1. Introduction

Adenomyosis is a benign gynecological condition characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium, often associated with uterine enlargement, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and chronic pelvic pain [

1,

2]. The condition affects approximately 20-35% of women of reproductive age, with a higher prevalence in women aged 40-50 years [

3,

4]. Despite its significant impact on quality of life, including physical, emotional, and social well-being, adenomyosis remains underdiagnosed and poorly understood. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of adenomyosis are still unclear, although several theories have been proposed, including invagination of the basalis endometrium into the myometrium, metaplasia of displaced embryonic cells, and dysregulation of endometrial stem cells [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The most consensual population of cells thought to be endometrial stem cells is called the endometrial side population (ESP), which generates all tissues needed in the normal endometrium throughout its menstrual life cycle [

9,

10]. These cells are believed to play a critical role in endometrial regeneration and repair, and their dysregulation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various gynecological disorders, including adenomyosis, endometriosis, and endometrial cancer [

9,

11,

12,

13]. The Gargett group stated that “the study of ESP cells may provide a breakthrough in understanding not only the physiology of the endometrium but also the pathophysiology of endometrial neoplastic disorders such as endometriosis and endometrial cancer” [

9]. Endometrial stem cells may be identified by several markers, including Numb [

13,

14].

Numb is a membrane-associated protein with a primary function in cell differentiation as an inhibitor of Notch signaling, which is essential for maintaining self-renewal potential in stem and progenitor cells [

15,

16]. Notch is a transmembrane signaling receptor activated by Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 (DSL) family ligands [

17,

18]. Beyond its role in cell differentiation, Numb has been implicated in tumor suppression through its ability to regulate Notch and tumor protein p53 (TP53) [

19]. Specifically, Numb binds and inhibits the E3-ligase Mdm2 (E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mouse double minute 2 homolog), which is responsible for TP53 ubiquitination and degradation [

20,

21]. Additionally, Numb plays a role in cell adhesion through its involvement in endosomal trafficking of transmembrane receptor proteins [

22,

23,

24]. It has been reported to localize in Rab11+ recycling endosomes containing cadherin and to physically interact with the cadherin/catenin complex via its phosphotyrosine-binding domain (PTB) and C-terminal domains [

25,

26] Notably, Numb may also have a functional relationship with Syndecan-1, a heparan sulfate proteoglycan involved in cell adhesion and signaling [

27,

28]. In our previous study, the downregulation of Syndecan-1 in adenomyotic patients suggested a potential role in promoting the invasiveness of endometriotic clusters within the myometrium [

29]. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of Syndecan-1 to the pathogenesis of adenomyosis.

Despite these insights into the multifaceted roles of Numb, its expression status and cellular functions in adenomyosis remain largely unexplored. Given the emerging role of endometrial stem cells in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis and their potential relevance as a future therapeutic target, this study aims to demonstrate, for the first time, the expression of Numb in human adenomyosis tissue. By elucidating the role of Numb in adenomyosis, this research may contribute to a better understanding of the disease’s molecular mechanisms and pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Ethical clearance was granted by the local ethics committee (registration no. 1IX Greb, initially approved on September 19, 2001, and renewed on December 6, 2012; Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe und der Medizinischen Fakultät der WWU). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. All relevant clinical data were collected from patient records and documented systematically to ensure accuracy and confidentiality.

2.2. Sample Collection

Adenomyosis lesions (ectopic endometrium) and corresponding eutopic endometrium were collected between 2016 and 2017 at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Münster University Hospital. Samples were obtained from 21 premenopausal women aged 30–53 years (mean age: 42 years) who underwent hysterectomy for benign gynecological conditions (

Table 1).

All participants were carefully screened for coexisting uterine pathology. Patients with coexisting uterine fibroids were excluded from the adenomyosis group but included in control group to eliminate potential confounding effects on endometrial function and Numb expression. This exclusion criterion was implemented because uterine fibroids, while not considered an endometrial disorder per se, can significantly impact normal endometrial functioning through altered uterine blood flow, mechanical compression, and hormonal influences that could potentially affect stem cell marker expression patterns. The presence of fibroids could therefore confound the interpretation of Numb expression differences between adenomyosis and control groups.

Hysterectomy specimens were meticulously examined through multi-slicing across various regions to macroscopically identify adenomyosis lesions in cases with clinical suspicion of the condition. Only patients with histopathologically confirmed adenomyosis were included in the study. Adenomyosis was defined histopathologically by the presence of endometrial glandular and stromal cells located at least 2.5 mm beneath the endometrial-myometrial junction, accompanied by surrounding myometrial hyperplasia and hypertrophy [

30]. Patients with coexisting pathological conditions, such as genital tumors or other endometrial disorders, were excluded. Additionally, participants were not undergoing hormone therapy at the time of or prior to sample collection. For the control group, endometrial specimens were collected from 14 reproductive-aged women who underwent hysterectomy for benign gynecological conditions unrelated to endometrial disease.

For this study, endometrial tissue analysis encompassed the entire endometrial thickness available in the hysterectomy specimens without separate analysis of functional and basal layer compartments. This methodological approach was selected based on several considerations. The primary objective was to establish the overall expression pattern of Numb in adenomyosis versus control endometrium as an initial investigation. Given the technical challenges of consistently identifying and separating functional and basal layers in hysterectomy specimens, particularly in adenomyosis cases where tissue architecture is often disrupted, a whole-endometrium analysis approach was deemed more reproducible and less prone to sampling bias. While endometrial stem/progenitor cells are known to reside primarily in the basalis layer and luminal epithelium, and differential Numb expression between these compartments would be of interest, such layer-specific analysis would require larger sample sizes and specialized tissue processing protocols including laser capture microdissection or carefully oriented tissue sectioning to ensure accurate anatomical localization. The current study design prioritized establishing baseline Numb expression patterns across the entire endometrial compartment, with layer-specific analysis recommended for future investigations.

To ensure hormone-free tissue samples and eliminate potential hormonal influences on Numb expression, participants with any history of hormonal therapy were excluded from the study. Specifically, patients who had received GnRH agonist therapy, oral contraceptive pills, other hormonal contraceptives, or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections were excluded regardless of the time since discontinuation. This exclusion criterion was implemented to eliminate any potential confounding effects of exogenous hormonal influences on endometrial tissue and Numb expression patterns. All participants confirmed they had never received hormonal therapy or were not undergoing any form of hormone therapy at the time of sample collection, ensuring that the study population consisted entirely of hormone-naive individuals.

Endometrial tissues from both groups were classified into proliferative and secretory phases based on histopathologic criteria established by Noyes et al., 1975. In the adenomyosis group, 17 cases were classified as proliferative phase, three as secretory phase, and one as atrophic endometrium. In the control group, 11 cases were in the proliferative phase, and three were in the secretory phase (

Table 1).

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin according to standard protocols established by the Institute of Pathology at Münster University Hospital. Consecutive 3 μm sections were cut from the paraffin blocks and mounted onto poly-L-lysine-coated glass slides. The sections were dried overnight, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series.

Antigen retrieval was performed using a target retrieval solution (pH 6.0, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) in a steamer for 35 minutes, followed by three washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the sections with a peroxidase-blocking solution (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for 10 minutes. To reduce nonspecific binding, sections were further blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Aurion, DAKO) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

After blocking, sections were incubated with primary antibody. For Numb protein detection, a rabbit polyclonal anti-Numb antibody (1:70 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted in DAKO Real Antibody Diluent was applied. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibody. Incubation was carried out for 1 hour at room temperature.

Following primary antibody incubation, sections were washed three times in PBS (5 minutes each). Secondary antibody detection was performed using the EnVision system (anti-rabbit, DAKO) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After another series of PBS washes (three times for 5 minutes each), the immunohistochemical signal was developed using AEC substrate chromogen (3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, DAKO) for 6 minutes at room temperature, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sections were briefly rinsed in PBS, counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for nuclear staining, and mounted in GelTol Aqueous Mounting Medium (Immunotech).

2.4. Microscopic Evaluation

Light microscopic evaluation was independently conducted by two blinded observers (WS and MGI) to ensure objectivity and minimize bias. Microscopic analysis was performed using a Zeiss Axiophot 100 microscope equipped with a CCD camera and Axiovision software (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). Staining intensity and distribution were assessed at 200× magnification for each stained section. Positive controls (monkey brain tissue [

32], kindly provided by Prof. S. Schlatt, CeRA Münster) and negative controls (sections incubated without primary antibody) were included in each run to validate the staining protocol and ensure specificity. Only samples with unambiguous staining results were included in the final analysis [

14].

2.5. Evaluation System and Scoring for Numb Expression

Numb expression was evaluated using a standardized scoring system based on the following criteria [

14]:

Staining Localization: Diffuse cytoplasmic staining was assessed separately for glandular epithelial cells, stromal cells, and smooth muscle cells.

Staining Intensity: A two-point scoring scale was used: 0: Negative staining (no detectable signal), and 1: Positive staining (detectable signal).

Quantification of Positively Stained Cells: Positively stained cells were counted per high-power field (HPF) at 200× magnification. Positively stained cells were further categorized into: Single cells: Individual positively stained cells, and Cell nests: with Foci of ≥ 3 positively stained cells per HPF.

Inclusion Criteria: Only samples with clear and unambiguous staining patterns were included in the final analysis to ensure reliability and reproducibility.

2.6. Statistical analyses

The data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics, version 20.0 software, (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Qualitative variables were described by numbers and percentages. The normality of the distribution of variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Quantitative data were presented as range (minimum-maximum), mean ± standard deviation (SD), and median. For Numb differences in expression among groups, non-parametric tests were applied as its data did not satisfy normal distribution. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparisons involving more than two groups, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The age distribution in both premenopausal groups (range: 30–53 years) showed no significant difference, with a mean age of 42.1 ± 6.2 years in the adenomyosis group and 43.4 ± 9.1 years in the control group (p = 0.56). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in gravidity (1.9 ± 2.1 vs. 1.8 ± 1.6, p = 0.87) or parity (1.3 ± 1.5 vs. 1.2 ± 1.3, p = 0.92) between the adenomyosis and control groups. Specifically, the proportion of nulliparous and multiparous patients did not differ significantly between the two groups.

3.1. Expression and localization of Numb protein

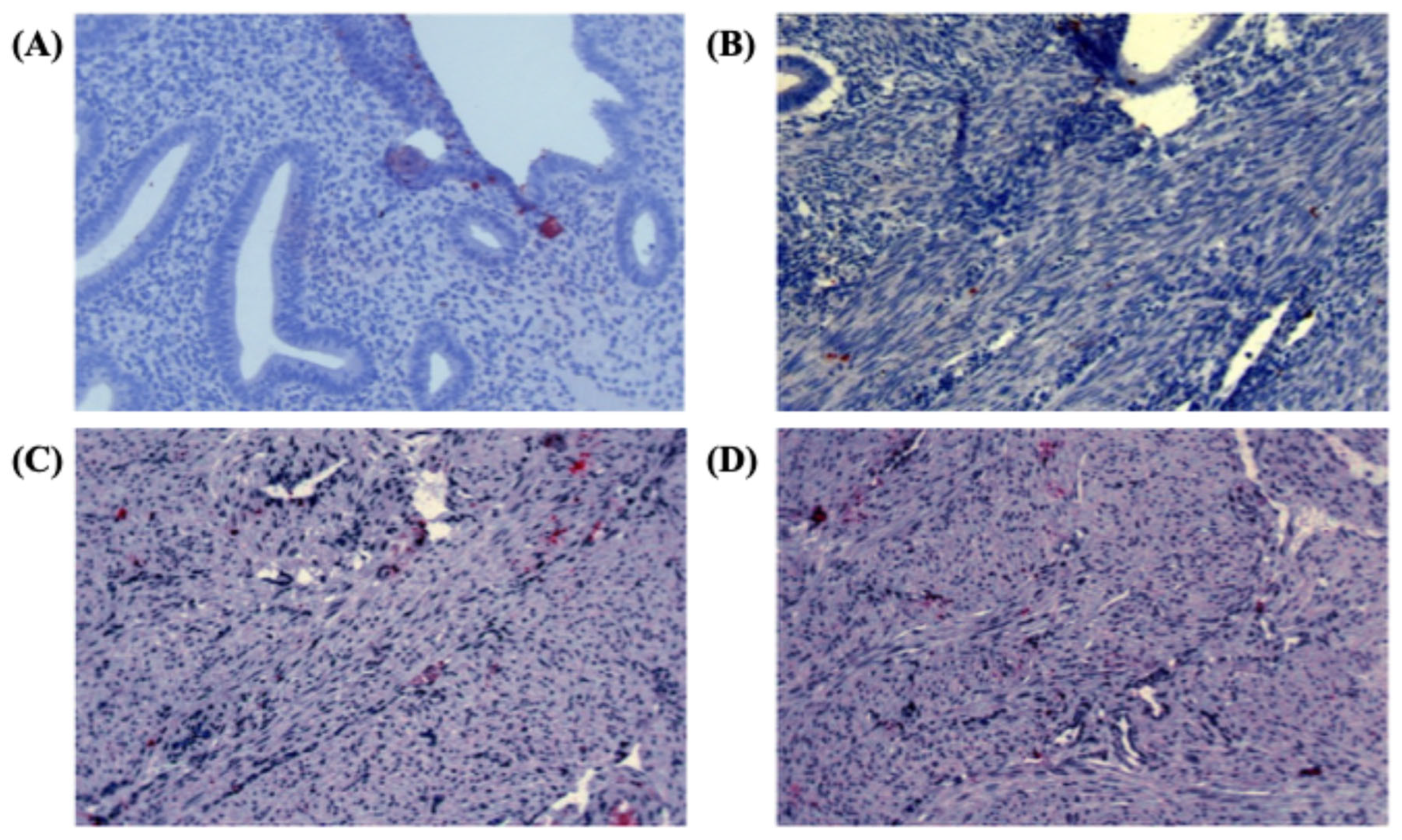

The specificity of the Numb antibody was confirmed by the diffuse cytoplasmic staining pattern observed in positive control samples derived from monkey brain tissue (

Figure 1A). In the study samples, Numb protein expression was evaluated across different tissue compartments, including the endometrial glands, stromal cells, and myometrium. In the eutopic endometrium, Numb exhibited a diffuse cytoplasmic staining pattern in both the luminal epithelium and stromal cells, as illustrated in

Figure 1A. This suggests that Numb is constitutively expressed in the normal endometrial tissue, potentially playing a role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. In contrast, within the myometrium of adenomyosis patients, Numb expression was also observed, with distinct staining patterns in both single cells and cell nests (

Figure 1B-D). This indicates that Numb may be involved in the pathological processes associated with adenomyosis, particularly in the ectopic endometrial tissue.

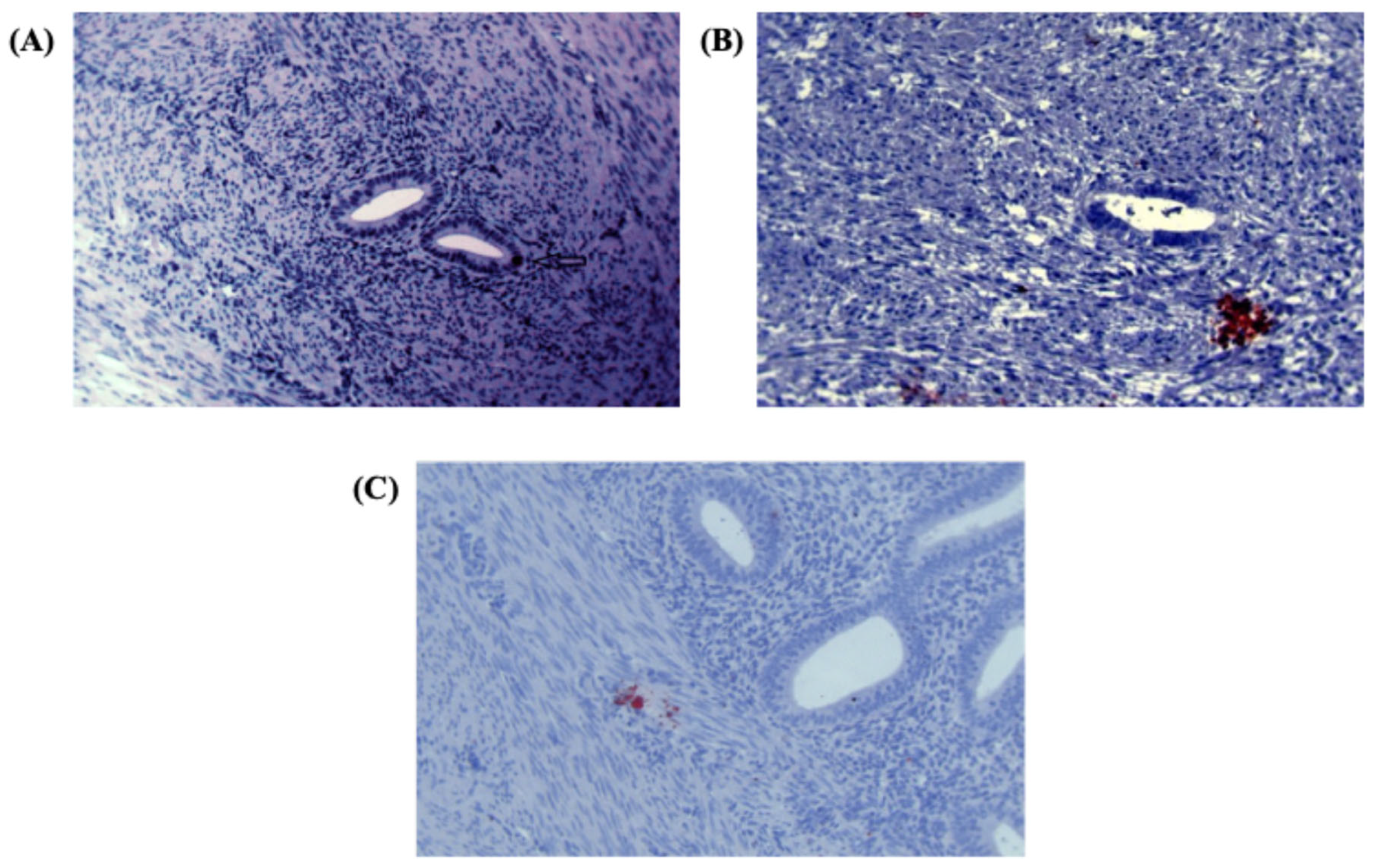

Further analysis revealed Numb expression in the ectopic endometrium, with single cell staining observed in the glandular epithelium (

Figure 2A) and cell nest staining in the stroma (

Figure 2B). The presence of cell nests, defined as foci of ≥ 3 positively stained cells per high-power field, suggests a potential role for Numb in cell clustering or proliferation within ectopic lesions. Additionally, in the myometrium of adenomyosis patients, Numb expression was detected in both single cells and cell nests (

Figure 2C), further supporting its involvement in the disease pathology.

3.2. Numb Expression in Human Endometrium and Myometrium

Following the analysis of Numb localization, we evaluated its expression using a standardized scoring system [

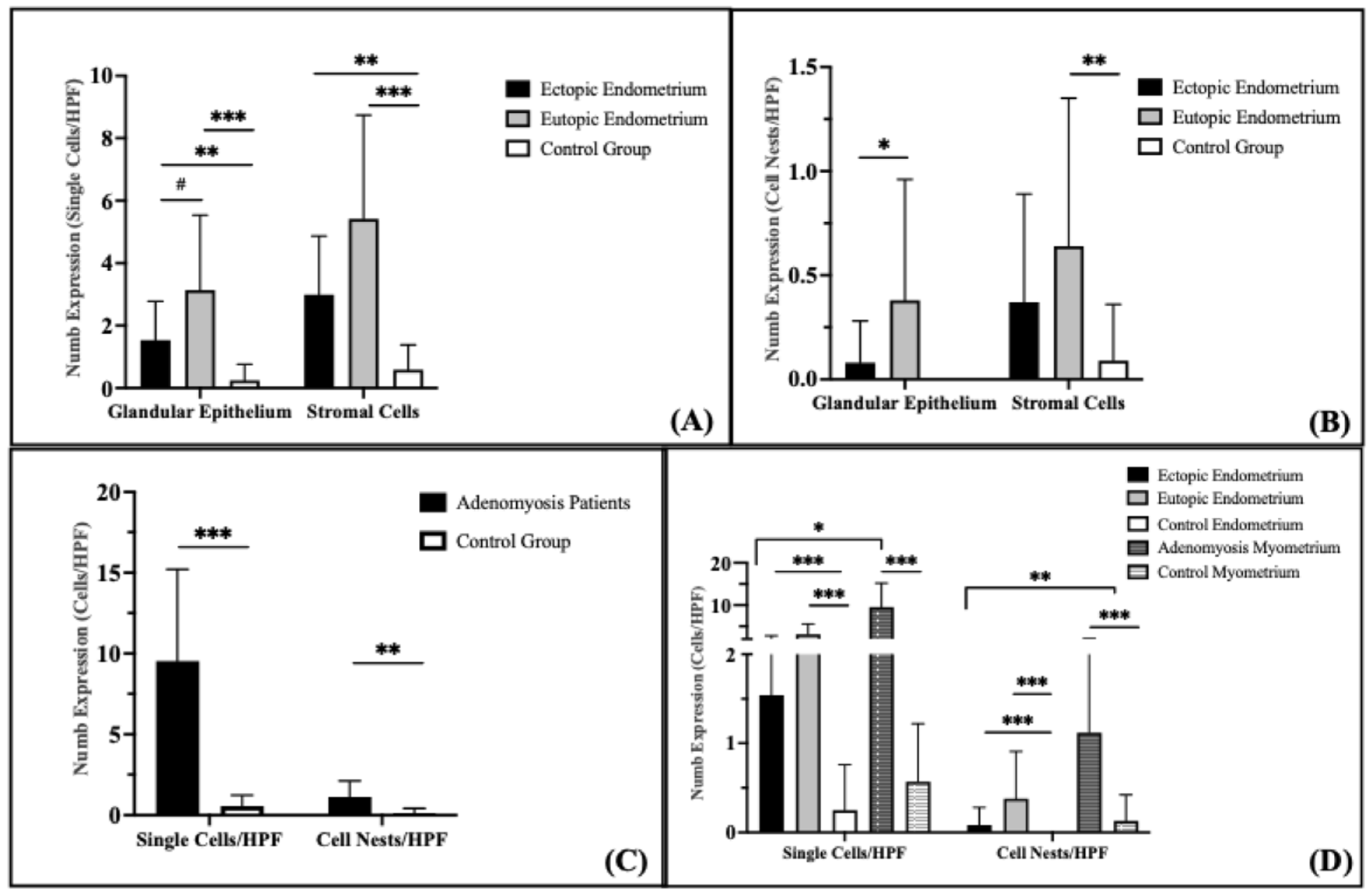

14]. In the glandular epithelium, Numb protein expression as single cells/HPF was significantly increased in both the ectopic (

p = 0.015) and eutopic (

p < 0.001) endometrium of adenomyosis patients compared to the control group (

Figure 3A). Numb expression was also higher in the eutopic endometrium than in the ectopic endometrium, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (

p = 0.072). In the stromal compartment, Numb expression showed a statistically significant increase in the eutopic endometrium compared to both the ectopic endometrium (

p = 0.042) and the control group (

p < 0.001). These findings suggest that Numb is more prominently expressed in the eutopic endometrium, particularly in the stromal cells, which may reflect its role in maintaining endometrial homeostasis or contributing to disease pathology.

Evaluation of Numb expression in cell nests revealed distinct patterns across the groups (

Figure 3B). No Numb-positive cell nests were detected in the glandular epithelium of the control group. In contrast, Numb expression in the glandular epithelium of the eutopic endometrium was significantly higher than in the ectopic endometrium (

p = 0.038). In the stroma, the number of Numb-positive cell nests was significantly higher in the eutopic endometrium compared to the control group (

p = 0.009), but no significant difference was observed between the eutopic and ectopic endometrium (

p = 0.259). Although Numb expression in the ectopic endometrium was increased compared to the control group, this difference did not reach statistical significance (

p = 0.112).

Numb-positive cells were significantly increased in the myometrium of adenomyosis patients compared to the control group, both as single cells/HPF (

p < 0.001) and as cell nests/HPF (

p = 0.002) (

Figure 3C). This suggests that Numb may play a role in the pathological remodeling of the myometrium in adenomyosis.

When comparing Numb expression between the endometrium and myometrium, several key findings emerged (

Figure 3D). The number of Numb-positive single cells was significantly higher than cell nests/HPF in both the ectopic and eutopic endometrium of adenomyosis patients (

p = 0.001). Similarly, Numb-positive single stromal cells were significantly more abundant than stromal cell nests in adenomyosis patients (

p < 0.001), but this difference was not observed in the control group (

p = 0.061). In the myometrium, Numb-positive single cells were significantly more prevalent than cell nests in adenomyosis patients (

p < 0.001), while no significant difference was observed in the control group (

p = 0.062). Overall, Numb expression in the myometrium was significantly higher than in the endometrium, with a two-fold increase compared to the stroma and a three-fold increase compared to the glandular epithelium in adenomyosis patients. These results collectively demonstrate that Numb is differentially expressed across tissue compartments in adenomyosis, with higher expression in the myometrium and eutopic endometrium compared to the ectopic endometrium and control group. The predominance of single cell staining over cell nests suggests that Numb may play a role in individual cell regulation rather than in clustered cell behavior.

3.3. Expression of Numb protein in the endometrium of the proliferative and secretory phase

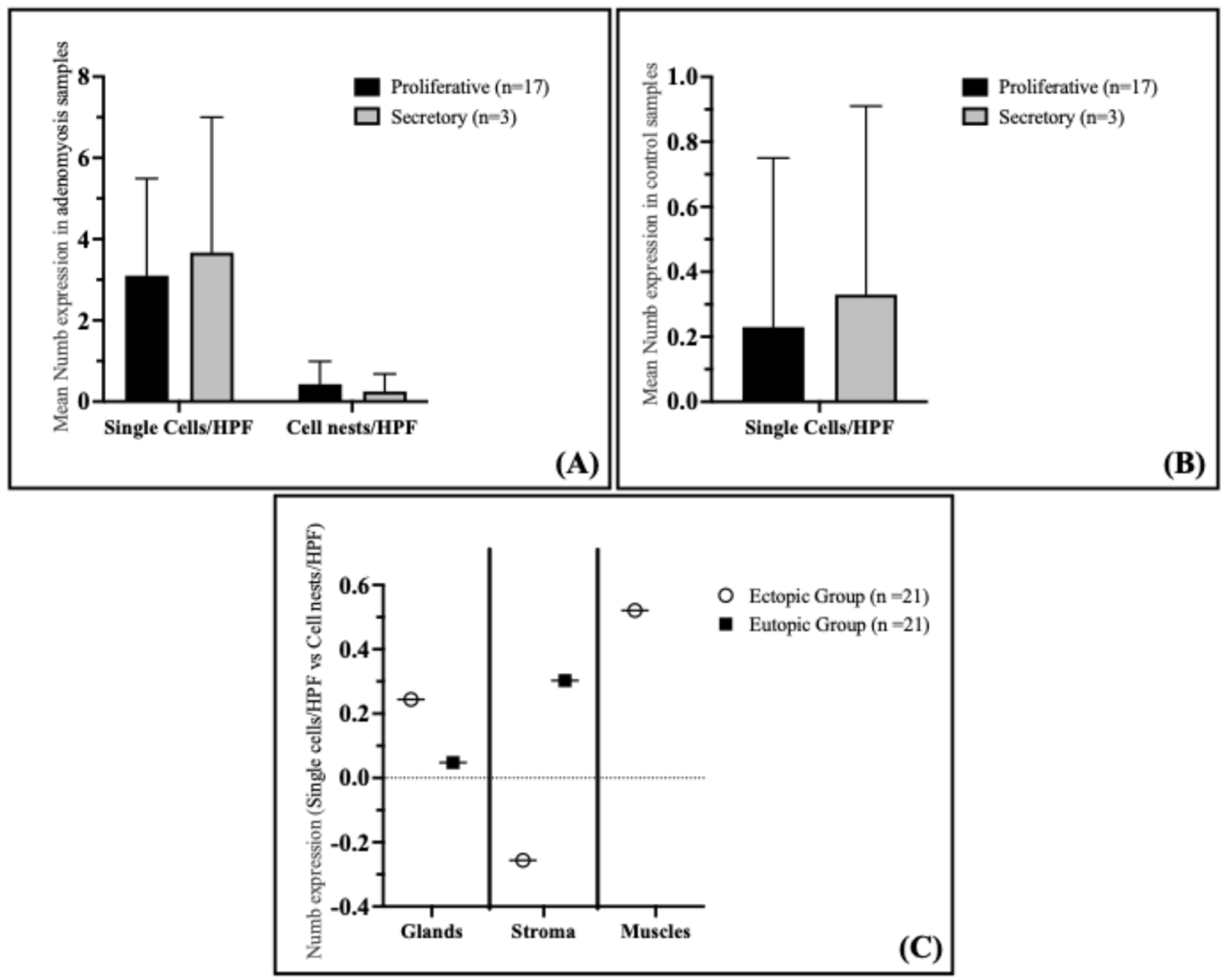

Analysis of Numb expression in the proliferative and secretory phases of the endometrium in adenomyosis patients revealed that Numb expression does not correlate with the menstrual cycle phase. Specifically, no significant differences were observed in the staining index of Numb in the glandular epithelium, either as single cells or cell nests, between the proliferative and secretory phases (

Figure 4A). The mean Numb expression in single cells/HPF was 3.10 ± 2.39 in the proliferative phase and 3.67 ± 3.33 in the secretory phase (

p = 0.591). Similarly, for cell nests/HPF, the mean expression was 0.43 ± 0.56 in the proliferative phase and 0.25 ± 0.43 in the secretory phase (

p = 0.643). These findings suggest that Numb expression in the eutopic endometrium of adenomyosis patients is independent of the menstrual cycle phase.

In the control group, Numb expression in the proliferative and secretory phases of the endometrium also showed no correlation with the menstrual cycle phase. Similar to the adenomyosis group, the immunostaining of Numb in the glandular epithelium did not differ significantly between the proliferative and secretory phases (

Figure 4B). The mean Numb expression in single cells/HPF was 0.23 ± 0.52 in the proliferative phase and 0.33 ± 0.58 in the secretory phase (

p = 0.664). This further supports the conclusion that Numb expression is not influenced by the menstrual cycle phase in either adenomyosis patients or controls.

For the analysis of menstrual cycle variation in Numb protein expression, evaluation encompassed the entire endometrial thickness available in the hysterectomy specimens, including both functional and basal layer components where identifiable. The analysis approach focused on overall endometrial Numb expression patterns rather than layer-specific evaluation. This whole-endometrium methodology was selected considering that the functional layer undergoes more dramatic cyclical changes compared to the relatively stable basal layer, and a combined analysis approach would provide an integrated assessment of Numb expression across the complete endometrial compartment. The methodological design recognizes that stable expression patterns in the basal layer may influence the detection of cyclical variations that could be more pronounced in the functional layer alone. This approach was chosen to establish baseline cycle-phase relationships in the context of overall endometrial Numb expression, with the understanding that future layer-specific analyses would provide additional insights into the cyclical regulation of Numb expression in different endometrial compartments.

Interestingly, a significant positive correlation was observed between the number of Numb-positive single cells and cell nests in the myometrium of adenomyosis patients (Spearman coefficient rs = 0.521,

p = 0.015) (

Figure 4C). This suggests that as the number of Numb-positive single cells increases, so does the number of cell nests, indicating a potential relationship between individual cell expression and clustered cell behavior in the myometrium. However, no significant correlations were observed in the glandular epithelium or stroma of either the ectopic or eutopic endometrium.

4. Discussion

Gynecological diseases such as endometriosis, endometrial cancers, and adenomyosis have been suggested to potentially develop from abnormalities in endometrial cell proliferation [

33]. Our study highlights the significant role of Numb, a key regulator of cell fate and stem cell maintenance, in human adenomyosis uterine tissues. These findings provide novel insights into the potential role of Numb as a marker for endometrial stem cells in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis.

Our study demonstrates a significant association of Numb expression in human adenomyosis tissues, suggesting its potential role as a stem cell marker in the etiology of this disorder. For the first time, we have shown the expression of Numb in adenomyosis tissues from 21 patients compared to 14 controls. Notably, we observed differential expression of Numb in the eutopic endometrium of adenomyosis patients compared to healthy controls, indicating a possible dysregulation of stem cell-related pathways in adenomyosis.

In our pilot study, we found that Numb protein is significantly upregulated in the myometrium of adenomyosis uteri. Furthermore, Numb-positive endometrial cells were highly expressed in both eutopic endometrial tissues and adenomyotic foci within the myometrium, compared to the endometrium of the control group. Importantly, our results did not reveal significant cyclical variation in Numb expression, suggesting that its role in adenomyosis may be independent of hormonal fluctuations.

These findings align with previous studies reporting increased expression of stemness-related markers in adenomyosis. For instance, Chen et al. (2014) demonstrated elevated expression of Musashi-1, another stem cell marker, in both eutopic and ectopic endometrium of women with adenomyosis [

34]. Musashi-1, an epithelial progenitor cell marker, regulates self-renewal pathways and has been shown to repress the translation of Numb mRNA in malignant hematopoietic cells [

35]. In endometriosis, downregulation of Musashi-1 and -2 resulted in decreased cell viability and increased apoptosis of endometriotic cells, which were linked to the dysregulation of stem cell factors and p21 [

36]. These findings suggest a complex interplay between stem cell markers and Numb, which may also be relevant for the pathogenesis of adenomyosis.

Numb and Notch are evolutionarily conserved proteins that play critical roles in cell fate determination and stem cell maintenance. Numb acts as a functional antagonist of Notch by promoting its proteolytic degradation via endocytosis, thereby regulating Notch-mediated signaling [

37]. In addition to its role in physiological cell development, Numb has been implicated in proliferative diseases, including neoplasms [

38]. The multifunctional role of Numb extends to the regulation of cell adhesion and migration, processes that are crucial in tumorigenesis and may also contribute to the development of adenomyosis [

15]. Our findings suggest that Numb may play a non-stem cell-related role in adenomyosis by modulating these cellular processes, thereby facilitating the invasion of endometrial tissue into the myometrium.

The upregulation of adult stem cell markers in adenomyosis may alter the proliferation and apoptosis of endometrial cells, promoting the invasion of endometrial tissue into the myometrium. This hypothesis is supported by previous studies that reported higher expression of stem cell markers OCT4 and SOX2 in the myometrium of bovine adenomyosis tissues compared to the endometrial layer [

39]. Similarly, our results indicate that the overexpression of Numb in the myometrial layer of adenomyosis tissues may enhance the infiltration of endometrial tissue into the myometrium, contributing to the development of adenomyosis.

The clinical significance of our findings lies in the potential for targeting Numb as a therapeutic approach for adenomyosis. Currently, there is no definitive treatment for adenomyosis, and hormonal therapies often yield limited results due to the hormone-refractory nature of ectopic endometrial tissue. Rennstam et al. (2010) proposed that targeting Numb degradation could be an effective treatment strategy for triple-negative tumors, which lack targets for antihormonal and HER2-targeted therapies [

40]. This approach may also hold promise for adenomyosis, particularly in cases resistant to conventional treatments.

The correlation between stem cell markers and the menstrual cycle remains controversial. Our study found no significant differences in Numb expression between the proliferative and secretory phases, consistent with previous studies that reported no cyclical variation in the expression of pluripotency factors such as SOX2 and Musashi-1 [

14,

41,

42]. However, some studies have reported increased expression of stem cell markers like SOX2 and Musashi-1 in the proliferative phase of endometriosis patients [

43,

44]. This discrepancy highlights the need for further research into the hormonal regulation of stem cell markers in adenomyosis.

A potential limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size, particularly for secretory phase endometrium, which constituted only 15% of the adenomyosis samples. This may have limited the statistical power of some analyses. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate our findings and explore the role of stem cell-related factors in adenomyosis more comprehensively. Additionally, further research is required to elucidate the mechanisms by which Numb and other stem cell markers contribute to the pathogenesis of adenomyosis.

Our study provides valuable insights into the role of Numb as a potential stem cell marker in adenomyosis. The upregulation of Numb in adenomyosis tissues suggests its involvement in the dysregulation of endometrial cell proliferation and myometrial invasion. While our findings highlight Numb as a potential molecular target for adenomyosis, the precise mechanisms underlying its role in this disease remain to be fully elucidated. Future research should focus on exploring the therapeutic potential of targeting Numb and other stem cell-related markers in the treatment of adenomyosis.

Study Limitations

Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the sample size, particularly for secretory phase analysis (n=3), limits statistical power and the generalizability of findings to broader populations. Second, inherent technical variability in tissue processing, immunohistochemical staining intensity, and image capture procedures may affect the reproducibility of results across different experimental runs. Additionally, the cross-sectional study design prevents assessment of temporal changes in Numb expression during disease progression, and the focus on protein expression analysis does not address the functional consequences of elevated Numb levels or the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for its upregulation in adenomyosis. Future investigations should incorporate larger sample sizes, validated quantification methodologies, automated image analysis systems, and functional studies to provide more comprehensive evidence for the role of Numb in adenomyosis pathogenesis.

5. Conclusion

This study provides the first evidence of significantly elevated Numb protein expression in both eutopic endometrium and myometrium of adenomyosis patients compared to controls, establishing a novel molecular signature associated with this prevalent gynecological condition. The consistent upregulation of Numb across different tissue compartments, independent of menstrual cycle phase, suggests a fundamental role for this stem cell regulatory protein in adenomyosis pathogenesis. These findings support the emerging paradigm that dysregulation of endometrial stem cell markers contributes to the development and progression of adenomyosis, potentially through altered Notch signaling pathways and disrupted cellular differentiation processes. The predominant single-cell expression pattern observed indicates that Numb upregulation may reflect individual stem or progenitor cell dysfunction rather than coordinated tissue-level changes. While the current study establishes Numb as a potential biomarker for adenomyosis and provides insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying this condition, future investigations incorporating larger sample sizes, layer-specific analysis, functional studies, and mechanistic exploration are essential to fully elucidate the therapeutic potential of targeting Numb-related pathways. These findings represent an important step toward understanding the stem cell biology of adenomyosis and may ultimately contribute to the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for this challenging gynecological disorder.

Author Contributions

WS: Investigation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, NH: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition, MGI: Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, BS: Visualization, Editing, LK: Resources, ANS: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, MG: Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition; all authors: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This research was funded by EU H2020-RISE project TRENDO, grant # 101008193 (to M.G.) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) German Egyptian Research Long-Term Scholarship program (GERLS) Grant 91664677 (to N.H.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Ethical clearance was granted by the local ethics committee (registration no. 1IX Greb, initially approved on September 19, 2001, and renewed on December 6, 2012; Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe und der Medizinischen Fakultät der WWU).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. All relevant clinical data were collected from patient records and documented systematically to ensure accuracy and confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Birgit Pers for expert technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| endometrial side population |

ESP |

| Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 |

DSL |

| tumor protein p53 |

TP53 |

| E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mouse double minute 2 homolog |

E3-ligase Mdm2 |

| phosphotyrosine-binding domain |

PTB |

| Institutional Review Board |

IRB |

| phosphate-buffered saline |

PBS |

| bovine serum albumin |

BSA |

| standard deviation |

SD |

References

- Struble, J.; Reid, S.; Bedaiwy, M.A. Adenomyosis: A Clinical Review of a Challenging Gynecologic Condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2016, 23, 164–185. [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini, S.; Petraglia, F. Recent Advances in Understanding and Managing Adenomyosis. F1000Res 2019, 8, 283. [CrossRef]

- Upson, K.; Missmer, S.A. Epidemiology of Adenomyosis. Semin Reprod Med 2020, 38, 089–107. [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini, S.; Meleca, C.; Toscano, F.; Mertino, P.; Pampaloni, F.; Fambrini, M.; Bruni, V.; Petraglia, F. Adenomyosis Diagnosis among Adolescents and Young Women with Dysmenorrhoea and Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. Reprod Biomed Online 2024, 48, 103768. [CrossRef]

- Taran, F.; Stewart, E.; Brucker, S. Adenomyosis: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Clinical Phenotype and Surgical and Interventional Alternatives to Hysterectomy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2013, 73, 924–931. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Vannuccini, S.; Capezzuoli, T.; Fambrini, M.; Vannuzzi, V.; Donati, C.; Petraglia, F. Mechanisms and Pathogenesis of Adenomyosis. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 2022, 11, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini, S.; Tosti, C.; Carmona, F.; Huang, S.J.; Chapron, C.; Guo, S.-W.; Petraglia, F. Pathogenesis of Adenomyosis: An Update on Molecular Mechanisms. Reprod Biomed Online 2017, 35, 592–601. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.N.; Fujishita, A.; Mori, T. Pathogenesis of Human Adenomyosis: Current Understanding and Its Association with Infertility. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 4057. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Maruyama, T.; Gargett, C.E.; Miyazaki, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Okano, H.; Tanaka, M. Endometrial Side Population Cells: Potential Adult Stem/Progenitor Cells in Endometrium1. Biol Reprod 2015, 93. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Hiratsu, E.; Ono, M.; Nagashima, T.; Kajitani, T.; Arase, T.; Oda, H.; Uchida, H.; Asada, H.; et al. Stem Cell-Like Properties of the Endometrial Side Population: Implication in Endometrial Regeneration. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10387. [CrossRef]

- Donnez, J.; Stratopoulou, C.A.; Dolmans, M.-M. Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Similarities and Differences. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2024, 92, 102432. [CrossRef]

- El Sabeh, M.; Afrin, S.; Singh, B.; Miyashita-Ishiwata, M.; Borahay, M. Uterine Stem Cells and Benign Gynecological Disorders: Role in Pathobiology and Therapeutic Implications. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021, 17, 803–820. [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.-S. Endometrial Stem/Progenitor Cells: Properties, Origins, and Functions. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 931–947. [CrossRef]

- Schüring, A.N.; Dahlhues, B.; Korte, A.; Kiesel, L.; Titze, U.; Heitkötter, B.; Ruckert, C.; Götte, M. The Endometrial Stem Cell Markers Notch-1 and Numb Are Associated with Endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online 2018, 36, 294–301. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Campos, S.M.; García-Heredia, J.M. The Multitasker Protein: A Look at the Multiple Capabilities of NUMB. Cells 2023, 12, 333. [CrossRef]

- Verdi, J.M.; Bashirullah, A.; Goldhawk, D.E.; Kubu, C.J.; Jamali, M.; Meakin, S.O.; Lipshitz, H.D. Distinct Human NUMB Isoforms Regulate Differentiation vs. Proliferation in the Neuronal Lineage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 10472–10476. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Lin, W.; Long, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, K.; Chu, Q. Notch Signaling Pathway: Architecture, Disease, and Therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 95. [CrossRef]

- Lendahl, U. A Growing Family of Notch Ligands. BioEssays 1998, 20, 103–107. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ronai, Z.A. Rewired Notch/P53 by Numb’ing Mdm2. Journal of Cell Biology 2018, 217, 445–446. [CrossRef]

- Dho, S.E.; French, M.B.; Woods, S.A.; McGlade, C.J. Characterization of Four Mammalian Numb Protein Isoforms. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 33097–33104. [CrossRef]

- Yogosawa, S.; Miyauchi, Y.; Honda, R.; Tanaka, H.; Yasuda, H. Mammalian Numb Is a Target Protein of Mdm2, Ubiquitin Ligase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003, 302, 869–872. [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.A.; Dho, S.E.; Weinmaster, G.; McGlade, C.J. Numb Regulates Post-Endocytic Trafficking and Degradation of Notch1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 26427–26438. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Kaibuchi, K. Numb Controls Integrin Endocytosis for Directional Cell Migration with APKC and PAR-3. Dev Cell 2007, 13, 15–28. [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Ding, Z.; Qian, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, N.; Gui, L.; Xu, Z.; et al. Numb Regulates Vesicular Docking for Homotypic Fusion of Early Endosomes via Membrane Recruitment of Mon1b. Cell Res 2016, 26, 593–612. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.T.; Mirzadeh, Z.; Soriano-Navarro, M.; Rašin, M.; Wang, D.; Shen, J.; Šestan, N.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.; Alvarez-Buylla, A.; Jan, L.Y.; et al. Postnatal Deletion of Numb/Numblike Reveals Repair and Remodeling Capacity in the Subventricular Neurogenic Niche. Cell 2006, 127, 1253–1264. [CrossRef]

- Lock, J.G.; Stow, J.L. Rab11 in Recycling Endosomes Regulates the Sorting and Basolateral Transport of E-Cadherin. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 1744–1755. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Greve, B.; Espinoza-Sánchez, N.A.; Götte, M. Cell-Surface Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans as Multifunctional Integrators of Signaling in Cancer. Cell Signal 2021, 77, 109822. [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.; Oh, E.-S.; Couchman, J.R. Syndecan Proteoglycans and Cell Adhesion. Matrix Biology 1998, 17, 477–483. [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, W.; Ibrahim, M.G.; Plasger, A.; Hassan, N.; Kiesel, L.; Schüring, A.N.; Götte, M. Decreased Expression of Syndecan-1 (CD138) in the Endometrium of Adenomyosis Patients Suggests a Potential Pathogenetic Role. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2025, 104, 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.C.; McElin, T.W.; Manalo-Estrella, P. The Elusive Adenomyosis of the Uterus—Revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972, 112, 583–593. [CrossRef]

- Noyes, R.W.; Hertig, A.T.; Rock, J. Dating the Endometrial Biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975, 122, 262–263. [CrossRef]

- Zangenehpour, S.; Burke, M.W.; Chaudhuri, A.; Ptito, M. Batch Immunostaining for Large-Scale Protein Detection in the Whole Monkey Brain. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2009. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.; Isaacson, K. Adenomyosis: Review of the Literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2011, 18, 428–437. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.-H.; Yan, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.-F.; Zhou, F. Increased Expression of the Adult Stem Cell Marker Musashi-1 in the Ectopic Endometrium of Adenomyosis Does Not Correlate with Serum Estradiol and Progesterone Levels. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2014, 173, 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Tokunaga, A.; Yoshida, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Mikoshiba, K.; Weinmaster, G.; Nakafuku, M.; Okano, H. The Neural RNA-Binding Protein Musashi1 Translationally Regulates Mammalian Numb Gene Expression by Interacting with Its MRNA. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21, 3888–3900. [CrossRef]

- Strauß, T.; Greve, B.; Gabriel, M.; Achmad, N.; Schwan, D.; Espinoza-Sanchez, N.A.; Laganà, A.S.; Kiesel, L.; Poutanen, M.; Götte, M.; et al. Impact of Musashi-1 and Musashi-2 Double Knockdown on Notch Signaling and the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2851. [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.A.; McGlade, C.J. Mammalian Numb Proteins Promote Notch1 Receptor Ubiquitination and Degradation of the Notch1 Intracellular Domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 23196–23203. [CrossRef]

- Pece, S.; Confalonieri, S.; R. Romano, P.; Di Fiore, P.P. NUMB-Ing down Cancer by More than Just a NOTCH. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2011, 1815, 26–43. [CrossRef]

- Łupicka, M.; Socha, B.; Szczepańska, A.; Korzekwa, A. Expression of Pluripotency Markers in the Bovine Uterus with Adenomyosis. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2015, 13, 110. [CrossRef]

- Rennstam, K.; McMichael, N.; Berglund, P.; Honeth, G.; Hegardt, C.; Rydén, L.; Luts, L.; Bendahl, P.-O.; Hedenfalk, I. Numb Protein Expression Correlates with a Basal-like Phenotype and Cancer Stem Cell Markers in Primary Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010, 122, 315–324. [CrossRef]

- Bentz, E.-K.; Kenning, M.; Schneeberger, C.; Kolbus, A.; Huber, J.C.; Hefler, L.A.; Tempfer, C.B. OCT-4 Expression in Follicular and Luteal Phase Endometrium: A Pilot Study. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2010, 8, 38. [CrossRef]

- Forte, A.; Schettino, M.T.; Finicelli, M.; Cipollaro, M.; Colacurci, N.; Cobellis, L.; Galderisi, U. Expression Pattern of Stemness-Related Genes in Human Endometrial and Endometriotic Tissues. Molecular Medicine 2009, 15, 392–401. [CrossRef]

- Götte, M.; Wolf, M.; Staebler, A.; Buchweitz, O.; Kelsch, R.; Schüring, A.; Kiesel, L. Increased Expression of the Adult Stem Cell Marker Musashi-1 in Endometriosis and Endometrial Carcinoma. J Pathol 2008, 215, 317–329. [CrossRef]

- Götte, M.; Wolf, M.; Staebler, A.; Buchweitz, O.; Kiesel, L.; Schüring, A.N. Aberrant Expression of the Pluripotency Marker SOX-2 in Endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2011, 95, 338–341. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).