1. Introduction

A brain disorder called epilepsy is characterised by recurrent seizures brought on by erratically discharged electrical currents in the brain. Epilepsy is a chronic condition brought on by excessive electrical discharge in the brain, which results in unconsciousness and other uncontrollable behavioural changes [

1,

2]. Three-fourths of the 80% of epileptic patients in low- and middle-income countries experience either a treatment gap or a lack of anti-seizure medications. Because of this, epileptic events can happen at any time and with any frequency, which makes diagnosis and treatment challenging. Pre-ictal, ictal, post-ictal, and inter-ictal are the four stages of a seizure. Pre-ictal is just before the occurrence of an epileptic seizure; Ictal is the onset period; post-ictal is just after the onset up to 10 minutes; and inter-ictal is after around 10 minutes of onset and lasts till the next occurrence of a seizure.

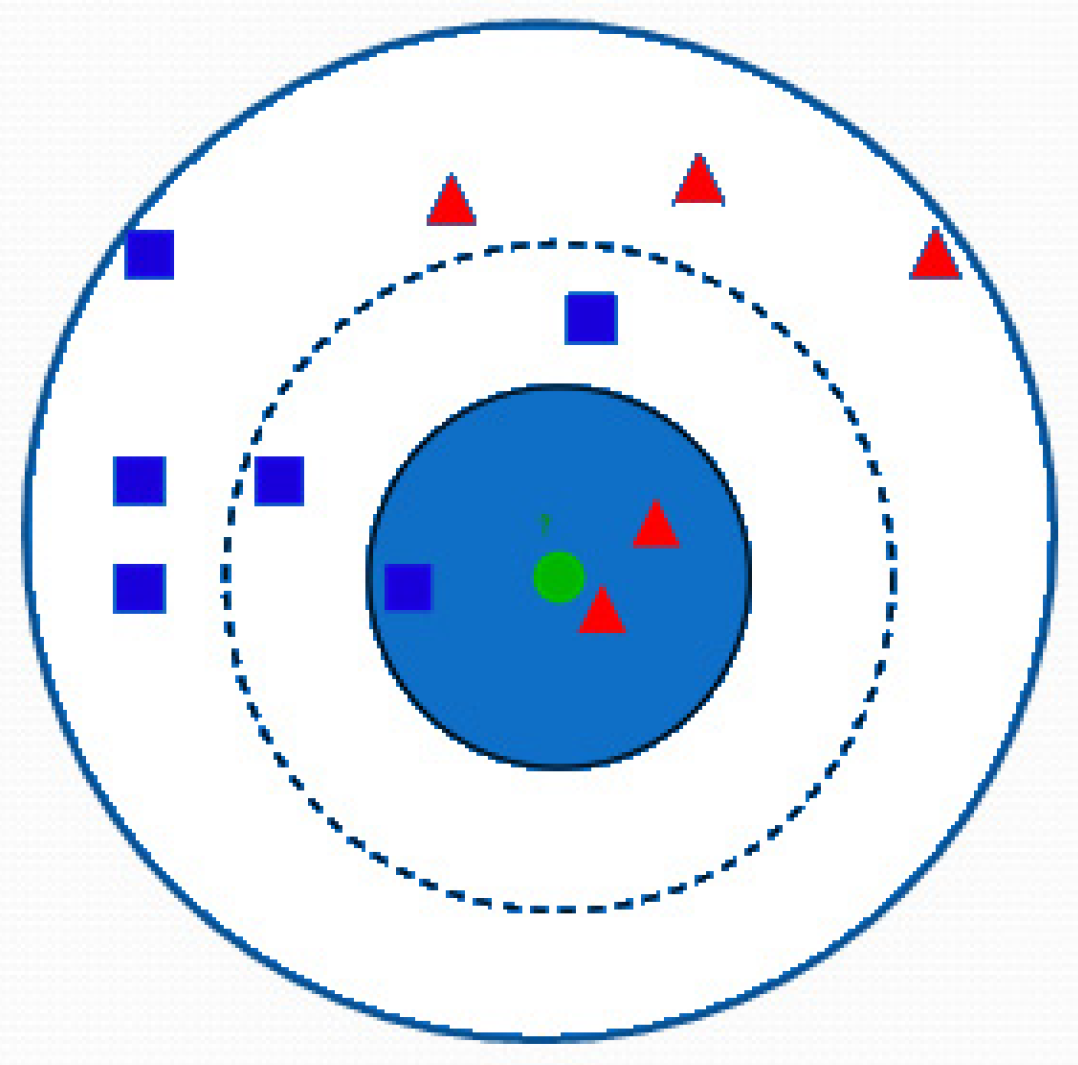

Figure 1 depicts all four stages of seizure. The pre-ictal stage usually involves dizziness, headache, and nausea and is followed by the stage of intense electrical activity in the brain called the ictal region. Then comes the post-ictal region, where the patient returns to baseline conditions along with symptoms like disorientation, drowsiness, and headache.

The advent of machine learning and their increasing popularity in healthcare applications make it possible to classify majorly a) seizure-free and b) different types of seizures, but it’s done in the ictal period, and having a high-frequency EEG signal with spikes makes classification a little simpler. A good amount of research work is available in the Ictal stage but not in the pre-Ictal and Inter-Ictal stages, and very little focus is placed on the detection of seizure types in different stages.

Here, different studies present in the literature based on stage detection like ictal, pre-ictal, interictal, post-ictal, sleep stage, and mental state have been focused. In [

3,

4], the epileptic episode in EEG signals was detected automatically using a least squares support vector machine classifier with a radial basis function kernel. Here, normal stage, ictal stage, and inter-ictal stage are distinguished from the recorded EEG signal. The authors have indicated a wide scope for this method if the investigations can be done with real-time data and a large dataset collected via a multi-centre clinical trial. Whereas autonomously generalised retrospective and patient-specific hybrid models have been carried out in [

5,

6,

7]. These studies used Convolutional Neural Networks(CNN) and long short-term memory(LSTM) as classifier. To better categorise ictal, interictal, and preictal segments for each patient and make it suitable for real-time, the model automatically creates customizable characteristics. This work demonstrates that the accuracy of seizure detection can be greatly increased by combining CNNs and LSTMs, incorporating spatial and temporal context, and time-frequency domain information. On the other side, unlike most of the existing works focusing on seizure data or a single-variate method, this paper introduces a multi-variate method to characterise sensor-level brain functional connectivity from interictal EEG data to identify patients with generalised epilepsy. A total of nine connectivity features based on five different measures in time, frequency, and time-frequency domains have been tested. The solution has been validated by the K-Nearest Neighbour algorithm, classifying an epilepsy group (EG) vs. a healthy control (HC), and subsequently, with another cohort of patients characterised by non-epileptic attacks (NEAD), a psychogenic type of disorder was tried out [

8,

9].

Entropy-based methods [

10,

11] are widely used for the automated detection of seizures from EEG signals due to the nonlinear and chaotic nature of these signals. Two recently introduced entropy features, multiscale dispersion entropy (MDE) and refined composite multiscale dispersion entropy (RCMDE), are used for the detection of seizures. The ability of MDE and RCMDE to discriminate the normal EEGs of healthy subjects from the interictal (in between seizures) and ictal (during seizures) EEGs of epilepsy patients Two more parameters are investigated, namely, the number of classes c and embedding dimension m of MDE and RCMDE that provide the best performance for seizure detection. For this purpose, the MDE and RCMDE values are estimated from normal, interictal, and ictal EEG signals, and significant features are fed to a support vector machine (SVM) classifier. Where the sleep stage classification from single-channel EEG was tried using the statistical features in the time domain, the structural graph similarity and the K-means were combined to identify six sleep stages. This method extracts features efficiently without pre-processing the signal [

12,

13,

14]. In [

15,

16,

17], the feasibility of a passive brain-computer interface that uses electroencephalography to monitor changes in mental state on a single-trial basis and the frontal and central electrodes for fatigue detection, posterior alpha band and frontal beta band activity for frustration detection, and posterior alpha band activity for attention detection for feature extraction is discussed. Where classification against low levels of supervised training using time-frequency subbands until the sixth level using the dual-tree complex wavelet transform method is carried out in [

18]. The feature extraction uses energy, standard deviation, root-mean-square, Shannon entropy, mean values, and maximum peaks, and these feature sets are passed through a general regression neural network (GRNN) for classification with a K-fold cross validation scheme under varying train-to-test ratios.

Most of such analysis is carried out with non-invasive EEG signal recording during clinical intervention. However, the information of patients who underwent invasive VEM was retrospectively examined [

19,

20,

21]. It included at least one EIS and one SHS that happened during VEM, and the area of the brain where the EIS were evoked was removed. According to the classification used by Engel and the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), seizure outcome was assessed at three follow-up (FU) visits after surgery—one at one year, one at two years, and one at the last FU that was still possible.

In order to distinguish between a patient's three stages of "normal," "pre-ictal," and "ictal," Acharya et al. [

22,

23,

24] used an ensemble of seven distinct classifiers, including the Fuzzy Surgeon Classifier (FSC), SVM, KNN, Probabilistic Neural Network, GMM, decision tree, and Nave Bayes. Overall precision is 98.1%. Using the processed data containing seven features, including entropy, RMS, skewness, and variance, [

25,

26] also employed various classifiers, including a logistic classifier, an uncorrelated normal density-based classifier (UDC), a polynomial classifier, a KNN, a PARZEN, a SVM, and a decision tree. They stated that the patient was being diagnosed with a "generalised seizure," which refers to a seizure that affects the entire brain without prior knowledge of the seizure focal spots. Optimal sample allocation methodology, a statistical sampling strategy, was proposed by Mursalin et al. [

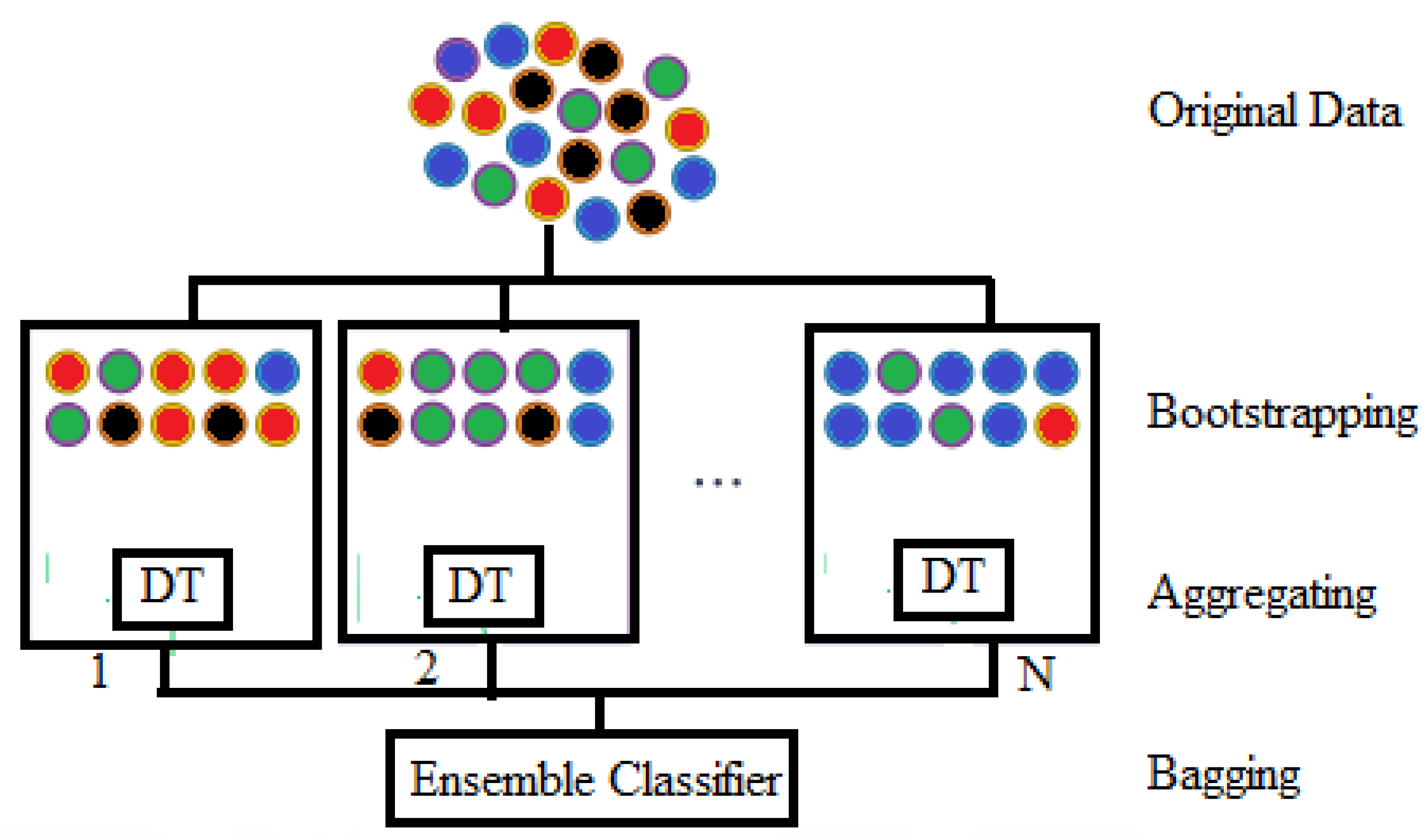

27], and they developed a feature selection algorithm to reduce the features. The combination of four classifiers—SVM, KNN, NB, Logistic Model Trees (LMT), and Random Forest—was used for the analysis.

Four classifiers, including SVM, KNN, random forest, and Adaboost, were utilised by Rand and Sriram [

28] on a high-dimensional dataset created from 28 features. Their findings demonstrate that the SVM outperforms the cubic kernel. Using the dataset generated by 10-time and frequency characteristics, [

28] employed SVM and random forests. A random forest classifier performs better than an SVM-based detector. Using four machine learning classifiers, including ANN, KNN, SVM, and random forest, on two well-known datasets—Freiburg and CHB-MIT—[

29] classified the three distinct seizure states of "pre-ictal," "ictal," and "inter-ictal" seizures with 100% accuracy. For identifying the EEG signals, [

30,

31] suggested an automated approach employing iterative filtering and random forests. The classification accuracy of this work was 99.5% for the A against E subsets on the BONN dataset (A-E), 96% for the D versus E subsets, and 98.4% for the ABCD versus E classes of EEG signals. KNN is used to distinguish between the "seizure" and "non-seizure" classes, and random forest is used to explore the significant channels, according to [

32]. Here, the dimension reduction issue is also helped by the random forest. The key advantage of choosing appropriate channels is that it enables the provision of pertinent information from the selected channels and lowers the computational cost of a classifier as well. Nevertheless, the authors omitted crucial details from channel selection, such as locating the seizure's position on the brain's scalp. The fundamental criticism in [

30,

31,

32] is that a large number of features causes the attribute size of the dataset to grow, which negatively affects accuracy and calculation time.

From the literature, it is noted that automatic seizure detection plays a vital role in epilepsy treatment. Many studies have explained the role of machines and deep learning models in seizure diagnostics. To protect epileptic patients from sudden falls or understand their condition, it is important to detect and predict the stage of a seizure. In the recent past, few studies focused on seizure stage prediction, but classification of all stages with raw EEG data was not considered for most of the experiments.

In this work, three datasets, namely FH, CHB-MIT, and TUHEEG, are used and classified into four stages using KNN and RF. The second section of this paper deals with the method.

Section 3 and

Section 4 explain the results and conclusion, respectively.