1. Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is an enveloped RNA virus that primarily infects the respiratory tract. It can cause symptoms ranging from mild colds to more severe lower respiratory tract infections such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia, with severe cases particularly affecting infants, young children, and older adults [

1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that RSV causes 33 million lower respiratory tract infections, 3 million hospitalizations, and approximately 59,600 deaths annually among children aged ≤5 years [

2]. Despite its clinical importance, RSV surveillance and reporting remain inconsistent across Europe, with several countries – including Switzerland – yet to designate RSV as a notifiable disease [

3].

In Switzerland, RSV surveillance exists but has traditionally focused on young children, who are known to experience high infection rates and hospitalizations [

1,

4]. However, this pediatric-centric approach may overlook a substantial burden of disease in adults, particularly older adults [

5,

6,

7]. Systematic reviews suggest that RSV hospitalizations in adults may be underreported by factors ranging from 1.5 to over 20 [

5,

6,

7]. Evidence suggests that there is a significant underestimation of adult RSV burden due to factors such as low awareness and testing rates, reduced assay sensitivity in adults, and lack of standardized case definitions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Adult patients often present later in the disease course, when the virus is already in the lower airways, making standard upper respiratory swabs more likely to yield false negative results [

5,

9]. Additionally, lower viral loads and shorter viral shedding in adults complicate detection [

10].

A growing body of literature highlights the clinical relevance of RSV in adult and immunocompromised populations. RSV is increasingly recognized as an important cause of medically attended acute respiratory illness in multimorbid patients [

11]. Comorbidities such as hematologic malignancies, chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other chronic lung or cardiovascular conditions can exacerbate RSV disease and increase the risk of severe outcomes [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Immunocompromised individuals, including those with cancer or transplant recipients, appear to be particularly vulnerable, with elevated hospitalization and mortality rates. These findings are especially relevant in the Swiss context, where chronic comorbidities such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and chronic lung disease are common in older adults [

17].

A recent Swiss study by Stucki et al. (2024) used national hospital data from 2003 to 2021 to evaluate RSV-associated hospitalizations, focusing on RSV infection as a primary diagnosis, mainly in children. While confirming the expected high RSV burden in infants, the study likely underestimates the true adult burden, as it excluded cases with RSV infection as a secondary diagnosis, which is frequently the case in older and multimorbid patients [

18].

To address these gaps, our study aimed to assess RSV-related hospitalizations across all age groups in Switzerland using data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) for the period 2017–2023. This more recent timeframe reflects increased awareness and improved RSV testing, particularly in adults. By including cases with RSV infection coded as either primary or secondary diagnosis, our analysis provides a more comprehensive picture of RSV-associated morbidity. Special emphasis is placed on older adults, in whom RSV infection is often overlooked despite a disproportionate burden of severe outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology

Between 2017 and 2023, a total of 35,489 RSV-related hospitalizations were documented in Switzerland, corresponding to an average of approximately 5,100 hospitalizations per year.

Supplementary Figure S1 presents the annual absolute numbers, highlighting age-specific differences across years. A clear year-to-year variation was observed, most notably during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, hospitalization numbers dropped well below average to 3,025 cases. A marked rebound followed in 2021, driven primarily by a pronounced wave in children aged 0–9 years, with 4,505 hospitalizations compared to 2,700–3,500 in the pre-pandemic years (2017–2019). In contrast, RSV-related hospitalizations among older adults did not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2022. Among individuals aged ≥80 years, case numbers rose from <100 in 2021 to approximately 1,100 in 2022 and 2023, exceeding the pre-pandemic range of 600–900. In addition to pandemic-associated fluctuations, an overall increasing trend in RSV-related hospitalizations was observed across the study period (

Supplementary Figure S1). This likely reflects greater clinical awareness and more widespread diagnostic testing in adult populations, particularly among older individuals with comorbidities.

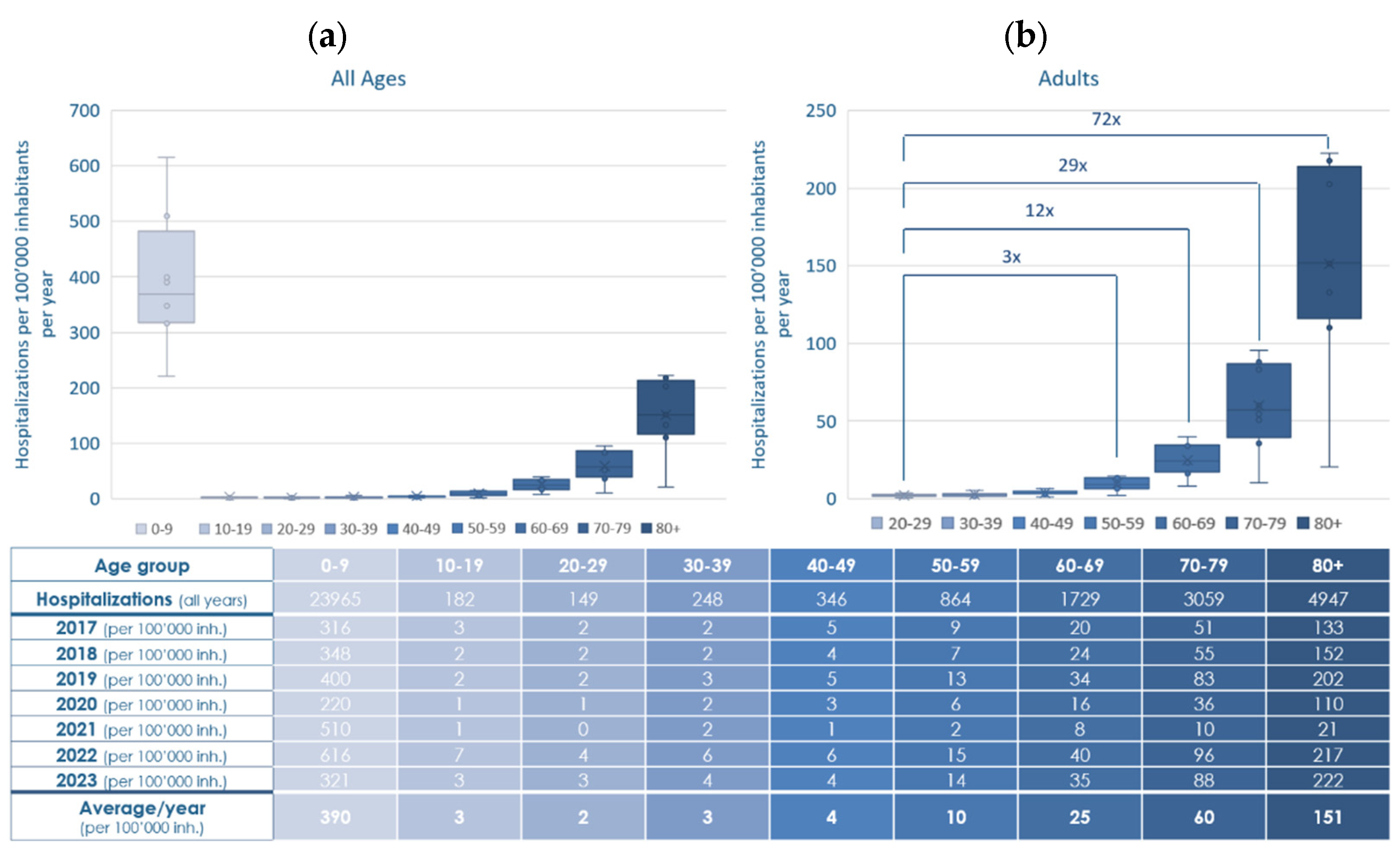

Figure 1 (

a) summarizes the incidence of RSV-related hospitalizations 2017–2023, stratified by age group in 10-year increments and expressed per 100,000 inhabitants.

Figure 1.

Annual and average incidence of RSV-related hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants, stratified by age group in 10-year increments in Switzerland, 2017-2023. (a) All ages, including children, adolescents and adults; (b) Adults only, fold-change in hospitalization rates per adult age group compared to the 20–29-year reference group. Whiskers: minimum and maximum, box: interquartile range, ––: median, ×: mean, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, inh.: inhabitants.

Figure 1.

Annual and average incidence of RSV-related hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants, stratified by age group in 10-year increments in Switzerland, 2017-2023. (a) All ages, including children, adolescents and adults; (b) Adults only, fold-change in hospitalization rates per adult age group compared to the 20–29-year reference group. Whiskers: minimum and maximum, box: interquartile range, ––: median, ×: mean, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, inh.: inhabitants.

The highest hospitalization incidence by far was observed in children aged 0–9 years, with an annual mean of 390 cases per 100,000 population. Hospitalization incidence declined sharply in the older children and young adults (aged 10–49 years), remaining ≤ 4 cases per 100,000 annually. From age 50 onward, incidence increased steadily with rising age from 10 (ages 50–59) to 25 (ages 60–69) and 60 (ages 70–79), peaking at 151 in individuals aged ≥80 years per 100,000 population.

Comparison among adults only (

Figure 1 (

b)) shows a marked increase of hospitalizations from the age of 50 onward with rates 3- to 72-fold higher than in young adults (20–29 years). These findings highlight the substantial and age-dependent rise in RSV-related hospitalizations across the adult population.

3.2. Outcome

3.2.1. Length of Hospital Stay of RSV-Related Hospitalizations 2017–2023

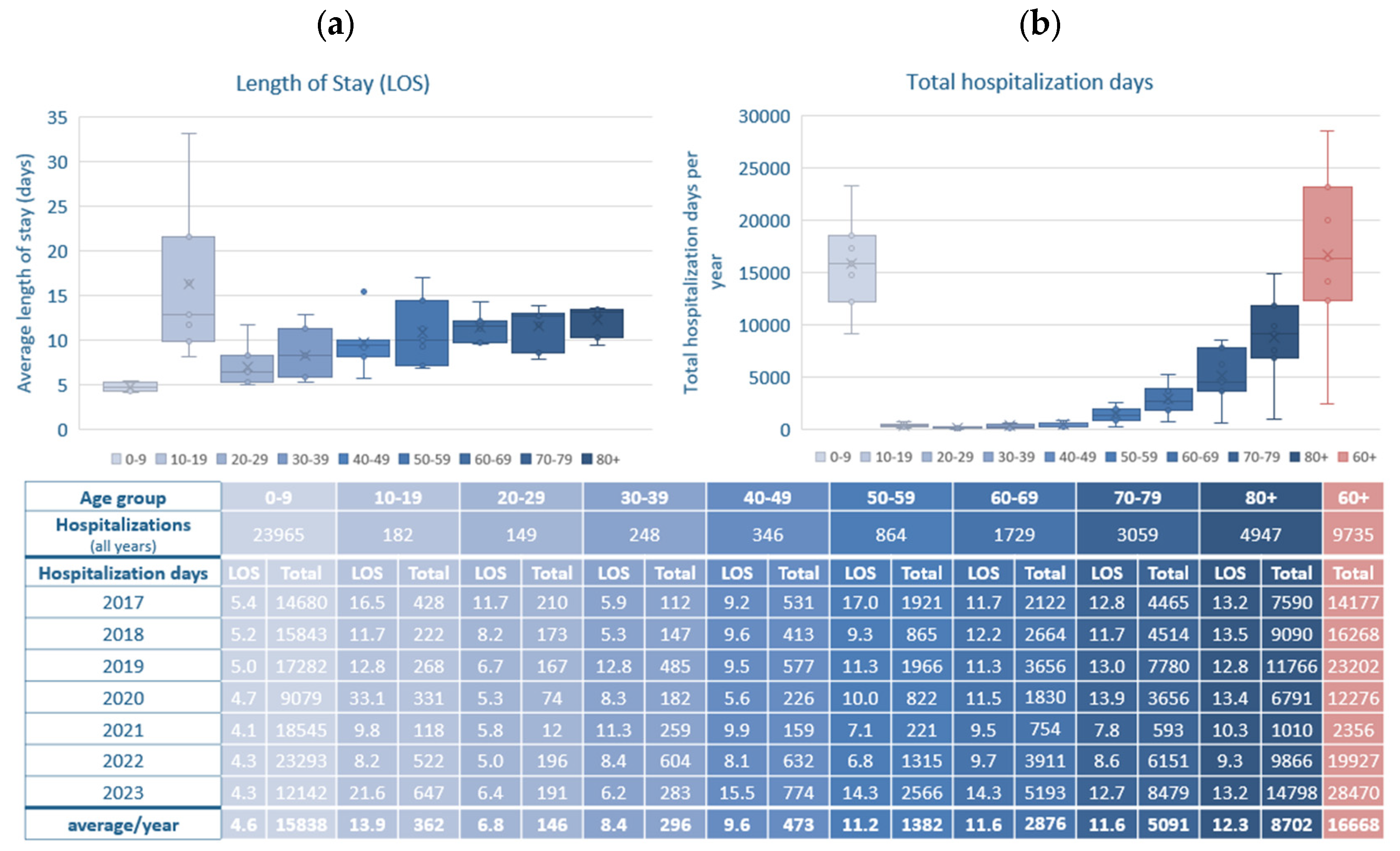

Figure 2 (

a) presents the average LOS for RSV-related hospitalizations in Switzerland stratified by age group, based on data from 2017 to 2023, showing notable differences between age groups. Children aged 0–9 years had the shortest hospital stays, with an overall average LOS of 4.6 days. Among adults aged 20-49 years LOS increased moderately with age (6.8 days in the 20-29 year group, 8.4 days in the 30-39 year group, 9.6 days in the 40-49 years group). In contrast, LOS was substantially longer in older adults, increasing with age: 11.2 days (50-59 years), 11.6 days (60-69 years and 70-79 years) and 12.3 days (≥80 years), thus a 2.4- to 2.7-fold increase compared to young children.

Figure 2.

Length of hospital stay (LOS) for RSV-related hospitalizations, stratified by age group in 10-year increments in Switzerland, 2017-2023. (a) Average mean LOS in days is shown for each age group; (b) Total hospitalization days (multiplication of LOS with number of hospitalizations) for RSV-related hospitalizations per age group and year, as well as the average over the years 2017–2023. Statistical significance assessed by t-test. Whiskers: minimum and maximum, box: interquartile range, ––: median, ×: mean, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, LOS: length of hospital stay.

Figure 2.

Length of hospital stay (LOS) for RSV-related hospitalizations, stratified by age group in 10-year increments in Switzerland, 2017-2023. (a) Average mean LOS in days is shown for each age group; (b) Total hospitalization days (multiplication of LOS with number of hospitalizations) for RSV-related hospitalizations per age group and year, as well as the average over the years 2017–2023. Statistical significance assessed by t-test. Whiskers: minimum and maximum, box: interquartile range, ––: median, ×: mean, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, LOS: length of hospital stay.

Interestingly, the longest average LOS across all age groups was observed in adolescents aged 10–19 years, with an overall average of 13.9 days, exceeding even that of the oldest patients. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution: adolescents represented the smallest number of hospitalizations overall, resulting in considerable year-to-year variation. The disproportionately long LOS may reflect the disproportionate severity in a small number of complex cases in this age group.

Figure 2 (

b) illustrates the total hospitalization days per age group, providing insight into the cumulative strain on hospital resources across age cohorts. Between 2017 and 2023, the highest total number of hospitalization days was consistently attributed to children aged 0–9 years, with an average of 15,838 days per year. However, older adults (aged ≥60 years) collectively accounted for an even larger burden, averaging 16,668 total hospitalization days per year. Within this group, adults aged ≥80 years alone contributed over 8,700 hospitalization days annually, exceeding all other adult age bands. These data emphasize that although children account for the highest number of RSV hospitalizations, older adults—due to longer LOS—represent a major share of total inpatient burden.

3.2.2. RSV-Related Hospitalizations Admitted to Intensive Care Units 2017–2023

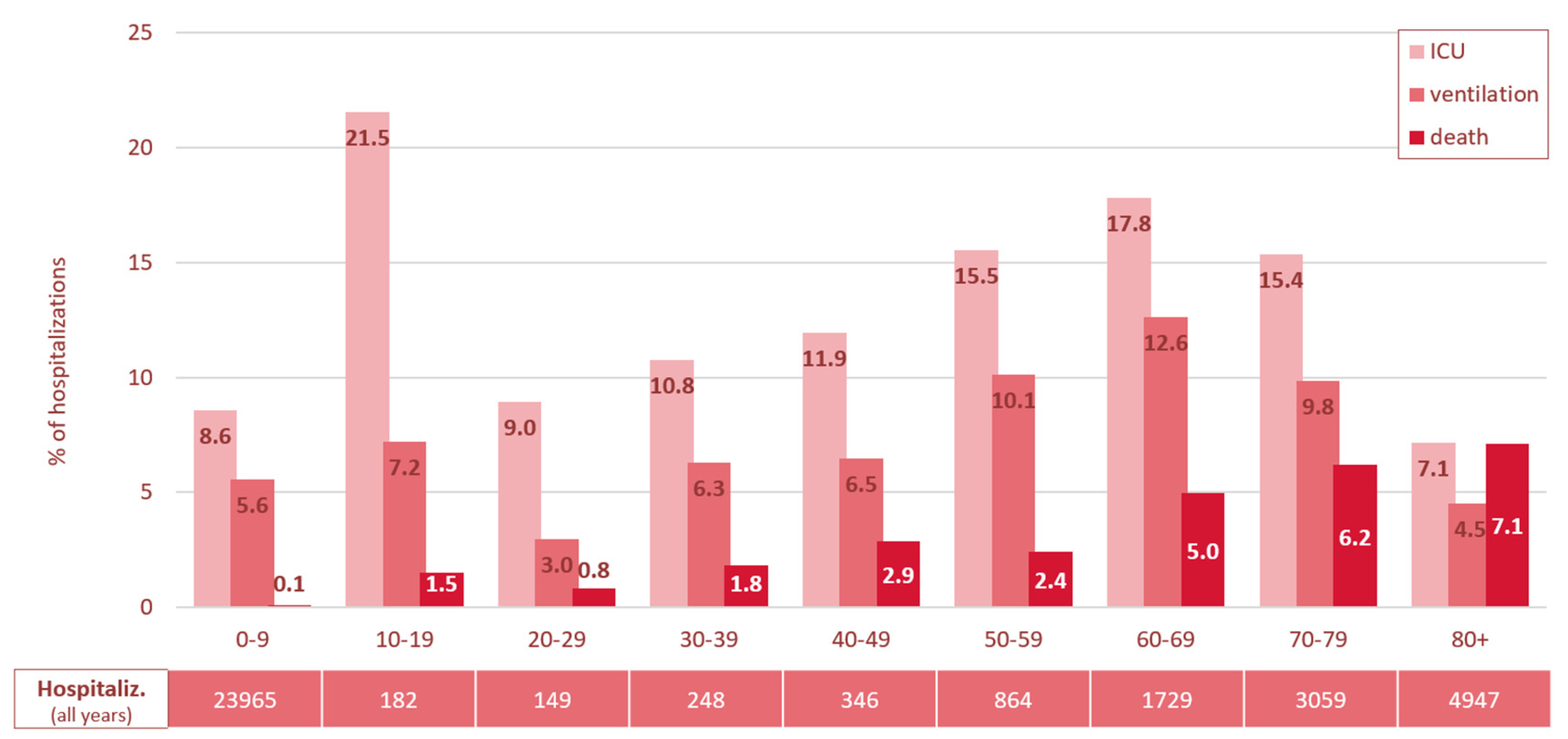

Between 2017 and 2023, a total of 3,441 ICU admissions were recorded in RSV-related hospitalizations in Switzerland, showing a distinct age-related pattern (

Supplementary Figure S2). In terms of absolute numbers, children aged 0–9 years accounted for the highest ICU burden, with 166 to 473 admissions annually—making this group the largest contributor to total ICU admissions across all age groups. However, when considered in relative terms, their overall ICU admission rate was comparatively low at 8.6% of RSV-related hospitalizations (

Figure 3,

Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Average rate of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and in-hospital mortality in % of overall RSV-related hospitalizations in Switzerland, 2017–2023, stratified by age group in 10-year increments. ICU: intensive care unit admission, Hospitaliz.: Hospitalizations, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 3.

Average rate of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and in-hospital mortality in % of overall RSV-related hospitalizations in Switzerland, 2017–2023, stratified by age group in 10-year increments. ICU: intensive care unit admission, Hospitaliz.: Hospitalizations, RSV: respiratory syncytial virus.

In contrast, adolescents aged 10–19 years showed the highest overall ICU admission rate (21.5%), despite having the lowest number of RSV-related hospitalizations (between 10 and 64 cases per year) compared to the other age groups.

Adults aged 20-39 years exhibited moderate ICU admission rates, ranging from 9-10.8%, among older adults ICU admission rates increased progressively with advancing age (40-49 years 11.9%, 50-59 years 15.5%, 60-69 years 17.8%), before declining again in those aged 70-79 years (15.4%) and dropping further to the lowest rate of 7.1% in individuals aged 80 years and older.

In summary, the burden of ICU admissions in RSV-related hospitalizations falls primarily on young children (0–9 years) in absolute numbers and on older adults (≥60 years) in relative severity. Adolescents exhibited the highest ICU admission rate.

3.2.3. RSV-Related Hospitalizations Requiring Mechanical Ventilation 2017–2023

The need for mechanical ventilation largely paralleled ICU admission trends across most age groups (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Figures S2, S4). Children aged 0–9 years accounted for 60% of the overall ventilated cases in the seven-year period (1,317 / 2,179), but their average ventilation rate was comparatively low at 5.6%. Age groups between 10 and 49 years showed consistently low to moderate ventilation rates, ranging between 3.0% and 7.2%. For adults aged 50 and older, ventilation rates increased with age, peaking in the 60–69-year age group at 12.6%. In the age groups 70+, the rates declined to 9.8% in the 70–79-year group and further to 4.5% in individuals aged 80 and older.

In summary, young children (aged 0–9 years) and adults aged 60–79 years accounted for the highest burden of ventilation in absolute numbers, while adults between 50 and 79 had the highest ventilation rates. Lowest absolute and relative numbers of mechanical ventilation were observed in the youngest (<30 years) and oldest (≥80 years) adults.

3.2.4. In-Hospital Mortality in RSV-Related Hospitalizations 2017–2023

Overall, 656 RSV-related hospitalizations resulted in in-hospital death (1.8%). While the in-hospital mortality rates remained low in children and younger adults up to 39 years (< 2%), they rose progressively with age: between 2.4-2.9% in those aged 40-59 years, exceeding 5% from age 60 onward, and peaking at 7.1% in the oldest age group (≥80 years) (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Figure S5).

In summary, the highest mortality rates occurred in individuals aged 60 and older, increasing progressively with age, while younger age groups, particularly those under 40, were least affected. Overall, the data reveal a clear age-related gradient in RSV disease severity: younger children (0–9 years) present with high hospitalization incidence but relatively mild clinical courses, whereas older adults, despite lower absolute numbers, face a disproportionately higher risk of ICU admission, need for mechanical ventilation, and in-hospital death.

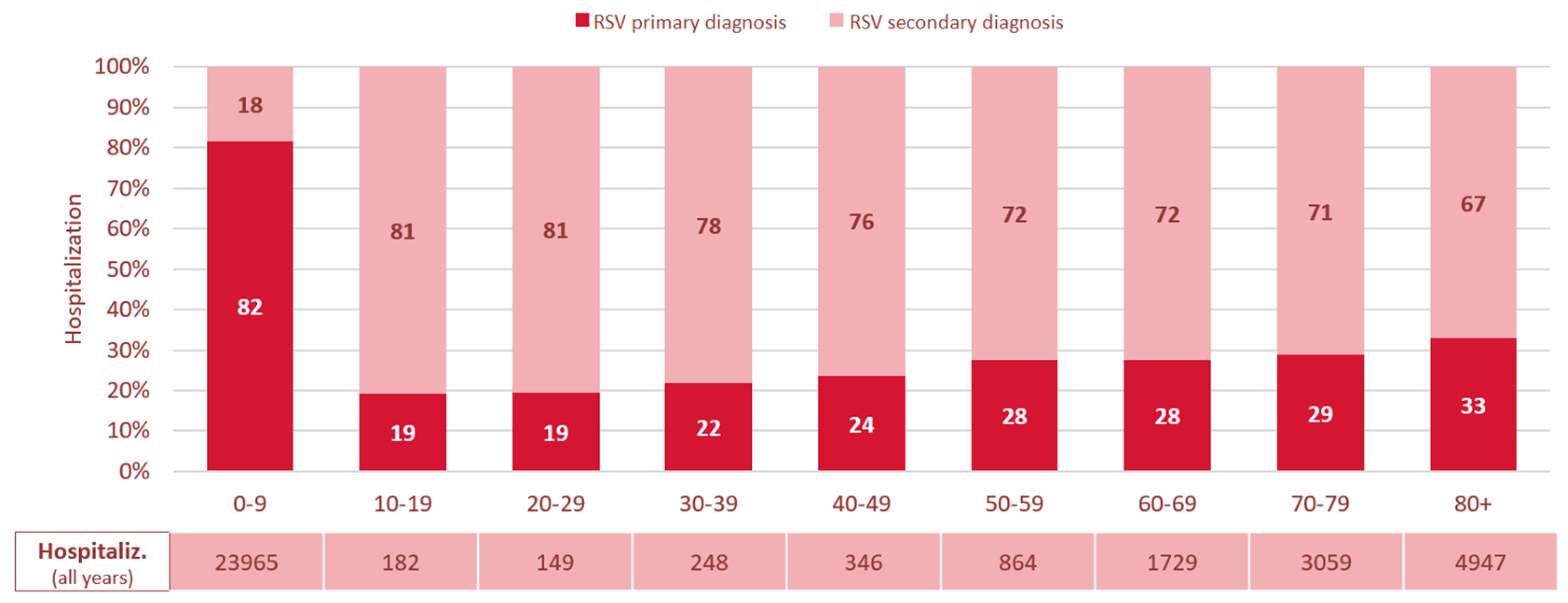

3.3. RSV Infection as Primary vs. Secondary Diagnosis and Additionally Coded Diagnoses

A clear age-related pattern was also observed in the coding of RSV infection as a primary versus secondary diagnosis (

Figure 4). In children aged 0–9 years, RSV infection was recorded as the primary diagnosis in 82% of cases, suggesting it was the main reason for hospitalization in this group. In contrast, among individuals aged 10 years and older, RSV was coded as a secondary diagnosis in the majority of the cases. In adolescents aged 10–19 years, in 81% of RSV-related hospitalizations RSV infection was coded as a secondary diagnosis. From this age group onward, the proportion of cases with RSV infection coded as the primary diagnosis gradually increased, reaching 33% in those aged ≥80 years, while the proportion of RSV infection as a secondary diagnosis declined accordingly (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proportion of RSV infection coded as primary vs. secondary diagnosis in % of overall RSV-related hospitalizations in Switzerland, 2017–2023, stratified by age group in 10-year increments. RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, Hospitaliz.: Hospitalizations.

Figure 4.

Proportion of RSV infection coded as primary vs. secondary diagnosis in % of overall RSV-related hospitalizations in Switzerland, 2017–2023, stratified by age group in 10-year increments. RSV: respiratory syncytial virus, Hospitaliz.: Hospitalizations.

To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the disease burden and associated clinical context, we extended this analysis to examine the most frequent diagnosis codes recorded alongside RSV-related diagnoses, regardless of whether RSV infection was coded as the primary or secondary diagnosis. This approach allows for a more nuanced view of the underlying or concurrent medical conditions across age groups. The 10 most common additionally coded diagnoses are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

In children aged 0–9 years, additionally coded diagnoses were predominantly acute respiratory or infection-related conditions. The most common were respiratory failure (J96, 44.4%), SARS-CoV-2 testing procedures (U99, 31.1%), and feeding/fluid-related symptoms (R63, 24.5%). Diagnoses such as acute bronchiolitis (J21), acute bronchitis (J20), otitis media (H66, H65), and volume depletion (E86) were also frequently observed. These findings reflect the acute nature of RSV-related hospitalizations in this age group and a tendency towards broader diagnostic coding in pediatric care.

In adolescents aged 10–19 years, additionally coded diagnoses were more heterogeneous. While SARS-CoV-2 testing procedures (U99, 9.3%), and respiratory failure (J96, 7.7%) remained common, several chronic and severe conditions were also frequent, including asthma (J45, 8.2%), epilepsy (G40, 6.6%), lymphoid leukemia (C91, 2.7%), and post-transplant status (Z94, 2.7%). The frequent occurrence of hematologic malignancies and transplant-associated diagnoses underscores the vulnerability of affected patients, a small but often immunocompromised, patient group.

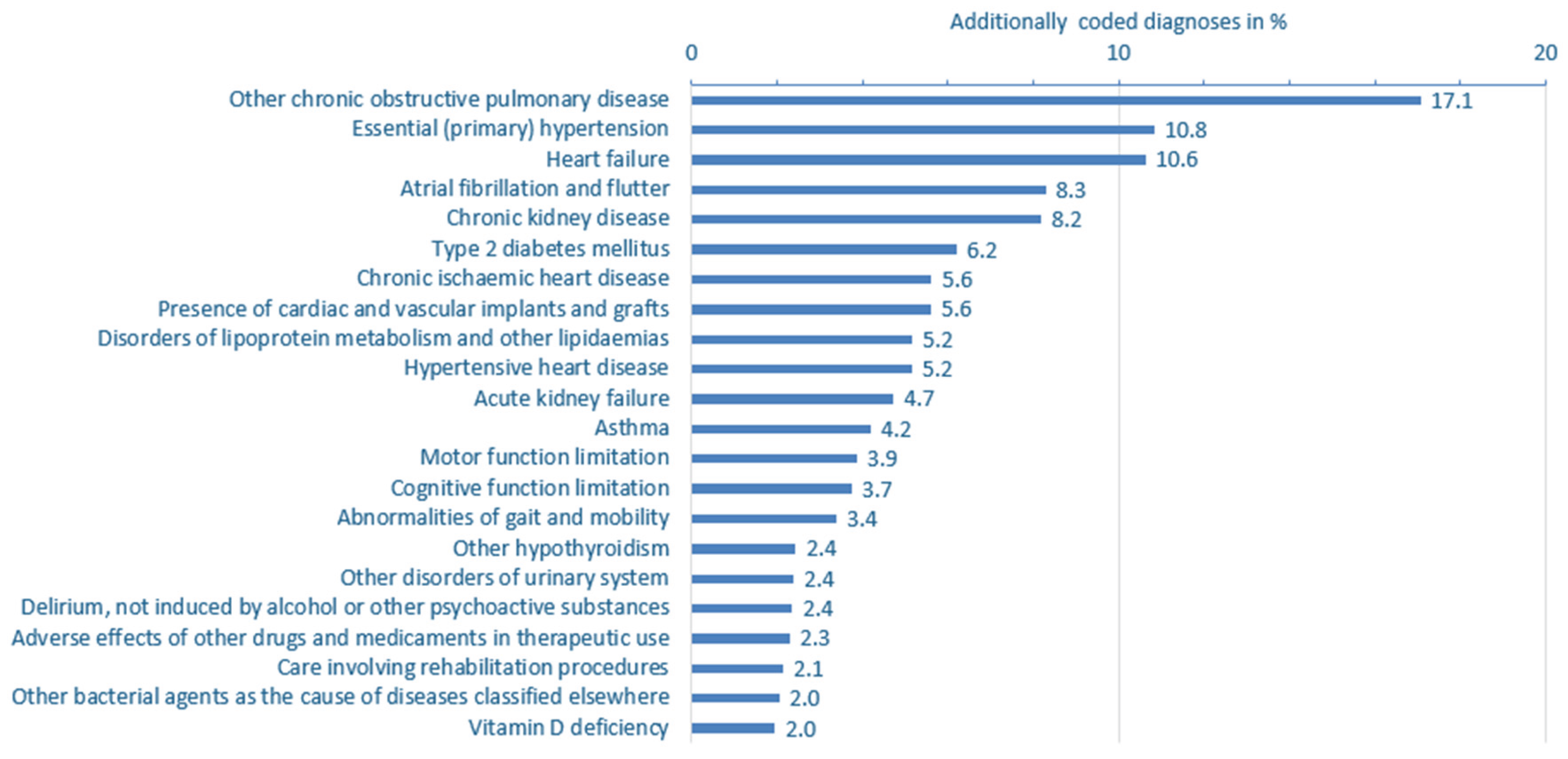

Among adults (aged ≥20 years), comorbidities were predominantly chronic. Among the most frequent additionally coded diagnoses were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J44, 17.1%), primary hypertension (I10, 10.8%), heart failure (I50, 10.6%), atrial fibrillation (I48, 8.3%), and chronic kidney disease (N18, 8.2%). Bacterial pneumonia (J15, 6.5%), and electrolyte disorders (E87, 6.2%) were also common. These patterns highlight the burden of RSV in older, multimorbid populations, where RSV may act as a trigger for decompensation of underlying chronic diseases rather than as the isolated cause of hospitalization.

3.4. Chronic Comorbidities in Patients with RSV-Related Hospitalizations

To better understand the clinical vulnerability of patients affected by RSV infection, we analyzed the prevalence of common chronic comorbidities and severe conditions among all RSV-related hospitalizations—whether RSV was coded as a primary or secondary diagnosis—between 2017 and 2023. The analysis includes chronic diseases or severe conditions observed at a frequency of ≥0.1% in children, and ≥1% in adolescents and adults.

In children aged 0–9 years, chronic comorbidities were rare, documented in fewer than 3% of RSV-related hospitalizations (

Figure S6,

Supplementary Table S2). Most frequently documented were congenital malformations of cardiac septa (Q21, 0.7%), epilepsy (G40, 0.6%), gastroesophageal reflux disease (K21, 0.5%), and asthma (J45, 0.5%). Other notable but even less frequent chronic conditions included Down syndrome (0.3%), congenital malformations (of multiple systems 0.3%, of great arteries 0.3%, of head, face, spine and thorax 0.2%) and cerebral palsy (0.2%), underscoring that a small subset of young children with RSV-related hospitalization had underlying complex medical needs.

Among adolescents aged 10–19 years, chronic conditions were much more prevalent (

Figure S7,

Supplementary Table S2). Asthma (J45, 8.2%) and epilepsy (G40, 6.6%) were the most common, but a variety of severe or immuno-compromising conditions were also observed. These included lymphoid leukemia (C91, 2.7%), post-transplant status (Z94, 2.7%), and cerebral palsy (G80, 2.2%). More rare but noteworthy diagnoses such as aplastic anemia (D61, 1.6%), sickle-cell disease (D57, 1.1%), congenital malformations (Q67, 1.1%, Q87, 1.1%), and Down syndrome (Q90, 1.1%) suggest that adolescents hospitalized with RSV infection frequently had serious underlying chronic disease, potentially contributing to longer hospital stays and high ICU admission rates in this age group.

In adults aged ≥20 years, chronic comorbidities were very common (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2). The most frequently documented diagnoses were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, J44, 17.1% of cases), hypertension (I10 and I11 combined 16.0%), heart failure (I50, 10.6%), atrial fibrillation or flutter (I48, 8.3%), chronic kidney disease (N18, 8.2%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (E11, 6.2%), and asthma (J45, 4.2%) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 5.

Prevalence of additionally coded diagnoses in RSV-related hospitalizations (primary or secondary diagnoses) in adults aged ≥20 years in Switzerland, 2017–2023. Analysis focused on chronic comorbidities, severe or frailty-associated conditions. All conditions shown had a prevalence of ≥2.0% in the study population. See

Supplementary Table S2 for more complete ICD-10 code listings and prevalence across other age groups. RSV: respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of additionally coded diagnoses in RSV-related hospitalizations (primary or secondary diagnoses) in adults aged ≥20 years in Switzerland, 2017–2023. Analysis focused on chronic comorbidities, severe or frailty-associated conditions. All conditions shown had a prevalence of ≥2.0% in the study population. See

Supplementary Table S2 for more complete ICD-10 code listings and prevalence across other age groups. RSV: respiratory syncytial virus.

Beyond these common major comorbidities, a wide range of additionally coded conditions was observed. These encompassed further cardio-metabolic disorders such as chronic respiratory insufficiency, chronic ischemic and hypertensive heart disease, lipid metabolism disorders, hypothyroidism, and kidney dysfunction. Notably, several diagnostic codes pointed to frailty and complex care needs, including cognitive and motor impairments, gait and mobility limitations, delirium (non-substance-related), vitamin D deficiency, and signs of dehydration or volume depletion. Documentation of prior medical interventions, the presence of vascular implants, and the need for rehabilitation further highlighted the functional vulnerability of this patient population. Frequent coding of screening and follow-up procedures—particularly for infectious diseases—underscores the clinical complexity of adults hospitalized with RSV.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that particularly in older adults, RSV infections are typically more severe than influenza, despite occurring less frequently [

20,

21,

22]. Older adults hospitalized with RSV infection tend to experience longer hospital stays, higher rates of ICU admission and mechanical ventilation, and comparable or even higher mortality rates than those hospitalized with influenza [

20,

21,

22].

Our findings demonstrate that RSV-related hospitalizations and outcomes, including LOS, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and in-hospital mortality, vary considerably by age. A bimodal distribution emerged: the highest absolute burden, excluding mortality, occurred in children aged 0–9 years and adults aged ≥60 years. While the highest absolute numbers of hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and mechanical ventilation were most observed in young children, in-hospital mortality was predominantly observed in older adults, increasing progressively with age. This aligns with previous reports of elevated RSV mortality in elderly populations [

23,

24].

We observed a substantial increase in RSV-related hospitalizations from 2017 to 2023, excluding the COVID-19 pandemic years 2020–2021, when non-pharmaceutical interventions suppressed respiratory virus transmission. During lockdowns, RSV prevalence among hospitalized children dropped significantly—a meta-analysis reported a drop from 25% to 5% [

25]. The inclusion of the years 2020–2021 in our dataset likely lowered the average incidence, leading to an underestimation of the actual RSV burden in Switzerland.

When analyzing outcomes relative to the number of hospitalizations per age group, a nuanced pattern emerged. Although ICU admission rates were highest in the very small overall number of adolescent RSV-related hospitalizations, they were consistently elevated in older adults, particularly those aged 60–79 years. This suggests that, although fewer older adults are hospitalized with RSV infection compared to young children, those who are admitted tend to experience more severe disease, as reflected by higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and in-hospital mortality. The longer length of stay (LOS) observed in adults aged >50 years further underscores the increased clinical complexity and severity in this age group. This observation is likely due to older age and increasing number of comorbidities contributing to complications and more severe outcomes.

In contrast, while hospitalization numbers were highest in children under 10 years, their lower ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and very low mortality rates indicate a generally milder disease course in otherwise healthy pediatric patients.

An unexpected finding was the high average length of stay and ICU admission rate observed in adolescents. Although this age group accounted for a relatively small number of RSV-related hospitalizations—averaging around 26 cases per year—the severity of outcomes was notable. While previous research suggests that RSV infections in adolescents typically follow a mild clinical course [

26], severe presentations can occur in this age group, particularly in individuals with underlying health conditions [

27], potentially leading to the indication for intensive care. In our dataset, we observed markedly high numbers of lymphoid malignancies, epilepsy, and post-transplantation status among hospitalized adolescents, possibly explaining the elevated ICU admission rates in this group. Given the low absolute case numbers, small annual fluctuations can lead to large proportional changes, limiting the robustness of age-specific trend interpretation in this population.

In contrast, mortality was almost exclusively observed in patients aged ≥60 years, while those under 40 had very low mortality rates, consistent with the milder disease course in immunocompetent younger adults.

Interestingly, both ICU admission and mechanical ventilation rates declined with increasing age beyond 70, despite rising mortality. This suggests a shift in clinical decision-making, where intensive care is used more selectively in the very elderly—either due to frailty, comorbidity burden, or advance care planning.

A major finding of our study was the high proportion of RSV infection coded as a secondary diagnosis in adults, particularly in those with chronic conditions such as COPD and heart failure frequently listed as the primary diagnosis. This pattern suggests that comorbidities, which are generally more prevalent in older adults, both predispose individuals to a more severe course of RSV infection and may be exacerbated by the infection itself, ultimately contributing to hospitalization.

In contrast to pediatric cases—where RSV infection is typically the sole driver of disease—its role in older adults appears to be more complex, often interacting with underlying respiratory, cardiopulmonary or metabolic conditions and worsening the clinical trajectory [

23,

28,

29,

30]. However, our data do not allow us to determine whether RSV infection was the initial trigger for primary respiratory diagnoses such as pneumonia, or whether it was acquired secondarily during hospitalization. RSV infection is a known cause of COPD exacerbations [

15,

16], and patients with cardiopulmonary conditions have higher rates of RSV-related hospitalizations [

14]. Heart failure, frequently associated with pulmonary congestion, may predispose patients to secondary respiratory complications [

31,

32]. Moreover, chronic heart failure may impair immune function, and consequently increase susceptibility to infections [

33].

Together, these mechanisms likely contribute to the role of RSV infection in the hospitalization of older, multimorbid adults.

Thus, it is plausible that RSV infection plays a central, though under-recognized, role in the clinical deterioration of older adults. This is further supported by the high proportion of secondary RSV diagnoses among all hospitalizations in older age groups, indicating that RSV likely contributed to primary diagnoses such as acute decompensated heart failure and acute COPD exacerbation.

Furthermore, a recent European study reported that among patients hospitalized with a respiratory tract infection who tested positive for RSV, 57.6% were not recorded with an ICD-10 diagnosis for RSV infection during their admission, highlighting the extent of underreporting of RSV-coded hospitalizations [

34].

The increasing prevalence of chronic comorbidities and frailty indicators in our older RSV patient population, together with the rise in RSV infection as a secondary diagnosis, underscore the substantial burden of RSV in this age group. This demonstrates the urgent need for enhanced awareness, improved testing strategies, and preventive approaches—particularly vaccination and risk-adapted clinical management—for older adults.

Limitations

The study has several limitations related to the use of administrative data. First, reliance on ICD-10 coding may lead to underreporting or misclassification of RSV infection cases, especially given variability in testing and documentation practices across hospitals and over time. Patients with confirmed RSV infection may not have been assigned a specific RSV-related ICD-10 code, and coding as a secondary diagnosis further complicates attribution. The use of diagnosis codes may also under-capture frailty and functional decline, which are often undercoded but clinically relevant in older populations.

Second, causality cannot be inferred from the data. It is unclear whether RSV infection was the primary reason for hospitalization or acquired during the hospital stay, particularly in older adults with multiple comorbidities where RSV infection may exacerbate underlying conditions.

Third, outcomes were limited to in-hospital events. Data on post-discharge mortality, functional recovery, or the need for rehabilitation are lacking, likely underestimating the true burden of RSV.

Furthermore, detailed clinical information on chronic pre-existing conditions (e.g., severity, immunosuppression, frailty) was not available. This is particularly relevant for adolescents aged 10-19-years, where a high proportion of severe cases was observed in a small number of patients in this age group, but could not be fully explained.

Lastly, temporal trends may be influenced by changes in testing behavior, coding practices, or healthcare utilization—especially during the COVID-19 pandemic—limiting interpretability across the full 2017–2023 period.