1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain the number one cause of death globally, killing about 18 million people every year [

1,

2]. Atherosclerosis is the dominant process in CVD and is characterized by a complex condition involving multiple factors related to the disruption of cholesterol metabolism, inflammation and redox homeostasis [

2,

3,

4]. These events develop slowly and progressively and are linked to disturbances of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) physiology and LDL interaction with arterial wall cells, mainly with macrophages [

5].

Macrophages act as immune sentinels responding quickly to micro-environmental signals and changing their phenotype to develop specific functions such as inducing or resolving local inflammation [

6]. During early steps of atherogenesis, macrophages derived from circulating monocytes become lipid-laden foam cells by taking up chemically modified LDL trapped in the subendothelial space. These sequestered lipoproteins can induce endothelial dysfunction and promote recruitment of additional blood-borne monocytes to the lesion site. Upon differentiating into macrophages, these cells internalize modified LDL and accumulate intracellular cholesterol, becoming pro-inflammatory and eventually undergoing cell death, forming a necrotic core within the lesion [

2,

3,

6,

7,

8]. The monocyte-derived macrophages present in the atherosclerotic lesion are produced in the bone marrow [

5] and macrophage accumulation in the established mouse atheroma may arise from local replication [

9].

To investigate the impact of macrophages in atherosclerosis, bone marrow transplantation in mice offers a powerful and effective strategy. This approach allows the generation of chimeric animals with a hematopoietic compartment carrying the donor’s genetic background, which enables the identification of the role of the genetic profile of these cells in the development of atherosclerosis [

10]. Consistent evidence has shown that the reconstitution of Apoe-/- mice with wild-type bone marrow cells resulted in protection from high lipid levels and atherosclerosis and, conversely, wild-type mice reconstitution with Apoe-/- bone marrow cells exacerbated atherosclerosis [

11,

12]. In addition, Ldlr-/- mice exhibited increased atherosclerosis after transplantation with ABCA1 deficient or ABCA1+SR-B1 deficient bone marrow, proteins that are involved in the efflux of membrane cholesterol from macrophages [

13,

14].

CETP expression and plasma activity may modulate atherosclerosis and its role is likely highly dependent on the metabolic context and genetic background. Most humans and rabbits’ studies suggest that CETP expression or activity promotes atherosclerosis progression, mainly through its effect of increasing non-HDL lipoproteins and decreasing HDL-cholesterol plasma levels. On the other hand, experimental evidence, mainly in genetically modified mice, supports the concept that CETP may protect against atherosclerosis when LDL receptor function is preserved [

15]. An important novel function of CETP that may be relevant for atherogenesis is its putative modulatory role on inflammation. Whole body CETP expression protects mice from mortality in sepsis models [

16,

17]. Additionally, the survival rate of patients with sepsis correlates with the plasma CETP concentration [

18]. However, contrary results have recently been reported in mice and humans [

19,

20]. These discrepancies are not surprising since in vivo it is quite difficult to discriminate between the effects of the reciprocal changes in CETP and HDL concentrations on the susceptibility or protection against acute inflammation.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CETP-expressing mice hypercholesterolemic due to Apoe or Ldlr gene deficiency develop more atherosclerosis than CETP non-expressing mice [

21]. Moreover, female Ldlr-/- mice transplanted with CETP-expressing bone marrow from transgenic mice exhibited increased atherosclerosis [

22]. However, it is noteworthy that these experimental groups lacked the nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (Nnt) gene (C57BL/6J background), that encodes a mitochondrial enzyme which plays a critical role in the maintenance of cell redox [

23,

24], inflammatory [

25] and cholesterol homeostasis [

24], and predisposes to metabolic disturbances [

26]. Indeed, our recent findings have shown that transplantation of Ldlr-/- mice (Nnt deficient) with Nnt preserved bone marrow (C57BL/6JUnib) significantly reduced atherosclerosis development [

24].

Therefore, in light of these findings, we propose that CETP-expressing macrophages with preserved Nnt expression (C57BL/6JUnib) offer a promising and beneficial strategy for modulating atherosclerosis development in Ldlr-/- mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with the National Council for Animal Experimentation Control (CONCEA) and were approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the State University of Campinas (CEUA/UNICAMP #3814-1(A)/2017, #5270-1/2019). Mice lacking the LDL receptor gene, Ldlr-/- (B6.129S7-Ldlrtm1Her/J) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory in 2009 and maintained in the Multidisciplinary Center for Biological Investigation on Laboratory Animal Science (CEMIB/UNICAMP). Mice overexpressing simian CETP (sCETP) mice (Tg [CETP] UCTP20Pnu/J) was purchased from the Jackson Laboratory in 2013 and crossbred with the C57BL/6JUnib for more than 7 generations. The C57BL/6JUnib colony was originally supplied by the Zentralinstitut für Versuchstierzucht (ZfV) (Hannover, Germany) in 1987, which had previously been obtained from the Jackson Laboratory before the spontaneous deletion of the Nnt gene in their colony [

27]. Simian CETP expressing mice were screened by PCR using tail tip genomic DNA according to the Jackson Laboratory protocol. All animal work was done in the Lipid Metabolism Laboratory, Dept of Structural and Functional Biology, Institute of Biology, State University of Campinas. Mice were kept under standard laboratory conditions (at 22±1°C and 12h light/dark cycle) in a local (conventional) animal facility, in individually ventilated cages (3-4 mice/cage) with free access to filtered tap water and regular rodent AIN93-M diet (standard laboratory rodent chow diet, Nuvital CR1, Colombo, PR, Brazil). Two independent transplantation studies were performed using the following recipient mice: 1) male Ldlr-/- mice of 7 weeks of age (n=12/group) and 2) female Ldlr-/- mice of 15-18 months of age (n=7-11/group). Mice were allocated to receive bone marrow transplants from either sCETP transgenic or non-transgenic littermates as donors, while ensuring the appropriate matching of male donors to male recipients and female donors to female recipients. After bone marrow transplantation, mice had free access to sterile water and sterile high fat (22 g%) and high cholesterol diet (0.15 g%) (

Supplementary Table S1) for 8 weeks. For terminal experiments, mice were anesthetized with xylazine/ketamine (10 and 50 mg/Kg, respectively), ip, followed by exsanguination through the retro-orbital plexus for plasma analyses. Hearts were perfused and excised for atherosclerosis analyses.

2.2. Irradiation and Bone Marrow Transplantation

Seven-week-old male and 15-18-month-old female Ldlr-/- mice were exposed to a single 8.0-Gy total-body irradiation using a 6 MV linear accelerator (Clinac2100C, Varian Medical Systems). Immediately, after irradiation, the animals were injected via the tail vein with 5.0 x 10

6 bone marrow cells freshly collected from 8-week-old male or female donor mice, including both sCETP transgenic and non-transgenic mice, were used for the bone marrow transplants. The bone marrow cells were aseptically harvested by flushing donor femurs and tibias with Dulbecco’s PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum. Samples were filtered through a 40 µm nylon mesh and centrifuged at room temperature for 10 minutes at 300g. Cells were suspended in 200 μL of Dulbecco's PBS supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, at a concentration of 5.0 × 10

6 viable nucleated cells per injection into the mouse tail vein. Subsequently, mice underwent a one-week recovery period housed in autoclaved ventilated cages. Mice were treated with antibiotics (0.2 mg trimethoprim and 1.0 mg/ml sulfamethoxazole) in the drinking water for 4 days before and 7 days after the BM transplantation. The transplanted mice were subsequently placed on a high-fat and high-cholesterol diet for the following 8 weeks (supplementary

Table S1).

2.3. Plasma Lipids

Non-fasting plasma lipids were determined using enzymatic-colorimetric assays (Randox Laboratories Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Aortic Root Lesion Area

Mice hearts were perfused in situ with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% PBS-buffered formaldehyde. Hearts were then excised and embedded in Tissue-Tek® OCT compound (Sakura Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) and frozen at -80°C. The tip of the heart (ventricle) was removed with a surgical knife and serial sections of 60 µm were cut and discarded until the visualization of the aortic sinus leaflets. Then, sections were reduced to 10 µm thickness and cut along a 480 µm aorta length. Sections were stained with Oil Red O. The red areas of the lesions were calculated as the sum of lipid-stained lesions (1 section every 120 µm along the aorta length). The lipid-stained lesions were quantified using Image J (1.45h) software.

2.5. Lesion Area Immunofluorescence Staining

The same procedure for cryosections was employed in additional hearts for immunofluorescence staining. Cryosections were blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and then incubated for 3h at 22°C or overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: CD68 antibody (1:200; Bio-Rad), purified anti-mouse Ly-6G antibody (1:50, Biolegend), anti-TNF-α antibody (1:50, Abcam), biotinylated nitrotyrosine (3-NT) (1:100; Cayman Chemical), anti-DNA/RNA damage antibody, epitope 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine (1:50, Abcam), anti-iNOS (1:500, Thermo Fisher). Sections were washed and incubated with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody Alexa Fluor-conjugated (Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 10 min. Sections were mounted with Vectashield medium and microscopic images of aortic lesions (objective lenses 10x) were digitalized, and morphometric measurements were calculated as described for Oil red O. Image J software (NIH – Image J, USA) was used for all the quantifications.

2.6. Real time PCR

Thoracic aortas RNA were extracted with RNeasy kit (#7400, Qiagen), then 1 µg of purified RNA was used to synthesize the cDNA (High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative quantification was performed using the Step-one real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The primers were designed and tested against the Mus musculus genome (GenBank). The relative quantities of the target transcripts were calculated from duplicate samples (ΔΔCT) and normalized against the endogenous control 36B4 (acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0). The primer sequences are shown in the

Supplementary Table S2.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± the standard error (SE) and individual experimental data. Number of mice (n) is stated in the figure legends. Statistical differences were evaluated by Student’s T-Test. Animal sample size (n) for each experiment was chosen based on literature documentation of the similar studies. Significance was accepted at the level of p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Biometric and plasma lipids data

Biometric data and plasma lipids after bone marrow (BM) transplantation are shown in

Table 1. Young male Ldlr-/- recipients of CETP+ BM show increased plasma total cholesterol levels and decreased adipose tissue. These changes were not observed in aged female Ldlr-/- recipient of CETP+ BM.

3.2. Atherosclerosis features

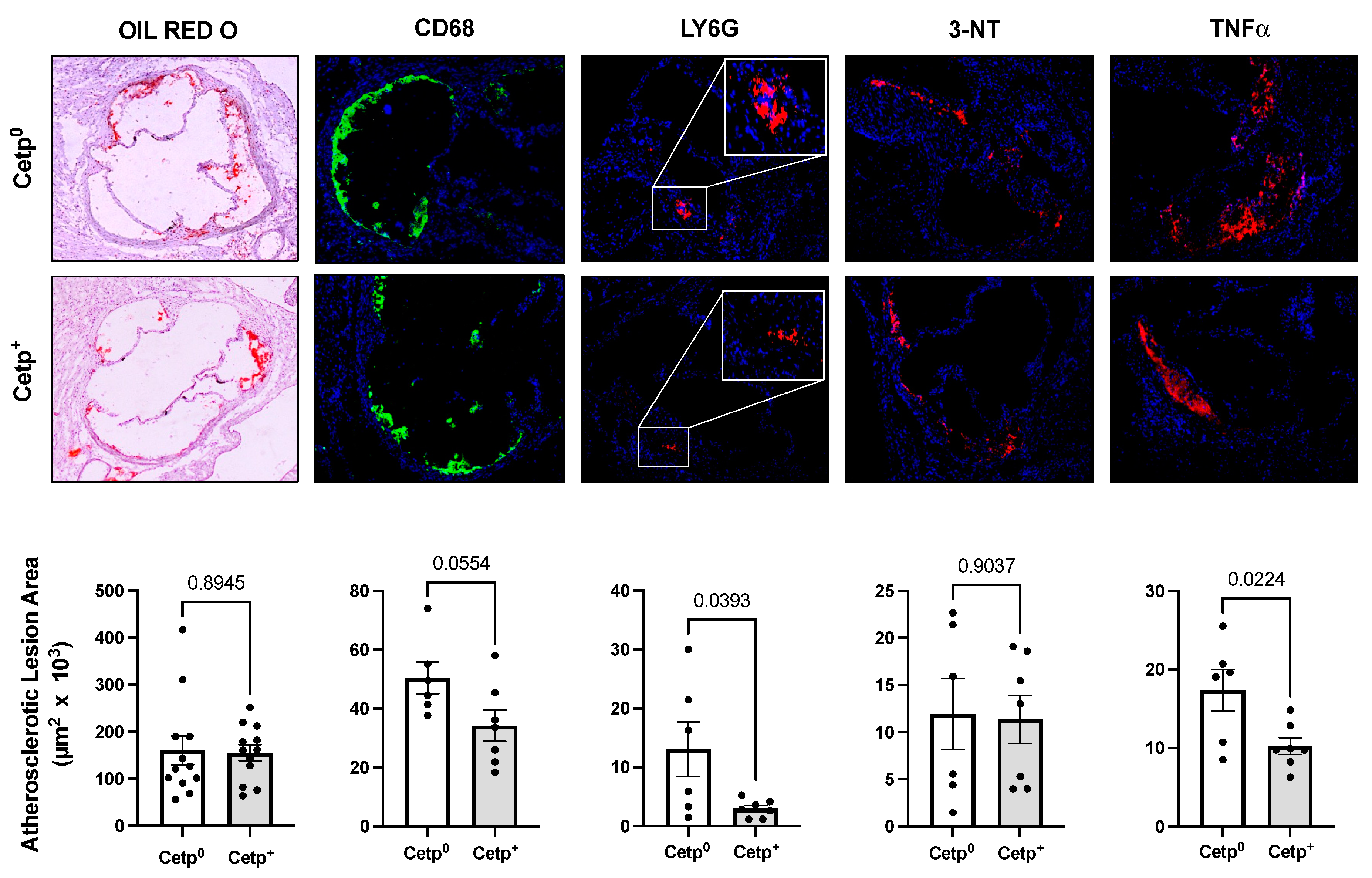

To quantify and characterize the atherosclerotic lesions in transplanted mice, their aorta roots were stained with Oil Red O (lipid content), and immunostained for CD68 (marker of macrophages and monocytes), Ly6G (marker of neutrophils), TNF-α (classic inflammatory marker), 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT, marker of nitro-oxidative stress), 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-Oxo-dG, marker of DNA and RNA oxidative damage) and iNOS (marker of M1 pro-inflammatory type of mouse macrophage) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). In young male Ldlr-/- recipient mice, CETP expressing BM (CETP+) did not change lipid-stained lesion areas compared to CETP non-expressing BM (CETP

0) recipient mice (

Figure 1). However, neutrophils (LY6G) and TNF-α content in recipients of CETP+ BM were significantly reduced, and macrophage (CD68) content also tended to be reduced in CETP+ BM recipients (p=0.055). Protein (3-NT,

Figure 1) and nucleic acid (8-Oxo-dG, not shown) oxidation did not differ between young male Ldlr-/- recipient mice groups.

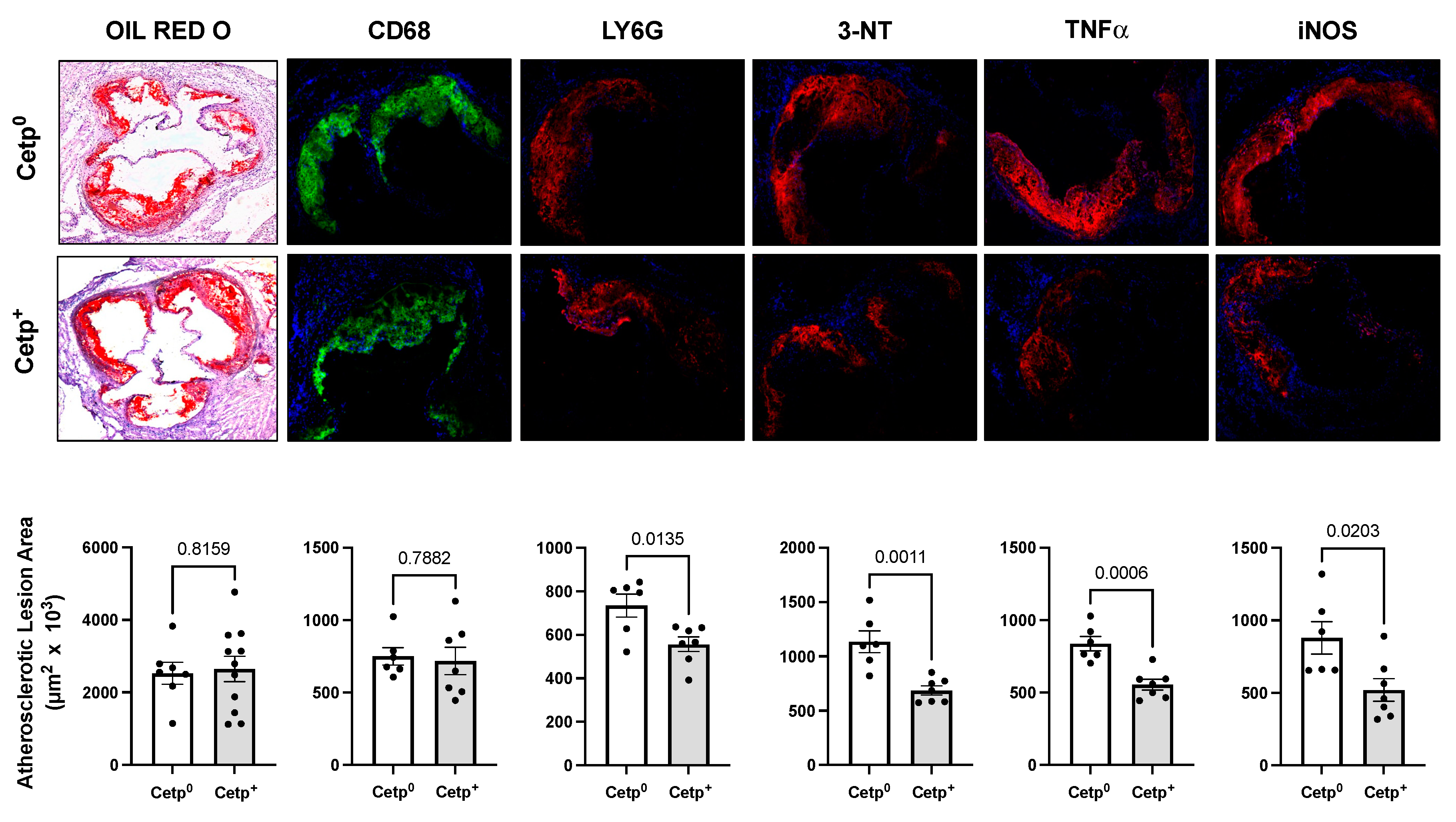

Since the observed lesion sizes in young male mice are small (~2 x 10

5 μm

2), to confirm and expand these findings, we studied another independent group of recipient mice with more advanced atherosclerosis, namely, aged female Ldlr-/- (15-18 months of age,

Figure 2). Lipid (oil red) and macrophage (CD68) content did not differ between recipient groups. However, inflammatory markers (LY6G, TNF-α, iNOS) and nitroxidation of proteins (3-NT) were markedly decreased (

Figure 2) in CETP+ BM recipient Ldlr-/-mice.

3.3. Aortic Gene expression

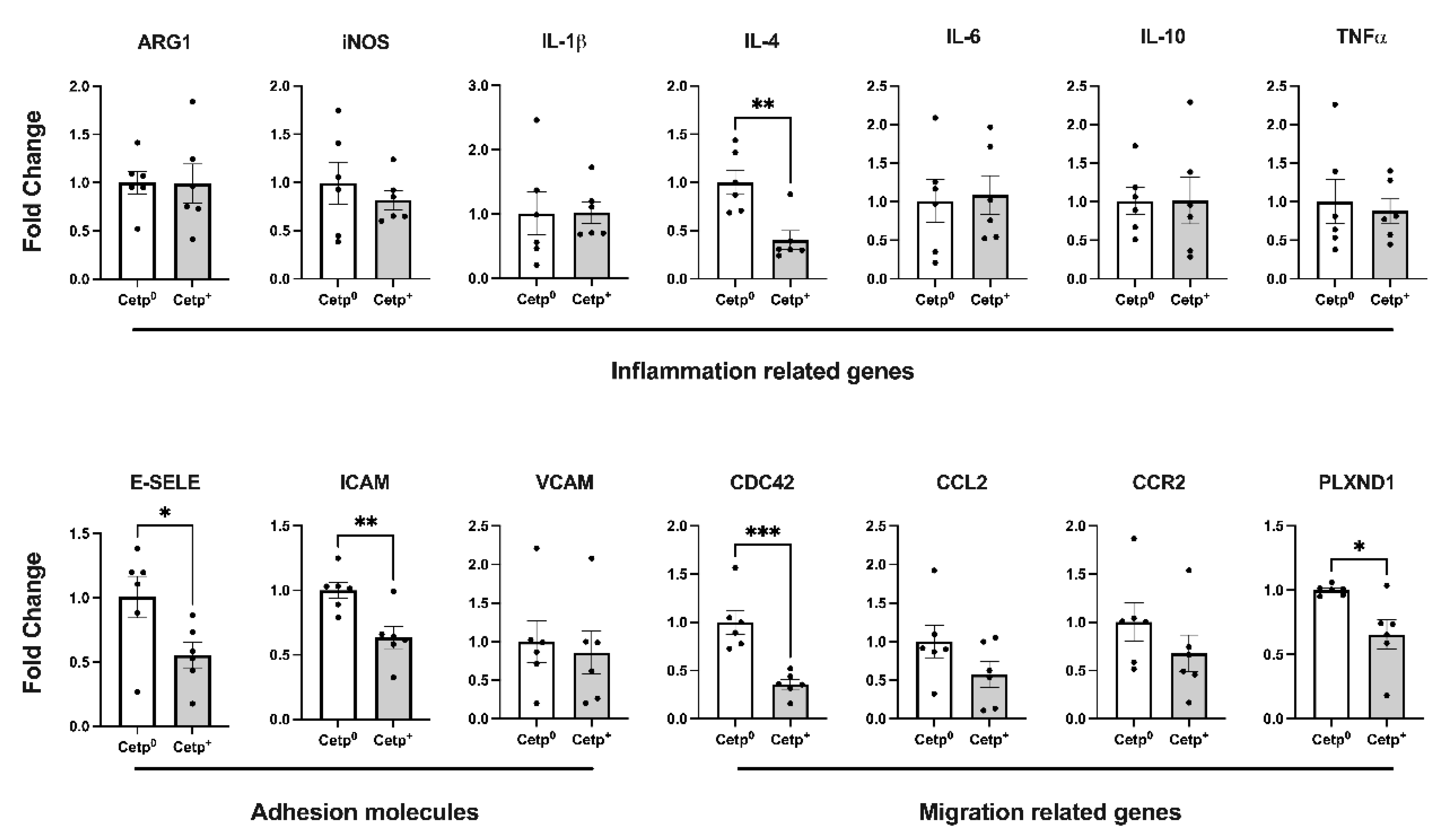

We also evaluated, in the thoracic aorta segment, the expression of genes related to inflammation, adhesion and migration of cells (

Figure 3). Except for IL-4, all classical inflammation related genes (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, iNOS, ARG-1) were not differentially expressed in this segment of the aortas of recipients of CETP+ and CETP

0 BM cells. However, the expression of the adhesion molecules E-selectin and ICAM-1, as well as the expression of migration related genes CDC42 (cell division cycle 42) and PLXND1 (Plexin D1) decreased significantly in the aortas of recipients of CETP+ BM cells (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

CETP has a well-characterized action on determining fluxes of cholesterol among plasma lipoproteins, resulting in reduction of HDL-cholesterol that may be accompanied (or not) by increased non-HDL-cholesterol. Thus, CETP inhibition has been pursued as an anti-atherogenic target. However, its impact on atherosclerosis development is controversial basically because it is largely dependent on diverse genetic and metabolic settings, particularly regarding the functionality of the LDL receptor pathway. Over the last decades, experimental atherosclerosis has been studied on the C57BL/6J background mouse models (Ldlr-/- and Apoe-/-), strains that also carry a spontaneous deletion of the mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme Nnt gene. In this background, CETP is indeed atherogenic [

21,

22,

28]. The Nnt enzyme, first characterized by Rydstrom and colleagues [

30], has a pivotal role on determining cell redox state and susceptibility to metabolic diseases [

23,

24,

26,

27,

29]. Because of its antioxidant action, Nnt expression in macrophages has proven anti-inflammatory [

24,

25] and anti-atherogenic [

24]. Therefore, this study re-evaluated the role of CETP expression in macrophages with preserved expression of Nnt on the development of experimental atherosclerosis.

The main finding reported here is that bone marrow derived cells expressing CETP reduce the content of neutrophils and TNF-α in the aortic lesions of Ldlr-/- mice. Previous studies have shown that neutrophil depletion reduces the burden of atherosclerotic lesion in Ldlr-/- mice while hypercholesterolemia alone induces neutrophilia and accelerates atherogenesis [

30]. In addition, the use of antibodies against Ly6G, a neutrophil specific antigen, indicates that these cells are more abundant in regions of intense inflammatory activity both in Ldlr-/- and Apoe-/- mice models [

30,

31]. It is important to recall that the increase in circulating neutrophils and their accumulation occurs concomitantly with the beginning of high fat diet, contributing to increase lesion sizes [

30]. Human data show that the content of neutrophils is associated with atherosclerotic plaque progression and instability [

32]. Mechanistically, neutrophils exert pro-atherogenic effects via production of reactive oxygen species and release of granular proteins such as α-defensins, azurocidin, and LL-37, proteins previously localized in atherosclerotic plaques [

33]. Neutrophils eventually undergo apoptosis and promote local inflammation. Generally, apoptosis of neutrophils leads to DNA release and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which associate with the progression of atherosclerosis [

34,

35,

36,

37]. In this context, CETP’s anti-inflammatory properties likely attenuated the downstream effects of neutrophil accumulation. The effects of CETP-expressing BM on reducing aortic neutrophils may result from the reduction of TNF-α (and likely other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines) in the lesion microenvironment. TNF-α promotes recruitment, activation and prolongs the lifespan of neutrophils at sites of inflammation such as atherosclerotic injury [

38]. Although we found no significant alterations in the pro-inflammatory related genes in the thoracic aorta of transplanted mice, we observed significant reductions in the expression of E-selectin and ICAM adhesion molecules in the aorta of CETP expressing BM reconstituted mice. Selectins are important for leukocyte adhesion, especially neutrophils, as previously reported in studies with mice deficient in E-selectin and P-selectin [

39,

40,

41].

The data presented here are in line with a previous study in another mouse model expressing apoE3Leiden/CETP treated with torcetrapib [

42]. The authors showed that CETP inhibition by torcetrapib enhanced monocyte recruitment and expression of MCP-1 and yielded lesions with accentuated inflammatory properties as evidenced by increased macrophages and reduced collagen content [

42]. This observation reinforces the anti-inflammatory role of CETP.

Our recent study showed that macrophages from CETP transgenic mice exhibit attenuated pro-inflammatory gene expression (TNF-α, IL-6 and iNOS), diminished reactive oxygen species production, reduced cholesterol accumulation, and phagocytosis [

43]. These localized functions of CETP likely relate to the less inflammatory type of atherosclerotic lesion described here, in agreement with other studies that have reported lower plasma concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 in transgenic mice expressing CETP compared to wild types following LPS stimulation or sepsis [

16,

17]. Given that inflammation plays a key role in initiation and progression of atherosclerosis, we may conclude that CETP, in a context of preserved Nnt expression, contributes to the development of a less detrimental and more stable type of atherosclerotic lesion.

Altogether, these data add on the current knowledge as follows: 1) the impact of CETP expression in BM derived cells on atherogenesis clearly depends on the genetic background, especially regarding the redox and inflammatory context, and 2) CETP expression in BM derived cells, with preserved expression of Ldlr and Nnt genes, contributes to reduce inflammatory features of atherosclerotic lesions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Table S1: High fat and high cholesterol diet composition; Table S2: Primer sequences used for RT-PCR.

Author Contributions

TR, GGD, RRS, DSR, LMB, INF: formal analysis; investigation; visualization. TR, HCFO: Conceptualization; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing. HCFO: supervision; project administration; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo to HCFO (FAPESP #2013/07607-8 #2017/17728-8). TR was supported by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) fellowship and GDD by FAPESP fellowship (#2017/02903-9).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the National Council for Animal Experimentation Control (CONCEA) in accordance with the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of the State University of Campinas (CEUA/UNICAMP #3814-1(A)/2017, #5270-1/2019).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Leonardo Moi de Carvalho for technical assistance and Professor Peter Libby for critical reading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Libby, P.; Hansson, G.K. From Focal Lipid Storage to Systemic Inflammation: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.J.; Sheedy, F.J.; Fisher, E.A. Macrophages in Atherosclerosis: A Dynamic Balance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.C.F.; Vercesi, A.E. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Redox Dysfunctions in Hypercholesterolemia and Atherosclerosis. Mol. Aspects Med. 2020, 71, 100840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.J.; Dragoljevic, D.; Tall, A.R. Cholesterol Efflux Pathways Regulate Myelopoiesis: A Potential Link to Altered Macrophage Function in Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelwyn, G.J.; Corr, E.M.; Erbay, E.; Moore, K.J. Regulation of Macrophage Immunometabolism in Atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The Changing Landscape of Atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammation in Atherosclerosis-No Longer a Theory. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, C.S.; Hilgendorf, I.; Weber, G.F.; Theurl, I.; Iwamoto, Y.; Figueiredo, J.-L.; Gorbatov, R.; Sukhova, G.K.; Gerhardt, L.M.S.; Smyth, D.; et al. Local Proliferation Dominates Lesional Macrophage Accumulation in Atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramkumar, V.; Hidalgo, A. Bone Marrow Transplantation in Mice to Study the Role of Hematopoietic Cells in Atherosclerosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1339, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, W.A.; Spangenberg, J.; Curtiss, L.K. Treatment of Severe Hypercholesterolemia in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice by Bone Marrow Transplantation. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 96, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, M.F.; Atkinson, J.B.; Fazio, S. Prevention of Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice by Bone Marrow Transplantation. Science 1995, 267, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pennings, M.; Hildebrand, R.B.; Ye, D.; Calpe-Berdiel, L.; Out, R.; Kjerrulf, M.; Hurt-Camejo, E.; Groen, A.K.; Hoekstra, M.; et al. Enhanced Foam Cell Formation, Atherosclerotic Lesion Development, and Inflammation by Combined Deletion of ABCA1 and SR-BI in Bone Marrow-Derived Cells in LDL Receptor Knockout Mice on Western-Type Diet. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, e20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.; Zhao, Y.; Hildebrand, R.B.; Singaraja, R.R.; Hayden, M.R.; Van Berkel, T.J.C.; Van Eck, M. The Dynamics of Macrophage Infiltration into the Arterial Wall during Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Knockout Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.C.F.; Raposo, H.F. Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein and Lipid Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1276, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazita, P.M.; Barbeiro, D.F.; Moretti, A.I.S.; Quintão, E.C.R.; Soriano, F.G. Human Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Expression Enhances the Mouse Survival Rate in an Experimental Systemic Inflammation Model: A Novel Role for CETP. Shock 2008, 30, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venancio, T.M.; Machado, R.M.; Castoldi, A.; Amano, M.T.; Nunes, V.S.; Quintao, E.C.R.; Camara, N.O.S.; Soriano, F.G.; Cazita, P.M. CETP Lowers TLR4 Expression Which Attenuates the Inflammatory Response Induced by LPS and Polymicrobial Sepsis. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1784014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grion, C.M.C.; Cardoso, L.T.Q.; Perazolo, T.F.; Garcia, A.S.; Barbosa, D.S.; Morimoto, H.K.; Matsuo, T.; Carrilho, A.J.F. Lipoproteins and CETP Levels as Risk Factors for Severe Sepsis in Hospitalized Patients. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 40, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinder, M.; Genga, K.R.; Kong, H.J.; Blauw, L.L.; Lo, C.; Li, X.; Cirstea, M.; Wang, Y.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Russell, J.A.; et al. Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Influences High-Density Lipoprotein Levels and Survival in Sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinder, M.; Wang, Y.; Madsen, C.M.; Ponomarev, T.; Bohunek, L.; Daisely, B.A.; Julia Kong, H.; Blauw, L.L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; et al. Inhibition of Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Preserves High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Improves Survival in Sepsis. Circulation 2021, 143, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plump, A.S.; Masucci-Magoulas, L.; Bruce, C.; Bisgaier, C.L.; Breslow, J.L.; Tall, A.R. Increased Atherosclerosis in ApoE and LDL Receptor Gene Knock-out Mice as a Result of Human Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Transgene Expression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, M.; Ye, D.; Hildebrand, R.B.; Kar Kruijt, J.; de Haan, W.; Hoekstra, M.; Rensen, P.C.N.; Ehnholm, C.; Jauhiainen, M.; Van Berkel, T.J.C. Important Role for Bone Marrow-Derived Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein in Lipoprotein Cholesterol Redistribution and Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in LDL Receptor Knockout Mice. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronchi, J.A.; Figueira, T.R.; Ravagnani, F.G.; Oliveira, H.C.F.; Vercesi, A.E.; Castilho, R.F. A Spontaneous Mutation in the Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase Gene of C57BL/6J Mice Results in Mitochondrial Redox Abnormalities. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salerno, A.G.; Rentz, T.; Dorighello, G.G.; Marques, A.C.; Lorza-Gil, E.; Wanschel, A.C.B.A.; de Moraes, A.; Vercesi, A.E.; Oliveira, H.C.F. Lack of Mitochondrial NADP(H)-Transhydrogenase Expression in Macrophages Exacerbates Atherosclerosis in Hypercholesterolemic Mice. Biochem. J 2019, 476, 3769–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripoll, V.M.; Meadows, N.A.; Bangert, M.; Lee, A.W.; Kadioglu, A.; Cox, R.D. Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase (NNT) Acts as a Novel Modulator of Macrophage Inflammatory Responses. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 3550–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, C.D.C.; Figueira, T.R.; Francisco, A.; Dal’Bó, G.A.; Ronchi, J.A.; Rovani, J.C.; Escanhoela, C.A.F.; Oliveira, H.C.F.; Castilho, R.F.; Vercesi, A.E. Redox Imbalance Due to the Loss of Mitochondrial NAD(P)-Transhydrogenase Markedly Aggravates High Fat Diet-Induced Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 113, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, A.A.; Lippiat, J.D.; Proks, P.; Shimomura, K.; Bentley, L.; Hugill, A.; Mijat, V.; Goldsworthy, M.; Moir, L.; Haynes, A.; et al. A Genetic and Physiological Study of Impaired Glucose Homeostasis Control in C57BL/6J Mice. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotti, K.R.; Castle, C.K.; Boyle, T.P.; Lin, A.H.; Murray, R.W.; Melchior, G.W. Severe Atherosclerosis in Transgenic Mice Expressing Simian Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein. Nature 1993, 364, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydström, J. Mitochondrial NADPH, Transhydrogenase and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1757, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, M.; Megens, R.T.A.; van Zandvoort, M.; Weber, C.; Soehnlein, O. Hyperlipidemia-Triggered Neutrophilia Promotes Early Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2010, 122, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotzius, P.; Thams, S.; Soehnlein, O.; Kenne, E.; Tseng, C.-N.; Björkström, N.K.; Malmberg, K.-J.; Lindbom, L.; Eriksson, E.E. Distinct Infiltration of Neutrophils in Lesion Shoulders in ApoE-/- Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.G.; van den Borne, P.; Catanzariti, L.M.; Moll, F.L.; de Vries, J.-P.P.M.; Pasterkamp, G.; Vink, A.; de Kleijn, D.P.V. High Neutrophil Numbers in Human Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaques Are Associated with Characteristics of Rupture-Prone Lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1842–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soehnlein, O.; Weber, C. Myeloid Cells in Atherosclerosis: Initiators and Decision Shapers. Semin. Immunopathol. 2009, 31, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megens, R.T.A.; Vijayan, S.; Lievens, D.; Döring, Y.; van Zandvoort, M.A.M.J.; Grommes, J.; Weber, C.; Soehnlein, O. Presence of Luminal Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Atherosclerosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 107, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soehnlein, O. Multiple Roles for Neutrophils in Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, Y.; Soehnlein, O.; Weber, C. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Atherosclerosis and Atherothrombosis. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, N.; Tall, A.R.; Tabas, I. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Promotes Atherosclerosis and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Aged Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, e99–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Cassatella, M.A.; Costantini, C.; Jaillon, S. Neutrophils in the Activation and Regulation of Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.M.; Chapman, S.M.; Brown, A.A.; Frenette, P.S.; Hynes, R.O.; Wagner, D.D. The Combined Role of P- and E-Selectins in Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 102, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.G.; Velji, R.; Guevara, N.V.; Hicks, M.J.; Chan, L.; Beaudet, A.L. P-Selectin or Intercellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM)-1 Deficiency Substantially Protects against Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.E.; Xie, X.; Werr, J.; Thoren, P.; Lindbom, L. Direct Viewing of Atherosclerosis in Vivo: Plaque Invasion by Leukocytes Is Initiated by the Endothelial Selectins. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, W.; de Vries-van der Weij, J.; van der Hoorn, J.W.A.; Gautier, T.; van der Hoogt, C.C.; Westerterp, M.; Romijn, J.A.; Jukema, J.W.; Havekes, L.M.; Princen, H.M.G.; et al. Torcetrapib Does Not Reduce Atherosclerosis beyond Atorvastatin and Induces More Proinflammatory Lesions than Atorvastatin. Circulation 2008, 117, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorighello, G.G.; Assis, L.H.P.; Rentz, T.; Morari, J.; Santana, M.F.M.; Passarelli, M.; Ridgway, N.D.; Vercesi, A.E.; Oliveira, H.C.F. Novel Role of CETP in Macrophages: Reduction of Mitochondrial Oxidants Production and Modulation of Cell Immune-Metabolic Profile. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).