Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Crude palm oil

2.2. Catalyst

2.3. Experimental apparatus

2.3.1. Thermal catalytic cracking pilot plant

2.3.2. Distillation laboratory unit

2.4. Experimental procedures

2.4.1. Thermal catalytic cracking

2.4.2. Mass balance of the thermal catalytic cracking process

2.4.3. Evaluation of reaction time

2.4.4. Evaluation of catalyst reuse

2.4.5. Distillation of the OLP

2.4.6. Mass balance of the distillation process

2.5. Characterization of the OLP and distilled fractions

2.5.1. Physical-chemical properties

2.5.2. FTIR spectroscopy

2.5.3. Distillation curve of the distilled fractions

2.5.4. GC–MS analysis of the distilled fractions

3. Results and discussion

3.1. GC-MS Analysis of Crude Palm Oil

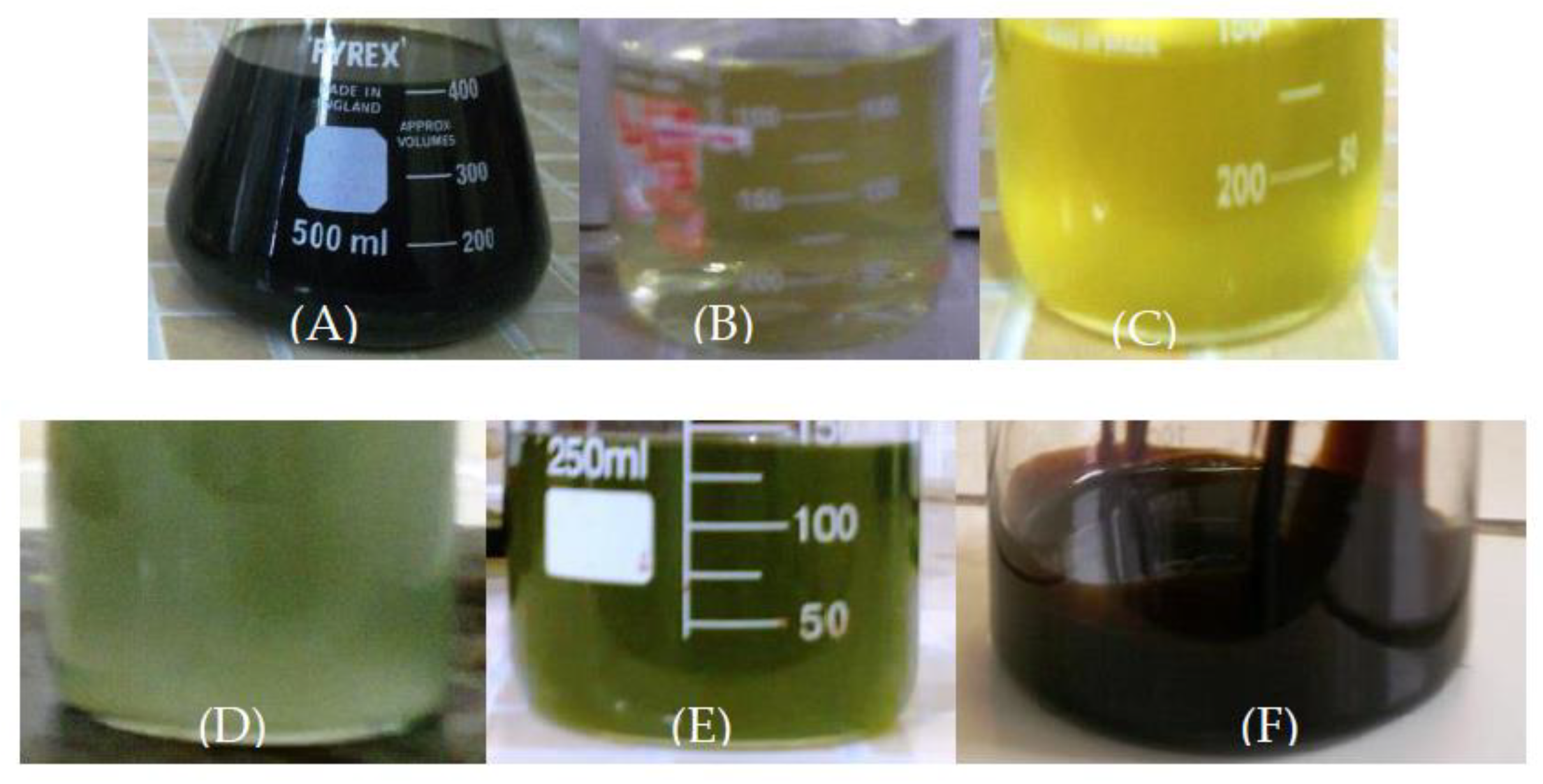

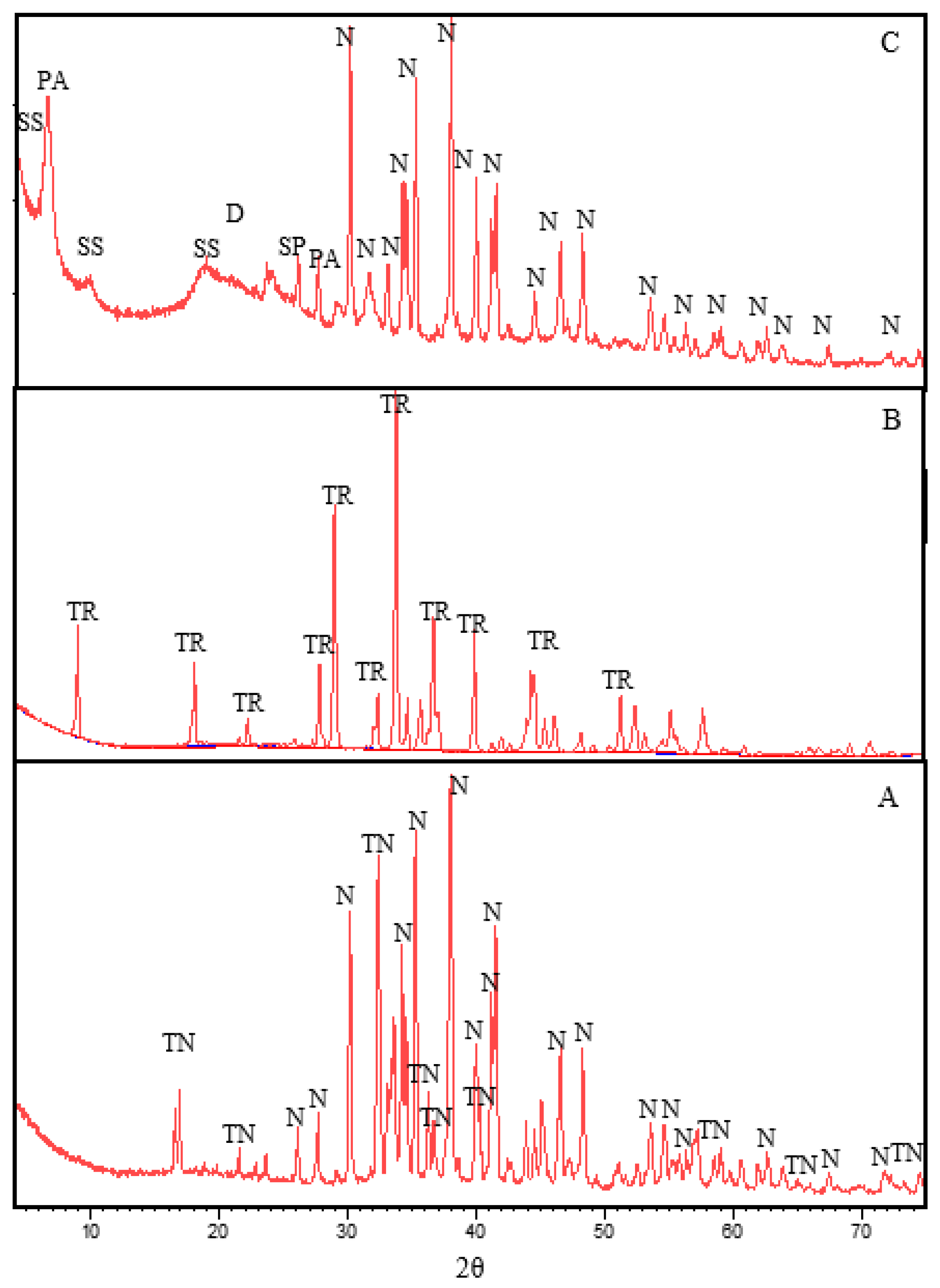

3.2. X-ray diffraction

3.3. Influence of catalyst reuse on OLP yield

3.4. Influence of catalyst reuse on OLP quality

3.4.1. Physical-chemical properties

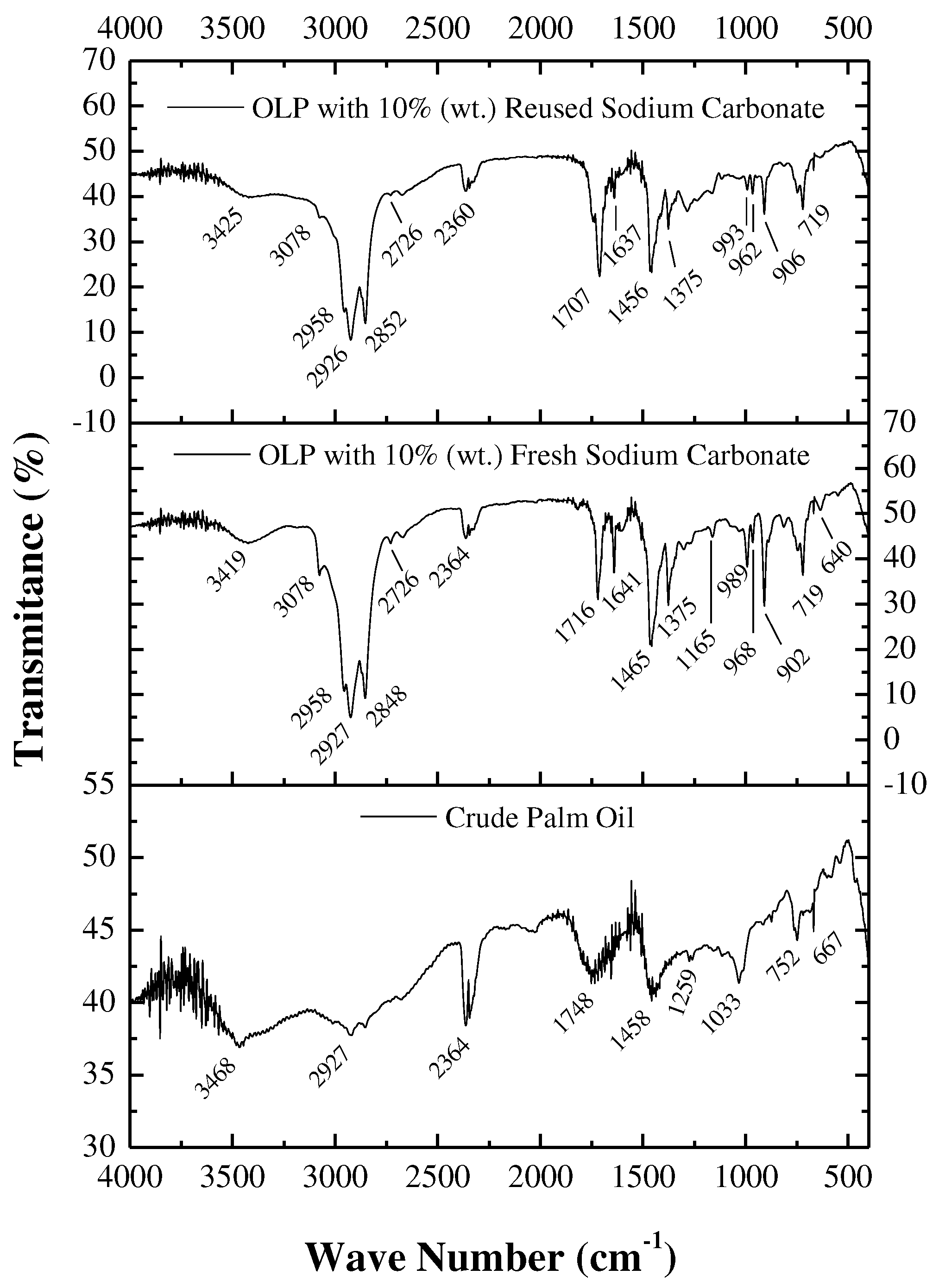

3.4.2. FTIR spectroscopy

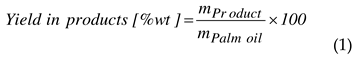

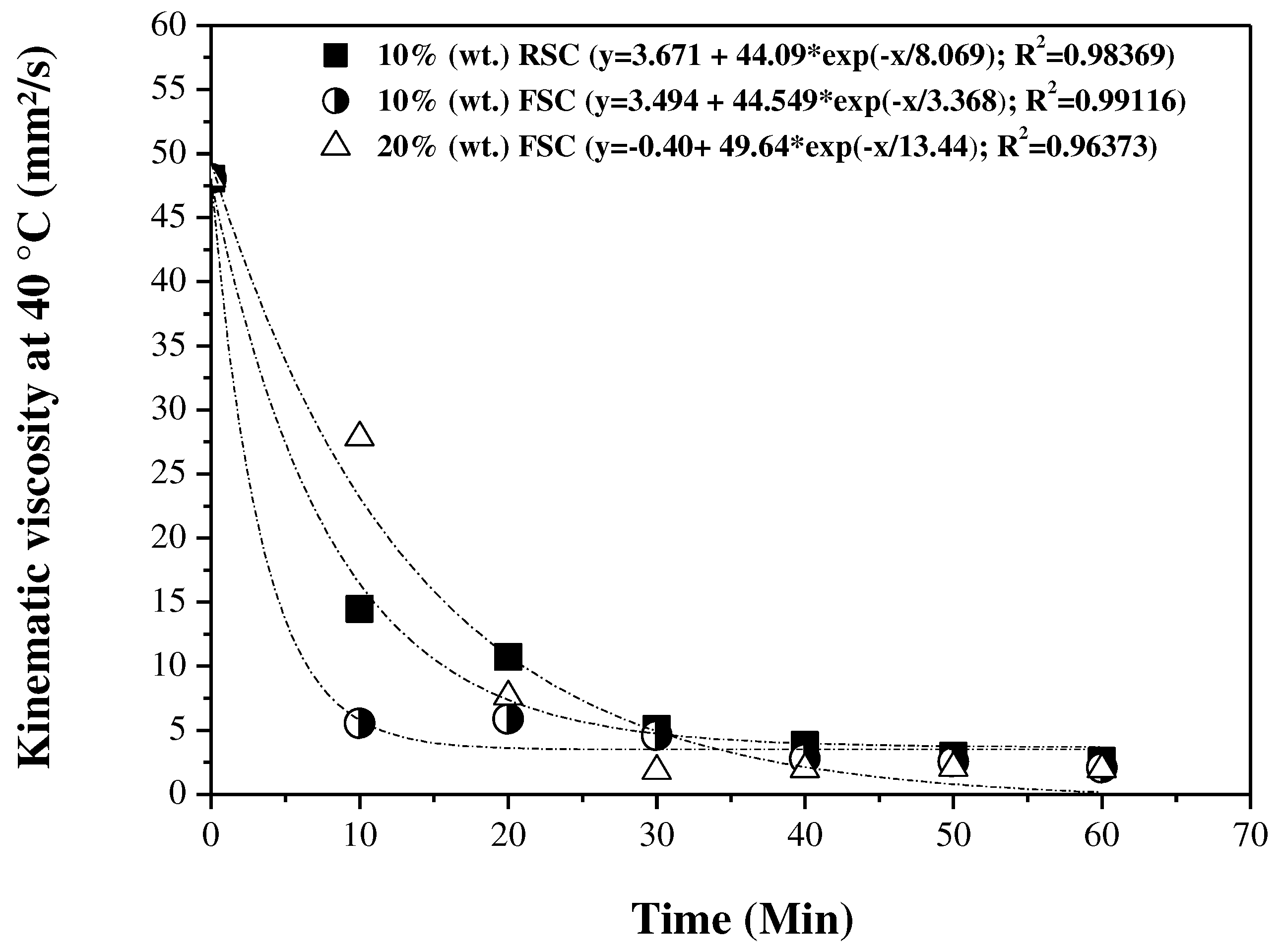

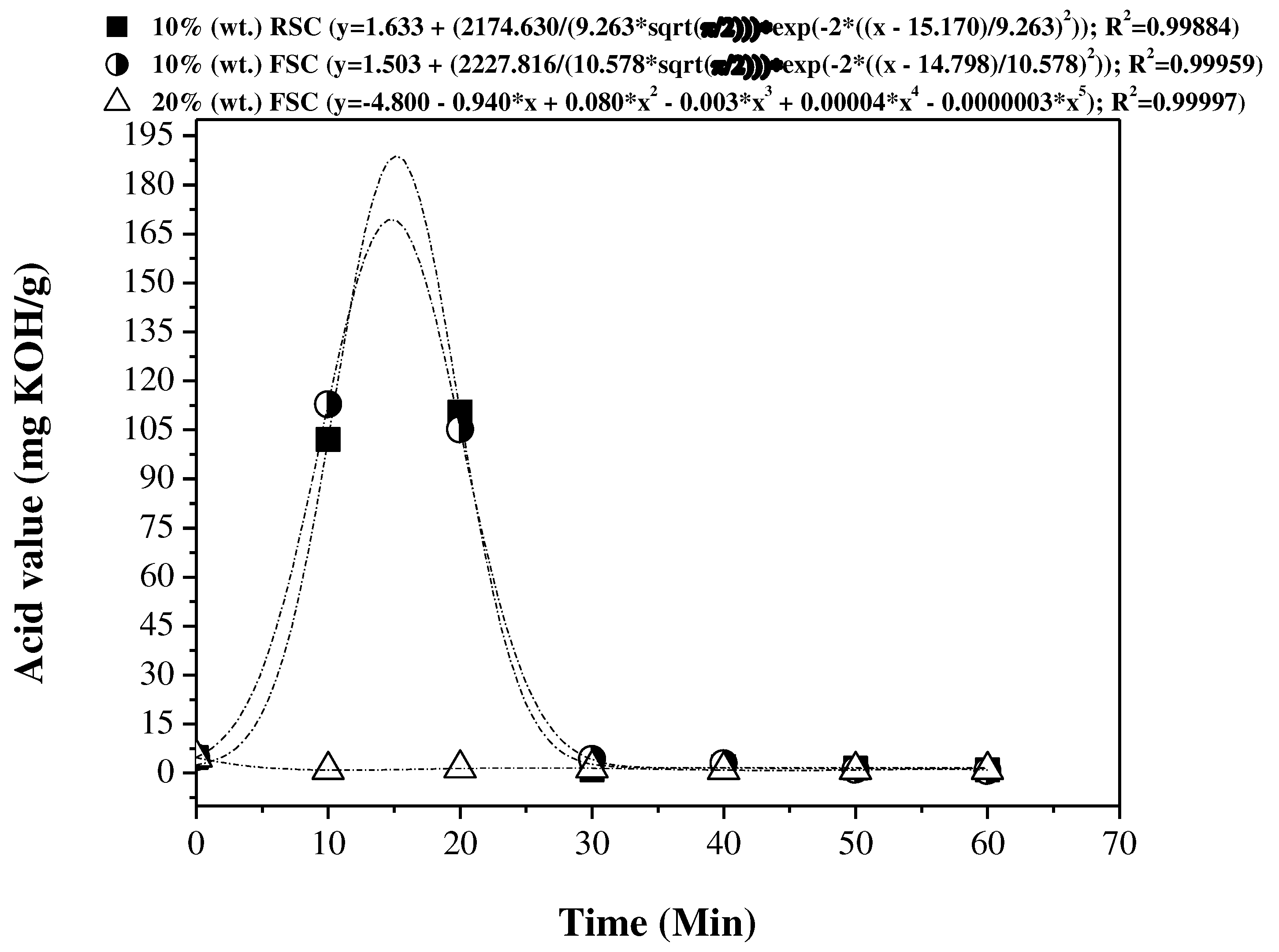

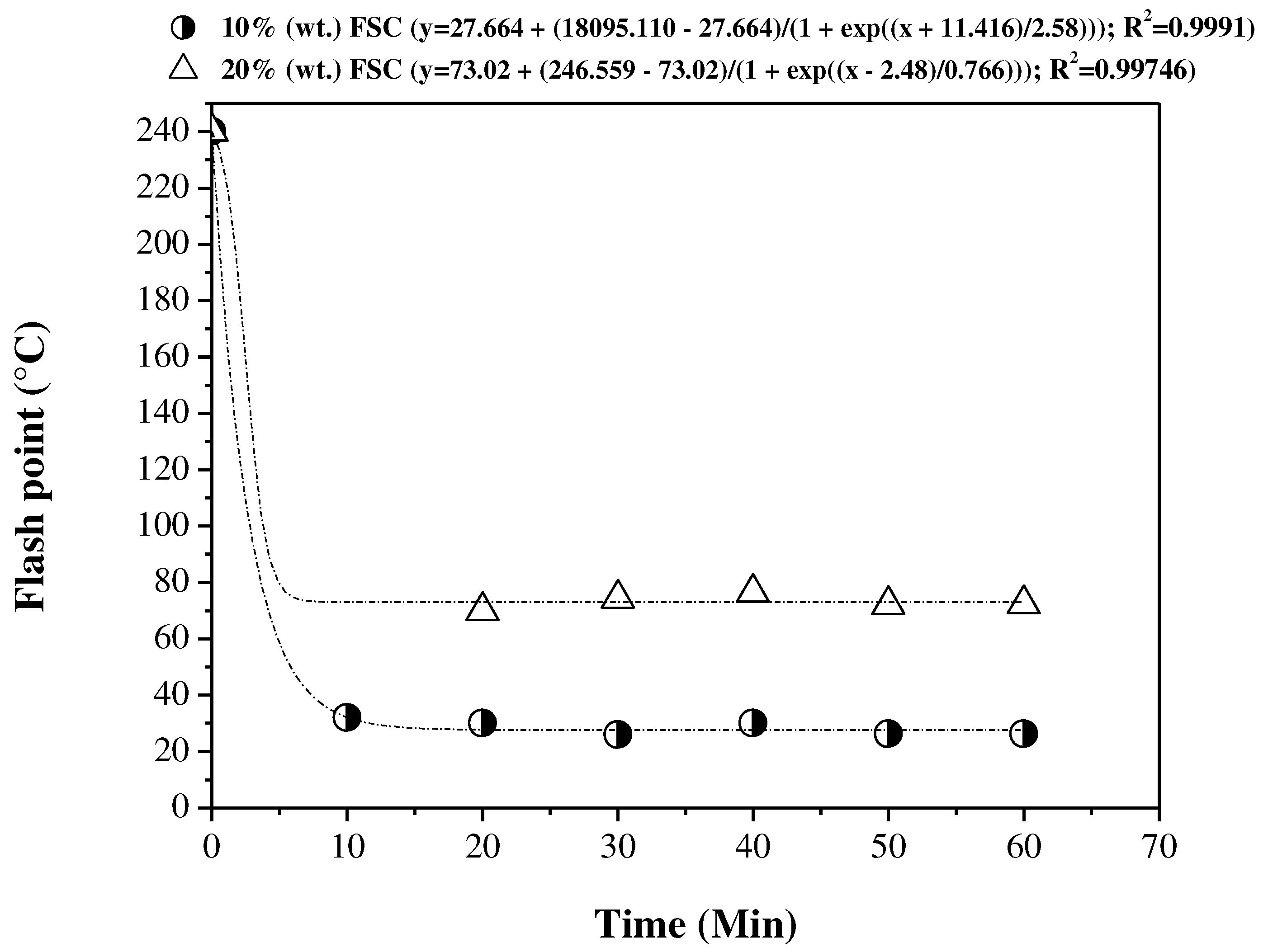

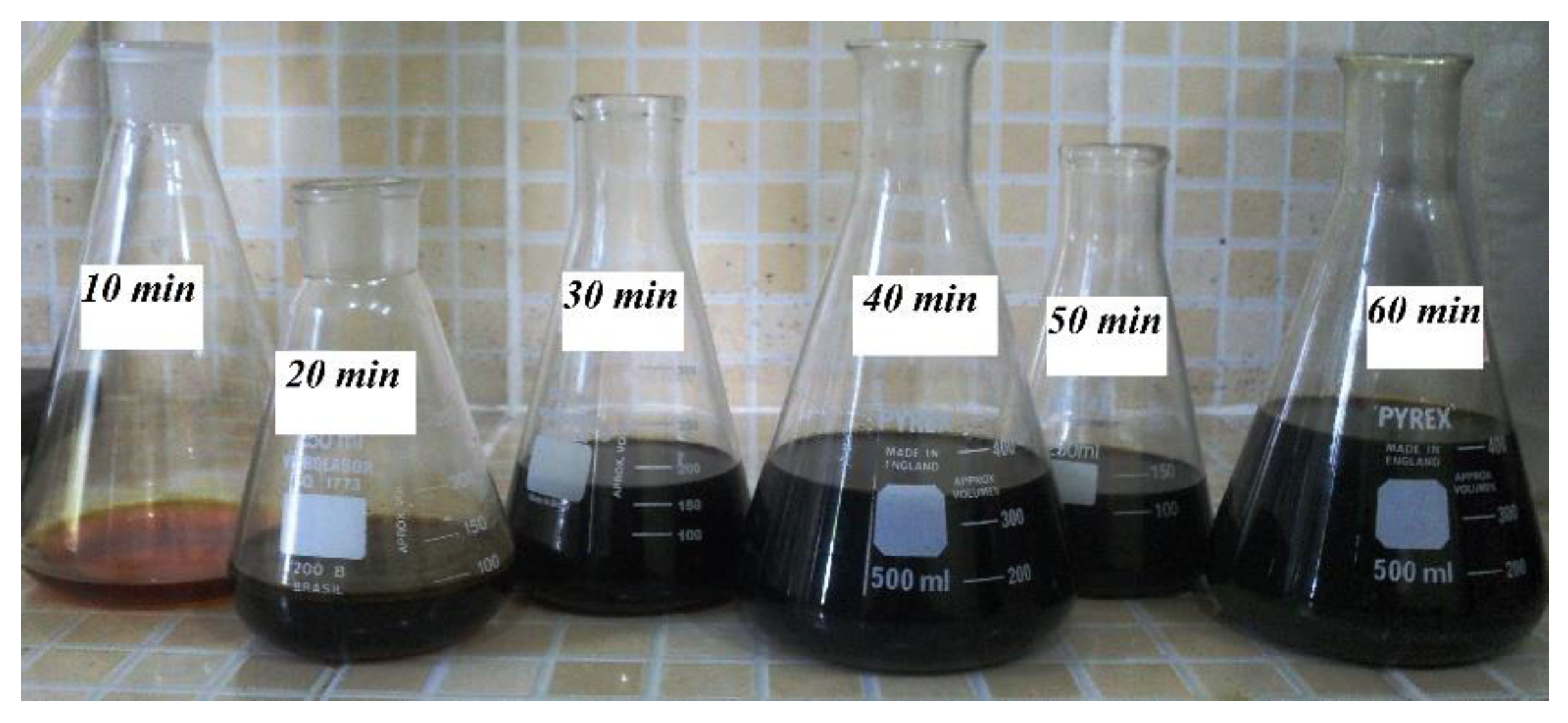

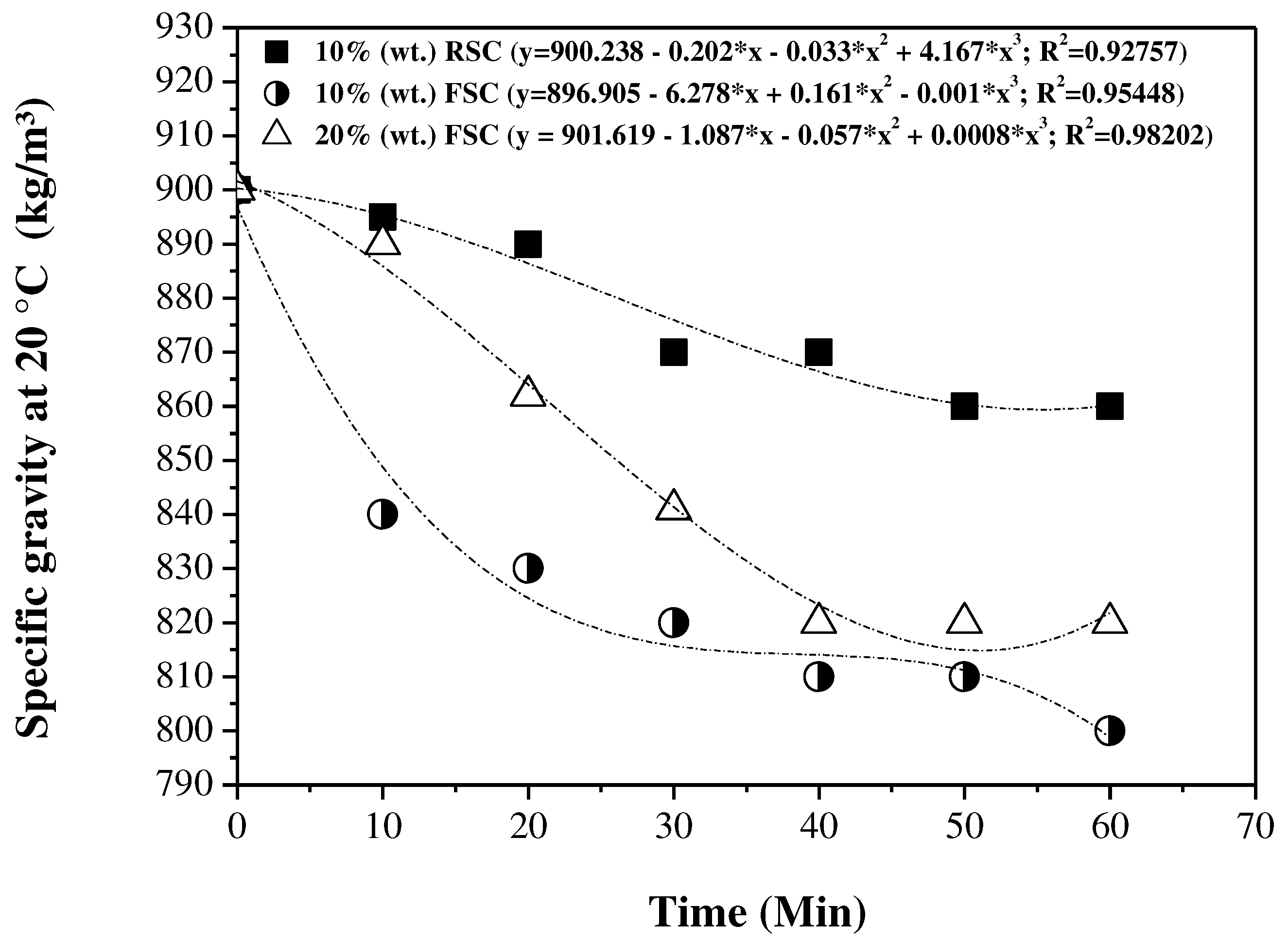

3.5. Influence of reaction time on the physical-chemical properties of the OLP

3.5.1. Physical-chemical properties

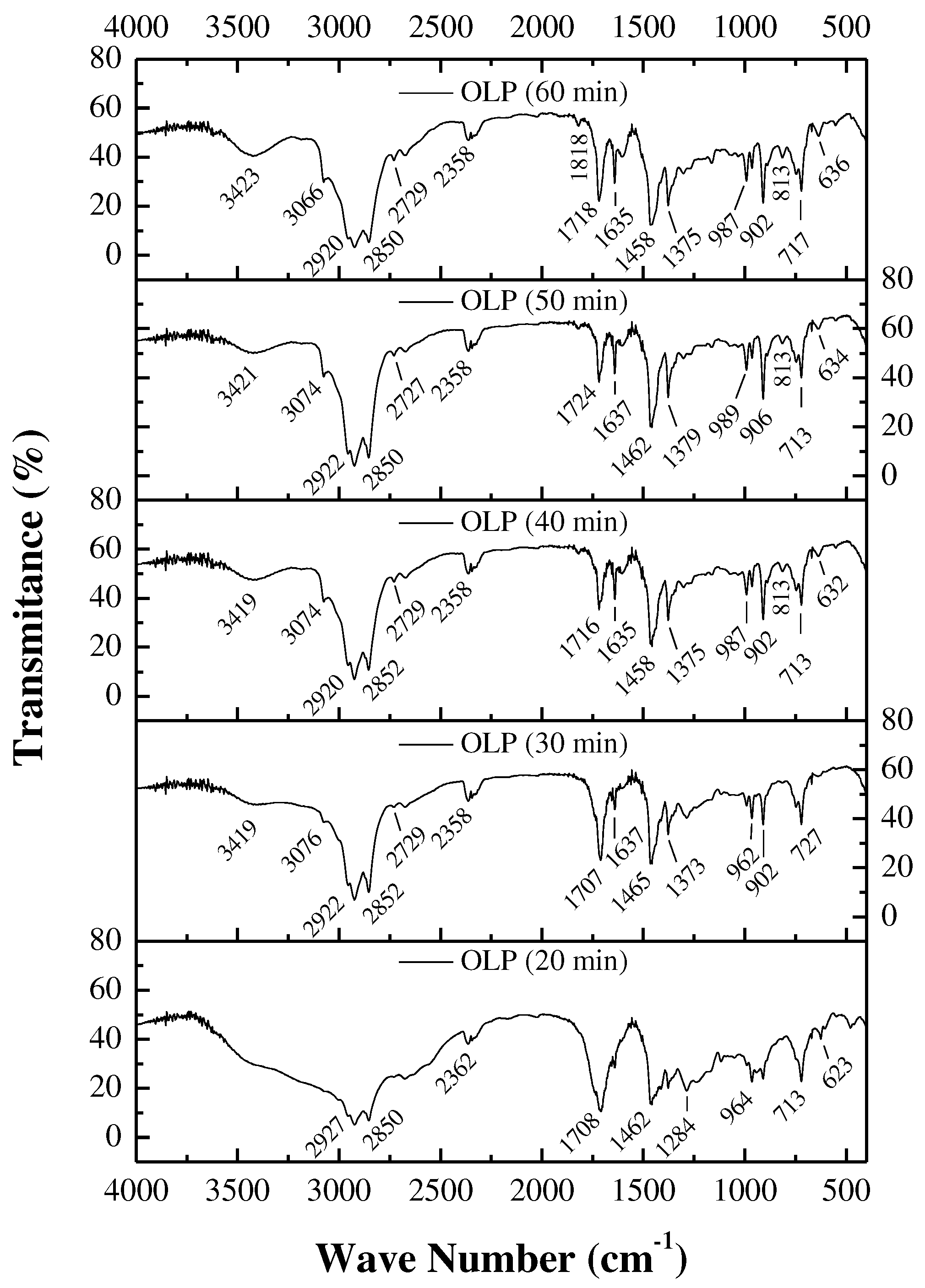

3.5.2. FTIR spectroscopy

3.6. Influence of the fractional distillation process on the yield and quality of biofuels

3.6.1. Mass balances of the distillation process

3.6.2. Characterization of the distilled fractions

3.6.2.1. Physical-chemical properties

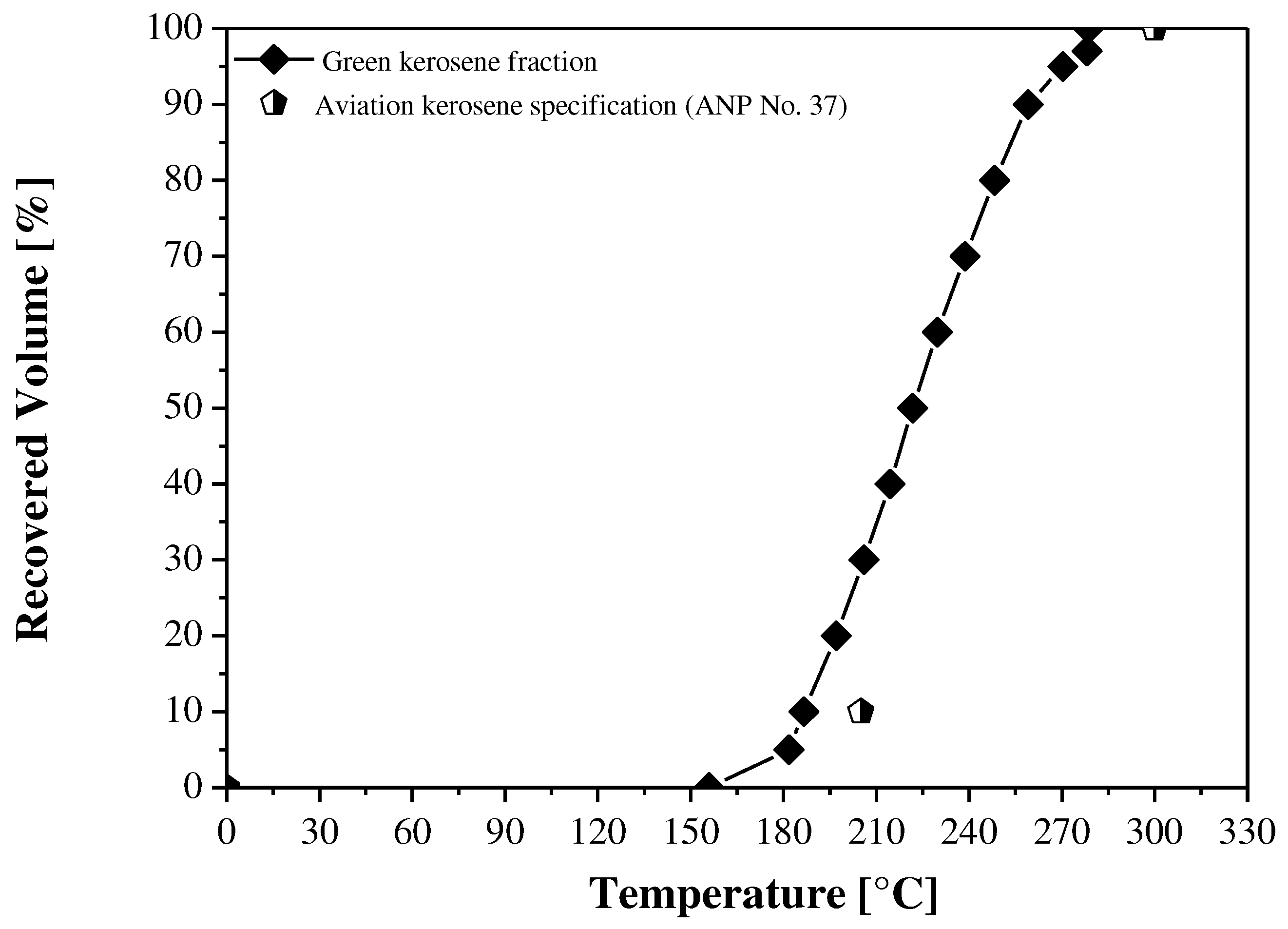

| Physical-chemical properties | Unit | OLP [23] | Green aviation kerosene | ANP Nº 37 (Aviation kerosene) [89] |

ASTM D1655 (Jet A-1) [90] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity at 20 °C | kg/m³ | 790.00 | 790.00 | 771.30-836.60 | 775-840a |

| Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C | mm²/s | 2.02 | 1.48 | - | 8.0b |

| Flash point, min | ºC | 85.10 | 10.00 | 38.00 | 38.00 |

| Corrosiveness to copper, 3h 50 ºC, max. | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1c |

| Carbon residue, max. | wt.% | 0.64 | 0.02 | - | - |

| Acid value | mg KOH/g | 1.02 | 1.68 | 0.015d | 0.10d |

| Saponification value | mg KOH/g | 14.35 | 15.05 | - | - |

| Refractive index | - | 1.44 | 1.44 | - | - |

| Ester value | mg KOH/g | 13.33 | 13.37 | - | - |

| Content of FFA | wt.% | 0.51 | 0.84 | - | - |

| Distillation | |||||

| Initial Boiling Point (I.B.P), | ºC | n.r. | - | Annotate | - |

| 10% vol., recovered, max. | n.r. | 186.60 | 205.00 | 205.00 | |

| 50% vol., recovered | n.r. | 221.80 | Annotate | Annotate | |

| 90% vol., recovered | n.r. | 259.10 | Annotate | Annotate | |

| Final Boiling Point (F.B.P), max. | n.r. | 278.60 | 300.00 | 300.00 | |

| (90% vol., recovered) T90 – (10% vol., recovered) T10, min. | n.r. | 72.5 | - | - | |

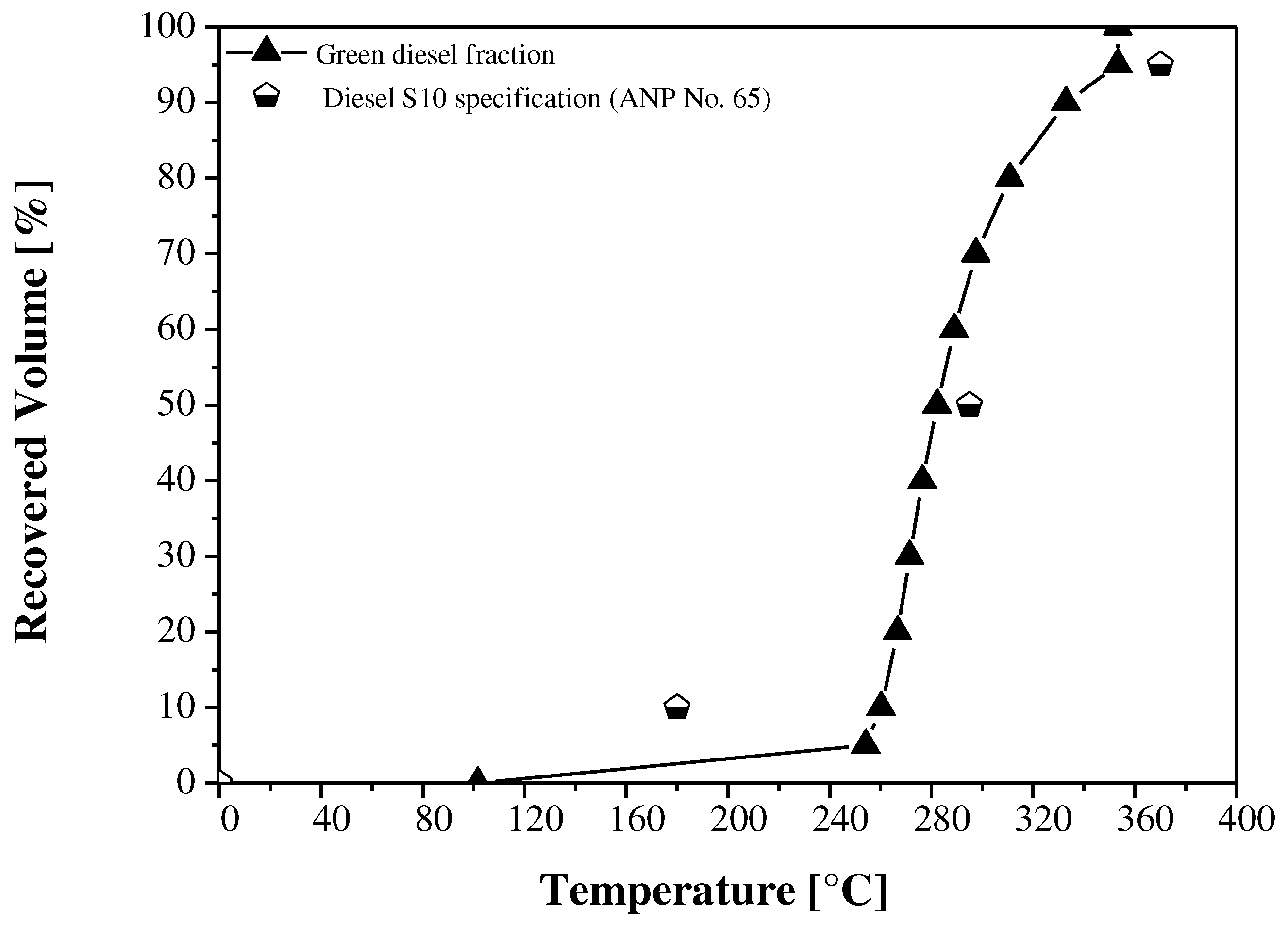

| Physical-chemical properties | Unit | OLP [23] | Green diesel | ANP Nº 65 (Diesel) [73] |

ASTM D975 (Diesel Nº 1-D S15) [79] |

Diesel fraction [19] | Diesel fraction [50] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity at 20 °C | kg/m³ | 790.00 | 820.00 | 820-850 | - | 898 | 881.90 |

| Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C | mm²/s | 2.02 | 3.51 | 2-4.50 | 1.3-2.4 | 6.27a | - |

| Flash point, min | ºC | 85.10 | 24.00 | 38.00 | 38.00 | 115 | - |

| Corrosiveness to copper, 3h 50 °C, max | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | - |

| Carbon residue, max | wt.% | 0.64 | - | 0.25 | 0.15b | - | |

| Acid value | mg KOH/g | 1.02 | 5.70 | 0.50 | - | 2.50 | 86.90 |

| Saponification value | mg KOH/g | 14.35 | 15.80 | - | - | - | - |

| Refractive index | - | 1.44 | 1.45 | - | - | - | - |

| Ester value | mg KOH/g | 13.33 | 10.10 | - | - | - | - |

| Content of FFA | wt.% | 0.51 | 2.87 | - | - | - | - |

| Distillation | |||||||

| 10% vol., recovered | ºC | n.r | 260.20 | 180 | - | - | - |

| 50% vol., recovered | n.r | 282.30 | 245-295 | - | - | - | |

| 85% vol., recovered, max. | n.r | 326.57 | - | - | - | - | |

| 90% vol., recovered, max. | n.r | 332.90 | - | 288.00 | - | - | |

| 95% vol., recovered, max. | n.r | 353.30 | 370 | - | - | - | |

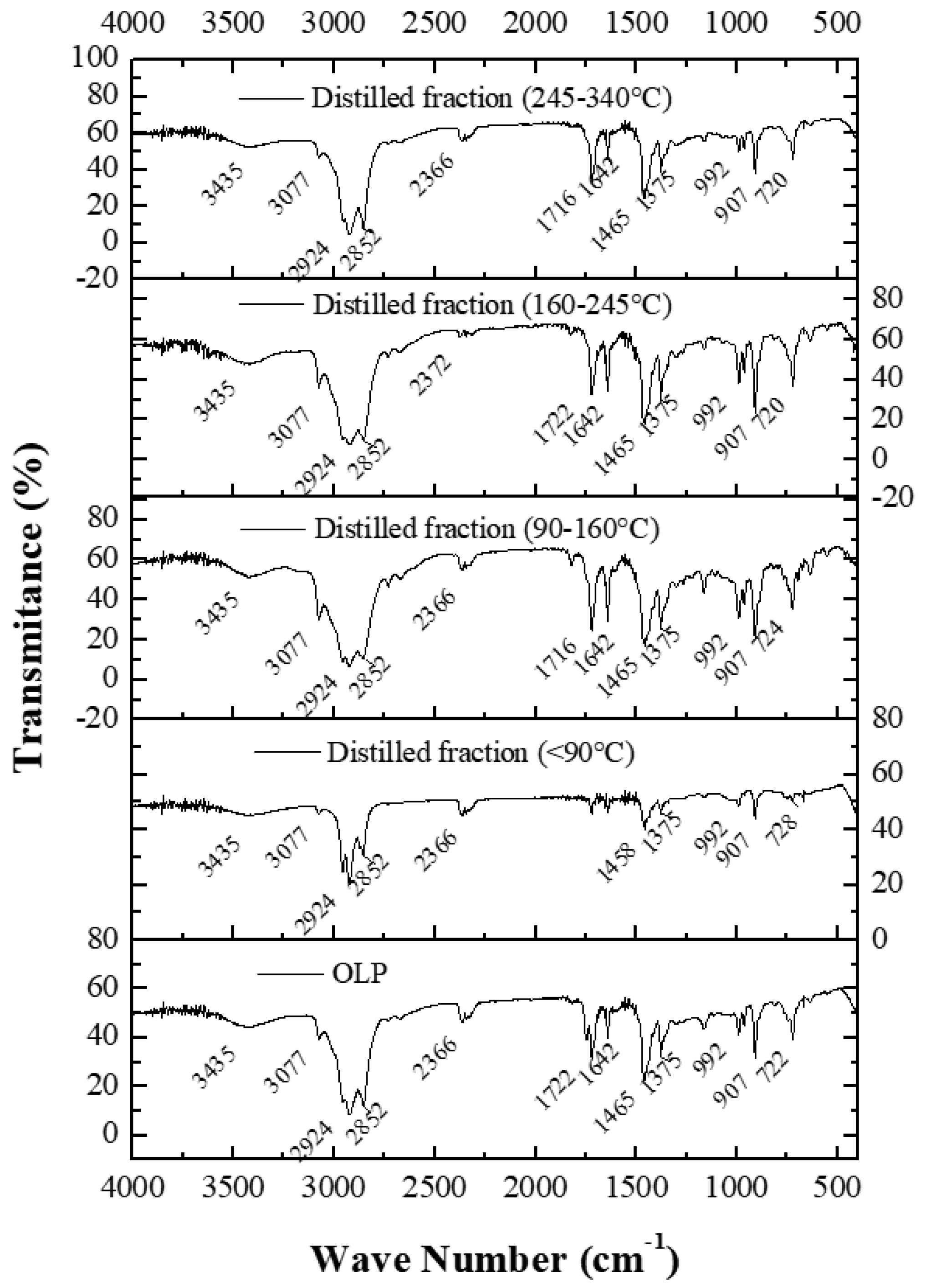

3.6.2.2. FTIR spectroscopy

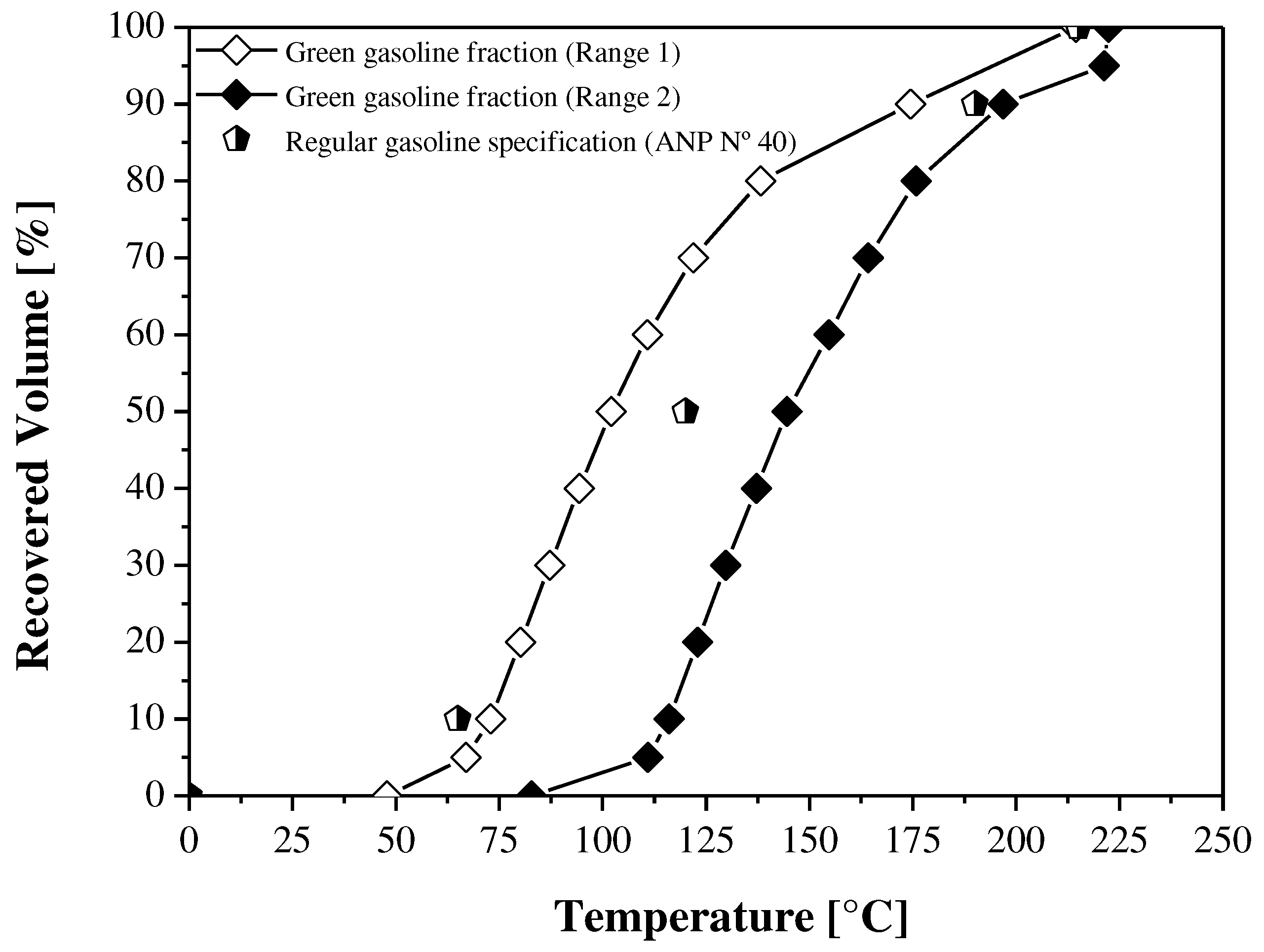

3.6.2.3. Distillation curve

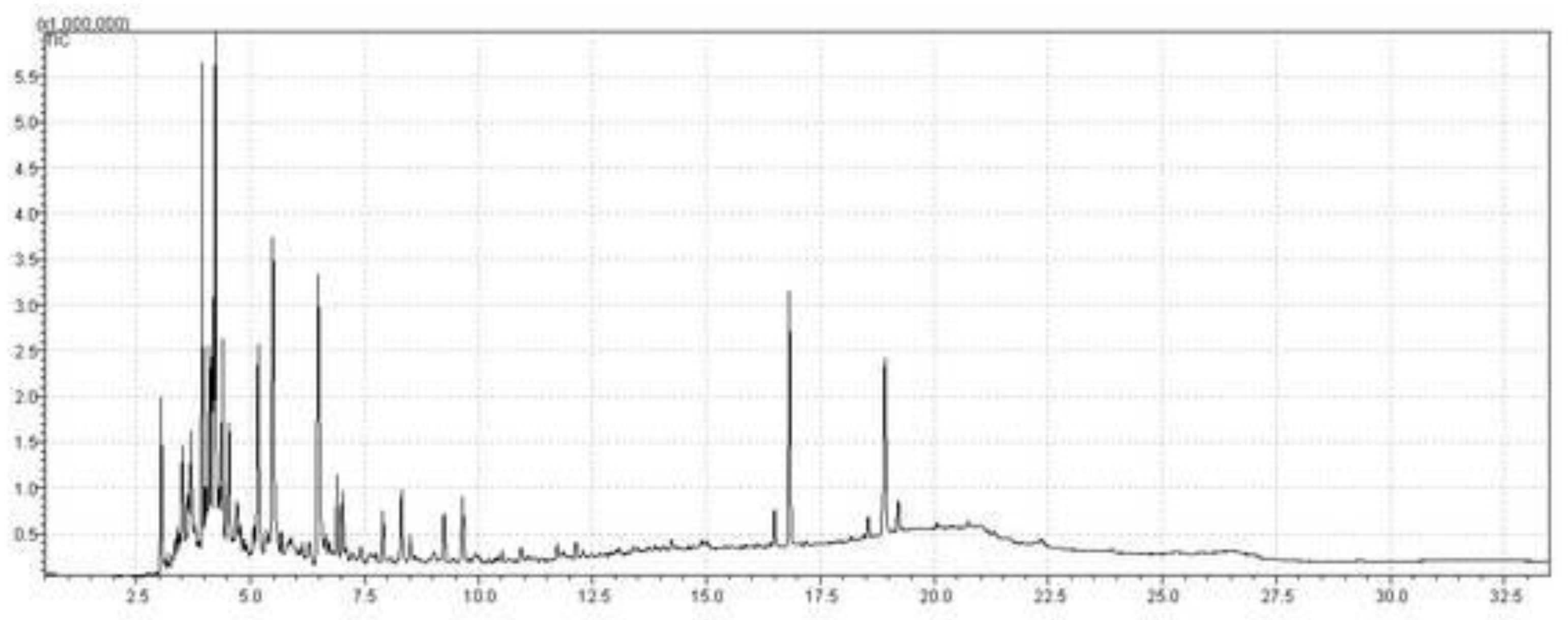

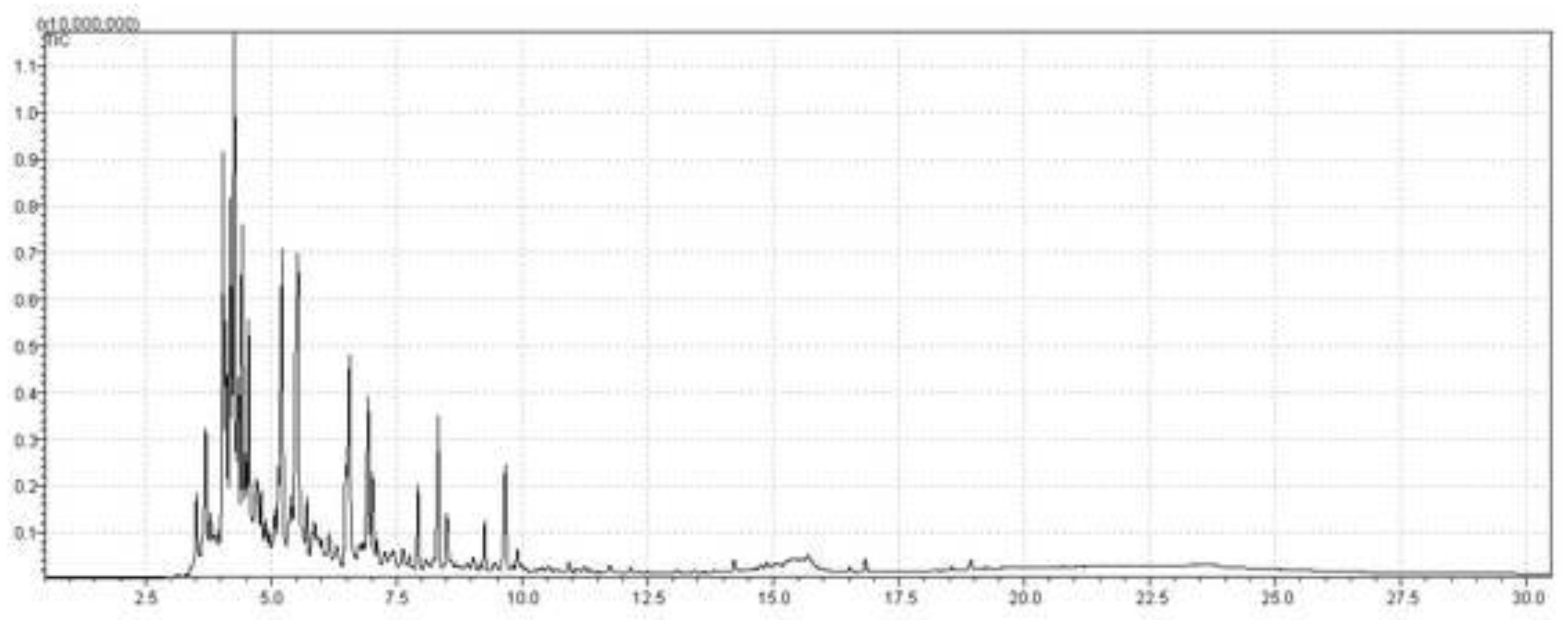

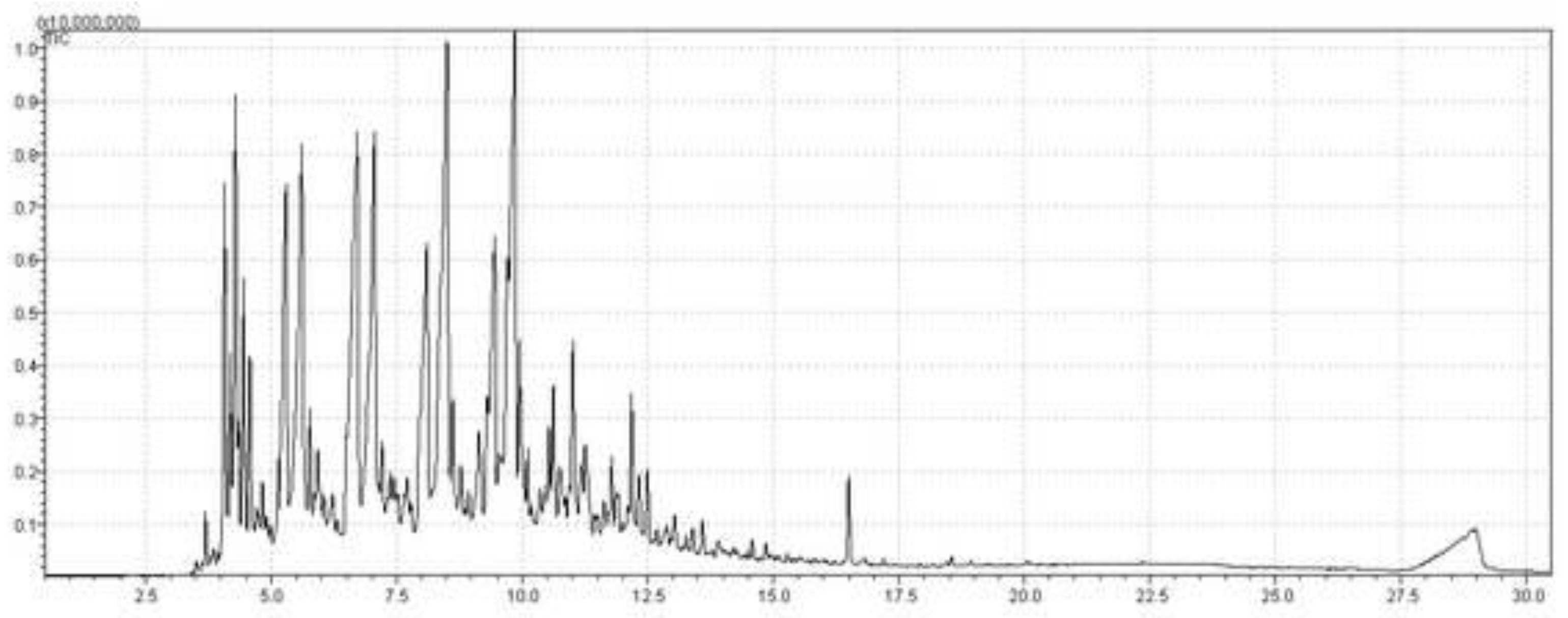

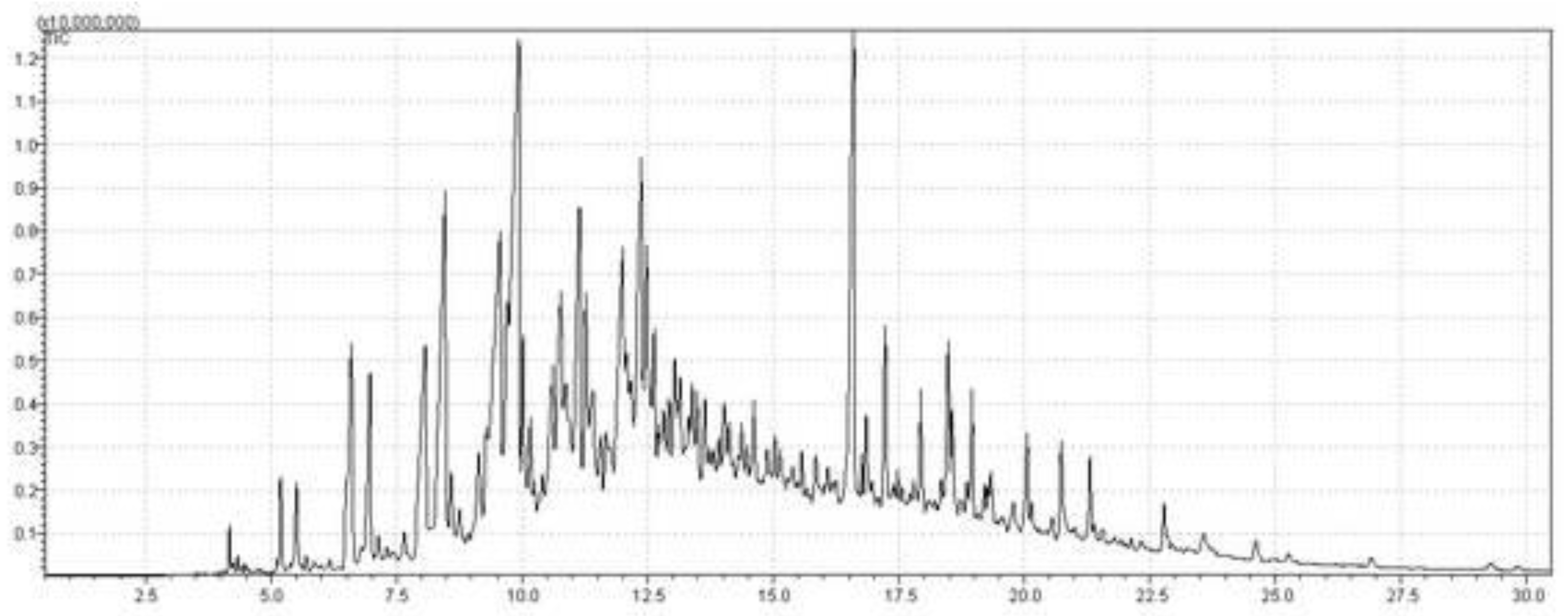

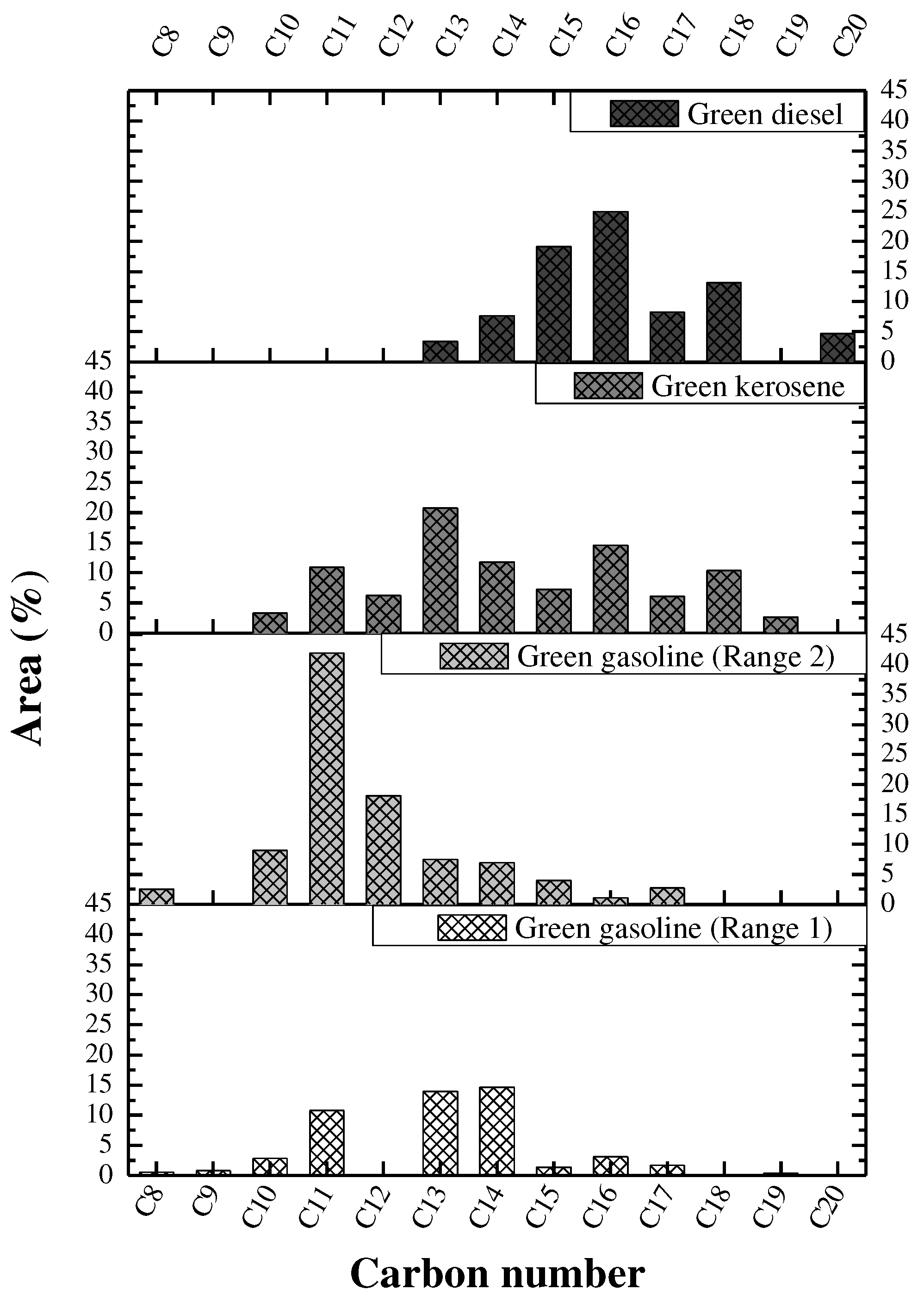

3.6.2.4. GC–MS analysis

| Product Groups | Area (% wt.) | ||||

| OLP [13] | Green gasoline | Green aviation kerosene | Green diesel | ||

| 20% (w/w) Na2CO3 | Range 1 | Range 2 | |||

| Hydrocarbons | 88.10 | 50.14 | 93.64 | 93.97 | 81.25 |

| Normal paraffin | 24.28 | 13.80 | 20.52 | 35.91 | 24.13 |

| Olefins | 51.74 | 32.93 | 45.28 | 53.90 | 55.22 |

| Naphthenic | 12.08 | 3.41 | 25.35 | 4.16 | 1.90 |

| Aromatics | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Oxygenates | 11.90 | 49.86 | 6.36 | 6.03 | 18.75 |

| Carboxylic acids | 3.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| Alcohols | 3.31 | 7.21 | 0.00 | 3.66 | 5.06 |

| Ketones | 5.49 | 15.13 | 3.95 | 1.26 | 11.59 |

| Esters | 0.00 | 14.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Others | 0.00 | 12.99 | 2.41 | 1.11 | 1.12 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodionova, M. V; Poudyal, R.S.; Tiwari, I.; Voloshin, R.A.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Nam, H.G.; Zayadan, B.K.; Bruce, B.D.; Hou, H.J.M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Biofuel Production: Challenges and Opportunities. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 8450–8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, W.E. Global Transport Scenarios 2050, London, 2011.

- Industry Market trends. The damage done in transportation – which energy source will lead to the greenest highways? April 30, 2012, <http://news.thomasnet.com/imt/2012/04/30/the-damage-done-in-transportation-which-energy-source-will-lead-to-the-greenest-highways> [accessed 20.05.2023].

- Popp, J.; Kovács, S.; Oláh, J.; Divéki, Z.; Balázs, E. Bioeconomy: Biomass and Biomass-Based Energy Supply and Demand. N Biotechnol 2021, 60, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naji, S.Z.; Tye, C.T.; Abd, A.A. State of the Art of Vegetable Oil Transformation into Biofuels Using Catalytic Cracking Technology: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Process Biochemistry 2021, 109, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, H.; Sadrameli, S.M. Improvement of Renewable Transportation Fuel Properties by Deoxygenation Process Using Thermal and Catalytic Cracking of Triglycerides and Their Methyl Esters. Appl Therm Eng 2016, 100, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.F.; Wiggers, V.R.; Zonta, G.R.; Scharf, D.R.; Simionatto, E.L.; Ender, L. A Kinetic Model for Thermal Cracking of Waste Cooking Oil Based on Chemical Lumps. Fuel 2015, 144, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iha, O.K.; Alves, F.; Suarez, P.A.Z.; Silva, C.R.P.; Meneghetti, M.R.; Meneghetti, S.M.P. Potential Application of Terminalia Catappa L. and Carapa Guianensis Oils for Biofuel Production: Physical-Chemical Properties of Neat Vegetable Oils, Their Methyl-Esters and Bio-Oils (Hydrocarbons). Ind Crops Prod 2014, 52, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, V.R.; Zonta, G.R.; Franca, A.P.; Scharf, D.R.; Simionatto, E.L.; Ender, L.; Meier, H.F. Challenges Associated with Choosing Operational Conditions for Triglyceride Thermal Cracking Aiming to Improve Biofuel Quality. Fuel 2013, 107, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozliak, E.; Mota, R.; Rodriguez, D.; Overby, P.; Kubatova, A.; Stahl, D.; Niri, V.; Ogden, G.; Seames, W. Non-Catalytic Cracking of Jojoba Oil to Produce Fuel and Chemical by-Products. Ind Crops Prod 2013, 43, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Gao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Ji, J. Bio-Fuel Production from the Catalytic Pyrolysis of Soybean Oil over Me-Al-MCM-41 (Me=La, Ni or Fe) Mesoporous Materials. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2013, 104, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.M.; Fréty, R.; Barbosa, C.B.M.; Santos, M.R.; Bruce, E.D.; Pacheco, J.G.A. Mo Influence on the Kinetics of Jatropha Oil Cracking over Mo/HZSM-5 Catalysts. Catal Today 2017, 279 Part, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancio, A.A.; da Costa, K.M.B.; Ferreira, C.C.; Santos, M.C.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; da Mota, S.A.P.; Leão, R.A.C.; de Souza, R.O.M.A.; Araújo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil at Pilot Scale: Effect of the Percentage of Na2CO3 on the Quality of Biofuels. Ind Crops Prod 2016, 91, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Almeida, H.; Corrêa, O.A.; Eid, J.G.; Ribeiro, H.J.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Pereira, M.S.; Pereira, L.M.; de Andrade Mâncio, A.; Santos, M.C.; da Silva Souza, J.A.; et al. Production of Biofuels by Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Scum from Grease Traps in Pilot Scale. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2016, 118, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasov, V.; Mammadova, T.; Aliyeva, N.; Abbasov, M.; Movsumov, N.; Joshi, A.; Lvov, Y.; Abdullayev, E. Catalytic Cracking of Vegetable Oils and Vacuum Gasoil with Commercial High Alumina Zeolite and Halloysite Nanotubes for Biofuel Production. Fuel 2016, 181, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovás, P.; Hudec, P.; Hadvinová, M.; Ház, A. Conversion of Rapeseed Oil via Catalytic Cracking: Effect of the ZSM-5 Catalyst on the Deoxygenation Process. Fuel Processing Technology 2015, 134, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.H.; Wei, L.; Cheng, S.Y.; Cao, Y.H.; Julson, J.; Gu, Z.R. Catalytic Cracking of Carinata Oil for Hydrocarbon Biofuel over Fresh and Regenerated Zn/Na-ZSM-5. Applied Catalysis a-General 2015, 507, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Sharma, D.K. Effect of Different Catalysts on the Cracking of Jatropha Oil. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2014, 110, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.M.; Jiang, J.C.; Zhang, T.J.; Dai, W.D. Biofuel Production from Catalytic Cracking of Triglyceride Materials Followed by an Esterification Reaction in a Scale-up Reactor. Energy & Fuels 2013, 27, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Cai, Q.; Guo, L. Catalytic Conversion of Carboxylic Acids in Bio-Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbons Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 45, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, P.; Jin, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xia, T.; Shao, K.; Wang, T.; Li, Q. Production of Jet Fuel Range Biofuels by Catalytic Transformation of Triglycerides Based Oils. Fuel 2017, 188, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Quan, K.; Xu, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Yu, S.; Xie, C.; Zhang, B.; Ge, X. Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels from Catalytic Cracking of Waste Cooking Oils Using Basic Mesoporous Molecular Sieves K2O/Ba-MCM-41 as Catalysts. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2013, 1, 1412–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mota, S.A.P.; Mancio, A.A.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; de Abreu, D.H.; da Silva, M.S.; dos Santos, W.G.; de Castro, D.A.R.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Ara?jo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Production of Green Diesel by Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil (Elaeis Guineensis Jacq) in a Pilot Plant. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonti, D.; Buffi, M.; Rizzo, A.M.; Lotti, G.; Prussi, M. Bio-Hydrocarbons through Catalytic Pyrolysis of Used Cooking Oils and Fatty Acids for Sustainable Jet and Road Fuel Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.P.; Silva, L.N.; de Rezende, D.B.; de Oliveira, L.C.A.; Pasa, V.M.D. Simultaneous Deoxygenation, Cracking and Isomerization of Palm Kernel Oil and Palm Olein over Beta Zeolite to Produce Biogasoline, Green Diesel and Biojet-Fuel. Fuel 2018, 223, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Freitas, L.N.; de Sousa, F.P.; Rodrigues de Carvalho, A.; Pasa, V.M.D. Study of Direct Synthesis of Bio-Hydrocarbons from Macauba Oils Using Zeolites as Catalysts. Fuel 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, L.; Shitao, Y.; Liu, S.; Hailong, Y.; Qiong, W.; Ragauskas, A.J. Catalytic Conversion of Waste Cooking Oils for the Production of Liquid Hydrocarbon Biofuels Using In-Situ Coating Metal Oxide on SBA-15 as Heterogeneous Catalyst. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2019, 138, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Phuc, N.; Tran, T. V.; Phan, T.T.; Ngo, P.T.; Ha, Q.L.M.; Luong, T.N.; Tran, T.H.; Phan, T.T. High-Efficient Production of Biofuels Using Spent Fluid Catalytic Cracking (FCC) Catalysts and High Acid Value Waste Cooking Oils. Renew Energy 2021, 168, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, G.; Sudhakar, R.; Joice, J.A.I.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Sivakumar, T. Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels from Jatropha Oil through Catalytic Cracking Technology Using AlMCM-41/ZSM-5 Composite Catalysts. Applied Catalysis a-General 2012, 433, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.N.; Tran, Q. V; Nguyen, T.T.L.; Van, D.S.T.; Yang, X.Y.; Su, B.L. Preparation of Bio-Fuels by Catalytic Cracking Reaction of Vegetable Oil Sludge. Fuel 2011, 90, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; DiMaggio, C.; Wang, H.; Mohan, S.; Kim, M.; Yang, L.; O. Salley, S.; Y. Simon Ng, K. Catalytic Conversion of Triglycerides to Liquid Biofuels Through Transesterification, Cracking, and Hydrotreatment Processes. Current Catalysis 2012, 1, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Melero, J.A.; García, A.; Clavero, M. Production of Biofuels via Catalytic Cracking. In Handbook of Biofuels Production; Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp. 390–419 ISBN 978-1-84569-679-5.

- Mâncio, A.A.; da Costa, K.M.B.; Ferreira, C.C.; Santos, M.C.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; da Mota, S.A.P.; Leão, R.A.C.; de Souza, R.O.M.A.; Araújo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Process Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Chemical Composition of Organic Liquid Products Obtained by Thermochemical Conversion of Palm Oil. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedile, T.; Ender, L.; Meier, H.F.; Simionatto, E.L.; Wiggers, V.R. Comparison between Physical Properties and Chemical Composition of Bio-Oils Derived from Lignocellulose and Triglyceride Sources. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.E.; Luna, A.S.; Torres, A.R. Operating Parameters for Bio-Oil Production in Biomass Pyrolysis: A Review. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2018, 129, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. High-Efficiency Separation of Bio-Oil. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, K.D.; Bressler, D.C. Pyrolysis of Triglyceride Materials for the Production of Renewable Fuels and Chemicals. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98, 2351–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzetzki, E.; Sidorová, K.; Cvengrošová, Z.; Cvengroš, J. Effects of Oil Type on Products Obtained by Cracking of Oils and Fats. Fuel Processing Technology 2011, 92, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzetzki, E.; Sidorová, K.; Cvengrošová, Z.; Kaszonyi, A.; Cvengroš, J. The Influence of Zeolite Catalysts on the Products of Rapeseed Oil Cracking. Fuel Processing Technology 2011, 92, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, V.R.; Wisniewski, A.; Madureira, L.A.S.; Barros, A.A.C.; Meier, H.F. Biofuels from Waste Fish Oil Pyrolysis: Continuous Production in a Pilot Plant. Fuel 2009, 88, 2135–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junming, X.; Jianchun, J.; Yanju, L.; Jie, C. Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels Obtained by the Pyrolysis of Soybean Oils. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 4867–4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.; Stadlbauer, E.A.; Stengl, S.; Hossain, M.; Frank, A.; Steffens, D.; Schlich, E.; Schilling, G. Production of Hydrocarbons from Fatty Acids and Animal Fat in the Presence of Water and Sodium Carbonate: Reactor Performance and Fuel Properties. Fuel 2012, 94, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecha, A.C.; Onyango, M.S.; Ochieng, A.; Momba, M.N.B. Ultraviolet and Solar Photocatalytic Ozonation of Municipal Wastewater: Catalyst Reuse, Energy Requirements and Toxicity Assessment. Chemosphere 2017, 186, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmiaton, A.; Garforth, A.A. Multiple Use of Waste Catalysts with and without Regeneration for Waste Polymer Cracking. Waste Management 2011, 31, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayatno, W.B.; Guan, G.; Rizkiana, J.; Yang, J.; Hao, X.; Tsutsumi, A.; Abudula, A. Upgrading of Bio-Oil from Biomass Pyrolysis over Cu-Modified β-Zeolite Catalyst with High Selectivity and Stability. Appl Catal B 2016, 186, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, S.N.; Shahbazi, A. Bio-Oil Production and Upgrading Research: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4406–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capunitan, J.A.; Capareda, S.C. Characterization and Separation of Corn Stover Bio-Oil by Fractional Distillation. Fuel 2013, 112, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Choi, J.; Capareda, S.C. Comparative Study of Vacuum and Fractional Distillation Using Pyrolytic Microalgae (Nannochloropsis Oculata) Bio-Oil. Algal Res 2016, 17, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegade, S.; Tande, B.; Kubatova, A.; Seames, W.; Kozliak, E. Novel Two-Step Process for the Production of Renewable Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Triacylglycerides. Ind Eng Chem Res 2015, 54, 9657–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, A.; Wosniak, L.; Scharf, D.R.; Wiggers, V.R.; Meier, H.F.; Simionatto, E.L. Upgrade of Biofuels Obtained from Waste Fish Oil Pyrolysis by Reactive Distillation. J Braz Chem Soc 2015, 26, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Almeida, H.; Corrêa, O.A.; Eid, J.G.; Ribeiro, H.J.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Pereira, M.S.; Pereira, L.M.; de Andrade Aâncio, A.; Santos, M.C.; da Mota, S.A.P.; et al. Performance of Thermochemical Conversion of Fat, Oils, and Grease into Kerosene-like Hydrocarbons in Different Production Scales. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2016, 120, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancio, A.A.; da Mota, S.A.P.; Ferreira, C.C.; Carvalho, T.U.S.; Neto, O.S.; Zamian, J.R.; Araújo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; Machado, N.T. Separation and Characterization of Biofuels in the Jet Fuel and Diesel Fuel Ranges by Fractional Distillation of Organic Liquid Products. Fuel 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.C.; Costa, E.C.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Pereira, M.S.; Mâncio, A.A.; Santos, M.C.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; da Mota, S.A.P.; Leão, A.C.; Duvoisin, S.; et al. Deacidification of Organic Liquid Products by Fractional Distillation in Laboratory and Pilot Scales. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2017, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varuvel, E.G.; Mrad, N.; Tazerout, M.; Aloui, F. Assessment of Liquid Fuel (Bio-Oil) Production from Waste Fish Fat and Utilization in Diesel Engine. Appl Energy 2012, 100, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Sun, M.; Wang, C.; Zhu, X. Full Temperature Range Study of Rice Husk Bio-Oil Distillation: Distillation Characteristics and Product Distribution. Sep Purif Technol 2021, 263, 118382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.K.; Yuan, X.H.; Luo, Z.J.; Zhu, X.F. Influence of Vacuum Degrees in Rectification System on Distillation Characteristics of Bio-Oil Model Compounds. Ranliao Huaxue Xuebao/Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology 2022, 50, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suota, M.J.; Simionatto, E.L.; Scharf, D.R.; Meier, H.F.; Wiggers, V.R. Esterification, Distillation, and Chemical Characterization of Bio-Oil and Its Fractions. Energy and Fuels 2019, 33, 9886–9894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkasabi, Y.; Mullen, C.A.; Boateng, A.A.; Brown, A.; Timko, M.T. Flash Distillation of Bio-Oils for Simultaneous Production of Hydrocarbons and Green Coke. Ind Eng Chem Res 2019, 58, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, B.F.H.; De França, L.F.; Corrêa, N.C.F.; Da Paixão Ribeiro, N.F.; Velasquez, M. Renewable Diesel Production from Palm Fatty Acids Distillate (Pfad) via Deoxygenation Reactions. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha de Castro, D.A.; da Silva Ribeiro, H.J.; Hamoy Guerreiro, L.H.; Pinto Bernar, L.; Jonatan Bremer, S.; Costa Santo, M.; da Silva Almeida, H.; Duvoisin, S.; Pizarro Borges, L.E.; Teixeira Machado, N. Production of Fuel-like Fractions by Fractional Distillation of Bio-Oil from Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seeds Pyrolysis. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.S.; Yang, G.X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, W.J.; Ding, H.S. Mass Production of Chemicals from Biomass-Derived Oil by Directly Atmospheric Distillation Coupled with Co-Pyrolysis. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhamas, D.E.L. Estudo Do Processo de Craqueamento Termocatalítico Do Óleo de Palma (Elaeis Guineensis) e Do Óleo de Buriti (Mauritia Flexuosa L.) Para Produção de Biocombustível, Belém-PA, 2013, Vol. Tese de do.

- Paquot, C. 2.203 - Determination of the Ester Value (E.V.). In Standard Methods for the Analysis of Oils, Fats and Derivatives (Sixth Edition); Pergamon, 1979; p. 60 ISBN 978-0-08-022379-7.

- Reddy, V.; Rao, H.; Jayaveera, K. Influence of Strong Alkaline Substances (Sodium Carbonate and Sodium Bicarbonate) in Mixing Water on Strength and Setting Properties of Concrete. Indian Journal Of Engineering And Materials Sciences 2006, 13, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Taufiqurrahmi, N.; Bhatia, S. Catalytic Cracking of Edible and Non-Edible Oils for the Production of Biofuels. Energy Environ Sci 2011, 4, 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonghia, E.; Boocock, D.G.B.; Konar, S.K.; Leung, A. Pathways for the Deoxygenation of Triglycerides to Aliphatic Hydrocarbons over Activated Alumina. Energy & Fuels 1995, 9, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikaneni, S.P.R.; Adjaye, J.D.; Bakhshi, N.N. Studies on the Catalytic Conversion of Canola Oil to Hydrocarbons - Influence of Hybrid Catalysts and Steam. Energy & Fuels 1995, 9, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idem, R.O.; Katikaneni, S.P.R.; Bakhshi, N.N. Thermal Cracking of Canola Oil: Reaction Products in the Presence and Absence of Steam. Energy & Fuels 1996, 10, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, T.Y.; Mohamed, A.R.; Bhatia, S. Catalytic Conversion of Palm Oil to Fuels and Chemicals. Can J Chem Eng 1999, 77, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnjanakom, S.; Guan, G.; Asep, B.; Du, X.; Hao, X.; Yang, J.; Samart, C.; Abudula, A. A Green Method to Increase Yield and Quality of Bio-Oil: Ultrasonic Pretreatment of Biomass and Catalytic Upgrading of Bio-Oil over Metal (Cu, Fe and/or Zn)/γ-Al2O3. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 83494–83503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandik, L.; Aksoy, H.A. Pyrolysis of Used Sunflower Oil in the Presence of Sodium Carbonate by Using Fractionating Pyrolysis Reactor. Fuel Processing Technology 1998, 57, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.R.; Antoniosi Filho, N.R. Production and Characterization of the Biofuels Obtained by Thermal Cracking and Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Vegetable Oils. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2009, 86, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Nacional de Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis − ANP. Resolucão n° 65 de 09 de dezembro de 2011; http://www.anp.org. br (accessed Abril 10, 2020).

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds; 7th Editio.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pavia, D.L.; Lampman, G.M.; Kriz, G.S.; Vyvyan, J.R. Introduction to Spectroscopy; 4th Editio.; Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA - USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yan, Y.; Li, T.; Ren, Z. Upgrading of Liquid Fuel from the Pyrolysis of Biomass. Bioresour Technol 2005, 96, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hew, K.L.; Tamidi, A.M.; Yusup, S.; Lee, K.T.; Ahmad, M.M. Catalytic Cracking of Bio-Oil to Organic Liquid Product (OLP). Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 8855–8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abnisa, F.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Husin, W.N.W.; Sahu, J.N. Utilization Possibilities of Palm Shell as a Source of Biomass Energy in Malaysia by Producing Bio-Oil in Pyrolysis Process. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D975-19a, Standard Specification for Diesel Fuel, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2019, www.astm.org.

- Canapi, E.C.; Agustin, Y.T. V; Moro, E.A.; Pedrosa Jr., E.; Bendaño, M.L.J. Coconut Oil. In Bailey’s Industrial Oil and Fat Products; Shahidi, F., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Swern, D. No Title. In Bailey’s Industrial Oils and Fat Products; Swern, D., Ed.; Interscience Publishers: New York, 1964; pp. 128–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Y.K.; Bhatia, S. The Current Status and Perspectives of Biofuel Production via Catalytic Cracking of Edible and Non-Edible Oils. Energy 2010, 35, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.; Setiawan, A.; Putri, N.A.; Irawan, A.; Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Bindar, Y. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Coconut Oil Soap Using Zeolites for Bio-Hydrocarbon Production. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2021, 6847–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, T.L.; Bhatia, S. Effect of Catalyst Additives on the Production of Biofuels from Palm Oil Cracking in a Transport Riser Reactor. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 2540–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkasabi, Y.; Mullen, C.A.; Jackson, M.A.; Boateng, A.A. Characterization of Fast-Pyrolysis Bio-Oil Distillation Residues and Their Potential Applications. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2015, 114, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkasabi, Y.; Boateng, A.A.; Jackson, M.A. Upgrading of Bio-Oil Distillation Bottoms into Biorenewable Calcined Coke. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 81, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Nacional de Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis − ANP. Resolucão n° 40 de 25 de outubro de 2013; http://www.anp.org. br (accessed Abril 10, 2020).

- ASTM D4814-19a, Standard Specification for Automotive Spark-Ignition Engine Fuel, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2019, www.astm.org.

- Agencia Nacional de Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis − ANP. Resolucão nº 37 de 01 de dezembro de 2009; http://www.anp.org. br (accessed Abril 10, 2020).

- ASTM D1655-19a, Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuels, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2019, www.astm.org.

- Silva, J.P.; Costa, A.L.H.; Chiaro, S.S.X.; Delgado, B.E.P.C.; de Figueiredo, M.A.G.; Senna, L.F. Carboxylic Acid Removal from Model Petroleum Fractions by a Commercial Clay Adsorbent. Fuel Processing Technology 2013, 112, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, J.G. Handbook of Petroleum Product Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fahim, M.A.; Alsahhaf, T.A.; Elkilani, A. Fundamentals of Petroleum Refining; First edit.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780444527851. [Google Scholar]

- Oasmaa, A.; Elliott, D.C.; Korhonen, J. Acidity of Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oils. Energy & Fuels 2010, 24, 6548–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, J.G. Synthetic Fuels Handbook: Properties, Process, and Performance; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggers, V.R.; Meier, H.F.; Wisniewski, A.; Barros, A.A.C.; Maciel, M.R.W. Biofuels from Continuous Fast Pyrolysis of Soybean Oil: A Pilot Plant Study. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 6570–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertas, M.; Alma, M.H. Pyrolysis of Laurel (Laurus Nobilis L.) Extraction Residues in a Fixed-Bed Reactor: Characterization of Bio-Oil and Bio-Char. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2010, 88, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, J.G. The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum; Fourth Edi.; CRC Press: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Majhi, A.; Sharma, Y.K.; Bal, R.; Behera, B.; Kumar, J. Upgrading of Bio-Oils over PdO/Al2O3 Catalyst and Fractionation. Fuel 2013, 107, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process Parameters and mass balance | Catalyst [% wt.] | |

|---|---|---|

| 10 (FSC) | 10 (RSC) | |

| Cracking Temperature [°C] | 450 | 450 |

| Mass of Feed [kg] | 50 | 50 |

| Mass of Catalyst [kg] | 5 | 5 |

| Process Time [min] | 145 | 155 |

| Initial cracking time [min] | 60 | 75 |

| Stirrer Speed [rpm] | 150 | 150 |

| Heating rate (°C) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Conversion [% wt.] | ||

| Mass of OLP (kg) | 31.8 | 29.50 |

| Mass of coke (kg) | 4.00 | 1.86 |

| Mass of gas (kg) | 14.20 | 18.64 |

| Mass of water (kg) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Yield of OLP (% wt.) | 63.60 | 59.00 |

| Yield of coke (% wt.) | 8.00 | 3.72 |

| Yield of gas (% wt.) | 28.40 | 37.28 |

| Yield of water (% wt.) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Physical-chemical Properties | Catalyst [% wt.] | ANP Nº 65 [73] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (FSC) | 10 (RSC) | ||

| Specific gravity at 20°C [g/cm3] | 0.950 | 0.980 | 0.82-0.85 |

| Kinematic viscosity at 40°C [mm2/s] | 2.90 | 4.96 | 2.0-4.5 |

| Corrosiveness to copper, 3h at 50°C | 1A | 1A | 1A |

| Acid value [mg KOH/g] | 8.98 | 39.00 | n.r. |

| Saponification value [mg KOH/g] | 9.19 | 89.46 | n.r. |

| Ester value [mg KOH/g] | 0.21 | 50.46 | n.r. |

| Content of FFA [%] | 4.51 | 19.62 | n.r. |

| Refractive index | 1.45 | 1.45 | n.r. |

| Flash point [°C] | 19.10 | 26.00 | ≥ 38 |

| Carbon residue [%] | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.25 |

| Time (Min) |

Catalyst [% wt.] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (FSC) | 20 (FSC) | 10 (RSC) | ||||

| R.I. | Corrosiveness to Copper, 3h at 50 °C | R.I. | Corrosiveness to Copper, 3h at 50 °C | R.I. | Corrosiveness to Copper, 3h at 50 °C | |

| 0 | 1.45 | 1A | 1.44 | 1A | 1.45 | 1A |

| 10 | 1.46 | n.r. | 1.44 | n.r. | ||

| 20 | 1.42 | 1A | 1.45 | 1A | ||

| 30 | 1.44 | 1A | 1.46 | 1A | ||

| 40 | 1.44 | 1A | 1.45 | 1A | ||

| 50 | 1.45 | 1A | 1.45 | 1A | ||

| 60 | 1.45 | 1A | 1.45 | 1A | ||

| Process Parameters | Unit | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Initial mass of OLP | g | 653.37 |

| Initial operating temperature | °C | 31 |

| Initial distillation temperature | °C | 102 |

| Final distillation temperature | °C | 400 |

| Mass of non-condensable gases | g | 37.17 |

| Mass of green gasoline/Range 1 | g | 31.69 |

| Mass of green gasoline/Range 2 | g | 62.00 |

| Mass of green aviation kerosene | g | 157.85 |

| Mass of green diesel | g | 155.84 |

| Mass of bottoms product | g | 208.82 |

| Yield of non-condensable gases | % wt. | 5.69 |

| Yield of green gasoline/Range 1 | % wt. | 4.85 |

| Yield of green gasoline/Range 2 | % wt. | 9.49 |

| Yield of green aviation kerosene | % wt. | 24.16 |

| Yield of green diesel | % wt. | 23.85 |

| Yield of bottoms product | % wt. | 31.96 |

| Physical-chemical properties | Unit | OLP [23] | Green gasoline | ANP Nº 40 [87] | ASTM D4814 (Gasoline/type A) [88] |

Gasoline fraction [19] | Gasoline fraction [50] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range 1 | Range 2 | ||||||||

| Specific gravity at 20 °C | kg/m³ | 790.00 | 690.00 | 750.00 | Annotate | - | 866.00 | 843.80 | |

| Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C | mm²/s | 2.02 | 0.72 | 0.76 | - | - | 2.34 | - | |

| Flash point, min | ºC | 85.10 | 2.10 | 3.00 | - | - | 34.00 | - | |

| Corrosiveness to copper, 3h 50 °C, max. | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| Carbon residue, max | wt.% | 0.64 | n.r. | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Acid value | mg KOH/g | 1.02 | 1.11 | 1.43 | - | - | 2.30 | 7.60 | |

| Saponification value | mg KOH/g | 14.35 | 12.96 | 14.29 | - | - | - | - | |

| Refractive index | - | 1.44 | 1.40 | 1.42 | - | - | - | - | |

| Ester value | mg KOH/g | 13.33 | 11.85 | 12.86 | - | - | - | - | |

| Content of FFA | wt.% | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.72 | - | - | - | - | |

| Distillation | |||||||||

| 10% vol., recovered, max. | ºC | n.r. | 72.90 | 116.10 | 65.00 | 70.00 | - | - | |

| 50% vol., recovered, max. | n.r. | 102.10 | 144.60 | 120.00 | 121.00 | - | - | ||

| 90% vol., recovered | n.r. | 174.50 | 196.80 | 190.00 | 190.00 | - | - | ||

| Final Boiling Point (F.B.P), max. | n.r. | 214.5 | 222.30 | 215.00 | 225.00 | - | - | ||

| Retention Time (min) |

Molecular formula | Chemical compounds | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.044 | C6H12O | 2-Hexanone | 4.07 |

| 3.183 | C8H12 | 2,5,5-Trimethyl-1,3-cyclopentadiene | 0.54 |

| 3.397 | C9H16 | 1,8-Nonadiene | 0.81 |

| 3.621 | C10H20 | Butylcyclohexane | 2.87 |

| 3.948 | C11H24 | Undecane | 10.79 |

| 4.096 | C7H14O | 2-Heptanone | 7.43 |

| 4.232 | C13H26 | 1-Tridecene | 13.98 |

| 4.342 | C14H26 | 1-Tetradecyne | 3.01 |

| 4.392 | C11H24O | 1-Undecanol | 4.98 |

| 4.525 | C14H28 | (7E)-7-Tetradecene | 4.86 |

| 5.175 | C14H28 | (5E)-5-Tetradecene | 6.31 |

| 5.683 | C14H30 | Tetradecane | 0.45 |

| 6.485 | C6H12O2 | Diacetone alcohol | 12.99 |

| 6.903 | C13H28O | 1-Tridecanol | 2.23 |

| 7.015 | C9H18O | 2-Nonanone | 1.88 |

| 7.909 | C15H32 | Pentadecane | 1.37 |

| 8.311 | C16H32 | (3Z)-3-Hexadecene | 1.90 |

| 8.504 | C10H20O | 2-Decanone | 0.80 |

| 9.249 | C16H34 | Hexadecane | 1.19 |

| 9.657 | C17H34 | 1-Heptadecene | 1.69 |

| 12.142 | C19H38 | 1-Nonadecene | 0.38 |

| 16.5 | C15H30O | 2-Pentadecanone | 0.95 |

| 16.819 | C17H34O2 | Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | 7.27 |

| 18.554 | C16H22O4 | Diisobutyl phthalate | 0.47 |

| 18.917 | C18H34O2 | Ethyl Oleate | 5.97 |

| 19.21 | C20H36O2 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, ethyl ester | 0.82 |

| Retention Time (min) |

Molecular formula | Chemical Compounds | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.511 | C8H10 | Ethylbenzene | 2.49 |

| 4.042 | C10H18 | 9-Methylbicyclo [3.3.1] nonane | 8.98 |

| 4.268 | C11H22 | 1-Undecene | 16.80 |

| 4.422 | C11H22 | 1-Pentyl-2-propylcyclopropane | 15.17 |

| 5.214 | C11H24 | Undecane | 9.93 |

| 5.531 | C12H24 | 1-Dodecene | 15.09 |

| 5.710 | C12H24 | (2Z)-2-Dodecene | 1.86 |

| 5.868 | C12H24 | Nonylcyclopropane | 1.20 |

| 6.484 | C6H12O2 | Diacetone alcohol | 2.41 |

| 6.561 | C13H28 | Tridecane | 7.47 |

| 6.931 | C14H28 | 1-Tetradecene | 4.91 |

| 7.016 | C9H18O | 2-Nonanone | 2.61 |

| 7.923 | C14H30 | Tetradecane | 2.01 |

| 8.326 | C15H30 | 1-Pentadecene | 3.93 |

| 8.496 | C10H20O | 2-Decanone | 1.34 |

| 9.253 | C16H34 | Hexadecane | 1.10 |

| 9.661 | C17H34 | 1-Heptadecene | 2.71 |

| Retention Time (min) |

Molecular formula | Chemical Compounds | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.069 | C10H22 | Decane | 3.34 |

| 4.293 | C11H22 | 1-Undecene | 6.78 |

| 4.448 | C11H22 | 1-Pentyl-2-propylcyclopropane | 4.15 |

| 5.292 | C12H26 | Dodecane | 6.26 |

| 5.610 | C13H26 | 1-Tridecene | 9.42 |

| 5.924 | C12H26O | 1-Dodecanol | 1.10 |

| 6.492 | C6H12O2 | Diacetone alcohol | 1.11 |

| 6.713 | C13H28 | Tridecane | 11.30 |

| 7.057 | C14H28 | 1-Tetradecene | 10.53 |

| 7.206 | C14H28 | (7E)-7-Tetradecene | 1.26 |

| 7.958 | C15H32 | Pentadecane | 7.23 |

| 8.503 | C16H32 | 1-Hexadecene | 14.58 |

| 9.300 | C17H36 | Heptadecane | 6.08 |

| 9.855 | C18H36 | (3E)-3-Octadecene | 9.10 |

| 10.622 | C18H38 | Octadecane | 1.26 |

| 11.012 | C19H38 | 1-Nonadecene | 2.22 |

| 11.186 | C14H28O | (Z)-9-Tetradecen-1-ol | 1.03 |

| 11.780 | C19H40 | Nonadecane | 0.44 |

| 12.180 | C16H34O | 1-Hexadecanol | 0.97 |

| 12.319 | C18H36O | Oleyl Alcohol | 0.56 |

| 12.495 | C13H26O | 2-Tridecanone | 0.57 |

| 16.501 | C15H30O | 2-Pentadecanone | 0.69 |

| Retention Time (min) |

Molecular formula | Chemical Compounds | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.483 | C6H12O2 | Diacetone alcohol | 1.12 |

| 6.599 | C13H28 | Tridecane | 3.40 |

| 6.964 | C14H28 | 1-Tetradecene | 2.39 |

| 8.067 | C14H30 | Tetradecane | 5.29 |

| 8.461 | C15H30 | 1-Pentadecene | 7.91 |

| 9.562 | C15H32 | Pentadecane | 11.23 |

| 9.926 | C16H32 | 1-Hexadecene | 18.81 |

| 10.014 | C16H34O | 1-Hexadecanol | 2.25 |

| 10.606 | C16H32 | Decylcyclohexane | 1.90 |

| 10.776 | C16H34 | Hexadecane | 4.21 |

| 11.138 | C17H34 | 1-Heptadecene | 6.13 |

| 11.265 | C17H36O | 1-Heptadecanol | 2.81 |

| 11.408 | C17H36 | Heptadecane | 2.11 |

| 11.998 | C18H34 | 1-Octadecyne | 5.78 |

| 12.371 | C18H36 | 1-Octadecene | 7.38 |

| 12.478 | C20H38 | 1,19-Eicosadiene | 4.71 |

| 16.598 | C17H34O | 2-Heptadecanone | 7.88 |

| 17.229 | C18H36O | 4-Octadecanone | 1.83 |

| 18.48 | C19H38O | 2-Nonadecanone | 1.88 |

| 20.74 | C15H30O2 | Pentadecanoic acid | 0.98 |

| Distillation | Feed | Temperature | Pressure | Distilled fraction |

Hydrocarbons (% area) |

Oxygenates (% area) |

References |

| Fractional distillation | OLP of Palm oil | <90 °C | 1 atm | Green gasoline (Range 1) | 56.02 | 43.98 | This study |

| Fractional distillation | OLP of Palm oil | 90-160 °C | 1 atm | Green gasoline (Range 2) | 86.37 | 13.63 | This study |

| Fractional distillation | OLP of Palm oil | 160-245 °C | 1 atm | Green aviation kerosene | 91.38 | 8.62 | This study |

| Fractional distillation | OLP of Palm oil | 245-340 °C | 1 atm | Green diesel | 70.78 | 29.22 | This study |

| Reactive distillation | Bio-oil | <200 °C | 1 atm | Light bio-oil | 60.06 | 1.88 | [50] |

| Simple distillation | Bio-oil of carinata oil | <200 °C | 1 atm | Hydrocarbon biofuel | 91.97 | 8.03 | [17] |

| Fractional distillation | Corn stover bio-oil | ≤100 °C | 1 atm | Light fraction | 23.1 | 15.9 | [47] |

| Fractional distillation | Corn stover bio-oil | 100-180 °C | 1 atm | Middle fraction | 24.9 | 14.9 | [47] |

| Fractional distillation | Corn stover bio-oil | 180-250 °C | 1 atm | Heavy fraction | 7.1 | 6.8 | [47] |

| Fractional distillation | OLP of residual FOGa from grease traps | 175-235 °C | 1 atm | Kerosene fraction | 94.62 | 5.38 | [51] |

| Fractional distillation | OLP of residual FOGa from grease traps | 235-305 °C | 1 atm | Light diesel fraction | 73.86 | 26.14 | [14] |

| Fractional distillation | Bio-oil of deodar saw dust | <140 °C | 1 atm | IBPb<140 °C fraction | 46.04 | 2.59 | [99] |

| Fractional distillation | Bio-oil of pine saw dust | <140 °C | 1 atm | IBPb<140 °C fraction | 42.87 | 1.06 | [99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).