Submitted:

26 July 2023

Posted:

27 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

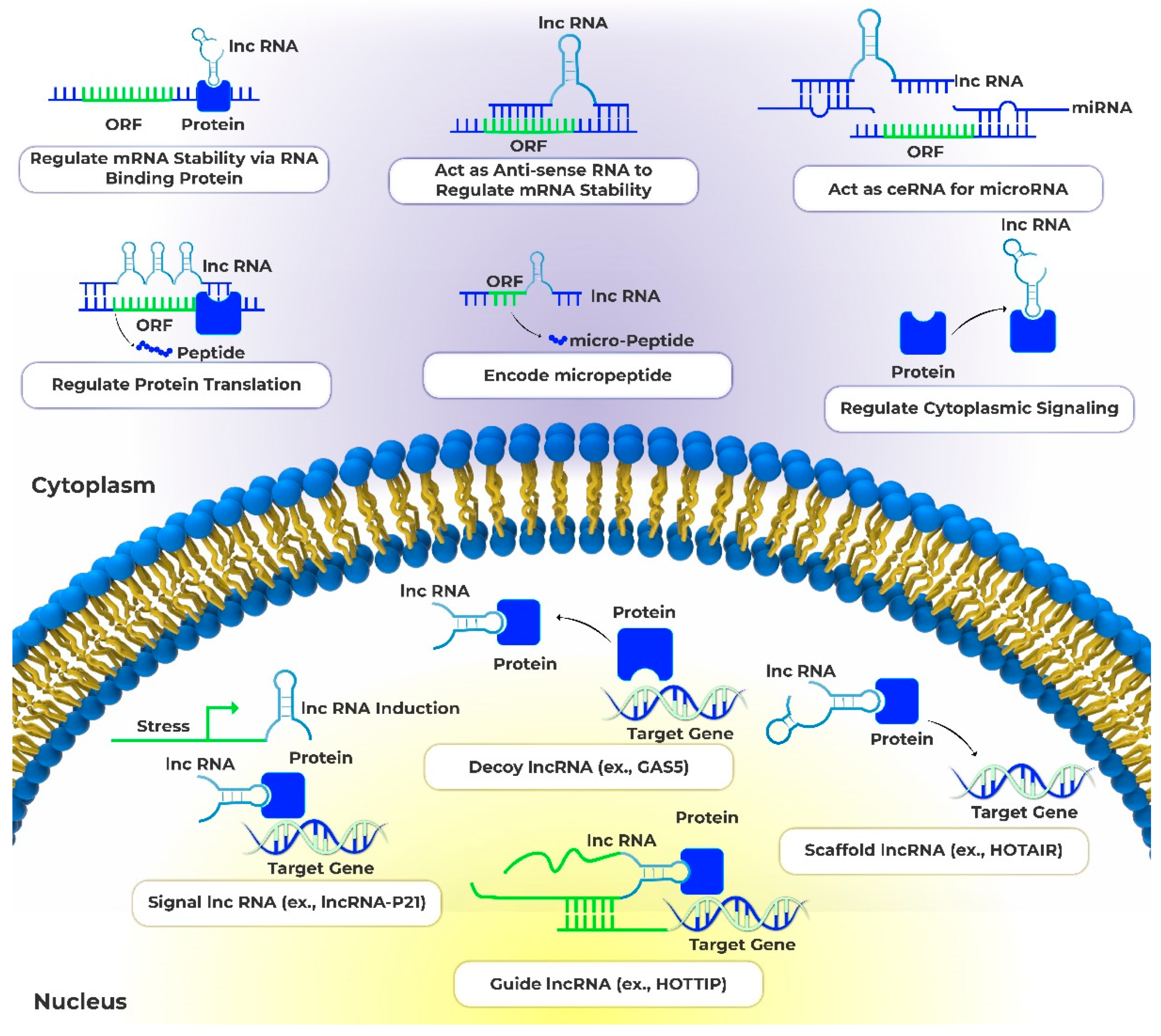

2. lncRNAs function

3. Myc and breast cancer

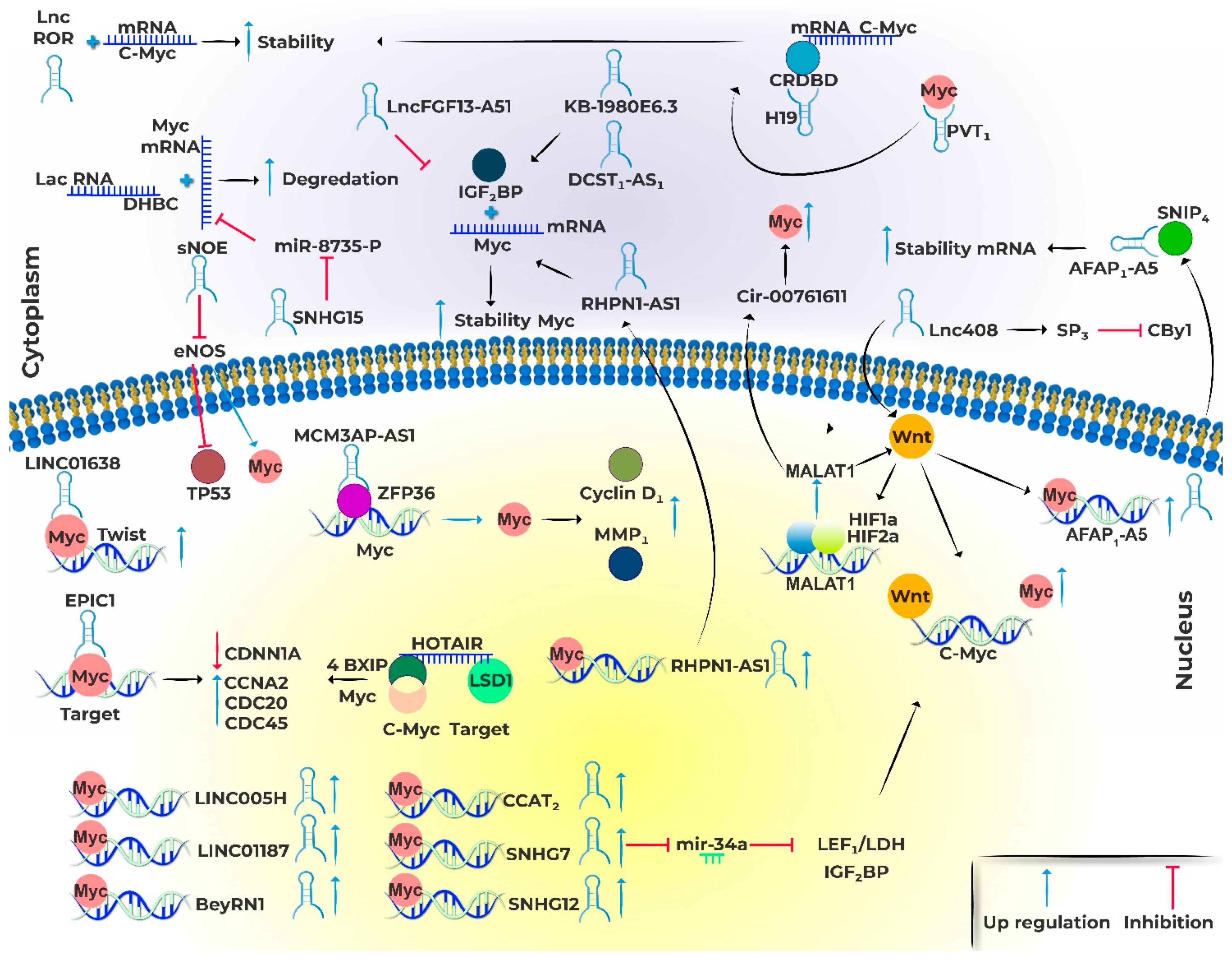

4. Myc and lncRNAs

5. The relationship between lncRNAs and MYC in BC

5.1. lncRNAs regulated by MYC

SNHG7

SNHG12

BCYRN1

5.2. LncRNAs affecting MYC Expression

MALAT1

LacRNA

Linc00839

Lnc408

LINC01287

MCM3AP-AS1

LINC00511

sONE

PICART1

5.3. MYC-lncRNAs regulatory loops

CCAT2

EPIC1

HOTAIR

RHPN1-AS1

5.4. LncRNAs affecting MYC stability/translation

AFAP1-AS1

LINC01638

SNHG15

Linc-RoR

KB-1980E6.3

H19

DCST1-AS1

PVT1

FGF13-AS1

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madden, S.K.; de Araujo, A.D.; Gerhardt, M.; Fairlie, D.P.; Mason, J.M. Taking the Myc out of cancer: toward therapeutic strategies to directly inhibit c-Myc. Molecular Cancer 2021, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.; Yuan, M.; Yang, B.; He, Q.; Cao, J. Targeting Myc Interacting Proteins as a Winding Path in Cancer Therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, R.; Deutzmann, A.; Mahauad-Fernandez, W.D.; Hansen, A.S.; Gouw, A.M.; Felsher, D.W. The MYC oncogene — the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune evasion. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2022, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.J.; O'Grady, S.; Tang, M.; Crown, J. MYC as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2021, 94, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart, V.; Mansour, M.R. Therapeutic targeting of "undruggable" MYC. eBioMedicine 2022, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, F.X.; Dhankani, V.; Berger, A.C.; Trivedi, M.; Richardson, A.B.; Shaw, R.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Ventura, A.; Liu, Y.; et al. Pan-cancer Alterations of the MYC Oncogene and Its Proximal Network across the Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell Systems 2018, 6, 282–300e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, D.; Brambillasca, C.S.; Talens, F.; Bhin, J.; Linstra, R.; Romanens, L.; Bhattacharya, A.; Joosten, S.E.P.; Da Silva, A.M.; Padrao, N.; et al. MYC promotes immune-suppression in triple-negative BC via inhibition of interferon signaling. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.V. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodir, N.M.; Swigart, L.B.; Karnezis, A.N.; Hanahan, D.; Evan, G.I.; Soucek, L. Endogenous Myc maintains the tumor microenvironment. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massó-Vallés, D.; Beaulieu, M.-E.; Jauset, T.; Giuntini, F.; Zacarías-Fluck, M.F.; Foradada, L.; Martínez-Martín, S.; Serrano, E.; Martín-Fernández, G.; Casacuberta-Serra, S.; et al. MYC Inhibition Halts Metastatic BC Progression by Blocking Growth, Invasion, and Seeding. Cancer Research Communications 2022, 2, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Jiang, M.; Guo, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, S.; Yeung, Y.T.; Yang, R.; Wang, K.; Wu, Q.; et al. A novel lncRNA MTAR1 promotes cancer development through IGF2BPs mediated post-transcriptional regulation of c-MYC. Oncogene 2022, 41, 4736–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, C.; Resetca, D.; Redel, C.; Lin, P.; MacDonald, A.S.; Ciaccio, R.; Kenney, T.M.G.; Wei, Y.; Andrews, D.W.; Sunnerhagen, M.; et al. MYC protein interactors in gene transcription and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2021, 21, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, M.; Mousavi, S.H.; Rafiee, M.; Heidari, R.; Shahrokhi, S.Z. Biochemical and molecular biomarkers: unraveling their role in gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2023, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacovetti, C.; Bayazit, M.B.; Regazzi, R. Emerging Classes of Small Non-Coding RNAs With Potential Implications in Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, R.; Akbariqomi, M.; Asgari, Y.; Ebrahimi, D.; Alinejad-Rokny, H. A systematic review of long non-coding RNAs with a potential role in BC. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2021, 787, 108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, R.; Akbariqomi, M.; Asgari, Y.; Ebrahimi, D.; Alinejad-Rokny, H. A systematic review of long non-coding RNAs with a potential role in BC. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2021, 787, 108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahariya, S.; Paddibhatla, I.; Kumar, S.; Raghuwanshi, S.; Pallepati, A.; Gutti, R.K. Long non-coding RNA: Classification, biogenesis and functions in blood cells. Mol Immunol 2019, 112, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, X.; Glass, C.K.; Rosenfeld, M.G. The long arm of long noncoding RNAs: roles as sensors regulating gene transcriptional programs. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2011, 3, a003756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.J.; Chang, H.Y. Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nature Reviews Genetics 2016, 17, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Deng, L.; Huang, N.; Sun, F. The Biological Roles of lncRNAs and Future Prospects in Clinical Application. Diseases 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortlever, R.M.; Sodir, N.M.; Wilson, C.H.; Burkhart, D.L.; Pellegrinet, L.; Brown Swigart, L.; Littlewood, T.D.; Evan, G.I. Myc Cooperates with Ras by Programming Inflammation and Immune Suppression. Cell 2017, 171, 1301–1315e1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallah, Y.; Brundage, J.; Allegakoen, P.; Shajahan-Haq, A.N. MYC-Driven Pathways in BC Subtypes. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risom, T.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Zhang, X.; Pelz, C.; Campbell, L.G.; Eng, J.; Chin, K.; Farrington, C.; Narla, G.; et al. Deregulating MYC in a model of HER2+ BC mimics human intertumoral heterogeneity. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.M.; Giltnane, J.M.; Balko, J.M.; Schwarz, L.J.; Guerrero-Zotano, A.L.; Hutchinson, K.E.; Nixon, M.J.; Estrada, M.V.; Sánchez, V.; Sanders, M.E.; et al. MYC and MCL1 Cooperatively Promote Chemotherapy-Resistant BC Stem Cells via Regulation of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cell Metab 2017, 26, 633–647e637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.A. Socializing with MYC: cell competition in development and as a model for premalignant cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2014, 4, a014274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzaler, P.; Clarke, M.A.; Brown, E.J.; Wilson, C.H.; Kortlever, R.M.; Piterman, N.; Littlewood, T.; Evan, G.I.; Fisher, J. Heterogeneity of Myc expression in BC exposes pharmacological vulnerabilities revealed through executable mechanistic modeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 22399–22408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziato, S.; de Ruiter, J.R.; Henneman, L.; Brambillasca, C.S.; Lutz, C.; Vaillant, F.; Ferrante, F.; Drenth, A.P.; van der Burg, E.; Siteur, B.; et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies combinations of driver genes and drug targets in BRCA1-mutated BC. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Saha, D.; Dash, J.; Chatterjee, T.K. Poly-l-Lysine inhibits VEGF and c-Myc mediated tumor-angiogenesis and induces apoptosis in 2D and 3D tumor microenvironment of both MDA-MB-231 and B16F10 induced mice model. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 183, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Song, Y.; Tang, L.; Sun, D.H.; Ji, D.G. LncRNA SNHG7 promotes development of BC by regulating microRNA-186. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2018, 22, 7788–7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Ji, W.; Xu, B.; Huang, W.; Jiao, J.; Shao, J.; Zhang, X. The role of long noncoding RNA SNHG7 in human cancers (Review). Mol Clin Oncol 2020, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.H.; Yu, N.S.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.Y.; Liu, G.; Huang, K. LncRNA SNHG7 Mediates the Chemoresistance and Stemness of BC by Sponging miR-34a. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 592757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Long, Z.; Wu, S.; Xiao, M.; Hu, W. LncRNA-SNHG7 regulates proliferation, apoptosis and invasion of bladder cancer cells assurance guidelines. J buon 2018, 23, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Najafi, S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Hussen, B.M.; Jamal, H.H.; Taheri, M.; Hallajnejad, M. Oncogenic Roles of Small Nucleolar RNA Host Gene 7 (SNHG7) Long Noncoding RNA in Human Cancers and Potentials. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.T.; Zhou, Y.C. Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) small nucleolar RNA host gene 7 (SNHG7) promotes BC progression by sponging miRNA-381. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 6588–6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Wei, Y. LncRNA SNHG7 inhibits proliferation and invasion of BC cells by regulating miR-15a expression. J BUON 2020, 25, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, B.; Tang, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, Y.; et al. SNHG7: A novel vital oncogenic lncRNA in human cancers. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 124, 109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destefanis, F.; Manara, V.; Bellosta, P. Myc as a Regulator of Ribosome Biogenesis and Cell Competition: A Link to Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, Y.; Guo, H. c-Myc-Induced Long Non-Coding RNA Small Nucleolar RNA Host Gene 7 Regulates Glycolysis in BC. J BC 2019, 22, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, G. Knockdown of lncRNA SNHG12 suppresses cell proliferation, migration and invasion in BC by sponging miR-451a. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2020, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Hou, X.; Han, D.; et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG12 is a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in various tumors. Chinese Neurosurgical Journal 2021, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamang, S.; Acharya, V.; Roy, D.; Sharma, R.; Aryaa, A.; Sharma, U.; Khandelwal, A.; Prakash, H.; Vasquez, K.M.; Jain, A. SNHG12: An LncRNA as a Potential Therapeutic Target and Biomarker for Human Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, O.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Lv, L.; Ma, R.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Tan, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Xia, E.; et al. C-MYC-induced upregulation of lncRNA SNHG12 regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis and migration in triple-negative BC. Am J Transl Res 2017, 9, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iacoangeli, A.; Lin, Y.; Morley, E.J.; Muslimov, I.A.; Bianchi, R.; Reilly, J.; Weedon, J.; Diallo, R.; Böcker, W.; Tiedge, H. BC200 RNA in invasive and preinvasive BC. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, M.; Santucci-Pereira, J.; Vaccaro, O.G.; Nguyen, T.; Su, Y.; Russo, J. BC200 overexpression contributes to luminal and triple negative BC pathogenesis. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booy, E.P.; McRae, E.K.S.; Koul, A.; Lin, F.; McKenna, S.A. The long non-coding RNA BC200 (BCYRN1) is critical for cancer cell survival and proliferation. Molecular Cancer 2017, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gupta, S.C.; Peng, W.X.; Zhou, N.; Pochampally, R.; Atfi, A.; Watabe, K.; Lu, Z.; Mo, Y.Y. Regulation of alternative splicing of Bcl-x by BC200 contributes to BC pathogenesis. Cell Death & Disease 2016, 7, e2262–e2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Lu, Y.R. BCYRN1, a c-MYC-activated long non-coding RNA, regulates cell metastasis of non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell Int 2015, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, N.; Raimondi, L.; Juli, G.; Stamato, M.A.; Caracciolo, D.; Tagliaferri, P.; Tassone, P. MALAT1: a druggable long non-coding RNA for targeted anti-cancer approaches. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2018, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Piao, H.L.; Kim, B.J.; Yao, F.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Siverly, A.N.; Lawhon, S.E.; Ton, B.N.; et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 suppresses BC metastasis. Nat Genet 2018, 50, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-H.; Chuang, L.-L.; Tsai, M.-H.; Chen, L.-H.; Chuang, E.Y.; Lu, T.-P.; Lai, L.-C. Hypoxia-Induced MALAT1 Promotes the Proliferation and Migration of BC Cells by Sponging MiR-3064-5p. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Katsaros, D.; Biglia, N.; Shen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Loo, L.W.M.; Jia, W.; Obata, Y.; Yu, H. High expression of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 in BC is associated with poor relapse-free survival. BC Res Treat 2018, 171, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiu, B.; Huang, S.; Chi, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, J.; et al. LINC00478-derived novel cytoplasmic lncRNA LacRNA stabilizes PHB2 and suppresses BC metastasis via repressing MYC targets. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Su, Y.-H.; Xue, J.-y.; Si, J.; Chi, Y.-y.; Wu, J. Abstract P6-05-01: A novel cleaved cytoplasmic lncRNA LacRNA interacts with PHB2 and suppresses BC metastasis via repressing MYC targets. Cancer Research 2019, 79, P6–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.L.; Zou, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.J.; Cao, J.; Xiong, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Cheng, X.S.; Xiao, Q.Z.; Yang, R.Q. Functional role and molecular mechanisms underlying prohibitin 2 in platelet mitophagy and activation. Mol Med Rep 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiu, B.; Huang, S.; Chi, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, J.; et al. LINC00478-derived novel cytoplasmic lncRNA LacRNA stabilizes PHB2 and suppresses BC metastasis via repressing MYC targets. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Long, X.; Lan, J.; Zhou, M.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, J. LINC00839 promotes colorectal cancer progression by recruiting RUVBL1/Tip60 complexes to activate NRF1. EMBO Rep 2022, 23, e54128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Deng, L.; Wang, Y.-D. Roles and Mechanisms of Long Non-Coding RNAs in BC. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Xiong, S.; Chi, H.; Xu, W. A nuclear lncRNA Linc00839 as a Myc target to promote BC chemoresistance via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Sci 2020, 111, 3279–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Qin, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, L.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, P.; Li, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. A novel Lnc408 maintains BC stem cell stemness by recruiting SP3 to suppress CBY1 transcription and increasing nuclear β-catenin levels. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, D. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates cancer stem cells in lung cancer A549 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 392, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.; Qin, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, L.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, P.; Li, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. A novel Lnc408 maintains BC stem cell stemness by recruiting SP3 to suppress CBY1 transcription and increasing nuclear β-catenin levels. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Sun, P.; He, Q.; Liu, L.L.; Cui, J.; Sun, L.M. Long non-coding RNA LINC01287 promotes BC cells proliferation and metastasis by activating Wnt/ß-catenin signaling. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 4234–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; He, L.; Lai, Z.; Wan, Z.; Chen, Q.; Pan, S.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Huang, J.; Xue, F.; et al. LINC01287 regulates tumorigenesis and invasion via miR-298/MYB in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 5477–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.P.; Qin, C.X.; Yu, H. MCM3AP-AS1 regulates proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion of BC cells via binding with ZFP36. Transl Cancer Res 2021, 10, 4478–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhu, J.; Feng, K.; Hu, C. LncRNA MCM3AP-AS1 promotes BC progression via modulating miR-28-5p/CENPF axis. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 128, 110289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Khoshbakht, T.; Hussen, B.M.; Taheri, M.; Samadian, M. A review on the role of MCM3AP-AS1 in the carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Cancer Cell International 2022, 22, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Guo, W. MCM3AP-AS1: An Indispensable Cancer-Related LncRNA. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Han, G.; Song, Z.; Zang, A.; Liu, B.; Hu, L.; Jia, L.; Hong, D.; Yang, L.; Qie, S. LncRNA MCM3AP-AS1 Downregulates LncRNA MEG3 in Triple Negative BC to Inhibit the Proliferation of Cancer Cells. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2021, 31, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Qin, Q.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Q.; Luo, Z.; et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00511 contributes to BC tumourigenesis and stemness by inducing the miR-185-3p/E2F1/Nanog axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018, 37, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, S.; Hong, X. Long non-coding RNA LINC00511/miR-150/MMP13 axis promotes BC proliferation, migration and invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2021, 1867, 165957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lu, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Qin, Q.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Q.; Luo, Z.; et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00511 contributes to BC tumourigenesis and stemness by inducing the miR-185-3p/E2F1/Nanog axis. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 37, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Meng, F.; Fu, L.; Kong, C. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA linc00511 suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis of bladder cancer cells via suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biosci Rep 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youness, R.A.; Assal, R.A.; Abdel Motaal, A.; Gad, M.Z. A novel role of sONE/NOS3/NO signaling cascade in mediating hydrogen sulphide bilateral effects on triple negative BC progression. Nitric Oxide 2018, 80, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youness, R.A.; Hafez, H.M.; Khallaf, E.; Assal, R.A.; Abdel Motaal, A.; Gad, M.Z. The long noncoding RNA sONE represses triple-negative BC aggressiveness through inducing the expression of miR-34a, miR-15a, miR-16, and let-7a. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 20286–20297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lin, M.; Bu, Y.; Ling, H.; He, Y.; Huang, C.; Shen, Y.; Song, B.; Cao, D. p53-inducible long non-coding RNA PICART1 mediates cancer cell proliferation and migration. Int J Oncol 2017, 50, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsu, O.; McCormick, F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature 1999, 398, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Nian, W.Q.; Wang, L.L.; Li, L.C.; Luo, H.L.; Wang, D.L. Long non-coding RNA CCAT2 promotes the BC growth and metastasis by regulating TGF-β signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017, 21, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caia, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, D. Suppression of long non-coding RNA CCAT2 improves tamoxifen-resistant BC cells’ response to tamoxifen. Molecular Biology 2016, 50, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Gu, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, B.; Feng, M.; Wang, X. Long noncoding RNA CCAT2 reduces chemosensitivity to 5-fluorouracil in BC cells by activating the mTOR axis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2022, 26, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Lü, J.; Ding, X.; Luo, A.; He, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; et al. Long non-coding RNA CCAT2 promotes oncogenesis in triple-negative BC by regulating stemness of cancer cells. Pharmacol Res 2020, 152, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Song, G. Upregulation of CCAT2 promotes cell proliferation by repressing the P15 in BC. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 91, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, S.; Guo, B. Vitamin D suppresses ovarian cancer growth and invasion by targeting long non-coding RNA CCAT2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Guo, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Gu, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, P.; et al. Dual Function of CCAT2 in Regulating Luminal Subtype of BC Depending on the Subcellular Distribution. Cancers 2023, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, D. Long noncoding RNA CCAT2 promotes breast tumor growth by regulating the Wnt signaling pathway. OncoTargets and therapy 2015, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Sheng, X.; Sha, R.; Dai, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Predictive and prognostic value of EPIC1 in patients with BC receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2020, 12, 1758835920940886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Guo, W.; Yang, D. MYC-binding lncRNA EPIC1 promotes AKT-mTORC1 signaling and rapamycin resistance in breast and ovarian cancer. Mol Carcinog 2020, 59, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Li, S.; Xie, W.; Yang, D. lncRNA Epigenetic Landscape Analysis Identifies EPIC1 as an Oncogenic lncRNA that Interacts with MYC and Promotes Cell-Cycle Progression in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 706–720e709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chaurasia, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yadav, G.S.; Rathod, S.; et al. LincRNA-immunity landscape analysis identifies EPIC1 as a regulator of tumor immune evasion and immunotherapy resistance. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Li, S.; Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N.; Xie, W.; et al. lncRNA Epigenetic Landscape Analysis Identifies EPIC1 as an Oncogenic lncRNA that Interacts with MYC and Promotes Cell-Cycle Progression in Cancer. Cancer cell 2018, 33, 706–720e709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Li, S.; Caesar-Johnson, S.J.; Demchok, J.A.; et al. lncRNA Epigenetic Landscape Analysis Identifies EPIC1 as an Oncogenic lncRNA that Interacts with MYC and Promotes Cell-Cycle Progression in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 706–720e709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Fei, Q.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Guo, C.; Ren, Y.; Mei, M.; et al. lncRNA HOTAIR Promotes DNA Repair and Radioresistance of BC via EZH2. DNA Cell Biol 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Fang, R.; Cai, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Ye, L. HBXIP and LSD1 Scaffolded by lncRNA Hotair Mediate Transcriptional Activation by c-Myc. Cancer Res 2016, 76, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłowska, E.; Szczepanska, J.; Blasiak, J. The Long Noncoding RNA HOTAIR in BC: Does Autophagy Play a Role? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Tang, W. The molecular mechanism of HOTAIR in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and drug resistance. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2014, 46, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, G.; Jayawickramarajah, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Shan, B. Functions of lncRNA HOTAIR in lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2014, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. c-Myc induced the regulation of long non-coding RNA RHPN1-AS1 on BC cell proliferation via inhibiting P53. Mol Genet Genomics 2019, 294, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lv, P.; Su, J.; Miao, K.; Xu, H.; Li, M. Silencing of the long non-coding RNA RHPN1-AS1 suppresses the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and inhibits BC progression. Am J Transl Res 2019, 11, 3505–3517. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Chen, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, D. Up-regulated lncRNA AFAP1-AS1 indicates a poor prognosis and promotes carcinogenesis of BC. BC 2019, 26, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LncRNA AFAP1-AS1 Knockdown Represses Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Induced Apoptosis in BC by Downregulating SEPT2 Via Sponging miR-497-5p. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals 2022, 37, 662–672. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, F.; Lin, Y.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Q. Long noncoding RNA AFAP1-AS1 promotes tumor progression and invasion by regulating the miR-2110/Sp1 axis in triple-negative BC. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, L.; Xiong, F.; He, Y.; Tang, Y.; Shi, L.; Fan, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; et al. Long non-coding RNA AFAP1-AS1 accelerates lung cancer cells migration and invasion by interacting with SNIP1 to upregulate c-Myc. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Tang, H.; Ling, L.; Li, N.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Yin, J.; Qiu, N.; et al. LINC01638 lncRNA activates MTDH-Twist1 signaling by preventing SPOP-mediated c-Myc degradation in triple-negative BC. Oncogene 2018, 37, 6166–6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Luan, X.; Han, G.; Guo, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. LINC01638 lncRNA mediates the postoperative distant recurrence of bladder cancer by upregulating ROCK2. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 5392–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Tang, H.; Wu, J.; Qiu, X.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xie, X.; Xiao, X. Linc01638 Promotes Tumorigenesis in HER2+ BC. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2019, 19, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.; Kaochar, S.; Li, M.; Rajapakshe, K.; Fiskus, W.; Dong, J.; Foley, C.; Dong, B.; Zhang, L.; Kwon, O.J.; et al. SPOP regulates prostate epithelial cell proliferation and promotes ubiquitination and turnover of c-MYC oncoprotein. Oncogene 2017, 36, 4767–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Qiu, M. Long noncoding RNA SNHG15 promotes human BC proliferation, migration and invasion by sponging miR-211-3p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 495, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.B.; Jiang, Z.J.; Jiang, X.L.; Wang, S. Up-regulation of SNHG15 facilitates cell proliferation, migration, invasion and suppresses cell apoptosis in BC by regulating miR-411-5p/VASP axis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 1899–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Xiang, H.; Peng, Z.; Ma, Z.; Shen, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, L.; Cao, D.; Gu, S.; Wang, M.; et al. Silencing the expression of lncRNA SNHG15 may be a novel therapeutic approach in human BC through regulating miR-345-5p. Annals of Translational Medicine 2022, 10, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Li, L.; Zhu, M.; Wang, N.; Xiong, Y.; Gu, Y. SNHG15 Contributes To Cisplatin Resistance In BC Through Sponging miR-381. Onco Targets Ther 2020, 13, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeinasab, M.; Bahrami, A.R.; González, J.; Marchese, F.P.; Martinez, D.; Mowla, S.J.; Matin, M.M.; Huarte, M. SNHG15 is a bifunctional MYC-regulated noncoding locus encoding a lncRNA that promotes cell proliferation, invasion and drug resistance in colorectal cancer by interacting with AIF. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 38, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhong, H.; Ma, B. Targeting a novel LncRNA SNHG15/miR-451/c-Myc signaling cascade is effective to hamper the pathogenesis of BC (BC) in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell International 2021, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Zhong, H.; Ma, B. Targeting a novel LncRNA SNHG15/miR-451/c-Myc signaling cascade is effective to hamper the pathogenesis of BC (BC) in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell Int 2021, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewer, S.; Cabili, M.N.; Guttman, M.; Loh, Y.H.; Thomas, K.; Park, I.H.; Garber, M.; Curran, M.; Onder, T.; Agarwal, S.; et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet 2010, 42, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Flores, J.A.; Enríquez-Espinoza, D.; Muela-Campos, D.; Álvarez-Ramírez, A.; Sáenz, A.; Barraza-Gómez, A.A.; Bravo, K.; Estrada-Macías, M.E.; González-Alvarado, K. Functional Relevance of the Long Intergenic Non-Coding RNA Regulator of Reprogramming (Linc-ROR) in Cancer Proliferation, Metastasis, and Drug Resistance. Non-Coding RNA 2023, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhu, H.; Tang, L.; Gao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Gong, F.; Tan, Y.; Xie, L.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Apatinib Inhibits Stem Properties and Malignant Biological Behaviors of BC Stem Cells by Blocking Wnt/β-catenin Signal Pathway through Downregulating LncRNA ROR. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 22, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Tu, J.; Cheng, F.; Yang, H.; Yu, F.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Fan, J.; Zhou, G. Long noncoding RNA ROR promotes BC by regulating the TGF-β pathway. Cancer Cell International 2018, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, A.; Ho, T.T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, N.; Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Mo, Y.Y. Linc-RoR promotes c-Myc expression through hnRNP I and AUF1. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, J.-W.; Kung, H.-J. Long non-coding RNA and tumor hypoxia: new players ushered toward an old arena. Journal of Biomedical Science 2017, 24, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.-y.; Li, X.-t.; Xu, K.; Wang, R.-t.; Guan, X.-x. c-MYC mediates the crosstalk between BC cells and tumor microenvironment. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Tang, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Zhu, P.; Jiang, K.; Tu, G. Long noncoding RNA KB-1980E6.3 promotes BC progression through the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Pathology - Research and Practice 2022, 234, 153891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; He, F.; Hou, Y.; Tu, G.; Li, Q.; Jin, T.; Zeng, H.; Qin, Y.; Wan, X.; Qiao, Y.; et al. A novel hypoxic long noncoding RNA KB-1980E6.3 maintains BC stem cell stemness via interacting with IGF2BP1 to facilitate c-Myc mRNA stability. Oncogene 2021, 40, 1609–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, H.; Yu, G.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, T.; Song, T.; Liu, C. Mild chronic hypoxia-induced HIF-2α interacts with c-MYC through competition with HIF-1α to induce hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation. Cellular Oncology 2021, 44, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, F.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, W.; Lin, S.; Yang, P.; Huang, M.; Wang, C. Genetic variants in long noncoding RNA H19 contribute to the risk of BC in a southeast China Han population. Onco Targets Ther 2017, 10, 4369–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reik, W.; Walter, J. Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nature Reviews Genetics 2001, 2, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, C.R.; Doyle, G.A.; Clark, B.A.; Pitot, H.C.; Ross, J. Mammary tumor induction in transgenic mice expressing an RNA-binding protein. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsyte-Lovejoy, D.; Lau, S.K.; Boutros, P.C.; Khosravi, F.; Jurisica, I.; Andrulis, I.L.; Tsao, M.S.; Penn, L.Z. The c-Myc oncogene directly induces the H19 noncoding RNA by allele-specific binding to potentiate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 5330–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Yang, F. The role of long non-coding RNA H19 in BC. Oncol Lett 2020, 19, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsyte-Lovejoy, D.; Lau, S.K.; Boutros, P.C.; Khosravi, F.; Jurisica, I.; Andrulis, I.L.; Tsao, M.S.; Penn, L.Z. The c-Myc Oncogene Directly Induces the H19 Noncoding RNA by Allele-Specific Binding to Potentiate Tumorigenesis. Cancer Research 2006, 66, 5330–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, P.; Teng, H.; Lu, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, X. LncRNA DCST1-AS1 Promotes Endometrial Cancer Progression by Modulating the MiR-665/HOXB5 and MiR-873-5p/CADM1 Pathways. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zou, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X. Inhibition of lncRNA DCST1-AS1 suppresses proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells by increasing miR-874-3p expression. J Gene Med 2021, 23, e3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Y.; An, Y. LncRNA DCST1-AS1 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate FAIM2 expression by sponging miR-1254 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Sci (Lond) 2019, 133, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zou, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X. Inhibition of lncRNA DCST1-AS1 suppresses proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells by increasing miR-874-3p expression. The Journal of Gene Medicine 2021, 23, e3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chen, Y.; Tang, X.; Wei, D.; Xu, X.; Yan, F. Long Noncoding RNA DCST1-AS1 Promotes Cell Proliferation and Metastasis in Triple-negative BC by Forming a Positive Regulatory Loop with miR-873-5p and MYC. J Cancer 2020, 11, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Kuo, W.L.; Stilwell, J.L.; Takano, H.; Lapuk, A.V.; Fridlyand, J.; Mao, J.H.; Yu, M.; Miller, M.A.; Santos, J.L.; et al. Amplification of PVT1 contributes to the pathophysiology of ovarian and BC. Clin Cancer Res 2007, 13, 5745–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carramusa, L.; Contino, F.; Ferro, A.; Minafra, L.; Perconti, G.; Giallongo, A.; Feo, S. The PVT-1 oncogene is a Myc protein target that is overexpressed in transformed cells. J Cell Physiol 2007, 213, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Xu, J.; Sun, R.; Mumbach, M.R.; Carter, A.C.; Chen, Y.G.; Yost, K.E.; Kim, J.; He, J.; Nevins, S.A. Promoter of lncRNA gene PVT1 is a tumor-suppressor DNA boundary element. Cell 2018, 173, 1398–1412 e1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-Y.; Bagchi, A. The PVT1-MYC duet in cancer. Molecular & Cellular Oncology 2015, 2, e974467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, A.L.; Murray, C.D.; Temiz, N.A.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Bagchi, A. MYC and PVT1 synergize to regulate RSPO1 levels in BC. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Chadwick, M.; Qian, C. Long non-coding RNA FGF13-AS1 inhibits glycolysis and stemness properties of BC cells through FGF13-AS1/IGF2BPs/Myc feedback loop. Cancer Lett 2019, 450, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LncRNA | Function | Cellular mechanism(s) | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| lncRNAs regulated by MYC | |||

| SNHG7 | c-Myc binds to SNHG7 promoter | Cancer cell proliferation | Positive |

| SNHG12 | c-Myc direct regulated to SNHG7 expression | Cancer cell proliferation, tumor growth, migration, and invasion | Positive |

| BCYRN1 | BCYRN1 regulated by Myc | Cancer cell migration and invasion | Positive |

| lncRNAs affecting MYC Expression | |||

| LacRNA | LacRNA inhibits Myc activity LacRNA stabilizes PHB2 |

Cancer cell metastasis suppression | Negative |

| Linc00839 | Myc binds to Linc00839's promoter and activates its transcription Linc00839 increases the expression of Myc Linc00839 increases the Lin28B and activated the PI3K/AKT signaling |

cancer cell, proliferation, invasion, and migration | Positive |

| Lnc408 | Lnc408 recruits a SP3 Lnc408 suppresses CBY1 transcription |

Influences BC stem cells | Positive |

| LINC01287 | LINC01287 upregulates Myc expression activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling |

Cancer cell proliferation and metastatic | Positive |

| MCM3AP-AS1 | MCM3AP-AS1 binds ZFP36 and regulates Myc | Cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion | Positive |

| LINC00511 | LINC00511 activates Wnt/β-catenin, increasing the expression of c-Myc |

Cancer cell promoting stemness and invasiveness, inhibit apoptosis | Positive |

| sONE | Knocking down of sONE decreases in TP53 and increases in c-Myc sONE can alter tumor suppressors miRNAs (miR-34a, miR-15, miR-16, and let-7a) |

cancer cell proliferation, colony-forming ability, migration, and invasion capacities | Negative |

| MALAT1 | MALAT1 activates Wnt/β-catenin, increasing the expression of c-Myc |

tumor size, lymph metastasis, angiogenesis, stage tumor, progression and metastasis | Positive |

| PICART1 | PICART1 influencing the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin, activates the expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc | Cancer cell proliferation | Positive |

| MYC-lncRNAs regulatory loops | |||

| CCAT2 | CCAT2 regulates Myc expression. c-Myc binds to CCAT2 promoter | cancer cell proliferation migration and metastasis | Positive |

| EPIC1 | EPIC1 promotes Myc recruitment to its target genes. | Cancer cell proliferation | Positive |

| HOTAIR | HOTAIR contributes to EZH2 recruitment to the Myc promoter HOTAIR promoter enriched for both NF-kB and c-Myc binding sequences |

Cancer cell proliferation by regulating cell cycle and apoptosis | Positive |

| RHPN1-AS1 | RHPN1-AS1 is a molecular sponge of miR-4261 RHPN1-AS1 is a transcriptional target of c-Myc RHPN1-AS1 exerts tumorigenesis by regulating P53 expression via MDM2 gene. |

cancer cells proliferation | Positive |

| lncRNAs affecting MYC stability/translation | |||

| SNHG15 | SNHG15 is directly regulated by Myc | Cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Positive |

| Linc-RoR | linc-ROR increases c-Myc mRNA stability Linc-RoR activates Wnt/β-catenin |

Cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, drug resistance, and invasion | Positive |

| KB-1980E6.3 | It acts enhancing c-Myc mRNA stability via interaction with IGF2BP1 | Promote Cancer stem cell stemness, metabolic rewiring and tumorigenesis. | Positive |

| H19 | It acts enhancing c-Myc mRNA stability via interaction with CRD-BP | Cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Positive |

| DCST1-AS1 | MYC regulates DCST1-AS1 expression DCST1-AS1 interaction with miR-873-5p upregulated IGF2BP1, Myc , CD44 and LEF1 |

cancer cell proliferation and metastasis | Positive |

| LINC01638 | LINC01638 interacts with c-Myc to prevent SPOP-mediated to c-Myc ubiquitination | cancer cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT | Positive |

| AFAP1-AS1 | AFAP1-AS1 activated Wnt/β-catenin, increasing the expression of c-Myc AFAP1-AS1 interacts with SNIP1 to prevent c-Myc ubiquitination |

Cancer cell proliferation and invasion inhibited cell apoptosis |

Positive |

| PVT1 | PVT1 can enhance Myc protein stability They amplify each other in a molecular loop |

cancer cell proliferation and metastasis | Positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).