Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

15 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

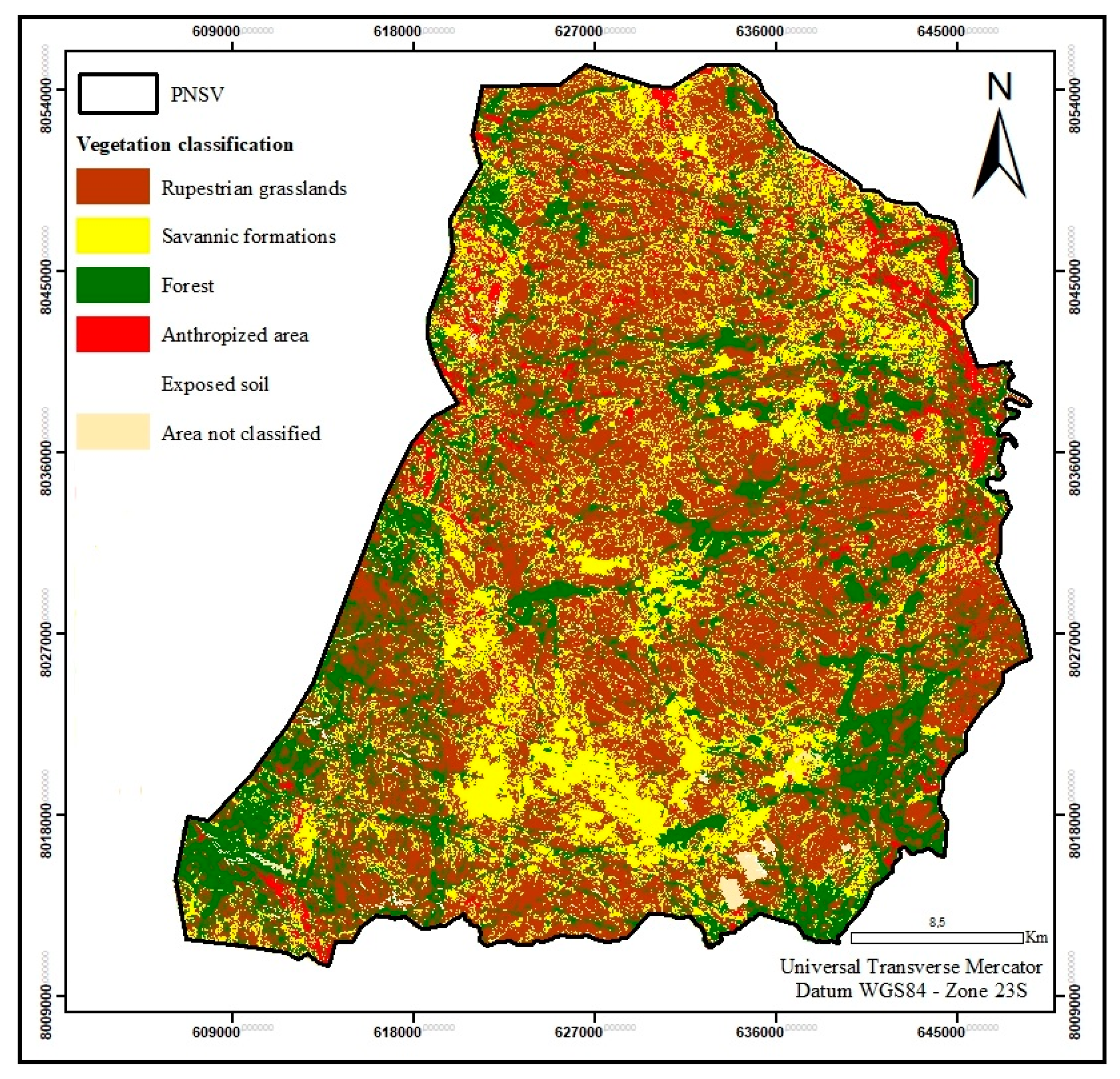

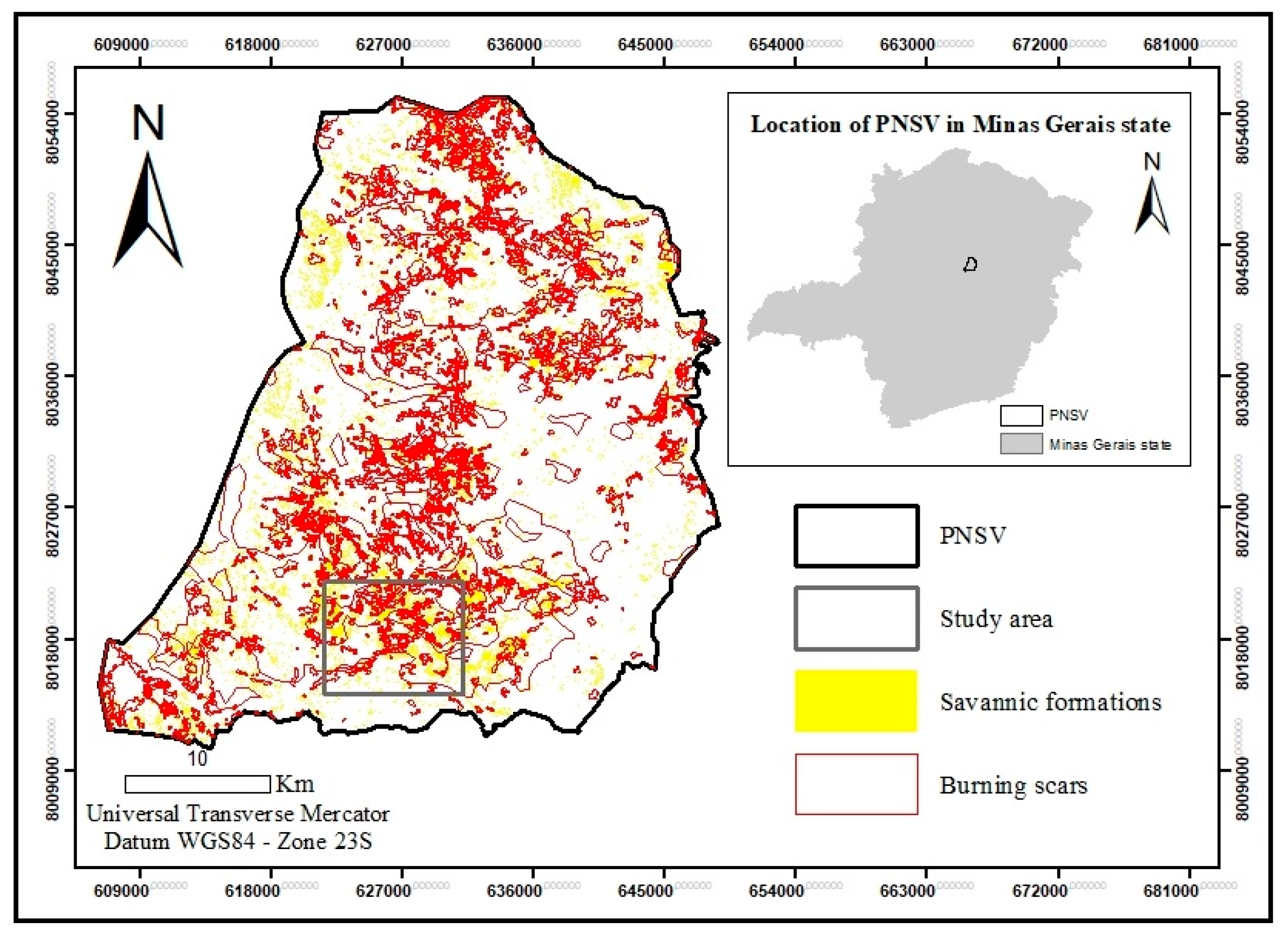

2.1. Study site

2.2. Selection of study areas

2.3. Data collection and analysis

2.3.1. Floristic composition and structure of the plant community

2.3.2. Functional characterization of plant species

2.3.3. Dynamic landscape configuration

3. Results

3.1. Vegetation analysis

| Family/Species | Area | Classification | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | Life form | Post-fire growth capacity | ||||||

| Annonaceae | IV | Rank | IV | Rank | IV | Rank | IV | Rank | IV | Rank | ||

| Annona crassiflora | 22.04 | 6 | 0.00 | 4.56 | 11 | 3.27 | 11 | 5.24 | 13 | Tree | no | |

| Annona emarginata | 0.00 | 6.30 | 9 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.82 | 22 | Tree | ||||

| Apocynaceae | ||||||||||||

| Aspidosperma tomentosum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.87 | 7 | 3.09 | 18 | Tree | yes | |||

| Asteraceae | ||||||||||||

| Eremanthus erythropappus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35.32 | 2 | 17.83 | 2 | Tree | ||||

| Baccharis dracunculifolia | 0.58 | 18 | 12.8 | 5 | 7.63 | 6 | 1.16 | 18 | 5.06 | 14 | Shrub | |

| Lychnophora ericoides | 0 | 0 | 6.84 | 7 | 0 | 1.48 | 24 | Shrub | ||||

| Lychnophora pinaster | 2.51 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.63 | 23 | Shrub | ||||

| Micania neurocaula | 0 | 1.50 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0.42 | 37 | Shrub | ||||

| Bignoniaceae | ||||||||||||

| Jacaranda sp. | 0.00 | 0.64 | 26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 48 | Tree | ||||

| Calophyllaceae | ||||||||||||

| Kielmeyera coriacea | 0.00 | 15.50 | 4 | 0.00 | 5.39 | 10 | 5.68 | 12 | Tree | yes | ||

| Kielmeyera lathrophyton | 30.74 | 2 | 1.05 | 22 | 52.04 | 1 | 3.11 | 12 | 15.82 | 6 | Tree | yes |

| Celastraceae | ||||||||||||

| Salacia crossifolia | 0.00 | 16.99 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.85 | 15 | Shrub | yes | |||

| Ericaceae | ||||||||||||

| Agarista olerifolia | 0.00 | 0.32 | 31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 55 | Tree | ||||

| Erythroxylaceae | ||||||||||||

| Erythroxylum campestre | 0.00 | 5.26 | 11 | 1.42 | 13 | 0.00 | 1.88 | 21 | Tree | no | ||

| Erythroxylum deciduum | 32.75 | 1 | 8.86 | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.34 | 9 | Tree | yes | ||

| Erythroxylum suberosum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 21 | 0.25 | 43 | |||||

| Erythroxylum tortuosum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 20 | 0.26 | 42 | |||||

| Fabaceae | ||||||||||||

| Acosmium dasycarpum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 4 | 7.71 | 10 | Tree | yes | |||

| Bauhinia holophylla | 4.47 | 10 | 0.00 | 34.19 | 3 | 11.29 | 6 | 12.11 | 7 | Shrub | ||

| Chamaecrista cathartica | 0.00 | 8.59 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.43 | 20 | Shrub | ||||

| Dalbergia miscolobium | 18.84 | 7 | 0.30 | 32 | 24.49 | 4 | 0.00 | 16.94 | 5 | Tree | yes | |

| Machaerium | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 20 | 2.68 | 19 | Shrub/Tree | ||||

| Senna occidentalis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 15 | 19.72 | 5 | 0.15 | 51 | ||||

| Senna rugosa (Don) | 0.00 | 0.47 | 30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 52 | Tree | ||||

| Stryphnodendron adstringens | 0.00 | 2.68 | 13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 31 | Tree | yes | |||

| Lamiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Hyptis virgata | 18.84 | 7 | 0.30 | 32 | 24.49 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 57 | ||||

| Hyptis lanceolata | 11.36 | 8 | 0.26 | 33 | 5.44 | 9 | 1.46 | 15 | 3.61 | 17 | Shrub | |

| Vitex moronensis | 1.17 | 14 | 0.00 | 10.83 | 5 | 28.20 | 3 | 11.18 | 8 | Tree | ||

| Lauraceae | ||||||||||||

| Senna occidentalis | 4.47 | 10 | 0.00 | 34.19 | 3 | 11.29 | 6 | 0.26 | 41 | |||

| Persea indica | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.50 | 1 | 17.22 | 4 | Tree | ||||

| Malpighiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Byrsonima crassifolia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.55 | 8 | 0.00 | 1.23 | 26 | Tree | ||||

| Byrsonima intermedia | 1.48 | 13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 46 | |||||

| Byrsonima verbascifolia | 1.48 | 13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 47 | Tree | no | |||

| Bysonima dealbata | 0.00 | 1.86 | 15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 32 | Shrub | ||||

| Malpighiaceae tetrapteres | 0.92 | 15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 53 | Shrub | ||||

| Peixotoa reticulata | 0.00 | 5.73 | 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.38 | 25 | |||||

| Tetrapterys microphylla | 0.00 | 0.57 | 28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 49 | Shrub | ||||

| Melastomataceae | ||||||||||||

| Miconia albicans | 0.00 | 0.25 | 34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 59 | |||||

| Miconia cabucu | 0.00 | 1.45 | 19 | 1.59 | 12 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 29 | Tree | |||

| Miconia elegans | 0.65 | 16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 55 | Tree | ||||

| Moraceae | ||||||||||||

| Brosimum gaudichaudii | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.17 | 17 | 0.46 | 35 | Tree | yes | |||

| Myrtaceae | ||||||||||||

| Myrcia eriocalyx | 0.00 | 1.67 | 16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 33 | Tree | ||||

| Myrcia hartwegiana | 0.00 | 1.30 | 20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 38 | Shrub | ||||

| Campomanesia xanthocarpa | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.85 | 14 | 0.50 | 34 | Shrub | ||||

| Myrtaceae sp. 12 | 26.78 | 4 | 0.92 | 23 | 0.57 | 16 | 0.00 | 3.76 | 16 | |||

| Primulaceae | ||||||||||||

| Myrsine guianensis | 30.08 | 3 | 55.42 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 19.45 | 1 | Tree | yes | ||

| Proteaceae | ||||||||||||

| Roupala montana | 25.35 | 5 | 7.27 | 8 | 0.00 | 2.59 | 13 | 6.02 | 11 | Tree | yes | |

| Rubiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Cordieira microphylla | 0.00 | 2.53 | 14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 28 | Shrub | ||||

| Genipa americana | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 21 | 0.35 | 39 | Tree | ||||

| Palicourea rigida | 0.00 | 0.58 | 27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 50 | Shrub | no | |||

| Rudgea viburnoides | 0.52 | 19 | 0.50 | 29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 45 | Tree | |||

| Tocoyena formosa | 0.00 | 1.51 | 17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 36 | Tree | yes | |||

| Sapindaceae | ||||||||||||

| Matayba marginata | 0.00 | 1.13 | 21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 40 | Shrub | ||||

| Solanaceae | ||||||||||||

| Solanum lycocarpum | 0.00 | 3.08 | 12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 30 | Shrub | yes | |||

| Verbenaceae | ||||||||||||

| Lippia L. | 0.00 | 0.77 | 24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 44 | Shrub | ||||

| Vochysiaceae | ||||||||||||

| Qualea parviflora | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.50 | 1 | 0.08 | 60 | |||||

| Qualea grandiflora | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.09 | 10 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 27 | Tree | yes | |||

| Salvertia convallariodora | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 15 | 19.72 | 5 | 17.65 | 3 | Tree | yes | ||

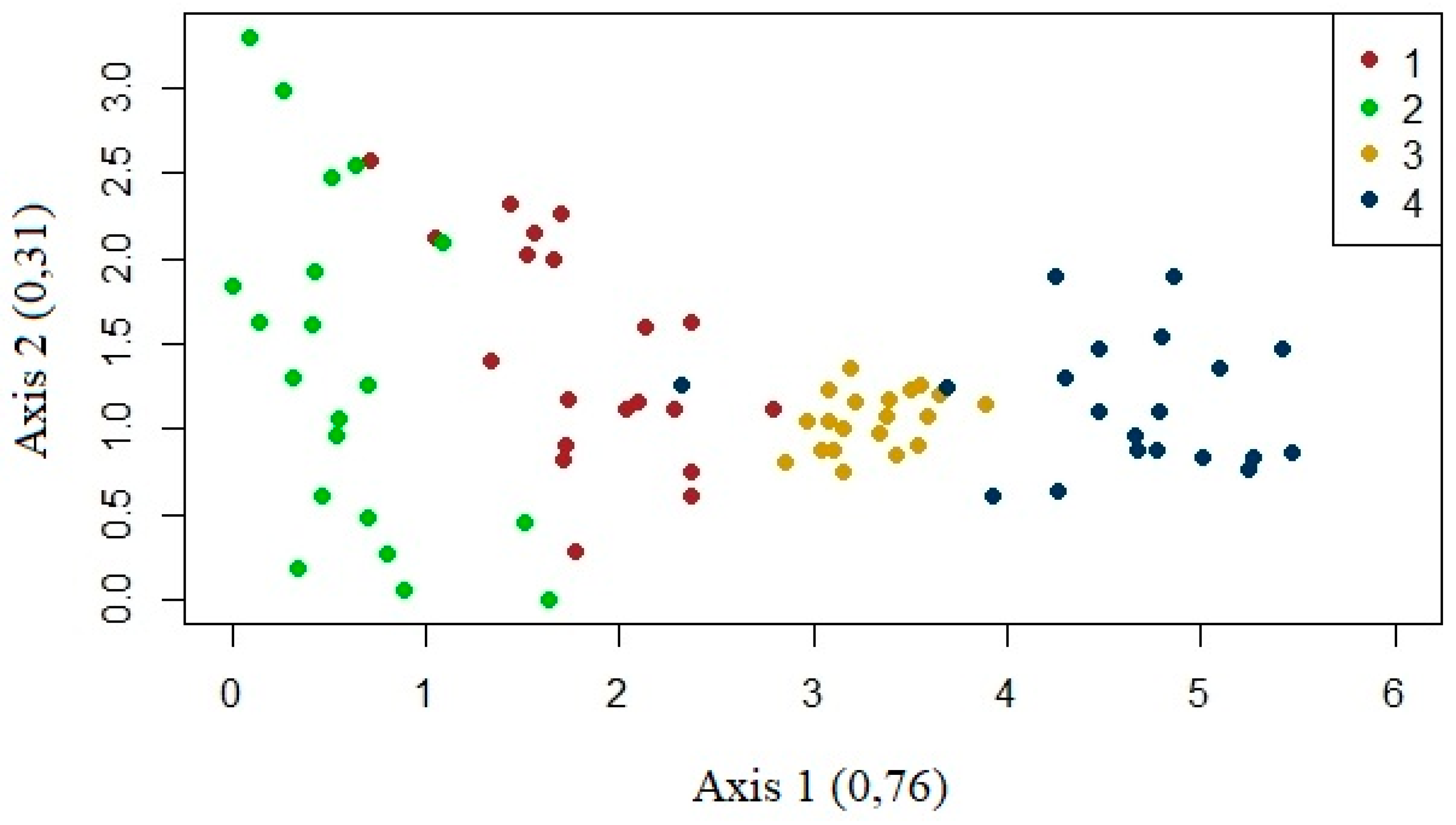

3.2. Landscape analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Alvarado, S.T.; Fornazaria, T.; Cóstolaa, A.; Morellat, L.P.C.; Silva, T.S.F. Drivers of fire occurrence in a mountainous Brazilian cerrado savanna: Tracking long-term fire regimes using remote sensing. Ecological Indicators 2017, 78, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvino-rayol, F.O.; Rayol, B.P. Efeito do fogo na vegetação espontânea em sistema agroflorestal, Pará, Brasil. Revista de Ciências Agroveterinárias 2020, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, C.J.F. The analysis of vegetation environment relationships by canonical correspondence analysis. Vegetation 1987, 69, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Fitosociologia: bases para el estudio de las comunidades vegetales, 3rd ed.; Aum. Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brower, J.E.; Zar, J.H.; Von Ende, C. Field & laboratory methods for general ecology; W.C. Brown Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.P.; Santos, L.C.S.; Rios, J.M.; Rodrigues, A.W.; Neto, O.C.D.; Prado-junior, J.; Vale, V.S. Estrutura e diversidade de trechos de Cerrado sensu stricto às margens de rodovias no estado de Minas Gerais. Ciência Florestal 2019, 29, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durigan, G.; Ratter, J.A. The need for a consistent fire policy for Cerrado conservation. Journal of Applied Ecology 2016, 53, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.S.; Sawakuchi, H.O.; Ferreira, M.E.; Ballester, M.V.R. Landscape changes in a neotropical forest savanna ecotone zone in central Brazil: The role of protected areas in the maintenance of native vegetation. Journal of Environmental Management 2017, 187, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, J.M.; Hoffman, W.A. Caught in a fire trap: Recurring fire creates stable size equilibria in woody resprouters. Ecology 2012, 93, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, D.W. Some considerations in the use of point quadrats for the analysis of vegetation. Australian Journal of scientific Research B. (In the Press), 1952.

- Hoffmann, W.A. Direct and indirect effects of fire on radial growth of cerrado savanna trees. Journal of Tropical Ecology 2002, 18, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libano, A.M.; Felfili, J.M. Mudanças temporais na composição florística e na diversidade de um cerrado sensu stricto do Brasil Central em um período de 18 anos (1985-2003). Acta Botanica Brasilica 2006, 20, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.F.; Vale, V.S.; Schiavini, I. Efeito de queimadas sobre a estrutura e composição da comunidade vegetal lenhosa do cerrado sentido restrito em Caldas Novas, GO. Árvore 2009, 33, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, S.D.; Colma, A. Metodologia para el estudio de la vegetación. Washington: The General Secretarial of The Organization of American States. (Série Biologia – Monografia, n. 22), 1982.

- Messias, C.G.; Ferreira, M.C. Análise da distribuição espacial das queimadas no parque nacional da serra da canastra (mg), entre 1984 e 2017. Caminhos de Geografia 2019, 20, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.G. Effects of fire protection on savanna structure in Central Brazil. Journal of Biogeography 2000, 27, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.D.; Pereira, J.A.A.; Santos, R.M.; Machado, E.L.M.; Marques, J.J. Diferenciação da vegetação arbórea de três setores de um remanescente florestal relacionada ao seu histórico de perturbações. Ciência Florestal 2016, 26, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.D.; Pereira, J.A.A.; Santos, R.M.; Aguiar-Campos, N.; Machado, E.L.M. Functional characterisation of an anthropised atlantic forest fragment. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 2018, 30, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S.C.; Overbeck, G.E. Plant functional types of woody species related to fire disturbance in forest–grassland ecotones. Plant Ecology 2007, 189, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.W. Estimating species richness: the second-order jackknife estimator reconsidered. Ecology 1991, 72, 1512–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.F.; Walter, B.M.T. As principais fitofisionomias do Bioma Cerrado. In.: Sano, S.M.; Almeida, S.P.; Ribeiro, J.F. (Eds.), Ecologia e flora. Brasília: Embrapa, 2008, pp. 152–212.

- Rios, M.N.S.; Souza-Silva, J.C. Grupos funcionais em áreas com histórico de queimadas em Cerrado sentido restrito no Distrito Federal. Brazilian Journal of Forestry Research 2017, 37, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, M.N.S.; Souza-Silva, J.C.; Malaquias, J.V. Mudanças pós-fogo na florística e estrutura da vegetação arbóreo-arbustiva de um cerrado sentido restrito em planaltina – DF. Ciência Florestal 2018, 28, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Gáscon, R.E.; Ferreira, C.C.M. Influência do enos e amo entre 2003-2014 no clima e regimes de fogo na Gran Sabana, Parque Nacional Canaima, Guiana Venezuelana. Revista Brasileira de Climatologia 2018, 22, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, N.V.; Machado, E.L.M.; Pereira, R.S.; Fernandes, G.W.; Gonzaga, A.P.D.; Mucida, D.P.; Silva, L.S. Structural analysis of a fragmented area in Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences 2018, 90, 3353–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.B.; Camargo, P.B.; Junior, R.C.O. Estoque e dinâmica de biomassa arbórea em floresta ombrófila densa na Flona Tapajós: Amazônia oriental. Ciência Florestal 2018, 28, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, I.B.; Fonseca, C.B.; Ferreira, M.C.; Sato, M.N. Experiências Internacionais de Manejo Integrado do Fogo em Áreas Protegidas – Recomendações para Implementação de Manejo Integrado de Fogo no Cerrado. Biodiversidade Brasileira 2016, 6, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Smit. IP.J.; Asner, G.P.; Govender, N.; Kennedy-Bowdoin, T.; Jacobson, J.; Knapp, D. Effects of fire on woody vegetation structure in African savanna. Ecological Applications 2010, 20, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, I.PJ.; Asner, G.P.; Govender, N.; Vaughn, N.R.; Wilgen, B.W. An examination of the potential efficacy of highintensity fires for reversing woody encroachment in savannas. Journal of Applied Ecology 2016, 53, 1623–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abundance | Diversity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Mean | F | p | Index | Area | Value | ||

| Individuals | 1 | 12.90 | 14 | 10.28 | <0.001 | Shannon (H') | 1 | 2.33 |

| 2 | 28.60 | 23 | 2 | 2.46 | ||||

| 3 | 22.00 | 234 | 3 | 2.00 | ||||

| 4 | 19.65 | 134 | 4 | 2.43 | ||||

| Families | 1 | 4.25 | 1234 | 1.32 | 0.27 | Pielou (J') | 1 | 0.81 |

| 2 | 5.10 | 2 | 0.70 | |||||

| 3 | 4.45 | 3 | 0.74 | |||||

| 4 | 5.05 | 4 | 0.84 | |||||

| Species | 1 | 4.40 | 1234 | 2.37 | 0.08 | 1st order Jackknife estimator | 1 | 53.10 |

| 2 | 6.05 | 2 | 108.90 | |||||

| 3 | 5.30 | 3 | 57.95 | |||||

| 4 | 5.65 | 4 | 44.45 | |||||

| 2nd order jackknife estimator | 1 | 66.74 | ||||||

| 2 | 139.00 | |||||||

| 3 | 70.88 | |||||||

| 4 | 50.09 | |||||||

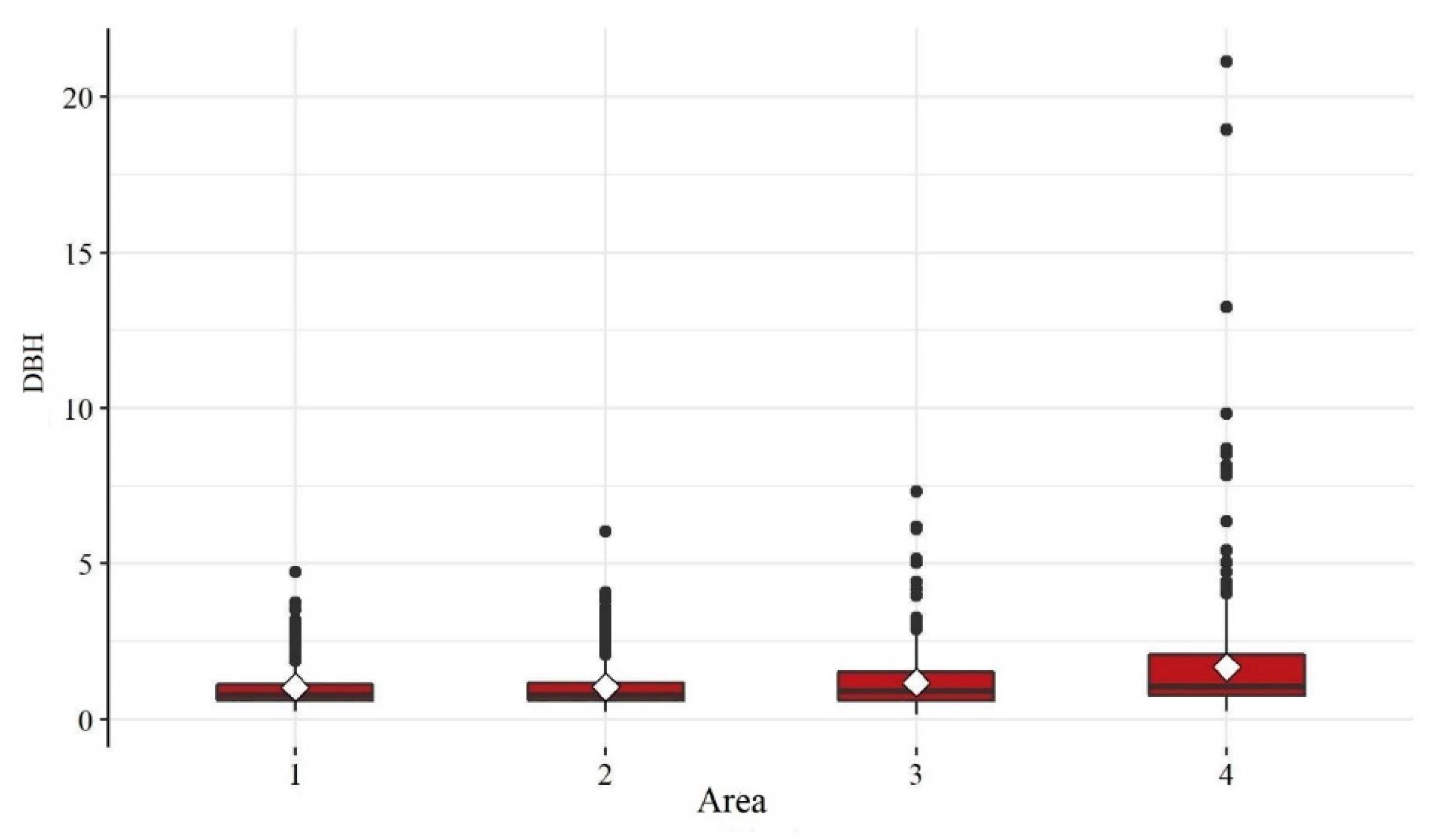

| Statistic | Area 1 | Area 2 | Area 3 | Area 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 1.67 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 1.95 |

| Minimum | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| 1st Quartile | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.76 |

| Median | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 1.05 |

| 3rd Quartile | 1.11 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 2.06 |

| Maximum | 4.74 | 6.04 | 7.32 | 21.13 |

| Area | Tempo | TA (ha) | PD | TE | ED | TCA | PR | CONNECT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-fire | 266 | 1.12 | 5.250 | 19.70 | 135 | 3.000 | 0 |

| 1 | Post-fire | 266 | 1.05 | 5.250 | 18.39 | 154 | 3.000 | 0 |

| 2 | Pre-fire | 447 | 1.34 | 10.560 | 23.61 | 239 | 3.000 | 16.66 |

| 2 | Post-fire | 447 | 2.17 | 17.010 | 36.98 | 189 | 3.000 | 0 |

| 3 | Pre-fire | 150 | 3.32 | 6.630 | 44.05 | 31 | 3.000 | 0 |

| 3 | Post-fire | 150 | 4.29 | 7.410 | 44.52 | 43 | 3.000 | 0 |

| 4 | Pre-fire | 369 | 2.16 | 6.900 | 18.68 | 206 | 3.000 | 0 |

| 4 | Post-fire | 269 | 1.51 | 7.470 | 22.69 | 1753 | 3.000 | 50.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).