1. Introduction

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is now performed in up to 44% of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) surgeries with outside the instructions for use, mostly due to hostile aortic neck anatomies [

1]. Two of the most important predictors of EVAR failure in AAA are infrarenal aortic neck angulation [

2,

3] and short aortic neck [

4,

5], conditions that are associated with a significantly higher rate of early and late type 1A endoleak.

While some studies have reported good early and mid-term outcomes in AAA with severely infrarenal neck angulation [

6,

7], this condition has a tendency to develop type 1A endoleak during long-term follow-up [

8]. The correlation between the severely infrarenal neck angulation and neck length for AAA treated with EVAR has not been studied.

Therefore, we investigated whether the index of infrarenal aortic neck angulation and length has any effect on intraoperative complications and outcomes after EVAR. We aimed to determine the association of infrarenal aortic neck angle in severely angulated aortic neck and length to find the optimal cutoff value for prediction of intra-operative neck complications after EVAR and to compare early and late outcomes between groups classified by the aortic neck angle-length index.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient selection

All intact infrarenal AAA patients with severe neck angulation (infrarenal neck angle greater than 60°) who underwent standard EVAR at our institute between October 2010 and October 2018 were enrolled in this study. Patients who lacked preoperative computed tomographic angiography (CTA) data were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (SIRB) (COA no. Si 499/2018). Data were collected from a prospectively maintained AAA database through a retrospective review of medical records. Demographic data and clinical specific profiles were recorded including age, sex, and medical co-morbidities. In addition, American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) physical status classification estimated by an anesthesiologist was also documented.

2.2. Pre-operative CT scan measurement

Preoperative assessment of aneurysm morphology was performed using multidetector CTA with thin-slice (1 mm) imaging. Accurate measurements were determined using post-processing 3D imaging software, such as Osirix MD (Pixemo, Geneva, Switzerland). The aortic neck angle and length measurement were determined by two observers (KC and TS). The two investigators performed the angle and length measurement independently and in a random order. Infrarenal aortic neck angulation was defined as the maximal angle from all views between the proximal aortic neck and the longitudinal axis of the aneurysm [

9]. Infrarenal aortic neck length was defined as the first diameter showing growth of 10% over the diameter at the most caudal renal artery [

10]. Conical neck was defined as gradual neck dilatation of ≥2 mm within the first 10 mm after the most caudal renal artery [

11]. Other AAA morphology were recorded including maximal diameter, suprarenal neck angulation, ≥50% circumferential proximal neck thrombus (≥2 mm thick), ≥50% calcified proximal neck, AAA length (the length from the lowest renal artery to aortic bifurcation). For determination of intra-observer reliability, the co-author (TS) measured both the infrarenal aortic neck angle and neck length twice with an interval of 1 to 2 weeks. The aortic neck angle and neck length were measured by two observers (KC and TS) for evaluating the inter-observer reliability. Details of these measurements were reviewed separately without the knowledge of the clinical outcomes of the patients to avoid measurement bias.

2.3. Definitions and outcomes measurement

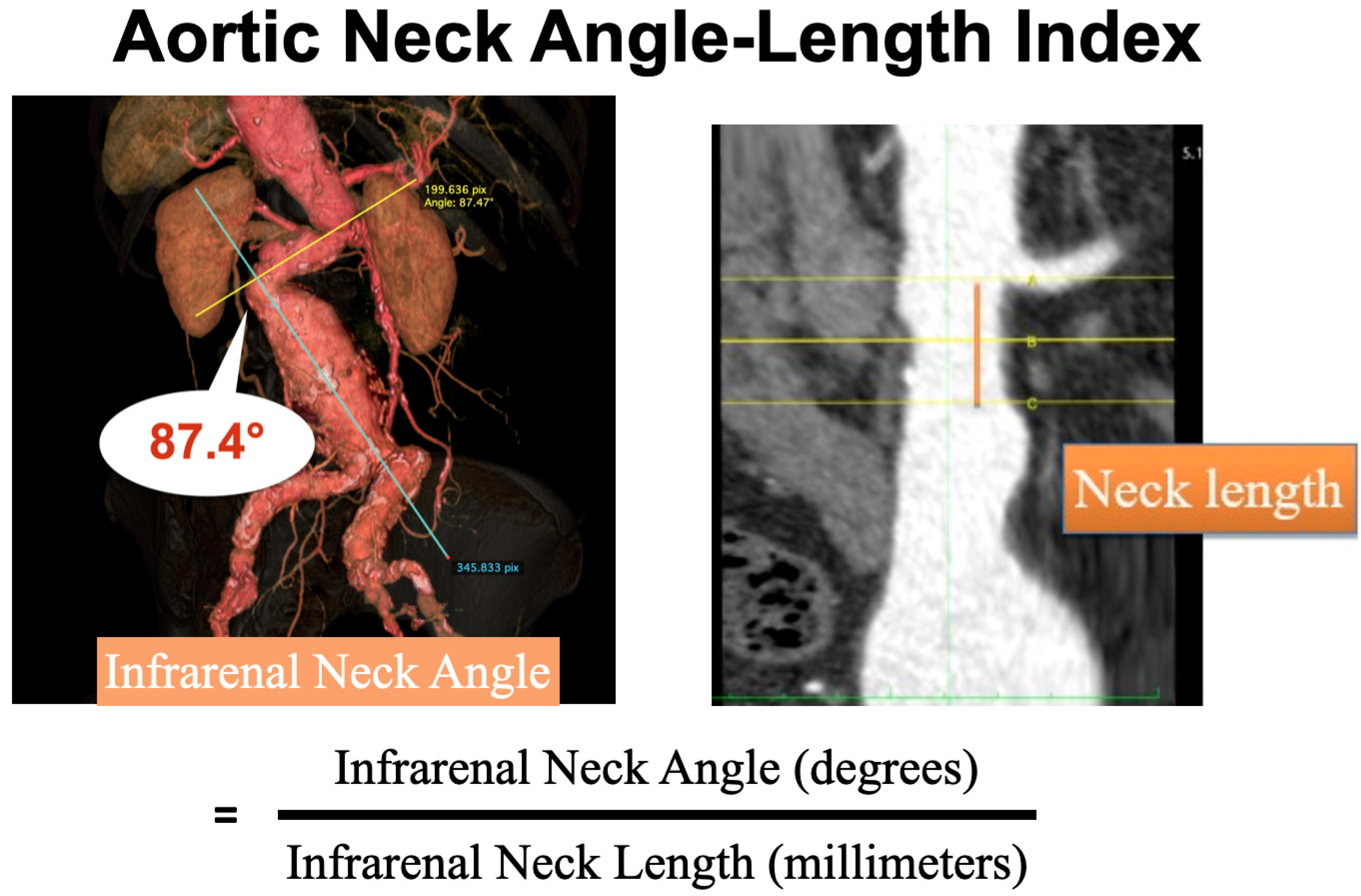

The aortic neck angle-length index was calculated using the average of infrarenal neck angle (degree) divided by average of the infrarenal aortic neck length (millimeter) (

Figure 1). Intra-operative neck complications were detected by completion angiography after the endografts were deployed completely. We focused on four types of intraoperative neck complications. Type 1A endoleak was defined as extravasation of contrast between the prosthesis and aneurysm wall from proximal neck [

12]. Endograft migration was determined by displacement of the stent graft caudally, measuring the distance from the lowest renal artery and the most cephalad portion of the stent graft > 10 mm [

12]. Renal artery occlusion was defined as partial or complete occlusion of one or bilateral renal arteries. Aortic dissection was determined as retrograde aortic dissection.

Intraoperative adjunctive neck procedure was defined as any other procedure designed to augment the effects of the principal procedure, especially for management of intra-operative neck complications or an otherwise unsatisfactory outcomes such as proximal extension cuff and Palmaz stent placement (Cordis Corp, Miami Lakes, FL, USA). Operative details were comprised of the brand of aortic stent graft product, procedure time (minutes), fluoroscopic time (minutes), volume of contrast usage (milliliters), and intra-operative blood loss (milliliters).

In-hospital death or any death or complications occurring during the first 30-day postoperative period were analyzed. Complications were defined according to a previous report by Chaikof EL et al. [

12].

All patients undergoing EVAR were followed according to a predetermined protocol that included a CTA at 1, 6, 12 months and then every 12 months thereafter. In patients with stage IV or V chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2), the aortic stent graft was evaluated via standard duplex ultrasound performed by a radiologist. All radiologic exams done after endovascular repair were reviewed for migration, endoleak, graft limb occlusions, the aneurysm sac size, and re-interventions.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The required sample size for point biserial correlation was conducted in G*Power 3.1.9.2 using a significance level of 0.05, a power of 0.90, a medium effect size (ρ = 0.3), and a two-tailed test. Based on the assumptions, the desired sample size was 109. Because there is no definite rule for sample size in latent profile analysis, Wurpts et al. [

13] recommended a minimum of 100 subjects as a reasonable sample size, and so all subjects who met the inclusion criteria were recruited.

Data were recorded and analyzed using PASW Statistics 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. Quantitative data were described by mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and range, as appropriate. Qualitative data were expressed by number and percentage. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate intraobserver reliability using two-way mixed effects model and interobserver reliability using two-way random effects model. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to classify groups of patients based on aortic neck angle-length index using the R package mclust [

14]. Four indices were used to select the correct number of latent classes, i.e., log-likelihood, Bayesian information criterion (BIC), integrated complete-data likelihood, and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT). Lower BIC and integrated complete-data likelihood values coupled with higher log-likelihood values showing and indicating a better fitting model. The BLRT was used to compare successive model, where a significant change in -2 log-likelihood indicated that the model with the greater number of classes provided a better fit to the data. Point biserial correlation was used to examine the relationship between aortic neck angle-length index score and two classes of aortic neck angle-length groups classified by LPA. Kaplan-Meier method was performed to estimate overall survival time and re-intervention free time. Log rank test or Breslow test was used to compare overall survival and re-intervention free time between aortic neck angle-length index groups.

3. Results

From October 2010 to October 2018, 759 patients were diagnosed with intact AAA at our institution. Open surgical repair, fenestrated or chimney EVAR procedure, and AAA without severely angulated infrarenal neck were excluded. One hundred and fifty-five of these patients presented with a severely angulated neck of AAA treated with EVAR. Forty patients were not included in this study due to lack of preoperative CTA (n = 30), using other brands of aortic stent graft (n = 7), using funnel technique (n = 2) and previous open surgical repair (n = 1). In total, 115 patients were enrolled in our study.

3.1. Intraobserver and Interobserver reliability

Intraobserver reliability of the author on aortic neck length had an ICC of 0.988 (95% CI; 0.982-0.992) and infrarenal angle showed excellent reliability with an ICC of 0.986 (95% CI; 0.981-0.991). Interobserver reliability of two observers on neck length showed excellent and moderate reliability with an ICC of 0.969 (95% CI; 0.954-0.979) and aortic neck angle with an ICC of 0.739 (95% CI; 0.632-0.816).

3.2. Aortic Neck Angle-Length index

Aortic neck angle-length index was calculated from the average of infrarenal neck angle (degree) divided by the average of neck length (millimeter) for each patient (

Figure 1). The median of the aortic neck angle-length index was 3.2 (range 1.1-14.3). LPA classified aortic neck angle-length index into two groups, i.e., aortic neck angle-length index ≤ 4.8 [Group 1, (G1)] and aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 [Group 2, (G2)], which represented 95 (82.6%) and 20 (17.4%) patients, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic variables (

Table 1). Most of the patients were male (70.5% G1 and 80% G2), and the mean patient age was 77.1 ± 6.4 (G1) and 75.7 ± 7.2 (G2) years, respectively. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity, present in almost three-quarters (80% G1 and 75% G2), followed by dyslipidemia (45.3% G1 and 40% G2).

3.3. AAA morphology

All patients had a fusiform type aneurysm. There were no statistically significant differences in the median of the suprarenal neck angle (43.6° G1 vs 40.5° G2, P = 0.912) or the mean of the infrarenal neck angle (82.9° G1 vs 89.7° G2, P = 0.108). The aortic neck length was significantly shorter in Group 2 (34.1 mm vs 14.0 mm, P < 0.001). The other aneurysm morphologies were not statistically significantly different (

Table 2).

3.4. Intraoperative outcomes

For intraoperative outcomes (

Table 3), the Group 2 had significantly higher intraoperative neck complications rates than Group 1 (21.1% G1 vs 55% G2, P = 0.005), especially type IA endoleak (10.5% G1 vs 40% G2, P < 0.003). There was no significant difference in endograft migration and renal artery coverage between the two ANAL index groups.

In Group 2, the adjunctive neck procedures were performed significantly more frequently (18.9% G1 vs 60% G2, P = < 0.001). The proximal extension cuff placements were more common in group 2 (7.4% G1 vs 25% G2, P = 0.034), and Palmaz stent placements were more common in Group 2, but the difference was not without statistically significant (9.5% G1 vs 20% G2, P = 0.237).

3.5. Operative details

The Endurant, Zenith, and Treovance devices were used to performed EVAR, and there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. Mean of procedure time (minutes), fluoroscopic time, volume of contrast usage and intraoperative blood loss were all higher in the aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 (G2), but these did not reach statistical significance. Operative details are summarized in

Table 3.

3.6. Early postoperative outcomes

There was no statistically significant difference in 30-day complications (30.5% G1 vs 40% G2, P = 0.575), or in deployment-related complications (6.3% G1 vs 10% G2, P = 0.626). In eight patients with deployment-related complications, two aortic dissections occurred within 30 days, one patient required open repair. Four patients had access site hematoma, and one required surgical evacuation. One patient had distal embolization, treated with transfemoral thromboembolectomy and another patient had a dissection of the right external iliac artery with conservative treatment.

There was one procedure-related death in Group 1 from a retrograde aortic dissection on postoperative day 8, and one patient in the Group 2 died from severe colonic ischemia on postoperative day 2. There was no statistically significant difference in the 30-day mortality rate between the two groups (1.1% G1 vs 5% G2, P = 0.319). Two patients in Group1 died after 30 days, one from pulmonary infection with severe sepsis and another from multiple organ failure. One patient in the Group 2 died from pulmonary infection with severe sepsis on postoperative day 85 (3.1% G1 vs 10% G2, P = 0.439). The median length of stay was not statistically significantly different between two groups (7 days, G1 vs 8 days, G2, P = 0.401). Post-operative outcomes are shown in

Table 4.

3.7. Late outcomes

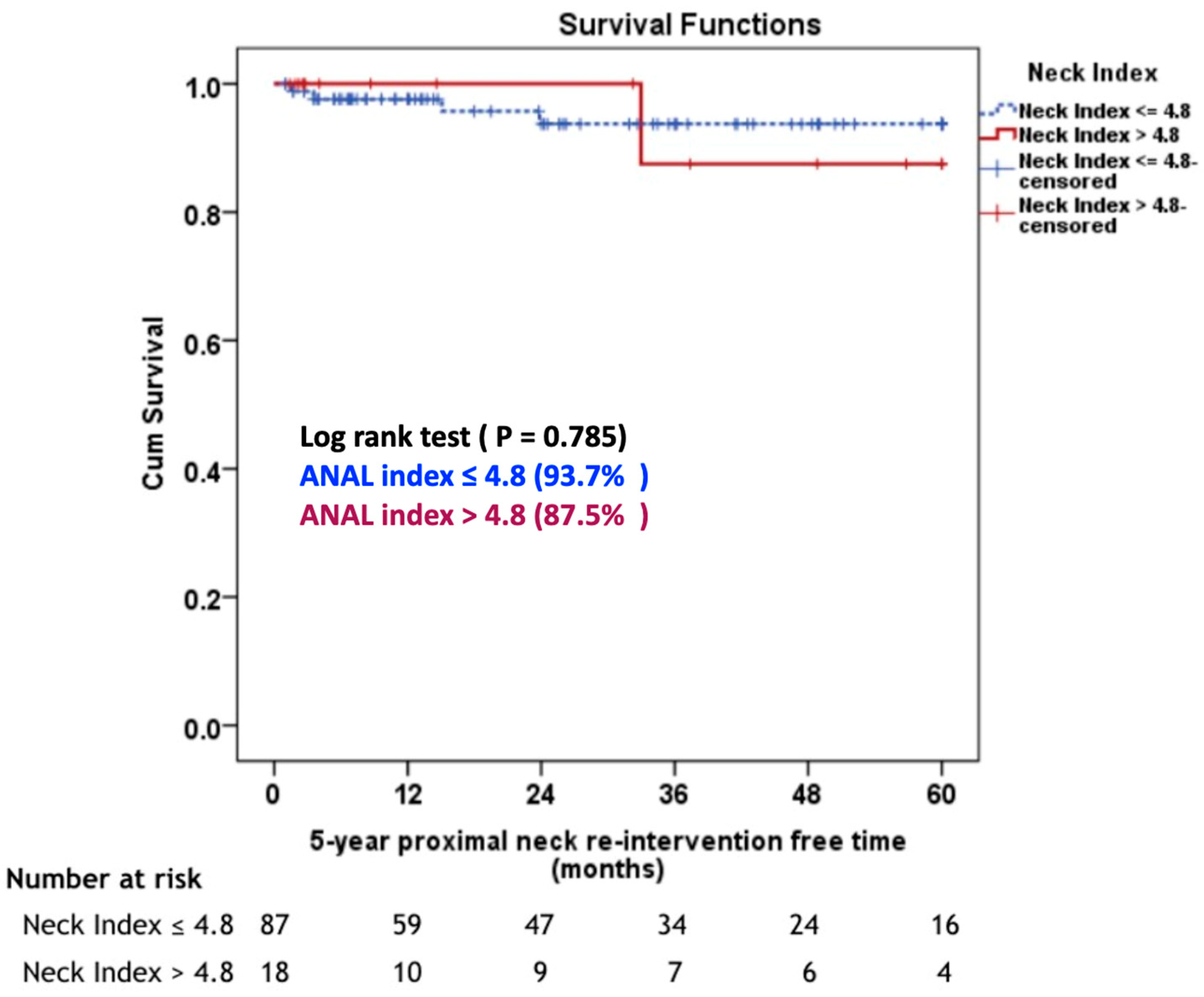

The median follow-up duration was 36.6 months (range: 1-110 months). The 5-year proximal neck re-intervention free rate, there was not statistically significant different between aortic neck angle-length index ≤ 4.8 group and aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 group (93.7% G1 vs 87.5% G2, P = 0.785), (

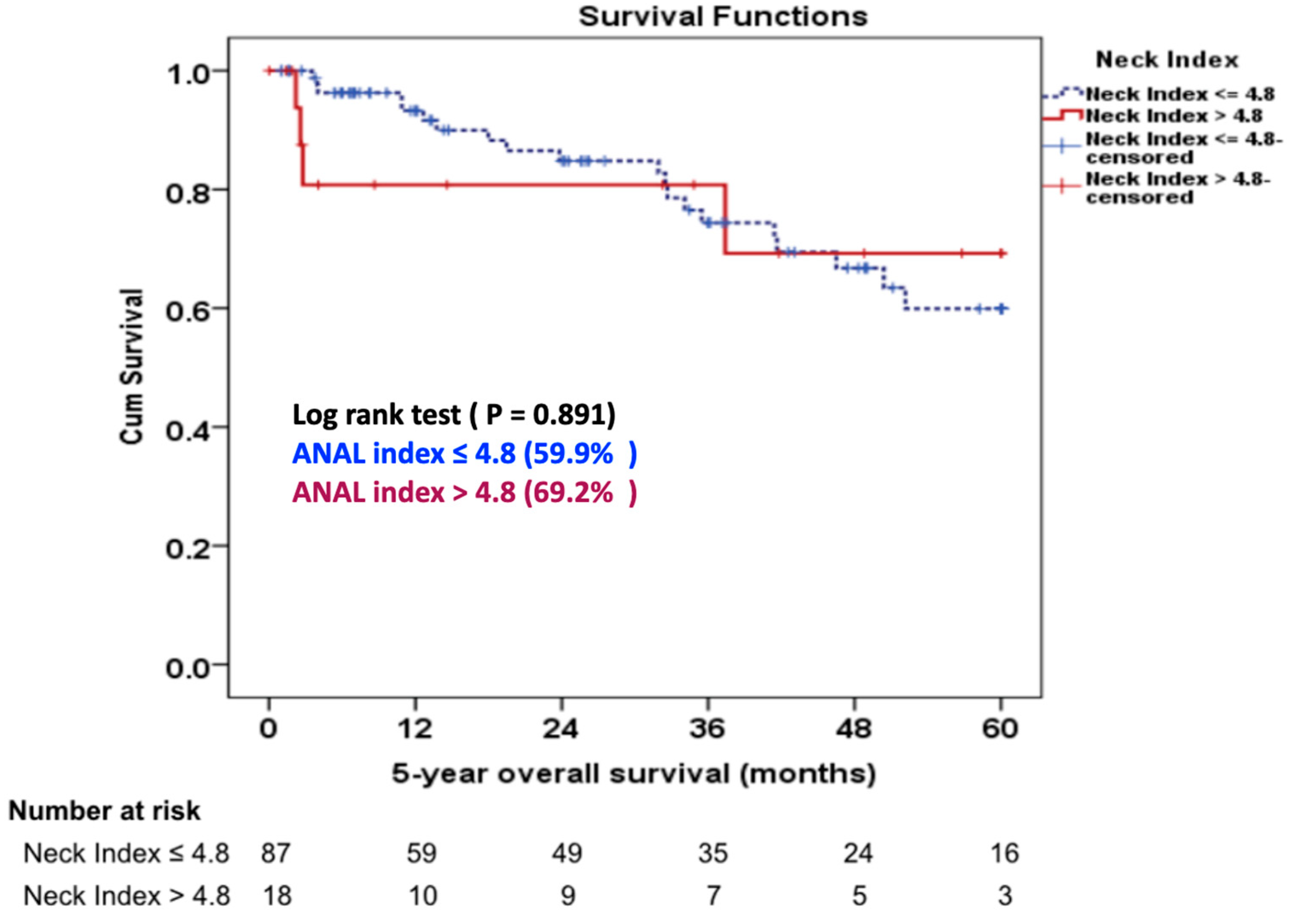

Figure 2). Four (4.2%) patients in Group 1 required proximal neck re-intervention due to a type 1A endoleak (n = 3) and type 3B endoleak (n = 1). One patient had a type 3B at 15 months postoperatively at the main body of stent graft due to the pressure effect of Palmaz stent and was treated successfully with a proximal extension cuff. Three patients developed type 1A endoleak during follow-up. One patient required an aortic extension cuff at four months and two patients needed a Palmaz stent at two and 24 months, respectively. In the Group 2, one (5%) patient underwent a proximal extension cuff placement due to a ruptured AAA from a type 1A endoleak at 33 months postoperatively. There was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year overall survival rate between the two groups (59.9% G1 vs 69.2% G2, P = 0.337), (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The suitability of EVAR is usually based on the manufacturer’s the instructions for use. Strict adherence to the standard requirements generally leads to good outcomes. EVAR in hostile neck anatomy, particularly in short and severe neck angulation, is associated with poor early and late outcomes [

3,

5]. We measured a correlation between aortic infrarenal neck angulation and aortic neck length, showing a higher rate of intraoperative neck complications and immediate adjunctive neck procedures in patients with an aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8. Nevertheless, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of re-intervention, or survival between the two groups at late follow-up.

In general, the performance of the EVAR device depends on fixation and seal [

15]. Leurs et al. [

5] found that a neck length < 15 mm was associated with higher rates of early and late proximal type IA endoleak. Hobo et al. [

3] reported that severe infrarenal neck angulation was associated with higher rates of early type 1A endoleak and graft migration. Similarly, the study by AbuRahma et al. [

11] found that EVAR in the presence of hostile neck morphology, including neck length < 10 mm and infrarenal neck angulation > 60 degrees, demonstrated a higher rate of intraoperative 1A endoleak, and immediate adjunct neck procedures than in favorable aortic neck anatomy.

Our study provided additional insight into the effect of the aortic neck length and angulation on EVAR outcomes. Consistent with a recent meta-analysis, we found that patients with an aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 (G2) have higher rates of immediate adjunct neck procedures in short aortic neck length < 15 mm, and/or neck angulation > 60 degrees [

16]. No study has reported this association or proposed an optimal cutoff value of the aortic neck angle-length index for prediction of intra-operative neck complications and immediate adjunct neck procedures after EVAR in AAA with severe neck angulation.

We found that patients with a short neck and an aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 had significantly higher intra-operative neck complications rates complications (21% G1 vs 55% G2, P = 0.005) and immediate adjunct neck procedures (18.9% G1 vs 60% G2, P < 0.001). All patients in both groups with intra-operative type 1A endoleak were successfully treated with proximal extension cuff and/or Palmaz stent placement to achieve proximal seal. This finding is consistent with the meta-analysis by Antoniou GA et al. [

16] where adjunctive neck procedures were needed in 22% of AAA with hostile neck anatomy. In addition, short aortic neck length may be a crucial factor to determine the neck complications and the requirement for adjunct neck procedure during EVAR in AAA with severely angulated neck [

5,

17]. The findings of intraoperative neck complications in our study also support the repair of type 1A endoleak with a large balloon-expandable Palmaz stent that Cox et al. [

18] reported to be beneficial for use in hostile aortic neck, including proximal aortic neck angle > 60 degrees. Despite the danger of type 1A endoleak, some studies [

19,

20] have suggested conservative management only in patients with anatomy considered suitable for EVAR, and if an adequately oversized stent graft had been optimally deployed. All type 1A endoleak in our study developed in patients with severely angulated neck; therefore, we usually performed adjunct neck procedures for immediate type 1A endoleak repair.

Procedure time, fluoroscopic time, volume of contrast usage and intra-operative blood loss were all higher in the aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 group (G2), but without reaching statistical significance, perhaps due to an insufficient number of patients. Patients with aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 (G2) had higher rates of intra-operative neck complications and needed more adjunctive neck procedures. Therefore, the procedure time, fluoroscopic time, contrast usage, and blood loss were higher than in the aortic neck angle-length index ≤ 4.8 (G1). Recently published studies have also reported increases in these operative details in the presence of hostile neck anatomy [

17,

21].

No statistically significant difference in perioperative mortality was found between the two groups (1.1% G1 vs 5% G2, P = 0.319), which agrees with earlier reports on hostile neck anatomy leading to 30-day mortality between 1.8% and 3% [

11,

22]. We measured freedom from five-year reintervention was observed in 93.7% of patients in the aortic neck angle-length index ≤ 4.8 (G1), and in 87.5% of the aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 (G2), (P = 0.785). This is consistent with a study of Oliveira NF et al. [

7] that reported a 95% of freedom from four-year reintervention in severely angulated neck and with Aburahma AF et al. [

11] who reported an 85% of freedom from four-year reintervention in hostile aortic neck anatomy. The estimated overall survival rate at five years was 59.9% in patients with the aortic neck angle-length index ≤ 4.8 (G1), and 69.2% in the aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 (G2), respectively (P = 0.337). Surprisingly, few studies have addressed long-term survival in AAA with severely angulated neck. Oliveira et al. [

8] described 7-year survival rates of 44.3% for the AAA with severely angulated neck.

A limitation of our study is its small sample size and retrospective, observational methodology. Because we could not provide pre-operative CT scans for all patients, some patients were excluded from this study. Different endograft devices were used for EVAR. A longer-term prospective study would allow us to confirm our findings.

5. Conclusions

Patients with an aortic neck angle-length index > 4.8 had higher risk of intra-operative neck complications and adjunctive neck procedures compared with patients with an aortic neck angle-length index ≤ 4.8 patients. The 5-year proximal neck re-intervention free rate and the 5-year overall survival were not statistically different between groups. The aortic neck angle-length index is a reliable predictor of intra-operative neck complications and to prepare back-up devices for immediate adjunct neck procedures during EVAR in AAA with severely angulated neck.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Surut Chalermjitt, BS, RN, Miss Aphanan Phiromyaphorn, BS, RN, and Miss Wannaporn Paemueang BS, RN for their assistance with data collection. We also thank Dr. James Mark Simmerman, for his technical editing.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Marone, E.M.; Freyrie, A.; Ruotolo, C.; Michelagnoli, S.; Antonello, M.; Speziale, F.; Veroux, P.; Gargiulo, M.; Gaggiano, A. Expert Opinion on Hostile Neck Definition in Endovascular Treatment of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms (a Delphi Consensus). Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 62, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockley, M.; Hadziomerovic, A.; van Walraven, C.; Bose, P.; Scallan, O.; Jetty, P. A new "angle" on aortic neck angulation measurement. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 70, 756–761.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobo, R.; Kievit, J.; Leurs, L.J.; Buth, J. Influence of Severe Infrarenal Aortic Neck Angulation on Complications at the Proximal Neck Following Endovascular AAA Repair: A EUROSTAR Study. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2007, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuRahma, A.F.; Campbell, J.; Stone, P.A.; Nanjundappa, A.; Jain, A.; Dean, L.S.; Habib, J.; Keiffer, T.; Emmett, M. The correlation of aortic neck length to early and late outcomes in endovascular aneurysm repair patients. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 50, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leurs, L.J.; Kievit, J.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Nelemans, P.J.; Buth, J. Influence of Infrarenal Neck Length on Outcome of Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2006, 13, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos Goncalves, F.; de Vries, J.P.; van Keulen, J.W.; et al. Severe proximal aneurysm neck angulation: early results using the Endurant stentgraft system. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 41, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, N.F.; Bastos Gonçalves, F.M.; de Vries, J.P.; Ultee, K.; Werson, D.; Hoeks, S.; Moll, F.; van Herwaarden, J.; Verhagen, H. Mid-Term Results of EVAR in Severe Proximal Aneurysm Neck Angulation. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015, 49, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, N.F.G.; Gonçalves, F.B.; Hoeks, S.E.; van Rijn, M.J.; Ultee, K.; Pinto, J.P.; Raa, S.T.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; de Vries, J.-P.P.; Verhagen, H.J. Long-term outcomes of standard endovascular aneurysm repair in patients with severe neck angulation. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 1725–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Keulen, J.W.; Moll, F.L.; Tolenaar, J.L.; Verhagen, H.J.; van Herwaarden, J.A. Validation of a new standardized method to measure proximal aneurysm neck angulation. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 51, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.P.; Fillinger, M.F.; Morrison, T.M.; Abel, D. The influence of gender and aortic aneurysm size on eligibility for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 54, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbuRahma, A.F.; Campbell, J.E.; Mousa, A.Y.; Hass, S.M.; Stone, P.A.; Jain, A.; Nanjundappa, A.; Dean, L.S.; Keiffer, T.; Habib, J. Clinical outcomes for hostile versus favorable aortic neck anatomy in endovascular aortic aneurysm repair using modular devices. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 54, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaikof, E.L.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; Harris, P.L.; White, G.H.; Zarins, C.K.; Bernhard, V.M.; Matsumura, J.S.; May, J.; Veith, F.J.; Fillinger, M.F.; et al. Reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002, 35, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurpts, I.C.; Geiser, C. Is adding more indicators to a latent class analysis beneficial or detrimental? Results of a Monte-Carlo study. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrucca, L.; Fop, M.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. mclust 5: Clustering, Classification and Density Estimation Using Gaussian Finite Mixture Models. The R Journal 2016, 8, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bock, S.; Iannaccone, F.; De Beule, M.; Vermassen, F.; Segers, P.; Verhegghe, B. What if you stretch the IFU? A mechanical insight into stent graft Instructions For Use in angulated proximal aneurysm necks. Med Eng. Phys. 2014, 36, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, G.A.; Georgiadis, G.S.; Antoniou, S.A.; Kuhan, G.; Murray, D. A meta-analysis of outcomes of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients with hostile and friendly neck anatomy. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broos, P.P.; Stokmans, R.A.; van Sterkenburg, S.M.; Torsello, G.; Vermassen, F.; Cuypers, P.W.; van Sambeek, M.R.; Teijink, J.A. Performance of the Endurant stent graft in challenging anatomy. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 62, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.E.; Jacobs, D.L.; Motaganahalli, R.L.; Wittgen, C.M.; Peterson, G.J. Outcomes of Endovascular AAA Repair in Patients with Hostile Neck Anatomy Using Adjunctive Balloon-Expandable Stents. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2006, 40, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millen, A.M.; Osman, K.; Antoniou, G.A.; McWilliams, R.G.; Brennan, J.A.; Fisher, R.K. Outcomes of persistent intraoperative type Ia endoleak after standard endovascular aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos Gonçalves, F.; Verhagen, H.J.; Vasanthananthan, K.; Zandvoort, H.J.; Moll, F.L.; van Herwaarden, J.A. Spontaneous Delayed Sealing in Selected Patients with a Primary Type-Ia Endoleak After Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014, 48, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinsakchai, K.; Suksusilp, P.; Wongwanit, C.; Hongku, K.; Hahtapornsawan, S.; Puangpunngam, N.; Moll, F.L.; Sermsathanasawadi, N.; Ruangsetakit, C.; Mutirangura, P. Early and late outcomes of endovascular aneurysm repair to treat abdominal aortic aneurysm compared between severe and non-severe infrarenal neck angulation. Vascular 2020, 28, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torsello, G.; Troisi, N.; Donas, K.P.; Austermann, M. Evaluation of the Endurant stent graft under instructions for use vs off-label conditions for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 54, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).