1. Introduction

The term “endometriosis” was introduced to the literature by Sampson in 1927, based on the description of endometrial tissue in the myometrium by Rokitansky and in the rectovaginal septum by Cullen, who referred to this entity as adenomyoma and “hemorrhagic (chocolate) cysts in the ovaries.” Endometriosis is an inflammatory, chronic, benign, and estrogen-dependent disease that affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age and 35-50% of women with dysmenorrhea and infertility(1). The definition of endometriosis is histological and requires the identification of glands and stroma outside the uterus. These ectopic lesions are frequently found in the pelvic organs and peritoneum. Occasionally, they can be found in other parts of the body such as the kidneys, bladder, lungs, and even in the brain(2).

Endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial tissue, composed of glandular epithelium and stroma, is found in anatomical sites outside the uterine cavity. The etiology, in most cases, is explained by the theory that the endometrium implants in the peritoneal cavity as a result of retrograde flow from the uterus to the uterine tubes. However, many diagnostic problems can arise due to abnormalities or absence of either glandular or stromal components, as well as scant tissue in very small biopsies. The microscopic appearance of both the glandular component and the stromal component can be affected, respectively, by hormonal changes, metaplastic changes, cytological atypia, hyperplasia, foamy or pigmented histiocytic infiltrate, fibrosis, elastosis, smooth muscle cell metaplasia, myxoid change, and decidual change. For these reasons, the histological diagnosis of endometriosis can be a challenge for the pathologist when any of the components show changes microscopically or when it involves unusual anatomical sites. In the case of myxoid changes, if the pathologist is not familiar with the entity, it can easily be confused with mucinous malignancies.

Myxoid endometriosis is a rare entity that is part of the histological changes that can occur in endometriosis. It is extremely important that the pathologist has knowledge of the histological guidelines for the morphological recognition of this entity, as well as the histochemical and immunohistochemical techniques that will support the diagnosis.

2. Material and Methods

The study is described as a retrospective, observational, cross-sectional, and descriptive study. Pathology reports with a diagnosis of endometriosis were obtained from the pathology files of two medical institutions: Hospital General de México “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” and UMAE Hospital de Especialidades N° 1 Centro Médico Nacional Bajío, affiliated with the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. The study covered a period of 6 years, from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2021.

The inclusion criteria consisted of all cases with a complete histopathological report diagnosing endometriosis and accompanied by paraffin blocks and slides. Incomplete cases lacking paraffin blocks or slides or cases with issues in the histological technique procedure were excluded. Only cases that met the histological criteria for myxoid endometriosis, characterized by the presence of extracellular matrix with myxoid change, were included in the study.

For each selected case, a paraffin block was chosen, and special histochemical techniques were performed. These techniques included periodic acid-Schiff staining (PAS) and Alcian blue staining (AA). Positive staining for myxoid matrix and intracellular mucoid component was assessed. Additionally, immunohistochemical reactions were conducted for stromal cells (using CD10 antibody, Biocare®, 1:100 dilution) and hormone receptors (estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR) using Diagnostic Biosystem® antibodies, both at 1:50 dilution). CD10 positivity was determined based on membranous expression, and for hormone receptors, nuclear expression with any intensity was considered (H-SCORE).

The data collected from these analyses was used to create a database in Excel. Descriptive statistics will be employed to determine percentages and frequencies, and the SPSS 21 (IBM©) program will be used for the statistical analysis.

3. Results

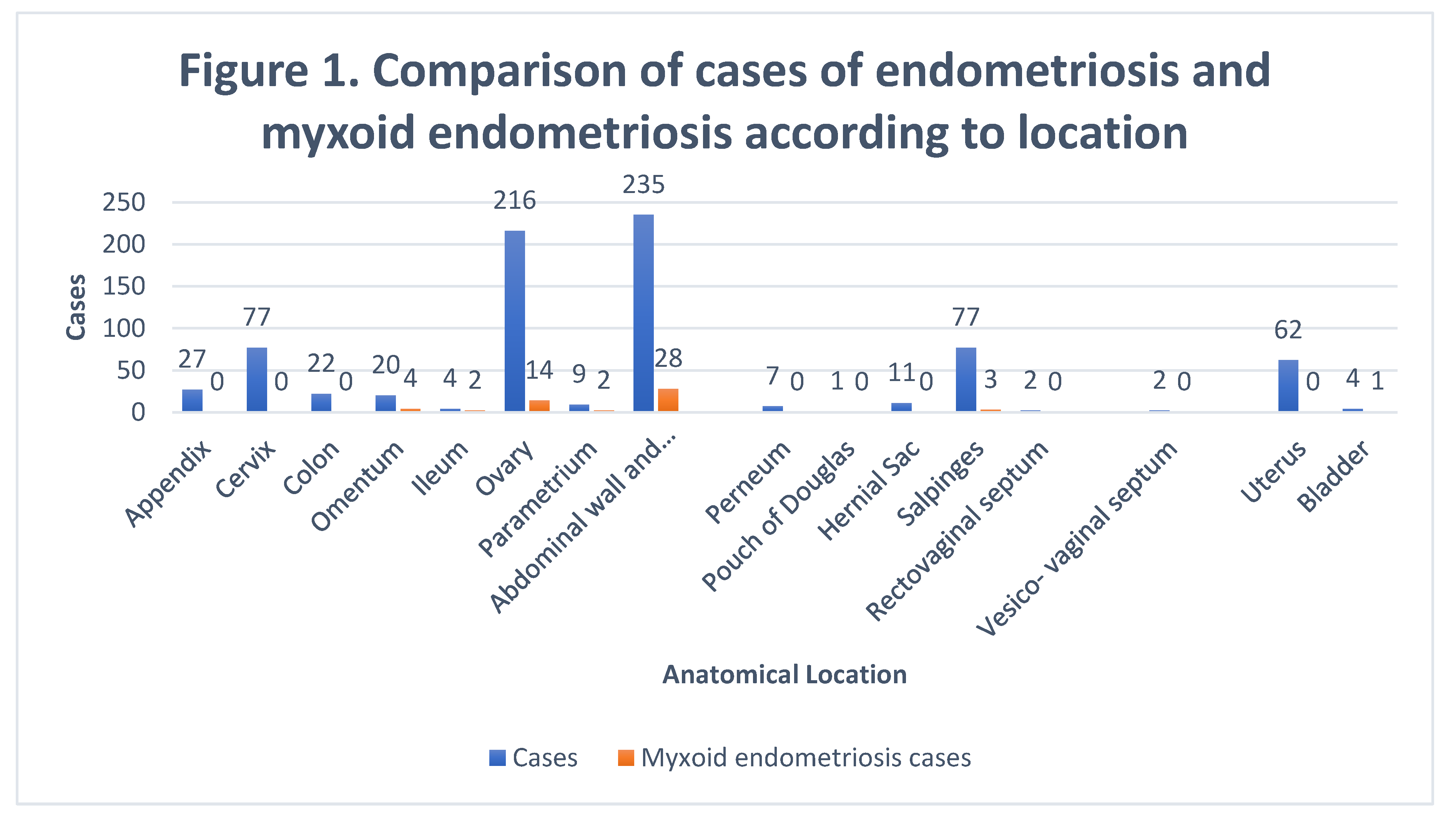

776 cases of endometriosis were collected between the two institutions participating in the study, in different anatomical sites (

Table 1,

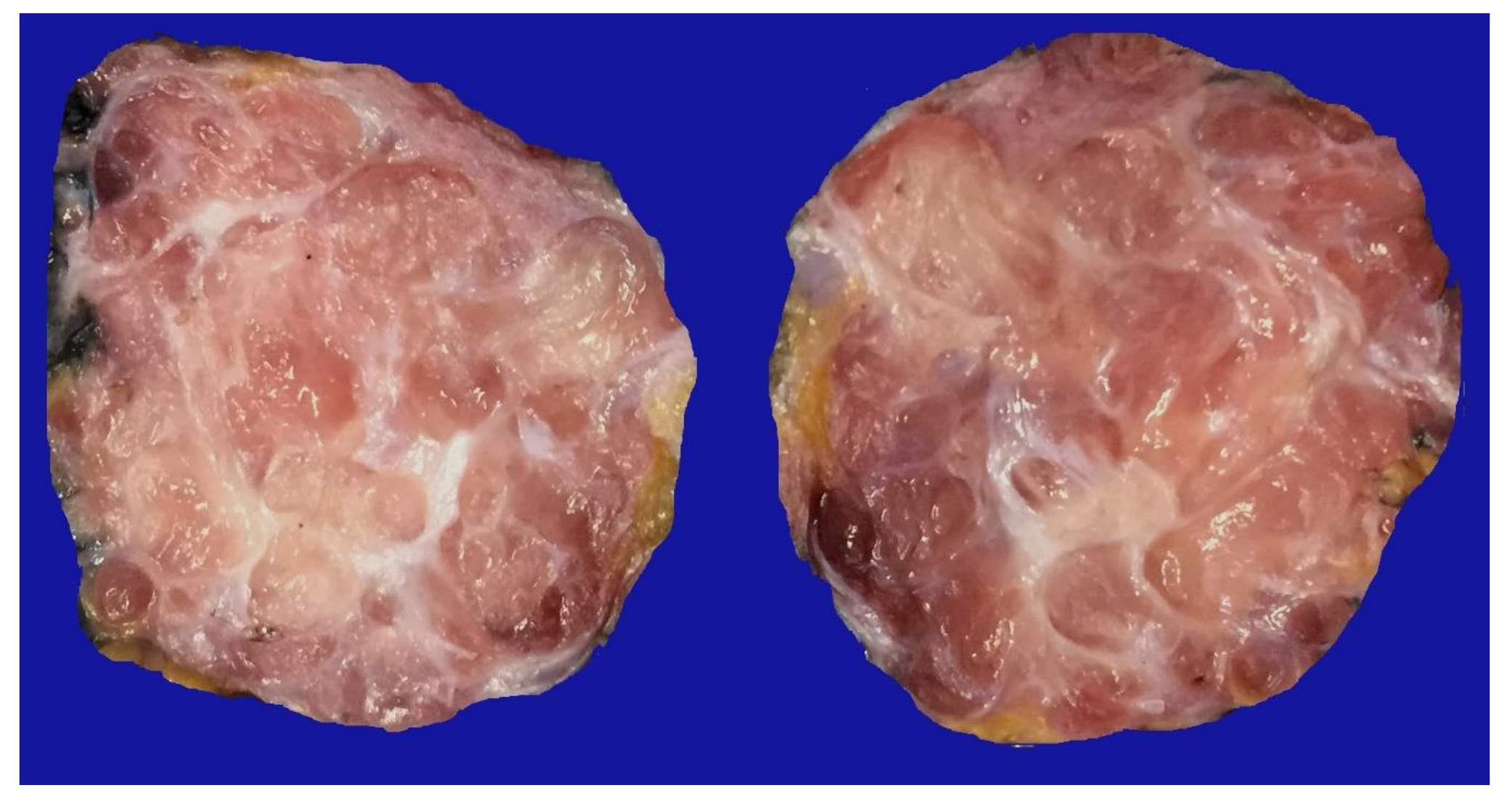

Figure 1), in which 54 of them presented a myxoid stroma greater than 50% with respect to the cellularity of the samples. and that represent 6.95% of the total endometriosis examined with the following locations: omentum (4/20), ileum (2/4), ovary (14/216), parametria (2/9), soft tissues (28/235), salpingus (3/77), bladder (1/4). The clinical records of these patients were consulted and the common denominator was that the women were in the surgical (41/57) or physiological (7/39) puerperium in a period of time from 24 hours postpartum to six months after said event. Macroscopically, two different lesions were observed: the first one, which is the most frequent, presents as a non-encapsulated lesion with pushing edges of a fibromyxoid appearance; the second and less frequent, a well-defined lesion, partially or totally encapsulated, the cut surface is shiny, gelatinous in appearance, multilobed, light brown to brown in color with focal areas of recent and old hemorrhage, these lobes are separated by fibrous septa (

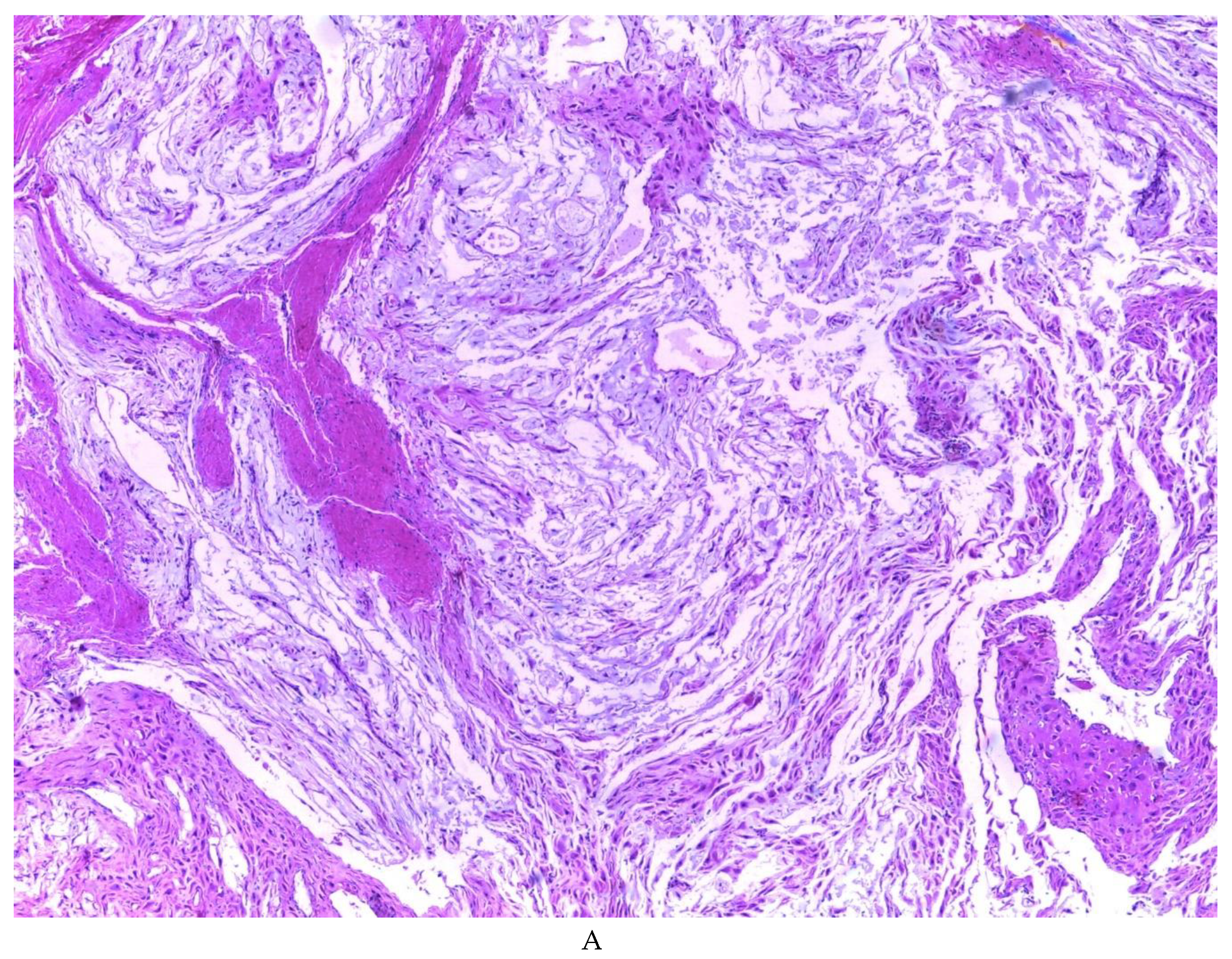

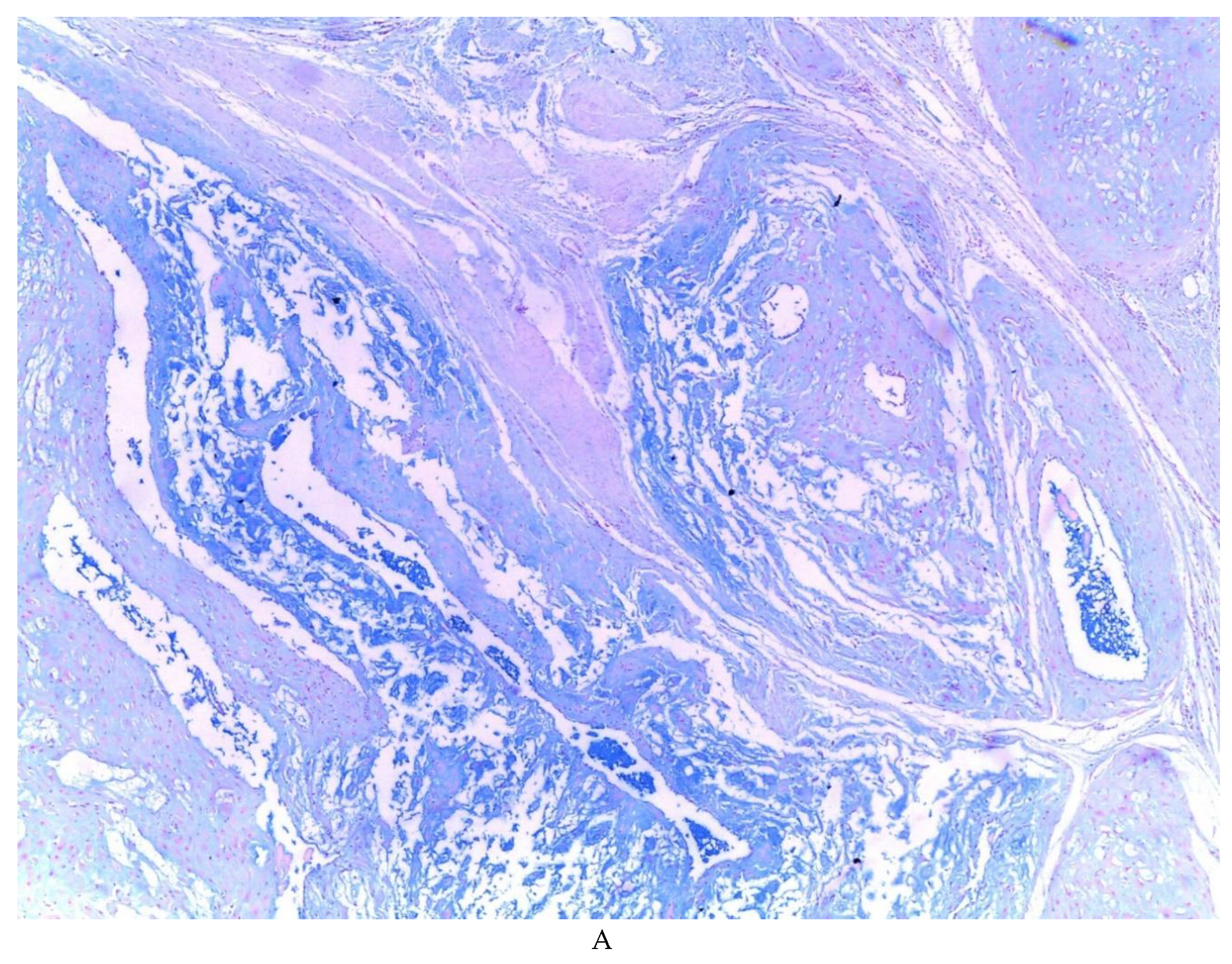

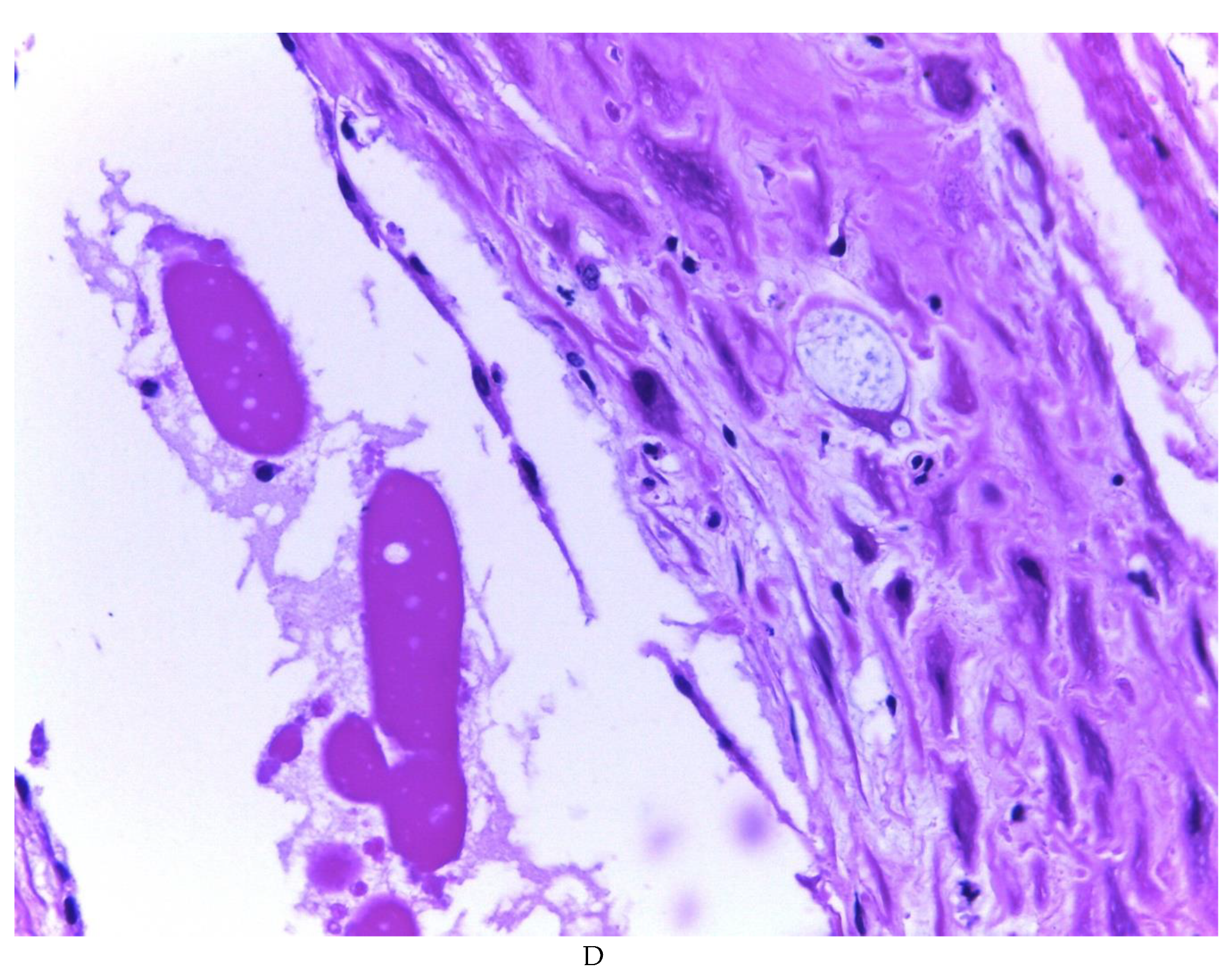

Figure 2). Histologically, it was found in all the samples evaluated at least 50% of myxoid stroma with some fine connective tissue septa with proliferation of stromal cells (

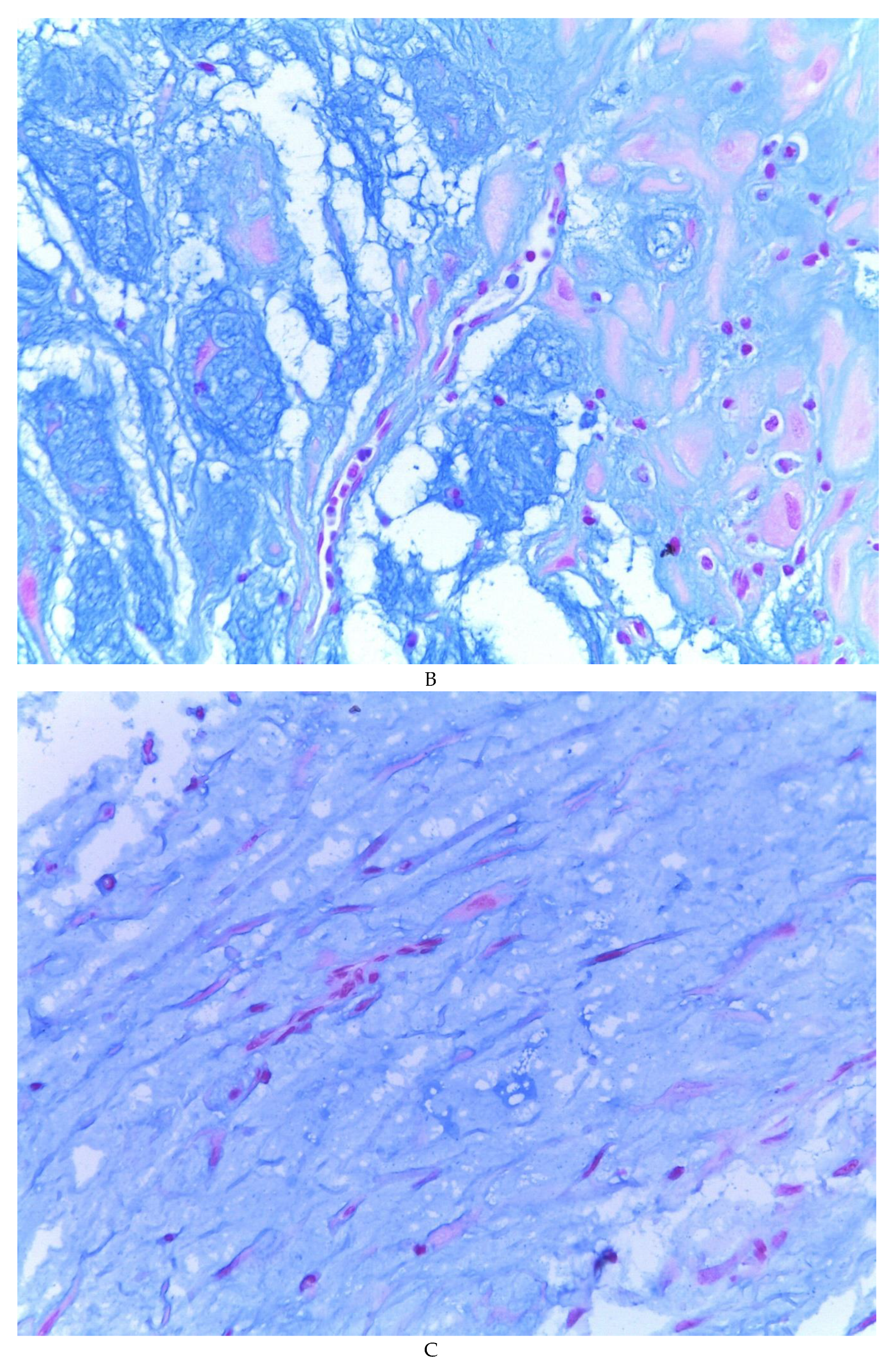

Figure 3A), which present four variants in their shape: (1) Epithelioid stromal cells of wide eosinophilic cytoplasm with round nucleus with small nucleolus (

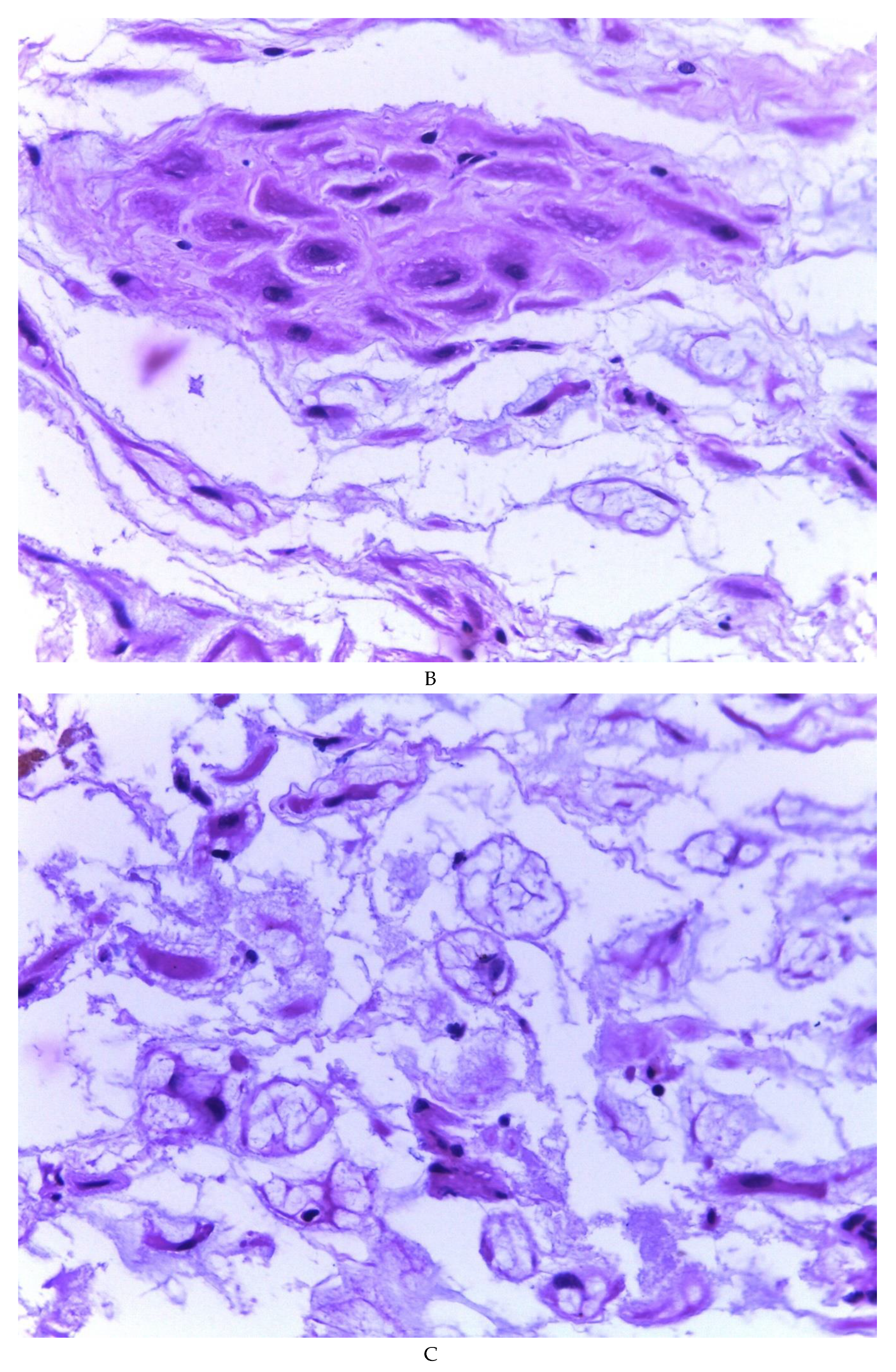

Figure 3B), (2) Pseudolipoblast-type stromal cells with moderate cytoplasm, multivacuolated in their cytoplasm that can present eosinophils or be clear cytoplasm, with central nuclei of granular chromatin (

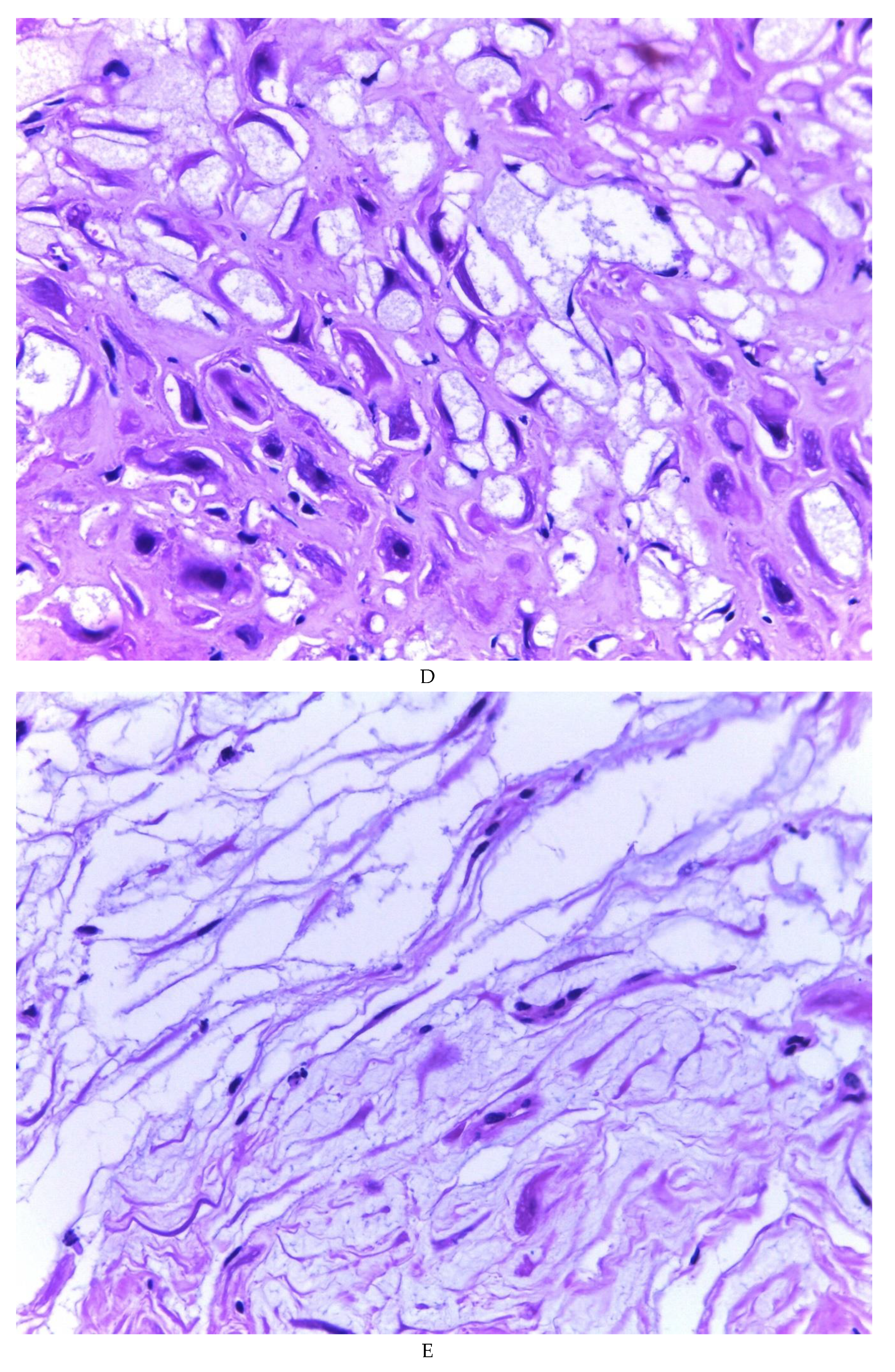

Figure 3C), (3) “pseudosignet ring” stromal cells with nucleus and cytoplasm rejected to the periphery giving the aforementioned appearance (

Figure 3D) and (4) immersed spindle cells with small nucleus and barely visible nucleolus (

Figure 3E); Among these cells, the epithelial component is observed, which is forming tubules that vary in diameter, ranging from small tubules and large cystic dilations of the gland that presents a layer of low cubic to cylindrical epithelium, generally with an atrophic appearance (

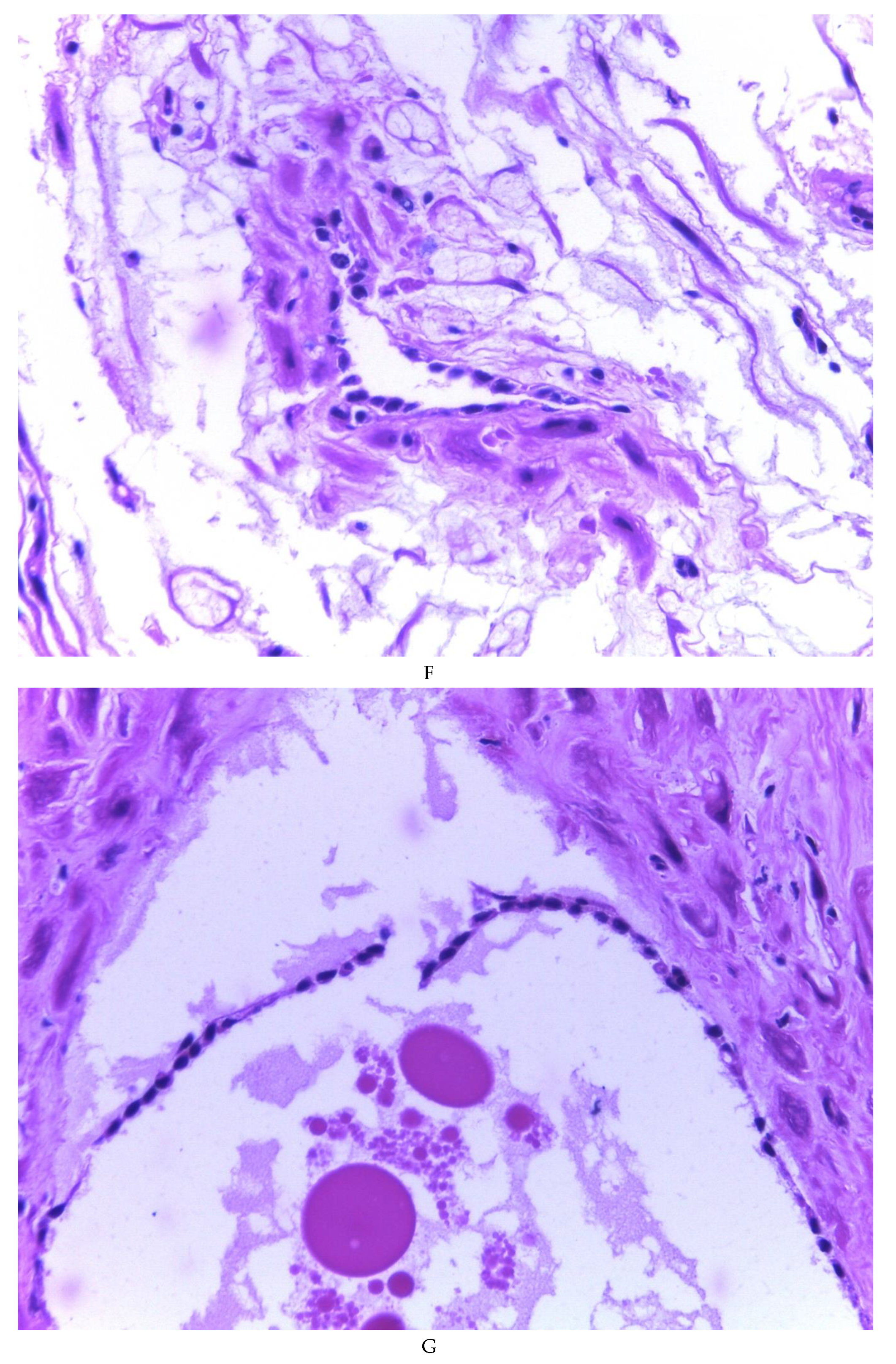

Figure 3F). Hyaline globules were found in the glandular lumens (

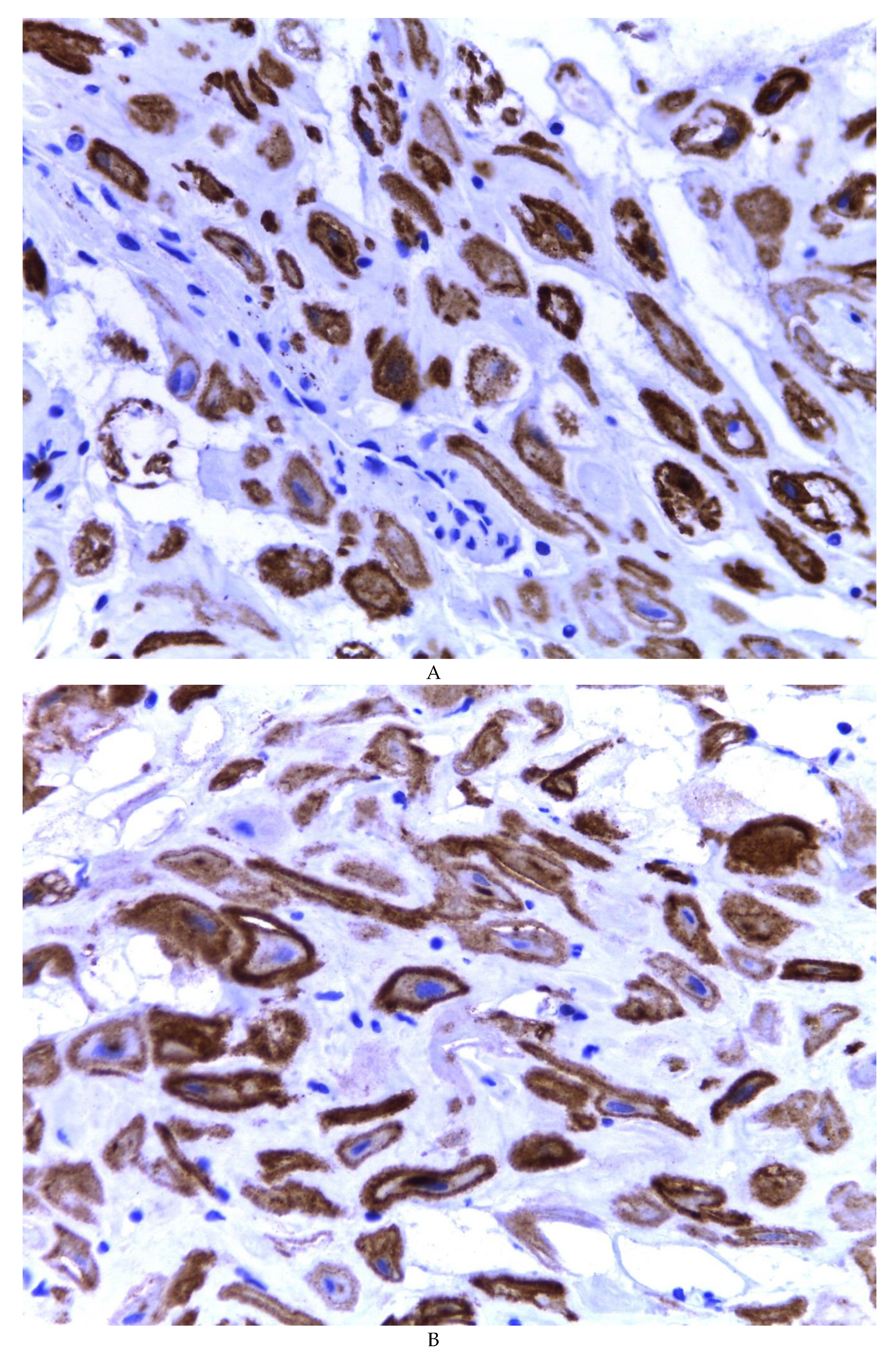

Figure 3G). The extracellular matrix showed a composition by glusocaminoglycans evidenced in 100% of the cases by staining present for AA (

Figure 4A–C), but without staining for PAS; however, the latter stained on proteinaceous globular material in the lumen of the endometrial glands (

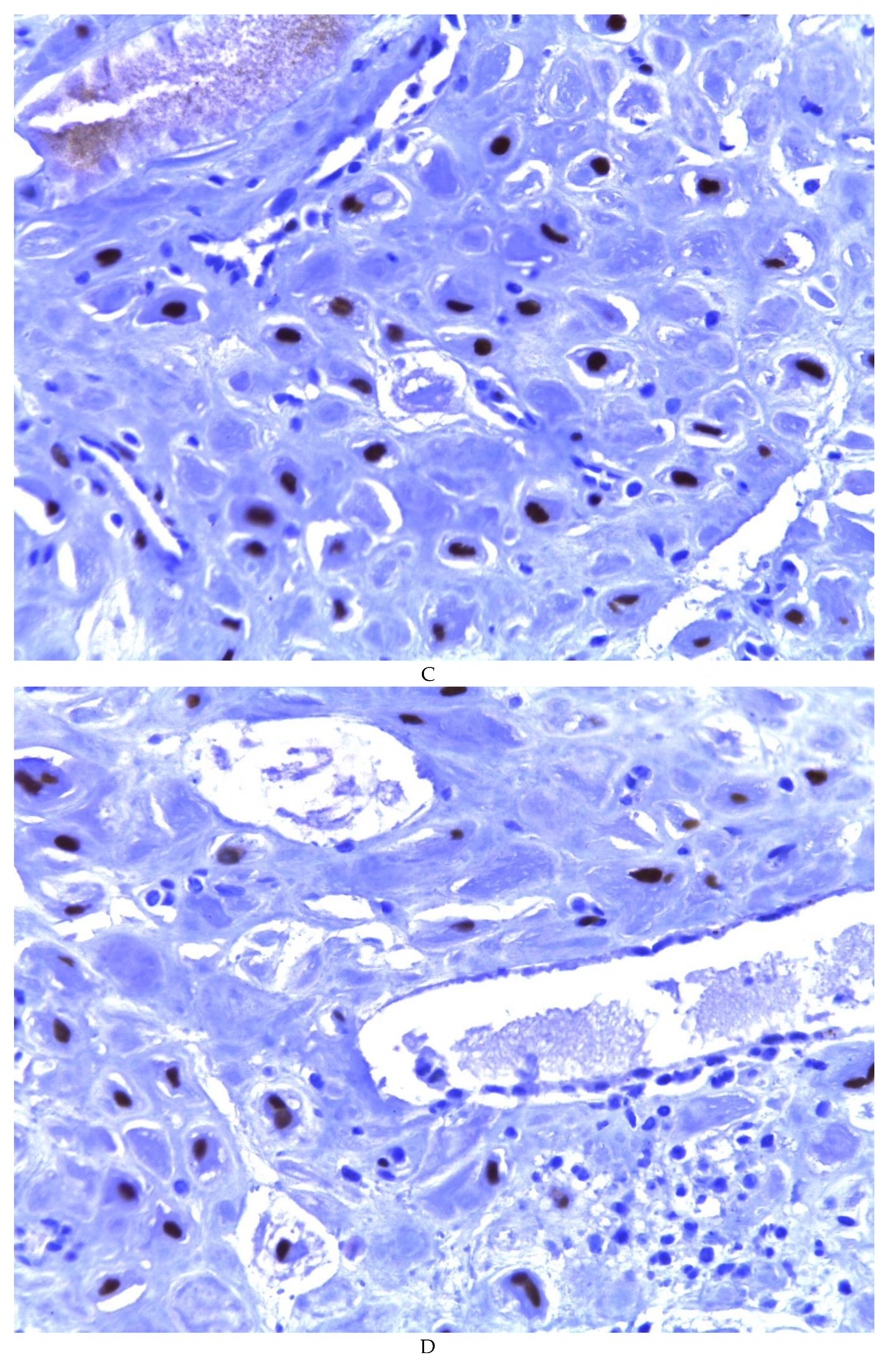

Figure 4D). Immunohistochemistry for CD10 was positive in 100% of the stromal cells with a mild to moderate reaction in the cytoplasm and membrane with a decidual appearance (

Figure 5A,B). The ER and PR showed nuclear expression in 100% of the cases, with greater intensity in the ER (

Figure 5C) than in the RP (

Figure 5D); both hormone receptors were expressed on endometrial epithelial cells as well as on stromal cells. The cases of myxoid endometriosis examined did not present cytological atypia suggesting any precursor lesion of epithelial or stromal origin.

4. Discussion

4.1. General aspects about endometriosis

Endometriosis is a complex and enigmatic disease with an uncertain etiology. Several theories attempt to explain its histogenesis, but the exact cause remains unknown. The establishment of an endometriotic implant requires specific conditions, including the presence of ectopic glands and stroma, adhesion of endometrial cells to the peritoneum, invasion of the mesothelium, and maintenance and growth of ectopic tissue. These features share similarities with processes seen in neoplasms and involve various biological reactions. It is likely that both intrinsic factors within the ectopic endometrium and immunological alterations in the host play crucial roles in the development of endometriosis(3). The retrograde theory, the oldest among the proposed explanations, suggests that endometriosis occurs due to the retrograde flow of endometrial cells and detached debris passing through the uterine tubes into the pelvic cavity during menstruation(1,4). Another theory, the metaplastic theory, proposes that endometriosis arises from metaplasia of specialized cells in the mesothelium of the visceral and abdominal peritoneum. This theory suggests that hormonal and immunological factors stimulate the transformation of normal cells and tissues in the peritoneum into endometrial-like tissue, which may explain the incidence of endometriosis in prepubertal girls. However, it is worth noting that the estrogen stimulus would not be present in these patients, making this condition potentially distinct from endometriosis occurring in women of reproductive age. Evidence of ectopic endometrial tissue in female fetuses further supports the theory that endometriosis results from defects in embryogenesis, with residual embryological cells from the Wolffian or Müllerian ducts persisting and evolving into endometriotic lesions that respond to estrogen stimulation. Some authors have also proposed endogenous, biochemical, and immunological factors as potential causes, acting as inducers of differentiation in ectopic endometriotic tissue(1). The support for the theory of a non-endometrial origin of endometriosis arises from histologically confirmed clinical cases in patients without menstrual endometrium, such as patients with Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome and men diagnosed with prostatic carcinoma who are undergoing treatment with doses high estrogen(5).

Genetic factors have been implicated in the development of endometriosis, supported by familial case reports, a higher risk of endometriosis in patients with affected first-degree relatives, and the observation of concordance of endometriosis in twins. Numerous studies have identified genetic polymorphisms as contributing factors to the development of endometriosis. The disease appears to have a polygenetic mode of inheritance, involving multiple loci and chromosomal regions associated with specific endometriosis phenotypes. Both inherited and acquired genetic factors may predispose women to have an impaired response to discard endometrial tissue that adheres to the peritoneal epithelium. Genes related to detoxification enzymes, estrogen receptor polymorphisms, and genes of the innate immune system are among those implicated in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Additionally, epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation, demethylation, and modifications in the histone code may also contribute to the development of the disease(1,5). (See

Table 2 for a summary of these aspects).

4.2. Myxoid change

The term “myxoid” was introduced by Rudolph Virchow in 1858 to describe soft tissue tumors that resembled the structure of the umbilical cord. The concept of myxoid tumors led to the recognition of various new tumors, including myxadenoma, myxochondroma, myxofibroma, and myxoneuroma. Today, myxoid changes or areas are identified in both benign and malignant neoplasms, as well as in non-neoplastic (reactive) lesions(6). Advancements in the study of the myxoid extracellular matrix came with the introduction of alcian blue histochemical staining in 1950, which allowed the distinction between different glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in tissues. GAGs are macromolecules present in the pericellular and extracellular matrix, and they form proteoglycans once covalently attached to specific nuclear proteins(7).

From a biochemical perspective, the term “myxoid” encompasses various proteins and other macromolecules with different functions. When encountering a myxoid lesion, an accurate diagnosis primarily relies on careful histopathological evaluation based on routine criteria such as tumor demarcation, growth pattern, vascular pattern, and nuclear atypia. Immunohistochemistry may be useful for differential diagnosis in certain cases, but it is not always decisive. In instances of diagnostic difficulty, molecular cytogenetics plays a crucial role. Beyond its academic significance, understanding the role of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans in the biology of myxoid lesions is essential, as the myxoid morphology of the extracellular matrix can be found in non-neoplastic reactive processes, benign, and malignant tumors alike(6).

4.3. Myxoid changes in uterus

Myxoid lesions occurring in the uterus are rare, and most of them represent smooth muscle myxoid tumors, either benign or malignant, as well as a variant of endometrial stromal neoplasia. While some uterine lesions are characterized by a myxoid stroma as a defining feature, myxoid changes may also arise due to degenerative processes or be associated with the use of medications, such as progestogens or progestins. Progestogens are synthetic analogues of progesterone commonly used in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding, endometriosis, contraception, and as protection for patients undergoing tamoxifen treatment. Patients using these medications may exhibit morphological changes in the endometrial stroma, such as patchy edema with intercellular vacuolation, deciduization, hemorrhage, and myxoid change in the stroma. Pathologists need to be aware of these morphological characteristics associated with progestogen use to avoid misdiagnosis(6,8).

Occasionally, the endometrial stroma can undergo marked myxoid change, with the stromal cells separated by acellular mucin, sometimes forming “lakes” of mucin. The mucin in these cases is stromal, not epithelial, and stains positively with toluidine blue or alcian blue (pH 2.5) but not with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Some cases have occurred during pregnancy or puerperium, suggesting a potential association with the hormonal environment. The presence of marked decidual transformation of the endometriotic stroma may further complicate the histological interpretation in pregnant patients(7,8). Awareness of these changes and the presence of endometrial glands, even if occasionally atrophic, can aid in the correct diagnosis.

Endometriosis with myxoid change in the stroma is rare and not commonly known among histopathologists, as it is not extensively described in pathology texts. Less than ten cases of endometriosis with myxoid change have been reported, with some of them exhibiting histological similarity to metastatic adenocarcinoma, pseudomyxoma peritonei, and even signet-ring cell carcinoma-like features(4).

4.4. Diagnostic problems in endometriosis

Many diagnostic problems can arise as a result of alterations or absence of any of the components, glandular or stromal, as well as scant tissue in very small biopsies. The microscopic appearance of the glandular component can be affected by hormonal changes, metaplastic changes, cytologic atypia, and hyperplasia. In some cases, the endometriotic glands are scattered or even absent (stromal endometriosis). Regarding the stromal component, it can be obscured by foamy or pigmented histiocytic infiltrate, fibrosis, elastosis, smooth muscle cell metaplasia, myxoid change, and decidual change. The histological diagnosis of endometriosis can also be challenging for the pathologist when it involves rare anatomical sites, considering the five most problematic sites such as the ovary, cervix, vagina, uterine tubes, and intestine, including the important distinction between an endometrioid carcinoma arising from colonic endometriosis from a primary colonic adenocarcinoma(4,9).

Usually, the histological diagnosis of endometriosis is simple and is based on the typical presence of both components, endometriotic glands and stroma, although it can be diagnosed when only one of the components is present. Like normal and neoplastic endometrial stroma, endometriotic stromal cells are immunoreactive for CD10, which may aid diagnosis in problem situations such as sparse tissue or absence of the glandular component.

It is important to define two concepts that can also generate diagnostic problems:

Atypical endometrioid-type endometriosis: It is a lesion with intermediate characteristics between endometriosis and endometrioid-type adenocarcinoma. It may resemble an epithelial endometrial neoplasm of the endometrium by having prominent architecture, increased glandular density, and various degrees of nuclear atypia. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis shows loss of function of PTEN (21%), KRAS (20%), β-catenin (25%), and PIK3CA (46%).

Atypical endometriosis of the clear cell type: It has cells with nuclear atypia and vacuolated or foamy cytoplasm and is a precursor lesion of clear cell adenocarcinoma. Atypical epithelium may be exfoliative, “studded,” or flattened. There may be complex glandular formations of exophytic epithelium and dense aggregates. It has been shown to have mutations in PIK3CA and loss of the ARID1A protein as in clear cell carcinoma. Diagnosis requires the presence of marked nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia.

In practice, the distinction between them is not easy since they tend to overlap and show a great histological variety. Atypical histology of both endometrioid and clear cell types of endometriosis often becomes apparent only when the disease has progressed to carcinoma. Another complication is that, to some degree, it is common for cells to show frank atypia, exfoliation, and cell translocation in areas showing degenerative changes(9).

Table 3.

Findings in endometriosis associated with diagnostic pitfalls.

Table 3.

Findings in endometriosis associated with diagnostic pitfalls.

A) Alterations in the stromal component:

- Foamy or pigmented histiocytes

- Fibrosis

- Elastosis

- Smooth muscle metaplasia

- Myxoid change

- Decidual change, including the presence of signet-ring cells |

B) Alterations in the glandular component:

- Postmenopausal changes and changes related to hormonal treatment

- Changes related to pregnancy

- Metaplastic changes

- Cytological atypia

- Hyperplasia

- Absence of glands (stromal endometriosis) |

C) Apparently neoplastic findings:

- Pseudoxanthomatous necrotic nodules

- Polypoid endometriosis

- Vascular invasion

- Perineural invasion |

D) Unusual reactive and inflammatory changes:

- Infected endometriotic cysts

- Pseudoxanthomatous salpingitis

- Florid mesothelial hyperplasia

- Liesegang rings |

E) Diagnostic problems related to the anatomical site:

- Endometriosis on or near the ovarian surface

- Superficial endometriosis of the cervix

- Vaginal endometriosis

- Tubal endometriosis

- Intestinal endometriosis |

F) Rare associated injuries:

- Peritoneal leiomyomatosis

- Gliomatosis peritonei |

4.5. Diagnostic problems related to the endometrial stromal component

Microscopic alterations in the typical appearance of endometriosis that can cause problems in its diagnosis occur in both the glandular and stromal components, with the latter being more common. Although these changes can mask the typical stromal component, their presence should increase the diagnostic suspicion of the endometrial origin of the lesion. In these cases, the endometrial stroma, if present at all, may be very subtle and confined to a faint or discontinuous periglandular area or delineating an endometriotic cyst. In the latter case, if the epithelial cells are denuded, the stromal cells may be found resting directly on the cyst lumen. If the stromal origin of the cells is in doubt, immunohistochemical reactions with CD10(4) can be used.

4.6. Differential diagnoses

4.6.1. Myxoid liposarcoma

The myxoid histological variant corresponds to 15-20% of all liposarcomas. It is more common in young patients with a peak incidence between the fourth and fifth decades of life. It arises mainly from the soft tissues in the extremities, with uncommon anatomical features including the head, neck, subcutaneous tissue, and thorax.

Histologically, they show a uniform mixture of oval cells and signet-ring cells corresponding to lipoblasts on a background of myxoid stroma and a very prominent arborizing capillary vasculature(10).

4.6.2. Myxoid chondrosarcoma

Myxoid chondrosarcoma is a rare tumor that corresponds to 2.5% of all soft tissue tumors. It was first described by Enzinger and Shiraki in 1972 and mainly affects middle-aged men, manifesting as a painless, slow-growing tumor. The frequently affected anatomical sites are the extremities, but it can also affect the neck, orbit, and peritoneum. Grossly, it is a well-circumscribed, pseudoencapsulated, lobulated, light-brown to gray tumor with a shiny, whitish-grey to light-brown surface on section, containing mucoid material and may present with cystic or hemorrhagic degeneration. The microscopic study reveals a multilobulated neoplasm made up of polygonal to spindle-shaped malignant cells, forming nests and cords on a myxoid matrix, separated by fibrous septa. Despite being cartilaginous in nature, it is strongly immunoreactive for vimentin and variable for S-100(11).

4.6.3. Myxofibrosarcoma

Formerly known as myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma, it is considered one of the most common fibroblastic sarcomas in the elderly, mainly affecting patients between 60 and 80 years of age. It is a unique subtype of soft tissue tumors, characterized by a diffuse infiltrating pattern. It represents approximately 5% of the diagnoses of sarcomas in soft tissues. It was originally described in 1977, where it was defined as a multilobulated tumor, with myxoid characteristics on the cut surface. Microscopically, a hypocellular myxoid neoplasm is observed, with myxoid areas containing spindle cells, sometimes pleomorphic. The vascular network is evident, and in the more cellular areas, it is common to find mitosis. Sometimes myxoid areas contain “pseudo-lipoblasts” and epithelioid cells that grow diffusely, conferring a more aggressive behavior of the neoplasia. There are no specific immunohistochemical reagents for this tumor; it can be positive for vimentin and CD34 and negative for S100(12).

4.6.4. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma

Uterine myxoid leiomyosarcomas are exceptionally rare and were first described by King et al. in 1982. In this study, 6 cases were reported that were macroscopically characterized by a gelatinous appearance. In the microscopy study, they described neoplastic cells surrounded by an abundant amount of myxoid material with a low mitotic index (0-2 mitoses per high power field). The age range of presentation is from 47 to 68 years, and it manifests as a vaginal or pelvic tumor that produces abnormal bleeding. Although myxoid degeneration in leiomyomas has an incidence of 13%, this finding is very rare in leiomyosarcomas. Microscopically, myxoid leiomyosarcoma is characterized by spindle cells with smooth muscle characteristics, surrounded by a profuse myxoid stroma. Diagnosis requires the presence of mitosis, nuclear atypia, and tumor necrosis. The most important indicator of malignancy is the mitotic index, which is why it is the guideline that distinguishes leiomyosarcomas from cellular leiomyomas. Although myxoid leiomyosarcomas generally have a low mitotic index, they have a similar malignant potential to classical leiomyosarcoma; in these cases, myxoid stroma may be a determining factor. Inflammatory myofibroblastic myxoid tumors can be differentiated from myxoid leiomyosarcoma by the presence of lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate and immunoreactivity for ALK-1(13).

4.6.5. Myxoma

Myxomas are a heterogeneous group of benign soft tissue tumors, first described by Virchow in 1871, which originate from primitive mesenchyme, resembling the structure of the myxoid connective tissue of the umbilical cord. Most are deep lesions and occur in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, and solid organs such as the liver, spleen, and even the parotid gland(14). It commonly affects patients between 40-70 years of age, with a predilection for women of 57%, it presents as a slow-growing tumor that may or may not be painful(15). Histologically they are characterized by scattered, stellar bipolar cells among a vascularized myxoid matrix. It may present hypercellular and hypocellular areas with fibrous areas, there may be few mitoses, and the nuclear chromatin is bland(16).

5. Conclusions

Endometriosis presents a wide range of histopathological aspects, one of which is what we propose as an infrequent variant that can be easily confused with malignant tumors (liposarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma, mucinous carcinoma, etc.). Even among pathologists with extensive experience, we note the diagnostic difficulty. Diagnostic suspicion must be confirmed with immunohistochemistry, showing constant expression of CD10, estrogen, and progesterone receptors in endometriosis. When the endometriosis presents <50% of myxoid background, we propose that it be called “endometriosis with myxoid changes”. On the other hand, if the myxoid background is >50% of the sample, it is better to call it “myxoid endometriosis”. This separation is made because the greater the myxoid stromal component, the more heterogeneous the histological findings are, leading to many differential diagnoses, as discussed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M-P. and S.M-R.; methodology, M.M-P., C.M.H-R. and I.V-R.; software, E.A-G., L.L.M-J. and L.A.R-B.; validation, M.M-P., S.M-R. and C.M.H-R.; formal analysis, M.M-P. and S.M-R.; investigation, C.M.H-R. and I.V-R.; resources, M.M-P., C.M.H-R. and A.R-U.; data curation, S.M-R., M.D.A-Z. and I.V-R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.P. and L.A.R-B.; writing—review and editing, M.M-P., C.M.H-R. and M.A.O-O.; visualization, E.A-G., A.R-U. and L.L-M-J.; supervision, M.M-P. and S.M-R.; project administration, M.M-P.; funding acquisition, M.M-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Following Mexican laws with less risk to the minimum. Informed consent was exempted by the Local Research and Ethics Committee of UMAE Hospital de Alta Especialidad N° 1 Bajío, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. All experimental protocols were approved by the Local Research and Ethics Committee of UMAE Hospital de Alta Especialidad N° 1 Bajío, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, with register CONBIOETICA 11 CEI 003 2018080 and register COFEPRIS 17 CI 11 020 146. The number of institutional register of this research is R-2023-1001-060.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

H.T. Josué Camarena Quiroz, for performing the histological sections and supervising the immunohistochemistry performed on the Pathcom Slide Stainer SSI System platform. To the fellowships Dr. Eduardo Agustin-Godinez, Dr. Lourdes Lucía Morales-Jáuregui for their dedication to the research and monitoring of this research. To the pathology resident Claudia Mariana Hernández-Robles for her confidence to be her thesis director.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest in the elaboration of this investigation.

References

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Wattiez, A.; Gomel, V.; Martin, D.C. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil Steril. 2019, 111, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourial, S.; Tempest, N.; Hapangama, D.K. Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Reprod Med. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.R.; Coddington, C.C. Evolving Spectrum: The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis [Internet]. Available online: www.clinicalobgyn.com.

- Clement, P.B. The Pathology of Endometriosis A Survey of the Many Faces of a Common Disease Emphasizing Diagnostic Pitfalls and Unusual and Newly Appreciated Aspects. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burney, R.O.; Giudice, L.C. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Vol. 98, Fertility and Sterility. 2012. p. 511–9.

- McCluggage, W.G.; Young, R.H. Myxoid change of the myometrium and cervical stroma: Description of a hitherto unreported non-neoplastic phenomenon with discussion of myxoid uterine lesions. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2010, 29, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, S.M.; Wiweger, M.; Van Roggen, J.F.G.; Hogendoorn, P.C.W. Running GAGs: Myxoid matrix in tumor pathology revisited: What’s in it for the pathologist. Vol. 456, Virchows Archiv. 2010. p. 181–92.

- Boyd, C.; McCluggage, W.G. Unusual morphological features of uterine leiomyomas treated with progestogens. J Clin Pathol. 2011, 64, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutter, G.L. Endometriosis. In: Mutter George L., Prat Jaime, editors. Pathology of the Female Reproductive Tract. Third edition. Churchill Livingstone; 2014. p. 487–505.

- Setsu N, Miyake M, Wakai S, Nakatani F, Kobayashi E, Chuman H, et al. Primary Retroperitoneal Myxoid Liposarcomas [Internet]. 2016. Available online: www.ajsp.com.

- Extraskeletal Myxoid Chondrosarcoma Presenting as a Plantar Fibroma.

- Roland, C.L.; Wang, W.L.; Lazar, A.J.; Torres, K.E. Myxofibrosarcoma. Vol. 25, Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. W.B. Saunders; 2016. p. 775–88.

- Kaya, S.; Bacanakgil, H.B.; Soyman, Z.; Öz, İ.; Battal Havare, S.; Kaya, B. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the cervix: A case report. J Obs. Gynaecol (Lahore). 2016, 36, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, V.S.; Rao, R.A.; Prasad, V.; Kamath, P.M.; Rao, K.S. Soft tissue myxoma- a rare differential diagnosis of localized oral cavity lesions. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2014, 8, KD01–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petscavage-Thomas, J.M.; Walker, E.A.; Logie, C.I.; Clarke, L.E.; Duryea, D.M.; Murphey, M.D. Soft-tissue myxomatous lesions: Review of salient imaging features with pathologic comparison. Radiographics 2014, 34, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcucci, J.A.; Bruner, E.T.; Smith, M.T. Benign soft tissue lesions that may mimic malignancy. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016, 33, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).