1. Introduction

The Southern Aegean, situated in Greece, boasts the southernmost part of the Hellenic arc, which commences in the area W-SW of Peloponnese and runs southward, dividing into Pliny, Ptolemy, and Strabo trenches. The arc culminates to the east of Rhodes island, branching into Anatolia and South of Cyprus [

1,

2]. This region is prone to frequent seismic activity, owing to the convergence of the Eurasian and African tectonic plates, as substantiated by significant historical seismic events [

3]. This movement is caused by the subduction of the oceanic Mediterranean lithosphere under the Aegean continental one, with a speed of roughly 35 mm/year [4-10].

This study delves into the Southern Aegean region (

Figure 1), which has a significant portion of the overall recorded intermediate-depth seismic activity. This particular area is considered one of the most active ones in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea due to intense tectonic movements during the Late Quaternary period, resulting in significant uplifts in local areas and the creation of extensional faults that run in roughly two directions: WNW-ESE and NNE-SSW [4,11-13]. In the Cretan Sea, just north of Crete, there are three primary tectonic depressions between the Southern Cyclades and Crete, Karpathos, and Rhodes. The main tectonic structures in the region are oriented in a NW-SE direction towards the west and a NE-SW direction towards the east, showcasing the curvature of the Hellenic Arc. The broader area of Crete has a complex geodynamic structure where transpressional tectonics dominate the southern part of Crete, in contrast to normal and strike-slip forms on the shallow part of the crust, resulting in a heterogeneous stress field [

14,

15]. In the northern area, between Santorini and Crete, there is an observation of extension in an E-W direction, while in the western part of Crete, N-forward shortening was seen [

16] (

Figure 2).

It's interesting to note that the seismic activity in Crete and the neighbouring areas is mainly due to the geodynamics of the Aegean and Mediterranean plate convergence, with events of shallow depth (<25 km) characterizing it. However, the lack of uniform and optimal coverage with seismic stations on the island and the southern Aegean Sea and absence of local velocity models are the main disadvantages in highlighting the earthquake distribution in areas near or along the Hellenic Trench (HT). Fortunately, recent seismic sequences have led to an improvement in the local station coverage, enriching the available catalogues. With improved 1-D regional models and well-localized aftershocks recorded by dense seismic monitoring networks, the region can now provide a basis and baseline for more constrained tomographic studies. The recorded data improved the knowledge of the seismotectonic structures on the island and helped to provide a better 3-D body-wave velocity model through seismic tomography, examining the correlation between seismicity and the activation of the local fault pattern.

Seismicity studies since 1990 have revealed active Quaternary faults, major compressional structures (i.e. thrusts), and other geologic features in the back-arc basin north of Crete Island. The planes for the available focal mechanism solutions of offshore events near the Hellenic Trench south of Crete (

Figure 3) show a direction of compression to be nearly NNE-SSW, while the onshore ones appear to have an almost ESE-WNW to N-S extension, which is associated with fractures along the main mapped faults [3,12,17-19]. Historical records indicate that three large shallow earthquakes occurred in this region, with the first one occurring southwest of Crete in 365 AD, the second one occurring near Rhodes in 1303, and the third one taking place on February 16, 1810, in the area between Crete and Rhodes [

19,

20]. The existence of permanent stations of the regional Hellenic Unified Seismological Network [

21], close to the most significant events, with the nearest stations being Knossos (KNSS), Pefkos (PFKS) (Institute of Physics of the Earth's Interior and Geohazards of the Hellenic Mediterranean University Research Center; IFEGG-HMURC), and temporary ones [

22,

23] installed after large earthquakes, makes a significant contribution to the depth accuracy of the first hypocentral solution during the routine analysis in near real-time (

http://www.geophysics.geol.uoa.gr/stations/gmaps3/leaf_stations.php?map=2&lng=en).

In the area of Aegean Sea (Greece), there have been many studies conducted on regional scale over the past forty years. Seismic velocity models have been obtained for various areas including Western Greece, and Aegean Sea [24-27]. However, it's worth mentioning that the lack of permanent seismic stations in the islands of Southern Aegean has made imaging of the crustal structure more challenging. In this work, we provide new 3-D body-wave velocity models of the crust and uppermost mantle (down to 80 km) utilizing a new big collection of earthquake travel time data. These findings may aid in determining the relationships between surface geology and subsurface structures driven by complex geological processes.

2. Data and Method

The present study focuses on Crete and its neighboring regions in the Southern Aegean Sea. Several permanent stations of the Hellenic Unified Seismological Network [22,23,28-30] operate in this area, complemented by 4 temporary stations (CRE1–4) of the Geodynamics Institute of the National Observatory of Athens (GI-NOA), between September 27, 2021 and June 15, 2022, mainly contributing to the depth accuracy of the Arkalochori aftershock sequence for this period of time (

Figure 4) [21,31-33]. The initial dataset comprises 1813 events from June 2018 to February 2023, with M

L≥3.2, recorded by at least 6 stations. Since 2007 continuous waveform recordings have been obtained from HUSN in real-time, comprising of both 1-component (1 Hz) (THR2-9; Santorini Island Seismic Network operated by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki) and 3-component (either broad-band or short-period) stations, while manual arrival-time picking is applied to obtain hypocentral locations using the SeisComP3 graphical user interface [

34] and a custom regional 1-D velocity model for the region of Southern Aegean sea [

35]. In the first stage of the sequence analysis, hypocenters were located in near real-time, employing the Hypo71 single-event algorithm [

36]. Then they were relocated running the HypoInverse code [

37].

In this study, the inversion of body-wave travel-time data was based on LOTOS scheme as described by [

38]. This code was previously used for studies of many different subduction zones with similar geometry of observations and area dimensions [39-43]. For the inversion procedure, 1265 manually revised events located on the island of Crete and its neighbouring regions were included during the first step. The dataset comprised 20587 P and 15370 S arrival-times, with at least 15 phases per earthquake (at least 10 for P- and 5 and for S-picks respectively) and ratio of S to P residual smaller than 1.5 (

Figure 4). The inversion algorithm provides two different choices: a) inversion for both V

P and V

S (V

P–V

S scheme) using the respective travel-time residuals (dt

P and dt

S), and b) inversion for V

P and V

P/V

S ratio (V

P–V

P/V

S scheme) using dt

P and differential residuals, dt

S–dt

P. In the current study, tomographic inversion was applied for both schemes in order to obtain more information on the body-wave anomalies [

38,

44].

Sensitivity analysis for the available dataset was performed by applying the checkerboard synthetic test. This method uses alternating anomalies of positive and negative velocity perturbations on an initial 1-D gradient model evenly distributed in a checkerboard pattern throughout the model. The stability of the inversion is controlled by amplitude damping and flattening regularization. The inversion of the large sparse matrix was performed using Least Squares with QR decomposition (LSQR) while the optimal values of P- and S-wave amplitude damping, and smoothing as well as the station, source coordinates and origin times corrections were assessed based on the results of synthetic modeling as it is described in [38, 45-46].

3. Results

The available tomographic software necessitates as input data the longitude and latitude of the available network stations and the arrival times from the recorded seismicity. The coordinates of the hypocenter and the time of origin time are optional, as they are determined during the implementation of calculations. However, if preliminary hypocentral locations are available, they can be utilized to reduce the processing time of the operations. In addition, a generic 1-D velocity model and a set of input parameters for performing the convergence iteration steps, comprising parameterization, grid dimensions, and damping parameters, were considered [

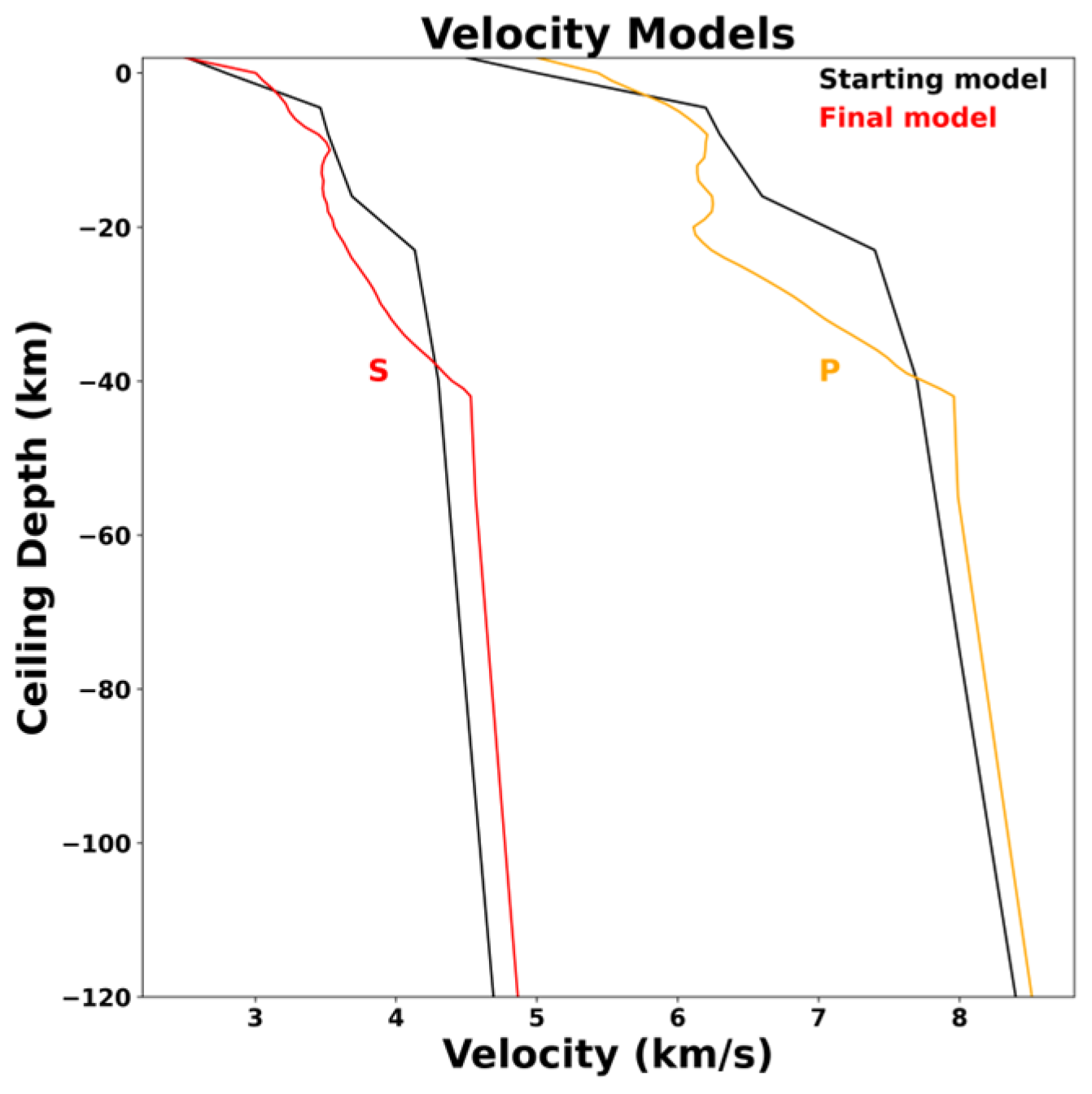

38]. As 1-D starting velocity model was set the one derived by [

35]. This model was then optimized by running the complete tomographic procedure several times by calculating the average velocities at several depths and using them as a new starting model in the next phase of complete tomographic inversion (

Figure 5).

The model parameterization of the velocity field should be able to delineate, according to the local characteristics, the shape and perspective of heterogeneities. A nodal representation was used, since the velocity field reconstructed by a three-dimensional grid does not adopt any specific geometry of heterogeneities [

47]. The interval of the grid nodes was kept significantly smaller than the expected size of the anomalies (<20 km) to weaken the distortion of the resulting models due to the grid configuration (

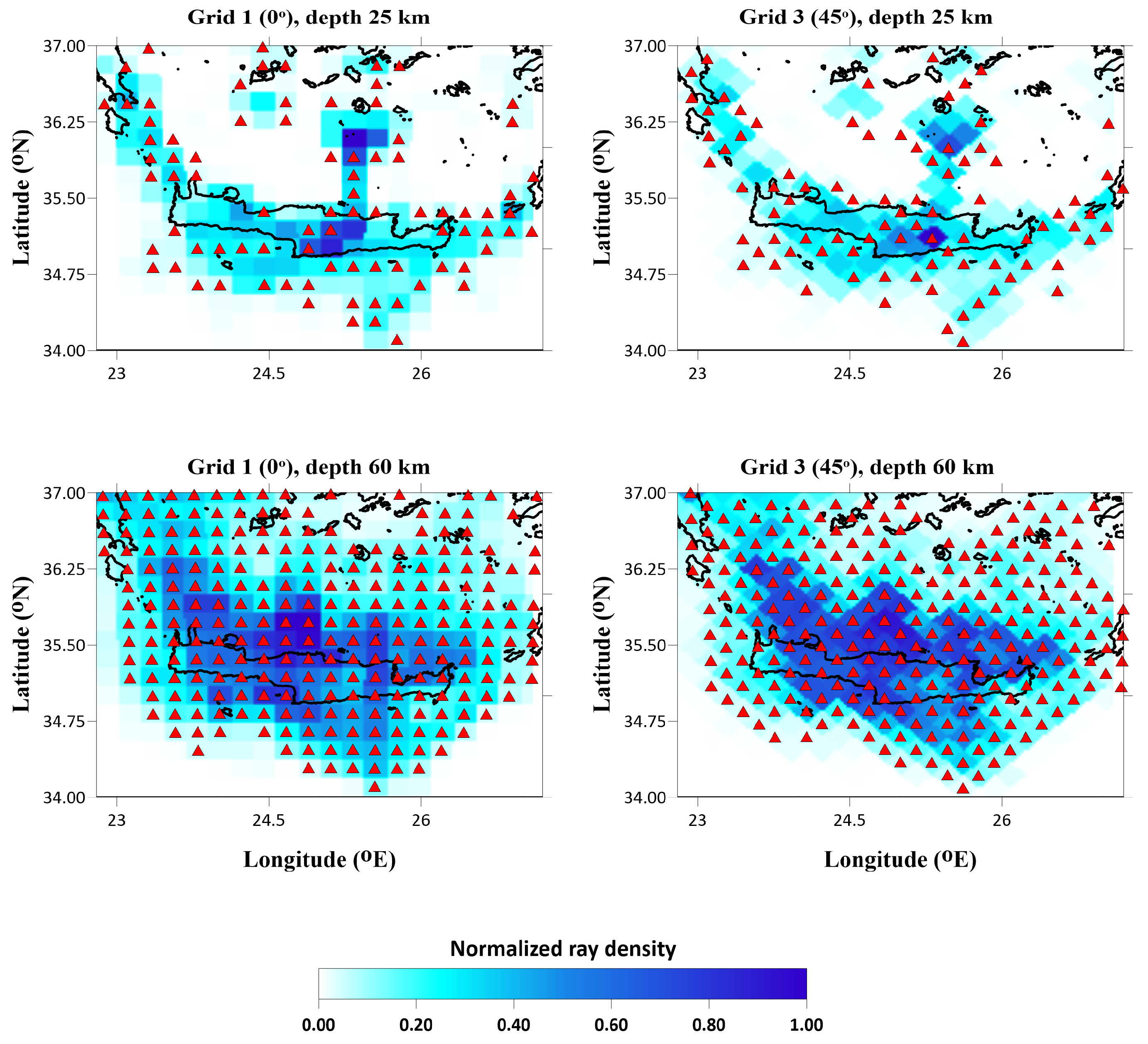

Figure 6).

The optimal grid mesh has been determined considering the stations/events geometry. In addition, to further reduce the impact of the model parameterization on the solutions, the inversion was repeated utilizing several grid orientations (e.g. 0°, 22°, 45°, and 67°). The results were aggregated via a 3-D model of the absolute P- and S-wave velocities by simple averaging. Examples of node distributions and ray densities for two of the grid orientations in different depths are presented in

Figure 6.

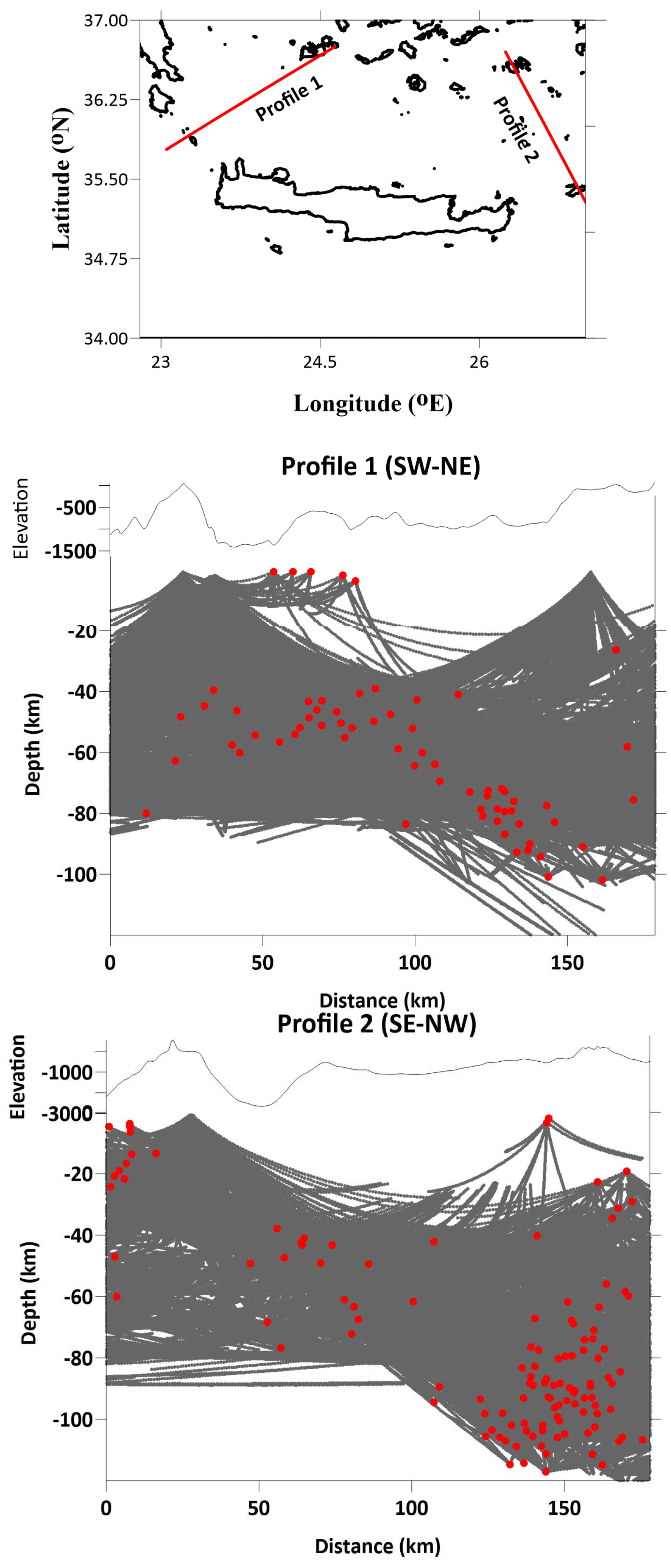

In the vertical direction, the grid spacing was inversely proportional to the ray density, but could not be smaller than a predefined value (10 km in our case;

Figure 7).

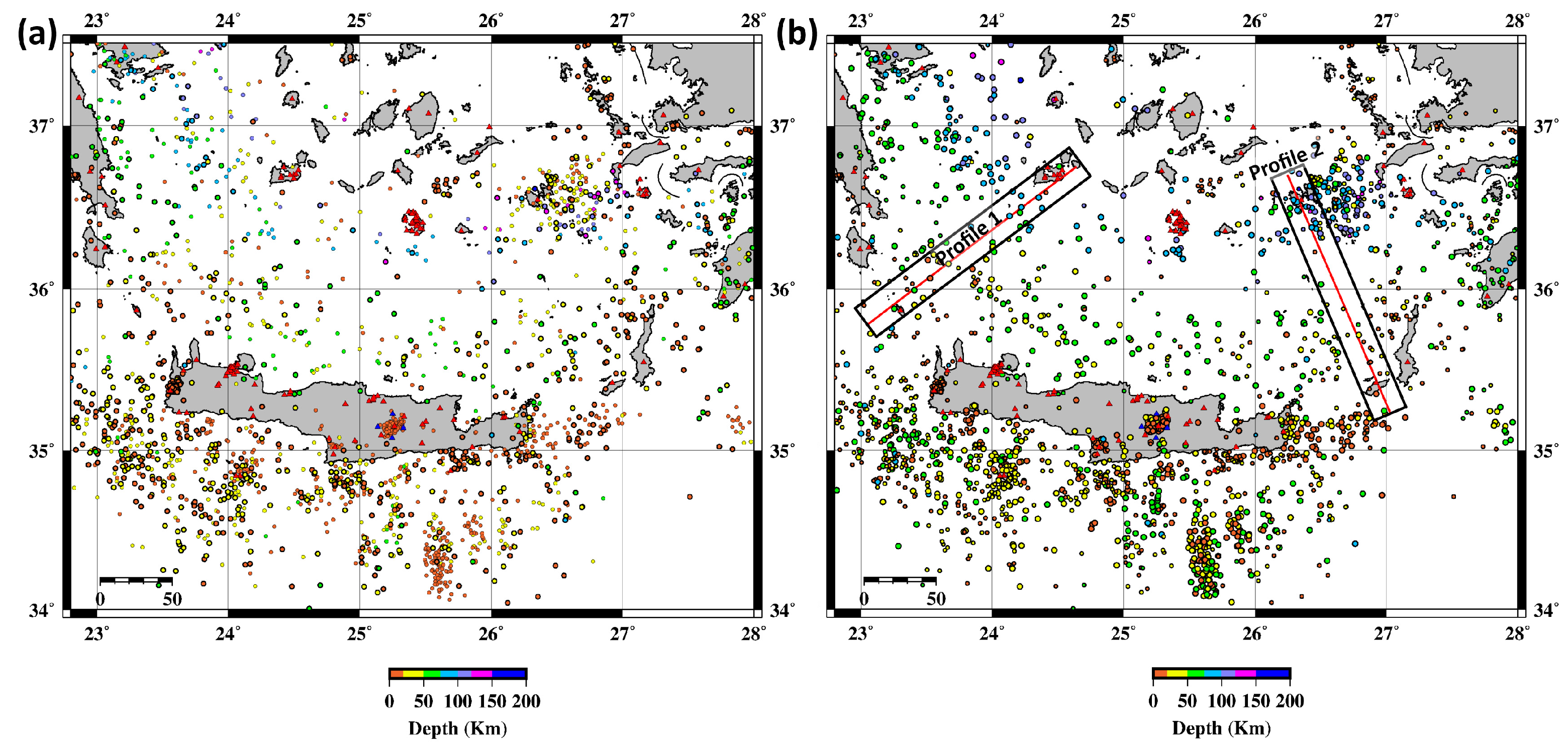

Figure 8 shows the difference between the initial and the final location of the events derived by LOTOS. In

Figure 9 (left) the P- and S-wave travel-time residuals histogram before and after earthquake relocation is shown. The initial P-wave travel time residuals were mainly distributed in the range of −2 to 1.8 s, and the average travel time residuals were 0.46 s, while the P-wave travel time residuals were mainly distributed in the range of 0.6 s after relocation, and the average residuals were reduced to 0.27 s.

Figure 9 (right) shows that the residuals of the initial S-wave travel time were also significantly reduced from 0.57 s to 0.28 s.

Figure 9 (right) shows that the travel time residuals after relocation are mainly distributed in the range of −2.2 to 2 s. As seen in

Figure 8, there is a clear difference between the initial and final locations of the events obtained by LOTOS. Moving on to

Figure 9, we see a histogram of the P- and S-wave travel-time residuals before and after the earthquake relocation. The initial P-wave travel time residuals (left) were mainly distributed in the range of −2 to 1.8 s, and the average travel time residuals were 0.46 s. After relocation, the P-wave travel time residuals were mainly distributed in the range of ±0.6 s, and the average residuals were reduced to 0.27 s. In the right side of

Figure 9, we see that the residuals of the initial S-wave travel time were also significantly reduced from 0.57 s to 0.28 s (

Table 1). The overall seismic travel time residuals after relocation are mainly distributed in the range of −2.2 to 2 s. It appears that there has been a redistribution of the depths of the earthquake foci, with a majority of them now situated within a range of 0-25 km depth. However, it is worth noting that there are still significant concentrations of earthquake foci located below 50 km depth near the volcanic centers of the SAVA.

3.1. Resolution tests

To define the fidelity area in this study, we used the checkerboard method [

48] in order to indicate the resolution and errors associated with the inversion. This method uses alternating anomalies of positive (fast) and negative (slow) velocity perturbations evenly spaced throughout the model in a checkerboard pattern. Generally, ray-path distribution, model parameterization, and smoothing determine data resolution [

49]. Among the limits imposed of such a test is the fact that the extent of near-vertical alteration of structure is difficult to be fully recognized due to a structure (checkerboard) where the diagonal elements in the vertical plane are strongly associated with dominant ray directions [

50].

The error in source mislocations for both vertical profiles was reduced after five iterations of simultaneous inversions of the source and velocity parameters (

Figure 10). It is worth noting that the uncertainty of the source depth locations was greater than that of the horizontal coordinates.

Following, a rigorous procedure was performed, ensuring that the synthetic models (checkerboard) accurately reflect the real data processing. The size of cells in the initial models corresponded to the expected anomalies, and we defined spiked regions with ±10% variability in velocity structure compared to the reference 1-D velocity model. To add a realistic element in the procedure, we added noise of 0.27 s for P- and 0.28 s for S-wave arrival-time picks, which was derived from real-data inversion. The travel-times for the paths between the source and receiver were then computed, using 3-D ray tracing that followed the bending algorithm principles, mirroring the real observation system. A test of various parameters was performed and we found the ones that gave us the most accurate results in reconstructing the model of checkerboard anomalies. To control the accuracy of the inversion, we considered errors such as mis-picks, mis-locations, and inaccurately of the determined ray-paths.

The adopted procedure included three different sets of dimensions of anomalies for the horizontal tests (20x20 km

2 , 40x40 km

2 and 80x80 km

2), in order to define the limitations of our model. The variations (%) of body-wave velocity anomalies (±10%) and the V

P/V

S ratio distribution are presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, at depths of 10, 40 and 80 km. Based on our findings, it appears that the first set of anomalies with a 20x20 km

2 grid size is either not resolved or poorly resolved at various depth slices, whereas the larger sets with a 40x40 km

2 and 80x80 km

2 cell size provide reasonable resolution throughout most of the study area (in between Pliny Trench and the central-eastern part of SAVA). The 40x40 km

2 size pattern was particularly robustly resolved in most parts of the study area at shallower depths, up to around 40 km. However, at a depth of approximately 60 km, the 80x80 km

2 anomalies were more easily resolved than the smaller ones. It seems that the models with smaller anomalies were not as clearly distinguished at deeper depth slices.

It's worth noting that the anomalies of 20 km board size were not well-resolved for either the P- or S-wave velocity models, while the respective ones of 40 and 80 km were reasonably restored in all depth intervals (10-80 km), in the major part of the study area (34.75°-35.9°N, 23.0°-26.1°E). The results of the checkerboard tests suggest that there is a horizontal smearing towards the NE part of the study area, likely due to a lack of seismological stations and sparse epicentral distribution.

To estimate the vertical resolution, we performed a synthetic test with anomalies defined along vertical profiles (

Figure 14). Based on the patterns that we needed to investigate, we began setting the size of the checkerboard anomalies. We began with a board of 20 km in the horizontal direction while in the vertical one, the signs of the anomalies changed at depths of 20, 40, 60 and 80 km. It seems that for the shallower part of the model (~60 km), the vertical resolution was sufficient to detect the change in the anomaly sign at a depth of 20, 40 and 60 km. However, the model did not have sufficient resolution to recognize anomaly sign changes below 80 km. It seems that we have some horizontal smearing towards the edges of the study area (SW and NE), potentially due to a lack of seismological stations and reliable hypocentral solutions. It's interesting to note that the transition between negative and positive velocity anomalies is reconstructed sufficiently for the main part of the study area in profile 1 (west), with some horizontal smearing along the ray paths towards the NE. Profile 2 (east) appears to be less resolved than profile 1, particularly to the northern part of the section and for depths below 60 km. It's possible that the lower vertical resolution than the respective horizontal one may be due to source and velocity parameters trade off, as suggested by previous studies [

51]. The synthetic tests we conducted showed that the absolute amplitudes of the body-wave anomalies were up to 4-5% smaller than the respective ones of the starting checkerboard grid. Overall, the checkerboard model was recovered to a satisfactory level, despite the presence of errors and outliers.

3.2. Tomographic inversion results

The generated P-, S-velocity anomalies (%), and the V

P/V

S ratio distribution are depicted in four horizontal slices at 10, 25, 40 and 80 km depth (

Figure 15), and two cross-sections (profile 1 and 2) perpendicular to the western and eastern part of the HT (

Figure 16). The evaluation of the acquired values in both horizontal slices and vertical profiles is restricted to model portions with a sufficient reconstruction of the checkerboard (

Figure 14). For P- and S-waves, velocity perturbations in the shallow depth layers range between -10 and +10%, while the V

P/V

S ratio varies between 1.66 and 1.98. According to synthetic modeling tests, the velocity structure is resolvable for depths ranging from 25 to 60 km and fairly reconstructed at 80 km depth for the central part of the area of study (34.75º-36.15ºN, 23.2º-26.25ºE). This fact, together with intense ray coverage down to a depth of 40 km (

Figure 6), lends confidence to the interpretation of the 3-D inversion results.

It's interesting to note the prominent features identified by the present tomographic model, particularly the continuous fast velocity anomalies located north of Crete. This pattern was also identified in previous studies [

25,

52,

53,

54], lending credibility to the model's accuracy. These high velocities are mainly attributed to be the subduction of the Tethys oceanic lithosphere beneath the Aegean, a conclusion that is consistent with previous research. Additionally, it's worth noting that the front of the Hellenic Subduction Zone (HSZ) slab appears to be parallel to the HT in the region between Chania and Antikythera. Finally, it's intriguing that the high velocity anomalies are distributed in an amphitheatre shape that is almost parallel to the HSZ, with the area of the positive anomalies increasing with depth.

Based on the results of this study, there are some noteworthy discontinuities, highlighted by the slow and fast body-waves (P,S) velocity anomalies towards the western, central-western region of Crete, specifically within shallow depths (10-25 km). It is plausible that this pattern is correlated with the local neotectonic faults striking in that direction, as illustrated in

Figure 15. These faults divide the Mesozoic Pindos Unit basement from the Neogene and Quaternary deposits. A similar pattern of body-wave velocity (P, S) anomalies is observed in the same depth slices (10 and 25 km) near the town of Chania, with slow and fast deviations from the reference 1-D model to the west and east of Kissamos gulf. This shallow, broad, slow V

P anomaly down to 25 km depth characterizes the collapsed zones.

4. Discussion

The derived anomalies of body waves (dV

P, dV

S) and, V

P/V

S ratio provided important information about the Southern Aegean regional tectonics, and secondarily active faults of smaller scale (>20 km). In the study area, the seismic tomography model revealed a predominance of high-velocity anomalies North of Crete, in the region between Kythera and Karpathos, while close to the SAVA, the region is marked by significant low-velocity anomalies in the crust and uppermost mantle, beneath the active arc volcanoes. The seismicity related to the HSZ is connected to high-velocity anomalies in the Sea of Crete and the islands south of SAVA. Its extension reaches up to 120-150 km (

Figure 16), while the observed termination of the seismic activity in even greater depths may be due to plate dehydration embrittlement or runaway thermal shear stress, as highlighted by studies in similar environments [

57].

More specifically, the main anomalies that have been identified in the region are (a) a large zone of fast velocity anomalies (dV

P, dV

S), and low V

P/V

S ratio in the shallow part of the Hellenic island-arc area (Kythera-Crete-Karpathos,

Figure 17) (b) a region of slow (negative) anomalies in the SAVA that may reflect hot upwelling flow related to slab dehydration, causing arc magmatism and volcanism in this region [

44,

46,

55,

56] (c) an area of high V

P/V

S ratio (~1.85) north of the Sea of Crete, in the SE part of Peloponnese and its offshore area in the depth slices of 10 and 25 km. [

26] have related this part to fluid-saturated sediments, non-consolidated soils, and/or cracked subducted crust. The results in profile 1 (

Figure 16) for depths ranging from 10 to 30 km may indicate a possible upward movement of fluids connected to this mechanism. However, it's important to keep in mind that the limited vertical resolution provided by the synthetic tests makes it challenging to give a definite interpretation of these results. In

Figure 17 we mark the upper limit of the western segment of the HSZ slab. In the SW-NE direction, the slab’s dip decreases from ~60° (<40 km) to ~30-40° in depths greater than 70 km. The subduction depth is consistent with the results of [

58].

In shallow depths (10-25 km), near the island of Crete, some anomalies of smaller size have been noticed. The contrast between fast and slow anomalies is mainly linked to the local fault pattern, which produces a comparable distribution of V

P/V

S ratio (

Figure 16; Matala, Ptolemy Trench: 34.75º-35.15ºN, 25.25º-25.75ºE). This anomaly distribution is mainly affected by local surface geology at these depths [

44,

45]. At shallow depth (10 km), close to the city of Heraklion, a discontinuity of fast to the east and slow to the west of V

P anomalies is discovered, possibly related to the 2021-2022 earthquake sequence of Arkalochori [31-33,59] The formed anticorrelation between slow P- and fast S-wave velocity perturbations form low values of the V

P/V

S ratio (~1.70-1.73). This result supports the high-density fault pattern in this area as tectonic studies have shown [

9,

18] and the thick Neogene to Quaternary sediments [

31,

60].

5. Conclusions

Based on the travel times of the manually revised events from 2018 to 2023, we obtained a new high-resolution 3-D VP model of the crust and upper mantle on regional scale for the region of the Southern Aegean. The resulting 3-D velocity models aimed to the improvement of the hypocentral parameters of the seismic events that occurred in this area. This process served as a springboard to a more detailed image of velocity anomalies that were obtained in the following stage of the tomographic inversion.

Both P- and S-wave velocity anomalies, as well as the distribution VP/VS ratio, support the existence of a thin crust west of the island, in contrast to a thicker one under Crete, which constitutes the accretionary prism in this portion of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea.

The regional distribution of seismic activity, and body-wave velocity anomalies (P, S), and VP/VS ratio values revealed:

A complex shallow (<10 km) structure in Crete's central region mainly attributed to the dense pattern of neotectonic faults;

A region of significant low-velocity anomalies in the crust and uppermost mantle, close to the SAVA, marked by the active arc volcanoes;

A smoother and more continuous image in deeper slices (>40km) where high VP/VS ratio (>1.82) distribution is observed;

The existence of a low-angle positive anomaly of VP correlated to the observed intermediate-depth seismicity (H≥40 km) in this part of the study area. This result could be related to the diving HSZ slab.

It seems that additional research is necessary to fully understand the Seismic Hazard of Crete. Additionally, expanding the research areas will be useful in investigating the geometry of the Wadati-Benioff zone in the Southern Aegean, the properties of the seismogenic layer, and comparing this data with past studies and other regions globally. It may also be worth exploring the possibility of a tear in the slab near Karpathos and Rhodes Island in the eastern portion of the HSZ.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, A.K. and F.V.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K. and F.V.; formal analysis, A.K. and F.V.; investigation, A.K. and F.V.; resources, A.K. and F.V.; data curation, A.K. and F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and F.V.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

We used data from the following seismic networks, HL (Institute of Geodynamics, National Observatory of Athens, doi: 10.7914/SN/HL), HP (University of Patras, doi: 10.7914/SN/HP), HT (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, doi: 10.7914/SN/HT), HA (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, doi: 10.7914/SN/HA), HC (Seismological Network of Crete, doi:10.7914/SN/HC) and HI Institute of Engineering Seismology and Earthquake Engineering, doi: 10.7914/SN/HI) networks.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McKenzie, D. Active tectonics of the Alpine-Himalayan belt: the Aegean Sea and surrounding regions Geophys. J. R. Astr. Soc. 55, 1978, 217–254.

- Le Pichon, X.; Angelier, J. The hellenic arc and trench system: A key to the neotectonic evolution of the eastern mediterranean area. Tectonophysics 1979, 60, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazachos, B.C.; Papazachou, C. The Earthquakes of Greece; Ziti Publ.: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2003; p. 286. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JA, White NJ (1989) Normal faulting in the upper continental crust: observations from regions of active extension, J Strucr Geol,11, 15-36.

- Le Pichon X, Chamot-Rooke N, Lallemant S (1995) Geodetic determination of kinematics of central Greece with respect to Europe: implications for eastern Mediterranean tectonics. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 12675–12690.

- McClusky, S.; Balassanian, S.; Barka, A.; Demir, C.; Ergintav, S.; Georgiev, I.; Gurkan, O.; Hamburger, M.; Hurst, K.; Kahle, H.; et al. Global Positioning System constraints on plate kinematics and dynamics in the eastern Mediterranean and Caucasus. J. Geophys. Res. 2000, 105, 5695–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briole, P.; Ganas, A.; Elias, P.; Dimitrov, D. The GPS velocity field of the Aegean. New observations, contribution of the earthquakes, crustal blocks model. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 226, 468–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilinger, R.; McClusky, S.; Paradissis, D.; Ergintav, S.; Vernant, P. Geodetic constraints on the tectonic evolution of the Aegean region and strain accumulation along the Hellenic subduction zone. Tectonophysics 2010, 488, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, R.; Catalano, S.; Monaco, C.; Romagnoli, G.; Tortorici, G.; Tortorici, L. Active faulting on the island of Crete (Greece). Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 183, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.; Jackson, J. Earthquake mechanisms and active tectonics of the Hellenic subduction zone. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 181, 966–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, V.; Baika, K.; Fischer, P.; Hadler, H.; Obrocki, L.; Willershäuser, T.; Tzigounaki, A.; Tsigkou, A.; Reicherter, K.; Papanikolaou, I.; et al. The sedimentary and geomorphological imprint of the AD 365 tsunami on the coasts of southwestern Crete (Greece) – Examples from Sougia and Palaiochora. Quat. Int. 2018, 473, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanidis, V.; Kassaras, I. Contemporary crustal stress of the Greek region deduced from earthquake focal mechanisms. J. Geodyn. 2018, 123, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakis, E.; Alexopoulos, J. Recognition of strike-slip faulting on the supra-detachment basin of Messara (central Crete Island) with remote sensing image interpretation techniques. In Proceedings of the 4th EARSeL Workshop on Remote Sensing and Geology, Mykonos, Greece, 24–25 May 2012; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kokinou, E.; Moisidi, M.; Tsanaki, I.; Tsakalaki, E.; Tsiskaki, E.; Sarris, A.; Vallianatos, F. A seismotectonic study for the Heraklion basin in Crete (Southern Hellenic arc, Greece). Int. J. Geol. 2008, 2, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, M.A.; Billiris, H.; Paradissis, D.; Veis, G.; Avallone, A.; Briole, P.; McClusky, S.; Nocquet, J.-M.; Palamartchouk, K.; Parsons, B.; et al. A new velocity field for Greece: Implications for the kinematics and dynamics of the Aegean. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviris, G.; Papadimitriou, P.; Kravvariti, P.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Voulgaris, N.; Makropoulos, K. A detailed seismic anisotropy study during the 2011–2012 unrest period in the Santorini Volcanic Complex. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2015, 238, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Ganas, A.; Tzanis, A.; Kosma, C.; Karakonstantis, A.; Valkaniotis, S.; Chailas, S.; Kouskouna, V.; Papadimitriou, P. The New Seismotectonic Atlas of Greece (v1.0) and Its Implementation. Geosciences 2020, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganas, A.; Oikonomou, I.A.; Tsimi, C. NOAfaults: a digital database for active faults in Greece. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2017, 47, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, P.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Kaviris, G.; Voulgaris, N.; Makropoulos, K. The Santorini Volcanic Complex: A detailed multi-parameter seismological approach with emphasis on the 2011–2012 unrest period. J. Geodyn. 2015, 85, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.A. On the interpretation of large-scale seismic tomography images in the Aegean sea area. Ann. Geophys. 1997, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelidis, C.P.; Triantafyllis, N.; Samios, M.; Boukouras, K.; Kontakos, K.; Ktenidou, O.-J.; Fountoulakis, I.; Kalogeras, I.; Melis, N.S.; Galanis, O.; et al. Seismic Waveform Data from Greece and Cyprus: Integration, Archival, and Open Access. Seism. Res. Lett. 2021, 92, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Mediterranean University Research Center (former Technological Educational Institute of Crete). Seismological Network of Crete; International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks: Crete, Greece, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Geodynamics-National Observatory of Athens. Hellenic Seismological Network, University of Athens, Seismological Laboratory [Data Set]. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. 2008. Available online: https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/HL/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Spakman, W.; Nolet, G. Imaging algorithms, accuracy and resolution in delay time tomography. In Mathematical Geophysics: A Survey of Recent Developments in Seismology and Geodynamics; Vlaar, N.J., Nolet, G., Wortel, M.J.R., Cloetingh, S.A.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1988; pp. 155–187. [Google Scholar]

- Papazachos, B.C.; Nolet, G. P and S deep velocity structure of the Hellenic area obtained by robust non-linear inversion of arrival times. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 1997, 83499 8367.

- Halpaap, F.; Rondenay, S.; Ottemöller, L. Seismicity, Deformation, and Metamorphism in the Western Hellenic Subduction Zone: New Constraints From Tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2018, 123, 3000–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Papadimitriou, P. Deep structure of the Hellenic lithosphere from teleseismic Rayleigh-wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 221, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Athens. Hellenic Seismological Network, University of Athens, Seismological Laboratory [Data Set]. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. 2008. Available online: https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/HA/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Seismological Network [Data Set]. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. 1981. Available online: https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/HT/ (accessed on accessed on 31 May 2023).

- ITSAK. Arkalochori Earthquakes, Μ 6.0 on 27/09/2021 & Μ 5.3 on 28/09/2021: Preliminary Report—Recordings of the ITSAK Accelerometric Network and Damage on the Natural and Built Environment; ITSAK Research Unit: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2021; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilakis, E.; Kaviris, G.; Kapetanidis, V.; Papageorgiou, E.; Foumelis, M.; Konsolaki, A.; Petrakis, S.; Evangelidis, C.P.; Alexopoulos, J.; Karastathis, V.; et al. The 27 September 2021 Earthquake in Central Crete (Greece)—Detailed Analysis of the Earthquake Sequence and Indications for Contemporary Arc-Parallel Extension to the Hellenic Arc. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos, F.; Michas, G.; Hloupis, G.; Chatzopoulos, G. The Evolution of Preseismic Patterns Related to the Central Crete (Mw6.0) Strong Earthquake on 27 September 2021 Revealed by Multiresolution Wavelets and Natural Time Analysis. Geosciences 2022, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianatos, F.; Karakonstantis, A.; Michas, G.; Pavlou, K.; Kouli, M.; Sakkas, V. On the Patterns and Scaling Properties of the 2021–2022 Arkalochori Earthquake Sequence (Central Crete, Greece) Based on Seismological, Geophysical and Satellite Observations. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, Y.; Clinton, J.F.; Cauzzi, C.; Hauksson, E.; Jónsdóttir, K.; Marius, C.G.; Pinar, A.; Salichon, J.; Sokos, E. The Virtual Seismologist in SeisComP3: A New Implementation Strategy for Earthquake Early Warning Algorithms. Seism. Res. Lett. 2016, 87, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakonstantis, A. 3-D Simulation of Crust and Upper Mantle Structure in the Broader Hellenic Area through Seismic Tomography. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geophysics-Geothermics, Faculty of Geology, University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2017. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.H.K.; Lahr, J.C. HYP071 (Revised): A Computer Program for Determining Hypocenter, Magnitude, and First Motion Pattern of Local Earthquakes; U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 75-311; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, F.W. User’s Guide to HYPOINVERSE-2000, a Fortran Program to Solve for Earthquake Locations and Magnitudes, 2002-171; United States Department Of The Interior Geological Survey: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Koulakov, I. LOTOS Code for Local Earthquake Tomographic Inversion: Benchmarks for Testing Tomographic Algorithms. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 2009, 99, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, G.; Özel, N.M.; Koulakov, I. Investigating P- and S-wave velocity structure beneath the Marmara region (Turkey) and the surrounding area from local earthquake tomography. Earth, Planets Space 2016, 68, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, H. Tomographic Imaging of the Seismic Structure Beneath the East Anatolian Plateau, Eastern Turkey. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2011, 169, 1749–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sychev, I.V.; Koulakov, I.; Sycheva, N.A.; Koptev, A.; Medved, I.; El Khrepy, S.; Al-Arifi, N. Collisional Processes in the Crust of the Northern Tien Shan Inferred From Velocity and Attenuation Tomography Studies. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2018, 123, 1752–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Gerya, T.; Rastogi, B.K.; Jakovlev, A.; Medved, I.; Kayal, J.R.; El Khrepy, S.; Al-Arifi, N. Growth of mountain belts in central Asia triggers a new collision zone in central India. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Jakovlev, A.; Zabelina, I.; Roure, F.; Cloetingh, S.; El Khrepy, S.; Al-Arifi, N. Subduction or delamination beneath the Apennines? Evidence from regional tomography. Solid Earth 2015, 6, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaxybulatov, K.; Koulakov, I.; Seht, M.I.-V.; Klinge, K.; Reichert, C.; Dahren, B.; Troll, V.R. Evidence for high fluid/melt content beneath Krakatau volcano (Indonesia) from local earthquake tomography. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2011, 206, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Burov, E.; Cloetingh, S.; El Khrepy, S.; Al-Arifi, N.; Bushenkova, N. Evidence for anomalous mantle upwelling beneath the Arabian Platform from travel time tomography inversion. Tectonophysics 2016, 667, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Boychenko, E.; Smirnov, S.Z. Magma Chambers and Meteoric Fluid Flows Beneath the Atka Volcanic Complex (Aleutian Islands) Inferred from Local Earthquake Tomography. Geosciences 2020, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomey, D.R.; Foulger, G.R. Tomographic inversion of local earthquake data from the Hengill-Grensdalur Central Volcano Complex, Iceland. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1989, 94, 17497–17510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, E.; Clayton, R.W. Adaptation of back projection tomography to seismic travel time problems. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1988, 93, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.M.; Crosson, R.S. Tomographic inversion for three-dimensional velocity structure at Mount St. Helens using earthquake data, J Geophys Res, 94, 1989, 148-227.

- Rawlinson, N.; Fichtner, A.; Sambridge, M.; Young, M.K. Seismic Tomography and the Assessment of Uncertainty. 2014; 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasatkina, E.; Koulakov, I.; West, M.; Izbekov, P. Structure of magma reservoirs beneath the Redoubt volcano inferred from local earthquake tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2014, 119, 4938–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulakov, I.; Kaban, M.K.; Tesauro, M.; Cloetingh, S. P- andS-velocity anomalies in the upper mantle beneath Europe from tomographic inversion of ISC data. Geophys. J. Int. 2009, 179, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Papadimitriou, P. Deep structure of the Hellenic lithosphere from teleseismic Rayleigh-wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 221, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounoudis, R.; Bastow, I.D.; Ogden, C.S.; Goes, S.; Jenkins, J.; Grant, B.; Braham, C. Seismic Tomographic Imaging of the Eastern Mediterranean Mantle: Implications for Terminal-Stage Subduction, the Uplift of Anatolia, and the Development of the North Anatolian Fault. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bock, G.; Vafidis, A.; Kind, R.; Harjes, H.-P.; Hanka, W.; Wylegalla, K.; van der Meijde, M.; Yuan, X. Receiver function study of the Hellenic subduction zone: imaging crustal thickness variations and the oceanic Moho of the descending African lithosphere. Geophys. J. Int. 2003, 155, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Roecker, S.; Kim, K.; Xu, Y.; Hao, T. Moho depth variations in the Taiwan orogen from joint inversion of seismic arri-val time and Bouguer gravity data. Tectonophysics 2014, 632, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Lister, G.; Kennett, B. A slab in depth: Three-dimensional geometry and evolution of the Indo-Australian plate. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, G. Slab2 - A Comprehensive Subduction Zone Geometry Model: U.S. Geological Survey data release. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, I.; Karavias, A.; Koukouvelas, I.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Parcharidis, I. The Crete Isl. (Greece) Mw6.0 Earthquake of 27 September 2021: Expecting the Unexpected. Geohazards 2022, 3, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakis, E.; Alexopoulos, J. Recognition of strike-slip faulting on the supra-detachment basin of Messara (central Crete Island) with remote sensing image interpretation techniques. In Proceedings of the 4th EARSeL Workshop on Remote Sensing and Geology, Mykonos, Greece, 24–25 May 2012; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Main tectonic features in Greece and Western Turkey. The rectangle in magenta colour contains the study area. Abbreviations-HT: Hellenic Trench; NAT: North Aegean Trough; SAVA: South Aegean Volcanic Arc. Fault traces (red lines) derived by [

9,

18].

Figure 1.

Main tectonic features in Greece and Western Turkey. The rectangle in magenta colour contains the study area. Abbreviations-HT: Hellenic Trench; NAT: North Aegean Trough; SAVA: South Aegean Volcanic Arc. Fault traces (red lines) derived by [

9,

18].

Figure 2.

Main geological elements in the area of study. The purple shaded area contains the volcanic arc. The volcanic centres are noted in red triangles. Abbreviations-HT: Hellenic Trench; SAVA: South Aegean Volcanic Arc. Fault traces (red lines) derived by [

18].

Figure 2.

Main geological elements in the area of study. The purple shaded area contains the volcanic arc. The volcanic centres are noted in red triangles. Abbreviations-HT: Hellenic Trench; SAVA: South Aegean Volcanic Arc. Fault traces (red lines) derived by [

18].

Figure 3.

Focal mechanism solution of earthquakes with ML≥5.5 during the instrumental time period [

12,

17,

19]. Fault traces (red lines) derived by [

18].

Figure 3.

Focal mechanism solution of earthquakes with ML≥5.5 during the instrumental time period [

12,

17,

19]. Fault traces (red lines) derived by [

18].

Figure 4.

Total P- (blue) and S-ray (yellow) distribution. Red triangles indicate locations of the used stations. The selected seismicity used in this work (M≥3.2) during 2018-2023 is presented by black dots.

Figure 4.

Total P- (blue) and S-ray (yellow) distribution. Red triangles indicate locations of the used stations. The selected seismicity used in this work (M≥3.2) during 2018-2023 is presented by black dots.

Figure 5.

1-D reference model derived by the first stage of the procedure. Orange line indicates P-velocity, red one indicates S-velocity.

Figure 5.

1-D reference model derived by the first stage of the procedure. Orange line indicates P-velocity, red one indicates S-velocity.

Figure 6.

Normalized ray density of the P-waves with respect to the maximum value, and nodes (red triangles) for two grids with the orientations of 0 and 45 degrees at depths of 25 km and 60 km.

Figure 6.

Normalized ray density of the P-waves with respect to the maximum value, and nodes (red triangles) for two grids with the orientations of 0 and 45 degrees at depths of 25 km and 60 km.

Figure 7.

Vertical distribution of P-rays along the extension of the profiles 1 and 2. Red dots indicate the position of the hypocentres. On the map of the upper row, there is the location of the two cross-sections.

Figure 7.

Vertical distribution of P-rays along the extension of the profiles 1 and 2. Red dots indicate the position of the hypocentres. On the map of the upper row, there is the location of the two cross-sections.

Figure 8.

(a) Initially located seismicity during the initiation of the inversion procedure (b) LOTOS relocated seismicity color-coded by depth. Red triangles represent the location of both permanent and temporary seismic stations of HUSN and G.I.-N.O.A. in the region. In this map there is the projection of the two cross-sections.

Figure 8.

(a) Initially located seismicity during the initiation of the inversion procedure (b) LOTOS relocated seismicity color-coded by depth. Red triangles represent the location of both permanent and temporary seismic stations of HUSN and G.I.-N.O.A. in the region. In this map there is the projection of the two cross-sections.

Figure 9.

Histograms of P-wave (left) and S-wave (left) travel-time residuals before (green) and after (pink) the inversion procedure.

Figure 9.

Histograms of P-wave (left) and S-wave (left) travel-time residuals before (green) and after (pink) the inversion procedure.

Figure 10.

Mislocations of the sources during the synthetic modeling shown in horizontal slices and vertical sections. The first column shows the location results using the start of the 1-D model, and the second column shows the location results of the final 3D velocity model. The black dots indicate the location of seismic events, and the red bars indicate the true locations. The figure was generated using the Golden Software Surfer.

Figure 10.

Mislocations of the sources during the synthetic modeling shown in horizontal slices and vertical sections. The first column shows the location results using the start of the 1-D model, and the second column shows the location results of the final 3D velocity model. The black dots indicate the location of seismic events, and the red bars indicate the true locations. The figure was generated using the Golden Software Surfer.

Figure 11.

Reconstruction of P-wave anomalies for the depth slices of 10, 40 and 80 km and cell size of 20 (upper panel), 40 (second panel) and 80 km (third panel).

Figure 11.

Reconstruction of P-wave anomalies for the depth slices of 10, 40 and 80 km and cell size of 20 (upper panel), 40 (second panel) and 80 km (third panel).

Figure 12.

Reconstruction of S-wave anomalies for the depth slices of 10, 40 and 80 km and cell size of 20 (upper panel), 40 (second panel) and 80 km (third panel).

Figure 12.

Reconstruction of S-wave anomalies for the depth slices of 10, 40 and 80 km and cell size of 20 (upper panel), 40 (second panel) and 80 km (third panel).

Figure 13.

Reconstruction of VP/VS ratio for the depth slices of 10, 40 and 80 km and cell size of 20 (upper panel), 40 (second panel) and 80 km (third panel).

Figure 13.

Reconstruction of VP/VS ratio for the depth slices of 10, 40 and 80 km and cell size of 20 (upper panel), 40 (second panel) and 80 km (third panel).

Figure 14.

Checkerboard tests for checking the vertical resolution. The locations of the initial synthetic anomalies are indicated with rectangles of 20x20 km2 .

Figure 14.

Checkerboard tests for checking the vertical resolution. The locations of the initial synthetic anomalies are indicated with rectangles of 20x20 km2 .

Figure 15.

Tomograms of lateral V

P, V

S (%) variations and V

P/V

S ratio at 10, 25, 40, and 80 km depth. Areas with lower resolution are masked. Black circles indicate the recorded seismicity. Toponyms and tectonic elements as in

Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 15.

Tomograms of lateral V

P, V

S (%) variations and V

P/V

S ratio at 10, 25, 40, and 80 km depth. Areas with lower resolution are masked. Black circles indicate the recorded seismicity. Toponyms and tectonic elements as in

Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 16.

Distribution of VP, VS (%) variations (left and central column) and VP/VS ratio (right) in the performed cross-sections. Areas with lower resolution are masked. Black circles indicate the recorded seismicity.

Figure 16.

Distribution of VP, VS (%) variations (left and central column) and VP/VS ratio (right) in the performed cross-sections. Areas with lower resolution are masked. Black circles indicate the recorded seismicity.

Figure 17.

Interpretation of the results of the real-data inversion of dV

P and dV

S (%) tomograms (40 and 80 km depth), V

P, V

S (%) variations (left and central column) and V

P/V

S ratio (right) in the performed cross-sections, examining the regional-scale anomalies. Areas with lower resolution are masked. Black circles indicate the recorded seismicity. Black dashed lines on the tomograms of 40 and 80 km depth (first row) show the slab contours, derived by Slab2.0 subduction zones [

58]. Abbreviations-HSZ: Hellenic Subduction Zone; SAVA: South Aegean Volcanic Arc.

Figure 17.

Interpretation of the results of the real-data inversion of dV

P and dV

S (%) tomograms (40 and 80 km depth), V

P, V

S (%) variations (left and central column) and V

P/V

S ratio (right) in the performed cross-sections, examining the regional-scale anomalies. Areas with lower resolution are masked. Black circles indicate the recorded seismicity. Black dashed lines on the tomograms of 40 and 80 km depth (first row) show the slab contours, derived by Slab2.0 subduction zones [

58]. Abbreviations-HSZ: Hellenic Subduction Zone; SAVA: South Aegean Volcanic Arc.

Table 1.

Mean residuals in L1 norm and their variance reductions during the iterative inversion procedure.

Table 1.

Mean residuals in L1 norm and their variance reductions during the iterative inversion procedure.

| Iteration |

P-residual (s) |

P-residual

reduction (%) |

S-residual (s) |

S-residual

reduction (%) |

| 1 |

0.459 |

0.00 |

0.573 |

0.00 |

| 2 |

0.331 |

27.89 |

0.349 |

39.06 |

| 3 |

0.297 |

35.25 |

0.302 |

47.27 |

| 4 |

0.283 |

38.17 |

0.286 |

50.03 |

| 5 |

0.275 |

39.97 |

0.278 |

51.38 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).