Submitted:

21 July 2023

Posted:

24 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

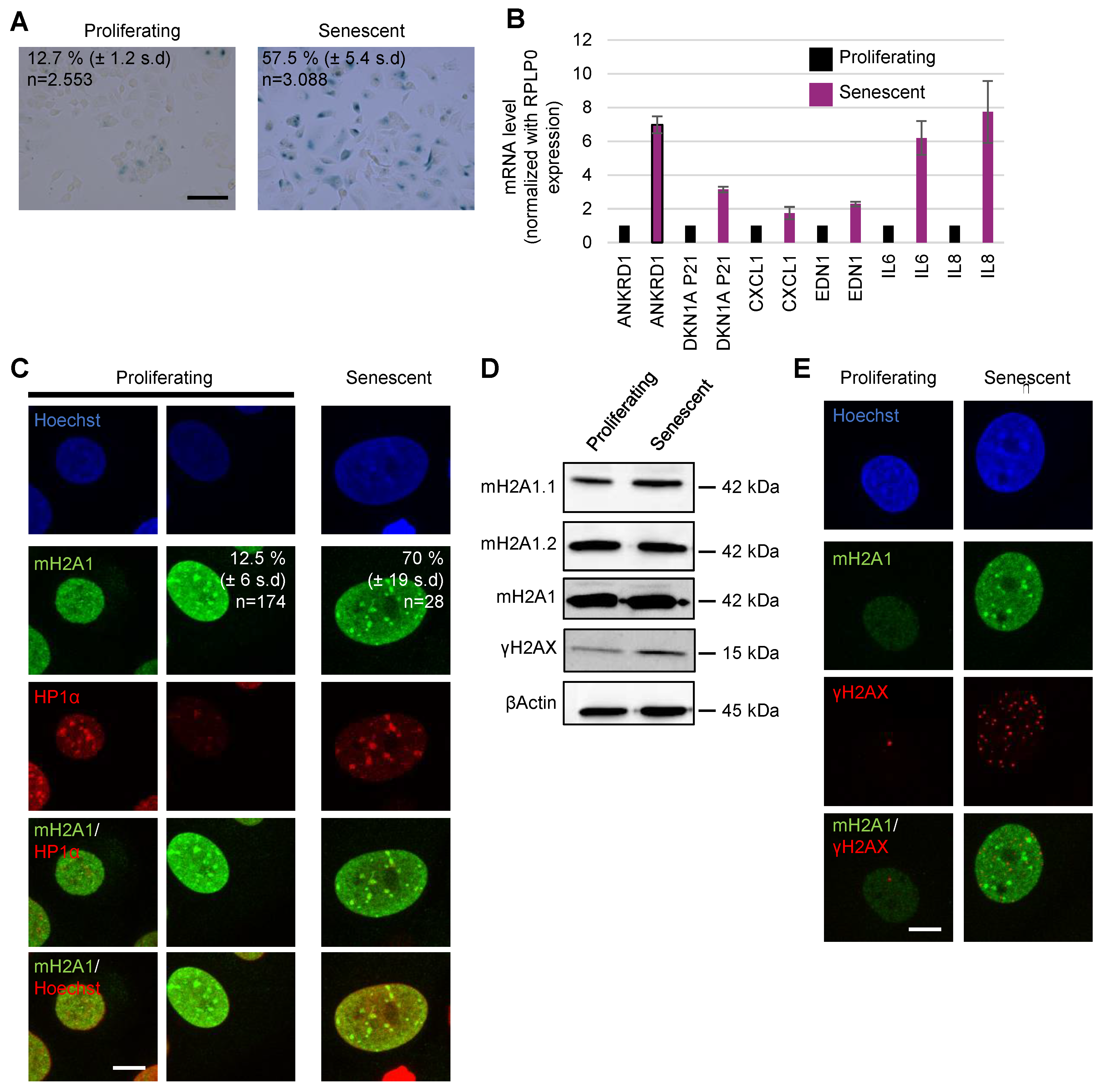

3.1. The histone variant mH2A1 accumulates at pericentric heterochromatin in mouse senescent cells.

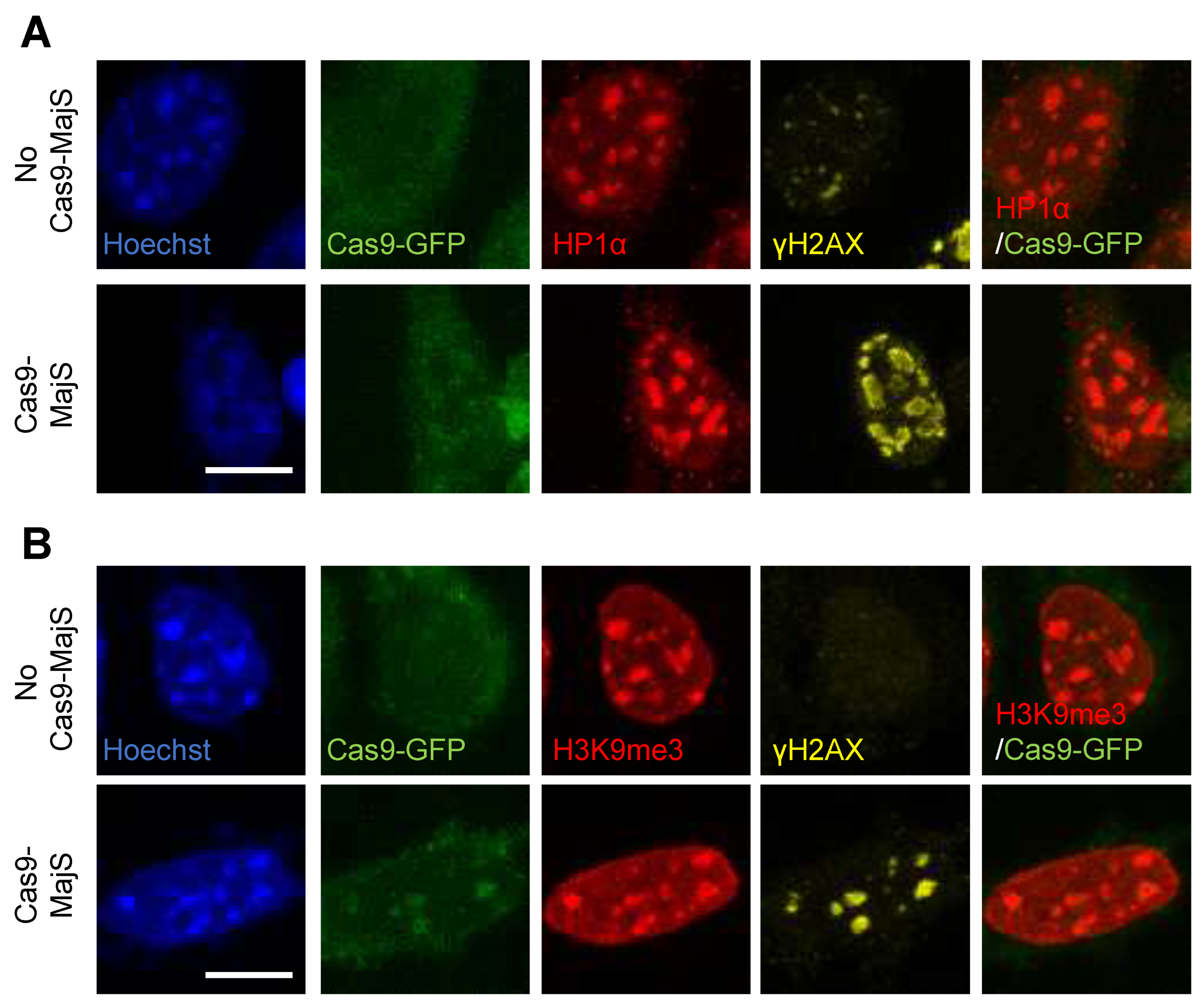

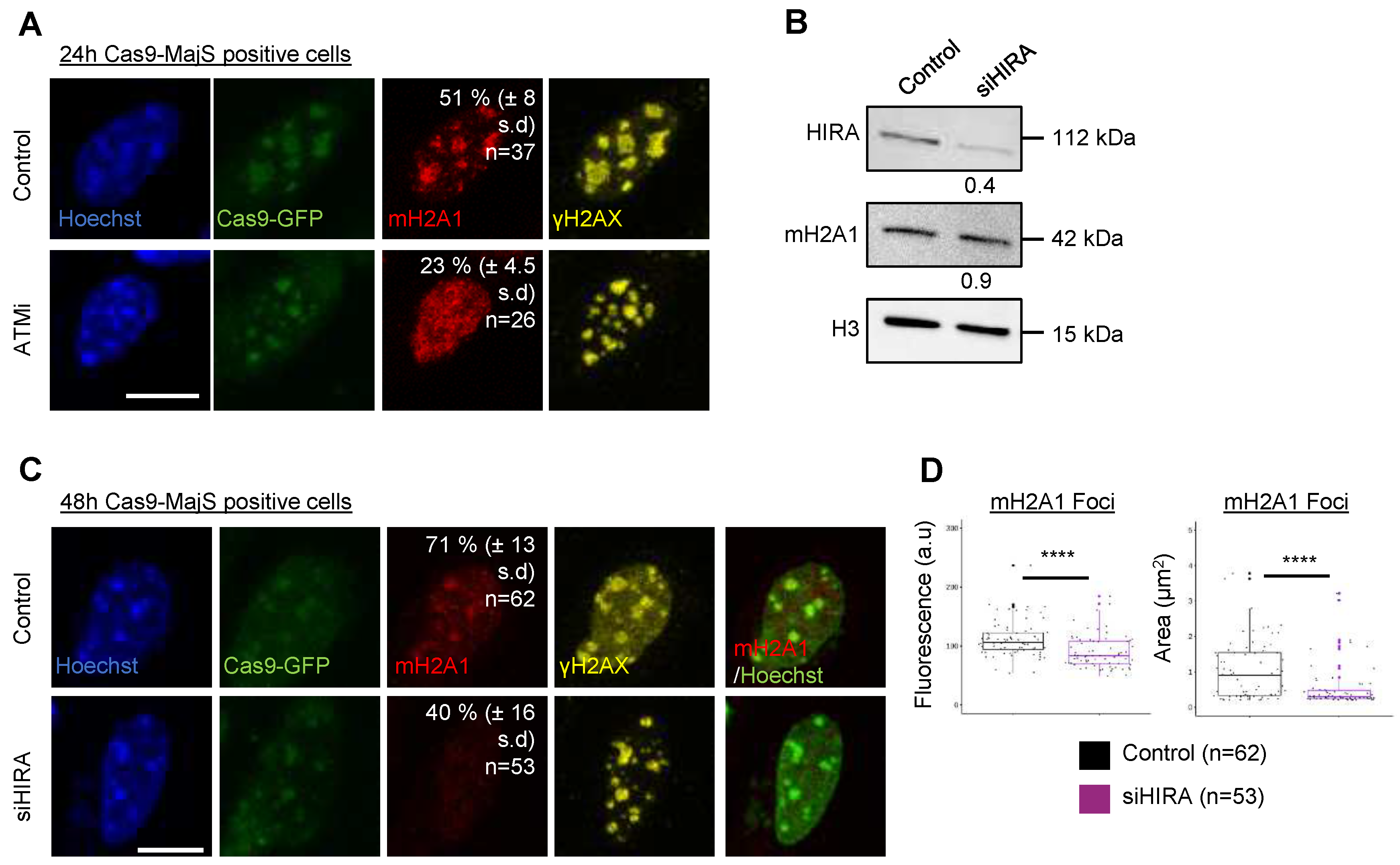

3.2. Cas9-mediated Induction of DSBs at pericentric heterochromatin triggers recruitment of mH2A1.

3.3. mH2A1 recruitment to pericentric regions is not cell type dependent.

3.4. DSBs are not necessary for mH2A1 recruitment to pericentric regions.

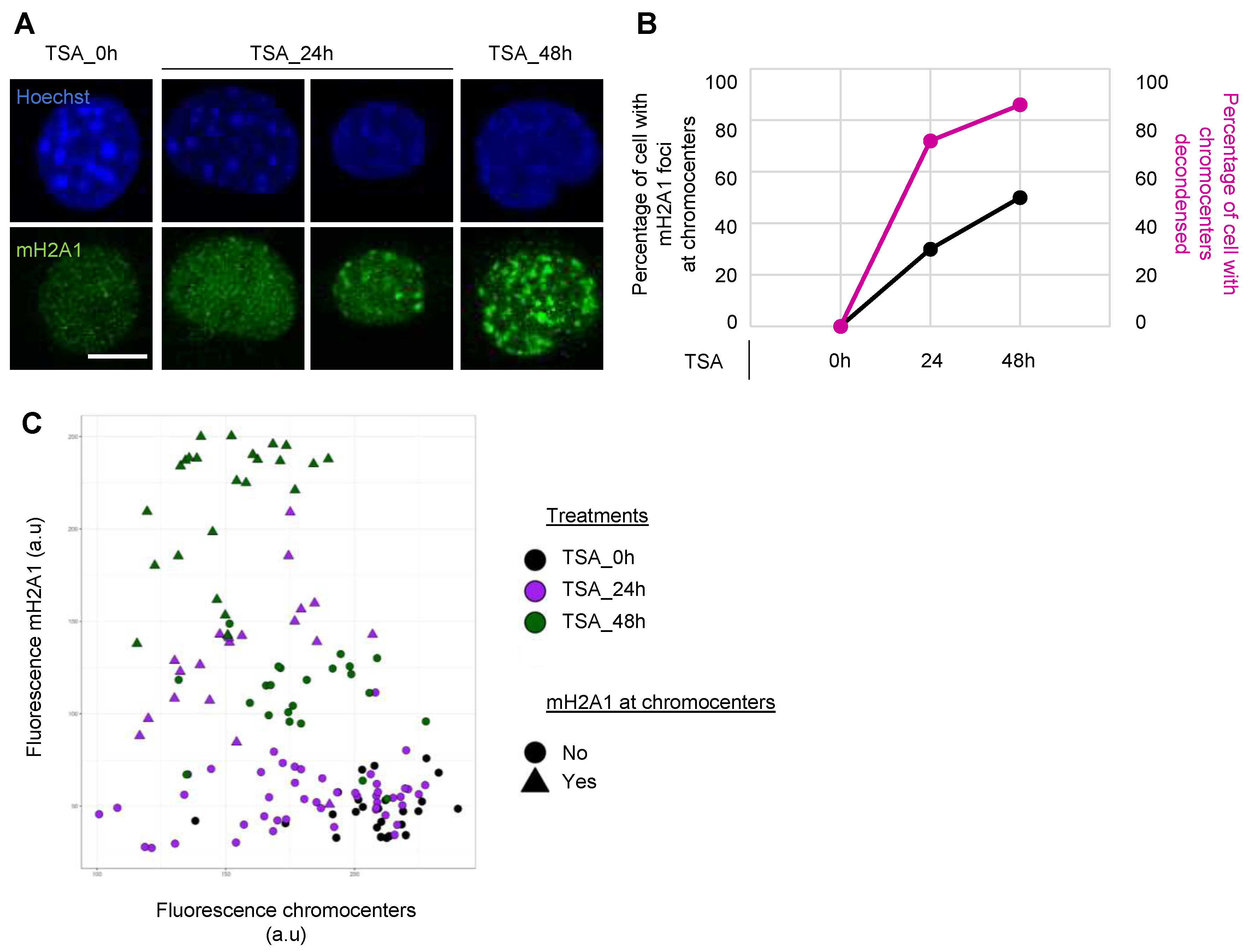

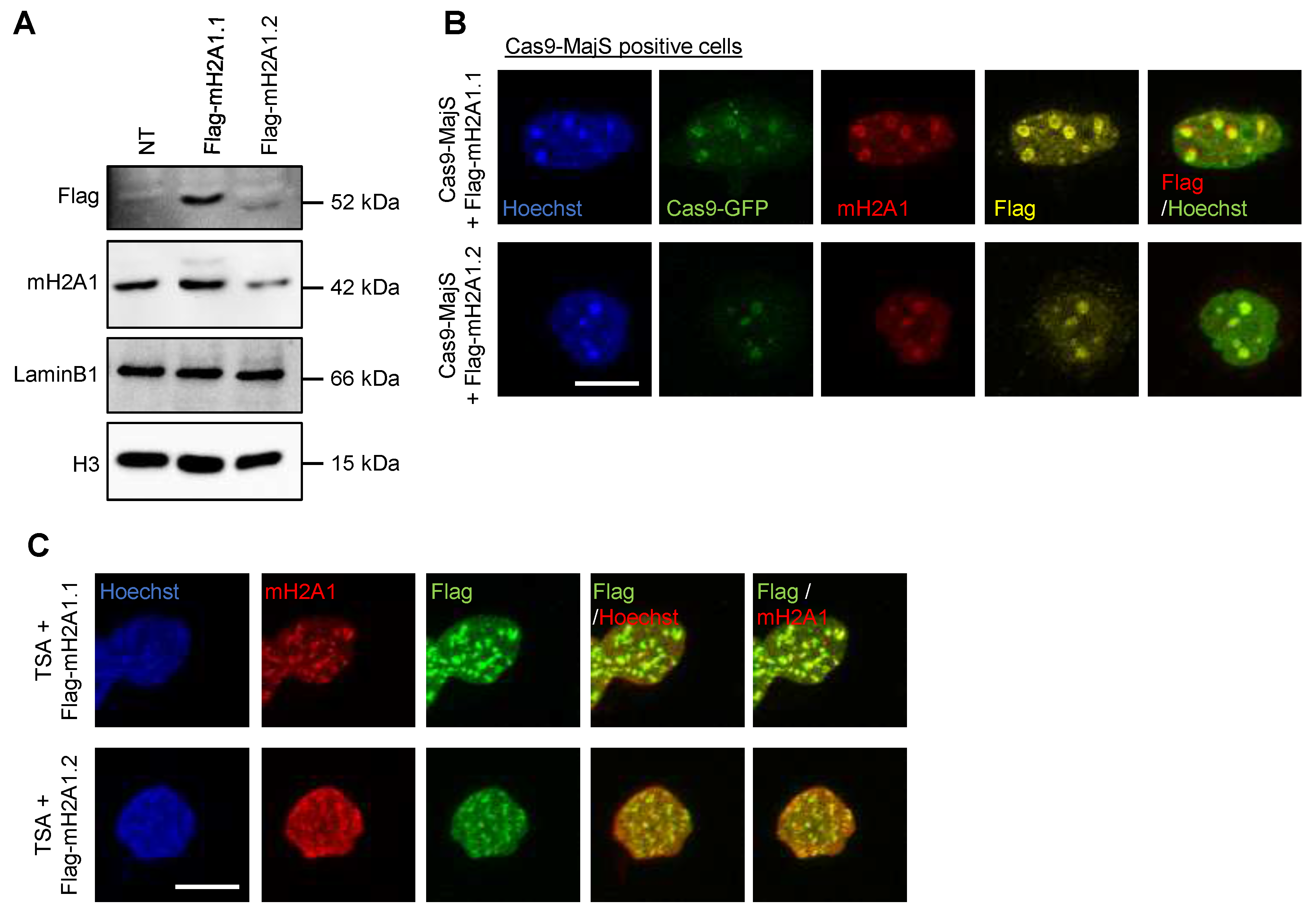

3.5. Recruitment of mH2A1 proteins to pericentric heterochromatin depends on chromocenter partial decondensation.

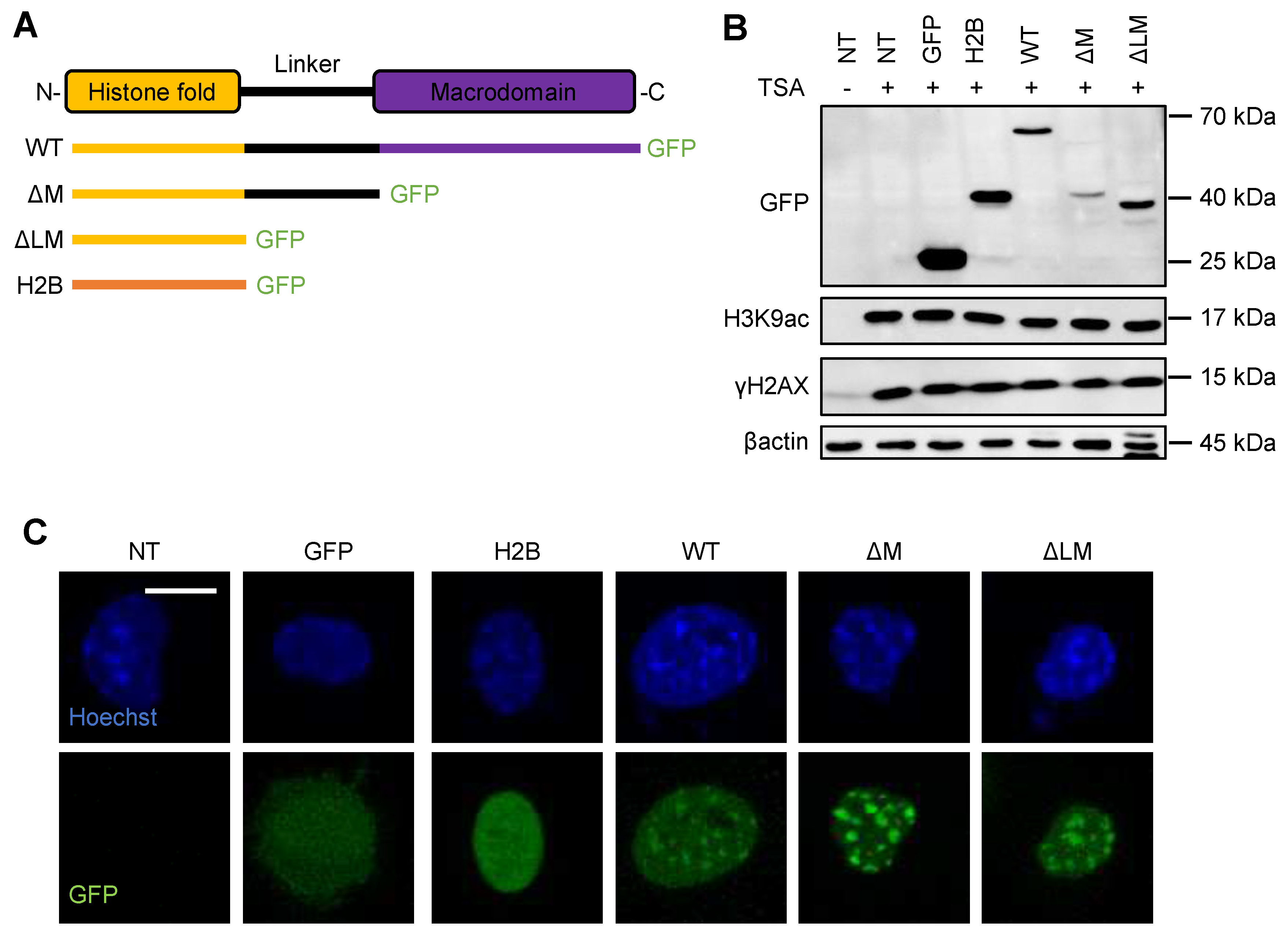

3.6. The “H2A-like” domain of mH2A1 is sufficient to recruit mH2A1 proteins to pericentric heterochromatin.

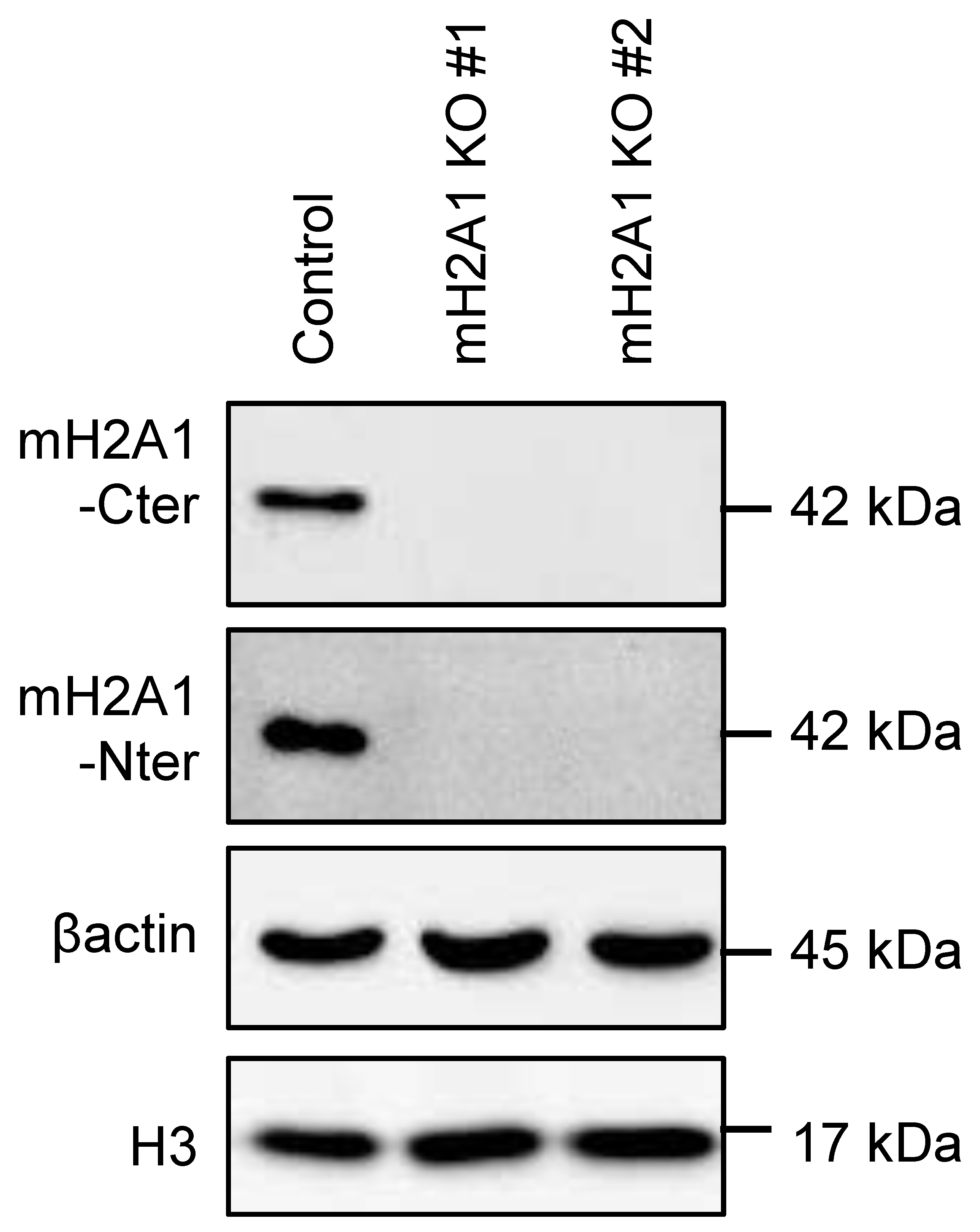

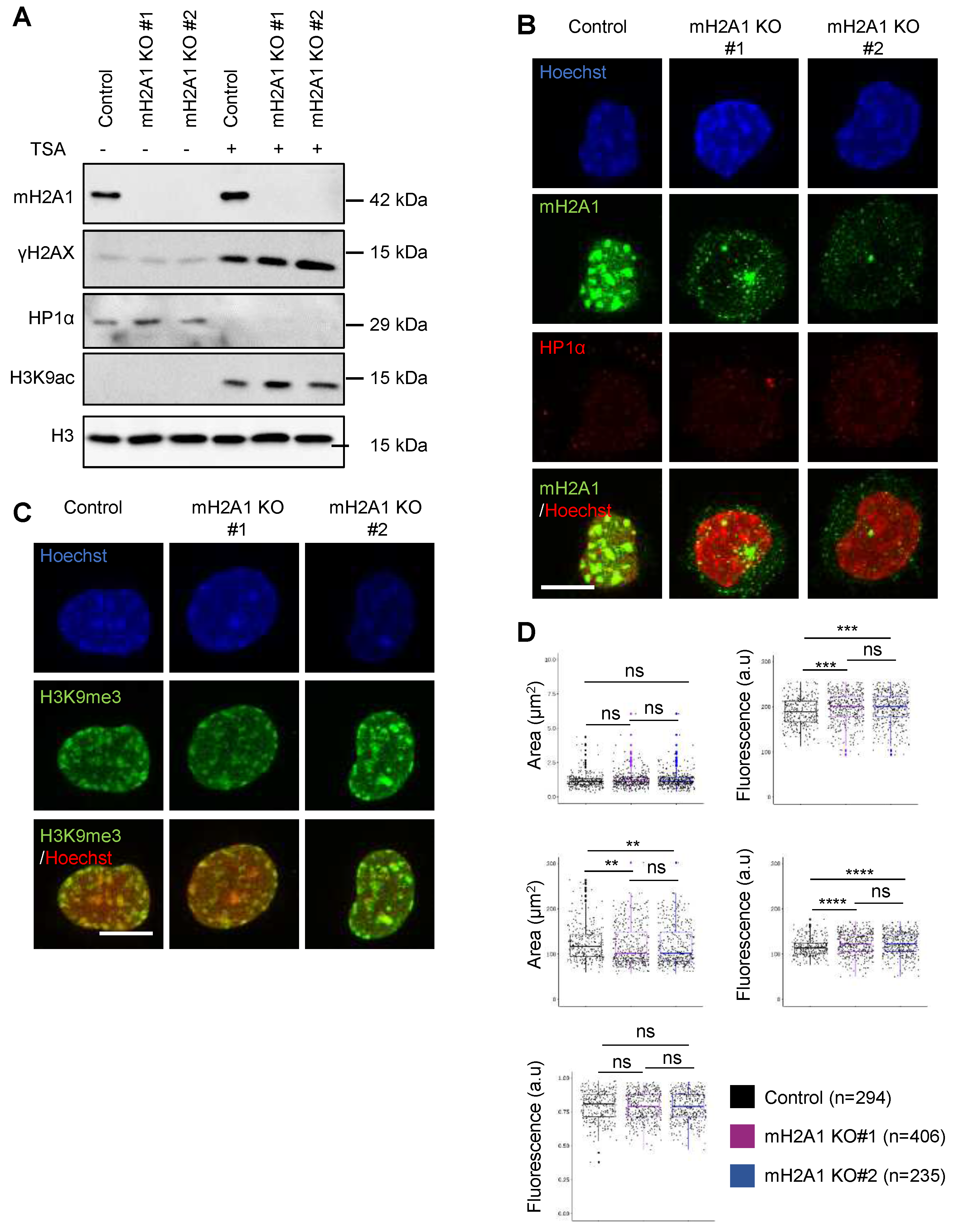

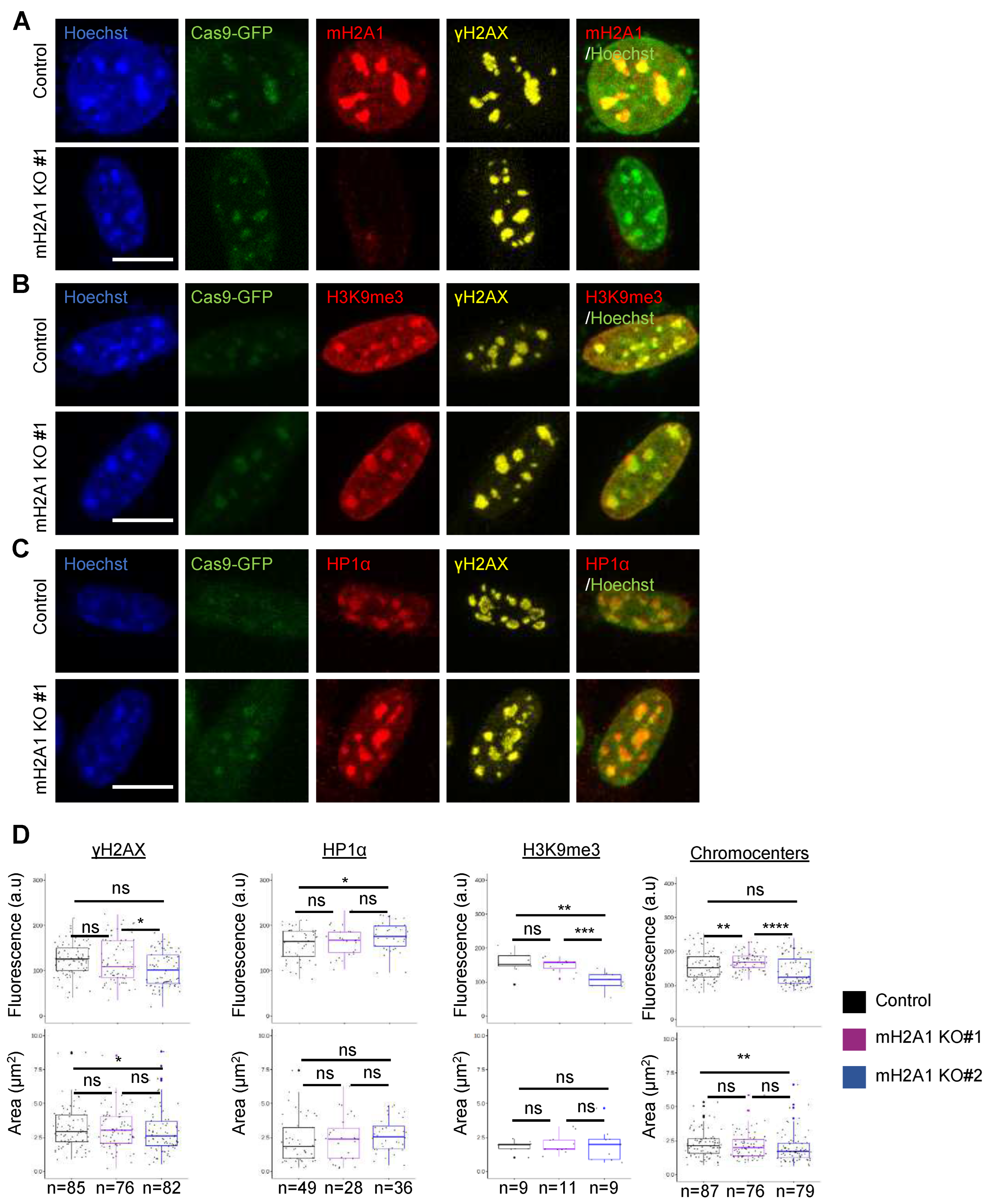

3.7. mH2A1 is not required for pericentric heterochromatin organization.

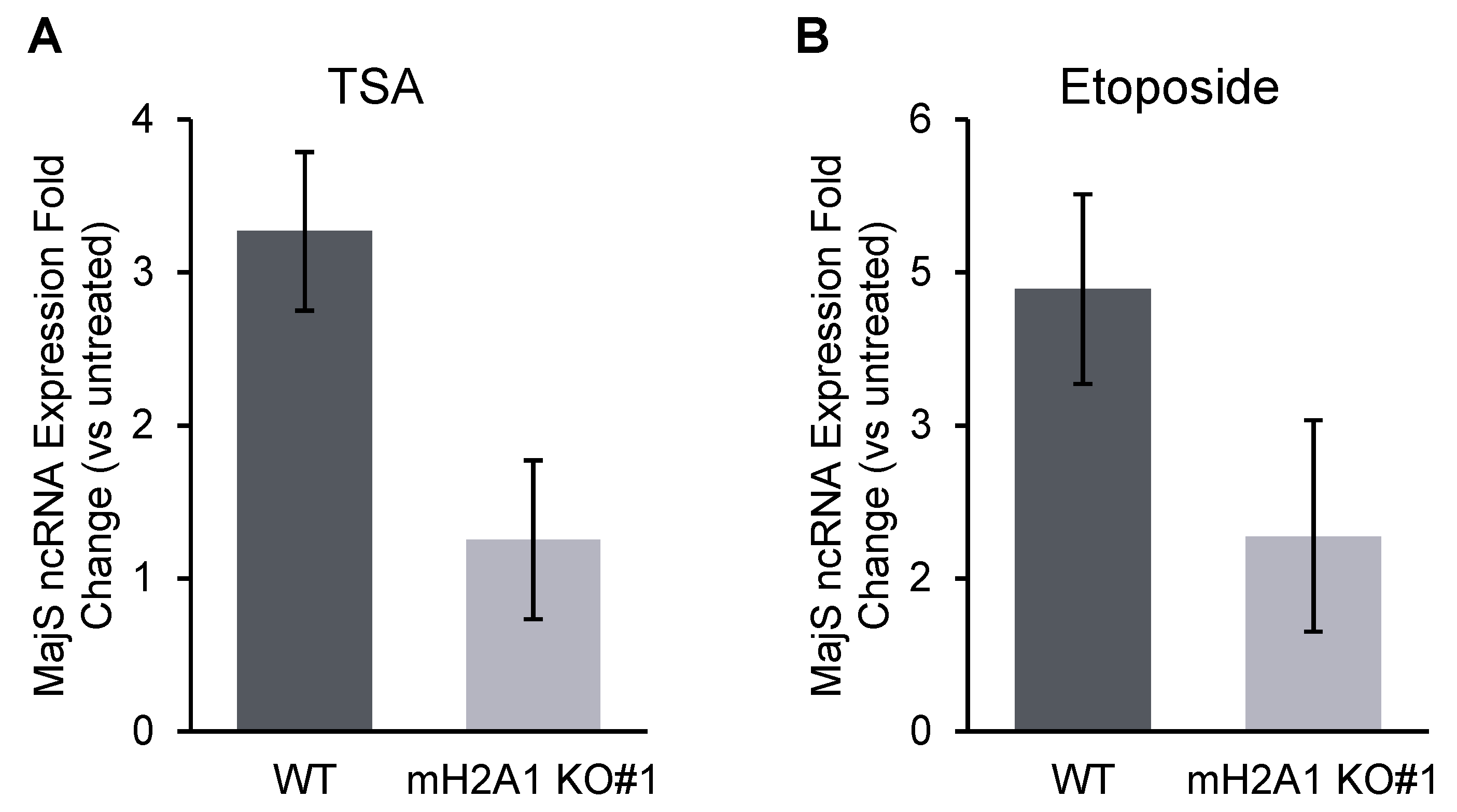

3.8. mH2A1 regulates pericentromeric RNA transcription.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

Appendix A.5

Appendix A.6

Appendix A.7

Appendix A.8

Appendix A.9

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

| gRNAs | gRNA Sequence | PAM |

|---|---|---|

| gRNA 1 | ATTCGGCAACACGCCCCCGC | TGG |

| gRNA 2 | CACGCCTCCGCCGGCCAAAA | AGG |

| Cas9 | pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (PX459) V2.0 (Plasmid #62988, addgene) |

| Cas9-GFP | pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) (Plasmid #48138, addgene) |

| Cas9_gRNA1 | pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro gRNA 1 ex4 H2AFY MS |

| Cas9-GFP_gRNA2 | pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) gRNA 2 ex4 H2AFY Ms |

| MajS gRNA | pEX-A-U6-MaSgRNA_Puro_R (Plasmid #84780,addgene) |

| MinS gRNA | pEX-A-U6-MiSgRNA_Puro_R (Plasmid #84781,addgene) |

| Telo gRNA | pEX-A-U6-TelgRNA_Puro_R (Plasmid #84782,addgene) |

| EGFP | pLVX-EGFP |

| EGFP-mH2A1.1 | pLVX-EGFP-mH2A1.1 |

| EGFP-mH2A1 delMD (aa1-179) | pLVX-EGFP-mH2A1 delMD (aa1-179) |

| EGFP-mH2A1 delLMD (aa1-123) | pLVX-EGFP-mH2A1 delLMD (aa1-123) |

| H2B-EGFP | pBOS-H2B-GFP (BD Pharmingen) |

| Flag-mH2A1.1 | Given by Marcus Buschbeck |

| Flag-mH2A1.2 | Given by Marcus Buschbeck |

| dCas9-VPR | Given by Fabian Erdel [40] |

| siRNA | Sequence |

|---|---|

| HIRA (5’ -> 3’) | GGAGAUGACAAACUGAUUAUU |

| Target | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| 18S rDNA | CCCTATCAACTTTCGATGGTAGTCG | CCAATGGATCCTCGTTAAAGGATTT |

| ANKRD1 | AGTAGAGGAACTGGTCACTGG | TGGGCTAGAAGTGTCTTCAGAT |

| CDKN1A (p21) | GACACCACTGGAGGGTGACT | CAGGTCCACATGGTCTTCCT |

| CXCL1 | GAAAGCTTGCCTCAATCCTG | CACCAGTGAGCTTCCTCCTC |

| EDN1 | CAGCAGTCTTAGGCGCTGAG | ACTCTTTATCCATCAGGGACGAG |

| IL6 | CCGGGAACGAAAGAGAAGCT | GCGCTTGTGGAGAAGGAGTT |

| IL8 | CTTTCCACCCCAAATTTATCAAAG | CAGACAGAGCTCTCTTCCATCAGA |

| MajS | GACGACTTGAAAAATGACGAAATC | CATATTCCAGGTCCTTCAGTGTGC |

| GAPDH | AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG | ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA |

| gRNA 1 | CACCGATTCGGCAACACGCCCCCGC | AAACGCGGGGGCGTGTTGCCGAAT |

| gRNA 2 | CACCGCACGCCTCCGCCGGCCAAAA | AAACTTTTGGCCGGCGGAGGCGTG |

| Antibody | Supplier (reference) | Dilution (Use)* |

|---|---|---|

| HIRA | Cell signaling (D2A5E) | 1/1000 (WB) |

| H2AX | Abcam Ab26350 [9F3] | 1/1000 (WB & IF) |

| H2AX | Abcam Ab81299 | 1/1000 (IF) |

| mH2A1.2 | Millipore #MABE61 Clone 14GT | 1/1000 |

| mH2A1 | Millipore #AbE215 | 1/1000 (WB & IF) |

| H3K9me3 | Abcam Ab8898 | 1/1000 (IF) |

| H3K9me3 | Abcam (Ab1991) | 1/1000 (WB) |

| Flag | Sigma (F3165) M2 | 1/1000 (WB & IF) |

| actin | Abcam (Ab8227) | 1/1000 (WB) |

| HP1 | Upstate #05-689 | 1/1000 (WB & IF) |

| H3K9ac | Upstate #06-942 | 1/1000 (WB) |

| LaminB1 | Abcam Ab16048 | 1/1000 (WB) |

| GFP | Roche 1814460001 | 1/1000 (WB) |

| mH2A1-Nter | Abcam (Ab137117) | 1/1000 (IF) |

| mH2A1.1 | Ab mH2A1.1 Home-made | 1/1000 (IF) |

| Anti-mouse-Peroxidase | Sigma A2304 | 1:10.000 (WB) |

| Anti-Rabbit-Peroxidase | Sigma A0545 | 1:10.000 (WB) |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Anti-mouse | Invitrogen A11029 | 1:1000 (IF) |

| Alexa Fluor 647 Anti-Rabbit | Invitrogen A21245 | 1:1000 (IF) |

References

- Ferrand, J.; Rondinelli, B.; Polo, S.E. Histone Variants: Guardians of Genome Integrity. Cells 2020, 9, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, S.; Banaszynski, L.A. The roles of histone variants in fine-tuning chromatin organization and function. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2020, 21, 522–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschbeck, M.; Hake, S.B. Variants of core histones and their roles in cell fate decisions, development and cancer 2017. 18, 299–314. [CrossRef]

- Pehrson, J.R.; Fuji, R.N. Evolutionary conservation of histone macroH2A subtypes and domains. Nucleic Acids Research 1998, 26, 2837–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Casas, C.; Gonzalez-Romero, R.; Cheema, M.S.; Ausió, J.; Eirín-López, J.M. The characterization of macroH2A beyond vertebrates supports an ancestral origin and conserved role for histone variants in chromatin. Epigenetics 2016, 11, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamble, M.J.; Kraus, W.L. Multiple facets of the unique histone variant macroH2A: From genomics to cell biology 2010. 9, 2568–74. [CrossRef]

- Costanzi, C.; Pehrson, J.R. Histone macroH2A1 is concentrated in the inactive X chromosome of female mammals. Nature 1998, 393, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galupa, R.; Heard, E. X-chromosome inactivation: A crossroads between chromosome architecture and gene regulation 2018. 52, 535–566. [CrossRef]

- Gamble, M.J.; Frizzell, K.M.; Yang, C.; Krishnakumar, R.; Kraus, W.L. The histone variant macroH2A1 marks repressed autosomal chromatin, but protects a subset of its target genes from silencing. Genes and Development 2010, 24, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recoules, L.; Heurteau, A.; Raynal, F.; Karasu, N.; Moutahir, F.; Bejjani, F.; Jariel-Encontre, I.; Cuvier, O.; Sexton, T.; Lavigne, A.C.; Bystricky, K. The histone variant macroH2A1.1 regulates RNA polymerase II-paused genes within defined chromatin interaction landscapes. Journal of cell science 2022, 135, jcs259456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Filipescu, D.; Andrade, J.; Gaspar-Maia, A.; Ueberheide, B.; Bernstein, E. Transcription-associated histone pruning demarcates macroH2A chromatin domains. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology 2018, 25, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douet, J.; Corujo, D.; Malinverni, R.; Renauld, J.; Sansoni, V.; Marjanović, M.P.; Cantariño, N.; Valero, V.; Mongelard, F.; Bouvet, P.; Imhof, A.; Thiry, M.; Buschbeck, M. MacroH2A histone variants maintain nuclear organization and heterochromatin architecture. Journal of Cell Science 2017, 130, 1570–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.; Das, S.; Douet, J.; Wong, J.; Buschbeck, M.; Mongelard, F.; Bouvet, P. MacroH2A1 histone variant represses rDNA transcription. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Poustovoitov, M.V.; Ye, X.; Santos, H.A.; Chen, W.; Daganzo, S.M.; Erzberger, J.P.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Canutescu, A.A.; Dunbrack, R.L.; Pehrson, J.R.; Berger, J.M.; Kaufman, P.D.; Adams, P.D. Formation of macroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Developmental Cell 2005, 8, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, T.; Kirschner, K.; Thuret, J.Y.; Pope, B.D.; Ryba, T.; Newman, S.; Ahmed, K.; Samarajiwa, S.A.; Salama, R.; Carroll, T.; Stark, R.; Janky, R.S.; Narita, M.; Xue, L.; Chicas, A.; Nũnez, S.; Janknecht, R.; Hayashi-Takanaka, Y.; Wilson, M.D.; Marshall, A.; Odom, D.T.; Babu, M.M.; Bazett-Jones, D.P.; Tavaré, S.; Edwards, P.A.W.; Lowe, S.W.; Kimura, H.; Gilbert, D.M.; Narita, M. Independence of Repressive Histone Marks and Chromatin Compaction during Senescent Heterochromatic Layer Formation. Molecular Cell 2012, 47, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, M.; Nũnez, S.; Heard, E.; Narita, M.; Lin, A.W.; Hearn, S.A.; Spector, D.L.; Hannon, G.J.; Lowe, S.W. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 2003, 113, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryev, S.A.; Nikitina, T.; Pehrson, J.R.; Singh, P.B.; Woodcock, C.L. Dynamic relocation of epigenetic chromatin markers reveals an active role of constitutive heterochromatin in the transition from proliferation to quiescence. Journal of Cell Science 2004, 117, 6153–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, S.t.; Chen, W.; Bonner, M.; Pehrson, J.; Yen, T.J.; Adams, P.D. HP1 Proteins Are Essential for a Dynamic Nuclear Response That Rescues the Function of Perturbed Heterochromatin in Primary Human Cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2007, 27, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changolkar, L.N.; Singh, G.; Cui, K.; Berletch, J.B.; Zhao, K.; Disteche, C.M.; Pehrson, J.R. Genome-Wide Distribution of MacroH2A1 Histone Variants in Mouse Liver Chromatin. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2010, 30, 5473–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermoud, J.E.; Costanzi, C.; Pehrson, J.R.; Brockdorff, N. Histone macroH2A1.2 relocates to the inactive X chromosome after initiation and propagation of X-inactivation. Journal of Cell Biology 1999, 147, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasque, V.; Gillich, A.; Garrett, N.; Gurdon, J.B. Histone variant macroH2A confers resistance to nuclear reprogramming. EMBO Journal 2011, 30, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perche, P.Y.; Vourc’h, C.; Konecny, L.; Souchier, C.; Robert-Nicoud, M.; Dimitrov, S.; Khochbin, S. Higher concentrations of histone macroH2A in the Barr body are correlated with higher nucleosome density. Current Biology 2000, 10, 1531–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Muñoz, I.; Lund, A.H.; Van Der Stoop, P.; Boutsma, E.; Muijrers, I.; Verhoeven, E.; Nusinow, D.A.; Panning, B.; Marahrens, Y.; Van Lohuizen, M. Stable X chromosome inactivation involves the PRC1 Polycomb complex and requires histone MACROH2A1 and the CULLIN3/SPOP ubiquitin E3 ligase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 7635–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ruiz, P.D.; Novikov, L.; Casill, A.D.; Park, J.W.; Gamble, M.J. MacroH2A1.1 and PARP-1 cooperate to regulate transcription by promoting CBP-mediated H2B acetylation. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology 2014, 21, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Orso, S.; Wang, A.H.; Shih, H.Y.; Saso, K.; Berghella, L.; Gutierrez-Cruz, G.; Ladurner, A.G.; O’Shea, J.J.; Sartorelli, V.; Zare, H. The Histone Variant MacroH2A1.2 Is Necessary for the Activation of Muscle Enhancers and Recruitment of the Transcription Factor Pbx1. Cell Reports 2016, 14, 1156–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar-Maia, A.; Qadeer, Z.A.; Hasson, D.; Ratnakumar, K.; Adrian Leu, N.; Leroy, G.; Liu, S.; Costanzi, C.; Valle-Garcia, D.; Schaniel, C.; Lemischka, I.; Garcia, B.; Pehrson, J.R.; Bernstein, E. MacroH2A histone variants act as a barrier upon reprogramming towards pluripotency. Nature Communications 2013, 4, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Torres, B.; Estepa-Fernández, A.; Rovira, M.; Orzáez, M.; Serrano, M.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Sancenón, F. The chemistry of senescence 2019, 3, 426–441. [CrossRef]

- Nagano, T.; Nakano, M.; Nakashima, A.; Onishi, K.; Yamao, S.; Enari, M.; Kikkawa, U.; Kamada, S. Identification of cellular senescence-specific genes by comparative transcriptomics. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 31758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, C.J.; Lin, A.; Girish, V.; Sheltzer, J.M. Generating Single Cell–Derived Knockout Clones in Mammalian Cells with CRISPR/Cas9. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology 2019, 128, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Yang, P.C. Western blot: Technique, theory, and trouble shooting. North American Journal of Medical Sciences 2012, 4, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumagalli, M.; Rossiello, F.; Mondello, C.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Stable cellular senescence is associated with persistent DDR activation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e11096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Nehme, J.; Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence 2018. 28, 436–453. [CrossRef]

- Chiolo, I.; Minoda, A.; Colmenares, S.U.; Polyzos, A.; Costes, S.V.; Karpen, G.H. Double-strand breaks in heterochromatin move outside of a dynamic HP1a domain to complete recombinational repair. Cell 2011, 144, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, T.; Spatola, B.; Delabaere, L.; Bowlin, K.; Hopp, H.; Kunitake, R.; Karpen, G.H.; Chiolo, I. Heterochromatic breaks move to the nuclear periphery to continue recombinational repair. Nature cell biology 2015, 17, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouroula, K.; Furst, A.; Rogier, M.; Heyer, V.; Maglott-Roth, A.; Ferrand, A.; Reina-San-Martin, B.; Soutoglou, E. Temporal and Spatial Uncoupling of DNA Double Strand Break Repair Pathways within Mammalian Heterochromatin. Molecular Cell 2016, 63, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, T.; Bultmann, S.; Leonhardt, H.; Markaki, Y. Visualization of specific DNA sequences in living mouse embryonic stem cells with a programmable fluorescent CRISPR/Cas system. Nucleus 2014, 5, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Tyler, J.K. Nucleosome disassembly during human non-homologous end joining followed by concerted HIRA- and CAF-1-dependent reassembly. eLife 2016, 5, e15129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noren Hooten, N.; Evans, M.K. Techniques to induce and quantify cellular senescence. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2017, May 1, 55533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, A.; Scheiman, J.; Vora, S.; Pruitt, B.W.; Tuttle, M.; P R Iyer, E.; Lin, S.; Kiani, S.; Guzman, C.D.; Wiegand, D.J.; Ter-Ovanesyan, D.; Braff, J.L.; Davidsohn, N.; Housden, B.E.; Perrimon, N.; Weiss, R.; Aach, J.; Collins, J.J.; Church, G.M. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated transcriptional programming. Nature Methods 2015, 12, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdel, F.; Rademacher, A.; Vlijm, R.; Tünnermann, J.; Frank, L.; Weinmann, R.; Schweigert, E.; Yserentant, K.; Hummert, J.; Bauer, C.; Schumacher, S.; Al Alwash, A.; Normand, C.; Herten, D.P.; Engelhardt, J.; Rippe, K. Mouse Heterochromatin Adopts Digital Compaction States without Showing Hallmarks of HP1-Driven Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. Molecular Cell 2020, 78, 236–249.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changolkar, L.N.; Costanzi, C.; Leu, N.A.; Chen, D.; McLaughlin, K.J.; Pehrson, J.R. Developmental Changes in Histone macroH2A1-Mediated Gene Regulation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2007, 27, 2758–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasijevic, B.; Rasmussen, T.P. X Chromosome Inactivation and Differentiation Occur Readily in ES Cells Doubly-Deficient for MacroH2A1 and MacroH2A2. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.L.; McBryan, T.; Enders, G.H.; Johnson, F.B.; Zhang, R.; Adams, P.D. Senescent mouse cells fail to overtly regulate the HIRA histone chaperone and do not form robust Senescence Associated Heterochromatin Foci. Cell Division 2010, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlova, N.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Hajduch, M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs 2022. 23, 4168. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.C.; Manning, B.; Zhang, H.; Lawrence, J.B. Higher-order unfolding of satellite heterochromatin is a consistent and early event in cell senescence. Journal of Cell Biology 2013, 203, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouaire, T.; Rocher, V.; Lashgari, A.; Arnould, C.; Aguirrebengoa, M.; Biernacka, A.; Skrzypczak, M.; Aymard, F.; Fongang, B.; Dojer, N.; Iacovoni, J.S.; Rowicka, M.; Ginalski, K.; Côté, J.; Legube, G. Comprehensive Mapping of Histone Modifications at DNA Double-Strand Breaks Deciphers Repair Pathway Chromatin Signatures. Molecular Cell 2018, 72, 250–262.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassa, P.O.; Hothorn, M.; Kustatscher, G.; Nijmeijer, B. A macrodomain-containing histone rearranges chromatin upon sensing PARP1 activation. Nature Structural Molecular Biology 2009, 16, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S.; Kruhlak, M.J.; Kim, J.; Tran, A.D.; Liu, J.; Nyswaner, K.; Shi, L.; Jailwala, P.; Sung, M.H.; Hakim, O.; Oberdoerffer, P. A macrohistone variant links dynamic chromatin compaction to BRCA1-dependent genome maintenance. Cell Reports 2014, 8, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Sturgill, D.; Sebastian, R.; Khurana, S.; Tran, A.D.; Edwards, G.B.; Kruswick, A.; Burkett, S.; Hosogane, E.K.; Hannon, W.W.; Weyemi, U.; Bonner, W.M.; Luger, K.; Oberdoerffer, P. Replication Stress Shapes a Protective Chromatin Environment across Fragile Genomic Regions. Molecular Cell 2018, 69, 36–47.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, P.V.; Ahel, D.; Ryan, D.P.; Weston, R.; Wiechens, N.; Kraehenbuehl, R.; Owen-Hughes, T.; Ahel, I. DNA repair factor APLF Is a histone chaperone. Molecular Cell 2011, 41, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; Gursoy-Yuzugullu, O.; Price, B.D. The histone variant macroH2A1.1 is recruited to DSBs through a mechanism involving PARP1. FEBS Letters 2012, 586, 3920–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gilbert, D.M. Proliferation-dependent and cell cycle regulated transcription of mouse pericentric heterochromatin. The Journal of cell biology 2007, 179, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, A.V.; Okamoto, I.; Casanova, M.; El Marjou, F.; Le Baccon, P.; Almouzni, G. A strand-specific burst in transcription of pericentric satellites is required for chromocenter formation and early mouse development. Developmental cell 2010, 19, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgardsdottir, R.; Chiodi, I.; Giordano, M.; Rossi, A.; Bazzini, S.; Ghigna, C.; Riva, S.; Biamonti, G. Transcription of Satellite III non-coding RNAs is a general stress response in human cells. Nucleic acids research 2008, 36, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.T.; Lipson, D.; Paul, S.; Brannigan, B.W.; Akhavanfard, S.; Coffman, E.J.; Contino, G.; Deshpande, V.; Iafrate, A.J.; Letovsky, S.; Rivera, M.N.; Bardeesy, N.; Maheswaran, S.; Haber, D.A. Aberrant overexpression of satellite repeats in pancreatic and other epithelial cancers. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2011, 331, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, E.; Bayne, E.H.; Allshire, R.C. On the connection between RNAi and heterochromatin at centromeres. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 2010, 75, 275–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).