1. Introduction

The starting material plays a very important role in the formation of geopolymers. Researchers have conducted a number of studies to develop different methods to improve the durability of geopolymers [

1]. Currently, a very wide range of materials are used in the geopolymerisation process. These include pozzolanic materials, silicon-rich materials such as fly ash, slag, and aluminium-rich materials [

2]. In addition, researchers are currently trying to find the golden (optimal) solution to minimise the amount and cost of energy used and reduce carbon emissions. To this end, they are looking for bio-additives such as molasses or cotton to further accelerate the curing process at ambient temperature and increase the mechanical properties of the resulting geopolymer mass. Some of the solutions under development related to the modification of the material composition will be presented in the following subsection [

3].

Due to their good mechanical properties, resistance to aggressive environments and thermal resistance, geopolymers have found applications in manufacturing (Figure 1.1) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

1. structural components,

2. columns/beams,

3. sewage pipes,

5. insulation and multilayer wall construction,

6. geopolymer-cement concrete for highway infrastructure.

Figure 1.1.

Most known applications of geopolymers.

Figure 1.1.

Most known applications of geopolymers.

Due to the high costs associated with the use of energy in the curing of geopolymer mass in dryers and heating chambers, researchers in recent years have started to look for a way to reduce the costs and the amount of energy used. As a result, they looked for natural ingredients to speed up the curing process and improve the mechanical properties of the resulting geopolymer mass. They started adding natural additives, i.e. cotton, honey and molasses varieties, i.e. cane molasses, beet molasses. The addition of cane molasses and beet molasses was used in the studies described in the following sections [

10,

13].

Molasses is a by-product of sugar extraction [

14]. It has a brown colour and its consistency resembles brown syrup. The substance is a multicomponent system that differs in the composition of the starting raw material.

In its composition, molasses has fermentable sugars, i.e. glucose, sucrose or fructose, substances that have not been precipitated in the purification process, and those that originate from enzymatic or chemical reactions. Important components of molasses are also micronutrients, i.e. potassium, calcium, sodium, iron, and a number of important bioactive compounds, which are proteins, vitamin B complex and biotin [

15]. It is usually used in animal nutrition because it is a source of energy and has a positive effect on milk fat content [

16,

17]. Due to the presence of micronutrients, it can be used in medicine, e.g. to treat diseases related to anaemia, precisely because of the presence of iron in its composition [

16,

18,

19,

20].

Bio-additives such as molasses have a positive effect on the structure of the geopolymer and on the curing during the geopolymerisation process, due to the presence of sugars, organic substances and minerals, as they are an additional source of reactive chemicals. The most important aspects of the influence of bio-additives on the geopolymer structure include:

(a) The rate of curing of the geopolymer mass, which is related to the presence of hydroxide anions, which are released during the reaction and act as activators. These anions accelerate the geopolymerisation reaction [

21].

(b) Increase in mechanical properties, which can be caused by:

- Strengthening of the geopolymer structure - there is a better interaction between the component particles. The molasses is then likely to act as a filler/binder, which results in an increase in the mechanical properties and hardness of the test material [

22],

- Better compactness, which is due to the fact that molasses reduces the number of pores in the structure, leading to increased density and strength,

- Increased cross-reactions - molasses has a high amount of sugars in its structure, which lead to increased cross-reactions. They cause more durable chemical bonds and thus improve the strength of the material [

10,

14,

16,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

(c) Reduction in H2O demand [

4,

26],

(d) Improved microstructure of the geopolymer through compact packing and improved reaction with fly ash, resulting in a dense microstructure that enhances the geopolymerisation reaction [

27],

(e) Improved roughness, by reorganising the geopolymer gel structures in the samples [

25,

28],

(f) Effect on the porous structure - molasses occupies free spaces

in the structure of the geopolymer, therefore materials modified with molasses have better mechanical properties than materials without molasses [

25].

The addition of nanosilica reduces the setting time of geopolymers. This is due to the high activity of the nanoparticles, which promotes the speed of the reaction. The bonding time also decreases as the solid/liquid ratio increases. It also increases the lifetime of structures under harsh chemical conditions, e.g. in the presence of sulphuric acid. This is due to the dense structure, which equates to lower porosity and permeability [

29,

30].

Carbon nanotubes are used as reinforcement for geopolymers. Unique properties such as high elastic modulus and tensile strength make them ideal for this [

29].

In the case of a geopolymer created using metakaolin, multi-walled carbon nanotubes improve the mechanical strength of the nanocomposite. Their addition to the alkali-activated geopolymer mortar sample provides additional nucleation sites for geopolymer formation and accumulation [

29]. The coating of SiO2 carbon nanotubes allows the production of geopolymer nanocomposites. Such nanotubes consist of a high content of amorphous silicon dioxide. This causes the diffusion and transport of dissolved silicon complexes occurring during geopolymerisation to create a strong interfacial interaction between the carbon nanotube and the geopolymer matrix.

A similar application to carbon nanotubes may be nanoclay. Its presence has a positive effect on the physical, mechanical properties and durability of flax fibre-reinforced geopolymer composites [

29].

It accelerates geopolymerisation, reduces the alkalinity of the system and increases the gelation of the geopolymer. The presence of nanoclay particles, by reducing the alkalinity of the substrate, reduces the degradation of natural fibres. It also produces a greater amount of geopolymer gel, increases the density of the matrix and fibre-ossein adhesion, which improves the mechanical properties of geopolymers [

29,

31,

32].

2. Materials and Methods

The mineralogical composition of the raw materials and geopolymers was determined by a PANalytical Aeris diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) using Cu Kα radiation, scanning range from 10◦ to 100◦ 2θ, step size 0.003◦ (2θ), and measurement time per step of 340 s. High Score Plus software version 4.8 (PANalytical) equipped with the ICDD (International Center for Diffraction Data, PDF4+) database was used to identify the diffraction patterns. The density of the produced geopolymers was calculated by the geometric method as the ratio of the mass to the volume of the samples. The masses of the specimens were measured using a Radwag XA 60/220/Y balance (RADWAG, Radom, Poland). The samples intended for use in testing the mechanical properties had dimensions of 50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm, and 200 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm for the compressive and flexural strength tests, respectively. Compressive strength tests were carried out according to the PN-EN 12390-3:2019 standard using a MATEST 3000 kN machine (MATEST S.p.A., Arcore, Italy). Flexural strength tests were performed in accordance with the PN-EN 12390-5:2019 standard on a concrete press (MATEST S.p.A., Arcore, Italy).

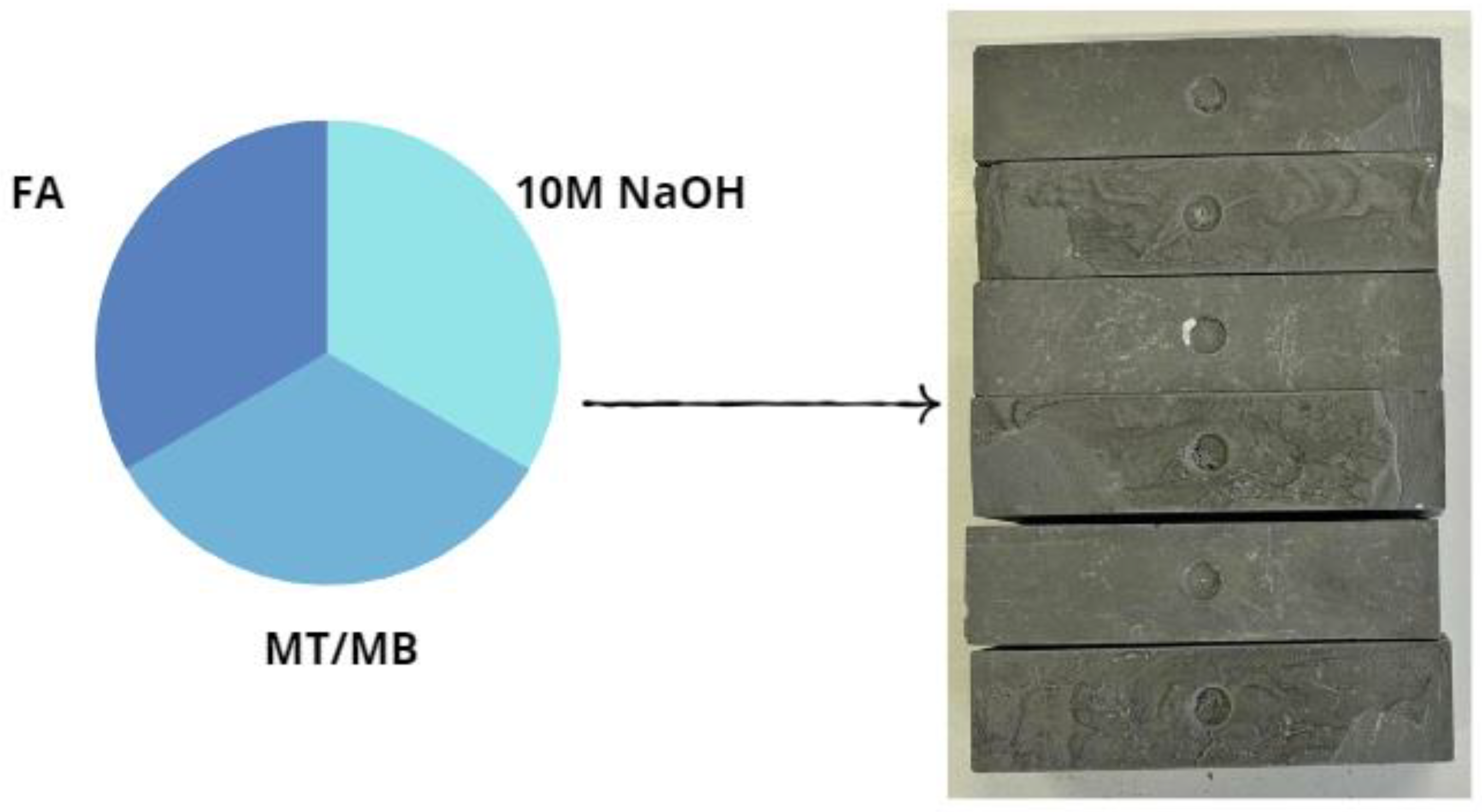

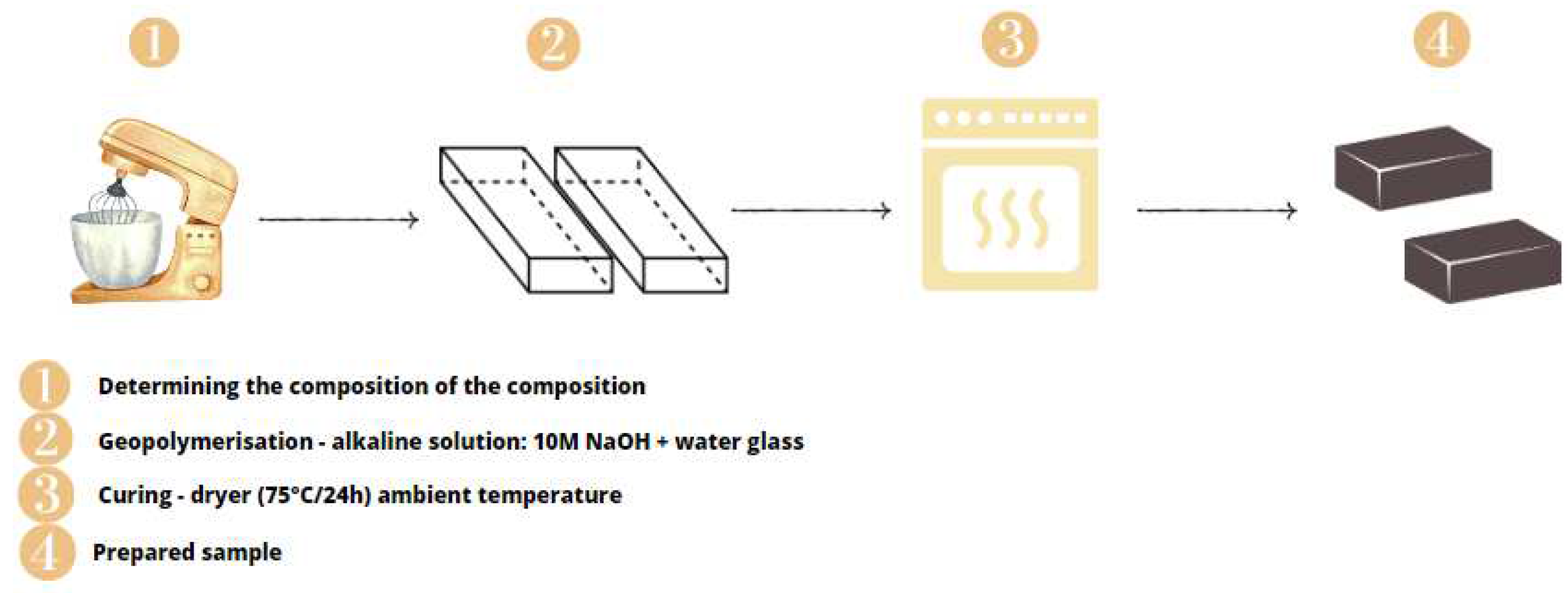

Tahseen Ashiq Bhat and his team studied the effects of molasses on the behaviour of the geopolymer and noted that molasses had an effect on improving the workability and strength of the geopolymer studied, so it was decided to modify the composition with bioadditives such as cane molasses (MT) made by Eko-Natural and beet molasses (MB) made by Harison. The process of preparing the geopolymers modified with bioadditives of plant origin started with determining the composition of the composition, which is shown in Table 1.1. 5 types of specimens were created for the tests, the preparation process of which is shown in Figure 2.1. The amount of ingredients given in Table 2.1 was .sufficient to prepare 6 specimens with dimensions of 50x50x150mm.

Table 2.1.

Composition of tested samples.

Table 2.1.

Composition of tested samples.

| Label of sample |

Fly ash [kg] |

MT

[g] |

MB

[g] |

Alkaline solution

[ml] |

| Ref. |

1,5 |

- |

- |

650 |

| MT0,8 |

14,4 |

- |

| MB0,8 |

- |

14,4 |

| MT1,6 |

28,8 |

- |

| MB1,6 |

- |

28,8 |

Figure 2.1.

Schematic of the geopolymers produced.

Figure 2.1.

Schematic of the geopolymers produced.

Figure 2.2.

Preparation of geopolymer samples.

Figure 2.2.

Preparation of geopolymer samples.

By analysing Table 2.1, it can be seen that the reference sample consisted of fly ash and alkaline solution only. 1.5 kg of class F fly ash from the Skawina CHP Plant was measured on a technical scale. The ash was then poured into a mixer and slowly started to mix. After one minute, a measured solution of 10M sodium hydroxide with water glass (650ml), which was prepared in a When the mixture was clear and there was no fly ash on the bottom fly ash was deposited at the bottom, the stirring speed could be increased. The mixed mass had a very thick consistency and was plastic. The ready mass was was transferred into prepared moulds measuring 50x50x200mm, and then transferred to the laboratory vibrating table in order to get rid of air bubbles. of air bubbles. The finished samples (6 pieces) were placed in a drying oven at 75oC for 24 hours. Then, a second batch of samples was prepared, which were cured at ambient temperature.

The samples with cane and beet molasses were prepared in the same way as the reference samples, but before starting, the appropriate amount of molasses from each type had to be measured: 14.4 g (0.8% by molasses) and 28.8 g (1.6% by molasses). Molasses is very dense so, to dilute it, an alkaline solution was added and then, after mixing the fly ash with 10M NaOH, a biodigester was added and a change in the texture of the geopolymer mass was noticed. Compared to the consistency of the reference samples, the mass with molasses added became more fluid. Once the material was placed in the moulds, it was noticed that a curing process had started on the surface of the sample. The next step was to remove the samples from the vibrating table and start the curing process in the dryer and at ambient temperature.

a) Compressive strength

This measurement is carried out on cubic or cylindrical specimens [

33]. It is intended to represent the resistance of the material to external forces that can cause deformation and stress [

34].Compressive strength varies depending on factors related to:

- the quantity and quality of the components,

- the age of the sample,

- water content,

- production technology [

35].

EN 12390-3:2019-07 describes the method for performing compressive strength. According to the guidelines, the test specimens can be cube or cylinder shaped. The test consists of loading the specimen to a critical value at which the test material breaks. The value of the read load allows the calculation of the compressive strength of the geopolymer material based on the following formula:

where,

fc - compressive strength [MPa],

F - maximum load [N],

Ac - area of the cross-section of the specimen, which is subjected to the compressive force [mm2].

The results should be reported to the nearest 0.1 MPa.

b) Bending strength

The bending strength, was carried out in accordance with EN 12390-5:2019-08. The test specimens were rectangular in shape, on which a uniform load was applied. The test was performed until the specimen broke. The test was carried out at a constant increasing rate, which according to the standards is approximately 0.04 - 0.06 MPa/s. As with the compressive strength test, the flexural strength can be calculated from the recorded data using the formula:

where:

fcf - bending strength [MPa],

F - maximum load [N],

l - support roll spacing [mm],

d1, d2 - transverse dimensions of the specimen [mm].

The results should be rounded to the nearest 0.1 MPa.

The test was carried out using the same machine (Matest 3000kN) as for the measurement of the mechanical properties in compression, but here a measuring head designed for three-point bending of the specimens was used. The specimens had dimensions of 200x50x50mm.

c) Examination of sample surface morphology - SEM (microstructure)

SEM observations were carried out on a JSM-IT200 to check the morphology, chemical composition (EDS) and correctness of the process. The test began by placing the samples into a vacuum sputtering machine (DII-29030SCTR Smart Coater) , whose purpose was to coat the sample with a thin layer of gold to increase the its conductivity. The size of the samples was approximately 4mm

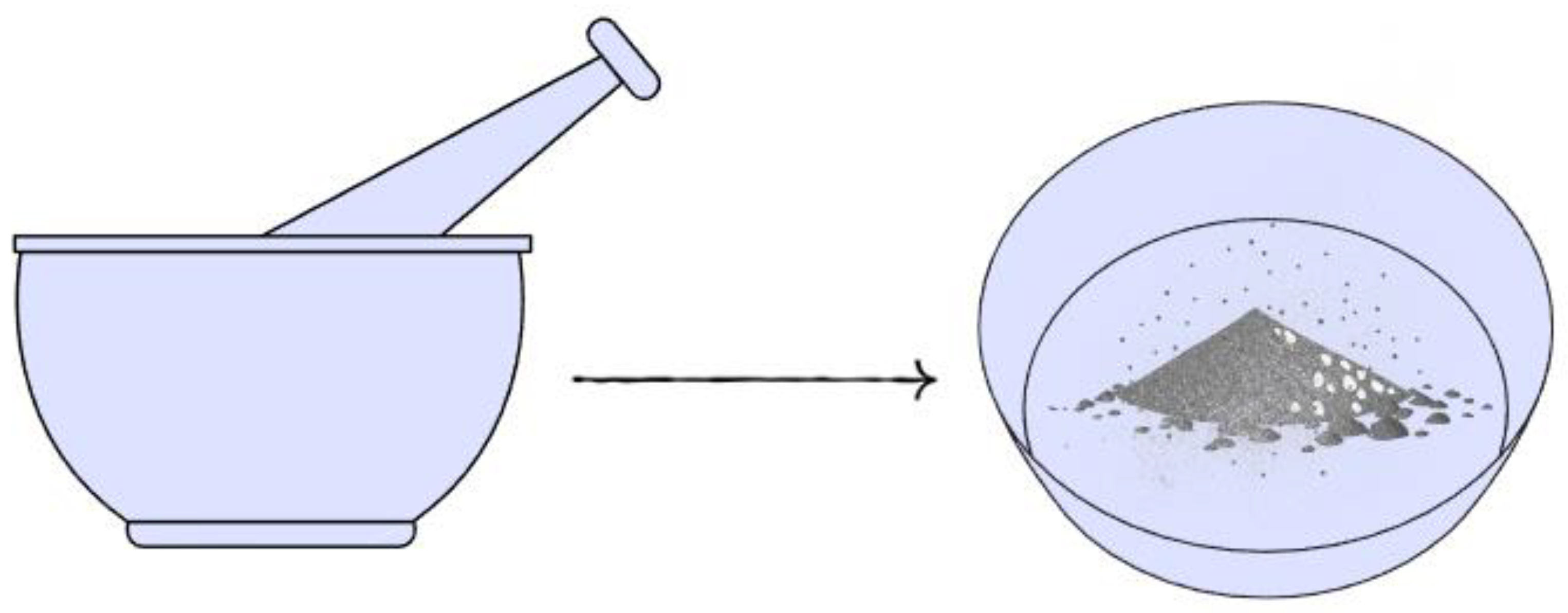

d) x-ray diffraction measurement

To prepare the material for the measurements, the collected sample had to be finely ground in a mortar to a clear powder and then poured into a suitable holder. A PANalytical AERIS was used for the measurements.

Figure 2.3.

Sample preparation for XRD testing.

Figure 2.3.

Sample preparation for XRD testing.

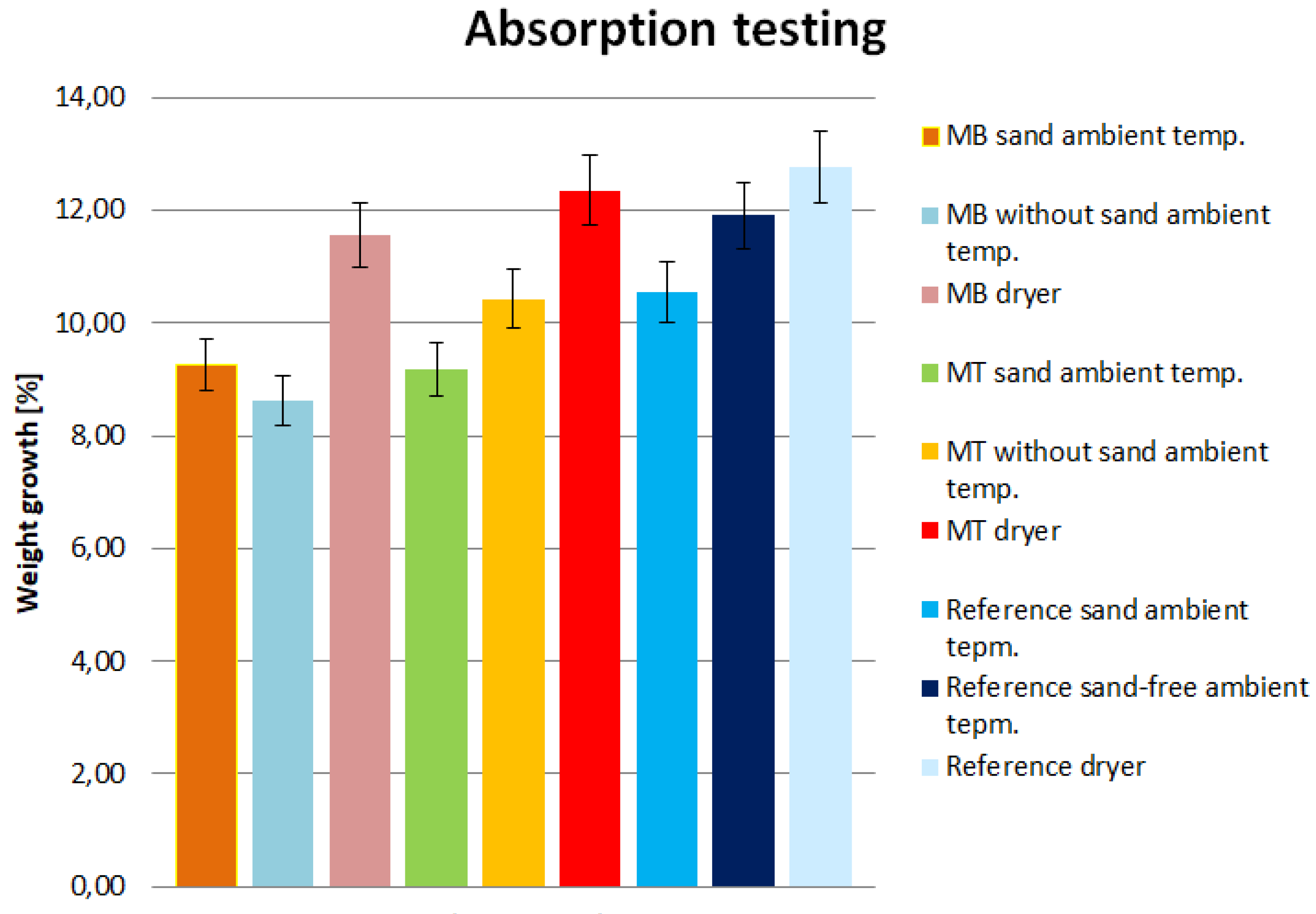

d) Absorbability

The absorbability test consisted of examining the water absorption capacity of the material under test. The test was carried out on the basis of the PN-88/B-06250 standard. In the first stage of the test, samples of regular shape had to be prepared, three of each type. Each sample was then weighed and placed in a suitable container, which was then flooded with distilled water. Over the next 14 days, the samples were taken out and weighed. From the results, the increase in weight of the test material could be calculated using the following formula:

where,

nw - absorbability [%].

G1 - average mass of dry specimens

G2 - average mass of samples saturated with water

Figure 2.4.

Schematic of an immersed sample.

Figure 2.4.

Schematic of an immersed sample.

3. Discussion

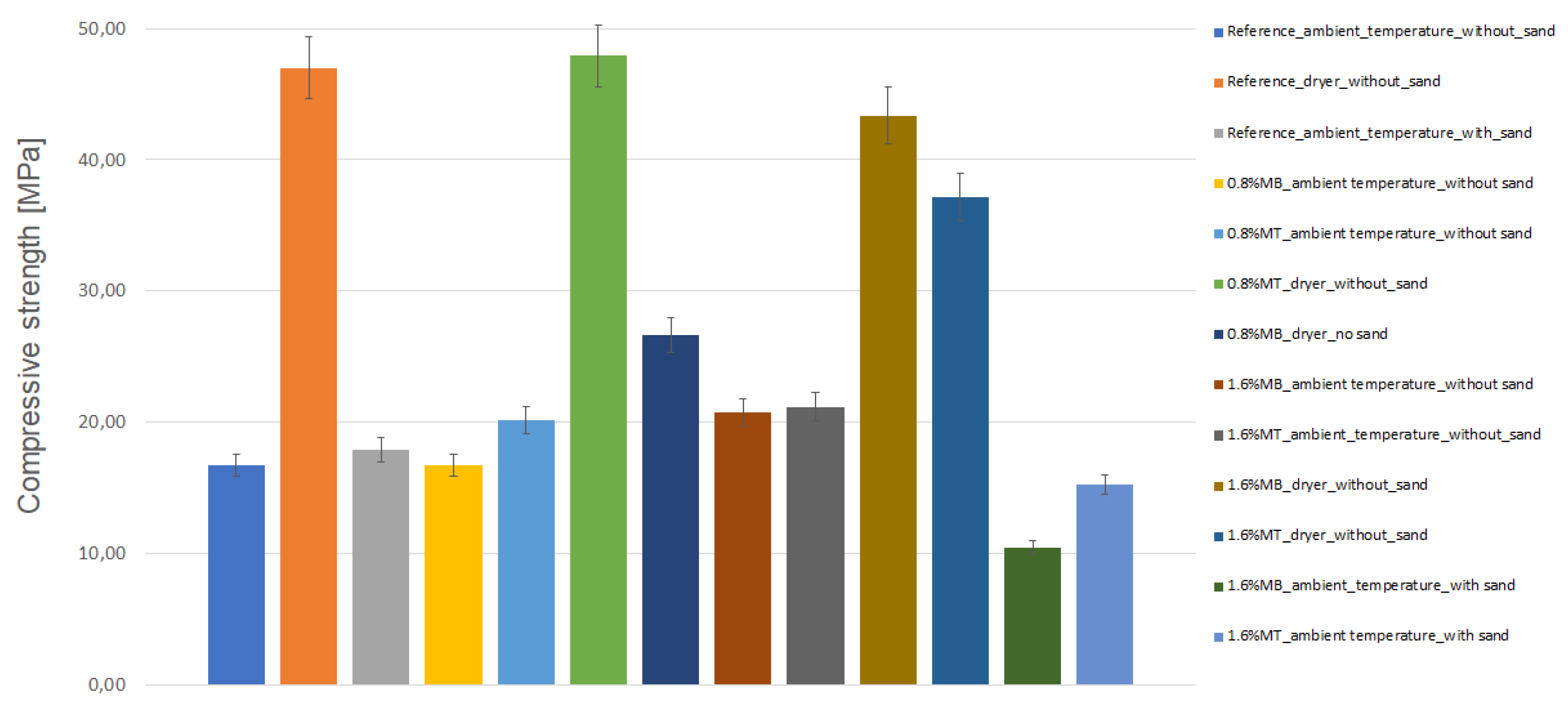

a) Analysis of mechanical-compressive properties

Figure 3.1.

Compressive strength analysis diagram of geopolymer samples.

Figure 3.1.

Compressive strength analysis diagram of geopolymer samples.

Based on the results obtained (Figure 3.1), it was found that the samples that were air-cured had higher repeatability of results compared to the oven-cured samples. Compared to the reference sample, the geopolymers cured at ambient temperature with the addition of biocomponents in the form of beet molasses and cane molasses had an increased compressive strength. An increase in strength of 20.7% was obtained when 0.8% cane molasses was added. An increase in molasses addition of 1.6% also resulted in an increase in compressive strength of a further 6.1% to 26.8%. A different effect was observed when the beet molasses additive was introduced into the geopolymer. The geopolymer samples with 0.8% molasses addition had identical strength to the reference sample without molasses addition. However, by adding 1.6% beet molasses, an increase of 24.1% over the reference samples was observed. It was also found that the addition of beet molasses and cane molasses did not work well for curing geopolymers at elevated temperatures. When curing at elevated temperatures, an increase in strength was observed for the samples with the 0.8% MT additive, but only by 2%. The other samples with bio-additives cured at elevated temperatures showed reduced strength compared to the reference sample.

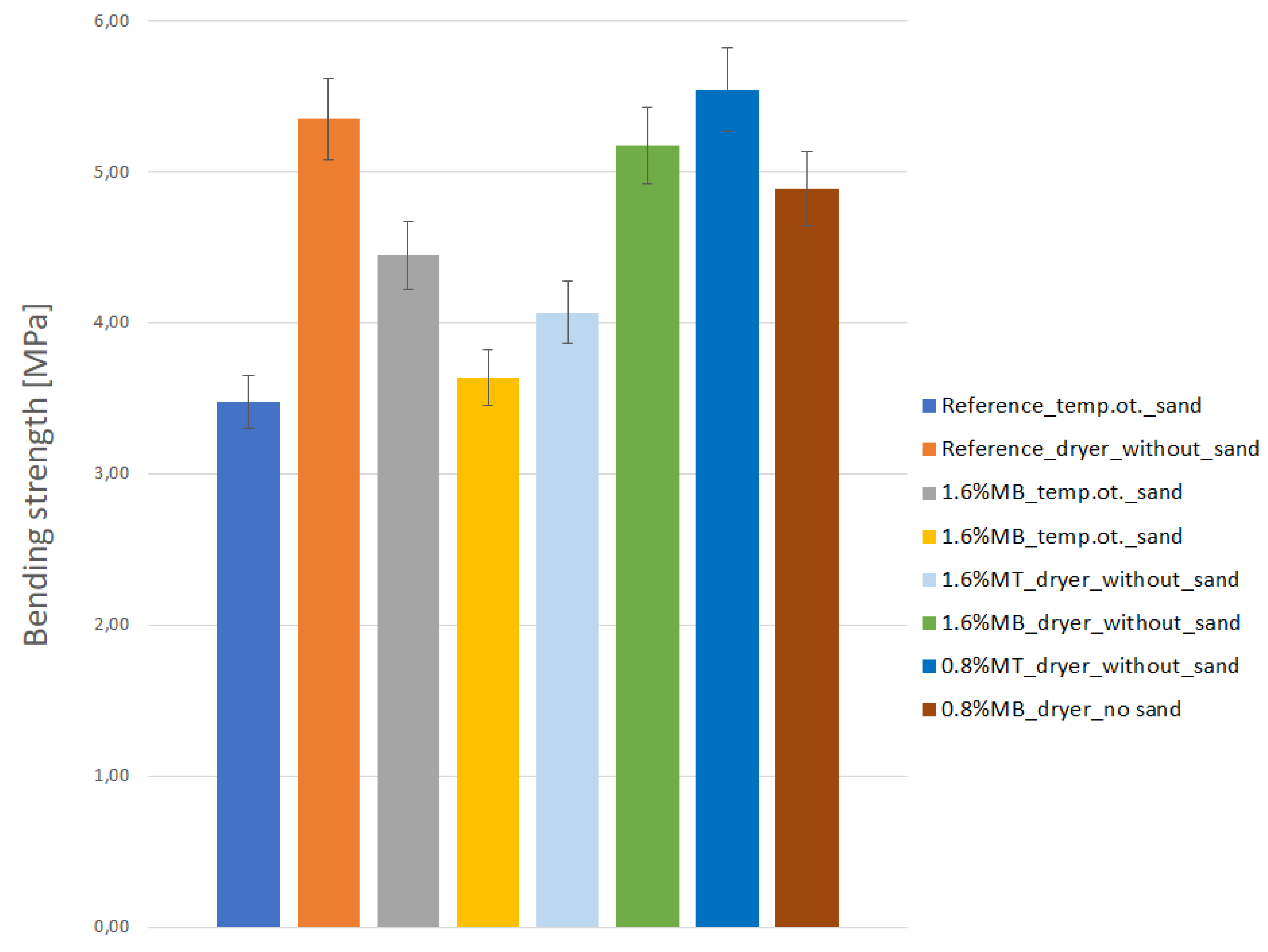

b) Analysis of mechanical properties - bending

In the diagram below (Figure 7.2.1), it can be seen the analysis of the bending strength bending.

The aim of the study was to improve the mechanical properties of the air-cured samples. Unfortunately, the samples, cracked within 30 days and the decision was taken to modify them. Sand was added to the basic composition (the ratio of sand to FA was 1:1). This was just to see if the samples would continue to crack at the surface. The samples did not crack and measurements could be taken on them. It can be seen that the addition of cane molasses in the samples cured at ambient temperature increased the strength by 3%, compared to the reference sample.

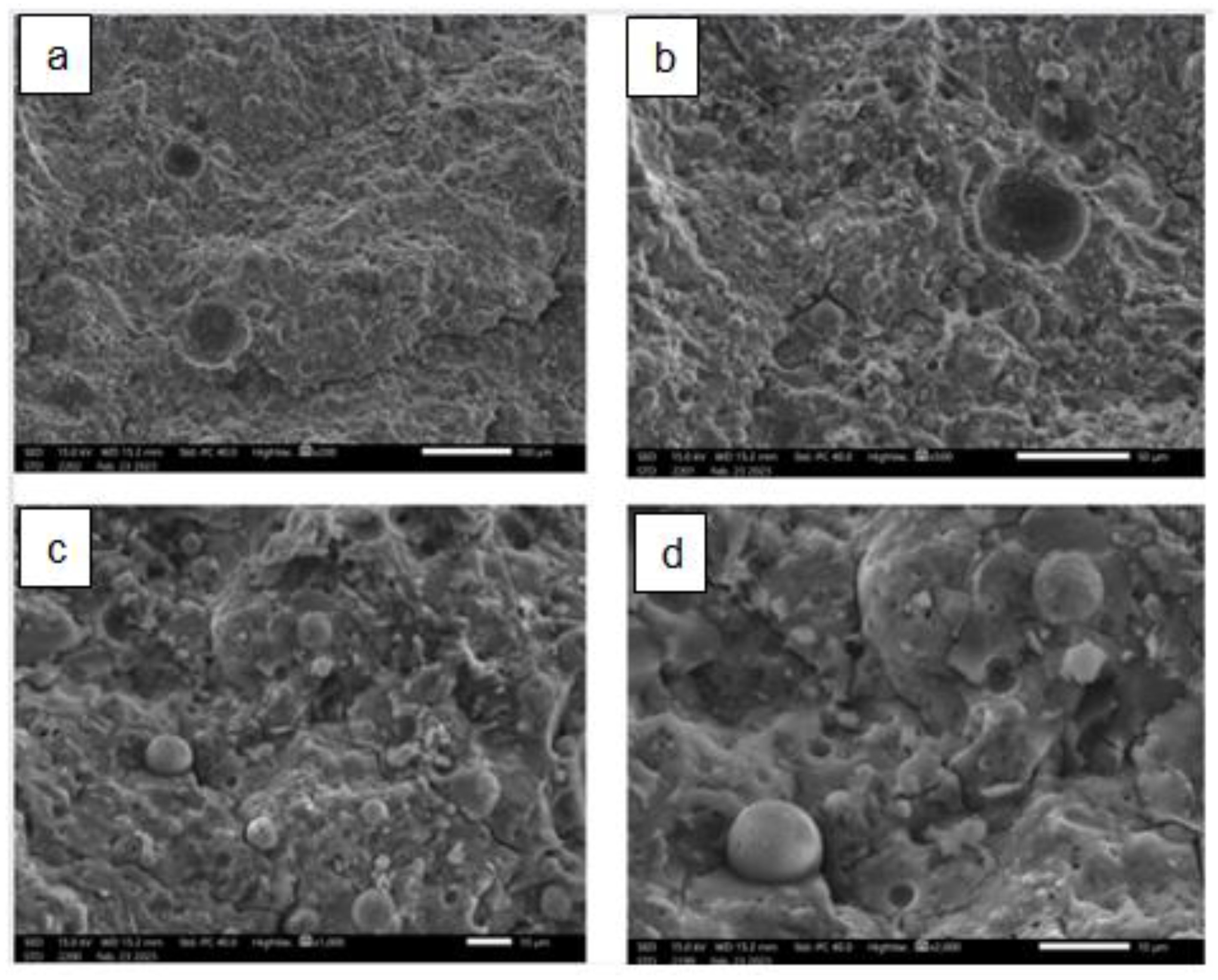

c) Analysis of sample surface morphology - SEM (microstructure)

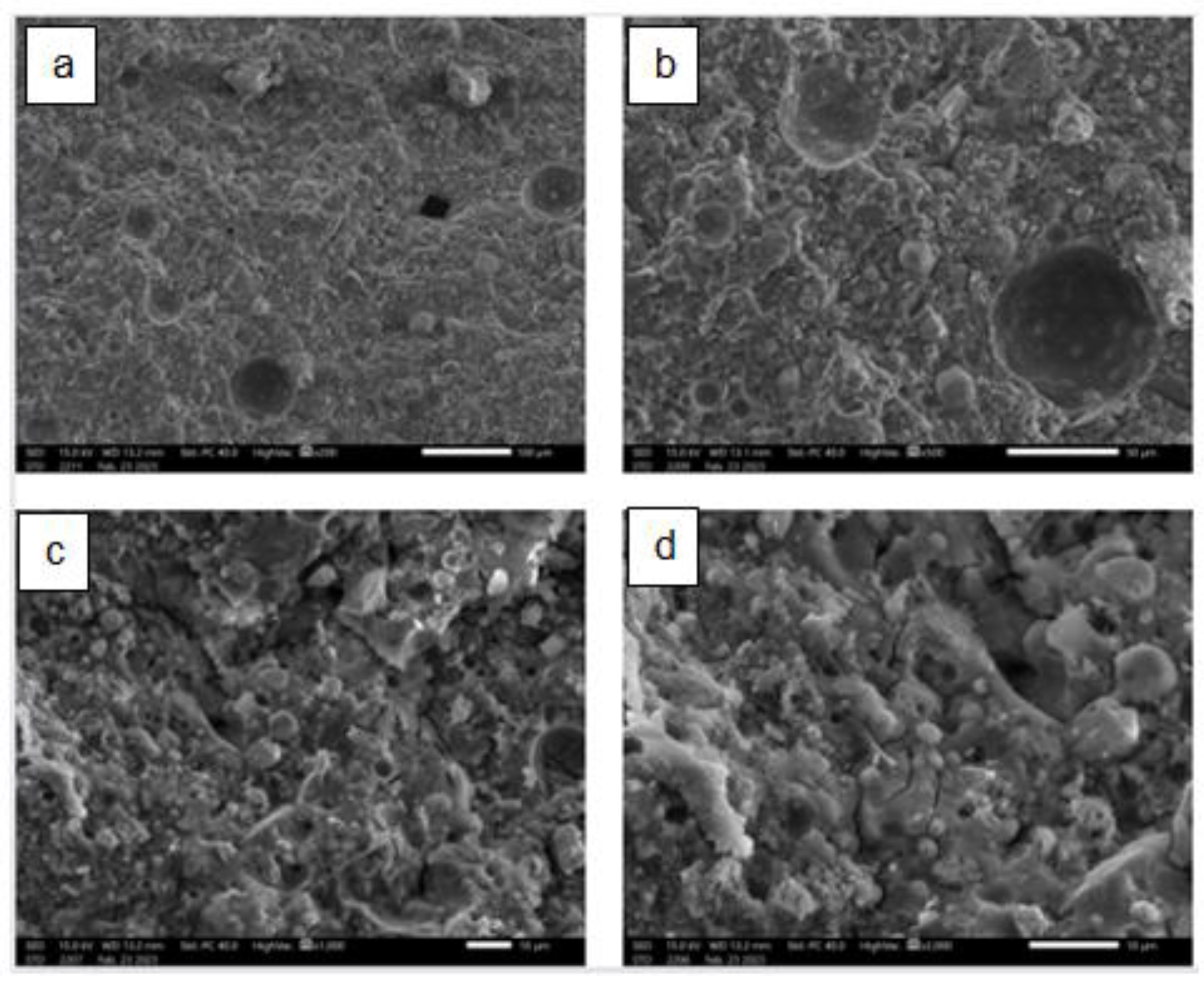

The following microphotographs show the surface structures of the materials tested.

Figure 3.2.

Flexural strength analysis diagram of geopolymer specimens.

Figure 3.2.

Flexural strength analysis diagram of geopolymer specimens.

Figure 3.3.

Microphotograph of a reference sample cured at ambient temperature - magnification: a) x500; b) x 1000; c) x 2000; d) x 3000.

Figure 3.3.

Microphotograph of a reference sample cured at ambient temperature - magnification: a) x500; b) x 1000; c) x 2000; d) x 3000.

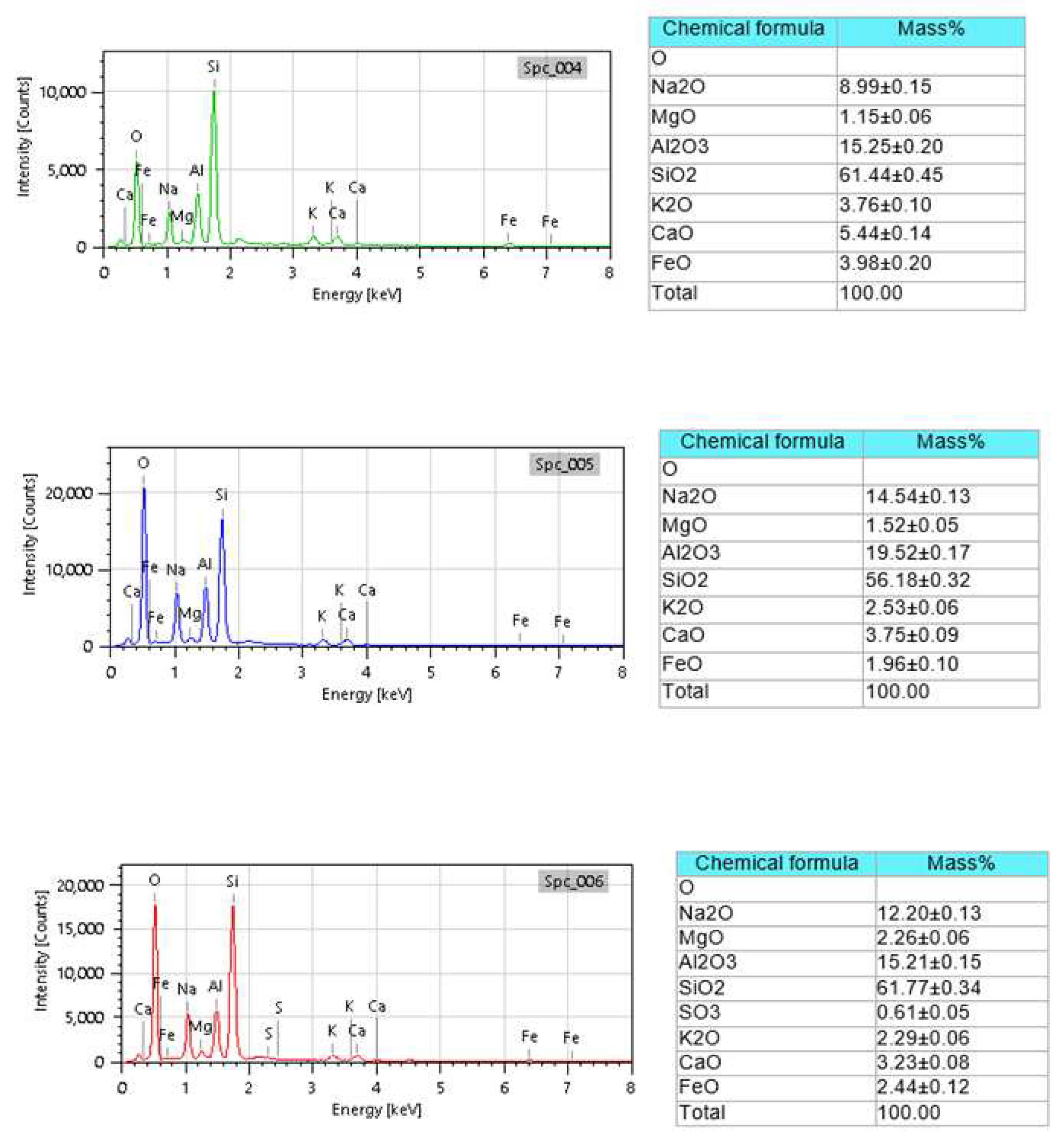

Figure 3.4.

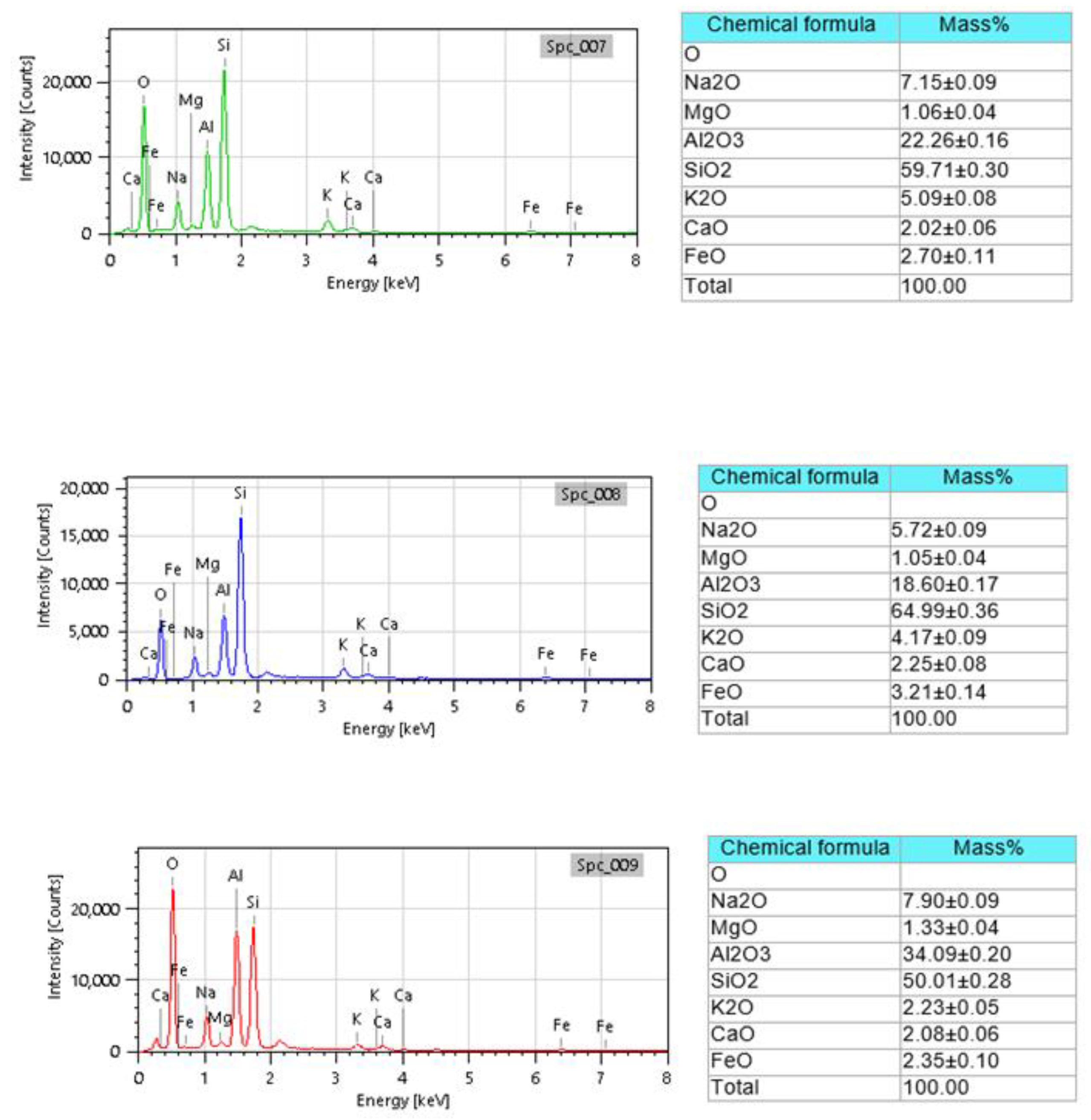

EDS plot and percentage composition of components present in the reference sample cured at ambient temperature.

Figure 3.4.

EDS plot and percentage composition of components present in the reference sample cured at ambient temperature.

Analysing the above results from Figure 3.3, it can be seen that the test sample has a higher amount of silicon in its composition than in the sample in Figure 3.4. In addition, oxygen, iron, aluminium, potassium and calcium can be found in its composition. The microstructure shows pore sizes of approximately 10 µm, the structure is compact and there are no undissolved ash particles.

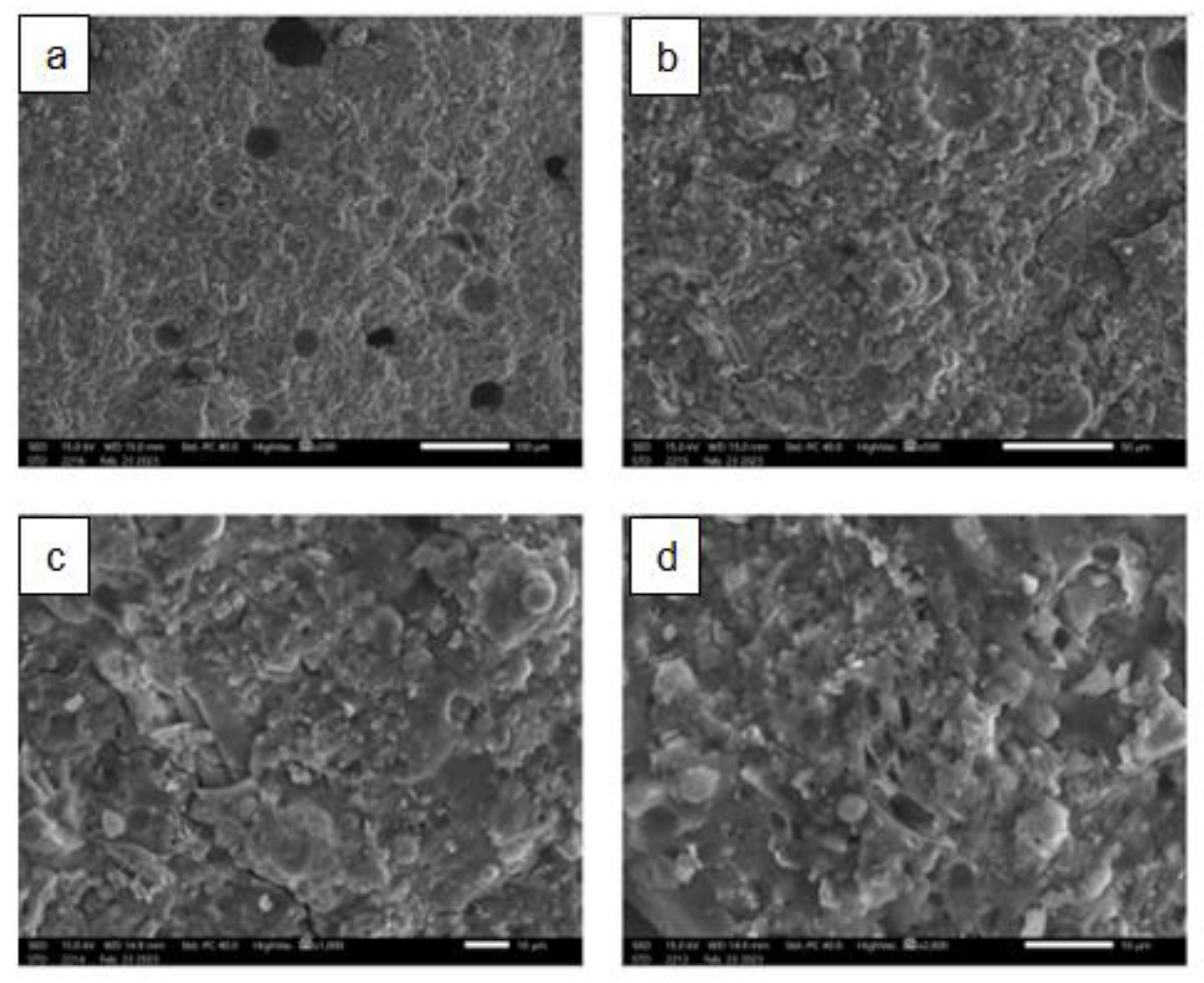

The following figures summarise the results of the analysis of the surface morphology and the percentage composition of the constituents of the components of the tested MT and MB modified geopolymers.

Figure 3.5.

Microphotograph of a modified MT sample cured at ambient temperature - magnification : a) x500; b) x 1000; c) x 2000; d) x 3000.

Figure 3.5.

Microphotograph of a modified MT sample cured at ambient temperature - magnification : a) x500; b) x 1000; c) x 2000; d) x 3000.

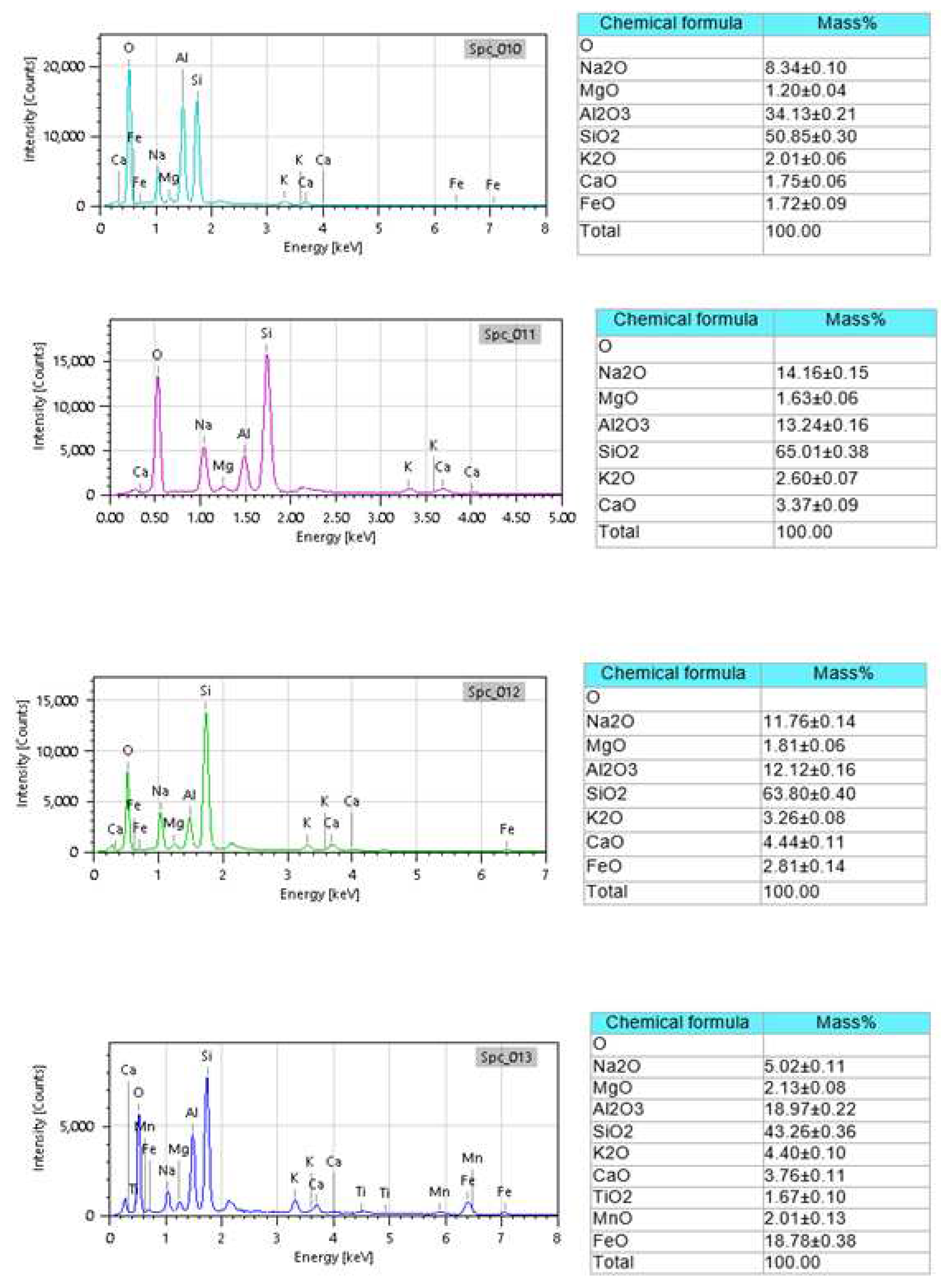

Figure 3.6.

EDS plot and percentage composition of components present in the sample with MT added.

Figure 3.6.

EDS plot and percentage composition of components present in the sample with MT added.

The microstructure in Figure 3.5 shows the surface of sample MT1.6 cured at ambient temperature. From the figure, it can be seen that the structure of the sample is homogeneous with a small number of pores and the absence of undissolved ash, while the EDS analysis shows a chemical composition in which the amount of silicon is predominant compared to the rest of the samples. In addition, the elements oxygen, calcium, sodium, iron, aluminium, and potassium can be distinguished from the qualitative analysis.

Figure 3.7.

Microphotograph of a modified MB sample cured at ambient temperature - magnification : a) x500; b) x 1000; c) x 2000; d) x 3000.

Figure 3.7.

Microphotograph of a modified MB sample cured at ambient temperature - magnification : a) x500; b) x 1000; c) x 2000; d) x 3000.

Figure 3.8.

Graph and percentage composition of the constituents present in the sample with the addition of MB.

Figure 3.8.

Graph and percentage composition of the constituents present in the sample with the addition of MB.

Figure 3.8 shows a qualitative EDS analysis of sample MB1.6 cured at ambient temperature. From the analysis, it can be seen that the composition does not differ too much from the other samples, as the elements calcium, oxygen, silicon, aluminium, iron and magnesium can also be distinguished in their composition. From Figure 3.7 showing the microstructure, it can be seen that the structure is compact with a small number of pores and undissolved FA particles.

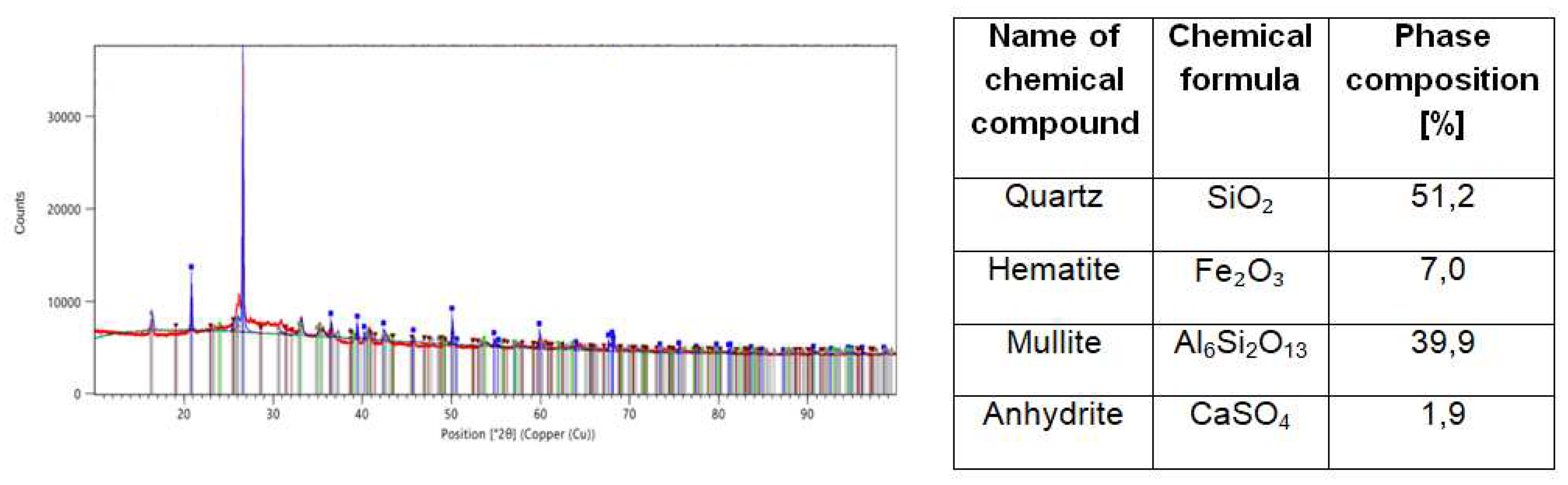

d) Phase composition analysis (XRD)

In order to identify the composition of geopolymer materials that were FA-based and modified with biosolids, an analysis was carried out using an X-ray diffractometer. HighScore Plus software, which has a materials database, was used to analyse the results. It enabled the identification of individual peaks in the diffractogram. In the figures below 7.4.1 - 7.4.3 show the phase composition analysis of the samples examined.

Figure 3.9.

Analysis of the phase composition of the reference sample.

Figure 3.9.

Analysis of the phase composition of the reference sample.

Figure 3.9 shows the diffractogram obtained, having the symbols of the identified phases. From the table, the chemical composition of the test material can be read. When analysing the reference sample, which included FA, it is possible to read that it is characterised by a high content of quartz and mullite. In addition, phases such as iron (III) oxide and calcium (VI) sulphate were recognised.

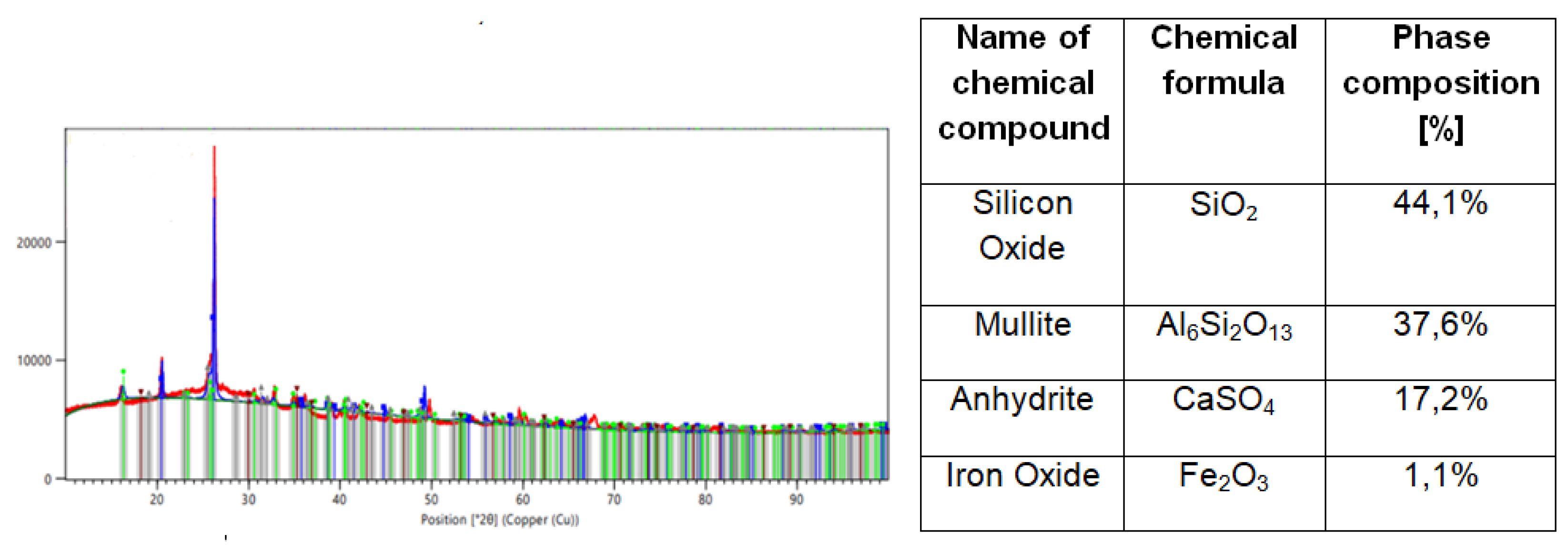

Figure 3.10.

Phase composition analysis of sample with1.6%MT (without sand, air curing).

Figure 3.10.

Phase composition analysis of sample with1.6%MT (without sand, air curing).

By analysing the diffractogram data of the MT-modified geopolymer cured at ambient temperature, a predominant amount of silicon (IV) oxide and mullite can be observed. In addition to these two phases, calcium (VI) sulphate and iron (III) oxide can be distinguished.

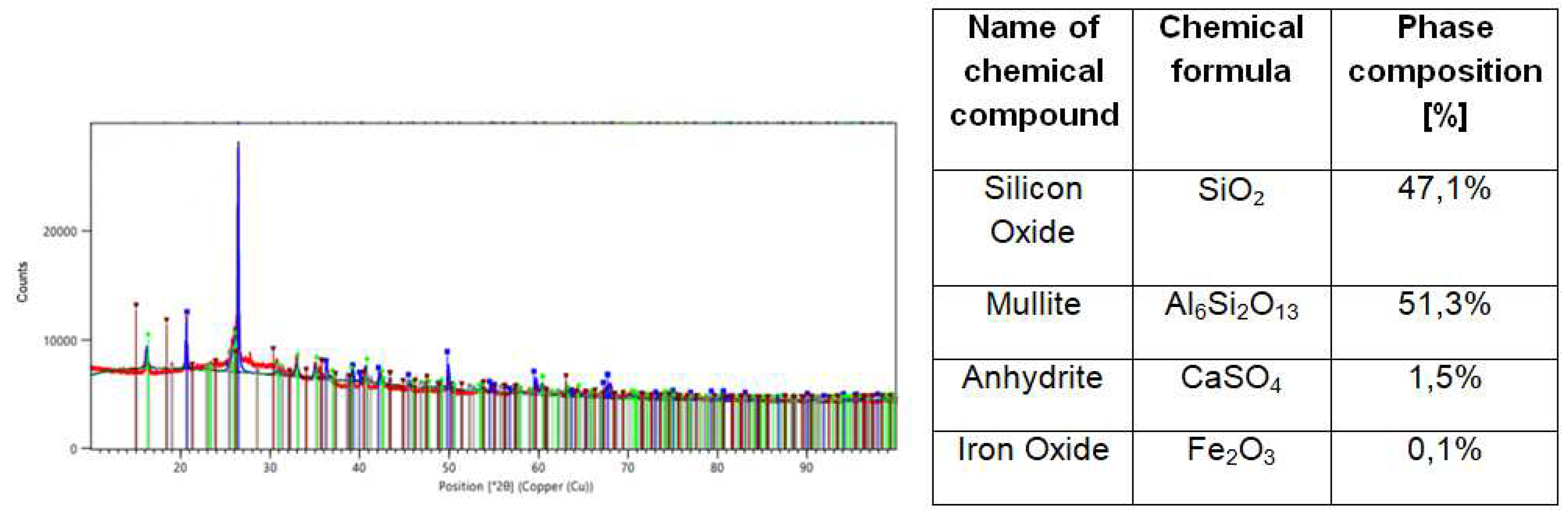

Figure 3.11.

Phase composition analysis with the addition of 1.6%MB (without sand, air curing).

Figure 3.11.

Phase composition analysis with the addition of 1.6%MB (without sand, air curing).

The diffractogram shown in Figure 3.11 characterises an MB-modified geopolymer material that has been cured at ambient temperature. By means of XRD analysis, the chemical patterns of the phases present in the studied material were determined. The characteristic peaks were ordered to the phases, i.e. silicon (IV) oxide, mullite, anhydrite and iron (III) oxide.

Figure 3.12.

Analysis of the soak test after 14 days.

Figure 3.12.

Analysis of the soak test after 14 days.

Analysing the above results, high sorption properties were noted among the samples that were dryer-cured. The weight increase of these samples ranged between 11.40 and 13.3%, while for samples cured at ambient temperature the weight increase was between 8.70% and 11.7%. The samples cured at ambient temperature had little measurement scatter which can be considered a success. The lower absorbability may have been due to the amount of water in the initial samples before immersion. In addition, the addition of molasses influenced the lower amount of water absorbed.

4. Conclusions

1. The results from the mechanical properties measurements clearly confirmed the stated aim of creating a geopolymer modified with bio-additives that had higher compressive strengths relative to the reference sample. The addition of cane molasses increased the strength by almost 27% and beet molasses by 24%. Thus, it can be inferred that the addition of plant-derived bioadditives in the samples cured at ambient temperature had a significant effect on the mechanical properties. This may be due to:

(a) The strengthening of the geopolymer structure that results from interactions between the components, with molasses acting as a filler causing an increase in hardness,

(b) Increased cross-reactions resulting from the presence of sugar particles that are a component of molasses,

c) Filling of free pore spaces by molasses as well as a change in the mechanism of bond formation in the geopolymer.

2. The addition of molasses had no significant effect on the morphology or chemical composition of the materials studied.

3. Modification with bio-additives affected the rate of curing. This was found by observation, in which it was noted that the samples with MT and MB additives cured faster on the material surface than the reference samples.

4. From the saturation analysis, it can be seen that the samples cured at ambient temperature had lower saturation compared to those cured in the dryer. The addition of molasses resulted in less water sorption due to fewer voids in the sample morphology. This is related to the amount of water in the initial samples before immersion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ł. and J.Sz.; methodology, M.Ł; validation, J.Sz; M.Ł and K.P; formal analysis, J.Sz and K.P.; investigation, K.P and J.Sz. resources, J.Sz.; data curation, J.Sz and K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Sz; writing—review and editing, J.Sz.; visualization, J.Sz; supervision, M.Ł; project administration, M.Ł.; funding acquisition, M.Ł.

Funding

This work has been financed by the National Centre for Research and has been financed by the National Centre for Research and Development in Poland under the grant: Development of technology for additive production of environmentally friendly and safe insulation materials and able to accumulate heat based on the alkaline activation of anthropogenic raw materials (LIDER/16/0061/L-11/19/NCBR/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Walkley, B. “Geopolymers,” Encycl. Earth Sci. Ser., vol. 37, pp. 1633–1656, 2020,. [CrossRef]

- Hardjito, D.; Wallah, S.E.; Sumajouw, D.M.J.; Rangan, B.V. , “On the Development of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete,” no. March, 2019.

- Al Bakri, A.M.M.; Kamarudin, H.; Bnhussain, M.; Nizar, I.K.; Mastura, W.I.W. Mechanism and Chemical Reaction of Fly Ash Geopolymer Cement- A Review. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, K.; Hameed, R.; Ahmad, H.A.; Razzaq, A.; Ahmad, M.; Mahmood, A. Analytical framework for value added utilization of glass waste in concrete: Mechanical and environmental performance. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talakokula, V.; Vaibhav; Bhalla, S. Non-destructive Strength Evaluation of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete Using Piezo Sensors. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.J.; Alengaram, U.J.; Santhanam, M.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Mo, K.H. Microstructural investigations of palm oil fuel ash and fly ash based binders in lightweight aggregate foamed geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Provis, J.L.; van Deventer, J.S.J.; Krivenko, P.V. Characterization of Aged Slag Concretes. ACI Mater. J. 2008, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.-H.; Song, J.-K.; Ashour, A.F.; Lee, E.-T. Properties of cementless mortars activated by sodium silicate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J.; Liu, X. Sustainable resource opportunity for cane molasses: use of cane molasses as a grinding aid in the production of Portland cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 93, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, A.; Sudalaimani, K.; Vijayakumar, C.; Saravanakumar, S. Effect of bio-additives on physico-chemical properties of fly ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag based self cured geopolymer mortars. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 361, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, A.L.; Tayeh, B.A.; Adesina, A.; Isleem, H.F.; Zeyad, A.M. Potential applications of geopolymer concrete in construction: A review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, N.; Sahu, V.; Misra, A.K. Development of geopolymer cement concrete for highway infrastructure applications. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 18, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, A.; Sudalaimani, K.; Vijayakumar, C.; Saravanakumar, S. Effect of bio-additives on physico-chemical properties of fly ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag based self cured geopolymer mortars. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 361, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Tariq, S.; Shaukat, W. Attribution of molasses dosage on fresh and hardened performance of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić, L.Ć.; et al. Sugar Beet Molasses : Properties and Applications in. Food Feed Res. 2016, 43, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmonari, A.; Cavallini, D.; Sniffen, C.; Fernandes, L.; Holder, P.; Fagioli, L.; Fusaro, I.; Biagi, G.; Formigoni, A.; Mammi, L. Short communication: Characterization of molasses chemical composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 6244–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.; Radloff, W. Effect of Molasses Supplementation on the Production of Lactating Dairy Cows Fed Diets Based on Alfalfa and Corn Silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 2997–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolussi, G.; O’Neill, C.J. Variation in molasses composition from eastern Australian sugar mills. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2006, 46, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. M. S. Kim, S. C. B. G. M. S. Kim, S. C. B. Lee, and S. C. S. Lee, “Improvement of the Quality of Ojeoksan ( Herbal Medicine ) Meal Silage by Molasses Supplementation 당밀의 첨가가 오적산박 사일리지의 품질 및 기호성에 미치는 영향,” vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 77–84, 2007.

- Jain, R.; Venkatasubramanian, P. Sugarcane Molasses – A Potential Dietary Supplement in the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia. J. Diet. Suppl. 2017, 14, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M.; Gharieb, M. Valorization of sugar beet waste as an additive for fly ash geopolymer cement cured at room temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.R. Incremental effect of saccharum officinarum addition on strength characteristics of geopolymer composite specimens. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 561, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasson, B.J.; Rocha, J.C. Drying shrinkage behavior of geopolymer mortar based on kaolinitic coal gangue. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasson, B.J.; Rocha, J.C. Reaction mechanism and mechanical properties of geopolymer based on kaolinitic coal tailings. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanda, N.; Mfoutou, N.N.; Madila, E.E.N.; Louzolo-Kimbembe, P. Microstructure of Fine Clay Soils Stabilized with Sugarcane Molasses. Open J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 12, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumadurdiyev, A.; Ozkul, M.H.; Saglam, A.R.; Parlak, N. The utilization of beet molasses as a retarding and water-reducing admixture for concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.K.; Nadir, Y.; Girija, K. Effect of source materials, additives on the mechanical properties and durability of fly ash and fly ash-slag geopolymer mortar: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, A.; Sudalaimani, K.; Kumar, C.V. Investigation on mechanical properties of fly ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag based self curing bio-geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 149, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A.; Criado, M. Microstructure development of alkali-activated fly ash cement: a descriptive model. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. In Situ ATR-FTIR Study of the Early Stages Geopolymer Gel Formation. Langmuir 2007, 23, 9076–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. B.Singh; S.K.Saxena; Kumar, M. Effect of nanomaterials on the properties of geopolymer mortars and concrete. Mater. Today: Proc. 2018, 5, 9035–9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevik, A.; Alzeebaree, R.; Humur, G.; Niş, A.; Gülşan, M.E. Effect of nano-silica on the chemical durability and mechanical performance of fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 12253–12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Sem, “What is Scanning Electron Microscopy ( SEM ) Fundamental Principles of Scanning Electron Microscopy ( SEM ) Scanning Electron Microscopy ( SEM ) Instrumentation - How Does It Work ?,” 2016.

- Aisyah, N.; Rifai, H.; De La Maisonneuve, C.B.; Oalmann, J.; Forni, F.; Eisele, S.; Phua, M.; Putra, R. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging and analysis of magnetic minerals of lake Diatas peatland section DD REP B 693. J. Physics: Conf. Ser. 2020, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasson, B.J.; Rocha, J.C. Drying shrinkage behavior of geopolymer mortar based on kaolinitic coal gangue. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).