1. Introduction

COVID-19 vaccinations were essential in Kuwait for controlling the spread of the virus and protecting public health. However, there have been concerns about vaccine hesitancy and misinformation in the country [

1,

2,

3], which may impact vaccination rates and the effectiveness of vaccination efforts for other types of vaccines in the future. This trend is concerning, as vaccines are essential for preventing the spread of infectious diseases and protecting public health [

4,

5]. Detecting and addressing opposing stances towards vaccination on social media are essential public health efforts. Public health officials need to have access to this information to target interventions and address misinformation. Also, they must present accurate, evidence-based information about vaccines to the public to combat vaccine hesitancy and protect the health of individuals and communities.

This research aims to label a large dataset of tweets written in the Kuwaiti dialect. The tweets will be classified pragmatically depending on their attitude towards vaccines to track negative views on social media. This research is an integral part of a more comprehensive attempt to understand the elements that cause vaccine hesitancy and to create practical approaches for addressing it. Furthermore, by analyzing social media data, we can better understand the methods of spreading misinformation and vaccine-related conspiracy theories and their consequences on public opinion. Ultimately, this knowledge can help public health officials to propose initiatives to secure the health of individuals and communities.

The main contribution of this research is creating the first dataset of tweets labeled regarding stance towards vaccines in the Kuwaiti dialect (42,764 labeled tweets). This dataset will be a valuable resource for researchers studying vaccine hesitancy and its impact on public health. Additionally, this research implements the first Kuwaiti dialect annotation system for vaccine stance detection (Q8VaxStance) by using weak supervised learning and applying prompt engineering to zero-shot models as labeling functions to programmatically annotate the dataset regarding stance towards vaccines in the Kuwaiti dialect. Finally, given the limited availability of linguistic resources for the Kuwaiti dialect, this research tries to fill in this gap in the field of natural language processing by providing a dataset to develop and evaluate machine learning models for stance detection in the Kuwaiti dialect.

The following are the research questions of our study:

How can we create a labeling system to annotate a large dataset of Kuwaiti dialect tweets for stance detection towards vaccines with or without help from subject matter experts (SMEs)?

What experimental setup produces the best performance for the proposed labeling system?

This paper is organized as follows: In the Background section, we review the relevant literature on vaccine hesitancy and stance detection towards the COVID-19 vaccine, natural language processing (NLP) research involving the Kuwaiti dialect, and dataset annotation approaches in NLP. Then, in the Methodology section, we describe the dataset collection and preparation process. Next, we explain the process of labeling the dataset manually, and then we describe the steps and architecture of the proposed labeling system Q8VaxStance. Next, in the Experiment Results and Discussion section, we present the performance evaluation results based on the Q8VaxStance labeling system experiments. Finally, in the Conclusion section, we summarize the study’s main findings and the proposed future work.

2. Background

2.1. Vaccine hesitancy and Stance detection using social Network analysis and Natural Language processing

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the overall stance towards vaccines, as it increased negative attitudes towards vaccines in Kuwait and around the globe [

1,

2,

3,

6]. This should raise a red flag and alert policymakers and governments to take action.

Many researchers have studied this topic; for example, the researchers of [

7] used multi-task aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA) and social features for stance detection in tweets based on deep learning models of BiGRU-BERT. It combines aspect-based sentiment information with features based on textual and contextual information that does not emerge directly from Twitter texts. Another contribution to this topic is found in [

8], where the researchers presented a dataset of Twitter posts with a strong anti-vaccine stance to be used in studying anti-vaccine misinformation on social media and to enable a better understanding of vaccine hesitancy. In [

9], the researchers collected and annotated 15,000 tweets as misinformation or general vaccine tweets. The paper’s best classification performance resulted from using the BERT language model, with a 0.98 F1 score on the test set. Also, the study presented in [

10] analyzed COVID-19 vaccine tweets and tested their association with vaccination rates in 192 countries worldwide. They compared COVID-19 vaccine tweets by country in terms of (1) the number of related tweets per million Twitter users, (2) the proportion of tweets mentioning adverse events (death, side effects, and blood clots), (3) the appearance of negative sentiments as compared to positive sentiments, and (4) the appearance of fear, sadness, or anger as compared to joy. Finally, in contrast to the above research papers, which focused on negative stances, the researchers in [

5] investigated and focused on the trend in positive attitudes towards vaccines across ten countries.

2.2. Natural language processing (NLP) of Kuwaiti dialect

There has been an increased interest in developing natural language processing (NLP) models for the Arabic language. Arabic is a widely spoken and written language with a significant presence in the online world. Researchers in the Arabic world started to focus on creating resources and language models for the Arabic language; examples of Arabic language models include AraBERT [

11], ARBERT, MARBET [

12], and CAMeLBERT [

13], which focus on Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). In addition, some of them cover Arabic dialects for specific countries.

We found that there is a gap in the field of natural language processing for the Kuwaiti dialect as there is a limited availability of linguistic resources for this dialect, with only a few published research papers in the field of NLP focusing on it [

14,

15,

16,

17].

In [

14], the authors used a traditional machine learning approach by applying decision tree and SVM algorithms to classify opinions expressed in microblogging posts in the Kuwaiti dialect. They used a dataset of Kuwaiti Twitter posts annotated manually by three Kuwaiti dialect native speakers, enabling the researchers to achieve an average value of precision and recall of 76% and 61%, respectively, with the SVM algorithm.

Another research study on the Kuwaiti dialect was conducted by the authors of [

15]; in this paper, the researchers presented an approach to analyze the content of tweets by merging the strategies of text mining with the spatial information in order to assess the topics of interest to provide: 1—a deeper understanding of the topics people think about, 2—when they think about them, and 3—where they tweet about them. The results showed that the four most popular topics of interest in Kuwait are religion, emotion, education, and policy, and that on Fridays people post more about religion and tweet more often on weekends about emotional expressions. Moreover, people post more about policy and education on weekdays rather than on weekends.

The most recently published research papers studying the Kuwaiti dialect were [

16] and [

17]; in [

16] we proposed a weak supervised approach to construct a large labeled corpus for sentiment analysis of tweets written in the Kuwaiti dialect. The proposed automated labeling system achieved a high level of annotation agreement between the automated labeling system and human-annotated labels, being 93% for the pairwise percent agreement and 0.87 for Cohen’s kappa coefficient. Furthermore, we evaluated the dataset using multiple traditional machine learning classifiers and advanced deep learning language models to test its performance. The reported best accuracy was 89% when the resulting labeled dataset was trained with the ARBERT model. The labeling system architecture of Q8VaxStance is an extended version of our proposed labeling system in [

16], but it has the following differences: First, in Q8VaxStance we experimented with different types of labeling functions, and used prompt engineering, while in [

16]we used one fixed prompt and the labeling functions all used zero-shot learning. Next, the dataset used in [

16] is different regarding time frame, type of extracted event, and size, plus the main task was sentiment classification. In contrast, in this research paper, our main NLP task is stance detection.

Contrary to the previous papers that collected and used a dataset from Twitter in their experiments, the researchers in [

17] collected and analyzed a corpus of WhatsApp group chats involving mixed-gender Kuwaiti participants. This pilot study aimed to obtain insights into features to be used later for developing a gender classification system for the Kuwaiti dialect. The study’s results showed no significant differences between men and women in the number of turns, length of turns, and the number of emojis. However, the study showed that men and women differ in their use of lengthened words and the emojis they use [

17].

Based on the above, there is an opportunity for researchers in the field of NLP to fill in the Kuwaiti dialect gap since it is still underrepresented and not widely covered in this academic field.

2.3. Dataset Labeling Approaches

Data labeling is a challenging task for any NLP project; with the advances in deep learning and transfer learning algorithms, there is an increased need to label large-size datasets. On the other hand, labeling large datasets is a time-consuming task, and the subject matter experts (SMEs) do not have time to label these datasets as they already have their own main tasks to focus on. Also, in the case of crowdsourcing, the labels obtained from crowdsourcing are often not accurate [

18] plus the task will be very costly. Lastly, privacy may be an issue for some projects; as a result, the dataset labeling task cannot be outsourced or given to SMEs.

Many academic researchers have proposed solutions to label more data with or without the limited help of human annotators. The following are some of the approaches that can be used to annotate datasets for machine learning with limited to no help from annotators:

The first approach is using

active learning systems, which is based on [

19] and is achieved by making queries in the form of unlabeled instances to be labeled by a human annotator. In this way, the active learning system aims to achieve high accuracy using as few labeled instances as possible, minimizing the cost of obtaining labeled data.

The second approach is

semi-supervised learning and is based on [

20]; the goal of this approach is to use a small labeled training set to label a much larger unlabeled dataset using unsupervised algorithms.

Weak supervised learning is a type of semi-supervised learning approach that uses a collection of machine learning techniques in which models are trained using sources of information that are easier to provide than hand-labeled data, and can be used where this information is incomplete, inexact, or otherwise less accurate. The noisy, weak labels are combined using a generative model that is trained based on the accuracies of labeling functions; the accuracies are derived from the agreement and disagreement of the labeling functions and used to form the training data [

21,

22].

The

Snorkel framework is a weak supervised learning framework available as open source. Researchers at the Stanford AI Lab proposed this project, and it started in 2015; it is the oldest and most stable among the available weak supervised learning software frameworks. The following describes the steps of the Snorkel system [

23] :

SMEs write labeling functions (LFs) that express weak supervision sources like distant supervision, patterns, and heuristics.

Snorkel applies the LFs on unlabeled data and learns a generative model to combine the LFs’ outputs into probabilistic labels.

Snorkel uses these labels to train a discriminative classification model, such as a deep neural network.

In a paper that utilized Snorkel [

23], the weak supervised learning performance was tested in several ways. First, the authors compared productivity when teaching SMEs to use Snorkel versus spending the equivalent time just hand-labeling data. The result was that when they used the Snorkel framework, they were able to build models not only 2.8x faster, but also with a 45.5% better predictive performance on average.

Another paper from MIT researchers on weak supervised learning supported the results of the previous paper [

24]. In this paper, they found that a combination of a few "strong" labels and a larger "weak" label dataset resulted in a model that learned well and trained at a faster rate.

The second performance evaluation in [

23] was based on projects in collaboration with Stanford, the U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; in this evaluation, they found that Snorkel leads to an average 132% improvement over baseline techniques.

The third dataset annotation approach is

transfer learning, which aims to extract the knowledge from one or more source tasks (large pre-trained models on a different dataset) and applies the knowledge to a target task (to label the dataset) [

25].

Zero-shot (ZS) learning is based on transfer learning; it is suitable when no labeled data is provided [

26]. The ZS model can predict the class of the unlabeled sample using natural language inference (NLI), even if the model was not trained on those classes. ZS models leverage the semantic similarity between labels and the text context [

27]. In tnatural language inference (NLI) learning, the text is treated as the premise. Next, the hypothesis and expected labels are used to set the ZS model, where the hypothesis/prompt usually uses the following format: "this example is about {label}". When we run the ZS model with the values of the labels, premise, and hypothesis, it returns the entailment score or a confidence level that tells if the premise is related to that label or not.

To use zero-shot (ZS) learning with the Arabic language or its variant dialects, the ZS model should support Arabic or multiple languages. According to [

28], for languages other than English, the XLM-RoBERTA (XLM-R) model is a good candidate to perform ZS classification. It was trained on one hundred languages, including Arabic and many other low-resource languages. The authors of [

28] also found that applying the XLM-R model to the cross-lingual natural language inference (XNLI) task significantly outperforms multilingual BERT (mBERT) in accuracy by an average of +13.8%. It also performs well for low-resource languages, showing an improvement of 11.8% in XNLI accuracy for Swahili and 9.2% for Urdu over the previous XLM model. Another choice is using multilingual mDeBERTa, a state-of-the-art (SOTA) model, in XNLI tasks. It is the best-performing multilingual base-sized transformer model; it achieved a 79.8% ZS cross-lingual accuracy for XNLI, and a 3.6% improvement over XLM-R Base [

29].

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Collection

To collect the dataset containing tweets related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Kuwait, we implemented the following steps:

3.2. Dataset Preparation

To prepare our dataset and make sure it only contained tweets from Kuwait, we filtered out tweets that did not have one of the following keywords in the user_location field: Koweït, Q8, kw, kwt, kuwait, الكويت , كويتيه , كويتي , وطن النهار, and KU. We also programmatically removed unrelated tweets by excluding all posts not written in the Arabic language or containing keywords related to Arabic spam posts. Next, we cleaned the text of the tweets by removing digits, special characters, URLs, emojis, mentions, tashkīl (diacritics), and punctuation. We did not remove the hashtags since, based on our observations of the dataset, hashtags are heavily used to express the stance towards vaccination; instead, we only removed the hash # and underscore _ characters between the hashtag keywords to be able to process the hashtag as regular text. After the dataset preparation and cleansing, the total number of extracted unlabeled tweets was 42815

1.

3.3. Dataset Labeling

To validate our proposed labeling system, we needed a manually labeled dataset. Two of the Kuwaiti native speakers from the research team hand-labeled the dataset using an online tool called

NLP Annotation Lab2. The annotators were able to label 878 tweets out of 2000 extracted tweets that were different from the original dataset and classified them as either anti-vaccine or pro-vaccine; finally, the two annotators manually checked the labeled dataset for disagreements, and then they revised the labels and approved the final labels. The distribution of the manually labeled tweets to be used to validate the Q8VaxStance labeling system was 350 anti-vaccine tweets and 528 pro-vaccine tweets.

3.4. Q8VaxStance Labeling system

Our first research question aimed to investigate whether a weak supervised learning approach combined with the prompt engineering of zero-shot models could label a large dataset of tweets for stance detection towards vaccines with limited help from SMEs. To obtain an answer to our first research question, we performed the following steps:

We selected the weak supervised learning framework to use in our experiments. To do so, we examined several Python packages and frameworks that support weak supervised learning for natural language processing. We decided to use the Snorkel open-sourced software framework [

21] based on the good results we were able to establish in [

16] for the sentiment classification of the Kuwaiti dialect.

We set up 52 experiments, as described in

Table 1, and for each experiment, we created the labeling functions that determine the stance towards vaccines.

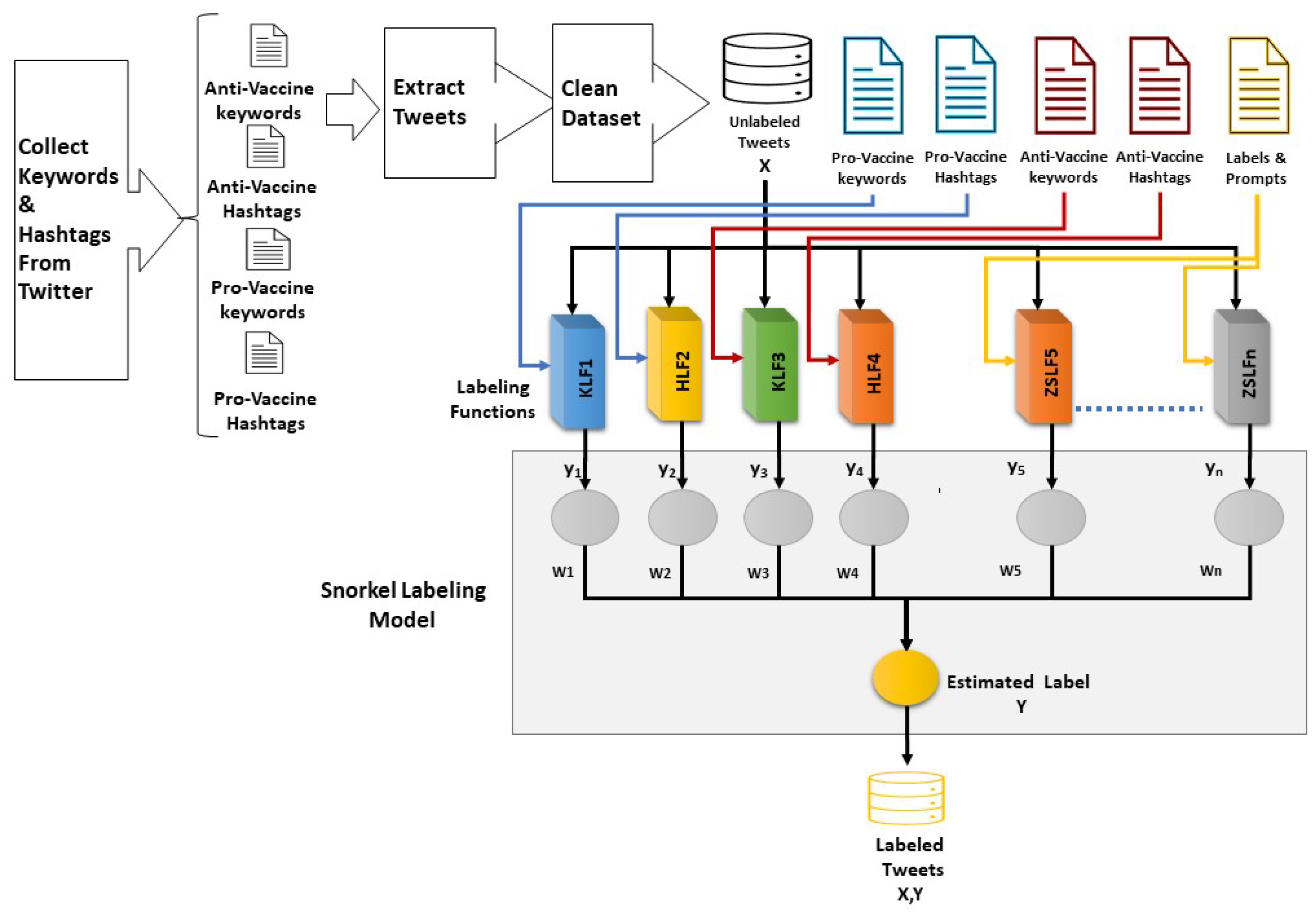

Figure 1 illustrates the general Q8VaxStance labeling system architecture used in the KHZSLF experiment setup; the system architecture for the KHLF and ZSLF experiments is similar, but with some labeling functions were excluded depending on the experiment setup.

We applied the labeling functions on 42815 unlabeled tweets and trained the model using the Snorkel package to predict the dataset labels. As a base experiment, we created labeling functions to label the dataset based on the presence of specific pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine keywords and hashtags in the tweet texts. In this experiment, we used the same keywords and hashtags that were used before to obtain the dataset from Twitter.

-

We conducted several experiments to compare the performance of using only zero-shot (ZS)-learning-based labeling functions versus that when combining keyword-based labeling functions with zero-shot-learning-based labeling functions. The following are the zero-shot pre-trained models used in the ZS labeling functions:

- (a)

joeddav/xlm-roberta-large-xnli

3.

- (b)

MoritzLaurer/mDeBERTa-v3-base-mnli-xnli

4 [

31].

- (c)

vicgalle/xlm-roberta-large-xnli-anli

5.

We applied prompt engineering to check the effect of using different prompts and labels on the labeling system performance, and then determined the best labels and prompt combinations that produce the best performance when using the zero-shot-learning-based labeling function. To apply prompt engineering, we varied the text of labels and prompts; we also tested different combinations consisting of English labels and prompts, Arabic labels and prompts, and mixed language labels and prompts to check the effect of the language used in labels and prompts on system performance.

Table 2 and

Table 3 contain a list of the labels and prompts used in our experiments.

Our second research question aimed to evaluate the performance of the Q8VaxStance system in labeling a large dataset for stance detection towards vaccines. To be able to address this question, we tested the human-labeled dataset using the model we trained using the Snorkel package and the 42815 unlabeled dataset; then, we compared values of the accuracy, macro-F1, and the total number of generated labels for each experiment. The details of the experimental results are presented in the next section. Finally, we used ANOVA and Tukey HSD tests to compare the experiments to determine if they are statistically significant, and to discover the main factors affecting the experiments’ performance and the labeling functions’ ability to generate more labels.

4. Experiment Results and Discussion

To execute our experiments, we followed the steps presented in

Figure 1. We started with tweet extraction using the Twitter academic API; after pre-processing and cleansing, the total number of extracted unlabeled tweets was 42815. Then, we applied Snorkel labeling functions on the tweets based on each experiment setup, as shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. Next, we used the Snorkel framework to train the labeling model to predict the labels based on the weights of labeling functions, and finally, we applied the trained model on the human-annotated dataset to be able to carry out the performance evaluation.

The results of the individual groups of experiments are illustrated in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7; comparing the results, we observed that the experiments using mixed keywords and zero-shot models for the labeling functions gave an average accuracy value of 0.82 and an average Macro-F1 ranging from 0.81 to 0.82. The results show that the best accuracy and Macro-F1 values were achieved in the experiments KHZSLF-EE4 and KHZSLF-EA1 with nearly the same accuracy and Macro-F1 values of 0.83 and 0.83, respectively. Moreover, the best accuracy for the experiments in the groups using Arabic labels and templates was in the experiments KHZSLF-AA8 and KHZSLF-AA9, with accuracy and Macro-F1 values of 0.83 and 0.82, respectively.

Next, the results were analyzed to detect which experiments generated a more balanced distribution of the generated dataset labels. The results show that, on average, the experiment groups KHZSLF-AA, ZSLF-AA, and KHZSLF-EA created nearly balanced datasets. In contrast, the experiments KHZSLF-EE, ZSLF-EE, and ZSLF-EA created imbalanced datasets. The detailed results for each experiment group are illustrated in

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11.

Next, to detect the main factors affecting the performance of the experiments and the generated labels, we applied ANOVA and pairwise Tukey HSD post hoc tests to identify the statistical significance of the experiments.

Table 12 illustrates the ANOVA test P-value results, while

Table 13 and

Table 14 show the adjusted P-value results for each experiment group based on changing the type of labeling function and changing the language of labels and prompts used in the zero-shot models. The following is a description of each experiment group:

As presented in

Table 12, the ANOVA test results show that at a significance level of 0.05 when using keyword detection vs. zero-shot models as labeling functions and changing the language of labels and templates used in zero-shot models is statistically significant in regard to the accuracy, macro-F1, and the total number of labels predicted by the model.

Furthermore, the Tukey HSD post hoc test results in

Table 13 show that when using zero-shot models and keyword detection as labeling functions (KHZSLF), the experiments had a significantly better performance than when using only the keyword detection labeling functions (KHLF) or using only the zero-shot model labeling functions (ZSLF) for all three evaluation metrics (accuracy, macro-averaged F1 score, and the total number of labels). Also, the results shows that there is no significant statistical difference between the total generated labels when using keyword and zero-shot models (KHZSLF) compared to when using only zero-shot models as labeling functions (ZSLF).

Table 14 illustrates the results when changing the language used in labels and prompts in zero-shot models; the results shows that the total number of generated labels is affected when using Arabic in both labels and prompts (AA) or mixed Arabic and English labels and prompts (AE), and it is statistically significant and generates more labels than when using the English language in both labels and prompts (EE). The results also indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between the means of the three evaluation metrics (accuracy, macro-averaged F1 score, and the total number of labels) when using zero-shot model labeling functions with any language (AA, AE, or EE) compared to not using zero-shot models (NN). We also concluded that when using mixed zero-shot models with mixed language labels and prompts (AAAEEE), the experiments are not statistically significant compared to using zero-shot models.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we attempted to fill in the gap in the field of NLP by creating Kuwaiti dialect language resources, as currently, the Kuwaiti dialect is still underrepresented in the available Arabic language models; these language resources are critical for developing high-performance approaches and systems for different NLP problems. To overcome the data annotation challenges, we proposed an automated system to programmatically label a tweet dataset to detect the stance towards vaccines in the Kuwaiti dialect (Q8VaxStance). The proposed system is based on an approach combining the benefits of weak supervised learning and zero-shot learning. This research is an essential part of a more comprehensive attempt to understand the elements that cause vaccine hesitancy in Kuwait and to create practical approaches for addressing it. The labeled dataset is considered the first Kuwaiti dialect dataset for vaccine stance detection.

The results of the experiments show that, when using both zero-shot models and keyword detection as labeling functions (KHZSLF), the experiments have a significantly better performance than when either using only the keyword detection labeling functions ((KHLF)) or using only the zero-shot models labeling functions (ZSLF) for all three evaluation metrics (accuracy, macro-averaged F1 score, and the total number of generated labels). Also, when changing the language of labels and prompts used in zero-shot models, the results show that the mean total number of generated labels using Arabic in both labels and prompts (AA) or mixed Arabic English labels (AE) and prompts is statistically significant compared to when using English in both labels and prompts (EE).

For future research work, we plan to use this generated dataset to fine-tune and compare different available Arabic BERT-based language models and large multilingual models, and create a trained model for Kuwaiti dialect stance detection. Finally, we plan to use graph neural network algorithms to predict vaccine stances and compare the findings with the results of this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and H.D; methodology, H.A.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A; formal analysis, H.A; investigation, H.A.; data curation, S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing: H.A., S.D., and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alibrahim, J.; Awad, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the public in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ayyadhi, N.; Ramadan, M.M.; Al-Tayar, E.; Al-Mathkouri, R.; Al-Awadhi, S. Determinants of hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines in State of Kuwait: an exploratory internet-based survey. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2021, 4967–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.A.; Failla, G.; Puleo, V.; Melnyk, A.; Lontano, A.; Ricciardi, W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review of the literature. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyling, T.; Rossouw, S. Positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-country analysis. PloS one 2022, 17, e0264994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAwadhi, E.; Zein, D.; Mallallah, F.; Bin Haider, N.; Hossain, A. Monitoring COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Kuwait during the pandemic: results from a national serial study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2021, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, C.B.P.; Purwitasari, D.; Raharjo, A.B. Stance Detection on Tweets with Multi-task Aspect-based Sentiment: A Case Study of COVID-19 Vaccination. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering and Systems 2022, 515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Muric, G.; Wu, Y.; Ferrara, E. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy on Social Media: Building a Public Twitter Data Set of Antivaccine Content, Vaccine Misinformation, and Conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2021, 7, e30642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayawi, K.; Shahriar, S.; Serhani, M.; Taleb, I.; Mathew, S. ANTi-Vax: a novel Twitter dataset for COVID-19 vaccine misinformation detection. Public Health 2022, 203, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Zain, A.; Chen, Y.; Kim, S.H. Adverse Mentions, Negative Sentiment, and Emotions in COVID-19 Vaccine Tweets and Their Association with Vaccination Uptake: Global Comparison of 192 Countries. Vaccines 2022, 10, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubtahij, H.E.; Abdelali, H.; Tazi, E.B. AraBERT transformer model for Arabic comments and reviews analysis. IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence (IJ-AI) 2022, 11, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mageed, M.; Elmadany, A.; Nagoudi, E.M.B. ARBERT & MARBERT: Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Arabic. Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers) 2021, 7088–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, O.; Zalmout, N.; Khalifa, S.; Taji, D.; Oudah, M.; Alhafni, B.; Inoue, G.; Eryani, F.; Erdmann, A.; Habash, N. CAMeL tools: An open source python toolkit for Arabic natural language processing. Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference 2020, 7022–7032. [Google Scholar]

- Salamah, J.B.; Elkhlifi, A. Microblogging opinion mining approach for kuwaiti dialect. The International Conference on Computing Technology and Information Management (ICCTIM). Citeseer 2014, 388. [Google Scholar]

- Almatar, M.G.; Alazmi, H.S.; Li, L.; Fox, E.A. Applying GIS and Text Mining Methods to Twitter Data to Explore the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Topics of Interest in Kuwait. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.; Al-Ostad, H.; Omar, H. A Weak Supervised Transfer Learning Approach for Sentiment Analysis to the Kuwaiti Dialect. Proceedings of the The Seventh Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop (WANLP). Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Aldihan, H.; Gaizauskas, R.; Fitzmaurice, S. A Pilot Study on the Collection and Computational Analysis of Linguistic Differences Amongst Men and Women in a Kuwaiti Arabic WhatsApp Dataset. Proceedings of the The Seventh Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop (WANLP); Association for Computational Linguistics: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Hybrid), 2022; pp. 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, V.S.; Zhang, J. Machine Learning with Crowdsourcing: A Brief Summary of the Past Research and Future Directions. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 9837–9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, B. Active learning literature survey. University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- Engelen, J.E.v.; Hoos, H.H. A survey on semi-supervised learning. Machine Learning 2020, 109, 373–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, A.; De Sa, C.; Wu, H.; Davison, D.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y. Language Models in the Loop: Incorporating Prompting into Weak Supervision. Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2017, pp. 1776–1787.

- Tok, W.; Bahree, A.; Filipi, S. Practical Weak Supervision: Doing More with Less Data; O’Reilly Media, Incorporated, 2021.

- Ratner, A.; Bach, S.H.; Ehrenberg, H.; Fries, J.; Wu, S.; Ré, C. Snorkel: rapid training data creation with weak supervision. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 2017, 11, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Jegelka, S.; Sra, S. Strength from Weakness: Fast Learning Using Weak Supervision. Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning; III, H.D.; Singh, A., Eds. PMLR, 2020, Vol. 119, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 8127–8136.

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunstall, L.; von Werra, L.; Wolf, T. Natural language processing with transformers; " O’Reilly Media, Inc.", 2022.

- Yildirim, S.; Asgari-Chenaghlu, M. Mastering Transformers: Build state-of-the-art models from scratch with advanced natural language processing techniques; Packt Publishing, 2021.

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Grave, E.; Ott, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2020; pp. 8440–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. DeBERTaV3: Improving DeBERTa using ELECTRA-Style Pre-Training with Gradient-Disentangled Embedding Sharing. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Mai, P. Communalytic: A Research Tool For Studying Online Communities and Online Discourse, 2022.

- Laurer, M.; van Atteveldt, W.; Casas, A.; Welbers, K. Less Annotating, More Classifying–Addressing the Data Scarcity Issue of Supervised Machine Learning with Deep Transfer Learning and BERT-NLI 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).