Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Wild-type strains | Carbon source | Cultivation strategy | Titer | References |

| Y. lipolytica A-15 | 100 g/l glycerol |

Batch bioreactor | 28 g/l | [18] |

| Y. lipolytica A-3 | 150 g/l glycerol | Batch bioreactor | 25,3 g/l | [19] |

| Y. lipolytica A-6 | 150 g/l glycerol | Batch bioreactor | 32 g/l | [19] |

| Y. divulgata CBS11013 | 100 g/l glycerol | Batch bioreactor | 35,4 g/l | [11] |

| Mutant strains | Carbon source | Cultivation strategy | Titer | References |

| Y. lipolytica MK1 UV mutant | molasses and glycerol | Two-stage fermentation | 113,1 g/l | [21] |

| Y. lipolytica Wratislavia K1 | glycerol | Fed-batch | 81 g/l | [22] |

| Y. lipolytica CICC 1675 | glycerol | One-stage fed-batch fermentation | 194,3 g/l | [8] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fermentation

2.1.1. Analytical methods

2.2. Skin Moisturising Measurement

2.3. Emulsifying Activity Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Fermentations

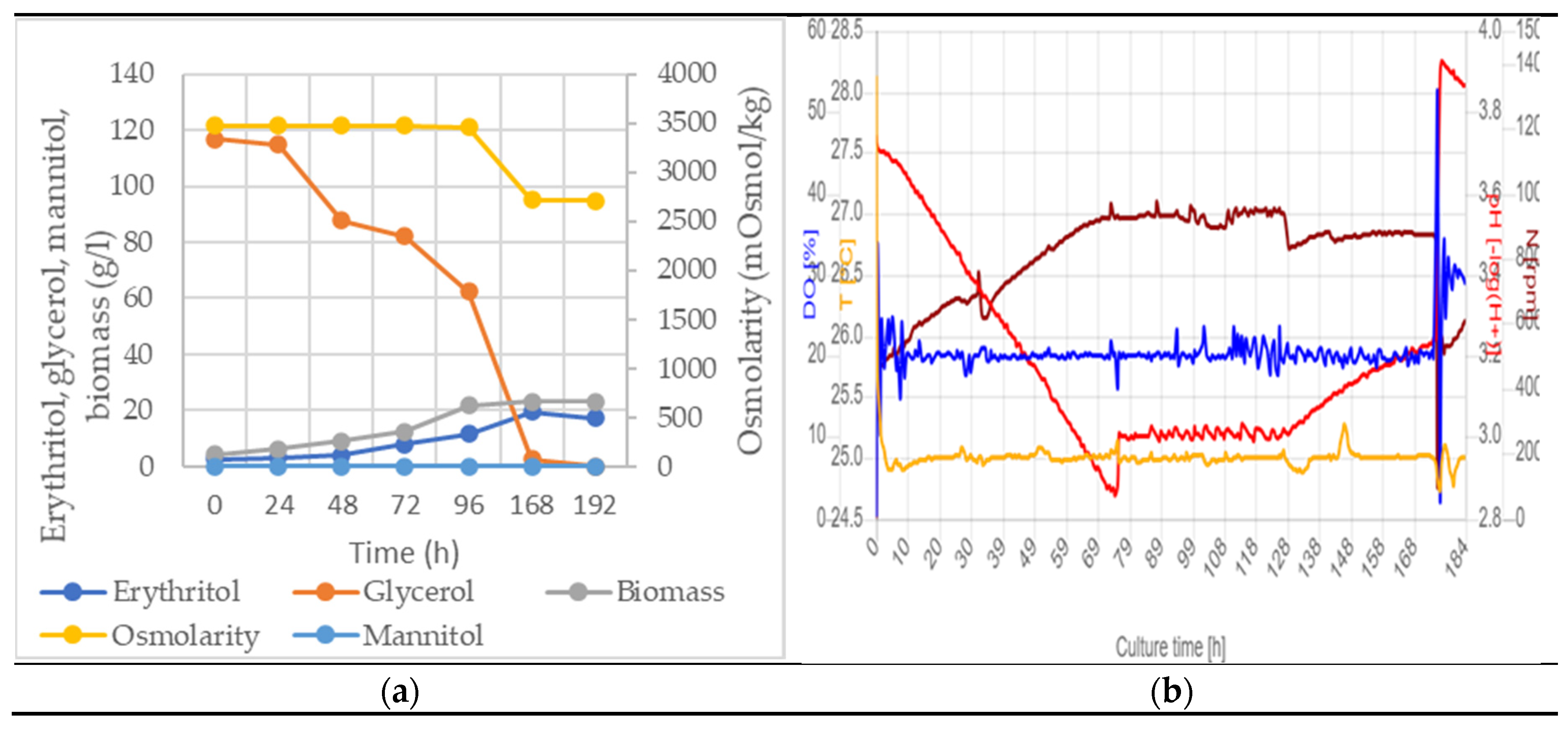

3.1.1. Fermentor

| Oxygen level (%) | Eryhtritol (g/l) | Mannitol (g/l) | Initial osmolarity (mOsmol/kg) | Residual glycerol (g/l) | Biomass (g/l) | Yield (%) | Productivity (g/l)/h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 16.66±2.92 | 0 | 3405±57.88 | 23.8±3.84 | 20.9±0.94 | 22.99±4.64 | 0.06±0.039 |

| 20 | 19.65±3.44 | 0 | 3474±59.05 | 2.72±0.43 | 23.1±1.04 | 14.8±2.99 | 0.12±0.079 |

| 30 | 17.75±3.1 | 13.77±2.73 | 3475±59,07 | 13.33±2.15 | 23.62±1.06 | 14.29±2.88 | 0.123±0.08 |

| 40 | 19.81±3.47 | 2.62±0.52 | 3439±58.46 | 41.98±6.78 | 21±0.94 | 28.85±5.83 | 0.08±0.053 |

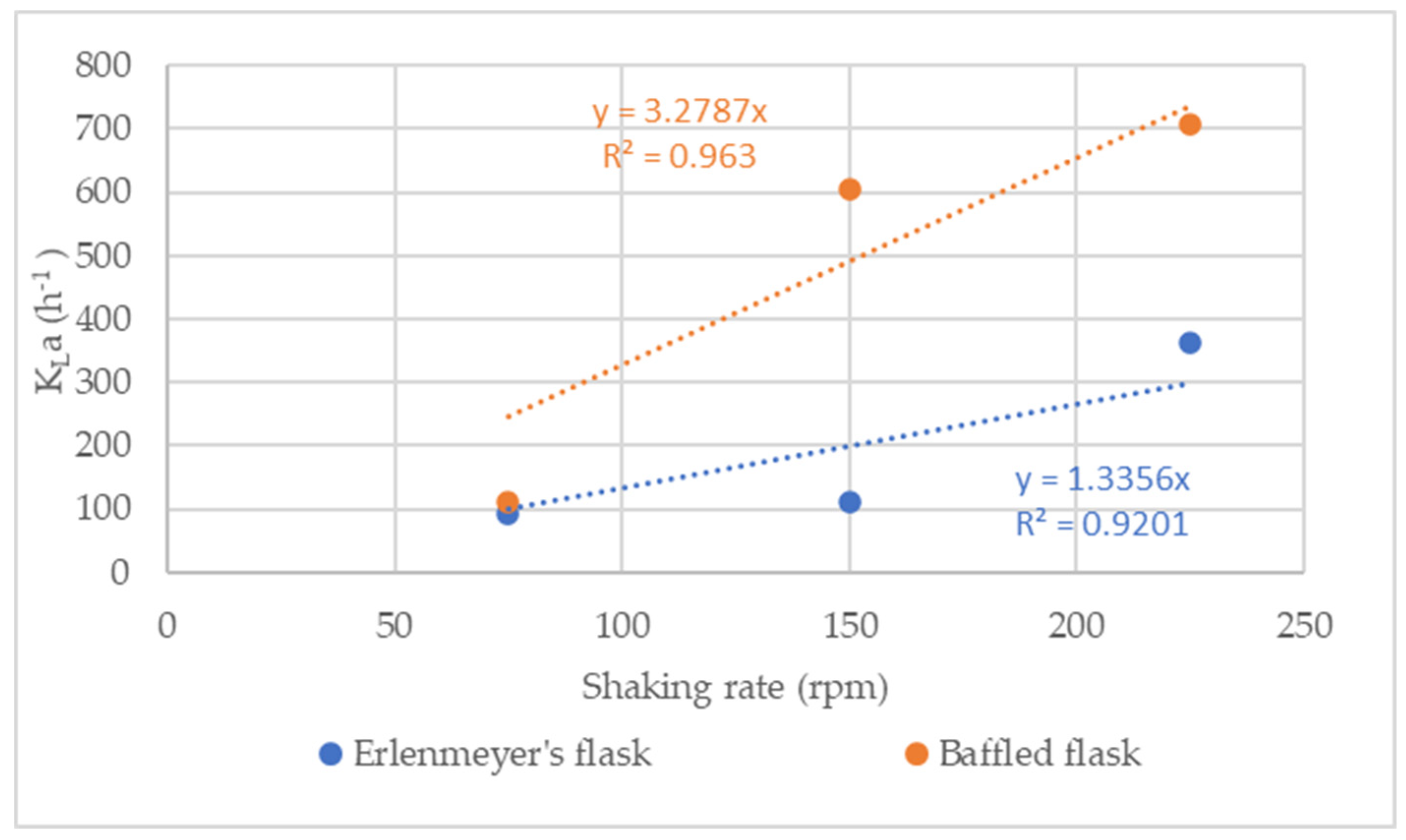

3.1.2. Comparison of Oxygen absorption

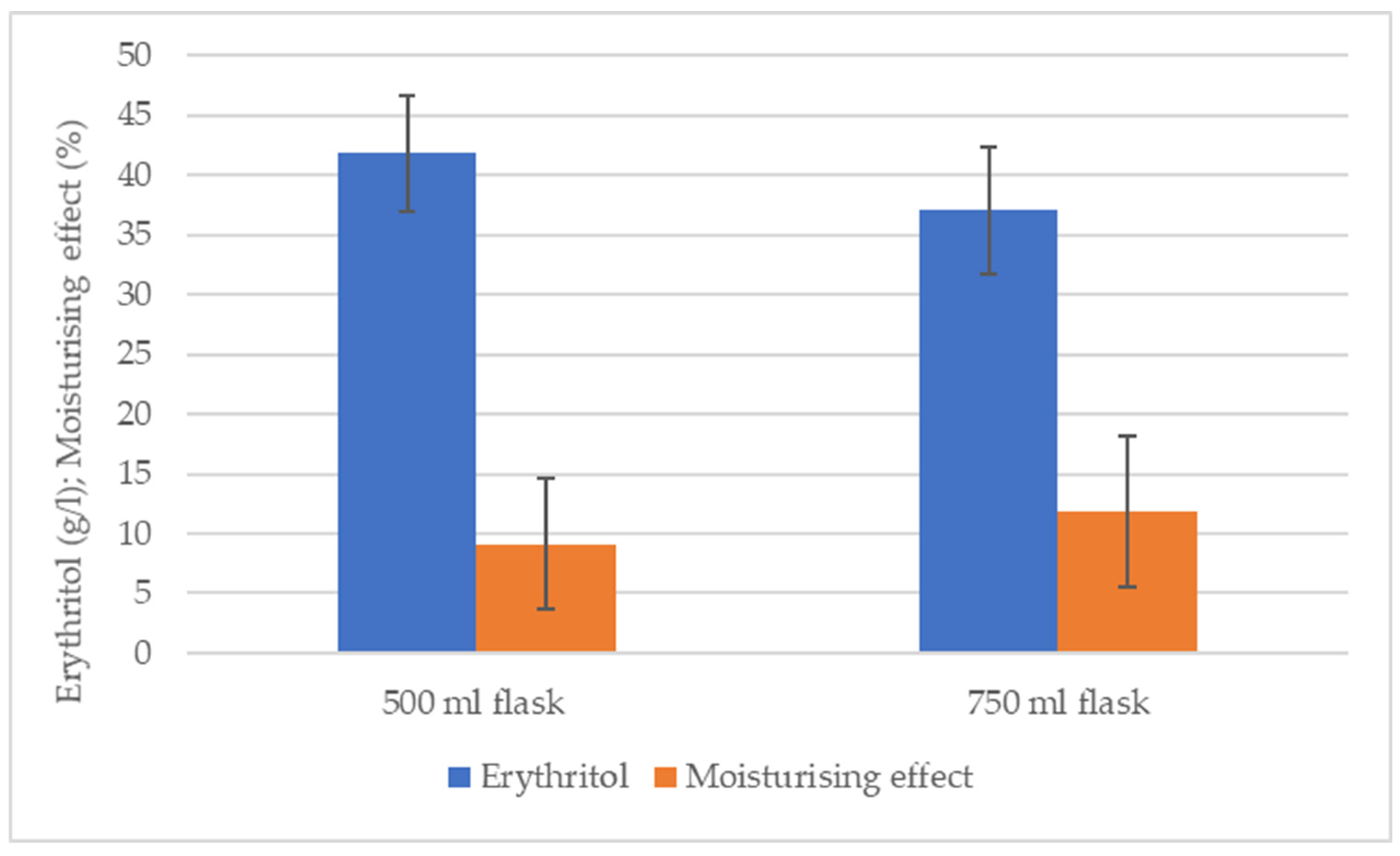

3.1.3. Baffled flasks experiments

| Fermentations | Erythritol (g/l) | Yield (%) | Productivity (g/l)/h | Biomass (g/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erlenmeyer’s flask 500 ml | 14.5±1.1 | 34.5±7.2 | 0.06±0.006 | 6.21±0.28 |

|

Baffled flask 500 ml |

44.14±1 | 26.43±3.37 | 0.19±0.03 | 27.83±0.24 |

|

Baffled flask 750 ml |

42.42±5.08 | 27.74±7.71 | 0.19±0.02 | 23.53±2.1 |

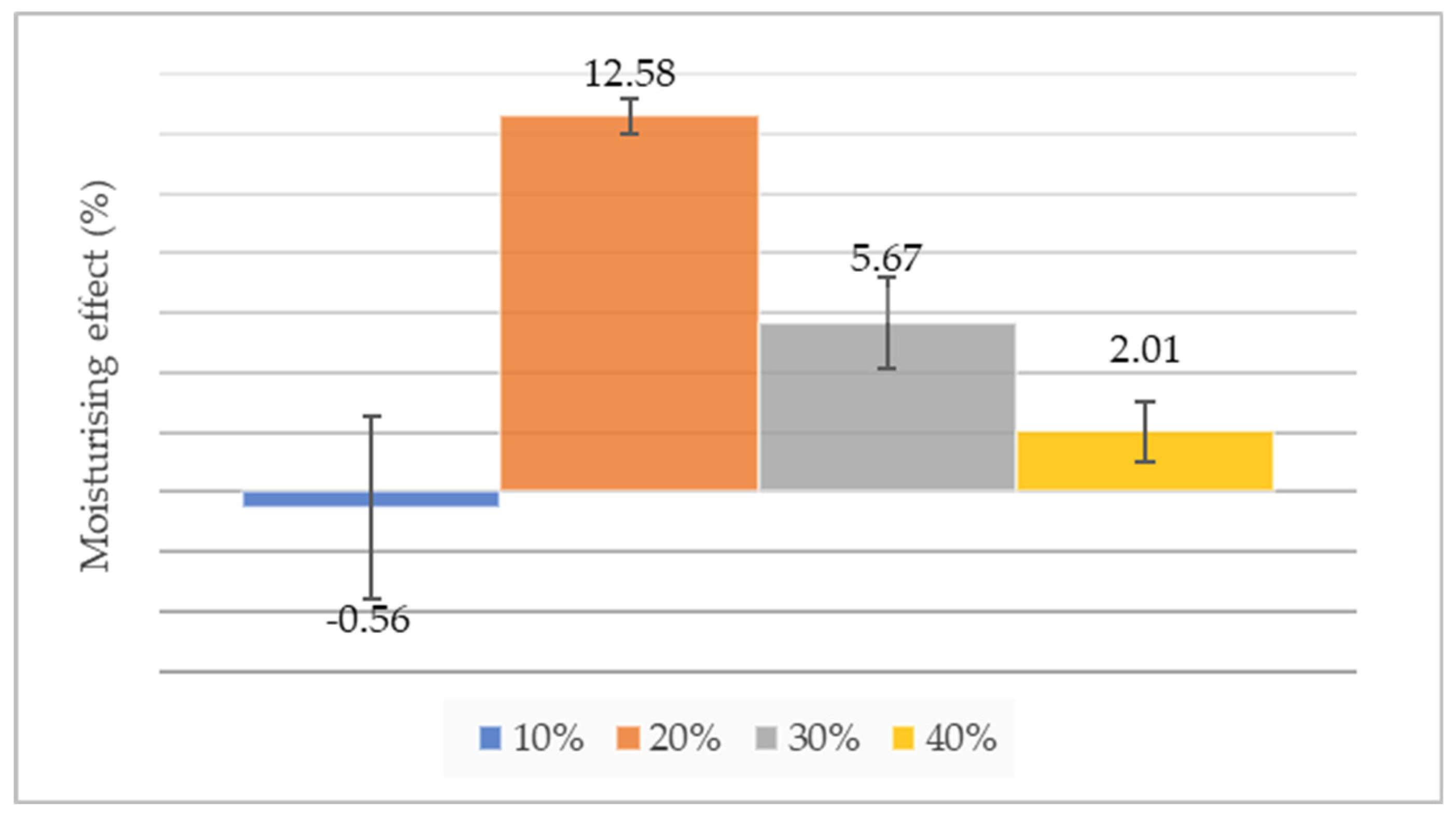

3.2. Skin Moisture Effect Determination

| Oxygen level (%) | Mean of initial values (%) | Mean of final measured values (%) | Calculated moisturising effect (%) | p* |

| 10 | 59.67±1.15 | 59.33±2.31 | -0.56 ± 3.06 | 0,704833 |

| 20 | 53±0 | 59.66±0.58 | 12.58 ± 0.58 | 0,048874 |

| 30 | 47±1 | 49.66±0.58 | 5.67± 1.53 | 0,267720 |

| 40 | 49.66±1.52 | 50.66±2.08 | 2.01 ± 1 | 0,640983 |

| Fermentations (500 ml) | Mean of initial values (%) | Mean of initial measured values (%) | Mean of final values (%) | Mean of final measured values (%) | Calculated moisturising effect (%) | Mean of calculated moisturising effect (%) | p* |

| 1. | 41.66±0.57 | 47.1±5.68 | 48±2.64 | 51.11±5.1 | 15.2±2.3 | 9.11±5.47 | 0.675562 |

| 2. | 53±1.73 | 57±2.64 | 7.54±3.6 | ||||

| 3. | 46.66±7.25 | 48.33±6.43 | 4.59±3.38 | ||||

| Fermentations (750 ml) | Mean of initial values (%) | Mean of initial measured values (%) | Mean of final measured values (%) | Mean of final measured values (%) | Calculated moisturising effect (%) | Mean of calculated moisturising effect (%) | p* |

| 1. | 36.6±0.57 | 43.19±6.37 | 42.6±2.08 | 48.08±4.82 | 16.36±2 | 11.86±6.25 | 0.380797 |

| 2. | 43.66±0.57 | 50±1.73 | 14.5±1.15 | ||||

| 3. | 49.33±0.57 | 51.66±1.15 | 4.72±0.57 |

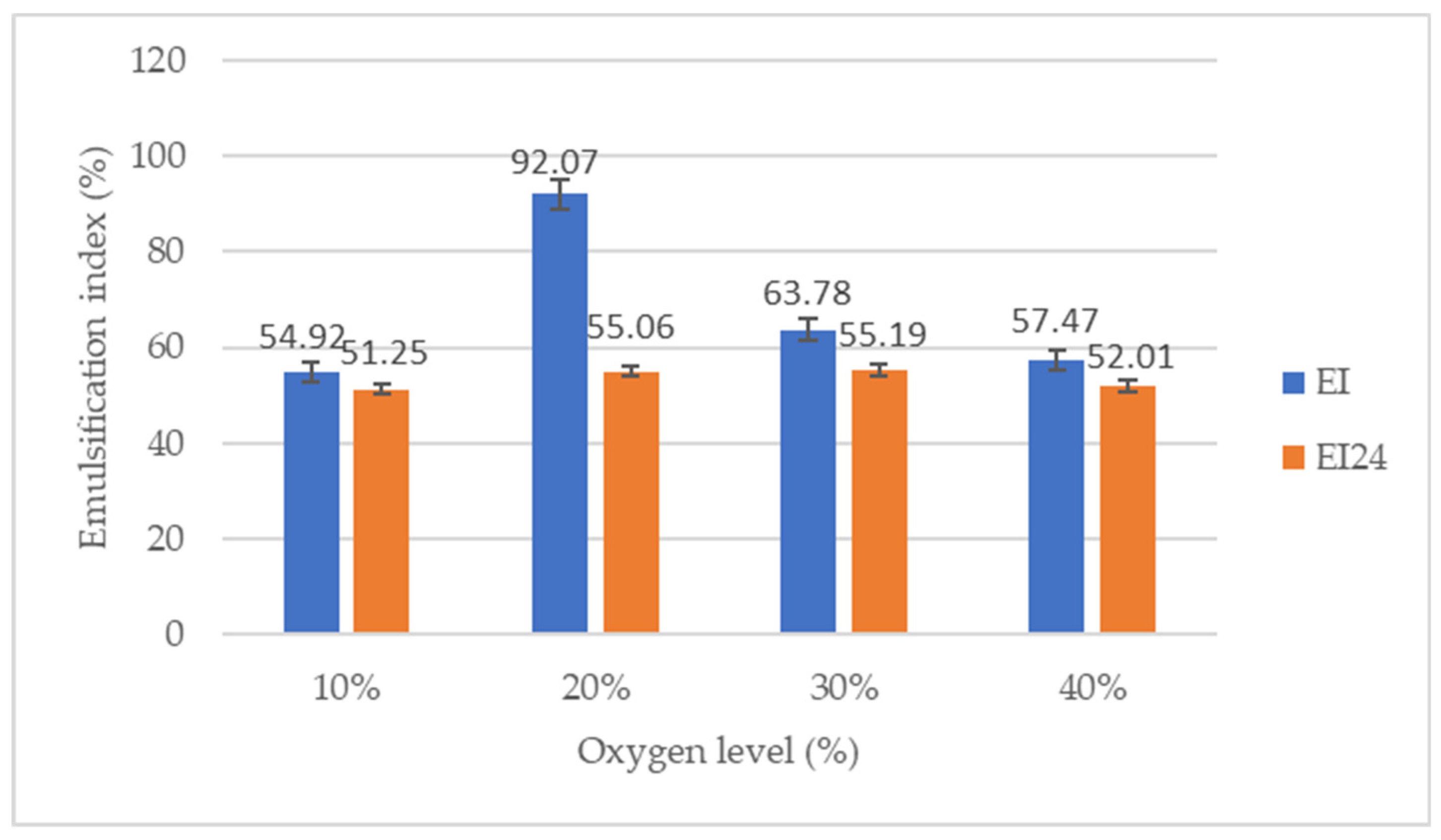

3.3. Emulsifying activity measurements

|

Fermentations (500 ml) |

Emulsification index 1 h(%) | Mean of emulsification index 1 h (%) | Emulsification index 24 h(%) | Mean of emulsification index 24 h (%) |

| 1. | 82.6 | 68.55±13.5 | 52.15 | 53.63±1.85 |

| 2. | 67.38 | 54.91 | ||

| 3. | 55.67±1.96 | 53.85±1.17 | ||

|

Fermentations (750 ml) |

Emulsification index 1 h(%) | Mean of emulsification index 1 h (%) | Emulsification index 24 h(%) | Mean of emulsification index 24 h (%) |

| 1. | 64.36 | 56.45±6.83 | 63.40 | 55.58±6.76 |

| 2. | 52.5 | 51.7 | ||

| 3. | 52.5 | 51.64 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonçalves, F. A. G., Colen, G., & Takahashi, J. A. Yarrowia lipolytica and its multiple applications in the biotechnological industry. The Scientific World Journal, 2014. pp. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Nicaud, Jean-Marc. Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast, 2012, 29 (10) pp. 409-418. [CrossRef]

- Barth, Gerold; Gaillardin, Claude. Physiology and genetics of the dimorphic fungus Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS microbiology reviews, 1997, 19 (4): pp. 219-237. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E. S. Biodiversity of food spoilage Yarrowia group in different kinds of food, Doctoral dissertation, Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest, 2015 . [CrossRef]

- Groenewald, Marizeth, Boekhout, T., Neuvéglise, C., Gaillardin, C., van Dijck, P. W., & Wyss, M. Yarrowia lipolytica: safety assessment of an oleaginous yeast with a great industrial potential. Critical reviews in microbiology, 2014, 40 (3) pp. 187-206. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.A.Z.; Amaral, P.F.F.; Belo, Isabel. Yarrowia lipolytica: an industrial workhorse. Current Research Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology, Formatex Research Center, Badajoz, 2010. 2. pp. 930-944.

- Tomaszewska, Ludwika, Rakicka, M., Rymowicz, W., & Rywińska, A. A comparative study on glycerol metabolism to erythritol and citric acid in Yarrowia lipolytica yeast cells. FEMS yeast research, 2014, 14 (6), pp. 966-976. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Li-Bo, Dai, X. M., Zheng, Z. Y., Zhu, L., Zhan, X. B., & Lin, C. C. Proteomic analysis of erythritol-producing Yarrowia lipolytica from glycerol in response to osmotic pressure. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Rymowicz, Waldemar; Rywinska, Anita; Marcinkiewicz, Marta. High-yield production of erythritol from raw glycerol in fed-batch cultures of Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnology Letters, 2009, 31, pp. 377-380. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Edina, Niss, M., Dlauchy, D., Arneborg, N., Nielsen, D. S., & Peter, G. Yarrowia divulgata fa, sp. nov., a yeast species from animal-related and marine sources. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63. Pt_12, pp. 4818-4823. [CrossRef]

- Rakicka, Magdalena, Kieroń, A., Hapeta, P., Neuvéglise, C., & Lazar, Z. Sweet and sour potential of yeast from the Yarrowia clade. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2016, 92, pp. 48-54. [CrossRef]

- Rakicka-Pustulka, Magdalena, Joanna Miedzianka, Dominika Jama, Sylwia Kawalec, Kamila Liman, Tomasz Janek, Grzegorz Skaradziński, Waldemar Rymowicz & Zbigniew Lazar, High value-added products derived from crude glycerol via microbial fermentation using Yarrowia clade yeast. Microbial Cell Factories, 2021, 20, pp. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, Abdul Rahman, Jinle Liu, Zhi Wang, Anqi Zhao, Hanjie Ying, Lingbo Qu, Md. Asraful Alam, Wenlong Xiong, Jingliang Xu, Yongkun Lvet al. Recent advances in producing sugar alcohols and functional sugars by engineering Yarrowia lipolytica. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2021, 9: 648382. [CrossRef]

- Godswill, Awuchi Chinaza. Sugar alcohols: chemistry, production, health concerns and nutritional importance of mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, and erythritol. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research, 2017, 3 (2), pp. 31-66. ISSN: 2488-9849.

- De Cock, Peter. Erythritol. Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology, 1st ed., Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2012, pp. 213-241. ISBN: 978-1-118-37397-2.

- Martau, Gheorghe Adrian; Coman, Vasile; Vodnar, Dan Cristian. Recent advances in the biotechnological production of erythritol and mannitol. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 2020, 40(5), pp. 608-622. [CrossRef]

- Rakicka-Pustulka, Magdalena, M., Mirończuk, A. M., Celińska, E., Białas, W., & Rymowicz, W., Scale-up of the erythritol production technology–process simulation and techno-economic analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 257: 120533. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, Ludwika; Rywinska, Anita; Gladkowski, Witold. Production of erythritol and mannitol by Yarrowia lipolytica yeast in media containing glycerol. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2012, 39(9), pp. 1333-1343. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska-Hetman, Ludwika; Rywisnka, Anita. Erythritol biosynthesis from glycerol by Yarrowia lipolytica yeast: effect of osmotic pressure. Chemical Papers, 2016, 70 (3), pp. 272-283. [CrossRef]

- Rakicka, Magdalena, Rukowicz, B., Rywińska, A., Lazar, Z., & Rymowicz, W., Technology of efficient continuous erythritol production from glycerol. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2016, 139, pp. 905-913. [CrossRef]

- Mironczuk, Aleksandra M., Rakicka, M., Biegalska, A., Rymowicz, W., & Dobrowolski, A., A two-stage fermentation process of erythritol production by yeast Y. lipolytica from molasses and glycerol. Bioresource technology, 2015, 198, pp. 445-455. [CrossRef]

- Rymowicz, Waldemar; Rywisnka, Anita; Gladkowski, Witold. Simultaneous production of citric acid and erythritol from crude glycerol by Yarrowia lipolytica Wratislavia K1. Chemical Papers, 2008, 62 (3), pp. 239-246. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Shuling, Pan, X., Wang, Q., Lv, Q., Zhang, X., Zhang, R., & Rao, Z., Enhancing erythritol production from crude glycerol in a wild-type Yarrowia lipolytica by metabolic engineering. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022, 13: 1054243. [CrossRef]

- Janek, T., Dobrowolski, A., Biegalska, A., & Mirończuk, A. M. Characterization of erythrose reductase from Yarrowia lipolytica and its influence on erythritol synthesis. Microbial Cell Factories, 2017, 16, pp. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Moon, Hee-Jung, Jeya, M., Kim, I. W., & Lee, J. K., Biotechnological production of erythritol and its applications. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 2010, 86, pp. 1017-1025. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, Luana Vieira, Coelho, M.A.Z., Amaral, P.F.F., & Fickers, P., A novel osmotic pressure strategy to improve erythritol production by Yarrowia lipolytica from glycerol. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering, 2018, 41, pp. 1883-1886. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, Sujit Sadashiv, Bedekar, A. A., Singh, V., Jin, Y. S., & Rao, C. V., Metabolic engineering of the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica PO1f for production of erythritol from glycerol. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 2021, 14 (1), pp. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Ana Margarida Magalhães. Erythritol production from crude glycerol by Yarrowia species: strains comparison and oxygen influence. Master’s degree. Universidade do Minho (Portugal), 2021. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/71303.

- Machado, Ana Rita Araújo. Production of the sweetener erythritol by Yarrowia lipolytica strains. Master’s degree. Universidade do Minho (Portugal), 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/59234.

- Li, Jian, Kun Zhu, Lin Miao, Lanxin Rong, Yu Zhao, Shenglong Li, Lijuan Ma, Jianxun Li, Cuiying Zhang, Dongguang Xiao, Jee Loon Foo, and Aiqun Yu., Simultaneous improvement of limonene production and tolerance in Yarrowia lipolytica through tolerance engineering and evolutionary engineering. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2021, 10 (4), pp. 884-896. [CrossRef]

- Ben Tahar, Imen, Kus-Liśkiewicz, M., Lara, Y., Javaux, E., & Fickers, P., Characterization of a nontoxic pyomelanin pigment produced by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnology progress, 2020, 36.2: e2912. [CrossRef]

- Trindade, Joana R., Freire, M. G., Amaral, P. F., Coelho, M. A. Z., Coutinho, J. A., & Marrucho, I. M., Aging mechanisms of oil-in-water emulsions based on a bioemulsifier produced by Yarrowia lipolytica. Colloids and Surfaces A: physicochemical and engineering aspects, 2008, 324.1-3, pp. 149-154. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, Joselma Ferreira, da Silva, L. A. R., Barbosa, M. R., Houllou, L. M., & Malafaia, C. B., Bioemulsifier produced by Yarrowia lipolytica using residual glycerol as a carbon source. Journal of Environmental Analysis and Progress, 2020, 5.1, pp. 031-037. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, P. F. F., Da Silva, J. M., Lehocky, B. M., Barros-Timmons, A. M. V., Coelho, M. A. Z., Marrucho, I. M., & Coutinho, J. A. P., Production and characterization of a bioemulsifier from Yarrowia lipolytica. Process Biochemistry, 2006, 41.8, pp. 1894-1898. [CrossRef]

- Cirigliano, Michael C.; Carman, George M. Isolation of a bioemulsifier from Candida lipolytica. Applied and environmental microbiology, 1984, 48.4, pp. 747-750. [CrossRef]

- Cirigliano, Michael C.; Carman, George M. Purification and characterization of liposan, a bioemulsifier from Candida lipolytica. Applied and environmental microbiology, 1985, 50.4, pp. 846-850. [CrossRef]

- Sarubbo, Leonie A., Marçal, M. D. C., Neves, M. L. C., Silva, M. D. P. C., Porto, L. F., & Campos-Takaki, G. M., Bioemulsifier production in batch culture using glucose as carbon source by Candida lipolytica. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2001, 95, pp. 59-67. [CrossRef]

- Santos, Danyelle KF, Rufino, R. D., Luna, J. M., Santos, V. A., Salgueiro, A. A., & Sarubbo, L. A., Synthesis and evaluation of biosurfactant produced by Candida lipolytica using animal fat and corn steep liquor. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2013, 105, pp. 43-50. [CrossRef]

- Béla, Sevella. Biomérnöki műveletek és folyamatok. 2nd ed.; Typotex, Budapest, 2012. pp. 392-393. ISBN 978-963-279-470-9.

- Tóth, Pál; Németh, Áron. Investigation and Characterisation of New Eco-Friendly Cosmetic Ingredients Based on Probiotic Bacteria Ferment Filtrates in Combination with Alginite Mineral. Processes, 2022, 10.12: 2672. [CrossRef]

- Czinkóczky, Réka; Németh, Áron. The effect of pH on biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis DSM10. Hungarian Journal of Industry and Chemistry, 2020, pp. 37-43. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).