Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Solar cells and photodetectors

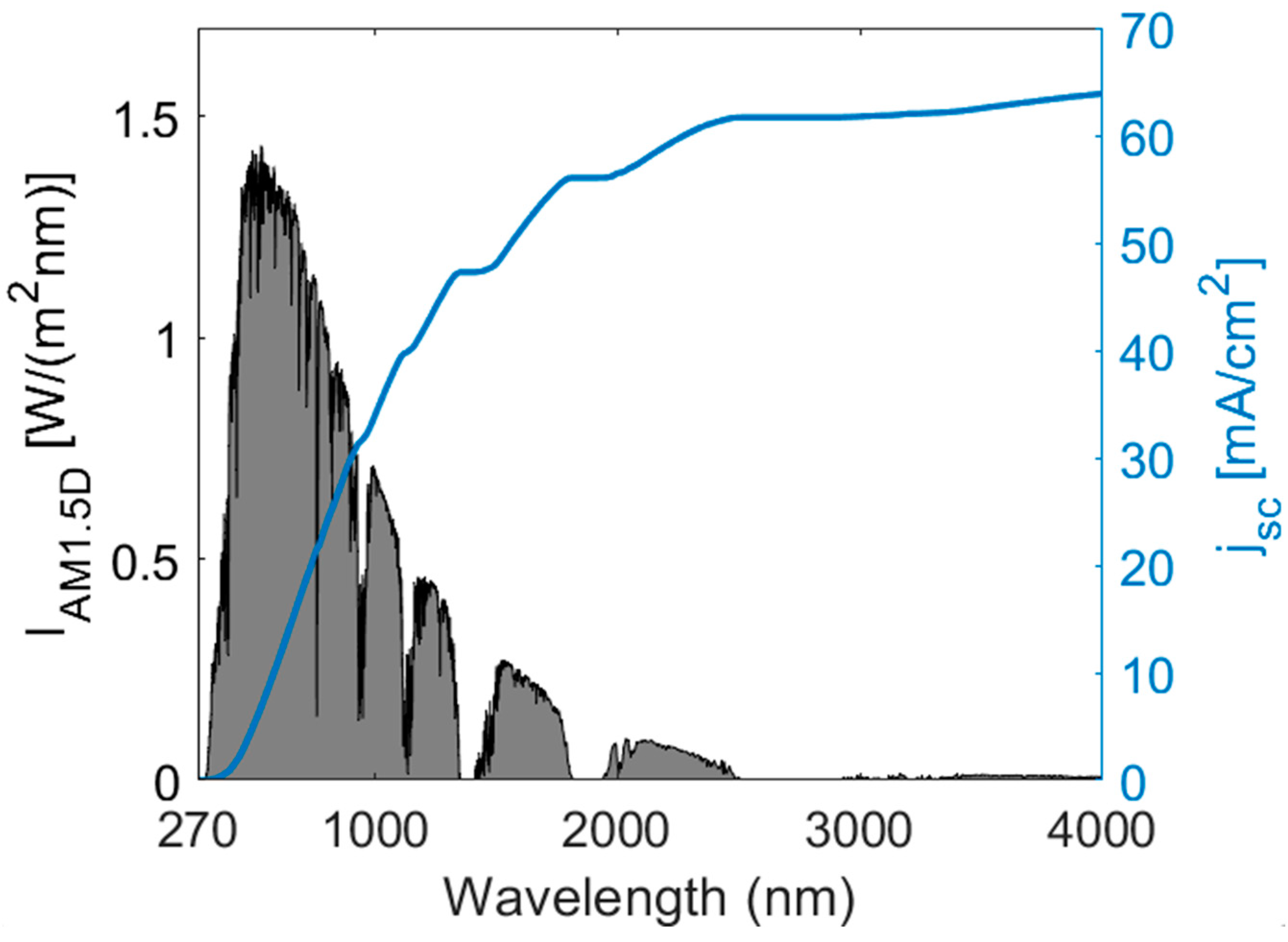

2.1. Bandgap of semiconductors for absorption applications

2.2. Absorption of light for solar cells and photodetectors

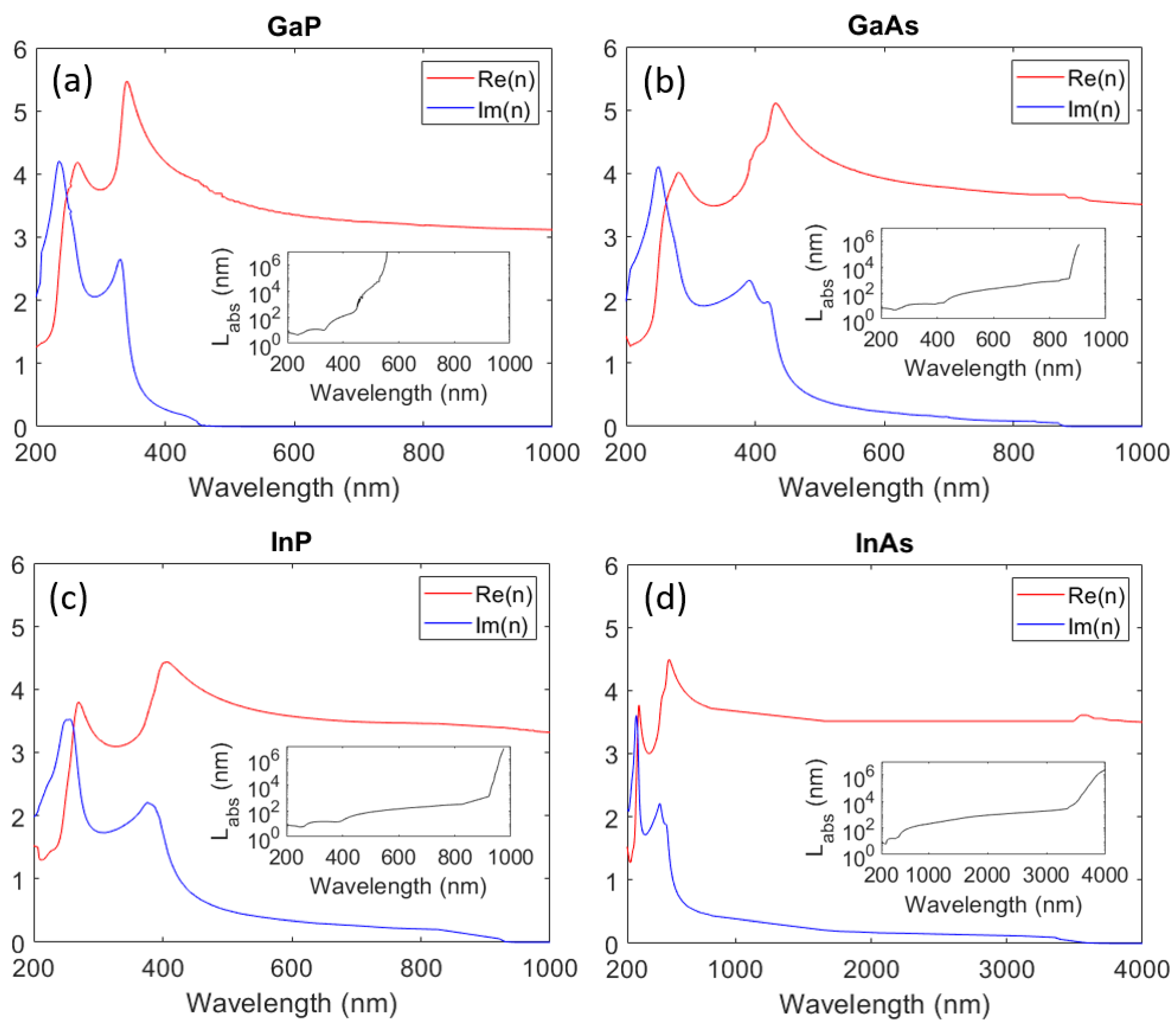

3. Bandgap and refractive index of III-Vs

3.1. Bandgap

| III-V | Bandgap (eV) | Bandgap wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| GaP | 2.271 | 546 |

| GaAs | 1.42 | 873 |

| InP | 1.34 | 925 |

| InAs | 0.35 | 3540 |

3.1. Refractive index

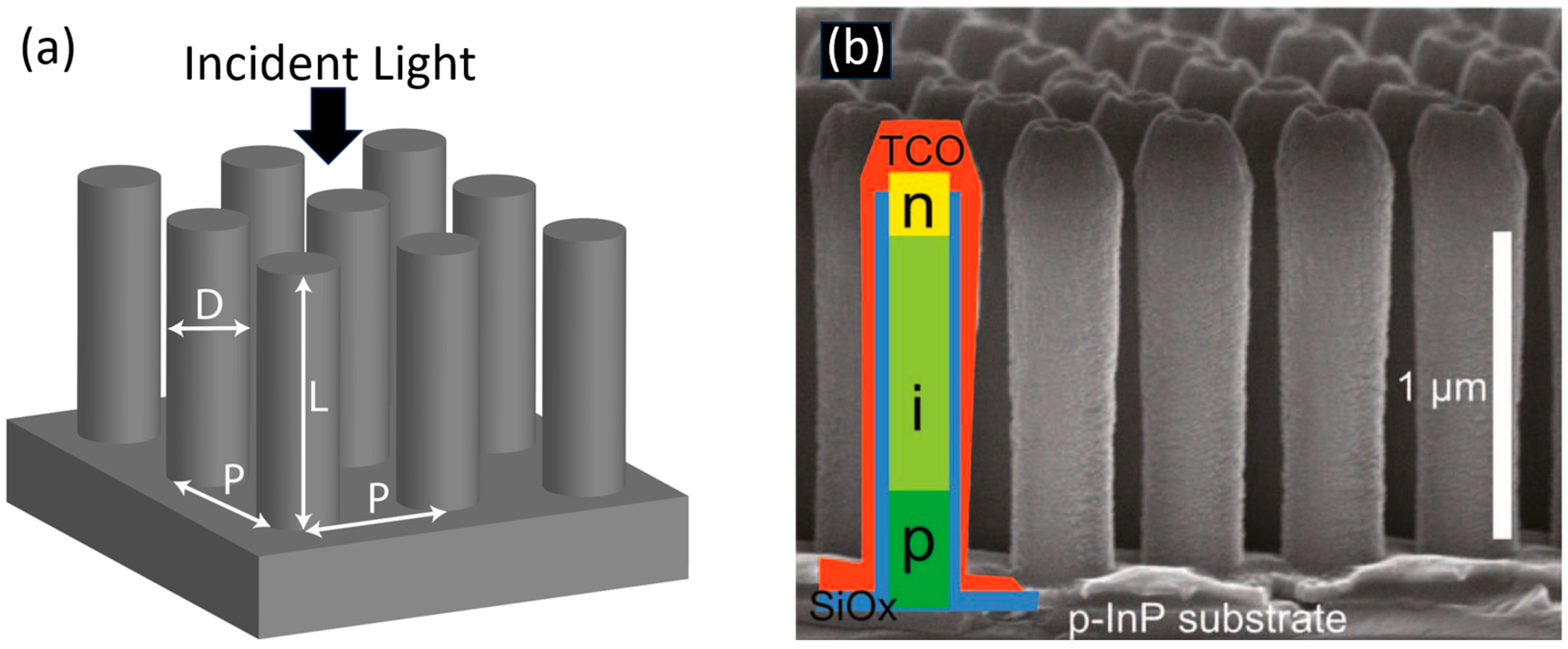

4. III-V nanowires

5. Tuning of absorption in vertical III-V nanowires

5.1. Basic nanowire array

5.1.1. Insertion reflection loss

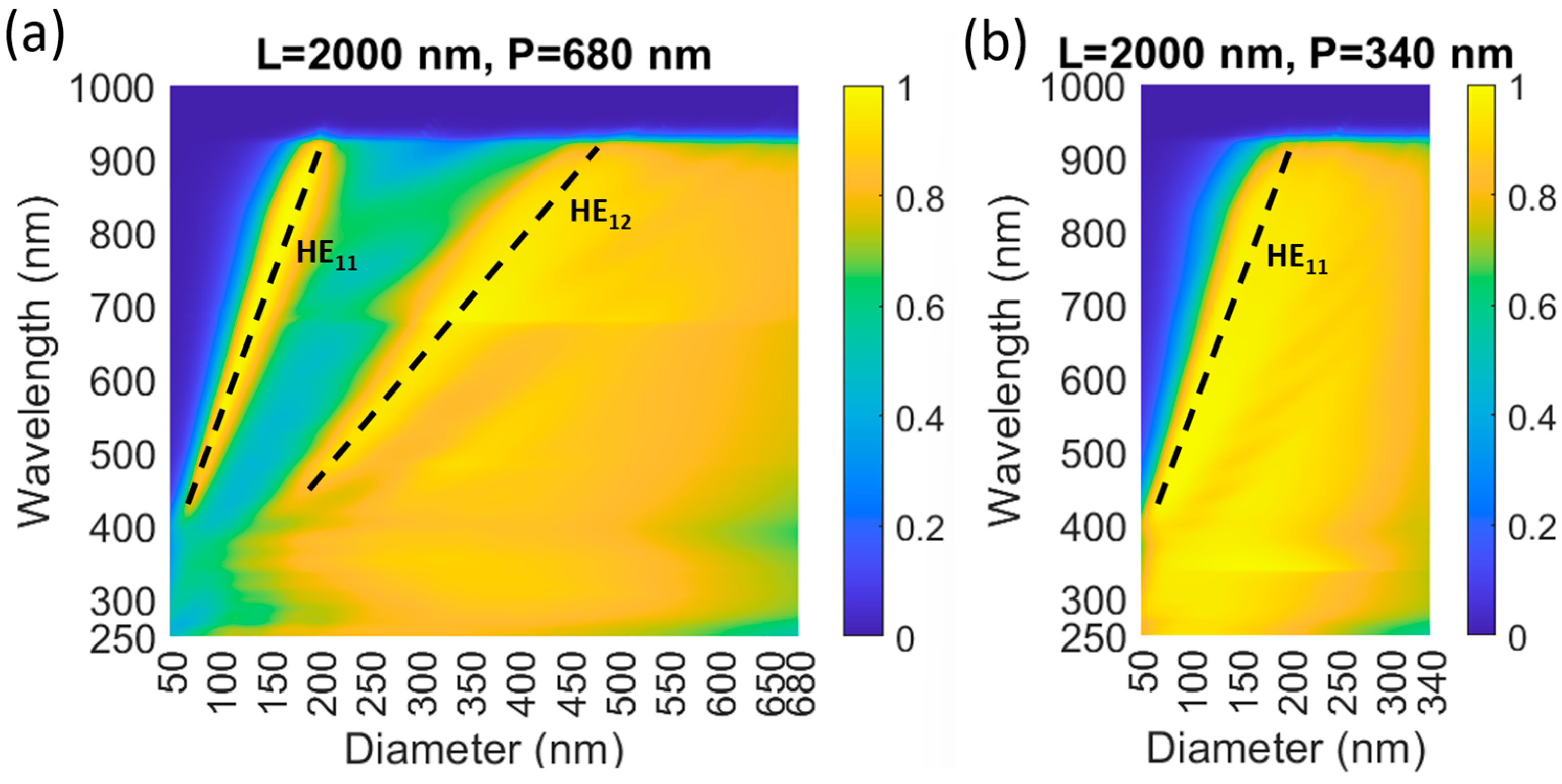

5.1.2. Diameter dependent absorption

5.1.4. Photonic-crystal modes in nanowire arrays

5.1.4. Absorption in single nanowire vs nanowire array

5.1.3. Dependence on the incidence angle

5.2. Tapered nanowires

5.3. Aperiodic arrays

5.4. Tandem nanowire-on-silicon solar cells

5.5. Effect of imperfections in nanowire arrays

5.6. Bragg reflectors in nanowires

5.7 Examples of realized III-V nanowires solar cells and photodetectors

6. Future directions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vurgaftman, I.; Meyer, J.R.; Ram-Mohan, L.R. Band Parameters for III–V Compound Semiconductors and Their Alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 89, 5815–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N.; Xu, H.Q. Efficient Light Management in Vertical Nanowire Arrays for Photovoltaics. Opt. Express 2013, 21, A558–A575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Tan, H.H.; Jagadish, C.; Fu, L. III–V Semiconductor Single Nanowire Solar Cells: A Review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2018, 3, 1800005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VJ, L.; Oh, J.; Nayak, A.P.; Katzenmeyer, A.M.; Gilchrist, K.H.; Grego, S.; Kobayashi, N.P.; Wang, S.-Y.; Talin, A.A.; Dhar, N.K.; et al. A Perspective on Nanowire Photodetectors: Current Status, Future Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2011, 17, 1002–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otnes, G.; Borgström, M.T. Towards High Efficiency Nanowire Solar Cells. Nano Today 2017, 12, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPierre, R.R.; Robson, M.; Azizur-Rahman, K.M.; Kuyanov, P. A Review of III–V Nanowire Infrared Photodetectors and Sensors. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPierre, R.R.; Chia, A.C.E.; Gibson, S.J.; Haapamaki, C.M.; Boulanger, J.; Yee, R.; Kuyanov, P.; Zhang, J.; Tajik, N.; Jewell, N.; et al. III–V Nanowire Photovoltaics: Review of Design for High Efficiency. Phys. Status Solidi RRL – Rapid Res. Lett. 2013, 7, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanowires for Energy: A Review | Applied Physics Reviews | AIP Publishing. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apr/article-abstract/5/4/041305/124236/Nanowires-for-energy-A-review?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Mukai, T. Recent Progress in Group-III Nitride Light-Emitting Diodes. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2002, 8, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REN21. 2022. Renewables 2022 Global Status Report. (Paris: REN21 Secretariat). ISBN 978-3-948393-04-5.

- Downs, C.; Vandervelde, T.E. Progress in Infrared Photodetectors Since 2000. Sensors 2013, 13, 5054–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, S.M.; Li, Y.; Ng, K.K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices; John Wiley & Sons, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-61800-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. PHYSICS OF SOLAR CELLS, THE; 1st edition.; ICP: London: River Edge, NJ, 2003; ISBN 978-1-86094-349-2. [Google Scholar]

- Alhalaili, B.; Peksu, E.; Mcphillips, L.N.; Ombaba, M.M.; Islam, M.S.; Karaagac, H. 4 - Nanowires for Photodetection. In Photodetectors (Second Edition); Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials; Nabet, B., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2023; pp. 139–197. ISBN 978-0-08-102795-0. [Google Scholar]

- Trojnar, A.H.; Valdivia, C.E.; LaPierre, R.R.; Hinzer, K.; Krich, J.J. Optimizations of GaAs Nanowire Solar Cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2016, 6, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N. Physics and Design for 20% and 25% Efficiency Nanowire Array Solar Cells. Nanotechnology 2018, 30, 074002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryasin, V.; Bucci, D.; Rafhay, Q.; Panicco, F.; Michallon, J.; Kaminski-Cachopo, A. Technological Guidelines for the Design of Tandem III-V Nanowire on Si Solar Cells from Opto-Electrical Simulations. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 172, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G173-03(2020), Standard Tables for Reference Solar Spectral Irradiances: Direct Normal and Hemispherical on 37° Tilted Surface, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2020.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H.J. Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of P-n Junction Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Siefer, G.; Hao, X. Solar Cell Efficiency Tables (Version 62). Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2023, 31, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrachowina, L.; Chen, Y.; Barrigón, E.; Wallenberg, R.; Borgström, M.T. Realization of Axially Defined GaInP/InP/InAsP Triple-Junction Photovoltaic Nanowires for High-Performance Solar Cells. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 27, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J.; Anttu, N.; Vainorius, N.; Borg, B.M.; Wernersson, L.-E. Diameter-Dependent Photocurrent in InAsSb Nanowire Infrared Photodetectors. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttu, N.; Mäntynen, H.; Sorokina, A.; Turunen, J.; Sadi, T.; Lipsanen, H. Applied Electromagnetic Optics Simulations for Nanophotonics. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 131102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N. Geometrical Optics, Electrostatics, and Nanophotonic Resonances in Absorbing Nanowire Arrays. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N.; Heurlin, M.; Borgström, M.T.; Pistol, M.-E.; Xu, H.Q.; Samuelson, L. Optical Far-Field Method with Subwavelength Accuracy for the Determination of Nanostructure Dimensions in Large-Area Samples. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2662–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghesi, A.; Guizzetti, G. Gallium Phosphide (GaP). In Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Palik, E.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, 1985; pp. 445–464. ISBN 978-0-08-054721-3. [Google Scholar]

- Palik, E.D. Gallium Arsenide (GaAs). In Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Palik, E.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, 1985; pp. 429–443. ISBN 978-0-08-054721-3. [Google Scholar]

- Glembocki, O.J.; Piller, H. Indium Phosphide (InP). In Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Palik, E.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, 1997; pp. 503–516. ISBN 978-0-12-544415-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pauk, E.D.; Holm, R.T. Indium Arsenide (InAs). In Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Palik, E.D., Ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, 1997; pp. 479–489. ISBN 978-0-12-544415-6. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, V.; Haggren, T.; Wong, W.W.; Tan, H.H.; Jagadish, C. Topical Review: Pathways toward Cost-Effective Single-Junction III–V Solar Cells. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2021, 55, 143002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Nanowires for High-Efficiency, Low-Cost Solar Photovoltaics. Crystals 2019, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrigón, E.; Hultin, O.; Lindgren, D.; Yadegari, F.; Magnusson, M.H.; Samuelson, L.; Johansson, L.I.M.; Björk, M.T. GaAs Nanowire Pn-Junctions Produced by Low-Cost and High-Throughput Aerotaxy. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, L.C.; Moewe, M.; Chase, C.; Kobayashi, N.P.; Chang-Hasnain, C.; Crankshaw, S. Critical Diameter for III-V Nanowires Grown on Lattice-Mismatched Substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 043115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroff, P.; Messing, M.E.; Borg, B.M.; Dick, K.A.; Deppert, K.; Wernersson, L.-E. InSb Heterostructure Nanowires: MOVPE Growth under Extreme Lattice Mismatch. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 495606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrigón, E.; Heurlin, M.; Bi, Z.; Monemar, B.; Samuelson, L. Synthesis and Applications of III–V Nanowires. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9170–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loitsch, B.; Rudolph, D.; Morkötter, S.; Döblinger, M.; Grimaldi, G.; Hanschke, L.; Matich, S.; Parzinger, E.; Wurstbauer, U.; Abstreiter, G.; et al. Tunable Quantum Confinement in Ultrathin, Optically Active Semiconductor Nanowires Via Reverse-Reaction Growth. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2195–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokhovets, S.; Gobsch, G.; Ambacher, O. Excitonic Contribution to the Optical Absorption in Zinc-Blende III-V Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 155209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhard, N.; Zenger, S.; Morkötter, S.; Rudolph, D.; Weiss, M.; Krenner, H.J.; Karl, H.; Abstreiter, G.; Finley, J.J.; Koblmüller, G.; et al. Ultrafast Photodetection in the Quantum Wells of Single AlGaAs/GaAs-Based Nanowires. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 6869–6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, R.J.; Gauer, C.; Wixforth, A.; Kotthaus, J.P.; Brar, B.; Kroemer, H. Intersubband Resonances in InAs/AlSb Quantum Wells: Selection Rules, Matrix Elements, and the Depolarization Field. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 7903–7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N.; Abrand, A.; Asoli, D.; Heurlin, M.; Åberg, I.; Samuelson, L.; Borgström, M. Absorption of Light in InP Nanowire Arrays. Nano Res. 2014, 7, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chi, C.-Y.; T. Fountaine, K.; Yao, M.; A. Atwater, H.; Daniel Dapkus, P.; S. Lewis, N.; Zhou, C. Optical, Electrical, and Solar Energy-Conversion Properties of Gallium Arsenide Nanowire -Array Photoanodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N.; Iqbal, A.; Heurlin, M.; Samuelson, L.; Borgström, M.T.; Pistol, M.-E.; Yartsev, A. Reflection Measurements to Reveal the Absorption in Nanowire Arrays. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 1449–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Chen, G. Analysis of Optical Absorption in Silicon Nanowire Arrays for Photovoltaic Applications. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 3249–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A. Self-Consistent Optical Parameters of Intrinsic Silicon at 300K Including Temperature Coefficients. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, G.; Zhou, Z.; Scofield, A.; Huffaker, D.L. Direct-Bandgap Epitaxial Core–Multishell Nanopillar Photovoltaics Featuring Subwavelength Optical Concentrators. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagytė, V.; Anttu, N. Modal Analysis of Resonant and Non-Resonant Optical Response in Semiconductor Nanowire Arrays. Nanotechnology 2018, 30, 025710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupec, J.; Witzigmann, B. Dispersion, Wave Propagation and Efficiency Analysis of Nanowire Solar Cells. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 10399–10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttu, N.; Xu, H.Q. Coupling of Light into Nanowire Arrays and Subsequent Absorption. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 7183–7187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Wen, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y. Analysis of Optical Absorption in GaAs Nanowire Arrays. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Shen, Y.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y. Theoretical Analysis and Modeling of Light Trapping in High Efficicency GaAs Nanowire Array Solar Cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 143116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; LaPierre, R.R.; Li, M.; Chen, K.; He, J.-J. Optical Characteristics of GaAs Nanowire Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Lin, C.; Povinelli, M.L. Broadband Absorption of Semiconductor Nanowire Arrays for Photovoltaic Applications. J. Opt. 2012, 14, 024004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountaine, K.T.; Cheng, W.-H.; Bukowsky, C.R.; Atwater, H.A. Near-Unity Unselective Absorption in Sparse InP Nanowire Arrays. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.W.; Love, J.D. Optical Waveguide Theory; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-412-24250-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mäntynen, H.; Anttu, N.; Lipsanen, H. Nanowire Oligomer Waveguide Modes towards Reduced Lasing Threshold. Materials 2020, 13, 5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traviss, D.J.; Schmidt, M.K.; Aizpurua, J.; Muskens, O.L. Antenna Resonances in Low Aspect Ratio Semiconductor Nanowires. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 22771–22787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Leu, P.W. Tunable and Selective Resonant Absorption in Vertical Nanowires. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 3756–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, K.; Wober, M.; Steinvurzel, P.; Schonbrun, E.; Dan, Y.; Ellenbogen, T.; Crozier, K.B. Multicolored Vertical Silicon Nanowires. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N. Absorption of Light in a Single Vertical Nanowire and a Nanowire Array. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anttu, N.; Namazi, K.L.; Wu, P.M.; Yang, P.; Xu, H.; Xu, H.Q.; Håkanson, U. Drastically Increased Absorption in Vertical Semiconductor Nanowire Arrays: A Non-Absorbing Dielectric Shell Makes the Difference. Nano Res. 2012, 5, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light. Available online: http://ab-initio.mit.edu/book/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Anttu, N.; Mäntynen, H.; Sadi, T.; Matikainen, A.; Turunen, J.; Lipsanen, H. Comparison of Absorption Simulation in Semiconductor Nanowire and Nanocone Arrays with the Fourier Modal Method, the Finite Element Method, and the Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method. Nano Express 2020, 1, 030034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahfarokhi, O.M.; Anttu, N.; Samuelson, L.; Åberg, I. Performance of GaAs Nanowire Array Solar Cells for Varying Incidence Angles. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2016, 6, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abujetas, D.R.; Paniagua-Domínguez, R.; Sánchez-Gil, J.A. Unraveling the Janus Role of Mie Resonances and Leaky/Guided Modes in Semiconductor Nanowire Absorption for Enhanced Light Harvesting. ACS Photonics 2015, 2, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Kapadia, R.; Leu, P.W.; Zhang, X.; Chueh, Y.-L.; Takei, K.; Yu, K.; Jamshidi, A.; Rathore, A.A.; Ruebusch, D.J.; et al. Ordered Arrays of Dual-Diameter Nanopillars for Maximized Optical Absorption. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3823–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedenhofen, S.L.; Janssen, O.T.A.; Grzela, G.; Bakkers, E.P.A.M.; Gómez Rivas, J. Strong Geometrical Dependence of the Absorption of Light in Arrays of Semiconductor Nanowires. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 2316–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Stevens, E.; Leu, P.W. Strong Broadband Absorption in GaAs Nanocone and Nanowire Arrays for Solar Cells. Opt. Express 2014, 22, A386–A395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.P.; LaPierre, R.R. Simulation of Optical Absorption in Conical Nanowires. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 9544–9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekcan, B.; van Kasteren, B.; Grayli, S.V.; Shen, D.; Tam, M.C.; Ban, D.; Wasilewski, Z.; Tsen, A.W.; Reimer, M.E. Semiconductor Nanowire Metamaterial for Broadband Near-Unity Absorption. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Tang, X.; Wang, K.; Li, X. An Analytic Approach for Optimal Geometrical Design of GaAs Nanowires for Maximal Light Harvesting in Photovoltaic Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Gong, L.; Ai, L.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X. Enhanced Photovoltaic Performance of Nanowire Array Solar Cells with Multiple Diameters. Opt. Express 2018, 26, A974–A983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Povinelli, M.L. Optimal Design of Aperiodic, Vertical Silicon Nanowire Structures for Photovoltaics. Opt. Express 2011, 19, A1148–A1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturmberg, B.C.P.; Dossou, K.B.; Botten, L.C.; Asatryan, A.A.; Poulton, C.G.; McPhedran, R.C.; Sterke, C.M. de Absorption Enhancing Proximity Effects in Aperiodic Nanowire Arrays. Opt. Express 2013, 21, A964–A969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Höhn, O.; Tucher, N.; Pistol, M.-E.; Anttu, N. Optical Analysis of a III-V-Nanowire-Array-on-Si Dual Junction Solar Cell. Opt. Express 2017, 25, A665–A679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benali, A.; Michallon, J.; Regreny, P.; Drouard, E.; Rojo, P.; Chauvin, N.; Bucci, D.; Fave, A.; Kaminski-Cachopo, A.; Gendry, M. Optical Simulation of Multijunction Solar Cells Based on III-V Nanowires on Silicon. Energy Procedia 2014, 60, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcer, D.; Hrachowina, L.; Hessman, D.; Borgström, M.T. Processing and Characterization of Large Area InP Nanowire Photovoltaic Devices. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 295402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N. Absorption of Light in Finite Semiconductor Nanowire Arrays and the Effect of Missing Nanowires. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Xu, L.; Gao, Q.; Alabadla, A.; Peng, K.; Vora, K.; T. Hattori, H.; Hoe Tan, H.; et al. Investigation of Light–Matter Interaction in Single Vertical Nanowires in Ordered Nanowire Arrays. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 3527–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grain, N.; Kim, S. Insight into Refractive Index Modulation as Route to Enhanced Light Coupling in Semiconductor Nanowires. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A, S.B.E. Fundamentals of Photonics, 2nd Ed.; W, 2012.

- Wilson, D.P.; LaPierre, R.R. Corrugated Nanowires as Distributed Bragg Reflectors. Nano Express 2022, 3, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaeipour, M.; Pettersson, H. Enhanced Broadband Absorption in Nanowire Arrays with Integrated Bragg Reflectors. Nanophotonics 2018, 7, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaban, J.A.; Thompson, D.A.; LaPierre, R.R. GaAs Core−Shell Nanowires for Photovoltaic Applications. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, C.; Heiβ, M.; Grätzel, M.; Fontcuberta i Morral, A. Gallium Arsenide P-i-n Radial Structures for Photovoltaic Applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 173108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Nosaki, K.; Tomioka, K.; Hara, S.; Hiruma, K.; Motohisa, J.; Fukui, T. Growth of Core–Shell InP Nanowires for Photovoltaic Application by Selective-Area Metal Organic Vapor Phase Epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Express 2009, 2, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallentin, J.; Anttu, N.; Asoli, D.; Huffman, M.; Åberg, I.; Magnusson, M.H.; Siefer, G.; Fuss-Kailuweit, P.; Dimroth, F.; Witzigmann, B.; et al. InP Nanowire Array Solar Cells Achieving 13.8% Efficiency by Exceeding the Ray Optics Limit. Science 2013, 339, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstrup, P.; Jørgensen, H.I.; Heiss, M.; Demichel, O.; Holm, J.V.; Aagesen, M.; Nygard, J.; Fontcuberta i Morral, A. Single-Nanowire Solar Cells beyond the Shockley–Queisser Limit. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, G.; Scofield, A.C.; Hung, C.-H.; Huffaker, D.L. GaAs Nanopillar-Array Solar Cells Employing in Situ Surface Passivation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Huang, N.; Cong, S.; Chi, C.-Y.; Seyedi, M.A.; Lin, Y.-T.; Cao, Y.; Povinelli, M.L.; Dapkus, P.D.; Zhou, C. GaAs Nanowire Array Solar Cells with Axial p–i–n Junctions. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 3293–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, J.; Plissard, S.R.; Cavalli, A.; Vu, T.T.T.; van Veldhoven, R.P.J.; Gao, L.; Trainor, M.; Verheijen, M.A.; Haverkort, J.E.M.; et al. Efficiency Enhancement of InP Nanowire Solar Cells by Surface Cleaning. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 4113–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Cong, S.; Arab, S.; Huang, N.; Povinelli, M.L.; Cronin, S.B.; Dapkus, P.D.; Zhou, C. Tandem Solar Cells Using GaAs Nanowires on Si: Design, Fabrication, and Observation of Voltage Addition. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 7217–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, W.S.; Tran, T.-T.D.; Bhattacharya, I.; Ng, K.W.; Sun, H.; Chang-Hasnain, C. Illumination Angle Insensitive Single Indium Phosphide Tapered Nanopillar Solar Cell. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 4961–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åberg, I.; Vescovi, G.; Asoli, D.; Naseem, U.; Gilboy, J.P.; Sundvall, C.; Dahlgren, A.; Svensson, K.E.; Anttu, N.; Björk, M.T.; et al. A GaAs Nanowire Array Solar Cell With 15.3% Efficiency at 1 Sun. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2016, 6, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, D.; van Hoof, N.J.J.; Cui, Y.; van Veldhoven, P.J.; Bakkers, E.P.A.M.; Gómez Rivas, J.; Haverkort, J.E.M. High-Efficiency Nanowire Solar Cells with Omnidirectionally Enhanced Absorption Due to Self-Aligned Indium–Tin–Oxide Mie Scatterers. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 11414–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanatinia, R.; Berrier, A.; Dhaka, V.; Perros, A.P.; Huhtio, T.; Lipsanen, H.; Anand, S. Wafer-Scale Self-Organized InP Nanopillars with Controlled Orientation for Photovoltaic Devices. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 415304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otnes, G.; Barrigón, E.; Sundvall, C.; Svensson, K.E.; Heurlin, M.; Siefer, G.; Samuelson, L.; Åberg, I.; Borgström, M.T. Understanding InP Nanowire Array Solar Cell Performance by Nanoprobe-Enabled Single Nanowire Measurements. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 3038–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Ren, D.; Vullum, P.-E.; Huh, J.; Fimland, B.-O.; Weman, H. GaAs/AlGaAs Nanowire Array Solar Cell Grown on Si with Ultrahigh Power-per-Weight Ratio. ACS Photonics 2021, 8, 2355–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.J.; van Kasteren, B.; Tekcan, B.; Cui, Y.; van Dam, D.; Haverkort, J.E.M.; Bakkers, E.P.A.M.; Reimer, M.E. Tapered InP Nanowire Arrays for Efficient Broadband High-Speed Single-Photon Detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Raj, V.; Li, Z.; Tan, H.H.; Jagadish, C.; Fu, L. Self-Powered InP Nanowire Photodetector for Single-Photon Level Detection at Room Temperature. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2105729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Azimi, Z.; Li, Z.; Yu, Y.; Huang, L.; Jin, W.; Tan, H.H.; Jagadish, C.; Wong-Leung, J.; Fu, L. InAs Nanowire Arrays for Room-Temperature Ultra-Broadband Infrared Photodetection. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 10033–10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Ren, D.; Mosberg, A.B.; Vullum, P.-E.; van Helvoort, A.T.J.; Fimland, B.-O.; Weman, H. Origin of Leakage Currents and Nanowire-to-Nanowire Inhomogeneity in Radial p–i–n Junction GaAs Nanowire Array Solar Cells on Si. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kivisaari, P.; Pistol, M.-E.; Anttu, N. Optimization of the Short-Circuit Current in an InP Nanowire Array Solar Cell through Opto-Electronic Modeling. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 435404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinet-Gonzalez, P.; Barrigón, E.; Otnes, G.; Vescovi, G.; Mann, C.; France, R.M.; Welch, A.J.; Hunt, M.S.; Walker, D.; Kelzenberg, M.D.; et al. Radiation Tolerant Nanowire Array Solar Cells. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 12860–12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Pistol, M.-E.; Anttu, N. Design for Strong Absorption in a Nanowire Array Tandem Solar Cell. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroff, P.; Bolinsson, J.; Johansson, J. Crystal Phases in III–V Nanowires: From Random Toward Engineered Polytypism. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2011, 17, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttu, N.; Lehmann, S.; Storm, K.; Dick, K.A.; Samuelson, L.; Wu, P.M.; Pistol, M.-E. Crystal Phase-Dependent Nanophotonic Resonances in InAs Nanowire Arrays. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5650–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaeipour, M.; Anttu, N.; Nylund, G.; Samuelson, L.; Lehmann, S.; Pistol, M.-E. Tunable Absorption Resonances in the Ultraviolet for InP Nanowire Arrays. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 29204–29212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaeipour, M.; Anttu, N.; Nylund, G.; Berg, A.; Lehmann, S.; Pistol, M.-E. Optical Response of Wurtzite and Zinc Blende GaP Nanowire Arrays. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 30177–30187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fast, J.; Aeberhard, U.; Bremner, S.P.; Linke, H. Hot-Carrier Optoelectronic Devices Based on Semiconductor Nanowires. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2021, 8, 021309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).