1. Introduction

Currently, the replacement of synthetic food additives with their natural equivalents will greatly help to satisfy the demands of the food industry due to the trend of healthy human nutrition and rising customer desire for natural foodstuffs.

Foods are a rich source of phenolic acids. Caffeic acid and, to a lesser extent, ferulic acid are the most well-known [

1].

Flavonoids are the most populous polyphenols in human diet. Their appearance is limited to a few foods. The primary source of isoflavones is soy bean, which has a genistein and daidzein content ~ 1 mg g/g [

2]. Due to their estrogenic characteristics and potential roles in the prevention of breast cancer and osteoporosis, these two isoflavones have drawn a lot of interest [

3]. The primary dietary source for flavanones is citrus fruits. Hesperidin from oranges (125–250 mg/L juice) is the most consumed [

4].

The antioxidant activity of

Rosa damascena extracts and products is mostly reasoned by this high content of phenolic compounds. Among several analyzed rose teas, those prepared from cvs San Francisco (of the hybrid tea roses group), Katharina Zeimet (polyantha group), Mercedes (floribunda group), and from the essential oil rose

R. damascena exhibited the highest antioxidant activities, which was even higher than that of green tea [

5].

Membrane operations, such as microfiltration (MF) and ultrafiltration (UF), are competitive and attractive alternatives to the conventional processes used in fruit processing. The advantages of using membrane technology in the beverage industry are related to economy, working conditions, environment and product quality [

6]. Typical advantages of membrane technology over conventional fining agents are: low energy requirements and costs; possibility to avoid the use of gelatins, adsorbents and other filtration aids; possibility of lower temperature processing (hence reduction of thermal damage to food during processing); simpler process design; reduction of waste products; possibility of avoiding use of chemical agents; increased juice yield (juice recovery of 96–98% can be obtained in contrast to conventional processes); reduction in enzyme utilization (depending on the juice enzyme usage is reduced from 50% to 75%); better maintenance and cleaning of the equipment; improved product quality; possibility of operating in a single step decreasing working times (traditional methods requiring fining agents may take 12–36 h); possibility of avoiding pasteurization (at 60–65°C) and sterilization (at about 110°C). All these features are becoming very important factors in the production of new additive free fruit juices with natural fresh taste [

7].

Distilled (de-aromatized) rose (

Rosa damascena Mill.) petals, a by-product from the essential oil industry, are rich source of polyphenols, particularly flavonols [

8]. Their efficiency as natural co-pigments is shown both in model and real food matrix systems of strawberry anthocyanins. The plant waste utilization strategy is based on the well-established tradition in using rose petals for preparing foods such as jams and beverages on one side and processing methods widely used in modern fruit juice technology on the other side. In this context, analogous to coloring foodstuffs, the rose petal polyphenols might be declared as “color-enhancing plant extract”, allowing avoidance of E-number labelling and thus supporting consumer confidence in natural foodstuffs.

The aim of the present study was to study effects of membrane molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) and process parameters on the flux and phytochemical characteristics during ultrafiltration for concentration of polyphenols in rose petal extract.

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Chemicals

The reagents for analysis were: TPTZ [2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine] and gallic acid monohydrate (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland); Folin-Ciocalteau’s reagent (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany); DPPH [2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl] and Trolox [(+/−)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-chroman-2-carboxylic acid] (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). The remaining chemicals were all of analytical grade.

2.1.2. Enzyme preparations

Commercial enzyme preparations of the following types were used: ); hemicellulolytic Xylanase AN (Biovet JSC, Peshtera, Bulgaria); cellulolytic Rohament CL (AB Enzymes GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany; pectinolytic Pectinex Ultra Color (Novozymes A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark).

2.1.3. Plant materials

Plant by-product, a residue from water-steam distillation of oil-bearing rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) petals, was supplied by Ecomaat Ltd. (Mirkovo, Bulgaria) during 2017 processing campaign. After pressing of the wet material in a rack and cloth press, the pomace obtained was stored frozen until used. After defrosting, the pomace was hot air-dried (60°C, 8 h).

2.2. Enzyme-assisted extraction of rose petal by-product

Dry pomace that had been finely ground (particle size < 0.63 mm) was mixed with water (12:1, v/w), acidified (pH 4.0) with 50% (w/v) citric acid, and then kept overnight at 10°C for rehydration. The suspension was adjusted to pH 4.0, heated in a water bath at 50°C for 20 min, and then 10 mL of an acidified water solution (1.2%, v/v) of the enzyme mixture (1:1:1) were added. The sample was pressed using a rack and cloth press (25 MPa) after 2.5 hours of incubation at 50°C. The extract was filtered through a paper filter after being pasteurized at 80°C for 4 minutes.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Ultrafiltration of rose petal extract

2.3.1.1. Membranes

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) membranes UF1-PAN and UF10-PAN with a molecular weight cut-off of 1 and 10 kDa, respectively, were used for membrane experiments.

2.3.1.2. Experimental system

A laboratory system equipped with a replaceable plate and frame membrane module was used for the ultrafiltration experiments [

8].

The following operating conditions during ultrafiltration were used: transmembrane pressure – from 0.2 to 0.4 MPa, volume reduction ratio (VRR) – from 2 to 6, feed flow rate – from 190 to 330 dm

3/h. All experiments were performed at 20°C. After experimental measurements of permeate’s volume (V, cm

3) separated from the membrane module for the time defined (t, s) under different working conditions, the flux (J, dm

3/(m

2.h)) was calculated using the following formula:

where

A = 0.125 m

2 is the membrane surface area in the module [

9].

Rejection (

R, %) and concentration factor (

CF) were calculated using the following formulas:

where

CP, C

R and

CO are the contents of the corresponding compounds in the permeate, retentate and feed solution, respectively.

The VRR was determined as follows:

where

VF was the feed solution’s volume, dm

3;

VR is the retentate’s volume, dm

3.

2.3.2. Phytochemical analyses

A spectrophotometer Helios Omega UV-Vis fitted with software VISIONlite (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA) with 1 cm path length cuvettes was used for all measurements.

2.3.2.1. Polyphenolic content

The total polyphenolic content (TPP) was established by the method of Singleton and Rossi [

10] with modifications described in previous our work [

9].

2.3.2.2. Total antioxidant capacity

The total antioxidant capacity was determined by the DPPH (free radical scavenging activity) and FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) assay described in previous our work [

9].

The method of Brand–Williams et al. [

11] with modifications described in [

9] was used for DPPH assay.

The method of Benzie and Strain [

12] with some modifications described in [

9] was applied for FRAP assay.

2.3.2.3. Protein content

The method of Bradford [

13] was used for protein content and the results were given as mg bovine serum albumin equivalents (BSAE) per 100 g on a dry weight basis.

2.4. Determination of dry matter content

The content of dry matter (total solids) was determined using a MLB 50-3 moisture analyzer (KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany).

2.5. Statistical analysis

The results of the current investigation were given as the averages of at least three determinations. One-way ANOVA in Microsoft Excel 2010 was used to compare the averages, utilizing Tukey's test at a 95% confidence level.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of membrane’s molecular weight cut-ff and process parameters on the permeate flux during ultrafiltration for concentration of polyphenols in rose petal extract

Figure 1 shows the permeate flux for both investigated membranes at different working conditions. The lowest results were obtained at p = 0.2 MPa, VRR = 6 and Q = 190 dm

3/h, while the highest – at p = 0.4 MPa, VRR = 2 and Q = 330 dm

3/h for both membranes. Comparing the flux with the two investigated membranes it can be seen that at the beginning of the process the highest flux was obtained with UF1-PAN membrane, but at the end of the process the highest flux was obtained with UF10-PAN membrane (

P < 0.05). Qaid et al. in 2017 [

14] found a positive correlation between the permeate flux and molecular weight cut-off of the membrane during ultrafiltration of Valencia orange juice. Acosta et al. in 2014 [

15] established that the permeate flux depended on the the MWCO of the membrane during ultrafiltration of blackberry (

Rubus adenotrichus Schltdl.) juice. It also can be seen from the figure that when the VRR increased, the permeate flux decreased. This is due to the concentration rise of the solutes which increases dynamic viscosity [

16], which led to a decrease in the flux. As reported by Cai et al. in 2020 [

17], this phenomenon was related to the cake layer which increased during the process, and thus the flux decreased. Similar results were obtained from Gaglianò et al. [

18] for diafiltered apple juice who established that the decrease in the permeate flux differed according to the membrane type. The transmembrane pressure had positive effect on the permeate flux for both membranes investigated. An explanation for this consists in the fact that a rise in the recirculation velocity benefits the hydrodynamical conditions, decreases the effect of the concentration polarization, improves the mass transfer coefficient, and thus the flux increases [

14]. The feed flow rate led to an increase in the permeate flux. According to Lai et al. in 2021 [

19], the cross-flow velocity rise led to a decrease in the concentration polarization on the membrane surface and an increase in the permeate flux. The same authors also improved that the permeate flux rise differed according to the membrane’s material. The increased transmembrane pressure can be applied when the flux decreased due to VRR rise.

3.2. Effects of membrane’s molecular weight cut-off and process parameters on the phytochemical characteristics of rose petal extract during ultrafiltration for concentration of polyphenols

Total polyphenols of the retentates increased by 27-39% and 26-67% during ultrafiltration with 1 kDa and 10 kDa membranes, respectively, depending on the volume reduction ratio (

Table 1). The highest concentration was observed for 10 kDa membrane at VRR 6. However, no significant differences were observed between all VRRs for 1 kDa membrane and between VRR 2 and VRR 4 for 10 kDa membrane (

P > 0.05). Moreover, the content of total polyphenols was similar for both membranes at VRR 2. Therefore, the concentration process depends not simply on the molecular weight, i.e. chemical structure, of the rose petal polyphenols, which are mainly flavonols [

8].

Juices contain polyphenols that may be associated with proteins, co-colored with other substances in the system, or condensed by oxidation. The presence of polyphenols may have a direct or indirect impact on additional ingredients in the juice [

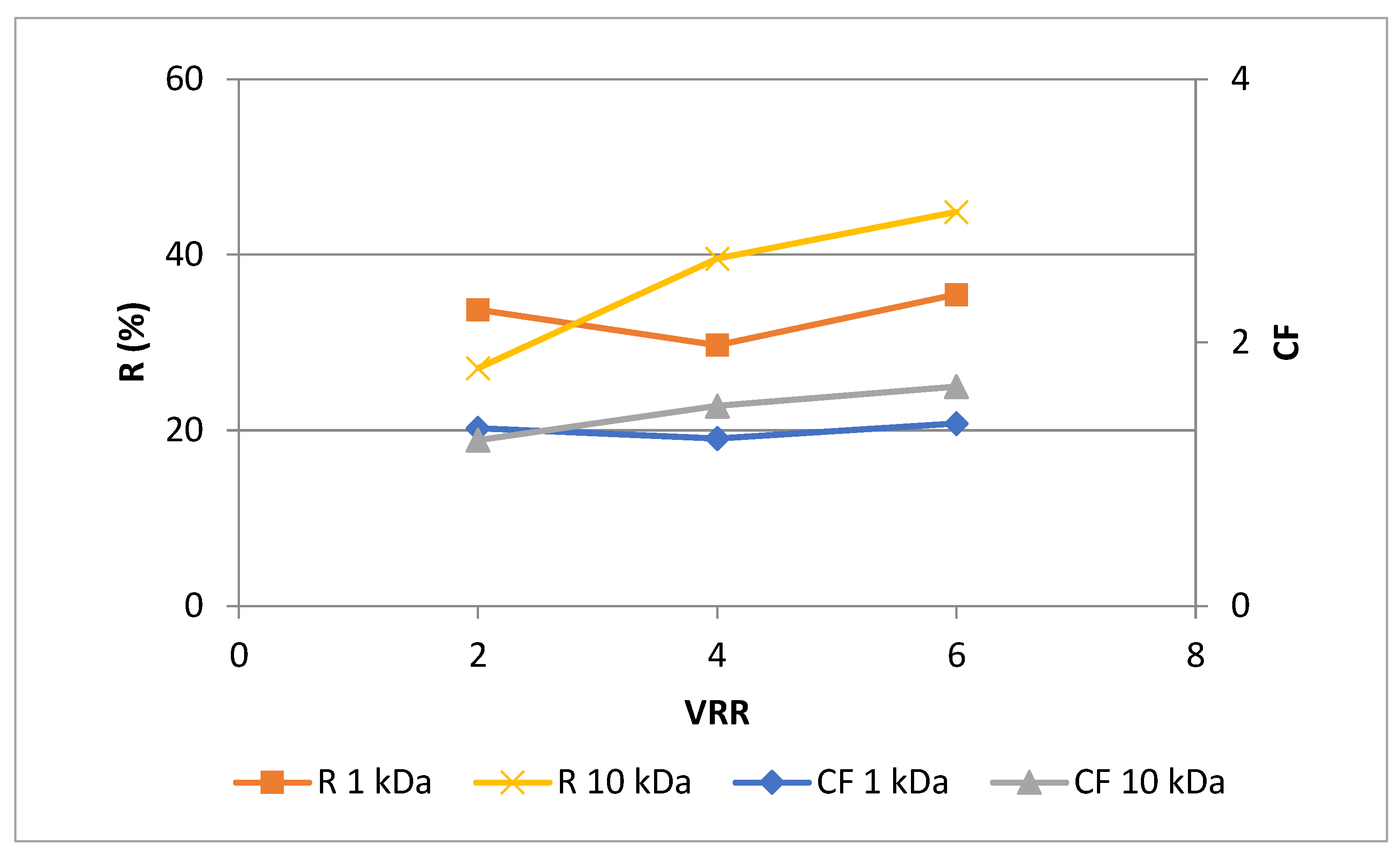

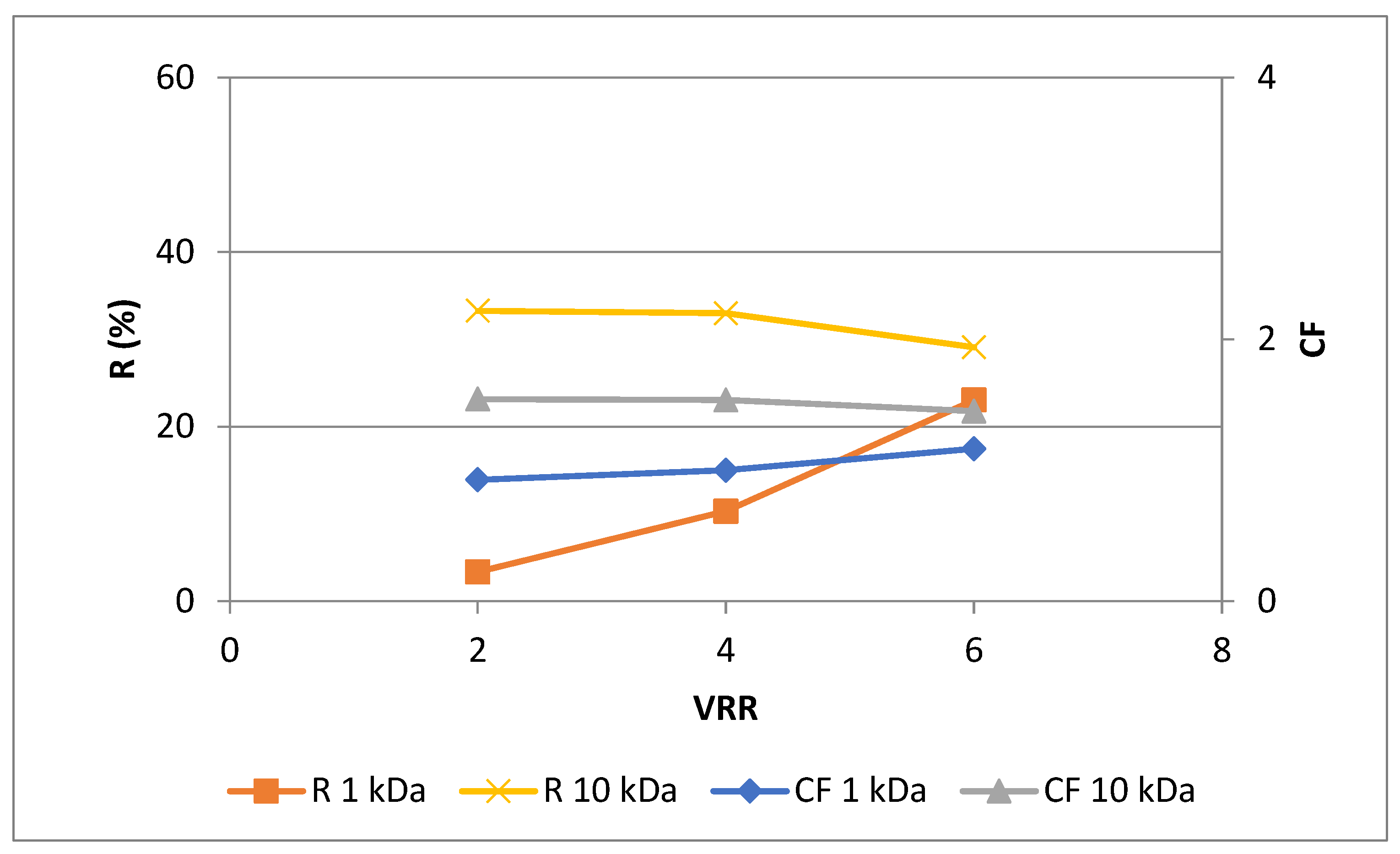

16]. As shown in

Figure 2, higher rejections (

P < 0.05) were observed for UF10-PAN membrane than for UF1-PAN for VRR 4 and 6, except VRR 2. The same trend was observed for the concentration factor. An increase in the values of both rejection and concentration factor was established with the concentration level’s rise (VRR) during ultrafiltration process, except the concentration factor at VRR 4 for UF1-PAN membrane. The highest values for the rejection and concentration factor were observed at VRR 6 for UF10-PAN – 44.9 % and 1.7, respectively. This shows the possibility of ultrafiltration to concentrate the polyphenols. Wei et al. in 2007 [

20] established an increase in the concentration factor and recovery of total polyphenols during the ultrafiltration of the apple juice with the feed concentration rise. Higher rejections of total polyphenols for 20 kDa membrane than for 30 kDa membrane during ultrafiltration of Valencia orange juice was published from Qaid et al. [

14]. Toker et al. in 2014 [

21] also established that the polyphenolic concentration depended on the MWCO of the membrane during ultrafiltration of blood orange juice. Galanakis et al. in 2013 [

22] found the highest rejections of total polyphenols and anthocyanins during ultrafiltration of winery sludge with 20 kDa membrane than with 1 kDa and 100 kDa. The polyphenolics concentration during ultrafiltration of apple juice depends also on the membrane material - hydrophilic or hydrophobic [

16]. According to Uyttebroek et al. [

23], the phenolic compounds from apple pomace can be successfully concentrated by nanofiltration, as well as in aqueous and ethanolic propolis extracts [

24].

Figure 3 presents the concentration factors and rejections of total solids depending on the VRR. Both parameters increased with the VRR rise from 2 to 6. Comparing the two membranes studied it could be seen that the 10 kDa membrane had higher values of these two parameters (

P < 0.05), except the concentration factor at VRR 2. The maximal value of rejection (63.3 %) was observed at VRR 6 when UF10-PAN was used, for the concentration factor – 2.13 at the same working conditions. This shows the possibility of ultrafiltration to concentrate the dry matter. Similar investigations for other foods were published by Farnasova et al. [

25] with potato juice. Acosta et al. in 2014 [

15] established the highest rejection of total solids with 5 kDa membrane, the lowest – with 150 kDa membrane during ultrafiltration of blackberry (

Rubus adenotrichus Schltdl.) juice. Within the investigated range of molecular weight cut-off, the authors found better rejection for 5 kDa, than for 1 kDa membrane.

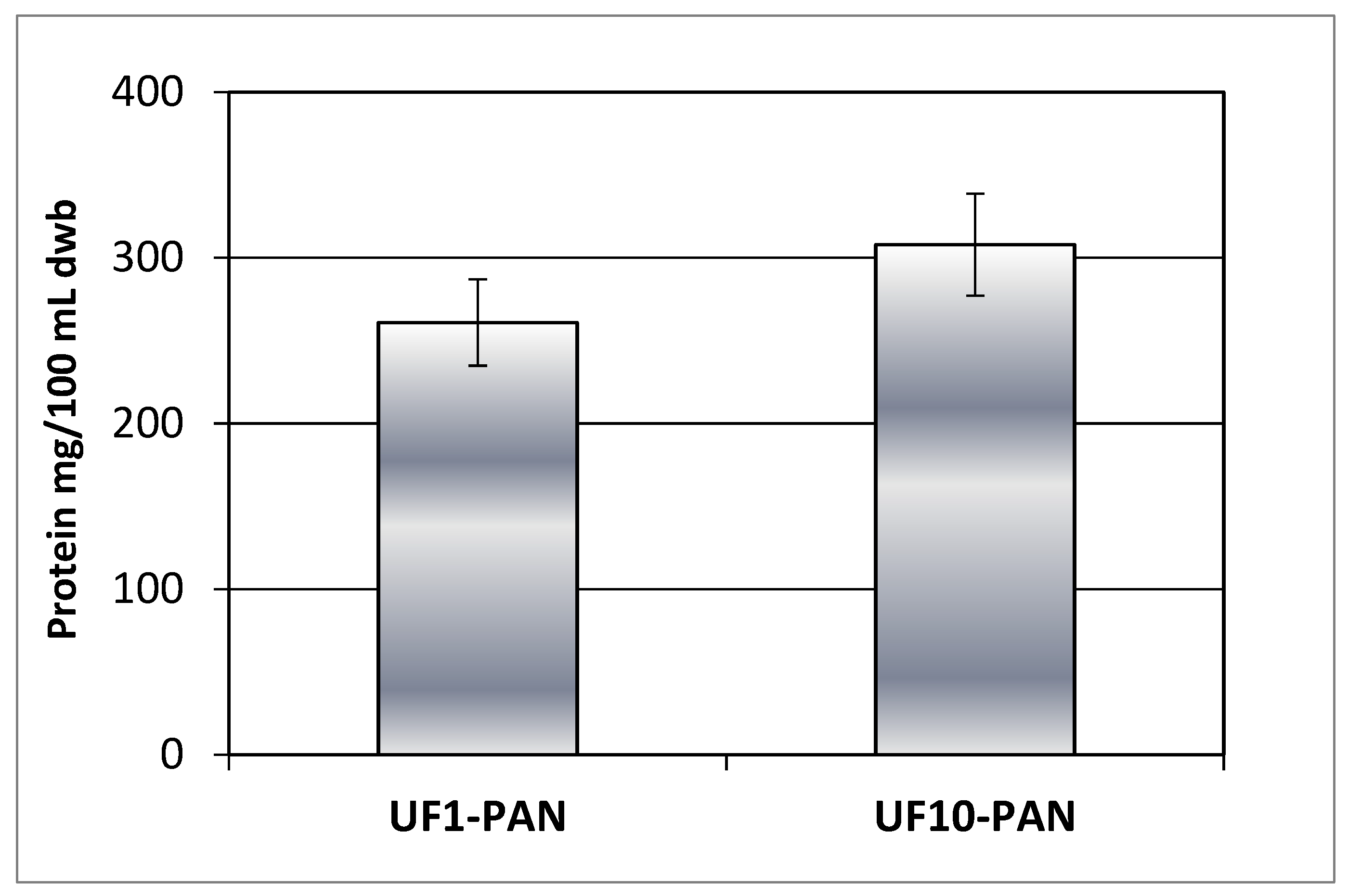

The results in

Figure 2 and 3 imply that polyphenols could form complexes with some polymeric matrix compounds, e.g. proteins released during the extensive enzyme catalysed degradation of the rose petal by-product, thus exhibiting similar concentration behavior during ultrafiltration with both 1 kDa and 10 kDa membranes. This assumption is supported by the similar values obtained for the protein content of retentates at VRR 6 (

Figure 4). Comparing the 50 kDa membranes produced from polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polyethersulfone (PES) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) during ultrafiltration of apple juice, Cai et al. in 2020 [

17] established the highest protein content for the PAN membrane.

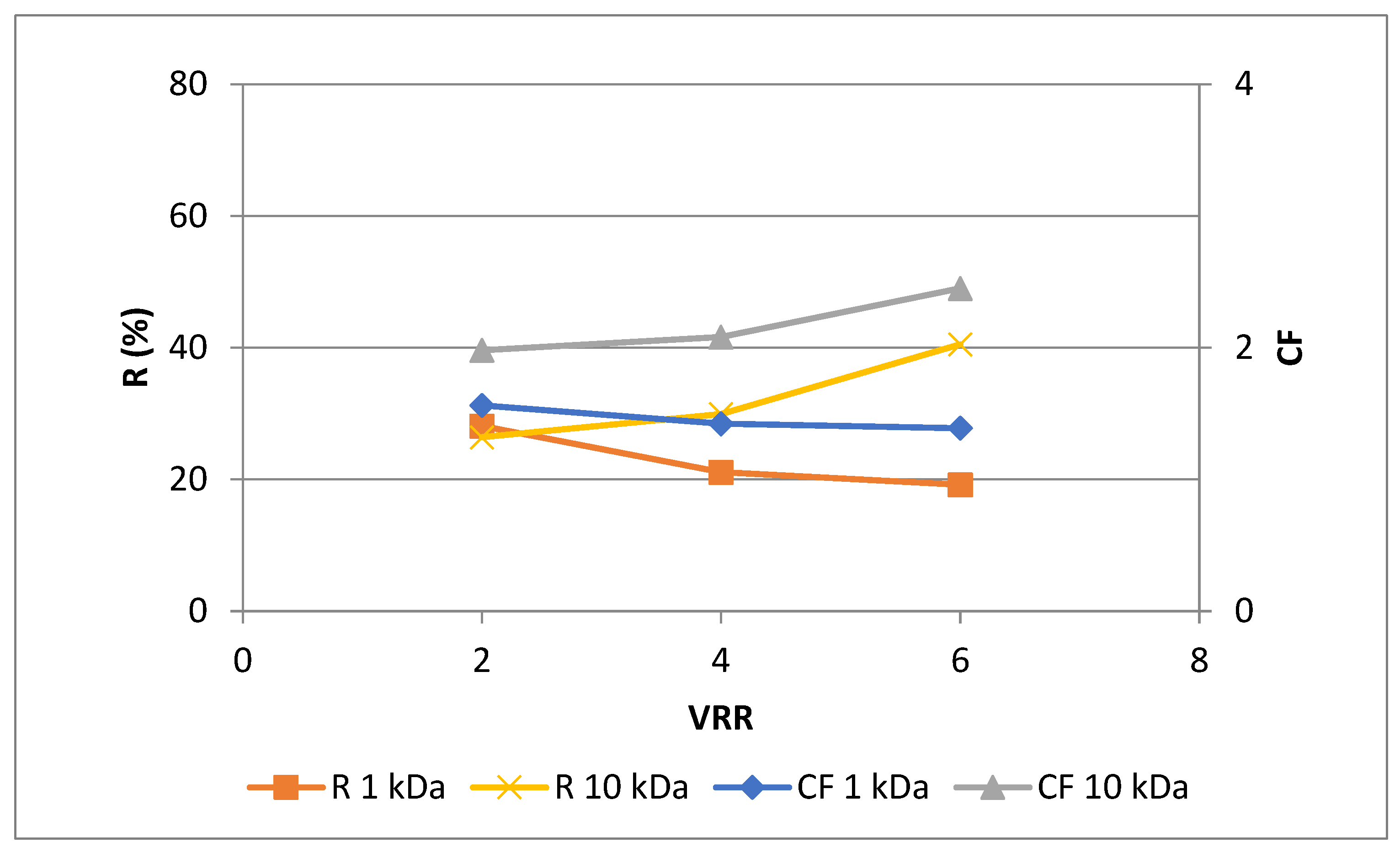

The two assays employed in this study reflect different mechanisms for assessing antioxidant capability. The FRAP test analyzes the overall quantity of redox-active substances, whereas the DPPH assay evaluates the capacity of plant extracts to scavenge free radicals [

26]. In general, the changes of the total antioxidant capacity (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) correspond to the concentration behavior of total polyphenols. Comparing both membranes used, it could be seen that the highest values of rejection and concentration factor of redox-active antioxidants (FRAP assay) was observed at VRR 6 with UF10-PAN membrane – 40.5 % and 2.5, respectively. Concerning the radical scavenging antioxidants (DPPH assay) presented in

Figure 6 it can be concluded that the highest values of rejection and concentration factor were obtained again for VRR 6 and UF10-PAN membrane – 29.1% and 1.5, respectively. The rejection of anthocyanins decreased in logarithmic proportion when the MWCO increased at ultrafiltration of roselle extract (

Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) [

27]. The total anthocyanins and total ellagitannins increased linearly with the MWCO decrease during ultrafiltration of blackberry (

Rubus adenotrichus Schltdl.) juice [

15]. Conidi et al. in 2017 [

28] established the lowest rejection value for total antioxidant activity with 1 kDa membrane than with 2 and 4 kDa.

The results obtained reveal the potential of polyphenol-enriched extract from rose petal by-product to increase the antioxidant capacity of other foods. This polyphenol fortification is also worthwhile from a technological point of view, it is an approach for quality improvement in fruit and food processing in general.

4. Conclusions

A new ultrafiltration-based process for green recovery of polyphenols from distilled (de-aromatized) rose petals, the primary by-product in essential oil production, was developed. The process includes enzyme-assisted extraction and subsequent membrane separation for partial concentration, thus offering an environmentally-friendly alternative to the conventional technology.

The results showed that the permeate flux decreased with VRR rise and increased with the transmembrane pressure and feed flow rate rises. At the beginning of the process the highest flux was with UF1-PAN membrane, but at the end of the process - with UF10-PAN membrane.

Total polyphenols of the retentates increased by 27-39% and 26-67% during ultrafiltration with 1 kDa and 10 kDa membranes, respectively, with the highest value obtained for the 10 kDa membrane at VRR 6. The highest concentration factor and rejection of total solids, total polyphenols, redox-active antioxidants and radical scavenging antioxidants were obtained at VRR 6 with UF10-PAN membrane. This membrane and concentration level at transmembrane pressure of 0.4 MPa and feed flow rate of 330 dm3/h are recommended to be used for application of ultrafiltration of rose-petals by-product for potential use in the food industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and K.M.; methodology, M.D. and K.M.; software, M.D., A.V., K.M. and M.T.; validation, M.D. and K.M.; formal analysis, M.D., A.V., V.S. and K.M..; investigation, M.D., A.V., K.M.; resources, M.D. and K.M.; data curation, M.D. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D., A.V., K.M.; writing—review and editing, M.D., A.V., K.M.; V.S., M.T..; visualization, M.D., K.M., and A.V.; supervision, M.D. and K.M.; project administration, M.D.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the fund “Science” at the University of Food Technologies—Plovdiv, Bulgaria, contract 14-18-H.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kroon, P. A.; Faulds, C. B.; Ryden, P.; Robertson, J. A.; Williamson, G. Release of covalently bound ferulic acid from fiber in the human colon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinli, K.; Block, G. Phytoestrogen content of foods: a compendium of literature values. Nutr. Cancer Int. J. 1996, 26, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlercreutz, H.; Mazur, W. Phyto-oestrogens and Western diseases. Ann. Med. 1997, 29, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseff, R. L.; Martin, S. F.; Youtsey, C. O. Quantitative survey of narirutin, naringin, heperidin, and neohesperidin in Citrus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokur,Y. ; Rodov, V.; Reznick, N.; Goldman, G.; Horev, B.; Umiei, N.; Friedman, H. Rose Petal Tea as an Antioxidant rich Beverage: Cultivar Effects. Food Sci. 2006, 71, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.W.; Frankel, E.N. Antioxidant activity of tea catechins in different lipid systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3033–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Jiao, B.; Drioli, E. Production of concentrated kiwifruit juice by integrated membrane processes. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, A.; Mihalev, K.; Berardini, N.; Mollov, P.; Carle, R. (2005). Flavonol glycosides from distilled petals of Rosa damascena Mill. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2005, 60, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, M.; Mihalev, K.; Dinchev, A.; Vasilev, K.; Georgiev, D.; Terziyska, M. Concentration of Polyphenolic Antioxidants in Apple Juice and Extract Using Ultrafiltration. Membranes (Basel). 2022, 12, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaid, S.; Zait, M.; EL Kacemi, K.; ELMidaoui, A.; EL Hajji. H.; Taky, M. Ultrafiltration for clarification of Valencia orange juice: comparison of two flat sheet membranes on quality of juice production. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, O.; Vaillant, F.; Pérez, A.M.; Dornier, M. Potential of ultrafiltration for separation and purification of ellagitannins in blackberry (Rubus adenotrichus Schltdl.) juice. Sep. Purif. Tecnol 2014, 125, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Clarification and concentration of pomegranate juice (Punica granatum L.) using membrane processes. J. Food Eng. 2011, 107, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Xie, C.; Lv, Y.; Yang, K.; Sun, P. Changes in physicochemical profiles and quality of apple juice treated by ultrafiltration and during its storage. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2913–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglianò, M.; Conidi, C.; De Luca, G.; Cassano, A. Partial removal of sugar from apple juice by nanofiltration and discontinuous diafiltration. Membranes 2022, 12, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.Q.; Tagashira, N.; Hagiwara, S.; Nakajima, M.; Kimura, T.; Nabetani, H. Influences of Technological Parameters on Cross-Flow Nanofiltration of Cranberry Juice. Membranes 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.S.; Hossain, M.; Saleh, Z.S. Separation of polyphenolics and sugar by ultrafiltration: Effects of operating conditions on fouling and diafiltration. Int. J. Nat. Sci. Eng. 2008, 1, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Toker, R; Karhan,M; Tetik,N; Turhan, I; Oziyci,H. R. Effect of Ultrafiltration and Concentration Processes on the Physical and Chemical Composition of Blood Orange Juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 38, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M.; Markouli, E.; Gekas, V. Recovery and fractionation of different phenolic classes from winery sludge using ultrafiltration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 107, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyttebroek, M,; Vandezande, P. ; Miet Van Dael, M.V; Vloemans, S.; Noten, B.; Bongers, B,; Porto-Carrero, W.; Unamunzaga, M.M.; Bulut, M.; Lemmens, B. Concentration of phenolic compounds from apple pomace extracts by nanofiltration at lab and pilot scale with a techno-economic assessment. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12629. [CrossRef]

- Mello, B.C.B.S.; Petrus, J.C.C.; Hubinger, M.D. Concentration of flavonoids and phenolic compounds in aqueous and ethanolic propolis extracts through nanofiltration. J. Food Eng. 2010, 96, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnosova, E.N.; Rid, A.A.; Morozova, Y.A. Purification and concentration of potato juice by ultrafiltration and nanofiltration. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 723, 022066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, L.M.; Segundo, M.A.; Reis, S.; Lima, J.L.F.C. Methodological aspects about in vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 613, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissé, M.; Vaillant, F.; Pallet, D.; Dornier, M. Selecting ultrafiltration and nanofiltration membranes to concentrate anthocyanins from roselle extract (Hibiscus sabdariffa L. ). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2607–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conidi, C.; Cassano, A.; Caiazzo, F.; Drioli, E. Separation and purification of phenolic compounds from pomegranate juice by ultrafiltration and nanofiltration membranes. J. Food Eng. 2017, 195, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).