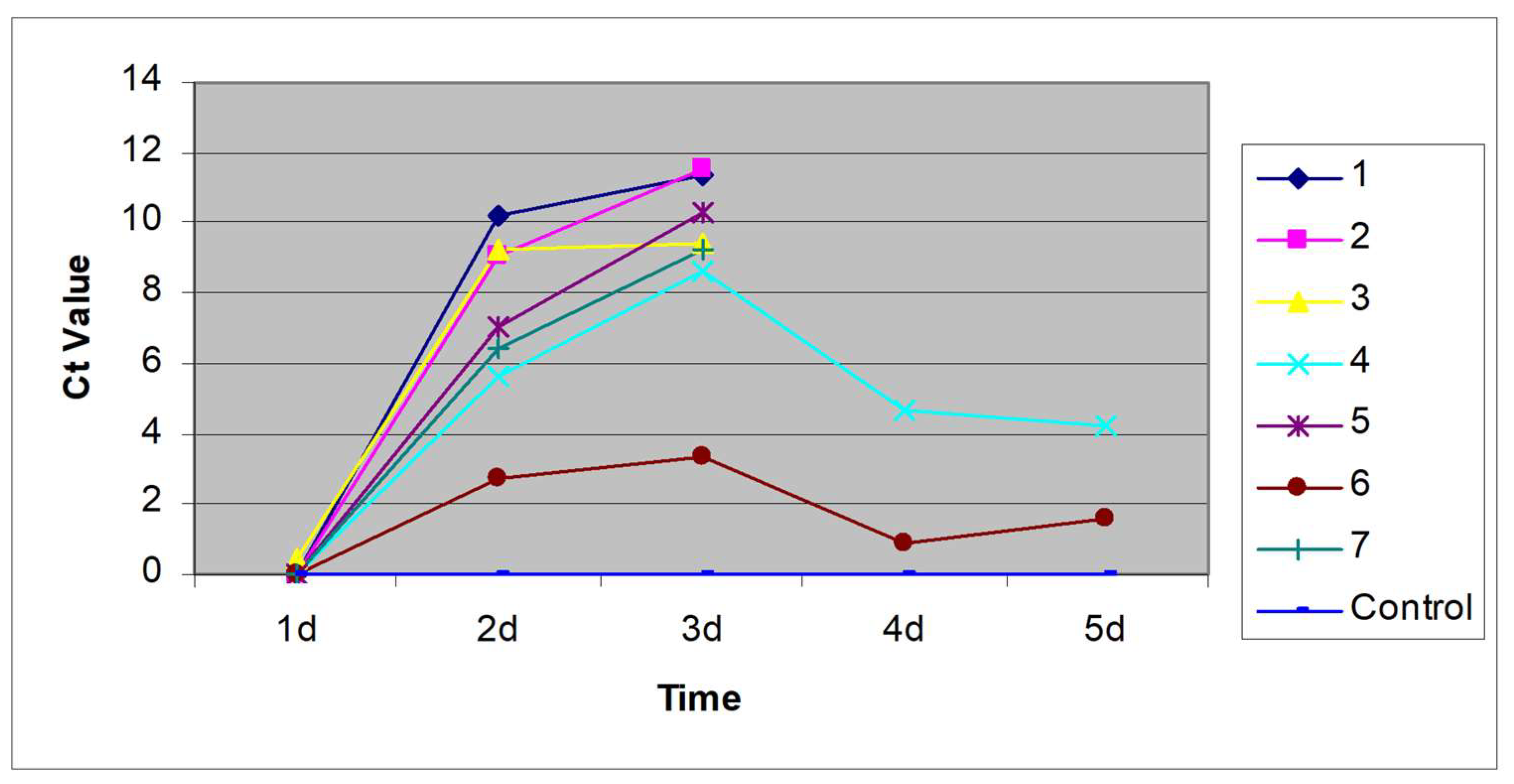

3.3. Detection of IBDV using real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Viral RNA in 50 μl of whole blood extracted from infected chickens (unvaccinated) over the first 5 dpi with vIBDV strain F52/70 (every 24 h) was quantified. The total number of birds in this group was 7 birds. 5 birds came to the clinical end-point by 3 dpi and 2 birds survived until the end of the experiment (5 dpi). The results show that IBDV levels in the blood reach a peak at 3 dpi. The two surviving birds had lower levels of IBDV in the blood compared to the other birds (

Figure 4).

IBDV was detected in the bursa at very high levels in infected, unvaccinated birds (

Figure 5). There was a low level of IBDV in the bursae of birds vaccinated with fpIBD1 or with fpIBD1Δ073 and lower levels still in the bursae of birds vaccinated with fpIBD1Δ214. Interestingly, hardly any IBDV was detected in the bursae of birds vaccinated with fpIBD1::IL-18, and even more interestingly, no virus was detected in the bursae of birds vaccinated with either fpIBDIΔ073::IL-18 or fpIBD1Δ214::IL-18 (

Figure 5). The experiment was repeated and similar results were obtained.

4. Discussion

In previous studies, the recombinant vaccine fpIBD1 protected outbred Rhode Island Red chickens against mortality induced by virulent (F52/70) and very virulent (CS89) strains of IBDV, but not against damage to the bursa of Fabricius [

10]. Successful vaccination with fpIBD1 is dependent on the titre of challenge virus, for high titres of challenge virus were able to overcome protection induced by fpIBD1, whereas challenge with a low titre of virus did not [

13]. Hence, we decided to use a high titre (102.3 EID50) of IBDV strain F52/70 to overcome the protection provided by the original fpIBD1 and to cause bursal damage.

Cell mediated immunity is involved in protection against challenge with IBDV after vaccination with fpIBD1, as there are no detectable antibodies against IBDV after vaccination and before challenge with IBDV, although there are high levels of antibodies against Fowlpox virus [

10,

13]. IBDV strain F52/70 induces a Th1 response following infection. IL-18 is an inducer of the Th1 response. It therefore seemed logical to investigate the efficacy of IL-18 as a vaccine adjuvant with fpIBD1. Including chIL-18 in the fpIBD1 vaccine could result in more rapid clearance of the vaccine from the host, again with alteration in the magnitude of the immune response to the vaccine.

The Fowlpox virus genome contains several immunomodulatory genes, including an postulated IL-18bp [

12,

15]. It seemed logical to delete this gene from vectors containing chIL-18 as an adjuvant. However, Fowlpox virus presumably uses its vIL-18bp as part of a strategy to avoid the host immune response. Deleting the vIL-18bp gene might, therefore, have had an adverse effect on the persistence of the fpIBD1 vaccine in the host and could, therefore, have altered the magnitude of the immune response to the vaccine.

The data indicate that chIL-18 can act as a vaccine adjuvant. Despite the use of a challenge dose of IBDV high enough to overcome protection and cause bursal damage in birds vaccinated with fpIBD1, there was no bursal damage in birds vaccinated with fpIBD1::IL-18, fpIBD1Δ073::IL-18 and fpIBD1Δ214::IL-18 (

Figure 1). Furthermore, no IBDV was detected in the bursae of birds vaccinated with fpIBD1Δ073::IL-18 and fpIBD1Δ214::IL-18 (

Figure 5). The results also indicate that, as suggested [

12], ORF214 is the better candidate for IL-18bp, as fpIBD1Δ214 showed significantly better protection than fpIBD1 or fpIBD1Δ073 (

Figure 5 &

Table 3).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we believe our data indicate that chIL-18 can act as a vaccine adjuvant with fpIBD1 when challenging with a virulent strain of IBDV. It will be interesting to investigate if chIL-18 can act similarly when challenging with a very virulent strain of IBDV using the same experimental model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E. and P.K.; methodology, I.E.; validation, I.E., L.R., M.S. and P.K.; investigation, I.E.; data curation, I.E., L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E.; writing—review and editing, .I.E., L.R., M.S. and P.K.; supervision, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Libyan Government through the Libyan Embassy in London as a support for Ibrahim Eldaghayes’s PhD.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. The animal study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Institute for Animal Health and the United Kingdom Government Home Office.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript. Any additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stephen Laidlaw, Fred Davison, Colin Butter, the people in the EAH especially Don Hoopre, the Media people especially Richard Oaks and the Histology lab people for their help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cosgrove, A. An apparently new disease of chickens - Avian Nephrosis. Avian Dis. 1962, 6, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eterradossi, N.; Saif, Y.M. Infectious bursal disease. In Diseases of Poultry, 14th ed.; David E. Swayne, Martine Boulianne, Catherine M. Logue, Larry R. McDougald, Venugopal Nair, David L. Suarez, Sjaak de Wit, Tom Grimes, Deirdre Johnson, Michelle Kromm, Teguh Yodiantara Prajitno, Ian Rubinoff, Guillermo Zavala, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2020; pp. 257–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Zheng, S.J. Genetic Insight into the Interaction of IBDV with Host-A Clue to the Development of Novel IBDV Vaccines. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Berg, T.P.; Gonze, M.; Meulemans, G. Acute infectious bursal disease in poultry: Isolation and characterisation of a highly virulent strain. Avian Pathol. 1991, 20, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, R.; Koopman, R.; García, M.; Armour, N.; Dunn, J.R.; Barbosa, T.; Martinez, A. Review of Poultry Recombinant Vector Vaccines. Avian Dis. 2021, 65, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; Edbauer, C.; Rey, S.A.; Bouquet, J.F.; Norton, E.; Goebel, S.; et al. Newcastle disease virus fusion protein expressed in a fowlpox virus recombinant confers protection in chickens. J. Virol. 1990, 64, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, M.F.; Bertran, K.; Lee, D.H.; Killmaster, L.; Stephens, C.B.; Spackman, E.; Sa E Silva, M.; Atkins, E.; Mebatsion, T.; Widener, J.; Pritchard, N.; King, H.; Swayne, D.E. Efficacy of novel recombinant fowlpox vaccine against recent Mexican H7N3 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Vaccine. 2019, 37, 2232–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingzhong, Y.; Barrett, T.; Brown, T.D.; Cook, J.K.; Green, P.; Skinner, M.A.; et al. Protection against turkey rhinotracheitis pneumovirus (TRTV) induced by a fowlpox virus recombinant expressing the TRTV fusion glycoprotein (F). Vaccine 1994, 12, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.F.; Bacon, L.D.; Yoshida, S.; Yanagida, N.; Zhang, H.M.; Witter, R.L. The efficacy of recombinant fowlpox vaccine protection against Marek's disease: Its dependence on chicken line and B haplotype. Avian Dis. 2004, 48, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, C.D.; Peters, R.W.; Cook, J.K.; Reece, R.L.; Howes, K.; Binns, M.M.; et al. A recombinant fowlpox virus that expressed the VP2 antigen of infectious bursal disease virus induces protection against mortality caused by the virus. Arch. Virol. 1991, 120, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, K.J.; Erny, K.; Crooks, J. A conformational immunogen on VP2 of infectious bursal disease virus that induce virus-neutralizing antibodies that passively protect chickens. J. Gen. Virol. 1989, 70, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, S.M.; Skinner, M.A. Comparison of the genome sequence of FP9, an attenuated, tissue culture-adapted European strain of Fowlpox virus, with those of those virulent American and European viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 85, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, I.; Davison, T.F. Protection from IBDV-induced bursal damage by a recombinant fowlpox vaccine, fpIBD1, is dependent on the titre of challenge virus and chicken genotype. Vaccine 2000, 18, 3230–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, K.; Puehler, F.; Baeuerle, D.; Elvers, S.; Staeheli, P.; Kaspers, B.; et al. cDNA cloning of biologically active chicken interleukin-18. J Interferon Cyt. Res. 2000, 20, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, C.L.; Tulman, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of fowlpox virus. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3815–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, S.M.; Anwar, M.A.; Thomas, W.; Green, P.; Shaw, K.; Skinner, M.A. Fowlpox virus encodes nonessential homologs of cellular alpha-SNAP, PC- 1, and an orphan human homolog of a secreted nematode protein. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 6742–6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooruzzaman, M.; Hossain, I.; Rahman, M.M.; Uddin, A.J.; Mustari, A.; Parvin, R.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Islam, M.R. Comparative pathogenicity of infectious bursal disease viruses of three different genotypes. Microb Pathog. 2022, 169, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, J.; Rautenschlein, S. Infectious bursal disease virus' interferences with host immune cells: What do we know? Avian Pathol. 2022, 51, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, L.S.; Earl, P.L.; Moss, B. Generation of Recombinant Vaccinia Viruses. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2017, 89, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, C.J.; Vervelde, L.; Davison, T.F. Identification of chicken Bu-1 alloantigens using the monoclonal antibody AV20. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1996, 55, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techera, C.; Tomás, G.; Panzera, Y.; Banda, A.; Perbolianachis, P.; Pérez, R.; Marandino, A. Development of real-time PCR assays for single and simultaneous detection of infectious bursal disease virus and chicken anemia virus. Mol Cell Probes. 2019, 43, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, C.D.; Spies, U.; Shaw, K.; Peters, R.W.; Papageorgiou, A.; Muller, H.; et al. A comparison of the sequence of segment A of four infectious bursal disease virus strains and identification of a variable region in the VP2. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskett, J.C.; Hopkins, I.G.; Edwards, K.R.; Thornton, D.H. Comparison of two infectious bursal disease strains: Efficacy and potential hazards in susceptible and maternally immune birds. Vet. Rec. 1979, 104, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).