Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

25 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

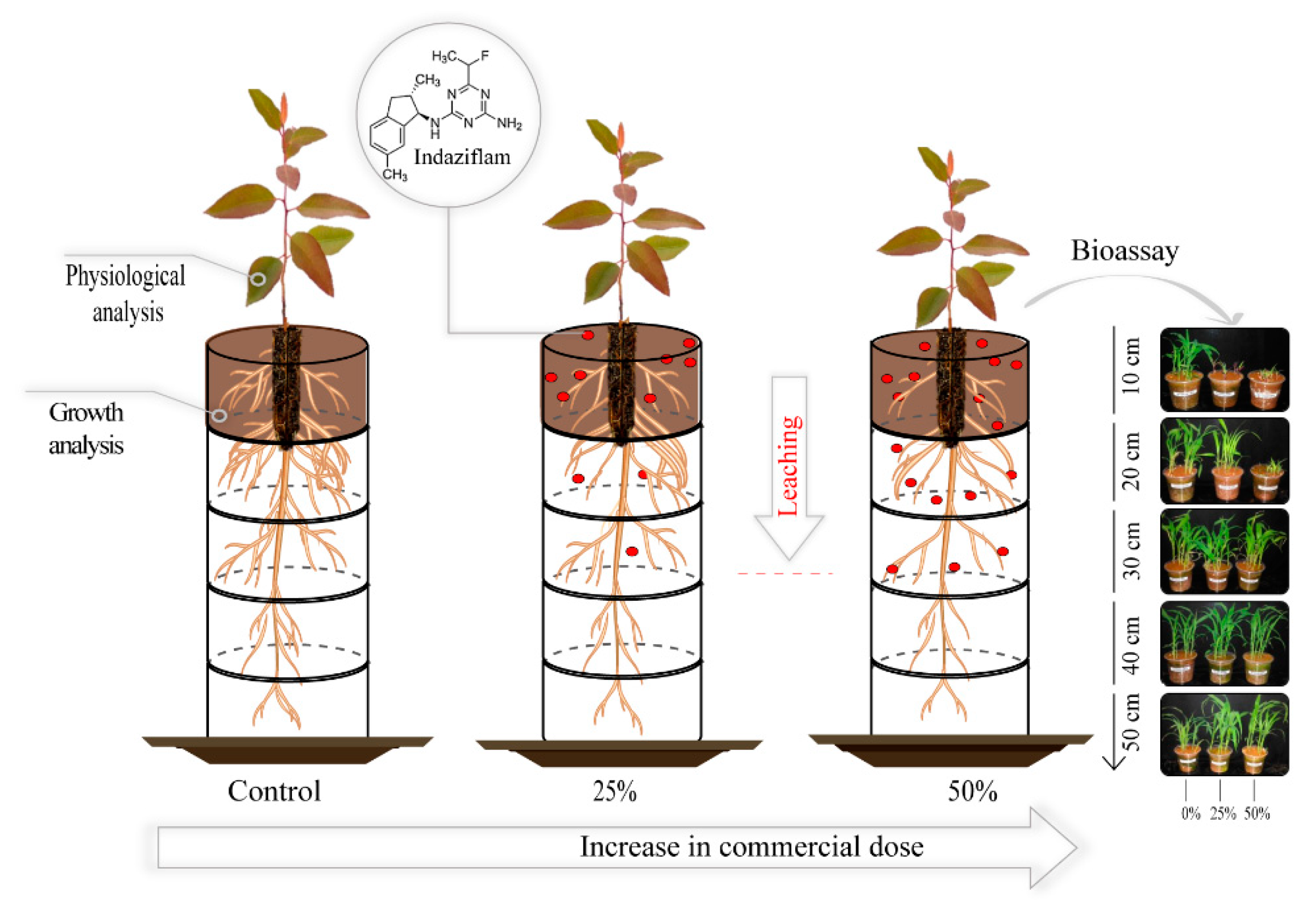

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Application of Indaziflam

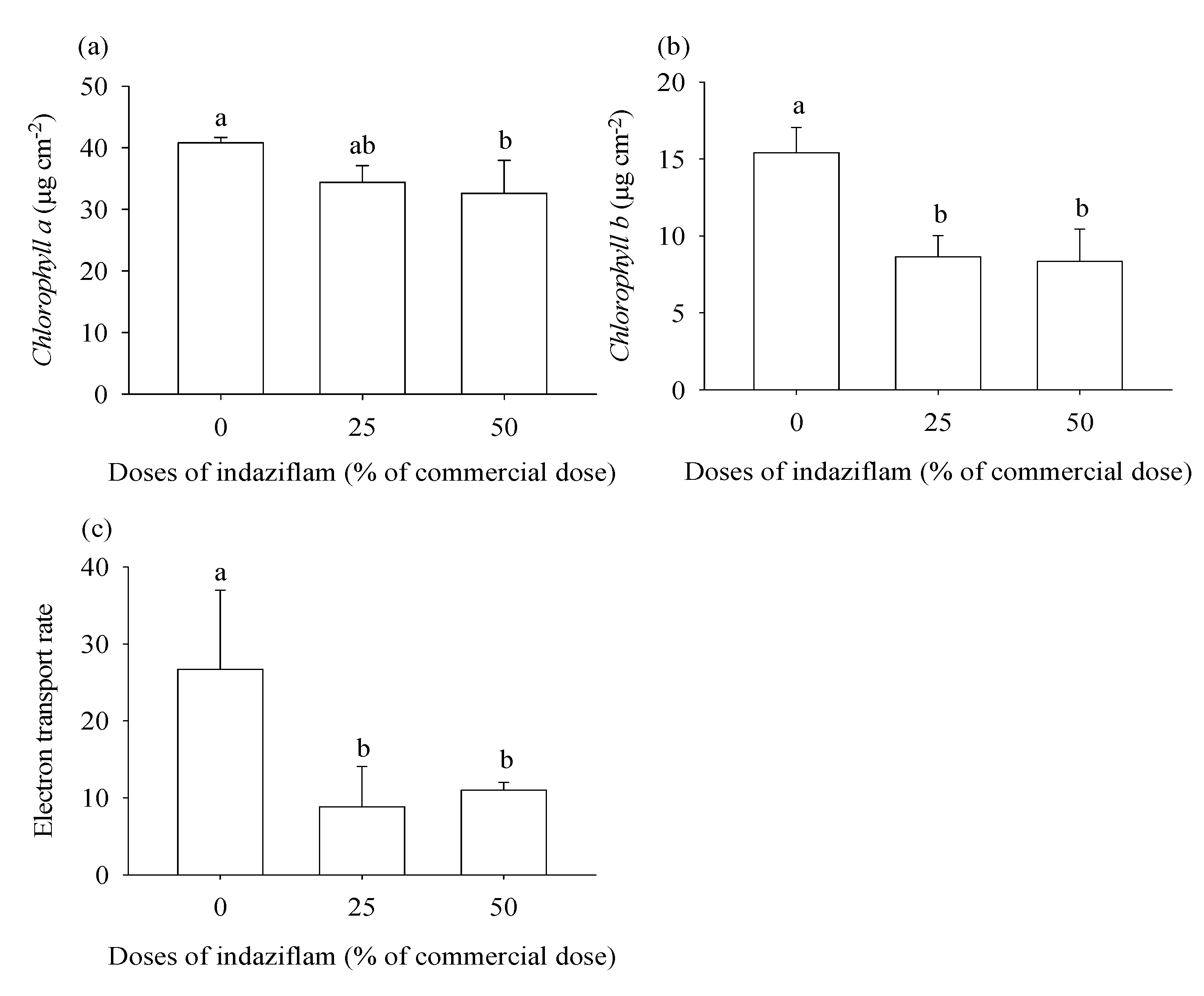

2.3. Chlorophylls a and b and electron transport rate

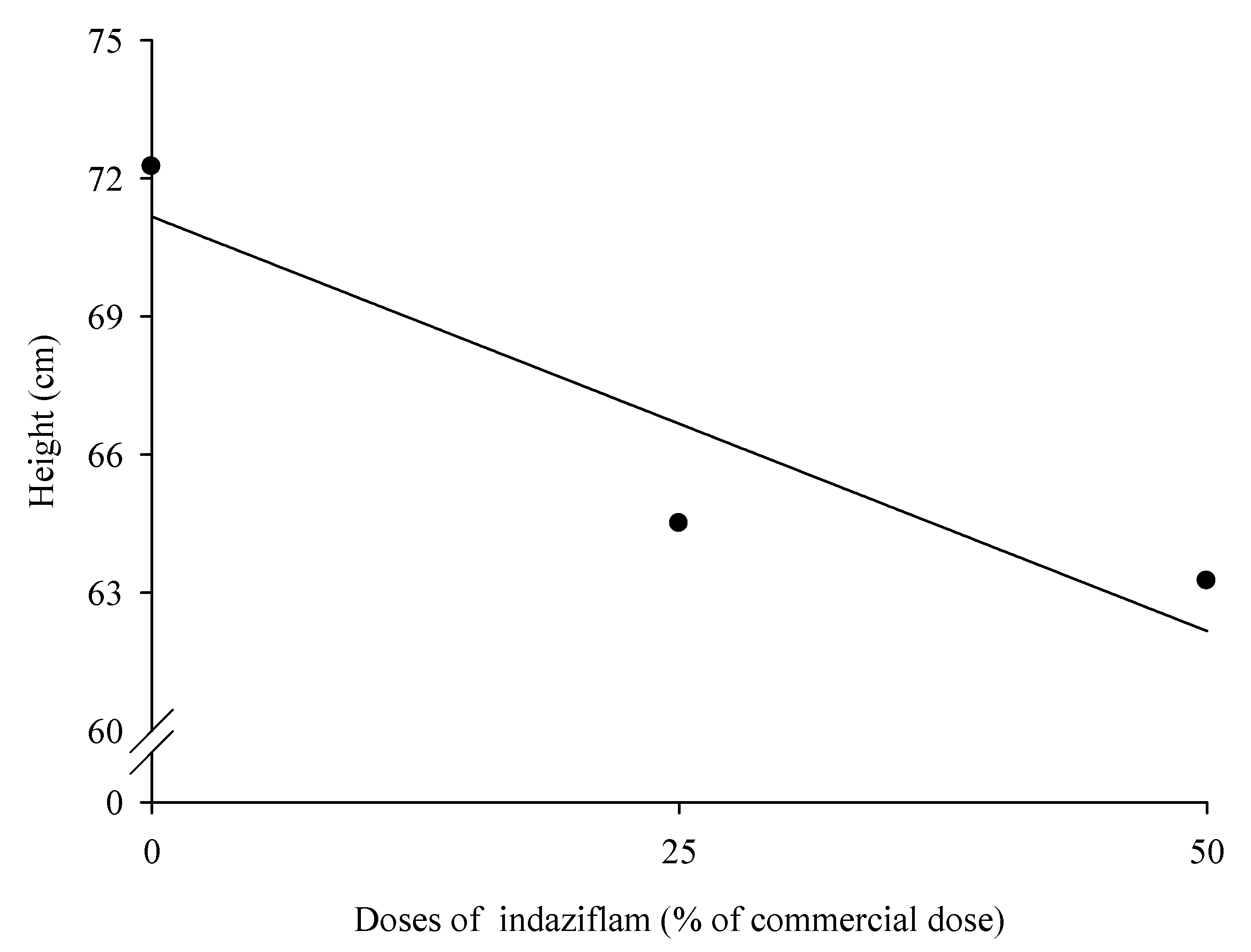

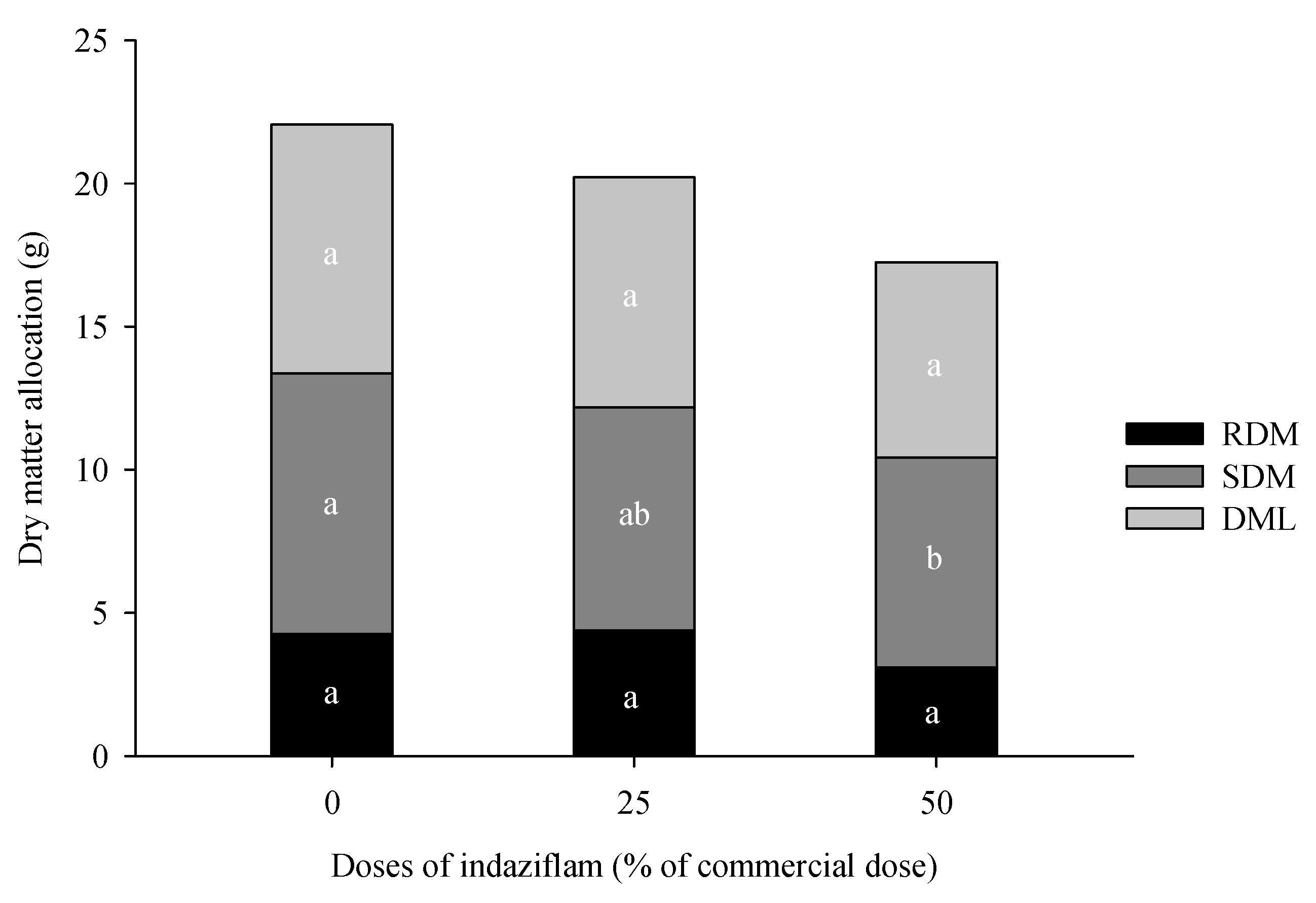

2.4. Height and weight of dry matter of leaves, stems and roots

2.5. Sorghum bicolor as a bioindicator plant

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Eucalyptus plants

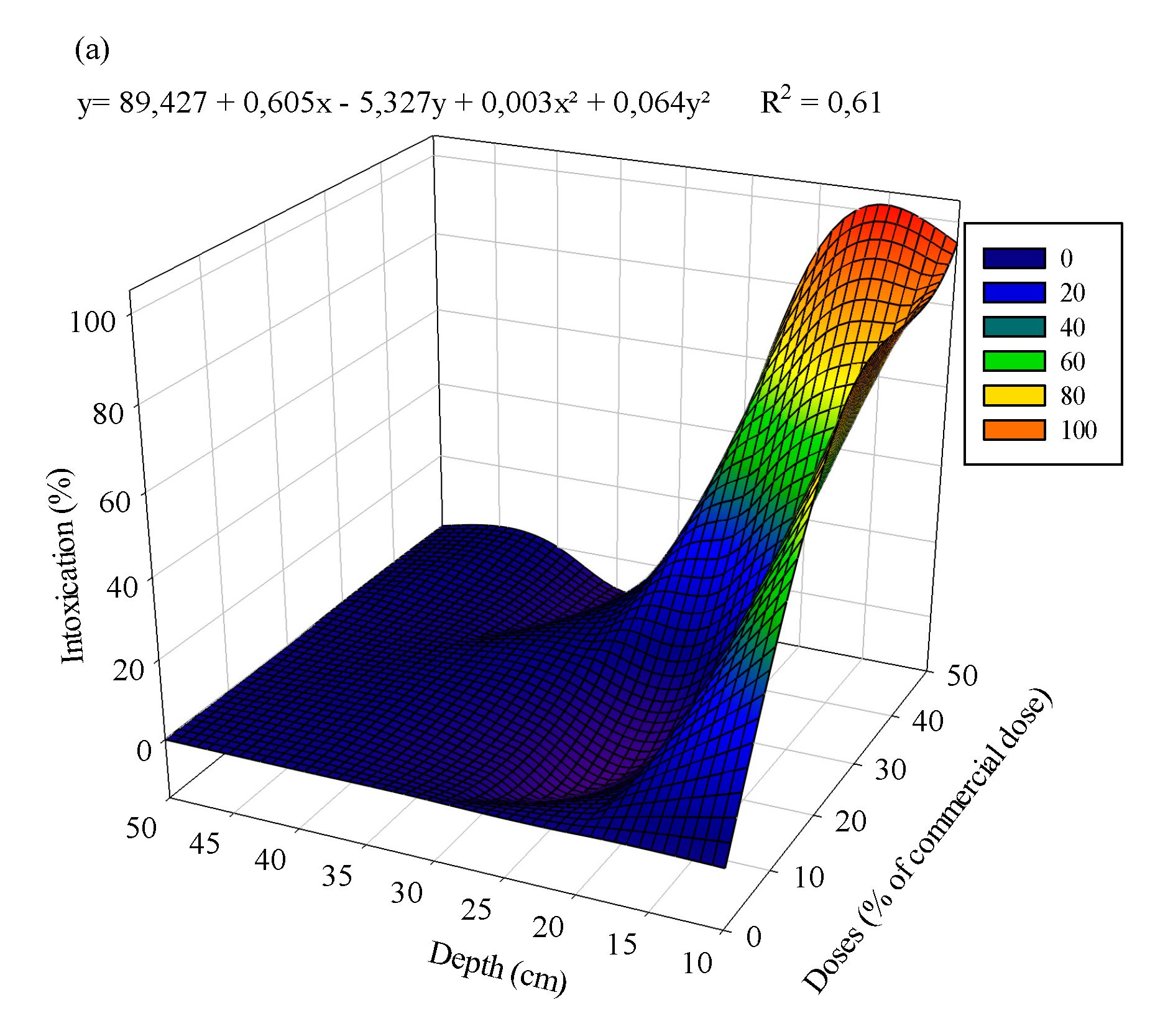

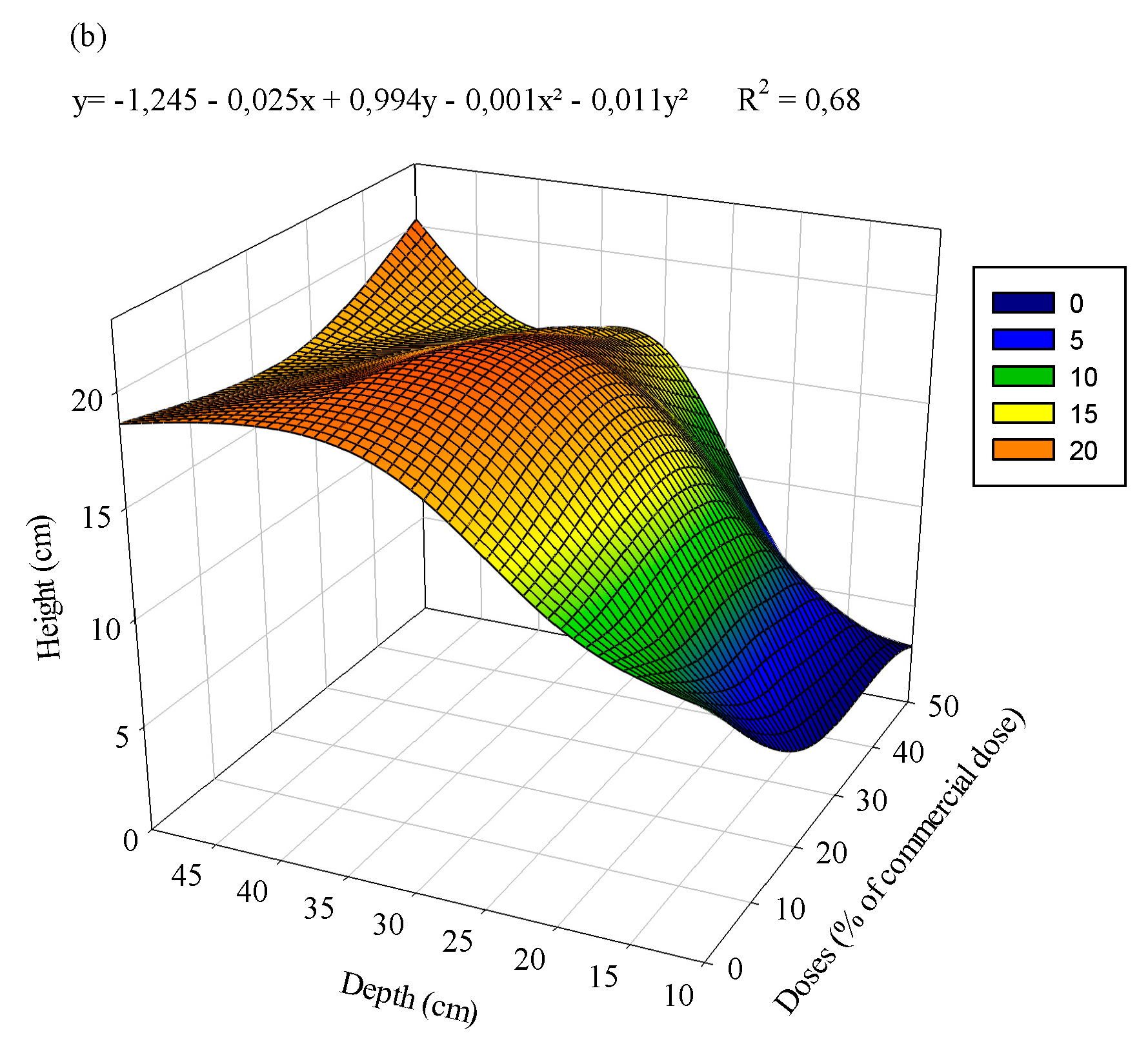

3.2. Sorghum plants

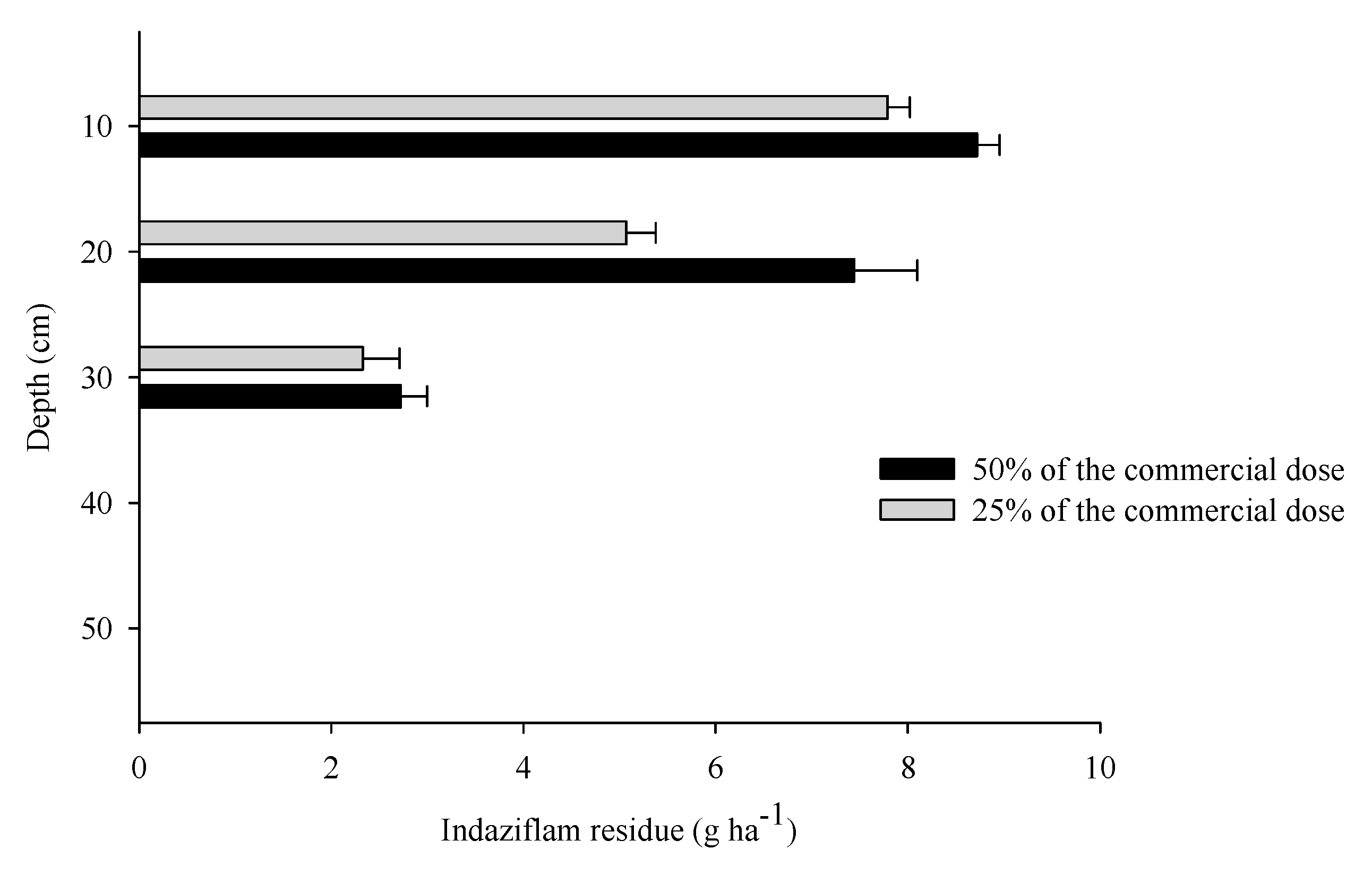

3.3. Residues of indaziflam in the soil

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lock, P.; Legg, P.; Whittle, L.; Black, S. Global Outlook for Wood Markets to 2030: Projections of future production, consumption and trade balance, ABARES report to client prepared for the Forest and Wood Products Australia. Canberra, November. CC BY, 4, 2021.

- Payn, T.; Carnus, J.M.; Freer-Smith, P.; Kimberley, M.; Kollert, W.; Liu, S.; Wingfield, M.J. Changes in planted forests and future global implications. Forest Ecology and Management, 2015, 352, 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Nepal, P.; Korhonen, J.; Prestemon, J.P.; Cubbage, F.W. Projecting global planted forest area developments and the associated impacts on global forest product markets. Journal of environmental management, 2019, 240, 421–430. [CrossRef]

- Ferreto, D.O.C.; Reichert, J.M.; Cavalcante, R.B.L.; Srinivasan, R. Water budget fluxes in catchments under grassland and Eucalyptus plantations of different ages. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2021, 51, 513–523. [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.B.; Benassi, R.B.; Torres, R.R.; de Brito Neto, F.A. Impacts of 1.5 C and 2 C global warming on Eucalyptus plantations in South America. Science of The Total Environment, 2022, 825, 153820. [CrossRef]

- Elli, E.F.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Huth, N.; Carneiro, R.L.; Alvares, C.A. Gauging the effects of climate variability on Eucalyptus plantations productivity across Brazil: a process-based modelling approach. Ecological Indicators, 2020, 114, 106325. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yu, S.; Zhu, H. The predicament and countermeasures of development of global Eucalyptus plantations. Guangxi Sci, 2018, 25, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, L.; Qin, Y.; Doughty, R.; Wang, X.; Yang, X. Mapping Eucalyptus plantation in Guangxi, China by using knowledge-based algorithms and PALSAR-2, Sentinel-2, and Landsat images in 2020. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2023, 120, 103348. [CrossRef]

- Ibá. Indústria Brasileira de Árvores. 2022 [accessed 2023. July 05]. https://www.iba.org/publicacoes.

- Avisar, D.; Azulay, S.; Bombonato, L.; Carvalho, D.; Dallapicolla, H.; de Souza, C.; Silva, W. Safety Assessment of the CP4 EPSPS and NPTII Proteins in Eucalyptus. GM Crops & Food, 2023, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Florêncio, G.W.L.; Martins, F.B.; Fagundes, F.F.A. Climate change on Eucalyptus plantations and adaptive measures for sustainable forestry development across Brazil. Industrial Crops and Products, 2022, 188, 115538. [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.E.; Hubbard, R.M.; Stape, J.L.; de Paula Lima, W.; Moreira, G.G.; de Barros Ferraz, S.F. Stocking effects on seasonal tree transpiration and ecosystem water balance in a fast-growing Eucalyptus plantation in Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management, 2020, 466, 118149. [CrossRef]

- Manzato, B.L.; Manzato, C.L.; Dos Santos, P.L.; Passos, J.D.S.; Da Silva Junior, T.A.F. Diversity of macroscopic basidiomycetes in reforestation areas of Eucalyptus spp. Scientia Forestalis, 2020, 48, e3305. [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.; da Silva, R.M.L.; Moreira, G.G.; Teixeira, J.D.S.; Takahashi, S.; Masson, M.V.; Martins, S.D.S. Growth and canopy traits affected by myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii Winter) in Eucalyptus grandis x Eucalyptus urophylla. Forest Pathology, 2022, 52, e12736. [CrossRef]

- Hutapea, F.J.; Weston, C.J.; Mendham, D.; Volkova, L. Sustainable management of Eucalyptus pellita plantations: A review. Forest Ecology and Management, 2023, 537, 120941. [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.F.; Barroso, A.A.M.; Amaral, C.L.; Nepomuceno, M.P.; Alves, P.L.C.A. Population interference of glyphosate resistant and susceptible ryegrass on eucalyptus initial development. Planta Daninha, 2018, 36, e018170148. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yang, G.; Xie, Z.; Yu, J.; Jiang, D.; Huang, Z. Effects of different weeding methods on the biomass of vegetation and soil evaporation in eucalyptus plantations. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 3669. [CrossRef]

- Smethurst, P.J.; Valadares, R.V.; Huth, N.I.; Almeida, A.C.; Elli, E.F.; Neves, J.C. Generalized model for plantation production of Eucalyptus grandis and hybrids for genotype-site-management applications. Forest Ecology and Management, 2020, 469, 118164. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, L.B.; Duke, S.O.; Alves, P.D.C. Physiological responses of Eucalyptus × urograndis to glyphosate are dependent on the genotype. Scientia Forestalis, 2018, 46, 177–187. [CrossRef]

- Minogue, P.J.; Osiecka, A.; Lauer, D.K. Selective herbicides for establishment of Eucalyptus benthamii plantations. New Forests, 2018, 49, 529–550. [CrossRef]

- Agrofit - Sistema de Agrotóxicos fitossanitários. 2023. Available online: http://agrofit.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons. [accessed 2023. February 13].

- Agostinetto, D.; Tarouco, C.P.; Markus, C.; Oliveira, E.D.; Da Silva, J.M.B.V.; Tironi, S.P. Selectivity of eucalyptus genotypes to herbicides rates. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, 2010, 31, 585-598.

- De Abreu, K.M.; de Castro Santos, D.; Pennacchi, J.P.; Calil, F.N.; Moura, T.M.; Alves, E.M.; de Souza, S.O. Differential tolerance of four tree species to glyphosate and mesotrione used in agrosilvopastoral systems. New Forests, 2022, 53, 831-850. [CrossRef]

- Tiburcio, R.A.S.; Ferreira, F.A.; Paes, F.A.S. V.; Melo, C.A.D.; Medeiros, W.N. Growth of eucalyptus clones seedlings submitted to simulated drift of different herbicides. Revista Árvore, 2012, 36, 65-73. [CrossRef]

- Basinger, N.T.; Jennings, K.M.; Monks, D.W.; Mitchem, W.E. Effect of rate and timing of indaziflam on ‘Sunbelt’ and muscadine grape. Weed Technology, 2019, 33, 380–385. [CrossRef]

- Grey, T.L.; Rucker, K.; Webster, T.M.; Luo, X. High-density plantings of olive trees are tolerant to repeated applications of indaziflam. Weed Science, 2016, 64, 766–771. [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J.T.; Breeden, G.K.; McCullough, P.E.; Henry, G.M. Pre and post control of annual bluegrass (Poa annua) with indaziflam. Weed Technology, 2012, 26, 48–53. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, D.G.; Oliveira, R.S.D.; Koskinen, W.C.; Hall, K.; Constantin, J.; Mislankar, S. Sorption and desorption of indaziflam degradates in several agricultural soils. Scientia Agrícola, 2016, 73, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, V.A.; Ferreira, L.R.; Teixeira, M.F.F.; De Freitas, F.C.L.; D'Antonino, L. Sorption of indaziflam in brazilian soils with different pH values. Revista Caatinga, 2021, 34, 494–504. [CrossRef]

- SBCPD - Sociedade Brasileira da Ciência das Plantas Daninhas. Procedimentos para instalação, avaliação e análise de experimentos com herbicidas. Londrina-PR, 1995.

- Ferreira, E.B.; Cavalcanti, P.P.; Nogueira, D.A. ExpDes.pt: Experimental Designs (Portuguese). R package version 3.4.3. 2013.

- Seefeldt, S.S.; Jensen, J.E.; Fuerst, E.P. Log-Logistic analysis of herbicide dose-response relationships. Weed Technology, 1995, 9, 218–227.

- Rabelo, J.S.; Dos Santos, E.A.; de Melo, E.I.; Vaz, M.G.M.V.; de Oliveira Mendes, G. Tolerance of microorganisms to residual herbicides found in eucalyptus plantations. Chemosphere, 2023, 329, 138630. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C.; Jennings, K.M.; Monks, D.W.; Jordan, D.L.; Reberg-Horton, S.C.; Schwarz, M.R. Sweetpotato tolerance and Palmer Amaranth control with indaziflam. Weed Technology, 2022, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Rasool, G.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Shao, G. Effects of vertically heterogeneous soil salinity on tomato photosynthesis and related physiological parameters. Scientia Horticulturae, 2019, 249, 120–130. [CrossRef]

- Eng, W.H.; Ho, W.S. Polyploidization using colchicine in horticultural plants: a review. Scientia horticulturae, 2019, 246, 604–617. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.B.; Costa, A.C.; Müller, C.; Almeida, G.M.; Nascimento, K.J.T.; Batista, P.F.; Domingos, M. Searching for biomarkers of early detection of 2,4-D effects in a native tree species from the Brazilian Cerrado biome. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 2022, 57, 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A.; Brosnan, J.T.; Kopsell, D.A.; Armel, G.R.; Breeden, G.K. Preemergence herbicides affect hybrid bermudagrass nutrient content. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 2015, 38, 177–188. [CrossRef]

- Najafpour, M.M.; Zaharieva, I.; Zand, Z.; Hosseini, S.M.; Kouzmanova, M.; Hołyńska, M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Water-oxidizing complex in Photosystem II: Its structure and relation to manganese-oxide based catalysts. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2020, 409, 213183. [CrossRef]

- 4Meyer, D.F. Indaziflam-A new herbicide for pre-emergent control of grasses and broadleaf weeds for turf and ornamentals. 2019. Available online: http://wssa.net/meeting/ meeting abstracts. [accessed 2022. June 20].

- Gomes, C.A.; Pucci, L.F.; Alves, D.P.; Leandro, V.A.; Pereira, G.A.M.; Reis, M.R.D. Indaziflam application in newly transplanted arabica coffee seedlings. Coffee Science, 2019, 14, 373–381.

- Evans, J.R.; Vogelmann, T.C. Photosynthesis within isobilateral Eucalyptus pauciflora leaves. New Phytologist, 2006, 171, 771–782. [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, Y.K.S.; De Freitas, F.C.L.; Da Silveira, H.M.; Nascimento, R.S.M.; Sediyama, C.S.; Alcantara-de la Cruz, R. Herbicide selectivity on Macauba seedlings and weed control efficiency. Industrial Crops and Products, 2020, 154, 112725. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Vanderhaeghen, R.; Cools, T.; Wang, Y.; De Clercq, I.; Leroux, O.; De Veylder, L. Mitochondrial defects confer tolerance against cellulose deficiency. The Plant Cell, 2016, 28, 2276–2290. [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. Pesticide fact sheet for indaziflam. 2010. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/opprd001/ factsheets/indaziflam.pdf. [accessed 2023. July 22].

- Jhala, A.J.; Singh, M. Leaching of indaziflam compared with residual herbicides commonly used in Florida citrus. Weed Technology, 2012b, 26, 602–607. [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, A.M.; Shukla, M.K.; Ashigh, J.; Perkins, R. Effect of application rate and irrigation on the movement and dissipation of indaziflam. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2017, 51, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Jhala, A.J.; Ramirez, A.H.M.; Singh, M. Leaching of indaziflam applied at two rates under different rainfall situations in Florida candler soil. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2012a, 88, 326–332. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.G.; Haguewood, J.B.; Song, E.; Pan, X.; Rutledge, J.M.; Monke, B.J.; Xiong, X. Indaziflam effect on bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon L. Pers.) shoot growth and root initiation as influenced by soil texture and organic matter. Crop Science, 2015, 55, 429–436. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, D.G.; Oliveira Jr, R.S.; Hall, K.E.; Koskinen, W.C.; Constantin, J.; Mislankar, S. Changes in sorption of indaziflam and three transformation products in soil with aging. Geoderma, 2015, 239, 250–256. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, K.F.; Furtado, I.F.; Sousa, R.N.D.; Lima, A.D.C.; Mielke, K.C.; Brochado, M.G.D.S. Cow bonechar decreases indaziflam pre-emergence herbicidal activity in tropical soil. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 2021, 56, 532–539. [CrossRef]

| Physical analysis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Clay | Silt | Texture Class | ||||||||||

| (dag kg-1) | |||||||||||||

| 6 | 69 | 25 | Very clayey | ||||||||||

| Chemical analysis | |||||||||||||

| pH | P | K | Ca | Mg2+ | Al3+ | H+Al | SB | t | T | V | m | OM | |

| (H2O) | (mg dm-3) | (Cmolcdm-3) | (%) | (dag kg-1) | |||||||||

| 5.00 | 0.54 | 31 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.80 | 4.62 | 0.39 | 1.19 | 5.01 | 7.8 | 67.2 | 1.88 | |

| Element | Source | Molecular Formula | Amount (mg L-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Urea | CH4N2O | 9,89 |

| P | Phosphoric acid | H3PO4 | 0,15 |

| K | Potassium chloride | KCl | 5,36 |

| Ca | Anhydrous Calcium Chloride | CaCl2 | 11,56 |

| Mg | Magnesium chloride | MgCl2(6H2O) | 4,82 |

| S | Sodium sulfate | Na2SO4 | 2,84 |

| B | Boric acid | H3BO3 | 0,05 |

| Cu | Copper Chloride | CuCl | 0,003 |

| Fe | Iron Chloride | FeCl3 | 0,25 |

| Mn | Manganese Chloride | MnCl2(4H2O) | 0,056 |

| Zn | Zinc Chloride | ZnCl2 | 0,011 |

| Mo | Sodium Molybdate | Na2MoO4 | 0,0052 |

| EDTA (5,44 g) + 0,824 g de NaOH | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).