Submitted:

25 July 2023

Posted:

27 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Study of the sedimentary sequence of the archaeological site.

- Interpretation of the formation and transformation processes that gave rise to the current configuration of its archaeological record.

- Differentiation, to the extent possible, of natural processes (N transforms) and/or cultural processes of anthropic origin (C transforms) [11].

- Identification of sedimentary processes.

- Identification of diagenetic and postdepositional processes [12].

- Establishment of the geoarchaeological evolution of the site.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geomorphology

2.3. Lithostratigraphic study

2.4. Sedimentological analyses

- Laser granulometry for the fraction finer than 2 mm,

- Phi granulometry for the total sediment including the coarse section, and

- Mineralogical identification by means of X-ray diffraction (XRD) of the fraction finer than 0.63 mm.

- Suspension of a known quantity of each of the samples.

- Sample disintegration.

- Sieving at 700 μm, the upper limit of technical measurement capacity in laser granulometric equipment.

- Phi scale granulometry of the fractions greater than 700 μm with the 4, 2 and 1 mm mesh size sieves.

- Laser granulometry for fractions finer than 700 μm.

2.5. Soil analyses

2.6. Geochronology

3. Geomorphology

4. Geoarchaology

4.1. The lithostratigraphic sequence

4.2. Sedimentological and edaphological analysis

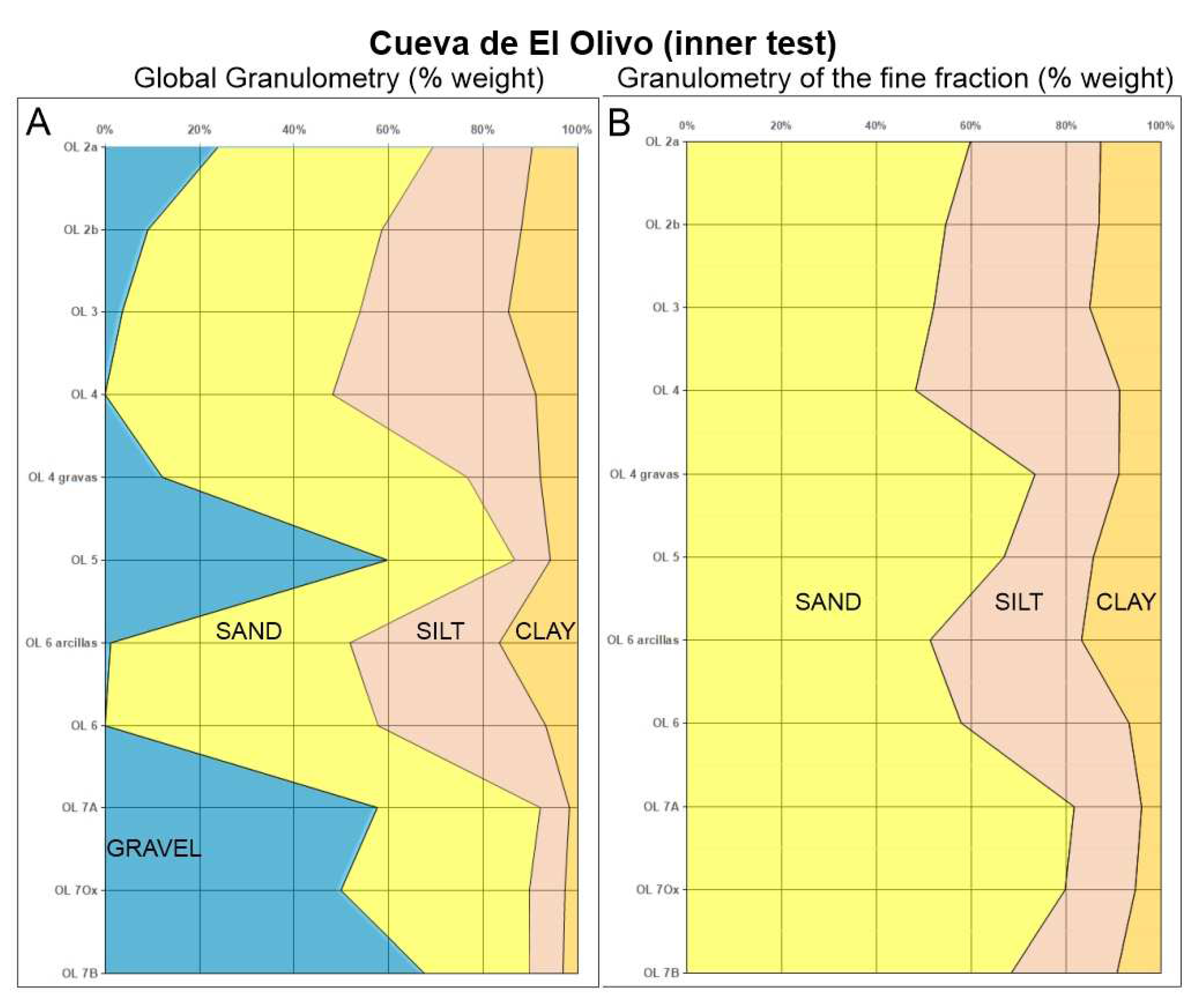

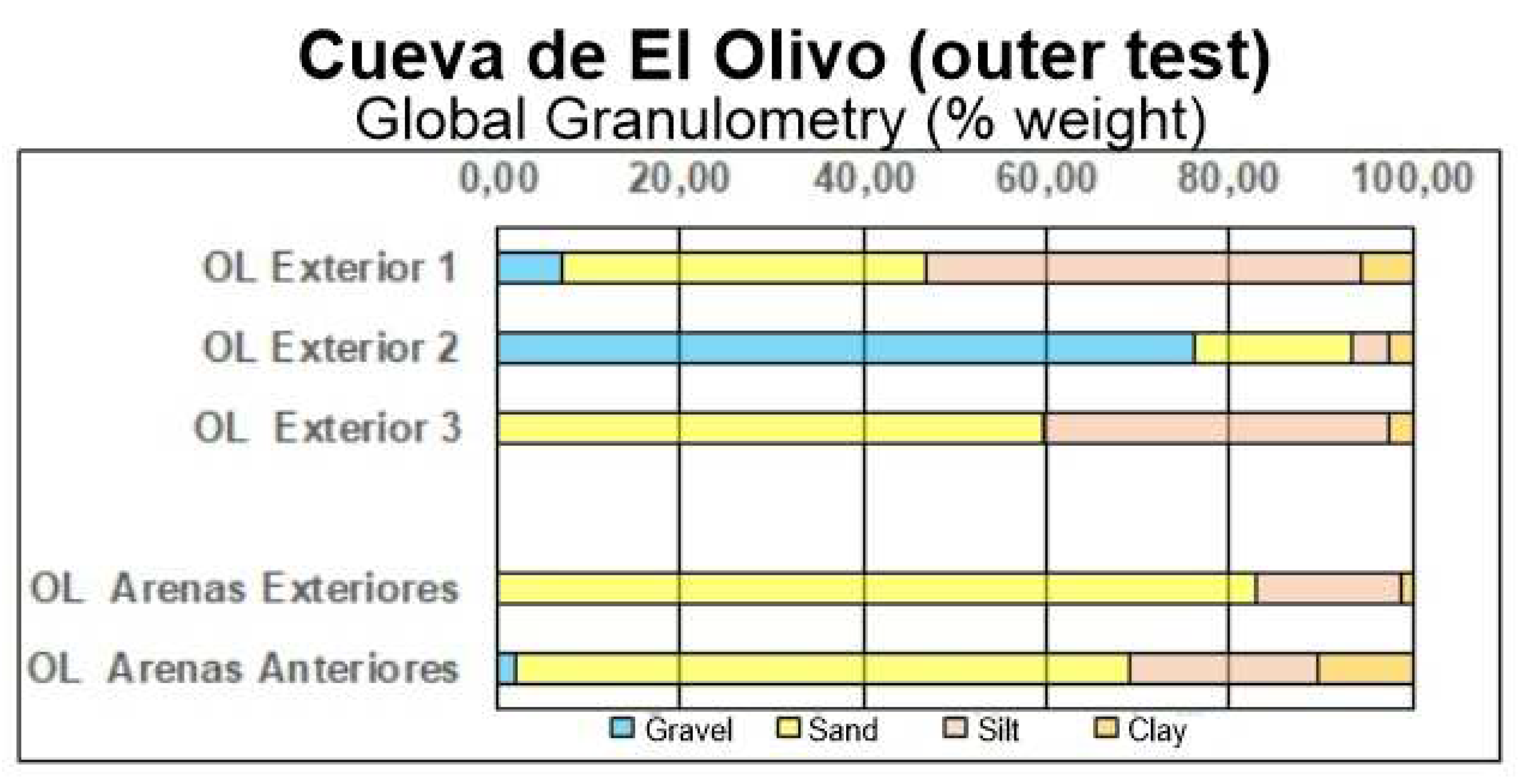

4.2.1. Granulometry

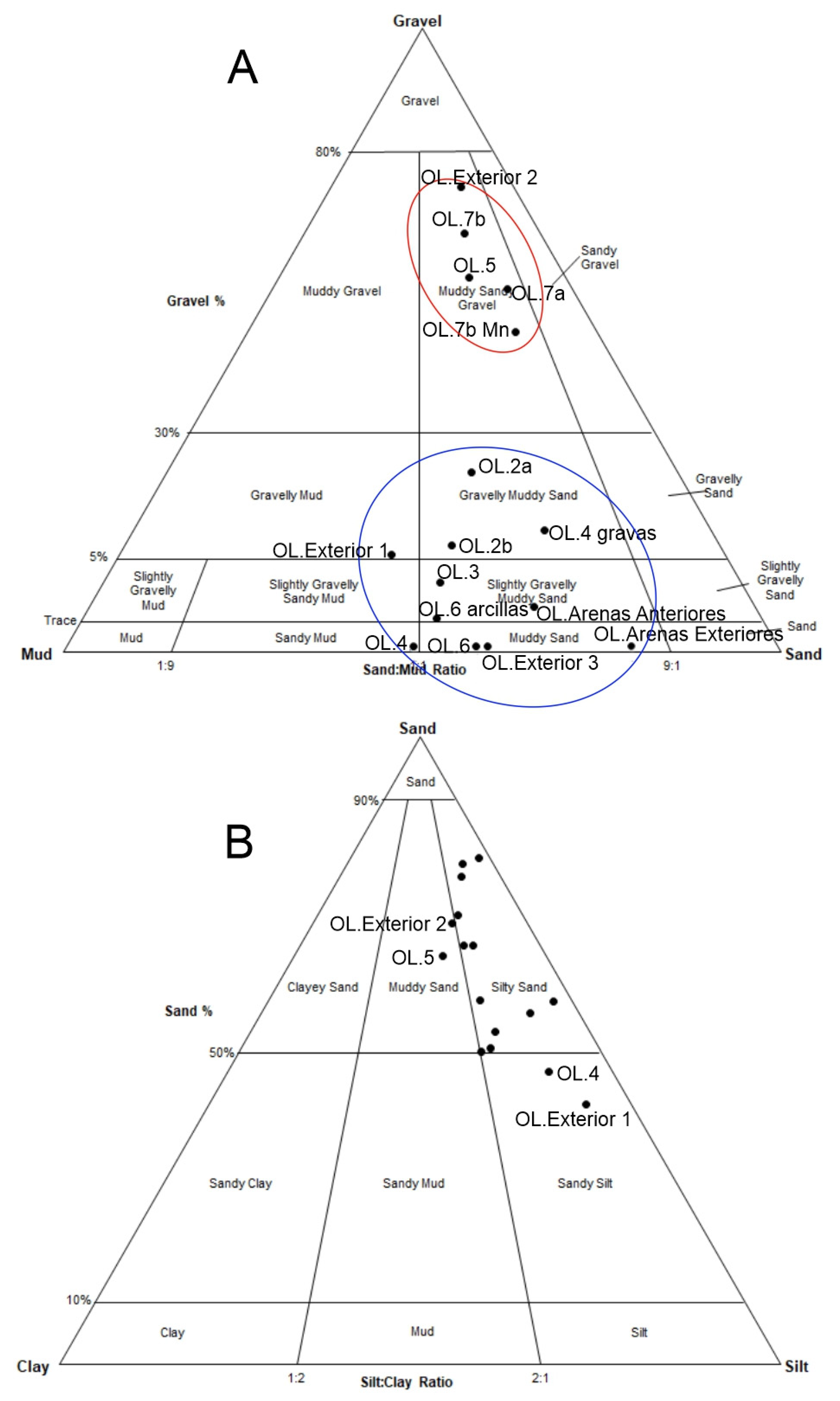

- Group A, which encompasses sediments from the textural group of muddy sandy gravel (OL.5, OL.7a, OL.7b, OL.7 Ox and OL.Exterior.2).

- Group B, consisting of sediments corresponding to the textural groups of gravelly muddy sand (OL.2a, OL.2b, OL.4 gravas), slightly gravelly muddy sand (OL3, Ol.6 arcillas, OL.Arenas anteriores), muddy sand (OL.6, OL.Exterior 3 and OL.Arenas Exteriores), gravelly mud (OL.Exterior 1) and sandy mud.

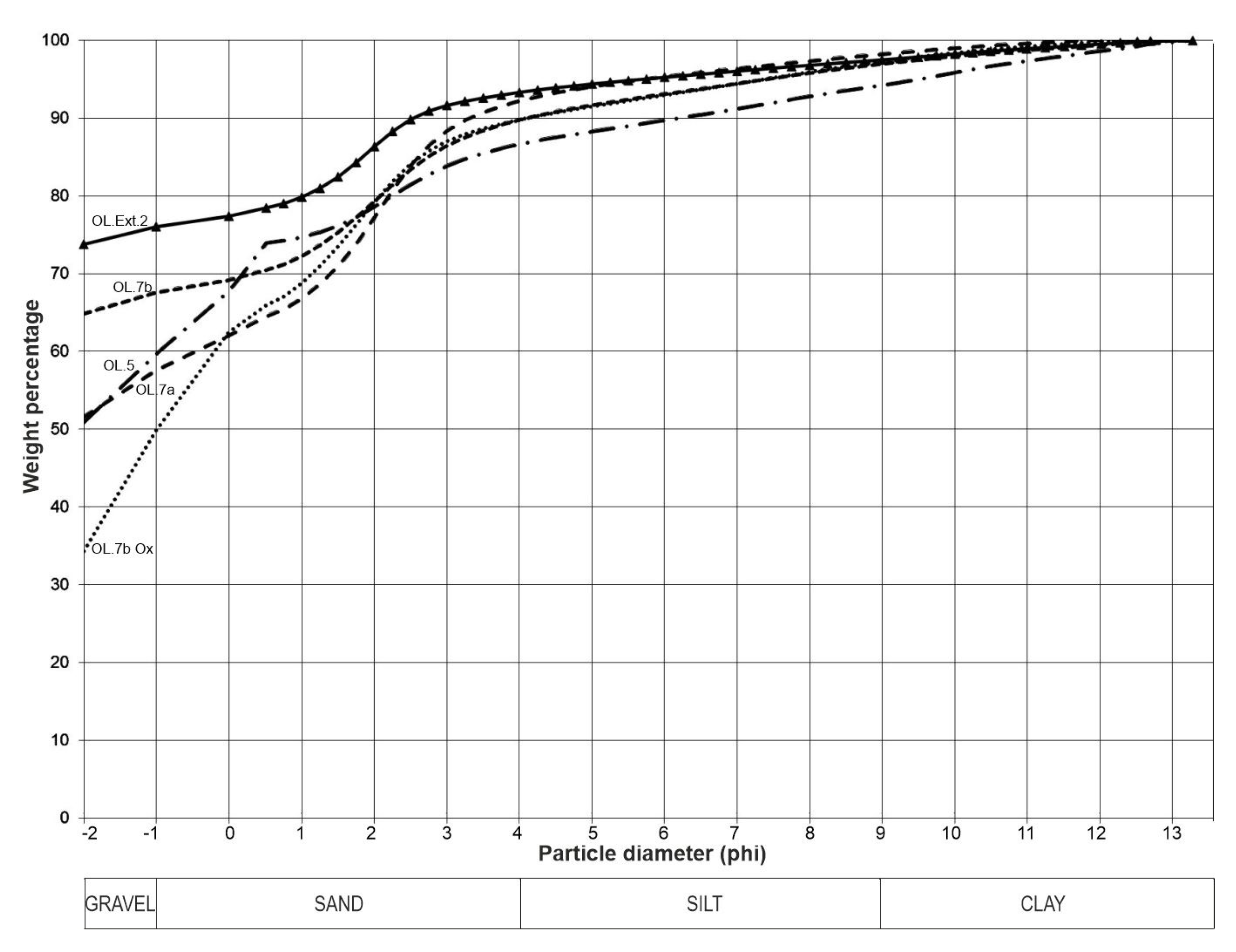

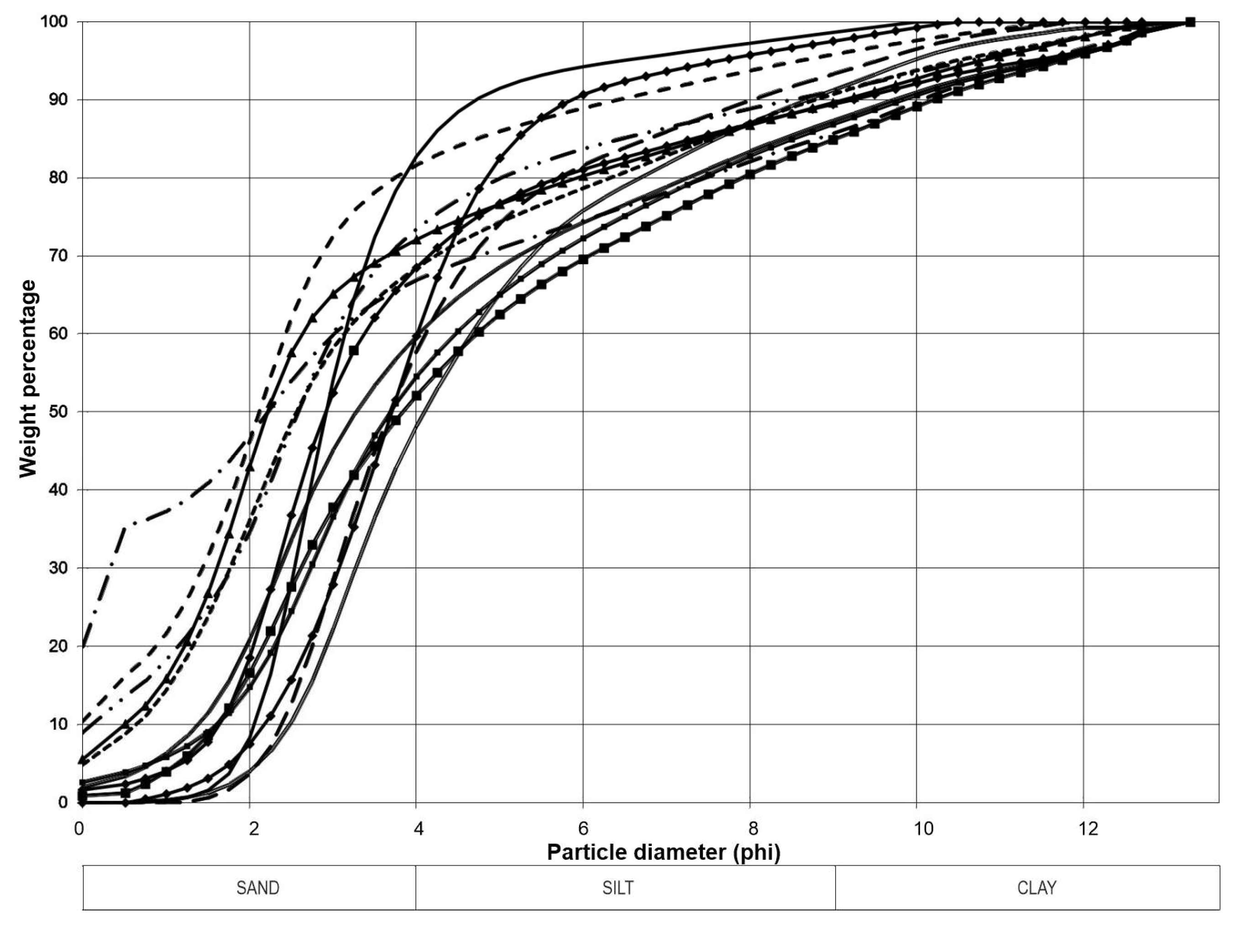

- G-A Family: includes the samples belonging to Group A in the triangular diagram of the global fraction (OL.5, OL.7a, OL.7b, OL.7 Ox, OL.Exterior 2), which exhibit curves with an initial segment dominated by fine gravel and very coarse to fine sand, accounting for approximately 80 to 90% of the sediment. This is followed by a flatter segment containing very fine sands, silts and clays, which together make up around 20% of the sediment (Figure 13). It corresponds to two types of deposits: on the one hand, clast-supported conglomerates with limited matrix, indicating high-energy environments with subsequent settling of the finer particles that make up the matrix (OL.5 and OL.Exterior 2); and on the other hand, debris flow deposits with a minimal matrix that include both fluvial-derived and autochthonous clasts.

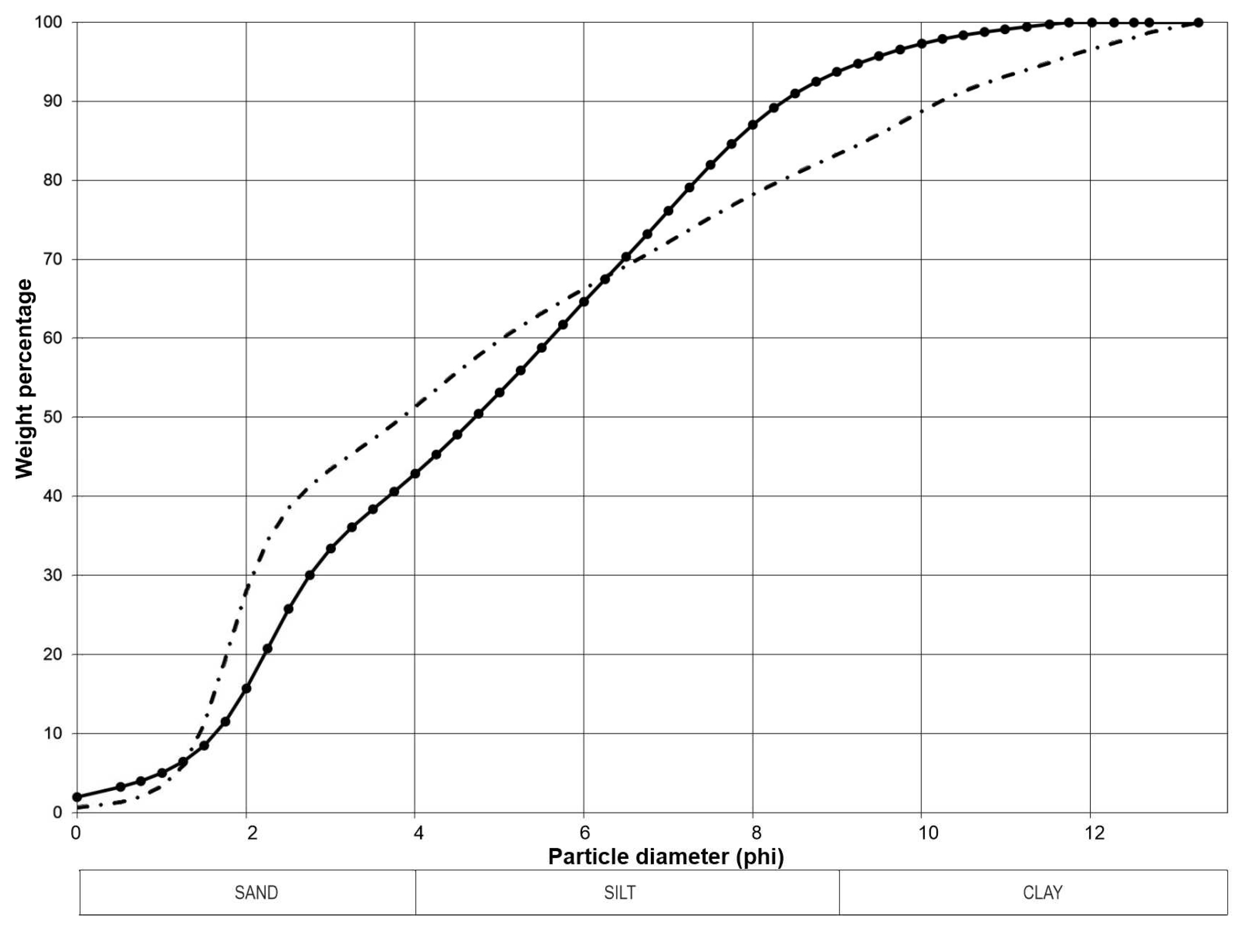

- G-B1 Family: it includes the samples OL.2a, OL.2b, OL.3, OL.4 and OL.4 gravas, which exhibit sigmoidal curves with three well-defined segments: an initial flat segment with varying presence of coarse and medium-grained sands, a steep middle segment with abundant fine sands and coarse silts; and a flat final segment with the remaining silts and clays (Figure 14). These curves indicate the presence of an essential population centered around fine sand and coarse silt, accompanied by silts, clays and varying amounts of coarse sands and gravels. They are indicative of a typically fluvial environment with high to medium energy, characterized by freight transport through reptation, saltation and suspension.

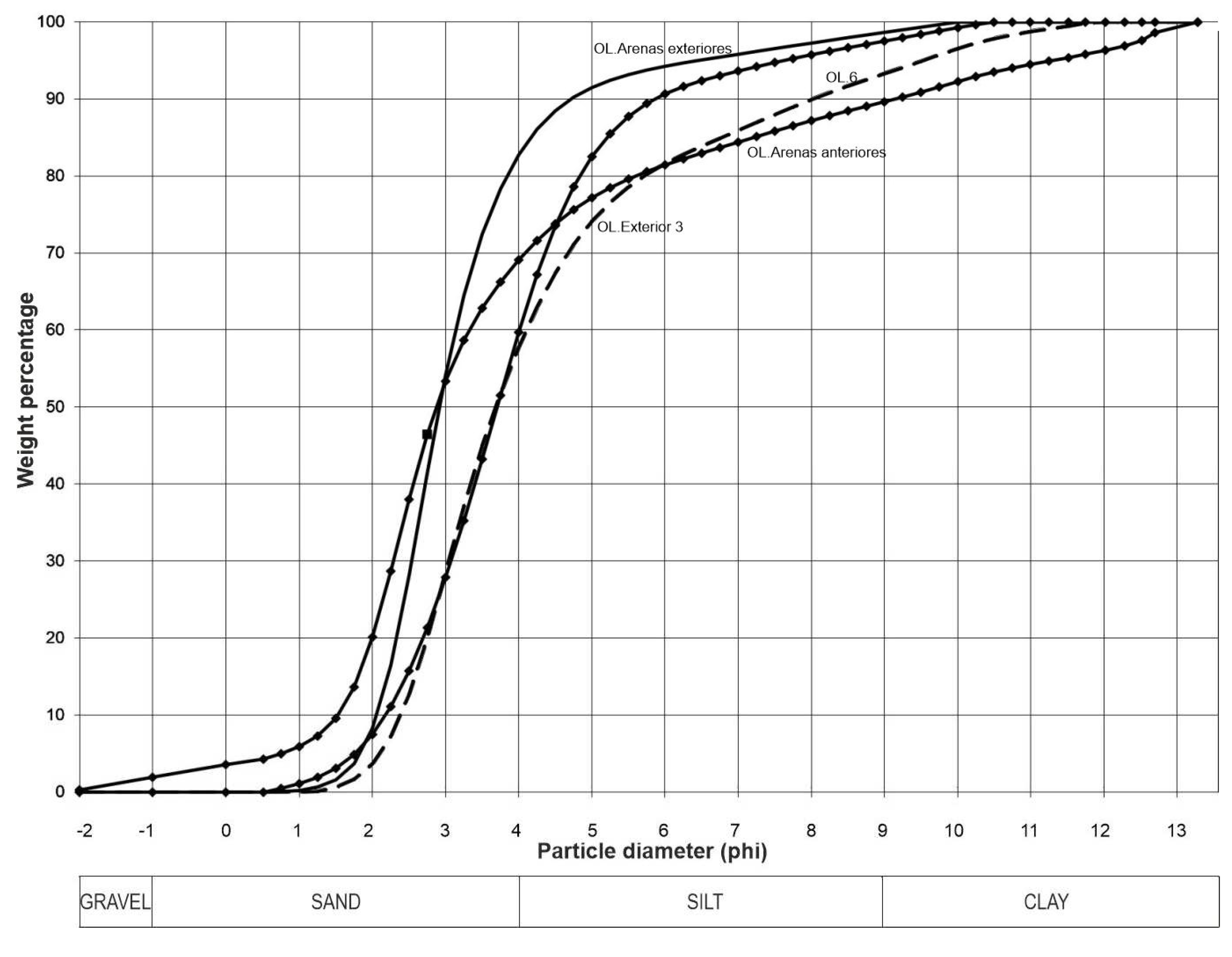

- G-B2 family: it includes samples OL.6, OL.Exterior 3, OL.Arenas Anteriores and OL.Arenas Exteriores, which exhibit curves with a strongly sigmoidal shape with three distinct sections. The first section is relatively flat and includes fine gravels and very coarse, coarse and medium sands. The second section is steep and rapidly ascending, ranging from fine sands to coarse silts. The third section is again relatively flat and consists of the remaining silts and clays, extending to clays (Figure 15). These sections indicate the presence of a dominant population, the central one composed of fine sands and very coarse silts, transported by saltation and suspension. These curves are typical of high-energy fluvial environments with a high sorting capacity.

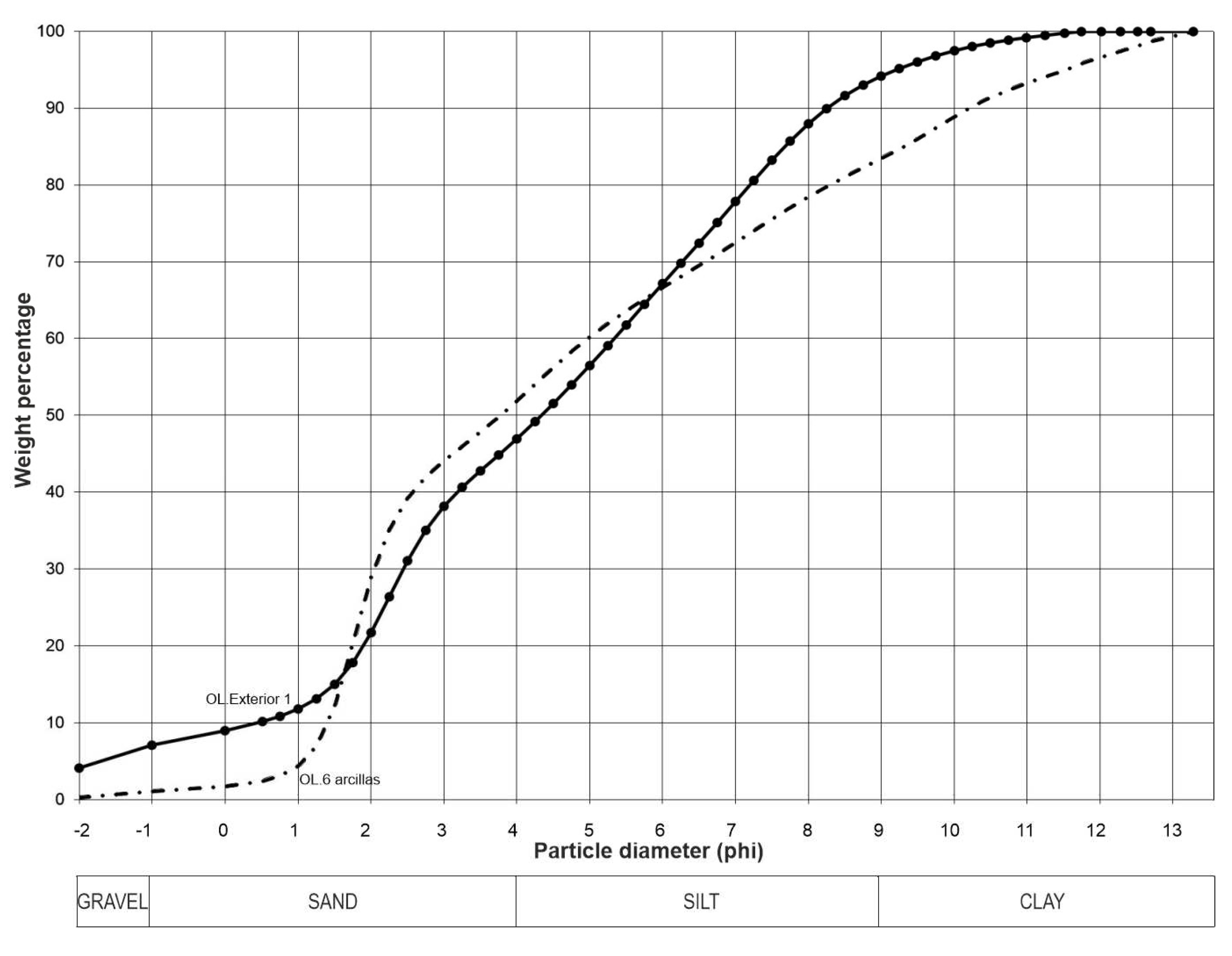

- G-B3 family: it includes the samples OL.Exterior 1 and OL.6 arcillas, which exhibit slightly sigmoidal curves. The first section is relatively flat and includes fine gravel and very coarse sand. The second section is steep and corresponds to an increase in the remaining sands until reaching 50% of the sample. The final section represents the remaining portion of the sample, consisting of silt and clay (Figure 16). This corresponds to fluvial sedimentation where significant settling follows the initial bedload deposition.

- F-1 family: it includes the curves of the samples from G-A, G-B1 and G-B2 (Figure 17).

- F-2 family: it is identical to the G-B3 family of the coarse fraction (OL.6 arcillas, OL.Exterior.1) (Figure 18).

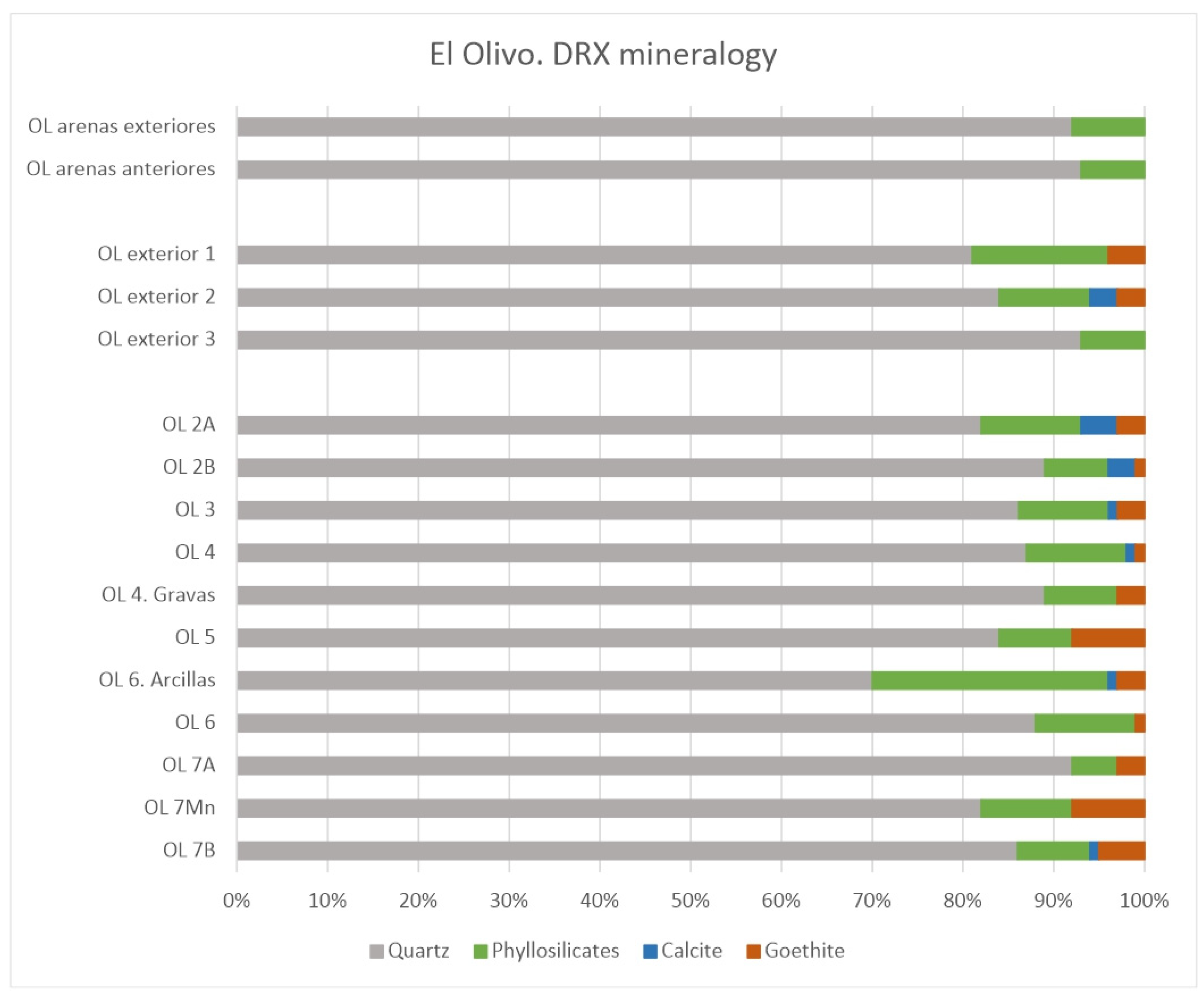

4.2.2. Mineralogy

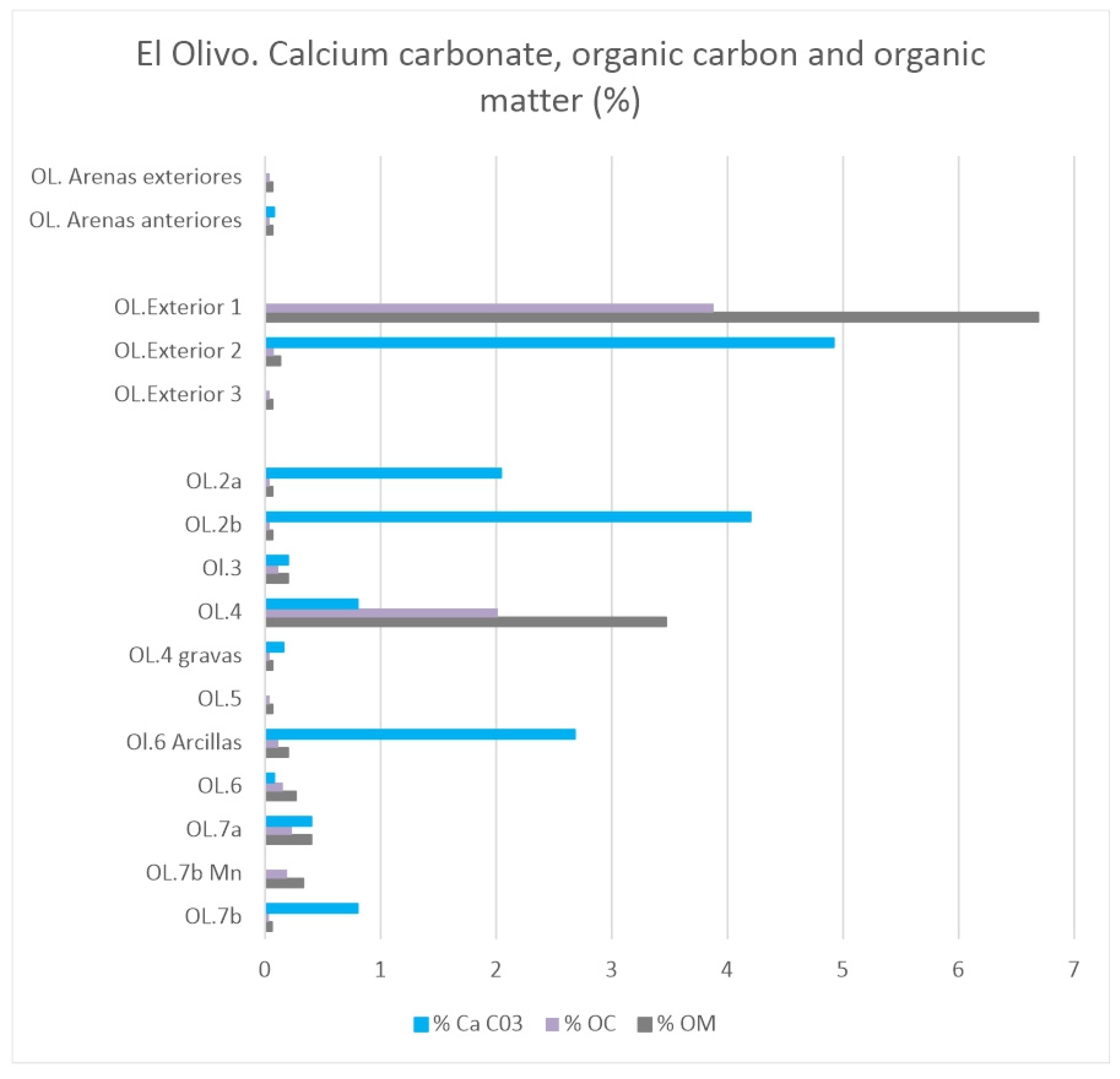

4.2.3. Calcium carbonate, organic charcoal and organic matter

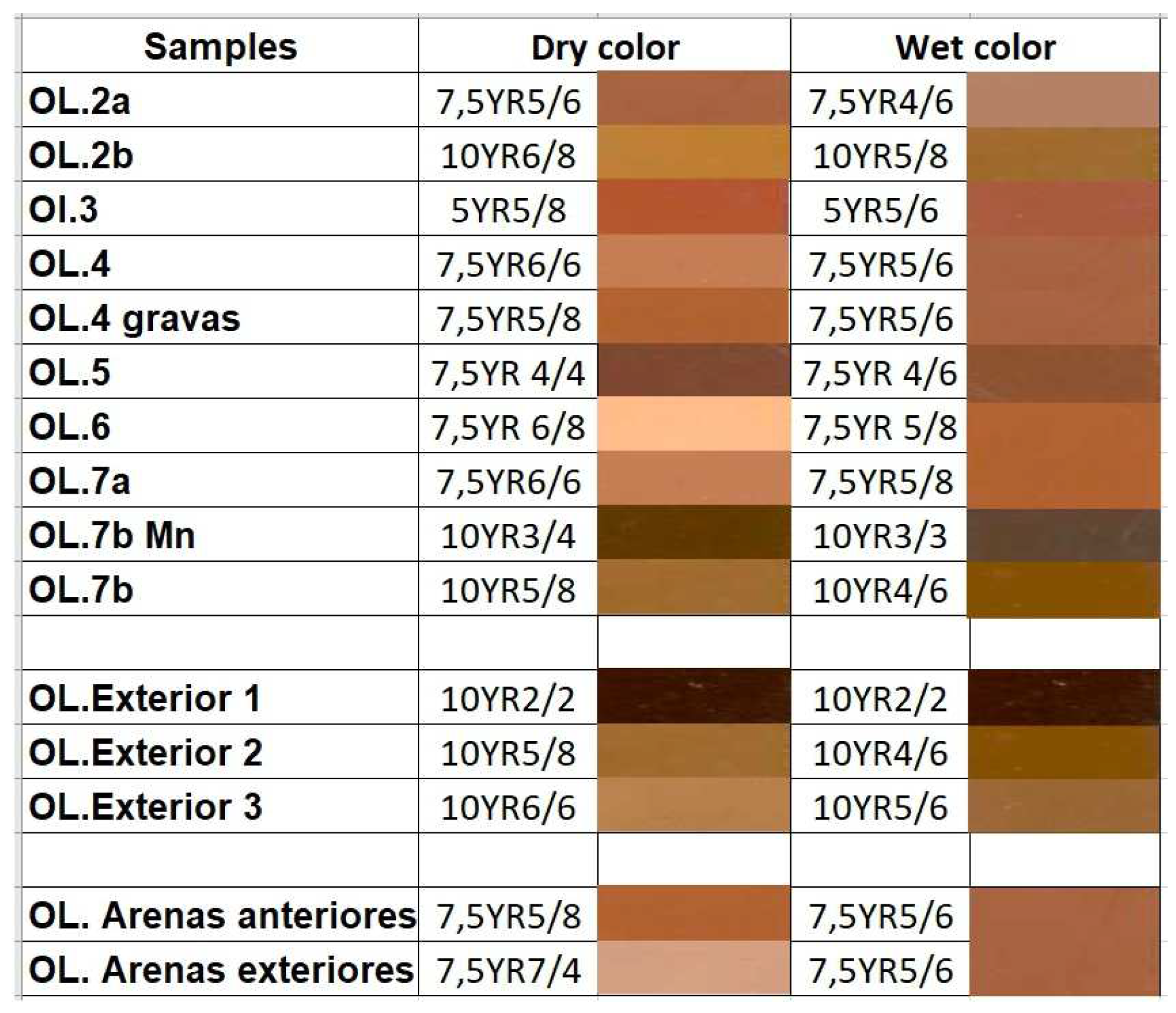

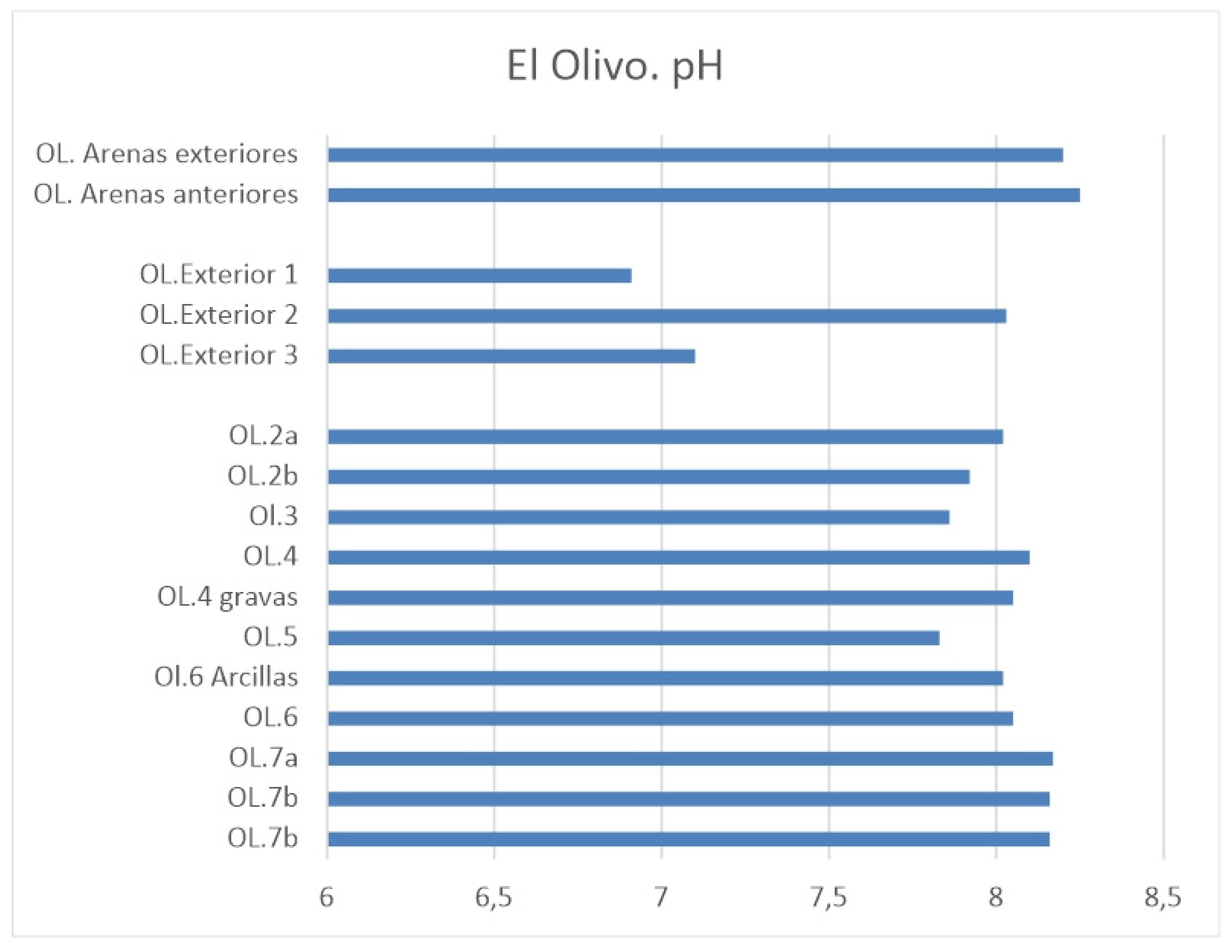

4.2.4. Color and pH

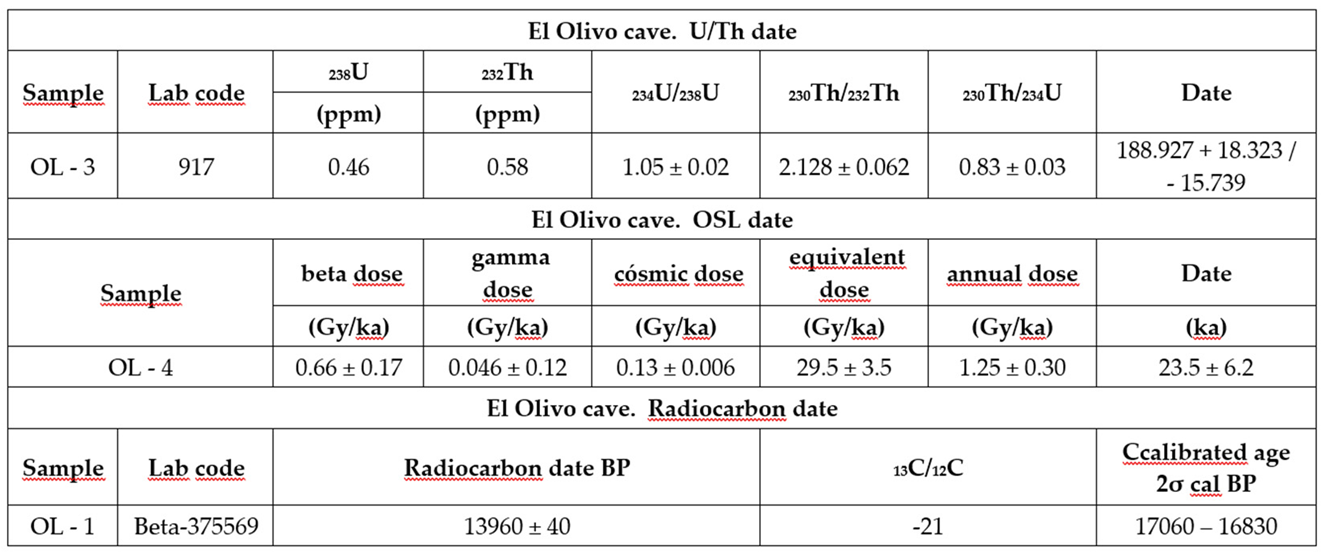

5. Geochronology

6. Geomorphological and geoarchaeological interpretation

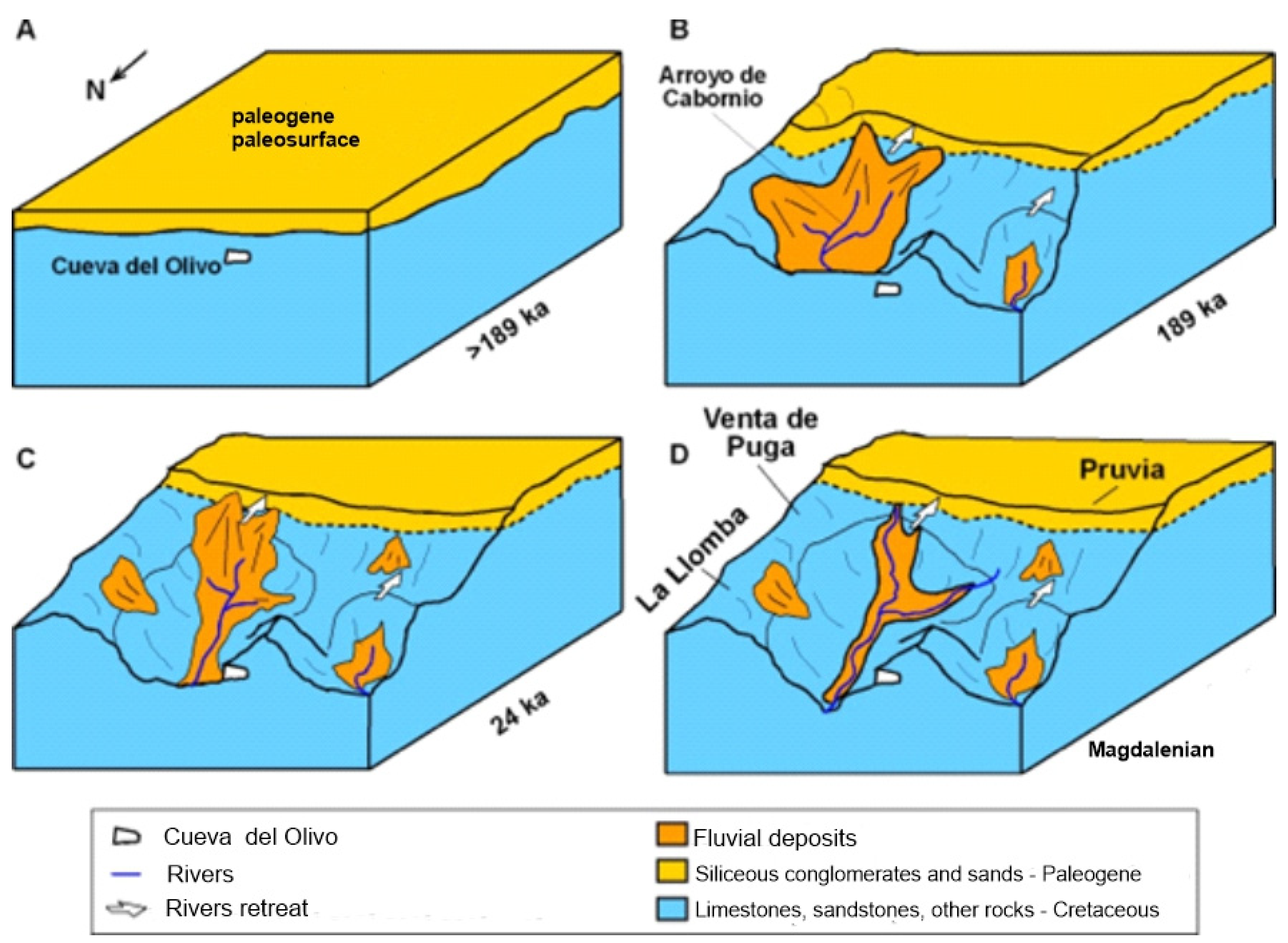

6.1. Paleogeographic evolution of El Olivo cave

- The first phase began with the formation of El Olivo Cave within Cretaceous bedrock covered by Paleogene detrital rocks, which formed the Llanera plain (Figure 22A). The cave conduit originated when the water table was located 147 m above the present sea level. Therefore, Phase 1 took place a long time before the precipitation of the flowstone OL-03 at 189 ± 17 ka.

- Phase 2 comprised the entrenchment of the Aboño river network on the Llanera plain in the vicinity of El Olivo Cave (Figure 22B). The headwaters migrated southwards eroding the Llanera plain. The fluvial incision also caused the lowering of the water table and the vadose development of the cave. Finally, the cave was partially filled by detrital sediments and flowstones precipitated at 189 ± 17 ka, coeval with the limit between OIS 7-6. These detrital and speleothem deposits remain perched on the cave walls. The cave infill would be related to the erosion of the Paleogene rocks (Figure 22B) and coincides with a sedimentary aggradation event in karst caves along the Cantabrian Region during OIS 7-6 [38,39].

- Fluvial incision, the drop of the water table and the erosion of the Llanera plain continued during Phase 3 (Figure 22C). At the same time, the cave sedimentary infill was partially removed before or after the interception of the cave by the topographic surface. This led to the creation of the cave entrance, which allowed the potential entrance of fauna and humans, as shown by the probable presence of Neanderthal groups in the cave.

- Phase 4 corresponds to the deposition of sandstone and quartzite pebbles and quartz sand transported by the Cabornio stream from Llanera plain to El Olivo cave (Figure 22D). This implies the location of the Cabornio stream channel at the position of the cave. The alluvial deposition within the cave occurred around 24 ± 6 ka and would be related to alluvial fans developed under the dry and cold conditions of OIS-2

- Fluvial incision continued during Phase 5 (Figure 22E) and humans frequented El Olivo cave at the end of OIS-2 according to Álvarez-Alonso et alii (2018) [4]. Simultaneously, the stream flooded the cave leading to sandy-loamy sediment with reworked archaeological remains during the OIS-2. Cabornio stream has descended 13 m from 24 ka to the present, representing an incision rate of 0.54 mm·a-1.

6.2. Geoarchaeological interpretation

6. Conclusions

| 1 | We use the expression “years old” because, in the case of OSL dating, is not appropriate to use the term “BP”, which should be restricted to radiocarbon dates, as recently was pointed out [36]. |

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Álvarez-Alonso, D. El Paleolítico en la cuenca del río Aboño (Llanera). Excavaciones en los yacimientos de El Barandiallu y la cueva del Olivo. Excavaciones Arqueológicas en Asturias 2007-2012; Consejería de Cultura, Principado de Asturias: Oviedo, Spain, 2013; Volume 7, pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Alonso, D. La cueva del Olivo (Llanera). Un nuevo yacimiento magdaleniense en el centro de Asturias. Nailos: estudios interdisciplinares de arqueología 2014, 1, 181–192. Available online: https://nailos.org/index.php/nailos/article/view/62/69.

- Álvarez-Alonso, D.; de Andrés Herrero, M.; Álvarez Fernández, E.; García-Ibaibarriaga, N.; Jordá Pardo, J.F.; Rojo, J. Los ‘campamentos secundarios’ en el Magdaleniense cantábrico: resultados preliminares de la excavación en la cueva del Olivo (Llanera, Asturias). In Cien Años de arte rupestre paleolítico. Centenario del descubrimiento de la cueva de la Peña de Candamo (1914-2014); Corchón, Mª. S., Menéndez Fernández, M., Eds.; Acta salmanticensia. Estudios históricos y geográficos; Universidad de Slamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2014; Volume 106, pp. 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Alonso, D.; Álvarez- Fernández, E.; Andrés Herrero, M. de; Ballesteros, D.; Domínguez, M.; García-Ibaibarriaga, N.; Jordá-Pardo, J.F.; Yravedra, J. Excavaciones en el yacimiento paleolítico de la cueva del Olivo (Pruvia, Llanera): campañas 2013-2016. Excavaciones Arqueológicas en Asturias 2013-2016; Consejería de Cultura, Principado de Asturias: Oviedo, Spain, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Alonso, D.; Andrés Herrero, M. de; Hevia Carrillo, A.; Mielgo Villalpando, C.; Yravedra, J. La cueva del Olivo (Pruvia, Llanera). Campaña de 2017. Excavaciones Arqueológicas en Asturias 2017-2020. Consejería de Cultura, Principado de Asturias: Oviedo, Spain, 2022; Volume 8, pp. 89–92.

- Álvarez-Alonso, D.; Rodríguez Asensio, J.A.; Jordá Pardo, J.F. Reflexiones en torno a la caracterización tecnotipológica del yacimiento de Bañugues (Asturias, España) en el marco del Paleolítico medio del norte de la Península Ibérica. Munibe 2014, 65, 5–24. Available online: https://www.aranzadi.eus/fileadmin/docs/Munibe/2014005024AA.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Alonso, D.; Jordá Pardo, J.F.; Carral, P.; Flor Blanco, G.; Flor, G.; Iriarte-Chiapusso, Mª.J.; Kehl, M.; Klasen, N.; Maestro, A.; Rodríguez Asensio, J.A.; Weniger, G.-Ch. At the edge of the Cantabrian sea. New data on the Pleistocene and Holocene site of Bañugues (Gozón, Asturias, Spain): Palaeogeography, geoarchaeology and geochronology. Quaternary International 2020, 566–567, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada García, R.; Jordá Pardo, J.F. Arqueología y gas natural: el Paleolítico medio de El Barandiallu (Villabona, Llanera, Asturias central). Península Ibérica. In XI Reunión Nacional de Cuaternario, Oviedo (Asturias), 2 - 3 y 4 de julio 2003; AEQUA and Universidad de Oviedo, Oviedo, 2003; 253-260.

- Álvarez Alonso, D. Las cadenas operativas líticas de El Barandiallu (Asturias, norte de Iberia): adaptación y variabilidad tecnológica en el contexto del Musteriense cantábrico. Munibe 2017, 68, 49–72. Available online: https://www.aranzadi.eus/fileadmin/docs/Munibe/maa.2017.68.11.pdf.

- Merino-Tomé, O.; Suárez Rodríguez, A.; Alonso, J.; González Menéndez, L.; Heredia, N.; Marcos, A. Mapa Geológico Digital continuo E. 1:50.000, Principado de Asturias (Zonas: 1100-1000-1600); Navas, J., Ed.; GEODE. Mapa Geológico Digital continuo de España; SIGECO-IGME: Madrid, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer, M.B. Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W.R.; Johnson, D.L. A survey of disturbance processes in archaeological site formation. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 1; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1978; pp. 315–381. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, D.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.; Giralt, S.; García-Sansegundo, J.; Meléndez-Asensio, M. A multi-method approach for speleogenetic research on alpine karst caves. Torca La Texa shaft, Picos de Europa (Spain). Geomorphology 2015, 247, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeb, B. An all-in-one electronic cave surveying device. Cave Radio and Electronics Group Journal 2009, 72, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, L. Computer Modelling of Cave Passages. Compass & Tape 2001, 15, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Blott, S.J.; Pye, K. GRADISTAT: A grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 2001, 26, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blott, S.J. GRADISTAT Version 8.0. In A Grain Size Distribution and Statistics Package for the Analysis of Unconsolidated Sediments by Sieving or Laser Granulometer; Kenneth Pye Associates Ltd., Crowthorne Enterprise Centre, Old Wokingham Road: Crowthorne, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Udden, J.A. Mechanical composition of clastic sediments. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 1914, 25, 655–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C.K. A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. Journal of Geology 1922, 30, 377–392. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.1086/622910. [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.H. Quantitative interpretation of X-Ray diffraction patterns. III. Simultaneous determination of a set of reference intensities. Journal of Applied Crystallography 1975, 8, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsell, A.H. A color notation: an illustrated system defining all colors and their relations by measured scales for Hue, Value and Chroma. 14th ed.; Munsell Color, Baltimore, USA, 1981.

- Thomas, G.W. Soil pH and soil acidity. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3 - Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, USA, 1996; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, J.L.; Julià, R.; Mora, R. Uranium-series dating of the Mousterian occupation at at Abric Romaní, Spain. Nature 1988, 332, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, N.A. , Electrodeposition of actinides for alpha spectrometric determination. Analytical Chemistry 1972, 44, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallstadius, L. A method for the electrodeposition of actinides. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. 1984, 223, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovich, M.; Harmon, R.S. Uranium-Series Disequilibrium: Applications to Earth, Marine, and Environmental Sciences; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; 910 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbauer, R.J. UDATE1: a computer program for the calculation of Uranium- series isotopic ages. Comput. Geosci. 1991, 17, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.S.; Wintle, A.G. The single aliquot regenerative dose protocol: potential for improvements in reliability. Radiation Measurements 2003, 37, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.S.; Wintle, A.G. Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerative-dose protocol. Radiation Measurements 2000, 32, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, R.; Roberts, R.; Laslett, G.; Yoshida, H.; Olley, J. Optical dating of single and multiple grains of quartz from Jinmium Rock Shelter, Northern Australia: Part I. Experimental design and statistical models. Archaeometry 1999, 41, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.J. Beta doses to spherical grains. Radiation Measurements 2003, 37, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.R.; Hutton, J.T. Cosmic ray contributions to dose rates for luminescence and ESR dating: large depths and long term variations. Radiation Measurements 1994, 23, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, G.; Mercier, N.; Adamiec, G. Dose-rate conversion factors: update. Ancient TL 2011, 29, 5–8. Available online: http://ancienttl.org/ATL_29-1_2011/ATL_29-1_Guerin_p5-8.pdf.

- Reimer, P.J.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Beck, C.W.; Blackwell, G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Buck, C.E.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; Grootes, P.M.; Guilderson, T.P.; Haflidason, H.; Hajdas, I.; Hatté, C.; Heaton, T.J.; Hoffmann, D.L.; Hogg, A.G.; Hughen, K.A.; Kaiser, K.F.; Kromer, B.; Manning, S.; Niu, M.; Reimer, R.W.; Richards, D.A.; Marian Scott, E.; Southon, J.R.; Staff, R.A.; Turney, C.S.M.; Van der Plicht, J. INTCAL13 and Marine 13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BC. Radiocarbon 2013, 55, 1869–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; Grootes, P.M.; Guilderson, T.P.; Hajdas, I.; Heaton, T.J.; Hogg, A.G.; Hughen, K.A.; Kromer, B.; Manning, S.W.; Muscheler, R.; Palmer, J.G.; Pearson, C.; van der Plicht, J.; Reimer, R.W.; Richards, D.A.; Scott, E.M.; Southon, J.R.; Turney, C.S.M.; Wacker, L.; Adolphi, F.; Büntgen, U.; Capano, M.; Fahrni, S.M.; Fogtmann-Schulz, A.; Friedrich, R.; Köhler, P.; Kudsk, S.; Miyake, F.; Olsen, J.; Reinig, F.; Sakamoto, M.; Sookdeo, A.; Talamo, S. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55 cal k BP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.G. Métodos de datación en el Cuaternario: La Cartografía del Cuaternario en España y la controversia del concepto “Datación Absoluta”. Cuaternario y Geomorfología 2022, 36, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jordá Pardo, J.F.; Carral González, P. Estudio litoestratigráfico, sedimentológico y edafológico del registro del Pleistoceno superior de la cueva de Coímbre (zona B) (Asturias, España). In La cueva de Coímbre (Peñamellera Alta, Asturias); Fundación Masaveu: Oviedo, 2017; pp. 170–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, D.; Giralt, S.; García-Sansegundo, J.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M. Quaternary Regional Evolution Based on Karst Cave Geomorphology in Picos de Europa (Atlantic Margin of the Iberian Peninsula). Geomorphology 2019, 336, 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriolabengoa, M.; Intxaurbe, I.; Medina Alcaide, M.A.; Rivero, O.; Rios Garaizar, J.; Líbano, I.; Bilbao, P.; Aranburu, A.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Gárate, D. L.; Gárate, D. From Cave Geomorphology to Palaeolithic Human Behaviour : Speleogenesis, Palaeoenvironmental Changes and Archaeological Insight in the Atxurra - Armiña Cave (Northern Iberian Peninsula). Journal of Quaternary Science 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, G.; Peón, A. Rasas y superficies de erosión continental en el relieve alpídico del noroeste peninsular y los depósitos terciarios. In Geomorfología do NW da Península Ibérica; Araújo, M.A., Gomes, A., Eds.; Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do PortoPorto, Portugal, 2004; pp. 13–31.

- Álvarez-Lao, D.J.; García, N. ; García, N. Chronological Distribution of Pleistocene Cold-Adapted Large Mammal Faunas in the Iberian Peninsula. Quaternary International 2010, 212, 120–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Llona, A.C.; Clark, G.; Karkanas, P.; Blackwell, B.; Skinner, A.R.; Andrews, P.; Reed, K.; Miller, A.; Macías-Rosado, R.; Vakiparta, J. The Sopeña Rockshelter, a New Site in Asturias (Spain) Bearing Evidence on the Middle and Early Upper Palaeolithic in Northern Iberia. Munibe Antropologia-Arkeologia 2012, 63, 45–79. Available online: https://www.aranzadi.eus/fileadmin/docs/Munibe/2012045079AA.pdf.

- Álvarez-Lao, D.J.; Ruiz-Zapata, M.B.; Gil-García, M.J.; Ballesteros, D.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M. ; Ruiz-Zapata, M.B.; Gil-García, M.J.; Ballesteros, D.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M. Palaeoenvironmental Research at Rexidora Cave: New Evidence of Cold and Dry Conditions in NW Iberia during MIS 3. Quaternary International 2015, 379, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).