Submitted:

28 July 2023

Posted:

31 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

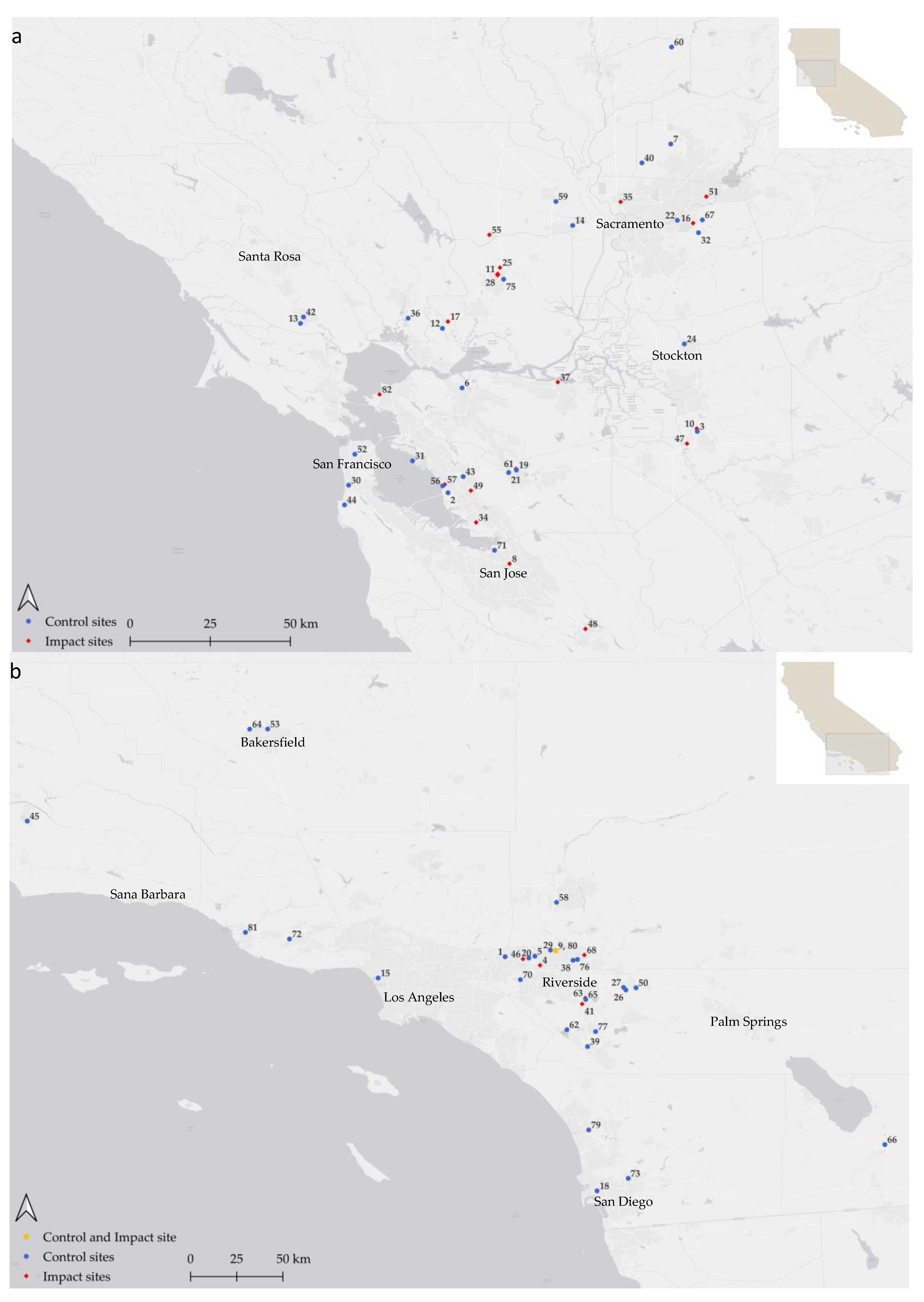

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Reconnaissance Surveys

2.3. Hypothesis Tests

2.4. Other factors

2.5. Species characteristics

3. Results

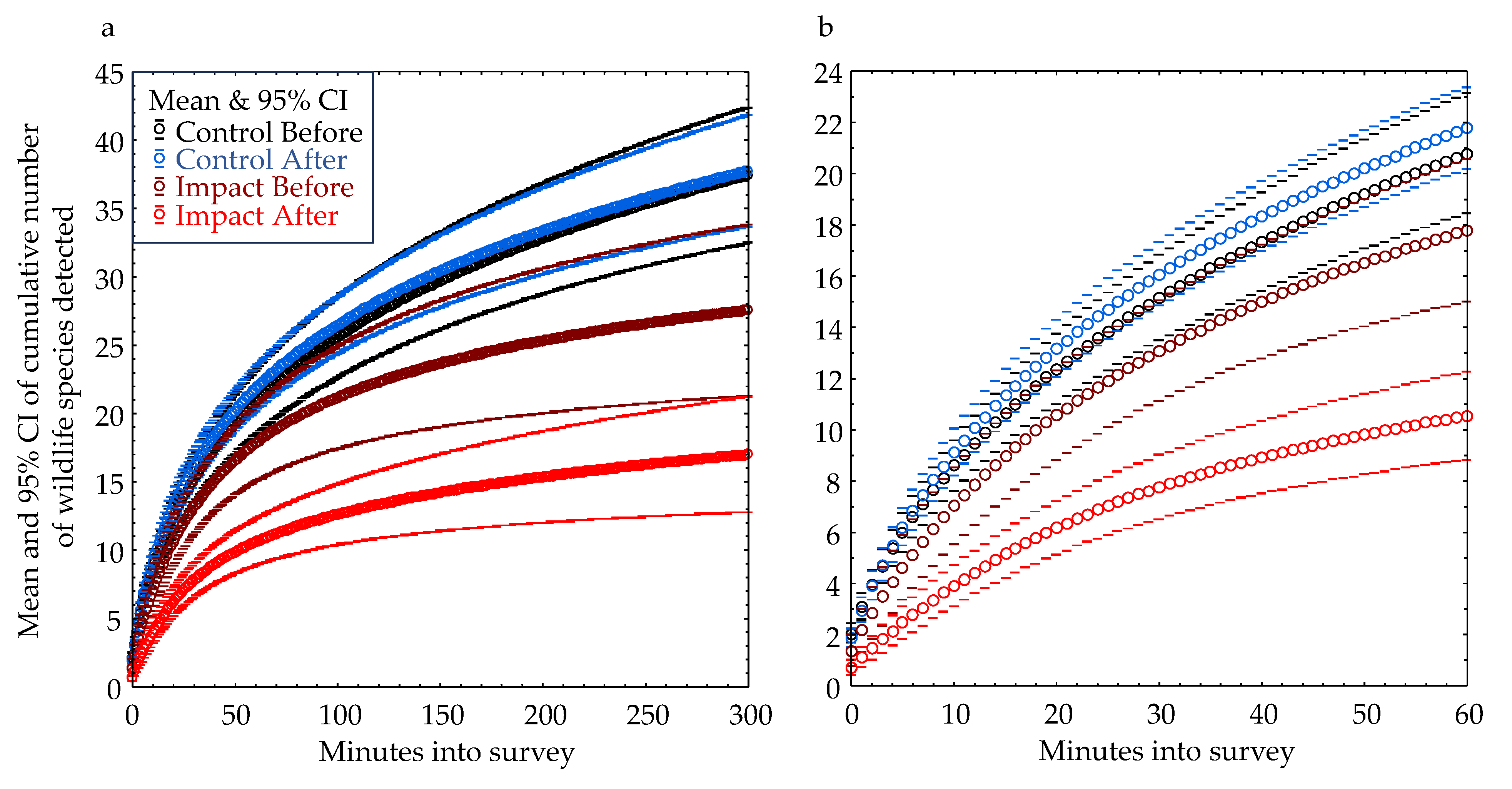

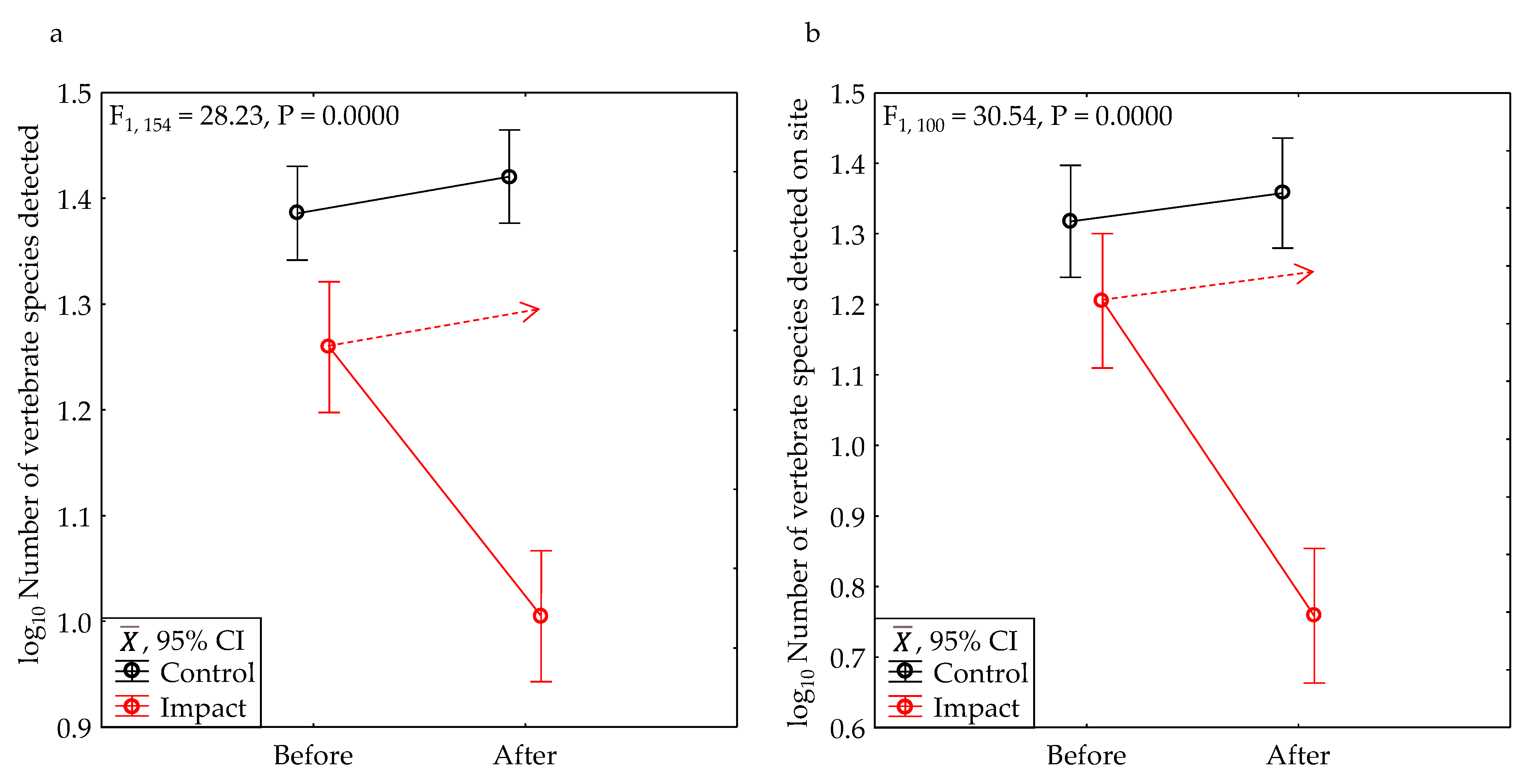

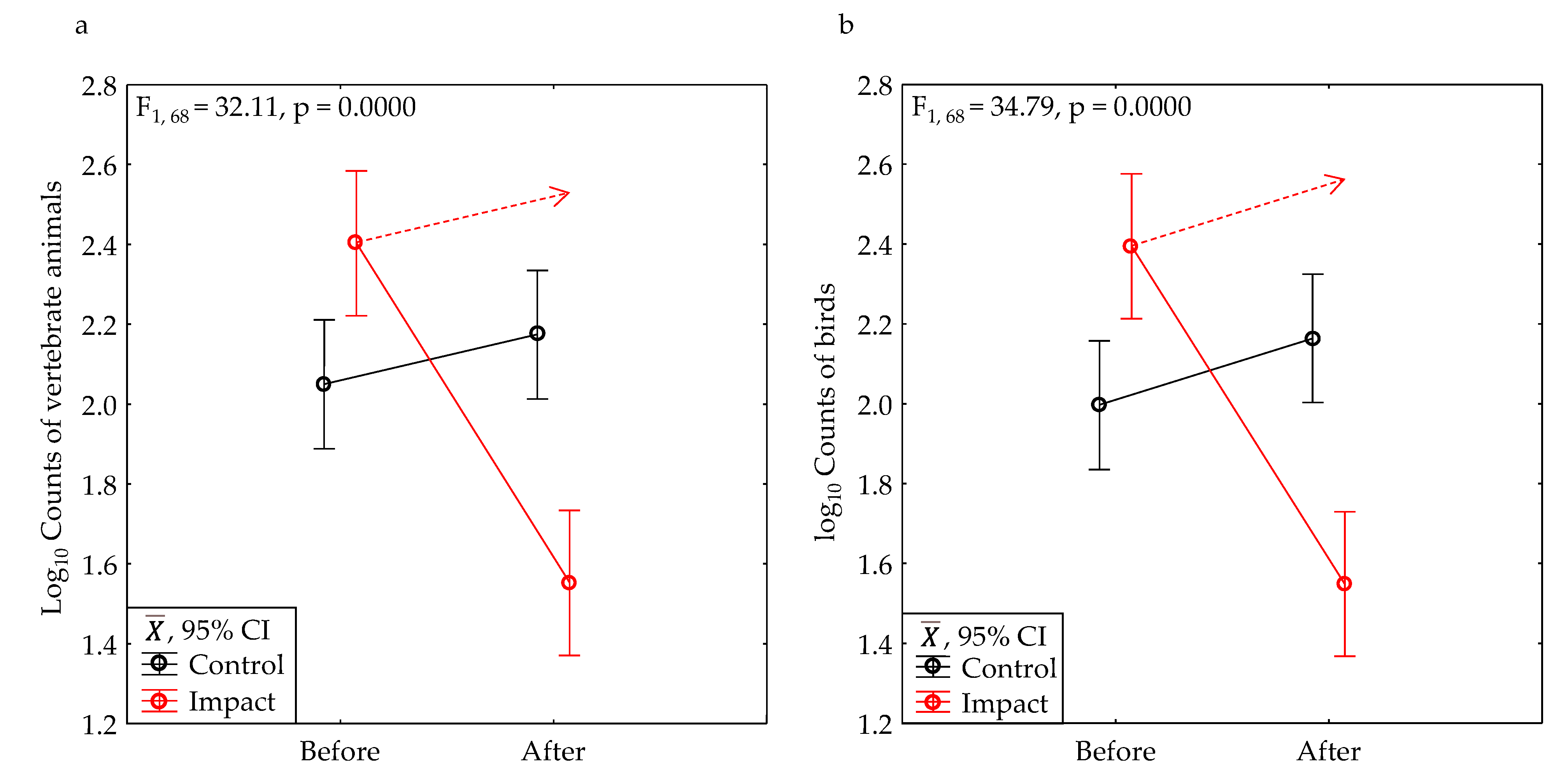

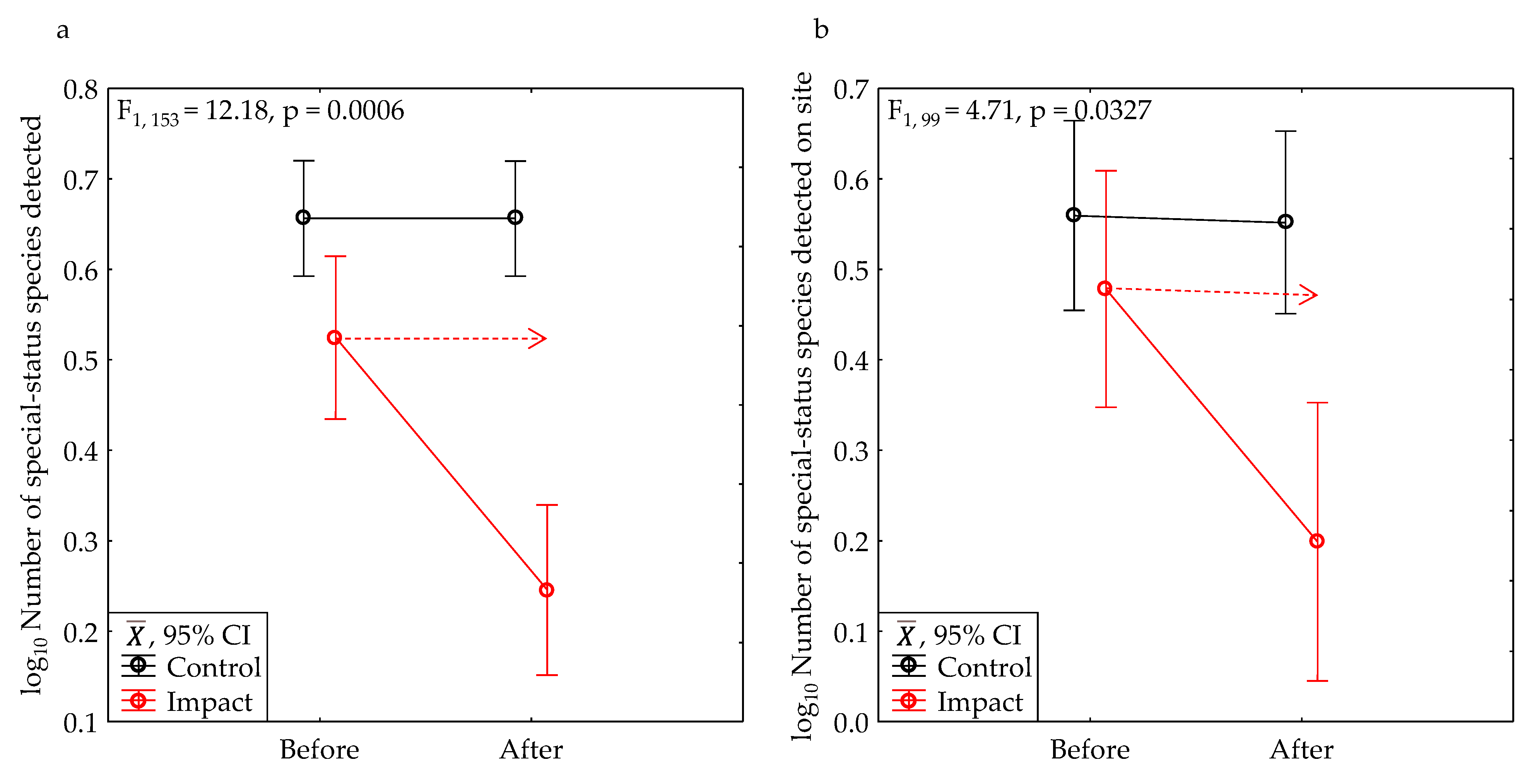

3.1. BACI Experiment

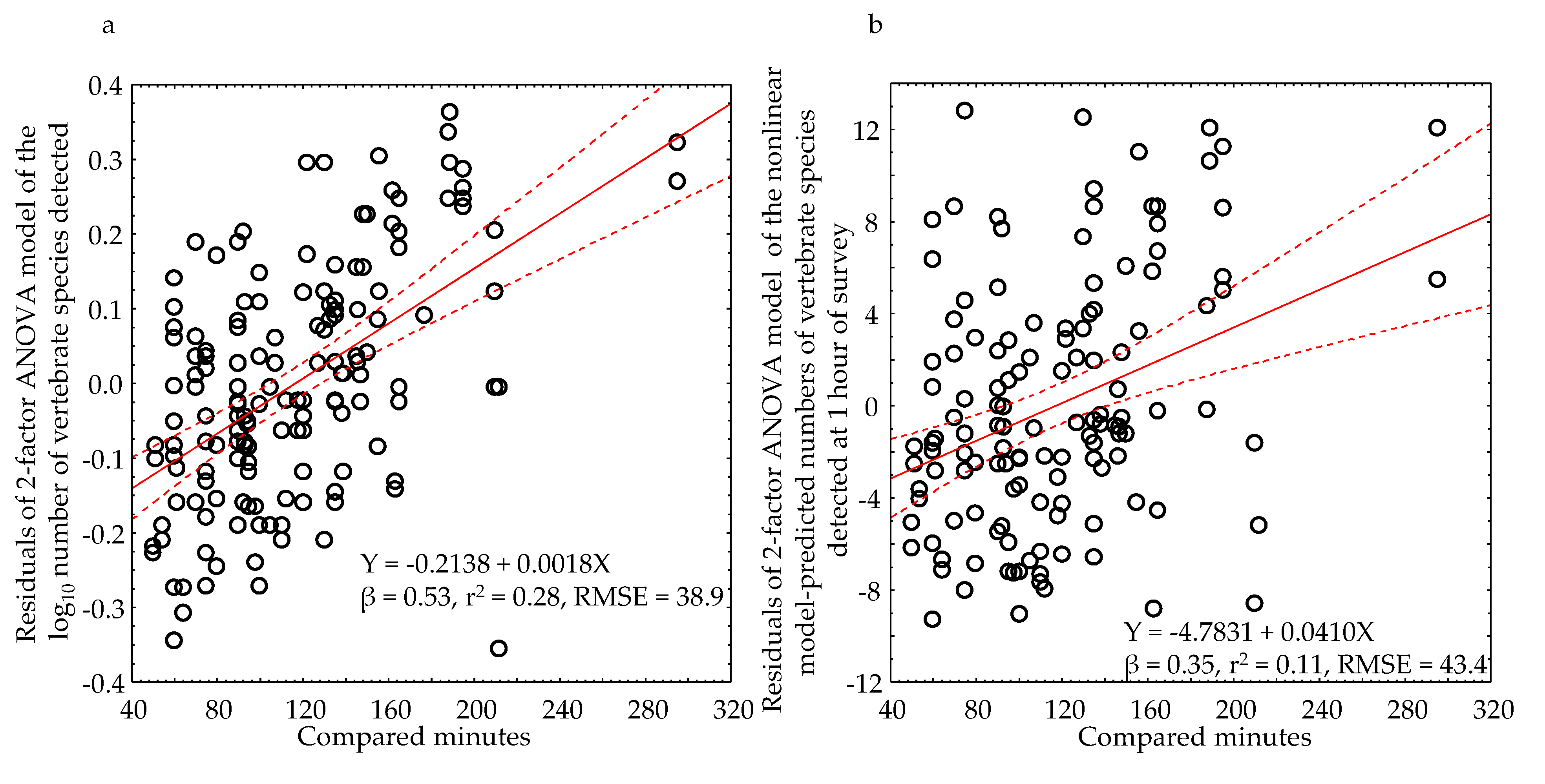

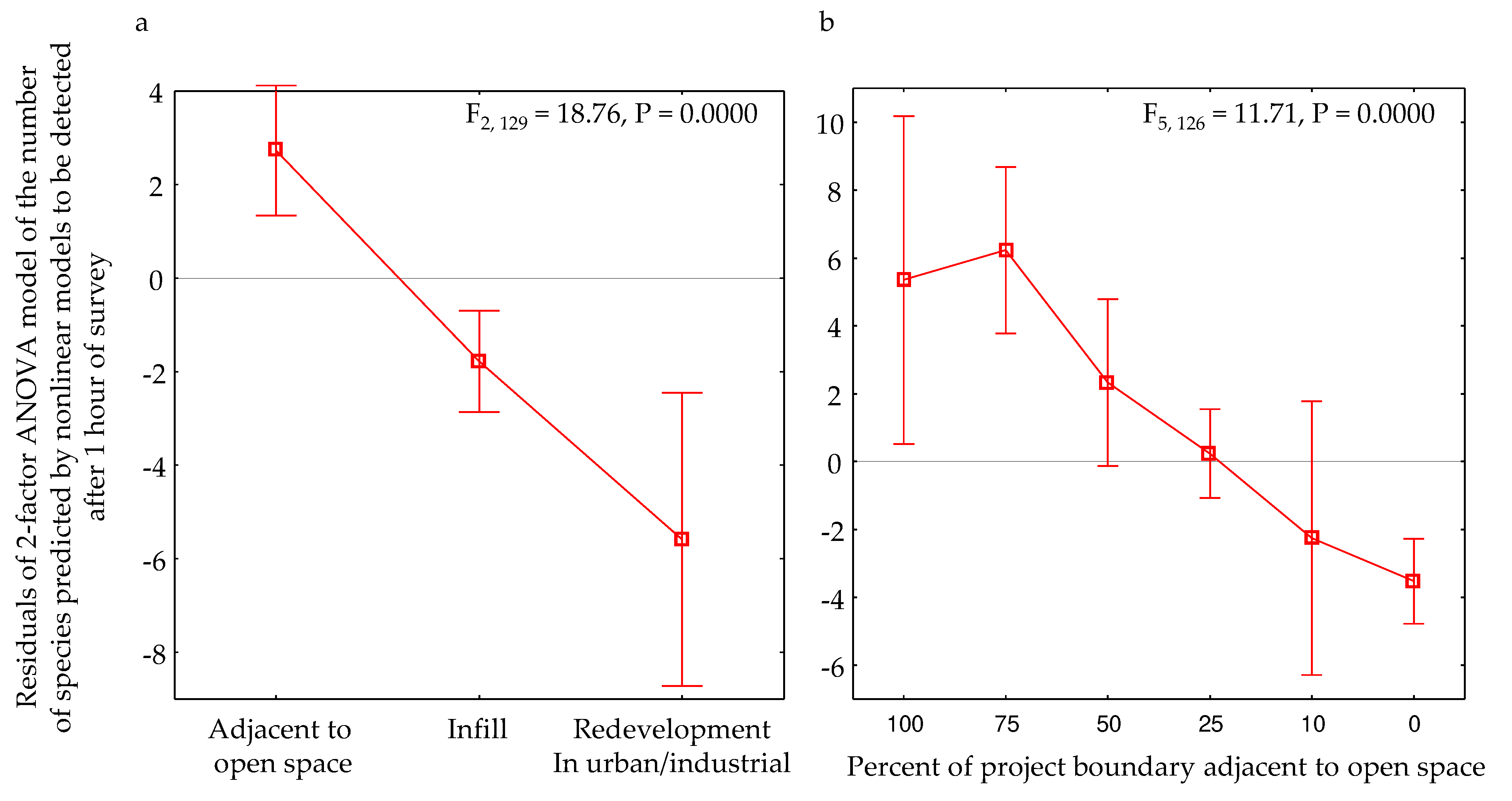

3.2. Other factors

3.3. Species characteristics

| Species | Scientific name | Type1 | Status2 | Control (n = 52) | Impact (n = 26) | Effect (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | |||||

| Abert's towhee | Melozone aberti | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Acorn woodpecker | Melanerpes formicivorus | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Alameda song sparrow | Melospiza melodia pusillula | BCC, SSC2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Allen's hummingbird | Selasphorus sasin | BCC | 9 | 10 | 0 | 0 | ||

| American avocet | Recurvirostra americanus | BCC* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| American beaver | Castor canadensis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| American bittern | Botaurus lentiginosus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| American coot | Fulica americana | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||

| American crow | Corvus brachyrhynchos | S | 41 | 38 | 24 | 21 | -6 | |

| American goldfinch | Spinus tristis | 18 | 10 | 8 | 4 | -10 | ||

| American kestrel | Falco sparverius | R | BOP | 20 | 22 | 14 | 5 | -68 |

| American pipit | Anthus rubescens | G | 4 | 9 | 1 | 0 | ||

| American robin | Turdus migratorius | 15 | 12 | 5 | 1 | -75 | ||

| American wigeon | Mareca americana | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Anna's hummingbird | Calypte anna | S | 35 | 40 | 12 | 15 | 9 | |

| Ash-throated flycatcher | Myiarchus cinerascens | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Baja California treefrog | Pseudacris hypochondriaca | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Bald eagle | Haliaeetus leucocephalus | R | CE, BGEPA, CFP | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Band-tailed pigeon | Patagioenas fasciata | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Barn swallow | Hirundo rustica | 9 | 13 | 5 | 4 | -45 | ||

| Bat sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Belted kingfisher | Ceryle alcyon | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Bewick's wren | Thryomanes bewickii | 10 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Black-chinned hummingbird | Sayornis nigricans | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Black-crowned night-heron | Nycticorax nycticorax | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Black-headed grosbeak | Archilochus alexandri | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Black-necked stilt | Nycticorax nycticorax | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Black-tailed gnatcatcher | Pheucticus melanocephalus | TWL | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Black-tailed jackrabbit | Himantopus mexicanus | 6 | 3 | 6 | 1 | -67 | ||

| Black-throated gray warbler | Polioptila melanura | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Black phoebe | Lepus californicus | S | 30 | 22 | 11 | 9 | 12 | |

| Blue-gray gnatcatcher | Passerina caerulea | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Blue grosbeak | Polioptila caerulea | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Bobcat | Felis rufus | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Botta's pocket gopher | Thomomys bottae | 24 | 31 | 8 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Brewer's blackbird | Euphagus cyanocephalus | 9 | 13 | 6 | 4 | -54 | ||

| Brewer's sparrow | Spizella breweri | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Broad-footed mole | Scapanus latimanus | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Brown-headed cowbird | Molothrus ater | 9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Bryant's Savannah sparrow | Passerculus sandwichensis alaudinus | G | SSC3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bryant's woodrat | Neotoma bryanti | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Bufflehead | Bucephala albeola | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Bullock's oriole | Icterus bullockii | BCC | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Burrowing owl | Athene cunicularia | R, G | BCC, SSC2, BOP | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | -100 |

| Bushtit | Psaltriparus minimus | 19 | 21 | 4 | 2 | -55 | ||

| Cactus wren | Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| California brown pelican | Pelicanus occidentalis californicus | CFP | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| California gnatcatcher | Polioptila c. californica | FT, SSC2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| California ground squirrel | Otospermophilus beecheyi | 18 | 24 | 8 | 0 | -100 | ||

| California gull | Larus californicus | BCC, TWL | 22 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 33 | |

| California horned lark | Eremophila alpestris actia | G | TWL | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| California quail | Callipepla californica | 6 | 10 | 3 | 0 | -100 | ||

| California scrub-jay | Aphelocoma californica | 19 | 25 | 10 | 9 | -32 | ||

| California thrasher | Toxostoma redivivum | BCC | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| California towhee | Melozone crissalis | 19 | 18 | 5 | 2 | -58 | ||

| California vole | Microtus californicus | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Calliope hummingbird | Stellula calliope | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Canada goose | Branta canadensis | 12 | 19 | 5 | 4 | -50 | ||

| Cassin's kingbird | Tyrannus vociferans | 8 | 10 | 2 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Cattle egret | Bubulcus ibis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Cedar waxwing | Bombycilla cedrorum | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Chestnut-backed chickadee | Poecile rufescens | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Chipping sparrow | Spizella passerina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Cinnamon teal | Spatula cyanoptera | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Cliff swallow | Petrochelidon pyrrhonota | 10 | 14 | 4 | 4 | -29 | ||

| Common goldeneye | Bucephala clangula | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Common ground dove | Columbina passerina | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Common merganser | Mergus merganser | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Common raven | Corvus corax | S | 33 | 34 | 11 | 10 | -12 | |

| Common yellowthroat | Geothlypis trichas | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Cooper's hawk | Accipiter cooperii | R | TWL, BOP | 13 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 73 |

| Costa's hummingbird | Calypte costae | BCC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Coyote | Canis latrans | 15 | 11 | 2 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Dark-eyed junco | Junco hyemalis | 7 | 7 | 3 | 1 | -67 | ||

| Deer mouse | Peromyscus maniculatus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Desert cottontail | Sylvilagus audubonii | 12 | 7 | 2 | 1 | -14 | ||

| Domestic dog | Canis familiaris | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Double-crested cormorant | Nannopterum auritum | TWL | 13 | 10 | 4 | 2 | -35 | |

| Downy woodpecker | Dryobates pubescens | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Eared grebe | Podiceps nigricollis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Eastern fox squirrel | Sciurus niger | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Eastern gray squirrel | Sciurus carolinensis | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | -75 | ||

| Egyptian goose | Alopochen aegyptiacus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Eurasian collared-dove | Streptopelia decaocto | S | 18 | 23 | 15 | 13 | -32 | |

| European starling | Sturnus vulgaris | S | 28 | 35 | 20 | 10 | -60 | |

| Evening grosbeak | Coccothraustes vespertinus | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Ferruginous hawk | Buteo regalis | R | TWL, BOP | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Forster's tern | Sterna forstreri | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Fox sparrow | Passerella iliaca | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Gadwall | Anas strepera | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gambel's quail | Callipepla gambelii | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Glaucous-winged gull | Larus glaucescens | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Golden eagle | Aquila chrysaetos | R | BGEPA, CFP, BOP, TWL | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Golden-crowned sparrow | Zonotrichia atricapilla | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Gopher snake | Pituophis melanoleucus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Granite spiny lizard | Sceloporus orcutti | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Grasshopper sparrow | Ammodramus savannarum | G | SSC2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gray fox | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Great Basin fence lizard | Sceloporus occidentalis longipes | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Great blue heron | Ardea herodias | 9 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Great egret | Ardea alba | 17 | 12 | 7 | 1 | -80 | ||

| Great horned owl | Bubo virginianus | R | BOP | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Greater roadrunner | Geococcyx californianus | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Greater white-fronted goose | Anser albifrons | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Greater yellowlegs | Tringa melanoleuca | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Great-tailed grackle | Quiscalus mexicanus | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Green heron | Butorides virescens | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Hairy woodpecker | Dryobates villosus | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Harbor seal | Phoca vitulina | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Herring gull | Larus argentatus | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Hooded merganser | Lophodytes cucullatus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Hooded oriole | Icterus cucullatus | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Horned grebe | Podiceps auritus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Horned lark | Eremophila alpestris | G | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | ||

| House cat | Felis catus | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 11 | ||

| House finch | Haemorphous mexicanus | S | 45 | 46 | 18 | 12 | -35 | |

| House sparrow | Passer domesticus | S | 10 | 9 | 7 | 5 | -21 | |

| House wren | Troglodytes aedon | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Hutton's vireo | Vireo huttoni | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Kangaroo rat | Dipodomys sp. | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Killdeer | Charadrius vociferus | G | 16 | 13 | 9 | 0 | -100 | |

| Large-billed savannah sparrow | Passerculus sandwichensis rostratus | SSC2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lark sparrow | Chondestes grammacus | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Lawrence's goldfinch | Spinus lawrencei | BCC | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lazuli bunting | Passerina amoena | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Least sandpiper | Calidris minutilla | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Lesser goldfinch | Spinus psaltria | S | 22 | 32 | 6 | 4 | -54 | |

| Lesser nighthawk | Chordeiles acutipennis | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Lesser scaup | Aythya affinis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Lesser yellowlegs | Tringa flaviceps | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Lincoln's sparrow | Melospiza lincolnii | 7 | 10 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Loggerhead shrike | Lanius ludovicianus | G | SSC2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | -100 |

| Long-billed curlew | Numenius americanus | TWL, BCC* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Long-tailed weasel | Mustella frenata | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| MacGillivray's warbler | Geothlypus tolmiei | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mallard | Anas platyrhynchos | 17 | 19 | 3 | 1 | -70 | ||

| Marsh wren | Cistothorus palustris | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Merlin | Falco columbarius | R | TWL, BOP | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Merriam's chipmunk | Neotamias merriami | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mew gull | Larus canus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mouse sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Mountain bluebird | Sialia currucoides | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mountain chickadee | Parus gambeli | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mountain lion | Puma concolor | CCT | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mourning dove | Zenaida macroura | S | 43 | 43 | 21 | 12 | -43 | |

| Mule deer | Odocoileus hemionus | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Muskrat | Ondatra zibethicus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mute swan | Cygnus olor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Nashville warbler | Vermivora ruficapilla | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Northern flicker | Colaptes auratus | 10 | 13 | 6 | 4 | -49 | ||

| Northern harrier | Circus hudsonius | R, G | BCC, SSC3, BOP | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 | |

| Northern mockingbird | Mimus polyglottos | S | 27 | 25 | 16 | 13 | -12 | |

| Northern pintail | Anas acuta | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Northern rough-winged swallow | Stelgidopteryx serripennis | 15 | 9 | 4 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Nutmeg mannikin | Lonchura punctulata | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Nuttall's woodpecker | Dryobates nuttallii | BCC | 8 | 15 | 1 | 1 | -47 | |

| Oak titmouse | Baeolophus inornatus | BCC | 5 | 11 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Olive-sided flycatcher | Contopus cooperi | BCC, SSC2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Orange-crowned warbler | Leiothlypis celata | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Osprey | Pandion haliaetus | R | TWL, BOP | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Pacific-slope flycatcher | Empidonax difficilis | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pacific wren | Troglodytes pacificus | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pelagic cormorant | Phalacrocorax pelagicus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Peregrine falcon | Falco peregrinus | R | CFP, BOP | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Phainopepla | Phainopepla nitens | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pied-billed grebe | Podilymbus podiceps | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Prairie falcon | Falco mexicanus | R, G | TWL, BOP | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Purple finch | Haemorhous purpureus | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Pygmy nuthatch | Sitta pygmaea | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Raccoon | Procyon lotor | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Red-breasted nuthatch | Sitta canadensis | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Red-breasted sapsucker | Sphyrapicus ruber | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Red-masked parakeet | Psittacara erythrogenys | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Red-necked phalarope | Phalaropus lobatus | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Red-shouldered hawk | Buteo lineatus | R | BOP | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1 | -42 |

| Red-tailed hawk | Buteo jamaicensis | R | BOP | 35 | 44 | 17 | 7 | -67 |

| Red-winged blackbird | Agelaius phoeniceus | 14 | 16 | 6 | 1 | -85 | ||

| Red fox | Vulpes vulpes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ring-billed gull | Larus delawarensis | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ring-necked pheasant | Phasianus colchicus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Rock pigeon | Columba livia | S | Non-native | 21 | 31 | 18 | 15 | -44 |

| Rose-ringed parakeet | Psittacula krameri | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ruby-crowned kinglet | Regulus calendula | 6 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 50 | ||

| Ruddy duck | Oxyura jamaicensis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Rufous hummingbird | Selasphorus rufus | BCC | 1 | 0 | ||||

| San Diegan tiger whiptail | Aspidoscelis tigris stejnegeri | SSC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| San Francisco common yellowthroat | Geothlypis trichas sinuosa | BCC, SSC3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| San Francisco dusky-footed woodrat | Neotoma fuscipes annectens | SSC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Savannah sparrow | Passerculus sandwichensis | G | 13 | 14 | 5 | 2 | -63 | |

| Say's phoebe | Sayornis saya | G | 21 | 15 | 6 | 4 | -7 | |

| Sharp-shinned hawk | Accipiter striatus | R | TWL, BOP | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Short-billed dowitcher | Limnodromus griseus | BCC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Short-eared owl | Asio flammeus | R | BCC, SSC3, BOP | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Side-blotched lizard | Uta stansburiana | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sierran treefrog | Pseudacris sierra | 3 | 9 | 1 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Snow goose | Chen caerulescens | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Snowy egret | Egretta thula | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Song sparrow | Melospiza melodia | 13 | 15 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sora | Porzana carolina | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Southern alligator lizard | Gerrhonotus multicarinatus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Southern California rufous-crowned sparrow | Aimophila ruficeps canescens | TWL | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Southern mule deer | Odocoileus hemionus fuliginatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Southern Pacific rattlesnake | Crotalus oreganus helleri | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Southern sagebrush lizard | Sceloporus graciosus vandenburgianus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Spotted sandpiper | Actitis macularius | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Spotted towhee | Pipilo maculatus | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Steller's jay | Cyanocitta stelleri | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Striped skunk | Mephitis mephitis | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Surf scoter | Melanitta perspicillata | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Swainson's hawk | Buteo swainsoni | R | CT, BOP | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | -44 |

| Swainson's thrush | Catharus ustulatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Townsend's warbler | Setophaga townsendi | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Tree swallow | Tachycineta bicolor | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Tricolored blackbird | Agelaius tricolor | G | CT, BCC, SSC1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tundra swan | Cygnus columbianus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Turkey vulture | Cathartes aura | R | BOP | 17 | 21 | 11 | 7 | -49 |

| Vaux's swift | Chaetura vauxi | SSC2, BCC | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Verdin | Auriparus flaviceps | BCC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Vermilion flycatcher | Pyrocephalus rubinus | G | SSC2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Violet-green swallow | Tachycineta thalassina | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Virginia opossum | Didelphis virginianus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Warbling vireo | Vireo gilvus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Western bluebird | Sialia mexicana | 9 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Western fence lizard | Sceloporus occidentalis | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | -83 | ||

| Western gray squirrel | Sciurus griseus | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Western gull | Larus occidentalis | BCC | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | -67 | |

| Western kingbird | Tyrannus verticalis | 10 | 9 | 4 | 2 | -44 | ||

| Western meadowlark | Sturnella neglecta | G | 18 | 23 | 11 | 2 | -86 | |

| Western sandpiper | Calidris mauri | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Western screech-owl | Megascops kennicottii | R | BOP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Western side-blotched lizard | Uta stansburiana elegans | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Western tanager | Piranga ludoviciana | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| White-breasted nuthatch | Sitta carolinensis | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| White-crowned sparrow | Zonotrichia leucophrys | 17 | 23 | 9 | 4 | -67 | ||

| White-faced ibis | Plegadis chihi | TWL | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

| White-tailed kite | Elanus leucurus | R | CFP, BOP | 14 | 7 | 7 | 0 | -100 |

| White-throated swift | Aeronautes saxatalis | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | -100 | ||

| White-winged dove | Zenaida asiatica | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Wild turkey | Meleagris gallopavo | 6 | 7 | 2 | 0 | -100 | ||

| Willet | Tringa semipalmata | BCC | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Willow flycatcher | Empidonax traillii | CE | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Wilson's snipe | Gallinago delicata | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Wilsons warbler | Wilsonia pusilla | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Wood duck | Aix sponsa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Wrentit | Chamaea fasciata | BCC | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Yellow-billed magpie | Setophaga petechia | BCC | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | -100 | |

| Yellow-headed blackbird | Pica nuttalli | G | SSC3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Yellow-rumped warbler | Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus | S | 21 | 21 | 7 | 10 | 43 | |

| Yellow warbler | Setophaga coronata | SSC2 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | ||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Project site and survey attributes.

| Pair | Treatment level | Phase | Survey minutes compared | Project | Location | Proposed Use | Survey date | Start time | Ha | Conditions on the ground |

| 1 | Control | Before | 64 | 11th Street Development | Upland | Warehouse | 11/8/2020 | 6:40 | 1.98 | Ruderal scrub around old cement pad |

| 1 | Control | After | 64 | 11th Street Development | Upland | Warehouse | 11/24/2021 | 6:43 | 1.98 | Same as above |

| 2 | Control | Before | 135 | 4150 Point Eden Way Industrial Development | Hayward | Warehouse | 5/11/2021 | 6:40 | 4.37 | Grassland bounded by salt ponds including those of Eden Landing Reserve, CA Highway 92, and industrial warehouses |

| 2 | Control | After | 135 | 4150 Point Eden Way Industrial Development | Hayward | Warehouse | 5/10/2022 | 7:12 | 4.37 | Same as above |

| 3 | Control | Before | 135 | Airport Business Centre | Manteca | Warehouse | 4/28/2021 | 16:17 | 9.51 | Mowed hay bordered on north by warehouses |

| 3 | Control | After | 135 | Airport Business Centre | Manteca | Warehouse | 3/28/2022 | 16:31 | 9.51 | Unmowed hay bordered north and west by warehouse |

| 4 | Impact | Before | 50 | Almond Street Warehouse | Fontana | Warehouse | 4/27/2019 | 9:25 | 4.05 | Former parking lot with ornamental trees |

| 4 | Impact | After | 50 | Almond Street Warehouse | Fontana | Warehouse | 4/25/2022 | 8:50 | 4.05 | Warehouse |

| 5 | Control | Before | 105 | Alta Cuvee | Rancho Cucamonga | Residential | 9/4/2021 | 6:54 | 2.55 | Highly disturbed dirt field with low shrubs and nonnative grass |

| 5 | Control | After | 105 | Alta Cuvee | Rancho Cucamonga | Residential | 8/30/2022 | 7:04 | 2.55 | Same as above |

| 6 | Control | Before | 163 | Amare Apartments | Martinez | Residential | 6/4/2018 | 17:17 | 2.45 | Disked woodland savannah |

| 6 | Control | After | 163 | Amare Apartments | Martinez | Residential | 7/19/2021 | 17:07 | 2.45 | Same as above |

| 7 | Control | Before | 130 | Antonio Mountain Ranch | Placer County | Residential | 11/18/2002 | 14:30 | 359.00 | Grassland/vernal pool complex with riparian |

| 7 | Control | After | 130 | Antonio Mountain Ranch | Placer County | Residential | 11/16/2021 | 14:45 | 359.00 | Same as above |

| 8 | Impact | Before | 135 | Brokaw Campus | San Jose | Corporate Campus | 11/16/2018 | 12:45 | 6.78 | Disked with ruderal cover |

| 8 | Impact | After | 135 | Brokaw Campus | San Jose | Corporate Campus | 10/30/2021 | 12:42 | 6.78 | Four tall buildings |

| 9 | Control | Before | 80 | Casmalia & Linden | Rialto | Warehouse | 6/21/2020 | 6:10 | 2.77 | Grassland and shrubs |

| 9 | Control | After | 80 | Casmalia & Linden | Rialto | Warehouse | 7/31/2021 | 6:12 | 2.77 | Grassland and shrubs |

| 10 | Impact | Before | 94 | CenterPoint | Manteca | Warehouse | 10/31/2018 | 16:15 | 9.12 | Ruderal vegetation subsequent to grading |

| 10 | Impact | After | 94 | CenterPoint | Manteca | Warehouse | 11/11/2021 | 15:26 | 9.12 | Warehouse with parking lot |

| 11 | Impact | Before | 100 | Cessna & Aviator Warehouse | Vacaville | Warehouse | 8/12/2018 | 18:00 | 5.21 | Disked annual grassland |

| 11 | Impact | After | 100 | Cessna & Aviator Warehouse | Vacaville | Warehouse | 8/31/2022 | 18:07 | 5.21 | Warehouse and parking lot |

| 12 | Control | Before | 95 | Cordelia Industrial | Cordelia | Warehouse | 10/16/2019 | 15:54 | 13.11 | Disked annual grassland with some regrowth next to riparian |

| 12 | Control | After | 95 | Cordelia Industrial | Cordelia | Warehouse | 10/7/2021 | 12:38 | 13.11 | Disked annual grassland next to riparian; new houses on west side |

| 13 | Control | Before | 165 | Davidon Homes | Petaluma | Residential | 2/11/2021 | 7:41 | 23.74 | Grassland and riparian oak woodland |

| 13 | Control | After | 165 | Davidon Homes | Petaluma | Residential | 3/1/2022 | 7:33 | 23.74 | Same as above |

| 14 | Control | Before | 54 | Aggie Research Campus | Davis | Residential | 4/13/2020 | 18:39 | 74.90 | Planted sugarbeets, wheat, almonds |

| 14 | Control | After | 54 | Aggie Research Campus | Davis | Residential | 4/2/2022 | 18:33 | 74.90 | Wheat, dirt furrows, planted sugarbeets |

| 15 | Control | Before | 93 | Del Rey Pointe Residential Project | Playa Del Rey | Residential | 10/31/2019 | 14:07 | 1.16 | Ruderal vegetation bordered by Eucalyptus and 3 concrete-lined streams |

| 15 | Control | After | 93 | Del Rey Pointe Residential Project | Playa Del Rey | Residential | 10/18/2021 | 13:54 | 1.16 | Ruderal vegetation undergoing clearing by tractor; bordered by Eucalyptus and 3 concrete-lined streams |

| 16 | Impact | Before | 122 | GLP Store | Mather | Warehouse | 2/12/2020 | 6:56 | 3.76 | Annual grassland |

| 16 | Impact | After | 122 | GLP Store | Mather | Warehouse | 2/18/2022 | 7:09 | 3.76 | Warehouse |

| 17 | Impact | Before | 90 | Green Valley II | Fairfield | Residential | 11/18/2019 | 9:00 | 5.39 | Disked grassland with 1 oak and bordered by shrubs |

| 17 | Impact | After | 90 | Green Valley II | Fairfield | Residential | 12/7/2021 | 9:47 | 5.39 | Nearly built warehouse and apartments |

| 18 | Control | Before | 120 | Hillcrest LRDP | Bachman Canyon | None | 11/9/2019 | 7:00 | 12.95 | Diegan coastal sage scrub |

| 18 | Control | After | 120 | Hillcrest LRDP | Bachman Canyon | None | 12/11/2021 | 7:11 | 12.95 | Same as above |

| 19 | Control | Before | 90 | IKEA Outlet | Dublin | Warehouse retail | 3/26/2018 | 11:15 | 11.11 | Ruderal & annual grassland |

| 19 | Control | After | 90 | IKEA Outlet | Dublin | Warehouse retail | 3/25/2022 | 9:53 | 11.11 | Ruderal & annual grassland; tractors and trucks on site, and about 15% to 20% is graded |

| 20 | Control | Before | 110 | Jersey Industrial Complex | Rancho Cucamonga | Warehouse | 6/16/2021 | 6:26 | 2.99 | Ruderal vegetation on disturbed soil, surrounded by warehouses and major roads and railroad tracks |

| 20 | Control | After | 110 | Jersey Industrial Complex | Rancho Cucamonga | Warehouse | 7/11/2022 | 6:30 | 2.99 | Previously disked, non-native grass present, surrounded by warehouses and major roads and railroad tracks |

| 21 | Control | Before | 120 | Johnson Drive Economic Zone | Pleasanton | Warehouse retail, hotel | 7/29/2019 | 17:38 | 16.19 | Mix of developed structures, vacant lots, and grassland |

| 21 | Control | After | 120 | Johnson Drive Economic Zone | Pleasanton | Warehouse retail, hotel | 7/26/2021 | 17:46 | 16.19 | Same as above |

| 22 | Control | Before | 195 | Kassis | Rancho Cordova | Residential | 12/3/2020 | 7:47 | 16.51 | Disked grassland and abandoned walnuts |

| 22 | Control | After | 195 | Kassis | Rancho Cordova | Residential | 11/2/2021 | 7:39 | 16.51 | Same as above |

| 24 | Control | Before | 70 | Lake Home | Lodi | Residential | 3/13/2019 | 8:28 | 3.56 | Abandoned orchard |

| 24 | Control | After | 70 | Lake Home | Lodi | Residential | 3/25/2022 | 7:26 | 3.56 | Same as above |

| 25 | Impact | Before | 92 | LDK Warehouse | Vacaville | Warehouse | 11/10/2018 | 7:50 | 27.88 | Disked annual grassland, riparian |

| 25 | Impact | After | 92 | LDK Warehouse | Vacaville | Warehouse | 11/13/2021 | 7:53 | 27.88 | Operational warehouse and nearly completed empty warehouse |

| 26 | Control | Before | 127 | Legacy Highlands | Beaumont, upper | Residential | 5/4/2021 | 17:39 | 647.50 | Sage scrub |

| 26 | Control | After | 127 | Legacy Highlands | Beaumont, upper | Residential | 4/24/2022 | 17:34 | 647.50 | Sage scrub |

| 27 | Control | Before | 189 | Legacy Highlands | Beaumont, lower | Residential | 5/5/2021 | 6:02 | 647.50 | Riparian, grassland, sage scrub |

| 27 | Control | After | 189 | Legacy Highlands | Beaumont, lower | Residential | 4/26/2022 | 6:02 | 647.50 | Riparian, grassland, sage scrub |

| 28 | Impact | Before | 90 | Logisticenter at Vacaville | Vacaville | Warehouse | 9/1/2018 | 7:50 | 5.68 | Disked annual grassland |

| 28 | Impact | After | 90 | Logisticenter at Vacaville | Vacaville | Warehouse | 9/5/2021 | 7:48 | 5.68 | Warehouse surrounded by warehouses on 3 sides, disked on 4th side |

| 29 | Control | Before | 100 | Mango Avenue | Fontana | Warehouse | 1/24/2021 | 7:33 | 2.35 | Ruderal grassland |

| 29 | Control | After | 100 | Mango Avenue | Fontana | Warehouse | 2/13/2022 | 7:25 | 2.35 | Ruderal grassland |

| 30 | Control | Before | 112 | Vista Mar | Pacifica | Residential | 8/20/2020 | 6:59 | 0.53 | Trees, shrubs, grassland |

| 30 | Control | After | 112 | Vista Mar | Pacifica | Residential | 9/15/2021 | 7:17 | 0.53 | Trees, shrubs, grassland |

| 31 | Control | Before | 75 | Marriott Hotel | Harbor Bay Parkway, Alameda | Hotel | 11/16/2018 | 15:18 | 2.23 | Ruderal cover on disked field lined by trees |

| 31 | Control | After | 75 | Marriott Hotel | Harbor Bay Parkway, Alameda | Hotel | 10/30/2021 | 14:54 | 2.23 | Same as above |

| 32 | Control | Before | 188 | Mather South Masterplan | Mather | Residential | 2/16/2019 | 8:02 | 343.17 | Annual grassland, wetland, riparian |

| 32 | Control | After | 188 | Mather South Masterplan | Mather | Residential | 2/6/2022 | 7:20 | 343.17 | Same as above |

| 33 | Impact | Before | 145 | Monte Vista Warehouse | Vacaville | Warehouse | 6/23/2019 | 6:48 | 4.67 | Disked grassland with volunteer shrubs/trees |

| 33 | Impact | After | 145 | Monte Vista Warehouse | Vacaville | Warehouse | 6/16/2021 | 6:48 | 4.67 | Nearly completely constructed warehouse; field to west under construction wtih pad |

| 34 | Impact | Before | 70 | Morton Salt Plant | Newark | Warehouse | 5/8/2018 | 16:58 | 12.10 | Abandoned salt ponds |

| 34 | Impact | After | 70 | Morton Salt Plant | Newark | Warehouse | 6/3/2021 | 16:20 | 12.10 | Warehouses next to row of Eucalyptus |

| 35 | Impact | Before | 75 | Natomas Crossing | Natomas | Commercial | 6/30/2018 | 19:00 | 27.60 | Feral grassland on disked soil |

| 35 | Impact | After | 75 | Natomas Crossing | Natomas | Commercial | 6/9/2021 | 18:30 | 27.60 | New buildings and parking lots; field to east was disked |

| 36 | Control | Before | 90 | Nova Business Park | Napa | Warehouse | 7/15/2018 | 18:50 | 9.39 | Annual grassland and riparian forest |

| 36 | Control | After | 90 | Nova Business Park | Napa | Warehouse | 7/14/2021 | 18:19 | 9.39 | Annual grassland and riparian forest, but early grading for project over past month or two and lots of development in surrounding area |

| 37 | Impact | Before | 70 | Oakley Logistics Center | Oakley | Warehouse | 11/22/2019 | 8:04 | 152.04 | Marsh, grassland, riparian, disturbed |

| 37 | Impact | After | 70 | Oakley Logistics Center | Oakley | Warehouse | 12/7/2021 | 7:55 | 152.04 | Warehouses and parking lots |

| 38 | Control | Before | 90 | Olympic Holding Inland Center | San Bernardino | Warehouse | 12/1/2019 | 8:18 | 2.12 | Barren ground and ruderal vegetation lined by trees |

| 38 | Control | After | 90 | Olympic Holding Inland Center | San Bernardino | Warehouse | 12/6/2021 | 8:24 | 2.12 | Barren ground and ruderal vegetation lined by trees |

| 39 | Control | Before | 75 | PARS Global Storage | Murietta | Warehouse | 10/31/2019 | 10:06 | 1.28 | Shrubs, grass, trees |

| 39 | Control | After | 75 | PARS Global Storage | Murietta | Warehouse | 10/19/2021 | 10:02 | 1.28 | Shrubs, grass, trees |

| 40 | Control | Before | 177 | Regional University | Roseville | University | 1/15/2008a | 16:10a | 468.42 | Annual grasslands, vernal pools |

| 40 | Control | After | 165 | Regional University | Roseville | University | 1/12/2022a | 15:13a | 468.42 | Annual grasslands, vernal pools |

| 41 | Impact | Before | 150 | Rider Warehouse | Perris | Warehouse | 7/22/2019 | 6:55 | 3.89 | Disked annual grassland |

| 41 | Impact | After | 150 | Rider Warehouse | Perris | Warehouse | 3/28/2021 | 6:50 | 3.89 | Warehouse |

| 42 | Control | Before | 138 | Clover Project | Petaluma | Residential | 7/13/2020 | 17:24 | 1.36 | Grassland with a few mature trees, next to Petaluma River |

| 42 | Control | After | 138 | Clover Project | Petaluma | Residential | 7/22/2021 | 17:30 | 1.36 | Grassland with a few mature trees, next to Petaluma River |

| 43 | Control | Before | 135 | Ruby Street | Castro Valley | Multi-family housing | 10/17/2020 | 7:23 | 2.55 | Grass meadow next to riparian forest of San Lorenzo Creek and otherwise surrounded by residential |

| 43 | Control | After | 135 | Ruby Street | Castro Valley | Multi-family housing | 9/10/2021 | 7:40 | 2.55 | Grass meadow next to riparian forest of San Lorenzo Creek and otherwise surrounded by residential |

| 44 | Control | Before | 295 | San Pedro Mountain | Pacifica | Residential | 6/3/2021 | 6:00 | 9.45 | Eucalyptus/Monterey Pine forest and Coyote bush scrub |

| 44 | Control | After | 295 | San Pedro Mountain | Pacifica | Residential | 6/6/2022 | 6:36 | 9.45 | Eucalyptus/Monterey Pine forest and Coyote bush scrub |

| 45 | Control | Before | 60 | Santa Maria Airport Business Park | Santa Maria | Office complex | 4/9/2021 | 7:14 | 11.33 | Strawberries with Eucalyptus woodland border |

| 45 | Control | After | 60 | Santa Maria Airport Business Park | Santa Maria | Office complex | 5/11/2022 | 8:03 | 11.33 | Strawberries with Eucalyptus woodland border |

| 46 | Impact | Before | 60 | Scheu Warehouse | Rancho Cucamongo | Warehouse | 10/31/2019 | 8:02 | 5.35 | Mowed grassland |

| 46 | Impact | After | 60 | Scheu Warehouse | Rancho Cucamonga | Warehouse | 10/19/2021 | 8:07 | 5.35 | Warehouse with dirt mound on west side |

| 47 | Impact | Before | 61 | Seefried Warehouse | Lathrop | Warehouse | 11/20/2019 | 8:23 | 4.65 | Disked grassland |

| 47 | Impact | After | 61 | Seefried Warehouse | Lathrop | Warehouse | 11/17/2021 | 9:44 | 4.65 | Warehouse and parking lot |

| 48 | Impact | Before | 100 | Shoe Palace | Morgan Hill | Warehouse | 11/16/2018 | 9:45 | 15.40 | Annual grassland |

| 48 | Impact | After | 100 | Shoe Palace | Morgan Hill | Warehouse | 10/30/2021 | 10:15 | 15.40 | Warehouse and parking lot with strip of planted shrubs |

| 49 | Impact | Before | 60 | South Hayward | Hayward | Residential | 4/14/2018 | 17:00 | 10.42 | Annual grass either side of water channel |

| 49 | Impact | After | 60 | South Hayward | Hayward | Residential | 6/3/2021 | 18:06 | 10.42 | Residential development either side of water channel |

| 50 | Control | Before | 165 | Sun Lakes Village North | Banning | Warehouse | 11/9/2020 | 7:15 | 19.03 | Annual grassland with willow patch and buckwheat scrub |

| 50 | Control | After | 165 | Sun Lakes Village North | Banning | Warehouse | 11/23/2021 | 6:55 | 19.03 | Annual grassland with willow patch and buckwheat scrub |

| 51 | Impact | Before | 90 | The Promenade | Carmichael | Commercial | 10/1/2002 | 9:25 | 4.13 | Woodland savannah |

| 51 | Impact | After | 90 | The Promenade | Carmichael | Commercial | 10/13/2021 | 9:22 | 4.13 | Commercial strip/parking lots |

| 52 | Control | Before | 210 | UCSF Parnassus Campus and Sutro Park | San Francisco | University expansion | 8/20/2020 | 8:17 | 67.99 | Campus; forested |

| 52 | Control | After | 210 | UCSF Parnassus Campus and Sutro Park | San Francisco | University expansion | 7/16/2021 | 9:14 | 67.99 | Campus; forested |

| 53 | Control | Before | 110 | Veterans Affairs Clinic | Bakersfield | VA Clinic | 1/20/2021 | 8:00 | 4.07 | Recently burned annual grassland |

| 53 | Control | After | 110 | Veterans Affairs Clinic | Bakersfield | VA Clinic | 1/11/2022 | 7:21 | 4.07 | Annual grassland |

| 55 | Impact | Before | 150 | Winter's Highlands & Callahan Estates | Winters | Residential | 5/18/2004 | 9:20 | 60.70 | Annual grassland |

| 55 | Impact | After | 150 | Winter's Highlands & Callahan Estates | Winters | Residential | 6/11/2021 | 9:04 | 60.70 | Residential |

| 56 | Control | Before | 75 | Hayward Regional Shoreline | Hayward | None | 1/31/2018 | 14:45 | 734.50 | Coastal scrub and wetlands |

| 56 | Control | After | 75 | Hayward Regional Shoreline | Hayward | None | 1/23/2022 | 14:50 | 734.50 | Coastal scrub and wetlands |

| 57 | Impact | Before | 75 | Winton Ave Industrial Project | Hayward | Warehouse | 1/31/2018 | 14:45 | 9.47 | Vacant lot with old concrete pads surrounded by ruderal vegetation |

| 57 | Impact | After | 75 | Winton Ave Industrial Project | Hayward | Warehouse | 1/23/2022 | 16:07 | 9.47 | Warehouse |

| 59 | Control | Before | 107 | Woodland Research Park | South of Woodland | Residential | 6/30/2021 | 18:04 | 156.61 | Agricultural field crops and woodland/savannah between residential and Highway 113 |

| 59 | Control | After | 107 | Woodland Research Park | South of Woodland | Residential | 7/13/2022 | 17:56 | 156.61 | Agricultural field crops and woodland/savannah between residential and Highway 113 |

| 60 | Control | Before | 155 | Yuba Highlands | Spenceville WMRA | Residential | 11/12/2006 | 13:00 | 1174.40 | Annual grassland, oak woodland, riparian; east of proposed project |

| 60 | Control | After | 155 | Yuba Highlands | Spenceville WMRA | Residential | 11/20/2021 | 13:55 | 1174.40 | Annual grassland, oak woodland, riparian |

| 61 | Impact | Before | 60 | Zeiss Innovation Center | Dublin | Office commercial | 2/8/2018 | 10:50 | 4.60 | Annual grassland |

| 61 | Impact | After | 60 | Zeiss Innovation Center | Dublin | Office commercial | 2/3/2021 | 10:38 | 4.60 | Mid-rise buildings and parking lots nearly completed |

| 62 | Control | Before | 133 | Fairway Business Park | Lake Elsinore | Warehouse | 12/1/2021 | 7:12 | 3.56 | Nonnative grassland and ruderal shrubs |

| 62 | Control | After | 133 | Fairway Business Park | Lake Elsinore | Warehouse | 12/8/2022 | 7:15 | 3.56 | Annual grass and shrubs, and mule fat and salt cedar |

| 63 | Impact | Before | 51 | First Industrial Logistics Center II | Moreno Valley | Warehouse | 2/28/2020 | 13:25 | 3.93 | Ruderal grassland with piles of dirt and debris from neighboring development |

| 63 | Impact | After | 51 | First Industrial Logistics Center II | Moreno Valley | Warehouse | 2/5/2023 | 13:25 | 3.93 | Warehouse landscaped with low shrubs and ornamental trees |

| 64 | Control | Before | 118 | Hagemon | Bakersfield | Warehouse | 1/9/2022 | 15:20 | 31.95 | Annual grassland that had been disked within last few years |

| 64 | Control | After | 118 | Hagemon | Bakersfield | Warehouse | 2/4/2023 | 15:32 | 31.95 | Annual grassland that had been disked again recently |

| 65 | Control | Before | 98 | Operon HKI | Perris | Warehouse | 11/21/2021 | 7:03 | 3.52 | Mowed grassland surrounded by warehouses |

| 65 | Control | After | 98 | Operon HKI | Perris | Warehouse | 12/9/2022 | 7:22 | 3.52 | Annual grass and prickly Russian thistle surrounded by warehouses |

| 66 | Control | Before | 162 | Brawley Solar Energy Facility | Brawley | Utility-scale solar | 2/4/2022 | 6:52 | 91.86 | Alfalfa, ruderal, Atriplex, Tamarisk and Sueda along railroad tracks |

| 66 | Control | After | 162 | Brawley Solar Energy Facility | Brawley | Utility-scale solar | 2/22/2023 | 6:22 | 91.86 | Alfalfa, ruderal, Atriplex, Tamarisk and Sueda along railroad tracks |

| 67 | Control | Before | 210 | Rio Del Oro | Rancho Cordova | Residential | 5/25/2008b | 19:30b | 1549.14 | Annual grassland, wetland, oak woodland |

| 67 | Control | After | 208 | Rio Del Oro | Rancho Cordova | Residential | 6/13/2021b | 18:58b | 1549.14 | Same as above, but bordered by new grading to west and houses to east and south |

| 68 | Impact | Before | 93 | San Bernardino Logistics Center | San Bernardino | Warehouse | 1/25/2018 | 8:00 | 8.22 | Feral grassland on disked soil |

| 68 | Impact | After | 93 | San Bernardino Logistics Center | San Bernardino | Warehouse | 2/8/2023 | 7:12 | 8.22 | Warehouse |

| 70 | Control | Before | 95 | The Ranch at Eastvale | Eastvale | Warehouse | 1/9/2020 | 9:22 | 7.08 | Disked grassland bordered by irrigated, planted native plants, shrubs, trees |

| 70 | Control | After | 95 | The Ranch at Eastvale | Eastvale | Warehouse | 2/6/2023 | 8:58 | 7.08 | Warehouses with landscaped shrubs and trees |

| 71 | Control | Before | 156 | Alviso Hotel | Alviso | Hotel | 4/1/2022 | 6:44 | 2.52 | Wetland and ruderal vegetation |

| 71 | Control | After | 156 | Alviso Hotel | Alviso | Hotel | 4/6/2023 | 7:12 | 2.52 | Wetland and ruderal vegetation |

| 72 | Control | Before | 146 | Conejo Summit | Thousand Oaks | Biotech industrial buildings | 3/7/2022 | 15:18 | 20.17 | Annual grassland, sage scrub dominated by California buckwheat, California sagebrush, coyote brush, deerweed |

| 72 | Control | After | 146 | Conejo Summit | Thousand Oaks | Biotech industrial buildings | 4/2/2023 | 15:18 | 20.17 | Annual grassland, sage scrub dominated by California buckwheat, California sagebrush, coyote brush, deerweed |

| 73 | Control | Before | 147 | Gillespie Field | El Cajon | Warehouse | 3/13/2021 | 6:48 | 12.83 | Annual grassland, San Diegan sage scrub |

| 73 | Control | After | 147 | Gillespie Field | El Cajon | Warehouse | 3/29/2023 | 6:56 | 12.83 | Annual grassland, San Diegan sage scrub |

| 75 | Control | Before | 130 | Greentree | Vacaville | Residential | 5/25/2022 | 5:31 | 76.65 | Disked abandoned golf course with dead and living trees and dried wetlands |

| 75 | Control | After | 130 | Greentree | Vacaville | Residential | 5/18/2023 | 5:37 | 76.65 | Freshly disked abandoned golf course with more dead trees, some removed |

| 76 | Control | Before | 60 | Amazing 34 | San Bernardino | Warehouse | 4/25/2022 | 10:18 | 1.55 | Demolished buildings and annual grassland and ornamental trees around pads |

| 76 | Control | After | 60 | Amazing 34 | San Bernardino | Warehouse | 5/22/2023 | 10:08 | 1.55 | Demolished buildings and annual grassland and ornamental trees around pads |

| 77 | Control | Before | 139 | Haun and Holland | Menifee | Warehouse | 6/6/2020 | 6:06 | 15.00 | Annual grassland and ruderal vegetation |

| 77 | Control | After | 139 | Haun and Holland | Menifee | Warehouse | 5/22/2023 | 6:13 | 15.00 | Annual grassland and ruderal vegetation |

| 78 | Impact | Before | 120 | Hillcrest LRDP | UCSD, Hillcroft Campus | Campus redevelopment | 11/9/2019 | 7:00 | 12.95 | Riparian, Eucalyptus |

| 78 | Impact | After | 120 | Hillcrest LRDP | UCSD Hillcroft Campus | Campus redevelopment | 12/11/2021 | 7:11 | 12.95 | New buildings and construction underway on campus |

| 79 | Control | Before | 195 | Diamond Street Warehouse | San Marcos | Warehouse | 6/25/2021 | 5:59 | 9.31 | Coastal sage scrub with grown-over disturbed area in central aspect |

| 79 | Control | After | 195 | Diamond Street Warehouse | San Marcos | Warehouse | 6/14/2023 | 6:35 | 9.31 | Coastal sage scrub with grown-over disturbed area in central aspect |

| 80 | Impact | Before | 80 | Casmalia & Linden | Rialto | Warehouse | 7/31/2021 | 6:12 | 2.77 | Grassland and shrubs |

| 80 | Impact | After | 80 | Casmalia & Linden | Rialto | Warehouse | 7/8/2023 | 6:12 | 2.77 | Warehouses with landscaping |

| 81 | Control | Before | 135 | Fore Apartments | Oxnard | Residential | 6/26/2022 | 6:40 | 1.71 | Mowed annual grassland with a few peripheral trees |

| 81 | Control | After | 135 | Fore Apartments | Oxnard | Residential | 7/15/2023 | 6:54 | 1.71 | Ruderal grassland around graded plots |

| 82 | Impact | 148 | Scannell Properties | Richmond | Warehouses | 7/13/2021 | 17:50 | 11.90 | Ruderal grassland around graded | |

| 82 | Impact | 148 | Scannell Properties | Richmond | Warehouses | 7/16/2023 | 17:45 | 11.90 | Operational warehouse and nearly completed empty warehouse | |

| a The survey in the before phase consisted of two surveys separated by 6 days. Because the species detected were lumped between the two surveys, we could not single out the first survey date for comparison. We therefore treated the survey in the after phase the same way by completing a second survey 7 days after the first survey. Shown in the Appendix are only the dates and start times of the first survey in both phases. The second surveys in both phases were completed 6 and 7 days later, respectively, on 21 January 2008 and on 12 January 2021, and combined survey duration between the before and after phases differed by only 12 minutes. b The survey in the before phase consisted of two surveys separated by 3 days. Because the species detected were lumped between the two surveys, we could not single out the first survey date for comparison. We therefore treated the survey in the after phase similarly by completing a second survey 20 days after the first survey. Shown in the Appendix are only the dates and start times of the first survey in both phases. The second surveys in both phases were completed 3 and 20 days later, respectively, on 21 January 2008 and on 3 July 2021, and the combined survey duration between the before and after phases differed by only 2 minutes. | ||||||||||

References

- Marzluff, J.M.; Bowman, R.; Donnelly, R. A historical perspective on urban bird research: trends, terms, and approaches. In Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, USA, 2001; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, M. The effects of urban patterns on Ecosystem function. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2005, 28, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biological Conservation 2006, 127, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.; Marzluff, J.M. Importance of reserve size and landscape context to urban bird conservation. Conservation Biology 2003, 18, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.R.; Suarez, A.V.; Bolger, D.T. Avian assem blages along a gradient of urbanization in a highly fragmented landscape. Biological conservation 2004, 115, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chace, J.F.; Walsh, J.J. Urban effects on native avifauna: a review. Landsc Urban Plan 2006, 74, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devictor, V.; Julliard, R.; Couvet, D.; Lee, A.; Jiguet, F. Functional homogenization effect of urbanization on bird communities. Conservation Biology 2007, 21, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson; M.F.J.; La Sorte, F.A.; Nilon, C.H.; Katti, M.; Goddard, M.A.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Warren, P.S.; Williams, N.S.; Cilliers, S.; Clarkson, B.; Dobbs, C. A Global Analysis of the Impacts of Urbanization on Bird and Plant Diversity Reveals Key Anthropogenic Drivers. Proc. R. Soc/ B: Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20133330.

- Groffman, P.M.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Bettez, N.D.; Grove, J.M; Hall, S.J.; Heffernan, J.B.; Hobbie, S.E.; Larson, K.L.; Morse, J.L.; Neill, C.; Nelson, K.; O’Neil-Dunne, J.; Ogden, L.; Pataki, D.E.; Polsky, C.; Chowdhury, R.R.; Steele, M.K. Ecological homogenization of urban USA. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez -Álamo, J.D.; Rubio, E.; Benedett, Y.; Morell, F. Global loss of avian evolutionary uniqueness in urban areas. Global Change Biology 2017, 23, 2990–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salwasser, H. Conserving biological diversity: a perspective on scope and approaches. Forest Ecology and Management 1990, 35, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin III, F.; Zavaleta, E.; Eviner, V.; Naylor, R.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Reynolds, H.L.; Hooper, D.U.; Lavorel, S.; SalaI, O.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; Mack, M.C.; Díaz, S. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.S.; Krausman, P.R.; Morrison, M.L. The habitat concept and a plea for standard terminology. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1997, 25, 173–82. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, M.L.; Marcot, B.G.; Mannan, R.W. Wildlife-habitat relationships: concepts and applications, 2nd ed.; University of Wisconsin Press : Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksson, C.; Rodewald, A.D.; Gil, D. Editorial: behavioural and ecological consequences of urban life in birds. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2018, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.S. Habitat fragmentation and corridors. In Wildlife habitat conservation: concepts, challenges, and solutions; Morrison, M.L., Mathewson, H.A., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, Maryland, USA, 2015; pp. 84–101. [Google Scholar]

- Marzluff, J.M. Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, K.S.; Riley, S.P.D.; Fisher, R.N. A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sol, D.; Lapiedra, O.; Gonz´alez-Lagos, C. Behavioural adjustments for a life in the city. Anim. Behav 2013, 85, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.V.; Dokter, A.M.; Blancher, P.J.; Sauer, J.R.; Smith, A.C.; Smith, P.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Panjabi, A.; Helft, L.; Parr, M.; Marra, P.P. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 2019, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germaine, S.S.; Rosenstock, S.S.; Schweinsburg, R.E.; Richardson, W.S. Relationships among breeding birds, habitat, and residential development in greater Tucson, Arizona. Ecol. Appl. 1998, 8, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, D.; Carrascal, L.M. Urban influence on birds at a regional scale: A case study with the avifauna of northern Madrid province. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 77, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Estrella, R. Land use changes affect distributional patterns of desert birds in the Baja California peninsula, Mexico. Diversity and Distributions 2007, 13, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, E.; Urban, D. Forest bird communities across a gradient of urban development. Urban Ecosystems 2010, 13, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Minor, E.S.; Park, C.R.; Lee, D. Effects of habitat structure, human disturbance, and habitat connectivity on urban forest bird communities. Urban Ecosystems 2015, 18, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.B. Creating a homogeneous avifauna. Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, USA, 2001; pp. 459–486. [Google Scholar]

- Cam, E.; Nichols, J.D.; Sauer, J.R.; Hines, J.E.; Flather, C.H. Relative species richness and community completeness: birds and urbanization in the mid-Atlantic states. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, J.R. Landscapes and Management for Ecological Integrity. In Biodiversity and Landscape: A Paradox for Humanity; Kim, K.C., Weaver, R.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, USA, 1994; pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, T.A. Initial effects of housing construction on woodland birds along the wildland urban interface. In Interface Between Ecology and Land Development in California; Keeley, J.E., Ed.; 1993; pp. 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler, M.; Duncan, S.; Paul, J. Post-construction effects of an urban development on migrating, resident, and wintering birds. Southeastern Naturalist 2005, 4, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.M. The “standardized search”: an improved way to conduct bird surveys. Austral Ecology 2003, 28, 515–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.L. Towards reliable bird surveys: accounting for individuals present but not detected. The Auk 2002, 119, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, R.L. Should scientists be required to use a model-based solution to adjust for possible distance-based detectability bias? Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.M.; Colón, M.R.; Bosman, J.L.; Robinson, D.H.; Pruett, H.L.; McFarland, T.M.; Mathewson, H.A.; Szewczak, J.M.; Newnam, J.C.; Morrison, M.L. A before–after control–impact assessment to understand the potential impacts of highway construction noise and activity on an endangered songbird. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallwood, K.S.; Bell, D.A. Effects of wind turbine curtailment on bird and bat fatalities. J. Wildl, Manag. 2020, 84, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørenson, T. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content. Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Skrifter 1948, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shuford, W.D.; Gardali, T.; Eds.; California bird species of special concern: a ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, 2008, Camarillo, California. Shuford, W.D.; Gardali, T. (Eds.).

- Callaghan, C.T.; Major, R.E.; Wilshire, J.H.; Martin, J.M.; Kingsford, R.T.; Cornwell, W.K. Generalists are the most urban-tolerant of birds: a phylogenetically controlled analysis of ecological and life history traits using a novel continuous measure of bird responses to urbanization. Oikos 2019, 128, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.B. Land use and avian species diversity along an urban gradient. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Lagos, C.; Cardador, L.; Sol, D. Invasion success and tolerance to urbanization in birds. Ecography 2021, 44, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, D.T.; Alberts, A.C.; Sauvajot, R.M.; Potenza, P.; McCalvin, C.; Tran, D.; Mazzoni, S.; Soule, M.E. Response of Rodents to Habitat Fragmentation in Coastal Southern California. Ecol. Appl. 1997, 7, 552–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvajot, R.M.; Buechner, M.; Kamradt, D.A.; Shonewald, C.M. Patterns of human disturbance and response by small mammals and birds in chaparral near urban development. Urban Ecosystems 1998, 2, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Effects of urbanization on species richness: a review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosystems 2008, 11, 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.S.; Morrison, M.L. Nest-site selection in a high-density colony of burrowing owls. J. Raptor Res 2018, 52, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.S.; Smallwood, N.L. Breeding density and collision mortality of loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) in the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area. Diversity 2021, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrén, H. Effects of habitat fragmentation on birds and mammals in landscapes with different proportions of suitable habitat: a review. Oikos 1994, 71, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clergeau, P.; J. Jokimäki, J.; Savard, J.P.L. Are urban bird communities influenced by the bird diversity of adjacent landscapes? J. Applied Ecology 2001, 38, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narango, D.L.; Tallamy, D.W.; Marra, P.P. Native plants improve breeding and foraging habitat for an insectivorous bird. Biological Conservation 2017, 213, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.J.; Li, E.; Bahlai, C.A.; Meineke, E.K.; McGlynn, T.P.; Brown, B.V. Local and landscape-scale variables shape insect diversity in an urban biodiversity hot spot. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, S.B.; Warren, P.S. The conservation value of residential yards: linking birds and people. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 1327–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghardt, K.T.; Tallamy, D.W.; Shriver, W.G. Impact of native plants on bird and butterfly biodiversity in suburban landscapes. Conservation Biology 2008, 23, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthon, K.; Thomas, F.; Bekessy, S. The role of ‘nativenes’ in urban greening to support animal biodiversity. Landsc Urban Plan 2021, 205, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, N.L.; Wood, E.M. The ecological role of native-plant landscaping in residential yards to birds during the nonbreeding period. Ecosphere 2022, 14, e4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, M.A.; Dougill, A.J.; Benton, T.G. Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2009, 25, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallamy, D.W. Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation that Starts in Your Yard; Timber Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Metric | CB (n = 52) | CA (n = 52) | IB (n = 26) | IA (n= 26) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | SD | SD | SD | |||||

| Size of project site (Hectares) | 131 | 310 | 16.25 | 30.22 | ||||

| Elevation (m) | 175 | 214 | 138 | 243 | ||||

| Northing (m) | 3994623 | 241749 | 4088256 | 213973 | ||||

| Urban setting | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.51 | ||||

| Connectivity (%) | 35.0 | 30.8 | 35.0 | 30.8 | 17.3 | 19.7 | 15.4 | 17.4 |

| Project site disturbance | 4.12 | 2.70 | 4.13 | 2.70 | 5.20 | 2.69 | 10.58 | 1.65 |

| Rating of suppressive actions | 1.24 | 1.92 | 1.51 | 2.24 | 2.58 | 2.47 | 5.50 | 1.63 |

| Survey duration (minutes) | 128 | 47 | 125 | 46 | 96 | 38 | 96 | 38 |

| Years since first survey | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | ||||

| Start time difference (minutes) | -3.6 | 38.0 | -2.9 | 34.4 | ||||

| Metric | CB | CA | IB | IA | Effect | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | N | SD | N | SD | N | SD | N | ||||||

| Number of species | |||||||||||||

| All vertebrates | 26.4 | 11.1 | 51 | 28.2 | 10.7 | 51 | 19.1 | 5.9 | 26 | 10.7 | 3.7 | 26 | -48 |

| Onsite vertebrates | 22.8 | 12.9 | 30 | 25.5 | 12.6 | 30 | 17.4 | 6.6 | 20 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 20 | -66 |

| All birds | 23.5 | 9.6 | 51 | 25.2 | 9.4 | 51 | 17.6 | 5.9 | 26 | 10.3 | 3.6 | 26 | -45 |

| Onsite birds | 19.9 | 11.3 | 30 | 22.5 | 11.1 | 30 | 16.0 | 6.4 | 20 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 20 | -64 |

| All mammals | 2.5 | 2.3 | 51 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 51 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 26 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 26 | -79 |

| Onsite mammals | 2.5 | 2.4 | 30 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 30 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 20 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 20 | -92 |

| All herps | 0.4 | 0.7 | 51 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 51 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 26 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 26 | -47 |

| Onsite herps | 0.5 | 0.9 | 27 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 27 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20 | -100 |

| All non-birds | 2.9 | 2.6 | 51 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 51 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 26 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 26 | -75 |

| Onsite non-birds | 2.9 | 2.9 | 30 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 30 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 20 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 20 | -96 |

| All special-status species | 5.2 | 2.8 | 51 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 51 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 26 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 25 | -49 |

| Onsite special-status species | 4.3 | 3.1 | 30 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 30 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 20 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 19 | -58 |

| Model-predicted at 1 hour | 20.0 | 6.4 | 42 | 21.3 | 5.2 | 51 | 16.9 | 4.5 | 14 | 11.3 | 4.8 | 25 | -37 |

| Unique species per survey | 9.9 | 5.2 | 51 | 11.6 | 4.9 | 51 | 12.6 | 4.8 | 27 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 27 | -74 |

| Animals counted | |||||||||||||

| All vertebrates | 155.4 | 117.0 | 19 | 187.2 | 157.4 | 19 | 358.7 | 259.0 | 15 | 42.9 | 23.7 | 15 | -90 |

| Onsite vertebrates | 107.7 | 144.3 | 14 | 99.0 | 80.9 | 14 | 335.4 | 284.4 | 14 | 34.9 | 18.2 | 14 | -89 |

| All birds | 135.6 | 102.6 | 19 | 183.3 | 154.3 | 19 | 354.0 | 255.3 | 15 | 42.5 | 23.5 | 15 | -91 |

| Onsite birds | 98.6 | 130.4 | 14 | 96.7 | 80.4 | 14 | 330.5 | 280.3 | 14 | 34.8 | 18.1 | 14 | -89 |

| All special-status species | 30.9 | 67.5 | 19 | 17.3 | 22.2 | 19 | 31.8 | 51.0 | 15 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 14 | -70 |

| Onsite special-status species | 11.8 | 16.0 | 14 | 9.9 | 12.5 | 14 | 35.1 | 54.1 | 13 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 12 | -82 |

| Metric | Normally distributed? |

Hartley's F-max P-value |

Control-Impact main effect |

Before-After main effect |

CI × BA interaction effect |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | 1–β | |||

| Number of species | |||||||||

| All vertebrates | Yes | 0.6161 | 99.34 | 0.0000 | 16.31 | 0.0001 | 28.23 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| Onsite vertebrates | Yes | 0.7228 | 65.44 | 0.0000 | 21.31 | 0.0000 | 30.54 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| All birds | Yes | 0.7747 | 84.00 | 0.0000 | 12.52 | 0.0005 | 23.90 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| Onsite birds | Yes | 0.6205 | 49.67 | 0.0000 | 15.93 | 0.0001 | 26.42 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| All mammals | Yes | 0.0600 | 8.52 | 0.0043 | 0.60 | 0.4408 | 0.03 | 0.8560 | 0.05 |

| Onsite mammals | Yes | 0.1827 | 5.78 | 0.0192 | 1.20 | 0.2783 | 0.60 | 0.4402 | 0.12 |

| All herps | Yes | 1.0000 | 3.07 | 0.0888 | 0.01 | 0.9104 | 0.01 | 0.9104 | 0.05 |

| Onsite herps | |||||||||

| All non-birds | Yes | 0.0622 | 14.50 | 0.0002 | 1.19 | 0.2770 | 0.56 | 0.4576 | 0.11 |

| Onsite non-birds | Yes | 0.0837 | 4.24 | 0.0436 | 0.71 | 0.4029 | 0.47 | 0.4947 | 0.10 |

| All special-status species | Yes | 0.6230 | 46.00 | 0.0000 | 12.18 | 0.0006 | 12.18 | 0.0006 | 0.93 |

| Onsite special-status species | Yes | 0.2806 | 12.05 | 0.0008 | 5.26 | 0.0242 | 4.71 | 0.0327 | 0.57 |

| Model-predicted at 1 hour | Yes | 0.2336 | 37.04 | 0.0000 | 4.06 | 0.0459 | 10.32 | 0.0017 | 0.89 |

| Unique species per survey | Yes | 0.7910 | 24.05 | 0.0000 | 36.01 | 0.0000 | 71.50 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| Animals counted | |||||||||

| All vertebrates | Yes | 0.2890 | 2.44 | 0.1235 | 17.80 | 0.0001 | 32.11 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| Onsite vertebrates | snaky | 0.0035 | 0.02 | 0.8842 | 7.40 | 0.0088 | 11.77 | 0.0012 | 0.92 |

| All birds | Yes | 0.2916 | 1.62 | 0.2076 | 15.63 | 0.0002 | 34.79 | 0.0000 | 1.00 |

| Onsite birds | Yes | 0.0040 | 0.00 | 0.9964 | 6.68 | 0.0126 | 11.86 | 0.0011 | 0.92 |

| All special-status species | Yes | 0.8945 | 1.96 | 0.1672 | 10.11 | 0.0023 | 4.76 | 0.0331 | 0.57 |

| Onsite special-status species | Yes | 0.8629 | 0.84 | 0.3647 | 9.87 | 0.0030 | 6.15 | 0.0171 | 0.68 |

| Group | Control (n = 52) | Impact (n = 26) | Effect (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | ||

| Birds | 23.1 | 25.73 | 17.73 | 10.19 | -48 |

| Mammals | 2.52 | 2.42 | 1.38 | 0.19 | -86 |

| Reptiles | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0 |

| Amphibians | 0.06 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0 | -100 |

| Special status species | 5.11 | 4.88 | 3.69 | 1.81 | -49 |

| Non-native birds | 1.98 | 2.37 | 2.69 | 1.81 | -44 |

| Synanthropic birds | 7.19 | 7.67 | 7.42 | 5.73 | -28 |

| Raptors | 2.77 | 2.61 | 2.58 | 1.15 | -53 |

| Grassland birds | 1.9 | 1.81 | 1.5 | 0.36 | -75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).