Submitted:

04 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

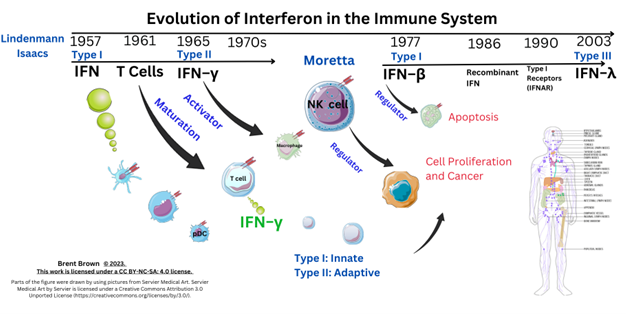

Introduction

Methodology

Background

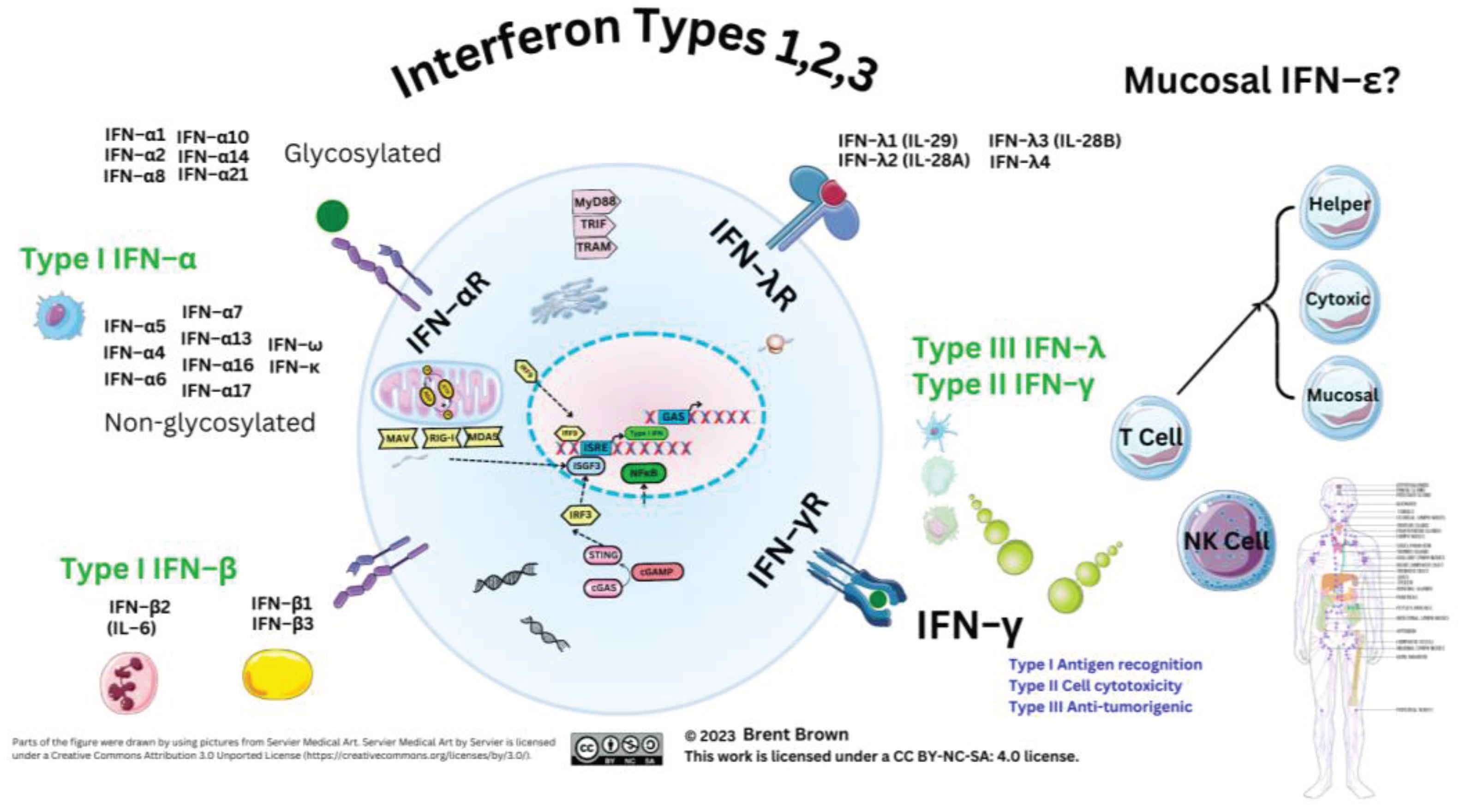

Interferon Types

Overview to Interferon Cellular Types

The Three Type of Interferon Roles in the Immune System

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval Statement and/or Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Trial registration details

Conflict or Competing Interest

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Disclaimer

References

- Brown, B. Innate and Adaptive Immunity during SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Biomolecular Cellular Markers and Mechanisms. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B. Immunopathogenesis of Orthopoxviridae: Insights into Immunology from Smallpox to Monkeypox (Mpox). ( 2023. [CrossRef]

- Brown, B. Filoviridae: Insights into Immune Responses to Ebolavirus. ( 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Lyu, S.; Li, P. Interferon-α2b enhances survival and modulates transcriptional profiles and the immune response in melanoma patients treated with dendritic cell vaccines. BioMedicine 2020, 125, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesev, E.V.; LeDesma, R.A.; Ploss, A. Decoding type I and III interferon signalling during viral infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högner, K.; Wolff, T.; Pleschka, S.; Plog, S.; Gruber, A.D.; Kalinke, U.; Walmrath, H.-D.; Bodner, J.; Gattenlöhner, S.; Lewe-Schlosser, P.; et al. Macrophage-expressed IFN-β Contributes to Apoptotic Alveolar Epithelial Cell Injury in Severe Influenza Virus Pneumonia. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizis, B. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells: Development, Regulation, and Function. Immunity 2019, 50, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, T.R.; Prokunina-Olsson, L.; Donnelly, R.P. IFN-λ4: The Paradoxical New Member of the Interferon Lambda Family. J. Interferon. Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.E.; Jennings, J.; Liu, Q.; Lee, J.; Ma, W.; Blecha, F.; Miller, L.C.; Sang, Y. Cross-Species Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Molecular and Functional Diversity of the Unconventional Interferon-ω Subtype. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittling, M.C.; Cahalan, S.R.; Levenson, E.A.; Rabin, R.L. Shared and Unique Features of Human Interferon-Beta and Interferon-Alpha Subtypes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P. et al. Contraction of the type I IFN locus and unusual constitutive expression of IFN-α in bats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 2696–2701 (2016).

- George, J.; Mattapallil, J.J. Interferon-α Subtypes As an Adjunct Therapeutic Approach for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Functional Cure. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, F.; Pellegrini, S.; Uzé, G. IFNA2: The prototypic human alpha interferon. Gene 2015, 567, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X. IgG N-glycans. 2021, 105, 1–47. [CrossRef]

- Giron, L.B.; Colomb, F.; Papasavvas, E.; Azzoni, L.; Yin, X.; Fair, M.; Anzurez, A.; Damra, M.; Mounzer, K.; Kostman, J.R.; et al. Interferon-α alters host glycosylation machinery during treated HIV infection. EBioMedicine 2020, 59, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katla, S.; Yoganand, K.; Hingane, S.; Kumar, C.R.; Anand, B.; Sivaprakasam, S. Novel glycosylated human interferon alpha 2b expressed in glycoengineered Pichia pastoris and its biological activity: N-linked glycoengineering approach. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2019, 128, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How, J.; Hobbs, G. Use of Interferon Alfa in the Treatment of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Perspectives and Review of the Literature. Cancers 2020, 12, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbalaei, M.; Rezaee, S.A.; Farsiani, H. Pichia pastoris: A highly successful expression system for optimal synthesis of heterologous proteins. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 5867–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.-H.; Hong, S.-H.; Seo, N.; Kim, T.-S.; An, H.J.; Lee, P.; Shin, E.-C.; Kim, H.M. Structure-based glycoengineering of interferon lambda 4 enhances its productivity and anti-viral potency. Cytokine 2020, 125, 154833–154833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-F.; Gong, M.-J.; Zhao, F.-R.; Shao, J.-J.; Xie, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Chang, H.-Y. Type I Interferons: Distinct Biological Activities and Current Applications for Viral Infection. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 51, 2377–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, N.; de Lesegno, C.V.; Lamaze, C.; Blouin, C.M. Interferon Receptor Trafficking and Signaling: Journey to the Cross Roads. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, M.; Lochte, S.; Piehler, J.; Schreiber, G. IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 play distinct roles in initiating type I interferon–induced JAK-STAT signaling and activating STATs. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabe4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, T.B.; Kalie, E.; Crisafulli-Cabatu, S.; Abramovich, R.; DiGioia, G.; Moolchan, K.; Pestka, S.; Schreiber, G. Binding and activity of all human alpha interferon subtypes. Cytokine 2011, 56, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-M. & Shin, E.-C. Type I and III interferon responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Exp Mol Med 53, 750–760 (2021).

- Ali, S.; Mann-Nüttel, R.; Schulze, A.; Richter, L.; Alferink, J.; Scheu, S. Sources of Type I Interferons in Infectious Immunity: Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Not Always in the Driver's Seat. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaSalle, T.J.; Gonye, A.L.; Freeman, S.S.; Kaplonek, P.; Gushterova, I.; Kays, K.R.; Manakongtreecheep, K.; Tantivit, J.; Rojas-Lopez, M.; Russo, B.C.; et al. Longitudinal characterization of circulating neutrophils uncovers phenotypes associated with severity in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Weerd, N.A.; Samarajiwa, S.A.; Hertzog, P.J. Type I Interferon Receptors: Biochemistry and Biological Functions. Perspect. Surg. 2007, 282, 20053–20057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.-Y. et al. Loss of orf3b in the circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains. Emerg Microbes Infect 9, 2685–2696 (2020).

- Overholt, K.J.; Krog, J.R.; Zanoni, I.; Bryson, B.D. Dissecting the common and compartment-specific features of COVID-19 severity in the lung and periphery with single-cell resolution. iScience 2021, 24, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sposito, B.; Broggi, A.; Pandolfi, L.; Crotta, S.; Clementi, N.; Ferrarese, R.; Sisti, S.; Criscuolo, E.; Spreafico, R.; Long, J.M.; et al. The interferon landscape along the respiratory tract impacts the severity of COVID-19. Cell 2021, 184, 4953–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantlo, E. , Bukreyeva, N., Maruyama, J., Paessler, S. & Huang, C. Antiviral activities of type I interferons to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antiviral Res 179, 104811 (2020).

- Brzoska, J. , von Eick, H. & Hündgen, M. Interferons in COVID-19: missed opportunities to prove efficacy in clinical phase III trials? Front Med (Lausanne) 10, (2023).

- McNab, F.; Mayer-Barber, K.; Sher, A.; Wack, A.; O'Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, R.F.V.; Hunger, A.; Mendonça, S.A.; Barbuto, J.A.M.; Strauss, B.E. Immunomodulatory and antitumor effects of type I interferons and their application in cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 71249–71284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belardelli, F.; Ferrantini, M.; Proietti, E.; Kirkwood, J.M. Interferon-alpha in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002, 13, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syedbasha, M.; Egli, A. Interferon Lambda: Modulating Immunity in Infectious Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egli, A.; Santer, D.M.; O'Shea, D.; Barakat, K.; Syedbasha, M.; Vollmer, M.; Baluch, A.; Bhat, R.; Groenendyk, J.; Joyce, M.A.; et al. IL-28B is a Key Regulator of B- and T-Cell Vaccine Responses against Influenza. PLOS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, N.M.; Mothes, W. Cytonemes and tunneling nanotubules in cell–cell communication and viral pathogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, A.; François, C.; Descamps, V.; Fournier, C.; Wychowski, C.; Dubuisson, J.; Castelain, S.; Duverlie, G. Enhanced anti-HCV activity of interferon alpha 17 subtype. Virol. J. 2009, 6, 70–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagnolari, C.; Trombetti, S.; Selvaggi, C.; Carbone, T.; Monteleone, K.; Spano, L.; Di Marco, P.; Pierangeli, A.; Maggi, F.; Riva, E.; et al. In Vitro Sensitivity of Human Metapneumovirus to Type I Interferons. Viral Immunol. 2011, 24, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markušić, M.; Šantak, M.; Košutić-Gulija, T.; Jergović, M.; Jug, R.; Forčić, D. Induction of IFN-αSubtypes and Their Antiviral Activity in Mumps Virus Infection. Viral Immunol. 2014, 27, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Cui, C.; Tu, L.; Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L. Diversity of locally produced IFN-α subtypes in human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells and mouse lung tissues during influenza virus infection. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 6351–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safadi, D.; Lebeau, G.; Lagrave, A.; Mélade, J.; Grondin, L.; Rosanaly, S.; Begue, F.; Hoareau, M.; Veeren, B.; Roche, M.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Are Conveyors of the NS1 Toxin during Dengue Virus and Zika Virus Infection. Viruses 2023, 15, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Gravier, T.; Fricke, I.; Al-Sheboul, S.A.; Carp, T.-N.; Leow, C.Y.; Imarogbe, C.; Arabpour, J. Immunopathogenesis of Nipah Virus Infection and Associated Immune Responses. Immuno 2023, 3, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinykh, P.A.; Lubaki, N.M.; Widen, S.G.; Renn, L.A.; Theisen, T.C.; Rabin, R.L.; Wood, T.G.; Bukreyev, A. Different Temporal Effects of Ebola Virus VP35 and VP24 Proteins on Global Gene Expression in Human Dendritic Cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 7567–7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, M.; Reid, S.P.; Leung, L.W.; Basler, C.F.; Volchkov, V.E. Ebolavirus VP24 Binding to Karyopherins Is Required for Inhibition of Interferon Signaling. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, L.W.; Park, M.; Martinez, O.; Valmas, C.; López, C.B.; Basler, C.F. Ebolavirus VP35 suppresses IFN production from conventional but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M.; Halfmann, P.J.; Hill-Batorski, L.; Ozawa, M.; Lopes, T.J.S.; Neumann, G.; Schoggins, J.W.; Rice, C.M.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of interferon-stimulated genes that attenuate Ebola virus infection. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolsey, C.; Menicucci, A.R.; Cross, R.W.; Luthra, P.; Agans, K.N.; Borisevich, V.; Geisbert, J.B.; Mire, C.E.; Fenton, K.A.; Jankeel, A.; et al. A VP35 Mutant Ebola Virus Lacks Virulence but Can Elicit Protective Immunity to Wild-Type Virus Challenge. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3032–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, G.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, T.; Zeng, H.; et al. HIV-1 Vif suppresses antiviral immunity by targeting STING. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 19, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatamzas, E.; Hipp, M.M.; Gaughan, D.; Pichulik, T.; Leslie, A.; A Fernandes, R.; Muraro, D.; Booth, S.; Zausmer, K.; Sun, M.; et al. Snapin promotes HIV -1 transmission from dendritic cells by dampening TLR 8 signaling. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2998–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, C.; Civino, A.; Rossi, M.N.; Cifaldi, L.; Lanari, V.; Moneta, G.M.; Caiello, I.; Bracaglia, C.; Montinaro, R.; Novelli, A.; et al. IFNAR2 Deficiency Causing Dysregulation of NK Cell Functions and Presenting With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciol, G.; Moens, L.; Ogishi, M.; Rinchai, D.; Matuozzo, D.; Momenilandi, M.; Kerrouche, N.; Cale, C.M.; Treffeisen, E.R.; Al Salamah, M.; et al. Human inherited complete STAT2 deficiency underlies inflammatory viral diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. et al. Inborn errors of OAS–RNase L in SARS-CoV-2–related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Science (1979) 379, (2023).

- Awasthi, N.; Liongue, C.; Ward, A.C. STAT proteins: a kaleidoscope of canonical and non-canonical functions in immunity and cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D. & Prince, A. Participation of the IL-10RB Related Cytokines, IL-22 and IFN-λ in Defense of the Airway Mucosal Barrier. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10, (2020).

- Gal-Ben-Ari, S.; Barrera, I.; Ehrlich, M.; Rosenblum, K. PKR: A Kinase to Remember. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 11, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, C. E. Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR1), a suppressor of double-stranded RNA–triggered innate immune responses. Journal of Biological Chemistry 294, 1710–1720 (2019).

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xue, Y. ADAR1: a mast regulator of aging and immunity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrhardt, C.; Wolff, T.; Pleschka, S.; Planz, O.; Beermann, W.; Bode, J.G.; Schmolke, M.; Ludwig, S. Influenza A Virus NS1 Protein Activates the PI3K/Akt Pathway To Mediate Antiapoptotic Signaling Responses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3058–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.-S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 inhibits induction of the MHC class I pathway by targeting the STAT1-IRF1-NLRC5 axis. Nat Commun 12, 6602 (2021).

- Zhang, M.; Meng, Y.; Ying, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, S.; Fang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Li, D. Selective activation of STAT3 and STAT5 dictates the fate of myeloid progenitor cells. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deimel, L.P.; Li, Z.; Roy, S.; Ranasinghe, C. STAT3 determines IL-4 signalling outcomes in naïve T cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer zu Horste, G. et al. Fas Promotes T Helper 17 Cell Differentiation and Inhibits T Helper 1 Cell Development by Binding and Sequestering Transcription Factor STAT1. Immunity 48, 556-569.e7 (2018).

- Kerner, G.; Rosain, J.; Guérin, A.; Al-Khabaz, A.; Oleaga-Quintas, C.; Rapaport, F.; Massaad, M.J.; Ding, J.-Y.; Khan, T.; Al Ali, F.; et al. Inherited human IFN-γ deficiency underlies mycobacterial disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3158–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisson-Dupuis, S.; Kong, X.-F.; Okada, S.; Cypowyj, S.; Puel, A.; Abel, L.; Casanova, J.-L. Inborn errors of human STAT1: allelic heterogeneity governs the diversity of immunological and infectious phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012, 24, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogunovic, D.; Byun, M.; Durfee, L.A.; Abhyankar, A.; Sanal, O.; Mansouri, D.; Salem, S.; Radovanovic, I.; Grant, A.V.; Adimi, P.; et al. Mycobacterial Disease and Impaired IFN-γ Immunity in Humans with Inherited ISG15 Deficiency. Science 2012, 337, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, Y.J.; Stetson, D.B. The type I interferonopathies: 10 years on. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 22, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.-P.; Ding, J.-Y.; Yeh, C.-F.; Chi, C.-Y.; Ku, C.-L. Anti-interferon-γ autoantibody-associated immunodeficiency. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 72, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, S.; Döffinger, R.; Picard, C.; Fieschi, C.; Altare, F.; Jouanguy, E.; Abel, L.; Casanova, J.-L. Human interferon-g-mediated immunity is a genetically controlled continuous trait that determines the outcome of mycobacterial invasion. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 178, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreins, A.Y.; Ciancanelli, M.J.; Okada, S.; Kong, X.-F.; Ramírez-Alejo, N.; Kilic, S.S.; El Baghdadi, J.; Nonoyama, S.; Mahdaviani, S.A.; Ailal, F.; et al. Human TYK2 deficiency: Mycobacterial and viral infections without hyper-IgE syndrome. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1641–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Vosse, E. et al. IL-12Rβ1 Deficiency: Mutation Update and Description of the IL12RB1 Variation Database. Hum Mutat 34, 1329–1339 (2013).

- Zheng, J.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Crossland, K.L.; Smeekens, S.P.; Chan, C.M.; Al Shehri, T.; Abinun, M.; Gennery, A.R.; Mann, J.; Lendrem, D.W.; et al. Gain-of-function STAT1 mutations impair STAT3 activity in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). Eur. J. Immunol. 2015, 45, 2834–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarelli, C.; Civino, A.; Rossi, M.N.; Cifaldi, L.; Lanari, V.; Moneta, G.M.; Caiello, I.; Bracaglia, C.; Montinaro, R.; Novelli, A.; et al. IFNAR2 Deficiency Causing Dysregulation of NK Cell Functions and Presenting With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.K.; Huang, S.X.; Chen, J.; Kerner, G.; Gilliaux, O.; Bastard, P.; Dobbs, K.; Hernandez, N.; Goudin, N.; Hasek, M.L.; et al. Severe influenza pneumonitis in children with inherited TLR3 deficiency. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2038–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, S.; Tsumura, M.; Matsubayashi, T.; Karakawa, S.; Kimura, S.; Tamaura, M.; Okano, T.; Naruto, T.; Mizoguchi, Y.; Kagawa, R.; et al. Autosomal recessive complete STAT1 deficiency caused by compound heterozygous intronic mutations. Int. Immunol. 2020, 32, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphonse, N.; Wanford, J.J.; Voak, A.A.; Gay, J.; Venkhaya, S.; Burroughs, O.; Mathew, S.; Lee, T.; Evans, S.L.; Zhao, W.; et al. A family of conserved bacterial virulence factors dampens interferon responses by blocking calcium signaling. Cell 2022, 185, 2354–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jing, H.; Martin-Nalda, A.; Bastard, P.; Rivière, J.G.; Liu, Z.; Colobran, R.; Lee, D.; Tung, W.; Manry, J.; et al. Inborn errors of TLR3- or MDA5-dependent type I IFN immunity in children with enterovirus rhombencephalitis. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, S.; Tsumura, M.; Matsubayashi, T.; Karakawa, S.; Kimura, S.; Tamaura, M.; Okano, T.; Naruto, T.; Mizoguchi, Y.; Kagawa, R.; et al. Autosomal recessive complete STAT1 deficiency caused by compound heterozygous intronic mutations. Int. Immunol. 2020, 32, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.J.A.; Hambleton, S. Human Disease Phenotypes Associated with Loss and Gain of Function Mutations in STAT2: Viral Susceptibility and Type I Interferonopathy. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 41, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, S.; DeLeo, F.R.; Elloumi, H.Z.; Hsu, A.P.; Uzel, G.; Brodsky, N.; Freeman, A.F.; Demidowich, A.; Davis, J.; Turner, M.L.C.; et al. STAT3 Mutations in the Hyper-IgE Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupov, I.P.; Voiles, L.; Han, L.; Schwartz, A.; De La Rosa, M.; Oza, K.; Pelloso, D.; Sahu, R.P.; Travers, J.B.; Robertson, M.J.; et al. Acquired STAT4 deficiency as a consequence of cancer chemotherapy. Blood 2011, 118, 6097–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Mai, H.; Peng, J.; Zhou, B.; Hou, J.; Jiang, D. STAT4: an immunoregulator contributing to diverse human diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.-Z.; Liu, W.; Xia, Y.; Yin, H.-M.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Su, D.; Yan, L.-F.; Gu, A.-H.; Zhou, Y. The pro-inflammatory signalling regulator Stat4 promotes vasculogenesis of great vessels derived from endothelial precursors. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torpey, N.; Maher, S.E.; Bothwell, A.L.M.; Pober, J.S. Interferon α but Not Interleukin 12 Activates STAT4 Signaling in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 26789–26796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, G.M.; Grassmann, S.; Lau, C.M.; Rapp, M.; Villarino, A.V.; Friedrich, C.; Gasteiger, G.; O’shea, J.J.; Sun, J.C. Divergent Role for STAT5 in the Adaptive Responses of Natural Killer Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108498–108498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, M.; Salmani, T.; Arsang-Jang, S.; Omrani, M.D.; Mazdeh, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Sayad, A.; Taheri, M. STAT5a and STAT6 gene expression levels in multiple sclerosis patients. Cytokine 2018, 106, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumida, T.S.; Dulberg, S.; Schupp, J.C.; Lincoln, M.R.; Stillwell, H.A.; Axisa, P.-P.; Comi, M.; Unterman, A.; Kaminski, N.; Madi, A.; et al. Type I interferon transcriptional network regulates expression of coinhibitory receptors in human T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, T.; Jenks, J.; Nadeau, K.C. The STAT5b Pathway Defect and Autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpathiou, G.; Papoudou-Bai, A.; Ferrand, E.; Dumollard, J.M.; Peoc’h, M. STAT6: a review of a signaling pathway implicated in various diseases with a special emphasis in its usefulness in pathology. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 2021, 223, 153477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H. et al. The inhibition of IL-2/IL-2R gives rise to CD8+ T cell and lymphocyte decrease through JAK1-STAT5 in critical patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Cell Death Dis 11, 429 (2020).

- Parackova, Z.; Zentsova, I.; Vrabcova, P.; Sediva, A.; Bloomfield, M. Aberrant tolerogenic functions and proinflammatory skew of dendritic cells in STAT1 gain-of-function patients may contribute to autoimmunity and fungal susceptibility. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 246, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogunovic, D.; Byun, M.; Durfee, L.A.; Abhyankar, A.; Sanal, O.; Mansouri, D.; Salem, S.; Radovanovic, I.; Grant, A.V.; Adimi, P.; et al. Mycobacterial Disease and Impaired IFN-γ Immunity in Humans with Inherited ISG15 Deficiency. Science 2012, 337, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, L.; Fracella, M.; Frasca, F.; D’auria, A.; Santinelli, L.; Maddaloni, L.; Bugani, G.; Bitossi, C.; Gentile, M.; Ceccarelli, G.; et al. Alterations in the Expression of IFN Lambda, IFN Gamma and Toll-like Receptors in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Birkenbach, M.; Chen, S. Patterns of Inflammatory Cell Infiltration and Expression of STAT6 in the Lungs of Patients With COVID-19: An Autopsy Study. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2022, 30, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Furcas, M.; Cetani, F.; Marcocci, C.; Falorni, A.; Perniola, R.; Pura, M.; Wolff, A.S.B.; Husebye, E.S.; Lilic, D.; et al. Autoantibodies against Type I Interferons as an Additional Diagnostic Criterion for Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type I. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 4389–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghale, R.; Spottiswoode, N.; Anderson, M.S.; Mitchell, A.; Wang, G.; Calfee, C.S.; DeRisi, J.L.; Langelier, C.R. Prevalence of type-1 interferon autoantibodies in adults with non-COVID-19 acute respiratory failure. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.H.; Ortega-Villa, A.M.; Hunsberger, S.; Chetchotisakd, P.; Anunnatsiri, S.; Mootsikapun, P.; Rosen, L.B.; Zerbe, C.S.; Holland, S.M. Natural History and Evolution of Anti-Interferon-γ Autoantibody-Associated Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Thailand and the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 71, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sancho, L. et al. Functional landscape of SARS-CoV-2 cellular restriction. Mol Cell 81, 2656-2668.e8 (2021).

- Brass, A.L.; Huang, I.-C.; Benita, Y.; John, S.P.; Krishnan, M.N.; Feeley, E.M.; Ryan, B.J.; Weyer, J.L.; van der Weyden, L.; Fikrig, E.; et al. The IFITM Proteins Mediate Cellular Resistance to Influenza A H1N1 Virus, West Nile Virus, and Dengue Virus. Cell 2009, 139, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, A. A. et al. Natural mutations in IFITM3 modulate post-translational regulation and toggle antiviral specificity. EMBO Rep 17, 1657–1671 (2016).

- John, S.P.; Chin, C.R.; Perreira, J.M.; Feeley, E.M.; Aker, A.M.; Savidis, G.; Smith, S.E.; Elia, A.E.H.; Everitt, A.R.; Vora, M.; et al. The CD225 Domain of IFITM3 Is Required for both IFITM Protein Association and Inhibition of Influenza A Virus and Dengue Virus Replication. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7837–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Golani, G.; Lolicato, F.; Lahr, C.; Beyer, D.; Herrmann, A.; Wachsmuth-Melm, M.; Reddmann, N.; Brecht, R.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; et al. IFITM3 blocks influenza virus entry by sorting lipids and stabilizing hemifusion. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, J.S.; Zani, A.; Kenney, A.D. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) limits lethality of SARS-CoV-2 in mice. 2022, 208, 51.17–51.17. [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.-Y. et al. The innate immunity protein IFITM3 modulates γ-secretase in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 586, 735–740 (2020).

- Pidugu, V.K.; Pidugu, H.B.; Wu, M.-M.; Liu, C.-J.; Lee, T.-C. Emerging Functions of Human IFIT Proteins in Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, J.K.S.; Xu, D.; Licursi, M.; Joyce, M.A.; Saffran, H.A.; Liu, K.; Gohda, J.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Hirasawa, K. Interferon regulatory factor 3 mediates effective antiviral responses to human coronavirus 229E and OC43 infection. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 930086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease suppresses type I interferon responses by deubiquitinating STING. Sci Signal 16, (2023).

- Bastard, P.; Rosen, L.B.; Zhang, Q.; Michailidis, E.; Hoffmann, H.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Dorgham, K.; Philippot, Q.; Rosain, J.; Béziat, V.; et al. Auto-antibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020, 370, eabd4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, D.; Mezidi, M.; Bastard, P.; Perret, M.; Saker, K.; Fabien, N.; Pescarmona, R.; Lombard, C.; Walzer, T.; Casanova, J.; et al. Antibodies against type I interferon: detection and association with severe clinical outcome in COVID-19 patients. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2021, 10, e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Zheng, F.; Li, L.; Jin, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Zeng, J.; Tang, L.; Li, Z.; Xia, N.; et al. A Chinese host genetic study discovered IFNs and causality of laboratory traits on COVID-19 severity. iScience 2021, 24, 103186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Zhu, B.; Chen, D. Type I interferon-mediated tumor immunity and its role in immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Cui, X.; Dai, Y.; Wang, C.; Feng, W.; Lv, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Ru, Y.; et al. Loss of IRF7 accelerates acute myeloid leukemia progression and induces VCAM1-VLA-4 mediated intracerebral invasion. Oncogene 2022, 41, 2303–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F. et al. Escape from IFN-γ-dependent immunosurveillance in tumorigenesis. J Biomed Sci 24, 10 (2017).

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Zhu, B.; Chen, D. Type I interferon-mediated tumor immunity and its role in immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sun, W.; Dai, T.; Wang, A.; Wu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; et al. A Dual Role of Type I Interferons in Antitumor Immunity. Adv. Biosyst. 2020, 4, e1900237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.; Vieyres, G.; Terczyńska-Dyla, E.; Anggakusuma, X.; Dijkman, R.; Gad, H.H.; Akhtar, H.; Geffers, R.; Vondran, F.W.R.; Thiel, V.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals a classical interferon signature induced by IFNλ4 in human primary cells. Genes Immun. 2015, 16, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruetsch, C.; Brglez, V.; Crémoni, M.; Zorzi, K.; Fernandez, C.; Boyer-Suavet, S.; Benzaken, S.; Demonchy, E.; Risso, K.; Courjon, J.; et al. Functional Exhaustion of Type I and II Interferons Production in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Front. Med. 2021, 7, 603961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scagnolari, C.; Pierangeli, A.; Frasca, F.; Bitossi, C.; Viscido, A.; Oliveto, G.; Scordio, M.; Mazzuti, L.; Di Carlo, D.; Gentile, M.; et al. Differential induction of type I and III interferon genes in the upper respiratory tract of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Virus Res. 2021, 295, 198283–198283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contoli, M.; Papi, A.; Tomassetti, L.; Rizzo, P.; Sega, F.V.D.; Fortini, F.; Torsani, F.; Morandi, L.; Ronzoni, L.; Zucchetti, O.; et al. Blood Interferon-α Levels and Severity, Outcomes, and Inflammatory Profiles in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 648004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rodríguez, J.C.; Hancock, S.J.; Li, K.; Crotta, S.; Barrington, C.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Priestnall, S.L.; Aubé, J.; Wack, A.; Klenerman, P.; et al. Type I interferons drive MAIT cell functions against bacterial pneumonia. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syedbasha, M.; Bonfiglio, F.; Linnik, J.; Stuehler, C.; Wüthrich, D.; Egli, A. Interferon-λ Enhances the Differentiation of Naive B Cells into Plasmablasts via the mTORC1 Pathway. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xue, M.; Fu, F.; Yin, L.; Feng, L.; Liu, P. IFN-Lambda 3 Mediates Antiviral Protection Against Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus by Inducing a Distinct Antiviral Transcript Profile in Porcine Intestinal Epithelia. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, M.; Maleh, P.A.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Moulana, Z.; Sepidarkish, M.; Rezanejad, M.; Mirzakhani, M.; Ebrahimpour, S.; Ghorbani, H.; Ahmadnia, Z.; et al. Linkage of Lambda Interferons in Protection Against Severe COVID-19. J. Interf. Cytokine Res. 2021, 41, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syedbasha, M.; Linnik, J.; Santer, D.; O'Shea, D.; Barakat, K.; Joyce, M.; Khanna, N.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Houghton, M.; Egli, A. An ELISA Based Binding and Competition Method to Rapidly Determine Ligand-receptor Interactions. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, e53575–e53575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.; Hilzendeger, C.; Moermans, C.; Schleich, F.; Henket, M.; Kebadze, T.; Mallia, P.; Edwards, M.R.; Johnston, S.L.; Louis, R. Raised interferon-β, type 3 interferon and interferon-stimulated genes - evidence of innate immune activation in neutrophilic asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2016, 47, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Schnepf, D.; Ohnemus, A.; Ong, L.C.; Gad, H.H.; Hartmann, R.; Lycke, N.; Staeheli, P. Interferon-λ Improves the Efficacy of Intranasally or Rectally Administered Influenza Subunit Vaccines by a Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin-Dependent Mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.W.; Constant, D.A.; Nice, T.J. Interferon Lambda in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamayor, L.; López-García, D.; Rivero, V.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Nogales, A.; DeDiego, M.L. The IFN-stimulated gene IFI27 counteracts innate immune responses after viral infections by interfering with RIG-I signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1176177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamayor, L.; Rivero, V.; López-García, D.; Topham, D.J.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Nogales, A.; DeDiego, M.L. Interferon alpha inducible protein 6 is a negative regulator of innate immune responses by modulating RIG-I activation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilunda, V.; Martinez-Aguado, P.; Xia, L.C.; Cheney, L.; Murphy, A.; Veksler, V.; Ruiz, V.; Calderon, T.M.; Berman, J.W. Transcriptional Changes in CD16+ Monocytes May Contribute to the Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 665773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, D.J.; Hess, S.; Knobeloch, K.-P. Strategies to Target ISG15 and USP18 Toward Therapeutic Applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 7, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillyer, P. et al. Expression profiles of human interferon-alpha and interferon-lambda subtypes are ligand- and cell-dependent. Immunol Cell Biol 90, 774–783 (2012).

- Henig, N.; Avidan, N.; Mandel, I.; Staun-Ram, E.; Ginzburg, E.; Paperna, T.; Pinter, R.Y.; Miller, A. Interferon-Beta Induces Distinct Gene Expression Response Patterns in Human Monocytes versus T cells. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e62366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, A.; Ozarkar, S.; Li, H.; Lee, C.H.; Hemann, E.A.; Nadjsombati, M.S.; Hendricks, M.R.; So, L.; Green, R.; Roy, C.N.; et al. Differential Activation of the Transcription Factor IRF1 Underlies the Distinct Immune Responses Elicited by Type I and Type III Interferons. Immunity 2019, 51, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, L.; Zhai, L.; Yue, Q.; Liu, H.; Ren, S.; Jiang, X.; Gao, F.; Bai, S.; Li, H.; et al. Comparative Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses Prove that IFN-λ1 is a More Potent Inducer of ISGs than IFN-α against Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus in Porcine Intestinal Epithelial Cells. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 3697–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soday, L.; Potts, M.; Hunter, L.M.; Ravenhill, B.J.; Houghton, J.W.; Williamson, J.C.; Antrobus, R.; Wills, M.R.; Matheson, N.J.; Weekes, M.P. Comparative Cell Surface Proteomic Analysis of the Primary Human T Cell and Monocyte Responses to Type I Interferon. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, M.H.S.; Mahmoud, A.; Bruns, H.; Echchannaoui, H.; Kriegsmann, K.; Lutz, R.; Raab, M.S.; Bertsch, U.; Munder, M.; Jauch, A.; et al. Selective elimination of immunosuppressive T cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2602–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.P.; Nguyen, H.N.; Gomez-Rivas, E.; Jeong, Y.; Jonsson, A.H.; Chen, A.F.; Lange, J.K.; Dyer, G.S.; Blazar, P.; Earp, B.E.; et al. SLAMF7 engagement superactivates macrophages in acute and chronic inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabf2846–eabf2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attur, M.; Zhou, H.; Samuels, J.; Krasnokutsky, S.; Yau, M.; Scher, J.U.; Doherty, M.; Wilson, A.G.; Bencardino, J.; Hochberg, M.; et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN) gene variants predict radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis and risk of incident disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 79, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes-Barragan, L. et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce type I interferon and reduce viral replication in 1 airway epithelial cells after SARS-CoV-2 infection 2 3 4. [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, J.; Babiuch, L. Results of the prolonged use of natural human interferon alpha (nHuIFNα) lozenges in the treatment of human immune deficiency virus infection. Cytokine 1994, 6, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, R.; González, D.; Rivero, H.B.; Rivero, J.C.; Pérez, A.; Lopez, L.D.R.; Mezquia, N.; Venegas, R.; Betancourt, J.R.; Domínguez, R.E.; et al. Therapeutic Effectiveness of Interferon Alpha 2b Treatment for COVID-19 Patient Recovery. J. Interf. Cytokine Res. 2020, 40, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierangeli, A. et al. Comparison by Age of the Local Interferon Response to SARS-CoV-2 Suggests a Role for IFN-ε and -ω. Front Immunol 13, 873232 (2022).

- Emilie, D.; Burgard, M.; Lascoux-Combe, C.; Laughlin, M.; Krzysiek, R.; Pignon, C.; Rudent, A.; Molina, J.-M.; Livrozet, J.-M.; Souala, F.; et al. Early control of HIV replication in primary HIV-1 infection treated with antiretroviral drugs and pegylated IFNα: results from the Primoferon A (ANRS 086) Study. AIDS 2001, 15, 1435–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; MacArthur, M.R.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Zarin, P.; Hanna, B.S.; Wang, Z.-H.; Xiang, X.; Fish, E.N. Interferon-α2b Treatment for COVID-19 Is Associated with Improvements in Lung Abnormalities. Viruses 2020, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; MacArthur, M.R.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Zarin, P.; Hanna, B.S.; Wang, Z.-H.; Xiang, X.; Fish, E.N. Interferon-α2b Treatment for COVID-19 Is Associated with Improvements in Lung Abnormalities. Viruses 2020, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi-Monfared, E.; Rahmani, H.; Khalili, H.; Hajiabdolbaghi, M.; Salehi, M.; Abbasian, L.; Kazemzadeh, H.; Yekaninejad, M.S. A Randomized Clinical Trial of the Efficacy and Safety of Interferon β-1a in Treatment of Severe COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakos, K.; Tsakiris, A.; Tsibris, G.; Voutsinas, P.-M.; Panagopoulos, P.; Kosmidou, M.; Petrakis, V.; Gravvani, A.; Gkavogianni, T.; Klouras, E.; et al. Early Start of Oral Clarithromycin Is Associated with Better Outcome in COVID-19 of Moderate Severity: The ACHIEVE Open-Label Single-Arm Trial. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 2333–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalamova, L. et al. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 exhibits an increased resilience to the antiviral type I interferon response. PNAS Nexus 1, (2022).

- Lee-Kirsch, M.A. The Type I Interferonopathies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2017, 68, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.C.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, S.; Jang, H.; Zheng, A.; Kwon, S.; Repine, J.E. Nasopharyngeal Type-I Interferon for Immediately Available Prophylaxis Against Emerging Respiratory Viral Infections. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 660298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.; Ashkar, A.A. The Dual Nature of Type I and Type II Interferons. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Shin, E.-C. The type I interferon response in COVID-19: implications for treatment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z. et al. Nasally delivered interferon-λ protects mice against infection by SARS-CoV-2 variants including Omicron. Cell Rep 39, 110799 (2022).

- Cooles, F.A.H.; Tarn, J.; Lendrem, D.W.; Naamane, N.; Lin, C.M.; Millar, B.; Maney, N.J.; E Anderson, A.; Thalayasingam, N.; Diboll, J.; et al. Interferon-α-mediated therapeutic resistance in early rheumatoid arthritis implicates epigenetic reprogramming. Rheumatol. 2022, 81, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, E. C. Interferons α and β in cancer: therapeutic opportunities from new insights. Nat Rev Drug Discov 18, 219–234 (2019).

- Borden, E.C.; Sen, G.C.; Uze, G.; Silverman, R.H.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Foster, G.R.; Stark, G.R. Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niles, M. A. et al. Macrophages and Dendritic Cells Are Not the Major Source of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Upon SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front Immunol 12, (2021).

- Trouillet-Assant, S.; Viel, S.; Gaymard, A.; Pons, S.; Richard, J.-C.; Perret, M.; Villard, M.; Brengel-Pesce, K.; Lina, B.; Mezidi, M.; et al. Type I IFN immunoprofiling in COVID-19 patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, C.-K.; Lam, J.-Y.; Wong, W.-M.; Mak, L.-F.; Wang, X.; Chu, H.; Cai, J.-P.; Jin, D.-Y.; To, K.K.-W.; Chan, J.F.-W.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 nsp13, nsp14, nsp15 and orf6 function as potent interferon antagonists. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins NSP1 and NSP13 inhibit interferon activation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One 16, e0253089 (2021).

- Kumar, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 1 Inhibits the Interferon Response by Causing Depletion of Key Host Signaling Factors. J Virol 95, (2021).

- Rincon-Arevalo, H.; Aue, A.; Ritter, J.; Szelinski, F.; Khadzhynov, D.; Zickler, D.; Stefanski, L.; Lino, A.C.; Körper, S.; Eckardt, K.; et al. Altered increase in STAT1 expression and phosphorylation in severe COVID-19. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 52, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, H.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S.; Ma, H.; Liu, D.; et al. Antiviral activity of porcine interferon delta 8 against pesudorabies virus in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 177, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Liu, X.; Hu, D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, P. Swine Enteric Coronaviruses (PEDV, TGEV, and PDCoV) Induce Divergent Interferon-Stimulated Gene Responses and Antigen Presentation in Porcine Intestinal Enteroids. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 826882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ke, H.; Blikslager, A.; Fujita, T.; Yoo, D. Type III Interferon Restriction by Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus and the Role of Viral Protein nsp1 in IRF1 Signaling. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yoo, D. Immune evasion of porcine enteric coronaviruses and viral modulation of antiviral innate signaling. Virus Res. 2016, 226, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaconis, G. et al. Rotavirus NSP1 Inhibits Type I and Type III Interferon Induction. Viruses 13, 589 (2021).

- Fisher, T. et al. Parsing the role of NSP1 in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep 39, 110954 (2022).

- Ferreira-Gomes, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 in severe COVID-19 induces a TGF-β-dominated chronic immune response that does not target itself. Nat Commun 12, (2021).

- Barros-Martins, J.; Förster, R.; Bošnjak, B. NK cell dysfunction in severe COVID-19: TGF-β-induced downregulation of integrin beta-2 restricts NK cell cytotoxicity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, M.; Tizian, C.; Ferreira-Gomes, M.; Niemeyer, D.; Jones, T.C.; Heinrich, F.; Frischbutter, S.; Angermair, S.; Hohnstein, T.; Mattiola, I.; et al. Untimely TGFβ responses in COVID-19 limit antiviral functions of NK cells. Nature 2021, 600, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros-Martins, J.; Förster, R.; Bošnjak, B. NK cell dysfunction in severe COVID-19: TGF-β-induced downregulation of integrin beta-2 restricts NK cell cytotoxicity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces mixed M1/M2 phenotype in circulating monocytes and alterations in both dendritic cell and monocyte subsets. PLoS One 15, e0241097–e0241097 (2020).

- Setaro, A. C. & Gaglia, M. M. All hands on deck: SARS-CoV-2 proteins that block early anti-viral interferon responses. Curr Res Virol Sci 2, 100015 (2021).

- Miorin, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Orf6 hijacks Nup98 to block STAT nuclear import and antagonize interferon signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 28344–28354 (2020).

- Wu, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF9b inhibits RIG-I-MAVS antiviral signaling by interrupting K63-linked ubiquitination of NEMO. Cell Rep 34, 108761 (2021).

- Guo, K. et al. Interferon resistance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, (2022).

- Brisse, M.; Ly, H. Comparative Structure and Function Analysis of the RIG-I-Like Receptors: RIG-I and MDA5. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelli Bozzo, C. et al. IFITM proteins promote SARS-CoV-2 infection and are targets for virus inhibition in vitro. Nat Commun 12, 4584 (2021).

- McKellar, J. , Rebendenne, A., Wencker, M., Moncorgé, O. & Goujon, C. Mammalian and Avian Host Cell Influenza A Restriction Factors. Viruses 13, 522 (2021).

- Cervantes, J.L.; Weinerman, B.; Basole, C.; Salazar, J.C. TLR8: the forgotten relative revindicated. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2012, 9, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; Ashkar, A.A. The Dual Nature of Type I and Type II Interferons. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidahmed, A.M.; León, A.J.; Bosinger, S.E.; Banner, D.; Danesh, A.; Cameron, M.J.; Kelvin, D.J. CXCL10 contributes to p38-mediated apoptosis in primary T lymphocytes in vitro. Cytokine 2012, 59, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, B.A.; Elemam, N.M.; Maghazachi, A.A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors during COVID-19 infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Casillas, A. , Redwan, E. M. & Uversky, V. N. SARS-CoV-2: A Master of Immune Evasion. Biomedicines 10, 1339 (2022).

- Yoo, J.-S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 inhibits induction of the MHC class I pathway by targeting the STAT1-IRF1-NLRC5 axis. Nat Commun 12, 6602 (2021).

- Rashid, F. et al. Roles and functions of SARS-CoV-2 proteins in host immune evasion. Front Immunol 13, 940756 (2022).

- Glennon-Alty, L.; Moots, R.J.; Edwards, S.W.; Wright, H.L. Type I interferon regulates cytokine-delayed neutrophil apoptosis, reactive oxygen species production and chemokine expression. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 203, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, I.; Granucci, F.; Broggi, A. Interferon (IFN)-λ Takes the Helm: Immunomodulatory Roles of Type III IFNs. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaroli, C.; Fram, T.R.; Sharma, N.S.; Patel, S.B.; Tipper, J.; Robison, S.W.; Russell, D.W.; Fortmann, S.D.; Banday, M.M.; Soto-Vazquez, Y.M.; et al. Interferon-dependent signaling is critical for viral clearance in airway neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennon-Alty, L.; Moots, R.J.; Edwards, S.W.; Wright, H.L. Type I interferon regulates cytokine-delayed neutrophil apoptosis, reactive oxygen species production and chemokine expression. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 203, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijano, D.R.; Vu, L.D.; Kauvar, L.M.; Tripp, R.A.; Polack, F.P.; Cormier, S.A. Role of Type I Interferon (IFN) in the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Immune Response and Disease Severity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, S.; Hillyer, P.; Le Nouën, C.; Buchholz, U.J.; Rabin, R.L.; Collins, P.L.; Bukreyev, A. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Interferon Antagonist NS1 Protein Suppresses and Skews the Human T Lymphocyte Response. PLOS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus activates Rab5a to suppress IRF1-dependent IFN-λ production, subverting the antiviral defense of airway epithelial cells. J Virol 95, e02333-20 (2021).

- Mortezaee, K. & Majidpoor, J. Cellular immune states in SARS-CoV-2-induced disease. Front Immunol 13, 1016304 (2022).

- De Maeyer, E. & De Maeyer-Guignard, J. Type I Interferons. Int Rev Immunol 17, 53–73 (1998).

- Vremec, D.; O'Keeffe, M.; Hochrein, H.; Fuchsberger, M.; Caminschi, I.; Lahoud, M.; Shortman, K. Production of interferons by dendritic cells, plasmacytoid cells, natural killer cells, and interferon-producing killer dendritic cells. Blood 2006, 109, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cecco, M.; Ito, T.; Petrashen, A.P.; Elias, A.E.; Skvir, N.J.; Criscione, S.W.; Caligiana, A.; Brocculi, G.; Adney, E.M.; Boeke, J.D.; et al. L1 drives IFN in senescent cells and promotes age-associated inflammation. Nature 2019, 566, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. et al. SARS-CoV-2-encoded inhibitors of human LINE-1 retrotransposition. J Med Virol 95, (2023).

- Crow, M.K. Long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE-1): Potential triggers of systemic autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity 2009, 43, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Møhlenberg, M.; Terczyńska-Dyla, E.; Winther, K.G.; Hansen, N.H.; Vad-Nielsen, J.; Laloli, L.; Dijkman, R.; Nielsen, A.L.; Gad, H.H.; et al. The IFNL4 Gene Is a Noncanonical Interferon Gene with a Unique but Evolutionarily Conserved Regulation. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marongiu, L.; Protti, G.; Facchini, F.A.; Valache, M.; Mingozzi, F.; Ranzani, V.; Putignano, A.R.; Salviati, L.; Bevilacqua, V.; Curti, S.; et al. Maturation signatures of conventional dendritic cell subtypes in COVID-19 suggest direct viral sensing. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 52, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B. Innate and Adaptive Immunity during SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Biomolecular Cellular Markers and Mechanisms. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sposito, B.; Broggi, A.; Pandolfi, L.; Crotta, S.; Clementi, N.; Ferrarese, R.; Sisti, S.; Criscuolo, E.; Spreafico, R.; Long, J.M.; et al. The interferon landscape along the respiratory tract impacts the severity of COVID-19. Cell 2021, 184, 4953–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgoin, P. CD169 and CD64 could help differentiate bacterial from CoVID -19 or other viral infections in the Emergency Department. Cytometry Part A 2021, 99, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipi, M. & Jack, S. Interferons in the Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2020, 22, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Errante, P.R.; Frazao, J.B.; Condino-Neto, A. The Use of Interferon-Gamma Therapy in Chronic Granulomatous Disease. Recent Patents Anti-Infective Drug Discov. 2008, 3, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-F.; Zhao, F.-R.; Shao, J.-J.; Xie, Y.-L.; Chang, H.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-G. Interferon-omega: Current status in clinical applications. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 52, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. Anti-Lyssaviral Activity of Interferons κ and ω from the Serotine Bat, Eptesicus serotinus. J Virol 2014, 88, 5444–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, S.S.; Darling, T.; Hume, A.J.; Davey, R.A.; Feng, F.; Mühlberger, E.; Kepler, T.B. Egyptian Rousette IFN-ω Subtypes Elicit Distinct Antiviral Effects and Transcriptional Responses in Conspecific Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).