Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Rose Wastewater

2.1.2. Chemicals

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Coarse filtration

2.2.3. Membrane Filtration

2.2.4. Determination of the Key Parameters of the Ultrafiltration Process

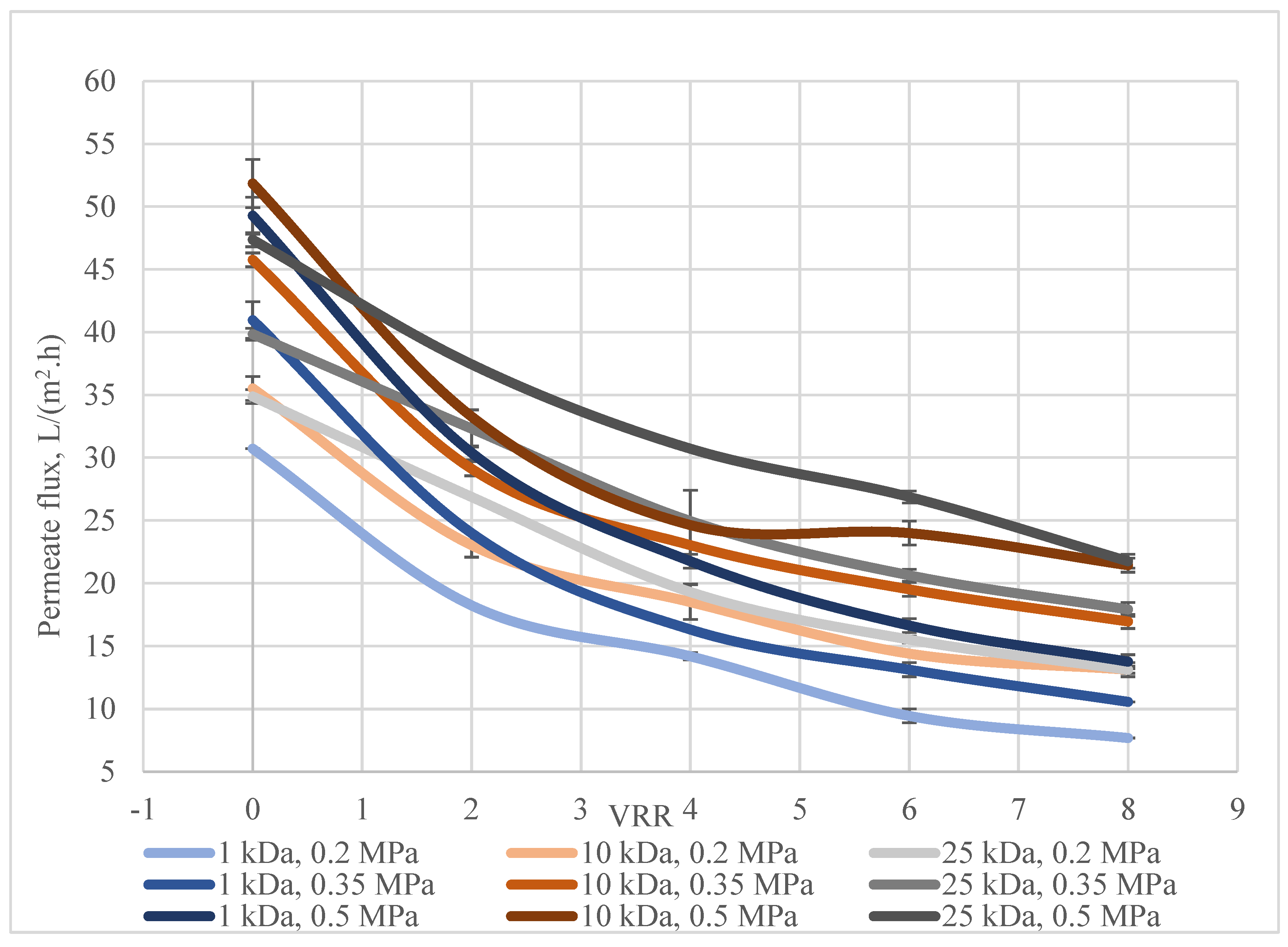

- The permeate flux (J, L/(m2h)) was determined using the following formula:

- The volume reduction ratio was determined by the formula:

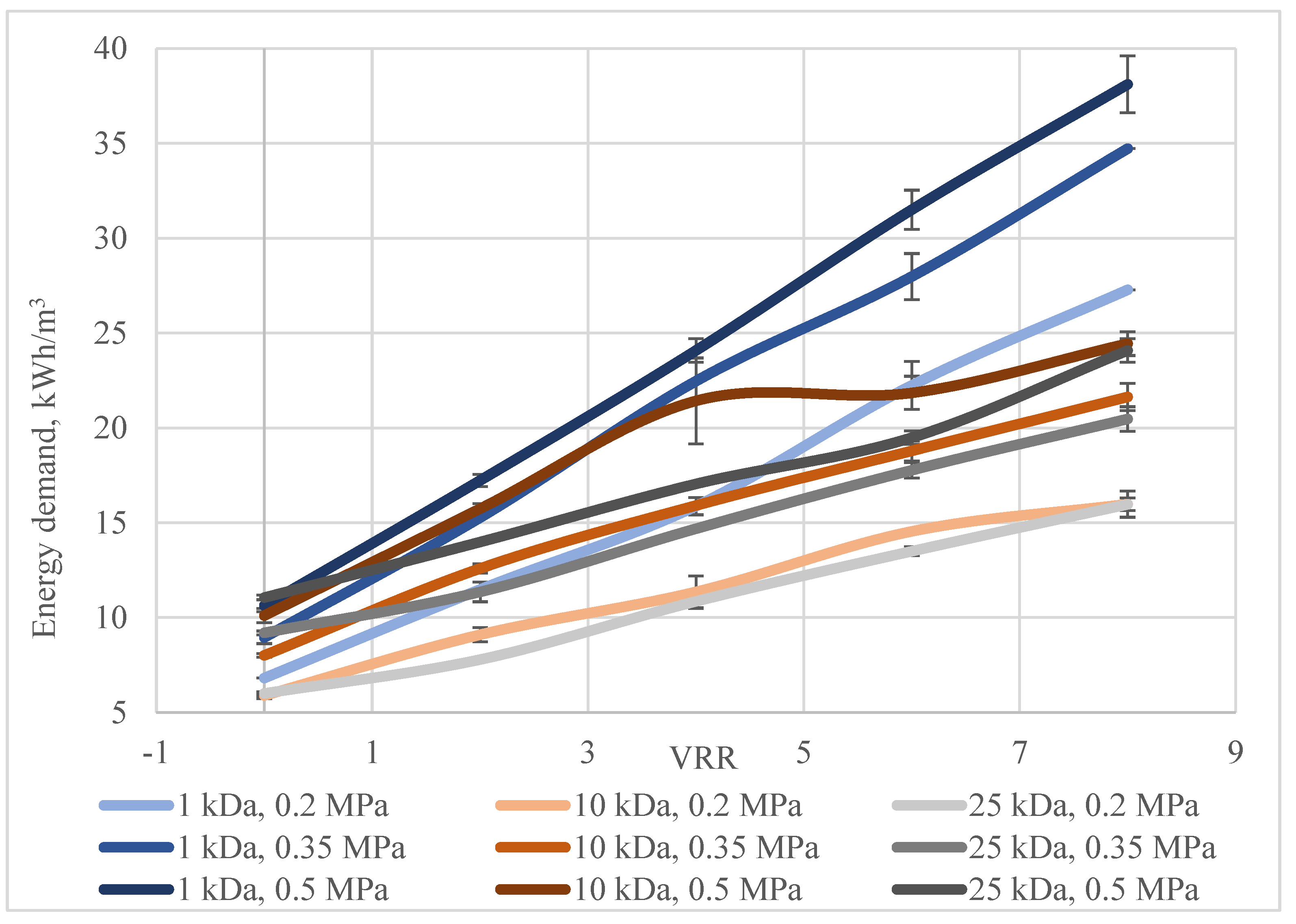

- Energy demand was calculated as:

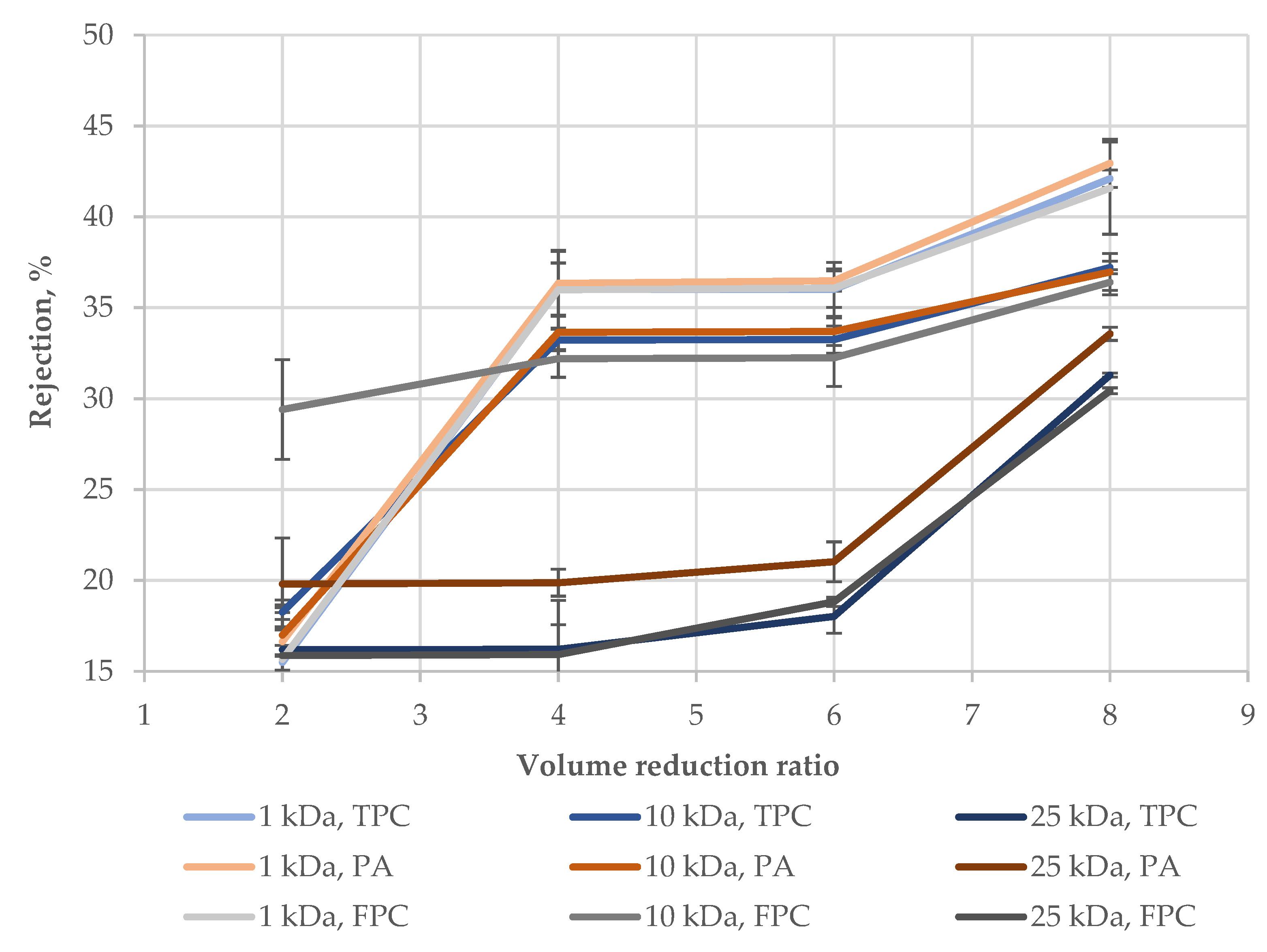

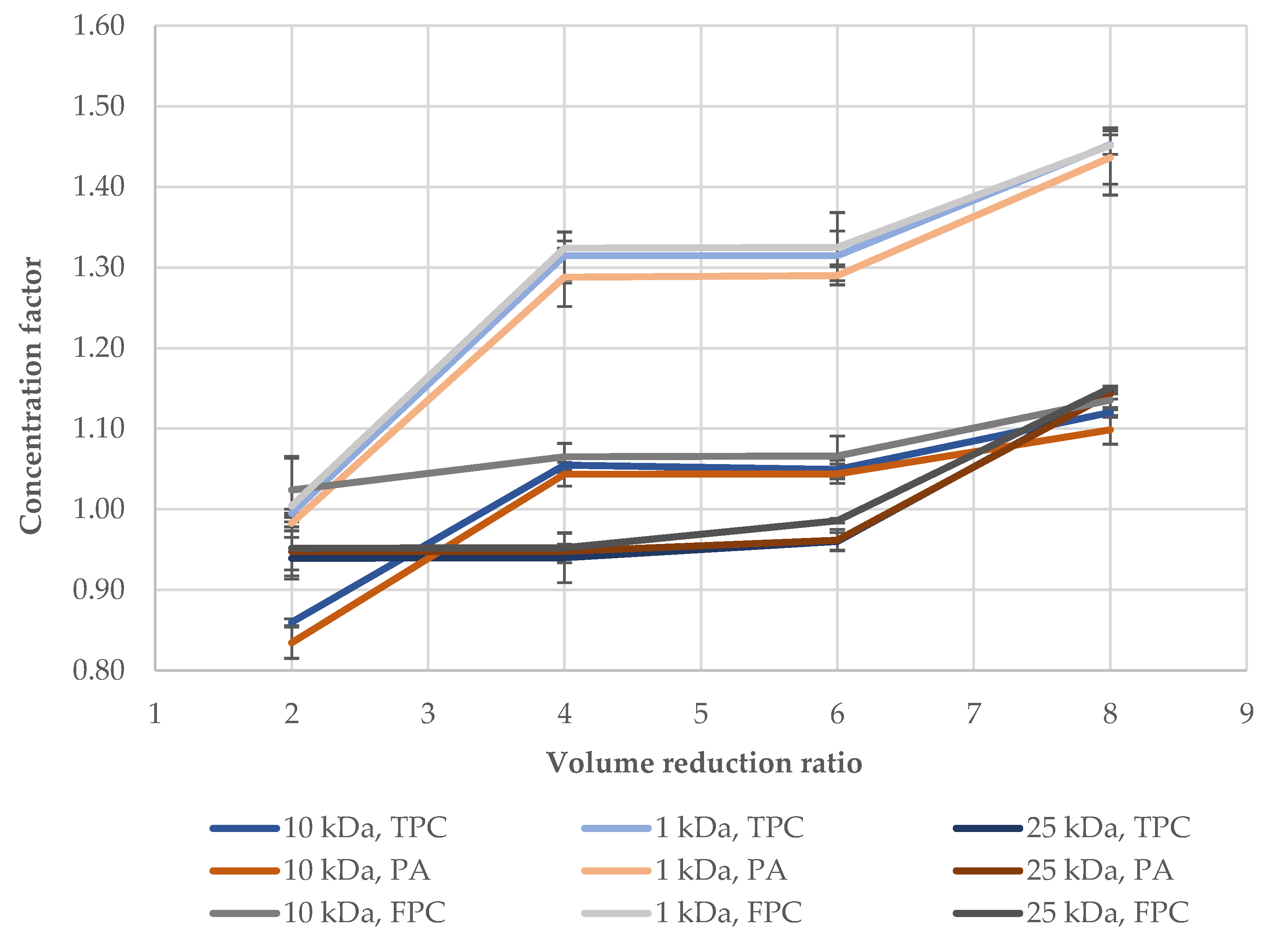

- Rejection and concentration factor were determined by the equations:

2.2.5. Determination of Phenolic Compounds

2.2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.2.7. HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

2.2.8. Statistical Analysis

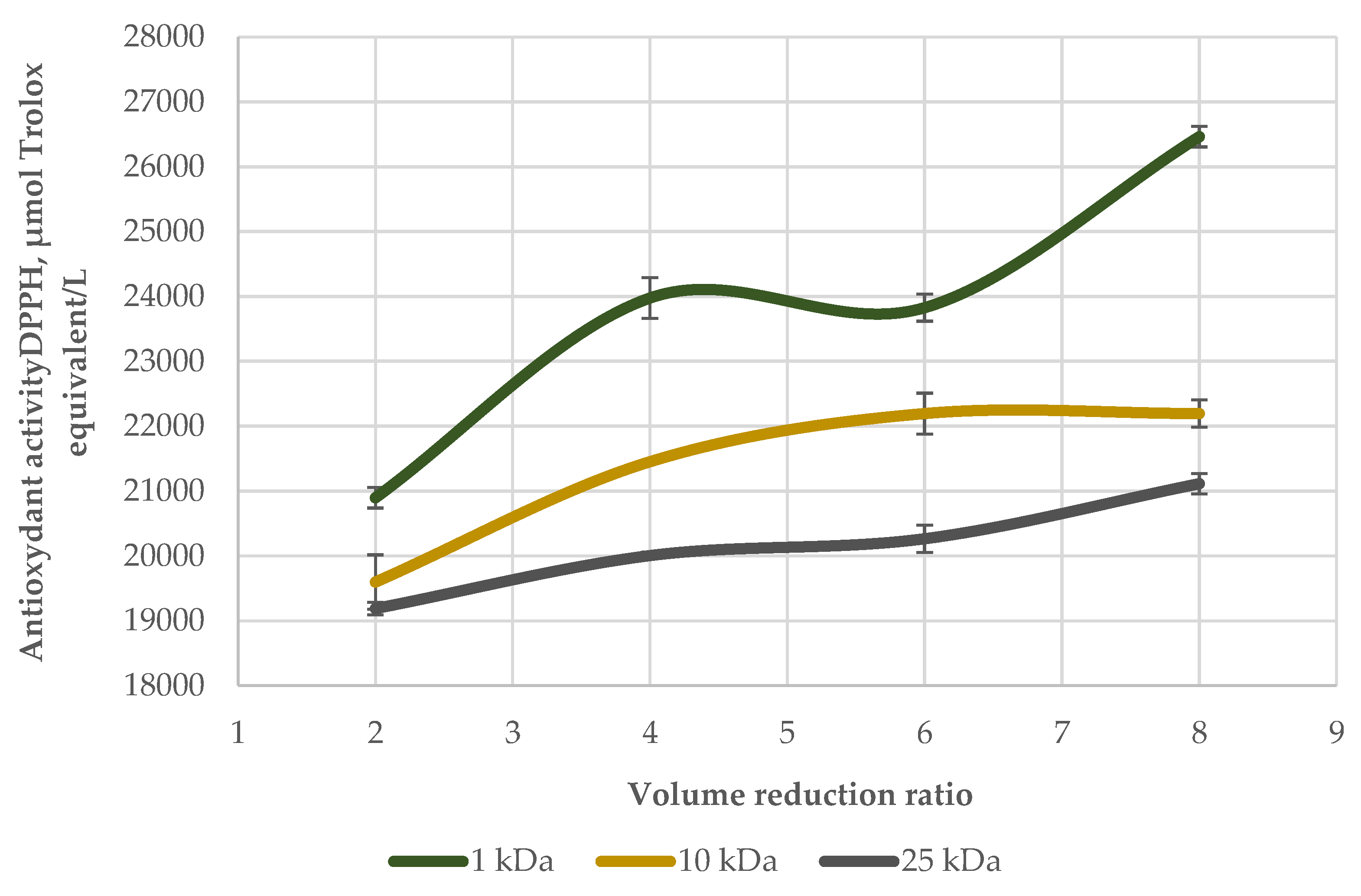

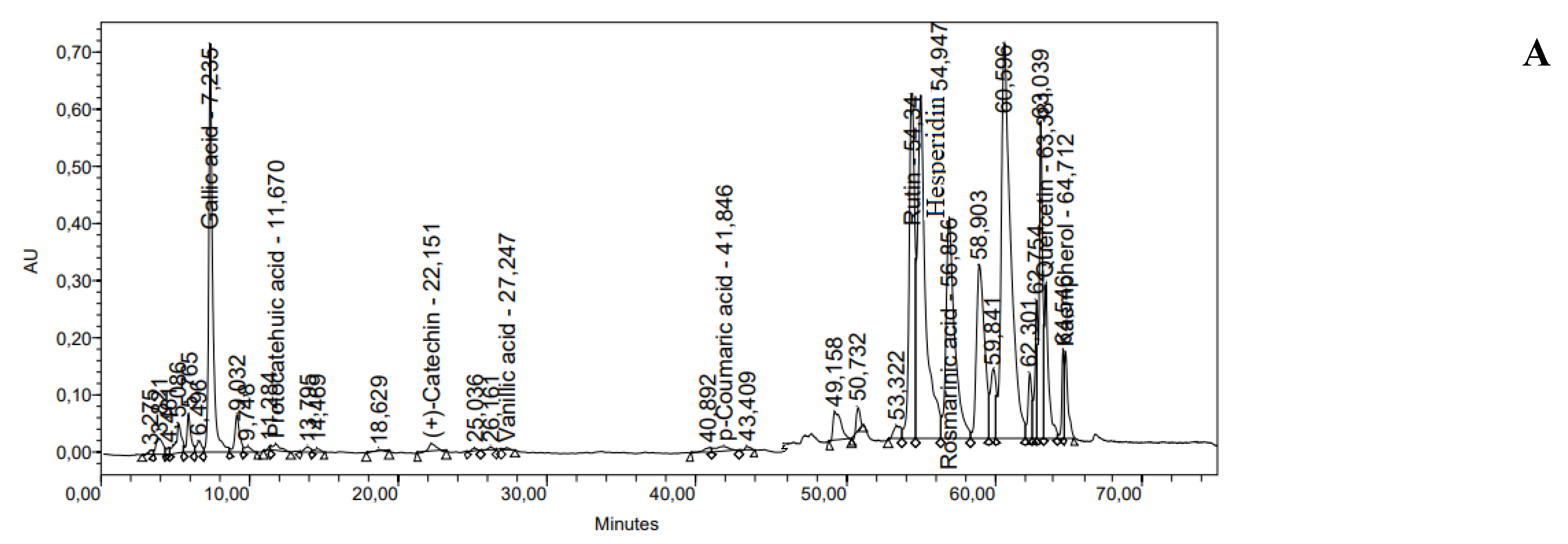

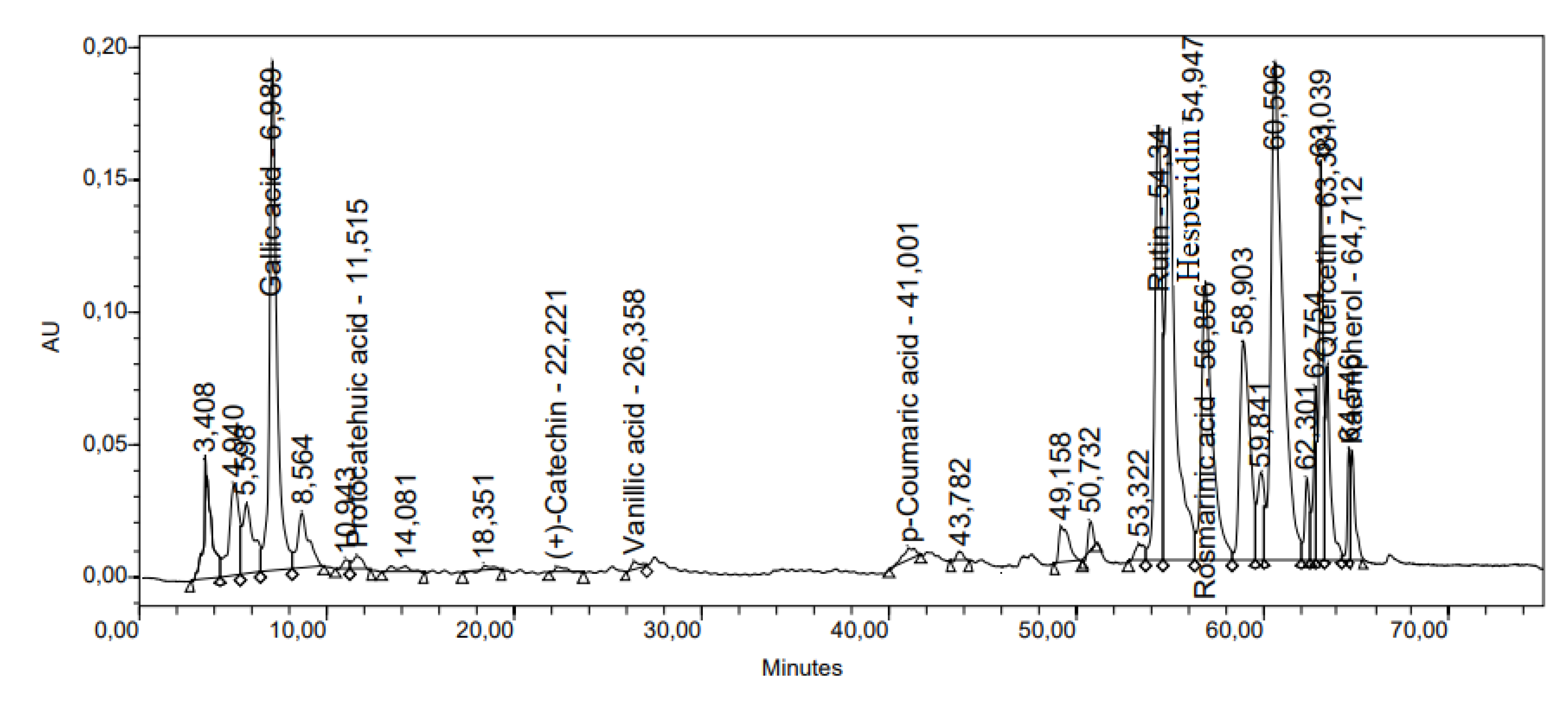

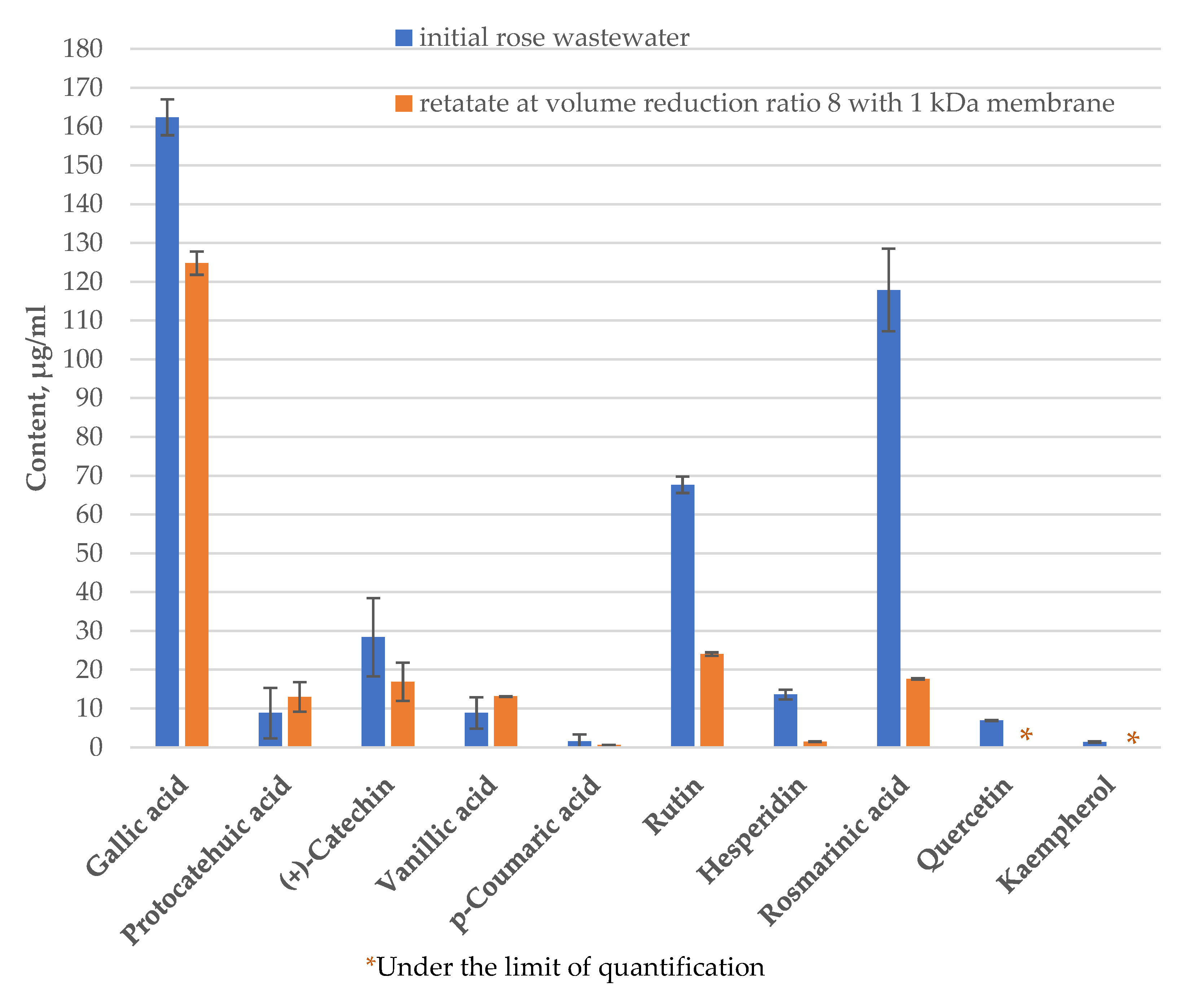

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mallek-Ayadi, S.; Bahloul, N.; Kechaou, N. Chemical composition and bioactive compounds of Cucumis melo L. seeds: Potential source for new trends of plant oils Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2018, 113, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winans, K.; Kendall, A.; Deng, H. The history and current applications of the circular economy concept. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 68, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsar, Y.; Kurt, U.; Gonullu, T. Comparison of classical chemical and electrochemical processes for treating rose processing wastewater. Journal of Hazardous Materials. [CrossRef]

- Ueda, J.M.; Pedrosa, M.C.; Heleno, S.A.; Carocho, M. , Ferreira, I.C.F.R., Barros, L. Food additives from fruit and vegetable by-products and bio-residues: A comprehensive review focused on sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.M.; dos Santos, P.N.; Santos, F.H.; Molina, G.; Pelissari, F.M. Sustainability approaches for agrowaste solution: Biodegradable packaging and microbial polysaccharides bio-production. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 886, 163922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobreva, A.; Nedeva, D.; Mileva, M. Comparative study of the yield and chemical profile of rose oils and hydrosols obtained by industrial plantations of oil-bearing roses in Bulgaria. Resources 2023, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsobh, A.; Zin, M.M.; Vatai, G.; Bánvölgyi, S. The application of membrane technology in the concentration and purification of plant extracts: A review. Periodica Polytechnica Chemical Engineering 2022, 66, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova, R.; Vardakas, A.; Dimitrova, E.; Weber, F.; Passon, M.; Shikov, V.; Schieber, A.; Mihalev, K. Valorization of rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) by-product: polyphenolic characterization and potential food application. European Food Research and Technology 2022, 248, 2351–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Conidi, C.; Ruby-Figueroa, R.; Castro-Muñoz, R. Nanofiltration and tight ultrafiltration membranes for the recovery of polyphenols from agro-food by-products. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragoev, S.; Vlahova-Vangelova, D.; Balev, D.; Bozhilov, D.; Dagnon, S. Valorization of waste by-products of rose oil production as feedstuff phytonutrients. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science 2021, 27, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochev, V.; Dobreva, A.; Girova, T.; Stoyanova, A. Antimicrobial activity of essential oil from Rosa alba. Biotechnology and Biotechnological Equipment 2010, 24, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, D.V.; Medarska, Y.N.; Stoyanova, A.S.; Nenov, N.S.; Slavov, A.M.; Antonov, L.M. Chemical profile and sensory evaluation of Bulgarian rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) aroma products, isolated by different techniques. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2021, 33, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassem, H.H.A.; Nour, A.H.; Yunus, R.M. Techniques for extraction of essential oils from plants: A review. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2016, 10, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, C.A.; Oliveira, F.O.; de Andrade, M.A.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Lepikson, H.; Machado, B.A.S. Steam distillation for essential oil extraction: An evaluation of technological advances based on an analysis of patent documents. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chroho, M.; Bouymajane, A.; Oulad El Majdoub, Y.; Cacciola, R.; Mondello, L.; Aazzaa, M.; Zair, T.; Bouissane, L. Phenolic composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of extract from flowers of Rosa damascena from Morocco. Separations 2022, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, S.; Gago, P.; Santiago, J.L.; Álvarez-Acero, I.; Bartolomé, M.A.M.; Martínez, M.C. Polyphenols in the waste water produced during the hydrodistillation of ‘Narcea roses’ cultivated in the Cibea river valley (Northern Spain). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Ugarte, G.A.; Juárez-Becerra, G.P.; Sosa-Morales, M.E.; López-Malo, A. Microwave-assisted extraction of essential oils from herbs. Journal of Microwave Power and Electromagnetic Energy 2013, 47, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalcheva-Karadzhova, K.; Shikov, V.; Mihalev, K.; Dobrev, G.; Ludneva, D.; Penov, N. Enzyme-assisted extraction of polyphenols from rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) petals. Acta Universitatis Cibiniensis - Series E: Food Technology 2014, 18, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, Y.; Dimitrova, L.; Georgieva, A.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Kokanova-Nedialkova, Z.; Dobreva, A.; Nedialkov, P.; Kussovski, V.; Kroumov, A.D.; Najdenski, H.; Mileva, M. In vitro study of the biological potential of wastewater obtained after the distillation of four Bulgarian oil-bearing roses. Plants 2022, 11, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-González, C.; Ramos, C.M.; Martínez-Correa, H.A.; García, H.F.L. Extraction and concentration of spirulina water-soluble metabolites by ultrafiltration. Plants 2024, 13, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, B.X.; Guo, M. Current advances in screening for bioactive components from medicinal plants by affinity ultrafiltration mass spectrometry. Phytochemical Analysis 2018, 29, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, A.W.; Ng, C.Y.; Lim, Y.P.; Ng, G.H. Ultrafiltration in food processing industry: Review on application, membrane fouling, and fouling control. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2012, 5, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, L.R.; Yadav, D.; Borah, D.; Gogoi, A.; Goswami, S.; Hazarika, G.; Karki, S.; Gohain, M.B.; Sawake, S.V.; Jadhav, S.V.; Chatterjee, S.; Ingole, P.G. Polymeric membranes for liquid separation: Innovations in materials, fabrication, and industrial applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia-Quirós, P.; Montenegro-Landívar, M.F.; Reig, M.; Vecino, X.; Cortina, J.L.; Saurina, J.; Granados, M. Recovery of polyphenols from agri-food by-products: The olive oil and winery industries cases. Foods 2022, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dushkova, M.; Vardakas, A.; Shikov, V.; Mihalev, K.; Terzyiska, M. Application of ultrafiltration for recovery of polyphenols from rose petal byproduct. Membranes 2023, 13, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dintcheva, N.T.; Morici, E. Recovery of rose flower waste to formulate eco-friendly biopolymer packaging films. Molecules 2023, 28, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Vasileva, I.; Stefanov, L.; Stoyanova, A. Valorization of wastes from the rose oil industry. Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology 2017, 16, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, M.; Mihalev, K.; Dinchev, A.; Vasilev, K.; Georgiev, D.; Terziyska, M. Concentration of polyphenolic antioxidants in apple juice and extract using ultrafiltration. Membranes 2022, 12, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberk, J.Q.J.C.; Van Dijk, J.C. Air sparging in capillary nanofiltration. Journal of Membrane Science 2006, 284, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glories, Y. Reserches sur la matière colorante des vins rouges. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de France 1979, 9, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Science and Technology 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Clarification and concentration of pomegranate juice (Punica granatum L.) using membrane processes. Journal of Food Engeneering 2011, 107, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Donato, L.; Drioli, E. Ultrafiltration of kiwifruit juice: Operating parameters, juice quality and membrane fouling. Journal of Food Engineering 2007, 79, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Xie, C.; Lv, Y.; Yang, K.; Sun, P. Changes in physicochemical profiles and quality of apple juice treated by ultrafiltration and during its storage. Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 8, 2913–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaid, S.; Zait, M.; El Kacemi, K.; El Midaoui, A.; El Hajji, H.; Taky, M. Ultrafiltration for clarification of Valencia orange juice: Comparison of two flat sheet membranes on quality of juice production. Journal of Materials and Environmental Science 2017, 8, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Gaglianò, M.; Conidi, C.; De Luca, G.; Cassano, A. Partial removal of sugar from apple juice by nanofiltration and discontinuous diafiltration. Membranes 2022, 12, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, O.; Vaillant, F.; Pérez, A.M.; Dornier, M. Potential of ultrafiltration for separation and purification of ellagitannins in blackberry (Rubus adenotrichus Schltdl.) juice. Separation and Purification Technology 2014, 125, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Bagci, P.O. Ultrafiltration of broccoli juice using polyethersulfone membrane: Fouling analysis and evaluation of the juice quality. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2019, 12, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Bruggen, B.; Vandecasteele, C.; Gestel, T.V.; Doyen, W.; Leysen, R. A review of pressure-driven membrane processes in wastewater treatment and drinking water production. Environmental Progress 2003, 22, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnasawy, H.; Shenana, M. Flux behavior and energy consumption of ultrafiltration (UF) process of milk. Australian Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2010, 1, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Méthot-Hains, S.; Benoit, C.; Bouchard, C.; Doyen, A.; Bazinet, L.; Pouliot, Y. Effect of transmembrane pressure control on energy efficiency during skim milk concentration by ultrafiltration at 10 and 50°C. Journal of Dairy Science 2016, 99, 8655–8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehl, C. J.; Zydney, A.L. Characterization of dextran transport and molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of large pore size hollow fiber ultrafiltration membranes, Journal of Membrane Science 2021, 622, 119025. 622. [CrossRef]

- Toker, R.; Karhan, M.; Tetik, N.; Turhan, I.; Oziyci, H.R. Effect of ultrafiltration and concentration processes on the physical and chemical composition of blood orange juice. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2014, 38, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Biswas, P.P.; De, S. Clarification and storage study of bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria) juice by hollow fiber ultrafiltration. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2016, 100, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.S.; Hossain, M.; Saleh, Z.S. Separation of polyphenolics and sugar by ultrafiltration: Effects of operating conditions on fouling and diafiltration. International Journal of Natural and Engineering Sciences 2007, 1, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cissé, M.; Vaillant, F.; Pallet, D.; Dornier, M. Selecting ultrafiltration and nanofiltration membranes to concentrate anthocyanins from roselle extract (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.). Food Research International 2011, 44, 2607–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, B.; Cheng, N.; Gao, H.; Cao, W. Effects of molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) on jujube juice quality during ultrafiltration. Acta Hortic 2013, 993, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Carretero, I.; Coves, J.R.; Pedrouso, A.; Castro-Barros, C.M.; Alvarino, T.; Cortina, J.L.; Saurina, J.; Granados, M.; Sentellas, S. Recovery of phenolic compounds from wine lees using green processing: Identifying target molecules and assessing membrane ultrafiltration performance, Science of The Total Environment 2023, 857, 159623. 857. [CrossRef]

| № | Membrane Solution type: |

1 kDa | 10 kDa | 25kDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic compounds, mg/dm3 gallic acid equivalent | ||||

| 1 | Initial rose wastewater | 1646.66±10.78a | 1646.66±10.78a | 1646.66±10.78a |

| 2 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 2 | 1638.55±8.24a,A | 1415.89±6.87b,B | 1546.66±42.51b,C |

| 3 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 4 | 2164.40±48.79b,c,A | 1736.90±15.38c,B | 1547.47±50.46b,C |

| 4 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 6 | 2164.49±50.74b,A | 1727.90±19.41c,B | 1581.32±12.71b,C |

| 5 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 8 | 2391.57±19.87c,A | 1844.56±10.01d,B | 1885.77±2.95c,C |

| 6 | Permeate | 1384.64±13.34d,A | 1154.66±46.43e,B | 1295.57±7.27d,C |

| Phenolic acids, mg/dm3 caffeic acid equivalent | ||||

| 1 | Initial rose wastewater | 387.72±7.61a | 387.72±7.61a | 529.03±8.89a |

| 2 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 2 | 381.06±3.69a,A | 323.54±7.51b,B | 503.52±14.20b,B |

| 3 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 4 | 499.32±14.04b,A | 404.61±5.79c,B | 503.73±9.87a,C |

| 4 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 6 | 500.07±4.37b,A | 404.86±4.64c,B | 521.58±1.61b,C |

| 5 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 8 | 556.94±12.88c,A | 425.96±6.93d,B | 608.63±1.38c,B |

| 6 | Permeate | 317.65±7.18d,A | 268.46±16.68e,B | 423.38±3.22d,C |

| Flavonoid phenolic compounds, mg/dm3 quercetin | ||||

| 1 | Initial rose wastewater | 529.03±8.89a | 529.03±8.89a | 529.03±8.89a |

| 2 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 2 | 531.22±4.83a,A,B | 541.70±20.95a,b,A | 503.52±14.20b,B |

| 3 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 4 | 700.43±22.87b,A | 563.64±8.63b,B | 503.73±9.87a,C |

| 4 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 6 | 700.93±11.56c,A | 564.00±13.12b,B | 521.58±1.61b,C |

| 5 | Retentate at volume reduction ratio 8 | 767.83±32.55d,A | 600.76±6.47c,B | 608.63±1.38c,B |

| 6 | Permeate | 448.03±8.87e,A | 382.04±18.09d,B | 423.38±3.22d,C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).