Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

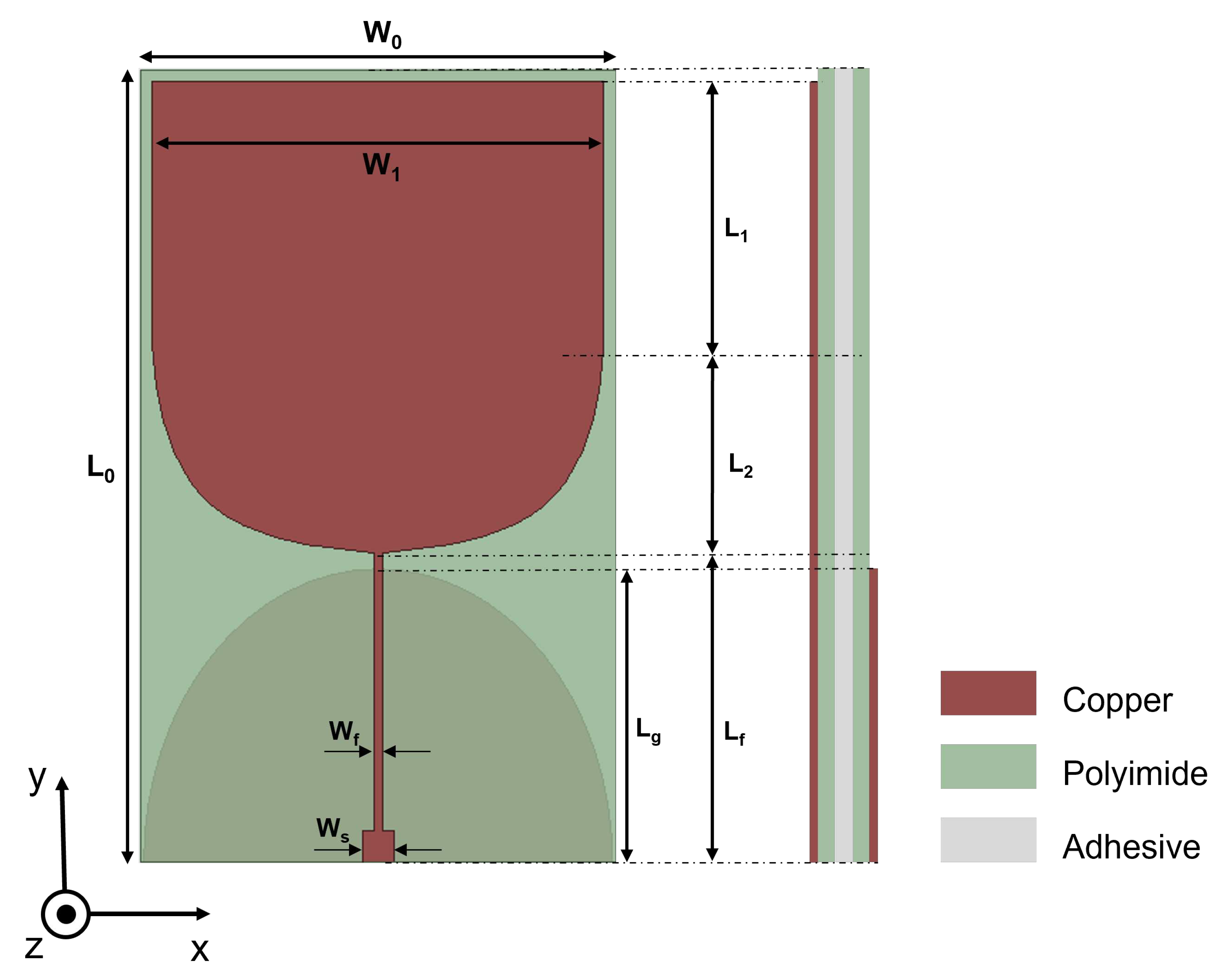

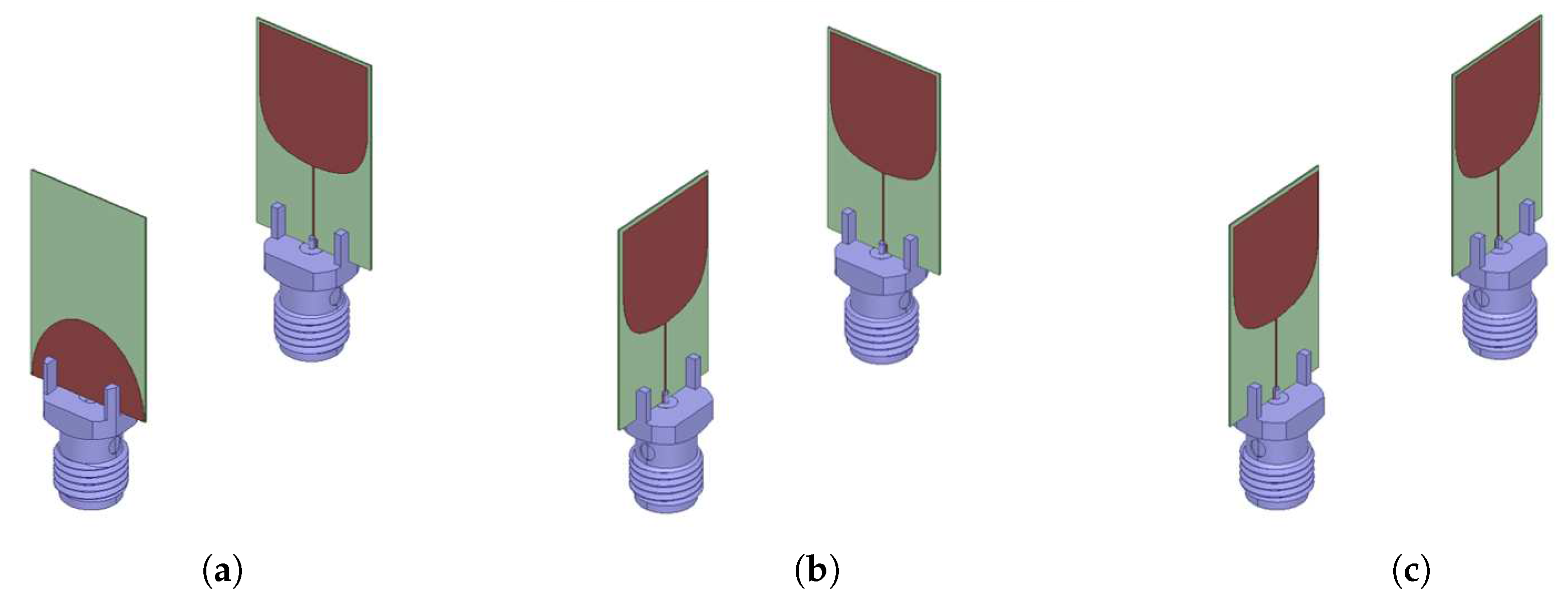

2. Design of thin film UWB monopole antenna

2.1. Thin film layer stack up

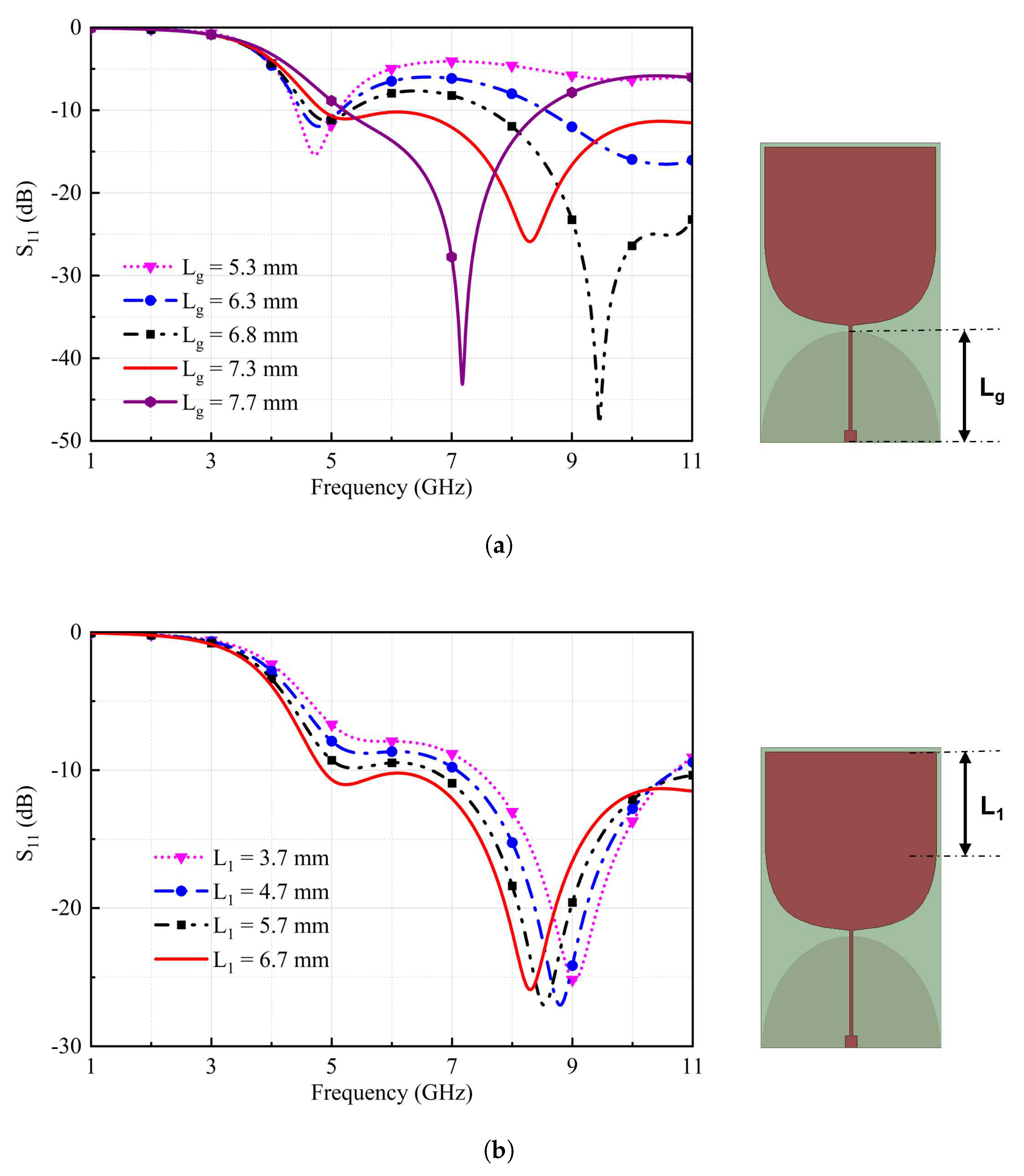

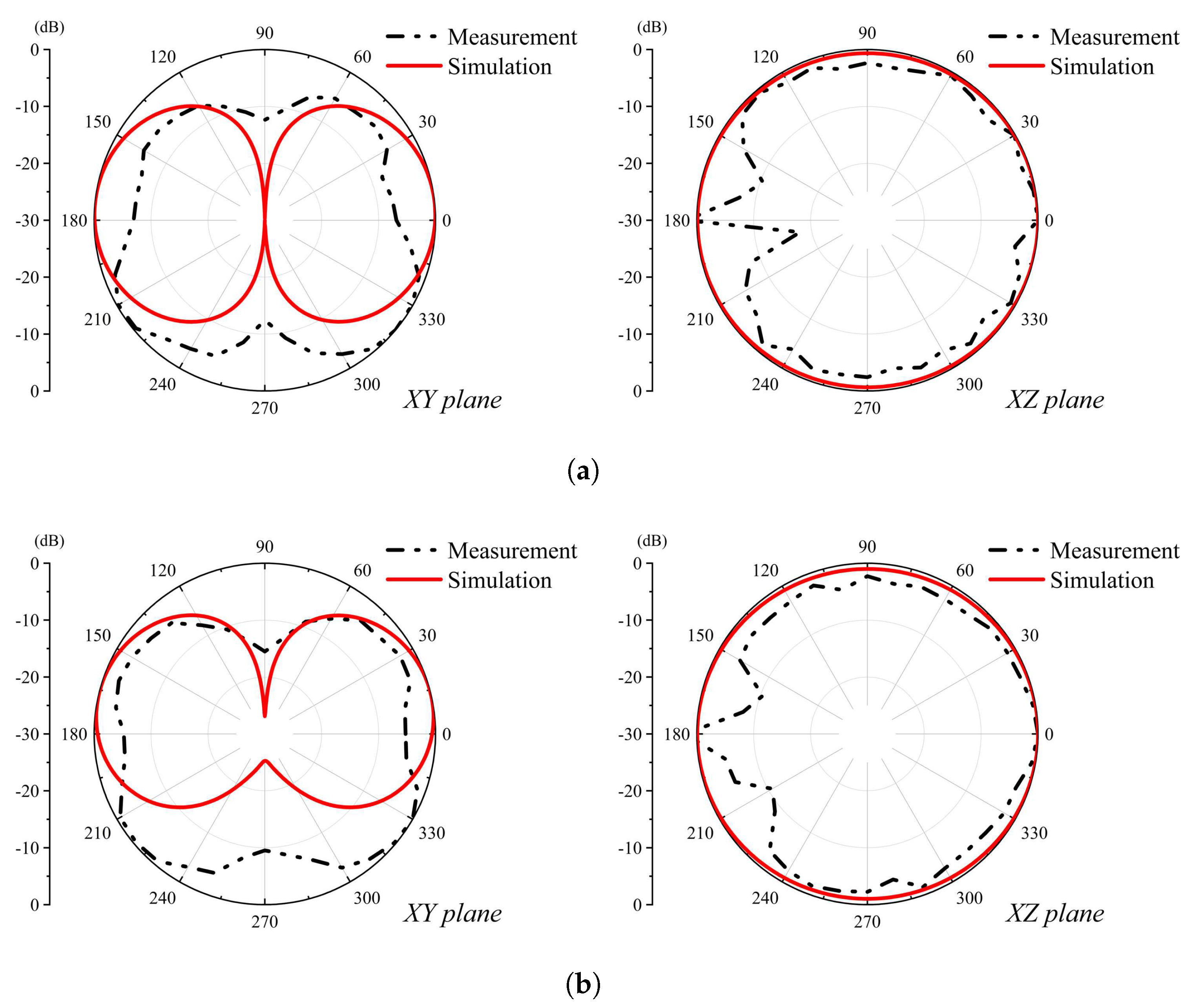

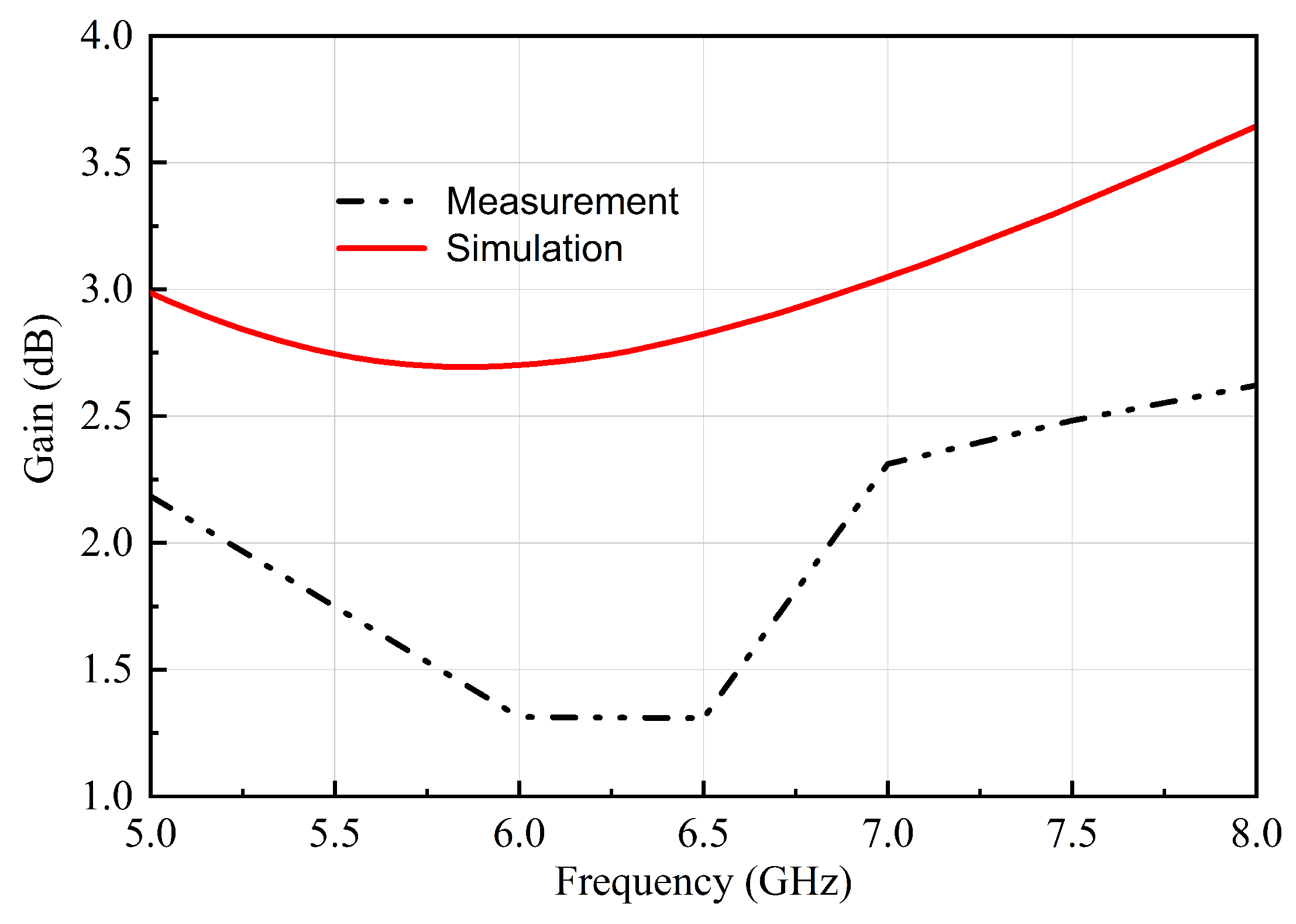

2.2. Simulation results

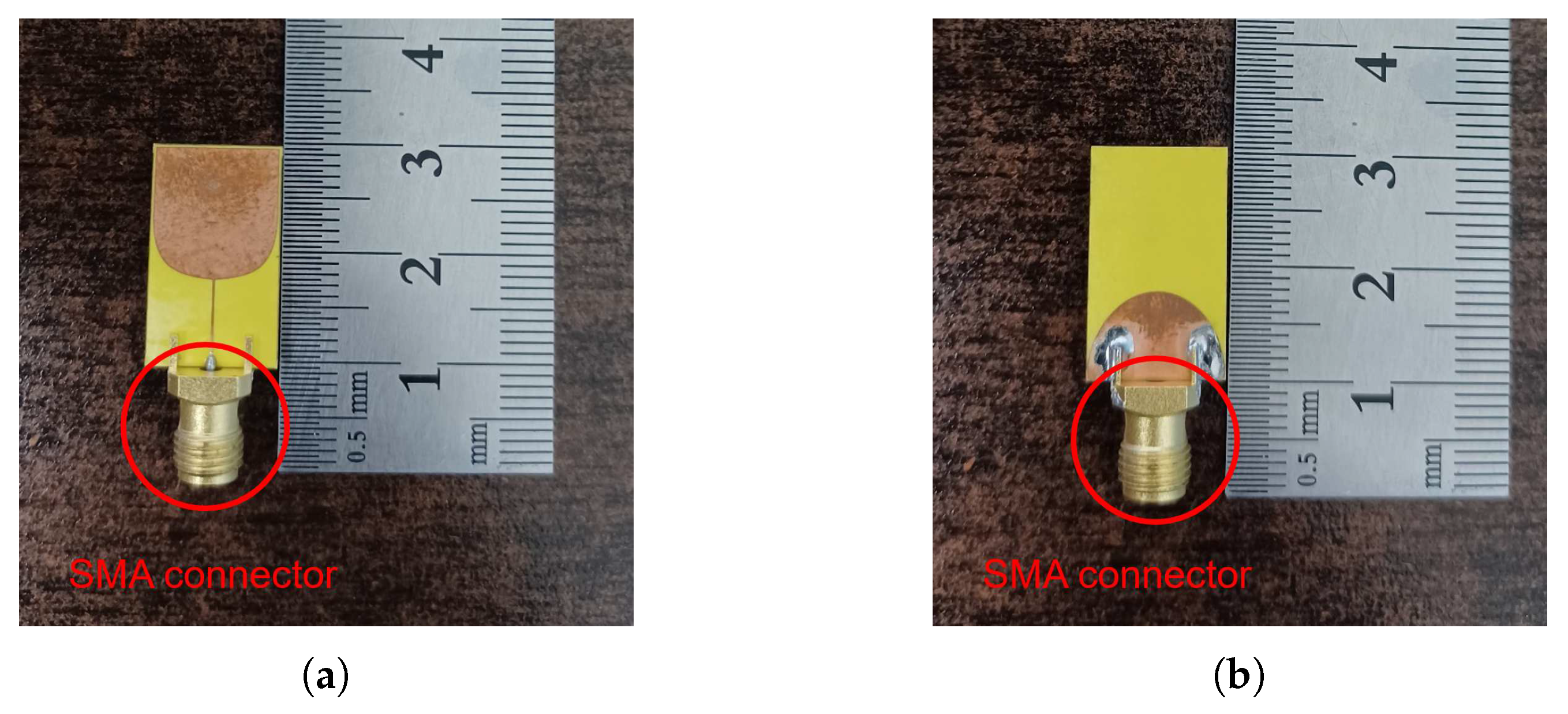

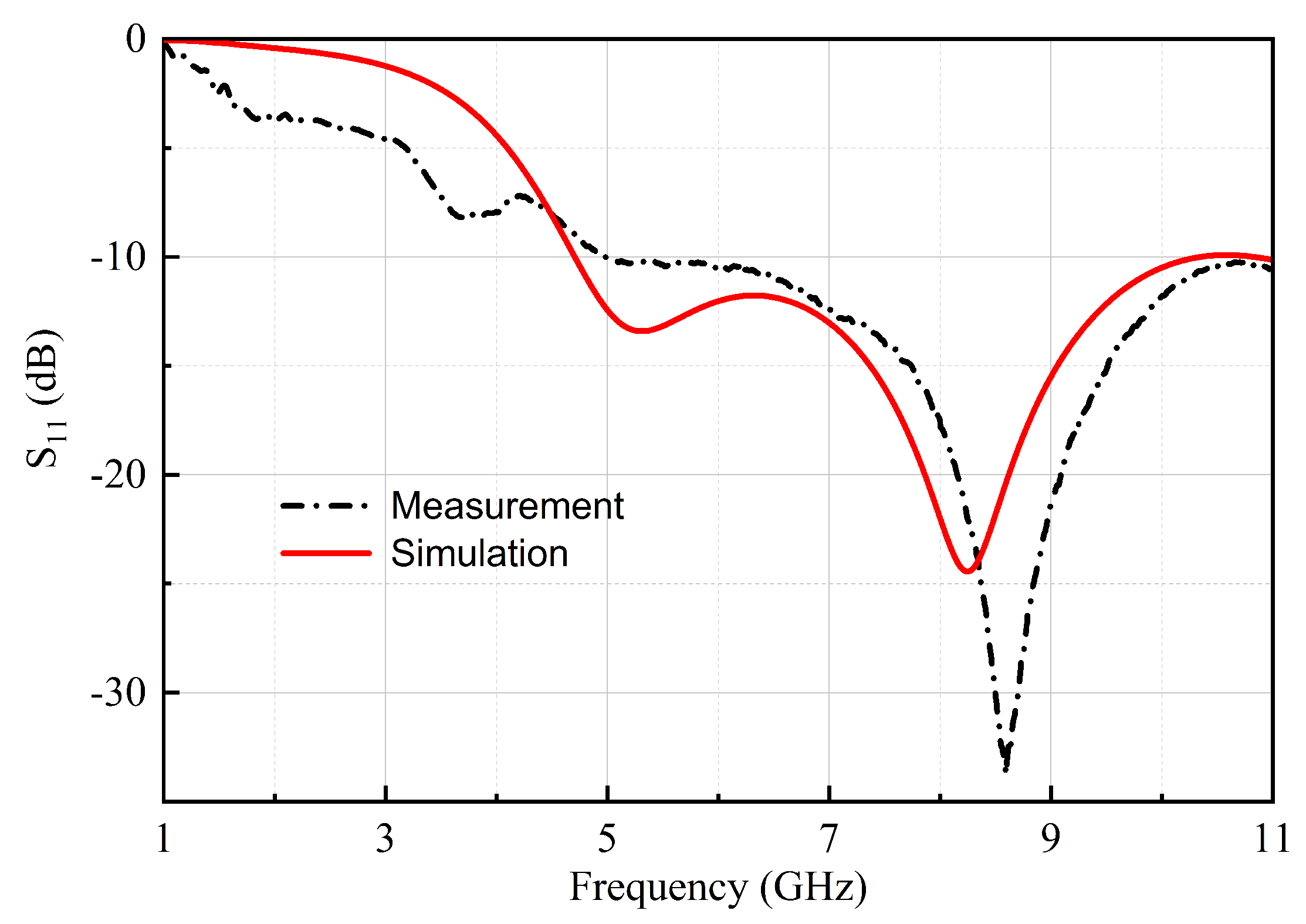

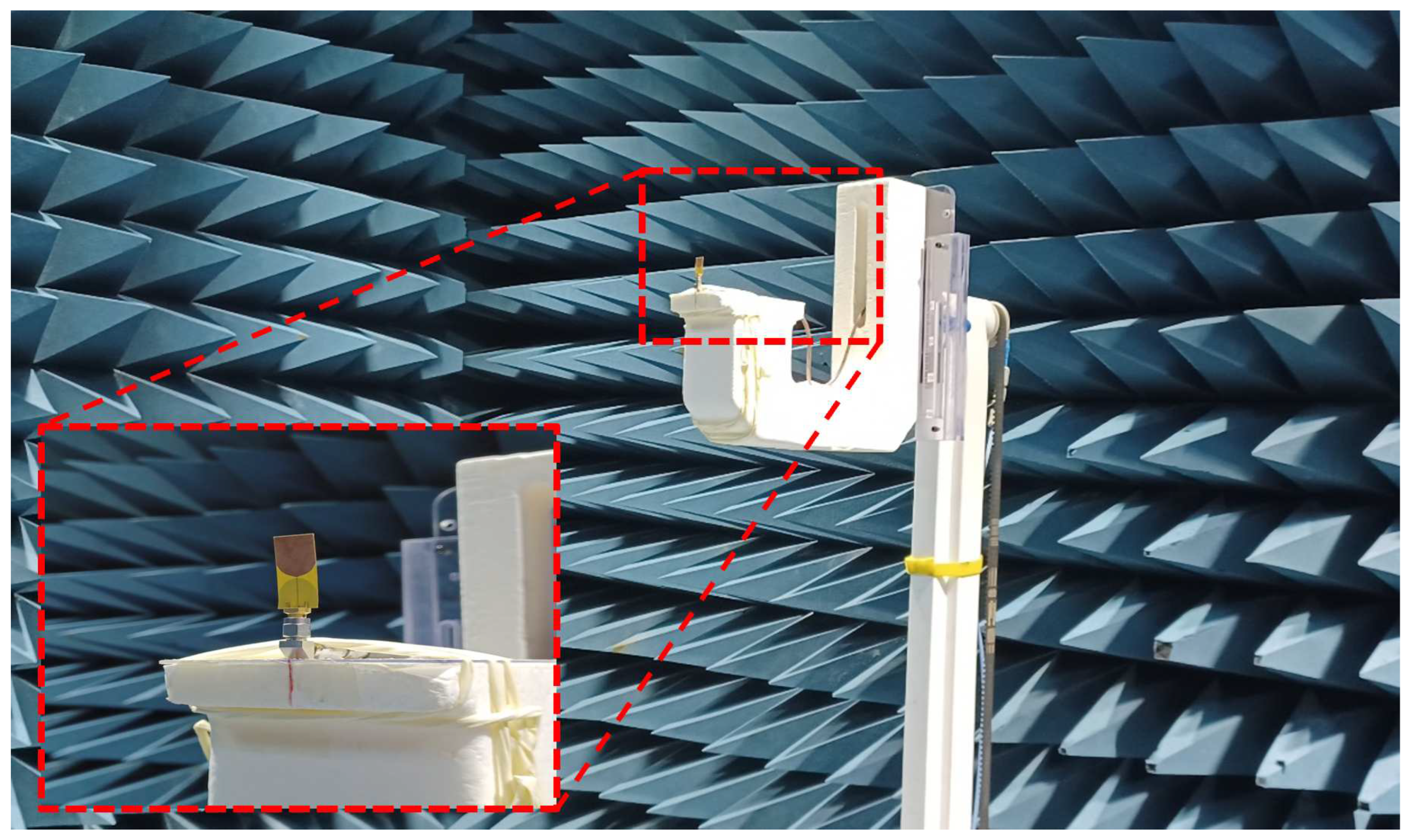

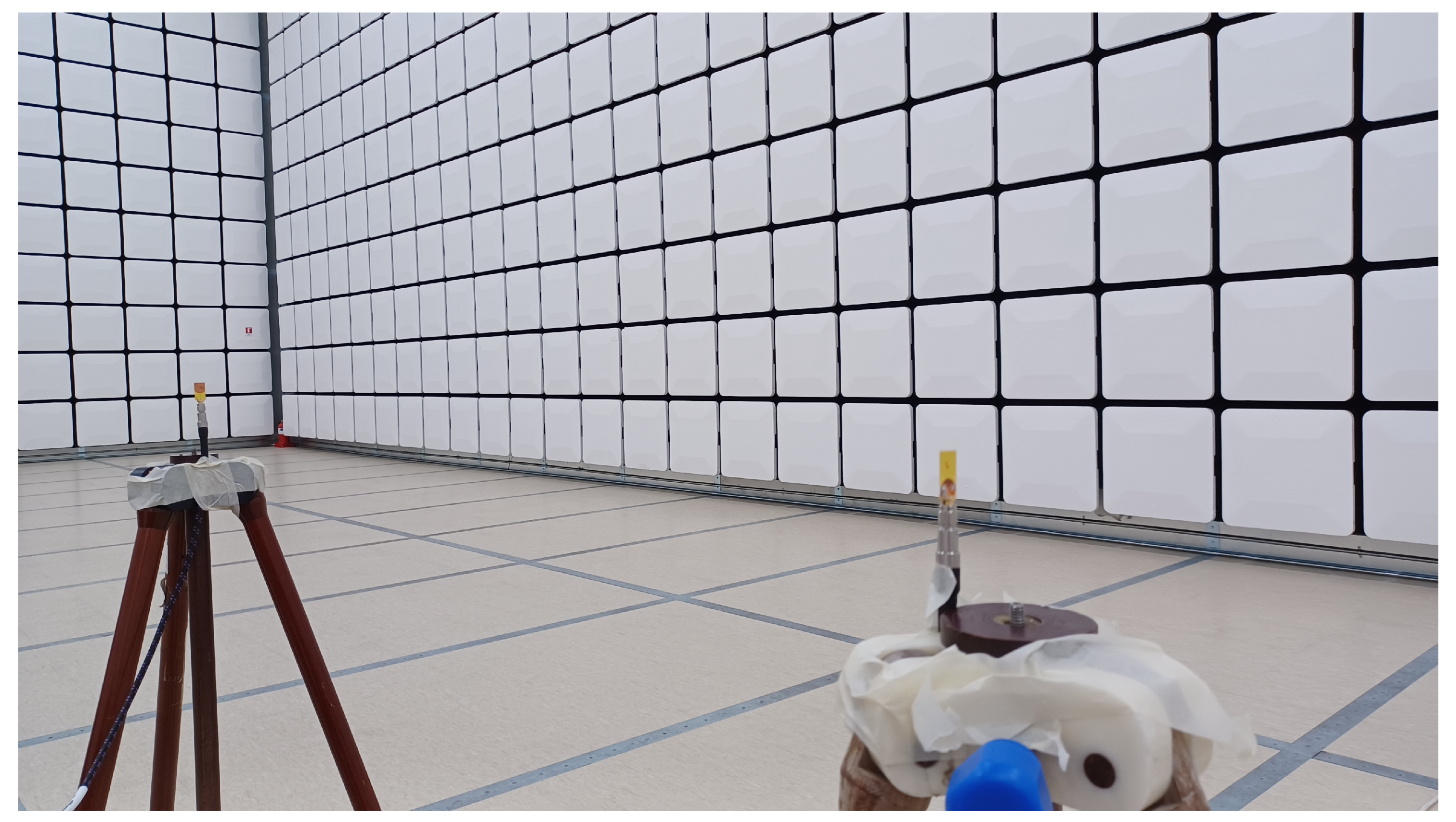

3. Antenna fabrication and measurements

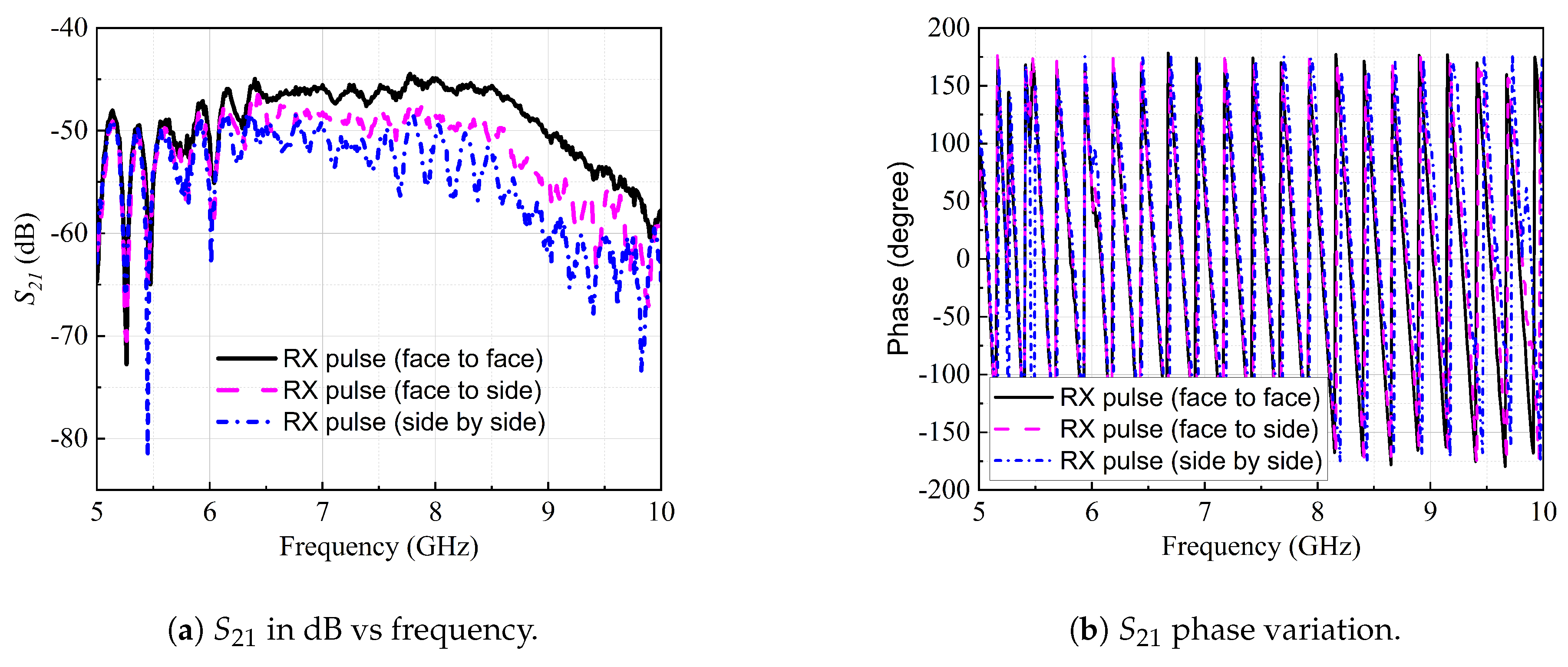

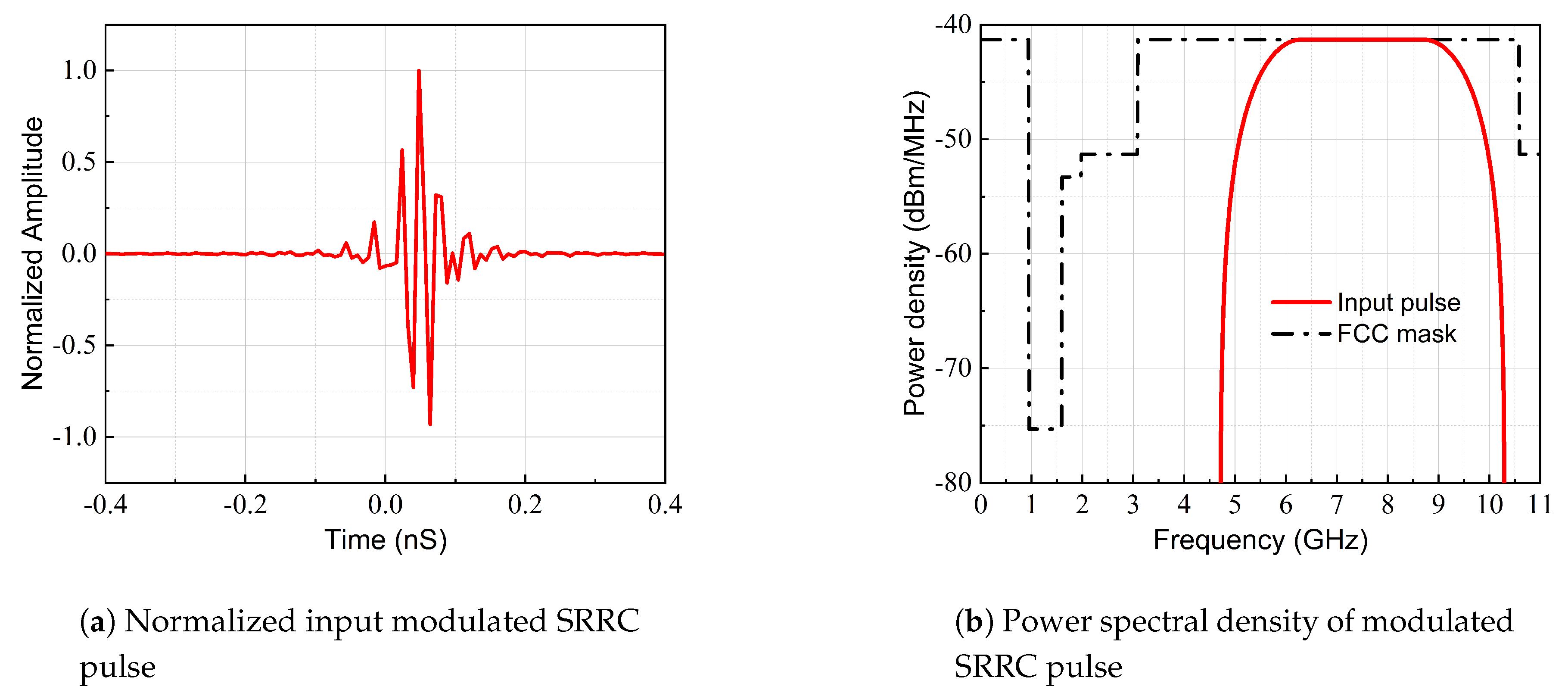

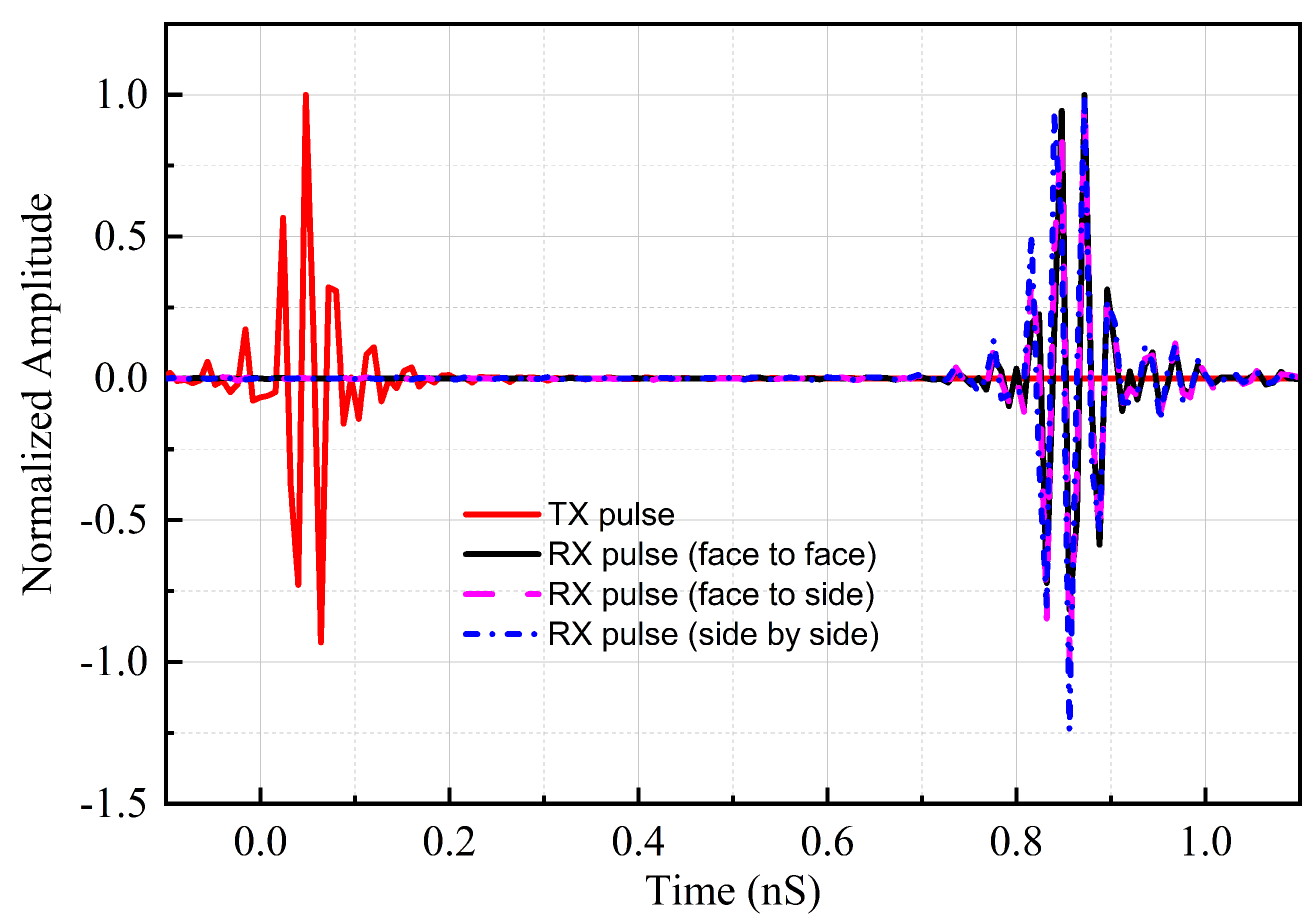

4. Time domain analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elsanhoury, M.; Mäkelä, P.; Koljonen, J.; Välisuo, P.; Shamsuzzoha, A.; Mantere, T.; Elmusrati, M.; Kuusniemi, H. Precision Positioning for Smart Logistics Using Ultra-Wideband Technology-Based Indoor Navigation: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 44413–44445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems and Technologies. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon Gwang-Hun, Dzagbletey Philip Ayiku, C. J.Y. A Cross-Joint Vivaldi Antenna Pair for Dual-Pol and Broadband Testing Capabilities. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci 2021, 21, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekki Kawther, Necibi Omrane, L. S.G.A. A UHF/UWB Monopole Antenna Design Process Integrated in an RFID Reader Board. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci 2022, 22, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala Susmita, Reddy P. Soni, M.R.S.P.P.S.S. Printed Monopole Antenna with Tree-Like Radiating Patch and Flower Vase-Shaped Modified Ground Plane Useful for Wideband Applications. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci 2022, 22, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, R. Khaleel and Hussain M. Al-Rizzo and Daniel G. Rucker. Compact polyimide-based antennas for flexible displays. J. Display Technol. 2012, 8, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, S.; Ponchak, G.; Papapolymerou, J.; Tentzeris, M. Conformal double exponentially tapered slot antenna (DETSA) on LCP for UWB applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2006, 54, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HR, K.; HM, A.R.; Rucker DG, M.S. A compact polyimide-based UWB antenna for flexible electronics. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett. 2012, 11, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H.; Mirbozorgi, S.A.; Ameli, R.; Rusch, L.A.; Gosselin, B. Flexible, polarizationdiverse UWB antennas for implantable neural recording systems. IEEE Trans. on Biom. Ckts and Sys. 2016, 10, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F, W.; Arslan, T. A wearable ultra-wideband monopole antenna with flexible artificial magnetic conductor. 2016 Loughborough Antennas & Propagation Conference (LAPC).

- S. , H.; Kang, S.H.; Jung, C.W. Transparent and flexible antenna for wearable glasses applications. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2016, 64, 2797–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P., P.H.; Vuong, T.P.; P. Benech, P.X.; Borel, P.; Delattre, A. P., P.H.; Vuong, T.P.; P. Benech, P.X.; Borel, P.; Delattre, A. Printed flexible wideband microstrip antenna for wireless applications. International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Communications (ATC).

- LJ, X.; H, W.; Y, C.; Y, B. A flexible UWB inverted-F antenna for wearable application. Microw Opt Technol Lett. 2017, 59, 2514–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.M.; Lim, J.H.; Lee, C.M.; Park, E.C.; CHoi, J.H.; Joo, J.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, S.B. Fabrication of two-layer flexible copper clad laminate by electroless-Cu plating on surface modified polyimide. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2009, 19, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. , P.H.; Vuong, T.P.; Benech, P.; Xavier, P.; Borel, P.; Delattre, A. On the dispersive properties of the conical spiral antenna and its use for pulsed radiation. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2003, 51, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, V.; Haapola, J.; Hämäläinen, M.; Iinatti, J. An Ultra Wideband Survey: Global Regulations and Impulse Radio Research Based on Standards. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2017, 19, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.; Dohler, M.; Okon, E.; Malik, W.; Brown, A.; Edwards, D. Ultra-wideband : antennas and propagation for communications, radar and imaging; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007.

- Matin, M. Ultra Wideband Communications; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- G. M., G.T.; M.A., P.S., H, J.A. Ultra Wideband Antennas: Design, Methodologies, Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorfar, A.; Perrotta, A. An experimental study of microstrip antennas on very high permittivity ceramic substrates and very small ground planes. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2001, 49, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Luk, K.M. Low-Profile Planar Dielectric Polarizer Using High-Dielectric-Constant Material and Anisotropic Antireflection Layers. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2021, 69, 8494–8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Harackiewicz, F. Miniature microstrip antenna with a partially filled high-permittivity substrate. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2002, 50, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Zwierzchowski, S.; Jazayeri, P. Derivation and determination of the antenna transfer function for use in ultra-wideband communications analysis. Wireless Proc.

- Mohammadian, A.; Rajkotia, A.; Soliman, S. Characterization of UWB transmit-receive antenna system. IEEE Conference on Ultra Wideband Systems and Technologies, 2003, pp. 157–161.

- Chen, Z.N.; Wu, X.H.; Li, H.F.; Yang, N.; Chia, M. Considerations for source pulses and antennas in UWB radio systems. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2004, 52, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Larson, L.E.; Asbeck, P.M. Design of Linear RF Outphasing Power Amplifiers; Norwood, MA: Artech House: London, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lamensdorf, D.; Susman, L. Baseband-pulse-antenna techniques. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine 1994, 36, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, G.; Zurcher, J.F.; Skrivervik, A.K. System Fidelity Factor: A New Method for Comparing UWB Antennas. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2011, 59, 2502–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, D.H. Effect of antenna gain and group delay variations on pulse-preserving capabilities of ultrawideband antennas. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2006, 54, 2208–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.K.; Goodbody, C.; Karacolak, T.; Sekhar, P.K. A compact monopole antenna for ultra-wideband applications. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 2019, 61, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahat, N.; Zhadobov, M.; Sauleau, R.; Ito, K. A Compact UWB Antenna for On-Body Applications. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2011, 59, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.A.; Madhav, B.; Vineel, B.; Chandini, G.; Amrutha, C.; Rao, M. Design and Analysis of a Circularly polarized flexible, compact and transparent antenna for Vehicular Communication Applications. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1804, 012192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.R.; Karacolak, T. CPW-Fed Compact Circularly Polarized Flexible Antenna for C Band Applications. 2023 United States National Committee of URSI National Radio Science Meeting (USNC-URSI NRSM), 2023, pp. 246–247.

- Venkateswara Rao, M.; Madhav, B.T.P.; Anilkumar, T.; Prudhvinadh, B. Circularly polarized flexible antenna on liquid crystal polymer substrate material with metamaterial loading. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 2020, 62, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser-Moghadasi, M.; Sadeghzadeh, R.A.; Sedghi, T.; Aribi, T.; Virdee, B.S. UWB CPW-Fed Fractal Patch Antenna With Band-Notched Function Employing Folded T-Shaped Element. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 2013, 12, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtania, S.G.; Younes, B.A.; Hossain, A.R.; Karacolak, T.; Sekhar, P.K. CPW-Fed Flexible Ultra-Wideband Antenna for IoT Applications. Micromachines 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Song, R.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Qian, W.; He, D. Compact and Low-Profile UWB Antenna Based on Graphene-Assembled Films for Wearable Applications. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Value | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12.0 mm | 7.8 mm | ||

| 20.0 mm | 0.2 mm | ||

| 11.4 mm | 7.4 mm | ||

| 6.7 mm | 0.8 mm | ||

| 5.2 mm | 1.25 |

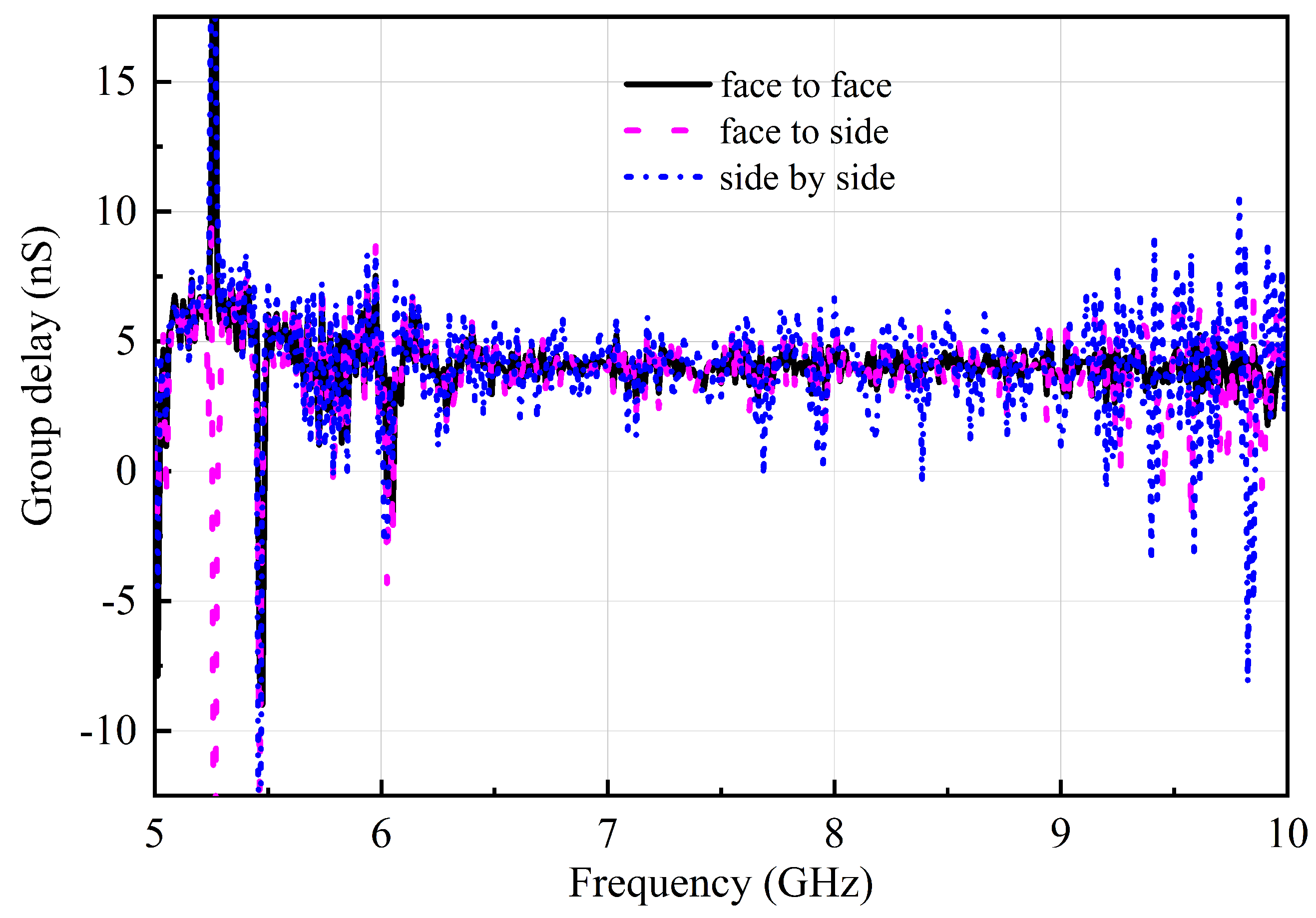

| Face to face | Face to side | Side by side | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fidelity factor | 0.904 | 0.919 | 0.853 |

| Ref | Absolute size () | Electrical size () | Operating frequency (GHz) | Max gain (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | 5 - 14 | N/A | ||

| [31] | 3 - 11.2 | 1.5 | ||

| [32] | 5.2 - 6.86 | 2.94 | ||

| [33] | 3.8 – 4.5 | 3.1 | ||

| [34] | 5.5 – 7 | N/A | ||

| [35] | 2.94 - 11.17 | 3.6 | ||

| [36] | 3.04 - 10.7 | N/A | ||

| [37] | 4 - 8 | 4.1 | ||

| This work | 20 × 12 × 0.174 | 0.33 × 0.2 × 0.0025 | 5 - 10.8 | 2.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).