Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

26 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Tributyltin

1.2. The Immune System

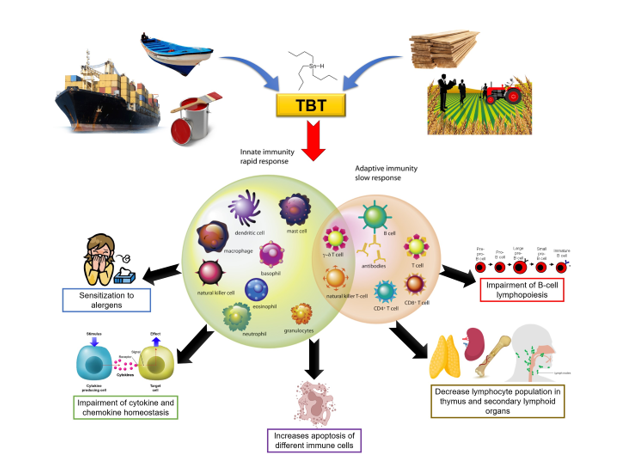

1.3. TBT and the Immune System

1.4. Tributyltin and Others Endocrine Disrupting-Chemicals

1.5. Current Gaps in Literature

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alcala, A.; Osborne, B.; Allen, B.; Seaton-Terry, A.; Kirkland, T.; Whalen, M. Toll-like receptors in the mechanism of tributyltin-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-6. Toxicology 2022, 472, 153177–153177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzieu, C. Environmental impact of TBT: the French experience. Sci. Total. Environ. 2000, 258, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antizar-Ladislao, B. Environmental levels, toxicity and human exposure to tributyltin (TBT)-contaminated marine environment. A review. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.H.; Wu, T.H.; Bolt, A.M.; Gerstenfeld, L.C.; Mann, K.K.; Schlezinger, J.J. From the Cover: Tributyltin Alters the Bone Marrow Microenvironment and Suppresses B Cell Development. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 158, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, F.; Mohanty, B. Thyroxine modulation of immune toxicity induced by mixture pesticides mancozeb and fipronil in mice. Life Sci. 2019, 240, 117078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, M.A.; Beg, A.; Zargar, U.R.; Sheikh, I.A.; Bajouh, O.S.; Abuzenadah, A.M.; Rehan, M. Organotin Antifouling Compounds and Sex-Steroid Nuclear Receptor Perturbation: Some Structural Insights. Toxics 2022, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizário, J.E.; Brandão, W.; Rossato, C.; Peron, J.P. Thymic and Postthymic Regulation of Naïve CD4+T-Cell Lineage Fates in Humans and Mice Models. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, S.L.; Teague, J.E.; Sherr, D.H.; Schlezinger, J.J. An Endogenous Prostaglandin Enhances Environmental Phthalate-Induced Apoptosis in Bone Marrow B Cells: Activation of Distinct but Overlapping Pathways. Perspect. Surg. 2008, 181, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borish, L.C.; Steinke, J.W. 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, S460–S475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Boules, M.; Hamza, N.; Wang, X.; Whalen, M. Synthesis of interleukin 1 beta and interleukin 6 in human lymphocytes is stimulated by tributyltin. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 2573–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Wilburn, W.; Martin, T.; Whalen, M. Butyltin compounds alter secretion of interleukin 6 from human immune cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 38, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Whalen, M. Tributyltin alters secretion of interleukin 1 beta from human immune cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 35, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.-M. Organotin Compounds Act as Inhibitor of Transcriptional Activation with Human Estrogen Receptor. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 22, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, J.V.; Freitas-Lima, L.C.; Freitas, F.F.; Freitas, F.P.; Podratz, P.L.; Magnago, R.P.; Porto, M.L.; Meyrelles, S.S.; Vasquez, E.C.; Brandao, P.A.; et al. Tributyltin chloride induces renal dysfunction by inflammation and oxidative stress in female rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 260, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, L.; Gangemi, D.; Ancona, G.; Liboà, F.; Bendotti, G.; Minelli, L.; Chiovato, L. The cytokine storm and thyroid hormone changes in COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfi’, M.; Croera, C.; Ferrario, D.; Campi, V.; Bowe, G.; Pieters, R.; Gribaldo, L. TBTC induces adipocyte differentiation in human bone marrow long term culture. Toxicology 2008, 249, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfi’, M.; Bowe, G.; Pieters, R.; Gribaldo, L. Selective inhibition of B lymphocytes in TBTC-treated human bone marrow long-term culture. Toxicology 2010, 276, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caseri W. 2014. Initial Organotin Chemistry. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 751:20-24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Niu, Y.; Bian, X.; Zhang, Q. Tributyltin chloride-induced immunotoxicity and thymocyte apoptosis are related to abnormal Fas expression. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Heal. 2011, 214, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, G.M.; Perry, C.A.; Blachut, B.; Martin, N.; Bortner, C.D.; Sieber, S.; Li, J.-L.; Fessler, M.B.; Harry, G.J. Assessing the Association of Mitochondrial Function and Inflammasome Activation in Murine Macrophages Exposed to Select Mitotoxic Tri-Organotin Compounds. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2021, 129, 47015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, G. Effect of endocrine disruptor phytoestrogens on the immune system: Present and future. Acta Microbiol. et Immunol. Hung. 2018, 65, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, G. Immunoendocrinology: Faulty hormonal imprinting in the immune system. Acta Microbiol. et Immunol. Hung. 2014, 61, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.; Gilkeson, G. Estrogen Receptors in Immunity and Autoimmunity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 40, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies AG. 2004. Organotin Chemistry, 2nd Edition Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31023-4.

- De Santiago, A.; Aguilar-Santelises, M. Organotin compounds decrease in vitro survival, proliferation and differentiation of normal human B lymphocytes. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1999, 18, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Villar, M.; Hafler, D.A. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.L.; Podratz, P.L.; Sena, G.C.; Filho, V.S.D.; Lopes, P.F.I.; Gonçalves, W.L.S.; Alves, L.M.; Samoto, V.Y.; Takiya, C.M.; Miguel, E.d.C.; et al. Tributyltin Impairs the Coronary Vasodilation Induced by 17β-Estradiol in Isolated Rat Heart. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part A 2012, 75, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudimah, F.D.; Odman-Ghazi, S.O.; Hatcher, F.; Whalen, M.M. Effect of tributyltin (TBT) on ATP levels in human natural killer (NK) cells: Relationship to TBT-induced decreases in NK function. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2006, 27, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Che, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, C. Estrogen and estrogen receptor signaling promotes allergic immune responses: Effects on immune cells, cytokines, and inflammatory factors involved in allergy. Allergol. et Immunopathol. 2019, 47, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.-A.; Zhao, C.-S.; Jiang, S.-L.; Zhou, Y.-F.; Xu, D.-P. Toxic function of CD28 involving in the TLR/MyD88 signal pathway in the river pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus) after exposed to tributyltin chloride (TBT-Cl). Gene 2019, 688, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Jyotaki, M.; Kim, A.; Chai, J.; Simon, N.; Zhou, M.; Bachmanov, A.A.; Huang, L.; Wang, H. Regulation of bitter taste responses by tumor necrosis factor. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2015, 49, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouin, H.; Lebeuf, M.; Saint-Louis, R.; Hammill, M.; Pelletier. ; Fournier, M. Toxic effects of tributyltin and its metabolites on harbour seal (Phoca vitulina) immune cells in vitro. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008, 90, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Lamacchia, C.; Palmer, G. IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdiero, M.R.; Garlanda, C.; Jaillon, S.; Marone, G.; Mantovani, A. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in tumor progression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, P.E.; Bryan, G.W.; Pascoe, P.L.; Burt, G.R. The use of the dog-whelk, Nucella lapillus, as an indicator of tributyltin (TBT) contamination. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1987, 67, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Zuccarini, M.; Cichelli, A.; Khan, H.; Reale, M. Critical Review on the Presence of Phthalates in Food and Evidence of Their Biological Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, K.J.; Morin, S.M.; Kubosiak, A.; Ser-Dolansky, J.; Schalet, B.J.; Jerry, D.J.; Schneider, S.S. The use of patient-derived breast tissue explants to study macrophage polarization and the effects of environmental chemical exposure. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020, 98, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutcher, I.; Becher, B. APC-derived cytokines and T cell polarization in autoimmune inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, K.; Karius, V. Tributyltin release from harbour sediments—Modelling the influence of sedimentation, bio-irrigation and diffusion using data from Bremerhaven. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 980–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, S.I.; Apeti, D.A.; Mason, A.L.; Pait, A.S. An assessment of butyltins and metals in sediment cores from the St. Thomas East End Reserves, USVI. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, M.E.H.; Young, R.L.; Thompson, L.M.; Kore, P.; Crews, D.; A Hofmann, H.; Gore, A.C. EDCs Reorganize Brain-Behavior Phenotypic Relationships in Rats. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.-M.; Chang, Y.-C.; Lee, S.-S.; Yang, M.-L.; Kuan, Y.-H. Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators induced by Bisphenol A via ERK-NFκB and JAK1/2-STAT3 pathways in macrophages. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurt, K.; Hurd-Brown, T.; Whalen, M. Tributyltin and dibutyltin alter secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha from human natural killer cells and a mixture of T cells and natural killer cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012, 33, 503–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Yang, H. Tributyltin acetate-induced immunotoxicity is related to inhibition of T cell development in the mouse thymus. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2015, 11, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. 2005. International Marine Organization. Antifouling Systems. International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems on Ships. International Maritime Organization. London.

- Iwai, H.; Kurosawa, M.; Matsui, H.; Wada, O. Inhibitory Effects of Organotin Compounds on Histamine Release from Rat Serosal Mast Cells. Ind. Heal. 1992, 30, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Senthilkumar, K.; Loganathan, B.G.; Takahashi, S.; Odell, D.K.; Tanabe, S. Elevated Accumulation of Tributyltin and Its Breakdown Products in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) Found Stranded along the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 31, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Uchikawa, R.; Yamada, M.; Arizono, N.; Oikawa, S.; Kawanishi, S.; Nishio, A.; Nakase, H.; Kuribayashi, K. Environmental pollutant tributyltin promotes Th2 polarization and exacerbates airway inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Tada-Oikawa, S.; Takahashi, K.; Saito, K.; Wang, L.; Nishio, A.; Hakamada-Taguchi, R.; Kawanishi, S.; Kuribayashi, K. Endocrine disruptors that deplete glutathione levels in APC promote Th2 polarization in mice leading to the exacerbation of airway inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Tada-Oikawa, S.; Wang, L.; Murata, M.; Kuribayashi, K. Endocrine disruptors found in food contaminants enhance allergic sensitization through an oxidative stress that promotes the development of allergic airway inflammation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 273, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.S.; Piao, Y.J.; Moon, W.K. Bisphenol A Promotes the Invasive and Metastatic Potential of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ and Protumorigenic Polarization of Macrophages. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 170, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotrikla, A. Environmental management aspects for TBT antifouling wastes from the shipyards. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, S77–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyasu, S.; Moro, K. Role of Innate Lymphocytes in Infection and Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-H.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Kuo, H.-F.; Huang, M.-Y.; Yang, S.-N.; Chen, L.-C.; Huang, S.-K.; Hung, C.-H. Phthalates suppress type I interferon in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells via epigenetic regulation. Allergy 2013, 68, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-W.; Lee, J.-W.; Yoon, Y.D.; Kang, J.-S.; Moon, E.-Y. Bisphenol A and its substitutes regulate human B cell survival via Nrf2 expression. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, J.; Ling, L.; Yi, Y.; Tao, L.; Liao, X.; Gao, P.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Tributyltin triggers lipogenesis in macrophages via modifying PPARγ pathway. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 271, 116331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardone, P.J.; Guerrero, J.M.; Fernández-Santos, J.M.; Rubio, A.; Martín-Lacave, I.; Carrillo-Vico, A. Melatonin synthesized by T lymphocytes as a ligand of the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 51, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavastre, V.; Girard, D. TRIBUTYLTIN INDUCES HUMAN NEUTROPHIL APOPTOSIS AND SELECTIVE DEGRADATION OF CYTOSKELETAL PROTEINS BY CASPASES. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part A 2002, 65, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, S.; Reid, J.; Whalen, M. Secretion of interferon gamma from human immune cells is altered by exposure to tributyltin and dibutyltin. Environ. Toxicol. 2013, 30, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Pellom, S.T.; Shanker, A.; Whalen, M.M. Tributyltin exposure alters cytokine levels in mouse serum. J. Immunotoxicol. 2016, 13, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-W.; Park, S.; Han, H.-K.; Gye, M.C.; Moon, E.-Y. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate enhances melanoma tumor growth via differential effect on M1-and M2-polarized macrophages in mouse model. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Li, P. Effects of the tributyltin on the blood parameters, immune responses and thyroid hormone system in zebrafish. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 268, 115707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Wen, J.; Tao, L.; Zhao, M.; Ge, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Weng, D. RIP1 and RIP3 contribute to Tributyltin-induced toxicity in vitro and in vivo. Chemosphere 2018, 218, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, R.J. Environmental aspects of tributyltin. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1987, 1, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaisé, Y.; Lencina, C.; Cartier, C.; Olier, M.; Ménard, S.; Guzylack-Piriou, L. Bisphenol A, S or F mother’s dermal impregnation impairs offspring immune responses in a dose and sex-specific manner in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, E.; Podratz, P.L.; Sena, G.C.; de Araújo, J.F.P.; Lima, L.C.F.; Alves, I.S.S.; Gama-De-Souza, L.N.; Pelição, R.; Rodrigues, L.C.M.; Brandão, P.A.A.; et al. The Environmental Pollutant Tributyltin Chloride Disrupts the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis at Different Levels in Female Rats. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 2978–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.B.; Moll, T.; El-Kalay, M.; Kohne, C.; Hoo, W.S.; Encinas, J.; Carlo, D.J. Th1/Th2 cells in inflammatory disease states: therapeutic implications. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004, 4, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, S.; Takahashi, S.; Agusa, T.; Thomas, N.J.; Kannan, K.; Tanabe, S. Contamination status and accumulation profiles of organotins in sea otters (Enhydra lutris) found dead along the coasts of California, Washington, Alaska (USA), and Kamchatka (Russia). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 56, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Nishiyama, C. IL-10 in Mast Cell-Mediated Immune Responses: Anti-Inflammatory and Proinflammatory Roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K.; Tsunoda, M.; Konno, N. Tributyltin (TBT) increases TNFα mRNA expression and induces apoptosis in the murine macrophage cell line in vitro. Environ. Heal. Prev. Med. 2004, 9, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.; Jabłońska, E.; Ratajczak-Wrona, W. Immunomodulatory effects of synthetic endocrine disrupting chemicals on the development and functions of human immune cells. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Silva, A.; Dittz, D.; Santana, H.S.; Faria, R.A.; Freitas, K.M.; Coutinho, C.R.; Rodrigues, L.C.d.M.; Miranda-Alves, L.; Silva, I.V.; Graceli, J.B.; et al. The Pollutant Organotins Leads to Respiratory Disease by Inflammation: A Mini-Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtaki, K.; Aihara, M.; Takahashi, H.; Fujita, H.; Takahashi, K.; Funabashi, T.; Hirasawa, T.; Ikezawa, Z. Effects of tributyltin on the emotional behavior of C57BL/6 mice and the development of atopic dermatitis-like lesions in DS-Nh mice. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2007, 47, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Arreola, M.I.; Moreno-Mendoza, N.A.; Nava-Castro, K.E.; Segovia-Mendoza, M.; Perez-Torres, A.; Garay-Canales, C.A.; Morales-Montor, J. The Endocrine Disruptor Compound Bisphenol-A (BPA) Regulates the Intra-Tumoral Immune Microenvironment and Increases Lung Metastasis in an Experimental Model of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penninks, A.H. The evaluation of data-derived safety factors for bis(tri-n-butyltin)oxide. Food Addit. Contam. 1993, 10, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phiel, K.L.; Henderson, R.A.; Adelman, S.J.; Elloso, M.M. Differential estrogen receptor gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell populations. Immunol. Lett. 2005, 97, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Regalado, M.D.; Pérez-Sánchez, G.; Rojas-Espinosa, O.; Arce-Paredes, P.; Girón-Peréz, M.I.; Pavón-Romero, L.; Becerril-Villanueva, E. NeuroImmunoEndocrinology: A brief historic narrative. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 112, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendiran, A.; Tenbrock, K. Regulatory T cell function in autoimmune disease. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2021, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribot, J.C.; Lopes, N.; Silva-Santos, B. γδ T cells in tissue physiology and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 21, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger J, Falk HF, Bucher F, Orthuber G, Hoffmann R, Negele RD. 1994. Prolonged exposure of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to sublethal concentrations of bis(tri-n-butyltin) oxide: effects on leukocytes, lymphatic tissues and phagocytosis activity. In: Muller R, Lloyd R (eds) Sublethal and chronic effects of pollutants on freshwater fish. Blackwell Scientific, Cambridge, MA, pp 113.

- Sakazaki, H.; Ueno, H.; Nakamuro, K. Estrogen receptor α in mouse splenic lymphocytes: possible involvement in immunity. Toxicol. Lett. 2002, 133, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlezinger, J.J.; Howard, G.J.; Hurst, C.H.; Emberley, J.K.; Waxman, D.J.; Webster, T.; Sherr, D.H. Environmental and Endogenous Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Agonists Induce Bone Marrow B Cell Growth Arrest and Apoptosis: Interactions between Mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, 9-cis-Retinoic Acid, and 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2. PEDIATRICS 2004, 173, 3165–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, M.E.H.; Young, R.L.; Thompson, L.M.; Kore, P.; Crews, D.; A Hofmann, H.; Gore, A.C. EDCs Reorganize Brain-Behavior Phenotypic Relationships in Rats. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibi, T.; Balog, H.; Alghazeer, R.; Othman, M.; Benjama, A.; Elhensheri, M.; Lwaleed, B.; Griw, M. Exposure to low-dose bisphenol A induces spleen damage in a murine model: Potentially through oxidative stress? Open Veter- J. 2022, 12, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Kumar, A. Mechanism of immunotoxicological effects of tributyltin chloride on murine thymocytes. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2014, 30, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.M.; Merien, F.; Braakhuis, A.; Dulson, D. T-cells and their cytokine production: The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of strenuous exercise. Cytokine 2018, 104, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimasaki, Y.; Kitano, T.; Oshima, Y.; Inoue, S.; Imada, N.; Honjo, T. Tributyltin causes masculinization in fish. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortman, K.; Liu, Y.-J. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švajger, U.; Dolenc, M.S.; Jeras, M. In vitro impact of bisphenols BPA, BPF, BPAF and 17β-estradiol (E2) on human monocyte-derived dendritic cell generation, maturation and function. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 34, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada-Oikawa, S.; Murata, M.; Kato, T. Preferential Induction of Apoptosis in Regulatory T Cells by Tributyltin: Possible Involvement in the Exacerbation of Allergic Diseases. Nippon. Eiseigaku Zasshi (Japanese J. Hyg. 2010, 65, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Tanabe, S.; Takeuchi, I.; Miyazaki, N. Distribution and Specific Bioaccumulation of Butyltin Compounds in a Marine Ecosystem. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe S, Prudente M, Mizuno T, Hasegawa J, Iwata H, Miyazaki N. 1998. Butyltin contamination in marine mammals from North Pacific and Asian Coastal waters. Environ Sci Tech. 32:193–8. [CrossRef]

- Titley-O'Neal, C.P.; Munkittrick, K.R.; MacDonald, B.A. The effects of organotin on female gastropods. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 2360–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.D.; Shah, H.; A Green, S.; Bankhurst, A.D.; Whalen, M.M. Tributyltin exposure causes decreased granzyme B and perforin levels in human natural killer cells. Toxicology 2004, 200, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontana, F.; Battisti, S.; Napoli, N.; Strollo, R. Immuno-Endocrinology of COVID-19: The Key Role of Sex Hormones. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 726696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-K.; Cheng, H.-H.; Hsu, T.-Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Hung, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Lai, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-J.; Huang, H.-C.; Chan, J.Y.H.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Di-Ethyl Phthalate (DEP) Is Related to Increasing Neonatal IgE Levels and the Altering of the Immune Polarization of Helper-T Cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uc-Peraza, R.G.; Castro. B.; Fillmann, G. An absurd scenario in 2021: Banned TBT-based antifouling products still available on the market. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 805, 150377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yebra, D.M.; Kiil, S.; Dam-Johansen, K. Antifouling technology—past, present and future steps towards efficient and environmentally friendly antifouling coatings. Prog. Org. Coatings 2004, 50, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pan, W.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhu, D.; Lu, Y.; Feng, X.; Yang, X.; Dittmer, U.; Lu, M.; et al. Hepatitis B Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cells Maintain Functional Exhaustion after Antigen Reexposure in an Acute Activation Immune Environment. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernersson, S.; Pejler, G. Mast cell secretory granules: armed for battle. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO-IPCS. 1999a. World Health Organization. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Concise international chemical assessment document 14. Tributyltin oxide. http://www.inchem.org/documents/cicads/cicad14.htm.

- Yanagisawa, R.; Koike, E.; Win-Shwe, T.-T.; Takano, H. Effects of Oral Exposure to Low-Dose Bisphenol S on Allergic Asthma in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, K.; Ohno, S.; Nakajima, Y.; Toyoshima, S.; Nakajin, S. Effects of Various Chemicals Including Endocrine Disruptors and Analogs on the Secretion of Th1 and Th2 Cytokines from Anti CD3-Stimulated Mouse Spleen Cells. J. Heal. Sci. 2003, 49, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Zaragoza, J.F.; Romo-Martínez, E.J.; Durán-Avelar, M.d.J.; García-Magallanes, N.; Vibanco-Pérez, N. Th17 Cells in Autoimmune and Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayas, J.P.; Mamede, J.I. HIV Infection and Spread between Th17 Cells. Viruses 2022, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Chen, S.; Wu, T.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C. Tributyltin causes obesity and hepatic steatosis in male mice. Environ. Toxicol. 2011, 26, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-N.; Zhang, J.-L.; Ren, H.-T.; Zhou, B.-H.; Wu, Q.-J.; Sun, P. Effect of tributyltin on antioxidant ability and immune responses of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 138, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.-S.; Fang, D.-A.; Xu, D.-P. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) respond to tributyltin chloride (TBT-Cl) exposure in the river pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus): Evidences for its toxic injury function. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2020, 99, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cytokine/Chemokine | Experimental Model | Effect of TBT |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Human/in vitro - zebrafish |

|

| IL-2 | BALB/c |

|

| IL-4 | C57BL/6 & CBA/J mice spleen cells |

|

| IL-5 | C57BL/6 |

|

| IL-6 | Human/in vitro - zebrafish |

|

| IL-7 | ICR mice |

|

| IL-10 | C57BL/6 |

|

| IL-12 | C57BL/6 |

|

| IL-13 | BALB/c |

|

| IFN-γ | BALB/c, CBA/J mice spleen cells & Human/in vitro |

|

| TNF-α | BALB/c/J774.1 cell line & Human/in vitro - zebrafish |

|

| MIP-1β | BALB/c |

|

| RANTES | BALB/c |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).