Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

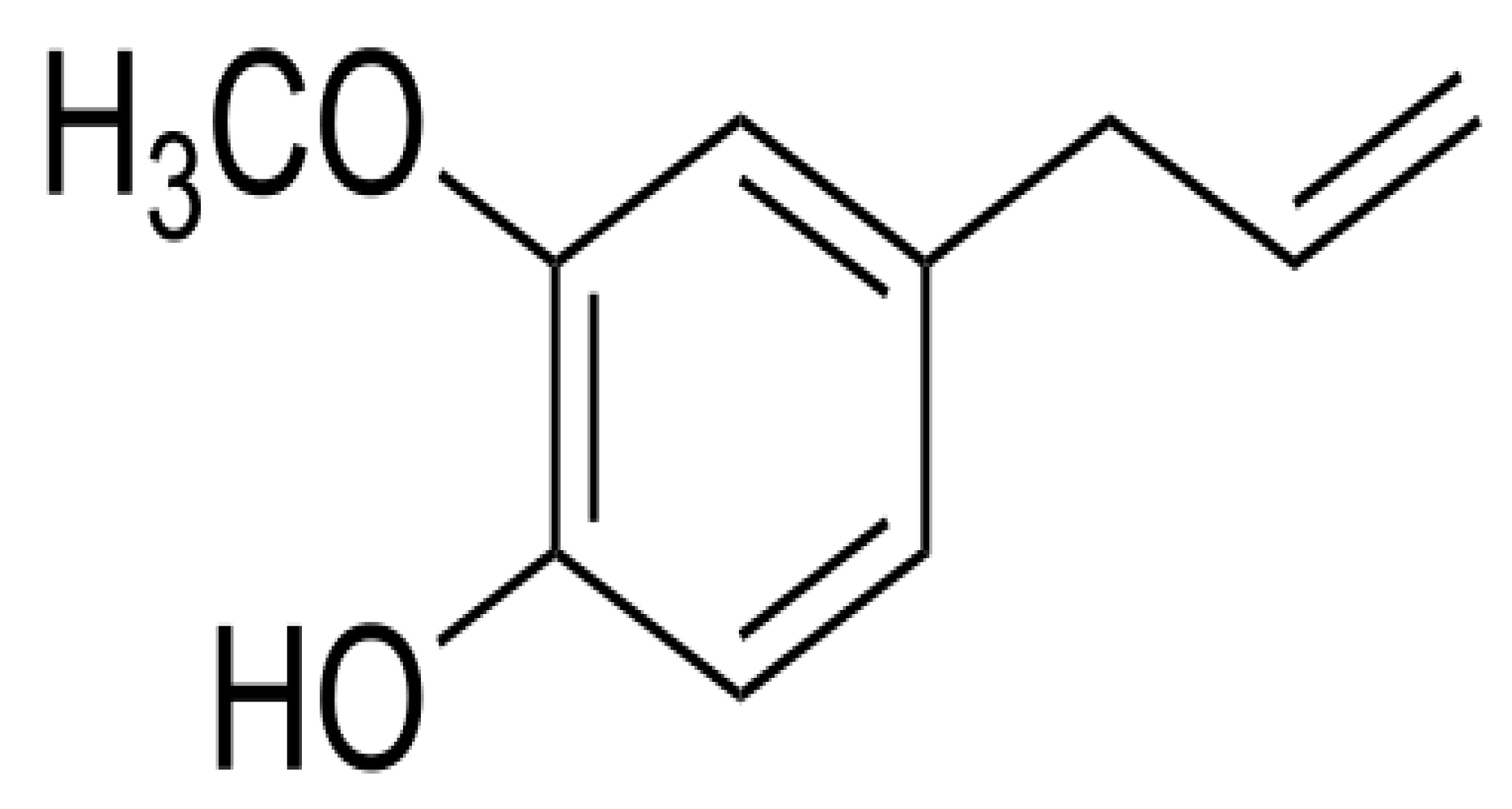

2. Uses of Ocimum Sanctum (Tulsi)

3. Health Effects of HMs

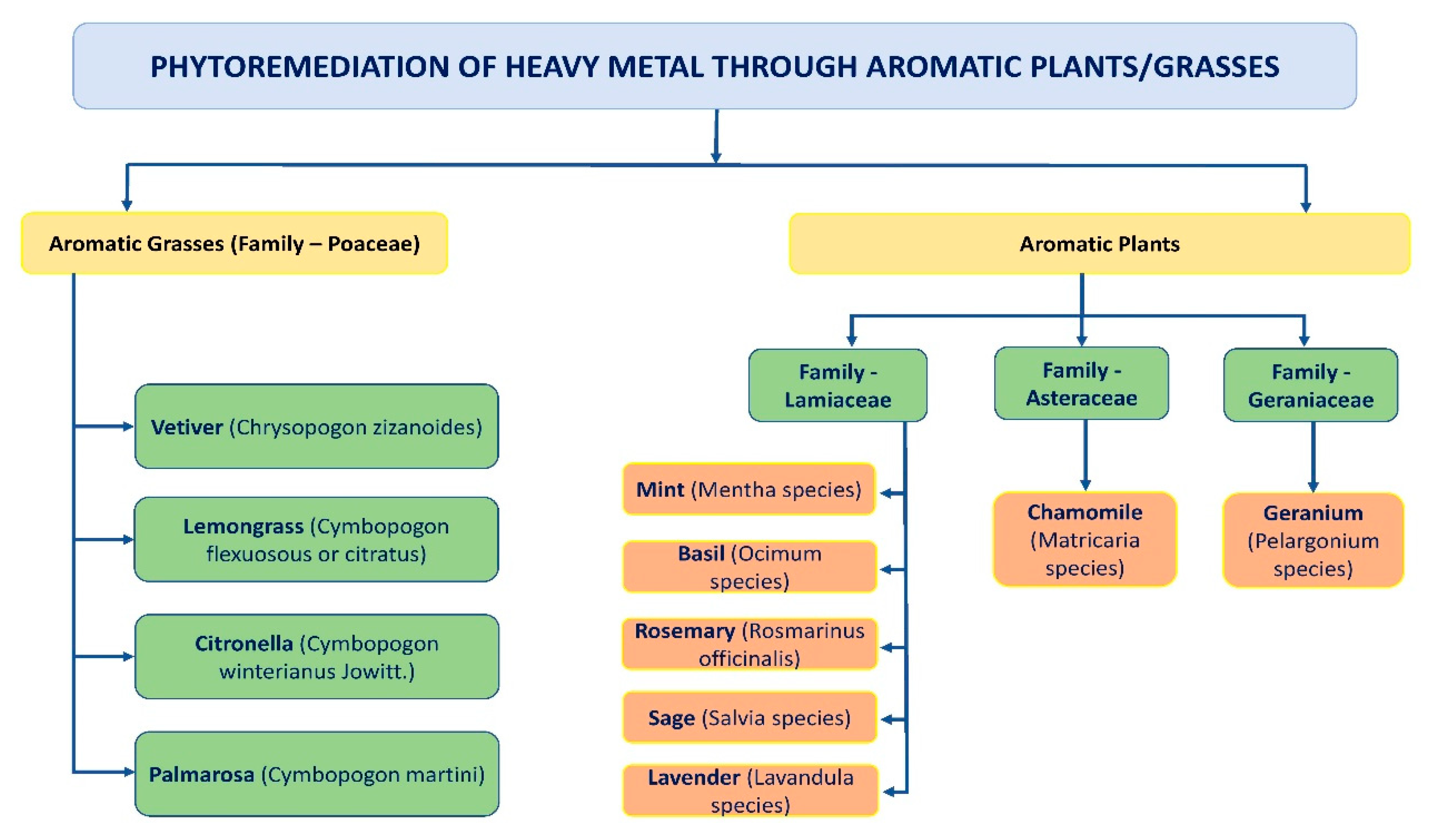

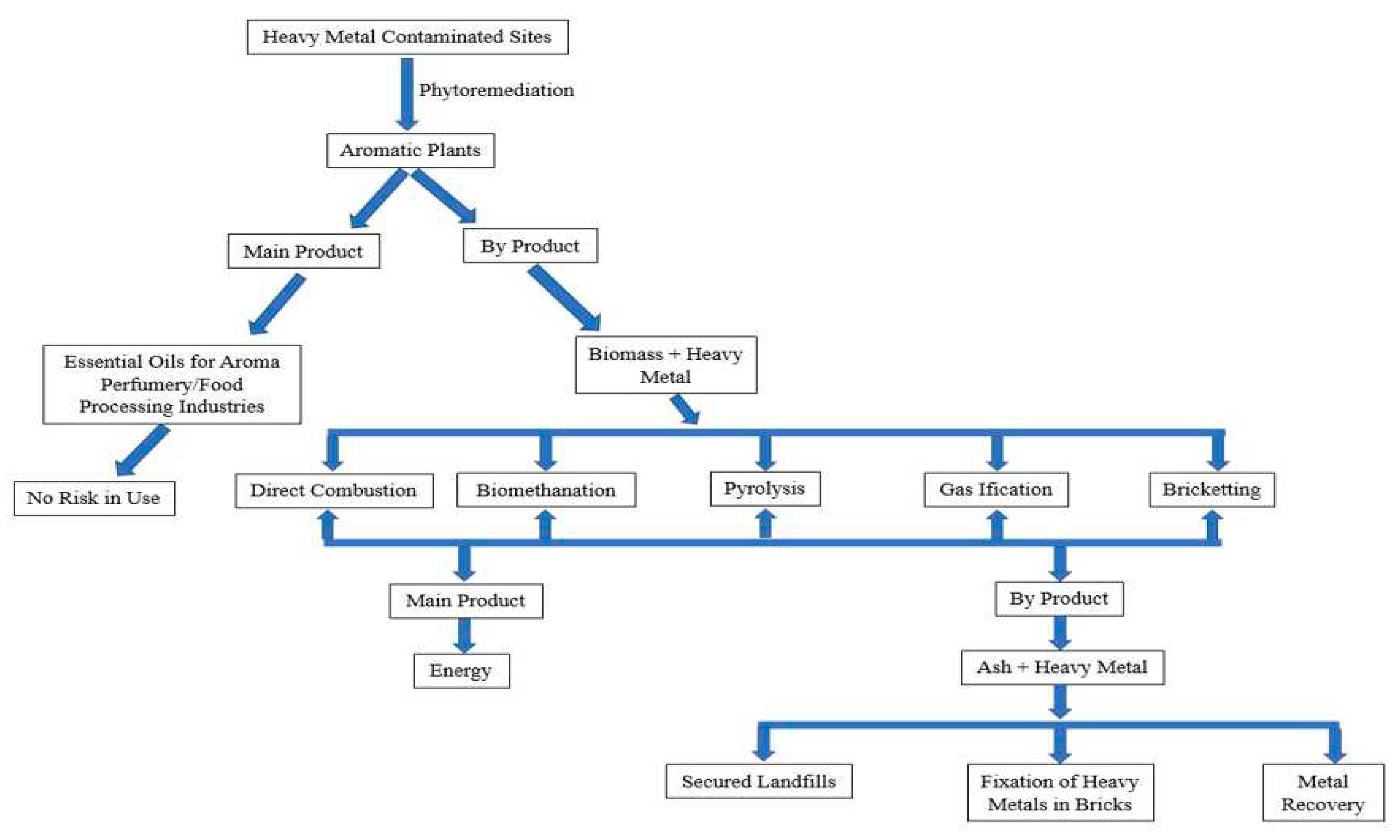

4. Mechanism of Phytoremediation

5. Limitation of Phytoremediation

- (i)

- This technique requires more time.

- (ii)

- The efficiency of this technique is less due to the slow growth rate of plants and less production of biomass.

- (iii)

- The mobilization of some metals is less due to tightly bound metal ions.

- (iv)

- There is a risk of contamination of the food chain due to the lack of proper care.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (i)

- Long-term monitoring is required for the assessment of risks which are involved with the phytoremediation.

- (ii)

- More research is required to relate to the phytoremediation potential of medicinal/aromatic plants, which may lead to the development of “Green scented technology” in the future.

- (iii)

- This technique should be commercialized on a huge scale. So that it will ensure food security in a sustainable way for making the earth a more beautiful place to live.

Acknowledgements

References

- Adigun, M.; Are, K. Comparatives Effectiveness of Two Vetiveria Grasses Species Chrysopogon zizanioides and Chrysopogon nigritana for the Remediation of Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals. Am. J. Exp. Agric. 2015, 8, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affholder, Marie-Cécile, et al. "Transfer of metals and metalloids from soil to shoots in wild rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) growing on a former lead smelter site: Human exposure risk." Science of the total environment 454 (2013): 219-229.

- Akoumianaki-Ioannidou, Anastasia, et al. "The effects of Cd and Zn interactions on the concentration of Cd and Zn in sweet bush basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and peppermint (Mentha piperita L.)." Fresenius Environ Bull 24.1 (2015): 77-83.

- Alaboudi, K.A.; Ahmed, B.; Brodie, G. Phytoremediation of Pb and Cd contaminated soils by using sunflower ( Helianthus annuus ) plant. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2018, 63, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Sadre, et al. “Estimation of Heavy Metals and Fluoride Ion in Vegetables Grown Nearby the Stretch of River Yamuna, Delhi (NCR), India”. Indian Journal of Environmental Protection 43 (2023): 64-73.

- Alamo-Nole, L.; Su, Y.-F. Translocation of cadmium in Ocimum basilicum at low concentration of CdSSe nanoparticles. Appl. Mater. Today 2017, 9, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Hazrat, Muhammad Naseer, and Muhammad Anwar Sajad. "Phytoremediation of heavy metals by Trifolium alexandrinum." International Journal of Environmental Sciences 2.3 (2012): 1459-1469.

- Alkorta, Irina, et al. "Recent findings on the phytoremediation of soils contaminated with environmentally toxic heavy metals and metalloids such as zinc, cadmium, lead, and arsenic." Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology 3.1 (2004): 71-90.

- Andrade Júnior, Waldemar Viana, et al. "Effect of cadmium on young plants of Virola surinamensis." AoB Plants 11.3 (2019): plz022.

- Angelova, Violina R., et al. "Potential of lavender (Lavandula vera L.) for phytoremediation of soils contaminated with heavy metals." Int J Biol Biomol Agric Food Biotechnol Eng 9 (2015): 465-472.

- Anwar, S.; Nawaz, M.F.; Gul, S.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Kareem, A. Uptake and distribution of minerals and heavy metals in commonly grown leafy vegetable species irrigated with sewage water. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babarinde, Adesola, et al. "Comparative study on the biosorption of Pb (II), Cd (II) and Zn (II) using Lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus): kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamics." Chem. Int 2.8 (2016): 89-102.

- Bhardwaj, L.K. , and V. Preprints ( 2023), 2023071691. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.K.; Sharma, S.; Jindal, T. Estimation of Physico-Chemical and Heavy Metals in the Lakes of Grovnes & Broknes Peninsula, Larsemann Hill, East Antarctica. Chem. Afr. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, L.K. , and P. Bharati. “Noise Monitoring and Assessment at Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica”. Indian Journal of Environmental Protection 42, no. 9 (2022): 1027-1033.

- Biswas, N. P. , and A. K. Biswas. "Evaluation of some leaf dusts as grain protectant against rice weevil Sitophilus oryzae (Linn.)." Environment and Ecology 23, no. 3 (2005): 485.

- Boechat, C.L.; Carlos, F.S.; Gianello, C.; Camargo, F.A.d.O. Heavy Metals and Nutrients Uptake by Medicinal Plants Cultivated on Multi-metal Contaminated Soil Samples from an Abandoned Gold Ore Processing Site. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Kunhikrishnan, A.; Thangarajan, R.; Kumpiene, J.; Park, J.; Makino, T.; Kirkham, M.B.; Scheckel, K. Remediation of heavy metal(loid)s contaminated soils – To mobilize or to immobilize? J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 266, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Lesley, and Marc Cohen. Herbs and natural supplements, volume 2: An evidence-based guide. Vol. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015.

- Chand, Sukhmal, et al. "Application of heavy metal rich tannery sludge on sustainable growth, yield and metal accumulation by clarysage (Salvia sclarea L.)." International journal of phytoremediation 17.12 (2015): 1171-1176.

- Chen, B.; Stein, A.F.; Castell, N.; Gonzalez-Castanedo, Y.; de la Campa, A.S.; de la Rosa, J. Modeling and evaluation of urban pollution events of atmospheric heavy metals from a large Cu-smelter. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 539, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. F., T. Y. Yeh, and C. F. Lin. "Phytoextraction of Cu, Zn, and Pb enhanced by chelators with vetiver (Vetiveria zizanioides): hydroponic and pot experiments." International Scholarly Research Notices 2012 (2012).

- Costa, Max. "Review of arsenic toxicity, speciation and polyadenylation of canonical histones." Toxicology and applied pharmacology 375 (2019): 1-4.

- DalCorso, G.; Fasani, E.; Manara, A.; Visioli, G.; Furini, A. Heavy Metal Pollutions: State of the Art and Innovation in Phytoremediation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalvi, Amita A., and Satish A. Bhalerao. "Response of plants towards heavy metal toxicity: an overview of avoidance, tolerance and uptake mechanism." Ann Plant Sci 2, no. 9 (2013): 362-368.

- Farahat, E.; Linderholm, H.W. The effect of long-term wastewater irrigation on accumulation and transfer of heavy metals in Cupressus sempervirens leaves and adjacent soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2015, 512-513, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzadfar, S.; Zarinkamar, F.; Modarres-Sanavy, S.A.M.; Hojati, M. Exogenously applied calcium alleviates cadmium toxicity in Matricaria chamomilla L. plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 20, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, R.; Wei, C.; Tu, S. The roles of selenium in protecting plants against abiotic stresses. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 87, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Gavin, ed. The blackwell companion to hinduism. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Gautam, Meenu, Divya Pandey, and Madhoolika Agrawal. "Phytoremediation of metals using lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf.) grown under different levels of red mud in soil amended with biowastes." International journal of phytoremediation 19.6 (2017): 555-562.

- Gazwi, H.S.; Yassien, E.E.; Hassan, H.M. Mitigation of lead neurotoxicity by the ethanolic extract of Laurus leaf in rats. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 192, 110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunwal, Isha, Lata Singh, and Payal Mago. "Comparison of phytoremediation of cadmium and nickel from contaminated soil by Vetiveria zizanioides L." International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 4.10 (2014): 1-7.

- Hamzah, Amir, Ricky Indri Hapsari, and Erwin Ismu Wisnubroto. "Phytoremediation of cadmium-contaminated agricultural land using indigenous plants." International Journal of Environmental & Agriculture Research 2, no. 1 (2016): 8-14.

- Iqbal, M.; Iqbal, N.; Bhatti, I.A.; Ahmad, N.; Zahid, M. Response surface methodology application in optimization of cadmium adsorption by shoe waste: A good option of waste mitigation by waste. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 88, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.M.; Karthik, C.; Saratale, R.G.; Kumar, S.S.; Prabakar, D.; Kadirvelu, K.; Pugazhendhi, A. Biological approaches to tackle heavy metal pollution: A survey of literature. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Anwarzeb, Sardar Khan, Muhammad Amjad Khan, Zahir Qamar, and Muhammad Waqas. "The uptake and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by food plants, their effects on plants nutrients, and associated health risk: a review." Environmental science and pollution research 22, no. 18 (2015): 13772-13799.

- Koedrith, P.; Kim, H.; Weon, J.-I.; Seo, Y.R. Toxicogenomic approaches for understanding molecular mechanisms of heavy metal mutagenicity and carcinogenicity. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Heal. 2013, 216, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. Y. , et al. "Utilisation of Cymbopogon citratus (lemon grass) as biosorbent for the sequestration of nickel ions from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetic, thermodynamics and mechanism studies." Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 45.4 (2014): 1764-1772.

- Li, J.T.; Liao, B.; Lan, C.Y.; Ye, Z.H.; Baker, A.J.M.; Shu, W.S. Cadmium Tolerance and Accumulation in Cultivars of a High-Biomass Tropical Tree (Averrhoa carambola) and Its Potential for Phytoextraction. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, M.I.; He, Z.-L.; Stoffella, P.J.; Yang, X.-E. Phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soils and water: Progresses and perspectives. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2008, 9, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, A.; Verpoorte, R. Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2011, 34, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, A.; Wang, P.; Ali, A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Lahori, A.H.; Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z. Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 126, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Riffat Naseem, Syed Zahoor Husain, and Ishfaq Nazir. "Heavy metal contamination and accumulation in soil and wild plant species from industrial area of Islamabad, Pakistan." Pak J Bot 42.1 (2010): 291-301.

- Malinowska, E.; Jankowski, K. Copper and zinc concentrations of medicinal herbs and soil surrounding ponds on agricultural land. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 13, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangkoedihardjo, Sarwoko, and Yuli Triastuti. "Vetiver in phytoremediation of mercury polluted soil with the addition of compost." Journal of Applied Sciences Research 7.4 (2011): 465-469.

- Mazumdar, M.; Bellinger, D.C.; Gregas, M.; Abanilla, K.; Bacic, J.; Needleman, H.L. Low-level environmental lead exposure in childhood and adult intellectual function: a follow-up study. Environ. Heal. 2011, 10, 24–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, R.B. Phytoremediation of toxic elemental and organic pollutants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, D.; Luković, J.; Ninkov, J.; Zeremski-Škorić, T.; Zorić, L.; Vasin, J.; Milić, S. Heavy metal content in halophytic plants from inland and maritime saline areas. Open Life Sci. 2012, 7, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradoglu, F.; Gundogdu, M.; Ercisli, S.; Encu, T.; Balta, F.; Jaafar, H.Z.; Zia-Ul-Haq, M. Cadmium toxicity affects chlorophyll a and b content, antioxidant enzyme activities and mineral nutrient accumulation in strawberry. Biol. Res. 2015, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarian, Hassan, Delara Amouzgar, and Hossein Sedghianzadeh. "Effects of different concentrations of cadmium on growth and morphological changes in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.)." Pak. J. Bot 48.3 (2016): 945-952.

- Ng, Chuck Chuan, et al. "Tolerance threshold and phyto-assessment of cadmium and lead in Vetiver grass, Vetiveria zizanioides (Linn.) Nash." Chiang Mai J. Sci 44.4 (2017): 1367-1378.

- Padalia, Rajendra C., and Ram S. Verma. "Comparative volatile oil composition of four Ocimum species from northern India." Natural Product Research 25, no. 6 (2011): 569-575.

- Pandey, Govind, and S. Madhuri. "Heavy metals causing toxicity in animals and fishes." Research Journal of Animal, Veterinary and Fishery Sciences 2, no. 2 (2014): 17-23.

- Pandey, Janhvi, et al. "Palmarosa [Cymbopogon martinii (Roxb.) Wats.] as a putative crop for phytoremediation, in tannery sludge polluted soil." Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 122 (2015): 296-302.

- Pandey, J.; Verma, R.K.; Singh, S. Suitability of aromatic plants for phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated areas: a review. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2019, 21, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantola, R.C.; Alam, A. Potential of Brassicaceae Burnett (Mustard family; Angiosperms) in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals. Int. J. Sci. Res. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, Priyabrata, Pritishova Behera, Debajyoti Das, and Sangram K. Panda. "Ocimum sanctum Linn. A reservoir plant for therapeutic applications: An overview." Pharmacognosy reviews 4, no. 7 (2010): 95.

- Pawar, Shubhangi, and Dinkarrao Amrutrao Patil. Ethnobotany of Jalgaon District, Maharashtra. Daya Books, 2008.

- Peer, Wendy Ann, Ivan R. Baxter, Elizabeth L. Richards, John L. Freeman, and Angus S. Murphy. "Phytoremediation and hyperaccumulator plants." In Molecular biology of metal homeostasis and detoxification, pp. 299-340. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005.

- Pichtel, J. Oil and Gas Production Wastewater: Soil Contamination and Pollution Prevention. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2016, 2016, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazanpour, Hossein. “Study Effect of Soil and Amendments on Phytoremediation of Cadmium (Cd) and Lead (Pb) from Contaminated Soil by Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.)”. Diss. University of Zabol, 2015.

- Rehman, K.; Fatima, F.; Waheed, I.; Akash, M.S.H. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, N.; Saifullah; Malhi, S. S.; Zia, M.H.; Naeem, A.; Bibi, S.; Farid, G. Role of mineral nutrition in minimizing cadmium accumulation by plants. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Arshad, M.; Kaemmerer, M.; Pinelli, E.; Probst, A.; Baque, D.; Pradere, P.; Dumat, C. Long-Term Field Metal Extraction byPelargonium:Phytoextraction Efficiency in Relation to Plant Maturity. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2012, 14, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Mishra, R.K.; Sinam, G.; Mallick, S.; Gupta, A.K. Comparative Evaluation of Metal Phytoremediation Potential of Trees, Grasses, and Flowering Plants from Tannery-Wastewater-Contaminated Soil in Relation with Physicochemical Properties. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2013, 22, 958–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, C. "Heavy Metal Removal from Wastewater Using Ocimum Sanctum." Int. J. Latest Technol. Eng. Manage. Appl. Sci (2017): 85-90.

- Stancheva, I. , et al. "Physiological response of foliar fertilized Matricaria recutita L. grown on industrially polluted soil." Journal of Plant Nutrition 37.12 (2014): 1952-1964.

- Suman, J.; Uhlik, O.; Viktorova, J.; Macek, T. Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals: A Promising Tool for Clean-Up of Polluted Environment? Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, R. Shanmuga, M. Ramanathan, R. Rajesh, B. Satheesh, and Dhandayutham Saravanan. "LC-MS quantification of rosmarinic acid and ursolic acid in the Ocimum sanctum Linn. leaf extract (Holy basil, Tulsi)." Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies 35, no. 5 (2012): 634-650.

- Takahashi, Maria. "A biophysically based framework for examining phytoremediation strategies: optimization of uptake, transport and storage of cadmium in alpine pennycress (Thlaspi caerulescnes)." PhD diss., 2009.

- Tangahu, B.V.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Basri, H.; Idris, M.; Anuar, N.; Mukhlisin, M. Lead (Pb) removal from contaminated water using constructed wetland planted with Scirpus grossus: Optimization using response surface methodology (RSM) and assessment of rhizobacterial addition. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, Y.; Cala, V.; Eymar, E.; Frutos, I.; Gárate, A.; Masaguer, A. Phytoextraction of Cadmium by Four Mediterranean Shrub Species. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2011, 13, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, Sveta, Lakhveer Singh, Zularisam Ab Wahid, Muhammad Faisal Siddiqui, Samson Mekbib Atnaw, and Mohd Fadhil Md Din. "Plant-driven removal of heavy metals from soil: uptake, translocation, tolerance mechanism, challenges, and future perspectives." Environmental monitoring and assessment 188, no. 4 (2016): 1-11.

- Tong, Y.-P.; Kneer, R.; Zhu, Y.-G. Vacuolar compartmentalization: a second-generation approach to engineering plants for phytoremediation. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-T.; Huang, S.-Y.; Cheng, S.-Y. Lead Poisoning Can Be Easily Misdiagnosed as Acute Porphyria and Nonspecific Abdominal Pain. Case Rep. Emerg. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, Van Minh, and Van Khanh Nguyen. "Potential of using vetiver grass to remediate soil contaminated with heavy metals." VNU Journal of Science: Earth and Environmental Sciences 27.3 (2011).

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Liang, C. Closed-loop evaluation on potential of three oil crops in remediation of Cd-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuana, Raymond A., and Felix E. Okieimen. "Heavy metals in contaminated soils: a review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation." International Scholarly Research Notices 2011 (2011).

- Zheljazkov, Valtcho D., and Phil R. Warman. "Phytoavailability and fractionation of copper, manganese, and zinc in soil following application of two composts to four crops." Environmental pollution 131, no. 2 (2004): 187-195.

| S. No. | Classification of the HMs | Name of the HMs | Sources | Health Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Essential (harmless) | Copper (Cu) | Fungicides, paints, pigments, electroplating, & copper polishing | Metabolic activity abnormalities, abdominal disorders |

| 2 | Zinc (Zn) | Dyes, fertilizers, plumbing, oil refining | Gastrointestinal disorders, kidney & liver abnormal functioning | |

| 3 | Iron (Fe) | High intake of iron supplements & oral consumption | Diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dehydration | |

| 4 | Cobalt (Co) | Hip alloy replacement case | Cardiovascular, hepatic, endocrine, hematological | |

| 5 | Non-Essential (toxic) | Arsenic (As) | Paints, pesticides, thermal power plants, fuel burning, smelting operations | Prostate cancer, liver cancer, leukemia, cardiac problems, urinary bladder cancer |

| 6 | Cadmium (Cd) | Fertilizers, batteries, e-waste, electroplating, plastic | Osteo-related problems, prostate cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, renal cancer, gastric cancer | |

| 7 | Chromium (Cr) | Leather tanning, dyes, industrial coolants, textile | Bronchitis cancer, Renal disorders | |

| 8 | Lead (Pb) | Batteries, metal products, petrol additives, ceramics, coal combustion | Alzheimer’s disease, nervous system disorder, lung cancer, carcinoma | |

| 9 | Mercury (Hg) | Instruments, fluorescent lamps, hospital waste, electrical appliances, volcanic eruption, paper industry | Blindness, deafness, gastric problems, renal disorders, Minamata disease, sclerosis, skin cancer, brain cancer, colorectal cancer | |

| 10 | Nickel (Ni) | Alloy, battery industry, mine tailing, thermal power plants | Nasal cavity cancer, lung cancer | |

| 11 | Manganese (Mn) | Fertilizers, steel production, municipal wastewater discharges | Cardiovascular system disorder, central nervous systems disorder, respiratory systems disorder |

| S. No. | HMs | Name of the Plant | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hg | Chrysopogon Zizanioides | Mangkoedihardio and Triastuti, 2011 |

| 2 | Cu, Pb, Sn, Zn | Vetiveria Zizanioides | Vo and Nguyen, 2011 |

| 3 | Cd | Rosmarinus Officinalis | Tapia et. al., 2011 |

| 4 | Cu, Zn, Pb | Vetiveria Zizanioides | Chen et. al., 2012 |

| 5 | Multi metals | Pelargonium Roseum | Shahid et. al., 2012 |

| 6 | Cr | Vetiveria Zizanioides | Sinha et. al., 2013 |

| 7 | Pb, As, Sb, Zn, Cu | Rosmarinus Officinalis | Affholder et. al., 2013 |

| 8 | Pb | Matricaria Chamomilla | Farzadfar et. al., 2013 |

| 9 | Cd, Pb, Zn | Ocimum Basilicum | Stancheva et. al., 2014 |

| 10 | Multi metals | Salvi Officinalis | Stancheva et. al., 2014 |

| 11 | Cd, Ni, As, Pb | Vetiveria Zizanioides | Gunwal et. al., 2014 |

| 12 | Ni | Cymbopogon Citratus | Lee et. al., 2014 |

| 13 | Pb, Cd, Zn | Chrysopogon Zizanioides | Adigun and Are, 2015 |

| 14 | Multi metals | Cymbopogon Martini | Pandey et. al., 2015 |

| 15 | Multi metals | Pelargonium Graveolens | Chand et. al., 2015 |

| 16 | Cd, Zn | Ocimum Basilicum | Akoumianaki-Ioannidou et. al., 2015 |

| 17 | Cd, Pb | Rosmarinus Officinalis | Ramazanpour, 2015 |

| 18 | Multi metals | Salvia Sclarea | Chand et. al., 2015 |

| 19 | Pb, Zn, Cd | Lavandula Vera | Angelova et. al., 2015 |

| 20 | Cd | Ocimum Basilicum | Nazarian et. al., 2016 |

| 21 | Pb, Cd, Zn | Cymbopogon Citratus | Babarinde et. al., 2016 |

| 22 | Multi metals | Mentha Arvensis | Anwar et. al., 2016 |

| 23 | Multi metals | Rosmarinus Officinalis | Boechat et. al., 2016 |

| 24 | Cd, Pb | Vetiveria Zizanioides | Ng et. al., 2017 |

| 25 | Multi metals | Chrysopogon Zizanioides | Gautam et. al., 2017 |

| 26 | Cu, Zn | Mentha Arvensis | Malinowska and Jankowski, 2017 |

| 27 | Cd | Ocimum Basilicum | Alamo-Nole et. al., 2017 |

| 28 | Pb, Cd | Helianthus Annuus | Alaboudi et. al., 2018 |

| 29 | Cd | Virola Surinamensis | Andrade Junior et. al., 2019 |

| 30 | Cd | Glycine Max, Helianthus Annuus | Wang et. al., 2022 |

| 31 | Pb | Scirpus Grossus | Tangahu et. al., 2022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).