1. Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in the modern scenario is viewed commonly as a catastrophic agent posing a greater risk predominantly among the young and the elderly populations. It has been unanimously given the title of a cold killer by families across the globe and is one of the major causes of a large fraction of mother’s lamenting over the death of their children. The virus being a respiratory pathogen has recorded to date the highest rank amongst other respiratory pathogens when it comes to the morbidity and mortality rates. The global RSV rates of infection beam up to a huge number of 64 million cases / year. The virus is ubiquitous and highly predominant even among hospital environments pertaining to which neonates get attacked in their early days itself and nearly every child before celebrating their 2nd birthday get infected at least once; 70 % being infected well before they even walk. RSV is the leading cause of severe pediatric bronchiolitis and pneumonia (2 severe acute respiratory tract infections). RSV infection during the early months may lead to the predisposition to permanent breathing problems or even asthma exacerbations which is often seen to follow the reactive airway disease. RSV infections are generally prone to seasonal variability and geographical differences the temperate regions like Europe have their RSV epidemic wave during the cold winter months and in the tropical areas the hotter climates are more productive for RSV with an additional rippling effect during the rains. During an RSV epidemic, about 20- 40 % of the admitted infants and nearly 50% of the ward personnel may acquire the infection via nosocomial spread pointing to the highly contagious nature of the virus and its awestriking transmissibility index (average number of people who get infected from one infected person) of about 5-25. Further the normal procedures undertaken to prevent nosocomial infections meet with very limited success in the case of RSV thus if an RSV epidemic occurred it would double or even triple the additional costs. Another important property of the RSV is its ability to cause reinfections throughout suggesting incomplete/ partial immunity to the virus; up to 10% of the RSV infected infants being re-infected within several days after the 1° infection. RSV has its target of infecting the epithelial cells of the nasopharynx. The clinical presentation of RSV appears very similar to influenza virus. The initial symptoms occur after about 3-5 days and resemble that of a regular cold which is a repercussion of rhinitis and small-scale pharyngitis but mostly in babies and immunocompromised the LRT may be involved due to which progression to bronchiolitis (most common), bronchitis or tracheobronchitis / croup when bronchioles and bronchi are affected or pneumonia if alveoli get infected. It is transmitted via respiratory droplets (aerosols) when the infected person coughs, laughs or sneezes. The airborne droplets are taken by those who later get infected. Transmission through fomites is also very common. Infected people remain contagious for 3- 8 days but very young infants and children with weakened immunity can act as convalescent carriers. Infants recovering from RSV bronchiolitis continue to have respiratory symptoms which is termed post bronchiolitis wheeze, 50% of which continues for several years. Both innate and adaptive immune responses against RSV are seen; for neutrophils are quickly recruited and CD8+T cells have potent virus clearance activity, but the virus has evolved so many strategies to overcome the same. RSV is super susceptible to environmental changes involving temperature and humidity. A lot of risk factors are seen which include genetic factors, presence of comorbid diseases, premature births etc.

2. Medical Significance

CDC evaluation from 1979-1997 detected 200-500 child deaths to occur annually due to RSV associated illness alone. The pathogen causes mostly asymptomatic or subclinical infection in most of the population and in most people or a large fraction of highly nourished children, it just causes symptoms those of which resemble a common cold. The virus is, however, a serious enemy and poses quite a severe threat to small babies, immunocompromised children and old people. In the recent years, RSV has been increasingly associated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDC). The virus can cause a large spectrum of uncanny respiratory illness ranging from mild upper respiratory tract disturbances and rhinitis to severe lower respiratory tract infections such as trachaeobronchiolitis, polypnea, rales etc. RSV is a critical lifetaker in children aged 1- 15 months. Each year in the US, following the approach of RSV season, RSV leads to disastrous effects; in children less than 5 years of age, RSV causes about five hundred and seventy-five thousand hospitalizations and 2 million outpatient visits; and among adults over 65 years (senior citizens) about 1 lakh seventy-seven thousand hospitalisations, and nearly fourteen thousand deaths. The virus is highly capable of causing outbreaks and epidemics earning significant attention from the WHO whose statistics claim that about one third of the 12.2 million annual deaths in children under 5 years, occur due to RSV infections. A certain comparative study amongst native children below 4 years of age, conducted in the US recorded RSV to cause 137 deaths per year, whereas a significantly low number of 38 per year for the same age group was recorded for influenza patients thus making the RSV the second largest cause of mortality (after malaria). Although epidemics are reported only during a certain time, the virus may be present in local circulation always and usually before the onset of the epidemic season, certain bouts of small outbreaks may be reported by the endemic strains. However, the endemicity can’t be counted on because of the variations in the circulating strains, due to which severity of the RSV outbreaks can’t be predicted beforehand. About 25 to 40 out of 100 infants when exposed to RSV for a short time developed symptoms of pneumonia and bronchiolitis and the majority of those hospitalised are younger than 6 months old. Amongst pre – school children worldwide, approximately 60 – 65% of those diagnosed with lower respiratory tract infections have RSV infection. As per the US government within the completion of the first RSV season ; nearly 60% of infants will get infected. UK talks about RSV infection of 1-3% of the entire birth cohort (about 30,000 hospitalisations) and over 900- 1000 pediatric intensive care unit (PIC) admissions per annum. Birth during the April - September months just before the fall has been demonstrated as a potential risk factor in acquisition of RSV infection with a large risk of subsequent bronchiolitis. Such neonates who get infected shed RSV through their nasal secretion on to the bedsheets of the hospital wards. It may be noted that the virus survives on soft surfaces like those of the bedsheets for upto 30-35 minutes and on hard surfaces for upto 6 hours. Similarly during sudden outbreaks the old people who approach the hospitals with common cold like symptoms play a major role in the transmission of the agent to other patients admitted in the general wards. These RSV infected people are a major source of generating large aerosols which on account of their size fall on to the floor or similar surfaces which when adequately dried and swept will be airborne with a greater risk due to its minute size thus smaller resistance in passage through nostrils. Droplet nuclei of less than 0.1 micron when contains RSV is highly detrimental if inhaled. 40 % of those children who get infected for the first time with RSV show some kinds of lower respiratory involvement some of which later develops very serious complications that they have to be hospitalized.(Brandenburg , 2000). Nearly 7-21% of infants less than 1 year who get hospitalized require ventilation support (Brandenburg 2000). About 3000-4000 deaths occur annually in the US due to RSV acute viral bronchitis alone. There is a gradation given based on the severity of the disease. Those cases that require ICU admission and mechanical ventilation are given the highest priority levels. Young age is the most critical and significant contributing factor for RSV disease, with those infants below 4 months of age suffering the highest risk. Infants who are already afflicted with severe disorders like congenital heart disease or bronchopulmonary dysplasia when infected with RSV can lead to fatal outcomes. Further those infants who are weaned of breast milk, have acquired immunodeficiencies or preterm immature neonates (those with less than 280 days gestation) are the more prone ones with highest criticality bestowed upon the ones lacking even 225 days of gestation. It may be noted that rarely infected babies turn to be asymptomatic and die before even they turn 1 year old. In modern days to cope up with their busy work schedule its a general consternation for parents to wean their babies from breastfeeding. This is a critical factor that can lead to development of a weak immune system in the infants which is further ignited by the parents sending their children to daycares. Each healthy infant may pick the pathogen from the day care and carries the same to their homes from where the pathogen further flourishes; the next people contracting the infection being siblings and grandparents (if present) on account of their greater susceptibility, following which final transmission to the work environments are done by the parents. RSV enters the body through the eyes, nose or mouth. A child is bound to get infected if someone with RSV coughs or sneezes near him/ her. Virus transmission also occurs via shaking hands or sharing objects. Toys seem to be a potential fomite for toddlers that touch the toys after putting hands in their mouth. Lethargy, fever, otitis media, anorexia etc are key early symptoms for infants, whereas for older children the initial symptoms appear later and involve exclusively the upper respiratory tract (may later progress downward) but in severe cases of RSV attack (a higher infective dose), or weaker immunity, tracheobronchitis may appear quite early without any distinction between infants and older children. Infants suffer from an additional complication following RSV infection particularly those below 6 months of age. About 20 % have been seen suffering from apnea (breathing difficulty). It must be noted that apnea usually being an early event in RSV disease progression is an indicative that lower respiratory tract complications may follow (ensue immediately) and it can also be considered as a true sign that can be recognized as a case requiring hospitalization. RSV virus is a potential agent capable of causing epidemics. In the northern hemisphere with colder climates November – January is booked by RSV and in tropical climates RSV waits till hotter climates with a greater manifold strike during the rains. (Garcia et al 2010; Houben et al, 2011). Certain other reports also suggest viral outbreaks to occur during late fall and early winter to the late spring for a period of 3- 4 months. RSV has 2 subgroups A and B (Sato et al, 2005); during epidemics either of these predominate. Group A is known to cause much serious infections. The RSV virus first chooses the upper respiratory tract / nasopharynx to replicate (Brandenburg 2001; Collins & Graham, 2005). However, in the babies the virus further goes down easily for it is a well-known fact that babies often keep aspirating the saliva; also, the ciliary action which is not that potent allows the virus to transverse the same. The virus can establish itself in the lower respiratory tract provided only if has multiplied in the UTI. Incubation period is 4-5 days before the onset of the common initial symptoms like blockage of the nose, slight ear clogging, low grade fever (usually common within 4- 10 hours of nose blockage). If there’s sinus involvement pain near nose ocular junction is also seen (Brandenburg, 2000; Freymuth et al, 2001; Rietveld 2003). Early manifestations of RSV multiplication (in nasopharynx) include rhinitis (runny nose, difficulty in swallowing; sometimes sandpaper like feel in the throat, otitis media (one or both ears) which can’t be cleared by yawning. Later pharyngitis and deep mucosal involvement is also seen in the following days. But in many cases the disease is not limited by these and within 1- 3 days the infection progresses to lower respiratory tract thus resulting in mild to severe bronchitis, bronchiolitis, tracheobronchitis or croup. If the disease further progresses to affect the alveoli and extra bronchial tissues, it is likely to cause pneumonia. (Schwarze et al 2010). Tachypnea (rapid breathing greater than 20 breaths/ min), polypnea (increase in breathing frequency), rales (crepitations) dyspnea (discomfort in breathing) (Freymuth et Al 2001, Rietveld 2003) are other common symptoms of deep RSV invasion but are more common in kids.

Globally the Hajj pilgrimage (sacred tour to Mecca) to Saudi Arabia that occurs every year is a way by which the RSV causes outbreaks and even epidemics. Small children if present excessively in this population leads to increased chances of RSV infection. It should be noted that excessive crowding leads to larger concentrations of the virus within the atmosphere. Also, besides this common community halls and shared sleeping accommodations are known to highly favor this respiratory pathogen. During the pilgrimage season a large no of cases of acute respiratory tract infections are seen within the Saudi hospitals most of them when diagnosed point out to RSV as the sole cause. The virus puts forth a serious disease burden in the developing countries. For eg in India about 20-45% of children are hospitalized with RSV acute Respiratory infections. In such countries the rate of nosocomial spread of the pathogen is significantly very high due to overcrowding, shortage in the number of wards, low income etc. A higher degree of recurrent wheezing in childhood affecting nearly 55% (50 in developed countries) is seen among the hospitalized. It is highly notable that India, China, Nigeria, Pakistan and Indonesia account for over 16 million or nearly half of the global estimated cases of RSV induced fatal lung infections. Further in these countries simultaneous bacterial coinfections (2°) worsen the situation (Mc Intosh, 1991; Hall et al 1988; Ralston et al 2011).

A balance between the virus elimination and nature of immune response to the infection associates with the degree of pathogenesis given if both are oriented along the positive end the infection losing ground within no time and if not leading to greater duration in recovery (higher sustenance) or even additional complications. Pathogenesis occurs because of the multiplication of the viral agent as well as immune effector cell mediated cytotoxicity. The virus is highly known for its ability to induce syncytia formation (multinucleated giant cells) and it is also one of its cytopathological changes. Both the innate as well as the adaptive immune response are highly active during the RSV infection. In the general scenario, Macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells, Neutrophils, eosinophils, etc, of the innate arm play their role quite efficiently whereas from the adaptive side T cytotoxic cells and anti RSV neutralizing antibodies help to ward off the infection completely. Host effector cell population however can also be responsible for aggravating RSV pathogenesis provided the virus load is significantly high and it is highly capable of altering the cytokine responses via suitable mechanisms. This happens mostly in very young infants or children with severe underlying diseases/ those with weakened immunity. In such a case if the population of the cells like neutrophils remain significantly high for a long time near the virus multiplication site it is sure to damage other cells in the vicinity and cause necrosis and other pathological changes which may lead to mucus plug production and contribute to bronchiolitis. Similarly, if the eosinophils are aggravated via hike in eosinophil response inducing cytokine signals it may lead to the development of asthma. The immunological memory against a previous RSV infection is not likely to prevent subsequent RSV infections and the virus is highly capable of causing reinfections very soon because of the partial or incomplete immunity against the virus. RSV has a high rate of mutation with a rate of nucleotide substitution of about 0.0001 to 0.00001. The virus is highly known for its capability to orchestrate the processes of transcription and replication both carried out by the viral RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Progeny genomes after replication are known to engage in 2° transcription with high rates. Having discussed the criticality of RSV infections the WHO has endorsed the elimination of this deadly pathogen as one of its primary goals as there are currently no effective vaccines for RSV. The prophylactic measures currently available are quite costly and it involves a monoclonal antibody directed against F glycoprotein (an envelope glycoprotein) called palvizumab (=synagis) [ and its derivative motvizumab] but its use is restricted to high-risk subjects suffering from other severe diseases. It is quite potent because it can decrease the hospitalisation rates as well as speed up discharges. Apart from this a broad-spectrum antiviral agent namely ribavirin is in use but its not effective.

3. Virology

Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus (= Human Orthopneumovirus) is an enveloped linear single stranded non-segmented negative sense RNA virus which is the principal member of the Orthopneumovirus genus under the family pneumoviridae which falls under the Mononegavirales order of the monojiviricetes class. The RSV virion electron micrograph depicts the virus to be roughly spherical / ovoid with an estimated average diameter of 150 – 300 nm (but may vary between 100- 340 nm.) with envelope spikes of 13- 17 nm. It may be noted that the RSV virions from certain cell culture extracts also appear heterogeneous and pleomorphic (irregular) varying from an oblate circular shape to even filamentous forms reaching up to 10-micron length with 30 – 110-micron radius (Jeffrey et al 2003). These filaments are numerous in cell culture extracts and are thought to be virions protruding out from the infected cell surface. (Or sites of viral budding). Sucrose gradient (= isopycnic) centrifugation can be used to separate the filamentous and spherical forms. The recorded buoyant density of the virions is 1.18 g/ml. The 6 sequenced strains of RSV viruses suggest a total genome size of 15- 15.33 kilo base pairs (average being 15.22 kb of strain A2) with a G+C content of 33.3% and there are 10 genes with 11 ORFs. The genomic RNA has a molecular weight of 5 mega Daltons (MDa) & codes for 11 different proteins, each polypeptide being made from a separate mRNA (so in total 11 sub genomic mRNAs) each of which are produced from their respective ORFs. The genomic RNA often referred to as the antisense RNA has the genes which are named from abbreviations of their respective proteins in the following order 3’- NS1- NS2- N- P- M- SH- G- F- M2- L- 5’. When compared to other paramyxoviral families, 2 differences are notable a) the relative order of fusion and attachment protein genes for RSV follows the reverse order and b) RSV has a small hydrophobic gene between the matrix and attachment genes. There is an extragenic leader (le) sequence of 44 nucleotides which occurs just before the start of the NS1 gene at the 3’ end and an extragenic trailer region of 155 nucleotides which occurs right after the L gene at the 5’ end. A remarkable feature is that the leader and trailer sequences hold complementarity in 16 of the 22 terminal nucleotides. A virally encoded transcriptase is brought along with the gRNA. This transcriptase is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (= RdRP) and the same has also been referred to as the viral replicase by certain authors for the same polymerase catalyses the replication process in the later stages to generate a complete length complementary antigenome (often called as the replication intermediate). RSV follows a sequential and linear polar gradient transcription type. There is a single viral promoter at the 3’ end before the start of the genes. Each gene has start and stop signals often attributed as GS and GE signals respectively. Based on the viral strain differences, there occurs about 1- 58 nucleotide gap (intergenic length) between the first 9 genes of RSV. The M2 gene is quite special because it has 2 overlapping ORFs that generate 2 mRNAs which encode for 2 RNAs, M2-1 and M2-2. Also, there is a 68 nucleotide overlap between the M2 and L genes which is quite peculiar because the GS signal of the L gene occurs before the end of GE signal of the M2 gene. There is a small difference between the RSV GE sequence and GE sequences of the other paramyxoviruses. The RSV virions are enveloped, the lipids of which are derived from plasmalemma of the host cell. The envelope is studded with 3 glycoproteins of viral origin namely the G protein, F protein and SH protein. The envelope glycoproteins namely the G protein and the F protein catalyzes the initial steps of virus entry into the host, the former mediating the attachment (1° step; hence called attachment glycoprotein and the latter mediating the secondary step of viral fusion with the plasma membrane of the host cell (earning the title of fusion protein) and delivery of the virus into the cytoplasm. The viral nucleocapsid is thus delivered to the cytoplasm. The nucleocapsid of the RSV is helical composed of the gRNA tightly attached to the nucleoprotein. The diameter and the pitch of the nucleocapsid are between 14 – 16 nm and 6.8 – 7.4 nm respectively, the helix diameter being significantly lower than the rest members of paramyxoviridae (Bherk et al 2002). The antigenome too get sealed with the nucleocapsid like that of the genome so that they get spared from the cytoplasmic RNases. Also, the nucleocapsid genome association provides the latter from host PRR surveillance particularly those of RIG-1 and melanoma differentiation associated protein (MDA – 5) thus limiting the type 1 interferon response and proinflammatory cytokine activation. RNA replication occurs within the cytoplasm and requires no aid from the nucleus and the viral replication complexes are found much away from the nucleus due to which the host cell never suffers shut off its native genes. The cytosolic inclusions seem to be highly sense when RNA replication in the later stages become clubbed with continuous and nonstop structual and late protein synthesis. The virus lacks neuraminidase and hemagglutinin activity differentiating it from other paramyxoviridae. RSV is highly fragile and nonwarty. The virions lose infectivity when stored at -70 ° C for even minute time periods. Virus also gets inactivated at room temperature. Virions which are sonicated have low infectivity. RSV is highly susceptible to organic solvents and ultra-sensitive to Triton X- 100, sodium deoxycholate and 1% NaOCl) and similar detergents because of its lipid envelope. About 5% of formaldehyde, 2% of glutaraldehyde and iodophors etc have been shown to be highly virucidal towards RSV. Just 1 minute contact with chlorhexidine digluconate,(1%) benzylalkonium chloride (1%) renders the virus ineffective.Virus when heated for 56°C for just 5 minutes loses up to 92% of its infectivity. RSV is also highly susceptible to acidic media and is super sensitive to freeze thawing losing about 90% of its infectivity. Virus is sensitive to drugs like Ribavirin. RSV can’t tolerate drying and is highly vulnerable to temperature changes. RSv loses infectivity more rapidly on inanimate surfaces. The infective dose is greater than 160 – 640 viral units (NIH). RSV has no vectors involved in disease transmission.

a) RSV proteins

L ----------- RNA dependent RNA Polymerase. G -----Attachment protein

N ---------- Nucleocapsid protein F ------Fusion protein

P ----------- Phosphoprotein SH---- Strongly hydrophobic protein

M2-1-------Transcription processivity factor M -----Matrix protein

NS- 1 --------------------------Non structural protein – 1

NS- 2 --------------------------- Non structural protein – 2

M2 – 2 --------------------------- Regulatory switch protein.

F glycoprotein

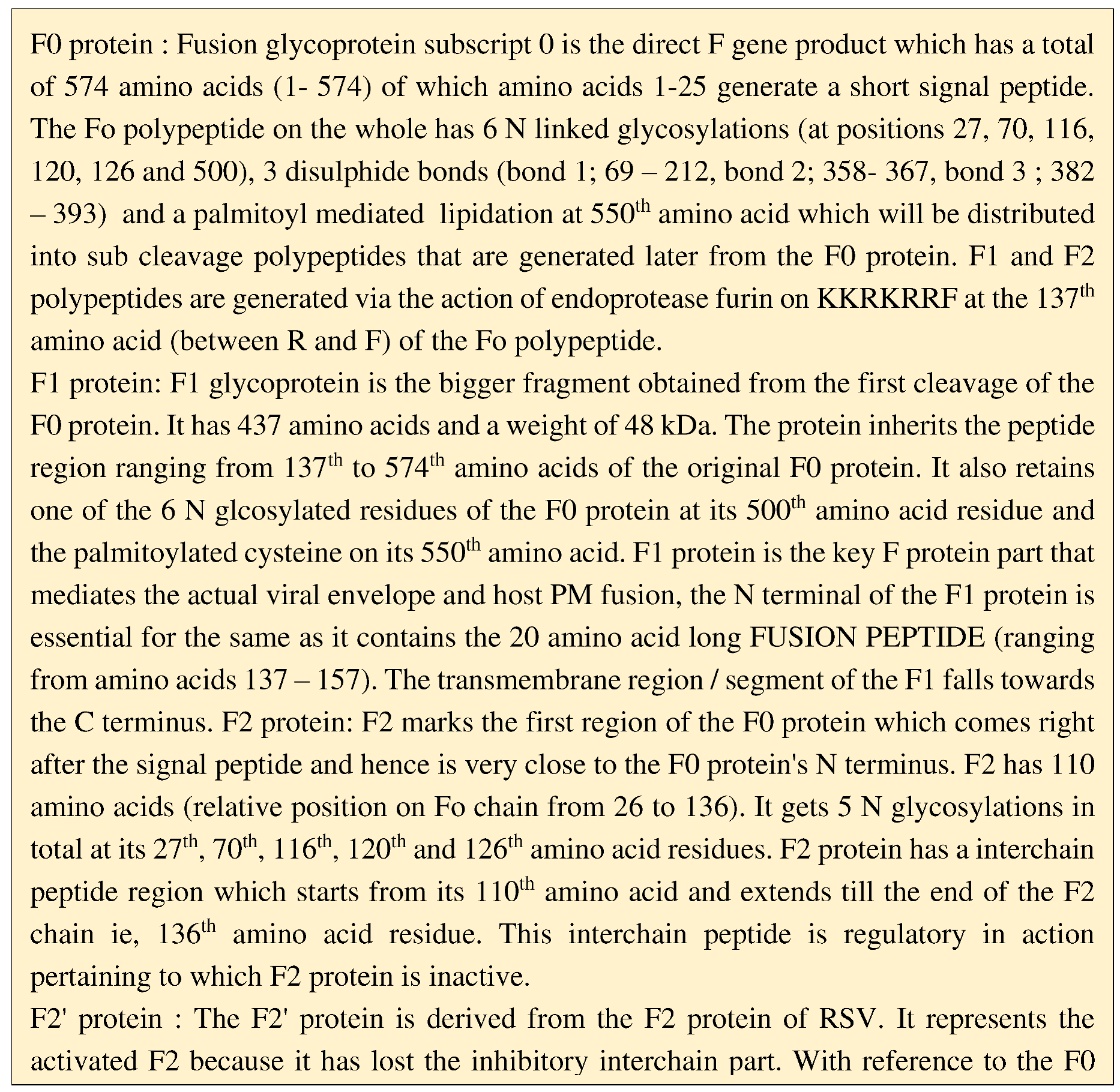

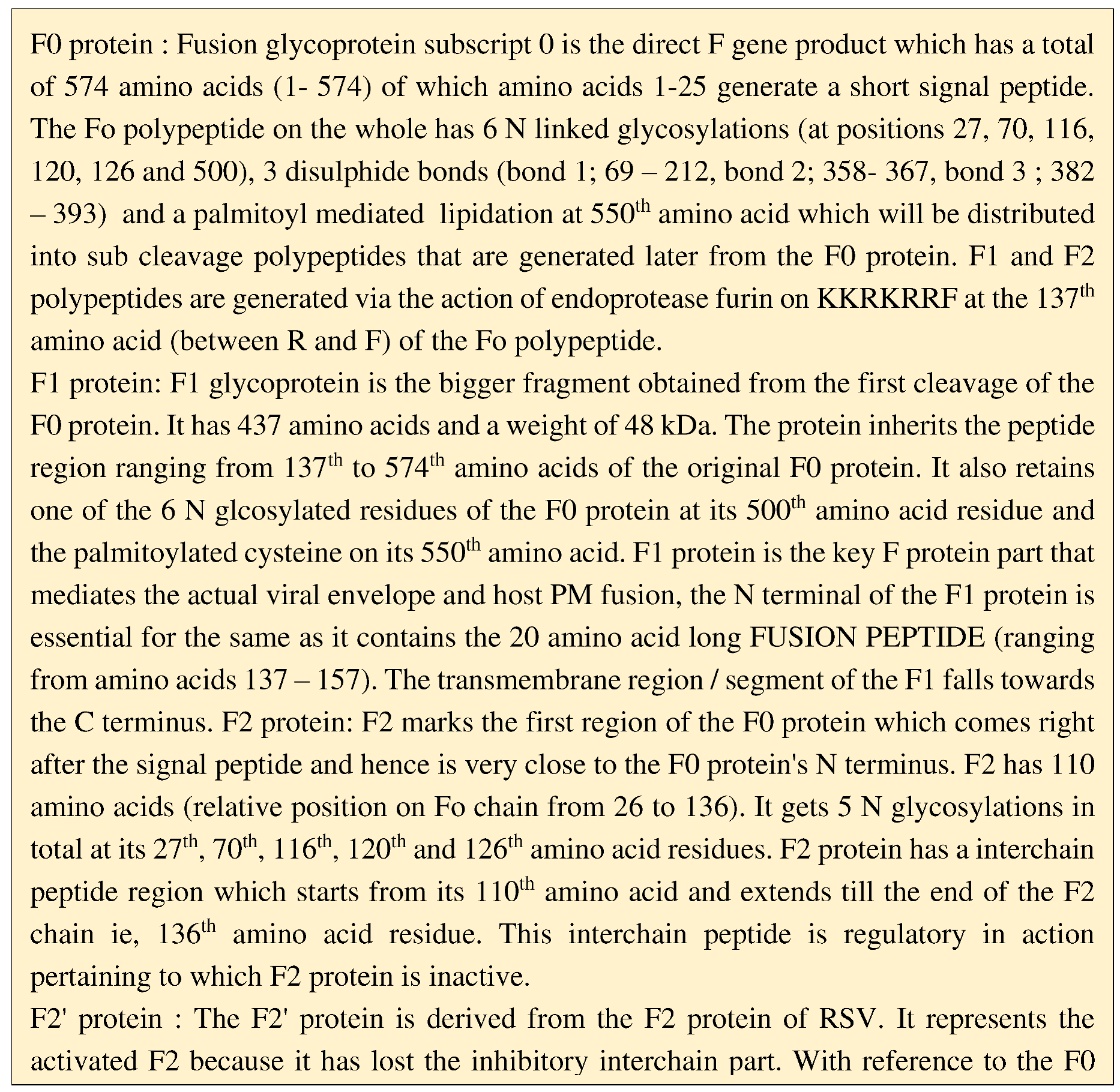

F glycoprotein refers to the abbreviated form of fusion glycoprotein. It is expressed throughout the infection cycle, and it is activated at physiological pH. The F protein has high structural resemblance and is quite similar to the F protein of other members in the paramyxoviridae family with reference to the overall length and location of hydrophobic domains, carbohydrate moeities, cysteine residues and cleavage sites (Collins et al 1984; Elango et al 1985; Spriggs et al 1986). As the name suggests, the F protein is the one responsible for mediating the fusion of the virion envelope with the host plasma membrane which is the second step that facilitates the viral entry to the host. The F protein is coded by the F gene via the 8th subgenomic mRNA (in the sequential order of transcription). RSV F protein was identified through interactions between cells and different developed monoclonal antibodies (generated using the entire RSV virion) which led to the characterisation of a specific antibody from the lot that prevented multinucleated giant cell / syncytia formation in those in vitro cultured cells. (Walsh and Hruska 1983). The actual term F protein involves some ambiguity for it is often confused with its generator / precursor protein F0. It may be noted that the functional F protein is a type 1 transmembrane surface protein that is present in the virion envelope (with its C terminal acting as membrane anchor and a cleavage signal peptide at Its N terminus and made up of F1 and F2 subunits. The F1 of the F protein through its hydrophobic N terminus is responsible for the direct fusion of viral envelope with the host cell membrane. It is to be taken into note that the F protein is synthesised as a 68- 70 KDa (based on strain variation) precursor which is transcribed from the F gene by the polymerase L and finally translated into a 574 amino acid long nascent Fo polypeptide/ protein having about 5-6 glycans attached depending upon the strain type (Collins et al 1984). This F0 protein of the RSV is considerably bigger than the Measles and Mumps virus precursors each of which measures only 57 KDa and 59 KDa respectively. The F0 precursors are synthesised on ER bound ribosomes. The F0 protein then achieves a 4° structure on account of assembly of 3 Fo protomers (Bolt et al 2000; Collins et al 1991). The RSV F0 protein trimer is cleaved post 136th amino acid within the trans Golgi compartment by furin or furin like endonuclease to finally yield 2 disulphide linked subunits [ H2N-F2-S-S-F1-COOH]. (Gruber & Levine, 1985; Ferne et al 1985; Huang et al 1988). The F1(glycosylated and acylated C terminal cleavage product of F0) generated post furin cleavage is larger & weighs about 48 KDa and has a single N linked glycan attached whereas the smaller F2 (glycosylated N terminal cleavage product) weighs about 20 KDa possessing 2 N linked glycans. The unique property of RSV F0 protein is that it has 2 cleavage sites for the endoprotease whereas all the other paramyxoviral genera has just 1 site available for the activity of the endoprotease; KKRKRR•F (cleavage at 137th amino acid) peptide is cleaved between the arginine and phenylalanine residues (cleavage 1) which is found amongst other paramyxoviridae as well but the 2nd one located 27 amino acids upstream to the former site of cleavage; the RARR•E (Cleavage at 110th amino acid) peptide with cleavage site between arginine and glutamic acid. The 3rd product of furin cleavage (an intervening sequence of 27 peptides) will permanently dissociate and takes along with it 2 – 3 N linked glycans. The F proteins of HRSV A and HRSV has an amino acid sequence similarly of 89%. The exact no of amino acid residues (peptide chain lengths) and other positional modifications of the F protein is discussed in the table.

The signal peptide is responsible for directing the protein which is newly synthesised via co translatational translocation into the RER. The F protein of the RSV has to be transported to the membrane of the cell ; if there is no hydrophobic domain for this protein there are high chances that the protein may be sereted out/ lost. To prevent the same amino acids from 525 to 550 serves as the stop transfer signal thus anchoring the F protein in the cell membrane retaining internally the last 24 amino acids which forms the cytoplasmic domain for the F protein.

The F1 protein of RSV is quite significant because it carries the fragment which is responsible for the fusogenic action. The F protein has been given different designations as pre fusion F protein and post fusion F protein pertaining to the F1 protein subpart transition between the Native / Non fusogenic state and Active / Fusogenic state. The fusion peptide of the F1 in its inactive state is not accessible as its hydrophobic glycine rich part is deeply sequestered (the part being exposed only after a suitable trigger). This state of the F1 protein which is present on the RSV virion (that hasn’t contacted the host cell) renders only metastability to this virion with the virion membrane deeply anchoring the F1 TM region at its c terminus. This conformation of the F protein is widely called the prefusion configuration and this can’t carry out the fusion process. Upon examining the F1 polypeptide it is seen that between the N terminus fusion peptide and the Transmembrane helix at C terminus there lies 2 types of heptad repeats (HR) which are separated from each other by a peptide sequence of 27 amino acids which is commonly known as pep27. Situated about 4 to 11 amino acids from the TM anchor within the F1 C terminus is a leucine zipper resembling motif (which is highly conserved across genuses of paramyxoviridae) made up of 3 – 5 heptad repeats. right next to the signal peptide there lies about another 4 heptad repeats which is the key mediator of F1 peptide fusion with host membrane. These heptads repeat sequences function just like a Dynamo switch which leads to propulsive forging of the fusion peptide into the cells PM. Both the HR-N (heptad repeat near amino terminus) and HR – C (heptad repeat near F1 C terminus) via the formation of trimeric hairpin like structures gives outthrust to fusion peptide. For this the HR-N first forms a coiled – coil domain on which HR-C stacks itself on the outer side in antiparallel fashion forming a stable 6 (hexa) helix bundle. Each F protein out of the F trimer complex develops within its F1 protein a hairpin; thus, altogether forming hairpin trimers which is the key for opening the Native state lock of the F protein. So, the series of events that occur are as follows; The virus initially is in its native form where both fusion peptide and heptads are inaccessible. 2) A pre-hairpin intermediate is formed following which HR-N is made accessible after which the fusion peptide stays projected. 3) Fusogenic hairpin forms via proper association of HR- N and HR-C which leads to the fusion of viral envelope and host PM.

RSV F protein is the most important of the virion proteins for RSV deletion mutants for the F gene fail to infect cells on their own and require the help of helper viruses to facilitate their entry into the host cell.

G glycoprotein

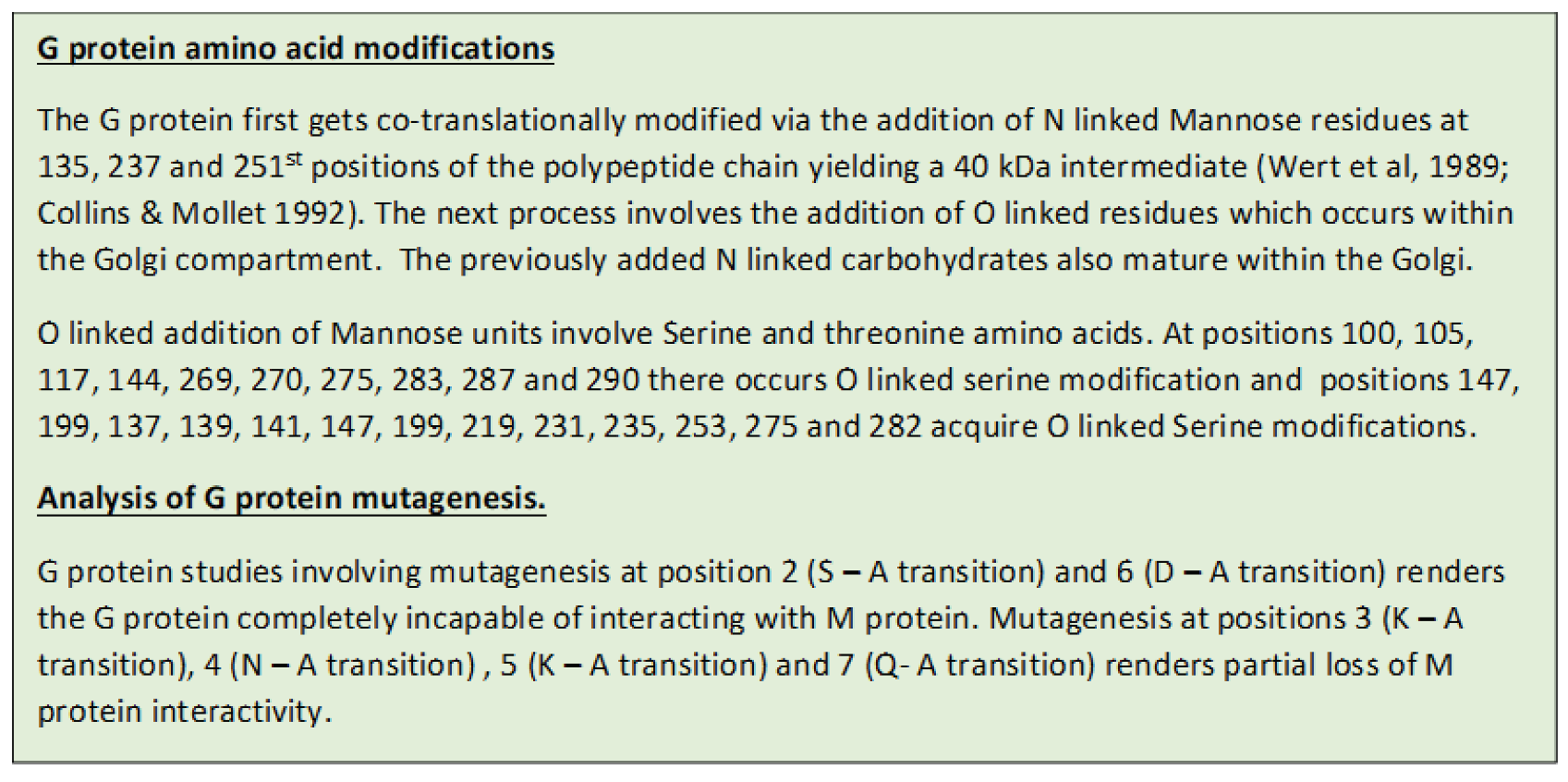

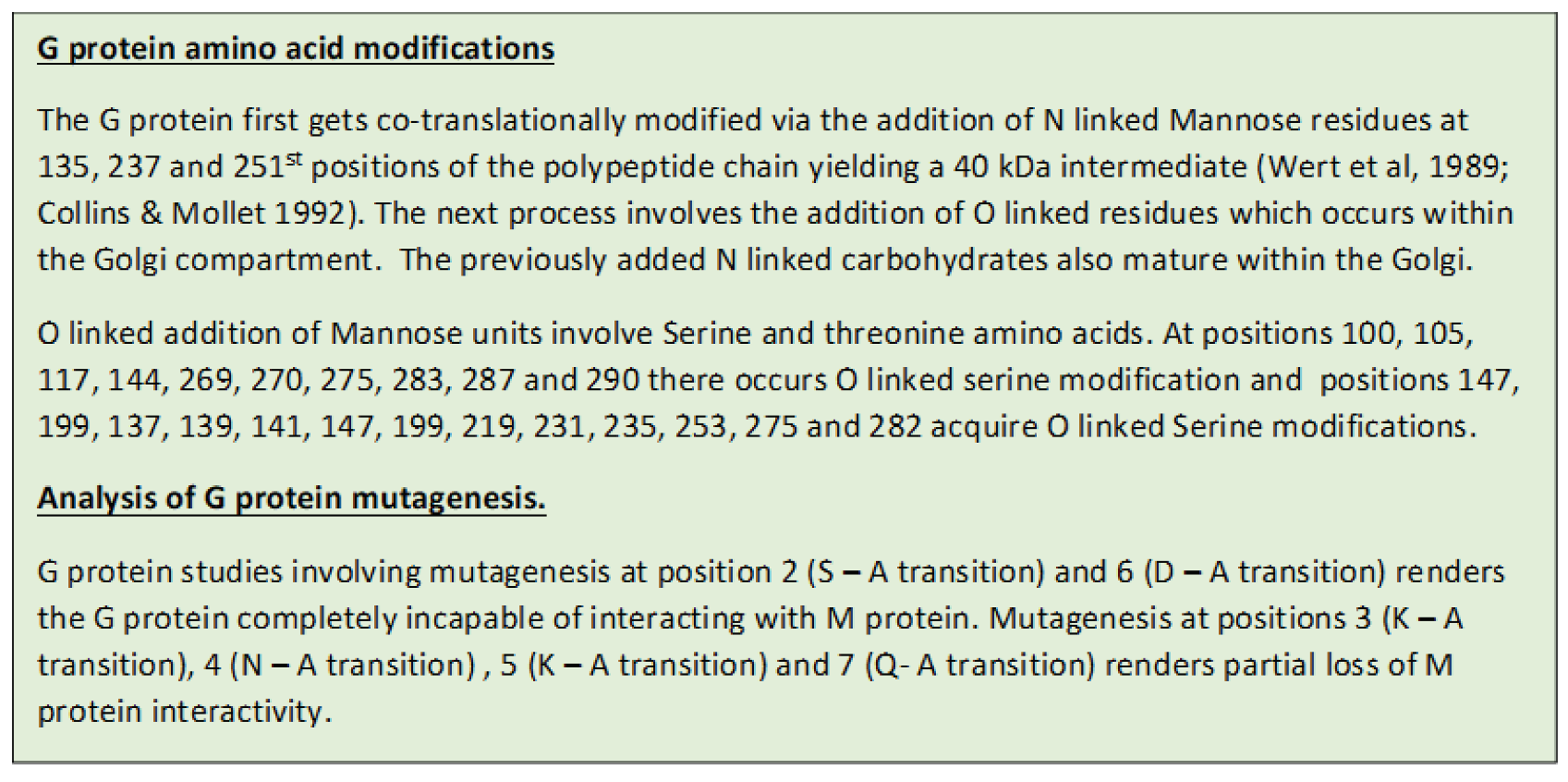

The G glycoprotein is one of the principal glycoproteins besides the F glycoprotein that is found on the RSV virion envelope. It is the RSV 7th cistron translational product. On contrary to the F protein, which is highly similar among the HRSV groups, the G protein is loosely conserved among the RSV strains (being the most variable protein) and there occurs only 53% similarity between HRSV group A and HRSV group B. The G protein is also invariably called as the major surface glycoprotein / membrane bound glycoprotein / Attachment glycoprotein. Both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against the G protein block the RSV virion mediated host cell targeting. The glycoprotein weighs around 84 – 90 KDa with 298 amino acids and it is that specific protein of the RSV to be modified post translationally the most for intense number of changes are made due to which the protein gains upto 58 KDa (The weight of the nascent unmodified polypeptide being only 32.586 KDa). The G protein is completely absent from the Mumps, Measles and Parainfluenza genomes. G protein is also unable to bestow haemagglutinnin and neuraminidase activity which are characteristic properties of other paramyxoviruses, and it is highly different from HN and H attachment proteins of other viruses. G protein is involved in the 1st step of virion – cell surface attachment (Levine et al 1987). The initial G protein mediated virion docking on the host plasma membrane leaves about 9 to 12 nm apart. The G protein is a type 2 integral virion membrane protein having 3 different domains; a) the external surface/ membrane Shell domain: This domain being the largest with a peptide length of 231 amino acids (67 – 298). b) the Transmembrane domain which extends from 38th to 66th position of the G protein (28 amino acids long) anchoring the G protein firmly into the virion membrane / coat. c) Finally, a topological intravirion internal domain extending from 1st to 37th position (N terminus) of the G protein. The region upto the TM has been conserved among RSV strains and the rest peptide length till the Carboxy terminal of the G protein is variable region. However, within this variable region lies a super conserved potent region which is a characterstic of all RSVs. Following its synthesis as a polypeptide from the G gene transcript the protein gets heavily glycosylated at three of its amino acids namely serine, threonine and asparagine the first two harbouring O-linked glycosylations and the last one bearing N linked glycosylations. A large fraction of the carbohydrate moeity attached serine and threonine amino acids are present within the G protein at its two large ecto domains which bestows it with high mucin resemblance. 97% of infectivity is lost in vitro when the carbohydrates within the G protein of RSV virions are digested with N and O glycanase which respectively removes N and O linked glycans (Lambert 1988). G protein has been showed to possess high affinity to negatively charged cell surface molecules basically the glycosaminoglycan’s (GAGs) , heparin sulphate, Chondroitin sulphate B which earlier has been already demonstrated as those significant for the invitro infections. The rate of RSV attachment is highly low (= insignificant) in GAG deficient CHO cells. There are 2 forms of the RSV G protein the first one being the full length membranous bound form and the second one being the secreted form of the G protein (monomeric) that lacks the membrane anchor due to 2nd AUG mediated translatation initiation happens within the ORF. Serogroups A and B are classified based on the differences in their G protein. Owing to lack of high similarity in G protein sequences of Serogroup A and B it has been shown that antibodies generated against Serogroup A offer little or no protection against B antigen. Each serogroup has its own characteristic C terminal conserved G protein ecto domain region which is remarkably rich in hydrophobic residues (it includes 3Fs, 2Vs and 2Cs amino acids) and lacking glycosylations, which remain conserved amongst all strains that fall under that group. In Serogroup A, a 13 amino acid segment (positioned between His 164th and Lys 176th amino acids) form the central conserved domain. Very close to this lies the TNF receptor analogy bearing Cysteine Noose Domain (CND) formed with the involvement of 4 cys residues located at the 173rd, 176th, 182nd and 186th positions with 2 disulphide bond formation between 173rd and 186th and between 176th and 182nd amino acids respectively. RSV strain variation is acquired through high level of sequence differences within the regions that flank the previously described Cysteine Noose which are called hypervariable regions. Before the start of the hypervariable region there’s a short peptide segment of 15 amino acids which occurs right next to the Noose region (184 – 198) that is involved in binding of the G protein to GAGs (Fedman et al, 1999). The nucleotides 588 – 654 of the G gene contain about 3 runs of 6-7 adenosine residues which is highly flexible to indels (insertions and deletions). This leads to drastic changes within the amino acid sequences of the Carboxy 1/3rd of the G protein. G protein interacts with matrix protein via its N terminus (cytoplasmic domain) and it also interacts with F and SH proteins present on the envelope. The G protein is capable of interaction with the fractalkine receptor (receptor for CXC3 chemokine / fractalkine) thus modulating immune responses.

SH protein

The small hydrophobic / strong and short hydrophobic protein is another type 2 (single pass)integral membrane protein present on the virion coat surface in very low quantities which performs the function of a viroporin via the formation of pentameric porous cation selective ion channels (Carter et al 2010; Gan et al 2012) thus capable of altering the membrane permeability. The full-length SH polypeptide product of the SH gene (6th cistron) contains about 64 amino acids with a molecular weight of 7.5 KDa. This HRSV SH protein is 3 times shorter when compared to the HMPV counterpart which has about 177 – 183 amino acids. The SH protein can be differentiated into 3 different domains the first 20 Amino acids forming the intravirion topological domain the next 24 amino acids forming the helical Transmembrane anchor and finally the last 20 amino acids (C terminus) forming virion surface topological domain (= ectodomain). Within the infected cell 4 different types of SH protein has been characterized; type 0 form / SH – 0 (No side chain form) which is the non-glycosylated true SH gene full mRNA product, small side chain SH product weighing about 13- 15 KDa with 2 N linked high mannose type carb attached (SHg) , large side chain containing polylactosaminoglycan modified form weighing about 21 – 30 KDa (SHp) and finally a truncated unmodified product of 42 amino acids (SHt) obtained via translatation initiation through the 2nd AUG (23rd amino acid { met 23) of the mRNA) (Anderson et al 1992; Collins and Mottel, 1993). All these different forms however assembled to form homooligomers when they were subjected to sedimentation by sucrose gradients. The exact functional role played by SH protein is still obscure, however certain evidence throws light on many aspects within the host cell that are regulated by the SH protein. Firstly, SH can modify the host cell membrane permeability which disrupts the host cell ion gradients thus affecting homeostatis. (When homeostatis is affected, it leads to NLR- P3 inflammasome triggering and activation of Danger / Damage associated molecular patterns). High concentrations of SH protein are detected within the Golgi apparatus and secretory vesicles of the infected cells which downregulates the rate of cell’s native protein secretion and improves viral transport and release. SH has also been shown to downregulate cellular apoptosis thus providing the virus adequate time to mediate its processes within the cells (Fuentes et al 2007). High SH protein production also accounted for decrease in the cells ability to produce the proinflammatory cytokine TNF – alpha. Pyronin B inhibited the cation selective channel activity of the SH protein. SH protein is not at all necessary for the completion of the virus cycle as SH Delta Virions undertake the synthesis of their progeny efficiently.

M protein

The M or the matrix protein is a key protein that is about 256 amino acids long. It plays a highly important role in the morphogenesis of the virus, and it is a protein that gets closely associated with viral cytoplasmic inclusion bodies. M protein functions as the checkpoint to limit the viral RNA replication and to prepare the packaging of the same into the Virions (Ghildyal et al 2006). The absence of the M protein led to defects in RSV filament formation for it was immature and stunted (Mitra et al, 2009). The M protein is an internal virion component. The RSV M protein is smaller than other paramyxoviridae counterparts and it also lacks profound sequence relatedness with those of others. The N terminal and C terminal domains are joined by a short linker (Money et al, 2009). M protein N and C terminal domains are positively charged for interacting with the nucleocapsid and membrane which are negatively charged. The protein is also required for the transport of progeny nucleocapsids from their respective inclusion bodies to the plasma membrane (Mitra et al, 2012).

L protein

L protein refers to large structural protein. It is a protein which performs dual functions that of replication and transcription. The protein shows 5’- 3’ polymerase activity and has a length of 2,165 amino acids and a mass of 250,490 Da. The RdRP catalytic domain extends from the 693rd amino acid to 877th amino acid encompassing a total of 185 amino acids. The L protein also functions as the methyl transferase or capper protein as it is responsible for the addition of cap onto the mRNAs. The replication mode of the L protein depends upon intracellular N protein concentration. When the protein works in this mode it doesn’t recognise the transcription signals.

P protein

P protein is the abbreviated form of Phosphoprotein which also has been termed as the cofactor protein for it serves in the stabilisation of Protein L together with the positioning of the polymerase complex onto the nucleocapsid. The protein weighs about 27.148 KDa and has an expanse of 241 amino acids wherein the positions 116, 117, 119, 143, 156, 161, 232 and 233 contain rare / modified amino acid phosphoserine (the serine at these positions getting phosphorylated by the host post translationally). The polyprotein part extending from amino acids 232 to 241 forms the major N protein binding domain and the part encompassing amino acids 120 to 150 forms an oligomerisation domain the central part of the same containing a coiled coil domain. The P protein is known for its ability to interact with M2-1, this interaction being unavoidable for the protein M2-1 to perform its antitermination and transcription elongation properties. P protein has a unique ability to bind to N protein monomers and catalyse their delivery to nascent viral genomes and antigenomes thus preventing the N proteins from self-aggregation or from recognising host RNA (Castagne et al, 2009). The P protein is often given the title of roleplayer of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation processes.

N protein

N protein, also termed as the Nucleoprotein, is a medium sized protein having a length of 391 amino acid monomers and an average mass of 43.451 KDa. It encapsidated the viral genome (binds to the genomic RNA) and protects the same from degradation by RNAses. It interacts with the P protein and positions RNA polymerase onto the viral RNA. It mediates its interaction with matrix protein via the help of M2-1 protein. Many N protein monomers closely associate to form the typical helical RSV nucleocapsid. Each N protomer contains one N terminal and one C terminal domain connected by a hinge. 1 N monomer has the capability to associate with 7 nucleotides/ basepairs of the viral RNA. It may be noted that inorder to provide flexibility for polymerase access the monomers are quite loosely adhered so that during transcription or replication the helix doesn’t get disrupted. The N protein attains its unique capability to orient the nucleotides 2,3 and 4 (out of the total associated 7) called the buried nucleotides into the groove and the remaining 4 to face outwards. When the polymerase is in activity it induces a specific reaction in the N protein hinge region so that the earlier 3 buried nucleotides get now exposed (Tawar et al, 2009). N protein is also known to inhibit the protein synthesis slightly by preventing the eIF2a from getting phosphorylated through the blocking of double stranded RNA regulated protein kinase (PKR).

M2-1 protein

The gene M2-1 codes for this polypeptide with a molecular weight of about 22.154 KDa and a polypeptide chain length of 192-194 amino acids. This protein also widely referred to as the 22 KDa / 22 K protein plays a significant role of improving the processivity of transcription (Fearns and Collins 1999). The same protein also acts as an antitermination factor used to prevent the formation of abortive or premature transcripts. The protein has modified phosphorylated residues at 58th and 61st amino acids. The 22K protein has a zinc finger motif (of CCCH type) at its N terminus which is highly important for exhibiting RNA synthesis anti termination function (Hardy and Wertz, 2000). M2-1 protein is also known to undertake M protein transport from the cytoplasm to the viral inclusion bodies and establishing interaction with nucleocapsid (Li et al, 2008).

M2-2 protein

It is a protein weighing about 10.674 KDa containing 88 or 90 (more common) amino acids depending upon start site (Chang et al, 2005). The protein undertakes the function of a regulatory switch decreasing transcription and increasing RNA replication rates therefore lack of this protein results in a virus which shows increased transcription rates but decreased replication rates. The rate of M2-2 RNA expression is quite low in infected cells but the synthesis of the same can’t be compromised.

Nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2

The NS1 and NS2 proteins are coded respectively by the genes 1C and 1B of RSV RNA respectively. The former has an average weight of 15.567 KDa and contains 140 amino acids and the latter weighs about 14.702 KDa made up of 125 amino acids. The NS proteins function as suppressors of certain cellular responses some of these have been discerned as of now; via the help of NF- kB the proteins block premature apoptosis, both the proteins together lead to inhibition of IFN production in the infected cells by repressing the activation as well as nuclear translocation of host Interferon regulatory factor (= IRF)3. The proteins inhibit the signalling through RLHs via blockage of MAVS interaction with RIG 1. The protein also is responsible for causing the proteosomal degradation of STAT-2. p

4. Life Cycle of RSV

RSV first attaches to the host cells via the heparin binding domain of the surface Glycoprotein G (= attachment Glycoprotein), the host cell receptor for the same being Glycosaminoglycans.

Virion envelope then fuses with the cell membrane by the action of fusion Glycoprotein.

The next step involves the release of the genomic RNA and associated proteins into the cytoplasm.

The L protein and P protein interact with this newly released RNA constituting the active viral transcriptase (RdRP) which leads to the synthesis of multiple capped and polyadenylated subgenomic RNA. (Viral mRNA is detected 4-hour post infection within the cytoplasm)

The mRNAs that are generated undergo translatation thus leading to the synthesis of viral proteins.

After appropriate signals the viral RdRP undergoes a transition from its transccriptive function to the replicative function as a result of which full length gRNA complement commonly referred to as the antigenomes are produced.

These antigenomes that are synthesized further act as intermediates in the generation of the full-length negative sense RNA which are referred to as progeny genomes.

There is a hike in protein production where the late or virus structural proteins along with the assembly proteins are synthesised.

Genome and associated proteins are assembled and following maturation the progeny virus buds off through the plasma membrane.

a) Transcription

Transcription of all the genes occurs through only 1 promoter called the Le promoter. For undertaking the transcription process the RNA polymerase enters through the 3’ end of the genomic RNA and copies the genes / cistrons into individual corresponding mRNAs by the aid of gene start (GS) and gene end (GE) signals (Kiro 1996). The mRNAs don’t get encapsidated. The capping of the emerging mRNA is a necessary step for it allows theRNA pol to remain in stable elongation mode. The RNA pol itself carries out polyadenylation of the mRNA before starting onto the next GS signal. The transcription process (1°) starts at the most distal 3’ end of the viral RNA ie, at the promoter Le. The RNA pol first gives rise to an RNA which is complementary to the leader gene initiating an abortive transcription. The RNA pol in RSV is highly known for its ability to cease and resume the transcription process as and when required and it can surpass / or glide over few intervening nucleotides. However, it may be noted that during the skipping of intermittent regions the RNA pol complex can also fall off the template as a repercussion of which a viral RNA concentration gradient is established within the host cytoplasm along the direction of the transcription.

b) Replication

Just like the other negative sense non segmented single stranded RNA viruses the RSV also has within the genome 1 promoter for initiating the RNA replication at its 3’ end which is referred to as the leader (Le) sequence. Similarly, the 3’ end of the antigenome also contains a promoter in a region which is referred to as the trailer complement (Trc) (Mink et al 1991). Functional differences lie between Le and Trc promoters, the latter being stronger than the former as it accounts for higher levels of RNA replication (Fearns et al 2000; Hanley et al 2010). The initiation of replication process is poorly understood till date. It must be noted that during the replication process none of the nucleotides at the terminal end should be spared for it will lead to the production of truncated RNAs; hence forth the replication initiation should be highly controlled. Unlike members of the segmented negative strand viruses which initiates the replication by prime realignment method (where a pol does internal initiation to generate a short oligonucleotide primer followed by repositioning so that primer annealing at the 3’ end is achieved), this process is absent in segmented negative sense RNA members of the Paramyxoviridae family. RSV protein-based registering of the RdRP is also not characterized till date. The process of encapsidation is necessary to trigger an increase in speed and processivity of the RNA pol thus enabling it to read through intermittent GE signals.

5. Pathogenesis

RSV pathogenesis works as a combined repercussion of both direct viral replication mediated and cytotoxicity (= immune) mediated outcomes. HRSV infection has inhibitory effects on host DNA and RNA synthesis and, but it renders no hindrance in the host's protein production. HRSV establishes the infection in the airway cells and has a good tropism for other lung tissues as well. Fatal cases of HRSV suggest the infection to be mostly contained within ciliated cells but to a smaller extent non-ciliated cells are involved. The basal cells are usually spared. With progression of the RSV disease those ciliated cells which got infected gets destroyed marked by necrosis and hyper-plasticity of cells. In the earliest stage of the infection the Macrophages and PMNL are first summoned which is later followed by the arrival of plasma cells and lymphocytes. Once there is hike in the lymphocyte count and high influx of periobronchial infiltrate mucus and edematous fluid secretion is seen. The submucosal tissues also get fluid filled. The inflammatory cells, along with debris and mucus obstruct the alveoli and bronchioles which may culminate in respiratory collapse together with emphysema. Thickening of internal alveolar walls along with rapid mononuclear infiltration when severe progress into pneumonia. The epithelial cells of the alveoli, and bronchiolar epithelium have high virus loads. Hypervirulent RSV strains result in large syncytia formation. CSF and myocardium also suffer from containing viral loads. Circulating monocytes also harbour the virus.

The virus provokes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in those cells like macrophages and dendritic cells that are infected by the virus. The excessive degranulation of recruited neutrophils forms an important part of pathogenesis. The specific factors released from granulocytes such as neutrophil elastase which are antimicrobial also contribute to pathogenicity when produced in large amounts thus damaging the cells. Over robust T- cells (cytotoxic T cells) also results in tissue damage. After the infection of a host cell the host response is modulated by RSV proteins. NS-1 & NS-2 proteins improve the viral survival in infected cells by blocking interferon alpha and beta profuction. RSV can also infect the stromal cells of the bone marrow leading to altered chemokine and cytokine expression together with decrease in the ability to stimulate B cell maturation. RSV also hinders the interaction between dendritic cells and T helper cells. (Gonzalez et al 2012). RSV induced TGF- beta expression caused cell cycle arrest and subsequent enhancement of RSV replication. RSV RNA binds directly to P53(functioning as cis acting enhancer) to increase the rate of replication. RSV infected cells show a high expression of antiapoptotic molecules like Bcl2 family members such as Bcl-XL and myeloid cell leukemia1.

6. Immunity against RSV

a) Innate immunity

The different levels of the immune system join hands to ward off the RSV infection from the body. The effector and potent cells of the innate immune system first contribute a blow to the invading RSV. RSV mainly infects the ciliated cells of the respiratory epithelia (CREC) by the binding of the Glycoprotein G to the CXCR1 that is present on apical side of the ciliated epithelium. When the pathogen first invades the respiratory epithelia, the Resident Macrophages responds to the RSV through the interactions with their surface PRRs which recognises the PAMPs on the RSV. The macrophage recognises the RSV F protein epitope with the help of TLR 4 and coreceptor CD14. Further on interaction with the MyD88 adaptor a signalling Cascade is ensued leading to the induction of genes that code for proinflammatory cytokines. If the virus gets inside the macrophages then during the stage of RSV multiplication dsRNA intermediate is recognized by the cytosolic PRRs those of which include RLH/ Rig-1 Like Helicases (retinoic acid inducing gene 1) and those RNA sensors like Melanoma differentiation associated protein 5 which puts forth a cascading towards type 1 interferon production via mitochondrial antiviral signalling mediated through MAVS protein and caspases activation and recruitment domains (CARDS) interaction. The various proinflammatory cytokines like IL1 , IL-6, IL12, TNF-alpha are secreted via the induction of the macrophages. Together with this chemokine like IL-8 are also secreted. The chemokines thus secreted are important for calling upon the neutrophils to the infection site. These cells are the 1st line of cellular barriers that engage in fighting the alien. The examination of the various samples of the bronchoalveolar lavage has shown the presence of deeply infiltrating Neutrophils even in the narrowest of the air passages. Neutrophils also function as the key pathological modulators of RSV induced bronchiolitis (Wang et al 2000). The summoning of the neutrophils from plasma into the infected airway occurs via namely 4 steps which include rolling, adhesion, extravasation and migration (Mc Namara 2002). The rolling step along the endothelium is via the formation of weak initial bonds with the help of L – selectin (Wang & Forsyth, 2000). Following the rolling in the next step the neutrophils via the aid of ICAM1 on the endothelial cells and its known ligands on the neutrophils such as LFA1, CD11a, CD11b the Anchorage happens. In the next step following the increasing gradients of IL8 cytokine the neutrophils wriggle through the space by pushing endothelial cells. Provided the site of highest concentration of IL – 8 is reached the neutrophils lodge there and get activated via the inflammatory set of cytokines released by the infected epithelial cells however other studies also suggest an inherent property of RSV to directly induce neutrophil activating potential. (koning et al, 1996; Jaovisidha et al, 1999). Following the activation / induction of neutrophils there occurs a hike in the release of substances like those of myeloperoxidase and neutrophil elastase which can be demonstrated within the airways (Harb et al 1999). The activated neutrophils also secrete IL – 19 which being a highly powerful proinflammatory cytokine is responsible for calling upon eosinophils to the mileu. RSV is also capable of multiplying in the neutrophils. Neutrophils are also attributed to carry the virus to the peripheral blood ie, from lungs to the circulation. Neutrophils are known to bestow microbicidal activities and they contain various no of antimicrobial proteins and peptides. Intracellular killing through peroxidases, myeloperoxidases etc are only quite efficient. Another method involves the formation of Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) via the process of NETosis which are lattices which are formed from neutrophil DNA/chromatin entangled with antimicrobial proteins (Yost et al 2009). Neutrophils are known to mediate the hike in those proteins that are known to mediate quick apoptosis like annexin-V and Fas death receptor (CD95) within the nasopharyngeal fluid. Neutrophil web / cob prevents further spread or it studds the virus within its network thus limiting further infection. DCs form the most potential class of APCs in RSV infection. Conventional DCs (CD11b+) are more important than plasmacytoid DCs (CD11-) and both are mobilized from the systemic circulation to the nasopharyngeal mucosa early during infection. Dendritic cells form an important role because the cytokines secreted from the DCs are known to influence the T cell response. Below the respiratory epithelia as well as brigged between the epithelial cells lie respiratory clade of DCs which encounter incoming RSV and carry them to the nearby lymph nodes. The DCs process the RSV and are known to present them via MHC 2 restriction to T helper cells. NK cells are those innate effector cells that play an important role in viral clearence and disruption of viral spread on account of its cytotoxic ability. Provided there is a high level of chemokines such as macrophage inhibitory peptide – 1 alpha (MIP 1alpha) the natural killer cells get recruited to the lungs. The NK cells can be detected in peak levels 3-4 days post infection. Prior DC stimulation is necessary to recruit NK from the circulation efficiently. NK cells are known to kill the virus infected cells by the general NK mechanism as well as it also releases IFN gamma which activates the macrophages to kill the virus. Eosinophil activation has also been shown to be effective in controlling RSV infection. Certain special antiviral proteins like those of cathelicidin (LL37) form an ancient arm of innate immunity that inhibits epithelial cell infection. Certain surfactant proteins like SP-A and SP-B bind directly to the F protein of the RSV and contributes to viral clearence; these are actually seen as superficial mechanisms that reduce viral load.

b) Adaptive immunity

Humoral immunity

RSV infection leads to the synthesis of antibodies against most of the viral antigens including F, G, M2 and P proteins but those antibodies that are induced against the 2 major surface glycoproteins F and G are upmore promising and prominent. Antibody production involves help from the T helper cells. Passive antibody transfer has been increasingly promising, and it has also been shown to reduce the risk of patients and also shown to reduce the risk rates. Therapeutic delivery of antibody such as palvizumab is good as it may be noted that on account of natural infection the titres of antibody that are generated are not worth comparing to the former. Antibody’s function either by directly causing neutralisation of the virus via cross linking its reactive sites or indirectly resulting in opsonisation. IgA as well as IgG has been involved in protecting the upper respiratory tract but when it comes to the lower only IgG levels are good to prevent infection. The antibody levels must be held high in order to prevent the subsequent infections with RSV. It may be noted that the levels of antibody secreting plasma cells reduce in the upper respiratory area given that the period of acute infection is over (Singleton et al, 2003). The primary antibody responses are induced within those lymph nodes that lie close to the respiratory area and those of which receive its draining. These lymph nodes possess marginal Zonal B cells which are specialized to encounter viral epitopes via the B cell immunoglobulin receptor. During this time the naïve T cells of the lymph nodes which are unprimed get primed via the encounter with those DCs that have migrated to the lymph nodes from the respiratory area. Further pertaining to the action from critical cytokines such as IL-6 and other costimulatory receptor engagement those naïve T cells modify to RSV directed follicular helper T cells. These cells are responsible for inducing the RSV B cell affinity maturation and secretion of antibodies.

Cell mediated Immune Response (CMIR)

The cellular part of the immune system plays a pivotal role in the control of RSV infections. It may be noted that without the help of the T cell response the primary RSV infection can never be controlled. The acute infection marks the beginning of reduction in CD8+(cytotoxic), CD4+(helper), CD3+ and gamma – Delta T cells. The role of the CD8+ cells or the killer T lymphocytes is highly important as it is the one that prevents the RSV spread from its primary infected foci via catalysing the infected host cell lysis. CD8+ cells either directly kill the cell by the help of pore forming perforins and release of proteases like granzymes into the cell or it does the same via upregulation of the Fas ligand molecules on the cell surface (Braciale et al, 2012). The virus fails to get destroyed and high levels of viral shedding is seen in those children who possess defective T cell responses (Fishaut et al, 1980; Hall et al, 1986). RSV has low ability to induce both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells when compared to Influenza virus. T helper cells are responsible for the generation of high affinity B cell antibodies to RSV. Also, the helper is important later for developing T cell memory. The T cells have been accounted to recognize N, F, M and M2 proteins. RSV F protein polarized both the helper and killer T cells towards a Th1 type immune response whereas RSV G protein leads to the Th2 biased response polarization. CD8+ T cells are highly protective, responsible for the mediation of viral clearance and favorable disease resolution. RSV LRTI associated infant examination of BAL fluid showed the CD8+ type to predominate when compared to CD4+. In case of acute infection, the TRAIL receptor expression by those circulating CD4+ and CD8+ increases. The RSV induces the CD8+ cells to express the HLA – DR+, granzyme B+, and CD38+effector phenotype.

T- helper 1 and T- helper 2 responses to RSV infection.

The Th1 response follows that of the pro-inflammatory profile, and it is inevitable for the generation of CMI which is required in suppression of the viruses and other intracellular pathogenic entities. Cytokines IL-1, IL-2, IL-12, IL-18, TNF alpha are prerequisites in the development of a progressive response of the Th-1 type. Once these cytokines are released there is Interferon gamma production by T helper cells. Provided that the macrophage releases a greater amount of the IL-12, there occurs enhanced production of IFN – gamma by T helper which results in favoring of the Th-1 differentiation. Th1 response specific markers like TNF receptor 2, IFN- gamma, soluble receptor of IL-2 is highly seen in large quantities in blood circulation in patients associated with RSV LRTI. When it comes to the nasal mucosa and the lung there is an elevation in IFN gamma levels. TNF alpha levels remain high in the acute phase but decline rapidly in recovery. The Th2 response is responsible for the RSV antibody generation and is also known as a builder of eosinophil mediated responses.

c) Exploring RSV immune response inhibition potential

Impairment of MAVS through NS2 protein of RSV mediated through binding of the protein to RIG-1

NS-1 mediated disruption of IRF3- IFN beta association.

Type 1 Interferon production inhibition by the action of RSV G and RSV N protein

Soluble RSV G (secreted) which limits the concentration of antibodies to the RSV.

Disruption of immune synapse formation

Reductory function of the chemokine on account of interaction between the secreted G protein and pDCs.

Degradation of STAT2 by both NS1 and NS2.

7. Epidemiology

It is highly significant to know the epidemiology particularly that at the molecular level for developing effective vaccines and undertaking the various control and containment strategies. Based on the reactivity to monoclonal antibodies HRSV has been separated into 2 antigenic subgroups A and B of a single antigenic type (Collins et al 2006). The viral genome is highly prone to amino acid sequence changes that occur in the variable regions of the G protein which occurs as a result of pressure from the immune system (Botosso et al, 2009; Canned & Pringle, 1992; Zlateva et al, 2005). The group A and B subgroups are further differentiated to clades which are then divided into multiple strains based on hypervariable region associated nucleotides sequence (Cane, 2001; Peter et al, 2000). On examining the phylogeny on the G gene, group A was divided into 7 clades from G1 to G7 and group B was subdivided into 4 clades. A study that was conducted for surveillance of RSV human association showed HRSV to be detected in the respiratory tract of 23.3% of the hospitalised. RSV was the estimated cause of an average of 17,358 deaths in the elderly US senior citizen population. The viral epidemics in those of the developed countries last for 4-5 months extending from November to late February.During this time about 0.2 million children get hospitalised out of which nearly 10-7000 die. RSV infections are known to vary with geographical differences and mean average temperature rates. RSV hikes in temperate zones in winter season (commonly called RSV cold epidemic) with the temperates dropping upto 2-6°C and in tropical areas with hotter climates (RSV hot / rainy epidemics), 24-30°C is the most favourable temperature (months from July to September highly productive) for community spread of RSV. In the Northern hemisphere of the US, RSV predominantly circulates between November and March (Dawson and Caswell, 2011). HRSV study in Kenya detected a superior 43% of the of the hospitalized children to contain the virus. Outbreaks often develop from schools and daycares. RSV viral strain variability is the most important factor that gives the virus the ability to cause outbreaks annually. All the major continents undergo a periodic transition with respect to the RSV group that dominates however group A RSV are most detected. The RSV group A was the more predominant in seven out of the total nine outbreaks that occurred in Germany. Several other countries also reported RSV A to predominate. In case of Belgium RSV A dominated in 2 RSV seasons which was followed by one RSV B dominated annum. An Indian study reported group A to dominate for 3 progressive years. In Saudi Arabia, fewer reports of RSV infection have been known to occur sporadically in districts like Riyadh, Al – Quassim and Abha (Jamjoom et al, 1993; Bakir et al, 1998). A study in Iran pointed out that out of the total RSV infections 67% belonged to group A and 33% to group B. Evidence from Combodia based on a 5 year study showed the seasonal nature of RSV to extend from July to November with group B to be predominant. A conclusion that is generally made suggests at a particular time infections with a particular subgroup of virus is known to occur throughout the world. Given the fact that certain areas have an endemic circulation of RSV, when the virus attains any kind of mutation which leads to the development of a new strain it rapidly spreads throughout the world ie, a mutated new strain of RSV has ability to cause Pandemics. In Australia children under 4 exhibits the largest fraction of the total RSV winter epidemic cases (Mullins et al, 2003). Great Britan (= London) experience monophasic / annual epidemics whereas in countries like Switzerland, Sweden, Croatia, Germany and Finland a 2-year cycle of RSV which repeats itself at every 23-25 months are noted.

8. Diagnosis

Lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA)/Rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs). This is a rapid test that uses a strip of paper to detect RSV antigens in a sample of mucus or saliva. LFIA tests are easy to use and can give results in as little as 15 minutes.

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). These tests use molecular biology techniques to amplify the genetic material of RSV in a sample (from mucus or saliva). NAATs are very sensitive and can detect RSV even when levels are low. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). This test is used to detect the genetic material of RSV in a sample of mucus or saliva. RT-PCR is a very sensitive test, and it can detect RSV even when levels are low. However, RT-PCR can take several hours to get results, and it is more expensive than other tests.

Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA). DFA is a test that uses fluorescent antibodies to detect RSV in a sample of mucus or saliva. DFA is a rapid test, and results are available in about 30 minutes. However, DFA is not as sensitive as RT-PCR. RSV antigens are detected in a sample of mucus from the nose or throat.

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA): This is a more sensitive test than DFA testing, but it is also more time-consuming. IFA testing can be used to detect RSV antigens in a sample of lung tissue or cells.

TEM: In TEM, a sample of mucus from the nose or throat is placed on a grid and then examined under a transmission electron microscope. RSV virions are typically about 130 nm in diameter, so they can be visualized using TEM. TEM can be used to confirm diagnosis but is not a routine test.

Biosensors. These devices use biological molecules to detect RSV in a sample. Biosensors are still under development, but they have the potential to be very sensitive and easy to use.

Cell culture. Cell culture is the most sensitive test for RSV infection. This test involves growing RSV derived from a nasal aspirate or nasopharyngeal swab in a laboratory culture. The virus is then identified by its ability to infect cells and cause characteristic changes. Cell culture is the gold standard for RSV diagnosis, but it can take several days to get results.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This test is used to detect the presence of RSV antibodies in the blood. RSV-specific IgM antibodies. These antibodies are produced early in the course of RSV infection, and they can be detected in the blood for several weeks. The presence of RSV-specific IgM antibodies is a good indication of recent RSV infection. RSV-specific IgG antibodies. These antibodies are produced later during RSV infection, and they can be detected in the blood for many years. The presence of RSV-specific IgG antibodies indicates that the person has been infected with RSV in the past.

-

Imaging tests: In some cases, the doctor may order imaging tests to look for complications of RSV, such as pneumonia or bronchiolitis. These tests can include:

- ○

Chest X-ray: This test can show inflammation of the lungs.

- ○

CT scan: This test can provide more detailed images of the lungs.

9. Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Complications

a) Symptoms

Most common symptoms of RSV infection during the early period include rhinitis, low-grade fever, mild cough, nasal congestion etc. The cough if associated has high chances to progress into what is commonly referred to as the barking type wherein vocal cord swelling is notable. The fever in the following days may progress into a high grade one reaching upto 104° Farenheit together with the development of any one or more of the following breathing complications; fast breathing or tachypnea, chest wall hyper retraction, widening of nasal orifices during expiration commonly referred to as the nasal flaring together with rales or crepitations and polypnea/ hike in breathing rate is common (Freymuth et al 2001; Rietveld, 2003) . During the next days to come the patient exhibits poor drinking, hyper irritability, lethargy, head swirling, nausea respiratory distress and other symptoms. The property of RSV to induce wheezing among those infected is significant because of a peculiar high-pitched noise resembling a whistle that gets produced during expiration. Certain patients are known to develop cyanosis which is marked by the development of bluish tinge around the corner of the mouth, lips and fingernails. For those who have had a premature birth (and those diagnosed later with RSV bronchiolitis) often the development of apnea (or total stopping of breathing at certain intervals) is a common symptom (Ralston and Hill, 2009).

b) Risk factors / predisposition to RSV Disease

Overcrowded areas harbouring infected subjects.

Children with premature births

Those with weakened immunity or those who have been immunocompromised.

Those with underlying diseases such as Chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congenital heart disease, neuromuscular disease, cystic fibrosis, asthma patients, emphysema afflicted persons and those who have received transplants.

Admission of children to infected day cares, ones with older siblings.

Weaning of babies from breast milk

Maternally smoking.

Children afflicted with Down's syndrome.

c) Risk factors that lead to disease progression into Brochiolitis

Low weight at birth

Atopic dermatitis

Low socioeconomic background

High environmental pollution

Residing at high altitudes

Delivery through cesearean

d) Complications of RSV infection

For those infants with one or several of the above-described risk factors respiratory failure and higher incidence of mortality is common (Boyce et al, 2000; kohlhare, 2003).

Heart related complications are quite common and mostly seen among hospitalised infants with Lower respiratory RSV infection those of which include tachyarrythmia, pericarditis, myocarditis, sinoatrial blockage, complete heart blockage.

Severe otitis media affecting both the ears is quite common in 30% of the people diagnosed with RSV LTRI (Patel et al, 2011; Pettgrew et al, 2011; Kristganson et al, 2010).

Severe muscle lethargy and encephalopathies characterized by frequent seizures is quite a rare complication of RSV hyper infection (Nakamura et al,2012).

Other long run associated syndromes and sequelae like pulmonary malfunctions and mucosal non responsiveness. (Bont and Ramilo, 2011).

10. Management of RSV

a) Non-clinical management

Rest: Getting plenty of rest is important for helping your body fight off the virus.

Over-the-counter pain relievers: Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen, can help relieve fever and pain.

Humidifier or saline nasal spray: A humidifier or saline nasal spray can help loosen mucus and make it easier to breathe.

Antibiotics: Antibiotics are not effective against RSV, but they may be prescribed if there is a concern about a secondary bacterial infection.

Use of a cool-mist humidifier: This can help loosen mucus and make it easier to breathe.

Suction of the nose: If the person is having trouble in breathing, you may need to suction their nose to remove mucus.

Elevation of head: This can help reduce congestion and make it easier to breathe.

Prevent dehydration: Encourage the patient to drink plenty of fluids. This will help prevent dehydration.

b) Clinical drugs and modulators.

Ribavirin: This is an antiviral medication that can be given to hospitalized infants and children with severe RSV infection. Ribavirin can help shorten the length of hospitalization and improve the outcome of RSV infection. Ribavirin is given as an inhaled medication or a IV infusion.

Bronchodilators: These medications can help open the airways and make it easier to breathe. Bronchodilators can be given as an oral medication, a nebulizer treatment, or an inhaler.

Oxygen therapy: This may be needed for infants and children with severe RSV infection who are having difficulty breathing. Oxygen therapy can help improve the oxygen levels in the blood.

c) Vaccines

RSV palivizumab (Synagis): RSV palivizumab was the first RSV vaccine approved in the United States This is a humanized monoclonal antibody that is given as a monthly injection during the RSV season. RSV palivizumab can help reduce the risk of serious RSV illness, such as pneumonia but often causes side effects such as fever and rash.

Nirsevimab (Benexa-flu): It is a long-acting monoclonal antibody that is designed to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in infants. Nirsevimab works by binding to the RSV fusion protein, which is essential for the virus to enter cells. This prevents the virus from infecting cells and causing disease.Nirsevimab is administered as a single subcutaneous injection. It is given to infants at least 6 weeks of age and within 12 weeks of their first RSV season. Nirsevimab has been shown to be effective in preventing RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in infants. Nirsevimab is currently approved for use in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Canada, and by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Abrysvo (RSVpreF): Abrysvo is a newer RSV vaccine that was approved in 2023. It is not yet as widely available as RSV palivizumab This is a bivalent RSV prefusion F (RSVpreF) vaccine that is given as a single injection during the RSV season. Abrysvo can help reduce the risk of serious RSV illness, such as pneumonia.

Mosunetuzumab. Mosunetuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that is being developed for the prevention of RSV infection in infants. It works by binding to the RSV fusion protein and preventing the virus from entering cells. The vaccine is currently in Phase 2 clinical trials.