1. Introduction

Alpha lipoic acid (1,2-dithiolane-3-pentanoic acid, 1,2-dithiolane-3-valeric acid or 6,8-thioctic acid - ALA) has recently generated considerable clinical interest as biologically active agent that can be effective in relieving symptoms related to numerous diseases (diabetes, age-related cardiovascular illness, metabolic obesity etc.). ALA functions as the cofactor of oxidative decarboxylation reactions in glucose metabolism; the function that requires the disulfide group of the lipoic acid to be reduced to its dithiol form, dihydrolipoic acid, DHLA. It has been proven that the same process contributes to its efficiency as antioxidant in biological systems - ALA has specific structural properties characterized by dithiolane ring, enabling the existence of both oxidized and reduced form that together create a potent redox couple that has a standard reduction potential of −0.32 V. This makes ALA a potent direct antioxidant capable of scavenging a variety of reactive oxygen species. Furthermore, it regenerates other antioxidants, chelates redox-active transition metals, and induces the uptake (or enhances the synthesis) of endogenous low molecular weight antioxidants or antioxidant enzymes [

1]. Additionally, it has been proven to exert the wide range of anti-inflammatory activities, including the reduction of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated release of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and LPS-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [

2]. Recent investigation shows that by the combination of antioxidative and anti-inflammatory mechanisms and through regulation of glucose homeostasis, ALA could also ameliorate lipid abnormalities in hyper-lipemic and atherosclerotic environment in vivo [

3,

4].

The highest rates of clinical evidence exist for ALA's application for improving the symptoms of peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes, in dosages ranging from 600-1800 mg per day [

5]. It can positively affect lipid profile in certain groups of patients, primarily by affecting increased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels [

6]. Recent meta-analyses of clinical research also showed that supplementation with ALA for 2-48 weeks can modestly reduce body weight by 0.7-2.3 kg and body mass index (BMI) by up to 0.5 kg/m

2 when compared with placebo in overweight individuals or patients with obesity [

7]. Smaller studies indicate that ALA might be useful in the treatment of other diseases such as hemorrhoidal disease [

8], Alzheimer disease [

9] and male infertility [

10].

Recent placebo-controlled study conducted by our research group proved the efficiency of 3 -month ALA supplementation (600 mg per day) in significantly inducing the rates of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) regression and its effect has been attributed, in part, to significant anti-inflammatory effects observed in the intervention group [

11]. These results are particularly significant in the context of the general lack of therapeutic guidelines and scarce literature data on the effectiveness of nutritive intervention for patients with LSIL that might prevent progression of this condition into higher grade SIL or cervical cancer. Therefore, the main goal of this follow-up research was to investigate if 3-month supplementation with 600 mg ALA can significantly affect antioxidant status and on oxidative stress parameters of LSIL patients contributing in such manner to significant efficiency in promoting LSIL regression [

11]. Having in mind that the human antioxidant defense system resists modulation by dietary antioxidants and might depend on nutritional intake of antioxidants [

12], observed responses were discussed in relation to diet characteristics of the patients included into the clinical trial. Additionally, considering limited evidence showing that ALA might also show hypolipemic effects in certain groups of patients, we wanted to investigate the impact of supplementation on lipid parameters in metabolically healthy female patients (since such data are scarce). Obtained results would contribute to the current knowledge of possible modes of action of ALA in LSIL and its applicability as nutraceutical in LSIL diagnosed patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Clinical-Trials.gov, number NCT05485259) and was performed in accordance with the international, national, and institutional guidelines pertaining to clinical studies and biodiversity rights and it also complies with the CONSORT guidelines. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Clinical Centre Tuzla (no: 02-09/2-61-16) and the Ethics Committee of the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry (no: 251-62-03-18-23). The progress of the study and potential side effects of ALA were monitored by the independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee.

The study was designed as a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that recruited 100 participants with confirmed diagnosis of LSIL. LSIL was determined after cytological screening, colposcopic examination and targeted biopsy and histological confirmation of the diagnosis as described in detail previously [

11].

Exclusion criteria were malignant diseases, diabetes; and chronic inflammatory diseases; hysterectomy, abortion; destructive therapy of the cervix, HPV vaccination and menopause. Patients who reported regular use of dietary supplements and lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy were also not eligible for inclusion into the study. All recruited patients signed the informed consent for the inclusion in the study. Recruitment of study participants was conducted at the University Clinical Centre Tuzla in the period between January 2020 and March 2022.

Block randomization was used to distribute participants to placebo- and intervention group in 1:1 ratio. Patients were supplemented with either 600 mg per day of ALA (oral capsules containing all-rac ALA) or placebo (provided as oral capsules containing rice starch, visually identical to ALA capsules) for 3 months. Capsules of both ALA and placebo were provided by Zada Pharmaceuticals (Lukavac, Bosnia and Herzegovina).

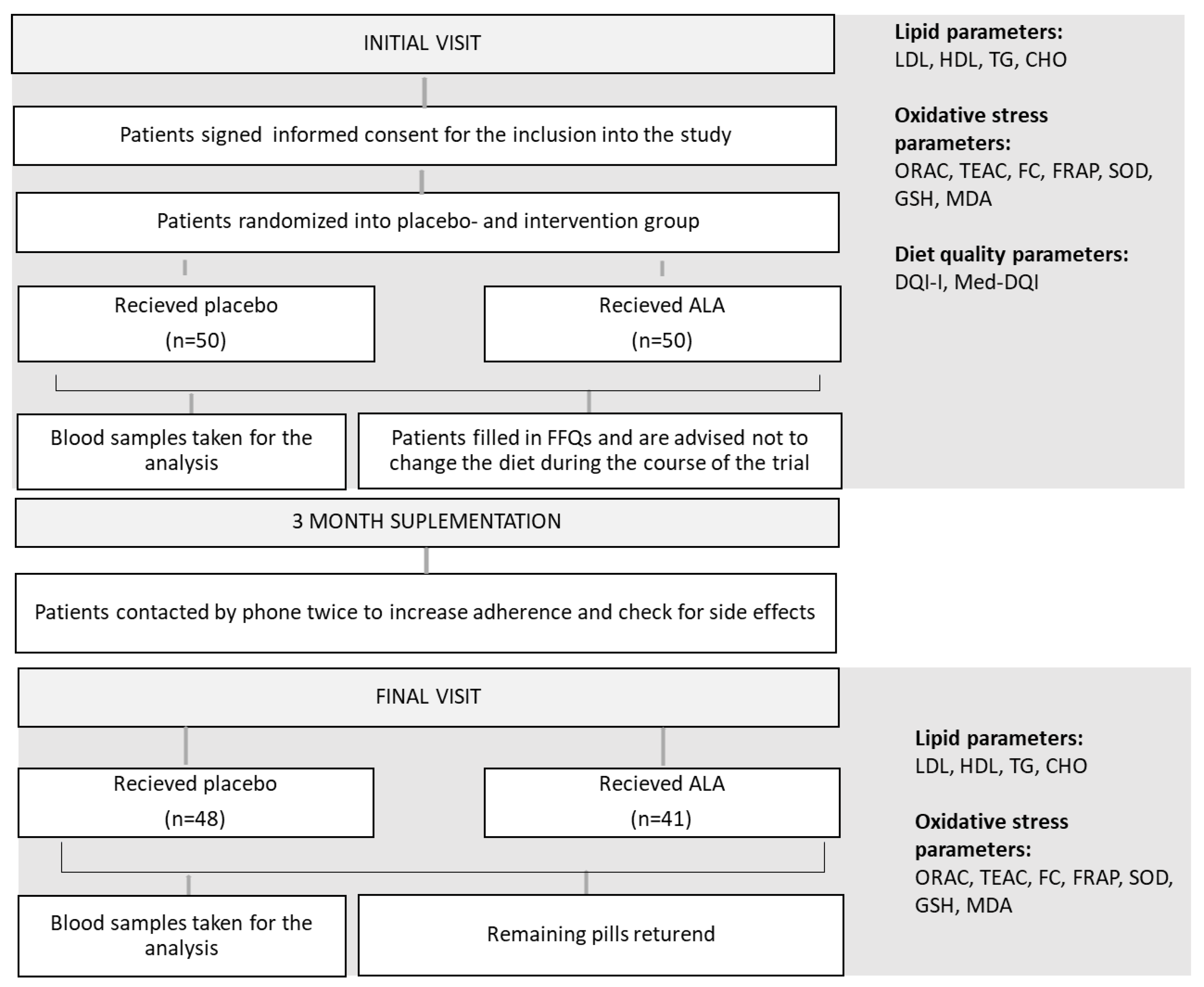

Organization and the chronological order of trial activities are schematically presented in

Figure 1.

ALA-alpha lipoic acid; LDL-low density lipoproteins; HDL-high density lipoproteins; TG-triglycerides; CHO-total cholesterol; ORAC-oxygen radical absorbance capacity; TEAC-Trolox equivalent antioxidant activity; FC-Folin-Ciocalteu reducing capacity; FRAP-ferric reducing activity; SOD-superoxide dismutase activity; GSH-reduced glutathione; MDA-malondialdehyde; DQI-I- diet quality index-international; Med-DQI- Mediterranean diet quality index; FFQ-food frequency questionary.

At the initial appointment patients filled a standardized and validated semi-quantitative food questionnaire (FFQ) [

13] with the help of trained staff to provide information on diet characteristics, use of dietary supplements, smoking, and physical activity. During the supplementation period participants were contacted twice by telephone by a research team member to check possible adverse effects and to improve the adherence. 3 months after entry participants were invited to the follow-up appointment.

At both appointments (initial and 3-months appointment) blood samples were taken from the patients` cubital vein, by the standard procedure. Biochemical parameters total cholesterol (CHO), LDL, high density lipoproteins (HDL), triglycerides (TG) and oxidative status indicators (oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC); Trolox equivalent antioxidant activity (TEAC); Folin-Ciocalteu reducing capacity (FC); ferric reducing activity (FRAP); superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, reduced glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels) were determined in collected blood samples. Fasting venous blood was collected into tube with serum separator gel at baseline and 90th day (BD Vacutainer, Becton Dickenson, NJ, USA). The serum was separated by centrifugation and multiple aliquots of each sample were either analyzed immediately (biochemical parameters) or stored at -80 ºC for future analysis (oxidative stress parameters).

The capsules remaining after the 3-month supplementation period were to be returned for the adherence assessment. Patients were advised not to change their diet and level of physical activity during the study.

2.2. Assessment of Biochemical Parameters

Biochemical parameters (CHO, LDL, HDL, and TG) were determined by standard laboratory procedures on Architect ci8200 integrated system, using original reagents (Abbot Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA).

2.3. Assessment of Oxidative Status Parameters

2.3.1. Assessment of Total Antioxidant Capacity of Serum

Adequately diluted blood serums were used for all analyses. Spectrofluorometric and spectrophotometric measurements were conducted in 96-well plates using Victor X3 plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). ORAC assay was conducted according to the method of Ou and co-workers [

14] and it measures free radical oxidation of a fluorescent probe through the change in its fluorescence intensity. It is run to completion and the dynamic change in fluorescence of the probe over time is accounted for by calculating the area under the fluorescence decay curve (AUC). It compares the integral of the fluorescence quenching induced by sample/standard/blank solution and considers both, inhibition degree and inhibition time, which is considered a methodological improvement. Fluorescence measurements were made at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. Trolox was used for designing calibration curve by plotting AUC with corresponding Trolox concentrations. Results were expressed as mgL

-1 of Trolox equivalents (TE). TEAC assay was performed according to the procedure of Re and co-workers [

15] and it measures the decrease in the absorbance of a preformed ABTS

∙+ solution in the presence of an antioxidant compound. The ABTS

∙+ chromophore (blue/green) is generated through the reaction between ABTS and potassium persulfate. The decolorization of ABTS

∙+, in the presence of an antioxidant, can be measured at 734 nm and results were expressed as mgL

-1 TE. FC reducing capacity of serum was determined according to the method of Ainswort and Gillespie [

16] and it relies on the transfer of electrons in alkaline medium from phenolic compounds to phosphomolybdic/phosphotungstic acid complexes, which are determined spectroscopically at 765 nm. Results were expressed as mgL

-1 of gallic acid equivalents (GAE). FRAP method [

17] measures ferric to ferrous ion reduction in the presence of antioxidants at low pH causing formation of ferrous-tripyridyl-triazine complex that can be measured spectrophotometrically at 593 nm. Obtained results are expressed as µmolL

-1 TE.

2.3.2. Assessment of the Activity of Endogenous Antioxidant System

GSH was determined by the modified method of Machado and Soares [

18] that measures the formation of the fluorescent complex between monochlorbimane and GSH that can be monitored at excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. Results were expressed as µmolL

-1. SOD activity was measured by using 19160 SOD determination kit (Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, USA). The method measures inhibition activity of SOD that can be monitored as a decrease of absorbance of a water-soluble formazan dye formed in the presence of the superoxide anion at 440 nm. Relative SOD activity is presented as % of absorbance inhibition (measured at 440 nm).

2.3.3. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation

The determination of MDA was based on the method by [

19] with a few modifications. The method is based on the reaction of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and MDA. MDA under acidic conditions reacts with TBA in a ratio of 1:2, whereby a red pigment is formed, the absorbance of which is measured at 532 nm. 1,1,3,3 tetraethoxypropane has been used as the standard for the preparation of calibration curve and obtained results were expressed as µmolL

-1.

2.4. Analysis of Dietary Characteristics and Calculation of Diet Quality Indexes

Semiquantitative FFQ used for the assessment of dietary characteristics was designed as 192-item questionnaire with one month as reference period of intake. It included questions on the frequency of consumption and the approximate amount of 100 dietary items listed, and additional queries about supplementation used and eating habits. The questionnaire was constructed as a modification of previously published questionnaire [

20] regarding serving sizes and the national specificity of foods. The participants filled out the questionnaire under the supervision of a researcher. Based on the frequency and serving size reported in the FFQ, average daily food intake in grams/serving sizes was calculated for each participant. Dietary intake for selected nutrients was calculated using national food composition tables [

21] and serving sizes according to USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 [

22].

The quality of dietary habits of participants was estimated by the calculation of specific indexes: Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) that serves as a composite measure of general diet quality created to evaluate healthfulness of diet; and an index evaluating the compatibility of dietary habits to the concepts of Mediterranean diet: Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (Med-DQI). For the DQI-I the defined score range is 0-100, where 100 indicates the highest quality of nutrition. DQI-I focuses on four quality characteristics of a diet: variety (overall food group variety and within-group variety for protein), adequacy (vegetable-, fruit- and grain group; dietary fibre, protein, Fe, Ca and vitamin C), moderation (total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium and empty calorie foods) and overall balance (macronutrient ratio and fatty acid ratio) [

23].

For the calculation of this index olive oil was added as particular category (with a score increasing with a lower intake, as opposed to cholesterol or saturated fat intake). Protein-intake category is divided into meat- and fish intake (with intake of fish having opposite gradient to meat). For the Med-DQI every nutrient or food group is assigned three scores (0, 1 and 2) depending on either recommended guidelines or (where there was no specific recommendation for item) by dividing the population’s consumption into tertials. Total Med-DQI for each subject is calculated by summing all scores. The best Med-DQI has a score of 0. Scores between 1 and 4 were considered as good; scores between 5 and 7 as medium to good; scores between 8 and 10 as under medium to poor; and scores between 11 and 13 as poor [

24,

25].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done using the GraphPad Prism 8.4.3 (GraphPad Software LLC, San Diego CA) and MedCalc statistical software ver.14.8.1.0. (MedCalc Software Lcd., Ostend, Belgium). For the analysis of numerical variables nonparametric statistical tests were used, due to low number of patients in placebo or treated group (n≤50). Obtained results were presented as medians and interquartile range. To identify between-group differences Wilcoxon’s paired rank test was used. Comparison of binary outcomes was made by 2x2 tabulation and a risk ratio (RR), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values were calculated.

3. Results

3.1. The Baseline Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 100 participants were incuded to the study and were allocated to placebo and intervention group in 1:1 ratio. A total of 41 participant in intervention group and 48 participants in placebo group finished the study; the remaining patients (n=11) reported that they didn’t finish the study due to personal reasons.

The baseline characteristics of the study groups are presented in

Table 1. Different lifestyle and selected diet characteristics that might have an impact on antioxidant status of the participants were compared between two arms. Complete list of diet characteristic of study participants assessed by FFQ analysis are presented in

Table S1.

As presented in

Table 1, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics or diet between placebo- and intervention group. The age of participants, and the percentage of smokers in the two study groups were similar (p=0.082; p=0.332, respectively). The percentage of smokers in the placebo and the intervention group was 29.2% and 19.5%, respectively). Compliance was assessed based on the number of returned unused capsules after a 3-month supplementation period and was high in both groups (80.6% and 84.4% respectively).

Dietary characteristics relevant for antioxidant status and lipid profile were compared between the two groups of patients: intake of fruit and vegetables, vitamin C, vitamin E and carotenoids (as antioxidant. protective factors); and intake of energy, meat, red meat, animal protein, saturated fat, unsaturated fat, and cholesterol (as factors that could possibly contribute to oxidative stress and dyslipidemia). General compliance of participants dietary habits with general dietary guidelines or principles of Mediterranean diet (quantified and expressed as DQI-I and Med-DQI respectively) has been compared between the groups. The analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences between placebo- and intervention group regarding any of the observed diet characteristics. Additional details on the intake of nutrients of study participants are presented in

Table S1.

3.2. Impact of ALA Supplementation on Oxidative- and Lipid Status Parameters

Impact of ALA supplementation on oxidative status parameters has been investigated previously in diabetic patients [

26,

27], patients with multiple sclerosis [

28] and non-alcocholic liver disease [

29] and patients on hemodialysis [

30,

31]. Obtained results varied significantly, depending on oxidative stress marker and the significance of the observed effect (some studies showed significant impact of supplementation, others didn’t).

This investigation focused on serum total antioxidant capacity (TEAC. ORAC. FRAP and FC reducing potential), activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD), status of endogenous antioxidants (GSH) and lipid peroxidation markers (MDA) of patients with LSIL after 3-month of ALA supplementation. Values were compared between the placebo and the treated group at two time-points (initial visit and 3-month follow-up visit) and are presented in

Table 2. The differences between the values obtained in the placebo and the treated group at the initial and the 3-month follow-up visit are presented in

Table 3.

As presented in

Table 2. at the initial measurement there were no significant differences between medians of MDA levels (p=0.151), FRAP (p=0.381), SOD (p=0.180), ORAC (p=0.488), and GSH (p=0.389) in the placebo- and the intervention group; TEAC was significantly higher (p=0.048) and FC reducing capacity was significantly lower in intervention group (p=0.005). After the 3 months of supplementation the situation remained unchanged except for GSH levels that were now significantly lower in the intervention group compared to placebo (p= 0.050). However, the apparent decrease of GSH values that was observed in the ALA-supplemented group after 3-months of supplementation was found to be statistically insignificant (p=0.411). Moreover, as presented in

Table 3, none of the monitored oxidative status parameters was significantly changed neither in placebo nor in the intervention group.

Diet characteristics can play a significant role in modulating the overall effectiveness of antioxidant supplements [

32] by influencing the baseline host antioxidant status or through specific nutrient interactions - influencing the bioavailability of supplemental antioxidants or resulting in synergistic/antagonistic reactions. Therefore, subgroup analysis was conducted to compare the ALA effectiveness in subgroups of patients with high (>11) and low (<7) Med-DQI (indicating low and high degree of adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns). Med-DQI was chosen because it quantifies the levels of adherence to Mediterranean diet and dietary diversity which are known to contribute to lower antioxidant and inflammation biomarkers [33-35].

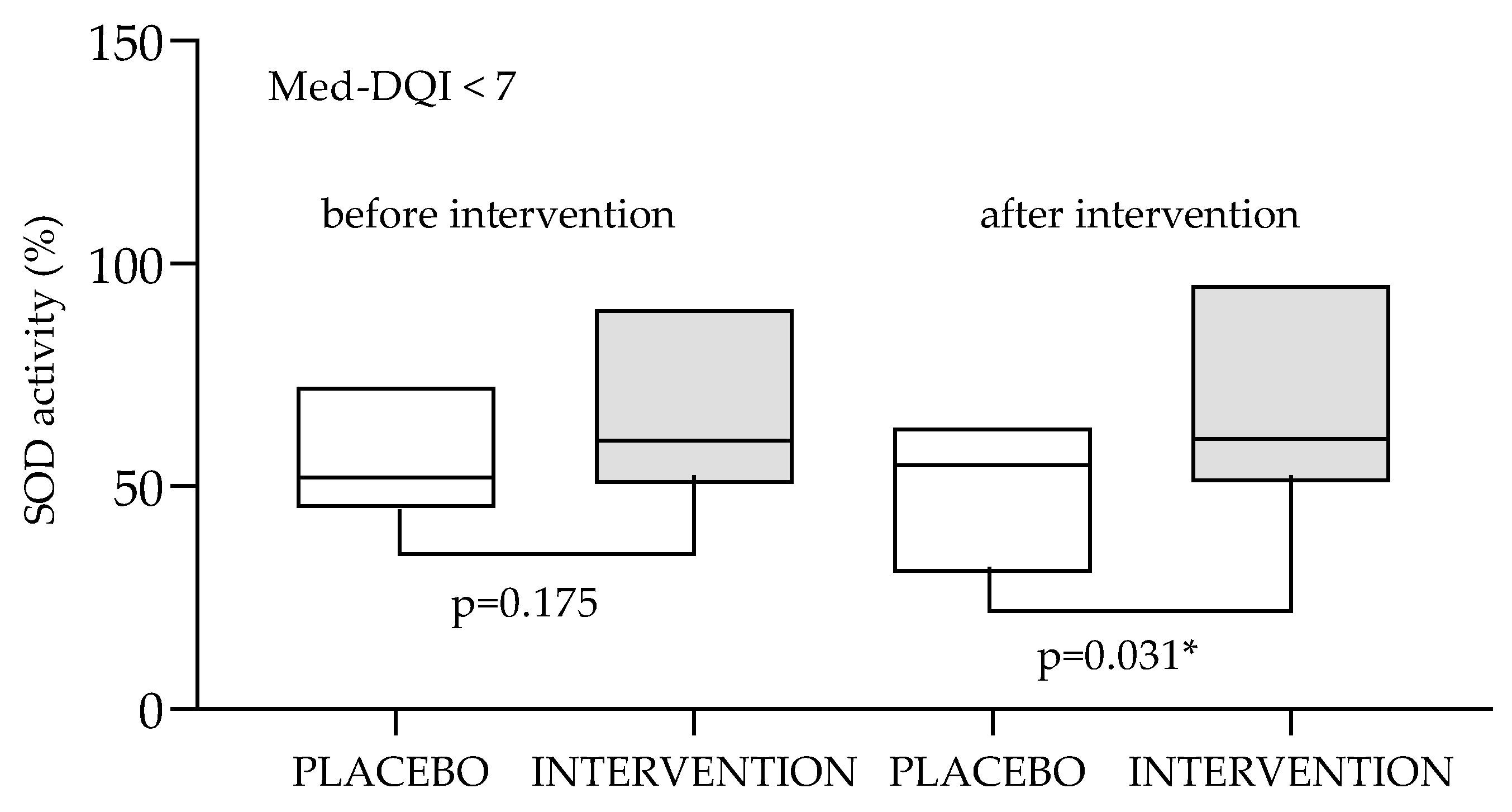

Subgroup analysis showed that the effects of antioxidant supplementation on oxidative status biomarkers might be significantly affected by patient’s dietary characteristics. As presented in

Figure 2, in the subgroup of patients with higher level of compatibility with Mediterranean dietary patterns (Med-DQI<7) supplementation with ALA showed positive effects on SOD activity (prevented the decrease of SOD activity that was observed in the placebo group. This was not observed in the in the subgroup with low level of compatibility with Mediterranean dietary patterns (Med-DQI>11).

Data are presented as medians (min to max values). Tested by Wilcoxon’s paired rank test. * observed difference is statistically significant (p<0.05). SOD-superoxide dismutase; Med-DQI- Mediterranean Diet Quality Index.

Impact of ALA on lipid parameters has been investigated to some extent with most available studies focused on patients with metabolic diseases showing that ALA might exert mild lipid lowering properties [

6]. Considering ALA could provide clinically significant benefit in other indications not primarily associated with disturbances of lipid profile (such as LSIL), it is of great importance to investigate its effect on lipid parameters in metabolically healthy patients. To investigate the effect of ALA supplementation on lipid parameters LDL, HDL, TG and CHO values were investigated (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

As presented in

Table 2, initially there were no significant differences in lipid parameters between placebo and intervention group. However, after 3- month supplementation LDL levels in intervention group were significantly higher compared to the intervention group (p=0.033).

Table 3 shows that during the 3-month supplementation period CHO and LDL levels of the placebo group remained unchanged. while in the intervention group they increased from 5.19 to 5.69 (p=0.001) and from 2.89 to 3.46 (p=0.006). Obtained results are not consistent with the results of other authors who showed that ALA either decreased LDL or showed no significant effect [

6]; however, those data were mostly obtained in studies focusing on patients with metabolic diseases and hyperlipidemia.

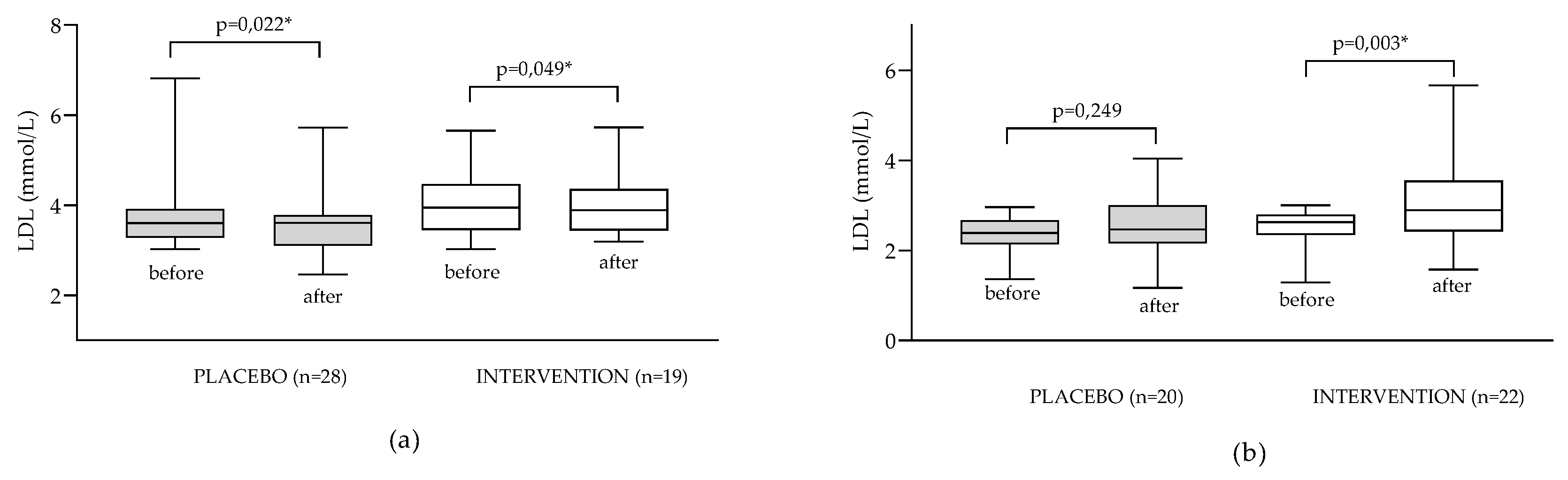

To test our hypothesis that ALA could have different effects on LDL levels depending on the initial lipid status, we conducted subgroup analysis focusing specifically on participants with hypercholesterolemia (LDL>3 mmolL

-1) and specifically on normolipemic patients (LDL≤3.00 mmolL

-1). Obtained results are presented in

Figure 3.

Data are presented as medians (min to max values). Results are expressed as medians (min to max values). Tested by Wilcoxon’s paired rank test. *difference is statistically significant (p<0.05).

In patients with hyperlipidemia supplementation with ALA resulted in very small but statistically significant decrease of LDL values (median decreased from 3.95 to 3.89 mmolL

-1; p=0.049); however more pronounced effect has been observed in placebo group (decrease from 3.76 to 3.54 mmolL

-1; p=0.022). This might be explained by possible positive modification of dietary and lifestyle habits of the patients upon recruitment into the dietary clinical study (despite clear instruction that dietary habits and lifestyle shouldn’t be changed during the study), which has been noted in the literature [

36]. In the subgroup of patients with normal LDL levels significant increase of LDL levels was observed in the intervention but not in the placebo group (median increased from 4.01 to 4.07 mmolL

-1; p=0.003) which confirms our hypothesis that effect of ALA supplementation on lipid status might be affected by the initial lipid status of the patient.

4. Discussion

4.1. Dietary Characteristics of Participants

Patient response to antioxidant supplementation is in great part conditioned by his general dietary habits and nutritional intake of antioxidants. For this purpose, it was important to investigate if dietary habits of participants included in the study are comparable to the general population. As presented in

Table S1, participants’ diet was characterized with high median energy intake (3160 kcal), high medians of fat- and saturated fat intake (186 g and 62.2 g, respectively), low medians of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) / saturated fatty acid (SF) and monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA)/SF ratio (0.85 and 0.93 respectively). The intake of red meat was in line with recommendations (2.92 portions per week) but intake of fish, fruits and vegetables was significantly lower, particularly for fish (0.54. 3.54 and 3.71 servings per week). Generally, it can be concluded that participants of the study consumed Western-type diet characterized with low DQI-I and Med-DQI (63.5 (out of 100) and 9 (categorized as medium to poor), respectively). This was reflected poorly on the intake of vitamins and minerals. While the intake of vitamin C, B-complex (except folate), vitamin E and vitamin A was above recommendations in >75% of patients, intake of vitamin D and folate was problematic and adequate intake was observed in only 3% and 38% of study participants, respectively. Among minerals, intake of Fe and Ca was particularly problematic and only a minority of patients had adequate intake (35% and 42% respectively). Intake of sodium was higher than recommended in 28% of participants and intake of potassium was lower than recommended in 70% of participants.

Due to the lack of precise data for nutritional habits in Bosnia and Herzegovina or surrounding countries, it was hard to assess if dietary habits of study participants are comparable to average habits of general population. Obtained data were therefore compared to dietary habits of women in eastern and central European countries investigated previously in the frameworks of HAPIEE study [

37]. General dietary characteristics regarding nutritional quality, food group-, energy- and average micronutrient intakes were comparable; intake of fat, saturated fat and dietary fibers was somewhat higher in our study.

4.2. Impact of ALA Supplementation on Oxidative Status Parameters

Even though ALA has been recognized primarily as potent antioxidant that exerts its action through different various direct and indirect mechanisms [

1], our results showed that its application did not result in the significant change of any of the observed oxidative status parameters.

Clinical data obtained by other authors are scarce and inconsistent. Derosa and co-authors [

26] showed that supplement containing 600 mg of ALA significantly reduced MDA levels and increased activities of SOD and GSH levels in diabetic patients after 3 months of supplementation. They observed a decrease of inflammation markers in the intervention group which is consistent with our previously published results [

11]. Khalili and co-authors [

27] found that SOD activity, glutathione peroxidase activity, and MDA levels were not affected by consumption of 1200 mg of ALA for 3 months in patients with multiple sclerosis; however, TEAC values were positively affected. In patients with non-alcocholic liver disease 3-month supplementation with 1200 mg of ALA significantly decreased MDA levels and increased total antioxidant capacity of serum while other oxidative status parameters remained unaffected by ALA supplementation [

28]. In patients with renal disease on hemodialysis supplementation with ALA did not affect oxidative status parameters [

30,

31]. In the pilot study by Huang and Gitelman [

27], ALA was not an effective treatment for decreasing oxidative damage in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Inconsistencies in results obtained by various authors can be explained, in part, by differences in baseline characteristics of participants - pathologies, metabolic status, age, sex, supplementation protocols (600 mg vs 1200 mg) or composition of tested supplements. For example, Derosa and co-workers [

26] tested multicomponent formulation; none of studies informed about ALA isomer ratios in tested formulations etc.

It is important to emphasize that even though diet plays a significant role in modulating the overall effectiveness of antioxidant supplements [

32], none of the above-mentioned studies investigated the diet characteristics of the participants and took those data into account when discussing study results. It was our assumption that the most important aspect of diet to be associated with the patient’s response to antioxidant supplementation would be dietary intake of antioxidants and the diet quality index that primarily considers this aspect of nutrition is Med-DQI. Results of the conducted subgroup analysis based on Med-DQI showed that supplementation with ALA positively affected SOD activity (

Figure 2). This observation can be explained by the fact that ALA increases the gene expression of the primary antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) which can be monitored as the increase of the activity in the serum [

38]. In our study the effect was visible only in the subgroup of patients with a high degree of adherence to Mediterranean type diet. A possible explanation of obtained results is that in the state of higher oxidative stress increased SOD expression does not result in increased serum activity because SOD is being extensively used in cellular oxidative reactions. Contrary to that, high dietary intake of other antioxidants that reduce the formation of ROS (including superoxide anion) decreases the depletion of SOD, so that the effect of ALA on SOD serum activity is visible and significant.

4.3. Impact of ALA Supplementation on Lipid Parameters

Obtained results pointing out mild hyperlipidemic effect of ALA supplementation are partially inconsistent with the results obtained by other authors. Lipid-reducing properties of ALA have been proven in numerous studies but due to heterogenicity of studied populations and dosing regimens (400-1200 mg/day) it is hard to estimate its actual clinical effectiveness in hypercholesterolemia Meta-analysis by Haghighatdoost. and Hariri [

6] showed that ALA may significantly decrease total CHO, LDL and TG levels, but that the results obtained so far are contradictory and more research is needed to draw more specific conclusions. A more recent meta-analysis [

39] found that the observed effects of ALA in diabetic patients were not clinically significant.

As mentioned previously, most of the available research has been focused on patients with metabolic diseases with pronounced dyslipidemia while our study focused on metabolically healthy patients which might have contributed to observed lack of hypocholesterolemic effect of ALA. Conducted subgroup analysis (

Figure 3) revealed that the effect of ALA supplementation in patients with hyperlipidemia causes slight, but statistically significant, decrease in LDL levels which is consistent to results of other studies [

6]. On the contrary, supplementation of patients with normal LDL levels led to significantly increased LDL levels which has not been shown before (to our knowledge).

The explanation of observed effects is related to the mechanism of ALA´s direct lipid-lowering action which has not been totally elucidated by now. The mechanism is thought to be multifactorial - ALA is probably capable of initiating LDL receptor synthesis in the liver which in turn increases the uptake of cholesterol back to the hepatic system and increase synthesis of apoprotein A component [

40]. Possible impact on lipoprotein lipase activity and inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase have also been suggested [

41,

42]. It is possible to hypothesize that the lipid-lowering effects of ALA can only be manifested in patients with a certain level of disfunction regarding the lipid metabolism and that it depends on the initial lipid status of the patients. This hypothesis is partially backed up by the conclusions of several clinical studies conducted in normolypemic patients or patients with lower degree dyslipidemia. For example, Gosselin and co-authors [

43] showed that ALA is not effective in modulating serum lipids in prediabetic patients and Iannuzzo and co-authors [44] showed that ALA had no effect on body weight and blood lipid levels in (mainly normolypemic) schizophrenic subjects. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the exact mechanisms of lipid-lowering effects of ALA and the importance of initial lipid status and dosing regimen on the clinical effects of supplementation.

5. Conclusions

The results of conducted trial demonstrate that monitored oxidative stress biomarkers of patients with LSIL diagnosis and adherence to typical western-style diet are not significantly affected by 3-month supplementation with 600 mg of ALA. Subgroup analysis showed that the impact of ALA supplementation on oxidative status parameters might be significantly affected by diet quality of the participants, particularly by the degree of compliance to Mediterranean dietary pattern. Unexpectedly, ALA supplementation resulted with small but statistically significant increase of LDL and CHO levels indicating that lipid-lowering effect of ALA observed in some studies might depend on the initial lipid status of the participants (which has been confirmed by post-hoc subgroup analysis.

Obtained results contribute significantly to the current knowledge on the possibilities and limitations of utilization of ALA as dietary supplement and provide additional insight in the possible mechanisms of actions. Larger studies are necessary, that will enable more comprehensive investigation of significant confounding factors. Additionally, having in mind relatively low and variable bioavailability of ALA, impact of supplementation of ALA levels/status should be monitored and considered when interpreting obtained data.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org. Table S1: Diet characteristics of study participants as assessed by semiquantitative food frequency questionary (FFQ).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization A.D; I.R.S; Z.K. and D.V.C.; investigation and methodology D.V.C.; A.D; N.G.; K.R.; D.S; L.V.; data analysis and interpretation M.G.; D.V.C.; writing—original draft preparation D.V.C.; writing—review and editing K.R.; M.G.; L.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the FarmInova project [grant number KK.01.1.1.02.0021] funded by the European Regional Development Fund. The work of doctoral student Nikolina Golub was fully supported by the “Young researchers’ career development project—training of doctoral students” of the Croatian Science Foundation [grant number HRZZ-DOK-2021-02-6801].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the by the Ethics Committee of the University of Zagreb. Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry (no: 251-62-03-18-23; 19.04.2018.) and the Ethics Committee of the University Clinical Centre Tuzla (no: 02-09/2-61-16; 19.10.2016.). The trial is registered at Clini-calTrials.gov (Clinical-Trials.gov. number NCT05485259). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author. [D.V.C]. upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to Zada Pharmaceuticals d.o.o. (Lukavac. Bosnia and Herzegovina) for the donation of alpha lipoic acid (ALA) and formulation of placebo. The authors would like to thank Mrs. Gordana Blažinić for the technical assistance during the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shay. K.P.; Moreau. R.F.; Smith. E.J.; Smith. A.R.; Hagen. T.M. Alpha-lipoic acid as a dietary supplement: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. BBA 2009. 1790(10) 1149-1160. [CrossRef]

- Li. G.; Fu. J.; Zhao. Y.; Ji. K.; Luan. T.; Zang. B. Alpha-lipoic acid exerts anti-inflammatory effects on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated rat mesangial cells via inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway. Inflamm 2015. 38 510-519. [CrossRef]

- Zhang. Y.; Han. P.; Wu. N.; He. B.; Lu. Y.; Li. S.; Liu. Y.; Zhao. S.; Liu. L.; Li. Y. Amelioration of lipid abnormalities by α-lipoic acid through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. Obes 2011. 19(8) 1647-1653. [CrossRef]

- Theodosis-Nobelos. P.; Papagiouvannis. G.; Tziona. P.; Rekka. E.A. Lipoic acid. Kinetics and pluripotent biological properties and derivatives. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021. 48(9) 6539–6550. [CrossRef]

- Abubaker. S.A.; Alonazy. A.M.; Abdulrahman. A. Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid in the Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathy: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022. 14(6) e25750. [CrossRef]

- Haghighatdoost. F.; Hariri. M. Does alpha-lipoic acid affect lipid profile? A meta-analysis and systematic review on randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019. 847(1) 10. [CrossRef]

- Namazi. N.; Larijani. B.; Azadbakht. L. Alpha-lipoic acid supplement in obesity treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2018. 37(2) 419-428. [CrossRef]

- Šabanović. M.; Jašić. M.; Odobašić. O.; Spasenska Aleksovska. E.; Pavljašević. S.; Bajraktarević. A.; Vitali Čepo. D. Alpha-lipoic Acid Reduces Symptoms and Inflammation Biomarkers in Patients with Chronic Haemorrhoidal Illness. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2019. 1 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Hager. K.; Kenklies. M.; McAfoose. J.; Engel. J.; Münch. G. Alpha-lipoic acid as a new treatment option for Alzheimer's disease--a 48 months follow-up analysis. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2007. 72 189-193. [CrossRef]

- Dong. L.; Yang. F.; Li. J.; Li. Y.; Yu. X.; Zhang. X. Effect of oral alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) on sperm parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Basic Clin. Androl. 2022. 32(1) 23. [CrossRef]

- Divković. A.; Radić. K.; Sabitović. D.; Golub. N.; Rajković. M.G.; Samarin. I.R.; Karasalihović. Z.; Šerak. A.; Trnačević. E.; Turčić. P.; Butorac. D.; Vitali Čepo. D. Effect of Alpha-Lipoic Acid Supplementation on Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions—Double-Blind. Randomized. Placebo-Controlled Trial. Healthcare MDPI 2022. 10(12) 2434. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell. B. The antioxidant paradox: less paradoxical now?. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013. 75(3) 637-644. [CrossRef]

- Babić. D.; Sindik. J.; Missoni. S. Development and validation of a self-administered food frequency questionnaire to assess habitual dietary intake and quality of diet in healthy adults in the Republic of Croatia. Coll. Antropol. 2014. 38(3) 1017-1026.

- Ou. B.; Chang. T.; Huang. D.; Prior. R.L. Determination of total antioxidant capacity by oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) using fluorescein as the fluorescence probe: First action 2012.23. J. AOAC Int. 2013. 96(6) 1372-1376. https://dou.org/10.5740/jaoacint.13-175.

- Re. R.; Pellegrini. N.; Proteggente. A.; Pannala. A.; Yang. M.; Rice-Evans. C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999. 26 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- Ainswort. E.; Gillespie. K. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Prot. 2 2007. 875–877. [CrossRef]

- Benzie. I.F.; Strain. J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996. 239(1). [CrossRef]

- Machado. M.D.; Soares. E.V. Assessment of cellular reduced glutathione content in Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata using monochlorobimane. J. Appl. Phycol. 2012. 24 1509-1516. [CrossRef]

- Drury. J.A.; Nycyk. J.A.; Cooke. R.W. Comparison of urinary and plasma malondialdehyde in preterm infants. Clin. Chim. Acta 1997. 263(2) 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaar. L.; Yuan. C.; Rosner. B.; Dean. S.B.; Ivey. K.L.; Clowry. C.M.; Sampson. L.A.; Barnett. J.B.; Rood. J.; Harnack. L.J.; Block. J.; Manson. J.E.; Stampfer. M.J.; Willett. W.C.; Rimm. E.B. Reproducibility and Validity of a Semiquantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire in Men Assessed by Multiple Methods. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021. 190(6) 1122-1132. [CrossRef]

- Kaić-Rak. A.; Antonić. K. Tablice o sastavu namirnica i pića. Zavod za zaštitu zdravlja SR Hrvatske. Zagreb. 1990.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 9th ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020; pp. 2020-2025.

- Kim. S.; Haines. P.S.; Siega-Riz. A.M.; Popkin. B.M. The Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) provides an effective tool for cross-national comparison of diet quality as illustrated by China and the United State. J Nutr 2003. 133(11) 3476-3484. [CrossRef]

- Gerber. M. Qualitative methods to evaluate Mediterranean diet in adults. Public Health Nutr. 2006. 9(1A) 147-151. [CrossRef]

- Baldini. M.; Pasqui. F.; Bordoni. A.; Maranesi. M. Is the Mediterranean lifestyle still a reality? Evaluation of food consumption and energy expenditure in Italian and Spanish university students. Public Health Nutr. 2009. 12(2) 148-155. [CrossRef]

- Derosa. G.; D’Angelo. A.; Romano. D.; Maffioli. P. A Clinical Trial about a Food Supplement Containing α-Lipoic Acid on Oxidative Stress Markers in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016. 17(11) 1802. [CrossRef]

- Huang. E.A.; Gitelman. S.E. The effect of oral alpha-lipoic acid on oxidative stress in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatric Diabetes 2008. 9(3Pt2) 69-73. [CrossRef]

- Khalili. M.; Eghtesadi. S.; Mirshafiey. A.; Eskandari. G.; Sanoobar. M.; Sahraian. M.A.; Motevalian. A.; Norouzi. A. Moftakhar. S.; Azimi. A. Effect of lipoic acid consumption on oxidative stress among multiple sclerosis patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2014. 17(1) 16-20. [CrossRef]

- Farshad. A.; Soudabeh. H.S.; Sonya. H.A.; Elnaz. V.M.; Mehrangiz. E.M. Effects of Alpha-Lipoic Acid Supplementation on Oxidative Stress Status in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized. Double Blind. Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. IRCMJ 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi. A.; Mazooji. N.; Roozbeh. J.; Mazloom Z.; Hasanzade. J. Effect of alpha-lipoic acid and vitamin E supplementation on oxidative stress. inflammation. and malnutrition in hemodialysis patients. IJKD 2013. 7(6) 461-467.

- Khabbazi. T.; Mahdavi. R.; Safa. J.; Pour-Abdollahi. P. Effects of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on inflammation. oxidative stress. and serum lipid profile levels in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2012. 22(2) 244-250. [CrossRef]

- Draeger. C.L.; Naves. A.; Marques. N.; Baptistella. A.B.; Carnauba. R.A.; Paschoal. V.; Nicastro. H. Controversies of antioxidant vitamins supplementation in exercise: ergogenic or ergolytic effects in humans?. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014. 11(1) 4. [CrossRef]

- Bettermann. E.L.; Hartman. T.J.; Easley. K.A.; Ferranti. E.P.; Jones. D.P.; Quyyumi. A.A.; Vaccarino. V.; Ziegler. T.R.; Alvarez. J.A. Higher Mediterranean diet quality scores and lower body mass index are associated with a less-oxidized plasma glutathione and cysteine redox status in adults. J Nutr 2018. 148(2) 245-253. [CrossRef]

- Kim. J.Y.; Yang. Y.J.; Yang. Y.K.; Oh. S.Y.; Hong. Y.C.; Lee. E.K.; Kwon. O. Diet quality scores and oxidative stress in Korean adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011. 65 1271–1278. [CrossRef]

- Fung. T.T.; McCullough. M.L.; Newby. P.; Manson. J.E.; Meigs. J.B.; Rifai. N.; Willett. W.C.; Hu. F.B. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. AJCN 2005. 82(1) 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran. P.; Bahadoran. Z.; Gaeini. Z. Common limitations and challenges of dietary clinical trials for translation into clinical practices. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2021. 19(3).

- Boylan. S.; Welch. A.; Pikhart. H.; Malyutina. S.; Pajak. A.; Kubinova. R.; Bragina. O.; Simonova. G.; Stepaniak. U.; Januszewska. A.G.; Milla. L.; Peasey. A.; Marmot. M.; Bobak. M. (2009). Dietary habits in three Central and Eastern European countries: the HAPIEE study. BMC public health 2009. 9(1) 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Fayez. A.M.; Zakaria. S.; Moustafa. D. Alpha lipoic acid exerts antioxidant effect via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation and suppresses hepatic stellate cells activation induced by methotrexate in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018. 105 428-433. [CrossRef]

- Jibril. A.T.; Jayedi. A.; Shab-Bidar. S. Efficacy and safety of oral alpha-lipoic acid supplementation for type 2 diabetes management: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized trials. Endocr. Connect. 2022. 11(10) e220322. [CrossRef]

- Marangon. K.; Devaraj. S.; Tirosh. O.; Packer. L.; Jialal. I. Comparison of the effect of alpha-lipoic acid and alpha-tocopherol supplementation on measures of oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999. 27(9-10) 1114–1121. [CrossRef]

- Tomonaga. I.; Jingyan. L.; Shuji. K.; Tomonari. K.; Xiaofei. W.; Huijun. S.; Masatoshi. M.; Hisataka. S.; Teruo. W.; Nobuhiro. Y.; Jianglin. F. Macrophage-derived lipoprotein lipase increases aortic atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed Tg rabbits. Atherosclerosis 2005. 179(1) 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Matsugo. S.; Yan. L.J.; Konishi. T. An antioxidant. inhibits protein oxidative modification of human low density lipoprotein and reduces plasma cholesterol levels by the inhibition of HMG-CoA reductas.. BBRC 1997. 243 819-824.

- Gosselin. L.E.; Chrapowitzky. L.; Rideout. T.C. Metabolic effects of α-lipoic acid supplementation in pre-diabetics: a randomized. placebo-controlled pilot study. Food Funct. 2019. 10(9) 5732-5738. https://doi.org10. 1039.

- Iannuzzo. F.; Basile. G.A.; Campolo. D.; Genovese. G.; Pandolfo. G.; Giunta.L.; Ruggeri. D.; Di Benedetto. A.; Bruno. A. Metabolic and clinical effect of alpha-lipoic acid administration in schizophrenic subjects stabilized with atypical antipsychotics: A 12-week. open-label. uncontrolled study. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2022. 3 100116. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).