1. Introduction

1.1. Prospect and Limitation of Hydrogen Energy in Terms of Aging

Conventional energy sources such as fossil fuels, are extensively used to meet the global energy demand. But the combustion of such fuels is creating a greenhouse effect, global warming, acid rain, etc., type of hazardous environmental issues which ve long been a concern for environmental sustainability. Hydrogen, being the most abundant element, and a clean energy source, is a crucial energy storage vector for maximizing the benefits of sustainable energy. The most important benefit of producing energy using hydrogen; is it creates water as a byproduct instead of any other toxic substances, although NOx can still be produced during hydrogen-air combustion. As a result, different environmental issues can be minimized, and this source can be a potential replacement for current energy sources[

1]. Another advantage of hydrogen is its high specific energy density. For instance, it can provide around three times as much energy per unit of mass as conventional fuels like diesel or gasoline, i.e., approximately 120 MJ/kg[

2]. Therefore, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles can be a reliable choice instead of traditional transportation systems. Because, it can improve the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, fuel feedstock discrepancy, and onboard fuel efficiency.[

3]. A comparison of the energy content of different fuels with hydrogen is summarized in

Table 1.

On the contrary, the characteristics of hydrogen to dissolve in most metals and alloys can result in leakage and material failure, which is one of its most significant downsides. A gas cloud is created when hydrogen leaks into an area of the air, and if it comes into contact with an ignition source at this point, hydrogen cloud explosions are readily caused [

5]. Material failure by hydrogen can take place in different forms, such as hydrogen-induced cracking (HIC), hydride embrittlement (HE), hydrogen-induced blistering, and other detrimental effects that commonly lead to catastrophic fractures[

6]. A long-time exposure to the hydrogen environment increases the degradation and damage rate of the materials which is generally known as the aging of materials. In normal conditions, the degradation and damage rate of the materials is far different from the long-term exposure to the hydrogen environment. Thus, this is a great challenge for the hydrogen industry to understand the aging processes as well as try to find remedies. The service life and safety performance of the hydrogen industry are mostly dependent on taking the aging process into consideration while designing and selecting the materials.

1.2. Historical Scenario of Hydrogen-Induced Aging

Almost half of the pipeline infrastructure in the United States is 40 years or older but still in service and getting aged. "Aging" refers to the continual time-dependent deterioration of materials under normal operations and intermittent conditions. [

7]. Numerous factors, including temperature, creep, fatigue, and brittleness in a hydrogen environment, lead to the aging phenomenon. According to a structured database of Dutch investigated big accidents, 25% of accidents are related to aging through material deterioration[

8]The aging phenomenon can be categorized into material deterioration, obsolescence, and organizational aging. The discussion of the current article is limited to the material deterioration section. [

9] Here, some of the historical incidents that took place due to aging are discussed in

Table 2.

1.3. Impact of Operating Conditions on Hydrogen-Assisted Aging

Operating conditions have a significant effect on hydrogen-induced aging. This effect is visualized when different metallic items are investigated, which have been used for several years in a hydrogen-containing environment. The result shows that the hydrogen expedited the deterioration process. Slobodyan et al. [

16] took into consideration, for instance, the top and bottom parts of the pipe that were used in an oil pipeline for 30 years. Residual water that was left over after the transported hydrocarbons, acted as an aggressive species, accumulated at the pipe's bottom, and created an environment that was conducive to corrosion and subsequent hydrogenation of the bottom section of the pipe. Thus, the lower half of the pipe had significantly more defective steel characteristics than the top. Continuous exposure of pipeline systems to challenging operating circumstances might hasten the aging process and result in unheard-of breakdowns from hydrogen-induced damage. When certain materials are exposed to hydrogen and stress at the same time, it can cause a serious problem called hydrogen embrittlement. This means that the material becomes brittle and can easily break or crack under pressure. Atomic hydrogen may be produced through the adsorption and dissociation of hydrogen gas on steel pipeline surfaces [

17]. A material failure mode is introduced, and several damage processes are linked to the entry of atomic hydrogen into interstitial spaces. According to ASME B31.12, pipes must adhere to specified requirements to be used in service lines for gaseous and liquid hydrogen[

18].

1.4. Potential Reasons of Hydrogen Assisted Aging

The tiny hydrogen molecules are impressive flee artists, which is the main distinction between hydrogen-driven aging and other liquids in the same specimen. In general, exceedingly low boiling point (- 253ᴼ C), significantly lower density in the gaseous stage (0.09 kg/NA m3), and extremely high density in the liquid phase (70.9 kg/NA m3) of hydrogen present challenges for conventional storage facilities. [

19]. Not only hydrogen can diffuse straight through solid steel, but it can also travel through the slightest of seal flaws. Elastomeric materials are typically utilized extensively in sealing components as well as other applications, such as control valves, liners, connectors, and flexible hoses, which are also constantly subjected to high-pressure hydrogen under operating conditions. [

3]. Rubbery O-rings are a sealing-type material that can face blister fracture, a type of internal fracture where fracture takes place due to the rapid decompression of highly pressurized hydrogen gas [

20]. The entry of atomic hydrogen into interstitial gaps frequently results in leakage. Thus, the minimal size and the density difference in different physical states make it a very challenging material for storage. Also, its high diffusivity through metallic and polymeric materials makes it a challenging material for sealing. It has a high tendency to leak as well.

1.5. Potential Mechanism of Hydrogen-Induced Aging on Storage and Sealing Materials

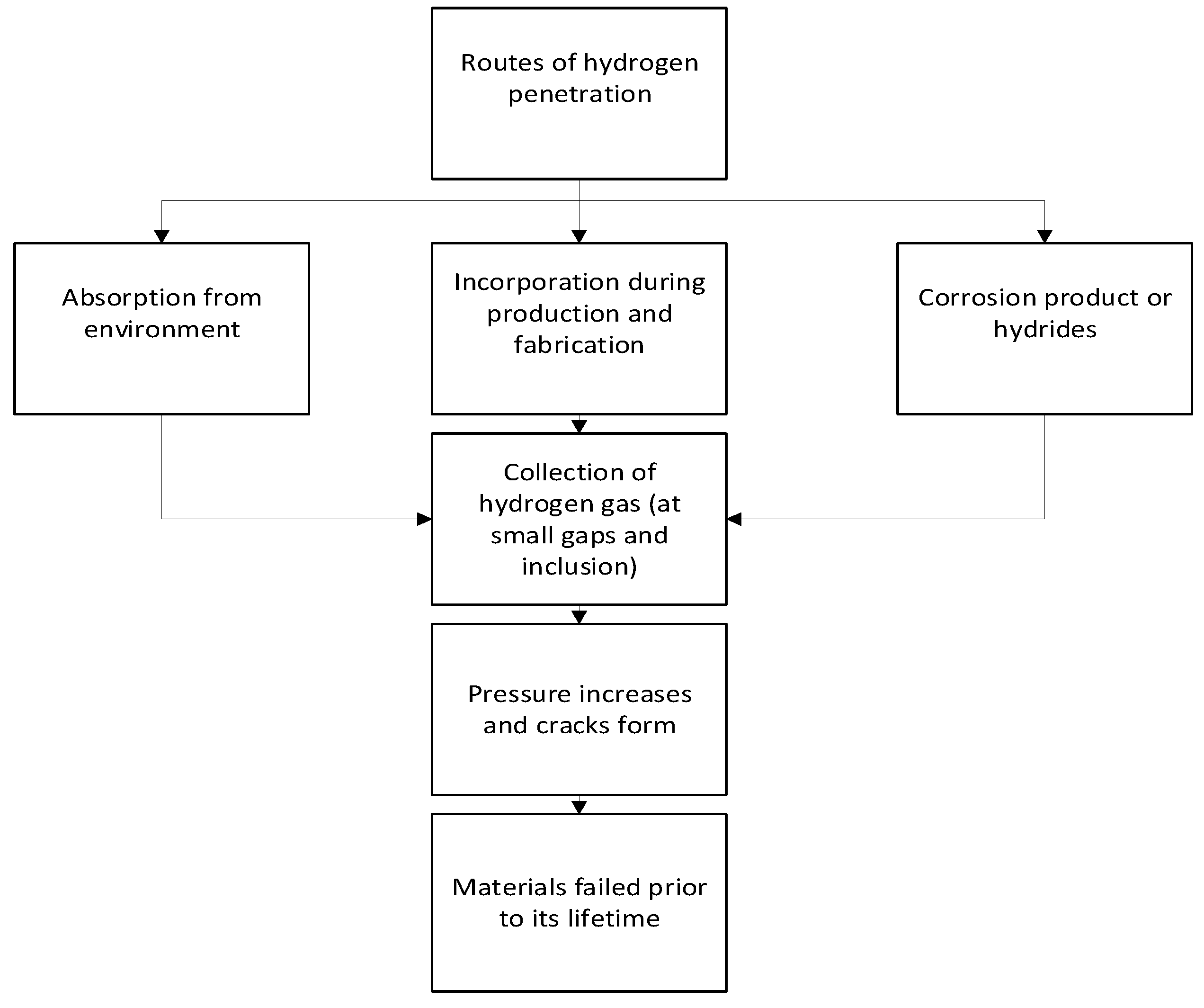

Hydrogen-induced aging on storage and sealing materials can occur through several mechanisms. One potential mechanism is hydrogen diffusion into the material, where the hydrogen atoms can react with and weaken the chemical bonds within the material. This can cause a loss of elasticity and increased stiffness, leading to cracks and failures over time. A simple flowchart of the hydrogen-induced aging mechanism is shown in

Figure 1.

The associated reactions are below [

14,

17]:

The cumulative experience of process operations demonstrates that residual deformation can frequently occur without observable structural component damage. Laboratory-scale research is needed to obtain a detailed analysis of likely event data and evaluate whether hydrogen-induced aging is a substantial concern for a particular application, in addition to identifying the key elements or problems that are causing it. In this review article, the aging phenomenon of hydrogen storage and sealing materials will be discussed, along with the various types of aging and their mechanisms in a hydrogen environment. Alongside this, a comparison of the various laboratory tests that have been carried out to comprehend the aging process and predict the service life of the materials will be discussed as well. Additionally, it has been approached to identify the research shortcomings to be further investigated for the establishment of the standard protocol for aging.

2. Methods of Aging in a Hydrogen Environment

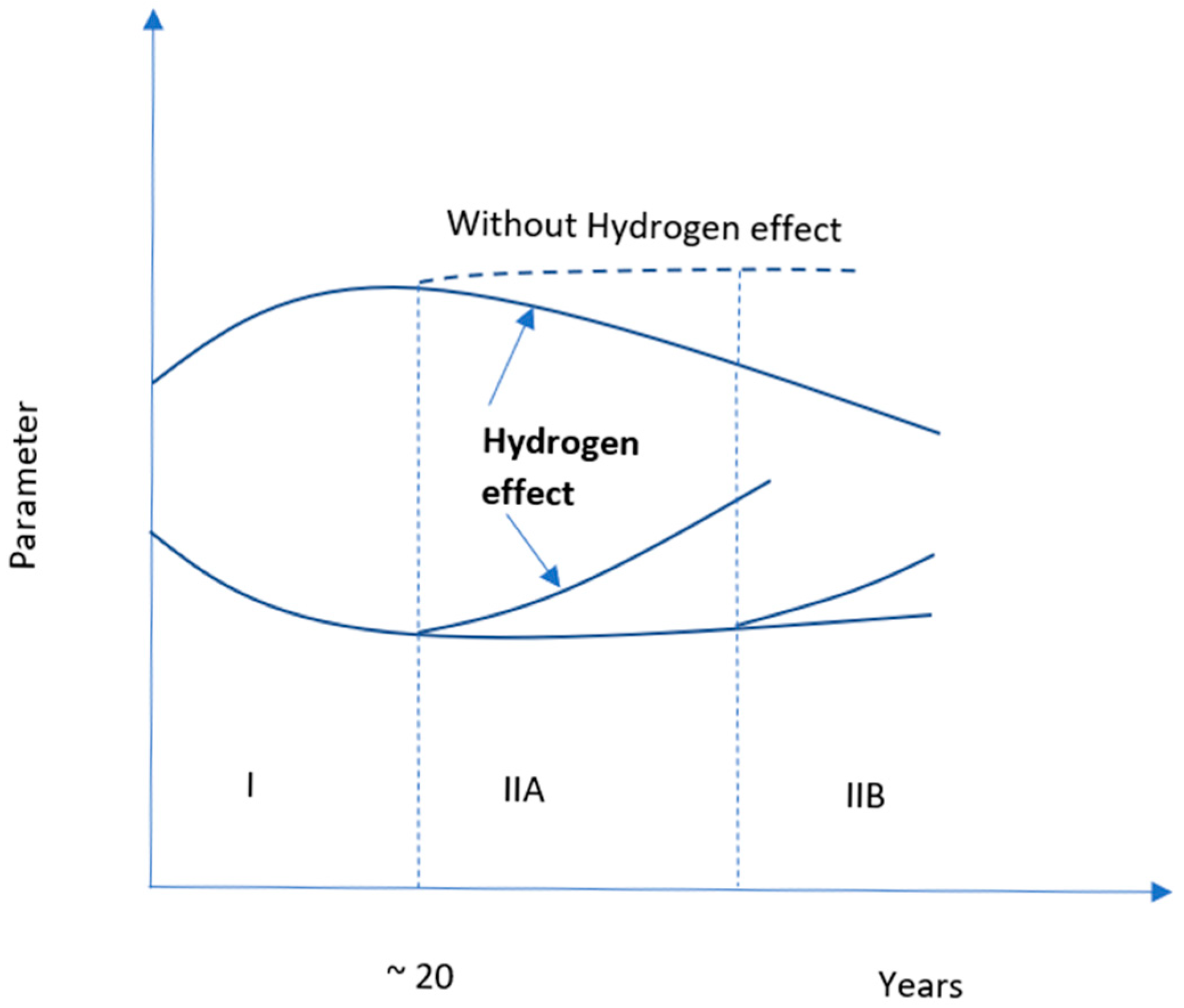

As the materials age more quickly in the hydrogen environment, storage and sealing materials for hydrogen must overcome significant obstacles. The general patterns of operating deterioration of the properties of infrastructure materials, as depicted in

Figure 2, were summarized by Nykyforchyn et al. [

22].

Figure 2 indicates the degradation of materials over time under a hydrogen environment. Hydrogen aging can be visualized from this figure. Here, Stage I in the figure represents aging by deformation, and Stage II contains two stages, IIA and IIB, which represent dispersed damage, and the buildup of damage in the rolling direction, correspondingly. In stage II, due to the accumulation of hydrogen, micro damages are evolved, which erode the natural integrity of the material. In stage II the dotted line shows the behavior of the materials in the absence of hydrogen. Thus, it indicates that hydrogen can accelerate the degradation process of the materials.[

22,

23]. Hydrogen embrittlement of metallic materials can be a guideline example here. The incorporation of hydrogen in metals makes a secondary hydride phase which is brittle. As a result of brittleness, the structural integrity of the metals become weak, which degrade the metal more rapidly than in normal condition. Therefore, the theme supports the aging process demonstrated in the figure. However, there is still significant disagreement over the main mechanism by which this deterioration process occurred. Adsorption-induced dislocation emission (AIDE), hydrogen-enhanced localized plasticity (HELP), and hydrogen-enhanced de-cohesion mechanism (HEDE) are the fundamental mechanisms that have been heavily responsible for hydrogen-induced embrittlement [

24]. The future of this sector will be more challenging if the storage and sealing materials do not become resilient in a hydrogen atmosphere. Because productivity drastically declines if produced hydrogen cannot be stored appropriately. Materials can be aged in a hydrogen environment through various processes, including thermal aging, chemical aging, mechanical aging, mechanical-chemical aging, thermo-mechanical aging, etc.

2.1. Thermal Aging

Thermal aging of materials means the permanent structural, compositional, and morphological changes of materials over a period exposed to temperatures that materials face during service. Materials can structurally degrade because of thermal cycling, which can take place to accelerate the diffusion processes of hydrogen. The solubility of hydrogen in metals is proportional to temperature. With decreasing temperature, diffusion mobility decreases.[

25]. Therefore, thermal aging increases with increasing temperature.

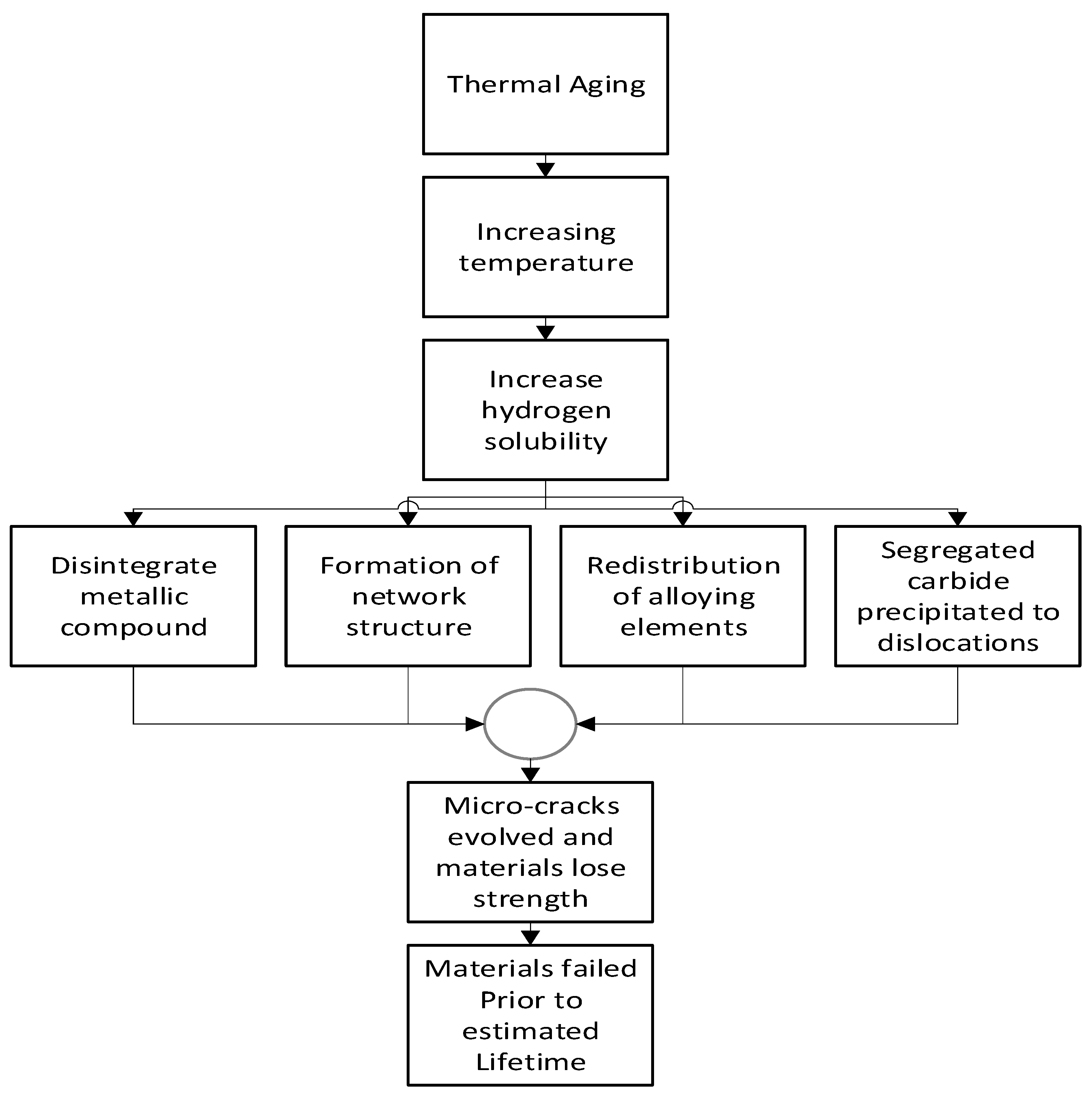

2.1.1. Mechanism of Thermal Aging

Thermal aging is directly related to the diffusion of hydrogen at different temperatures. Sharp temperature drops can decrease the equilibrium hydrogen solubility in the metals[

26]. At 570°C and 100°C, Kolachev [

23] found that the coefficient of hydrogen diffusion was 2×10

-4 cm

2/sec and 4.4×10

-5 cm

2/sec, respectively, which indicates the coefficient of hydrogen diffusion varied with temperature. The flowchart in

Figure 3 indicates the mechanism of thermal aging.

2.1.2. Laboratory Test for Thermal Aging

For thermal aging of structural steel under a hydrogen environment, Student O.Z. [

21] conducted a laboratory test where a hydrogen-filled sealed chamber was used for placing the sample under the pressure of 0.3 MPa and electrically heated at service temperature ranging from 550° to 570°C at the rate of 100°C/min for one hour. After cooling at 100°C at a rate of 50°C/min, the 12Kh1MF steel specimen was kept in a vacuum at the thermal cycle for two hours. It has been observed that due to the temperature variation, the equilibrium solubility of hydrogen changes, which led to the disintegration of cementite and the network formation of alloyed carbides. Because of the thermal cycling, thermal stresses evolved and created microcracks which caused the thermal aging of structural steel[

29]. Hirakami et al. [

30] conducted a laboratory test with two samples of drawn pearlitic steel that were aged at 100°C and 300°C for 10 minutes and tested under a slow strain rate testing method for measuring the hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility. The result shows that the hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of the steels at 300°C is reduced because the carbons are segregated to the dislocations and carbides are precipitated to the dislocations. Age-hardened beryllium-copper alloy, a suitable replacement for austenitic stainless steel used to store hydrogen at refueling stations, was tested in a laboratory by Ogawa et al. [

31]. They observed that the hydrogen solubility capacity of the beryllium-copper alloy was two to three times lower than that of austenitic steel. However, after exposing the specimen to 100 MPa hydrogen for 500 hours at high temperatures of 270°C, hydrogen diffusion may be enhanced. As a consequence, the specimen's mechanical qualities declined; for instance, only the tensile strength fell by around 5%. [

31,

32]

Thermal aging of sealing materials is not extensively studied yet. Yamabe et al. [

32], Fujiwara et al. [

34] and Simmons et al. [

35] tested elastomeric sealing material NBR at room temperature, 30°C, and 110°C respectively, and found that there is no hydrogenation or structural activity till 30°C but at 110°C compression set is increased by 40% which indicates that with increasing temperature the elastomeric sealing materials show a thermal aging tendency. Menon et al. [

36], Castagnet et al. [

37] and Klopffer et al. [

38] tested different types of thermoplastic polymeric sealing materials under room temperature and 20-80°C respectively and observed some random behavior. The degree of crystallinity can be increased with increasing temperature, but mechanical properties cannot change. This is because, with increasing temperature, the plasticization of the polymer can also increase. This phenomenon indicates that these thermoplastics have the ability to resist aging to some extent.

2.2. Chemical Aging

Chemical aging is a type of aging where materials are aged because of the long-term interaction with the chemical environment, and due to this interaction material’s structure, composition, and morphology change permanently. In this method, materials remain in contact with different chemicals, mostly immersed in the solution and charged with hydrogen.[

33,

34,

35]. This type of aging is frequently seen in both storage and sealing materials due to their continuous interaction with chemicals.

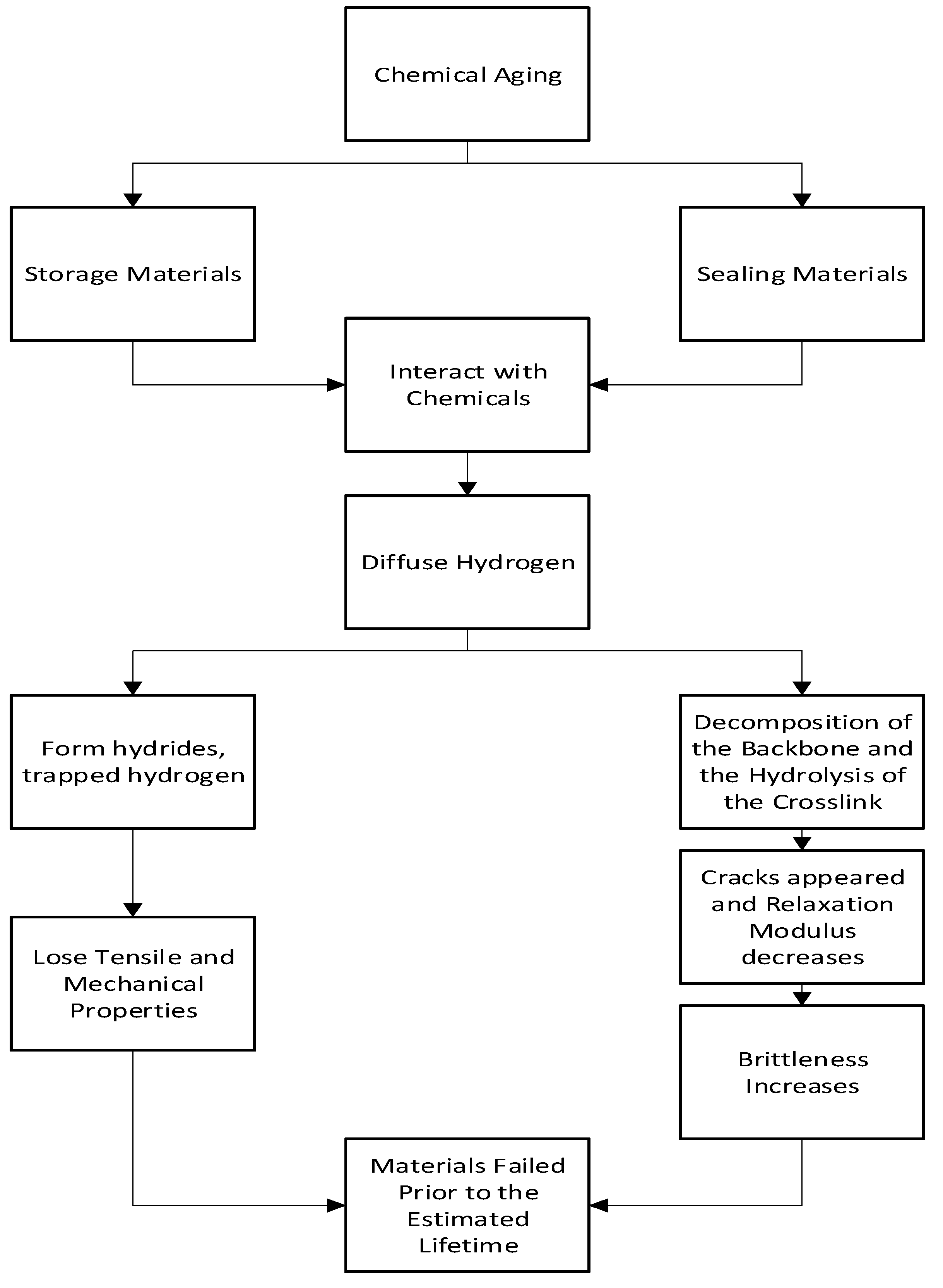

2.2.1. Mechanism of Chemical Aging

Chemical aging is one of the most common forms of aging found in hydrogen storage and sealing materials. In hydrogen-storing metallic materials, the hydrogen's distribution and state influence the hydrogen embrittlement and the tensile properties of the metal and lead to complete aging[

36]. In hydrogen-sealing materials, cracks are formed by the decomposition of the backbone and the hydrolysis of crosslinks which leads to aging[

34]. This phenomenon can be observed in

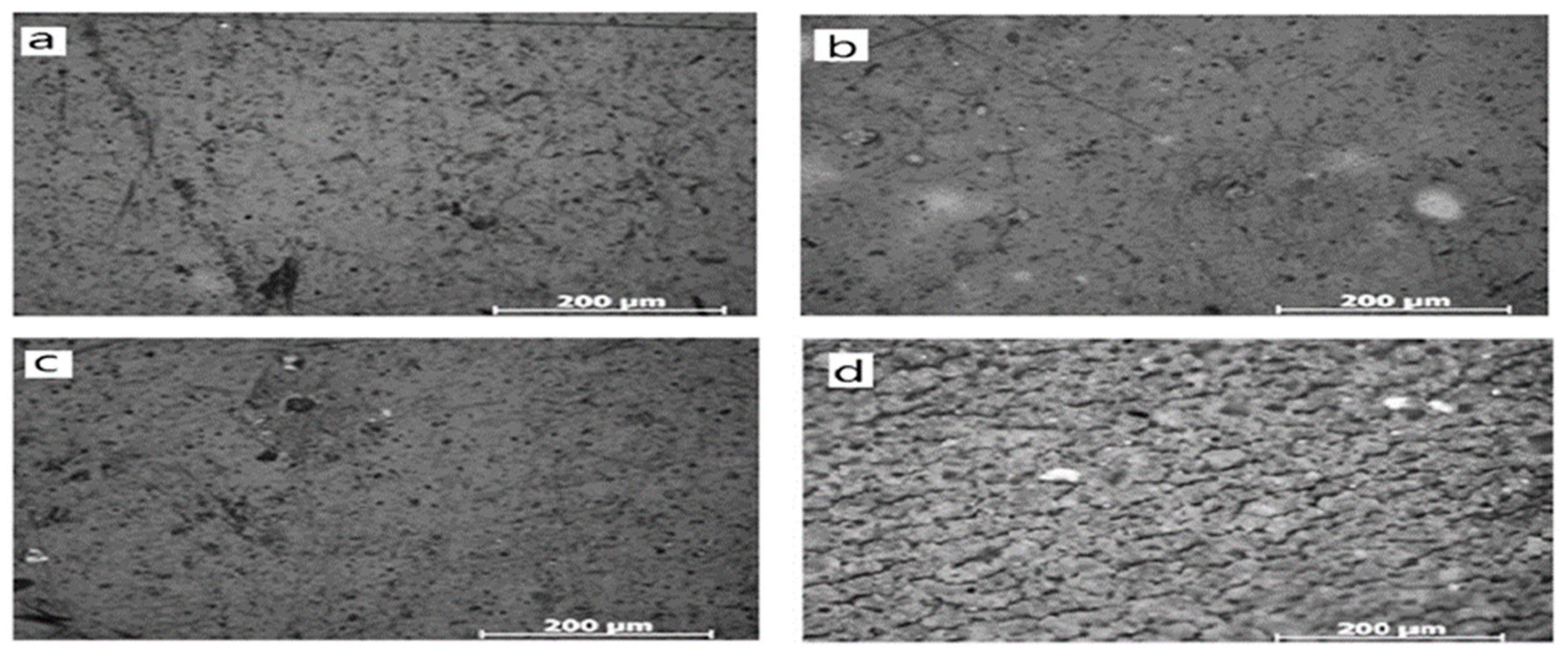

Figure 4.

The micromorphological analysis conducted by Li et al. [

34] mimics the surface of the sealing material. It shows that with increasing the hydrogen content, the condition becomes harsher, and cracks appear. Figures 4 (a) and 4 (c) are unexposed samples, (b) and (d) are exposed to mild and harsh conditions, respectively. From this figure, it is clear that with increasing the harshness of the condition, surface roughness is increasing. Surface roughness indicates the formation of cracks here. Thus, surface roughness indicates the aging of polymeric sealing materials.

Figure 5 flowchart indicates the chemical aging mechanism for hydrogen storage and sealing materials.

2.2.2. Laboratory Test for Chemical Aging

Ogawa et al. [

36] used martensitic Ni-Ti alloy specimens and acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF) solution for the aging test. Cathodic electrolysis was used for charging the samples with hydrogen, where charged specimens were aged for 16h in the air at room temperature. The results show that the reduction in the tensile strength increase the brittleness and led the sample toward aging. Ogawa et al. [

36] further conducted a different type of post-aging test on non-immersed and immersed specimens to determine the post-aging behavior of the material, where the tensile test was performed within a few minutes after the removal of the specimen from the solution at room temperature. The results show that the tensile strength of the sample can be decreased. A Vickers micro-hardness test was done to determine the hardness of the specimen. Results show that the hardness can be increased, which increases the brittleness. TDA and XRD analysis was done to check the corrosion product and hydrides on the surface and for the quantitative analysis of trapping hydrogen, respectively. Each test has confirmed the pick for hydrogen absorption and hydride formation, indicating the aging was being processed after charging.

Tal-Gutelmacher et al. [

37] conducted laboratory tests on three Titanium-based alloys: Ti-6Al-4V, Beta-21S, and Ti-20wt.%Nb. Ti-6Al-4V alloy was thermo-mechanically treated and exposed to a hydrogen environment. The alloy formed brittle titanium hydride phases which is a key factor for chemical aging. Beta-21S was exposed to hydrogen electrochemically at room temperature, which show good resistance to hydrogen.

Ti-20wt.%Nb was exposed to hydrogen in two ways, electrochemically and in a gaseous environment. Electrochemical exposure formed (Ti, Nb)Hx hydride, and gaseous exposure created titanium hydride only. In both cases, Ti-20wt.%Nb had to face chemical aging. Nykyforchyn et al. [

41] tested ferrite-perlite X52 steel pipe after long-term service at the gas trunkline and found that all the mechanical properties of the material deteriorated due to the increment of hydrogen trapping. The bottom side of the pipe severely deteriorated, indicating that during the flowing of aggressive substances through the pipe maximum portion of hydrogen penetrated the pipe and was trapped there. OMURA et al. [

38] conducted a laboratory test on some stainless steel and Ni-based alloys and found that high nitrogen stainless steel and alloy 286 had the maximum hydrogen concentration (Hc) at which fracture elongation was hard to be degraded. High nitrogen stainless steel had higher Hc than the concentration of hydrogen-absorbing from service environment HE, lowering the chance of hydrogen embrittlement in-service condition. For internally reversible hydrogen embrittlement, Alloy 286 and 718 show severe results compared to the cathodic charge.

Li et al. [

40] conducted a laboratory test using elastomeric gaskets made of silicone rubbers as a specimen. Different concentrations of acid were used for the test. Depending on the concertation, one solution was called a regular solution which has an environment like a regular working environment, and another one was highly concentrated and used for an accelerated durability test (ADT). The concentration for the regular solution was 12.5 ppm sulfuric acid and 1.8 ppm hydrofluoric acid and the concentration for ADT was 1 mil.L

-1 sulfuric acid and 30 ppm hydrofluoric acid. During the experiment, the decomposition of the backbone and the hydrolysis of the crosslink of the polymeric gasket material take place, leading to a reduction in the elasticity and sealing force. As a result, the material aged under a hydrogen environment. KLOPFFER et al. [

39] tested polyethylene and polyamide membranes and tubes under a hydrogen environment with controlled pressure and temperature. After long-term exposure to hydrogen, the measured permeability capacity of polyamide became lower than polyethylene. But the mechanical properties of both materials remain almost unchanged.

2.3. Mechanical Aging

The mechanical aging of the materials is a slow, progressive, and irreversible process of losing the capability to perform the assigned work under a high mechanical loading condition. Mechanical aging is often observed in fuel cell conditions where high-pressure hydrogen molecules create a high loading condition on the sealing material and in the hydrogen storage system.

2.3.1. Mechanism of Mechanical Aging

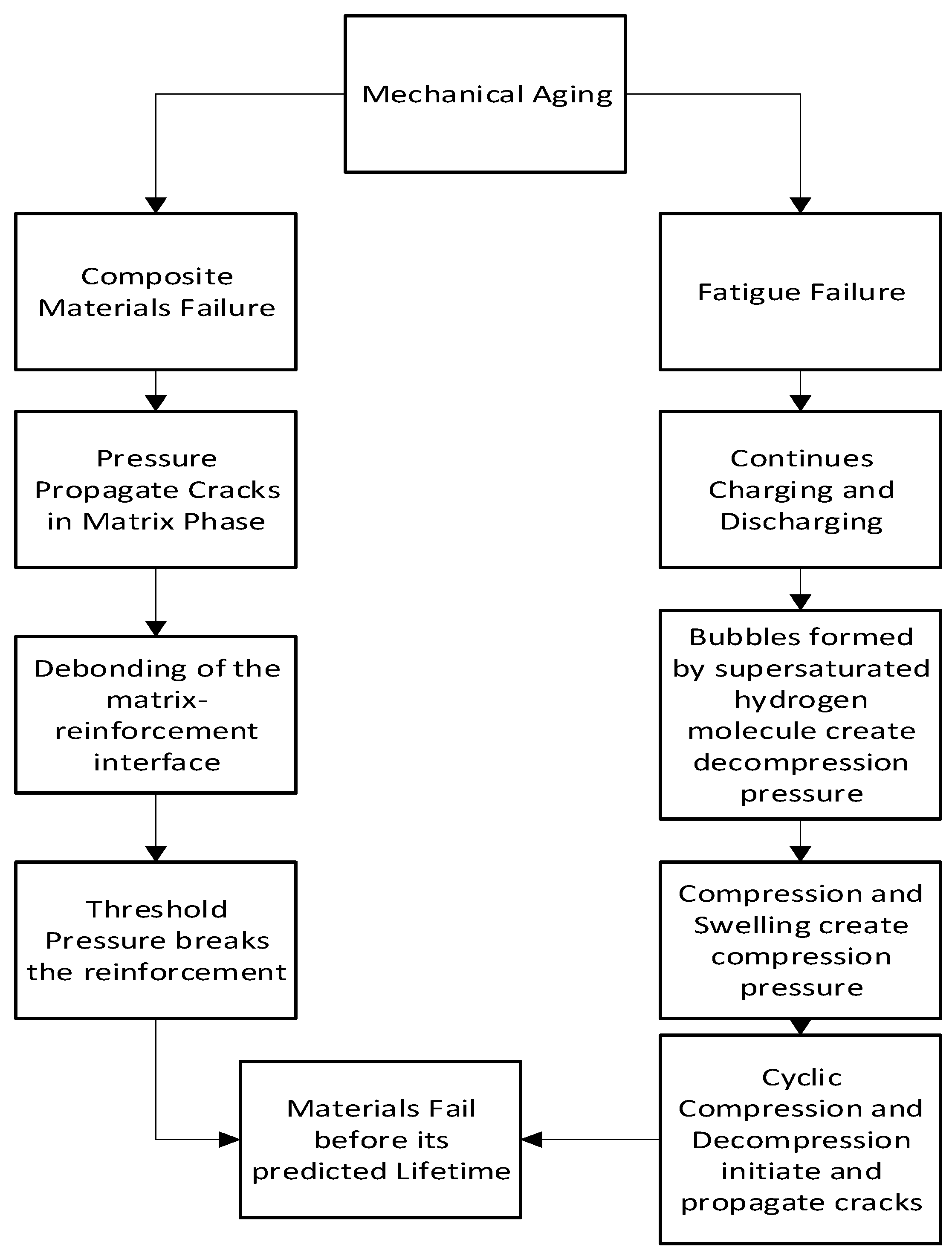

Mechanical aging is found in hydrogen storage tanks made of composite materials. Burst pressure, fiber damage, fatigue, collapse, and blistering of liners are some failure modes in this type of aging.

Figure 6 flowchart indicates the mechanism of mechanical aging.

When pressure is applied to a composite material, cracks can develop and extend profoundly to the matrix phase, which facilitates interface debonding. When the pressure reaches its threshold, a substantial quantity of reinforcement fails and causes the material to implode. On the other hand, continuous charge and discharging causes material fatigue which impacts mechanical aging. The mechanism for the formation of these types of cracks involves the initiation and growth of cracks as a result of strain concentration. The strain concentration can be caused by supersaturated hydrogen molecules creating bubbles after decompression and strain as a result of compression and swelling. Shear stress, induced by the concentration gradient of solute gas molecules, initiates randomly organized circumferential cracks. As compressive tension increases, so does volume expansion or swelling. As a result, tensile stress increases and fracture propagation accelerates. When the decompression rate is accelerated, cracks in the surface appear visibly. [

40,

41].

2.3.2. Laboratory Test for Mechanical Aging

Wang et al. [

42] analyzed the carbon fiber/epoxy composite used in hydrogen storage pressure vessels. They continuously increased the pressure of the vessel, and after 324 MPa suddenly the pressure fell to zero, indicating bursting. Zheng et al. [

42] conducted a fatigue test to analyze the behavior and fatigue life of the carbon fiber/epoxy composite. They found after 500 cycles the composite faced fatigue bursting; at that moment, pressure significantly can be decreased by about 15%. Feng et al. [

43] analyzed the welded joints of TC4 titanium alloys for storage tanks considering 10,000, 20,000, and 30,000 pre-cycles. After 24 hours of electrochemical hydrogen charge on the specimen, the failure process was studied using SEM and TEM. The results show that the initial dislocation density of the specimens rises with the number of pre-cycles, making the hydrogen embrittlement through aging more severe. Following 10,000 and 20,000 pre-cycles, the specimens exhibited fewer dislocations and hydrogen capture at specific sites. In contrast, after 30,000 pre-cycles, dislocation accumulation and entanglement appeared both along the phase boundary and within the phase, resulting in a greater number of hydrogen capture sites. At lower cycles, the HELP mechanism dominates the tensile process, whereas the HEDE mechanism dominates the process at higher cycles.

YAMABE et al. [

41] conducted a laboratory test where a high-pressure O-ring seal was used as a specimen. The O-ring was made of low-nitrile NBR (acrylonitrile content: 18%), which was vulcanized by sulfur and filled with carbon black. With a 30% compression ratio, the specimen was compressed in a radical direction. Then it was inserted in a vessel that was pressurized by hydrogen from the bottom. They conducted Optical and scanning electron microscopy in post-aging situations to observe the cracks. Also, they conducted gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy to measure the hydrogen gas content and a densimeter to measure the volume increase. They found two types of cracking for failure; one started from the center of the O-ring and another from near the surface. Brownell et al. [

44] conducted a simulation on ethylene-propylene-diene-based elastomeric rubber, they used O-rings and hose liners as specimens and exposed the sample to a pressurized hydrogen environment. Due to high pressure and rapid decompression, the specimen failed as a result of cavitation and stress-induced localization of hydrogen gas. This result supports the experimental result NBR O-ring.

Wilson et al. [

45] conducted the same simulation as Brownell et al. [

44]. They just increased the crosslinking of the polymer using Sulphur and found crosslinks create extra free volume at a pressure that facilitated the localization tendency of the hydrogen gas. Zhou et al. [

46] modified the rubber seal materials including O-ring to D-ring and conducted a simulation using finite element analysis. Their results show that the O-rings have more tendency to fail under stress concentration compared to D-rings under hydrogen pressure range 0–100 MPa. At high hydrogen pressure and contact stress, the D-ring outperformed the O-ring in terms of sealing ability, but the inverse was true under low pressure. They also analyzed the friction effect on the failure and found D-ring had better performance against friction compared to the O-ring at high pressure.

2.4. Mechanical-Chemical Aging

The mechanical aging of materials is a slow, progressive, and irreversible process of losing the capability to perform the assigned work under a high mechanical loading condition over a while. Whereas, chemical aging is a long-term interaction with the chemical environment, and due to this interaction material’s structure, composition, and morphology changes permanently. Thus, when a high mechanical load and chemical environment work at a time, it will be called conjoint mechanical-chemical aging.

2.4.1. Mechanism of Mechanical-Chemical Aging

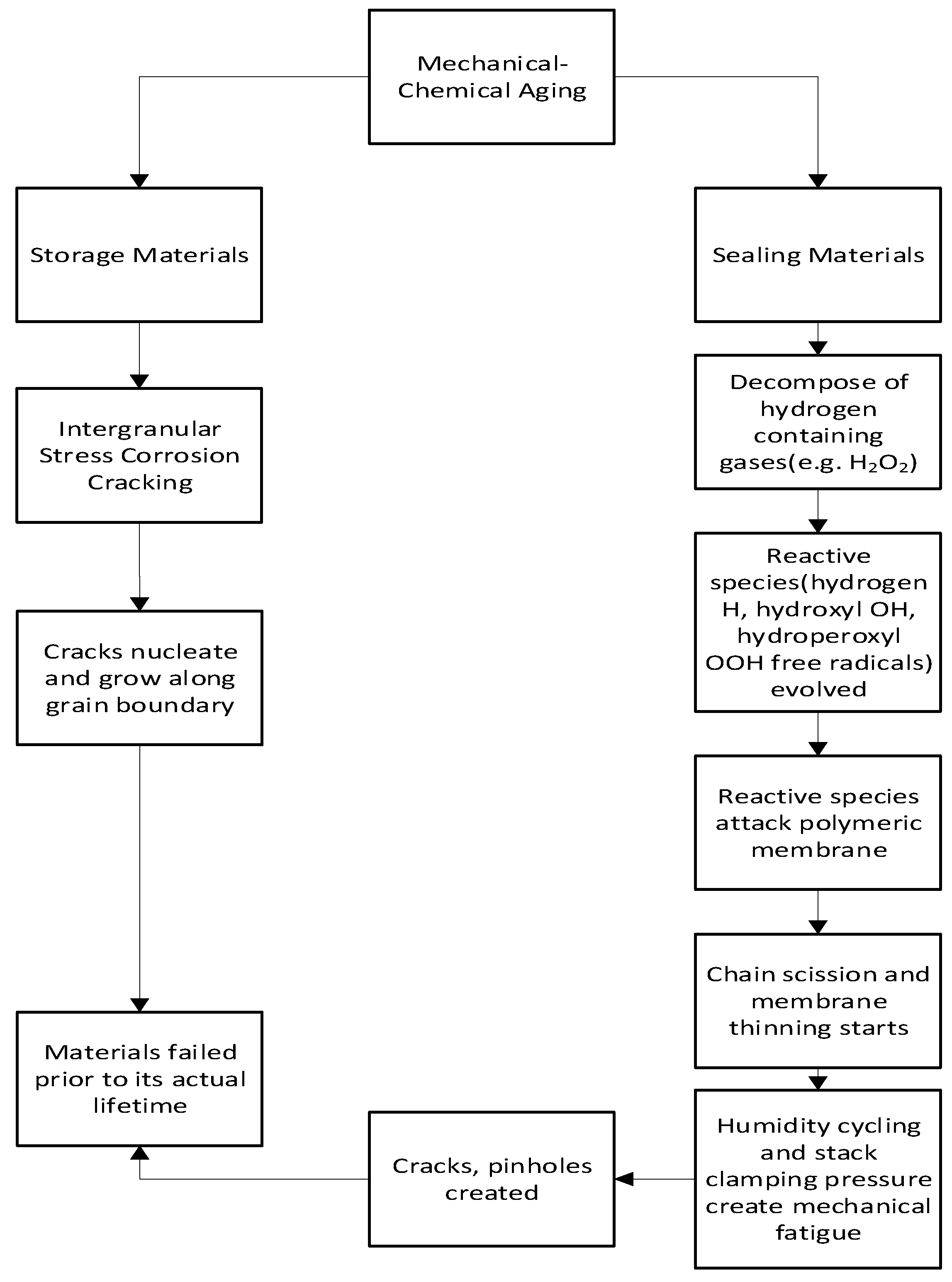

The conjoint mechanical and chemical aging is observed in hydrogen storage and sealing materials.

Figure 7 indicates the flowchart of mechanical-chemical aging.

2.4.2. Laboratory Test for Mechanical-Chemical Aging

Harris et al. [

55] conducted a laboratory test on Monel K-500, a precipitation-hardened Ni-Cu alloy susceptible to intergranular stress corrosion cracking under a hydrogen environment at 923K. The specimen was immersed in a 0.6M NaCl solution. A saturated calomel electrode was used, and the applied potential was -1000 to -1200 mV. In four heat treatment conditions, the under-aged and peak-aged specimens showed increasing susceptibility against intergranular stress corrosion cracking compared to an un-aged and over-aged specimen. Nykyforchyn et al. [

56] conducted a laboratory test where they tested ferrite-pearlitic X52 steel cylindrical, smooth, and pre-cracked samples into a solution of artificial brine mimicking onshore conditions where stress corrosion cracking could be created. The test was conducted both in the presence and absence of external polarization. In the absence of polarization aggressive environment did not show much effect as in the presence of external polarization. In the presence of external polarization, both specimens were affected.

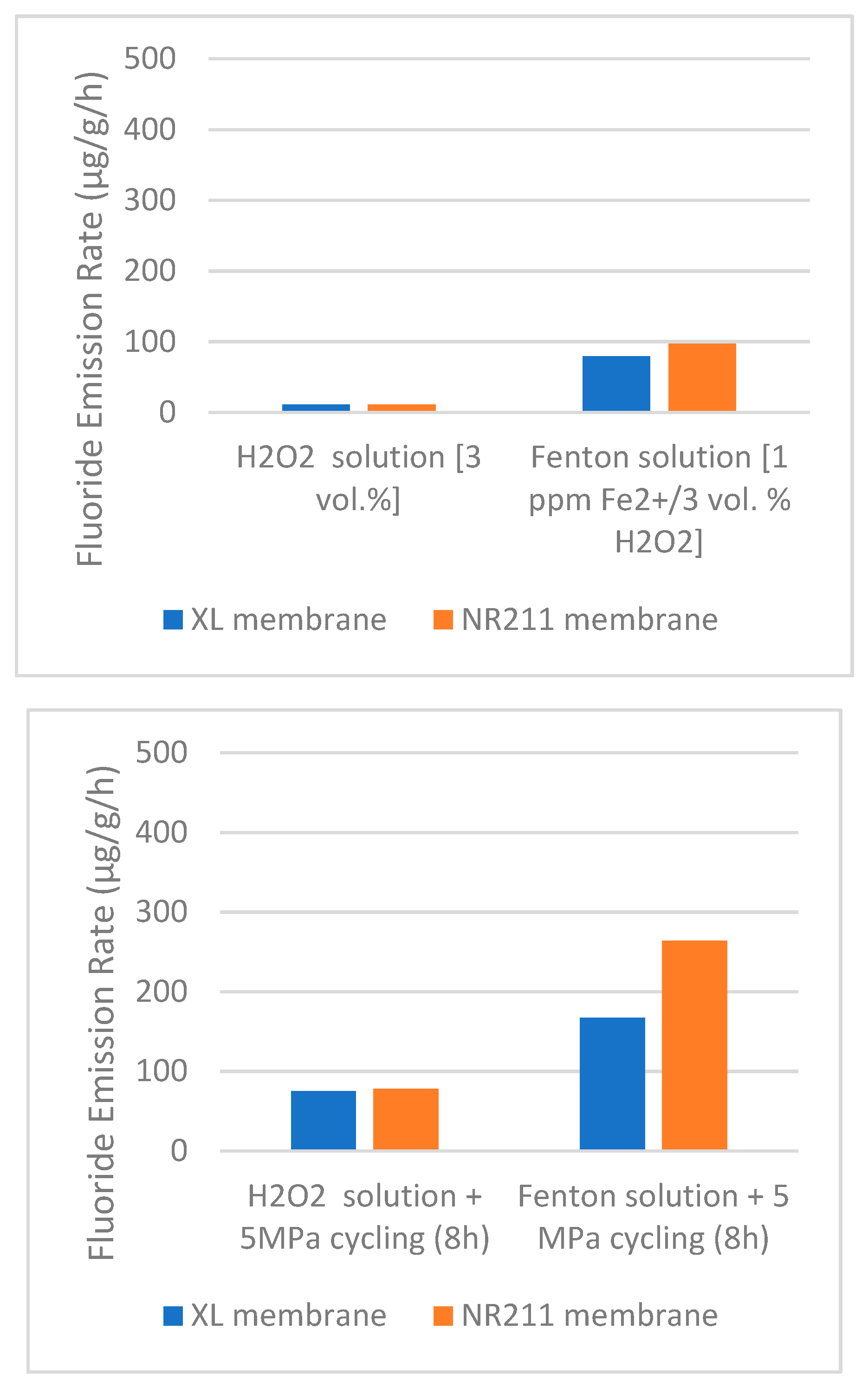

Robert et al. [

57] took a perfluoro sulfonic acid-based membrane and placed it in a degradation solution. At a time, the membrane was fitted with a universal testing machine for giving mechanical stress. Two types of solution were used one is mild (3 Vol% H

2O

2) and another is an aggressive solution called Fenton solution (3 Vol% H

2O

2 + 1ppm Fe

2+ ion). Mechanical fatigue was applied to create mechanical stress on the membrane. A cyclic compressive stress was applied on the channel ribs to reproduce one-hand swelling or shrinkage cycles, and static compressive stress was maintained for the stack clamping pressure on the membrane. In this experiment, fluoride emission rates (FER) were observed to predict the decomposition of the polymeric membrane. Post aging situation of the material was determined by Robert et al. [

57] by using a fluoride-ion selective electrode which measured the amount of the emission of fluoride ions. It was considered a reliable PFSA (perfluoro sulfonic acid) chemical degradation indicator. From the analysis of FER data, it was confirmed that aging was taking place there.

2.5. Thermo-Mechanical Aging

Combining both the thermal and mechanical aging process, when high mechanical load and temperature work at a time for the aging of material, then it can be called thermo-mechanical aging. Such situations are generally created in hydrogen fuel cells and sealing materials.

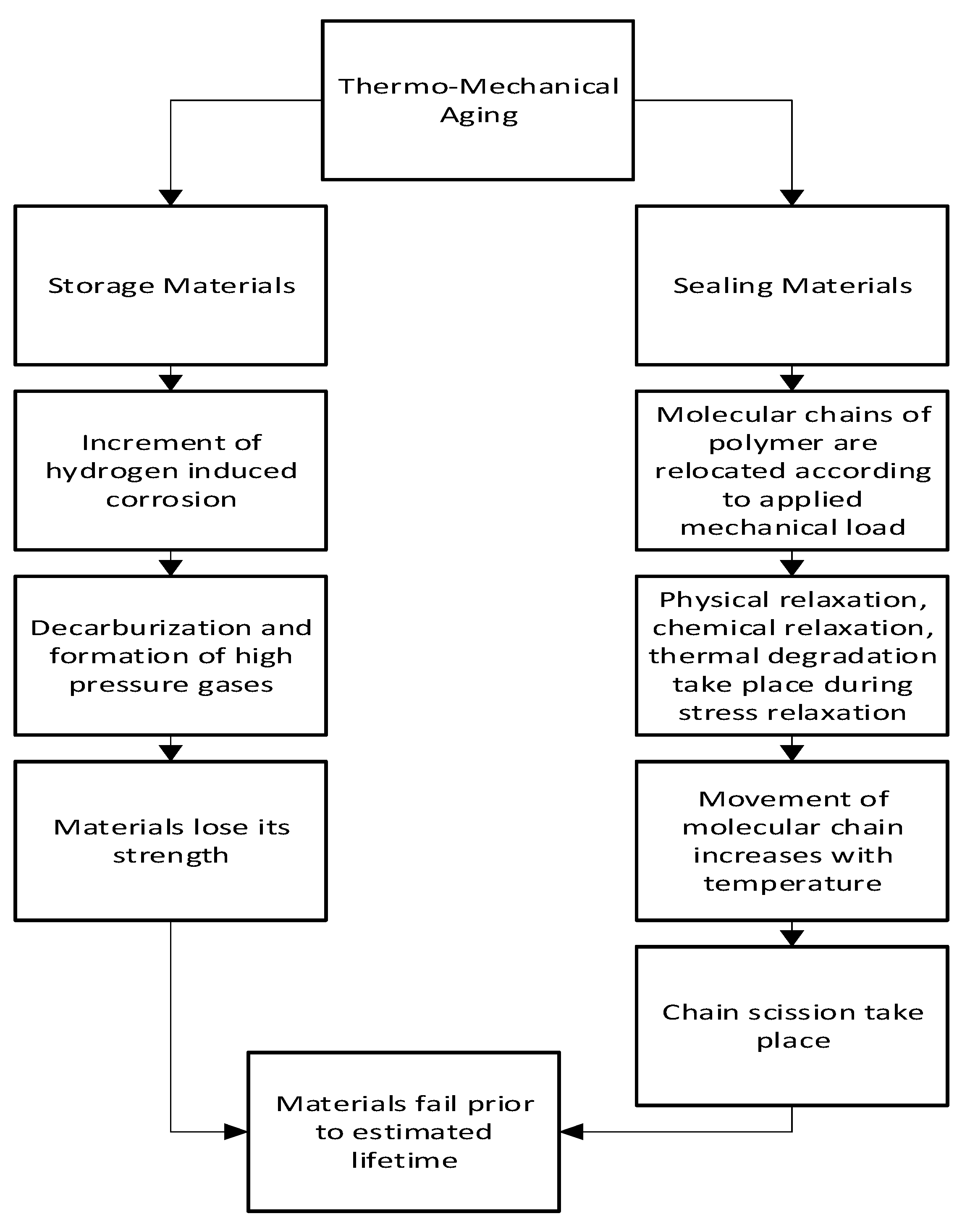

2.5.1. Mechanism of Thermo-Mechanical Aging

The diffusion of hydrogen affects the thermo-mechanical aging method. This is mainly seen in polymeric materials with viscoelastic behavior, if the strain is held constant viscoelastic materials show stress relaxation, and if stress is held constant, they show creep. Physical relaxation, chemical relaxation, and thermal degradation are some combined factors during stress relaxation in the polymer.

Figure 8 indicates the flowchart of thermos-mechanical aging.

Thermo mechanical aging occurs when hydrogen-induced corrosion in storage materials increases with increasing mechanical load and elevated temperature. Corrosion-induced hydrogenation of the materials, in combination with working stresses, may lead to the emergence of nano and micro-scale bulk damage. Hydrogen evolution may occur with corrosion, particularly in cracks caused by the local acidity of the corrosion media.[

16] During operation, materials experience in-bulk repeated damage due to decarburization and the creation of high-pressure hydrogen gases, causing them to lose their strength of materials. [

61]

In addition, when sealing material is subjected to mechanical load in a hydrogen environment, molecular chains of polymer are relocated. This causes stress relaxation which directly reduces the sealing force. Physical relaxation occurs first among other factors, then comes chemical relaxation, and later thermal degradation. With increasing temperature and operation cycles, the movement of the molecular chains increases which causes chemical reactions and chain scission. In this way, due to the stress relaxation behavior, polymeric material starts to loosen its sealing force as well as the sealing capability.[

62]

2.5.2. Laboratory Test for Thermo-Mechanical Aging

Balitskii et al. [

58] conducted a laboratory test on two steel specimens 05Kh12N23T3MR and 10Kh15N27T3B2MR, in a high-pressurized hydrogen environment and at elevated temperatures. A static tensional force was also applied to the temperature. At room temperature, the hydrogen action on both samples was minimum. But in high temperatures, 10Kh15N27T3B2MR was more sensitive to hydrogen embrittlement than 05Kh12N23T3MR but less than 60Kh3G8N8V and 12Kh18AG18Sh steel. NYKYFORCHYN et al. [

59] conducted a laboratory test on Cr-Mo-V steel at 450°C, and a tensile load was also applied to the sample. Their results show that the degradation of Cr-Mo-V steel is increased and the fatigue crack growth resistance is decreased due to hydrogen.

Cui et al. [

59] conducted a laboratory test using a liquid silicon rubber (LSR) gasket as a specimen. The test was done in two mediums air and water. Stress relaxation equipment was used in the experiment. During the experiment, constant deformation was applied to the sample, and the temperature was raised to 100 to 120°C. The test was done at different strain rates, temperatures, and stress levels. They used time-temperature superposition theory to construct a master curve that could predict the service life of the specimen. They found medium also affected the aging of the specimen. They found at 70°C, LSR service life could be 5000h at 60% of initial sealing stress. Below the 60% initial sealing stress, it was considered as leakage.

3. Durability Analysis of Hydrogen Sealing and Storage Materials through Aging Tests

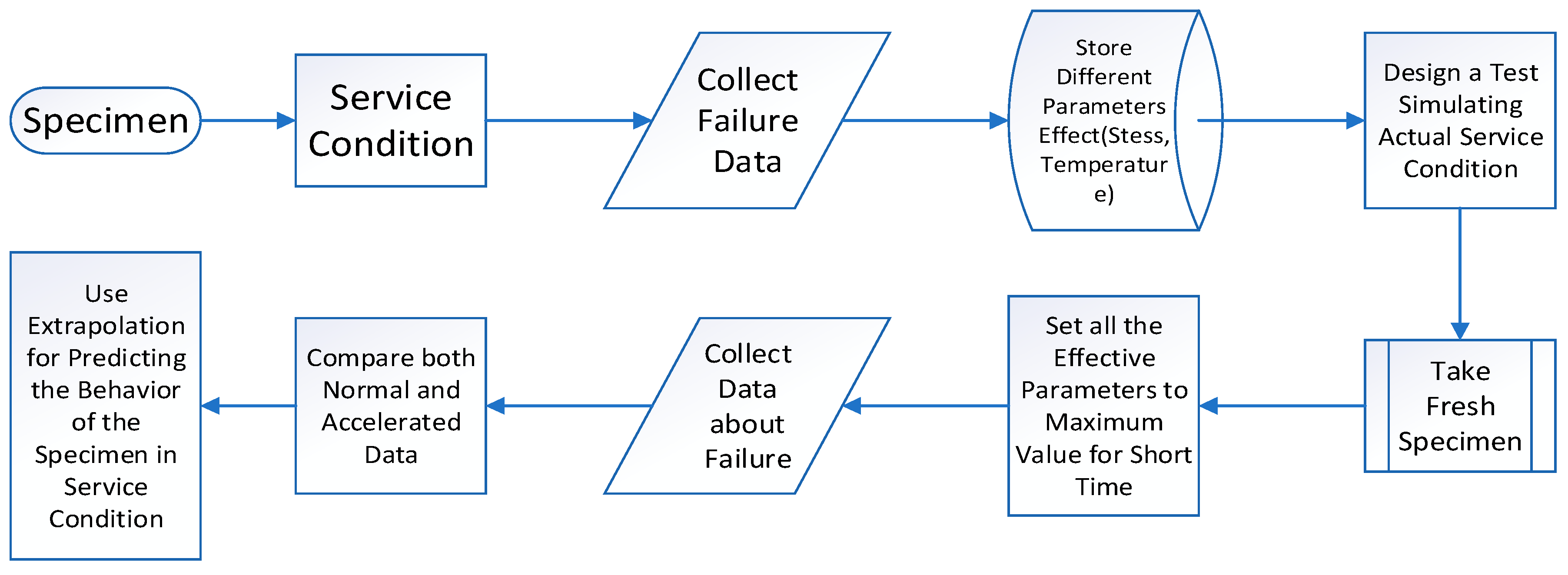

3.1. Durability Test Methods and Principles

An accelerated Durability Test (ADT) can be done to predict the durability of materials. It can be done to minimize the time and give a better prediction of durability. In a normal aging mechanism, materials are aged for a long time. The sample tends to deteriorate rapidly if the regular conditions undergo a shift to severe ones. In ADT, this principle is followed. The test procedure is presented in

Figure 9 with flowchart. With this test, metallic hydrogen storage materials and polymeric sealing materials may be compared. This test is used not only for testing durability but also for material comparison, quality control, and design information. In this technique, specimens are compared under both normal environments and accelerated conditions. Chemical abrasiveness, temperature, and pressure are held at their highest levels to simulate the worst scenario during an accelerated test cycle. Therefore, mechanical, chemical, electrochemical, and thermal failure mechanisms exist. [

69]. The specimens under normal circumstances and accelerated settings are compared, and the extrapolation technique is utilized to anticipate the service life and durability of the material. [

64,

65]

The main limitation of this test is the simulation of service conditions which is tough. As a result, the predicted value always has errors to a specific limit. Again, the activity of the materials found in harsh conditions is not always reflected in the mild condition. But keeping the problems aside, this test is a comprehensive test for predicting the material's durability, especially polymeric sealing materials[

60]. Burgess et al. [

61] conducted an accelerated durability test for a pressure relief device (PRD) in a hydrogen environment where they created the worst condition for the PRD that it could face in its service conditions. The medium-pressure hydrogen storage cylinder was protected by a valve which was the PRD here, and that was used to conduct the test. Maximum stress and temperature cycle were applied to the specimen, and the failure behavior was observed. From the result, they predicted the behavior of the 440C steel specimen. An accelerated stress test is a form of ADT used in the determination of the behavior of the proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cell. Polymeric sealing materials can be compared with PEM. In this system, failure modes are mechanical, chemical, electrochemical, and thermal. Thus, for an accelerated test stress cycle, chemical harshness, temperature, and pressure are kept at maximum to create the worst condition for PEM. Liu et al.[

62] and Kundu et al. [

63] conducted such an accelerated stress test for the Nafion membrane. Liu et al. [

62] conducted ADT for 10 cycles and each cycle consists of 100h. They found significant degradation take place at 500-600h of operation and at 1000h the membrane completely degraded. Kundu et al. [

63] found that over 4-5 days of ADT almost 20% of weight was lost. By extrapolating these data, the service life could be measured.

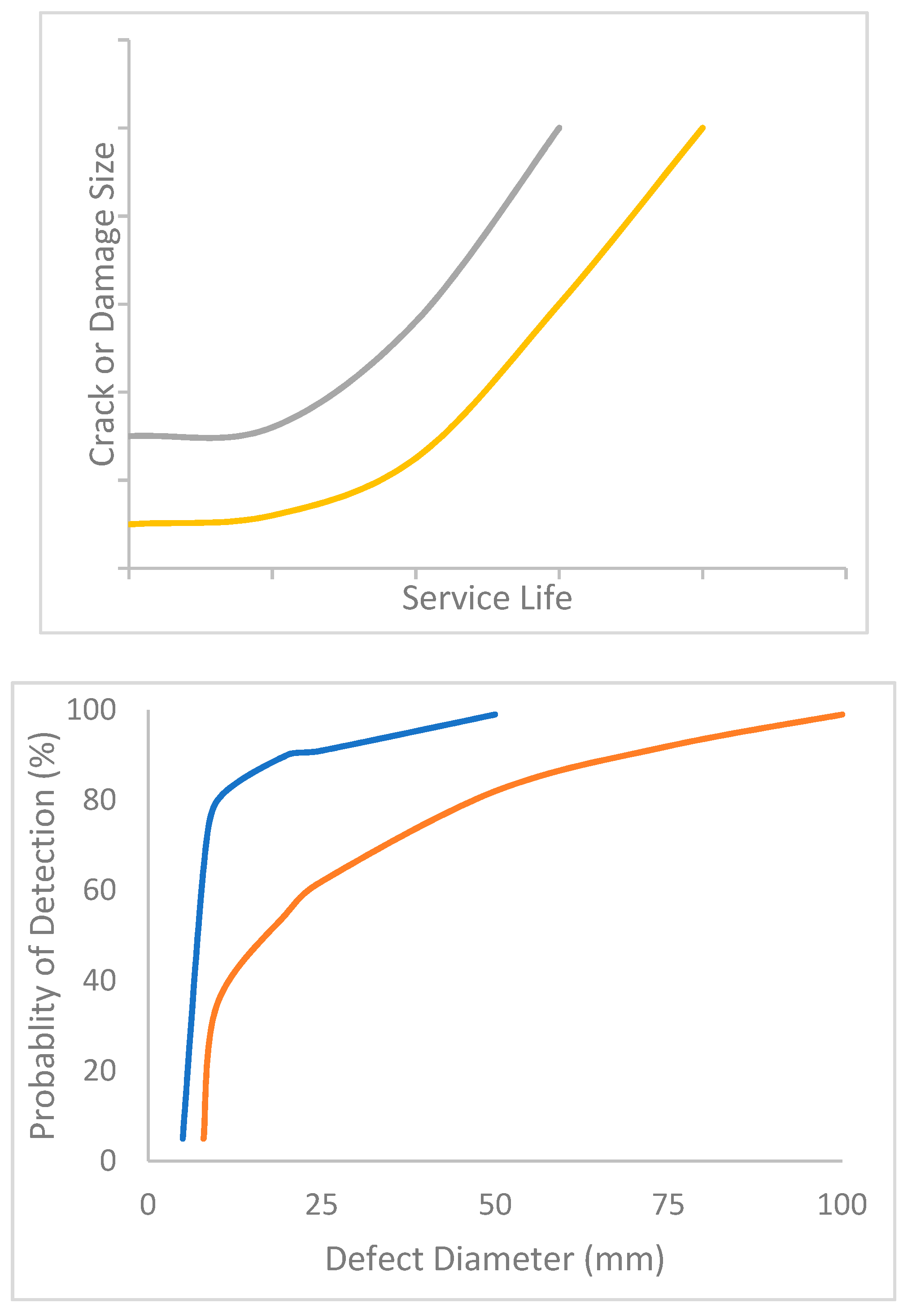

The service life of a material can be defined as the amount of time a material can provide proper service for which it was made. There is a relation between service life and crack defect size.

Figure 10 shows that after long-term use when materials spend a significant portion of their service life, the distribution of the crack and its size increase. Hence, the service life of a material can be predicted in a reverse method. In this method, crack defect size is measured using ADT, and service life can be predicted from that value. For detecting cracks in materials in a hydrogen environment, several tests can be performed. Such as changes of vibration characteristic of structure technique, acoustic emission technique, structure interrogation using lamb waves and ultrasonic using piezo transducer technique, eddy current, and ultrasonic technique, etc.[

64].

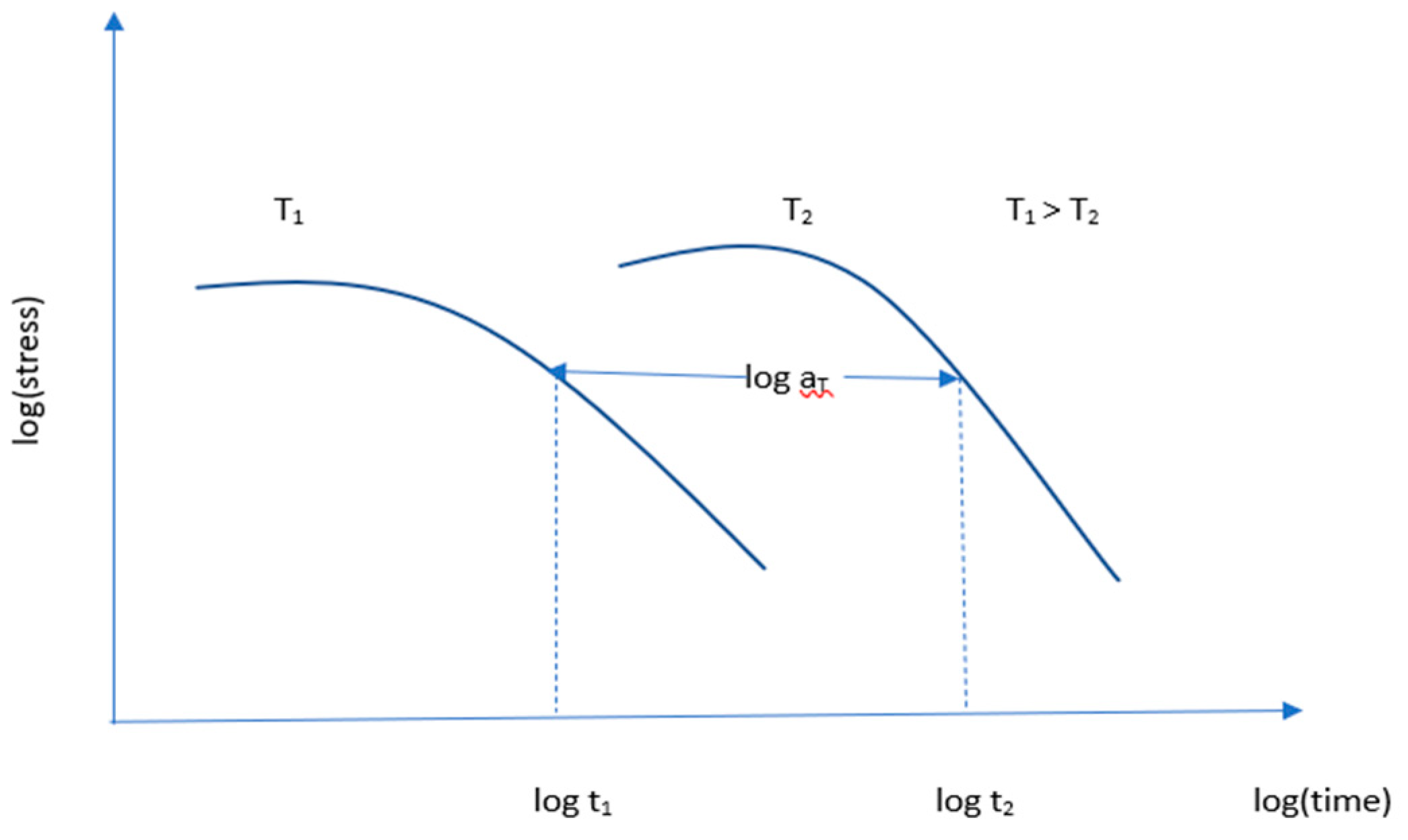

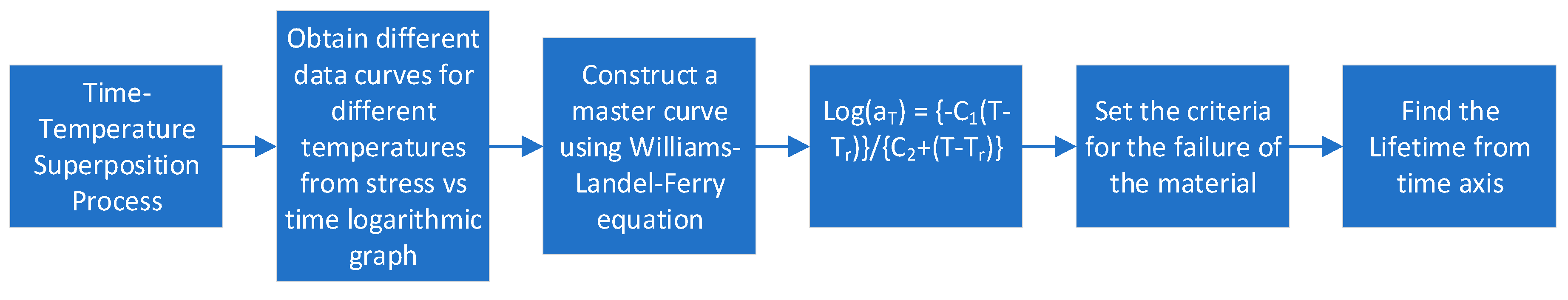

Time-Temperature Superposition (TTS) principle is an established principle for predicting service life. It is a commonly used method where a master curve is formed at selected reference temperatures. From this master curve, service life is predicted. The relationship between time t and temperature T for the mechanical response is described in the TTS principle[

65,

66] and the relation can be written mathematically as follow:

where, G

r = mechanical response, a function of time and temperature, T

1, T

2 = two different temperatures, t = time, a

T = shift factor

Figure 11 represents the shift factor a

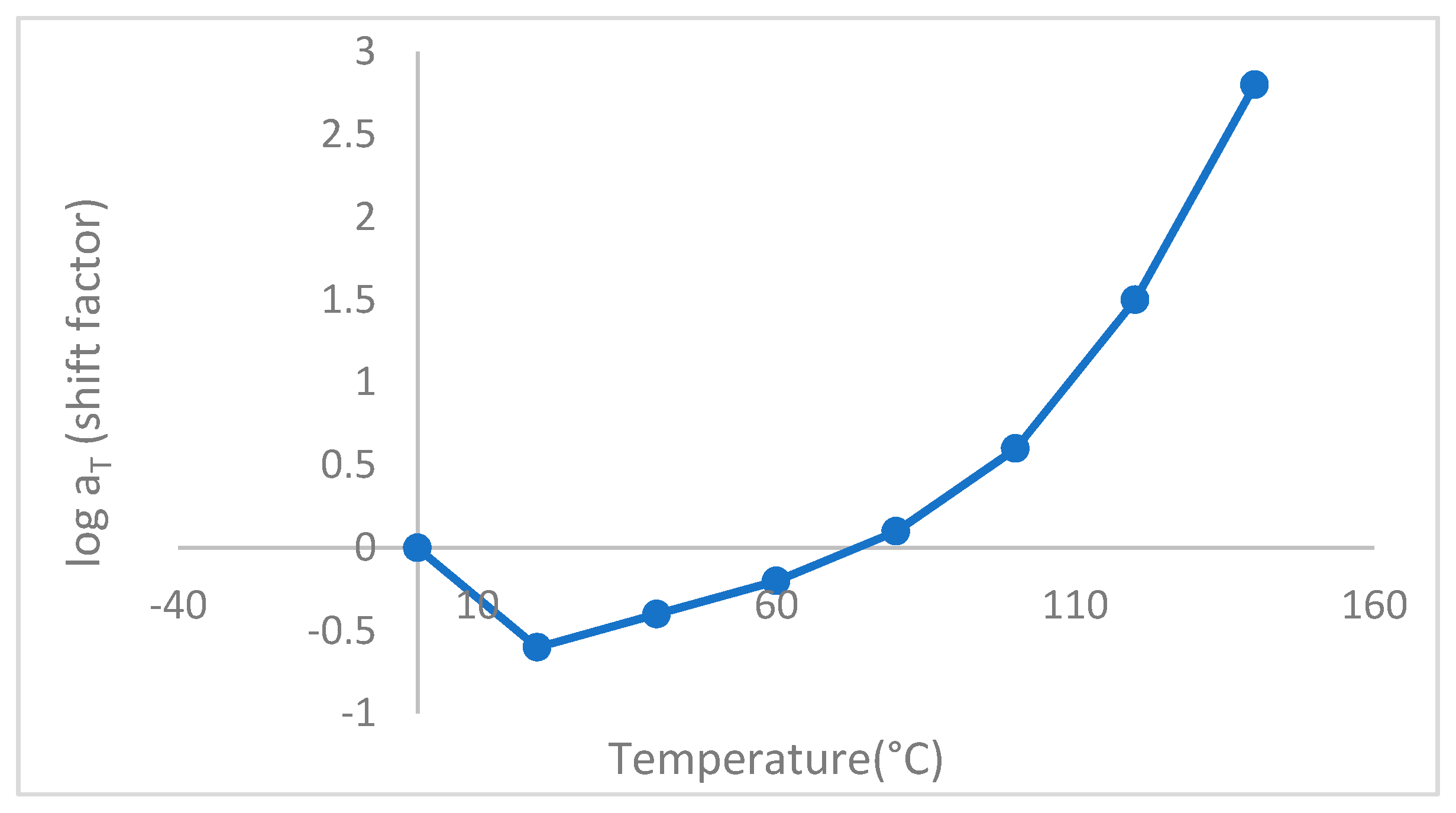

T and the TTS process which is a mathematical application of Boltzmann’s superposition principle. The principle states that time and temperature are equivalent. In two different temperatures, the same shape and time function of stress can exist. When the stress relaxation curve is presented on a logarithmic–logarithmic scale, this curve can be shifted to another temperature horizontally. The TTS principle is used to shorten the test time because it tests material for a shorter time at a higher temperature[

59]. Creep behavior and the stress relaxation of polymeric materials can be determined using this principle[

67]. For predicting the lifetime of a material using TTS, the process shown in

Figure 12 is followed.

Cui et al. [

59] tested LSR at three different temperatures 70°, 100°, and 120°C and obtained a stress versus time logarithmic curve. Using the Williams-Landel-Ferry equation[

68], they constructed a master curve and fixed 60% of stress for the threshold value of leakage. After that, they draw a line from 60% on the master curve. Then another line was drawn from the master curve intersecting point on the time axis. The value at which the line is cut on the time axis is the predicted lifetime of the material.

3.2. Service Life of Storage and Sealing Material under Simultaneous Multiple Aging

In the case of a hydrogen environment, failure of storage material can create a great disaster. Taking the thermal aging of steel into consideration, O. Z. Student [

25] found changes in the structure during laboratory aging for 40 h, which was observed after continuous operation of 140,000-190,000 h. Therefore, the service life of the steel can be predicted using ADT from here. During the storage of hydrogen, it makes chemical interaction with the vessel chamber and the transport pipes. Under chemical aging conditions, no such work was found where anyone was claiming the service life of any storage materials. For thermal aging, the predicted service life was 140,000-190,000 h. But in mechanical-chemical aging, the service life prediction was 5500h, and in chemical, it was 6000h which is a huge difference[

30,

34]. Thus, the intensity of thermal aging is comparatively lower than other methods, and it also varies depending on the service condition, materials used, environment, etc.

In fuel cells, if the sealing material of the membrane ages and somehow leaks, it can create a great disaster. [

70,

71]. Taking the chemical aging of a polymeric gasket material into consideration, it was found that the test time under an ADT environment of 6h could be equivalent to 27h of the lifetime of the specimen. This result was based on the time-concentration superposition theory, and it showed that under harsh conditions, the extrapolating lifetime was 4 times the experimental time. By using the TTS principle based on stress relaxation behavior, it was predicted that the service life of Silicon rubbers was at least 6000 h under the simulated fuel cell environment[

72]. When mechanical and chemical aging occurs in a system, the condition worsens more rapidly. Because due to chemical aging, the material becomes brittle and loses its elastic properties. If a mechanical load is applied to it at the same time, the process of aging will be accelerated as usual. A laboratory study found that under fuel cell operation where conjoint mechanical-chemical aging takes place the service life of a membrane is about 5500h[

73].

Here, one observable thing is that if the service is compared with each other, then the intensity of this aging can be understood. The service life of a membrane under chemical aging was predicted at 6000h. But when mechanical aging was added to the chemical aging, then the service life was reduced to 5500h. Thus, it is clear that the intensity of aging is higher in conjoint mechanical and chemical aging. But it is also important to know that chemical aging is more efficient than mechanical aging[

57].

4. Key Factors Affecting Aging under the Hydrogen Environment

Numerous key variables affect the aging mechanism of various aging processes of materials in a hydrogen environment, as is evident. Temperature, aging time, stress, thermal cycle, environment, hydrogen pressure, and hydrogen distribution are the primary factors affecting aging in a hydrogen-rich environment. The literature indicates the impact of factors, Zelenak et al. [

74] found high temperatures elevate hydrogen aging, resulting in the formation of reactive metal hydride composites or complex metal hydrides in storage materials. Eliezer et al. [

75] observed that the concentration of hydrogen had an impact on the aging behavior of titanium alloys in a hydrogen atmosphere, with greater concentrations resulting in more rapid aging. Therefore, for an adequate assessment of the serviceability of materials in a hydrogen environment, it is essential to take into account the operating conditions that can influence aging behavior.

4.1. Effects of Temperature

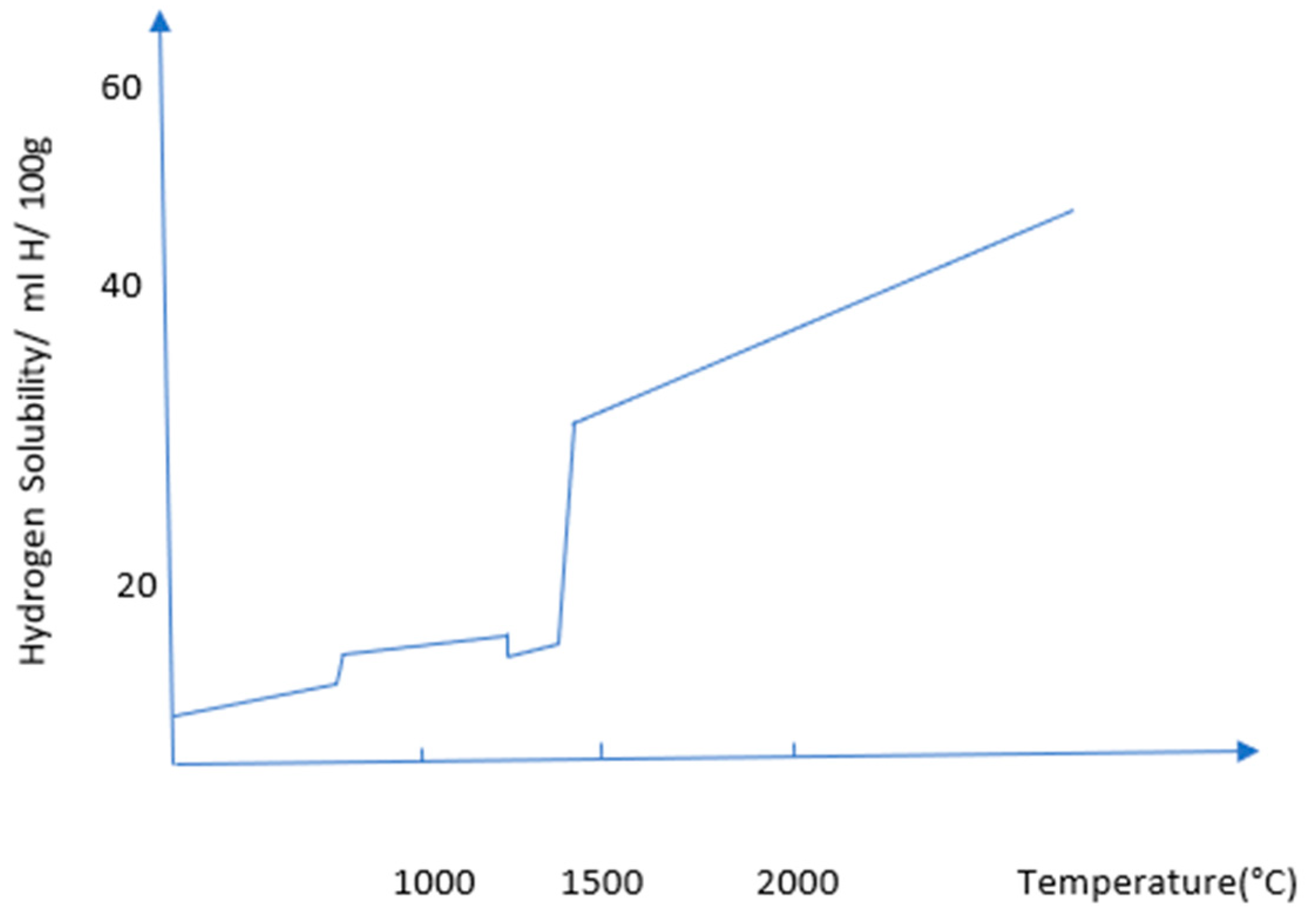

The temperature effect on hydrogen storage metallic materials can be described from the metal-hydrogen interaction point of view. Metals lose their strength due to hydrogen embrittlement. This phenomenon depends on hydrogen absorption, physical adsorption, transportation of hydrogen to the crack tip, transportation of hydrogen to tensile stress regions, etc. All of these factors are highly temperature dependent.

Figure 13 is showing that how the solubility of hydrogen increases with temperature. At 1000°C, the hydrogen solubility is showing less than 10 ml H/100g, which reached more than 40 ml H/100g at 2000°C.

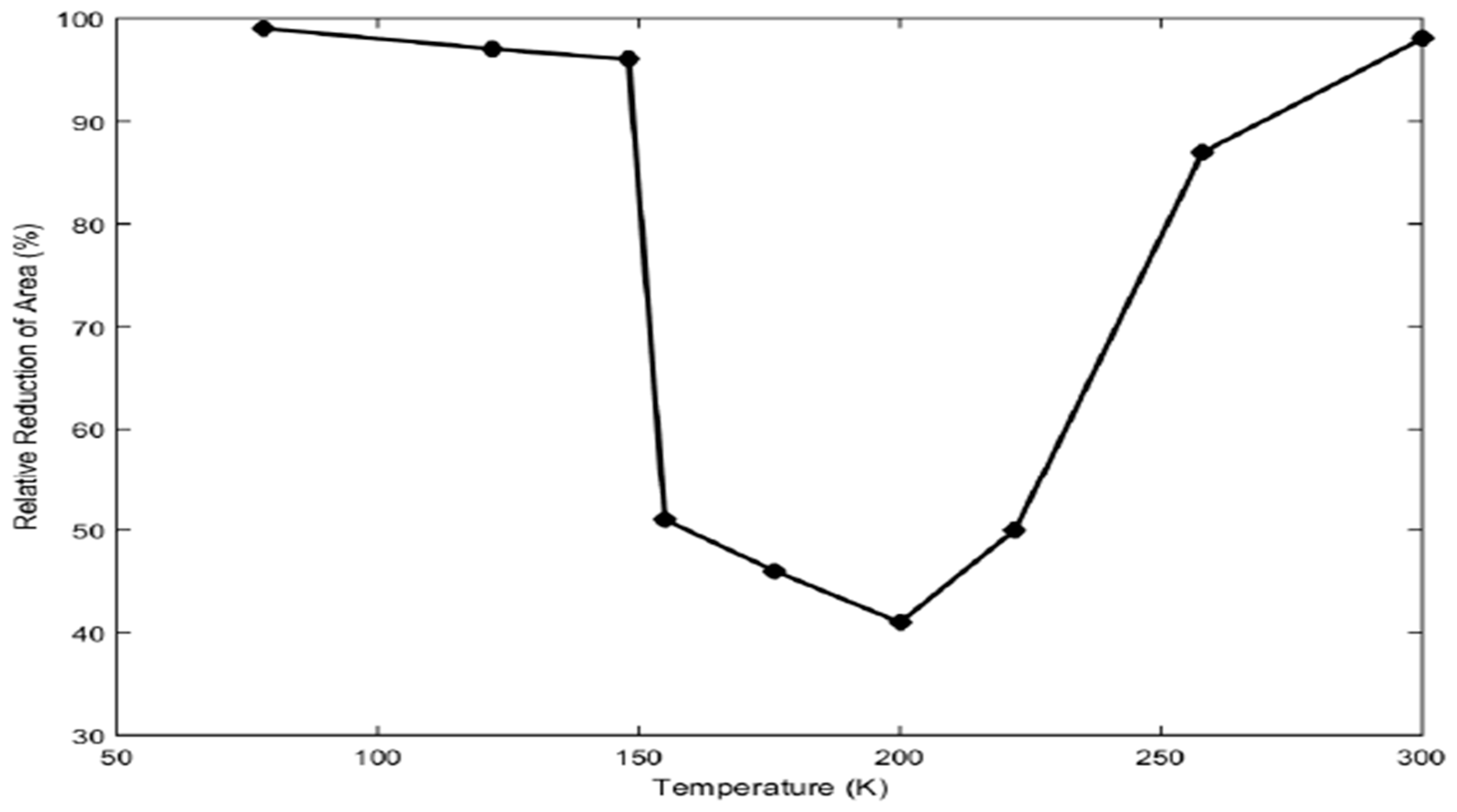

Figure 14 describes the relative reduction of the area, which is a measure of ductility that varies with temperature. At lower temperatures from 75° to 150°C, the effect of hydrogen on ductility is low due to the slow transportation rate, and at higher temperatures more than 250°C, the hydrogen effect is low as well because of the trapping of hydrogen by dislocation. But in the intermediate region from 150° to 250°C hydrogen has a significant impact on the ductility of the metal. In this intermediate region, the ductility of metal reduces significantly to about 40%.

Another important thing is that the effect of temperature due to hydrogen differs from material to material. For the polymeric gasket materials, Wu et al. [

78] found that with increasing temperature, mechanical properties of the sealing materials, including the tensile strength, elongation at failure, compression stress relaxation, and compression permanent deformation tend to decay. Dubovský et al. found [

79] in their work that high temperatures accelerate the degradation of the seal. Stress relaxation of polymeric sealing materials is very much dependent on the temperature. Chemical relaxation and thermal degradation increase with increasing temperature[

59].

Figure 15 indicates that temperature has a considerable effect on the stress relaxation of polymeric materials, and with increasing temperature shift factor increases sharply. Here, the shift factor is the degree of material's time acceleration in an isothermal environment. As the shift factor increases with temperature, the materials' aging accelerated.

4.2. Effect of Pressure

Hydrogen permeation into the metal increases with increasing pressure which enhances the embrittlement tendency of the metal. When hydrogen is stored in a container, it exerts a huge pressure on the container wall. If the container becomes a metallic one, the permeation of hydrogen through the metal can be higher, and the metal aging tendency can increase.[

80]. The increasing pressure also increases the interaction between the hydrogen and the sealing materials. As a result, the absorption of hydrogen increases, which eventually degrades the properties of the sealing material, which is discussed earlier.[

81]. Another important phenomenon takes place when the high pressure is released suddenly. Due to the sudden drop of pressure-volume of the inside gas increases, desorption starts. During the desorption process, bubbles are created, which create micro-cracks, the phenomenon is known as cavitation.[

82]

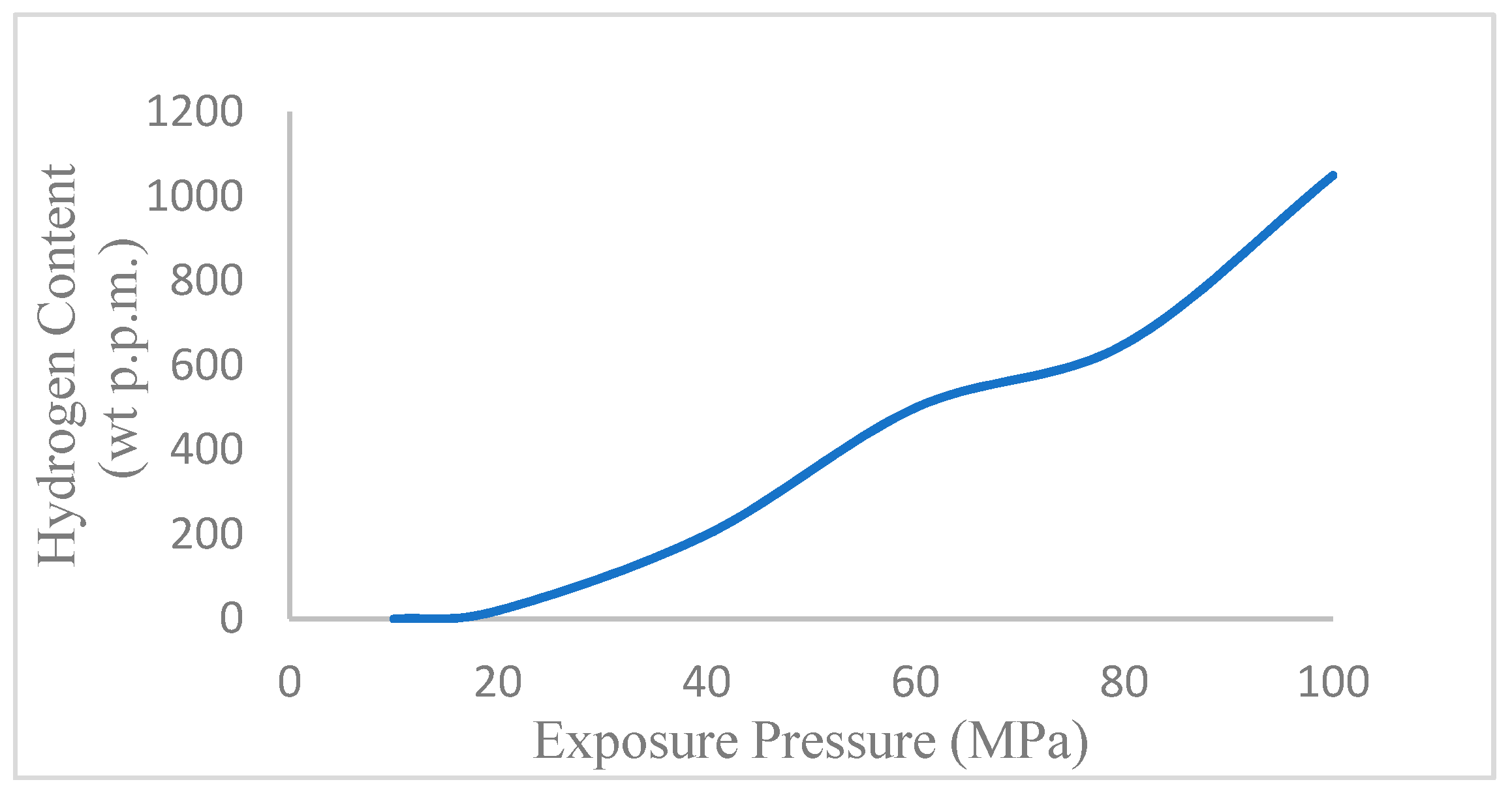

From

Figure 16, it is evident that, with increasing pressure, hydrogen has a higher tendency to dissolve in materials. At 20MPa, the hydrogen content was less than 50ppm, which reached almost 1000ppm at 100MPa. Because hydrogen is very small in size and with increasing pressure, it can easily penetrate through the materials.

4.3. Effects of Stress

Stress is an important factor that can affect the aging process significantly in a hydrogen environment. There are different types of stresses, such as thermal stress, chemical stress, mechanical stress, etc. Thermal stress is induced in materials due to temperature fluctuation. It can facilitate the aging process and this type of stress is highly related to thermal cycling. For harsher chemical conditions, chemical stress increases.

Robert et al. [

57] conducted an aging test using a perfluoro-sulfonic acid-based membrane. This type of membrane is degraded by the emission of fluoride ions when it reacts with chemicals. They tested their specimen in two stress conditions, static and cyclic. After testing, they found that when cyclic stress was introduced instead of static stress, the fluoride emission rate of the specimen was increased. From

Figure 17, the evidence of the prior statements is proved. The first graph indicates static stress condition and the second one is cyclic stress condition, and the result shows the fluoride emission rate is higher in cyclic condition. That means stress has a significant effect on the aging process.

4.4. Effects of Thermal Cycle

Thermal cycling is a cyclic process of rapid temperature change, where a material remains at a higher extreme at one phase and a lower extreme at the other. Due to thermal cycling, thermal stress is created in materials, which is called thermal aging. Thermal aging results from fatigue crack growth and depends on the number of cycles. Not only does the number of cycles affect the aging process but also the range of the temperature of the thermal cycle is also significant. A higher range of temperature difference can make more variation in the diffusion of hydrogen which can affect the aging process.[

25].

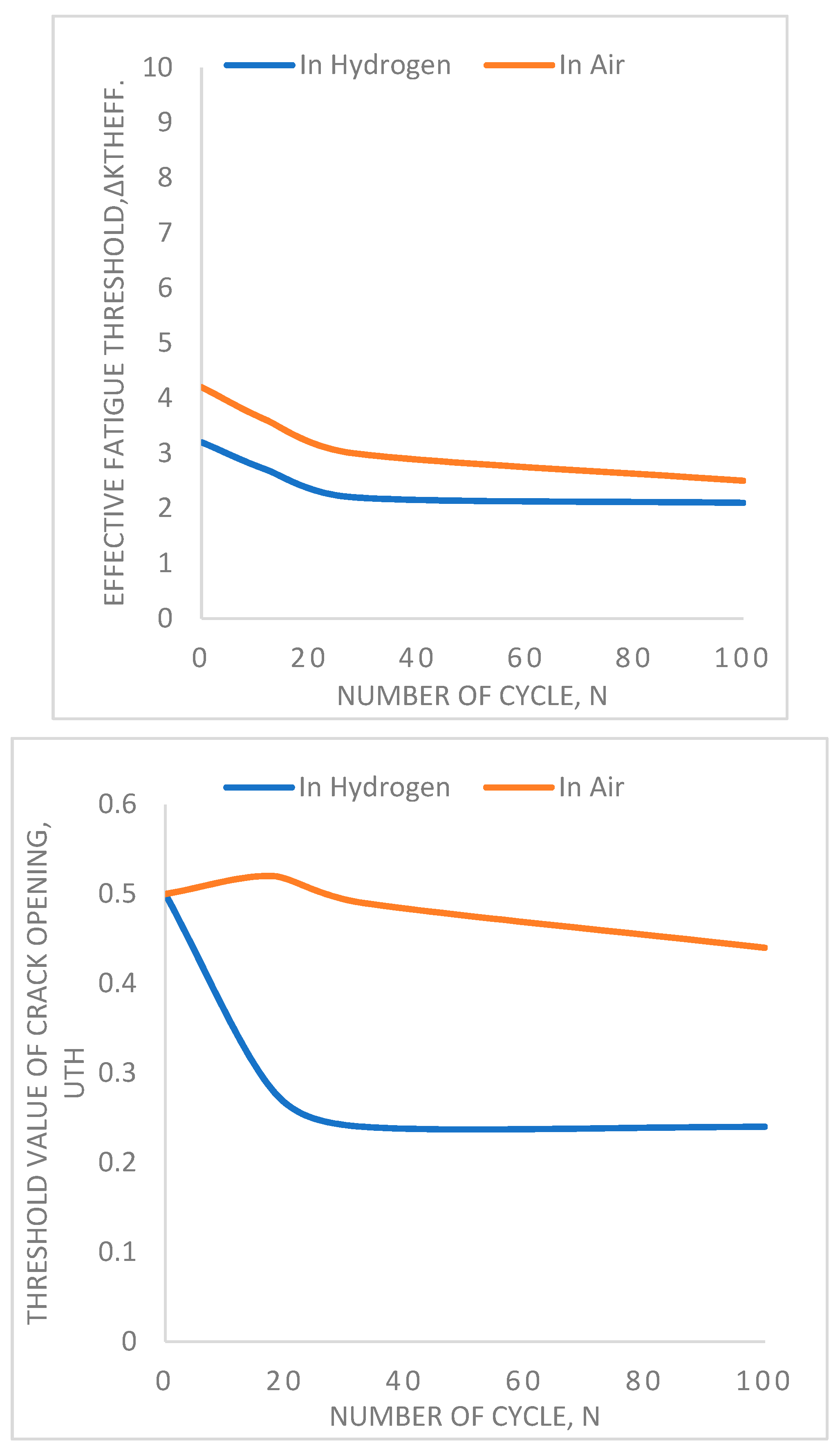

Figure 18 shows that an increase in the number of thermal cycles increases the tendency of fatigue failure of materials. In the left side figure, it is found that the threshold value for effective fatigue decreases with increasing the number of cycles. Because it is known that fatigue is a cyclic stress-dependent failure mechanism that increase with increasing number of the stress cycle. But the important thing to be noticed here is the behavior of hydrogen. When the test is done in a hydrogen environment instead of air, the threshold value decreases more than in the air. This evidence proves that thermal cycling significantly affects the aging mechanism of materials in a hydrogen environment. The right-side figure is also describing the same type of effect where the threshold value for crack opening decreases with an increasing number of cycles and hydrogen environment.

4.5. Effects of Environment

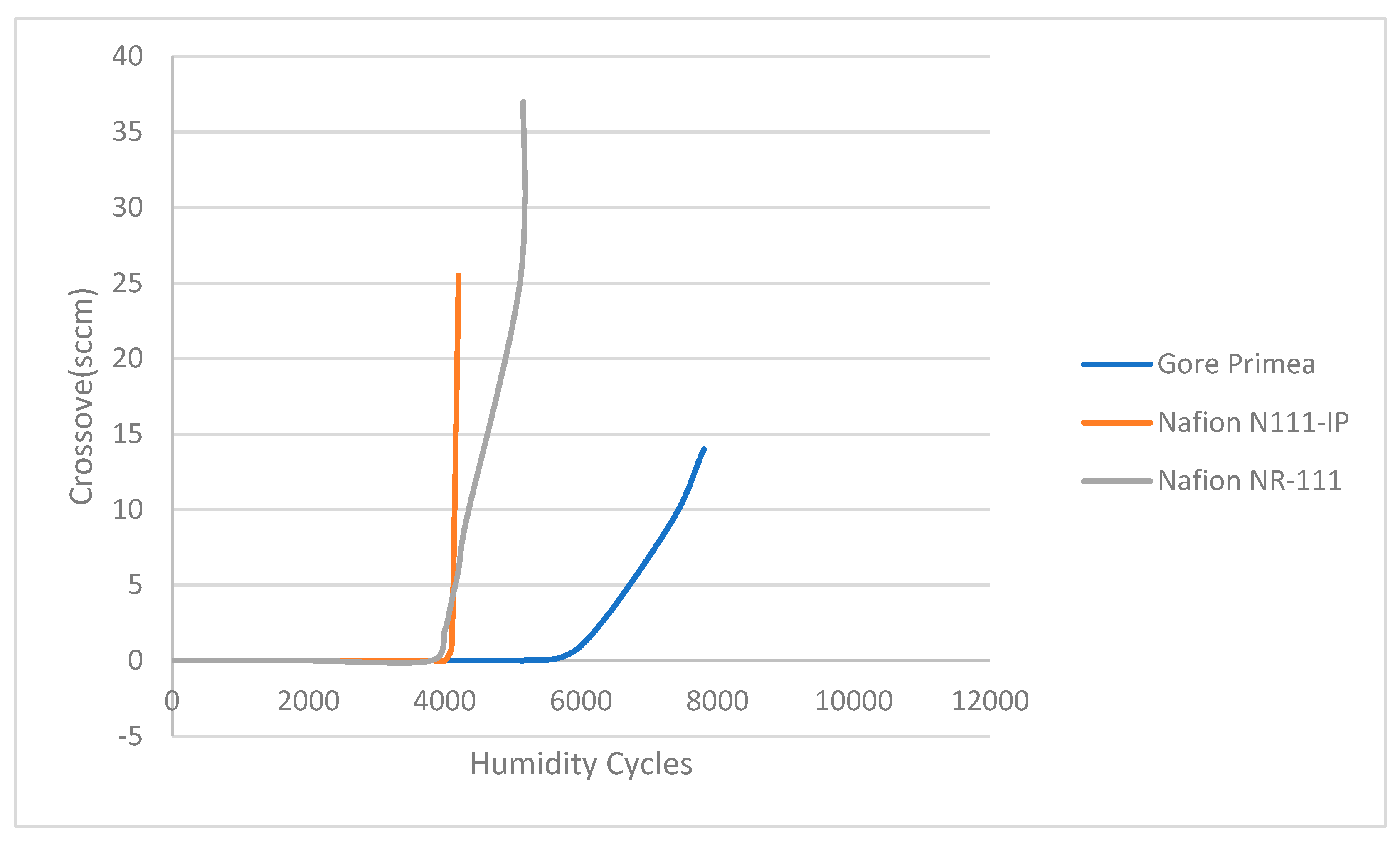

The environmental effect has a significant impact on the aging of sealing materials. Because these materials work in extreme conditions where they may be affected by the humidity cycle, the harsh chemical environment like a strongly acidic environment etc. As the humidity increases, the crossover leakage tendency increases. The crossover leakage is the tendency of the mixing of different gases (like, in proton exchange membrane fuel cell H

2 and O

2) leaking through the gasket material. Gittleman et al. [

73] tested three types of membranes, Gore Primea, Nafion N111-IP, and Nafion NR-111, in different humidity cycles. The result of the crossover tendency is shown in

Figure 19.

Figure 19 shows that by increasing the humidity cycle to the threshold value crossover tendency of every material increases in a hydrogen environment. This evidence proves that the humidity cycle has an effect on the hydrogen aging of the materials.

The harsher environment also affects the hydrogen aging process of the materials. In

Figure 17, the H

2O

2 environment is mild, whereas the Fenton solution environment is harsh. The graph shows when the environment approaches harsh conditions the fluoride emission rate increases significantly, which means the aging is also increasing. The pressure of the hydrogen also affects the aging process. Cracks are formed in materials due to the fluctuation of the hydrogen pressure. This pressure creates stress on the defective sites and forms cracks [

25]. As a result, materials fail before their expected lifetime, and this phenomenon is known as aging.

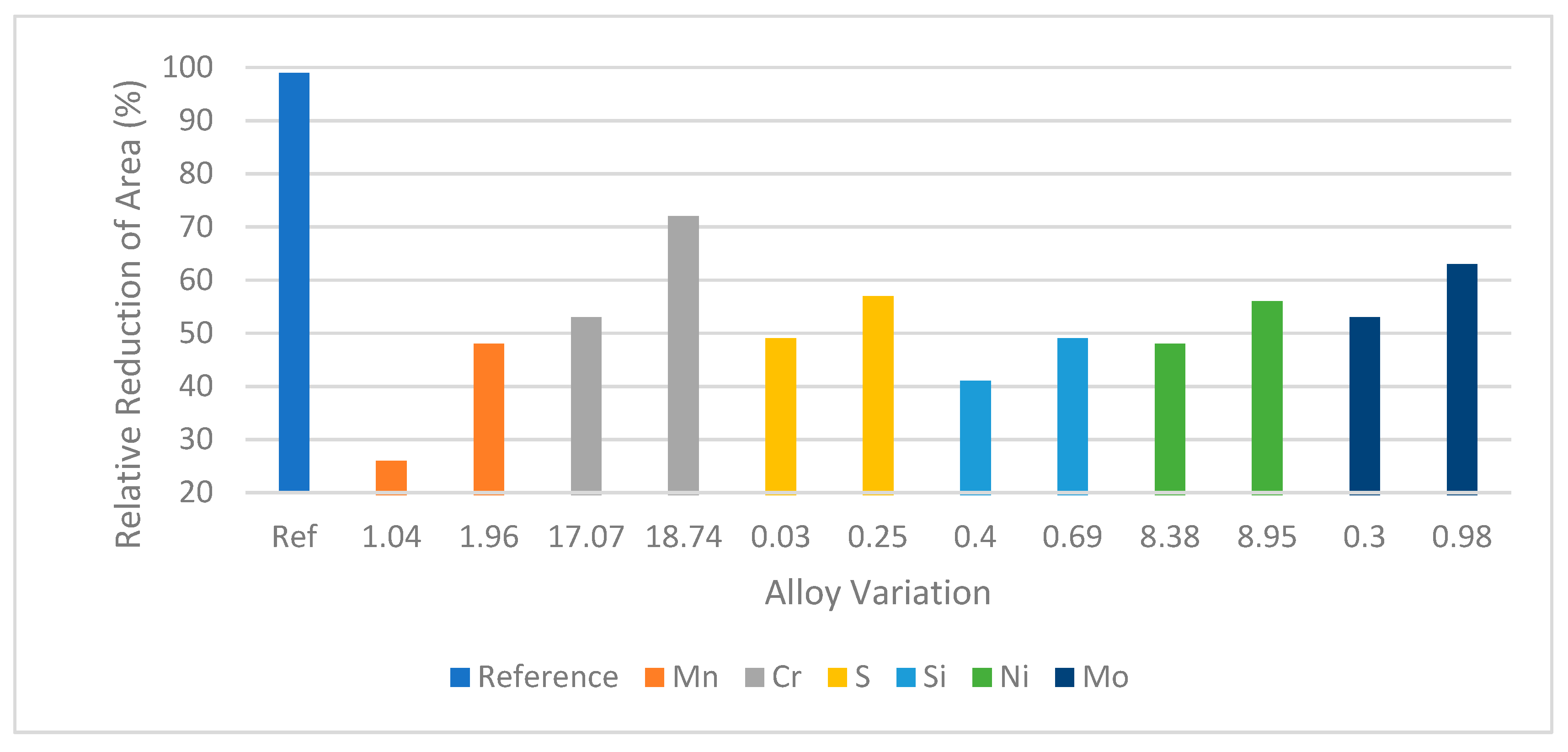

4.6. Effects of Alloying Elements

Alloying elements have effects on the degradation of hydrogen storage metallic materials. Martin et al. [

83] found that increasing alloying elements percentage in stainless steel increases the relative reduction of area in the hydrogen environment.

Figure 20 shows that the hydrogen embrittlement tendency of stainless steel decreases with increasing alloying elements. They used Mo, Ni, Si, S, Cr, and Mn as alloying elements. Among these alloying elements Si, Mn, and Mo show much resistance to hydrogen embrittlement compared to others.

In high-strength steel, chemical heterogeneity is intentionally created by introducing Manganese (Mn), enhancing hydrogen resistance. Sun et al. [

84] found manganese (Mn) in high-strength steel created a manganese-rich zone within the microstructure which restricted the stability of the hydrogen phase and arrested the micro-cracks produced by hydrogen. In Aluminum alloys, alloying elements have two different types of effects. Anyalebechi [

85] found adding Cu, Si, Zn, and Fe decreases hydrogen solubility, whereas Mg, Li, and Ti increase solubility. So, it is clear that some alloying elements have the tendency to increase hydrogen solubility in the alloy and some others have the tendency to restrict it. The alloying elements which increase the hydrogen solubility tendency in alloys are responsible for increasing the aging tendency of material in a hydrogen environment.

5. Research Gap Analysis

It is crucial to predict the operational degradation of laboratory materials, especially for novel materials, manufacturing, or processing technologies. There is not enough research on the stability of complex properties of the materials for long-time operations in a hydrogen environment. A comprehensive exploitation should be considered primarily to propose any operation; like a new pipe welding technology with higher performance, higher mechanical properties, and high resistance to hydrogen-induced cracking. Because, it is known that welding is a very important and widely used fabrication method, and due to hydrogen-induced cracking during welding, the aging of the materials is facilitated and materials fail before finishing their full life. For most of the metal alloys, no known published data is found for creep, fatigue, and impact of gaseous hydrogen on storage materials [

86], which indicates limited general knowledge about the materials and the performance of materials in the hydrogen environment. There is a gap in research on actual material grades in industry-mandated parameters and actual operating conditions[

3]. Therefore, hydrogen compatibility with the mechanical properties of storage materials is needed to be extensively studied.

According to Ogawa et al., the precipitation-hardened alloy shows low HE susceptibility and high thermal conductivity on the lab-scale [

31]. The fracture toughness may be further increased by adding required alloying elements and appropriate heat treatments to enable practical applications such as heat exchangers exposed to high-pressure hydrogen. Given that, several types of hydrogen damage have been observed in pipeline steel with various microstructures. The impact of each microstructural phase on HE needs to be elucidated through careful investigation. Some researchers contend that martensitic microstructure or ferritic pearlite are less preferred for HIC resistance than bainitic ferrite and acicular ferrite, however, the available data has stayed either conflicting or less convincing.[

87,

88]. The impact of hydrogen vacancy interactions on ductility, quasi-brittleness, and fatigue is yet to be explicitly explored. Srinivasan et al. reported that hydrogen vacancy interaction has a detrimental impact on austenitic, ferrite steels as well as Ni alloys, but further investigation is necessary. It is observed that hydride formation plays an important role in the hydrogen embrittlement behavior of alloys [

89]. But the hydrogen charging conditions under which hydride formation would be negligible have not yet been thoroughly investigated. According to Michler et al., the Hydrogen embrittlement effect for metals in a hydrogen environment normally begins at the gas-metal interface. Mechanisms related to hydrogen-material interactions are likely the rate-limiting steps in the hydrogen reaction chain.[

90]. There is a lack of understanding about the mechanisms that would allow such effects to be measured. Simulation tools may offer a framework to investigate, given that calculations using density functional theory have shown positive results.

According to the literature, it is asserted that the experimental hours exactly correspond to the amount of in-service degradation. For instance, it is stated that 140,000 to 190,000 hours of in-service degradation is equivalent to a lab experiment lasting 40 hours[

25]. But the correlation between service life and laboratory accelerated degradation is not explicitly stated, as laboratory experiments are often conducted in a controlled environment, and actual working conditions differ when a material operates in a hydrogen environment. There is still a lot of uncertainty regarding the precise mechanism by which hydrogen damage can occur in non-hydride-forming materials. Several mechanisms have been proposed, such as Adsorption Induced Dislocation Emission (AIDE), Hydrogen Enhanced Decohesion (HEDE), and Hydrogen Enhanced Localized Plasticity (HELP). These can take place simultaneously, with stress, temperature, and environment[

87]. The ideal failure mechanism for HE is still not comprehensive due to the difficulties in obtaining data at the atomic level and the inadequate capabilities of characterizations.

The literature discussed hydrogen aging, most of them had tested their sample by immersing in different chemical solutions such as H2O2 or acidic fluoride solutions or combined with natural gas, rather than pure hydrogen. Since liquid or gaseous hydrogen is directly used in the storage or pipelines of hydrogen infrastructure, the results collected in the lab may differ to variable degrees. Pipelines made of high-strength steel are susceptible to higher fatigue crack growth (FCG) rates in a hydrogen environment. Lower loading rates and load cycle frequencies, as well as load dynamics, can also affect FCG rates and be subjected to changes at different process conditions or upsets. Existing models and simulations are developed assuming minor displacement conditions and micro-scale yielding, which are typically not true for high-strength pipeline steels, hence scaling them up to greater scales is challenging.

Without applying external stress, the hydrogen concentration at the interface is considered minimal, which results in a lower alloy embrittlement effect. But the interaction of hydrogen at the interface is a complicated phenomenon and yet not explicitly understood. Extensive research on simulating hydrogen diffusion in the involvement of numerous bulk cracks has still been lacking. It is challenging to predict structural integrity when several cracks are present in a hydrogen atmosphere. To better comprehend and explain the propagation of such cracks due to strong field interactions at the tip of the crack, several speculative models have been put forth in the literature. But the distribution and amount of absorbed hydrogen cannot be well described by any model, preventing it from providing sufficient details.

In chemical aging, the absorption of hydrogen increases the hardness of metals and leads to hydrogen embrittlement. But the impact of hydrogen on polymeric materials is yet not comprehensively investigated. Sealing materials exposed to high-pressure hydrogen cycles and high decompression rates may suffer internal damage, such as cavity formation. Therefore, the wear and friction characteristics of sealing materials used in the hydrogen infrastructure must be studied to comprehend the compatibility in a high-pressure hydrogen atmosphere.

Raising the crosslink density of O-ring materials can lessen volumetric expansion upon decompression and lead to reduced free-volume pore dimensions.[

82]. As a result, offering possible sites for hydrogen gas localization is the first step toward cavitation-induced failure. But the damage progress can only be assessed for transparent graded O-rings, while only 2D projections of cavities can be provided.[

91]. Improved barrier properties were seen when Sun et al. and Bandyopadhyay et al. used 2D filler approaches in rubber materials to reduce hydrogen gas permeability[

92,

93]. But there is significant room for research for adding novel filler approaches to minimize the current limitations of polymeric seals in hydrogen energy systems.

6. Conclusion

Sustainable energy source, along with eco-friendly behavior is one of the most important global demands of today’s world. Hydrogen, one of the most abundant elements of earth, has the ability to fulfill this demand. But storing and sealing hydrogen is very challenging due to its high aging tendency. Materials in a hydrogen environment degrade and deteriorate faster than expected time and fail before their actual lifetime. This behavior of materials under a hydrogen environment is known as hydrogen aging. This review article discusses different types of aging that materials face under a hydrogen environment such as thermal aging, chemical aging, mechanical aging, mechanical-chemical aging, and thermo-mechanical aging, with their mechanism. Some laboratory-based aging tests are also discussed for substantial proof of these aging processes. Different types of parameters that can affect the aging processes are also discussed. Such as temperature, pressure, stress, thermal cycle, environment, and alloying elements. For predicting the service life of materials, time-temperature superposition theory is a very popular method. The accelerated durability test is a famous aging test that helps time-temperature superposition theory predict the service life. The principles of both methods are discussed in this paper. At the end of this review article, different research gaps are discussed where further research is needed for effective storing and sealing hydrogen. It is very much essential to store and seal hydrogen effectively. Because the future of the hydrogen industry is highly dependent on these, without effective storage and sealing the efficiency, application of this energy source can be hampered significantly, as discussed in this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AKM A.H, A.N.S, ZTM. methodology, AKM A.H, A.N.S, ZTM.; validation, M.M.H.B, P.K, A.N.S. formal analysis, M.M.H.B, P.K, Z.S.; investigation, A.N.S.; resources, AKM A.H.; data curation, A.N.S, ZTM; writing—original draft preparation, AKM A.H, ZTM; writing—review and editing, M.M.H.B, P.K, Z.S; visualization, A.N.S, M.M.H.B, P.K, Z.S.; supervision, P.K, Z.S; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M. Yue, H. Lambert, E. Pahon, R. Roche, S. Jemei, and D. Hissel, “Hydrogen energy systems: A critical review of technologies, applications, trends and challenges,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 146, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Nicoletti, N. Arcuri, G. Nicoletti, and R. Bruno, “A technical and environmental comparison between hydrogen and some fossil fuels,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 89, pp. 205–213, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Balasooriya, C. Clute, B. Schrittesser, G. P.-P. reviews, and undefined 2022, “A review on applicability, limitations, and improvements of polymeric materials in high-pressure hydrogen gas atmospheres,” Taylor Fr., vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 175–209, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. F.-D. H. and F. C. Program and undefined 2010, “Hydrogen safety training for first responders,” hydrogen.energy.gov, Accessed: Mar. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/review10/scs015_fassbender_2010_o_web.pdf.

- H. Li et al., “Safety of hydrogen storage and transportation: An overview on mechanisms, techniques, and challenges,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352484722008332.

- Barrera et al., “Understanding and mitigating hydrogen embrittlement of steels: a review of experimental, modelling and design progress from atomistic to continuum,” J. Mater. Sci., vol. 53, no. 9, pp. 6251–6290, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- “Handbook on Ageing Management for Nuclear Power Plants - Google Scholar.” https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Handbook+on+Ageing+Management+for+Nuclear+Power+Plants&btnG= (accessed Mar. 13, 2023).

- R. J. Hansler, L. J. Bellamy, and H. A. Akkermans, “Ageing assets at major hazard chemical sites – The Dutch experience,” Saf. Sci., vol. 153, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Research Report 509 - Plant ageing: Management of... - Google Scholar.” https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Research+Report+509+-+Plant+ageing%3A+Management+of+equipment+containing+hazardous+fluids+or+pressure+%282006%29&btnG= (accessed Mar. 18, 2023).

- ARIA, “Catastrophic Explosion of a Cyclohexane Cloud: Flixborough United Kingdom,” no. May, pp. 1–9, 2008, [Online]. Available: http://www.aria.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/wp-content/files_mf/FD_5611_flixborough_1974_ang.pdf.

- H. and S. Executive, Public report of the fire and explosion at the ConocoPhillips Humber refinery on 16 April 2001. Health and Safety Executive.

- U.S. DOE, “Lessons Learned Database,” p. 20, 2008, [Online]. Available: www.eh.doe.gov/DOEll/.

- “Case Study: Power Plant Hydrogen Explosion - WHA International, Inc.” https://wha-international.com/case-study-power-plant-hydrogen-explosion/ (accessed Jun. 15, 2023).

- “CSB Investigation Finds 2010 Tesoro Refinery Fatal Explosion Resulted from High Temperature Hydrogen Attack Damage to Heat Exchanger - General News - News | CSB.” https://www.csb.gov/csb-investigation-finds-2010-tesoro-refinery-fatal-explosion-resulted-from-high-temperature-hydrogen-attack-damage-to-heat-exchanger/ (accessed Jun. 15, 2023).

- U. Diebold, “The surface science of titanium dioxide,” Surf. Sci. Rep., vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 53–229, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Z. V. Slobodyan, H. M. Nykyforchyn, and O. I. Petrushchak, “Corrosion resistance of pipe steel in oil-water media,” Mater. Sci., vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 424–429, May 200. [CrossRef]

- E. Ohaeri, U. Eduok, and J. Szpunar, “Hydrogen related degradation in pipeline steel: A review,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 43, no. 31, pp. 14584–14617, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Hayden and D. Stalheim, “ASME B31.12 Hydrogen Piping and Pipeline Code Design Rules and Their Interaction With Pipeline Materials Concerns, Issues and Research,” Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. Press. Vessel. Pip. Div. PVP, vol. 1, pp. 355–361, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharma, S. G.-R. and sustainable energy reviews, and undefined 2015, “Hydrogen the future transportation fuel: From production to applications,” Elsevier, Accessed: Mar. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032114010405.

- J. Yamabe, S. Nishimura, A. K.-S. I. J. of M. and, and undefined 2009, “A study on sealing behavior of rubber O-ring in high pressure hydrogen gas,” JSTOR, Accessed: Mar. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26282777?casa_token=K9af06EzU1IAAAAA:_7GegdsxzpVSb9S4fTwAFfaJ8occyV_3Fqs_0P-mkiXlo7S0ll6MLC2mVO_LBxh5hw2uR5XHgAlcBJUCy_bugUCDxk0vPe8VzTUOt0si4eCoG_9qGxrk.

- R. Z.-T. N. Atlantis and undefined 2007, “The hydrogen hoax,” JSTOR, Accessed: Mar. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43152303?casa_token=cR8dWvg1DikAAAAA:cVZaZ1odOw7VAlnFmG89uCFiXnnH84umoewH-4Dgxy6Jy6BpbOqXeaqnkX7Uh2ktoY1a32aDCNDvIVIl408idd6AKJ-jXrRq5LOYUgJAkuJsIIqL3Vht.

- H. Nykyforchyn, O. Tsyrulnyk, O. Zvirko, and M. Hredil, “Role of hydrogen in operational degradation of pipeline steel,” Procedia Struct. Integr., vol. 28, pp. 896–902, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Tiwari et al., “A study of internal hydrogen embrittlement of steels,” Mater. Sci. Eng. A, vol. 286, no. 2, pp. 269–281, Jul. 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. Dwivedi, M. V.-I. J. of H. Energy, and undefined 2018, “Hydrogen embrittlement in different materials: A review,” Elsevier, vol. 43, no. 46, pp. 21603–21616, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Student, “Accelerated method for hydrogen degradation of structural steel,” Mater. Sci. 1999 344, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 497–507, 1998. [CrossRef]

- V. I. Shapovalov, “Influence of Hydrogen on the Structure and Properties of Iron-Carbon Alloys.” Metallurgiya, 1982.

- V. I. Pokhmurskyi and V. V. Fedorov, “Influence of Hydrogen on the Diffusion Processes in Metals.” Karpenko Physicomechanical Institute, Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, 1998.

- E. I. Krutasova, “Reliability of the Metal of Power-Generating Equipment.” Énergoizdat, 1981.

- B. M. A. A. V. V. M. A. K. H. M. Nykyforchyn, “Evaluation of the effect of closure of fatigue cracks,” Fiz.-Khim. Mekh. Mater., vol. 18, no. No. 5, pp. 100–103, 1982.

- D. Hirakami et al., “Effect of Aging Treatment on Hydrogen Embrittlement of Drawn Pearlitic Steel Wire,” ISIJ Int., vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 893–898, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, J. Yamabe, H. Matsunaga, and S. Matsuoka, “Material performance of age-hardened beryllium–copper alloy, CDA-C17200, in a high-pressure, gaseous hydrogen environment,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 42, no. 26, pp. 16887–16900, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Yamabe, D. Takagoshi, H. Matsunaga, S. Matsuoka, T. Ishikawa, and T. Ichigi, “High-strength copper-based alloy with excellent resistance to hydrogen embrittlement,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 41, no. 33, pp. 15089–15094, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Ogawa, T. Oda, K. Maruoka, and J. Sakai, “Effect of aging at room temperature on hydrogen embrittlement behavior of Ni-Ti superelastic alloy immersed in acidic fluoride solution,” Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Li, D. Zhu, W. Jia, and F. Zhang, “Analysis of the aging mechanism and life evaluation of elastomers in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments,” E-Polymers, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 921–929, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Yokoyama, T. Ogawa, K. Takashima, K. Asaoka, and J. Sakai, “Hydrogen embrittlement of Ni-Ti superelastic alloy aged at room temperature after hydrogen charging,” Mater. Sci. Eng. A, vol. 466, no. 1–2, pp. 106–113, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. Ogawa, T. Oda, K. Maruoka, and J. Sakai, “Effect of aging at room temperature on hydrogen embrittlement behavior of Ni-Ti superelastic alloy immersed in acidic fluoride solution,” Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng., vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Tal-Gutelmacher, D. E.-J. of alloys and compounds, and undefined 2005, “Hydrogen cracking in titanium-based alloys,” Elsevier, vol. 404, pp. 621–625, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Omura et al., “Effect of Surface Hydrogen Concentration on Hydrogen Embrittlement Properties of Stainless Steels and Ni Based Alloys,” ISIJ Int., vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 405–412, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Klopffer, P. Berne, S. Castagnet, and M. Weber, “pipes for distributing mixtures of hydrogen and natural gas. Evolution of their transport and mechanical properties after an ageing under an hydrogen environment,” 2010, Accessed: Nov. 09, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/21400887.

- M. Zhang, H. Lv, H. Kang, W. Zhou, C. Z.-I. J. of, and undefined 2019, “A literature review of failure prediction and analysis methods for composite high-pressure hydrogen storage tanks,” Elsevier, Accessed: Dec. 25, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360319919329106.

- J. Yamabe, H. Fujiwara, and S. Nishimura, “Fracture analysis of rubber sealing meterial for high pressure hydrogen vessel,” Nihon Kikai Gakkai Ronbunshu, A Hen/Transactions Japan Soc. Mech. Eng. Part A, vol. 75, no. 756, pp. 1063–1073, 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. X. Zheng, L. Wang, R. Li, Z. X. Wei, and W. W. Zhou, “Fatigue test of carbon epoxy composite high pressure hydrogen storage vessel under hydrogen environment,” J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 393–400, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Feng, Y. Shi, W. Zhang, and K. Volodymyr, “Hydrogen Embrittlement Failure Behavior of Fatigue-Damaged Welded TC4 Alloy Joints,” Crystals, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 512, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Brownell, A. L. Frischknecht, and M. A. Wilson, “Subdiffusive High-Pressure Hydrogen Gas Dynamics in Elastomers,” Macromolecules, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Wilson and A. L. Frischknecht, “High-pressure hydrogen decompression in sulfur crosslinked elastomers,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 47, no. 33, pp. 15094–15106, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhou, G. Chen, P. Liu, C. Z. Guohua, and C. P. Liu, “Finite element analysis of sealing performance of rubber D-ring seal in high-pressure hydrogen storage vessel,” Springer, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 846–855, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Zatoń, J. Rozière, and D. J. Jones, “Current understanding of chemical degradation mechanisms of perfluorosulfonic acid membranes and their mitigation strategies: A review,” Sustain. Energy Fuels, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 409–438, 2017. [CrossRef]

- LaConti, M. Hamdan, R. M.-H. of fuel cells, and undefined 2003, “Mechanisms of membrane degradation,” researchgate.net. [CrossRef]

- M. Danilczuk, F. D. Corns, and S. Schlick, “Visualizing chemical reactions and crossover processes in a fuel cell inserted in the esr resonator: Detection by spin trapping of oxygen radicals, nafion-derived fragments, and hydrogen and deuterium atoms,” J. Phys. Chem. B, vol. 113, no. 23, pp. 8031–8042, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S.-Y. Lee et al., “Effects of Purging on the Degradation of PEMFCs Operating with Repetitive On/Off Cycles,” J. Electrochem. Soc., vol. 154, no. 2, p. B194, 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Healy et al., “Aspects of the chemical degradation of PFSA ionomers used in PEM fuel cellsx,” Fuel Cells, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 302–308, Apr. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Kusoglu and A. Z. Weber, “A Mechanistic Model for Pinhole Growth in Fuel-Cell Membranes during Cyclic Loads,” J. Electrochem. Soc., vol. 161, no. 8, pp. E3311–E3322, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Gittleman, F. D. Coms, and Y.-H. Lai, “Chapter 2 - Membrane Durability: Physical and Chemical Degradation A2 - Mench, Matthew M.,” Mod. Top. Polym. Electrolyte Fuel Cell Degrad., pp. 15–88, 2012, Accessed: Jul. 19, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123869364100028.

- G. De Moor et al., “Understanding membrane failure in PEMFC: Comparison of diagnostic tools at different observation scales,” Fuel Cells, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 356–364, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Z. Harris, J. B.-M. S. and E. A, and undefined 2019, “The effect of isothermal heat treatment on hydrogen environment-assisted cracking susceptibility in Monel K-500,” Elsevier, Accessed: Nov. 11, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921509319310354.

- H. Nykyforchyn, E. Lunarska, O. T. Tsyrulnyk, K. Nikiforov, M. E. Genarro, and G. Gabetta, “Environmentally assisted ‘in-bulk’ steel degradation of long term service gas trunkline,” Eng. Fail. Anal., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 624–632, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Robert et al., “The Impact of Chemical-Mechanical Ex Situ Aging on PFSA Membranes for Fuel Cells,” Membr. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 366, vol. 11, no. 5, p. 366, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Balitskii, … L. I.-… on C. R. of the 12th, and undefined 2009, “Temperature dependences of age-hardening austenitic steels mechanical properties in gaseous hydrogen,” researchgate.net, 2009, Accessed: Nov. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alexander-Balitskii/publication/281269596_Temperature_Dependences_of_Age-hardening_Austenitic_Steels_Mechanical_Properties_in_Gaseous_Hydrogen/links/55dd955908aeb41644aefe8e/Temperature-Dependences-of-Age-hardening-Austenitic-Steels-Mechanical-Properties-in-Gaseous-Hydrogen.pdf.

- T. Cui, C. W. Lin, C. H. Chien, Y. J. Chao, and J. W. Van Zee, “Service life estimation of liquid silicone rubber seals in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell environment,” J. Power Sources, vol. 196, no. 3, pp. 1216–1221, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Brown, “Survey of status of test methods for accelerated durability testing,” Polym. Test., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 3–30, 1991. [CrossRef]

- R. Burgess, M. Post, W. Buttner, and C. Rivkin, “High Pressure Hydrogen Pressure Relief Devices: Accelerated Life Testing and Application Best Practices,” 2017, Accessed: Dec. 24, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1408284.

- D. Liu, S. C.-J. of P. Sources, and undefined 2006, “Durability study of proton exchange membrane fuel cells under dynamic testing conditions with cyclic current profile,” Elsevier, Accessed: Dec. 24, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378775306012493.

- S. Kundu, L. Simon, M. F.-P. D. and Stability, and undefined 2008, “Comparison of two accelerated NafionTM degradation experiments,” Elsevier, vol. 93, no. 1, pp. 214–224, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. E. Irving, “Development of service life prognosis systems for hydrogen energy devices,” Gaseous Hydrog. Embrittlement Mater. Energy Technol. Mech. Model. Futur. Dev., pp. 430–468, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Hiemenz and T. P. Lodge, “Polymer Chemistry,” Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Andrews and A. V. Tobolsky, “Elastoviscous properties of polyisobutylene. IV. Relaxation time spectrum and calculation of bulk viscosity,” J. Polym. Sci., vol. 7, no. 23, pp. 221–242, Aug. 1951. [CrossRef]

- L. C. E. Struik, “Physical aging in plastics and other glassy materials,” Polym. Eng. Sci., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 165–173, 1977. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Williams, R. F. Landel, and J. D. Ferry, “The Temperature Dependence of Relaxation Mechanisms in Amorphous Polymers and Other Glass-forming Liquids,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 77, no. 14, pp. 3701–3707, 1955. [CrossRef]

- K. Fukushima, H. Cai, M. Nakada, Y. M.-P. ICCM, and undefined 2009, “Determination of time-temperature shift factor for long-term life prediction of polymer composites,” iccm-central.org, Accessed: Apr. 03, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://iccm-central.org/Proceedings/ICCM17proceedings/Themes/Behaviour/AGING, MOIST & VISCOE PROP/INT - AGING, MOIST & VISCOE PROP/IF1.1 Fukushima.pdf.

- G. Li, J. Tan, and J. Gong, “Chemical aging of the silicone rubber in a simulated and three accelerated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environments,” J. Power Sources, vol. 217, pp. 175–183, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Tan, Y. J. Chao, M. Yang, W. K. Lee, and J. W. Van Zee, “Chemical and mechanical stability of a Silicone gasket material exposed to PEM fuel cell environment,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 1846–1852, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Cui, C. W. Lin, C. H. Chien, Y. J. Chao, and J. Van Zee, “Service life prediction of seal in PEM fuel cells,” Conf. Proc. Soc. Exp. Mech. Ser., vol. 5, pp. 25–32, 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Gittleman, Y. Lai, D. M.-P. of the Aic. 2005, and undefined 2005, “Durability of perfluorosulfonic acid membranes for PEM fuel cells,” researchgate.net, Accessed: Aug. 11, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Craig-Gittleman-2/publication/265075095_Durability_of_Perfluorosulfonic_Acid_Membranes_for_PEM_Fuel_Cells/links/547321ef0cf2d67fc035dff1/Durability-of-Perfluorosulfonic-Acid-Membranes-for-PEM-Fuel-Cells.pdf.

- V. Zelě Nák, I. Saldan, D. Giannakoudakis, M. Barczak, and J. Pasán, “Factors affecting hydrogen adsorption in metal–organic frameworks: A short review,” mdpi.com, vol. 11, no. 7, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Eliezer and T. H. Böllinghaus, “Hydrogen effects in titanium alloys,” Gaseous Hydrog. Embrittlement Mater. Energy Technol. Probl. its Characterisation Eff. Part. Alloy Classes, pp. 668–706, 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. Tomi, “EFFECTS OF HYDROGEN UPON THE PROPERTIES OF THERMO MECHANICAL CONTROLLED PROCESS ( TMCP ) STEEL,” 2015.

- S. Fukuyama, K. Yokogawa, and D. Sun, “Hydrogen environment embrittlement of type 316 series austenitic stainless steels at low temperatures: Study on low temperature used in WE-NET 18,” 2002, Accessed: Dec. 15, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/20317953.

- Y. Wu, D. Wang, W. Zhang, and J. Zhang, “Experimental research of thermal-oxidative aging on the mechanics of aero-nbr,” J. Test. Eval., vol. 42, no. 3, 2013. [CrossRef]