1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is an age-related disease, which is characterized by medium-sized and large arteries filled with lipids [

1,

2]. AS is also known to correlate with chronic inflammation. Cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of mortality worldwide, is caused mainly by AS [

3]. It is well known that macrophages, T cells, and other cells of immune response, together with cholesterol, infiltrate from the blood. As indicated in our previous study, cellular senescence, and oxidative stress throughout the course of AS [

4,

5], thus we focus on the mitochondria and telomere link.

Telomere is the cap structure at the end of chromosome and plays an important role in the regulation of cellular senescence [

6]. PinX1 is a potent and highly conserved endogenous telomerase inhibitor [

7] encoded by the pinX1 gene which is located at human chromosome 8p23 [

8]. Significantly, pinX1 inhibition activated telomerase and elongated telomeres, eventually leading to chromosome instability [

9]. Previous studies focus on the function of pinX1 in cancer. It is reported that pinX1 is a sought-after major tumor suppressor, pinX1 allele loss causes majority of mice to develop a variety of epithelial cancers [

10,

11]. Moreover, pinX1 can inhibit the invasion and metastasis of human cancer by suppressing MMP-9 expression [

12]. By promoting cellular senescence via p16/cyclin D1 pathway, pinX1 suppresses bladder urothelial carcinoma cell proliferation [

13]. In recent years, researchers have provided some clues that pinX1 still plays an important role in processes such as inflammatory-related lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury [

14] and lipid metabolism such as obesity-induced cardiac injury [

15], nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [

16]. PinX1 gene single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are correlated with serum lipid levels [

17]. Genome-wide association studies in 71,128 individuals for carotid artery intima-media thickness, and 18.434 individuals for carotid plaque traits also indicate pinX1 is a susceptibility site for carotid artery plaques [

18], however, the role of pinX1 in AS also needs to be clarified.

P66shc, a redox enzyme, is a widely expressed protein that governs a variety of cardiovascular pathologies. p66shc mainly functions in mitochondria and regulate oxidative stress by generating and exacerbating reactive oxidative stress (ROS) signals [

19,

20]. P66shc is widely studied in cardiovascular diseases and is considered as the engine of vascular aging [

19,

21]. It contributes to mitochondrial ROS formation and translocate from the cytosol to mitochondria upon cellular stress [

22]. Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia conditions during AS contributes to inducing macrophage p66shc and ROS production [

23]. In apolipoprotein E-deficient ( Apoe-/-) mice, the methylation of the p66shc gene promoter and the expression of DNA transfer enzyme 1 are also related to the increased expression level of p66shc [

24]. Although in AS, the cross-talk between mitochondria and telomere has been reported, whether pinX1 regulates p66shc expression remains unclear.

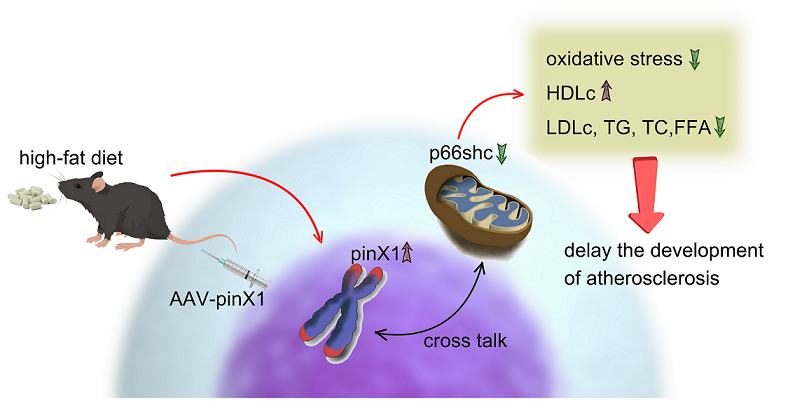

Thus, in this study, we established a high-fat diet-induced AS mice model and over-express pinX1 via adenovirus tail vein injection to evaluate the regulation of pinX1 and pinX1 regulated p66shc in AS. This study will provide a new candidate target for the treatment of AS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

The overexpressing adenovirus and the negative controls were designed, validated, and synthesized by Hanbio (Shanghai, China). The selected interference vector was pAdEasy-U6-CMV-EGFP (EcoRI to MCS), and the pAdEasy-EF1-3flag-CMV-EGFP vector was used for pinX1 overexpression. Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, United States).

2.2. Animals and experiment design

Male eight-week-old Apoe-/- mice with a C57BL/6N background were used to establish AS mice model. Before the experiments, the animals were allowed to suit the new environment for 7 days and housed in a room under a 12 h light/dark cycle, a controlled temperature at 22 ± 3°C, and relative humidity at 60±10%. High-fat diet (HFD) was a commercially prepared mouse food (MD12017) supplemented with 20.0% (wt/wt) coco fat, 1.25% (wt/wt) cholesterol, and 22.5% (wt/wt) protein and 45.0% carbohydrate (Jiangsu Medicience Ltd., Jiangsu, China).

Mice were randomly divided into three groups, control group was fed with normal diet. AS model were established via HFD treatment for 16 weeks. pinX1 overexpression was conducted by injection of pinX1-overexpressing adenovirus through the tail vein for every two week. At week 16, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Forene®, Abbott), one milliliter of blood was collected by abdominal aorta, and tissues were collected for further analysis.

2.3. Ethics statement

The animals were purchased from Viewsolid Biotech Co., Ltd [Beijing, China; Catalog No. vsm40001]. All experiments were approved by the animal care and use committee of Chongqing Three Gorges Medical College (approval no. SYYZ-A-2212-0002), and the animal care and treatment were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Publication No. 85-23, Revised 1985).

2.4. Oil red O staining

The aortic arch and thoracic and abdominal aortae were cut longitudinally and pinned flat. Tissues were rinsed in PBS and 60% isopropanol and stained in oil-red O. Lesion size was calculated as a ratio of oil-red O positive staining to the total surface area.

2.5. HE staining

The upper half of the heart that contained the aortic origin was fixed at 10% buffered formalin solution for 30 min and then dehydrated in 75% ethanol overnight, followed by paraffin embedding. For morphometric analysis of atherosclerotic lesions, serial 4 μm sections were cut. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic analysis.

2.6. Biochemical Analysis

Serum triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), liver-free fatty acid (FFA), serum superoxide dismutase (SOD), MDA, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and glutathione (GSH) levels were detected using commercialized testing kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biotechnology, Nanjing, China) based on the manufacturers’ instruction.

2.7. Western Blot

Tissues were harvested and protein extracts were prepared according to established methods. Extracts were separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels (8~15%) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk and then incubated with indicated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing, the membranes were then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies. The membranes were exposed to enhanced chemiluminescence plus reagents (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China). The emitted light was captured by a Bio-Rad imaging system with a Chemi HR camera 410 and analyzed with a Gel-Pro Analyzer Version 4.0 (Media Cybernetics, MD, USA).

2.8. Real-time PCR analysis

TRIzol reagent was used to extract tissue RNA. Next, cDNA Synthesis Mix was mixed with 1 μg of RNA for 15 min at 50 ℃ and then 5 min at 85 ℃. At the end of the reaction, the cDNA, TSINGKE master qPCR Mix and 10 pmol of forward and reverse primers were mixed and subsequently analyzed for target gene mRNA levels. The relative quantification of mRNA was normalized to gapdh.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from more than three independent experiments, and data analyses were performed with the SPSS software package, version 19.0. Comparison of quantitative variables was performed by either Student’s t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Student Newman-Keuls (SNK) test. p values < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

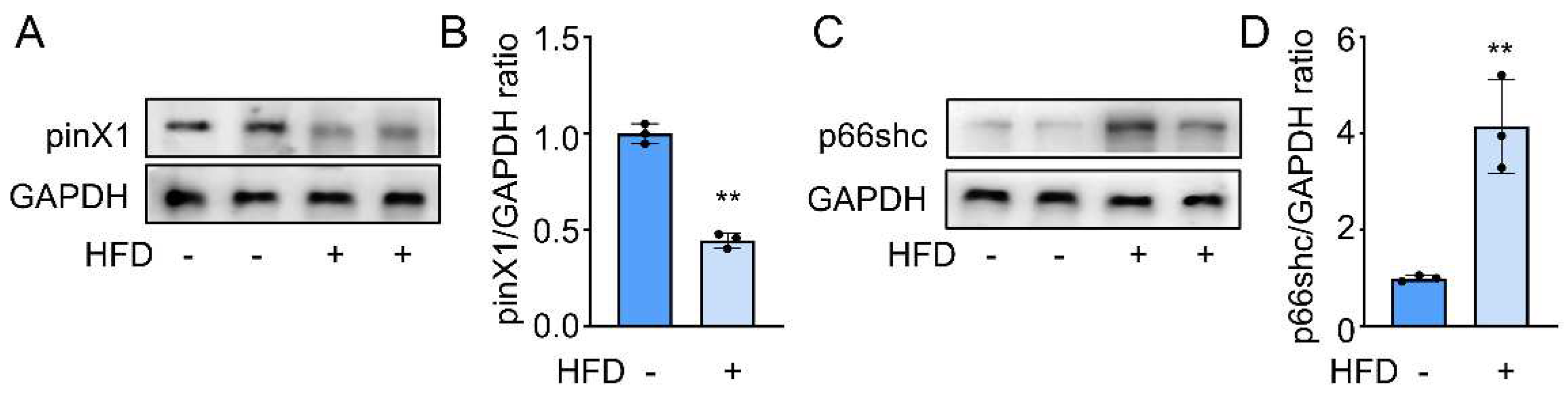

3.1. Decreased pinX1 and increased p66shc were detected in Apoe-/- mice.

Differential expression is the foundation of protein function research. Thus, After the successful establishment of the AS model, we first confirmed the differential expression of pinX1 and p66shc in the HFD group and the control group. As expected, decreased pinX1 (

Figure 1A) and increased p66shc protein expression (

Figure 1B) were determined in the HFD group compared to that in the control group. These results indicated a potential role of pinX1 and p66shc during AS progress.

3.2. Increased pinX1 protein expression attenuated AS progress.

As shown in

Figure 2A, the pinX1 protein was overexpressed as excepted. Aortic lesions were measured by using oil-red O staining. The lesions in HFD group mice were grossly larger and thicker, pinX1 overexpression group could reduce the lesion area and the thickness in the whole aorta especially in the aortic arch (

Figure 2B,C). Then, the intimal lesions were further evaluated under microscopy. HE staining indicated a worse intimal lesion area enriched in macrophage-derived foam cells in HFD group compared with that in pinX1 overexpression group, calcification of the aortic valve was also decreased after pinX1 overexpression (

Figure 2D). The results indicated that overexpression of pinX1 attenuated the development of atherosclerotic lesions.

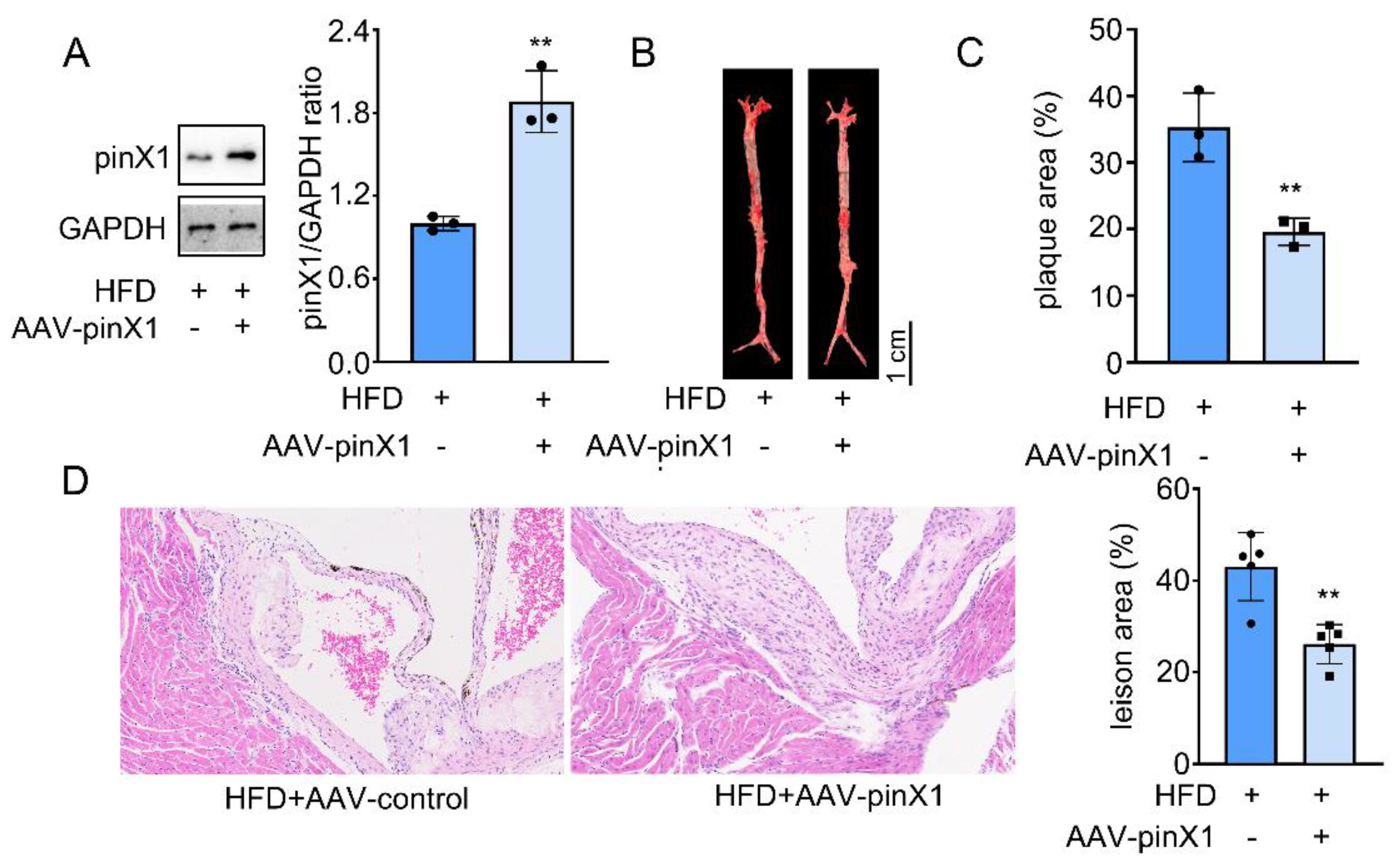

3.3. PinX1 overexpression ameliorated the lipid expression profile

The serum levels of TC, LDLc, HDLc, TG, and FFA were determined to investigate the effect of pinX1 on lipid profiles. Compared with HFD group, pinX1 overexpression significantly decreased serum TG (

Figure 3A), TC (

Figure 3B), FFA (

Figure 3C), and LDLc levels (

Figure 3D), while HDLc was increased (

Figure 3E) in pinX1 overexpression group. Additionally, the LDLc/HDLc ratio was remarkedly decreased in pinX1 overexpression group compared with HFD group (

Figure 3F). The above results indicated that pinX1 could improve lipid profiles in Apoe-/- mice.

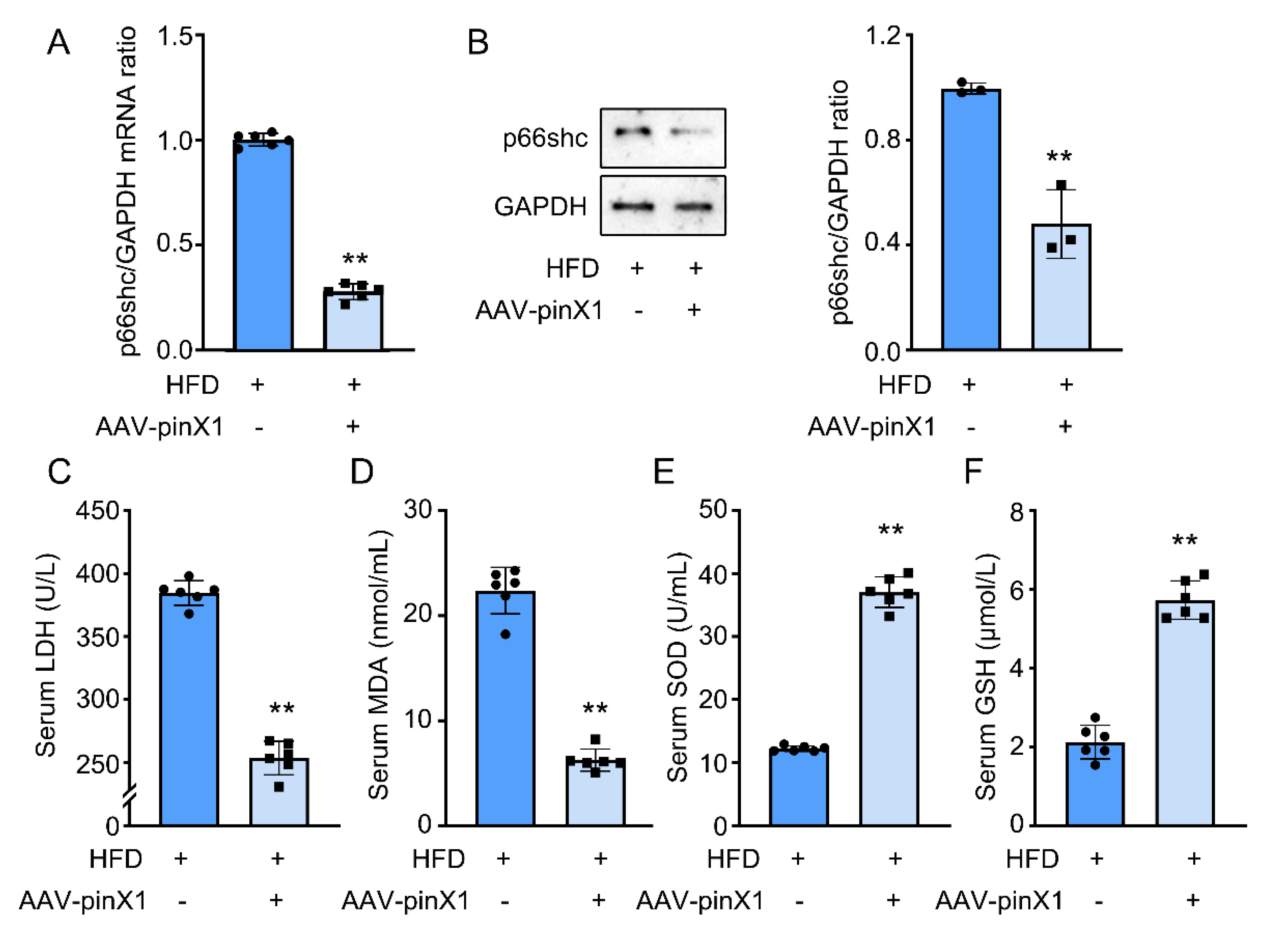

3.4. PinX1 inhibited p66shc mRNA and protein expression, and attenuated oxidative stress in Apoe-/- mice.

Telomere and mitochondrion cross-talk have been reported in a previous study, whether pinX1 can affect p66shc expression remains unclear. Thus, p66shc mRNA and protein expression were detected. Interestingly, compared with the HFD group, pinX1 overexpression significantly inhibited p66shc mRNA (

Figure 4A) and protein (

Figure 4B) expression. This result indicated that p66shc mRNA and protein expression can negatively regulate by pinX1.

Oxidative stress has been considered an important factor in the pathophysiology of AS and can be mediated by p66shc. Serum levels of SOD and GSH were significantly increased in the pinX1 overexpression group compared with the HFD group (

Figure 4E,F). However, serum LDH and MDA levels were obviously decreased in the pinX1 overexpression group compared with the HFD group (

Figure 4D,E). These results indicated the potential antioxidant effect of pinX1 in Apoe-/- mice.

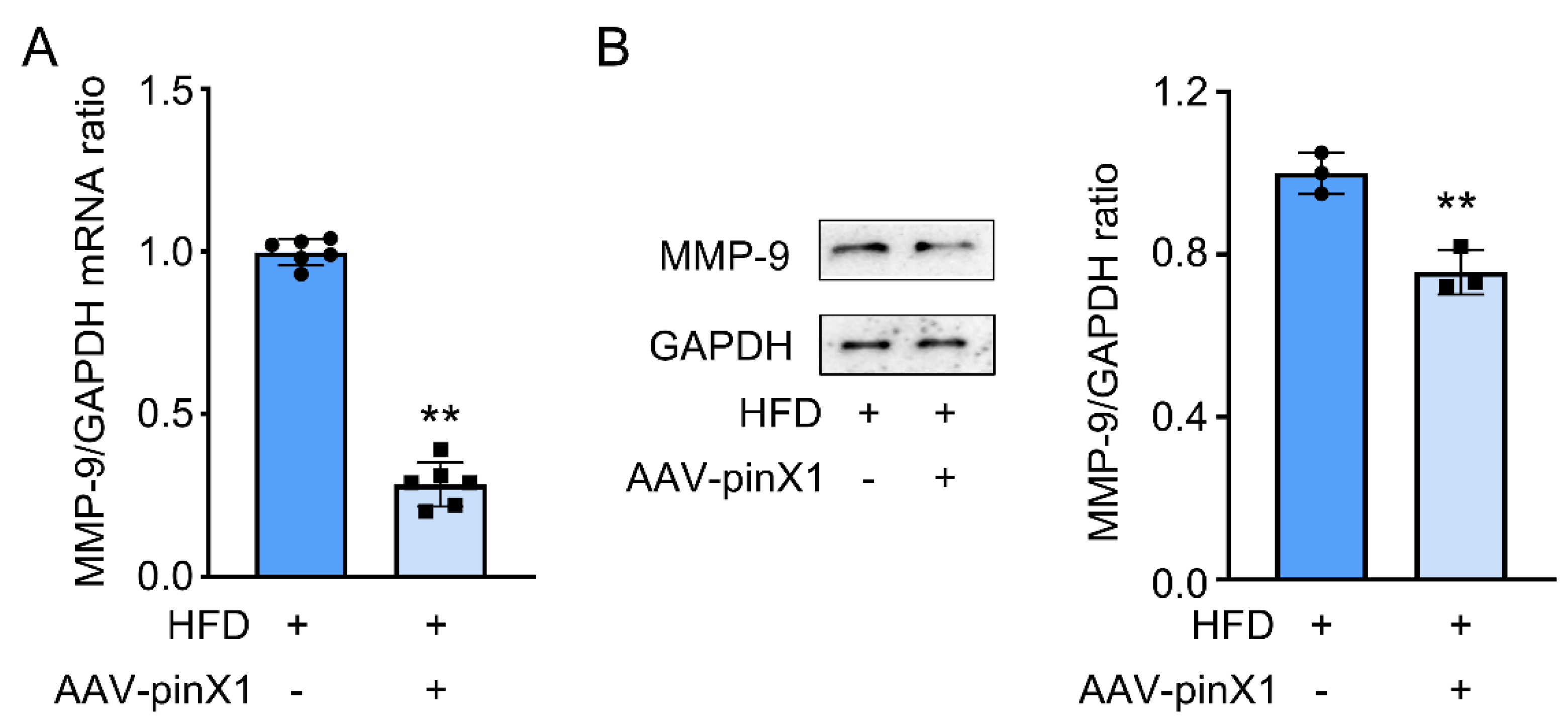

3.5. PinX1 inhibited serum and vascular MMP-9 protein expression in Apoe-/- mice.

A previous study indicated the potential correlation between pinX1 and MMP-9 [

12]. MMP-9 is a key marker to evaluate AS progress and plaque stability, thus, MMP-9 protein expression was evaluated using Western Blot. Similar to the expected results, pinX1 overexpression significantly inhibited MMP-9 protein expression (

Figure 5A,B). The above results showed the potential regulatory effect of pinX1 on MMP-9.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the role of pinX1 and its regulated p66shc in HFD-induced Apoe-/- mice. Importantly, we first described the decreased expression of pinX1 in this classical AS mice model. Moreover, by overexpressing pinX1, we found that pinX1 can inhibit p66shc expression and oxidative stress, then ameliorate AS. As we know, this is the first time to describe the effect of pinX1 in AS and its potential role in regulating oxidative stress. All in all, our study suggests that pinX1 may be a new candidate target for the treatment of AS and oxidative stress-related diseases.

Oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation are widely accepted factors in aging-related diseases [

25]. AS was considered a chronic degenerative disease closely related to aging [

26,

27]. In a previous study, we investigated the role and function of telomerase in AS-related macrophages. The results showed a mutual regulatory effect between PGC-1α and TERT which also indicates the cross-talk between mitochondria and telomere [

5]. PinX1 is known as the most powerful inhibitor of telomerase. The role of pinX1 in various cancer regulation has been elucidated, and some clues indicated its role in lipid regulation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Based on these, we hypothesize pinX1 may play some roles in AS progress. In this study, we established a classical AS mice model, and overexpressed pinX1 investigate the role of pinX1. As expected, detected the decreased expression of pinX1 in a classical AS mice model induced by HFD in Apoe-/- mice. For pinX1 is an effective inhibitor of TERT [

28], we think that the inhibitory expression of TERT in AS which is detected in previous study [

5] may be regulated by some other factors besides pinX1. Of course, in this study, we didn’t detect TERT protein expression, the inconsistency in TERT expression may also be caused by different stages of the disease course or fluctuations in experimental conditions.

Oxidative stress is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defense capacity [

29]. P66shc encoded by the human and mouse ShcA locus, is a ubiquitously expressed vertebrate protein [

30]. It sustains the intracellular concentration of ROS by catalyzing their formation from the mitochondrial respiratory chain, triggering plasma membrane oxidases and suppressing ROS scavenging [

31]. Increased expression of p66shc protein has been detected in AS and nonalcohol fatty liver disease [

32] which is coincident with our study. Moreover, downregulating of p66shc also improved the expression of SOD and GSH, as well as decreased MDA and LDH release. In this study, we first found that pinX1 can negatively regulate p66shc, which also indicates the potential anti-oxidative stress effect of pinX1.

In our experiment from Apoe-/- mice, overexpression of pinX1 significantly inhibited MMP-9 protein expression. MMP-9 is a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases, which is lowly expressed in normal human tissues, but MMP-9 is up-regulated during some normal physiological regulation or pathological remodeling [

33]. Data from human epidemiological and genetic studies suggest that MMP-9 is the strongest candidate for inducing plaque rupture, and its expression is closely related to lesion instability and clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis. Since MMP-9 is able to extensively degrade extra cellular matrix components (such as collagenase, gelatin, laminin, and fibronectin) in the arterial wall, it plays an important role in the regulation of AS plaque formation and plaque stability. It has been reported in the literature that in human AS lesions, increased levels of MMP-9 expression have been detected [

34]. MMP-9 is mainly synthesized and secreted by macrophages and neutrophils, as well as vascular smooth muscle cells, and is involved in the regulation of cell survival, migration, inflammation, and angiogenesis[

35,

36]. In a study based on breast cancer, increased expression of pinX1 is negatively correlated with MMP-9 protein expression[

12]. This is consistent with the results obtained in this study, however, whether pinX1-induced down-regulation of MMP-9 depends on NF-κB is not discussed in this study. Moreover, in accordance with the data from HE staining, overexpressed pinX1 remarkedly reduced plaque area, increased plaque stability, reduced plaque calcification levels, and decreased the number of macrophages in the plaque. Although we did not focus on macrophages in this study, from the source and function of MMP-9, we infer that macrophages play important roles in pinX1-mediated AS progress.

However, there are still some limitations to this study. We described the negative regulatory effect of pinX1 on p66shc, however, whether it is a direct regulation and the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Moreover, whether the inhibitory effect of pinX1 on oxidative stress depends on p66shc still needs to be verified through more detailed cell experiments.

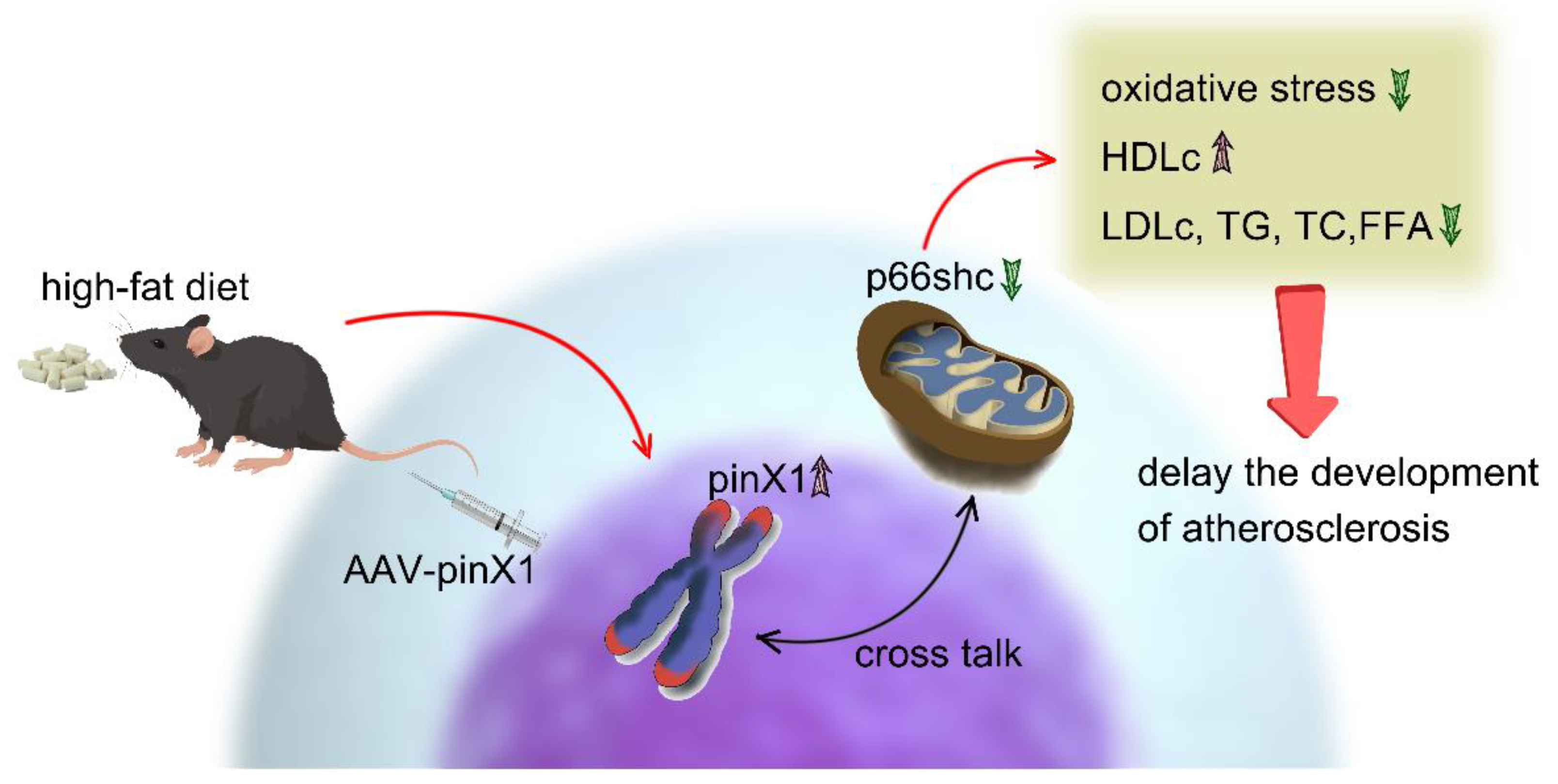

5. Conclusions

Taken together, this study demonstrated that pinX1 protein expression can inhibit MMP-9, p66shc expression, and inhibiting oxidative stress, so as to slow down the course of AS (

Figure 6). thus, we think, pinX1 may be a new candidate target for the treatment of AS via inhibiting MMP-9 and p66shc expression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yukun Zhang and Yang Yao; Data curation, Yukun Zhang and Hongxia Song; Formal analysis, Hongxia Song and Qiaoling Zhang; Funding acquisition, Yukun Zhang and Yang Yao; Methodology, Yukun Zhang and Yang Yao; Project administration, Yukun Zhang; Resources, Yukun Zhang; Supervision, Yukun Zhang; Validation, Yukun Zhang, Yang Yao and Qiaoling Zhang; Visualization, Yang Yao; Writing – original draft, Yang Yao and Qiaoling Zhang; Writing – review & editing, Yukun Zhang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chongqing Municipal Science and Technology Situation Project (cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0299), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJZD-K202002701), and Chongqing Natural Drug Anti-tumor Innovation Research Group (CXQT20030).

Institutional Review Board Statement

the animal study protocol was approved by the animal care and use committee of Chongqing Three Gorges Medical College (approval no. SYYZ-A-2212-0002).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

the raw data or analyzed data during the current study would be available from the corresponding author Yukun Zhang on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author reports no declaration of interest.

References

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Ren, J.; Yang, L. Advances of nanomedicine in treatment of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Environmental research 2023, 116637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, G.K.; Hermansson, A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nature immunology 2011, 12, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadlec, A.O.; Chabowski, D.S.; Ait-Aissa, K.; Gutterman, D.D. Role of PGC-1α in Vascular Regulation: Implications for Atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2016, 36, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Yang, Q.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Dai, Y.; Cai, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, K.; et al. Activating the PGC-1α/TERT Pathway by Catalpol Ameliorates Atherosclerosis via Modulating ROS Production, DNA Damage, and Telomere Function: Implications on Mitochondria and Telomere Link. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2018, 2018, 2876350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Hesketh, A.; Pouch-Pélissier, M.N.; Pélissier, T.; Huang, Y.; Latrasse, D.; Benhamed, M.; Mathieu, O. RTEL1 is required for silencing and epigenome stability. Nucleic acids research 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.Z. PinX1: A sought-after major tumor suppressor at human chromosome 8p23. Oncotarget 2011, 2, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosto, G.; Vardarajan, B.; Sariya, S.; Brickman, A.M.; Andrews, H.; Manly, J.J.; Schupf, N.; Reyes-Dumeyer, D.; Lantigua, R.; Bennett, D.A.; et al. Association of Variants in PINX1 and TREM2 With Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease. JAMA neurology 2019, 76, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.T.; Jin, R.; Cheung, D.H.; Huang, J.J.; Shaw, P.C. The PinX1/NPM interaction associates with hTERT in early-S phase and facilitates telomerase activation. Cell & bioscience 2019, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Cai, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhong, Q.; Feng, J.; Li, J.; Shen, C.; Wen, Z. Pin2 telomeric repeat factor 1-interacting telomerase inhibitor 1 (PinX1) inhibits nasopharyngeal cancer cell stemness: Implication for cancer progression and therapeutic targeting. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 2020, 39, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Z.; Huang, P.; Shi, R.; Lee, T.H.; Lu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Bronson, R.; Lu, K.P. The telomerase inhibitor PinX1 is a major haploinsufficient tumor suppressor essential for chromosome stability in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2011, 121, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Cao, M.; Song, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Meng, F.; Pan, Z.; Bai, J.; Zheng, J. PinX1 inhibits the invasion and metastasis of human breast cancer via suppressing NF-κB/MMP-9 signaling pathway. Molecular cancer 2015, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Qian, D.; He, L.R.; Li, Y.H.; Liao, Y.J.; Mai, S.J.; Tian, X.P.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Kung, H.F.; et al. PinX1 suppresses bladder urothelial carcinoma cell proliferation via the inhibition of telomerase activity and p16/cyclin D1 pathway. Molecular cancer 2013, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, B.; Yu, H.; Song, D. Regulation of PINX1 expression ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury and alleviates cell senescence during the convalescent phase through affecting the telomerase activity. Aging 2021, 13, 10175–10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Ren, Q.; Yue, L.; Niu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhu, R.; Chen, X.; Jia, Z.; et al. UTP14A, DKC1, DDX10, PinX1, and ESF1 Modulate Cardiac Angiogenesis Leading to Obesity-Induced Cardiac Injury. Journal of diabetes research 2022, 2022, 2923291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Xu, K.; Gu, X.; Zhu, Q. PinX1 Depletion Improves Liver Injury in a Mouse Model of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Increasing Telomerase Activity and Inhibiting Apoptosis. Cytogenetic and genome research 2021, 161, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Yin, R.X.; Huang, F.; Yang, D.Z.; Lin, W.X.; Pan, S.L. Association between the PINX1 and NAT2 polymorphisms and serum lipid levels. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 114081–114094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, N.; Giambartolomei, C.; de Vries, P.S.; Finan, C.; Bis, J.C.; Huntley, R.P.; Lovering, R.C.; Tajuddin, S.M.; Winkler, T.W.; Graff, M.; et al. GWAS and colocalization analyses implicate carotid intima-media thickness and carotid plaque loci in cardiovascular outcomes. Nature communications 2018, 9, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslem, L.; Hays, J.M.; Hays, F.A. p66Shc in Cardiovascular Pathology. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. P66Shc and vascular endothelial function. Bioscience reports 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paneni, F.; Cosentino, F. p66 Shc as the engine of vascular aging. Current vascular pharmacology 2012, 10, 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilenberg, W.; Stojkovic, S.; Kaider, A.; Piechota-Polanczyk, A.; Nanobachvili, J.; Domenig, C.M.; Wojta, J.; Huk, I.; Demyanets, S.; Neumayer, C. Neutrophil Gelatinase Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) for Identification of Unstable Plaques in Patients with Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : The official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2019, 57, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Gadi, I.; Nazir, S.; Al-Dabet, M.M.; Kohli, S.; Bock, F.; Breitenstein, L.; Ranjan, S.; Fuchs, T.; Halloul, Z.; et al. Activated protein C reverses epigenetically sustained p66(Shc) expression in plaque-associated macrophages in diabetes. Communications biology 2018, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xia, J.; Cheng, J.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Su, X.; Ke, Y.; Ling, W. Inhibition of S-Adenosylhomocysteine Hydrolase Induces Endothelial Dysfunction via Epigenetic Regulation of p66shc-Mediated Oxidative Stress Pathway. Circulation 2019, 139, 2260–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.K.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; You, C.L.; Yun, C.E.; Jeong, H.J.; Jin, E.J.; Jo, Y.; Ryu, D.; Bae, G.U.; et al. Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 1 Ablation in Motor Neurons Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction Leading to Age-related Motor Neuron Degeneration with Muscle Loss. Research (Washington, D.C.) 2023, 6, 0158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fularski, P.; Krzemińska, J.; Lewandowska, N.; Młynarska, E.; Saar, M.; Wronka, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Statins in Chronic Kidney Disease-Effects on Atherosclerosis and Cellular Senescence. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, V.; de Mol, J.; Schaftenaar, F.H.; Depuydt, M.A.C.; Postel, R.J.; Smeets, D.; Verheijen, F.W.M.; Bogers, L.; van Duijn, J.; Verwilligen, R.A.F.; et al. Single-cell profiling reveals age-associated immunity in atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular research 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.F.; Shen, C.X.; Wen, Z.; Qian, Y.H.; Yu, C.S.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhong, P.N.; Wang, H.L. PinX1 regulation of telomerase activity and apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 2012, 31, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, C.S.; Engl, T.; Matarrita-Carranza, B.; Vogler, P.; Huettel, B.; Wielsch, N.; Svatoš, A.; Kaltenpoth, M. Host hydrocarbons protect symbiont transmission from a radical host defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2023, 120, e2302721120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, H.A.; Ali, R.; Mushtaq, U.; Khanday, F.A. Structure-functional implications of longevity protein p66Shc in health and disease. Ageing research reviews 2020, 63, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, D.; Zhao, H.; Lin, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lv, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhai, X.; et al. p66Shc Contributes to Liver Fibrosis through the Regulation of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, J.; Jin, Y.; Xu, C.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Dong, D.; Ma, X.; Liu, K.; et al. Targeting of miR-96-5p by catalpol ameliorates oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in LDLr-/- mice via p66shc/cytochrome C cascade. Aging 2020, 12, 2049–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgezawi, M.; Haridy, R.; Almas, K.; Abdalla, M.A.; Omar, O.; Abuohashish, H.; Elembaby, A.; Christine Wölfle, U.; Siddiqui, Y.; Kaisarly, D. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Dental and Periodontal Tissues and Their Current Inhibitors: Developmental, Degradational and Pathological Aspects. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Nooijer, R.; Verkleij, C.J.; von der Thüsen, J.H.; Jukema, J.W.; van der Wall, E.E.; van Berkel, T.J.; Baker, A.H.; Biessen, E.A. Lesional overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 promotes intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced lesions but not at earlier stages of atherogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2006, 26, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, P.; Shang, G. Targeting matrix metalloproteinases by E3 ubiquitin ligases as a way to regulate the tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Seminars in cancer biology 2022, 86, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessenbrock, K.; Plaks, V.; Werb, Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: Regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2010, 141, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).