1. Introduction

The

Vitaceae family includes mostly shrubs and woody lianas that climb using leaf-opposed tendrils. Most grape cultivars belong to the

Vitis genus, consisting of 83 inter-fertile species [

1] that exist primarily in the Northern Hemisphere including North America and East Asia. The Eurasian species of common grapevine,

Vitis vinifera var.

sylvestris Willd. [

2] (hereafter Sylvestris) is the best-known as it is the ancestor of most cultivated grapes grown today [

3,

4,

5]. The cultivated form

V. vinifera ssp.

sativa (hereafter Sativa) is one of the most important perennial crops which is cultivated across 7.3 hectares around the world [

6]. The distinction between these two subspecies rely largely on the differences in the reproductive organs morphology, namely while the wild grapevine is dioecious, Sativa is a hermaphrodite [

5,

7,

8].

Sylvestris was naturally grown abundantly in Europe until the mid-19th century, when penetration of pests and pathogens from North America, including phylloxera, powdery and downy mildews, caused a decrease in wild grapevine populations [

8]. Later, the accelerating urbanization processes and extensive anthropogenic land use dramatically damaged the natural habitats of Sylvestris populations, reducing its distribution range and endangering the species persistance [

9,

10]. While Sylvestris populations were shrinking, Sativa was flourishing throughout Europe and Eastern Mediterranean region by the end of the 19th century, “cultivated everywhere in numerous varieties, but nowhere strictly spontaneous” [

11].

The Southern Levant was considered as region beyond the distribution range of Sylvestris, thus early studies of Israeli vegetation during the 20th century considered all grapevine plants as cultivars (Sativa) and the species was not included in the local wild flora records until 2004 [

12]. The first indications for Sylvastris in the Southern Levant region was in 1994 based on surveys in the Upper Galilee region; along the banks of Jordan River [

13,

14]. Nevertheless, the available recods of these surveys lack the necessary description and exact location of the observed plants, therefore, generally, grapevines observed in the wilds in Israel were considered feral populations with no clear support.

Over the years, more evidence for native Southern Levantine Sylvestris have accumulated. Archaeobotanical pips and wood of Sylvestris plants were discovered in the region from Lower Paleolithic Gesher Benot Ya’aqov (780,000 BP) and from Upper Palaeolithic Ohalo II (23,000 BP) archaeological sites [

15,

16,

17,

18]. These archaeological sites are located around the area of Sea of Galilee and Jordan River, in high geographic proximity to the populations observed in 1995 survey.

A more recent comprehensive survey of grapevines in Israel discovered new populations of hermaphrodite and dioecious plants [

19]. Genetic analysis with SSR markers and morphological characterization of the collection indicated that the hermaphrodite accessions were clearly separated from the dioecious groups, having additional wild grapevine phenotypes (leaf, bunch and berry shape, etc.). Moreover, dioecious Sylvestris accessions were further split between two distinct subgroups in accordance with ecogeographic divergence. These populations, occurring primarily along the main streams in the Upper Galilee region and around the Sea of Galilee, mark the southern edge of the distribution range of Sylvestris [

20].

Deeper analyses of these accessions using whole genome sequencing data further supported the previous observations that Sylvestris has grown naturally in the Southern Levant for Millenia [

21]. In fact, the Sylvestris accessions were identified as progenitors of domesticated indigenous varieties from the Levant with genetic contribution to some of the European varieties [

21,

22]. These conclusions were further supported in a recent comprehensive genomic study of more than 3,500 accessions which provided an unequivocal evidence for the contribution of Southern Levantine Sylvestris populations to domesticated grapevine around the world [

23]. The Sylvestris populations from Israel (E1) were identidfied as the genetic source table-grape group (CG1) [

23]. This group later genetically contributed to most known wine grape varieties used in modern times worldwide.

Despite the number of studies and evidence for the thrive of Sylvestris populations in Israel, no colnclusive support and clear definition has been provided so far. This gap opens room for skeptism with implications on the interpretation of genomic studies of domestication, ecology and evolution. Here, we provide a comprehensive morpho-anatomical characterization of Sylvestris populations representing the two main subgroups in Israel including a deep characterization of male and female flowers, the distribution dynamics of male and female individuals in each region, and the natural regeneration by germination. The results clearly affirm that the populations inspected are truly assigned to the protologue and type specimens of Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris.

2. Materials and Methods

Plant material and research area: Sampling was carried out during the spring (May 2022) in Northern Israel where stable populations of Sylvestris were previously observed [

20]. Forty-six Sylvestris accessions were collected from the Banias River in the Upper Galilee (33°12’12.3”N 35°38’27.6”E), and the Beit Tsaida site located next to the Sea of Galilee (32°53’09.2”N 35°38’34.6”E), from an area of about 8000 m

2 in each site (

Figure 1). For each accession, twigs with young and mature leaves, as well as flowers were collected. A subsample of each accession was dried and prepared for Herbaria deposition, and remaining parts were fixed and stored in FAA solution (formaldehyde: acetic acid: 70% ethanol, 1:1:20) for histomorphological inspection (samples are held in the Ariel University). The exsiccata of all accessions were deposited at Tel Aviv University (voucher specimen numbers from TELA4443 to TELA4450).

Leaf: The leaf morphology was examined in dry herbarium specimens. We measured the length of the petiole, length and width of the leaves in their greatest extension, and calculated the ratio between length and width and the length ratios of the blade to the petiole. We noted the shade difference between the abaxial and adaxial sides of the leaf lamina, determining whether leaves are concolourous or discolourous. We described the leaf form according to the glossary in Kafkafi [

24].

Seed and berry: Approximately 60 seeds and 100 berries from each site were used for morphological characterization and statistics. The metric measurements (Berry diameter, seed length and width) were taken using a Sparkfun electronics digital calliper (0-15 mm), and the data presented is the range of sizes (min-max). In addition, morphological descriptors (OIV) [

25] were used to describe the morphological traits of seeds and berries.

Flower: Male and female flowers were placed on a microscope glass slide wrapped or unwrapped with black paper and illuminated with white LED light. Images were captured with a Nikon SMZ25 stereo-microscope (Nikon Ltd., Japan) equipped with a camera (Nikon DS-Ri2). Sixty digital photo-micrographs (resolution: 4908×3264 pixels), with each step about 50 µm, were taken at different focal planes and compiled to a single image using ND2-NIS elements software with an extended depth of focus (EDF) patch (Nikon Instruments, Japan). Images were then transformed into a single high-quality focused image using the dedicated software.

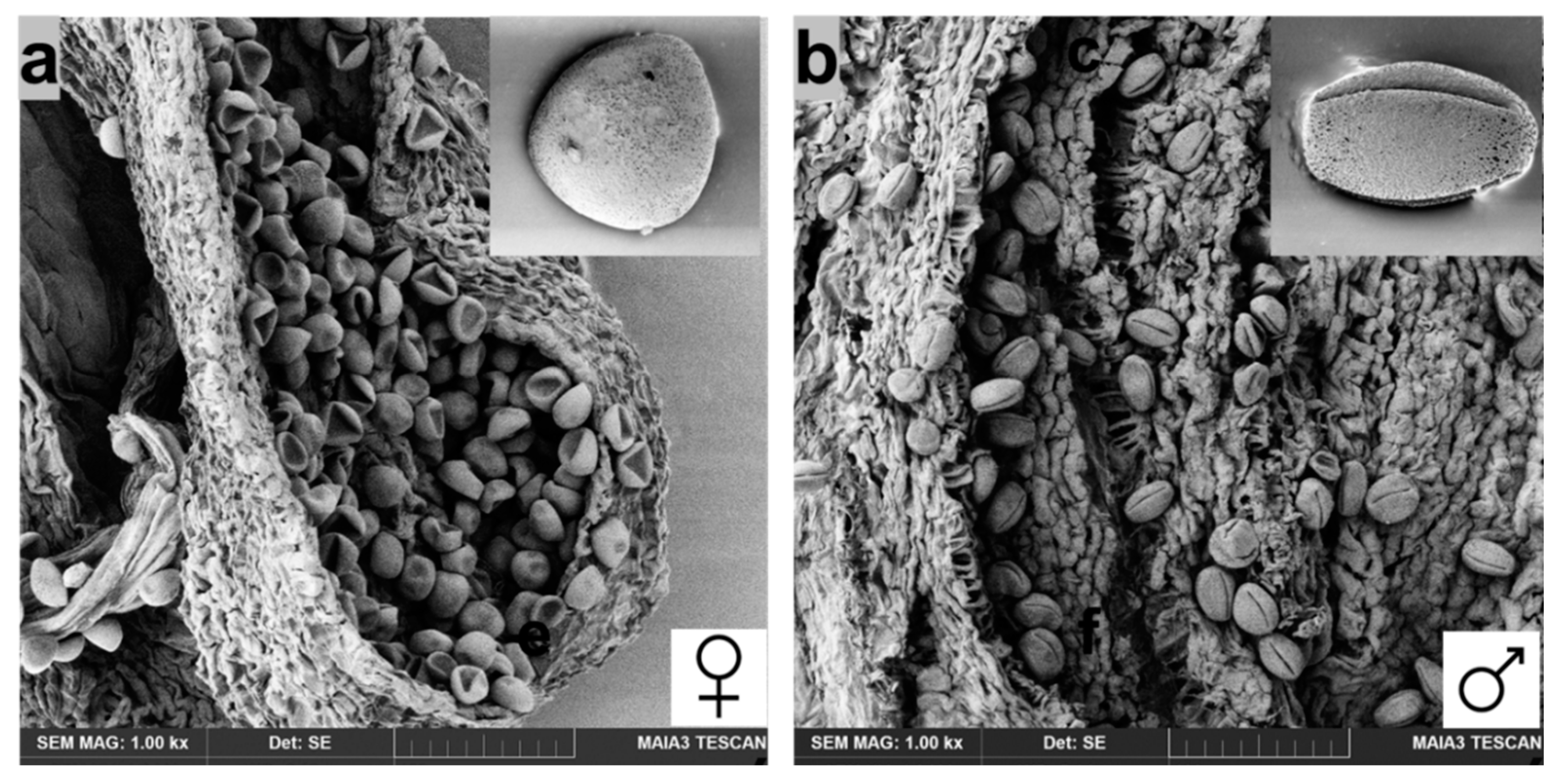

Pollen: Dried anthers with pollen grains were coated with gold using sputter machine (Quorum Q-150T ES). The prepared samples were then imaged using FE-SEM (Tescan Ultra - High Resolution MAIA 3). Beam voltage 1.0 kV and SE detector were used for samples.

Tissue histology: Tissue samples of male and female flowers were fixed in FAA (formaldehyde: acetic acid: 70% ethanol, 1:1:20), embedded in paraplast, sectioned at 12 micron thickness with a rotary microtome (SLEE medical GmbH, Germany) and stained with safranin-alcian blue stain [

26]. The slides were photographed under Olympus SZX7 stereo-microscope equipped with a camera (Pixelink USB 3.0, Canada) and using PixeLINK Capture program.

3. Results

Sylvestris growth habit in wild habitats: In this study, we focused on the two sites where stable and large grapevine populations were previously reported [

20]; the northern site at the Banias River, and the southern site at Beit Tsaida (

Figure 1). Both sites are located in protected natural reserves (Banias and Majrase, respectively). Sampling was performed randomly along the water streams where grapevine grows in each site, thus a total of 46 accessions were sampled of which 32 are from Beit Tsaida, and 14 from the Banias River.

Sampling was performed during the spring when plants were in full blossom which enables to identify developing pistils and stamens in dioecious (unisexual plants) or monoecious plants. All

vitis plants at both sampling sites were dioicous, supporting their identification as true Sylvestris. The ratio between male and female plants is close to 1, with a slightly higher number of male accessions (

Table 1). This finding strengthens our assumption that the examined populations are wild, with no bias toward the fructiferous female form [

27].

Growth habit varied between male and female grapevines at both locations. Male grapevines were taller and tended to climb to the tops of trees, while female grapevines were shorter and tended to prostrate in a tangle of low vegetation (

Figure 2a, b). The male grapevines were characterized by multiple and densely packed flower clusters, usually located near the top of the vine (

Figure 2b), and females produced fewer and smaller flower clusters (

Figure 2c) which were located lower along the stem. These male climbing habit may be attributed to wind-pollination strategy [

28] and the low stature of the female may be required to structurally support the heavy bunches of fruits. The sexual dimorphism observed in plants height and inflorescence position seem adaptive to the natural habitat.

In our current survey, grapevines were growing in deep uncultivated soils very close to flowing sweet water, as was previously reported [

20]. Male and female plants were spread randomly. In both sites, the wild grapevines grow in proximity to fig trees (

Ficus carica), plane trees (

Platanus orientalis)

, and holy raspberries (

Rubus sanguineus). This plant community is typical to water-rich habitats along the Mediterranean basin. Interestingly, the observed Sylvestris female plants tended to grow between the spiny holy raspberry plants which provide protection from herbivores that are abundant in these regions including the wild boar (

Sus scrofa) and gazell (

Gazella gazella) which commonly feed from grapevine shoots and leaves. On the other hand, male Sylvestris plants tend to climb higher trees as means of support, avoidance of both herbivores, and competition for sunlight.

Overall, the observed populations at both sites has a distinctive appearance with a significant polymorphism in leaves, and clusters of small, greenish-yellow flowers developed into black berries. Its growth habit and woody stem make it a hardy plant providing cover and habitat for various animals in its natural environment [

29,

30].

3.2. Morphology

Leaf morphology: Leaf shape and morphology show a high polymorphism, ranging from reniform with weak lobation to cordate with pronounced lobation. No significant correlation between leaf shape and sampling location was observed and length-width blade ratios (t-test, p-value>0.05)) (

Table 2). The blade-petiole length ratio was higher in Beit Tseida (t-test, p-value<0.0001). The dorsal surface of the leaves from Banias was found to be hairy in contrast to leaves from Beit Tseida. This results in a shade contrast, causing the leaves in the Banias populations to be discolored, while the Beth Tseida populations have concolor leaves.

Berry and seed morphology: Growing conditions have a dramatic effect on the number and size of grapes berries and seeds. To obtain healthy, large berries and seeds for inspection and characterization cuttings were sampled from plants at both sites and were grown under optimal conditions at the experimental vineyard station in Ariel University [

33].

Figure 3a showes well grown and dense fruit bunches when grown under irrigation, while

Figure 3b shows the sporadic of Sylvestris bunches grown in the wild. A broad range of polymorphism in cluster shapes was observed among samples, yet most of them had sparse clusters of tiny, typically black berries, that usually contain 2-3 seeds (

Figure 3c). The berries diameter was found to be significantly different (p-value < 0.001) between the populations when Banias Sylvestris berries being bigger than those of Beit Tseida (

Table 2). In both populations, the berry’s skin is thin, and the pulp is juicy and sweet with high acid levels, but lower than those found for European Sylvestris grapes [

19]. The seeds length was differed significantly between sampling sites (t-test, p-value < 0.001), where the seeds from Beit Tsaida were larger (mean = 5.38, sd = 0.45)(

Table 2). These values correspond to Sylvestris varieties and were previously recorded [

34,

35].

Flower morphology: The main feature that distinguishes between wild and domesticated grapevine is the flower and more specifically the reproductive organs. The flowers of the wild grapevine are small and greenish-yellow and are arranged in panicles. The individual flowers have a diameter of around 5 mm and contain five petals fused at the base. The flowering occurs in the month of May, giving rise to fruit on female individuals later in the summer (August). The structure of the male flower is distinctly different from that of the female flower (

Figure 4). The female flower includes an ovary and reflexed rudimentary/atrophied stamens that angle downwards, while the male flower displays upright stamens and a reduced pistil without style or stigma and an rudimentary/atrophied ovary at the base. These features are clearly distinctive to Vitis sylvetris plants, while the Sativa forms, also found ocasionly feral, all have an hermaphrodite phenotype.

The histological sections of the female grapevine flower show a single ovary (

Figure 4c), a style, and a stigma, which comprise the pistil. The ovary is located at the base of the flower and contains ovules that will eventually develop into seeds if fertilized by pollen (

Figure 4c). In contrast, the male grapevine flower sampled at the same location had a different structure which consists of an atrophied ovary and stamens that are arranged in a tight cluster at the base of the flower. The stamens produce and release pollen grains from wind and/or insects to the female flowers, allowing for fertilization and fruit production [

36].

Pollen grains morphology: A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was utilized to image the pollen of Sylvestris accessions sampled at experimental vineyard (

Figure 5). In the male flowers, the pollen grains exhibited tricolpate morphology (with three furrows), and were ellipsoid in shape. In the female flowers, the pollen grains were inaperturate and spheroidal in shape (

Figure 5). Additionally, pollen grains found on anthers in female flowers appeared collapsed or exausted, and potent in male flowers further supporting deiocy. The morphological description of pollen grains in grapevines is consistent with previous findings on the differences between sterile and fertile pollen grains in Sylvestris [

37,

38].

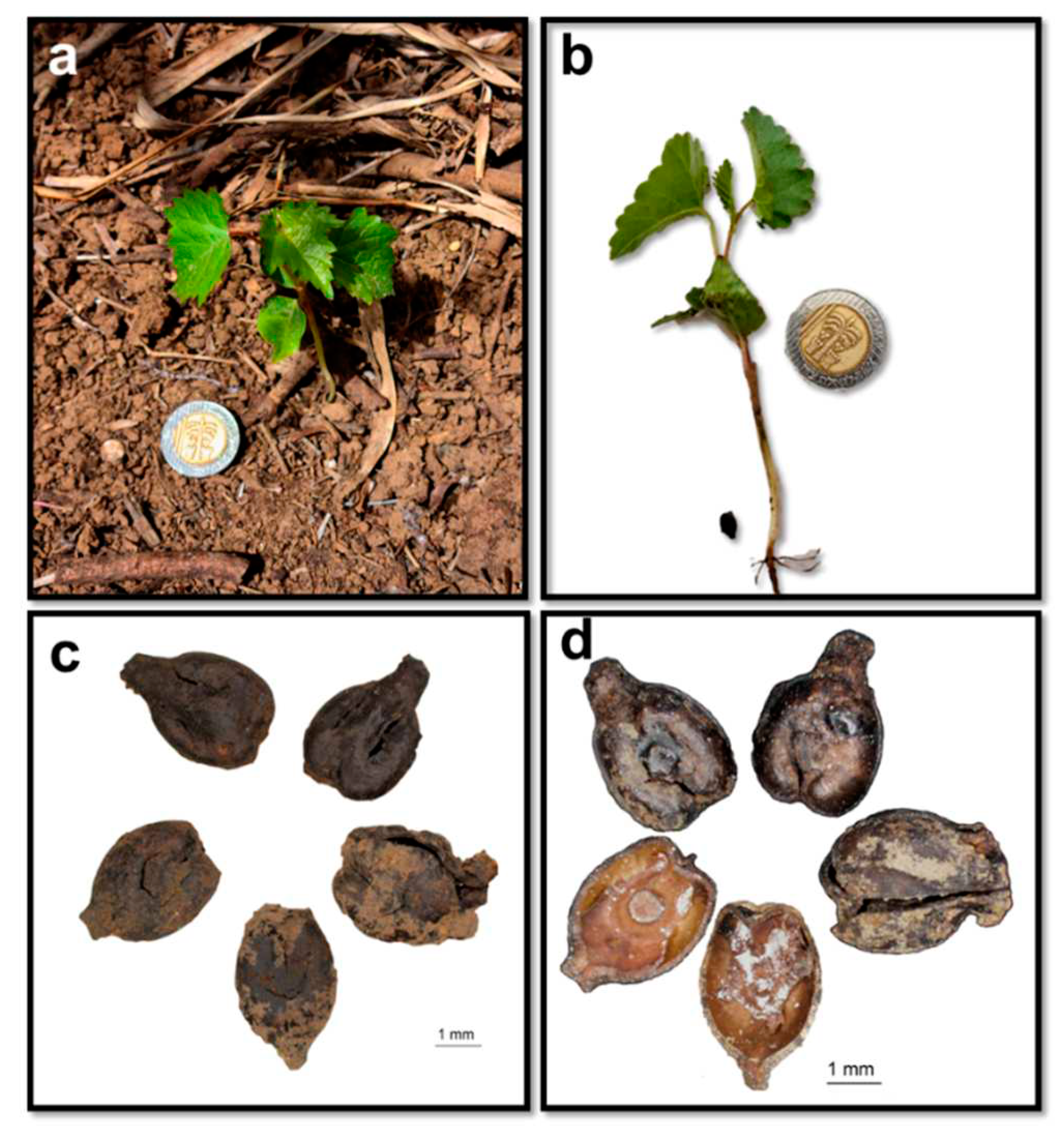

Natural seed germination: We conducted a thorough survey of the Sylvestris habitats in the wild in search for natural germination of seedlings. In the Banias area, we found five seedlings, all beneath female plants (

Figure 6a). This germination habit was abundant indicarting its success under the ecological conditions of this specific natural habitat. The young plantlets were carefully removed from the soil with their seed hulks (

Figure 6c,d). The grapevine seeds were clearly identified despite being slightly damaged and soiled. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that natural germination of Sylvestris in its natural habitat has been recorded. These natural germinations at a natural habitat provide a strong evidence for the authenticity and persistence as a stable population of Sylvestris as an indigenous plant in Israel. Due to the growth habit of Sylvestris inside a dense bush of spiny raspberry plants we failed to identify young seedlings at the Beit Tseida area.

4. Conclusions

Previously, grapevine found growing in the wilds at the northern part of Israel, were considered to be feral sativa plants, and there was no confidence as to the occurrence of Vitis sylvestris in Israel. The reasons were the lack of a comprehensive survey, and the minimal description of this population by the survayors, giving only briff and amorphic descriptions [

13,

14]. Here, we systematically described the habitats, growth habits, morphology and anatomy of widly spread wild grapevine populations growing in two habitats. All of the above findings, including the dioicous nature of the wild grapevine plants, the sexual dimorphism between male and female plants, the characteristic traits of the flower, pollen, berry, and seed structure, and the natural regeneration of the population from seeds, together with our previous genomic findings showing clear separation of these populations from feral Sativa accessions, all lead us to the conclusion that natural wild grapevine populations grow in Israel. Our results indicate that wild grapevine occurrs in nature reserves located within the region of its ancient area of appearance during the Pleistocene [

39].

The high importance of this botanical definition, clearing up any previous uncertainty as to the definition of these populations as Sylvestris is due to the emerging importance of these wild populations as representatives of the core population from which the cultivated grapevine was first domesticated sirca 11,000 years ago [

23]. These facts also emphasize the significance of conservation of the environmental conditions and biodiversity of the Sea of Galilee and the forest habitats in the Upper Galilee, as the main habitats of this important populations.

In sum, the evidences presented here confidently support the persistence of the wild grape species in the Israeli flora, moving the southern edge of its global distribution. As a result, Israel can be confidently added to the native distribution of Vitis vinifera, and this plant included in the Flora Palaestina.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, O.R.; E.D.; E.W.; methodology, O.R.; E.D.; I.S.; J.Z.B.; validation, O.R.; E.D.; I.S.; J.Z.B.; formal analysis, O.R.; J.Z.B.; investigation, O.R; S.F; E.D.; resources, E.D.; data curation, O.R.; J.Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.R.; M.M.K.; E.D. writing—review and editing, O.R.; J.Z.B.; I.S.; M.M.K.; S.F.; S.H.; E.W.; E.D.; visualization, O.R.; M.M.K.; E.D.; supervision, E.D..; S.H; project administration, E.D.; funding acquisition, E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Israeli Ministry of Inovation, Science and Technology (MOST), and the Eastern Regional R&D Center. We thank Olga Krichevski for her great help with the SEM imaging.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WFO. The World Flora Online. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000040377 (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- IPNI Vitis Vinifera Var. Sylvestris Willd. Available online: https://www.ipni.org/?q=Vitis vinifera sylvestris (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Hegi, G. Illustrierte Flora von Mitteleuropa; Verlag, H.K., Ed.; Munich, 1925;

- Heywood, V.H.; Zohary, D. A Catalogue of the Wild Relatives of Cultivated Plants Native to Europe. Flora Medit 1995, 5, 375–415. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, D.; Spiegel-Roy, P. Beginnings of Fruit Growing in the Old World. Science 1975, 187, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

OIV State of the World Vitivinicultural Sector in 2020; 2021.

- Caporali, E.; Spada, A.; Marziani, G.; Failla, O.; Scienza, A. The Arrest of Development of Useless Reproductive Organs in the Unisexual Flower of Vitis Vinifera Ssp Silvestris. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae; 2003; Vol. 603; pp. 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- This, P.; Lacombe, T.; Thomas, M.R. Historical Origins and Genetic Diversity of Wine Grapes. Trends in genetics : TIG 2006, 22, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocete, R.; López, M.Á.; Gallardo, A.; Arnold, C. Comparative Analysis of Wild and Cultivated Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera) in the Basque Region of Spain and France. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2008, 123, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vecchi-Staraz, M.; Laucou, V.; Bruno, G.; Lacombe, T.; Gerber, S.; Bourse, T.; Boselli, M.; This, P. Low Level of Pollen-Mediated Gene Flow from Cultivated to Wild Grapevine: Consequences for the Evolution of the Endangered Subspecies Vitis Vinifera L. Subsp. Silvestris. Journal of Heredity 2009, 100, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, G.E.; George, E. Flora of Syria, Palestine and Sinai; from the Taurus to Ras Muhammad, and from the Mediterranean Sea to the Syrian Desert; Syrian Protestant College: Beirut, Syria, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Danin, A. Distribution Atlas of Plants in the Flora Palaestina Area; Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2004.

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M. Domestication of Plants in the Old World (Second Edition); 2008/10/03.; Cambridge University Press, 1994; Vol. 30;

- Rottenberg, A. Sex Ratio and Gender Stability in the Dioecious Plants of Israel. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 1998, 128, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislev, M.E.; Nadel, D.; Carmi, I. Epipalaeolithic (19,000 BP) Cereal and Fruit Diet at Ohalo II, Sea of Galilee, Israel. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 1992, 73, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.; Kislev, M.; Simchoni, O.; Nadel, D. Morphogenetics of Dicots and Large- and Small-Grained Wild Grasses from the Paleolithic Era (Old Stone Age) Ohalo II., Israel (23,000 Bp). In Plant Archaeogenetics; Gyulai, G., Ed.; 2011; pp. 23–30.

- Goren-Inbar, N.; Alperson, N.; Kislev, M.E.; Simchoni, O.; Melamed, Y.; Ben-Nun, A.; Werker, E. Evidence of Hominin Control of Fire at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004, 304, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, Y.; Kislev, M.E.; Geffen, E.; Lev-Yadun, S.; Goren-Inbar, N. The Plant Component of an Acheulian Diet at Gesher Benot Ya‘aqov, Israel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 14674–14679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, E.; Rahimi, O.; Marrano, A.; Henig, Y.; Brauner, H.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Netzer, Y.; Prazzoli, M.L.; Stanevsky, M.; Failla, O.; et al. Collection and Characterization of Grapevine Genetic Resources (Vitis Vinifera) in the Holy Land, towards the Renewal of Ancient Winemaking Practices. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, O.; Ohana-Levi, N.; Brauner, H.; Inbar, N.; Hübner, S.; Drori, E. Demographic and Ecogeographic Factors Limit Wild Grapevine Spread at the Southern Edge of Its Distribution Range. Ecology and Evolution 2021, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Rahimi, O.; Lavi, B.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Weiss, E.; Drori, E.; Hübner, S. Genomic Evidence Supports an Independent History of Levantine and Eurasian Grapevines. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, E.; Levy, D.; Smirin-Yosef, P.; Rahimi, O.; Salmon-Divon, M. CircosVCF: Circos Visualization of Whole-Genome Sequence Variations Stored in VCF Files. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 1392–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Duan, S.; Xia, Q.; Liang, Z.; Dong, X.; Margaryan, K.; Musayev, M.; Goryslavets, S.; Zdunić, G.; Bert, P.-F.; et al. Dual Domestications and Origin of Traits in Grapevine Evolution. Science 2023, 379, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafkafi, I. Biological Roots Dictionary. 1988.

- FAO-OIV Table and Dried Grapes; 2016; ISBN 9789251097083.

- Wolberg, S.; Haim, M.; Shtein, I. Simple Differential Staining Method with Safranin-Alcian Blue of Paraffin-Embedded Plant Sections. IAWA 2023, Submitted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. The General Theory of Natural Selection. The Clarendon Press, Oxford 1930, 272.

- Di Vecchi-Staraz, M.; Laucou, V.; Bruno, G.; Lacombe, T.; Gerber, S.; Bourse, T.; Boselli, M.; This, P. Low Level of Pollen-Mediated Gene Flow from Cultivated to Wild Grapevine: Consequences for the Evolution of the Endangered Subspecies Vitis Vinifera L. Subsp. Silvestris. Journal of Heredity 2009, 100, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Schnitzler, A.; Douard, A.; Peter, R.; Gillet, F. Is There a Future for Wild Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera Subsp. Silvestris) in the Rhine Valley? Biodiversity and Conservation 2005, 14, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, P.; Serraino, F.; Carimi, F.; Tavella, F.; Sajeva, M. Inflorescence-Visiting Insects of a Functionally Dioecious Wild Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera Subsp. Sylvestris). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2018, 65, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkafi, I. Biological Source Book for Scientific Names. (מילון שורשים ביולוגי). In; Hakkibutz Hameuchad, 1988; p. 383 (In Hebrew).

- IOV Distribution of the World’s Grapevine Varieties. In Focus OIV 2017; 2017; p. 54 ISBN 9791091799898.

- Shecori, S.; Kher, M.M.; Tyagi, K.; Lerno, L.; Netzer, Y.; Lichter, A.; Ebeler, S.E.; Drori, E. A Field Collection of Indigenous Grapevines as a Valuable Repository for Applied Research. Plants 2022, 11, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, E.; Martín-Gómez, J.J.; Espinosa-Roldán, F.E.; Muñoz-Organero, G.; Tocino, Á.; de Santamaría, F.C.S. Seed Morphology in Key Spanish Grapevine Cultivars. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaj, L.; Susaj, E.; Ferraj, B.; Dragusha, B. Identification of the Main Characters and Accompanying Plants of Wild Type Grapevine [Vitis Vinifera l. Ssp Sylvestris (Gmelin) Hegi], through Shkrelis Valley, Malësia e Madhe; 2013.

- Zito, P.; Scrima, A.; Sajeva, M.; Carimi, F.; Dötterl, S. Dimorphism in Inflorescence Scent of Dioecious Wild Grapevine. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2016, 66, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukšić, K.; Zdunić, G.; Mucalo, A.; Marinov, L.; Ranković-Vasić, Z.; Ivanović, J.; Nikolić, D. Microstructure of Croatian Wild Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera Subsp. Sylvestris Gmel Hegi) Pollen Grains Revealed by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Plants 2022, 11.

- Jovanovic-Cvetkovic, T.; Micic, N.; Djuric, G.; Cvetkovic, M. Pollen Morphology and Germination of Indigenous Grapevine Cultivars Zilavka and Blatina (Vitis Vinifera L.). Agrolife Scientific Journal 2016, 5, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M.; Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World; FOURTH; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).