Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. CT and FDG PET CT Amage Acquisition

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

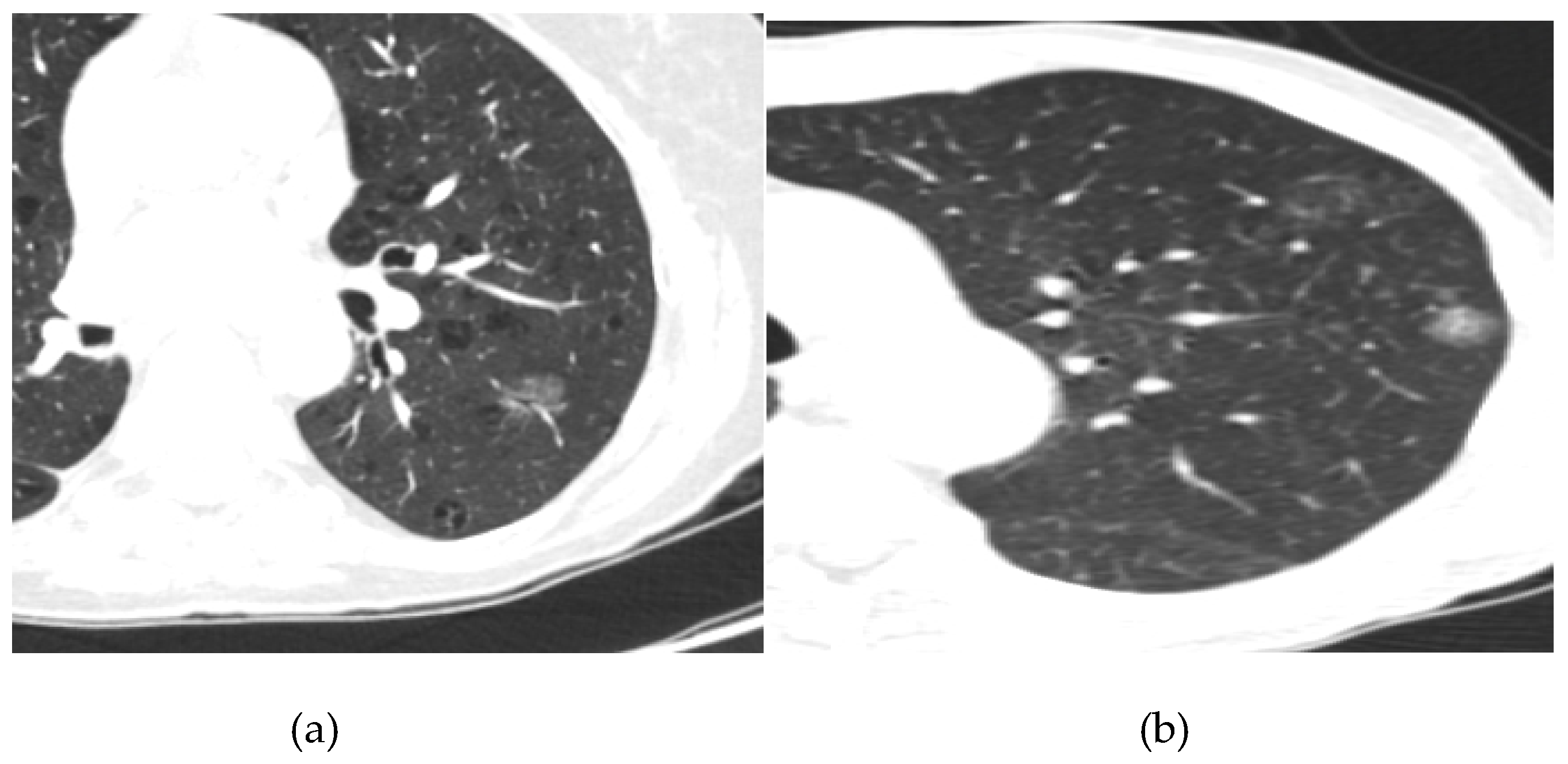

- Lepidic Pattern: The lepidic subtype, characterized by the growth of tumor cells along preexisting alveolar structures, often presents as a ground-glass opacity (GGO) on CT imaging. GGOs typically demonstrate a hazy or cloudy appearance and are associated with favorable prognosis. This type often exhibits low metabolic activity on PET imaging. This pattern typically manifests as a focal area of increased radiotracer uptake on CT, reflecting the underlying ground-glass opacity or consolidation.

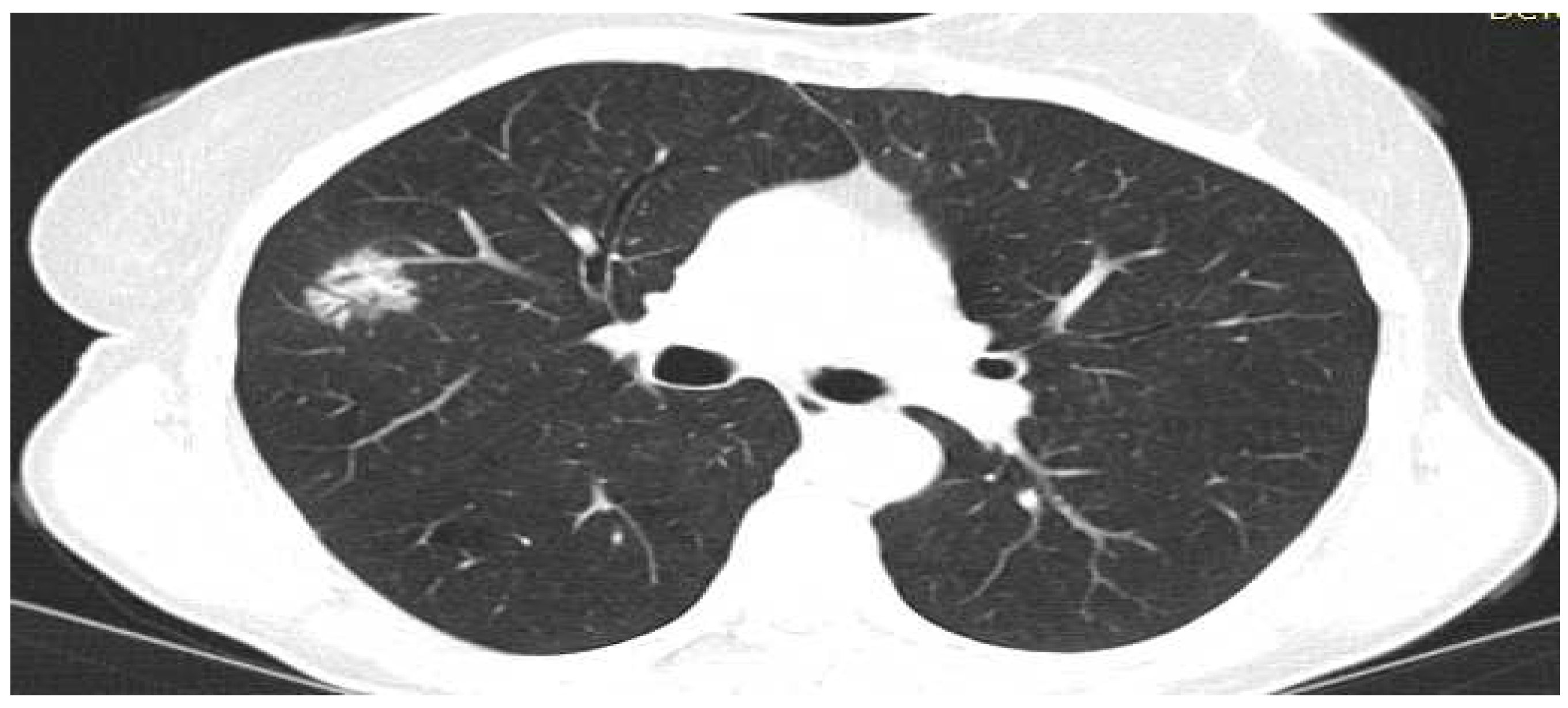

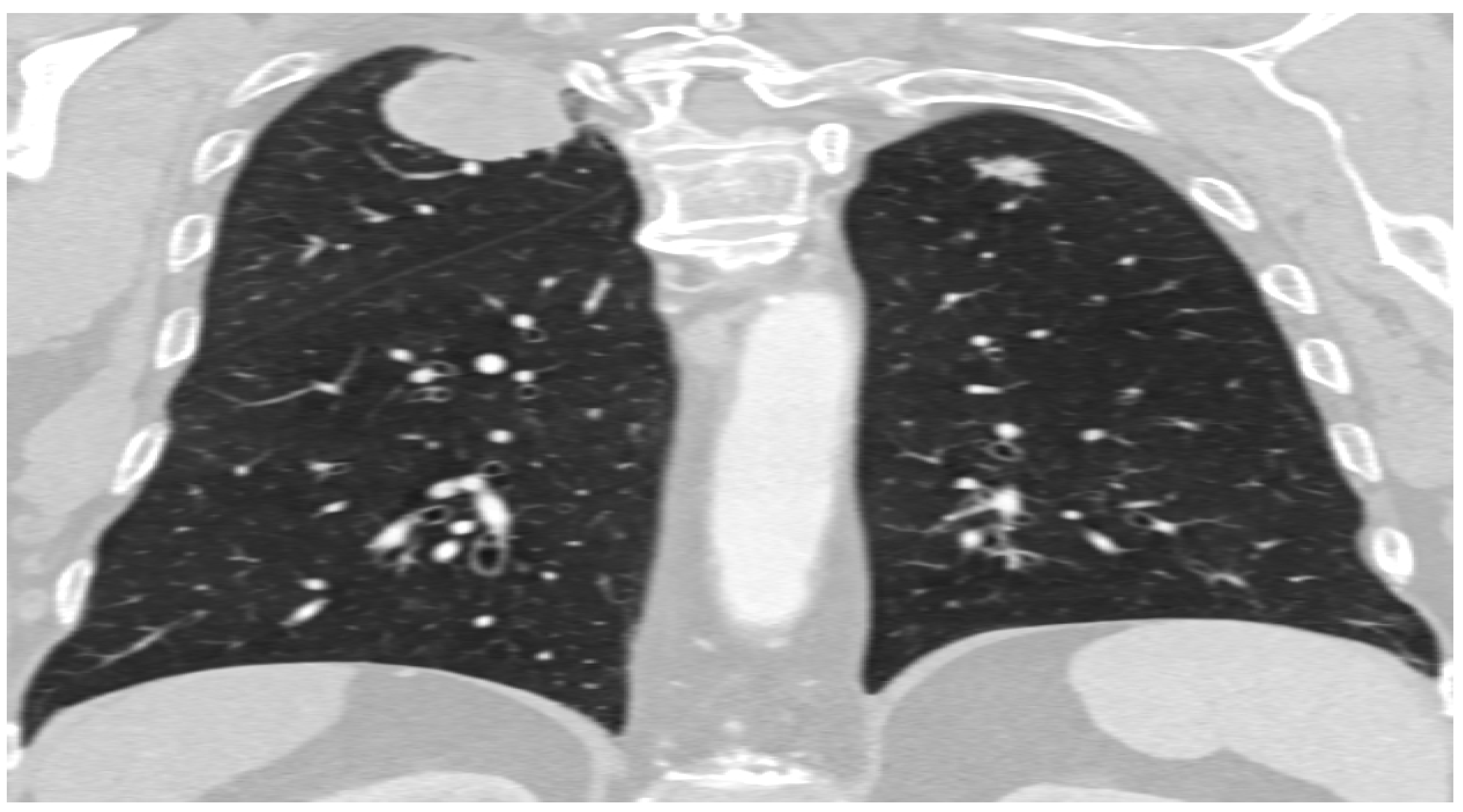

- Acinar Pattern: The acinar subtype, composed of glandular structures, often appears as a solid nodule or a partially solid nodule with a central ground-glass component on CT scans. The solid component is associated with a higher likelihood of lymph node involvement and poorer prognosis. The acinar subtype, composed of glandular structures, generally demonstrates moderate to high metabolic activity on PET-CT imaging. PET scans reveal focal areas of increased radiotracer uptake corresponding to solid components within the tumor

- Papillary Pattern: The papillary subtype, characterized by the presence of papillary projections, may manifest as a solid nodule with lobulated margins on CT imaging. The papillary subtype, characterized by papillary projections, typically shows increased radiotracer uptake on PET scans. The presence of avid radiotracer uptake corresponds to the solid components or invasive portions of the tumor, highlighting a higher risk of lymph node metastasis and potential aggressiveness.

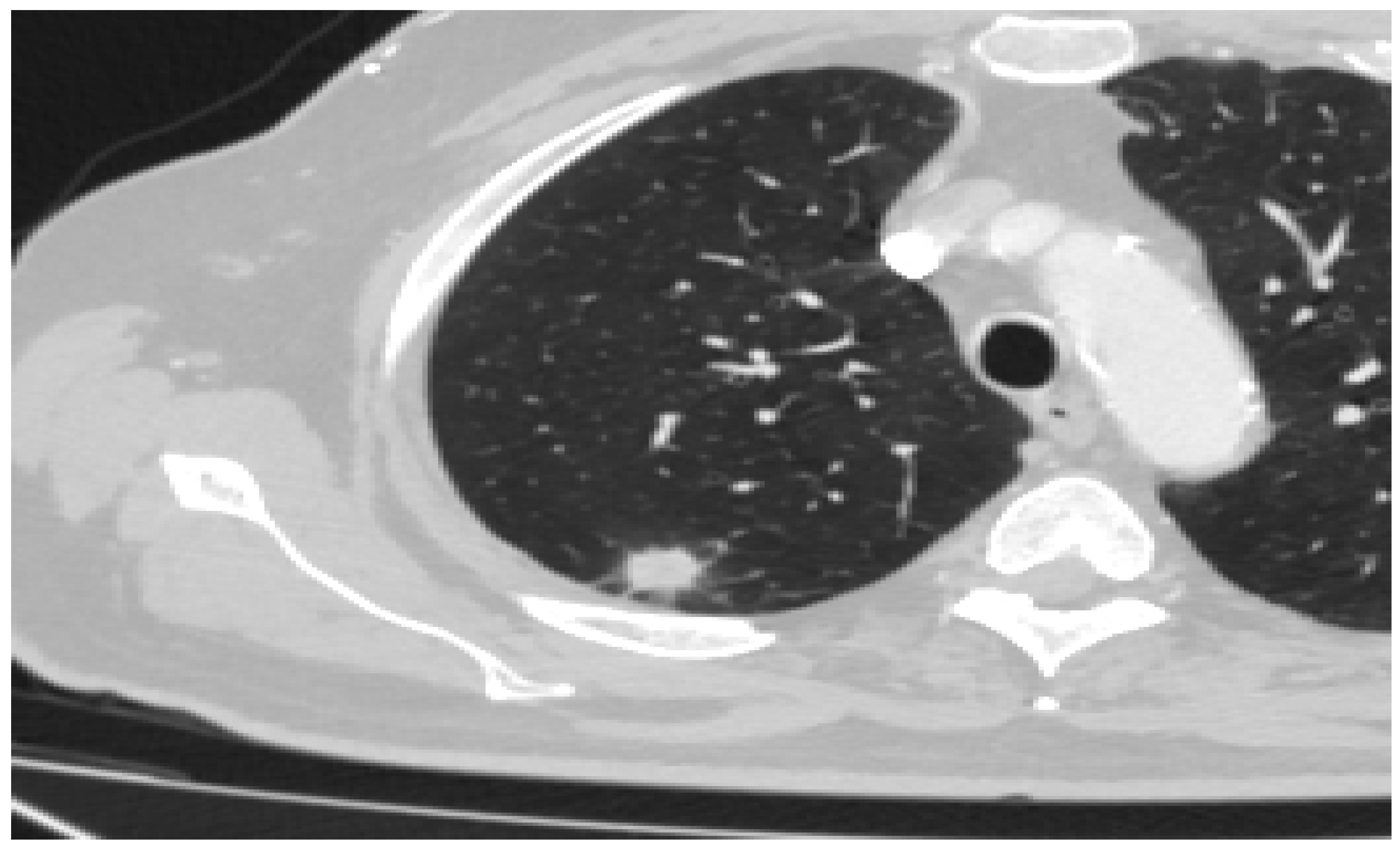

- Solid Pattern: The solid subtype, composed of sheets of tumor cells without distinctive glandular or papillary structures, typically appears as a homogeneous solid nodule on CT imaging. It is associated with a higher risk of lymph node metastasis, distant spread, and unfavorable prognosis. The solid subtype, composed of sheets of tumor cells without distinctive glandular or papillary structures, generally exhibits high metabolic activity on PET imaging.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, J.G.; Reymond, E.; Jankowski, A.; Brambilla, E.; Arbib, F.; Lantuejoul, S.; Ferretti, G.R. Adénocarcinomes pulmonaires: corrélations entre TDM et histopathologie. Journal de Radiologie Diagnostique et Interventionnelle. 2016, 97, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantuejoul, S.; Rouquette, I.; Brambilla, E.; Travis, W.D. Nouvelle classification OMS 2015 des adénocarcinomes pulmonaires et prénéoplasies. Annales de Pathologie. 2016, 36, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W. D.; Brambilla, E.; Noguchi, M.; Nicholson, A.G.; Geisinger, K.R.; Yatabe, Y.; Beer, D.G.; Powell, C.A.; Riely, G.J.; Van Schil, P.E.; et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2011, 6, 244–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagawa, M.; Johkoh, T.; Noguchi, M.; Morii, E.; Shintani, Y.; Okumura, M.; Hata, A.; Fujiwara, M.; Honda, O.; Tomiyama, N. Radiological prediction of tumor invasiveness of lung adenocarcinoma on thin-section CT. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017, 96, e6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.G.; Reymond, E.; Jankowski, A.; Brambilla, E.; Arbib, F.; Lantuejoul, S.; Ferretti, G.R. Lung adenocarcinomas: correlation of computed tomography and pathology findings. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016, 97, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, C.; Musick, A.; Glass, C. Adenocarcinoma overview. Available online: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungtumoradenocarcinoma.html (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Kao, T.N.; Hsieh, M.S.; Chen, L.W.; Yang, C.F.J.; Chuang, C.C.; Chiang, X.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Lee, Y.H.; Hsu, H.H.; Chen, C.M.; et al. CT-Based Radiomic Analysis for Preoperative Prediction of Tumor Invasiveness in Lung Adenocarcinoma Presenting as Pure Ground-Glass Nodule. Cancers 2022, 14, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.Y.; Coffey, D.M.; Medeiros, L.J.; Cagle, P.T. Prognostic significance of percentage of bronchioloalveolar pattern in adenocarcinomas of the lung. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology 2001, 5, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Chen, W.F.; He, W.J.; Yang, Z.M.; Li, M.; Xiao, L.; Hua, Y.Q. CT features differentiating pre- and minimally invasive from invasive adenocarcinoma appearing as mixed ground-glass nodules: mass is a potential imaging biomarker. Clin Radiol. 2018, 73, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazono, T.; Sakao, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Imai, S.; Kumazoe, H.; Kudo, S. Subtypes of peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung: differentiation by thin-section CT. Eur Radiol. 2005, 15, 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, E.; Morbini, P.; Cancellieri, A.; Damiani, S.; Cavazza, A.; Comin, C.E. Adenocarcinoma classification: patterns and prognosis. Pathologica. 2018, 110, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, I.; Nakanishi, R.; Kodate, M.; Osaki, T.; Hanagiri, T.; Takenoyama, M.; Yamashita, T.; Imoto, H.; Taga, S.; Yasumoto, K. Pleural retraction and intra-tumoral air-bronchogram as prognostic factors for stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma following complete resection. Int Surg. 2000, 85, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Woodruff, H.C.; Shen, J.; Refaee, T.; Sanduleanu, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Wang, R.; Xiong, J.; Bian, J.; et al. Diagnosis of Invasive Lung Adenocarcinoma Based on Chest CT Radiomic Features of Part-Solid Pulmonary Nodules: A Multicenter Study. Radiology. 2020, 297, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, H.M.; Knipe, H.C.; Pascoe, D.; Heinze, S.B. The many faces of lung adenocarcinoma: A pictorial essay. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2018, 62, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Deng, J.; Wu, J.; Hou, L.; Wu, C.; She, Y.; Sun, X.; Xie, D.; et al. Primary Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma of the Lung: Prognostic Value of CT Imaging Features Combined with Clinical Factors. Korean J Radiol. 2021, 22, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama, K.; Yanagawa, M. CT Diagnosis of Lung Adenocarcinoma: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation and Growth Rate. Radiology. 2020, 297, 199–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.; Niu, R.; Jiang, Z.; Shao, X.; Wang, Y. Role of PET/CT in Management of Early Lung Adenocarcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020, 214, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.Y.; Chen, T.X.; Chang, C.; Teng, H.H.; Xie, C.; Ruan, M.M.; Lei, B.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.H.; Yang, Y.H.; et al. SUVmax of 18FDG PET/CT Predicts Histological Grade of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Acad Radiol. 2021, 28, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogavero, A.; Bironzo, P.; Righi, L.; Merlini, A.; Benso, F.; Novello, S.; Passiglia, F. Deciphering Lung Adenocarcinoma Heterogeneity: An Overview of Pathological and Clinical Features of Rare Subtypes. Life 2023, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damirov, F.; Stoleriu, M.G.; Manapov, F.; Büsing, K.; Michels, J.D.; Preissler, G.; Hatz, R.A.; Hohenberger, P.; Roessner, E.D. Histology of the Primary Tumor Correlates with False Positivity of Integrated 18F-FDG-PET/CT Lymph Node Staging in Resectable Lung Cancer Patients. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.Y.; Chen, P.H.; Chen, K.C.; Hsu, H.H.; Chen, J.S. Computed Tomography-Guided Localization and Extended Segmentectomy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisi, D.; Rinaldi, M.; Necozione, S.; Curcio, C.; Rea, F.; Zaraca, F.; De Vico, A.; Zaccagna, G.; Di Leonardo, G.; Crisci, R.; et al. Is It Possible to Establish a Reliable Correlation between Maximum Standardized Uptake Value of 18-Fluorine Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography and Histological Types of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer? Analysis of the Italian VATS Group Database. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Nakada, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Sakakura, N.; Iwata, H.; Ohtsuka, T.; Kuroda, H. Prognostic Radiological Tools for Clinical Stage IA Pure Solid Lung Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3846–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudura, K.; Ritz, N.; Kutzker, T.; Hoffmann, M.H.K.; Templeton, A.J.; Foerster, R.; Kreissl, M.C.; Antwi, K. Predictive Value of Baseline FDG-PET/CT for the Durable Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in NSCLC Patients Using the Morphological and Metabolic Features of Primary Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.W.; Halpenny, D.F.; Ginsberg, M.S.; Papadimitrakopoulou, V.A.; de Groot, P.M. Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment: Current Status and the Role of Imaging. J Thorac Imaging. 2017, 32, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Shi, Y.; Niu, R.; Shao, X.; Shao, X. Association Analysis of Maximum Standardized Uptake Values Based on 18F-FDG PET/CT and EGFR Mutation Status in Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.K.; Lim, J.H.; Ryu, W.K.; Kim, L.; Ryu, J.-S. Solitary Uncommon Metastasis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Reports 2023, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, B.; Pierobon, M.; Wei, Q. Automated Classification of Lung Cancer Subtypes Using Deep Learning and CT-Scan Based Radiomic Analysis. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, L.; De Bernardi, E.; Bono, F.; Cortinovis, D.; Crivellaro, C.; Elisei, F.; L’Imperio, V.; Landoni, C.; Mathoux, G.; Musarra, M.; et al. The “digital biopsy” in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A pilot study to predict the PD-L1 status from radiomicsfeatures of [18F]FDG PET/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3401–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Su, D.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Chin, Y.; Chen, L.; Chan, C.; Zhang, R.; Gao, T.; Ben, X.; Jing, C. Predictive value of baseline metabolic tumor volume for non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 951557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, B.D.; Shroff, G.S.; Truong, M.T.; Ko, JP. Spectrum of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2019, 40, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succony, L.; Rassl, D.M.; Barker, A.P.; McCaughan, F.M.; Rintoul, R.C. Adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions of the lung: Detection, pathology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021, 99, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.G.; Park, S.; Park, C.M.; Jeon, Y.K.; Chung, D.H.; Goo, J.M.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, H. Histopathologic Basis for a Chest CT Deep Learning Survival Prediction Model in Patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma. Radiology. 2022, 305, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Acinar | Papillary | Lepidic | Solid | AIS-MIA | Overall p value | Comparison group* | Mean difference | 95%CI** | Post-hoc p value¥ | |

| n=32 | n=28 | n=19 | n=13 | n=10 | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD | 62.8±7.0 | 62.7±7.0 | 61.8±7.4 | 63.7±7.2 | 61.0±5.6 | 0.893 | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 21 (65.6) | 14 (50.0) | 4 (21.1) | 9 (69.2) | 5 (50.0) | 0.024 | Acinar vs. Lepidic | na | na | 0.003 |

| Female | 11 (34.4) | 14 (50.0) | 15 (78.9) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (50.0) | |||||

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.052 | |||||||||

| Non-smoker | 10 (31.3) | 16 (57.1) | 5 (26.3) | 7 (53.8) | 1 (10.0) | |||||

| Former smoker | 8 (25.0) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (10.0) | |||||

| Current smoker | 14 (43.8) | 10 (35.7) | 12 (63.2) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (80.0) |

| Acinar | Papillary | Lepidic | Solid | AIS-MIA | Overall p value | Comparison group* | Mean difference | 95%CI** | Post-hoc p value¥ | |

| n=32 | n=28 | n=19 | n=13 | n=10 | ||||||

| Tumor size, mean ± SD | 37.2±7.6 | 41.8±8.6 | 38.2±6.0 | 47.7±12.6 | 24.9±3.7 | <0.001 | Acinar vs. Solid | -10.44 | -18.77 to -3.14 | 0.002 |

| Acinar vs. AIS-MIA | 12.35 | 8.88 to 16.14 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Papillary vs. AIS-MIA | 16.89 | 12.92 to 20.76 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Lepidic vs. AIS-MIA | 13.26 | 9.79 to 16.74 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Solid vs. AIS-MIA | 22.79 | 15.68 to 30.54 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Component, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Solid | 32 (100) | 28 (100) | 19 (100) | 13 (100) | 9 (90.0) | 0.054 | ns | |||

| Necrosis | 3 (9.4) | 9 (32.1) | 5 (26.3) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.074 | ns | |||

| Ground glass | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (30.0) | 0.051 | ns | |||

| Edges n (%) | ||||||||||

| Round | 19 (59.4) | 14 (50.0) | 14 (73.7) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (50.0) | 0.244 | ns | |||

| Lobular | 4 (12.5) | 4 (14.3) | 2 (10.5) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (30.0) | |||||

| Spiculated | 9 (28.1) | 10 (35.7) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (20.0) |

| Acinar | Papillary | Lepidic | Solid | AIS-MIA | Overall p value | Comparison group* | Mean difference | 95%CI** | Post-hoc p value¥ | |

| n=32 | n=28 | n=19 | n=13 | n=10 | ||||||

| Pleural involvement, n (%) | 11 (34.4) | 15 (53.6) | 5 (26.3) | 8 (61.5) | 2 (20.0) | 0.084 | ns | |||

| Bronchial cut-off, n (%) | 12 (37.5) | 13 (46.4) | 10 (52.6) | 9 (69.2) | 5 (50.0) | 0.41 | ns | |||

| Vascular invasion, n (%) | 11 (34.4) | 16 (57.1) | 9 (47.4) | 6 (46.2) | 3 (30.0) | 0.397 | ns | |||

| No lymph node involvment | 9 (28.1) | 4 (14.3) | 9 (47.7) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (70.0) | 0.049 | ns | |||

| Ipsilateral lymph node involvment | 18 (56.3) | 18 (64.3) | 8 (42.1) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (30.3) | |||||

| Contralateral lymph node involvment | 5 (15.6) | 6 (21.4) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Acinar | Papillary | Lepidic | Solid | AIS-MIA | Overall p value | Comparison group* | Mean difference | 95%CI** | Post-hoc p value¥ | |

| n=32 | n=28 | n=19 | n=13 | n=10 | ||||||

| Metastases present, n (%) | 3 (9.4%) | 7 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (61.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001 | Acinar vs. solid | na | na | 0.001 |

| Lepidic vs. solid | na | na | <0.001 | |||||||

| Solid vs. AIS-MIA | na | na | 0.003 | |||||||

| SUVmax, mean ± SD | 4.9±1.1 | 5.3±1.3 | 5.1±0.7 | 6.3±0.8 | 3.3±0.8 | <0.001 | Acinar vs. solid | -1.35 | -1.89 to -0.76 | 0.001 |

| Acinar vs. AIS-MIA | 1.65 | 1.00 to 2.28 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Papillary vs. AIS-MIA | 2.01 | 1.35 to 2.72 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Lepidic vs. AIS-MIA | 1.83 | 1.23 to 2.38 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Solid vs. AIS-MIA | -3 | 2.32 vs. 3.59 | <0.001 |

| Acinar | Papillary | Lepidic | Solid | AIS-MIA | |

| n=32 | n=28 | n=19 | n=13 | n=10 | |

| Characteristic | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) |

| Tumor size | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | 1.04 (1.00-1.09) | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | 0.65 (0.51-0.83) |

| Solid component | na | na | na | na | na |

| Necrosis | 0.27 (0.07-1.03) | 2.57 (0.90-7.37) | 1.69 (0.46-6.17) | 1.80 (0.47-6.96) | na |

| Ground glass | 1.25 (0.27-5.89) | na | 0.69 (0.07-6.59) | 1.00 (0.11-9.38) | 7.19 (1.35-38.34) |

| Round edges | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] |

| Lobular edges | 0.62 (0.18-2.22) | 9.91 (0.25-3.22) | 0.32 (0.06-1.67) | 3.17 (0.83-12.19) | 2.28 (0.48-10.81) |

| Spiculated edges | 1.16 (0.42-3.16) | 2.16 (0.79-5.89) | 0.43 (0.11-1.74) | 0.28 (0.03-2.42) | 1.00 (0.18-5.62) |

| Pleural involvement | 0.62 (0.25-1.53) | 2.18 (0.89-5.34) | 0.52 (1.16-1.66) | 2.48 (0.73-8.43) | 0.35 (0.70-1.77) |

| Bronchial cut-off | 0.60 (0.25-1.48) | 0.87 (0.35-2.16) | 0.90 (0.31-2.62) | 3.53 (0.93-13.36) | 1.17 (0.30-4.56) |

| Vascular invasion | 0.55 (2.23-1.33) | 2.06 (0.85-4.99) | 1.17 (0.41-3.34) | 1.11 (0.34-3.60) | 0.52 (0.13-2.17) |

| No lymph node involvement | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] |

| Ipsilateral lymph node involvement | 1.08 (0.40-2.90) | 3.26 (0.98-10.80) | 0.43 (1.14-1.34) | 2.54 (0.50-12.98) | 0.20 (0.05-0.85) |

| Contralateral lymph node involvement | 1.32 (0.34-5.16) | 4.49 (1.02-19.73) | 0.30 (0.05-1.74) | 2.34 (0.29-19.04) | na |

| Metastases present | 0.34 (0.09-1.33) | 1.93 (0.65-5.72) | na | 14.09 (3.51-56.41) | na |

| SUVmax | 0.86 (0.59-1.23) | 1.21 (0.86-1.73) | 1.04 (0.69-1.57) | 2.64 (1.48-4.69) | 0.07 (0.02-0.29) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).