1. Introduction

Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) are mitochondrial membrane-bound FAD-dependent enzymes that cataly

ze the oxidative deamination of biogenic amines, in particular monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine [

1]. The two enzyme isoforms, monoamino oxidase A (MAO A) and monoamino oxidase B (MAO B) are characterized by different substrate and inhibitor specificity. MAOs are more common inside neurons and astroglial cells as part of the central nervous system (CNS), but they are also present in other organs. MAO A is preferentially expressed in the gastrointestinal tract, lung, liver, and placenta, while MAO B is found in the platelets [

2].

Being involved in the catabolism of neurotransmitters, MAOs are well-known pharmacological targets in brain disorders. Several MAO inhibitors (MAOI) have reached the clinical approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder and Parkinson’s disease, as they promote the increase in the monoamine neurotransmitters level. [

3,

4]. Moreover, the therapeutic potential of MAOI appears more valuable because an over-activity of MAOs can lead to an increased production of harmful species, such as aldehydes and hydrogen peroxide [

2]. Thus, the overexpression of MAO and upregulation of its activity, which has been found in age-associated diseases, was suggested to contribute to the development of oxidative and inflammatory stress. This condition has been recently linked to the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases, from neurodegenerative to cardiovascular disorders, and cancer [

5].

MAOs have been recently found highly expressed in different type of cancers [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In particular, various studies have demonstrated a correlation between MAO A expression and the percent of high grade prostate cancer [

11,

14,

15]. Patients with recurring castrate-sensitive prostate cancer have shown a significant measurable decline in the prostate specific antigen after treatment with the irreversible non-selective MAO A/B inhibitor phenelzine [

16]. Additionally, overexpression of MAO A was found in glioblastoma [

17] and MAO A has also been suggested to contribute to the progression on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) due to its role in regulating the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, a key step in cancer invasion and metastasis [

10,

18]. Similarly MAO B was found overexpressed in glioblastoma [

12,

19] and in colorectal cancer [

20]. Therefore, this novel role for “old enzymes” is opening new frontiers for MAOs inhibitors, as potential antiproliferative agent [

21,

22,

23,

24].

In the last years we focused our studies on polyamine derivatives as novel type of MAO inhibitors. Indeed, the polyamine skeleton represents a “universal template” since the insertion of appropriate moieties on amine groups and the kind of linker between them can modulate selectivity and affinity toward a given receptor or enzyme [

25,

26]. This approach allowed us to discover, among others, the selective antimuscarinic tetramine methoctramine (1) and the irreversible antiadrenergic tetramine disulfide benextramine [

25]. Furthermore, some polyamine analogs have been designed to hit targets involved in cancer growth (from DNA, to enzymes involved in the polyamine metabolism and receptor [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]), and other types of analogues were developed to hit targets involved in multifactorial neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [

25,

34].

Recently we have also proved and highlighted that some polyamine based analogues can inhibit human amine oxidases, in particular the human MAOs [

35,

36]. In our previous studies we have demonstrated that a decrease in the flexibility of the inner polymethylene chain of compound

1, as in its dipiperidine analog

2, is favorable for MAO B inhibitory activity. On this basis, by searching for novel compounds endowed with both MAOs inhibitory potency and antiproliferative activity, we selected a small in house library of polyamine analogs (

3-

7) structurally related to compound

2. These analogs are characterized by constrained linkers between the inner amine functions of the polyamine backbone, with the aim to highlight the role of these substitutions towards inhibitory potency. In the present study, the MAO inhibitory activity linked to the antiproliferative potential of compounds

2-

7 was investigated. Two of these analogues (

4 and

5) were found to join these activities, demonstrating remarkable antiproliferative activity in several cell lines, particularly in glioma.

2. Results

2.1. Rational of compound selection

Recently, we have reported a series of synthetic polyamines as new MAO inhibitors [

35,

36]. In particular, a spermine analogue previously designed to act as a muscarinic cholinergic M2 receptor antagonist [

34], emerged as active and reversible mixed type MAO-B inhibitor.

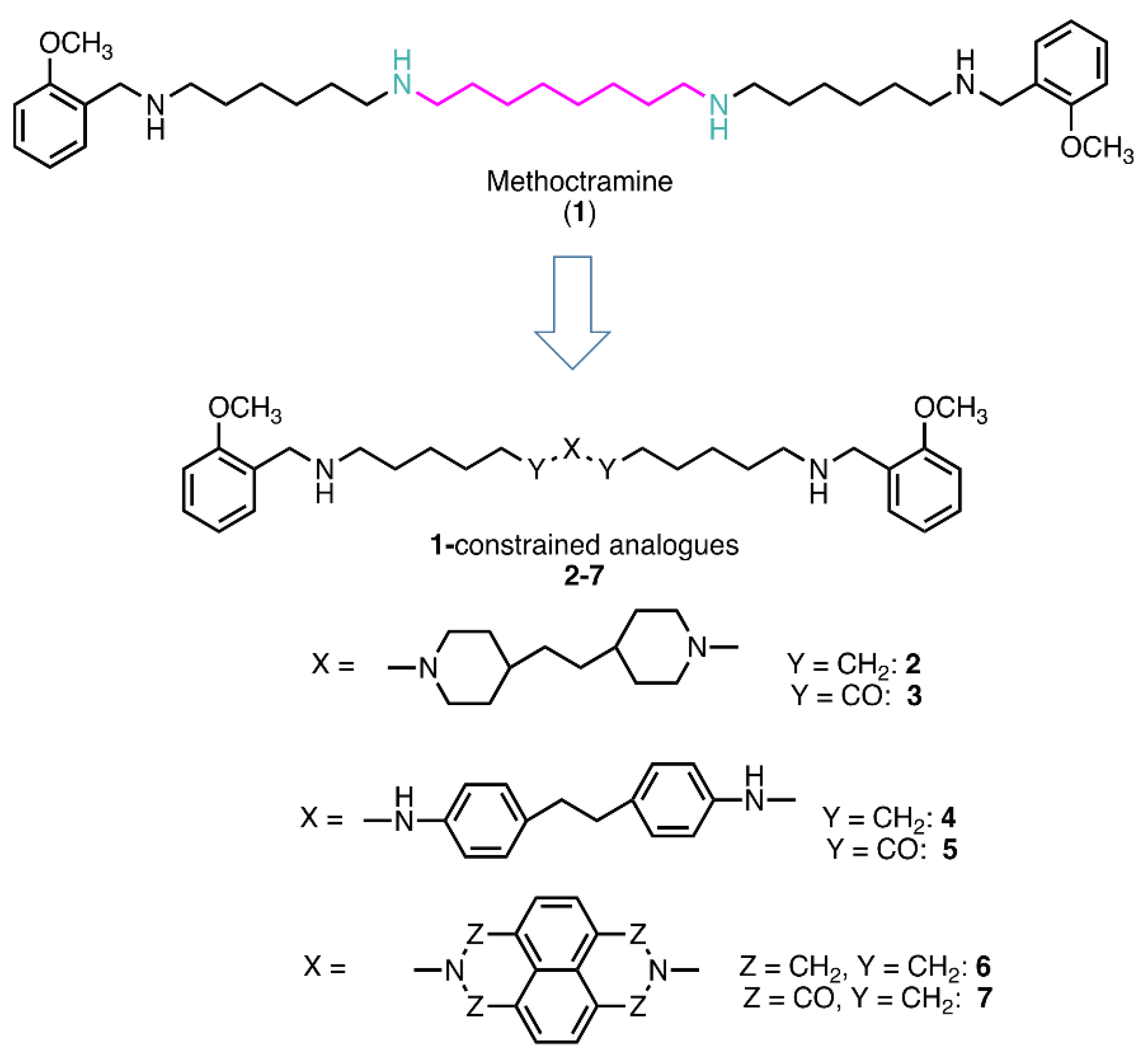

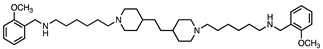

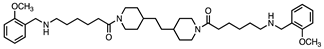

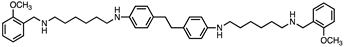

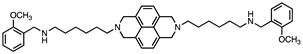

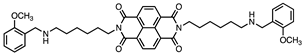

Based on this and given our interest in discovering new MAO inhibitors, we focused our attention on the dipiperidine analog of compound

1, the polyamine

2. [

25]. Thus, in this study we have evaluated compound

1 and the structurally related in-house constrained analogues

2-

7 as human MAO inhibitors. From a chemical point of view, compounds

2-

7 are characterized by conformationally-restricted moieties between the inner nitrogen atoms of the polyamine skeleton respect to the flexible inner 8-carbon chain of compound

1 (

Figure 1). In detail, the flexible linker has been replaced with dipiperidine (compounds

2 [

34] and

3 [

34], or dianiline (compounds

4 [

34] and

5 [

34] moiety or naphthalene diimide related rings (compounds

6 and

7 [

37]). It is worth noting that compounds

2,

4 and

6 are characterized by basic inner nitrogens while compounds

3,

5 and

7, bearing the corresponding amide or imide functional groups, are characterized by non-basic inner nitrogens.

2.2. Effect of the polyamine derivatives 2-7 on the activity of amine oxidases.

2.2.1. Inhibitory activity of the compounds on human recombinant MAOs

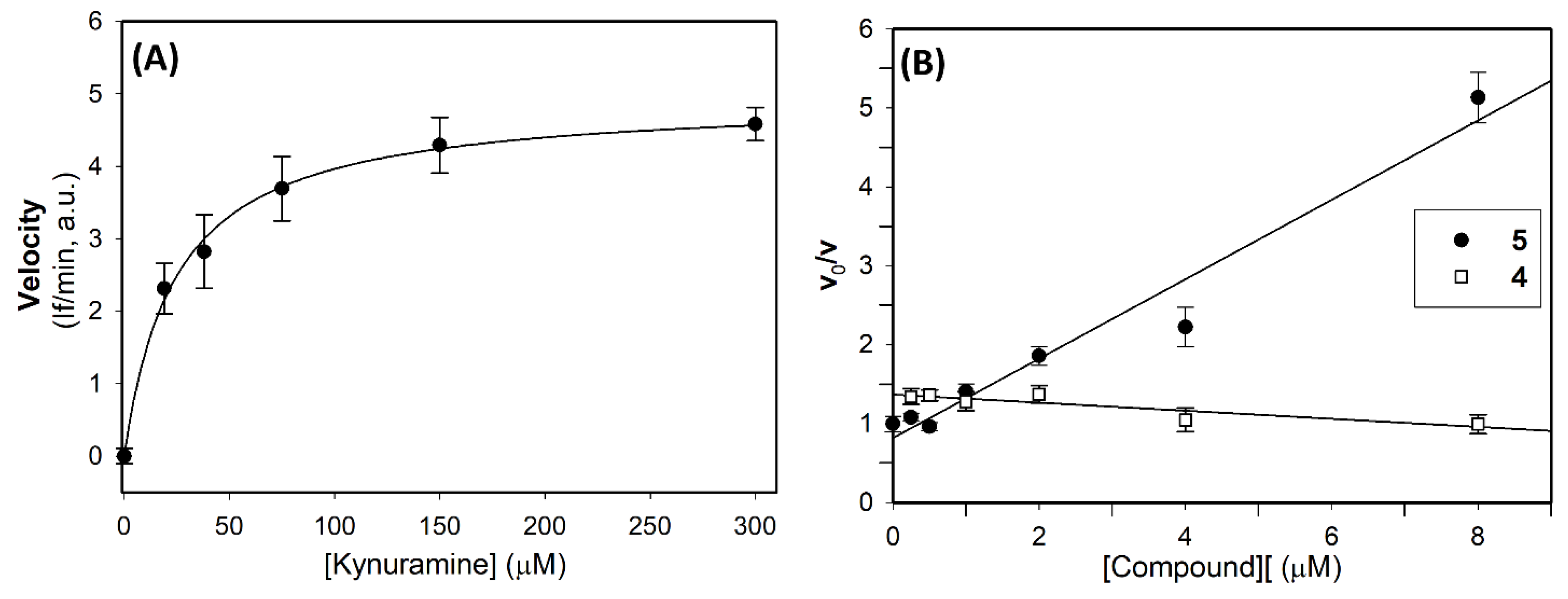

Before evaluating the potential MAO inhibitory capability of derivatives 2-7, kinetic experiments were performed to assay their behavior as potential MAOs substrates, by using the Amplex-red/Horse radish peroxidase coupled assay, which detects the hydrogen peroxide produced by the amine oxidase enzyme activity in the presence of an amine substrate. Compounds 2,3, 5-7 (tested up to 50 μM concentration) did not act as substrates, while 4 was not tested because of interferences with the assay method. Thus, for the subsequent inhibition studies, the assay method that uses kynuramine as MAO substrate and detect the production of 4-hydroxyquinoline, (forming from the aldehyde reaction product) was applied.

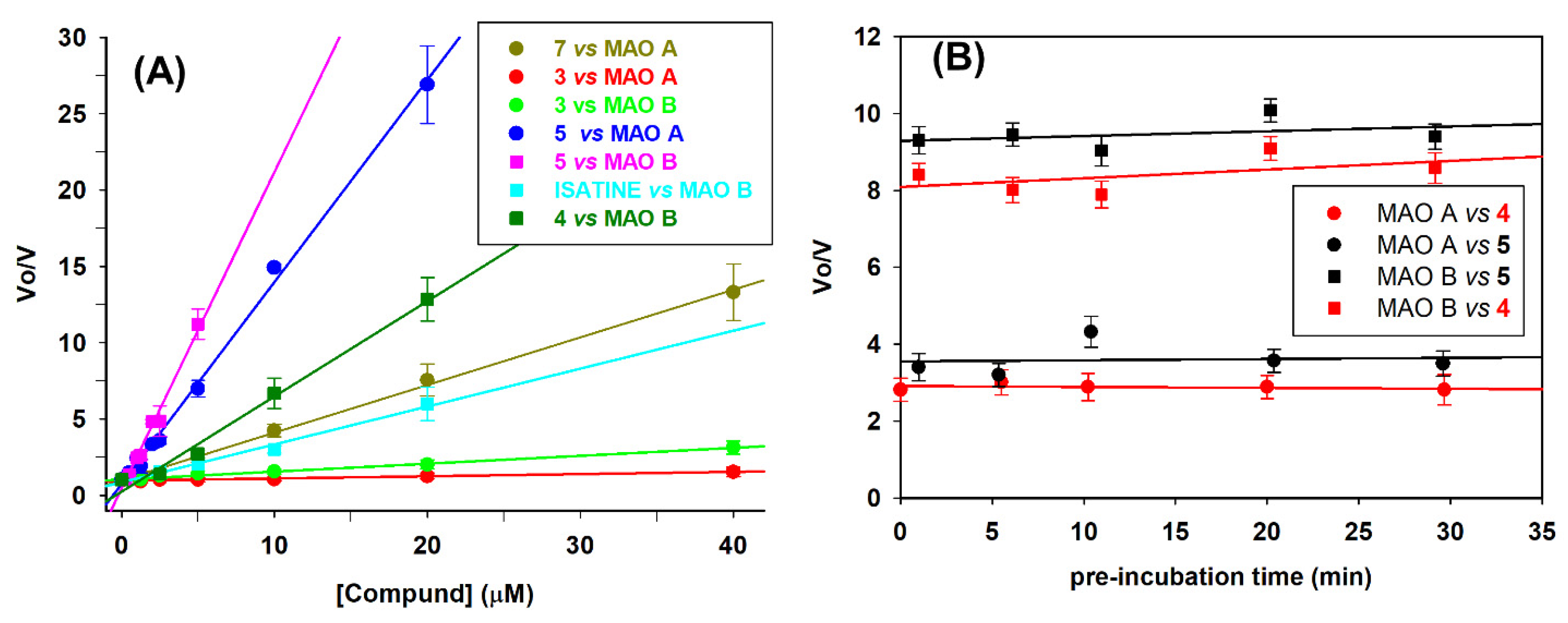

The effect of the derivatives

2-

7 on MAO activity was assessed using the human recombinant enzymes and compound concentrations in the range 1.25-40 μM. Isatine, harmine and safinamide, were evaluated as known competitive MAO inhibitors, while compound

1, was taken as the reference molecule. [

38,

39,

40]. For this initial kinetic screening, the substrate (kynuramine) was used at a concentration (10 μM) lower than the K

M value (K

M = 32± 11μM for MAO A and K

M =27± 4 μM MAO B). This experimental condition was chosen because, according to our earlier study [

35], compound

2 mostly acted as a competitive inhibitor, thus affecting mainly K

M rather than V

max. Consequently, under the selected experimental conditions of [S]=10μM < K

M, the ratio of the initial rate of reaction in absence (V

o) and in presence (V

I) of the tested compound (V

o/V

I ), can be roughly simplified to the ratio of (V

max/ K

M )

o/(V

max/ K

M )

I ≈ (1+ [I]/Ki). Plotting the ratio (V

o/V

I) against the compound concentration, a linear dependence of V

o/V

I on the inhibitor concentration is obtained and Ki values can be calculated. This behavior was confirmed (see

Figure 2A as example), as the ratio (V

o/V

I ) increases linearly with concentration of all tested compounds (r>0.99). From the slope values (1/Ki), calculated by the linear regression analysis, the inhibition constant (Ki) values of the tested compounds for both MAO A and MAO B were calculated, along with the selectivity index SI, that is the ratio Ki

MAOA:Ki

MAOB (

Table 1).

As showed in

Table 1, the insertion of a less flexible chain into compound

1 scaffold leads to the appearance of an inhibitory effect on both isoenzymes, which seems strongly dependent on the nature of the linker. Specifically, for

2, characterized by a dipiperidine moiety instead of the flexible 8-carbon chain between the inner nitrogen atoms, only a slight increase of MAO B inhibition is observed, while none appreciable effect was obtained towards MAO A (confirming our previous data [

34]. The replacement of the inner dipiperidine moiety of

2, with a dianiline, as in

4, improves the inhibitory ability of the polyamine scaffold against both MAO isoforms. Indeed, the Ki value calculated for MAO B, decreased of more than two order of magnitudes, with K i= 0.3 μM and higher than 330 μM, for

4 vs

2, respectively. Compound

4 showed a remarkable inhibition towards MAO A (Ki = 0.9 μM), in contrast with

2 that is basically inactive on this isoform (Ki = 247 μM). The modification of the inner amine groups in amide functions has a further slight positive effect in ameliorating the inhibitory potency, as assessed by the lowering in Ki values of

3 vs

2 and

5 vs

4.

Otherwise, the replacement of the inner dipiperidine moiety (2) with a more rigid and bulky naphtalentetracarboxylic diimmide core (7), resulted in a derivative that maintains the ability to interact with both the MAO isoforms, even if with less potency than 5 (7, Ki = 3-4 μM, and 5 Ki< 1 μM). It is important to point out that modifying the basic inner nitrogen atoms of 6 in imide functions, as in 7, determined an increase in the inhibitory capability (Ki increased from 5 to 10 times).

2.2.2. Mechanism of inhibition

To understand the mechanism of inhibition, additional investigations were focused on the most potent inhibitors

4 and

5. First, we evaluated the possibility of a time-dependence inhibition. For this purpose, the residual MAO activity was determined after pre-incubation of both the human recombinant MAO A and MAO B with 2.5 μM concentration of

4 and

5 at different time points (0 to 30 minutes), before adding kynuramine 10 μM as substrate. For both the compounds no time dependence of inhibition was observed. Indeed, the Vo/Vi ratio did not change in the explored time range, that is it did not increase (

Figure 2B).

Then, the reversilbility of the inhibition was verified. With this aim MAO A and MAO B were incubated with compounds 4 or 5 (5μM ) and after 15 sand 25 min the enzyme-inhibitor complexes were diluted 50 times and enzyme activity assay was performed under substrate saturation condition (300 μM kynuramine). The recovered enzyme activity was not significant different in comparison to the control sample (in absence of inhibitor), confirming the full reversibilty of the inhibition of MAO activity by this type of polyamine analogues (data not shown).

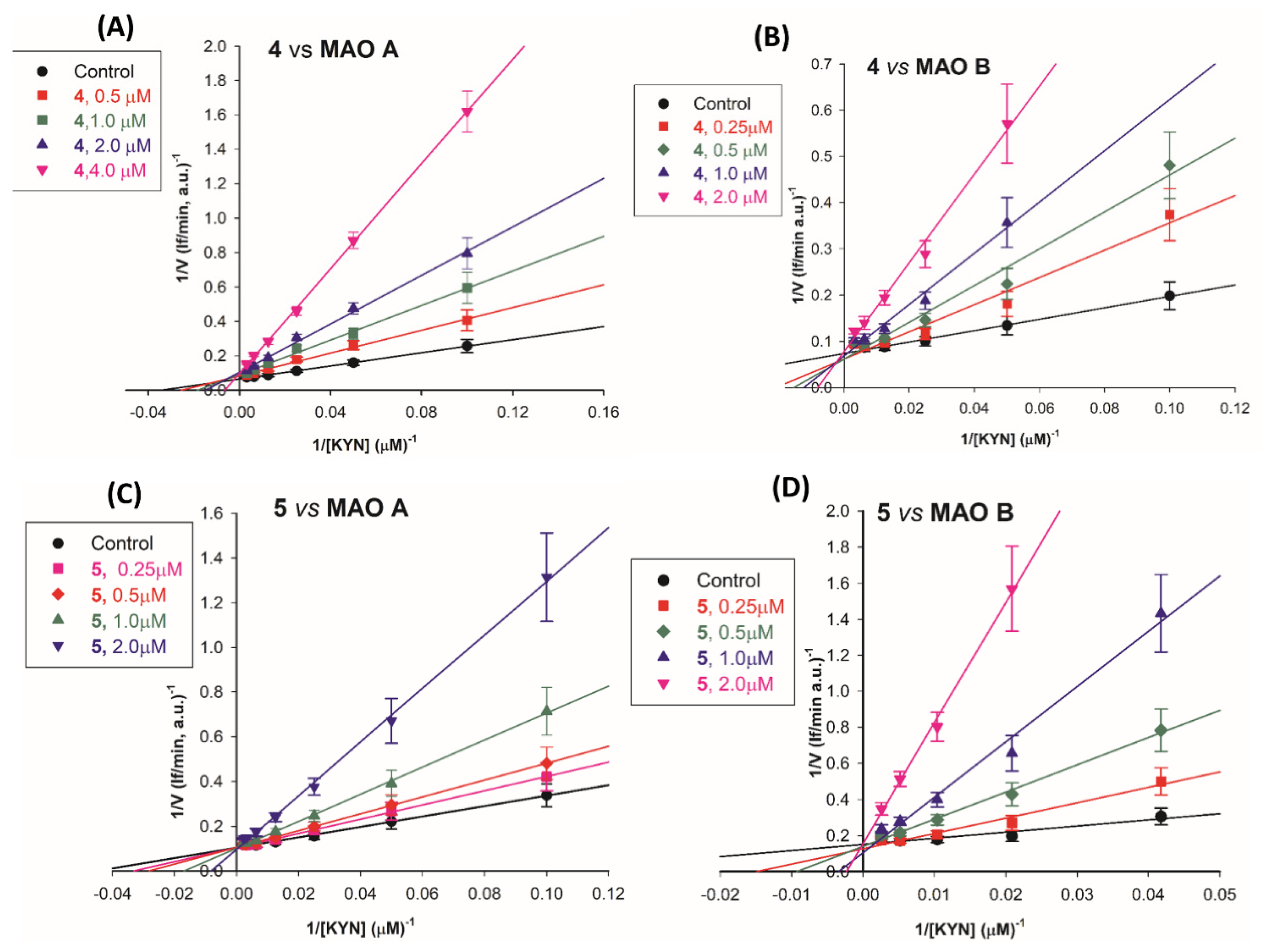

To further clarify the mechanism of inhibition, the kinetic parameters, K

M and V

max of the human recombinant MAO A and MAO B were determined in the presence of various concentrations of compounds

4 or

5 (0.25 -2 μM). Kynuramine was used as substrate. The global fit analysis (Software GraphPad Prism 9.0) of the experimental data (velocity

vs substrate concentration, at the various inhibitor concentrations) was applied by testing the equations for competitive, mixed, non-competitive and uncompetitive inhibition models. The mixed model fit gave the highest r

2 value, with a dissociation constant value for the enzyme-substrate complex (K

IES) at least 17 times higher in comparison to the inhibition constants (

KI) for the free enzyme. Therefore, these compounds interact preferentially with the active site of free enzyme (MAO A or MAO B) in competition with the substrate. In details the following inhibition constant values were obtained: for

5, Ki =0.16±0.04μM and K

IES= 6±1 μM

versus MAO B ( r

2>0.96) and Ki =0.62±0.09 μM and K

IES= 14±2 μM

versus MAO A ( r

2>0.99); for

4, Ki =0.31±0.05 μM and K

IES= 15±2 μM

versus MAO B (r

2>0.97) and Ki =0.62±0.11 μM and K

IES= 11±2 μM

versus MAO A (r

2>0.99). These Ki values are in good agreement with those reported in

Table 1.

This behavior of a primary competitive inhibitor can be better visualized by the double reciprocal or Lineweaver-Burk plots (1/v

vs 1/S,) of the kinetic data for MAO A and MAO B in the presence of the various concentrations of the inhibitors

4 (

Figure 3A and 3B) and

5 (

Figure 3C and 3D). These plots clearly demonstrate that the compounds mostly affected the intercept on the x-axis (-1/K

M), while the intercept on the y-axis (1/V

max) just marginally increased at the highest concentrations of the inhibitors

5 and

4. The mainly competitive/mixed mode of action of these compounds agreed with the one we previously found for

2 and MAO B [

35]. This mechanism of inhibition was verified also for the compound

7, as K

M was found to be more affected than V

max parameter by the presence of the compound (

Figure S1).

2.2.3. Selectivity of compounds 3 and 5-7 versus other amine oxidases

In order to evaluate the potential effect of the polyamine analogues as MAO inhibitors in a cellular system, it is important to have information on their selectivity towards other types of amine oxidases (AOs). In our studies compound

2 was found to be poor inhibitor of the human Semicarbazide-Sensitive Amine Oxidase/Vascular Adhesion Protein-1 (VAP-1) and of murine spermine oxidase (SMOX) and compound

1 was found effective more than

2 for SMOX [

41]. Because of this, the specificity of compounds

3 and

5-7 was evaluated towards these two other types of amine oxidases. It was not possible to test compound

4, due to the interferences above reported with the amine oxidase assay method used for the detection of the generation ratio of hydrogen peroxide. These AOs were chosen also because both of them are pharmacological targets: VAP-1 is involved in various inflammatory diseases and some type of cancer [

42,

43] and SMOX is involved in both the catabolism of polyamines (spermine and spermidine) and in the progression of some types of cancer [

44,

45]. Thus, after verifying that these analogues are not substrates of these AOs (up to 50 μM concentration), the compounds were tested at a fixed concentration as potential inhibitors of VAP-1 and SMOX. Their effect on the catalytic efficiency (V

max/K

M) is shown in

Table 2, where the V

max/K

M relative to each control sample (V

max/K

M )

+i/( V

max/K

M)

0 , that is as residual catalytic efficiency in the presence of the specific concentration of the compound is reported. This kinetic parameter gives information about the physical interaction of the compound with the enzyme, under not saturating condition of substrate.

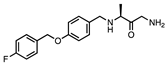

2.3. Docking studies

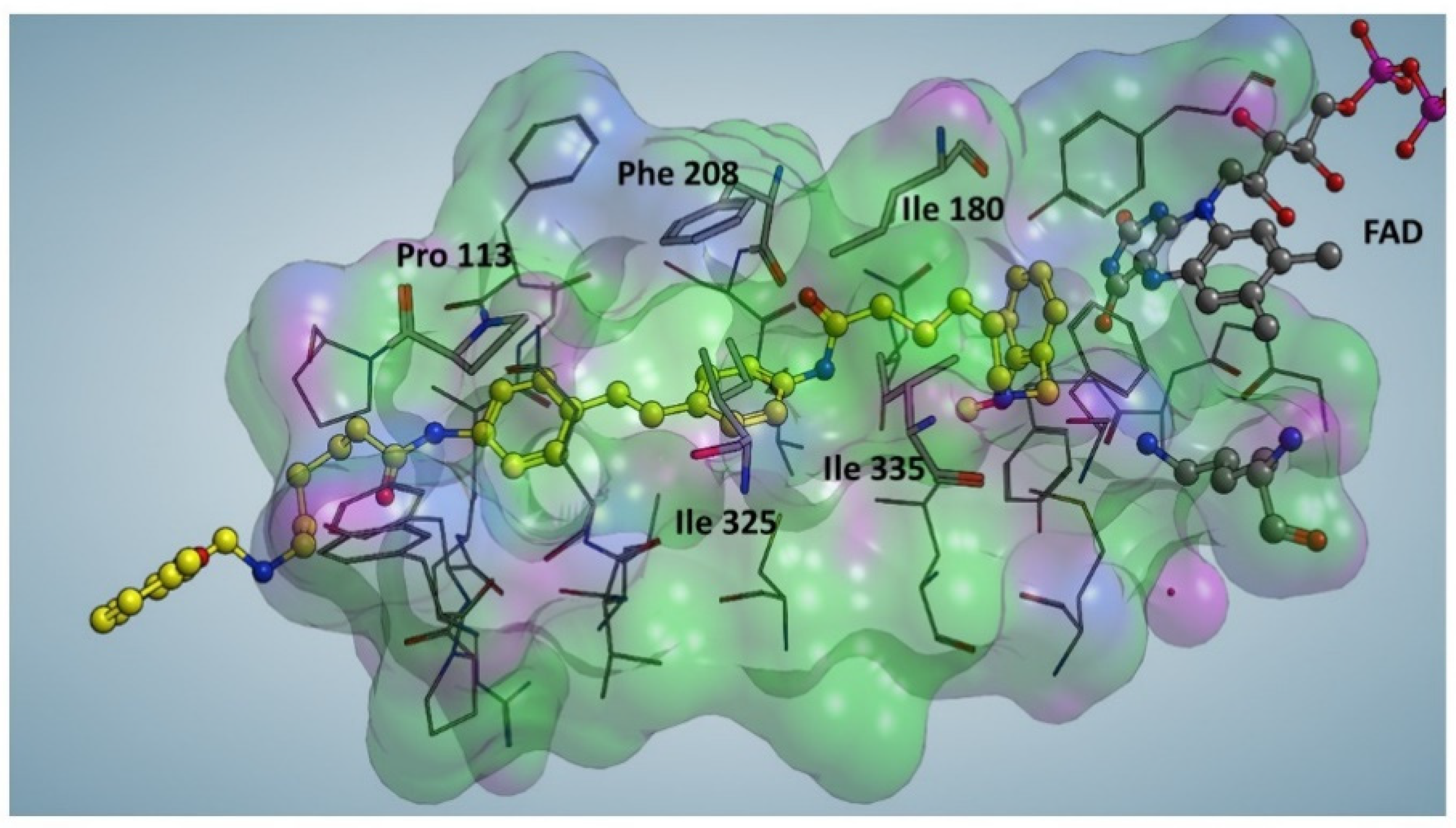

Compound 5, the most potent MAO A and MAO B inhibitor, was docked against MAO A crystal structure (PDB code: 2Z5Y) to determine its binding mode. Before the docking procedure, a Site Finder approach was applied to select all the possible binding sites of MAO A. Interestingly, the most suitable interaction region was superimposed with the catalytic binding site of MAO A, accordingly to the competitive mechanism of action of this molecule found by the enzyme activity assays. The catalytic sites of MAO A (as well as MAO B) is characterized by a hydrophobic tunnel and a small hydrophilic region located close to FAD. In particular, compound 5 can efficiently interact with the catalytic sites of MAO A through a series of hydrophobic interactions with specific protein residues, namely Ile 180, Ile 325 and Ile 335. It worth mentioning the formation of a π-π stacking with Phe 208 and a CH/π interaction with Pro 113 (Figure. 4). These two interactions involve two aromatic rings in the center of 5 moiety substantially stabilizing the interaction with MAO active site and accounting for the difference in the inhibitory potency of compound 5 in comparison to compound 2 (Ki<1μM for 5 vs Ki>200 μM for 2). As a result, replacing the inner dipiperidine moiety of compound 2 with the dianilide structure in 5 is crucial for enhancing the inhibitory potential of this class of polyamine analogues.

These data confirm that the introduction of a dianiline moiety (compound 4) in place of a dipiperidine of compound 2 determines an improvement in the MAO inhibitory potency. Furthermore, the increase in structural stiffness due to the presence of amide groups further contributes to the stabilization of compound 5 within the MAO A catalytic pocket. Interestingly, amide groups of compound 3, even in the absence of aromatic rings, increase significantly the potency respect to compound 2, while in compound 4 and 5, both bearing inner aromatic groups, the modification of the dianiline moiety of compound 4 in a dianilide of compound 5 increases only slightly the potency indicating, in this couple of compounds, the major contribution of the feature of the central core instead of the importance of the basicity of the inner nitrogen atoms.

Figure 4.

Docking Simulation of compound 5 inside the catalytic site of MAO A. The catalytic pocket of MAO A is configured as a predominantly hydrophobic tunnel (green regions) while the polar portions (purple) mainly face the solvent. The molecule (yellow) is almost totally immersed inside the catalytic pocket of MAOA.

Figure 4.

Docking Simulation of compound 5 inside the catalytic site of MAO A. The catalytic pocket of MAO A is configured as a predominantly hydrophobic tunnel (green regions) while the polar portions (purple) mainly face the solvent. The molecule (yellow) is almost totally immersed inside the catalytic pocket of MAOA.

2.4. Biological evaluation

2.4.1. Antiproliferative activity

Previous results demonstrating the cytotoxicity of compound

1-analogues and some naphthalene diimide -polyamine hybrids [

46] including

7, prompt us to investigate the antiproliferative effect of compounds

1-

7 on three different human tumor cell lines: Hep G2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma), LN-229 (glioblastoma). The non-tumorigenic mesothelium cells MeT-5A were considered as healthy cell model. Compound

1 and the well-known antitumor drug doxorubicin were taken as reference compounds. The GI

50 values, representing the concentration of compound inducing a reduction of 50% in cell number with respect to the control culture, are shown in

Table 3. The data support the lack of cytotoxicity of compound

1 against human cancer cells, Hep G2, MCF-7 and LN-229 (GI

50>20 μM), and on non-tumorigenic cells, MeT-5A. Interestingly, the replacement of the inner octamethylene chain of compound

1 with the less flexible dipiperidineoiety led to a significant increase in the antiproliferative active, regardless the nature of the inner nitrogen atoms (

2 vs

3). In particular,

3 appears the most effective, with GI

50 values on human cancer cells ranging from 2.2 to 16.8 μM, while

2 shows a detectable effect solely in MCF-7 and LN-229, GI

50 5.7 and 4.6 μM, respectively.

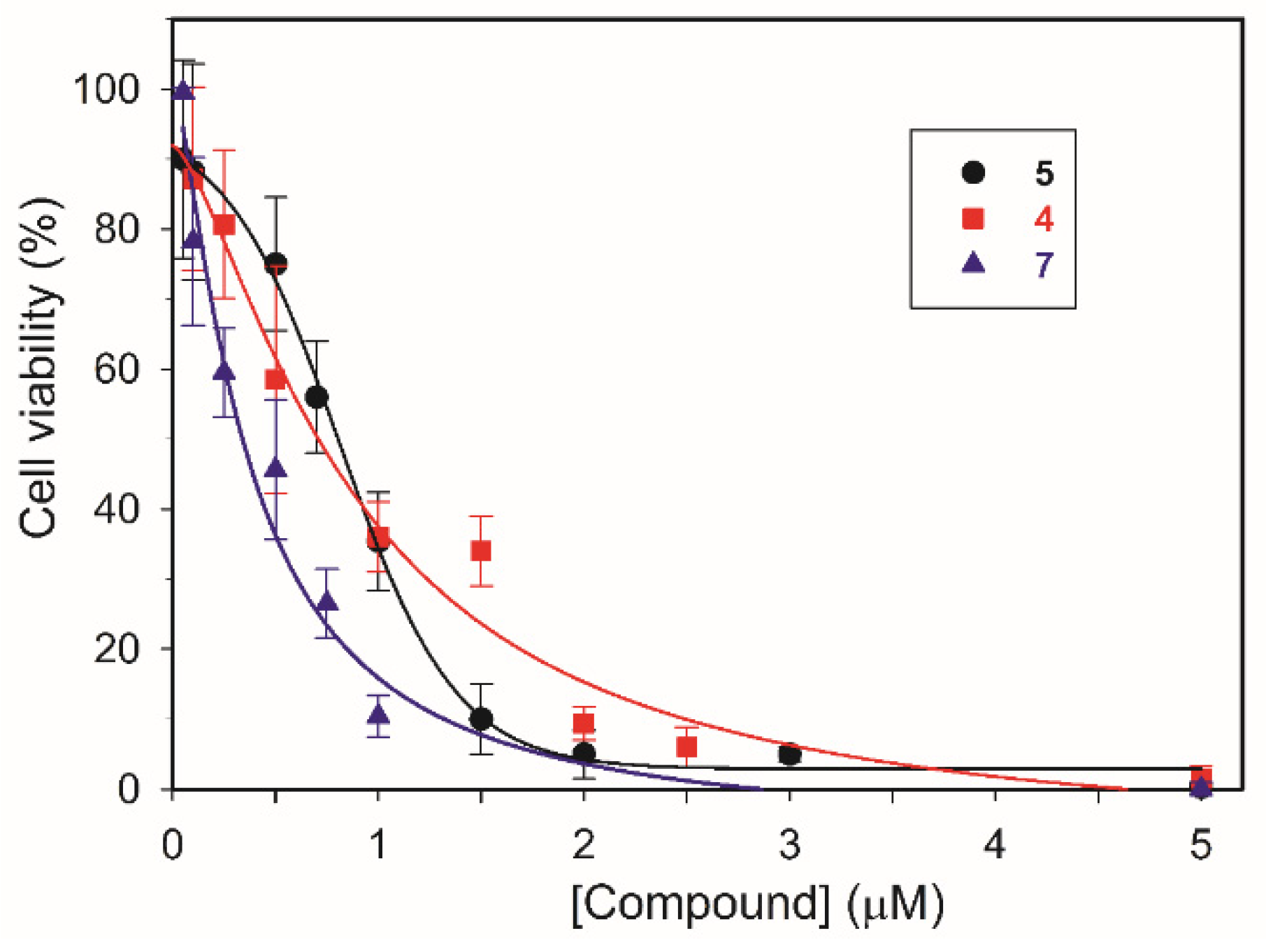

Moreover, the replacement in compounds

2 and

3 of the dipiperidine with the dianilino moiety, to obtain

4 and

5 respectively, allows a further increase in cytotoxic ability. In fact, for both derivatives low micromolar GI

50 values are obtained in all tested cancer cells. The enlargement of the central moiety with a tetracyclic ring (

6 and

7) preserves the antiproliferative effectiveness. In particular

7, characterized by a naphthalene diimide core is the most cytotoxic of the series, showing submicromolar GI

50 values in all cell lines, in agreement with previous data obtained on other tumor cells [

46].

In addition, the presence of an amide moiety in the central core appears also important, especially for

2,

3 and

6, 7 pairs. Indeed, in both cases the amide functional groups cause a significant increase in cytotoxic ability. Otherwise, the amide does not play a relevant role in cell effect induced by

5 and

4 which show similar GI

50 values. Overall, among the tested compounds,

5, 4 and

7 were found to be the most effective as antiproliferative agents (

Table 3), and interestingly, LN-229 glioblastoma cells appear the most sensitive. The cell viability percentage of LN-229 as a function of the concentration of

4,

5 and

7, is showed in

Figure 5. Finally, it is noteworthy that the GI

50 values obtained by treating the non-tumorigenic MeT5-A with tested polyamine derivatives are significantly higher for compounds

3-

5 and

7 with respect to those obtained for cancer cells, suggesting, in particular for

3 and

5, a lower toxicity towards healthy cells.

2.4.2. Compounds 4 and 5 on MAO activity in LN-229 lysates

The above results appeared of particular interest because recent studies found that MAO A is overexpressed in human glioma tissue [

47] and clorgyline, a well-known MAO A inhibitor, was found to be effective

in vivo combined with a chemotherapeutic agent [

17]. Interestingly, Marconi et al. (2019) [

48] found that some MAO B inhibitors increase the oxidative stress level, resulting in cell cycle arrest, and a markedly reduction in glioma cells migration, thus reinforcing the hypothesis of a critical role played by MAO B in mediating oncogenesis in high-grade gliomas. Based on these studies and on the interesting biological profile showed by compounds

4 and

5 on human recombinant MAOs (

Table 1) and on LN-229 glioblastoma cells (

Table 3), we investigated the inhibitory effect of the polyamine derivatives on the enzyme activity in glioblastoma cells. For this purpose, we performed a preliminary analysis to verify the presence of MAO activity in LN-229 lysates, using various concentration of kynuramine as substrate. Results reported in

Figure 6 clearly showed the presence of oxidative deamination of kynuramine, on increasing the substrate concentration, with a saturating effect at high concentration of substrate. By fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation to the experimental data the following kinetic parameters were obtained: K

M = 25 ± 3 μM and apparent V

max= 4.96 ± 2.57 If/min (in a.u.), corresponding to 20.5 pmol

(4-HQ) min

-1 mg

protein-1 .

To evaluate the contribute of the two MAO isoforms to the total MAO activity in lysates, specific inhibitors of MAO A and MAO B were used. In details, lysates were pre-incubated for 15 min with clorgyline (an irreversible and specific inhibitor of MAO A), deprenyl, (an irreversible and specific inhibitor of MAO B) and pargyline ( irreversible inhibitor of both MAO isoforms) [

49], before determining the residual MAO activity by adding kynuramine (300μM), as substrate. The results, shown in

Table 4, clearly demonstrate that after pargyline pre-incubation, only about 3% of residual activity was detected, confirming that the enzymatic activity on kynuramine depend only to MAOs. The percentage of inhibition after clorgyline treatment suggested that 75% of MAO activity is due to the MAO A isoform and that the residual 25% is due to the MAO B isoform, inhibited by deprenyl.

These data were confirmed also by treatment with safinamide, a specific and reversible MAO B inhibitor (Ki= 20 nM on human recombinant MAO B) and harmine, a reversible MAO A inhibitor (Ki=2nM on human recombinant MAO A). Overall, these results indicate that in LN-229 cell lines MAOs enzyme activity is detectable, and that MAO A is the mainly expressed isoform.

Thus, in LN-229 cell lysates the inhibitory behavior of compounds

4 and

5 was also evaluated, using kynuramine as substrate (20 μM concentration, that is at concentration slightly lower than the apparent K

M determined in lysates), and the test compounds in the range 0.05-8 μM. In these experimental conditions, derivative

5 showed the ability to induce a concentration dependent inhibition with a calculated apparent Ki=2μM (

Figure 6B). On the other side, compound

4 showed no reduction in residual activity as the compound’s concentration was increased (

Figure 6B). These results suggested that compound

5, the most effective inhibitors for both the human MAO isoforms (

Table 1), is effective also in lysate, while compound

4, is much less effective. Because of the similar cytotoxic effect of

5 (

Table 2), it is reasonable to hypothesized that

4 may interact with some cellular targets/biomolecules other than MAOs.

3. Discussion

Monoamine oxidases, well-known targets in neurodegenerative and neurological disorders, are recently emerging as potential targets in cancer. Indeed, MAOs, mainly the MAO A isoform, was found to be increased/overexpressed in certain types of tumor, such as prostate cancer and glioblastoma [

7,

8,

12,

19]. Therefore, MAO inhibition in relation to cancer regression is the object of investigation for potential development of novel anticancer therapies [

7,

16,

21,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Starting from our previous studies on the polyamine analog 2 as reversible MAO B inhibitors, five structurally related derivatives (compounds 3-7), were selected. These compounds, which are characterized by a reduced flexibility of the inner moiety respect the lead compound, were evaluated as MAO inhibitors, with the aim to investigate how these modifications affect their inhibitory ability and to outline structure-activity relationships. The replacement of the inner dipiperidine moiety of compound 2, with a less flexible dianiline moiety (compound 4) and the further modification of the amine functions in two amide groups (compound 5), strongly improved their inhibitory potency, decreasing the Ki values in the submicromolar range (Ki < 1μM), that is of more than two orders of magnitude respect to compound 2 (Ki >250μM). With regards the mechanism of inhibition, compounds 4 and 5 act as reversible and mainly competitive inhibitors, as they bind into the enzyme active site. The presence of a large and more rigid inner core (the naphthalene diimide-related ring in compounds 6 and 7) reduced the accessibility of the compound into MAO active site and decreased the inhibitory potency. Docking studies highlighted the structural determinants of the inhibitory potency of compound 5 for MAO A: the hydrophobic part of its active site tunnel very efficiently interacts with 5, and its inner aromatic rings play a key role in the formation of π−π stacking with Phe 208.

It is worthnoting that even if to the improved inhibitory potency of compounds 4 and 5 did not correspond an improved selectivity between the two MAO isoforms (Selectivity index KiMAO A: KiMAO B, 3:1), compound 5 was found to be very specific for MAO in comparison to two other types of AOs and pharmacological targets, SMOX and VAP-1/SSAO.

Compounds 4 and 5, the most effective MAO inhibitors, were found endowed also of antiproliferative effects on three human tumor cell lines, in particular on the glioblastoma cells LN-229 (GI50< 1μM). Additionally, 5 was found about 10 times less active on a non-tumorigenic cell line. Taking into account the presence of MAO activity in LN-229 cell lysates (about 70% due to the MAO A isoform and 30% MAO B), the effectiveness of compounds 4 and 5 as MAO inhibitors was evaluated in lysates of this cell line. Surprisingly, compound 5 only was found very effective in inhibiting MAO activity also in lysates, differently from its structurally related compound 4. This different behavior suggests that other cellular targets can be responsible for the biological activity of compound 4.

In conclusion, the main results of this study were the identification of compounds 4 and 5 as potent and reversible MAO inhibitors, both of them endowed of good antiproliferative activity, mainly on the tumorigenic LN-229 cell line, a glioblastoma model. Further studies are in progress to clarify the intracellular mechanism of action determining cell death in LN-229 and the role play by MAO activity in this process. As an overexpression of MAO was found in glioblastoma, the polyamine scaffold of compounds 4 and 5 is worthy of consideration for future development of multi-targeting anticancer agents.

4. Materials and Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Merk S.r.l. (Milan, Italy), with the exception of Amplex Red reagent (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine), purchased from Invitrogen (Invitrogen s.r.l, San Giuliano Milanese (MI, Italy). All reagents were of analytical grade. Human recombinant MAO A and MAO B expressed in baculovirus infected BT1 cells (5 mg/mL) and horseradish peroxidases were purchased from Merk s.r.l. (Italy). VAP-1 was a kindly gift from Biothie Therapies Cor. (Turku, Finland). The recombinant SMOX protein was expressed in

E. coli BL21 DE3 cells and purified according to Cervelli et al. [

50]. The stock solution of compound

1-

2 were prepared in water, the other compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (10 mM stock concentration).

4.1. Chemistry

Compound

6 has been synthesized following the procedure reported in

Scheme 1. Briefly, a solution of 2 M Borane N-ethyl-N-isopropylaniline complex in THF (4 ml) was added to compound

7 (1.41 g, 2 mmol) in dry diglyme (20 ml) under stream of nitrogen and the resulting mixture was refluxed for 5 h. After cooling down, water (4 ml) and 6N HCl

aq (4 ml) were carefully added dropwise, and the mixture was then refluxed for 1 h. The organic solvent was removed in vacuo and the aqueous layer were extracted with dichloromethane (3 x 20 ml) which was dried and evaporated to give a residue that was purified via flash chromatography using as mobile phase a mixture of dichloromethane/methanol/aqueous ammonia 33% (9:1:0.05) to give 6 (0.416 g, 32 % yield) as yellow oil.

1H NMR (free base, 400 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 1.13-1.27 (m, 12H), 2.69-2.83 (m, 8H), 3.88 (s, 4H), 3.97 (s, 6H), 4.12-4.32 (m, 12H), 6.84-6.99 (m, 4H), 7.30-7.37 (m, 4H), 8.78 (s, 4H); MS (ESI+) m/z = 650 (M+H)

+. Compounds

1-

5 and

7 were synthetized as previously reported [

33,

37].

4.2. Amine oxidase assay methods

The AO activity was performed using two different assay methods. When possible, for the AO activity of VAP-1 and SMOX the fluorometric assay that detect the H

2O

2 generation rate by a peroxidase-coupled continuous assay, was applied [

51]. This fluorometric method used the Amplex Red reagent as substrate for horseradish peroxidase [

54]. Each assay was performed at 37°C, in a solution (volume of 800 μl) containing 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.1 mM EDTA, in the presence of Amplex Red (100 μM) and horseradish peroxidase type II (5 UmL

-1). The initial velocities were determined by measuring the increase in fluorescence intensity (λ

exc = 563 nm and λ

em = 586 nm) and the H

2O

2 generation rate was calculated from the change in fluorescence intensity, by means of calibration curves obtained by serial dilution of stock solution of H

2O

2. Except for compound

4, no significant interference of the other polyamine analogues on the preliminary calibration curves was observed. Benzylamine and spermine were used as substrates for VAP-1 and SMOX, respectively. The evaluation of the effect of all the compounds (

1-7) on the MAO activity, was performed by the kynuramine assay [

55], due to the interferences of compound

4 with the Amplex-red method. MAO stock solutions were diluted with assay buffer (final concentration 0.006 mg/mL for MAO-A, 0.004 mg/mL for MAO-B, or 0.3 mg/mL for LN-229 lysates, in 0.2 mL) in the presence or absence of the various inhibitors. Then, the substrate (kyn) was added at a specific final concentration (10 μM, for the first-order conditions, [kynuramine]<K

M, or at various substrate in the experiments performed to determinate K

M and V

max). After 45 min incubation at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by addition of 2M NaOH (80 μL) and 480 μL of distilled water. Kynuramine deaminated by MAOs spontaneously cyclizes to give 4-hydroxyquinoline, the amount of which was determined by the fluorescence intensity of the peak of its emission spectra (λ

exc= 330 nm and λ

em330-530 nm), using a specific calibration curve built with the standard 4-hydroxyquinoline. To determine the MAO isoform in cell lysates, samples were pre-incubated for 15 min at 37°C in the absence or in the presence of the irreversible and specific inhibitors clorgyline to inhibit MAO A (5 nM), deprenyl to inhibit MAO B (5 nM) and pargyline to inhibit both MAO isoforms (0.5mM) before adding the substrate 300 μM (saturating conditions). For the assay with reversible and specific inhibitors, MAO activity was performed in the presence of safinamide (0.2 μM, to inhibit MAO B) or harmine (0.2 μM to inhibit MAO A) and kynuramine 20 μM as non-saturating substrate.

Control sample, in the absence of inhibitor, and blank sample, in the absence of enzyme, were also run under the same experimental conditions. All kinetic experiments were performed at least in triplicate.

A Cary-Eclipse fluorimeter and a Cary Scan UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) were used for fluorometric and spectrophotometric measurements, respectively.

4.2.1. Kinetic analysis

Steady state kinetic parameters (Vmax and KM) were calculated by fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation to the experimental data (initial rate of reactions vs substrate concentrations), with Sigma Plot software, version 9.0 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA, USA). The apparent Vmax and KM values of human recombinant MAO A and MAO B were determined in the presence of different concentrations of the various compounds. The mode of inhibition was determined by global fit analysis (GraphPad 9.0 software, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) of the initial rate of reaction (V0) vs substrate concentration plots, in the presence and absence of inhibitor, to fit equations for competitive, mixed, non-competitive and uncompetitive inhibition models; the fit giving the highest r2 value was selected for the calculation of inhibition constants (Ki).

The reversibility of the inhibition by compound

4 and

5 (the most potent MAO inhibitors,

Table 1) was evaluated by incubating the enzyme (recombinant MAO A or MAO B,) with

4 or

5 at 5 μM concentration (more the fivefold respect to their Ki values). After 25 min, at 37°C, in potassium phosphate buffer (0.1M K/Pi, pH 7.4, 0.1mM EDTA), the enzyme-inhibitor (or the control sample without inhibitor) solution was fiftyfold diluted and substrate ([Kyn]=300 μM) was added to measure residual enzyme activity.

Ki values are expressed as mean ±S.D.

Linear regression analysis was performed by using the Sigma Plot version 9.0 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA, USA) and, unless stated otherwise, the correlation coefficient for linear regression was 0.98 or greater.

4.3. Cell culture

Human tumor cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). LN-229 (human glioblastoma) and MCF-7 (human breast cancer) cells were cultured in DMEM (D2902, Sigma Chemical Co.) supplemented with 3.5 g/L glucose and 5% or 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (F7524, Sigma Chemical Co.), respectively. HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cell line were grown in MEM (M0894, Sigma Chemical Co.) supplemented with 10% FCS. 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B (Sigma Chemical Co.) were added to all media. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere incubator containing 5% carbon dioxide in air.

4.4. Cell lysate

LN-229 (about 9x10

5) were seeded in standard conditions. After 24 hours (80% confluence), cells were collected, trypsinized and washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS)-EDTA (8 mM Na

2HPO

4, 1.5 mM KH

2PO

4, 2 mM KCl, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) at 4°C and frozen in liquid nitrogen until use. About 10 million cells were lysed in 1 mL of lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail, 1:400 v/v) and frozen in liquid nitrogen until use. The protein content was measured by the Bradford method, with bovine serum albumin as standard [

56].

4.5. Inhibition growth assay

Cells (3-6 × 104/well) were seeded into a 24-well cell culture plate and after 24h different concentrations of the test compounds or reference drug were added. After 48h of incubation in standard conditions, cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion assay. Antiproliferative data were expressed as GI50 values, that is, the concentration of the test agent that induces a 50% reduction in cell number compared to a control untreated culture. At least three independent experiments, in duplicate, were performed.

4.6. In silico analysis

The crystal structure of human MAO A was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB code: 2Z5X) and processed in order to remove ligands and unnecessary water molecules. Hydrogen atoms were added using standard geometries with the MOE program [

57]. To minimize contacts between hydrogens, the structures were subjected to FF19SB force field minimization until the root mean square deviation of conjugate gradient was <0.1 kcal•mol−1•Å−1 (1 Å = 0.1 nm) keeping the heavy atoms fixed at their crystallographic positions. Selected compounds were built minimized and charged using the MMFF94x force field of MOE. Before the molecular docking procedure a Site Finder Approach [

57] was performed. Using the Site Finder indications, docking experiments were performed using the MOE Dock program; Triangle Matcher was exploited as the placement method while GBVI/WSA dG as the scoring tool. The docking complexes were subjected to subjected to Molecular Dynamics simulation (MD) using ACEMD [

58] (FF19SB force field) with explicit water molecules (TIP3P model). Firstly, a solvent equilibration (1 ns) was obtained applying positional restraints on carbon atoms. Secondly, 10 ns molecular dynamics was performed on the full system. The equilibration phase was performed by using NPT ensemble (isothermal, isobaric), at constant pressure (1 atm, Berendsen method) and temperature (300 K, Langevin thermostat).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Double reciprocal plots of MAO B activity in presence of various concentration of compound 7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.D.P., A.M., A.MI. and L.D.V..; drug design, A.MI., and A.M.; chemical synthesis F.B., E.T. and A.MI.; docking studies, G.C..; kinetic studies M.L.D.P; M.R. and G.N., biological studies G.N. and F.P.; SMOX preparation, M.C.; data analysis and interpretation, M.L.D.P., L.D.V., A.M., A.MI.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.D.P., L.D.V. A.M. and A.MI..; writing—review and editing, M.L.D.P., L.D.V., A.M., G.C. and A.MI.; supervision, M.L.D.P., L.D.V. and A.M.; funding acquisition, M.L.D.P., L.D.V and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by institutional grants from the University of Padova, Italy Progetto FINA 2012; DI_P_FINA21_01 to M.L.D.P and BIRD 2021; BIRD213012 to L.D.V., from Supporting Talent in ReSearch@University of Padua to GC (COZZ_STARS20_01) and from the University of Bologna, Italy, Grant RFO to A.M and to A.MI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available contacting the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the “International Polyamine Foundation –ONLUS” for the availability to look up in the Polyamine documentation; The authors would like to thanks Dr. D.J. Smith and Biothie Therapies Cor. (Turku, Finland) for the kind gift of the purified human r-SSAO/VAP-1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tipton, K.F. 90 years of monoamine oxidase: Some progress and some confusion. J. Neural. Transm. 2018, 125, 1519–1551. [CrossRef]

- Youdim, M.B.; Edmondson, D.; Tipton, K.F. The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 295-309. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.C.; Upadhyay, S.; Paliwal, S.; Saraf, S.K. Privileged scaffolds as MAO inhibitors: Retrospect and prospects. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 145, 445-497. [CrossRef]

- Carradori, S.; Fantacuzzi, M.; Ammazzalorso, A.; Angeli, A.; De Filippis, B.; Galati, S.; Petzer, A., Petzer, J. P.; Poli, G.; Tuccinardi, T.; Agamennone, M.; & Supuran, C. T. Resveratrol Analogues as Dual Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase B and Carbonic Anhydrase VII: A New Multi-Target Combination for Neurodegenerative Diseases?. Molecules 2022, 27, 7816. [CrossRef]

- Santin, Y.; Resta, J.; Parini, A.; Mialet-Perez, J. Monoamine oxidases in age-associated diseases: New perspectives for old enzymes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 66, 101256. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wu, B.J. Monoamine oxidase A: An emerging therapeutic target in prostate cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1137050. [CrossRef]

- Meenu, M.; Verma, V.K.; Seth, A.; Sahoo, R.K.; Gupta, P.; Arya, D.S. Association of Monoamine Oxidase A with Tumor Burden and Castration Resistance in Prostate Cancer. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2020, 93, 100610. [CrossRef]

- Shih, J.C. Monoamine oxidase isoenzymes: Genes, functions and targets for behavior and cancer therapy. J. Neural. Transm. 2018, 125, 1553-1566. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. C.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Ma, F.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, S.; Ma, X.; Li, Y. R.; Neal, A.; Huang, J.; To, A.; Clarke, N.; Memarzadeh, S.; Pellegrini, M.; & Yang, L. Targeting monoamine oxidase A-regulated tumor-associated macrophage polarization for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3530. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hu, L.; Ma, Y.; Huang, B.; Xiu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, K.; & Tang, X. Increased expression of monoamine oxidase A is associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition and clinicopathological features in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3245–3251. [CrossRef]

- Flamand, V.; Zhao, H.; & Peehl, D. M. Targeting monoamine oxidase A in advanced prostate cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 136, 1761-1771. [CrossRef]

- Gabilondo, A. M.; Hostalot, C.; Garibi, J. M.; Meana, J. J.; & Callado, L. F. Monoamine oxidase B activity is increased in human gliomas. Neurochem. Int. 2008, 52, 230–234. [CrossRef]

- Dhabal, S.; Das, P.; Biswas, P.; Kumari, P.; Yakubenko, V. P.; Kundu, S.; Cathcart, M. K.; Kundu, M.; Biswas, K.; & Bhattacharjee, A. Regulation of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) expression, activity, and function in IL-13-stimulated monocytes and A549 lung carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 14040-14064. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. B.; Shao, C.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Hu, P.; Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. T.; Yin, F.; Liao, C. P.; Stiles, B. L.; Zhau, H. E.; Shih, J. C.; & Chung, L. W. Monoamine oxidase A mediates prostate tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 2891-2908. [CrossRef]

- Peehl, D.M.; Coram, M.; Khine, H.; Reese, S.; Nolley, R.; Zhao, H. The significance of monoamine oxidase-A expression in high grade prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 2206-2211. [CrossRef]

- Gross, M. E.; Agus, D. B.; Dorff, T. B.; Pinski, J. K.; Quinn, D. I.; Castellanos, O.; Gilmore, P.; & Shih, J. C. Phase 2 trial of monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine in biochemical recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021 24, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Kushal, S.; Wang, W.; Vaikari, V.P.; Kota, R.; Chen, K.; Yeh, T. S.; Jhaveri, N.; Groshen, S. L.; Olenyuk, B. Z.; Chen, T. C.; Hofman, F. M.; & Shih, J. C. Monoamine oxidase A (MAO A) inhibitors decrease glioma progression. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 13842-13853. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; He, Q.; Zhang, P.; & Tang, X. The role of monoamine oxidase A in HPV-16 E7-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and HIF-1α protein accumulation in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2692-2703. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, M.A.; Baskin, D.S. Monoamine oxidase B levels are highly expressed in human gliomas and are correlated with the expression of HiF-1α and with transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3379-3393. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. C.; Chien, M. H.; Lai, T. C.; Su, C. Y.; Jan, Y. H.; Hsiao, M.; & Chen, C. L. Monoamine Oxidase B Expression Correlates with a Poor Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer Patients and Is Significantly Associated with Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition-Related Gene Signatures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2813. [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, R.; Alsous, L.; Sabbah, D.A.; Gul, H.I.; Gul, M.; Bardaweel, S.K. Monoamine Oxidase (MAO) as a Potential Target for Anticancer Drug Design and Development. Molecules 2021, 26, 6019. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Kim, Y. J.; Wang, Y. C.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Zeng, S.; Ma, X.; Choi, I. Y.; Di Biase, S.; Smith, D. J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y. R.; Ma, F.; Huang, J.; Clarke, N.; To, A.; Gong, L.; Pham, A. T.; Moon, H.; … Yang, L. Targeting monoamine oxidase A for T cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabh2383. [CrossRef]

- Mehndiratta, S.; Qian, B.; Chuang, J.Y.; Liou, J.P.; Shih, J.C. N-Methylpropargylamine-Conjugated Hydroxamic Acids as Dual Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase A and Histone Deacetylase for Glioma Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 2208-2224. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. T.; Choi, M. R.; Doh, M. S.; Jung, K. H.; & Chai, Y. G. Effects of the monoamine oxidase inhibitors pargyline and tranylcypromine on cellular proliferation in human prostate cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 30, 1587-1592. [CrossRef]

- Minarini, A.; Milelli, A.; Tumiatti, V.; Rosini, M.; Bolognesi, M. L.; & Melchiorre, C. Synthetic polyamines: An overview of their multiple biological activities. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 383-392. [CrossRef]

- Karigiannis, G., Papaioannou, D. Structure, biological activity and synthesis of polyamine analogues and conjugates. Eur. J. of Org. Chem., 2000,(10),1841-1863. [CrossRef]

- Casero, R., Marton, L. Targeting polyamine metabolism and function in cancer and other hyperproliferative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6, 373–390 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Casero, R. A. Jr.; & Woster, P. M. Recent advances in the development of polyamine analogues as antitumor agents. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4551-4573. [CrossRef]

- Casero, R. A., Jr.; Murray Stewart, T.; & Pegg, A. E. Polyamine metabolism and cancer: Treatments, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 681-695. [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolskaite ,A.; Gardner, R.A.; Delcros, J.G., Phanstiel. O 4th. Development of Polyamine Lassos as Polyamine Transport Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 319-326. PMID: 35178189; PMCID: PMC8842098. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kaiser, M.; Copp, B.R. Investigation of Indolglyoxamide and Indolacetamide Analogues of Polyamines as Antimalarial and Antitrypanosomal Agents. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 3138-3160. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Sharma, S. Hazeldine, M. L. Crowley, A. Hanson, R. Beattie, S. Varghese, T. M. D. Senanayake, A. Hirata, F. Hirata, Y. Huang, Y. Wu, N. Steinbergs, T. Murray-Stewart, I. Bytheway, R. A. Casero and P. M. Woster, Polyamine-based small molecule epigenetic modulators Med. Chem. Commun., 2012, 3, 14. [CrossRef]

- Houdou, M.; Jacobs, N.; Coene, J.; Azfar, M.; Vanhoutte, R.; Van den Haute, C.; Eggermont, J.; Daniëls, V.; Verhelst, S.H.L.; Vangheluwe, P. Novel Green Fluorescent Polyamines to Analyze ATP13A2 and ATP13A3 Activity in the Mammalian Polyamine Transport System. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 337. [CrossRef]

- Tumiatti, V.; Minarini, A.; Milelli, A.; Rosini, M.; Buccioni, M.; Marucci, G.; Ghelardini, C.; Bellucci, C.; & Melchiorre, C. Structure-activity relationships of methoctramine-related polyamines as muscarinic antagonist: Effect of replacing the inner polymethylene chain with cyclic moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 2312-2321. [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, E.; Minarini, A.; Tumiatti, V.; Milelli, A.; Lunelli, M.; Pegoraro, M.; Rizzoli, V.; & Di Paolo, M. L. Synthetic polyamines as potential amine oxidase inhibitors: A preliminary study. Amino Acids 2012, 42, 913-928. [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, E.; Milelli, A.; Cozza, G.; Tumiatti, V.; Marchetti, C.; Agostinelli, E.; Fimognari, C.; Hrelia, P.; Minarini, A.; & Di Paolo, M. L. Novel polyamine analogues: From substrates towards potential inhibitors of monoamine oxidases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 70, 88-101. [CrossRef]

- Tumiatti, V.; Andrisano, V.; Banzi, R.; Bartolini, M.; Minarini, A.; Rosini, M.; & Melchiorre, C. Structure-activity relationships of acetylcholinesterase noncovalent inhibitors based on a polyamine backbone. 3. Effect of replacing the inner polymethylene chain with cyclic moieties. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6490-6498. [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Wang, J.; Pisani, L.; Caccia, C.; Carotti, A.; Salvati, P.; Edmondson, D. E.; & Mattevi, A. Structures of human monoamine oxidase B complexes with selective noncovalent inhibitors: Safinamide and coumarin analogs. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 5848-5852. [CrossRef]

- Hubálek, F.; Binda, C.; Khalil, A.; Li, M.; Mattevi, A.; Castagnoli, N.; & Edmondson, D. E. Demonstration of isoleucine 199 as a structural determinant for the selective inhibition of human monoamine oxidase B by specific reversible inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 15761-15766. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sablin, S. O.; & Ramsay, R. R. Inhibition of monoamine oxidase A by beta-carboline derivatives. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997, 337, 137-142. [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, M.L. Cervelli, M.; Mariottini, P.; Leonetti, A.; Polticelli, F.; Rosini, M.; Milelli, A.; Basagni, F.; Venerando, R.; Agostinelli, E.; Minarini, A. Exploring the activity of polyamine analogues on polyamine and spermine oxidase: Methoctramine, a potent and selective inhibitor of polyamine oxidase. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2019, 34, 740-752. PMID: 30829081; PMCID: PMC6407594. [CrossRef]

- Pannecoeck, R.; Serruys, D.; Benmeridja, L.; Delanghe, J. R.; van Geel, N.; Speeckaert, R.; & Speeckaert, M. M. Vascular adhesion protein-1: Role in human pathology and application as a biomarker. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2015, 52, 284-300. [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.; & Jalkanen, S. Vascular Adhesion Protein-1: A Cell Surface Amine Oxidase in Translation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 314-332. [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Sun, D.; Zhang, J.; Xue, R.; Janssen, H. L. A.; Tang, W.; & Dong, L. Spermine oxidase is upregulated and promotes tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2018, 48, 967-977. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Roh, S.; Hong, I.; Kim, H.; Ahn, T.S.; Kang, D.H.; Lee, M.S.; Baek, M.-J.; Kwak, H.J.; et al. Expression of Spermine Oxidase Is Associated with Colorectal Carcinogenesis and Prognosis of Patients. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 626. [CrossRef]

- Tumiatti, V.; Milelli, A.; Minarini, A.; Micco, M.; Gasperi Campani, A.; Roncuzzi, L.; Baiocchi, D.; Marinello, J.; Capranico, G.; Zini, M.; Stefanelli, C.; & Melchiorre, C. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of substituted naphthalene imides and diimides as anticancer agent. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7873-7877. [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, R.L.; Wu, W.Y., Dahlin, A.M.; Tsavachidis, S,; Gliogene Group; Bondy. M.L.; Melin. B. Role of monoamine-oxidase-A-gene variation in the development of glioblastoma in males: A case control study. J Neurooncol. 2019, 45, 287-294. [CrossRef]

- Marconi, G. D.; Gallorini, M.; Carradori, S.; Guglielmi, P.; Cataldi, A.; & Zara, S. The Up-Regulation of Oxidative Stress as a Potential Mechanism of Novel MAO-B Inhibitors for Glioblastoma Treatment. Molecules 2019, 24, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.J.; Mantle, T- J.; Tipton, K. F. The nature of the inhibition of rat liver monoamine oxidase types A and B by the acetylenic inhibitors clorgyline, l-deprenyl and pargyline. Biochem.Pharmacol. 1982, 31, 3555-3561. [CrossRef]

- Zarmouh, N.O.; Messeha, S.S.; Mateeva, N.; Gangapuram, M.; Flowers, K.; Eyunni, S.V.K.; Zhang, W.; Redda, K.K.; Soliman, K.F.A. The Antiproliferative Effects of Flavonoid MAO Inhibitors on Prostate Cancer Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 2257. [CrossRef]

- Resta, J.; Santin, Y.; Roumiguié, M.; Riant, E.; Lucas, A.; Couderc, B.; Binda, C.; Lluel, P.; Parini, A.; Mialet-Perez, J. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Prevent Glucose-Dependent Energy Production, Proliferation and Migration of Bladder Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11747. [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Luo, J.; Yeh, S.; You, B.; Meng, J.; Chang, P.; Niu, Y.; Li, G.; Lu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Antonarakis. E.S.; Luo, J.; Huang, C.P.; Xu, W.; Chang, C. The MAO inhibitors phenelzine and clorgyline revert enzalutamide resistance in castration resistant prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 2689. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M., Olivero, J., Choi, H. O., Liao, C. P., Kashemirov, B. A., Katz, J.; Gross, M.E.; McKenna, C.E. Synthesis and anti-cancer potential of potent peripheral MAOA inhibitors designed to limit blood: Brain penetration. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2023, 117425. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Panchuk-Voloshina, N. A one-step fluorometric method for the continuous measurement of monoamine oxidase activity. Anal Biochem 1997, 253, 169-174. [CrossRef]

- Santillo ,M.F,; Liu, Y.; Ferguson, M.; Vohra, S.N.; Wiesenfeld, P.L. Inhibition of monoamine oxidase (MAO) by beta-carbolines and their interactions in live neuronal (PC12) and liver (HuH-7 and MH1C1) cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2014, 28, 403-410. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248-254. [CrossRef]

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2020.09 Chemical Computing Group ULC, 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7, 2020.

- Harvey, M.J.; Giupponi, G.V.; Fabritiis, G.D. ACEMD: Accelerating biomolecular dynamics in the microsecond time scale. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2009,5, 1632–1639. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Methoctramine (1) and its constrained analogues 2-7.

Figure 1.

Methoctramine (1) and its constrained analogues 2-7.

Figure 2.

Effect of polyamine analogues 3-5 and 7 on MAO A and MAO B activity. (A) Effect of different concentrations (1.25-40 μM) of 3-5 and 7 on human recombinant MAO A (◯, circle) or MAO B (□, square) activity. The ratio between the velocity in absence (Vo) and in presence (VI) of the tested compound (Vo/VI ) increase linearly with its concentration (r > 0.99) (B) Effect of incubation time with compounds 4 and 5 on MAO A and B activity. The ratio (Vo/VI ), that is between the velocity in absence (Vo) and in presence (VI) of the tested compound at 2.5 μM concentration was determined after different pre-incubation time (0-30 min) of the enzyme with the inhibitor, before the addition of the substrate (Kynuramine 10μM).

Figure 2.

Effect of polyamine analogues 3-5 and 7 on MAO A and MAO B activity. (A) Effect of different concentrations (1.25-40 μM) of 3-5 and 7 on human recombinant MAO A (◯, circle) or MAO B (□, square) activity. The ratio between the velocity in absence (Vo) and in presence (VI) of the tested compound (Vo/VI ) increase linearly with its concentration (r > 0.99) (B) Effect of incubation time with compounds 4 and 5 on MAO A and B activity. The ratio (Vo/VI ), that is between the velocity in absence (Vo) and in presence (VI) of the tested compound at 2.5 μM concentration was determined after different pre-incubation time (0-30 min) of the enzyme with the inhibitor, before the addition of the substrate (Kynuramine 10μM).

Figure 3.

Mainly competitive inhibition of MAO A and MAO B by compounds 4 and 5. Double reciprocal plots of MAO A (panel A, C) and of MAO B (panel B, D) activity in absence (●, control) and in presence of 4 or 5 (0.25-2 μM). Continuous lines are the results of the linear regression analysis of the plotted data (r > 0.99).

Figure 3.

Mainly competitive inhibition of MAO A and MAO B by compounds 4 and 5. Double reciprocal plots of MAO A (panel A, C) and of MAO B (panel B, D) activity in absence (●, control) and in presence of 4 or 5 (0.25-2 μM). Continuous lines are the results of the linear regression analysis of the plotted data (r > 0.99).

Figure 5.

Cell viability percentage curves as a function of compound concentration (μM). LN-229 cells were incubated for 48h in the presence of compounds 4, 5 and 7 at different concentrations (0.1-5 μM).

Figure 5.

Cell viability percentage curves as a function of compound concentration (μM). LN-229 cells were incubated for 48h in the presence of compounds 4, 5 and 7 at different concentrations (0.1-5 μM).

Figure 6.

MAO activity and effect of compounds 4 and 5 in LN-229 lysates.(A) MAO activity at various substrate concentration. The continuous line is the result of the best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the experimental data. (B) Effect of compounds 4 and 5 on MAO activity in LN229 lysates. The ratio between the velocity in absence (Vo) and in presence (VI) of compounds 4 and 5 increase linearly with its concentration for compound 5 only (r > 0.99).

Figure 6.

MAO activity and effect of compounds 4 and 5 in LN-229 lysates.(A) MAO activity at various substrate concentration. The continuous line is the result of the best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the experimental data. (B) Effect of compounds 4 and 5 on MAO activity in LN229 lysates. The ratio between the velocity in absence (Vo) and in presence (VI) of compounds 4 and 5 increase linearly with its concentration for compound 5 only (r > 0.99).

Scheme 1.

a) 2 M Borane N-ethyl-N-isopropylaniline complex in THF, dry diglyme, reflux, 5h, N2, 32% yield.

Scheme 1.

a) 2 M Borane N-ethyl-N-isopropylaniline complex in THF, dry diglyme, reflux, 5h, N2, 32% yield.

Table 1.

Inhibition constant values and selectivity index (SI) of polyamine analogues 1-7 towards human recombinant MAO A and MAO B. Safinamide, harmine and isatine were taken as reference competitive inhibitors.

Table 2.

Effect of 1-3 and 5-7 on the catalytic efficiency (Vmax/KM) of human VAP-1 and murine SMOX in comparison to those on MAOs.

Table 2.

Effect of 1-3 and 5-7 on the catalytic efficiency (Vmax/KM) of human VAP-1 and murine SMOX in comparison to those on MAOs.

| |

VAP-1 |

SMOX |

MAO A |

MAO B |

| |

Vmax/KM

relative to control |

Vmax/KM

relative to control |

Vmax/KM

relative to control |

Vmax/KM relative to control |

| COMPOUND |

50μM1

|

10μM |

10μM |

10μM |

| 1 |

1 |

0.21 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| 2 |

0.60 |

0.61 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| 3 |

0.37 |

0.47 |

0.95 |

0.64 |

| 5 |

0.48 |

0.46 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

| 6 |

0.50 |

0.21 |

0.22 |

0.30 |

| 7 |

0.55 |

0.16 |

0.71 |

0.75 |

Table 3.

Antiproliferative effect of compounds (2-7) after 48 h of incubation. The Compound 1 and the antitumor drug doxorubicin (DOXO) were taken as reference.

Table 3.

Antiproliferative effect of compounds (2-7) after 48 h of incubation. The Compound 1 and the antitumor drug doxorubicin (DOXO) were taken as reference.

| Compounds |

|

GI50 (μM) 1

|

|

|

| |

Hep G2 |

MCF-7 |

LN-229 |

MeT-5A |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

>20 |

>20 |

>20 |

>20 |

| 2 |

>20 |

5.7±1.3 |

4.6±1.1 |

>20 |

| 3 |

16.8±2.2 |

3.4±1.2 |

2.2±0.9 |

>20 |

| 4 |

1.0±0.2 |

1.1±0.2 |

0.9±0.2 |

2.3±0.4 |

| 5 |

3.2±0.9 |

1.7±0.2 |

0.8±0.1 |

7.1±0.5 |

| 6 |

4.4±1.2 |

2.9±0.8 |

2.0±0.9 |

7.9±1.7 |

| 7 |

0.5±0.1 |

0.8±0.2 |

0.4±0.1 |

1.1±0.4 |

| DOXO |

0.034±0.008 |

0.014±0.001 |

0.012±0.004 |

0.079±0.005 |

Table 4.

Effect of standard inhibitors on MAO activity in LN-229 cells lysates.

Table 4.

Effect of standard inhibitors on MAO activity in LN-229 cells lysates.

| Inhibitor |

Residual MAO activity in lysates |

| Deprenyl1 (5 nM) |

0.74±0.04 |

| Clorgyline1 (5nM) |

0.34±0.1 |

| Pargyline1 (0.5 mM) |

0.03±0.02 |

| Safinamide2 (0.2μM) |

0.66±0.04 |

| Harmine2 (0.2 μM) |

0.37±0.08 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).