Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

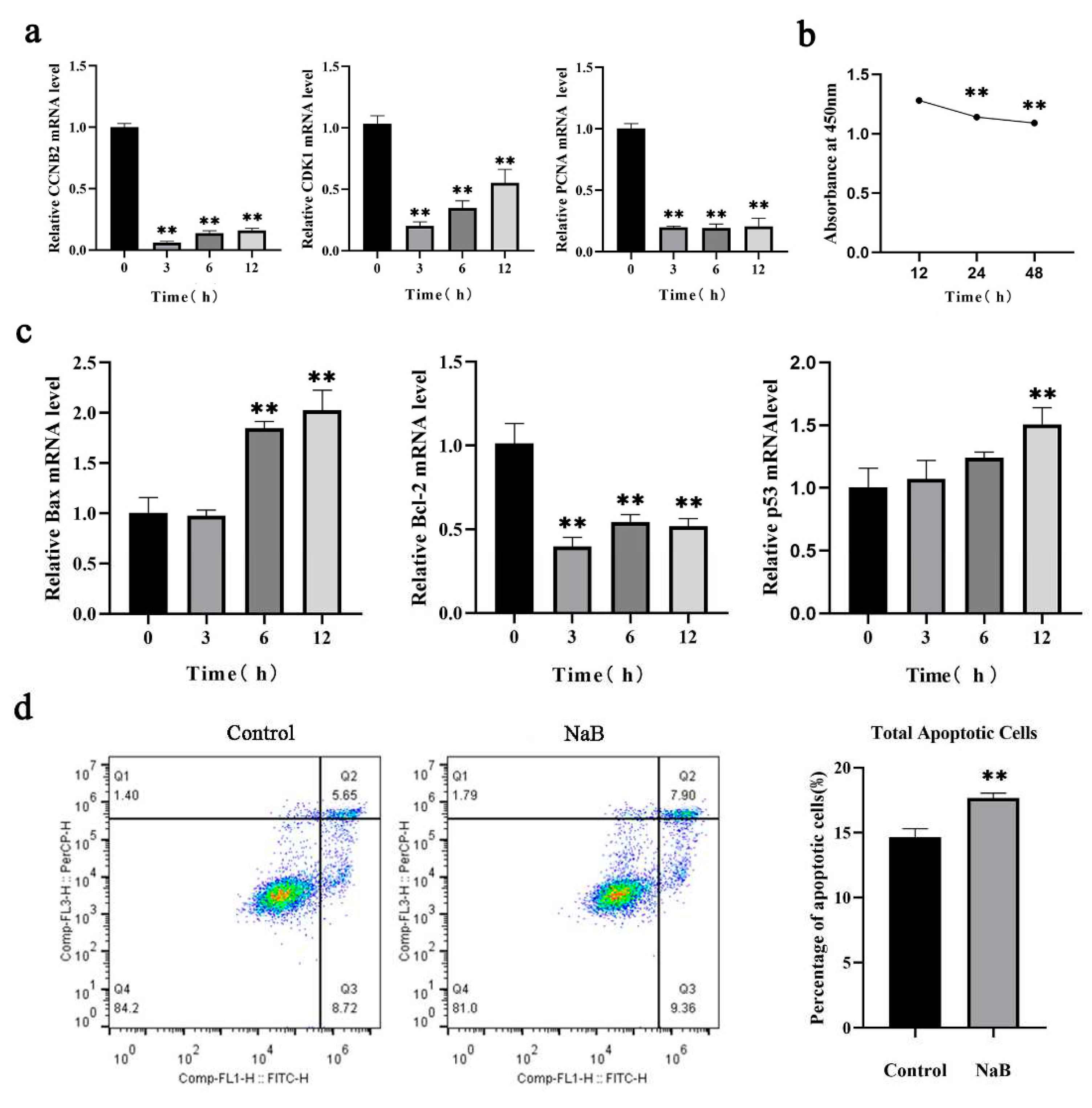

2.1. NaB inhibits BSCs proliferation and promotes apoptosis

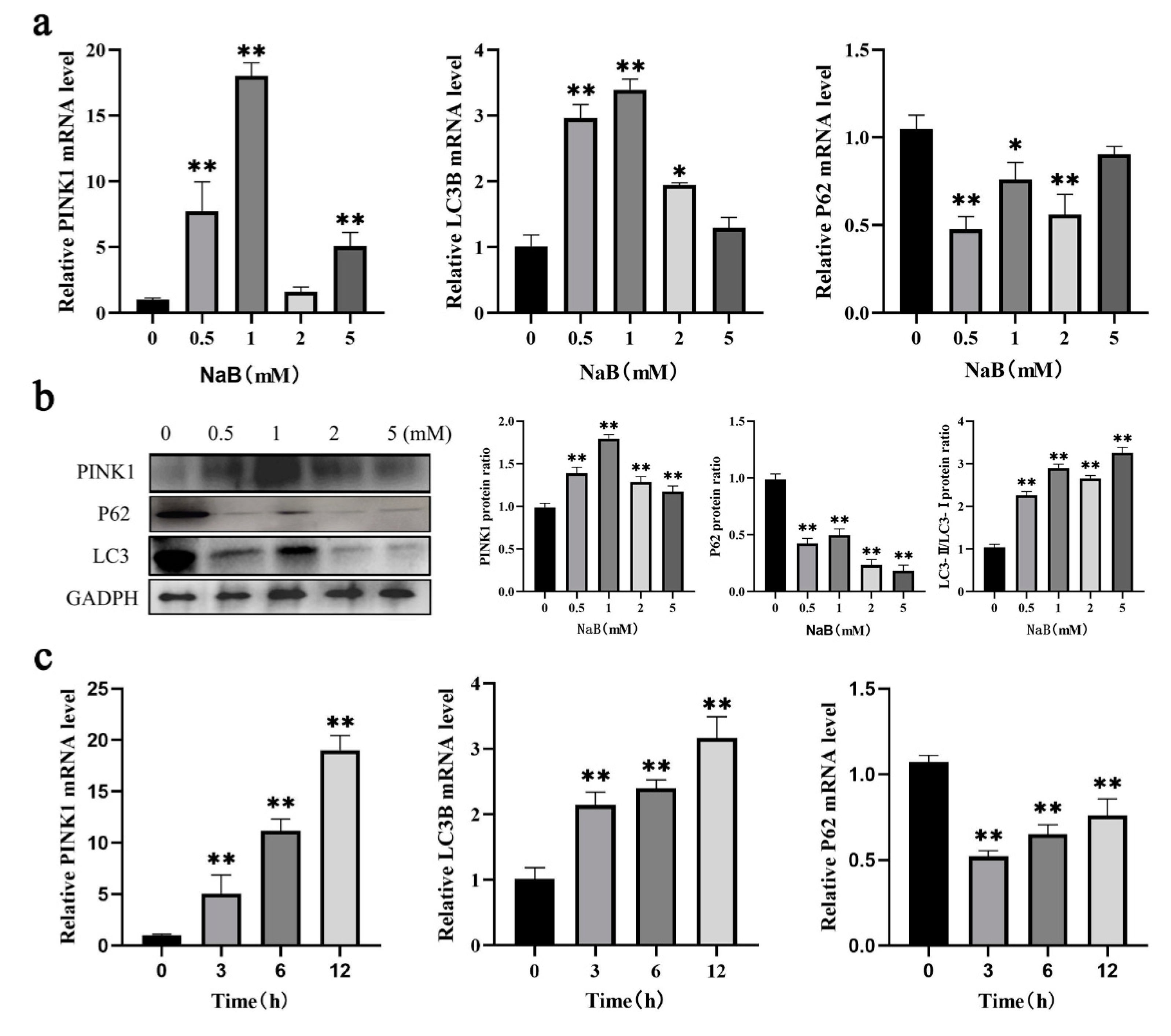

2.2. NaB promotes mitophagy in BSCs

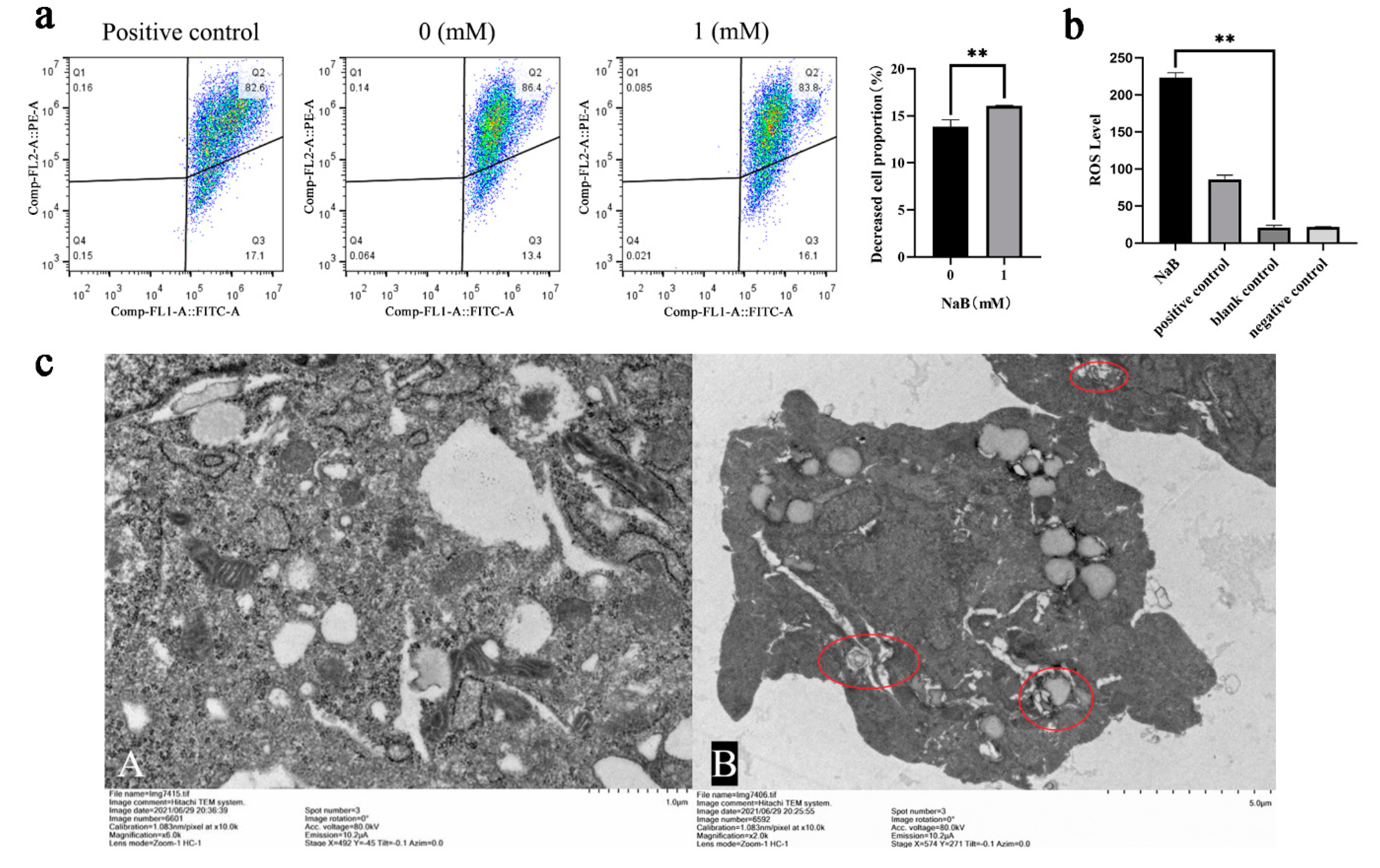

2.3. NaB induces ROS/MMP response in mitochondria

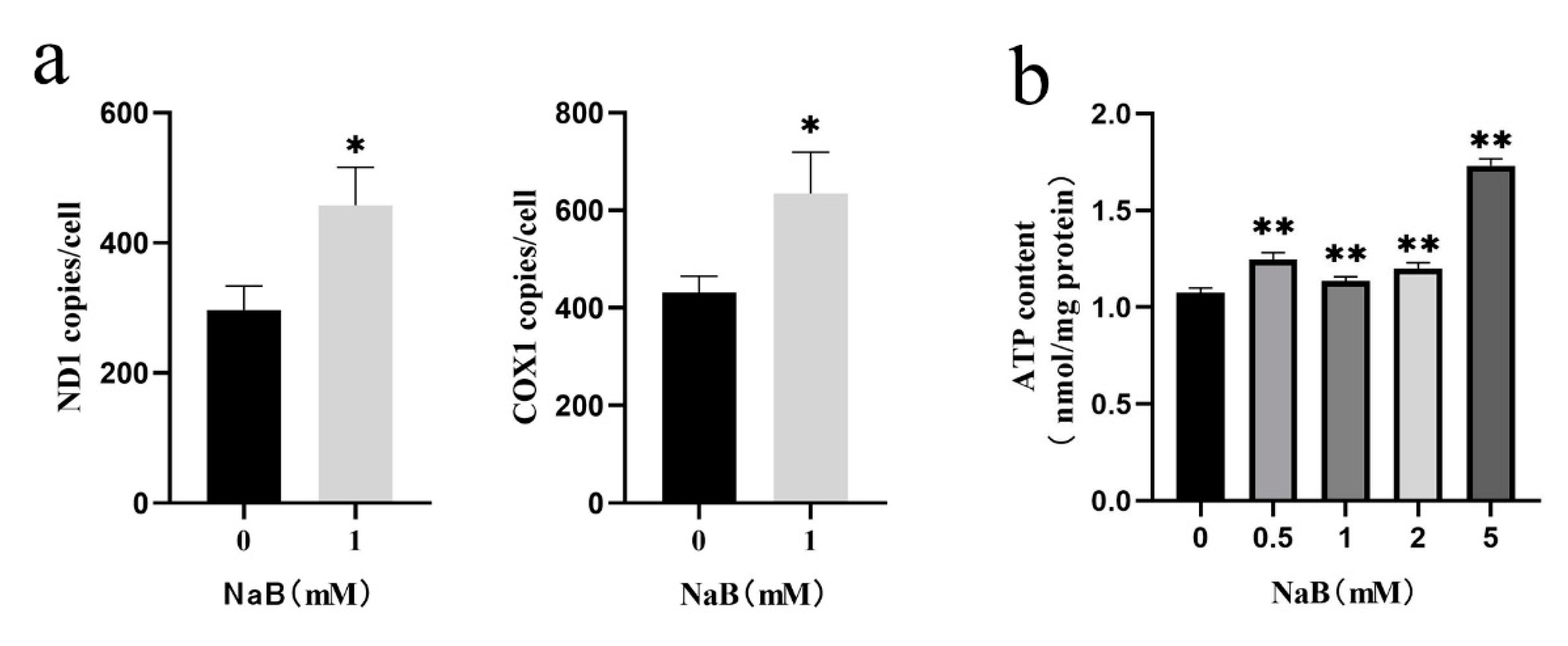

2.4. NaB promotes mtDNA copy number

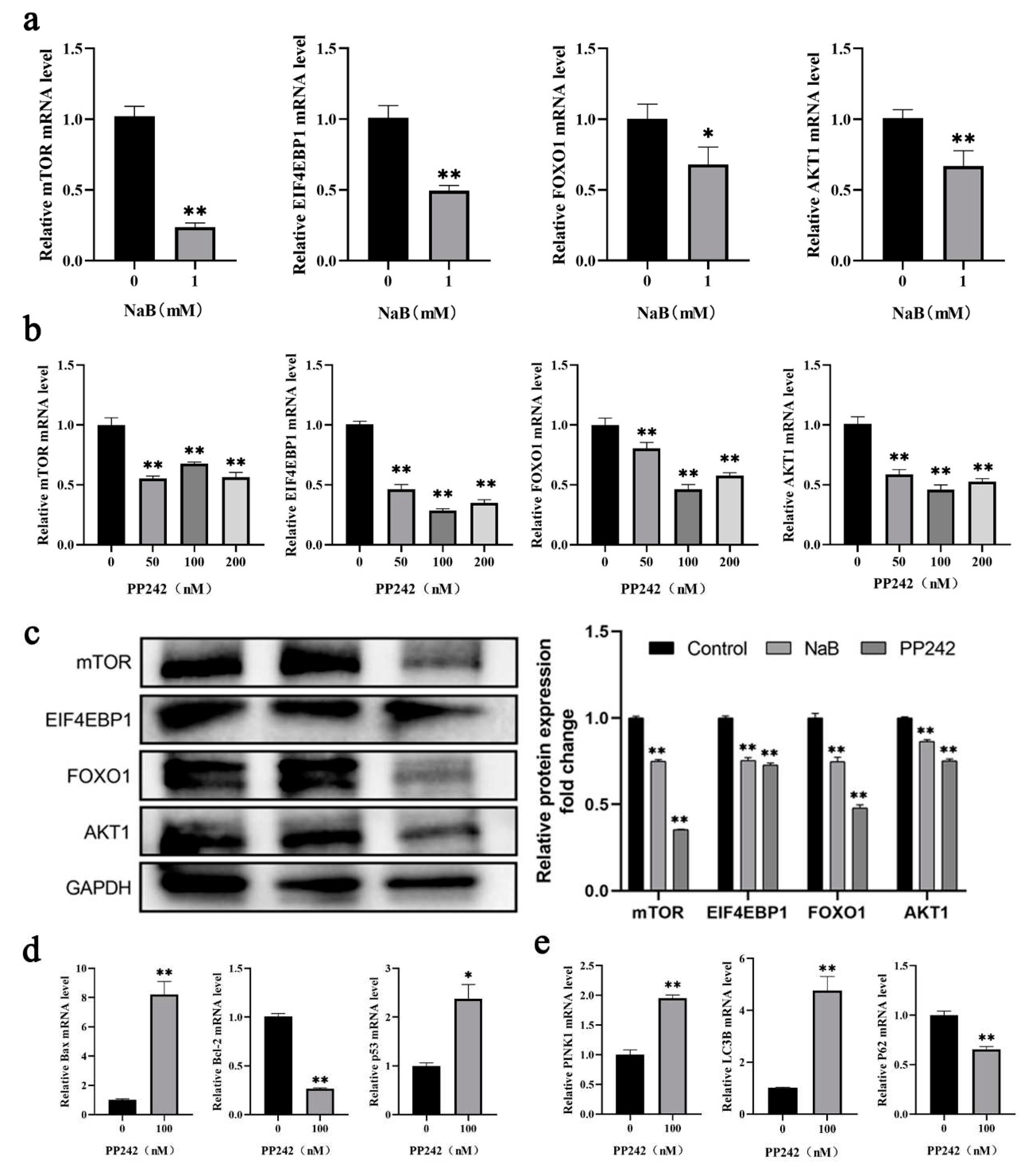

2.5. NaB mediated mTOR signaling pathway promotes mitophagy and apoptosis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and antibodies

4.2. Cell culture

4.3. Cell viability assay

4.4. Cell apoptosis assay

4.5. Assay of mitophagy and ROS

4.6. MMP assay

4.7. Mitophagy vesicles assay

4.9. ATP content assays

4.10. Effect of mTOR signaling pathway on mitophagy and apoptosis

4.11. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falkenberg, K.J.; Johnstone, R.W. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, K.Y.; Cosgrove, L.; Lockett, T.; Head, R.; Topping, D.L. A review of the potential mechanisms for the lowering of colorectal oncogenesis by butyrate. Br J Nutr 2012, 108, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ma, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, R. Evaluating the Activity of Sodium Butyrate to Prevent Osteoporosis in Rats by Promoting Osteal GSK-3beta/Nrf2 Signaling and Mitochondrial Function. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 6588–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, W.; Xiao, C.; Yang, W.; Qin, Q.; Mao, A.; Tan, Q.; Lian, B.; Wei, C. Sodium Butyrate Combined with Docetaxel for the Treatment of Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells by Targeting Gli1. Onco Targets Ther 2020, 13, 8861–8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Lei, K.; Shan, Z.; Zhao, C.; Ning, Y.; Gong, R.; Ren, H.; Cui, Z. Synergistic effects of sodium butyrate and cisplatin against cervical carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 999667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenlicht, L.; Shi, L.; Mariadason, J.; Laboisse, C.; Velcich, A. Repression of MUC2 gene expression by butyrate, a physiological regulator of intestinal cell maturation. Oncogene 2003, 22, 4983–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschiero, C.; Gao, Y.; Baldwin RLt Ma, L.; Li, C.J.; Liu, G.E. Butyrate Induces Modifications of the CTCF-Binding Landscape in Cattle Cells. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.W.; Li, C. Butyrate induces profound changes in gene expression related to multiple signal pathways in bovine kidney epithelial cells. BMC Genomics 2006, 7, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Kang, X.; Lin, S.; Li, B.; Connor, E.E.; Baldwin RLt Tenesa, A.; Ma, L.; et al. Functional annotation of the cattle genome through systematic discovery and characterization of chromatin states and butyrate-induced variations. BMC Biol 2019, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Liu, S.; Fang, L.; Lin, S.; Liu, M.; Baldwin, R.L.; Liu, G.E.; Li, C.J. Data of epigenomic profiling of histone marks and CTCF binding sites in bovine rumen epithelial primary cells before and after butyrate treatment. Data Brief 2020, 28, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Qu, Y.; Liu, S.; Guo, Y.; Fu, S.; Liu, J. Sodium butyrate promotes milk fat synthesis in bovine mammary epithelial cells via GPR41 and its downstream signalling pathways. Life Sci 2020, 259, 118375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.M.; Vandehaar, M.J.; Sordillo, L.M.; Catherman, D.R.; Bateman, H.G., 2nd; Schlotterbeck, R.L. Fatty acid intake alters growth and immunity in milk-fed calves. J Dairy Sci 2011, 94, 3936–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guller, I.; Russell, A.P. MicroRNAs in skeletal muscle. their role and regulation in development, disease and function. J Physiol 2010, 588, 4075–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, M.; Festa, A.; Falco, M.; Lombardi, A.; Luce, A.; Grimaldi, A.; Zappavigna, S.; Sperlongano, P.; Irace, C.; Caraglia, M.; et al. Mitochondria as playmakers of apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 98, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Dmitriev, A.A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Kardymon, O.L.; Sadritdinova, A.F.; Fedorova, M.S.; Pokrovsky, A.V.; Melnikova, N.V.; Kaprin, A.D.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in aging and cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 44879–44905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holczer, M.; Besze, B.; Zambo, V.; Csala, M.; Banhegyi, G.; Kapuy, O. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) Promotes Autophagy-Dependent Survival via Influencing the Balance of mTOR-AMPK Pathways upon Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018, 6721530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowosad, A.; Jeannot, P.; Callot, C.; Creff, J.; Perchey, R.T.; Joffre, C.; Codogno, P.; Manenti, S.; Besson, A. Publisher Correction. p27 controls Ragulator and mTOR activity in amino acid-deprived cells to regulate the autophagy-lysosomal pathway and coordinate cell cycle and cell growth. Nat Cell Biol 2021, 23, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Bai, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jia, W.; et al. Antrodin C, an NADPH Dependent Metabolism, Encourages Crosstalk between Autophagy and Apoptosis in Lung Carcinoma Cells by Use of an AMPK Inhibition-Independent Blockade of the Akt/mTOR Pathway. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henagan, T.M.; Stefanska, B.; Fang, Z.; Navard, A.M.; Ye, J.; Lenard, N.R.; Devarshi, P.P. Sodium butyrate epigenetically modulates high-fat diet-induced skeletal muscle mitochondrial adaptation, obesity and insulin resistance through nucleosome positioning. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172, 2782–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claflin, D.R.; Jackson, M.J.; Brooks, S.V. Age affects the contraction-induced mitochondrial redox response in skeletal muscle. Front Physiol 2015, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Gong, Q.; Ma, H.; Kan, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, S. Butyrate alleviates oxidative stress by regulating NRF2 nuclear accumulation and H3K9/14 acetylation via GPR109A in bovine mammary epithelial cells and mammary glands. Free Radic Biol Med 2020, 152, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, V.; Shahsavari, Z.; Safizadeh, B.; Hosseini, A.; Khademian, N.; Tavakoli-Yaraki, M. Sodium butyrate promotes apoptosis in breast cancer cells through reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and mitochondrial impairment. Lipids Health Dis 2017, 16, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerdt, B.G.; Houston, M.A.; Anthony, G.M.; Augenlicht, L.H. Mitochondrial membrane potential (delta psi(mt)) in the coordination of p53-independent proliferation and apoptosis pathways in human colonic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 1998, 58, 2869–2875. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Mao, L.; Yan, Y.; Liao, W.; Zha, L.; et al. Sodium Butyrate Inhibits Oxidative Stress and NF-kappaB/NLRP3 Activation in Dextran Sulfate Sodium Salt-Induced Colitis in Mice with Involvement of the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Mitophagy. Dig Dis Sci 2023.

- Jin, M.H.; Yu, J.B.; Sun, H.N.; Jin, Y.H.; Shen, G.N.; Jin, C.H.; Cui, Y.D.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Peroxiredoxin II Maintains the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential against Alcohol-Induced Apoptosis in HT22 Cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriens, A.; Nawrot, T.S.; Baeyens, W.; Den Hond, E.; Bruckers, L.; Covaci, A.; Croes, K.; De Craemer, S.; Govarts, E.; Lambrechts, N.; et al. Neonatal exposure to environmental pollutants and placental mitochondrial DNA content. A multi-pollutant approach. Environ Int 2017, 106, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.X.; Sun, M.; Li, X. Withaferin-A induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma U2OS cell line via generation of ROS and disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017, 21, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.Y.; Zhang, L.; Geng, Y.D.; Wang, B.; Feng, X.J.; Chen, Z.L.; Wei, W.; Jiang, L. beta-Elemene induces apoptosis and autophagy in colorectal cancer cells through regulating the ROS/AMPK/mTOR pathway. Chin J Nat Med 2022, 20, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Guan, F.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Feng, X. Macranthoside B Induces Apoptosis and Autophagy Via Reactive Oxygen Species Accumulation in Human Ovarian Cancer A2780 Cells. Nutr Cancer 2016, 68, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Qu, C.; Chen, L.; Geng, Y.; Cheng, C.; Yu, S.; Wang, D.; Yang, L.; Meng, Z.; et al. Kaempferol induces ROS-dependent apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells via TGM2-mediated Akt/mTOR signaling. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; He, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Deng, H.; Shi, X. Narciclasine induces autophagy-mediated apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2021, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semaan, J.; El-Hakim, S.; Ibrahim, J.N.; Safi, R.; Elnar, A.A.; El Boustany, C. Comparative effect of sodium butyrate and sodium propionate on proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells MCF-7. Breast Cancer 2020, 27, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.B.; Du, X.J.; Tang, L.L.; Chen, L.; Peng, H.; Guo, R.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Prognostic value of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA level during posttreatment follow-up in the patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma having undergone intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Chin J Cancer 2017, 36, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Ma, N.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Chang, G.; Loor, J.J.; Shen, X. Sodium Butyrate Supplementation Alleviates the Adaptive Response to Inflammation and Modulates Fatty Acid Metabolism in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Bovine Hepatocytes. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 6281–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, Y.; Cao, Y.; Xu, P.; Kan, X.; Guo, W.; Fu, S. Sodium butyrate attenuates bovine mammary epithelial cell injury by inhibiting the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Int Immunopharmacol 2022, 110, 109009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumori, R.; Doi, K.; Mochizuki, T.; Oikawa, S.; Gondaira, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Izumi, K. Sodium butyrate administration modulates the ruminal villus height, inflammation-related gene expression, and plasma hormones concentration in dry cows fed a high-fiber diet. Anim Sci J 2022, 93, e13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, Y.; Wu, D.; Ji, X.; Zhou, X.; Xia, D.; Yang, X. Maternal butyrate supplementation affects the lipid metabolism and fatty acid composition in the skeletal muscle of offspring piglets. Anim Nutr 2021, 7, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, S.; Galletti, M.; Zambelli, F.; Valente, S.; Ponti, F.; Tassinari, R.; Pasquinelli, G.; Galie, N.; Ventura, C. Sodium butyrate inhibits platelet-derived growth factor-induced proliferation and migration in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells through Akt inhibition. FEBS J 2013, 280, 2042–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ren, E.; Xu, R.; Su, Y. Transcriptomic Responses Induced in Muscle and Adipose Tissues of Growing Pigs by Intravenous Infusion of Sodium Butyrate. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H. Apoptosis of U937 human leukemic cells by sodium butyrate is associated with inhibition of telomerase activity. Int J Oncol 2006, 29, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wu, B.; Chen, B.; Shi, Q.; Guo, J.; Fan, Z.; Huang, Y. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells by regulation of the MDM2-p53 signaling. Onco Targets Ther 2016, 9, 4005–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Lopez-Soto, A.; Kumar, S.; Kroemer, G. Caspases Connect Cell-Death Signaling to Organismal Homeostasis. Immunity 2016, 44, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.M.M.; Towers, C.G.; Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.J.; Lei, Y.H.; Yao, N.; Wang, C.R.; Hu, N.; Ye, W.C.; Zhang, D.M.; Chen, Z.S. Autophagy and multidrug resistance in cancer. Chin J Cancer 2017, 36, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q. Crosstalk of autophagy and apoptosis. Involvement of the dual role of autophagy under ER stress. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232, 2977–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, G.M. Effect of sodium butyrate on autophagy and apoptosis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnol Prog 2012, 28, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. Research progress of mTOR inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem 2020, 208, 112820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heras-Sandoval, D.; Perez-Rojas, J.M.; Hernandez-Damian, J.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. The role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in the modulation of autophagy and the clearance of protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Cell Signal 2014, 26, 2694–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zeng, C.; Liu, J.; Yuan, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xie, D.; et al. Sodium butyrate induces autophagic apoptosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by inhibiting AKT/mTOR signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 514, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, H.; Fan, M.; Yu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Cai, Y.; Huang, S.; Hu, Z.; et al. Sodium butyrate inhibits migration and induces AMPK-mTOR pathway-dependent autophagy and ROS-mediated apoptosis via the miR-139-5p/Bmi-1 axis in human bladder cancer cells. FASEB J 2020, 34, 4266–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.M.; Sun, M.F.; Jia, X.B.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, B.P.; Zhou, Z.L.; Zhao, L.P.; Cui, C.; Shen, Y.Q. Sodium butyrate causes alpha-synuclein degradation by an Atg5-dependent and PI3K/Akt/mTOR-related autophagy pathway. Exp Cell Res 2020, 387, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).