Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

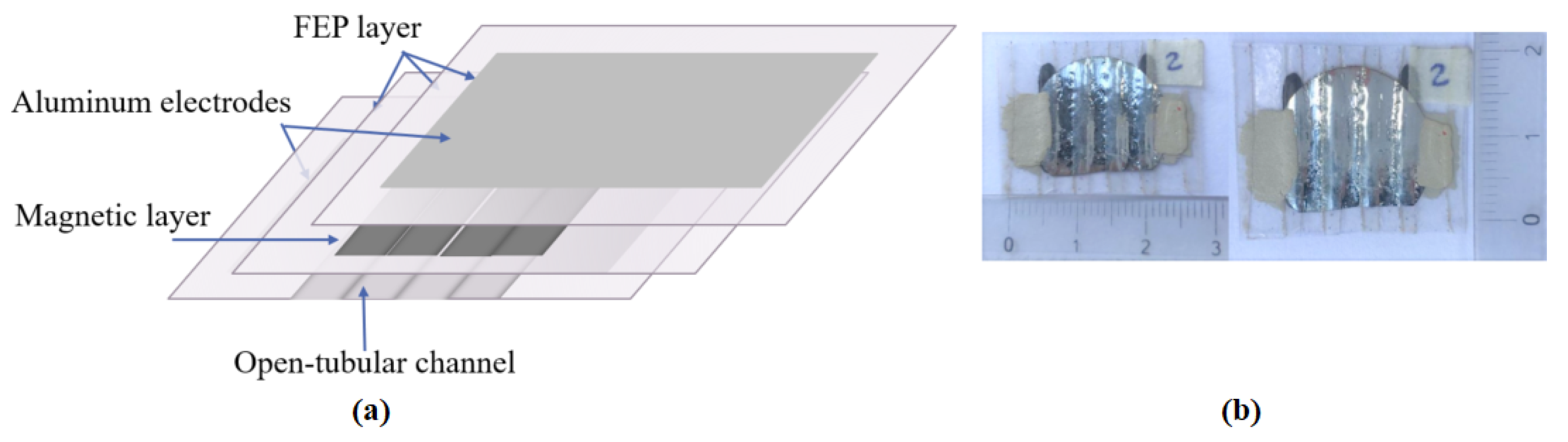

2.1. Materials and Characterization of Magneto-Piezoelectrets Thermoformed (MPTs)

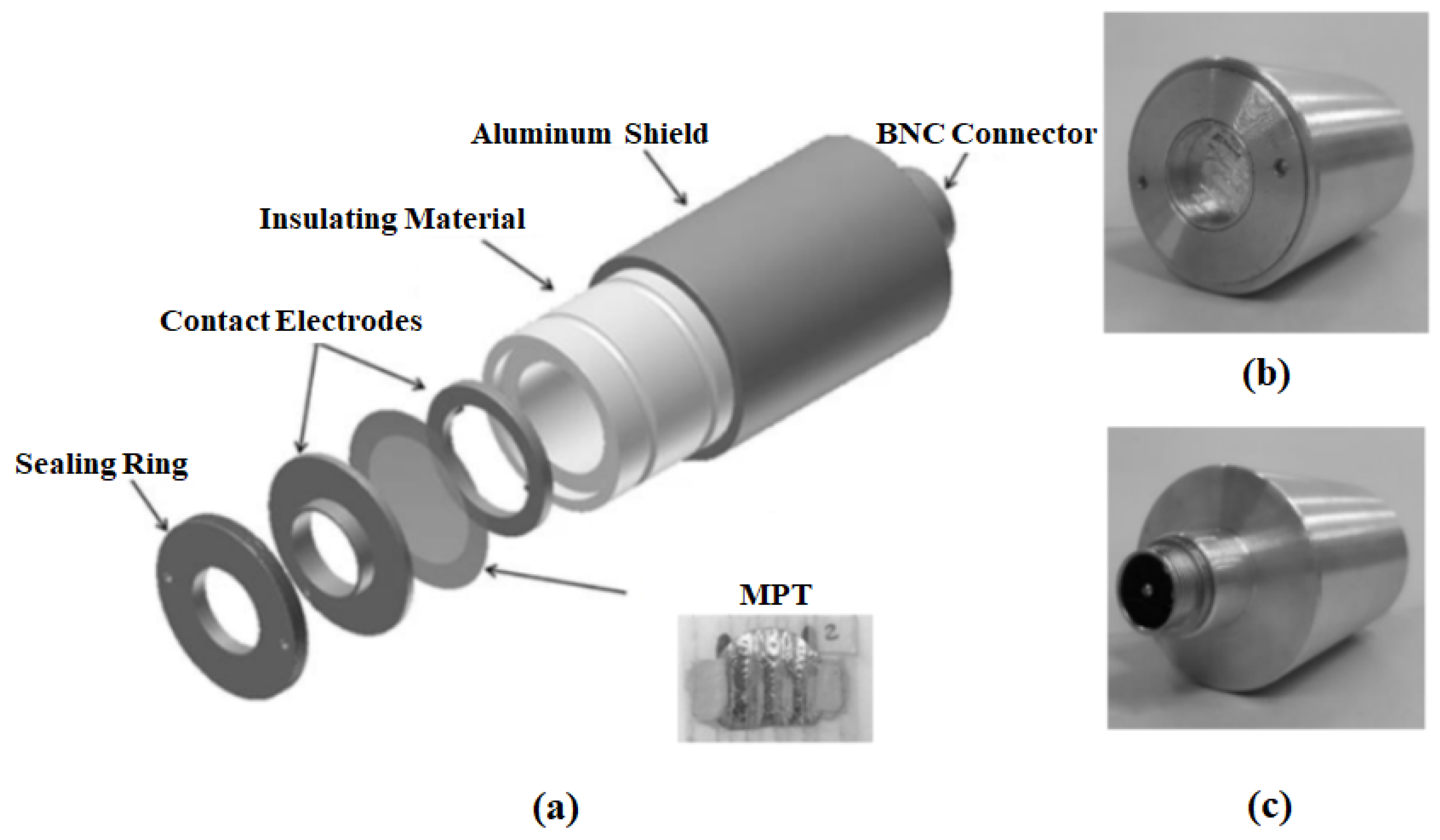

2.2. Assembly of the Current Transducer

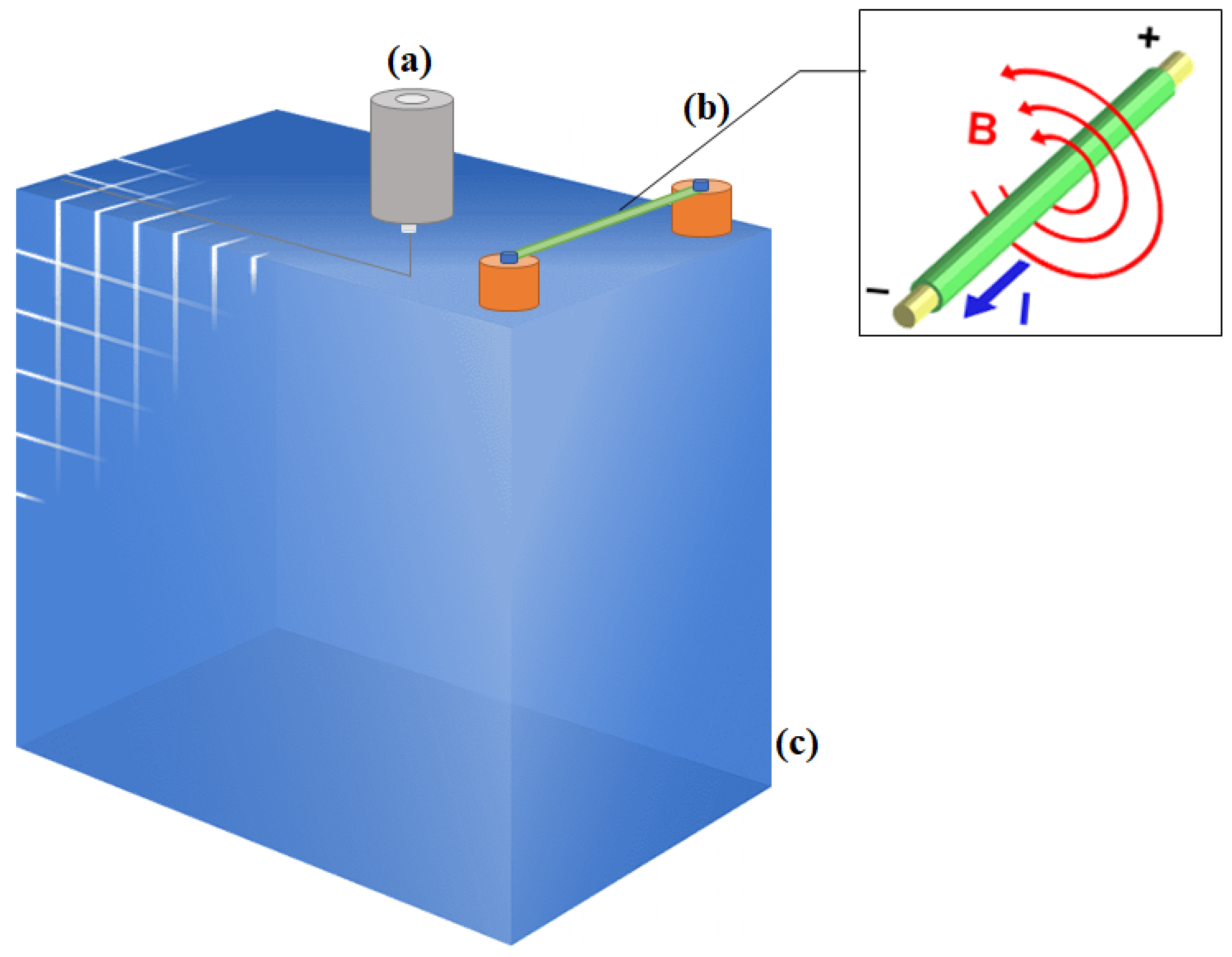

2.3. Sensitivity Test to Electrical Current

3. Results and Discussion

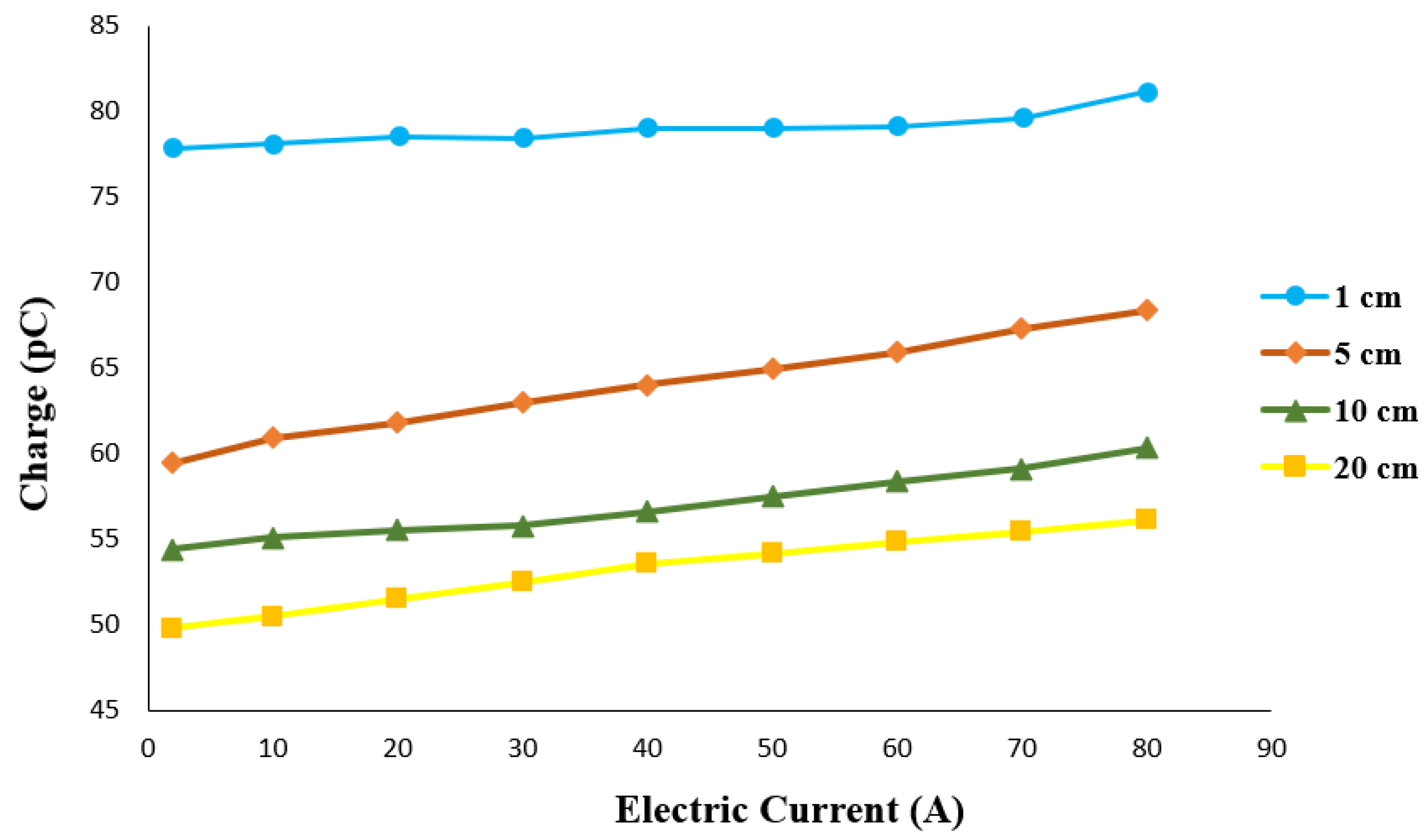

3.1. Measurement Results

3.2. Piezoelectric and Piezo-Magnetic Coeficients

| Electrical Current | Piezoelectric Coefficient | Piezoelectric-magnetic Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| [A] | [pC/N] | [pC/G] |

| 2 | 710,00 | 195,25 |

| 10 | 25,50 | 35,80 |

| 20 | 8,80 | 24,50 |

| 30 | 3,40 | 14,10 |

| 40 | 2,00 | 11,12 |

| 50 | 1,20 | 8,27 |

| 60 | 0,80 | 7,12 |

| 70 | 0,60 | 6,13 |

| 80 | 0,50 | 5,33 |

| Electrical Current | Piezoelectric Coefficient | Piezoelectric-magnetic Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| [A] | [] | [] |

| 2 | 3494,12 | 990,00 |

| 10 | 105,00 | 145,00 |

| 20 | 34,53 | 98,10 |

| 30 | 13,76 | 57,71 |

| 40 | 7,13 | 43,24 |

| 50 | 5,09 | 35,66 |

| 60 | 3,09 | 25,94 |

| 70 | 2,53 | 24,83 |

| 80 | 1,94 | 21,68 |

| Electrical Current | Piezoelectric Coefficient | Piezoelectric-magnetic Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| [A] | [] | [] |

| 2 | 5440,00 | 1360,00 |

| 10 | 229,58 | 324,12 |

| 20 | 60,33 | 168,18 |

| 30 | 27,09 | 113,88 |

| 40 | 13,67 | 76,49 |

| 50 | 8,05 | 56,37 |

| 60 | 6,00 | 50,26 |

| 70 | 4,79 | 46,90 |

| 80 | 3,72 | 42,17 |

| Electrical Current | Piezoelectric Coefficient | Piezoelectric-magnetic Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| [A] | [] | [] |

| 2 | 8300,00 | 4980,00 |

| 10 | 459,09 | 631,25 |

| 20 | 114,44 | 321,88 |

| 30 | 43,03 | 181,03 |

| 40 | 26,49 | 148,61 |

| 50 | 18,40 | 128,81 |

| 60 | 11,46 | 96,14 |

| 70 | 7,75 | 75,89 |

| 80 | 6,35 | 71,01 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, D.N.; Moon, W. Piezoelectric polymer microfiber-based composite for the flexible ultra-sensitive pressure sensor. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ünsal, F.; Altın, Y.; Çelik Bedeloğlu, A. Poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanofiber-based piezoelectric nanogenerators using reduced graphene oxide/polyaniline. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tichý, J.; Erhart, J.; Kittinger, E.; Přívratská, J. Fundamentals of piezoelectric sensorics: Mechanical, dielectric, and thermodynamical properties of piezoelectric materials; 2010. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.C.; Basso, H.C.; Neto, L.G.; Lima, L.; Altafim, R.A.P.; De Aquino, C.V. Piezoelectricity in multi-air voids electrets. In Proceedings of the Annual Report - Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, CEIDP, 2005, Vol. 2005, pp. 669–672. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, F.J.; Altafim, R.A.C.; Assagra, Y.A.O.; Borges, B.H.V.; Altafim, R.A.P. Electric circuit model for simulating ferroelectrets with open-tubular channels. In Proceedings of the Annual Report - Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, CEIDP. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2016, Vol. 2016-December, pp. 315–318. [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, S.; Eder-Goy, D.; Fedosov, S.; Xu, B.X.; Von Seggern, H. Analytical prediction of the piezoelectric d 33 response of fluoropolymer arrays with tubular air channels. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.P. Novos piezoeletretos: desenvolvimento e caracterização. PhD thesis, Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos, Universidade de São Paulo, São Carlos, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.P.; Basso, H.C.; Altafim, R.A.C.; Qiu, X.; Wirges, W.; Gerhard, R. A comparison of polymer piezoelectrets with open and closed tubular channels: Pressure dependence, resonance frequency, and behavior under humidity. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - International Symposium on Electrets, 2011, pp. 213–214. [CrossRef]

- Falconi, D.R.; Altafim, R.A.; Altafim, R.A.; Basso, H.C. Multi-layers fluoroethylenepropylene (FEP) films bounded with adhesive tape to create piezoelectrets with controlled cavities. In Proceedings of the Annual Report - Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, CEIDP, 2011, pp. 137–140. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Z.; Qiu, X.; Wirges, W.; Gerhard, R.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B. Investigation into polarization and piezoelectricity in polymer films with artificial void structure. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - International Symposium on Electrets, 2011, pp. 23–24. [CrossRef]

- Rychkov, D.; Altafim, R.A.P. Template-based fluoroethylenepropylene ferroelectrets with enhanced thermal stability of piezoelectricity. Journal of Applied Physics 2018, 124. [CrossRef]

- Mellinger, A.; Wegener, M.; Wirges, W.; Gerhard-Multhaupt, R. Thermally stable dynamic piezoelectricity in sandwich films of porous and nonporous amorphous fluoropolymer. Applied Physics Letters 2001, 79, 1852–1854. [CrossRef]

- Pukada, E. History and recent progress in piezoelectric polymers. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2000, 47, 1277–1290. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, M.; Wirges, W.; Künstler, W.; Gerhard-Multhaupt, R.; Elling, B.; Pinnow, M.; Danz, R. Coating of porous polytetrafluoroethylene films with other polymers for electret applications. Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP), Annual Report 2001. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.C.; Basso, H.C.; Altafim, R.A.P.; Lima, L.; de Aquino, C.V.; Neto, L.G.; Gerhard-Multhaupt, R. Piezoelectrets from thermo-formed bubble structures of fluoropolymer-electret films. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2006, 13, 979–985. [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Wirges, W.; Gerhard, R.; Zirkel, L. Charging conditions for cellular-polymer ferroelectrets with enhanced thermal stability. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - International Symposium on Electrets, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.P.; Altafim, R.A.C.; Qiu, X.; Raabe, S.; Wirges, W.; Basso, H.C.; Gerhard, R. Fluoropolymer piezoelectrets with tubular channels: Resonance behavior controlled by channel geometry. Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing 2012, 107, 965–970. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.P.; Altafim, R.A.C.; Basso, H.C.; Qiu, X.; Wirges, W.; Gerhard, R. Fluoroethylenepropylene ferroelectrets with superimposed multi-layer tubular void channels. In Proceedings of the Annual Report - Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena, CEIDP, 2011, pp. 133–136. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.M.; Bichurin, M.I.; Yang, S.C. Hydrothermal synthesis of Bi-magnetic clusters for magnetoelectric composites. Materials Research Bulletin 2017, 91, 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.W. Magnetoelectric effect in composites of piezoelectric and piezomagnetic phases. Physical Review B 1994. [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Wen, X.; Deng, Q.; Shen, S.; Liu, L.; Sharma, P. Soft rubber as a magnetoelectric material—Generating electricity from the remote action of a magnetic field. Materials Today 2021, 43. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Nan, C.W. Recent progress in multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: From bulk to thin films. Advanced Materials 2011, 23, 1062–1087. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.S.; Bhatnagar, C.S. Calculation of an equivalent electric field from thermally stimulated discharge current of perspex magneto-electrets. Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics 1979, 17, 575–582.

- Altafim, R.A.P.; Assagra, Y.A.O.; Altafim, R.A.C.; Carmo, J.P.; Palitó, T.T.C.; Santos, A.M.; Rychkov, D. Piezoelectric-magnetic behavior of ferroelectrets coated with magnetic layer. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 119. [CrossRef]

- Altafim, R.A.P.; Altafim, R.A.C. History and recent progress in ferroelectrets produced in Brazil. Journal of Advanced Dielectrics 2023, p. 2341007. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. An Introduction to the Theory of Piezoelectricity; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lin, D.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Xu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liao, X.; Chen, L.Q.; et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectricity in ferroelectric ceramics by design. Nature Materials 2018. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).