Submitted:

04 August 2023

Posted:

07 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. National obligations: An information-based management

3. Improving profitability and sustainability through governance

3.1. Governance in implementing and monitoring catch regulations

3.2. Contribution to economy and livelihood

3.3. Governance of fleet size control

3.4. Fishing within EEZ

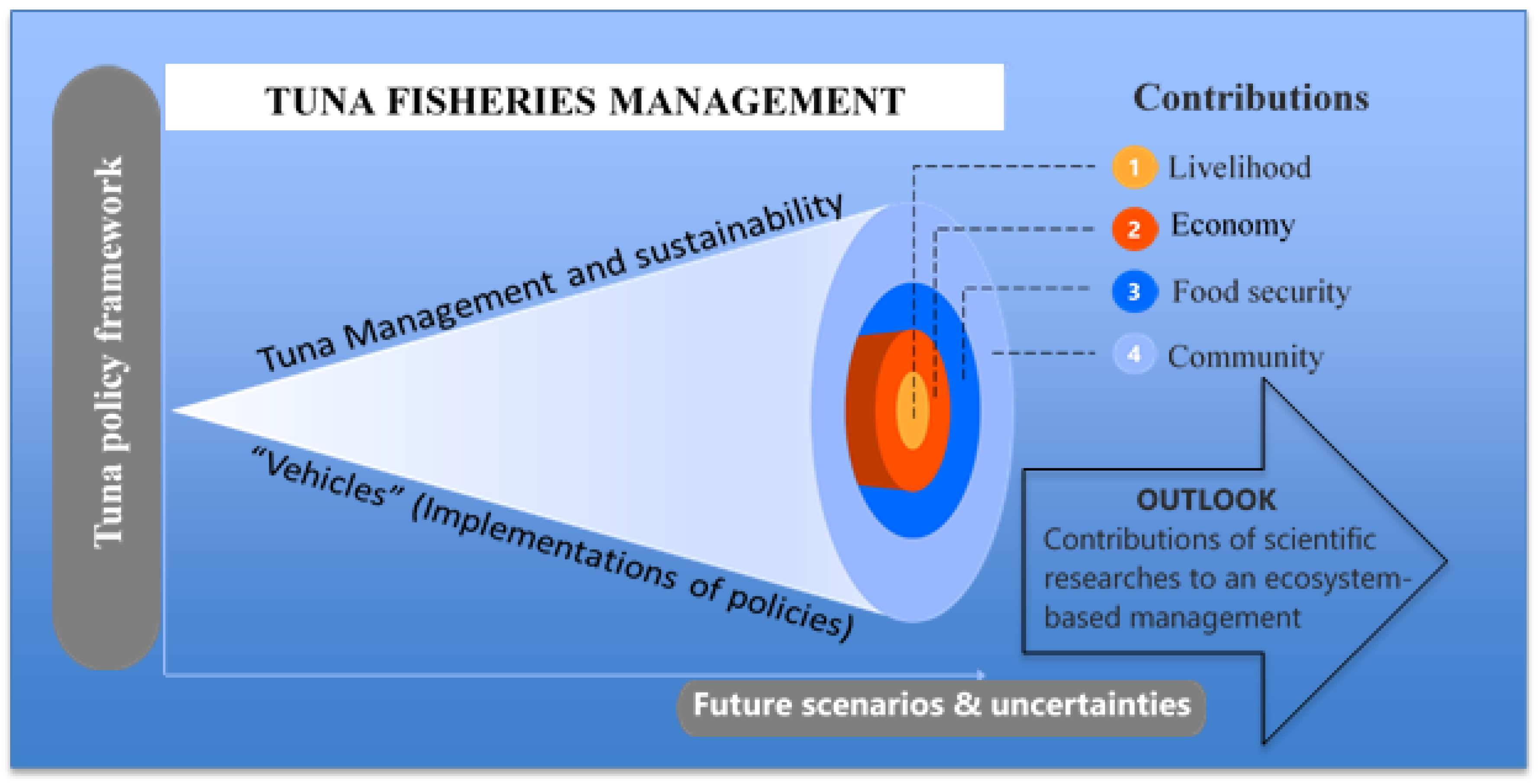

4. Research opportunities in relation to an ecosystem-based approach to tuna management

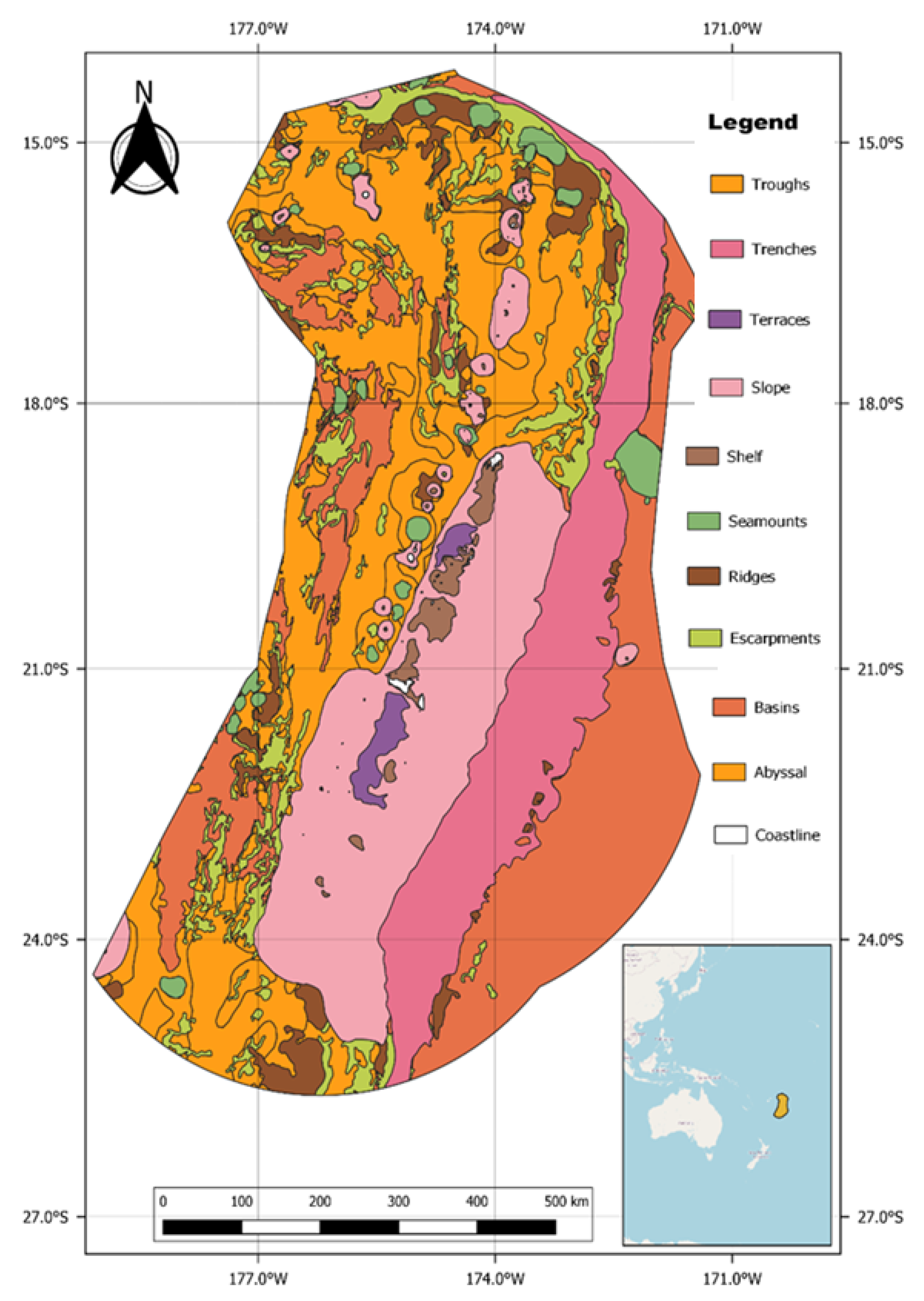

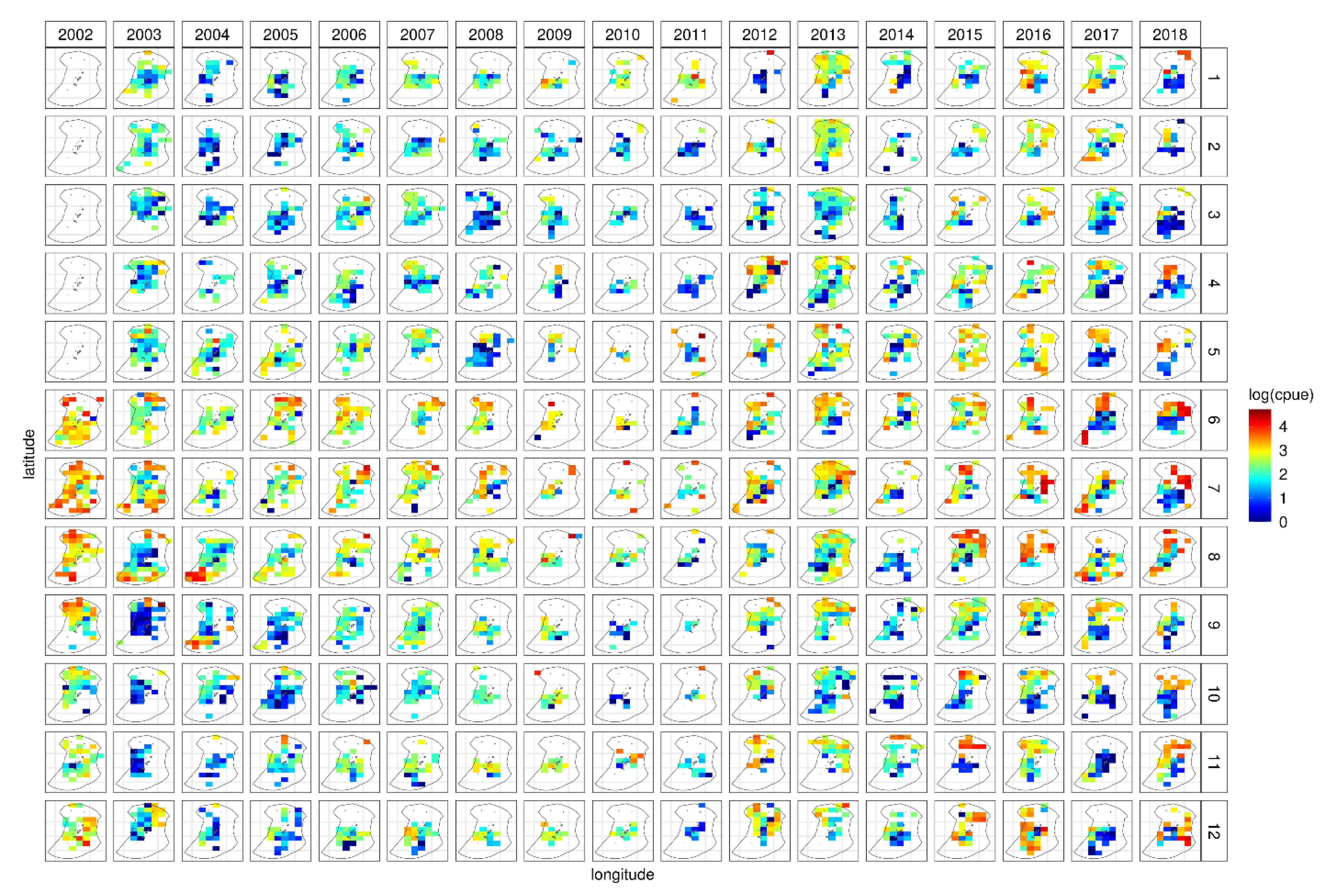

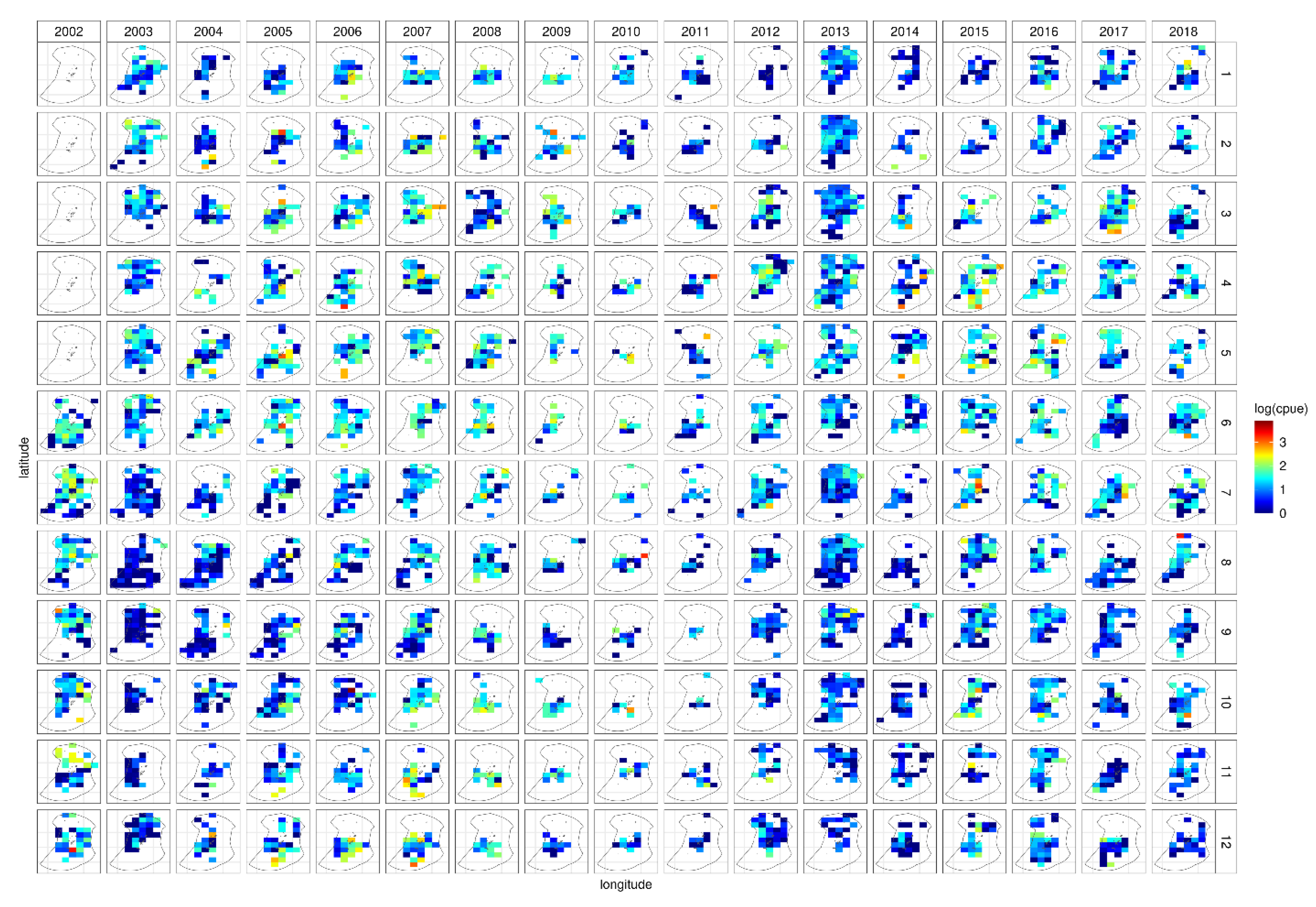

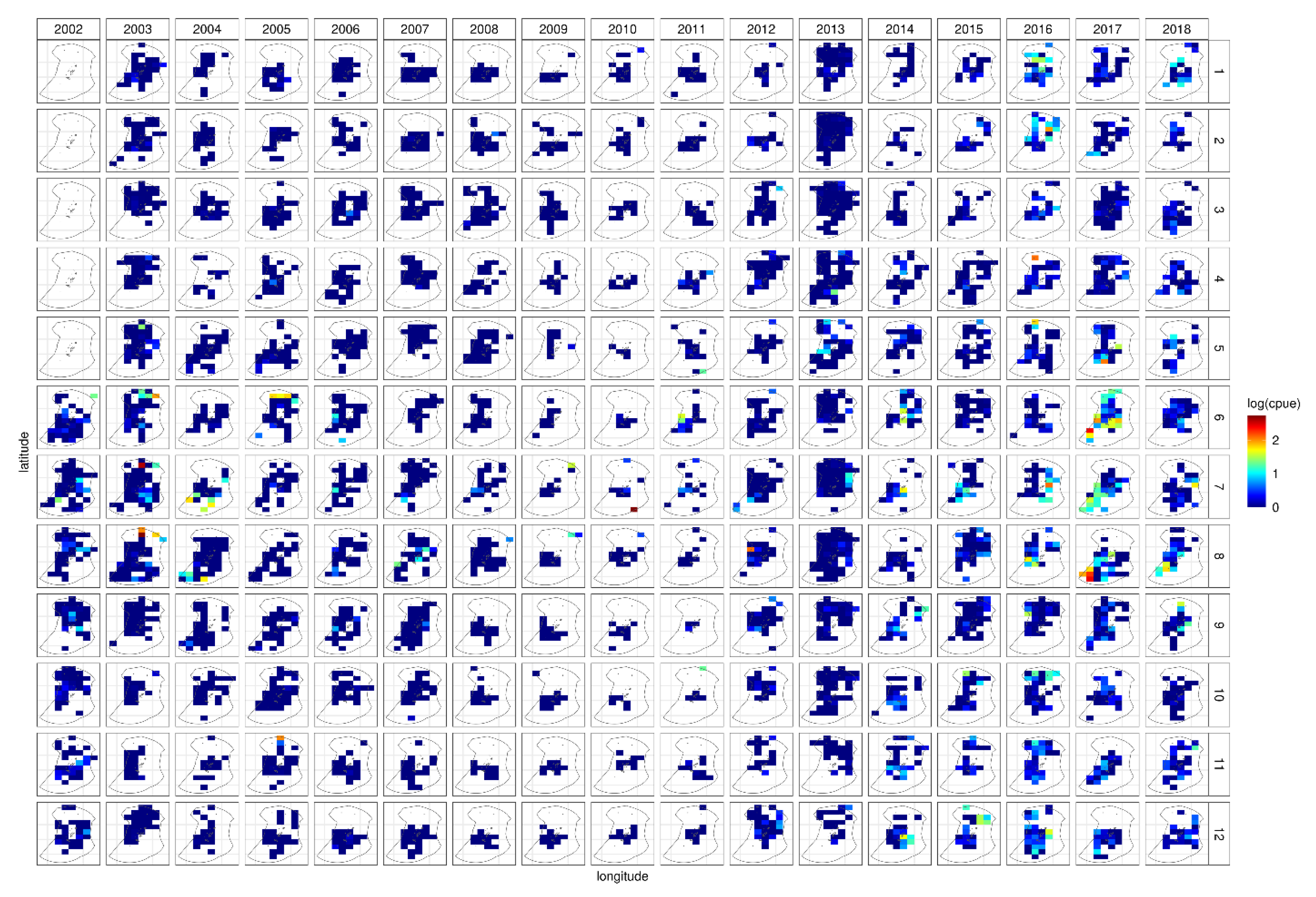

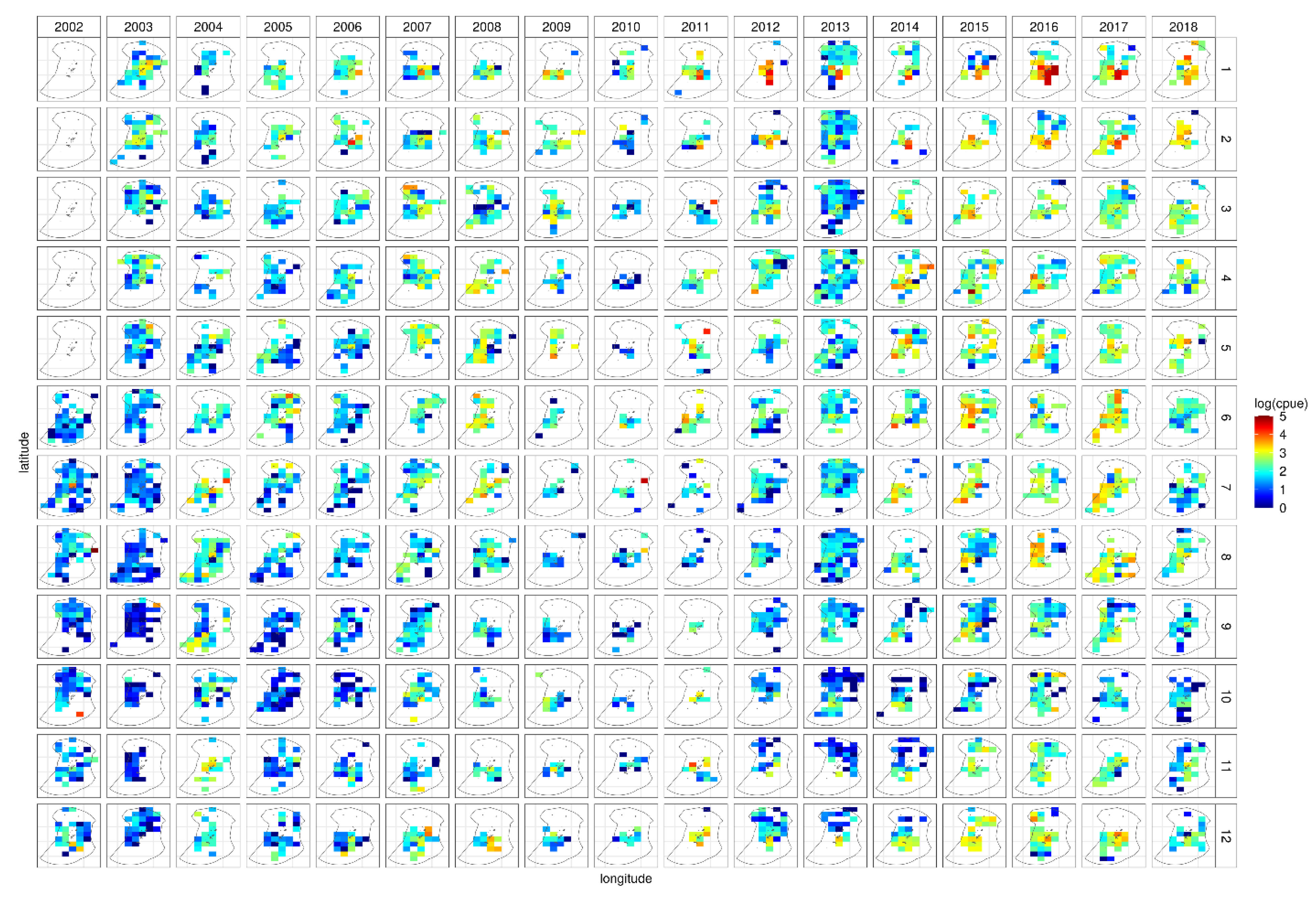

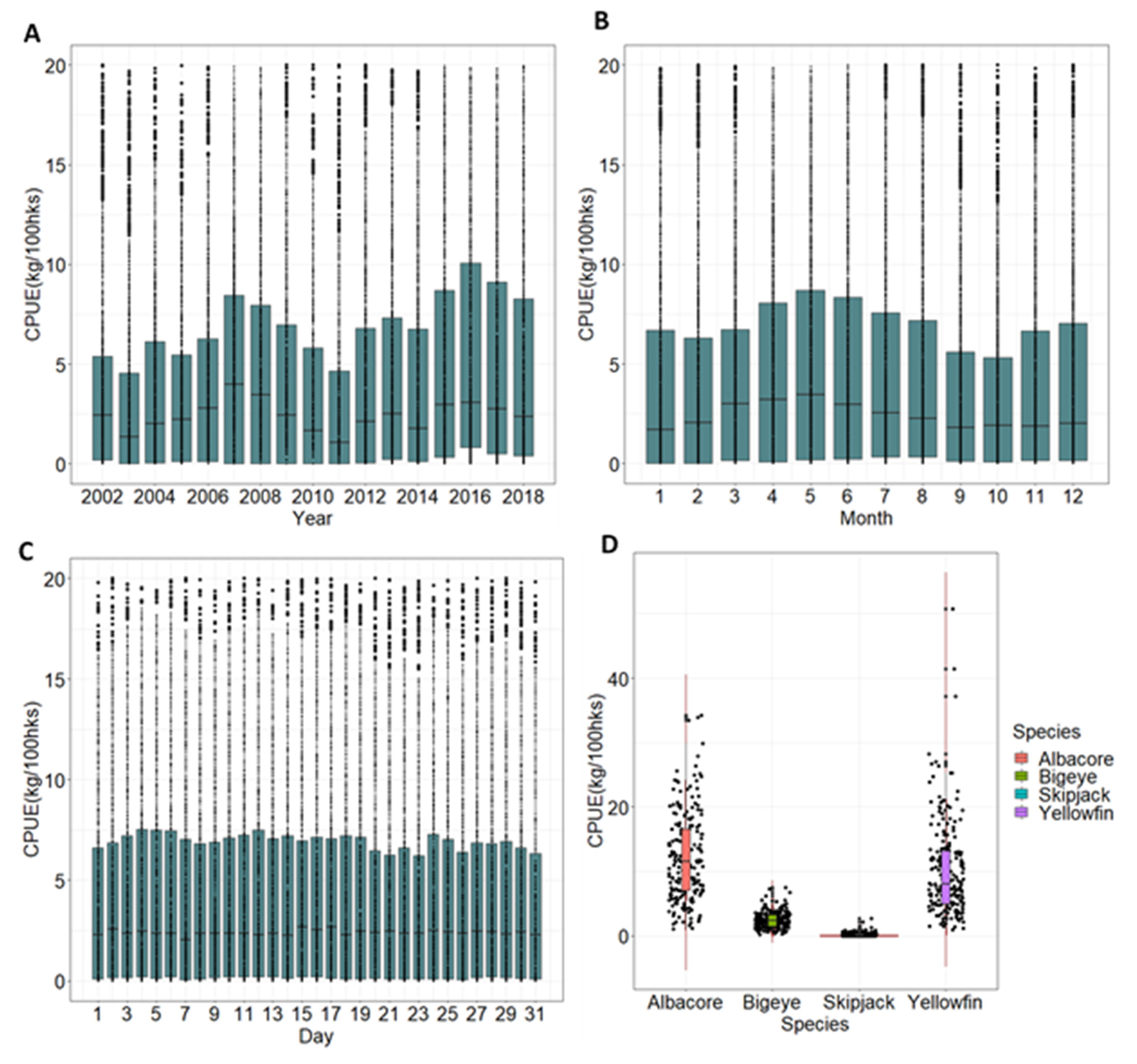

4.1. Spatio-temporal distribution of four main tuna species 2002–2018

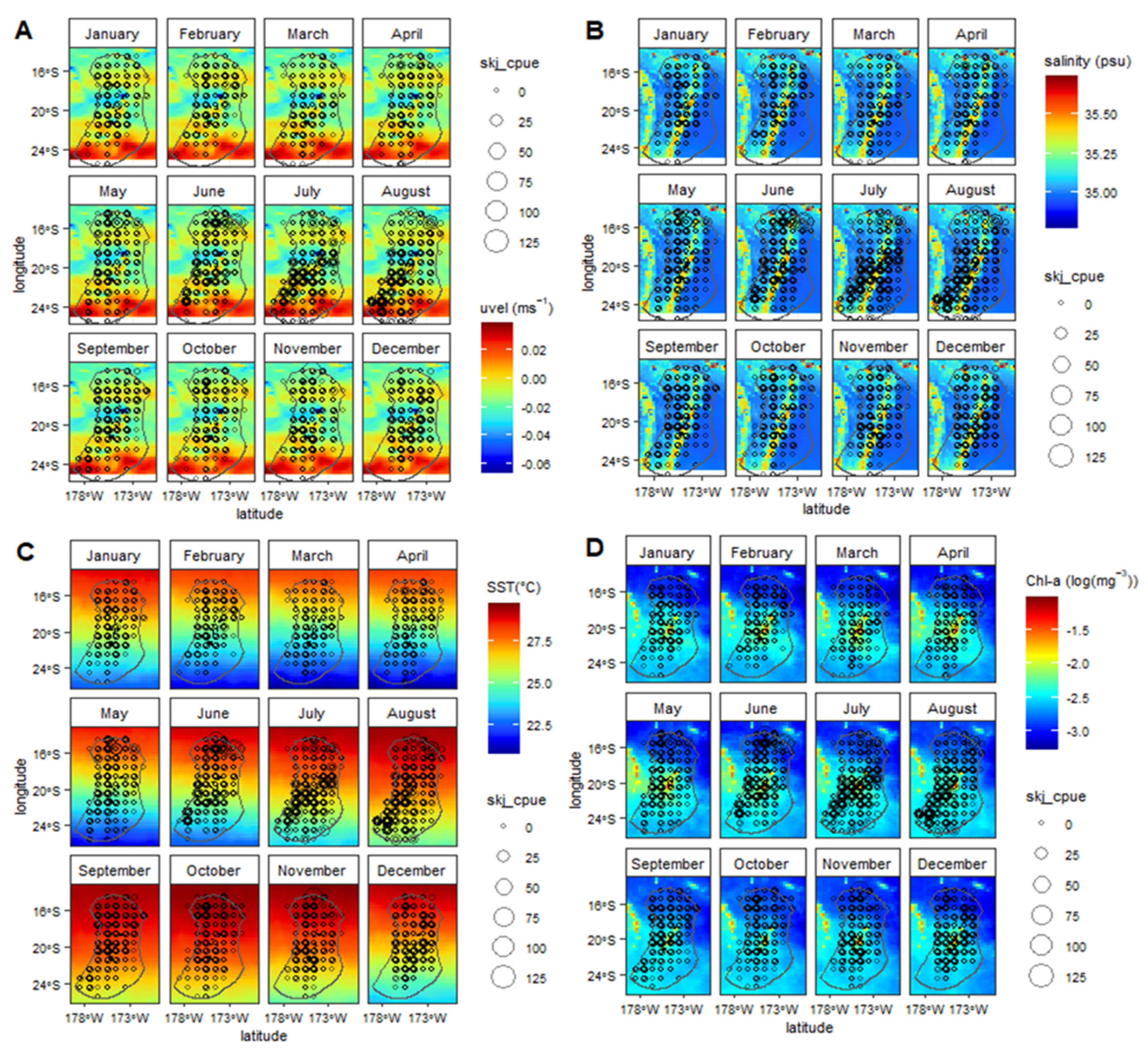

4.2. Tuna habitats in relation to biological and physical oceanic conditions

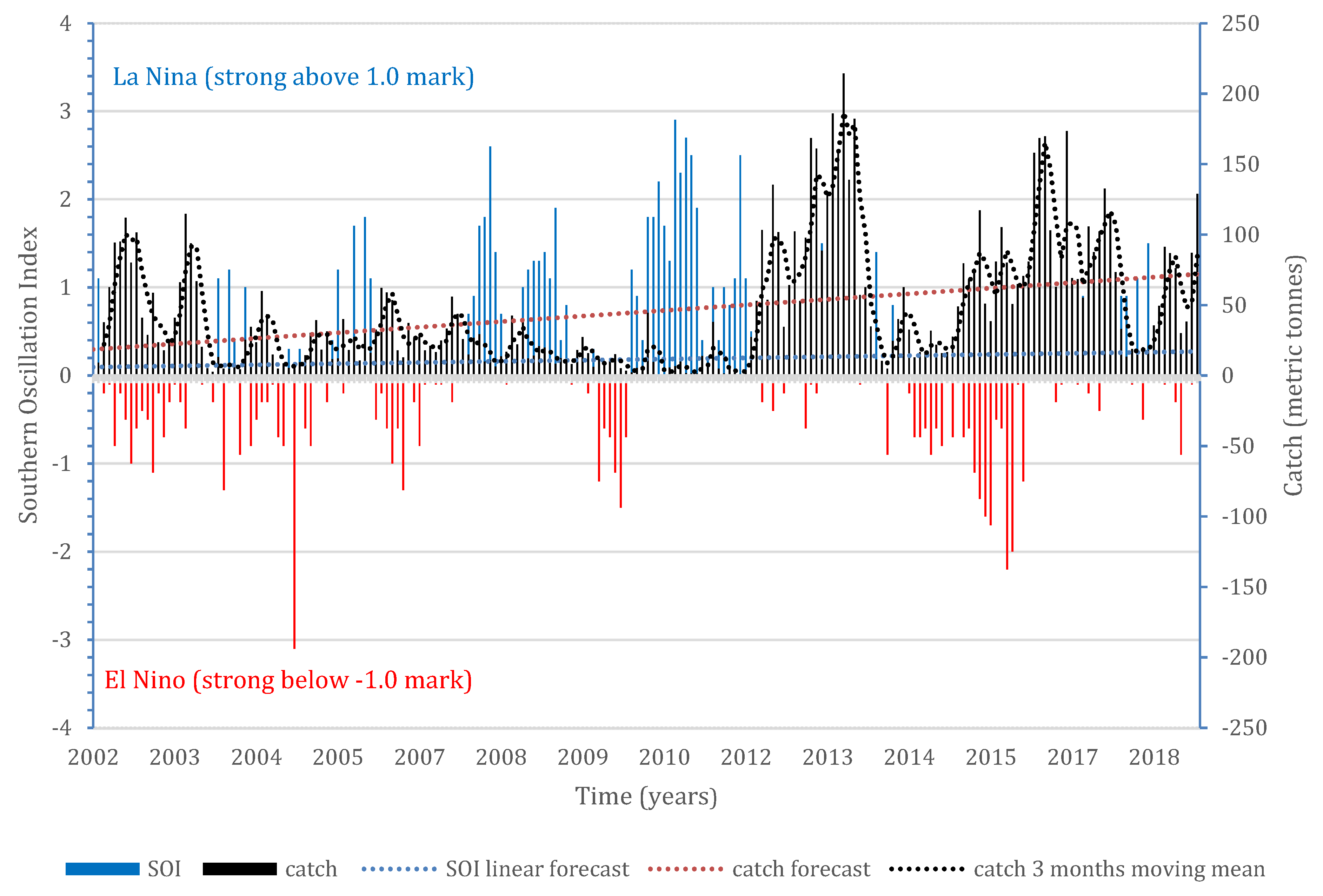

4.3. Tuna and climate variability

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barclay, K.,; Cartwright, I. Governance of tuna industries: The key to economic viability and sustainability in the western and central pacific ocean. Marine Policy, 2007, 31, 348–358. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. D.,; Kronen, M.,; Vunisea, A.,; Nash, W. J.,; Keeble, G.,; Demmke, A.,; Pontifex, S. Planning the use of fish for food security in the pacific. Marine Policy, 2009, 33, 64–76. [CrossRef]

- Havice, E. Rights-based management in the western and central pacific ocean tuna fishery: Economic and environmental change under the vessel day scheme. Marine Policy, 2013, 42, 259–267. [CrossRef]

- Bayliff, W. H. The fisheries for tunas in the eastern pacific ocean. In Advances in tuna aquaculture, 2016, 21–41. [CrossRef]

- MAFF, and FFA. 2018. Tonga tuna fishery framework 2018 - 2022. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry; Fisheries, Fishery Forum Agency, Nuku’alofa, Tonga.

- Ram-Bidesi, V.,; Tsamenyi, M. Implications of the tuna management regime for domestic industry development in the pacific island states. Marine Policy, 2004, 28, 383–392. [CrossRef]

- Havice, E. The structure of tuna access agreements in the western and central pacific ocean: Lessons for vessel day scheme planning. Marine Policy, 2010, 34, 979–987. [CrossRef]

- Dalzell, P.,; Kingma, E.,; Bailey, A. S.,; Ha, P.,; McGregor, M.,; Tosatto, M. D. Amendment 7 fishery ecosystem plan for pelagic fisheries of the western pacific region regarding the use and assignment of catch and effort limits of pelagic management unit species by the US pacific island territories and specification of annual bigeye tuna catch limits for the US pacific island territories: Including an environmental assessment and regulatory impact review, 2014, RIN 0648-BD46.

- McCoy, M. A. Regulation of transshipment by the western and central pacific fisheries commission: Issues and considerations for FFA member countries. Gillett, Preston; Associates. 2007.

- Langley, A.,; Hampton, J.,; Ogura, M. Stock assessment of skipjack tuna in the western and central pacific ocean. WCPFC SC1 SA WP-4. Bigeye tuna Yellowfin tuna. 2005.

- McIlgorm, A. Economic impacts of climate change on sustainable tuna and billfish management: Insights from the western pacific. Progress in Oceanography, 2010, 86, 187–191. [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, J.,; Haftel, S. Tuna management in the pacific: An analysis of the south pacific forum fisheries agency. U. Haw. L. Rev., 1981, 3: 1.

- Gillett, R.,; Lightfoot, C. The contribution of fisheries to the economies of pacific island countries. Asian Development Bank. 2001.

- Williams, P.,; Terawasi, P. Overview of tuna fisheries in the western and central pacific ocean, including economic conditions–2010. WCPFC-SC7-2011/GN WP-1. 2011.

- Bell, J. D.,; Allain, V., Allison, E. H.,; Andréfouët, S.,; Andrew, N. L.,; Batty, M. J.,; Blanc, M. Diversifying the use of tuna to improve food security and public health in pacific island countries and territories. Marine Policy, 2015, 51, 584–591. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, K.,; De Young, C., Soto, D.,; Bahri, T. Climate change implications for fisheries and aquaculture. FAO Fisheries and aquaculture technical paper, 2009, 530, 212.

- WCPFC. Overview of tuna fisheries in the western and central pacific ocean, including economic conditions. WCPFC-TCC13-2017-IP0, Rarotonga, Cook Is. 2017.

- Dagorn, L.,; Holland, K. N.,; Restrepo, V.,; Moreno, G. Is it good or bad to fish with FAD s? What are the real impacts of the use of drifting FAD s on pelagic marine ecosystems? Fish and fisheries, 2013, 14, 391–415. [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.,; Young, J.,; Nicol, S.,; Kolody, D.,; Allain, V.,; Bell, J.,; Brown, J. N. Optimising fisheries management in relation to tuna catches in the western central pacific ocean: A review of research priorities and opportunities. Marine Policy, 2015, 59, 94–104. [CrossRef]

- Link, J.S.,; Huse, G.,; Gaichas, S.,; Marshak, A.R. Changing how we approach fisheries: a first attempt at an operational framework for ecosystem approaches to fisheries management. Fish and Fisheries, 2020, 21, 393-434. [CrossRef]

- Morishita, J. What is the ecosystem approach for fisheries management?. Marine policy, 2008, 32, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Heenan, A.,; Pomeroy, R.,; Bell, J.,; Munday, P.L.,; Cheung, W.,; Logan, C.,; Brainard, R.,; Amri, A.Y.,; Aliño, P.,; Armada, N.,; David, L. A climate-informed, ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Marine Policy, 2015, 57, 182-192. [CrossRef]

- Yeeting, A. D.,; Bush, S. R.,; Ram-Bidesi, V.,; Bailey, M. Implications of new economic policy instruments for tuna management in the western and central pacific. Marine Policy, 2016, 63: 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Gillett, R.,; Tauati, M. I. Fisheries of the pacific islands: Regional and national information. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper: Food; Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018. 1–400.

- Kronen, M.,; Vunisea, A.,; Magron, F.,; McArdle, B. Socio-economic drivers and indicators for artisanal coastal fisheries in pacific island countries and territories and their use for fisheries management strategies. Marine Policy, 2010, 34, 1135–1143. [CrossRef]

- Sibert, J.,; Hampton, J. Mobility of tropical tunas and the implications for fisheries management. Marine Policy, 2003, 27: 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Gillett, R.,; McCoy, M.,; Rodwell, L.,; Tamate, J. Tuna: A key economic resource in the pacific islands. A report prepared for the asian development bank and the forum fisheries agency. In Tuna: A key economic resource in the pacific islands. A report prepared for the asian development bank and the forum fisheries agency. 2001.

- Miller, K. A. Climate variability and tropical tuna: Management challenges for highly migratory fish stocks. Marine Policy, 2007, 31, 56–70. [CrossRef]

- Kawaley, I. Implications of exclusive economic zone management and regional cooperation between south pacific small midocean island commonwealth territories. Ocean Development & International Law, 1999, 30, 333–377. [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.,; Fenner, D.,; LeBlanc, D.,; Vaisey, B.,; Purcell, I.,; Eliason, B. Tonga. In World seas: An environmental evaluation. 2019, 661-678.

- Arrizabalaga, H.,; Dufour, F.,; Kell, L.,; Merino, G.,; Ibaibarriaga, L.,; Chust, G.,; Irigoien, X.,; Santiago, J.,; Murua, H., Fraile, I.,; Chifflet, M. Global habitat preferences of commercially valuable tuna. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2015, 113, 102-112. [CrossRef]

- Polacheck, T. Tuna longline catch rates in the Indian Ocean: Did industrial fishing result in a 90% rapid decline in the abundance of large predatory species?. Marine Policy, 2006, 30, 470-482. [CrossRef]

- Methot Jr, R.D.,; Wetzel, C.R. Stock synthesis: a biological and statistical framework for fish stock assessment and fishery management. Fisheries Research, 2013, 142, 86-99. [CrossRef]

- Glaser, S. M.,; Ye, H., Maunder, M.,; MacCall, A.,; Fogarty, M.,; Sugihara, G. Detecting and forecasting complex nonlinear dynamics in spatially structured catch-per-unit-effort time series for north pacific albacore (thunnus alalunga). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2011, 68, 400–412. [CrossRef]

- Cornic, M.,; Rooker, J. R. Influence of oceanographic conditions on the distribution and abundance of blackfin tuna (thunnus atlanticus) larvae in the gulf of mexico. Fisheries Research, 2018, 201, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.-W.,; Shimada, T.,; Lee, M.-A.,; Su, N.-J.,; Chang, Y. Using remote-sensing environmental and fishery data to map potential yellowfin tuna habitats in the tropical pacific ocean. Remote Sensing, 2017, 9, 444. [CrossRef]

- Nurdin, S.,; Lihan, T.,; Mustapha, A. Mapping of potential fishing grounds of rastrelliger kanagurta (cuvier, 1816) in the archipelagic waters of spermonde indonesia using satellite images. In Malaysia geospatial forum. 2012.

- Rajapaksha, J.,; Samarakoon, L.,; Gunathilaka, A. Environmental preferences of yellowfin tuna in the northeast indian ocean: An application of satellite data to longline catches. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2013, 2, 72–80.

- Walters, C., and Maguire, J.-J. 1996. Lessons for stock assessment from the northern cod collapse. Reviews in fish biology and fisheries, 1996, 6, 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D. P.,; Hinton, M. G.,; Kohin, S.,; Armstrong, E. M.,; Snyder, S.,; O’Brien, F.,; Kiefer, D. K. The pelagic habitat analysis module for ecosystem-based fisheries science and management. Fisheries Oceanography, 2017, 26, 316–335. [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, M. D.,; Sambah, A. B.,; Miura, F.,; Tanaka, T.,; As-syakur, A. R. Characterization of bigeye tuna habitat in the southern waters off java–bali using remote sensing data. Advances in Space Research, 2015, 55: 732–746. [CrossRef]

- Keyl, F.,; Wolff, M. Environmental variability and fisheries: what can models do?. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 2008, 18, 273-299. [CrossRef]

- Mainuddin, M.,; Saiton, K.,; Saiton, S. Albacore fishing ground in relation to oceanographic conditions in the western north pacific ocean using remotely sensed satellite data. Fish Oceanogr, 2008,17, 61–73.

- Roandrianasolo Tsihoboto, M.,; John, B.,; Rijasoa, F. Analysis of environmental parameters effects on the spatial and temporal dynamics of tropical tuna in the EEZ of madagascar: Coupling remote sensing and catch data. Universidad de Alicante. Instituto Interdisciplinar para el Estudio del, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lumban-Gaol, J.,; Leben, R. R.,; Vignudelli, S.,; Mahapatra, K.,; Okada, Y.,; Nababan, B.,; Mei-Ling, M. Variability of satellite-derived sea surface height anomaly, and its relationship with bigeye tuna (thunnus obesus) catch in the eastern indian ocean. European Journal of Remote Sensing, 2015, 48, 465–477. [CrossRef]

- Polovina, J.J.,; Howell, E.A. Ecosystem indicators derived from satellite remotely sensed oceanographic data for the North Pacific. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2005, 62,, 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Novianto, D.,; Susilo, E. Role of sub surface temperature, salinity and chlorophyll to albacore tuna abundance in Indian Ocean. Indonesian Fisheries Research Journal, 2016, 22, 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Wiryawan, B.,; Loneragan, N.,; Mardhiah, U.,; Kleinertz, S.,; Wahyuningrum, P.I.,; Pingkan, J.,; Timur, P.S.,; Duggan, D.,; Yulianto, I. Catch per unit effort dynamic of yellowfin tuna related to sea surface temperature and chlorophyll in Southern Indonesia. Fishes, 2020, 5, 28. [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, R.,; Zainuddin, M.,; Putri, A. R. S. Skipjack tuna (katsuwonus pelamis) catches in relation to chlorophyll-a front in bone gulf during the southeast monsoon. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation, 2009, 12, 209–218.

- Yen, K.W.,; Lu, H.J.,; Chang, Y.,; Lee, M.A. Using remote-sensing data to detect habitat suitability for yellowfin tuna in the western and central pacific ocean. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2012, 33, 7507–7522. [CrossRef]

- Maravelias, C. D. Habitat selection and clustering of a pelagic fish: Effects of topography and bathymetry on species dynamics. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1999, 56, 437–450. [CrossRef]

- Nishida, T.,; Mohri, M.,; Itoh, K.,; Nakagome, J. Study of bathymetry effects on the nominal hooking rates of yellowfin tuna (thunnus albacares) and bigeye tuna (thunnus obesus) exploited by the japanese tuna longline fisheries in the indian ocean. In IOTC proceedings, 2001, 191–206.

- Teo, S. L.,; Block, B. A. Comparative influence of ocean conditions on yellowfin and atlantic bluefin tuna catch from longlines in the gulf of mexico. PLoS One, 2010, 5, e10756. [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.W.,; Shimada, T.,; Lee, M.A.,; Su, N.J.,; Chang, Y. Using remote-sensing environmental and fishery data to map potential yellowfin tuna habitats in the tropical pacific ocean. Remote Sensing, 2017, 9, 444. [CrossRef]

- Solanki, H.,; Prakash, P.,; Dwivedi, R.,; Nayak, S.,; Kulkarni, A.,; Somvamshi, V. Synergistic application of oceanographic variables from multi-satellite sensors for forecasting potential fishing zones: Methodology and validation results. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2010, 31, 775–789. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021, https://www.R-project.org/. (Accessded March 24, 2019).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2016, Springer-Verlag New York.

- Wickham, H.,; François, R.,; Henry, L.,; Müller, K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. 2022, https://dplyr.tidyverse.org, https://github.com/tidyverse/dplyr. (Accessed June 12, 2019).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Sea surface temperature & Sea surface Chlorophyll, 2021,.

- Robinson, J.,; Guillotreau, P.,; Jiménez-Toribio, R.,; Lantz, F.,; Nadzon, L.,; Dorizo, J.,; Gerry, C. Impacts of climate variability on the tuna economy of seychelles. Climate Research, 2010, 43, 149–162. [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.,; Dawson, T; Harrison, P.,; Pearson, R. Modelling potential impacts of climate change on the bioclimatic envelope of species in britain and ireland. Global ecology and biogeography, 2002, 11, 453–462.

- Bertrand, A.,; Lengaigne, M.,; Takahashi, K.,; Avadi, A.,; Poulain, F.,; Harrod, C. El niño southern oscillation (ENSO) effects on fisheries and aquaculture. Food & Agriculture Org. 2020.

- Beuttler, C.,; Charles, L.,; Wurzbacher, J. The role of direct air capture in mitigation of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Frontiers in Climate, 2019, 1, 10. [CrossRef]

- Albouy, C.,; Delattre, V.,; Donati, G.,; Frölicher, T. L.,; Albouy-Boyer, S.,; Rufino, M.,; Pellissier, L. Global vulnerability of marine mammals to global warming. Scientific reports, 2020, 10: 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Brierley, A.S.,; Kingsford, M.J. Impacts of climate change on marine organisms and ecosystems. Current biology, 2009, 19, R602-R614. [CrossRef]

- Hartoko, A.,; Suradi, W.,; Ghofar, A. Impact of climate variability on skipjack tuna (katsuwonus pelamis) catches in the indonesian fisheries management area (FMA) 715. In IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science, 2021, 012003. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.,; Wan, R., Cao, J.,; Xu, L.,; Wang, X.,; Zhu, J. Spatial variability of bigeye tuna habitat in the pacific ocean: Hindcast from a refined ecological niche model. Fisheries Oceanography, 2021, 30, 23–37. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.,; Yeh, S.-W.,; Kim, J.-H.,; Kug, J.-S.,; Kwon, M. The unique 2009–2010 el niño event: A fast phase transition of warm pool el niño to la niña. Geophysical Research Letters, 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.,; Fedorov, A. V. The extreme el niño of 2015–2016 and the end of global warming hiatus. Geophysical Research Letters, 2017, 44, 3816–3824. [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Rodriguez, A.,; Weeks, S. J.,; Berkelmans, R.,; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.,; Lough, J. M. Climate variability of the great barrier reef in relation to the tropical pacific and el nino-southern oscillation. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2012, 63, 34–47. [CrossRef]

- Syamsuddin, M. L.,; Saitoh, S.-I.,; Hirawake, T.,; Bachri, S.,; Harto, A. B. Effects of el niño–southern oscillation events on catches of bigeye tuna (thunnus obesus) in the eastern indian ocean off java. Fishery Bulletin, 2013, 111, 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Vaihola, S., Kininmonth, S. Climate Change Potential Impacts on the Tuna Fisheries in the Exclusive Economic Zones of Tonga. Diversity, 2023, 15, 844. [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.W.,; Evans, K.,; Lee, M.A. Effects of climate variability on the distribution and fishing conditions of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the western Indian Ocean. Climatic Change, 2013, 119, 63-77. [CrossRef]

- Lehodey, P.,; Senina, I.,; Calmettes, B.,; Hampton, J.,; Nicol, S. Modelling the impact of climate change on Pacific skipjack tuna population and fisheries. Climatic change, 2013, 119, 95-109. [CrossRef]

- Senina, I.,; Lehodey, P.,; Calmettes, B.,; Dessert, M.,; Hampton, J.,; Smith, N.,; Gorgues, T.,; Aumont, O.,; Lengaigne, M.,; Menkes, C.,; Nicol, S. Impact of climate change on tropical Pacific tuna and their fisheries in Pacific Islands waters and high seas areas. 14th Regular Session of the Scientific Committee of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, WCPFC-SC14. 2018.

| No. of longline vessels | Catch size (metric tons) | CPUE (no. of fish/100 hooks/year) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total no. of hooks | Domestic | Foreign | Albacore | Bigeye | Skipjack | Yellowfin | Albacore | Bigeye | Skipjack | Yellowfin | ||

| 2002 | 38526 | 17 | - | 740 | 124 | 4 | 170 | 30890 | 5097 | 209 | 6918 | ||

| 2003 | 46622 | 23 | - | 489 | 76 | 15 | 240 | 19164 | 2702 | 754 | 8686 | ||

| 2004 | 26348 | 20 | - | 237 | 47 | 3 | 208 | 10607 | 2120 | 166 | 9215 | ||

| 2005 | 28521 | 13 | - | 235 | 78 | 3 | 123 | 10290 | 3609 | 163 | 5653 | ||

| 2006 | 33818 | 11 | - | 383 | 83 | 2 | 176 | 15835 | 3859 | 101 | 7439 | ||

| 2007 | 31347 | 12 | - | 336 | 109 | 1 | 278 | 14518 | 4967 | 43 | 12314 | ||

| 2008 | 22432 | 9 | - | 227 | 72 | 0 | 248 | 10355 | 3441 | 19 | 11118 | ||

| 2009 | 11112 | 6 | - | 146 | 33 | 1 | 97 | 7444 | 1776 | 49 | 5308 | ||

| 2010 | 6927 | 6 | - | 105 | 19 | 1 | 40 | 4348 | 1064 | 35 | 2513 | ||

| 2011 | 8703 | 3 | - | 88 | 14 | 2 | 142 | 3170 | 824 | 72 | 6960 | ||

| 2012 | 48766 | 4 | - | 829 | 126 | 4 | 379 | 19846 | 2976 | 121 | 11488 | ||

| 2013 | 109494 | 3 | 19 | 1583 | 230 | 9 | 640 | 36947 | 5477 | 210 | 17078 | ||

| 2014 | 31357 | 4 | 19 | 284 | 40 | 8 | 378 | 8742 | 1484 | 305 | 14785 | ||

| 2015 | 45302 | 4 | 14 | 724 | 129 | 13 | 755 | 19822 | 4104 | 364 | 23191 | ||

| 2016 | 58498 | 4 | 4 | 1265 | 159 | 31 | 895 | 32618 | 4457 | 943 | 28260 | ||

| 2017 | 55438 | 6 | 8 | 874 | 129 | 41 | 871 | 23328 | 3740 | 1290 | 29104 | ||

| 2018 | 30186 | 6 | 4 | 677 | 63 | 12 | 336 | 21489 | 2486 | 485 | 13895 | ||

| Total allowable catches for each species (metric tons) | 2500 | 2000 | Unlimited* | 2000 | Manage through WCPFC harvest strategic plan and TMDP | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).