Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. RNA-Sequencing

2.2.1. RNA Extraction

2.2.2. RNA Sequencing and Read Processing

2.2.3. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

2.2.4. Functional Profiling of Metabolically Stimulated Differentially Expressed Genes

2.2.5. Candidate Gene Expression

2.3. Isolation and Purification of Bat Primary Myoblasts

2.4. Cell Immortalization

2.5. Myotube Differentiation

2.6. Myoblasts Proliferation Assay

2.7. Chromosome Counting

2.8. Immunofluorescence

3. Results

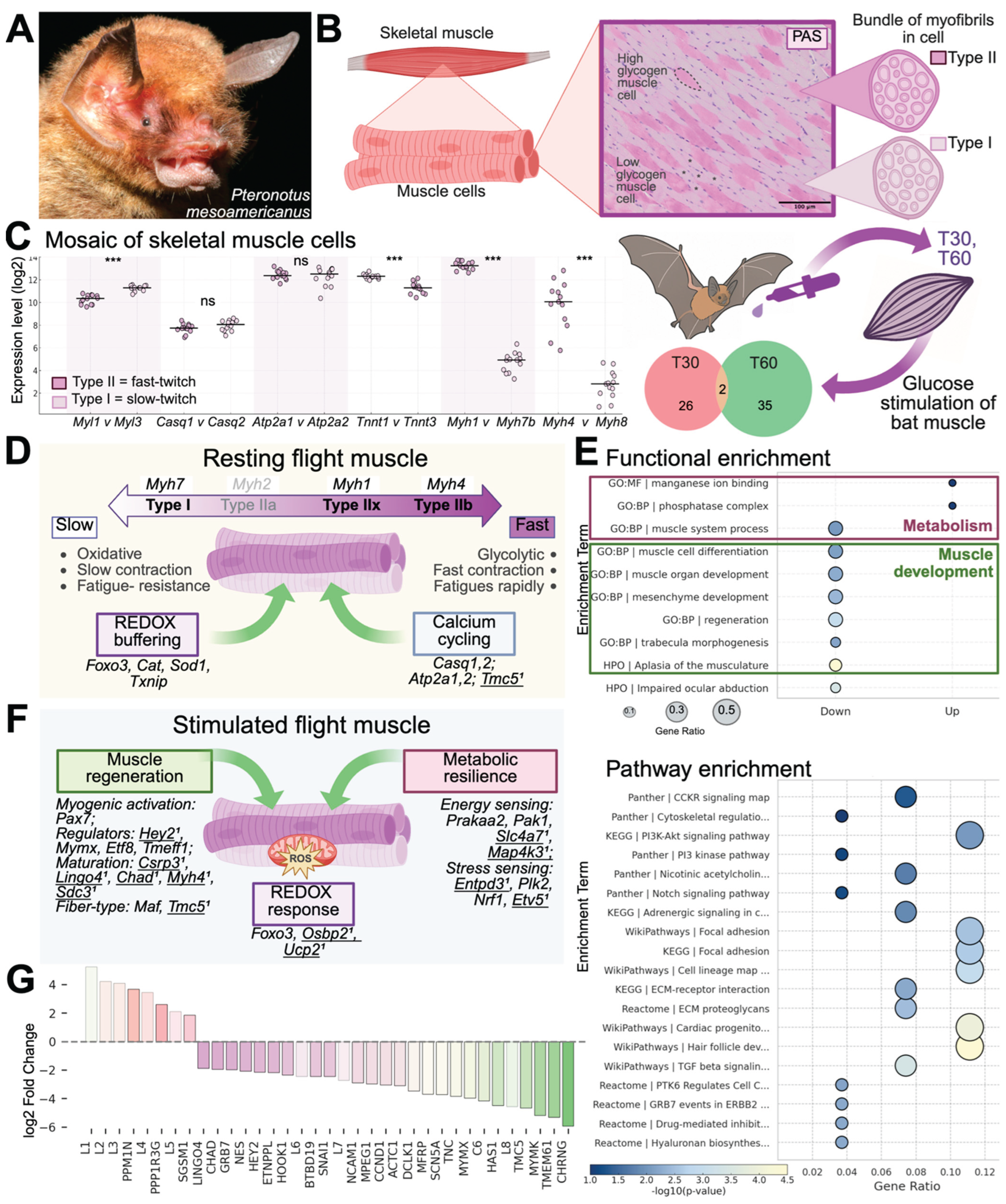

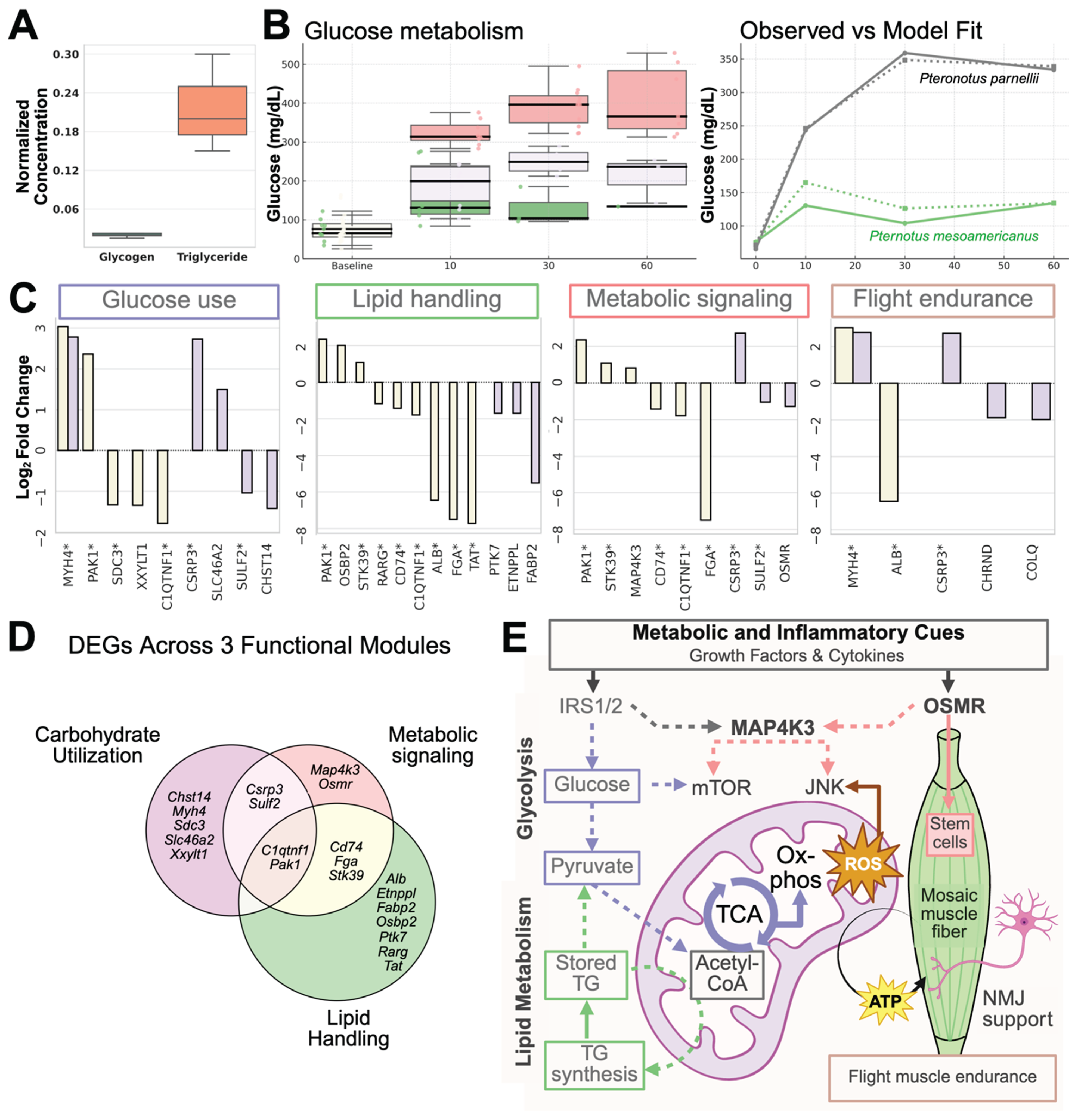

3.1. Functional and Molecular Specializations Supporting Flight in Pteronotus parnellii

3.1.1. Candidate Gene Expression Reveals Fiber-Type Heterogeneity

3.1.2. DEG Analyses Reveal Flight Muscle Activation of Regeneration and Metabolism

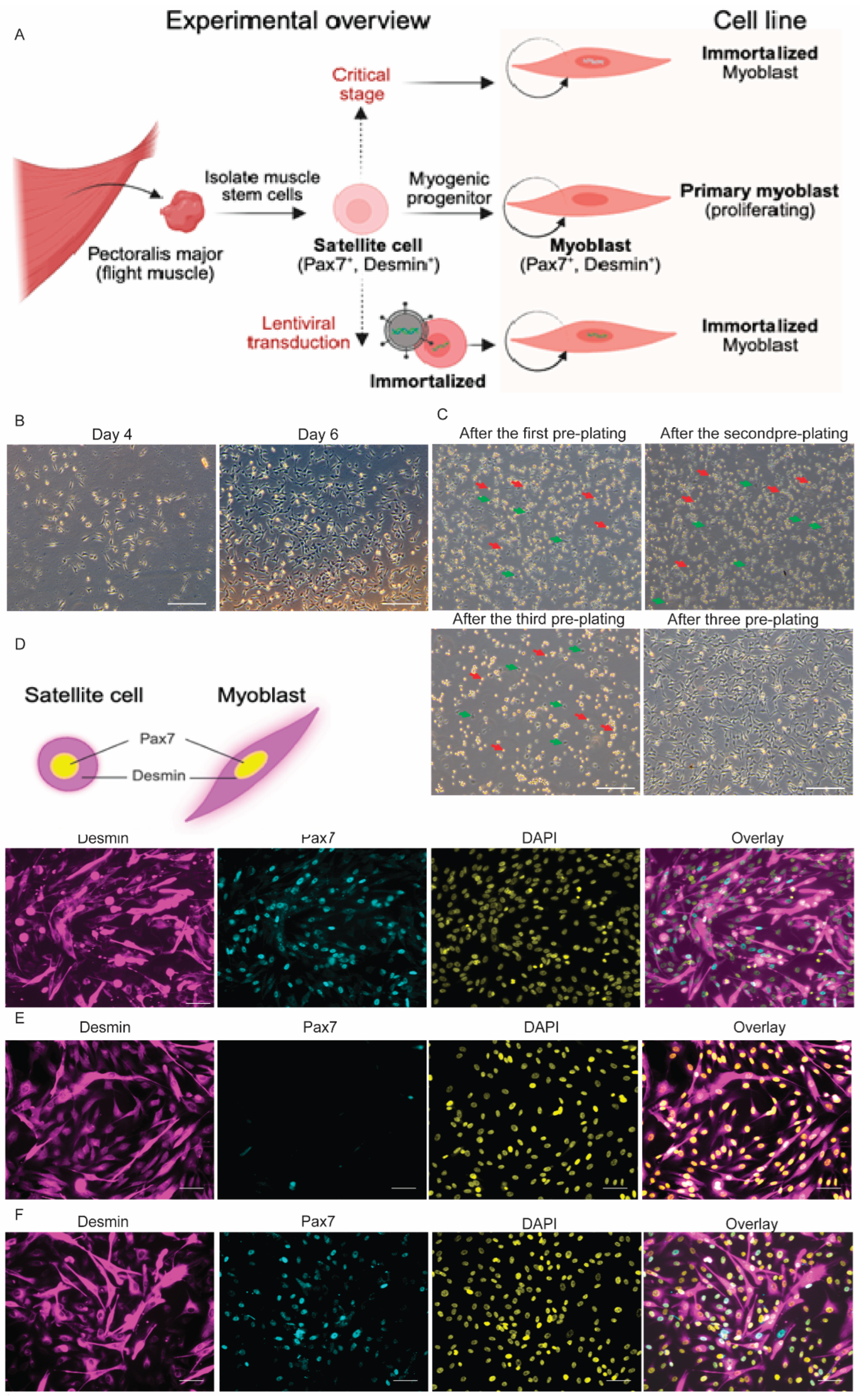

3.2. Isolation of PAX7⁺ Cells from Flight Muscle and Verification of Myogenic Cells

3.3. Establishment of Immortalized Bat Myoblast (iBatM) Cell Lines

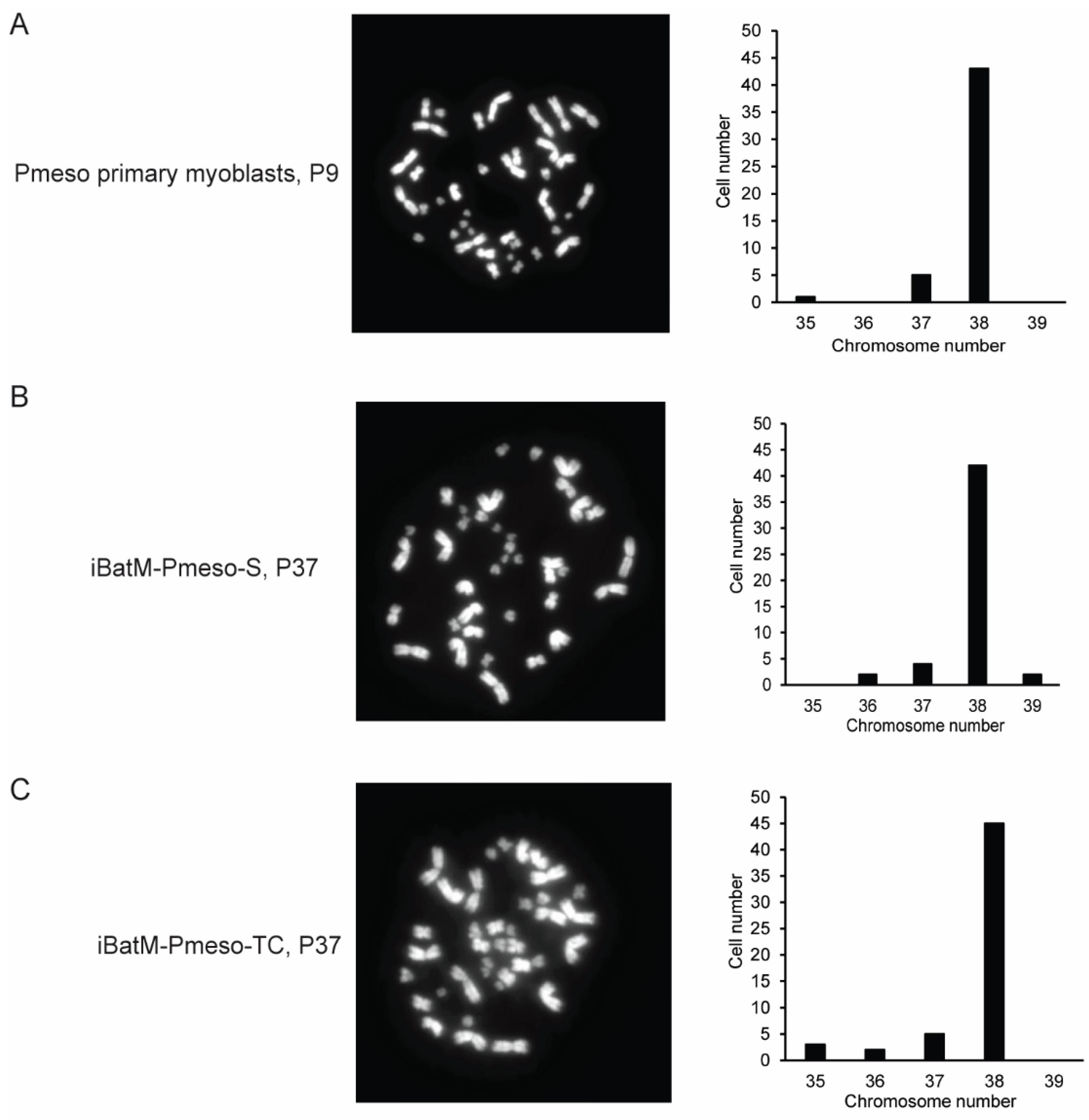

3.4. Immortalized Bat Myoblasts Are Genetically Stable

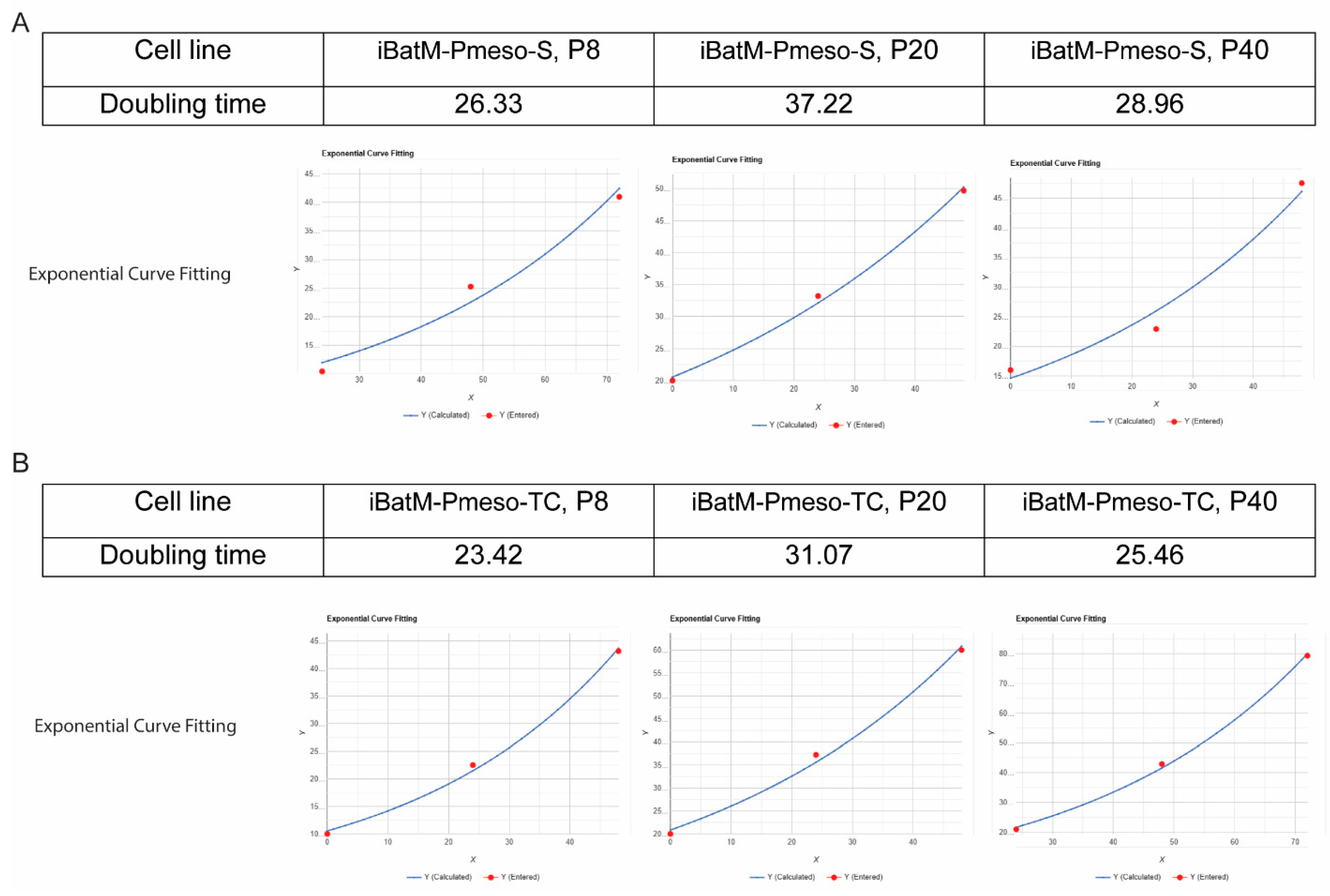

3.5. Immortalized Bat Myoblasts Retain the Proliferation Capacity of Bat Primary Myoblasts

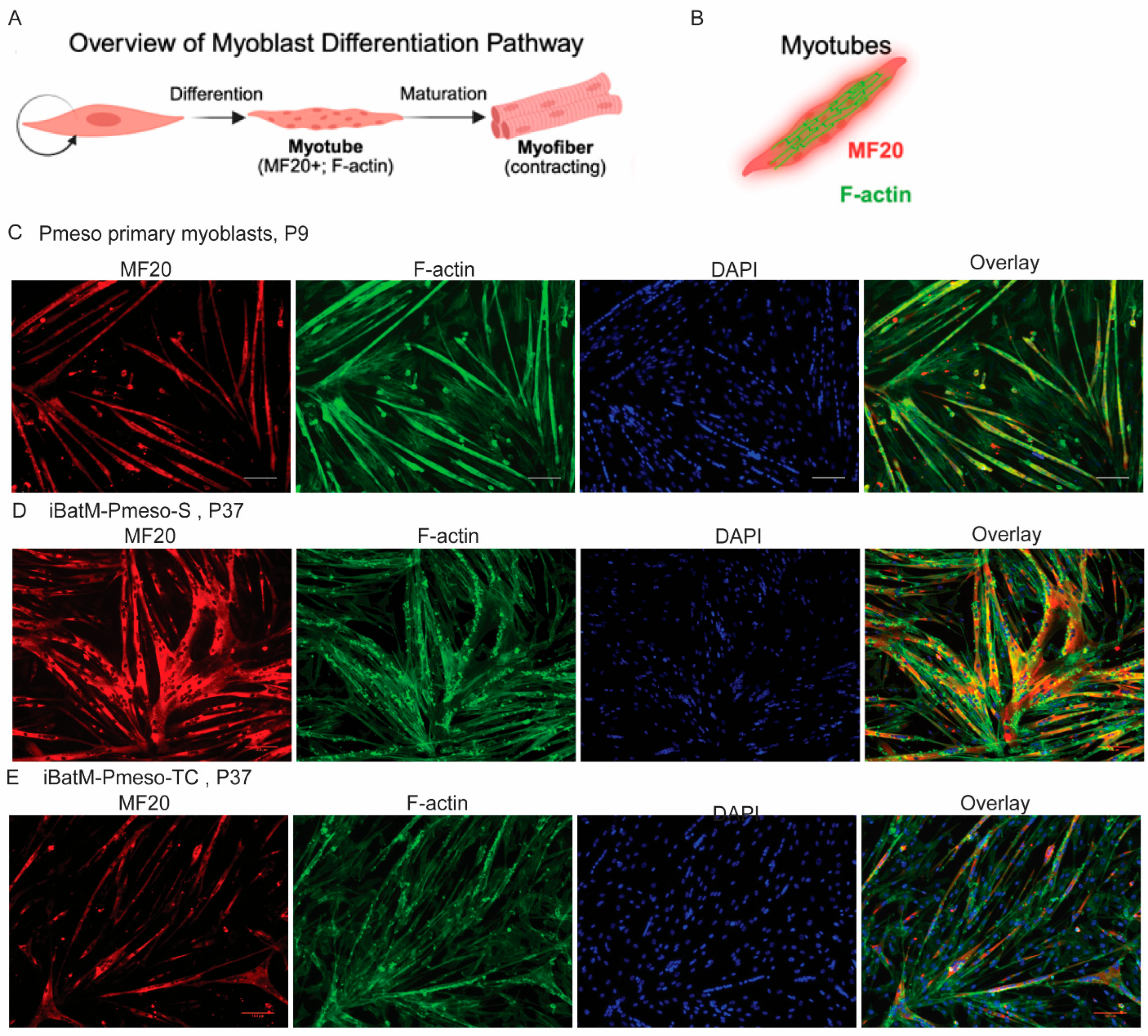

3.6. Immortalized Bat Myoblasts Retain the Differentiation Capacity of Bat Primary Myoblasts

3.7. Immortalized Bat Myoblasts Enable Functional Profiling of Flight Muscle Under Metabolic Overload

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| hTERT | human telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| CDK4 | cyclin-dependent kinase 4 |

| CDKI | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor |

| rh EGF | recombinant human epidermal growth factor |

| rh FGF-b | recombinant human fibroblast growth factor basic protein |

| P/S | Penicillin/Streptomycin |

| P. meso | Pteronotus mesoamericanus |

References

- Chal, J.; Pourquie, O. Making muscle: skeletal myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Development 2017, 144, 2104-2122. [CrossRef]

- Joe, A.W.; Yi, L.; Natarajan, A.; Le Grand, F.; So, L.; Wang, J.; Rudnicki, M.A.; Rossi, F.M. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 153-163. [CrossRef]

- Wosczyna, M.N.; Konishi, C.T.; Perez Carbajal, E.E.; Wang, T.T.; Walsh, R.A.; Gan, Q.; Wagner, M.W.; Rando, T.A. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Are Required for Regeneration and Homeostatic Maintenance of Skeletal Muscle. Cell Rep 2019, 27, 2029-2035 e2025. [CrossRef]

- Richler, C.; Yaffe, D. The in vitro cultivation and differentiation capacities of myogenic cell lines. Dev Biol 1970, 23, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, D. Retention of differentiation potentialities during prolonged cultivation of myogenic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1968, 61, 477-483. [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, D.; Saxel, O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature 1977, 270, 725-727. [CrossRef]

- Stadler, G.; Chen, J.C.; Wagner, K.; Robin, J.D.; Shay, J.W.; Emerson, C.P., Jr.; Wright, W.E. Establishment of clonal myogenic cell lines from severely affected dystrophic muscles - CDK4 maintains the myogenic population. Skelet Muscle 2011, 1, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Manchon, J.; Capo, J.; Martinez-Pineiro, A.; Juanola, E.; Pesovic, J.; Mosqueira-Martin, L.; Gonzalez-Imaz, K.; Maestre-Mora, P.; Odria, R.; Cerro-Herreros, E.; et al. Immortalized human myotonic dystrophy type 1 muscle cell lines to address patient heterogeneity. iScience 2024, 27, 109930. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.M.; Balog-Alvarez, C.; Canessa, E.H.; Hathout, Y.; Brown, K.J.; Vitha, S.; Bettis, A.K.; Boehler, J.; Kornegay, J.N.; Nghiem, P.P. Creation and characterization of an immortalized canine myoblast cell line: Myok9. Mamm Genome 2020, 31, 95-109. [CrossRef]

- Tone, Y.; Mamchaoui, K.; Tsoumpra, M.K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Terada, R.; Maruyama, R.; Gait, M.J.; Arzumanov, A.A.; McClorey, G.; Imamura, M.; et al. Immortalized Canine Dystrophic Myoblast Cell Lines for Development of Peptide-Conjugated Splice-Switching Oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Ther 2021, 31, 172-181. [CrossRef]

- Lathuiliere, A.; Vernet, R.; Charrier, E.; Urwyler, M.; Von Rohr, O.; Belkouch, M.C.; Saingier, V.; Bouvarel, T.; Guillarme, D.; Engel, A.; et al. Immortalized human myoblast cell lines for the delivery of therapeutic proteins using encapsulated cell technology. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2022, 26, 441-458. [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Chen, W.; Liu, G.; Hu, W.; Tan, Q. Establishment and characterization of a skeletal myoblast cell line of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Fish Physiol Biochem 2023, 49, 1043-1061. [CrossRef]

- Baik, J.; Ortiz-Cordero, C.; Magli, A.; Azzag, K.; Crist, S.B.; Yamashita, A.; Kiley, J.; Selvaraj, S.; Mondragon-Gonzalez, R.; Perrin, E.; et al. Establishment of Skeletal Myogenic Progenitors from Non-Human Primate Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, D.; Otsuka, Y.; Kan-No, N. Development of a novel Japanese eel myoblast cell line for application in cultured meat production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 734, 150784. [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xue, C.; et al. A spontaneously immortalized muscle stem cell line (EfMS) from brown-marbled grouper for cell-cultured fish meat production. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 1697. [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Jiao, Z.; Li, G.; An, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Establishment and Characterization of a Chicken Myoblast Cell Line. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Peruffo, A.; Bassan, I.; Gonella, A.; Maccatrozzo, L.; Otero-Sabio, C.; Iannuzzi, L.; Perucatti, A.; Pistucci, R.; Giacomello, M.; Centelleghe, C. Establishment and characterization of the Cuvier's beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris) myogenic cell line. Res Vet Sci 2025, 182, 105471. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, N.P.; Cannell, A.; Amador, L.I.; Simmons, N.B. Palaeoatmosphere facilitates a gliding transition to powered flight in the Eocene bat, Onychonycteris finneyi. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 365. [CrossRef]

- Matthew F. Jones, K.C.B.N.B.S. Phylogeny and systematics of early Paleogene bats. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 2024, 31, 18.

- Rummel, A.D.; Swartz, S.M.; Marsh, R.L. Thermal Stability of Contractile Proteins in Bat Wing Muscles Explains Differences in Temperature Dependence of Whole-Muscle Shortening Velocity. Physiol Biochem Zool 2023, 96, 100-105. [CrossRef]

- Sears, K.E.; Behringer, R.R.; Rasweiler, J.J.t.; Niswander, L.A. Development of bat flight: morphologic and molecular evolution of bat wing digits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 6581-6586. [CrossRef]

- Cretekos, C.J.; Wang, Y.; Green, E.D.; Martin, J.F.; Rasweiler, J.J.t.; Behringer, R.R. Regulatory divergence modifies limb length between mammals. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 141-151. [CrossRef]

- Tokita, M.; Abe, T.; Suzuki, K. The developmental basis of bat wing muscle. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 1302. [CrossRef]

- Eckalbar, W.L.; Schlebusch, S.A.; Mason, M.K.; Gill, Z.; Parker, A.V.; Booker, B.M.; Nishizaki, S.; Muswamba-Nday, C.; Terhune, E.; Nevonen, K.A.; et al. Transcriptomic and epigenomic characterization of the developing bat wing. Nat Genet 2016, 48, 528-536. [CrossRef]

- Feigin, C.Y.; Moreno, J.A.; Ramos, R.; Mereby, S.A.; Alivisatos, A.; Wang, W.; van Amerongen, R.; Camacho, J.; Rasweiler, J.J.t.; Behringer, R.R.; et al. Convergent deployment of ancestral functions during the evolution of mammalian flight membranes. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eade7511. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.Y.; Liang, L.; Zhu, Z.H.; Zhou, W.P.; Irwin, D.M.; Zhang, Y.P. Adaptive evolution of energy metabolism genes and the origin of flight in bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 8666-8671. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cowled, C.; Shi, Z.; Huang, Z.; Bishop-Lilly, K.A.; Fang, X.; Wynne, J.W.; Xiong, Z.; Baker, M.L.; Zhao, W.; et al. Comparative analysis of bat genomes provides insight into the evolution of flight and immunity. Science 2013, 339, 456-460. [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Jin, J.P. Evolution of Flight Muscle Contractility and Energetic Efficiency. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 1038. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.N.; Ansari, M.Y.; Capshaw, G.; Galazyuk, A.; Lauer, A.M.; Moss, C.F.; Sears, K.E.; Stewart, M.; Teeling, E.C.; Wilkinson, G.S.; et al. Bats as instructive animal models for studying longevity and aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2024, 1541, 10-23. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.A.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Shoshitaishvili, B. Revamping the evolutionary theories of aging. Ageing Res Rev 2019, 55, 100947. [CrossRef]

- Hua, R.; Ma, Y.S.; Yang, L.; Hao, J.J.; Hua, Q.Y.; Shi, L.Y.; Yao, X.Q.; Zhi, H.Y.; Liu, Z. Experimental evidence for cancer resistance in a bat species. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1401. [CrossRef]

- Athar, F.; Zheng, Z.; Riquier, S.; Zacher, M.; Lu, J.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Volobaev, V.; Alcock, D.; Galazyuk, A.; Cooper, L.N.; et al. Limited cell-autonomous anticancer mechanisms in long-lived bats. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 4125. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Cui, J.; Irving, A.T.; Wang, L.F. Unique Loss of the PYHIN Gene Family in Bats Amongst Mammals: Implications for Inflammasome Sensing. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 21722. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Chen, V.C.; Rozario, P.; Ng, W.L.; Kong, P.S.; Sia, W.R.; Kang, A.E.Z.; Su, Q.; Nguyen, L.H.; Zhu, F.; et al. Bat ASC2 suppresses inflammasomes and ameliorates inflammatory diseases. Cell 2023, 186, 2144-2159 e2122. [CrossRef]

- Moreno Santillan, D.D.; Lama, T.M.; Gutierrez Guerrero, Y.T.; Brown, A.M.; Donat, P.; Zhao, H.; Rossiter, S.J.; Yohe, L.R.; Potter, J.H.; Teeling, E.C.; et al. Large-scale genome sampling reveals unique immunity and metabolic adaptations in bats. Mol Ecol 2021, 30, 6449-6467. [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.E.; Dong, Y.; Brown, T.; Baid, K.; Kontopoulos, D.; Gonzalez, V.; Huang, Z.; Ahmed, A.W.; Bhuinya, A.; Hilgers, L.; et al. Bat genomes illuminate adaptations to viral tolerance and disease resistance. Nature 2025, 638, 449-458. [CrossRef]

- Faure, P.A.; Re, D.E.; Clare, E.L. Wound Healing in the Flight Membranes of Big Brown Bats Journal of Mammalogy 2009, 90, 1148-1156.

- Ma, S.; Upneja, A.; Galecki, A.; Tsai, Y.M.; Burant, C.F.; Raskind, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.D.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V.; et al. Cell culture-based profiling across mammals reveals DNA repair and metabolism as determinants of species longevity. Elife 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Stawski, C.; Willis, C.K.R.; F., G. The importance of temporal heterothermy in bats. Journal of Zoology 2014, 292, 86-100.

- Bernal-Rivera, A., Cuellar-Valencia, O.M., Calvache-Sánchez, C. and Murillo-García, O.E., . Morphological, anatomical, and physiological signs of senescence in the great fruit-eating bat (Artibeus lituratus). Acta Chiropterologica 2002, 24, 405-413.

- Irving, A.T.; Ng, J.H.; Boyd, V.; Dutertre, C.A.; Ginhoux, F.; Dekkers, M.H.; Meers, J.; Field, H.E.; Crameri, G.; Wang, L.F. Optimizing dissection, sample collection and cell isolation protocols for frugivorous bats. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2020, 11, 150-158.

- Carvalho, V.S.; Rissino, J.D.; Nagamachi, C.Y.; Pieczarka, J.C.; Noronha, R.C.R. Isolation and establishment of skin-derived and mesenchymal cells from south American bat Artibeus planirostris (Chiroptera - Phyllostomidae). Tissue Cell 2021, 71, 101507. [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Morales-Sosa, P.; Bernal-Rivera, A.; Wang, Y.; Tsuchiya, D.; Javier, J.E.; Rohner, N.; Zhao, C.; Camacho, J. Establishing Primary and Stable Cell Lines from Frozen Wing Biopsies for Cellular, Physiological, and Genetic Studies in Bats. Curr Protoc 2024, 4, e1123. [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, N.S.; Koh, J.Y.P.; Lee, Y.; Sobota, R.M.; Irving, A.T.; Wang, L.F.; Itahana, Y.; Itahana, K.; Tucker-Kellogg, L. Multi-omic analysis of bat versus human fibroblasts reveals altered central metabolism. Elife 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Alcock, D.; Power, S.; Hogg, B.; Sacchi, C.; Kacprzyk, J.; McLoughlin, S.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Fletcher, N.F.; O'Riain, A.; Teeling, E.C. Generating bat primary and immortalised cell-lines from wing biopsies. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 27633. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.; Word, C.; Guerra-Pilaquinga, N.; Mazinani, M.; Fawcett, S.; Portfors, C.; Falzarano, D.; Kell, A.M.; Jangra, R.K.; Banerjee, A.; et al. Expanding the bat toolbox: Carollia perspicillata bat cell lines and reagents enable the characterization of viral susceptibility and innate immune responses. PLoS Biol 2025, 23, e3003098. [CrossRef]

- Rozwadowska, N.; Sikorska, M.; Bozyk, K.; Jarosinska, K.; Cieciuch, A.; Brodowska, S.; Andrzejczak, M.; Siemionow, M. Optimization of human myoblasts culture under different media conditions for application in the in vitro studies. Am J Stem Cells 2022, 11, 1-11.

- Ding, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, G.; Hu, P. Characterization and isolation of highly purified porcine satellite cells. Cell Death Discov 2017, 3, 17003. [CrossRef]

- Shahini, A.; Vydiam, K.; Choudhury, D.; Rajabian, N.; Nguyen, T.; Lei, P.; Andreadis, S.T. Efficient and high yield isolation of myoblasts from skeletal muscle. Stem Cell Res 2018, 30, 122-129. [CrossRef]

- Mamchaoui, K.; Trollet, C.; Bigot, A.; Negroni, E.; Chaouch, S.; Wolff, A.; Kandalla, P.K.; Marie, S.; Di Santo, J.; St Guily, J.L.; et al. Immortalized pathological human myoblasts: towards a universal tool for the study of neuromuscular disorders. Skelet Muscle 2011, 1, 34. [CrossRef]

- Harley, C.B.; Futcher, A.B.; Greider, C.W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990, 345, 458-460. [CrossRef]

- Renault, V.; Thornell, L.E.; Eriksson, P.O.; Butler-Browne, G.; Mouly, V. Regenerative potential of human skeletal muscle during aging. Aging Cell 2002, 1, 132-139. [CrossRef]

- Shammas, M.A. Telomeres, lifestyle, cancer, and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2011, 14, 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.Z. Telomere length: biological marker of cellular vitality, aging, and health-disease process. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2021, 67, 173-177. [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, A.G.; Ouellette, M.; Frolkis, M.; Holt, S.E.; Chiu, C.P.; Morin, G.B.; Harley, C.B.; Shay, J.W.; Lichtsteiner, S.; Wright, W.E. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science 1998, 279, 349-352. [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, H.; Benchimol, S. Reconstitution of telomerase activity in normal human cells leads to elongation of telomeres and extended replicative life span. Curr Biol 1998, 8, 279-282. [CrossRef]

- Rayess, H.; Wang, M.B.; Srivatsan, E.S. Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int J Cancer 2012, 130, 1715-1725. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.H.; Mouly, V.; Cooper, R.N.; Mamchaoui, K.; Bigot, A.; Shay, J.W.; Di Santo, J.P.; Butler-Browne, G.S.; Wright, W.E. Cellular senescence in human myoblasts is overcome by human telomerase reverse transcriptase and cyclin-dependent kinase 4: consequences in aging muscle and therapeutic strategies for muscular dystrophies. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 515-523. [CrossRef]

- Robin, J.D.; Wright, W.E.; Zou, Y.; Cossette, S.C.; Lawlor, M.W.; Gussoni, E. Isolation and immortalization of patient-derived cell lines from muscle biopsy for disease modeling. J Vis Exp 2015, 52307. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.K.; Yuen, J.S.K., Jr.; Joyce, C.M.; Li, X.; Lim, T.; Wolfson, T.L.; Wu, J.; Laird, J.; Vissapragada, S.; Calkins, O.P.; et al. Continuous fish muscle cell line with capacity for myogenic and adipogenic-like phenotypes. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 5098. [CrossRef]

- Clare, E.L.; Adams, A.M.; Maya-Simoes, A.Z.; Eger, J.L.; Hebert, P.D.; Fenton, M.B. Diversification and reproductive isolation: cryptic species in the only New World high-duty cycle bat, Pteronotus parnellii. BMC evolutionary biology 2013, 13, 26. [CrossRef]

- Riskin, D.K.; Willis, D.J.; Iriarte-Diaz, J.; Hedrick, T.L.; Kostandov, M.; Chen, J.; Laidlaw, D.H.; Breuer, K.S.; Swartz, S.M. Quantifying the complexity of bat wing kinematics. J Theor Biol 2008, 254, 604-615. [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Garcés, S.M.; Zamora-Gutierrez, V.; Lara-Delgado, J.M.; Morelos-Martínez, M.; Ávila-Flores, R.; Kurali, A.; Ortega, J.; Selem-Salas, C.I.; MacSwiney G, M.C. The relationship between wing morphology and foraging guilds: exploring the evolution of wing ecomorphs in bats. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 2023, 142, 481-498.

- Smotherman, M.; Guillen-Servent, A. Doppler-shift compensation behavior by Wagner's mustached bat, Pteronotus personatus. J Acoust Soc Am 2008, 123, 4331-4339. [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, H.U.; Denzinger, A. Auditory fovea and Doppler shift compensation: adaptations for flutter detection in echolocating bats using CF-FM signals. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 2011, 197, 541-559. [CrossRef]

- Chionh, Y.T.; Cui, J.; Koh, J.; Mendenhall, I.H.; Ng, J.H.J.; Low, D.; Itahana, K.; Irving, A.T.; Wang, L.F. High basal heat-shock protein expression in bats confers resistance to cellular heat/oxidative stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 835-849. [CrossRef]

- Scheben, A.; Mendivil Ramos, O.; Kramer, M.; Goodwin, S.; Oppenheim, S.; Becker, D.J.; Schatz, M.C.; Simmons, N.B.; Siepel, A.; McCombie, W.R. Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Rapid Evolution of Immunity- and Cancer-Related Genes in Bats. Genome Biol Evol 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, J.; Bernal-Rivera, A.; Pena, V.; Morales-Sosa, P.; Robb, S.M.C.; Russell, J.; Yi, K.; Wang, Y.; Tsuchiya, D.; Murillo-Garcia, O.E.; et al. Sugar assimilation underlying dietary evolution of Neotropical bats. Nat Ecol Evol 2024, 8, 1735-1750. [CrossRef]

- Elizarraras, J.M.; Liao, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Pico, A.R.; Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2024: faster gene set analysis and new support for metabolomics and multi-omics. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W415-W421. [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, L.; Raudvere, U.; Kuzmin, I.; Adler, P.; Vilo, J.; Peterson, H. g:Profiler-interoperable web service for functional enrichment analysis and gene identifier mapping (2023 update). Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W207-W212. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, D.C.; Mungai, M.; Crabtree, A.; Beasley, H.K.; Garza-Lopez, E.; Vang, L.; Neikirk, K.; Vue, Z.; Vue, N.; Marshall, A.G.; et al. Protocol for isolating mice skeletal muscle myoblasts and myotubes via differential antibody validation. STAR Protoc 2023, 4, 102591. [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, K.; Otwinowska-Mindur, A.; Piorkowska, K.; Witarski, W. Influence of Media Composition on the Level of Bovine Satellite Cell Proliferation. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Neyroud, N.; Nuss, H.B.; Leppo, M.K.; Marban, E.; Donahue, J.K. Gene delivery to cardiac muscle. Methods in enzymology 2002, 346, 323-334. [CrossRef]

- Anastasov, N.; Hofig, I.; Mall, S.; Krackhardt, A.M.; Thirion, C. Optimized Lentiviral Transduction Protocols by Use of a Poloxamer Enhancer, Spinoculation, and scFv-Antibody Fusions to VSV-G. Methods in molecular biology 2016, 1448, 49-61. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, K.; Kitajima, Y.; Okazaki, N.; Chiba, K.; Yonekura, A.; Ono, Y. A Modified Pre-plating Method for High-Yield and High-Purity Muscle Stem Cell Isolation From Human/Mouse Skeletal Muscle Tissues. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 793. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, C.J.; Lee, E.Y.; Son, Y.M.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Optimal Pre-Plating Method of Chicken Satellite Cells for Cultured Meat Production. Food Sci Anim Resour 2022, 42, 942-952. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Balkir, L.; van Deutekom, J.C.; Robbins, P.D.; Pruchnic, R.; Huard, J. Development of approaches to improve cell survival in myoblast transfer therapy. J Cell Biol 1998, 142, 1257-1267. [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, B.; Lu, A.; Tebbets, J.; Zheng, B.; Feduska, J.; Crisan, M.; Peault, B.; Cummins, J.; Huard, J. Isolation of a slowly adhering cell fraction containing stem cells from murine skeletal muscle by the preplate technique. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 1501-1509. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.B.a.C., T.M. Phylogenetic Relationships Of Mormoopid Bats (Chiroptera: Mormoopidae) Based On Morphological Data. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 2001, 2001, 1-100.

- Sh., Z.; H., L.; H., L.; E., X.; D., L.; Q., C. Characterization of Proliferation Medium and Its Effect on Differentiation of Muscle Satellite Cells from Larimichthys crocea in Cultured Fish Meat Production. Fishes 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Blau, H.M.; Chiu, C.P.; Webster, C. Cytoplasmic activation of human nuclear genes in stable heterocaryons. Cell 1983, 32, 1171-1180. [CrossRef]

- Charest, A.; Wainer, B.H.; Albert, P.R. Cloning and differentiation-induced expression of a murine serotonin1A receptor in a septal cell line. J Neurosci 1993, 13, 5164-5171. [CrossRef]

- Rando, T.A.; Blau, H.M. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J Cell Biol 1994, 125, 1275-1287. [CrossRef]

- Bentzinger, C.F.; Wang, Y.X.; Dumont, N.A.; Rudnicki, M.A. Cellular dynamics in the muscle satellite cell niche. EMBO Rep 2013, 14, 1062-1072. [CrossRef]

- Maffioletti, S.M.; Gerli, M.F.; Ragazzi, M.; Dastidar, S.; Benedetti, S.; Loperfido, M.; VandenDriessche, T.; Chuah, M.K.; Tedesco, F.S. Efficient derivation and inducible differentiation of expandable skeletal myogenic cells from human ES and patient-specific iPS cells. Nat Protoc 2015, 10, 941-958. [CrossRef]

- Chal, J.; Al Tanoury, Z.; Hestin, M.; Gobert, B.; Aivio, S.; Hick, A.; Cherrier, T.; Nesmith, A.P.; Parker, K.K.; Pourquie, O. Generation of human muscle fibers and satellite-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 1833-1850. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Ulagesan, S.; Cadangin, J.; Lee, J.H.; Nam, T.J.; Choi, Y.H. Establishment and Characterization of Continuous Satellite Muscle Cells from Olive Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus): Isolation, Culture Conditions, and Myogenic Protein Expression. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Doumit, M.E.; Cook, D.R.; Merkel, R.A. Fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, insulin-like growth factors, and platelet-derived growth factor-BB stimulate proliferation of clonally derived porcine myogenic satellite cells. Journal of cellular physiology 1993, 157, 326-332. [CrossRef]

- Milasincic, D.J.; Calera, M.R.; Farmer, S.R.; Pilch, P.F. Stimulation of C2C12 myoblast growth by basic fibroblast growth factor and insulin-like growth factor 1 can occur via mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent pathways. Molecular and cellular biology 1996, 16, 5964-5973. [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, H.F.; Hughes, D.C.; Allan, R.; Deane, C.S.; Coxon, C.R.; Morton, J.P.; Stewart, C.E.; Sharples, A.P. The role of resveratrol on skeletal muscle cell differentiation and myotube hypertrophy during glucose restriction. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2018, 444, 109-123. [CrossRef]

- Fulco, M.; Cen, Y.; Zhao, P.; Hoffman, E.P.; McBurney, M.W.; Sauve, A.A.; Sartorelli, V. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Developmental cell 2008, 14, 661-673. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Li, F.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ji, Y.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y. Effect of branched-chain amino acid ratio on the proliferation, differentiation, and expression levels of key regulators involved in protein metabolism of myocytes. Nutrition 2017, 36, 8-16. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.L.; Ye, J.L.; Yang, J.; Gao, C.Q.; Yan, H.C.; Li, H.C.; Wang, X.Q. mTORC1 Mediates Lysine-Induced Satellite Cell Activation to Promote Skeletal Muscle Growth. Cells 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Elbaz-Alon, Y.; Avinoam, O. Ca(2+) as a coordinator of skeletal muscle differentiation, fusion and contraction. The FEBS journal 2022, 289, 6531-6542. [CrossRef]

- Ichio, 2nd; Kimura, I.; Ozawa, E. Promotion of Myoblast Proliferation by Hypoxanthine and RNA in Chick Embryo Extract: hypoxanthine/RNA/myoblast proliferation/embryo extract). Development, growth & differentiation 1985, 27, 101-110. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, K.; Nagata, Y.; Wada, E.; Zammit, P.S.; Shiozuka, M.; Matsuda, R. Zinc promotes proliferation and activation of myogenic cells via the PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling cascade. Experimental cell research 2015, 333, 228-237. [CrossRef]

- Duran, B.; Dal-Pai-Silva, M.; Garcia de la Serrana, D. Rainbow trout slow myoblast cell culture as a model to study slow skeletal muscle, and the characterization of mir-133 and mir-499 families as a case study. J Exp Biol 2020, 223. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.D.; Zhao, X.G.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, W.X.; Hou, Y.R.; Ren, Y.H.; Xiao, Z.D.; Zhang, Q.; Diao, L.T.; et al. Simplifying the protocol for low-pollution-risk, efficient mouse myoblast isolation and differentiation. Advanced biotechnology 2025, 3, 8. [CrossRef]

| Species/Source | Cell Line Name | Research Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | L6 | Muscle metabolism, insulin signaling, hypertrophy | [4,5] |

| Mouse | C2C12 | Myogenesis, muscle regeneration, gene expression | [6] |

| Human (Myotonic Dystrophy) | Myotonic Dystrophy Cell Lines | Myotonic dystrophy disease modeling, therapy screening | [7,8] |

| Dog (Myok9) | Myok9 | Canine muscle disease and gene therapy studies | [9] |

| Dog (Dystrophic) | Dystrophic Myoblast Cell Lines | Muscular dystrophy modeling, therapy testing | [10] |

| Human (Healthy Muscle) | Human Myoblast Cell Line | Muscle aging, physiology, regenerative medicine | [11] |

| Grass Carp | CIM | Aquatic muscle growth, stress physiology | [12] |

| Crab-eating macaque | NHP iPAX7 | Myotube differentiation and muscle regeneration | [13] |

| Japanese Eel | JEM1129 | Fish muscle development, aquaculture research | [14] |

| Brown-Marbled Grouper | EfMS | Fish muscle stem cell and regenerative studies | [15] |

| Chicken | chTERT-Myoblasts / Primary Chicken Myoblasts | Avian muscle biology, myogenesis, gene studies | [16] |

| Cuvier's beaked whale | pSV3neo myoblast cell line | Extreme hypoxia, fasting, and deep-diving | [17] |

| Bat | iBatM-Pmeso-S1 iBatM-Pmeso-TC1 |

Flight, muscle endurance, muscle stem cell and regeneration, metabolic resilience | This paper |

| Media | Base Medium | FBS | Additives | Antibiotics / Antifungals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM1 | Ham’s F-10 Nutrient Mix (Gibco, Cat# 11550043) | 20% HyClone Characterized FBS (Cytiva, Cat# SH30071.03) | 5 ng/mL recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rh EGF) (ATCC, Cat #: PCS-999-018), 10 µM dexamethasone (ATCC, Cat #: PCS-999-069), 25 µg/ml recombinant human insulin (ATCC, Cat #: PCS-999-068), 5 ng/mL recombinant human fibroblast growth factor basic protein (rh FGF-b) (ATCC, Cat #: PCS-999-020) | 2× Pen/Strep (Gibco, Cat# 15140122), 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B (R&D, Cat# B23192) |

| GM2 | 50% Ham’s F-10 Nutrient Mix +50% DMEM (ATCC, Cat# 30-2002) | 20% HyClone Characterized FBS | 5 ng/mL rh EGF, 10 µM dexamethasone, 25 µg/ml rh insulin, 5 ng/mL rh FGF-b | 2× Pen/Strep, 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B |

| GM3 | DMEM | 20% HyClone Characterized FBS | 5 ng/mL rh EGF, 10 µM dexamethasone, 25 µg/ml rh insulin, 5 ng/mL rh FGF-b | 2× Pen/Strep, 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B |

| Media | Base Medium | Horse Serum | Additives | Antibiotics / Antifungals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM1 | DMEM | 2% | — | 2× Pen/Strep, 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B |

| DM2 | Ham’s F-10 Nutrient Mix | 2% | — | 2× Pen/Strep, 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B |

| DM3 | DMEM | 2% | 5 ng/mL rh EGF, 10 µM dexamethasone, 25 µg/ml rh insulin, 5 ng/mL rh FGF-b | 2× Pen/Strep, 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B |

| DM4 | Ham’s F-10 Nutrient Mix | 2% | 5 ng/mL rh EGF, 10 µM dexamethasone, 25 µg/ml rh insulin, 5 ng/mL rh FGF-b | 22× Pen/Strep, 2 μg/mL Amphotericin B |

| Cell Line | Doubling Time | Differentiation Timeline | Advantages/Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2C12 (mouse) | ~18–24 hrs | Myotubes by day 2–3; Contraction with induction after day 5–6 |

Differentiation declines with passage; murine model; moderate NMJ relevance | [6,81] |

|

L6 (rat) |

~22–30 hrs | Myotubes by day 5–6; Contraction by day 6 with induction |

Reduced sarcomeric structure; lower nAChR expression; NMJ modeling limited | [4,5,82] |

| Primary Myoblasts | Variable (~24–36 hrs) |

Myotubes by day 8–10; Contraction after day 10 with induction |

Short culture lifespan; labor-intensive isolation; slower differentiation | [83,84] |

| iPSCs | Variable (~36–72 hrs) |

Myotubes >10 days with induction; variable contraction |

Long, heterogeneous differentiation; genomic variability | [85,86] |

| iBatM-S1 (bat) | 26.33 hrs (P8), 28.96 hrs (P40) | Myotubes by day 2; Spontaneous contraction after day 2 |

New line; long lifespan, no decline in function with passage; high NMJ relevance | This study |

| iBatM-TC (bat) | 23.42 hrs (P8), 25.46 hrs (P40) | Myotubes by day 2; Spontaneous contraction after day 2 |

As above, immortalization effects under evaluation; high NMJ relevance | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).